#Somatoform Disorder

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

I Don't Have ADHD, but I Am Suggestible.

I'm hideously suggestible, but it doesn't last. My brain unwrites that stuff right quick. Which I'm grateful for. #depression #anxiety #recovery

I’m not a hypochondriac. Much. I can exaggerate a pulled muscle with the best of them, but I draw the line at hitting up doctors with my exaggerated sense of injury. This makes me a good consumer of medical resources. That being said, I also don’t pursue medical help when I should. Also a problem. You’d think I’d have learned after one round of IV antibiotics, but no. A basic definition of…

View On WordPress

1 note

·

View note

Text

I have been absolutely full to bursting with emotion today, but I have no idea what emotion it is. All I know is that whenever I'm not distracting myself I'm just full of something and it's making it hard to get things done because my brain is telling me I need to do thing but I have no idea what that is.

#Emotions#Pez is a Mess#Pez is Weird#Personal#I wish I could just suppress the emotion and focus but#Somatoform Disorder#Blocking emotions leads to consequences

0 notes

Text

My mind literally controls my entire body why is it using it's power for evil

1 note

·

View note

Text

Interesting theory.

I've been wondering lately if somatoform disorder and related mental illnesses/behaviors like Munchausen's/factitious disorder and malingering are real (obviously it's at least a little over diagnosed, as imo some doctors will start making accusations the instant a diagnosis isn't easy).

this sentiment has always baffled me because my main doctor doesn't talk to me much about my chronic condition but i separately go to a specialist who spends a decent chunk of their time taking care of patients with said condition. and i find that they often have useful things to say. perks of having one of the more common conditions i suppose

239 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sintomi somatici: una componente sottovalutata dei disturbi mentali conseguenti a traumi infantili

I sintomi somatici comprendono una varietà di disturbi fisici, che causano compromissione funzionale e grave disagio emotivo; possono o meno essere associati ad altre condizioni mediche diagnosticate. Questi includono sintomi come disturbi gastrointestinali, dolori muscolari (ad esempio alle braccia, alla schiena e mal di testa), effetti cardiopolmonari (ad esempio dolore al petto e vertigini) e…

View On WordPress

#benessere mentale#colon irritabile#disturbo psicosomatico#disturbo somatoforme#esperienze infantili avverse#post-traumatic stress disorder#salute mentale#salute pubblica#sintomi somatici#stress psicologico#trauma infantile

0 notes

Text

#somatoform disorders#chronic fatigue syndrome#myalgic encephalomyelitis#anxiety#depression#Fatigue#substance abuse#sedentary lifestyle#post-traumatic stress disorder#poor diet#lack of sleep

0 notes

Text

I believe I found the article that talks about modular DID (Clinical Presentations of Multiple Personality Disorder by Richard P. Kluft), and it also has a bunch of other presentations such as:

Classic DID

"The overt and readily observable behavior of such patients fulfills diagnostic criteria for MPD on an ongoing basis for periods of months or years, or even for a lifetime."

frequent changes of executive control (switches) cause easily observable memory gaps and altered behavior

includes "amnesia for amnesia" (forgetting that you forgot)

Latent DID

"patients whose alters are generally inactive but are triggered to emerge infrequently by intercurrent stressors, many of which are analogous to, symbolic of, or trigger memories of childhood traumata."

examples include patients who become overt when their children reach the age(s) at which they were traumatized, or when their abusers become ill or die

Posttraumatic DID

covert until the patient experiences an overwhelming contemporary event

Extremely Complex or Polyfragmented DID

"occurs when there is a wide variety of alter personalities and their comings and goings are so frequent and/or ephemeral that it is hard to discern the outline of the MPD behind the rapidly fluctuating and switching manifestations."

subjective experiences of confused and fluctuating identity and memory is an indicator

Epochal or Sequential DID

"occurs when switches are rare—the newly emergent alter simply takes over for a long period, and the others go dormant."

often missed, and can be suspected in patients with dense amnesia for periods of their adult life

Isomorphic DID

"a group of very similar alters are largely in control, and/or the alters try to pass as one."

only overt manifestation may be an unevenness of memory and skills, a fluctuating level of function, and inconsistency that is striking in view of the patient's apparent strengths

can be seen as puzzling due to the apparent lack of alternating personalities

Coconscious DID

confusing for its apparent lack of amnesia (patients with this presentation would be diagnosed with DDNOS in the DSM-IV)

"Such cases present with apparent alters that know about one another and do not demonstrate time loss or memory gaps. Usually there is amnesia, but it is covered over or relates to events long past, and becomes apparent only in therapy."

Possessionform DID

"occurs when the alter that is most evident or the sole manifestation presents itself as a demon or devil."

Reincarnation/Mediumistic DID

"presentations in which the presenting alters are egosyntonic within certain unique belief systems but are found to overlie more typical alters."

Atypical/Private DID

many patients are quite high-functioning

"occurs when the alters are aware of one another, and the isomorphic presentation is consciously adapted to pass as one."

Secret DID

closely related to Atypical DID

"the alters, although classic, never emerge except when the host is alone, and unlike the private form, the host is unaware of the alters."

Ostensible Imaginary Companionship DID

"occurs when a patient is found to have an apparent adult version of imaginary companionship with an egosyntonic entity that is coconscious and copresent and engages in friendly and supportive dialog with an otherwise socially constricted host. Examination reveals, however, that this entity does assume executive control, and that (usually) other entities are present as well. "

Covert DID

the truly classic form of DID

may be subdivided roughly into Puppeteering (hapless or accepting), Phenocopy, Somatoform, and Orphan symptom varieties

Puppeteering or Passive-Influence Dominated DID

"occur when the host is dominated by alters that rarely emerge. If the host is unaware of what is transpiring, he or she feels him or herself the hapless victim of influences that force behavior in ways not willed or chosen."

Phenocopy DID

"most important of the covert forms. It occurs when the final common vector of the alters' influences create phenomena that are similar to the manifestations of other mental disorders, or when the urge of traumatic materials overwhelms the patient's ego strength."

should be considered when a patient who appears to have another mental disorder fails to improve with the application of a therapy appropriate for that condition or if the condition is associated with a prolonged therapy or a poor prognosis."

a useful approach to suspected phenocopy presentations would involve the DES and an interview

patients with high scores on both the DES and Hypnotic Induction Profile (HIP) are much more likely to have DID than any other condition.

Somatoform DID

very common

"occur[s] when the discomfort associated with a painful event is reexperienced, with no conscious connection between the symptom and the historical event."

Orphan Symptom DID

closely related to all covert categories

"Dissociating patients are prone to divide their painful experiences along the behavior, affect, sensation, and knowledge (BASK) dimensions described by Braun. The intrusion of any such element into the ongoing mental life of a patient should initiate the search for a DD—an unwilling motor act, the unexplained intrusion of a strong affect, a sensation for which no medical cause can be found, or intrusive traumatic imagery."

Switch-Dominated DID

"In this form the switch process is occurring so frequently and/or rapidly that it rather than amnesia or the clear emergence of alters dominates. The patient appears bewildered, confused, and forgetful."

most common in extremely complex DID with a large number of alters

patient may be thought to have an affective disorder, psychosis, or a seizure disorder

Ad Hoc DID

very rare

"a single helper alter that rarely emerges persists and creates a series of short-lived alters that function briefly and cease to exist. The helper may speak to the host inwardly to advise on how to frustrate inquiries."

Modular DID

quite uncommon but most intrusive

"occurring when usually autonomous ego functions become personified and split and when personalities are reconfigured from their elements when mobilized. More standard alters may or may not be present. Such patients have an "MPD feel" about them, but once one has talked to qn apparent alter one may appreciate its vagueness and may never encounter it in exactly the same way again."

"The few patients in whom this form has been found have been seriously abused, brilliant, and creative... There are clear analogies between this form of dissociative defense and computer functioning, and it may well be that this form will be seen with increasing frequency in the future. In all cases thus far seen, the common factors have been stellar brilliance, bizarre symptoms, and an inconsistency in the manifestations of the apparent alters, who appear generally similar on repeated encounters, but never quite the same."

Quasi-Roleplaying DID

very rare prior to 1985

"A personality plays out what has been learned of the other alters as deliberately enacted roles, and then informs the interviewer that he or she is feigning MPD. In another form, the patient immediately follows up apparent alter behavior with statements that the patient is aware of what has occurred and has willfully generated it. With further assessment, it is discovered that the patient is upset about the possibility that the diagnosis is MPD, and is attempting to preempt the chance of receiving the diagnosis."

Pseudo-False Positive DID

quite common in the 1970s and early 1980s, but became more rare as DID became more widely recognized

"The patient makes a questionable presentation that is clearly based on a well-known case or is so flamboyant as to appear contrived. The presentation is dropped as soon as the patient appreciates that the clinician is competent, caring, and interested in him or her as a distinct human being rather than as a curiosity."

#dissociative identity disorder#other specified dissociative disorder#kluft#richard p kluft#long post

331 notes

·

View notes

Text

pretty boy confessional

So I know this is going to sound... improbable... but it's been going on for years now - since 2018, in fact. In the worst of my psychosis I believed I was going to transform. Here. On earth. (What a beautiful disaster!) And this... manifested in the form of pain. Bone pain. Particularly in my chin, my jaw, and on the bridge of my nose. I'd liken the pain to a toothache - it's that same sort of stinging pain. I'm properly medicated now, but the pain has not abated. I have this pain almost every day of my life. It comes and goes. Some days it's worse. Some days I think it's over. And - I don't know if it's a hallucination or a somatoform disorder or a conversion disorder or what. I'm not a doctor. And the therapist I talked to about this didn't have an answer, either. It's just... strange. Strange and neverending.

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

in discussions about DID and OSDD, symptoms besides alter formation and function can be neglected as a conversation topic. let's start those conversations!

respond below with your own experiences with the following:

1. Amnesia (time loss, fugues, skill loss, childhood amnesia, emotional amnesia, personal identity amnesia)

2. Somatoform Symptoms (weakness or paralysis, non-epileptic seizures, reduced senses, pain, muscle tension, dizziness, fainting, chronic fatigue)

3. Depersonalization/Derealization (feeling like you're seeing yourself from outside the body or feeling like the things around you aren't real)

4. Self-alteration/Identity confusion (not related to alters! just having little or a confused sense of self)

5. Flashbacks (episodic flashbacks, sensory flashbacks, emotional flashbacks)

6. Other psychotic-like dissociative symptoms (confused thinking, delusions, hallucinations)

if you can think of any other symptoms, let me know!!

note: some of these symptoms overlap with the symptoms of other disorders. you can speak about your experiences with those disorders too! i find it often unproductive to sort whatever personal experiences i have with mental illness into one disorder or another. they don't usually fit into neat little boxes like that.

if you experience any of the following symptoms, feel free to talk about them, regardless if you fit into one diagnostic criteria or another. this post is about starting conversations about personal experiences related to the problems with mental illness we have in our life!

i'll start, for example. when i was incredibly triggered the other day, i found myself in a sort of brain-foggy fugue. i couldn't speak, i couldn't react when people were talking to me, all i could do was walk automatically to the bed and sit there. when my partner came in to talk to me, i was unresponsive. i knew she was there, but i couldn't react. that was a pretty scary time, but knowing that this was a documented phenomenon that wasn't just in my head helped curb my anxiety about it. after a while, it passed, and i was able to speak again!

have you ever had any experiences with these symptoms? what were they like? what helped with treating them? do you have any tips or tricks for dealing with them?

#osddid#actually did#did system#did osdd#actually traumagenic#plurality#system#actually plural#pluralgang#candyrain speaks#lee.txt

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

Somatization, Somatic Symptoms, and Somatic Disorders. And Variayr.

Somatization is a fairly simple concept. It refers to any type of physical manifestation of symptoms originating from a mental health condition. Notably, somatization is not neurological, and the conflation of these two things comes from somatization originally being considered part of conversion disorder (which was later split into somatoform and functional neurological disorders). The difference between these two presentations is very important. FND is diagnosed by a neurologist, SSD is diagnosed by a psychiatrist, as it is a mental disorder.

Secondary somatization, or what I’ll just call somatic symptoms, are physical symptoms caused by non-somatic disorders. Examples of somatic symptoms include GI involvement in severe anxiety disorders or soreness and numbness in depression. Most often, somatic symptoms related to non-somatic disorders tend to have similar presentations across different patients. Feeling stomach or chest pain are incredibly common manifestations in people with anxiety, and even occur in people without anxiety disorders when they experience anxiety. This symptom is very well-established in its link to anxiety as a condition, so there isn’t much discourse for it to be considered anything more than a somatic symptom of anxiety. In a disorder where somatization has been less studied, like dysphoria, it can be harder to identify a more “universal” set of somatic symptoms that someone might develop, but physical symptoms related to dysphoria, such as psychogenic pain of the sex characteristics, would be in this category of somatization.

Somatic disorders, however, are primary somatization. This is somatization as the first a foremost symptom (although I’m going to touch on some cases where it isn’t exactly). Somatic disorders are a type of structural dissociative disorder, which means that, unlike other conditions with somatic symptoms, somatic disorders are inherently trauma-related. Dr. Onno van der Hart, known for his work on CDDs, also outlined that simple somatoform disorders (the preceding diagnosis of SSD) are a type of primary structural dissociation, one ANP and one EP, although more complex cases could exist. He posited that the existence of somatic symptoms could be a greater indicator of PTSD and complex dissociative disorders than many of our current tests at the time, and he highly favored the somatoform dissociation questionnaire (created by Dr. Nijenhuis, who also writes quite a bit on this topic). Manifestations of somatic symptoms in people with SDDs or a dissociative disorder that subsumes SDD (which is to say, much like how someone with DID is not also diagnosed with DPDR, an SDD diagnosis is generally considered unnecessary), these symptoms are highly individual. Patients with these disorders experience an extremely wide array of physical symptoms that are, most often, manifestations of physical trauma their body has endured (such as an SA survivor feeling pain in their genitalia), or are metaphorically representative of it (a DID alter that doesn’t see because it intends to protect itself by not witnessing the trauma). These types of disorders are, although ranging in complexity, nearly always going to be more complex than the cookie cutter standard somatic symptoms of well-established conditions. Treating somatic disorders generally requires trauma integrative therapies or EMDR, whereas somatic symptoms in other conditions can be more easily treated with generalized programs like eight week CBT.

All of this to get to the thing that inspired this post, the “variayr” thing going around. Even if you truly had a somatic disorder which resulted in hormonal changes (which, yes, actually has been studied, although only one study on a patient with DID, so not exactly universally compelling evidence), it would not result in a “neurological sex difference,” because that is not what the term neurological means, and it isn’t how the somatization of simpler disorders like dysphoria works. And if it did? Why on earth would a spontaneous hormonal change not just be fucking intersex

14 notes

·

View notes

Note

for the did ama, what's something you wish more people understood about did? (this can refer to singlets, people newly diagnosed, stuff that the community in general just may not know or acknowledge, etc)

i kind of share something similar to this in this ask to do with child alters if you wanted to see that

anyways there's probably a lot of angles i could go at this with but hm. i kind of hate how the online community is SO focused on alters themselves, identity alteration, like i think to a lot of people to be perceived as a Valid DID Haver you have to have alters with different names and different pronouns who act totally different from one another and that's just... not... not necessary or even common.

i took a bit to answer this because i wanted to pull up this study which has this quote, referencing some kluft research:

Many clinicians and lay people believe that DID presents with dramatic, florid personality states with obvious state transitions (switching). These florid presentations are likely based on media stereotypes, but actually occur in only about 5% of DID patients [60]. The vast majority of DID patients have subtle presentations characterized by a mixture of dissociative and PTSD symptoms embedded with other symptoms such as posttraumatic depression, substance abuse, somatoform symptoms, eating disorders, personality disorders, and self-destructive and impulsive behaviors [23, 61].

DID is a heavily covert disorder for many and while it's not unusual or even surprising that going into therapy and purposefully interacting with alters + using social media where that sort of behavior is expected/encouraged can cause us to become more "florid", many of us aren't like that... at all! and the lack of representation for people with DID who don't have super distinct alters or who simply don't want to share that information online is actually kind of appalling to me. DID is a dissociative disorder caused by childhood trauma first and foremost and comes with all the struggles related to those things. alters are just one piece of the puzzle. and the continued focus on alters harms both singlets because they don't understand DID outside of that, and people with DID... i can't tell you how many times i've talked to people with very obvious DID who thought they didn't have it because they didn't match social media depictions of the disorder. it's like everyone's trying to be like Sybil, subconsciously or not, and that's just... not always how it is!!

of course people with DID who have florid presentations are valid too and there are aspects of my DID that are very Not covert but growing up my situation was a lot more subtle and even now, there's so much about my DID people don't see because the only acceptable way to parse or talk about your symptoms and experience online are by well defined alters and the majority of our alters are just Not like that. i have so many alters that are just "me but slightly to the left" who would be hard to detect personality changes with, etc. many such cases.

tldr very good to keep in mind that people with DID are traumatized and dissociative individuals with a variety of symptoms that may or may not fall into the "idealized" standard depiction of DID on social media and in fiction, and i REALLY wish there was more discussion on the other parts of this disorder more often

#kiki was here#asks#the DID ama#mephilesthegay#i think it's easy tofall into the trap of only talking about alters#cause talking about alters can be fun!#it's like an escape from the bad of it all sometimes#and some talking about alters is good#just wish there was more balance yknow

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Once again, doing the research, so you don't have to, A THREAD.

1). Separating Fact from Fiction: An Empirical Examination of Six Myths About Dissociative Identity Disorder (the full article)

Bethany L. Brand, PhD, Vedat Sar, MD, Pam Stavropoulos, PhD, Christa Krüger, MB BCh, MMed (Psych), MD, Marilyn Korzekwa, MD, Alfonso Martínez-Taboas, PhD, and Warwick Middleton, MB BS, FRANZCP, MD

Dissociative identity disorder (DID) is defined in the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) as an identity disruption indicated by the presence of two or more distinct personality states (experienced as possession in some cultures), with discontinuity in sense of self and agency, and with variations in affect, behavior, consciousness, memory, perception, cognition, or sensory-motor functioning.1 Individuals with DID experience recurrent gaps in autobiographical memory. The signs and symptoms of DID may be observed by others or reported by the individual. DSM-5 stipulates that symptoms cause significant distress and are not attributable to accepted cultural or religious practices. Conditions similar to DID but with less-than-marked symptoms (e.g., subthreshold DID) are classified among “other specified dissociative disorders.”

DID is a complex, posttraumatic developmental disorder.2,3 DSM-5 specifically locates the dissociative disorders chapter after the chapter on trauma- and stressor-related disorders, thereby acknowledging the relationship of the dissociative disorders to psychological trauma. The core features of DID are usually accompanied by a mixture of psychiatric symptoms that, rather than dissociative symptoms, are typically the patient’s presenting complaint.3,4 As is common among individuals with complex, posttraumatic developmental disorders, DID patients may suffer from symptoms associated with mood, anxiety, personality, eating, functional somatic, and substance use disorders, as well as psychosis, among others.3–8 DID can be overlooked due to both this polysymptomatic profile and patients’ tendency to be ashamed and avoidant about revealing their dissociative symptoms and history of childhood trauma (the latter of which is strongly implicated in the etiology of DID).9–14

Social, scientific, and political influences have since converged to facilitate increased awareness of dissociation. These diverse influences include the resurgence of recognition of the impact of traumatic experiences, feminist documentation of the effects of incest and of violence toward women and children, continued scientific interest in the effects of combat, and the increasing adoption of psychotherapy into medicine and psychiatry.18,29 The increased awareness of trauma and dissociation led to the inclusion in DSM-III of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), dissociative disorders (with DID referred to as multiple personality disorder), and somatoform disorders, and to the discarding of hysteria.30 Concurrently, traumatized and dissociative patients with severe symptoms (e.g., suicidality, impulsivity, self-mutilation) gained greater attention as psychiatry began to treat more severe psychiatric conditions with psychotherapy, and as some acutely destabilized DID patients required psychiatric hospitalization.31 These developments facilitated a climate in which researchers and clinicians could consider how a traumatized child or adult might psychologically defend himself or herself against abuse, betrayal, and violence. Additionally, the concepts of identity, alongside identity crisis, identity confusion, and identity disorder, were introduced to psychiatry and psychology, thereby emphasizing the links between childhood, society, and epigenetic development.32,33

In this climate of renewed receptivity to the study of trauma and its impact, research in dissociation and DID has expanded rapidly in the 40 years spanning 1975 to 2015.14,34 Researchers have found dissociation and dissociative disorders around the world.3,12,35–45 For example, in a sample of 25,018 individuals from 16 countries, 14.4% of the individuals with PTSD showed high levels of dissociative symptoms.35 This research led to the inclusion of a dissociative subtype of PTSD in DSM-5.1 Recent reviews indicate an expanding and important evidence base for this subtype.14,36,46

Notwithstanding the upsurge in authoritative research on DID, several notions have been repeatedly circulated about this disorder that are inconsistent with the accumulated findings on it. We argue here that these notions are misconceptions or myths. We have chosen to limit our focus to examining myths about DID, rather than dissociative disorders or dissociation in general. Careful reviews about broader issues related to dissociation and DID have recently been published.47–49 The purpose of this article is to examine some misconceptions about DID in the context of the considerable empirical literature that has developed about this disorder. We will examine the following notions, which we will show are myths:

belief that DID is a “fad”

belief that DID is primarily diagnosed in North America by DID experts who overdiagnose the disorder

belief that DID is rare

belief that DID is an iatrogenic disorder rather than a trauma-based disorder

belief that DID is the same entity as borderline personality disorder

belief that DID treatment is harmful to patients

MYTH 1: DID IS A FAD

Some authors opine that DID is a “fad that has died.”50–52 A “fad” is widely understood to describe “something (such as an interest or fashion) that is very popular for a short time.”53 As we noted above, DID cases have been described in the literature for hundreds of years. Since the 1980 publication of DSM-III,30 DID has been described, accepted, and included in four different editions of the DSM. Formal recognition as a disorder for over three decades contradicts the notion of DID as a fad.

To determine whether research about DID has declined (which would possibly support the suggestion that the diagnosis is a dying fad), we searched PsycInfo and MEDLINE using the terms “multiple personality disorder” or “dissociative identity disorder” in the title for the period 2000–14. Our search yielded 1339 hits for the 15-year period. This high number of publications speaks to the level of professional interest that DID continues to attract.

Recent reviews attest that a solid and growing evidence base for DID exists across a range of research areas:

DID patients can be reliably and validly diagnosed with structured and semistructured interviews, including the Structured Clinical Interview for Dissociative Disorders–Revised (SCID-D-R)54 and Dissociative Disorders Interview Schedule (DDIS)55,56 (reviewed in Dorahy et al. [2014]).14 DID can also be diagnosed in clinical settings, where structured interviews may not be available or practical to use.57

DID patients are consistently identified in outpatient, inpatient, and community samples around the world.12,37–45

DID patients can be differentiated from other psychiatric patients, healthy controls, and DID simulators in neurophysiological and psychological research.58–63

DID patients usually benefit from psychotherapy that addresses trauma and dissociation in accordance with expert consensus guidelines.64–66

An expanding body of research examines the neurobiology, phenomenology, prevalence, assessment, personality structure, cognitive patterns, and treatment of DID. This research provides evidence of DID’s content, criterion, and construct validity.14,55 The claim that DID is a “fad that has died” is not supported by an examination of the body of research about this disorder.

MYTH 2: DID IS PRIMARILY DIAGNOSED IN NORTH AMERICA BY DID EXPERTS WHO OVERDIAGNOSE THE DISORDER

Some authors contend that DID is primarily a North American phenomenon, that it is diagnosed almost entirely by DID experts, and that it is overdiagnosed.50,67–69 Paris50(p 1076) opines that “most clinical and research reports about this clinical picture [i.e., DID] have come from a small number of centers, mostly in the United States that specialize in dissociative disorders.” As we show below, the empirical literature indicates not only that DID is diagnosed around the world and by clinicians with varying degrees of experience with the disorder, but that DID is actually underdiagnosed rather than overdiagnosed.

Belief That DID Is Primarily Diagnosed in North America

According to some authors, DID is primarily diagnosed in North America.50,52,70 We investigated this notion in three ways: by examining the countries in which prevalence studies of DID have been conducted; by inspecting the countries from which DID participants were recruited in an international treatment-outcome study of DID; and by conducting a systematic search of published research to determine the countries where DID has been most studied.

Table 1

Dissociative Disorder Prevalence Studies

First, our results show that DID is found in prevalence studies around the world whenever researchers conduct systematic assessments using validated interviews. Table Table11 lists the 14 studies that have utilized structured or semistructured diagnostic interviews for dissociative disorders to assess the prevalence of DID.80 These studies have been conducted in seven countries: Canada, Germany, Israel, the Netherlands, Switzerland, Turkey, and the United States.37–39,44,45,71–79

Second, in addition to the prevalence studies, a recent prospective study assessed the treatment outcome of 232 DID patients from around the world. The participants lived in Argentina, Australia, Belgium, Brazil, Canada, Germany, Israel, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Singapore, Slovakia, South Africa, Sweden, Taiwan, and the United States.81 That is, the participants came from every continent except Antarctica.

Third, we conducted a systematic search of published, peer-reviewed DID studies. Using the search terms “dissociative identity disorder” and “multiple personality disorder,” we conducted a literature review for the period 2005–13 via MEDLINE, PsycInfo, and the Journal of Trauma and Dissociation. This search yielded 340 articles. We selected empirical research studies in which DID or multiple personality disorder had been diagnosed in patients. We recorded authors’ countries and institutions, and whether structured interviews were used to diagnose DID. Over this nine-year period, 70 studies included DID patients. Significantly, these studies were conducted by authors from 48 institutions in 16 countries. In 28 (40%) of studies, structured interviews (SCID-D or DDIS) were administered to diagnose DID.

In summary, all three methods contradicted the claim that DID is diagnosed primarily in North America.

Belief That DID Is Primarily Diagnosed by DID experts

Lynn and colleagues69(p 50) argue that “most DID diagnoses derive from a small number of therapy specialists in DID.” Other critics voice similar concerns.50,82,83 Research does not substantiate this claim. For example, 292 therapists participated in the prospective treatment-outcome study of DID conducted by Brand and colleagues.81 The majority of therapists were not DID experts. Similarly, a national random sample of experienced U.S. clinicians found that 11% of patients treated in the community for borderline personality disorder (BPD) also met criteria for comorbid DID.84 None of the therapists were DID experts. In an Australian study of 250 clinicians from several mental health disciplines, 52% had diagnosed a patient with DID.85 These studies show that DID is diagnosed by clinicians around the world with varying degrees of expertise in DID.

Belief That DID Is Overdiagnosed

A related myth is that DID is overdiagnosed. Studies show, however, that most individuals who meet criteria for DID have been treated in the mental health system for 6–12 years before they are correctly diagnosed with DID.4,86–89 Studies conducted in Australia, China, and Turkey have found that DID patients are commonly misdiagnosed.78,89,90 For example, in a study of consecutive admissions to an outpatient university clinic in Turkey, 2.0% of 150 patients were diagnosed with DID using structured interviews confirmed by clinical interview.74 Although 12.0% were assessed to have one of the dissociative disorders, only 5% of the dissociative patients had been diagnosed previously with any dissociative disorder. Likewise, although 29% of the patients from an urban U.S. hospital-based, outpatient psychiatric clinic were diagnosed via structured interviews with dissociative disorders, only 5% had a diagnoses of dissociative disorders in their medical records.37 Similar results have been found in consecutive admissions to a Swiss university outpatient clinic91 and consecutive admissions to a state psychiatric hospital in the United States45 when patients were systematically assessed with structured diagnostic interviews for dissociative disorders. This pattern is also found in nonclinical samples. Although 18.3% of women in a representative community sample in Turkey met criteria for having a dissociative disorder at some point in their lives, only one-third of the dissociative disorders group had received any type of psychiatric treatment.78 The authors concluded, “The majority of dissociative disorders cases in the community remain unrecognized and unserved.”78(p 175)

Studies that examine dissociative disorders in general, rather than focusing on DID, find that this group of patients are often not treated despite high symptomatology and poor functioning. A random sample of adolescents and young adults in the Netherlands showed that youth with dissociative disorders had the highest level of functional impairment of any disorder studied but the lowest rates (2.3%) of referral for mental health treatment.92 Those with dissociative disorders in a nationally representative sample of German adolescents and young adults were highly impaired, yet only 16% had sought psychiatric treatment.93 These findings point to the conclusion that dissociative disorder patients are underrecognized and undertreated, rather than being overdiagnosed.

Why is DID so often underdiagnosed and undertreated? Lack of training, coupled with skepticism, about dissociative disorders seems to contribute to the underrecognition and delayed diagnosis. Only 5% of Puerto Rican psychologists surveyed reported being knowledgeable about DID, and the majority (73%) had received little or no training about DID.94 Clinicians’ skepticism, about DID increased as their knowledge about it decreased. Among U.S. clinicians who reviewed a vignette of an individual presenting with the symptoms of DID, only 60.4% of the clinicians accurately diagnosed DID.95 Clinicians misdiagnosed the patient as most frequently suffering from PTSD (14.3%), followed by schizophrenia (9.9%) and major depression (6.6%). Significantly, the age, professional degree, and years of experience of the clinician were not associated with accurate diagnosis. Accurate diagnoses were most often made by clinicians who had previously treated a DID patient and who were not skeptical about the disorder. It is concerning that clinicians were equally confident in their diagnoses, regardless of their accuracy. A study in Northern Ireland found a similar link between a lack of training about DID and misdiagnosis by clinicians.96 Psychologists more accurately detected DID than did psychiatrists (41% vs. 7%, respectively). Australian researchers found that misdiagnosis was often associated with lack of training about DID and with skepticism regarding the diagnosis.85 They concluded, “Clinician skepticism may be a major factor in under-diagnosis as diagnosis requires [dissociative disorders] first being considered in the differential. Displays of skepticism by clinicians, by discouraging openness in patients, already embarrassed by their symptoms, may also contribute to the problem.”85(p 944)

In short, far from being overdiagnosed, studies consistently document that DID is underrecognized. When systematic research is conducted, DID is found around the world by both experts and nonexperts. Ignorance and skepticism about the disorder seem to contribute to DID being an underrecognized disorder.

MYTH 3: DID IS RARE

Many authors, including those of psychology textbooks, argue that DID is rare.70,97–99 The prevalence rates found in psychiatric inpatients, psychiatric outpatients, the general population, and a specialized inpatient unit for substance dependence suggest otherwise (see Table Table1).1). DID is found in approximately 1.1%–1.5% of representative community samples. Specifically, in a representative sample of 658 individuals from New York State, 1.5% met criteria for DID when assessed with SCID-D questions.77 Similarly, a large study of community women in Turkey (n = 628) found 1.1% of the women had DID.78

Studies using rigorous methodology, including consecutive clinical admissions and structured clinical interviews, find DID in 0.4%–6.0% of clinical samples (see Table Table1).1). Studies assessing groups with particularly high exposure to trauma or cultural oppression show the highest rates. For example, 6% of consecutive admissions in a highly traumatized, U.S. inner city sample were diagnosed with DID using the DDIS.37 By contrast, only 2.0% of consecutive psychiatric inpatients received a diagnosis of DID via the SCID-D in the Netherlands.38 The difference in prevalence may partially stem from the very high rates of trauma exposure and oppression in the U.S. inner-city, primarily minority sample.

Possession states are a cultural variation of DID that has been found in Asian countries, including China, India, Iran, Singapore, and Turkey, and also elsewhere, including Puerto Rico and Uganda.46,100–102 For example, in a general population sample of Turkish women, 2.1% of the participants reported an experience of possession.102 Two of the 13 women who reported an experience of possession had DID when assessed with the DDIS. Western fundamentalist groups have also characterized DID individuals as possessed.102 Such findings are inconsistent with the claim that DID is rare.

Go to:

MYTH 4: DID IS AN IATROGENIC DISORDER RATHER THAN A TRAUMA-BASED DISORDER

One of the most frequently repeated myths is that DID is iatrogenically created. Proponents of this view argue that various influences—including suggestibility, a tendency to fantasize, therapists who use leading questions and procedures, and media portrayals of DID—lead some vulnerable individuals to believe they have the disorder.52,69,83,103–107 Trauma researchers have repeatedly challenged this myth.48,49,108–111 Space limitations require that we provide only a brief overview of this claim.

A recent and thorough challenge to this myth comes from Dalenberg and colleagues.48,49 They conducted a review of almost 1500 studies to determine whether there was more empirical support for the trauma model of dissociation—that is, that antecedent trauma causes dissociation, including dissociative disorders—or for the fantasy model of dissociation. According to the latter (also known as the iatrogenic or sociocognitive model), highly suggestible individuals enact DID following exposure to social influences that cause them to believe that they have the disorder. Thus, according to the fantasy model proponents, DID is not a valid disorder; rather, it is iatrogenically induced in fantasy-prone individuals by therapists and other sources of influence.

Dalenberg and colleagues 48,49 concluded from their review and a series of meta-analyses that little evidence supports the fantasy model of dissociation. Specifically, the effect sizes of the trauma-dissociation relationship were strong among individuals with dissociative disorders, and especially DID (i.e., .54 between child sexual abuse and dissociation, and .52 between physical abuse and dissociation). The correlations between trauma and dissociation were as strong in studies that used objectively verified abuse as in those relying on self-reported abuse. These findings strongly contradict the fantasy model hypothesis that DID individuals fantasize their abuse. Dissociation predicted only 1%–3% of the variance in suggestibility, thereby disproving the fantasy model’s notion that dissociative individuals are highly suggestible.

Despite the concerns of fantasy model theorists that DID is iatrogenically created, no study in any clinical population supports the fantasy model of dissociation. A single study conducted in a “normal” sample of college students showed that students could simulate DID.112 That study, by Spanos and colleagues, documents that students can engage in identity enactments when asked to behave as if they had DID. Nevertheless, the students did not actually begin to believe that they had DID, and they did not develop the wide range of severe, chronic, and disabling symptoms displayed by DID patients.3

The study by Spanos and colleagues112 was limited by the lack of a DID control group. Several recent controlled studies have found that DID simulators can be reliably distinguished from DID patients on a variety of well-validated and frequently used psychological personality tests (e.g., Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory–2),113,114 forensic measures (e.g., Structured Interview of Reported Symptoms),61,115,116 and neurophysiological measures, including brain imaging, blood pressure, and heart rate.

Two additional lines of research challenge the iatrogenesis theory of DID: first, prevalence research conducted in cultures where DID is not well known, and second, evidence of chronic childhood abuse and dissociation in childhood among adults diagnosed with DID. Three classic studies have been conducted in cultures where DID was virtually unknown when the research was conducted. Researchers using structured interviews found DID in patients in China, despite the absence of DID in the Chinese psychiatric diagnostic manual.117 The Chinese study and also two conducted in central-eastern Turkey in the 1990s78,118—where public information about DID was absent—contradict the iatrogenesis thesis. In one of the Turkish studies,118 a representative sample of women from the general population (n = 994) was evaluated in three stages: participants completed a self-report measure of dissociation; two groups of participants, with high versus low scores, were administered the DDIS by a researcher blind to scores; and the two groups were then given clinical examinations (also blind to scores). The researchers were able to identify four cases of DID, all of whom reported childhood abuse or neglect.

The second line of research challenging the iatrogenesis theory of DID documents the existence of dissociation and severe trauma in childhood records of adults with DID. Researchers have found documented evidence of dissociative symptoms in childhood and adolescence in individuals who were not assessed or treated for DID until later in life (thus reducing the risk that these symptoms could have been suggested).11,13,119 Numerous studies have also found documentation of severe child abuse in adult patients diagnosed with DID.10,13,120,121 For example, in their review of the clinical records of 12 convicted murderers diagnosed with DID, Lewis and colleagues11 found objective documentation of child abuse (e.g., child protection agency reports, police reports) in 11 of the 12, and long-standing, marked dissociation in all of them. Further, Lewis and colleagues11(p 1709) noted that “contrary to the popular belief that probing questions will either instill false memories or encourage lying, especially in dissociative patients, of our 12 subjects, not one produced false memories or lied after inquiries regarding maltreatment. On the contrary, our subjects either denied or minimized their early experiences. We had to rely for the most part on objective records and on interviews with family and friends to discover that major abuse had occurred.” Notably, these inmates had already been sentenced; they were all unaware of having met diagnostic criteria for DID; and they made no effort to use the diagnosis or their trauma histories to benefit their legal cases.

Similarly, Swica and colleagues13 found documentation of early signs of dissociation in childhood records in all of the six men imprisoned for murder who were assessed and diagnosed with DID during participation in a research study. During their trials, the men were all unaware of having DID. And since their sentencing had already occurred, they had nothing to gain from DID being diagnosed while participating in the study. Their signs and symptoms of early dissociation included hearing voices (100%), having vivid imaginary companions (100%), amnesia (50%), and trance states (34%). Furthermore, evidence of severe childhood abuse has been found in medical, school, police, and child welfare records in 58%–100% of DID cases.11,13,121 These studies indicate that dissociative symptoms and a history of severe childhood trauma are present long before DID is suspected or diagnosed.

Perhaps the “iatrogenesis myth” exists because inappropriate therapeutic interventions can exacerbate symptoms if used with DID patients. The expert consensus DID treatment guidelines warn that inappropriate interventions may worsen DID symptoms, although few clinicians report using such interventions.66,122 No research evidence suggests that inappropriate treatment creates DID. The only study to date examining deterioration of symptoms among DID patients found that only a small minority (1.1%) worsened over more than one time-point in treatment and that deterioration was associated with revictimization or stressors in the patients’ lives rather than with the therapy they received.123 This rate of deterioration of symptoms compares favorably with those for other psychiatric disorders.

MYTH 5: DID IS THE SAME ENTITY AS BORDERLINE PERSONALITY DISORDER

Some authors suggest that the symptoms of DID represent a severe or overly imaginative presentation of BPD.124 The research described below, however, indicates that while DID and BPD can frequently be diagnosed in the same individual, they appear to be discrete disorders.125,126

One of the difficulties in differentiating BPD from DID has been the poor definition of the dissociation criterion of BPD in the DSM’s various editions. In DSM-5 this ninth criterion of BPD is “transient, stress-related paranoid ideation or severe dissociative symptoms.”1 The narrative text in DSM-5 defines dissociative symptoms in BPD (“e.g., depersonalization”) as “generally of insufficient severity or duration to warrant an additional diagnosis.” DSM-5 does not clarify that when additional types of dissociation are found in patients who meet the criteria for BPD—especially amnesia or identity alteration that are severe and not transient (i.e., amnesia or identity alteration that form an enduring feature of the patient’s presentation)—the additional diagnosis of a dissociative disorder should be considered, and that additional diagnostic assessment is recommended.

On the surface, BPD and DID appear to have similar psychological profiles and symptoms.124,127 Abrupt mood swings, identity disturbance, impulsive risk-taking behaviors, self-harm, and suicide attempts are common in both disorders. Indeed, early comparative studies found few differences on clinical comorbidity, history, or psychometric testing using the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory and the Millon Clinical Multiaxial Inventory.124,127 However, recent clinical observational studies, as well as systematic studies using structured interview data, have distinguished DID from BPD.59,128 Brand and Loewenstein59 review the clinical symptoms and psychosocial variables that distinguish DID from BPD: clinically, individuals with BPD show vacillating, less modulated emotions that shift according to external precipitants.59 In addition, individuals with BPD can generally recall their actions across different emotions and do not feel that those actions are alien or so uncharacteristic as to be disavowed.59,128 By contrast, individuals with DID have amnesia for some of their experiences while they are in dissociated personality states, and they also experience a marked discontinuity in their sense of self or sense of agency.1 Thus, the dissociated activity and intrusion of personality states into the individual’s consciousness may be experienced as separate or different from the self that they identify with or feel they can control. Accordingly, using SCID-D structured interview data, Boon and Draijer128 demonstrated that amnesia, identity confusion, and identity alteration were significantly more severe in individuals with DID than in cluster B personality disorder patients, most of whom had BPD. However, DID and BPD patients did not differ on the severity of depersonalization and derealization. Both groups had experienced trauma, although the DID group had much more severe and earlier trauma exposure.

BPD and DID can also be differentiated on the Rorschach inkblot test. Sixty-seven DID patients, compared to 40 BPD patients, showed greater self-reflective capacity, introspection, ability to modulate emotion, social interest, accurate perception, logical thinking, and ability to see others as potentially collaborative.58 A pilot Rorschach study found that compared to BPD patients, DID patients had more traumatic intrusions, greater internalization, and a tendency to engage in complex contemplation about the significance of events.129 The DID group consistently used a thinking-based problem-solving approach, rather than the vacillating approach characterized by shifting back and forth between emotion-based and thinking-based coping that has been documented among the BPD patients.129 These personality differences likely enable DID patients to develop a therapeutic relationship more easily than many BPD patients.

With regard to the frequent comorbidity between DID and BPD, studies assessing for both disorders have found that approximately 25% of BPD patients endorse symptoms suggesting possible dissociated personality states (e.g., disremembered actions, finding objects that they do not remember acquiring)126 and that 10%–24% of patients who meet criteria for BPD also meet criteria for DID.75,126,130,131 Likewise, a national random sample of experienced U.S. clinicians found that 11% of patients treated in the community for BPD met criteria for comorbid DID,84 and structured interview studies have found that 31%–73% of DID subjects meet criteria for comorbid BPD.12,72,132 Thus, about 30% or more of patients with DID do not meet full diagnostic criteria for BPD. In blind comparisons between non-BPD controls and college students who were interviewed for all dissociative disorders after screening positive for BPD, BPD comorbid with dissociative disorder was more common than was BPD alone (n = 58 vs. n = 22, respectively).130 It is important to note that despite its prevalence in patients with DID, BPD is not the most common personality disorder that is comorbid with DID. More common among individuals with DID are avoidant (76%–96%) and self-defeating (a proposed category in the appendix of DSM-III-R; 68%–94%) personality disorders, followed by BPD (53%–89%).132,133

When the comorbidity between BPD and DID is evaluated specifically, the patients with comorbid BPD and DID appear to be more severely impaired than individuals with either disorder alone. For example, the participants who had both disorders reported the highest level of amnesia and had the most severe overall dissociation scores.130 Similarly, individuals who meet criteria for both disorders have more psychiatric comorbidity and trauma exposure than individuals who meet criteria for only one,134 and they also report higher scores of dissociative amnesia.135

In the future, the neurobiology of BPD and DID might assist in their comparison. Preliminary imaging research in BPD suggests the prefrontal cortex may fail to inhibit excessive amygdala activation.136 By contrast, two patterns of activation that correspond to different personality states have been found in DID patients: neutral states are associated with overmodulation of affect and show corticolimbic inhibition, whereas trauma-related states are associated with undermodulation of affect and activation of the amygdala on positron emission tomography.62 Similarly, recent fMRI studies in DID found that the neutral states demonstrate emotional underactivation and that the trauma-related states demonstrate emotional overactivation.137,138 Perhaps BPD might be thought of as resembling the trauma-related state of DID with amygdala activation, whereas the dissociative pattern found in the neutral state in DID appears to be different from what is found in BPD.139 Additional research comparing these disorders is needed to further explore the early findings of neurobiological similarities and differences.

What remains open for debate is whether a personality disorder diagnosis may be given to DID patients, because attribution of a clinical phenomenon to a personality disorder is not indicated if it is related to another disorder—in this instance, DID. Hence, the DSM-5 criteria for BPD may be insufficient to diagnose a personality disorder because DID is not excluded. In this regard, some DID researchers have concluded that unmanaged trauma symptoms—including dissociation—may account for the high comorbidity of BPD in DID patients.75,131 For example, one study found that only a small group of DID patients still met BPD criteria after their trauma symptoms were stabilized.140 Resolution of this debate may hinge on whether patients diagnosed with BPD are conceptualized as having a severe personality disorder rather than a trauma-based disorder that involves dissociation as a central symptom.

Yet to be studied is the possibility that several overlapping etiological pathways—including trauma,4,141 attachment disruption,142–144 and genetics145–149—may contribute to the overlap in symptomatology between BPD and DID. In order to clarify which variables increase risk for one or both developmental outcomes, research that carefully screens for both DID and BPD is needed. The apparent phenomenological overlap between the two psychopathologies does not create an insurmountable obstacle for research, because distinct influences may be parsed out via statistical analysis.135,150 Screening for both disorders would prevent BPD and DID from constituting mutually confounding factors in research specifically about one or the other.150

The benefit of accurately diagnosing (1) BPD without DID, (2) DID without BPD, and (3) comorbid DID BPD is that treatment can be individualized to meet patients’ needs. A diagnosis of BPD without DID can lead clinicians to use empirically supported treatment for BPD. By contrast, the treatment of DID is different from the treatment of BPD and comprises three phases: stabilization, trauma processing, and integration (discussed below).66 Given the severity of illness found in individuals with comorbid BPD/DID, clinicians should emphasize skills acquisition and stabilization of trauma-related symptoms in an extended stabilization phase. Early detection of comorbid DID and BPD alerts the therapist to avoid trauma-processing work until the stabilization phase is complete. The trauma-processing phase should be approached cautiously in highly dissociative individuals, and only after they have developed the capacity both to contain intrusive trauma material and to use grounding techniques to manage dissociation.

In summary, DID and BPD appear to be separate, albeit frequently comorbid and overlapping, disorders that can be differentiated on validated structured and semistructured interviews, as well as on the Rorschach test. While the symptoms of DID and BPD overlap, preliminary indications are that the neurobiology of each is different. It is also possible that differences between DID and BPD may emerge regarding the respective etiological roles of trauma, attachment disruption, and genetics.

MYTH 6: DID TREATMENT IS HARMFUL TO PATIENTS

Some critics claim that DID treatment is harmful.52,69,151–153 This claim is inconsistent with empirical literature that documents improvements in the symptoms and functioning of DID patients when trauma treatment consistent with the expert consensus guidelines is provided.65,66

Before reviewing the empirical literature, we will present an overview of the DID treatment model. The first DID treatment guidelines were developed in 1994, with revisions in 1997, 2005, and 2011. The current standard of care for DID treatment is described in the International Society for the Study of Trauma and Dissociation’s Treatment Guidelines for Dissociative Identity Disorder in Adults.66 The DID experts who wrote the guidelines recommend a tri-phasic, trauma-focused psychotherapy. In the first stage, clinicians focus on safety issues, symptom stabilization, and establishment of a therapeutic alliance. Failure to stabilize the patient or a premature focus on detailed exploration of traumatic memories usually results in deterioration in functioning and a diminished sense of safety. In the second stage of treatment, following the ability to regulate affect and manage their symptoms, patients begin processing, grieving, and resolving trauma. In the third and final stage of treatment, patients integrate dissociated self-states and become more socially engaged.

Early case series and inpatient treatment studies demonstrate that treatment for DID is helpful, rather than harmful, across a wide range of clinical outcome measures.64,140,154–158 A meta-analysis of eight treatment outcome studies for any dissociative disorder yielded moderate to strong within-patient effect sizes for dissociative disorder treatment.64 While the authors noted methodological weaknesses, current treatment studies show improved methodology over the earlier studies. One of the largest prospective treatment studies is the Treatment of Patients with Dissociative Disorders (TOP DD) study, conducted by Brand and colleagues.159 The TOP DD study used a naturalistic design to collect data from 230 DID patients (as well as 50 patients with dissociative disorder not otherwise specified) and their treating clinicians. Patient and clinician reports indicate that, over 30 months of treatment, patients showed decreases in dissociative, posttraumatic, and depressive symptomatology, as well as decreases in hospitalizations, self-harm, drug use, and physical pain. Clinicians reported that patient functioning increased significantly over time, as did their social, volunteer, and academic involvement. Secondary analyses also demonstrated that patients with a stronger therapeutic alliance evidenced significantly greater decreases in dissociative, PTSD, and general distress symptoms.160

Crucial to discussion of whether DID treatment is harmful is the importance of dissociation-focused therapy. A study of consecutive admissions to a Norwegian inpatient trauma program found that dissociation does not substantially improve if amnesia and dissociated self-states are not directly addressed.161 The study, by Jepsen and colleagues, compared two groups of women who had experienced childhood sexual abuse—one without, and one with, a dissociative disorder (DID or dissociative disorder not otherwise specified). None of the dissociative disorder patients had been diagnosed or treated for a dissociative disorder, and dissociative disorder was not the focus of the inpatient treatment. Thus, the methods of this study reduce the possibility of therapist suggestion. Although both groups had some dissociative symptoms, the dissociative disorder group was more severely symptomatic. Both groups showed improvements in symptoms, although the effect sizes for change in dissociation were smaller for the dissociative disorder group than for the non–dissociative disorder group (d = .25 and .69, respectively). As a result of these findings, the hospital developed a specialized treatment program, currently being evaluated, for dissociative disorder patients (Jepsen E, personal communication, June 2013).

Large, diverse samples, standardized assessments, and longitudinal designs with lengthy follow-ups were utilized in the studies by Brand and colleagues159 and Jepsen and colleagues.161 However, neither study used untreated control groups or randomization. Additionally, Brand and colleagues’ TOP DD study159 had a high attrition rate over 30 months (approximately 50%), whereas Jepsen and colleagues161 had an impressive 3% patient attrition rate during a 12-month follow-up.

DID experts uniformly support the importance of recognizing and working with dissociated self-states.65 Clinicians in the TOP DD study reported frequently working with self- states.122 While it is not possible to conclude that working with self-states caused the decline in symptoms, these improvements occurred during treatment that involved specific work with dissociated self-states. This finding of consistent improvement is another line of research that challenges the conjecture that working with self-states harms DID patients.69,152

Brand and colleagues47 reviewed the evidence used to support claims of the alleged harmfulness of DID treatment. They did not find a single peer-reviewed study showing that treatment consistent with DID expert consensus guidelines harms patients. In fact, those who argue that DID treatment is harmful cite little of the actual DID treatment literature; instead, they cite theoretical and opinion pieces.52,69,151–153 In their review—from 2014—Brand and colleagues47 concluded that claims about the alleged harmfulness of DID treatment are based on non-peer-reviewed publications, misrepresentations of the data, autobiographical accounts written by patients, and misunderstandings about DID treatment and the phenomenology of DID.

In short, claims about the harmfulness of DID treatment lack empirical support. Rather, the evidence that treatment results in remediation of dissociation is sufficiently strong that critics have recently conceded that increases in dissociative symptoms do not result from DID psychotherapy.104 To the same effect, in a 2014 article in Psychological Bulletin, Dalenberg and colleagues49 responded to critics, noting that treatment consistent with the expert consensus guidelines benefits and stabilizes patients.

(end article)

#Sage Speaks#Lilith - 🏍️#host posts#alter post#did alter#did#dissociative identity disorder#traumagenic#did research#anti endo#endo dni#fuck endos#endos aren't real#anti endogenic#did is a disorder#did is caused by trauma#you can't have did w/o trauma#endos cope harder

55 notes

·

View notes

Text

I think that i only half ironically like hysteria better than like “oh ptsd” “oh dissociative disorder” “oh somatoform/conversion symptoms” No. fuck that. i have ghosts in my blood. and im crazy. and sometimes i go blind. And I need my barber to prescribe me a vibrator and cocaine

9 notes

·

View notes

Note

We’re looking into alters having different body conditions because we heard it’s possible and have been wondering if one alter of ours is lactose intolerant. They went dormant for a while and we had no symptoms, but they’re back and thus our symptoms are too. We’d also been questioning if another alter has BPD while the rest of us don’t. (We’re willing to accept it being psychosomatic or somatoform, but fact of the matter is that we’re experiencing it and its distressing, so it does matter to us).

While looking into it, we also found anecdotes of other systems having alters with many, many different conditions. And now we’re thinking that it’s not just lactose intolerance and BPD but a couple other things that specific alters have, too.

This, weirdly, makes us feel fake!? Even though there’s literally (anecdotal) evidence of this happening.

Alters can experience a lot of different psychological phenomena different from other alters, and that can have severe effects that your might not normally expect, up to and including actual blindness.

These things are definitely very possible, and allergies are something that can definitely be psychosomatic. And yes, that includes lactose intolerance.

The symptoms are still real and valid, but it's entirely possible that they're psychological in origin, causing a biological response in the body.

#ask box#pluralgang#plural#food allergies#lactose intolerance#multiplicity#system#systems#system stuff#endogenic#systemblr#psychology#placebo#health#plural things#food allergy#allergy#plurality#allergies

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

Okay, I need advice or information or something because I'm very confused right now.

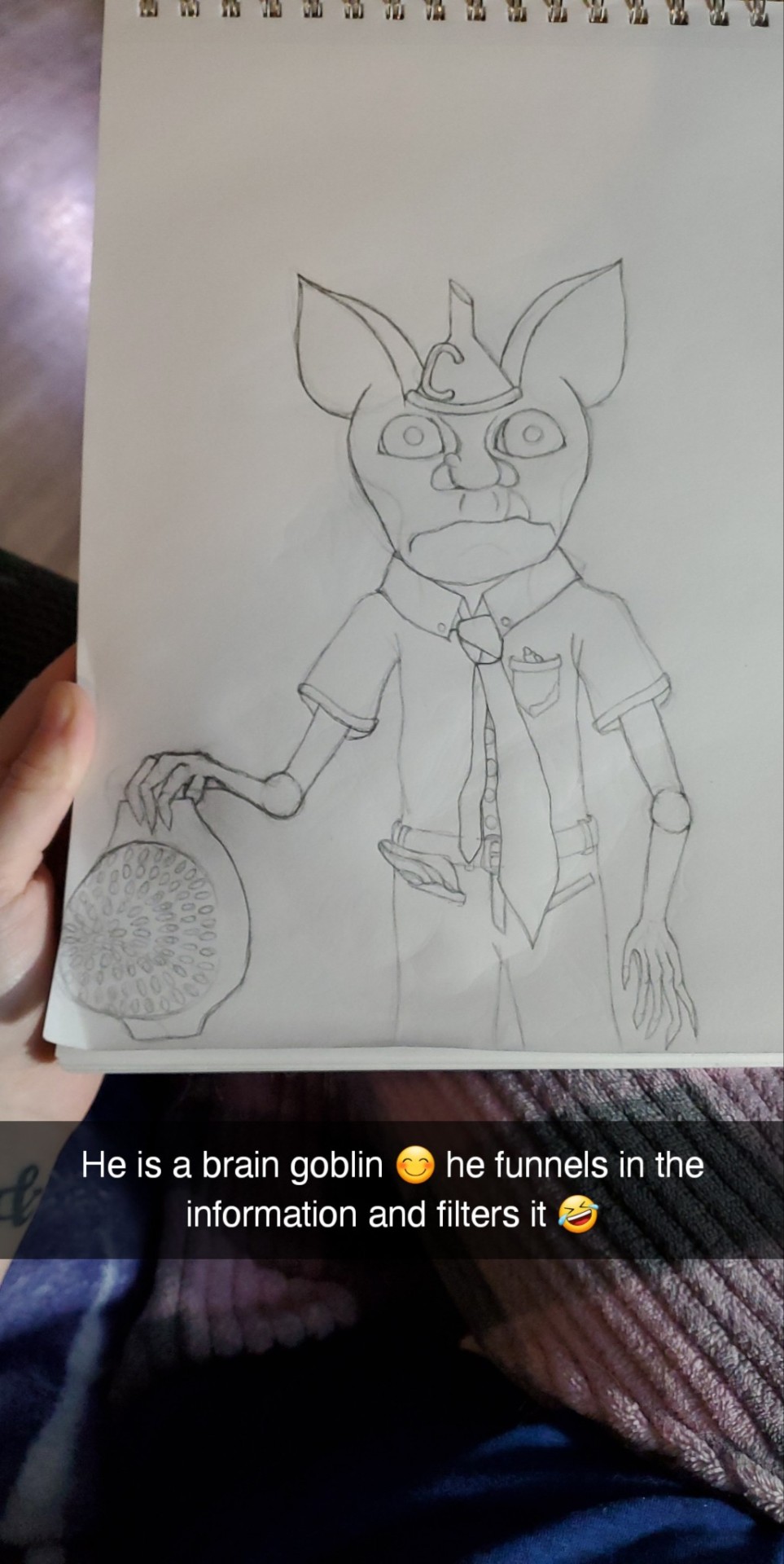

So the name "Neurodivergent Brain Goblins" comes from these bits of myself that I've named and given an identity to in order to help other people understand my brain.

I've had neuropsych testing done (4.5 hrs of testing, surveys, and forms). They agreed that I have C-PTSD and dissociative symptoms with a somatoform disorder, but they don't agree that I have DID because I don't lose time and don't have other personalities that take over/replace mine.

My brain goblins are their own people but also are just me. Mini little parts of me that sometimes control more of my life than I often do.

Reynold is my logic. He is my assistant manager who definitely wasn't given enough training and is more of a glorified babysitter than anything else 😅 I honor the amount of shit he puts up with every day. He is second in command and acts as a buffer to all the other brain goblins.

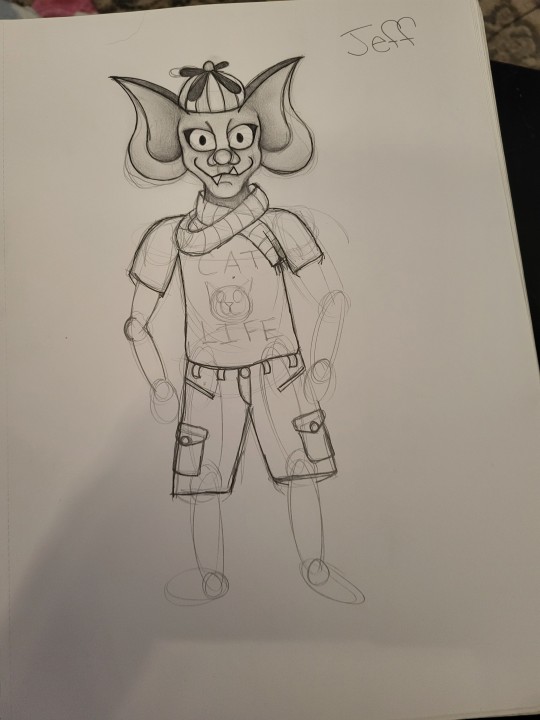

Then there is Jeff 🫠 I call him my ADHD goblin. Jeff loves buttons. He loves pushing them and watching them light up and hearing them make noise. Jeff also loves running around, jumping, making ridiculous noises, and seeing how many times he can do the same exact thing in a row before it pisses everyone else off 🤣 sometimes Reynold will give Jeff a tennis ball to go bounce against the wall for a while just so he can get some real work done.

(I'm not done drawing Jeff, but this is him so far 😊 he is a very mischievous little shit lol)

I also have Frank my OCD Goblin. He carries around an abacus instead of a calculator because 1. He is obsessed with numbers and 2. Physically moving the pieces to count calms his anxiety 😅. Frank loves simple repetitive tasks that he can do on repeat so he can count them over and over again. He often teams up with Jeff because of this and then they bug Reynold all day. Kind of a "hey! Hey! Hey check this out! Look what we can do! Hey!"

Bobby is my Autism Goblin 🤣 I love him so much but like sometimes I just.. he tries so hard and his effort is absolutely beautiful, but he just isn't good at any of it 🙃 he is the director of communication, so anytime I socialize Bobby shows up to help navigate talking. But like he just REALLY isn't good at it 🤣 the heart and soul he puts into it though is why he is still the communications director 🥰

I also have Manic Manny, Depression Dave, Sensory Sally. Though they like to work from behind the scenes. Their control is really strong but everything they do is by sneaking up and whispering in Reynolds ear and *poof* disappearing. He can't ever see them, but the weird creepy crawly feeling they give him makes him act on what they said every single time.

There are lots of other Goblins that work in this factory, but they are more like background characters? Like, everyone has a job, but most are just quiet office workers that help to keep the lights on 😅

If you have read this far thank you so much!! My question now is, what are my brain goblins? Is this DID or is it something else?? Tbh I don't really care what it is because these are my Brain Goblins and I love them no matter how much they annoy me 😅 but I also like learning information because sometimes it can really help me with managing life lol

#did osdd#did system#dissociative identity disorder#im so confused#they are goblins that live in my head#but those goblins are me#brain goblins#neurodivergent brain goblins#did

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

just got back from the clinic.

welp.., congrats to me it’s official. i have somatoform vegetative disorder. cool 😐

15 notes

·

View notes