#psychology

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

who up hating pop psychology

#mbti#aspd#npd#bpd#pop psych#trauma#dark empath#myth of 25#love language#male brain#female brain#myers briggs#borderline#narc#narc abuse#narcissism#sociopathy#sociopath#borderline abuse#pop psychology#psychology

65K notes

·

View notes

Text

Did you poison him for not pleasing you?

I had something like that happen after people asked me to have sex with two pedophiles.

ITS FUCKING HAPPENING

22K notes

·

View notes

Text

An explainer for why I don't fuck with algorithmic social media

If you give a pigeon a little button to peck that releases pigeon food, it will push the button when it's hungry.

If you give a pigeon a button to peck that releases food every 5 pecks, it will peck it more often.

If you give a pigeon a button to peck that releases food at a randomly selected, always shifting number of pecks, the pigeon will peck that fucking button all day long.

Algorithm based social media is not set up to give you the best most fun stuff all the time, it is set up to give you a bunch of stress and nothingness with a randomized reward of something that actually makes you happy, because they want you pecking that button all damn day. It is a slot machine of content, meant to keep you putting in quarters made of your time and attention till you've nothing left.

At least if I'm having a shit day on my own Tumblr home feed it's because I've made a bad choice about who to follow and I can fix it.

17K notes

·

View notes

Text

The opposite of anxiety is not calmness, it is desire. Anxiety and desire are two, often conflicting, orientations to the unknown. Both are tilted toward the future. Desire implies a willingness, or a need, to engage this unknown, while anxiety suggests a fear of it. Desire takes one out of oneself, into the possibility of relationship, but it also takes one deeper into oneself. Anxiety turns one back on oneself, but only onto the self that is already known. There is nothing mysterious about the anxious state; it leaves one teetering in an untenable and all too familiar isolation. There is rarely desire without some associated anxiety: We seem to be wired to have apprehension about that which we cannot control, so in this way, the two are not really complete opposites. But desire gives one a reason to tolerate anxiety and a willingness to push through it.

Open to Desire

Mark Epstein

6K notes

·

View notes

Text

somewhere along the line you realize that everyone is severely busy with their own emotional regulation efforts, their own sensitivities about themselves and with how their own mental image of themselves is holding up.

it’s both a little bit sad and freeing at the same time:

a little bit sad because you very rarely get interacted with and seen for who you really are at a given time. people are way too busy with themselves to ever truly see you.

and freeing, because… well, people are way too busy with themselves to ever truly see you so you might as well primarily care about your own wellbeing and not take things personally.

I mean, it can’t have been about you when the person you were interacting with was so preoccupied with themselves.

can someone teach me how to be emotionally regulated and not be sensitive or take things personally

#comedy of being human#growing up#psychology#therapy#self care#self improvement#self love#mental health#humans

7K notes

·

View notes

Text

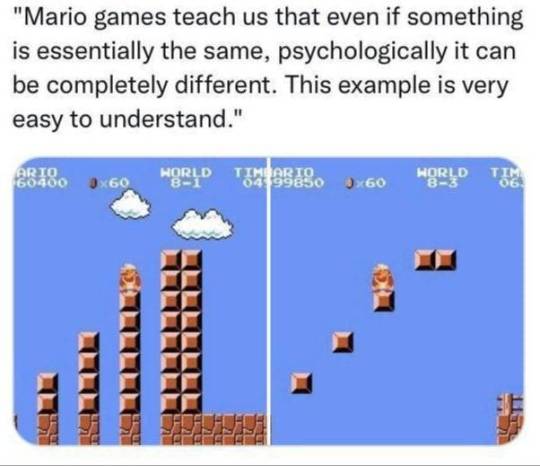

#mario#nintendo#nes#gaming#video games#super mario bros#retro#80s#psychology#super mario#super mario wonder#switch#nintendo switch#nostalgia#nostalgic#retrogaming

34K notes

·

View notes

Text

The worst part of studying psychology is that you empathize with the most evil people too, because all you can think of is the trauma that turned them into what they've become rather than what they've actually become.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

A reminder

———-

© Magdalena Koscianska, Instagram: magda.moonsavage | Check also my Tumblr photo blog, Shapes and Shivers

#my illustration#emotions#illustrators on tumblr#ilustracja#my quotes#neurodiversity#neurodiverse stuff#neurodiverse things#sexuality#mindset#mindscape#innerverse#artists on tumblr#fine line drawing#psychology#societyandculture

5K notes

·

View notes

Text

no cause this is literally on my AP psychology required reading list for the summer??

#woohoo#tcc shitpost#tcc tumblr#tccblr#tcc fandom#tcc thoughts#tcc columbine#tcc dylan#tcc eric#dylan 1999#dylan columbine#eric and dylan#funny#idk man#yayyy#yayoi#lol#eric columbine#eric 1999#books#chat is this a win#woooohooooo#tcctwt#psychology

114 notes

·

View notes

Note

Any tips/advice on how to write a character with bipolar disorder?? 🙏

Writing Notes: Bipolar Disorder

Bipolar Disorder - a treatable mental health condition marked by extreme changes in mood, thought, energy, and behavior.

Not a character flaw or a sign of personal weakness.

Previously known as manic depression because a person’s mood can alternate between the “poles” of mania (highs) and depression (lows).

These changes in mood, or “mood swings,” can last for hours, days, weeks or months.

Symptoms of Bipolar Disorder

MANIA: The “Highs” of Bipolar Disorder

Symptoms of mania include:

heightened mood, exaggerated optimism and self-confidence;

excessive irritability, aggressive behavior;

decreased need for sleep without experiencing fatigue;

grandiose thoughts, inflated sense of self-importance;

racing speech, racing thoughts, flight of ideas;

impulsiveness, poor judgment, easily distracted;

reckless behavior; and

in the most severe cases, delusions and hallucinations.

DEPRESSION: The “Lows” of Bipolar Disorder

Symptoms of depression include:

prolonged sadness or unexplained crying spells;

significant changes in appetite and sleep patterns;

irritability, anger, worry, agitation, anxiety;

pessimism, indifference;

loss of energy, persistent lethargy;

feelings of guilt, worthlessness;

inability to concentrate, indecisiveness;

inability to take pleasure in former interests, social withdrawal;

unexplained aches and pains; and

recurring thoughts of death or suicide.

Types of Bipolar Disorder

There are several types of bipolar disorder. Each kind is defined by the length, frequency, and pattern of episodes of mania and depression.

Mood swings that come with bipolar disorder are usually more severe than ordinary mood swings and symptoms can last weeks or months, severely disrupting a person’s life.

For example, depression can make a person unable to get out of bed or go to work or mania can cause a person to go for days without sleep.

Bipolar I Disorder - Characterized by one or more episodes of mania or mixed episodes (which is when you experience symptoms of both mania and depression).

Bipolar II Disorder - Diagnosed after one or more major depressive episodes and at least one episode of hypomania, with possible periods of level mood between episodes.

The highs in bipolar II, called hypomanias, are not as high as those in bipolar I (manias).

Bipolar II disorder is sometimes misdiagnosed as major depression if episodes of hypomania go unrecognized or unreported.

If you have recurring depressions that go away periodically and then return, ask yourself if you also have:

Had periods (lasting four or more days) when your mood was especially energetic or irritable?

Did you feel or did others say that you were doing or saying things that were unusual, abnormal or not like your usual self?

Were you:

Feeling abnormally self-confident or social?

Needing less sleep or more energetic?

Unusually talkative or hyper?

Irritable or quick to anger?

Thinking faster than usual?

More easily distracted/having trouble concentrating?

More goal-directed or productive at work, school or home?

More involved in pleasurable activities, such as spending or sex?

If so, talk to your health care provider about these energetic episodes, and find out if they might be hypomania. Getting a correct diagnosis of bipolar II disorder can help you find treatment that may also help lift your depression.

Some people with bipolar disorder may have milder symptoms.

For example, you may have hypomania instead of mania. With hypomania, you may feel very good and find that you can get a lot done.

You may not feel like anything is wrong. But your family and friends may notice your mood swings and changes in activity levels.

They may realize that your behavior is unusual for you.

After the hypomania, you might have severe depression.

Your mood episodes may last a week or 2 or sometimes longer. During an episode, symptoms usually occur every day for most of the day.

Diagnosis

BIPOLAR I DISORDER is diagnosed when a person experiences a manic episode. During a manic episode, people with bipolar I disorder experience an extreme increase in energy and mood changes, including feeling extremely happy or uncomfortably irritable. Some people with bipolar I disorder also experience depressive or hypomanic episodes, and most people with bipolar I disorder also have periods of neutral mood.

Symptoms of Bipolar I Disorder

Manic Episode. A manic episode is a period of at least 1 week when a person is extremely high-spirited or irritable most of the day for most days, possesses more energy than usual, and experiences at least 3 of the following changes in behavior:

Decreased need for sleep (e.g., feeling energetic despite significantly less sleep than usual).

Increased or faster speech.

Uncontrollable racing thoughts or quickly changing ideas or topics when speaking.

Distractibility.

Increased activity (e.g., restlessness, working on several projects at once).

Increased risky or impulsive behavior (e.g., reckless driving, spending sprees, sexual promiscuity).

These behaviors must represent a change from the person’s usual behavior and be clear to friends and family. Symptoms must be severe enough to cause dysfunction in work, family, or social activities and responsibilities. Symptoms of a manic episode commonly require hospital care to ensure safety.

During severe manic episodes, some people also experience disorganized thinking, false beliefs, and/or hallucinations, known as psychotic features.

Hypomanic Episode. A hypomanic episode, or hympomania, is characterized by less severe manic symptoms that need to last only 4 days in a row rather than a week. Hypomanic symptoms do not lead to the major problems in daily functioning that manic symptoms commonly cause.

Major Depressive Episode. A period of at least 2 weeks in which a person experiences intense sadness or despair or a loss of interest in acivities the person once enjoyed and at least 4 of the following symptoms:

Feelings of worthlessness or guilt.

Fatigue.

Increased or decreased sleep.

Increased or decreased appetite.

Restlessness (e.g., pacing) or slowed speech or movement.

Difficulty concentrating.

Frequent thoughts of death or suicide.

BIPOLAR II DISORDER. To diagnose bipolar II disorder in an individual, they must have at least 1 major depressive episode and at least 1 hypomanic episode (see above). With bipolar II, it is common that people return to their usual functioning between episodes. People with bipolar II disorder often first seek treatment as a result of their depressive episodes, since hypomanic episodes often feel pleasurable and can even increase performance at work or school.

People with bipolar II disorder frequently have other mental illnesses such as an anxiety disorder or substance use disorder, the latter of which can exacerbate symptoms of depression or hypomania.

CYCLOTHYMIC DISORDER is a milder form of bipolar disorder involving many "mood swings," with hypomania and depressive symptoms that occur frequently. People with cyclothymia experience emotional ups and downs but with less severe symptoms than bipolar I or II disorder.

Cyclothymic disorder symptoms include the following:

For at least 2 years, many periods of hypomanic and depressive symptoms, but the symptoms do not meet the criteria for hypomanic or depressive episodes.

During the 2-year period, the symptoms (mood swings) have lasted for at least half the time and have never stopped for more than 2 months.

Exams and Tests. To diagnose bipolar disorder, your health care provider may do some or all of the following:

Ask whether other family members have bipolar disorder

Ask about your recent mood swings and for how long you have had them

Perform a thorough exam and order lab tests to look for other illnesses that may be causing symptoms that resemble bipolar disorder

Talk to family members about your symptoms and overall health

Ask about any health problems you have and any medicines you take

Watch your behavior and mood

Possible Causes

Experts don't know what causes bipolar disorder.

They agree that many factors seem to play a role.

This includes environmental, mental health, and genetic factors.

Bipolar disorder tends to run in families.

Researchers are still trying to find genes that may be linked to it.

Treatment and Care

Even though symptoms often recur, recovery is possible.

With appropriate care, people with bipolar disorder can cope with their symptoms and live meaningful and productive lives.

There are a range of effective treatment options, typically a mix of medicines and psychological and psychosocial interventions.

Medicines are considered essential for treatment, but themselves are usually insufficient to achieve full recovery.

People with bipolar disorder should be treated with respect and dignity and should be meaningfully involved in care choices, including through shared decision-making regarding treatment and care, balancing effectiveness, side-effects and individual preferences.

The main goal of treatment is to:

Make the episodes less frequent and severe

Help you function well and enjoy your life at home and at work

Prevent self-injury and suicide

A combination of medication and talk therapy is most helpful. Often more than one medication is needed to keep the symptoms in check.

MOOD STABILIZERS. The best-known and oldest mood stabilizer is lithium carbonate, which can reduce the symptoms of mania and prevent them from returning. Although it is one of the oldest medicines used in psychiatry, and although many other drugs have been introduced in the meantime, much evidence shows that it is still the most effective of the available treatments.

Lithium also may reduce the risk of suicide.

If you take lithium, you have to have periodic blood tests to make sure the dose is high enough, but not too high.

Side effects include nausea, diarrhea, frequent urination, tremor (shaking) and diminished mental sharpness.

Lithium can cause some minor changes in tests that show how well your thyroid, kidney and heart are functioning.

These changes are usually not serious, but your doctor will want to know what your blood tests show before you start taking lithium.

You will have to get an electrocardiogram (EKG), thyroid and kidney function tests, and a blood test to count your white blood cells.

For many years, antiseizure medications (also called "anticonvulsants") have also been used to treat bipolar disorder.

The most common in use are valproic acid (Depakote) and lamotrigine (Lamictal).

A doctor may also recommend treatment with other antiseizure medications — gabapentin (Neurontin), topiramate (Topamax), or oxcarbazepine (Trileptal).

Some people tolerate valproic acid better than lithium.

Nausea, loss of appetite, diarrhea, sedation and tremor (shaking) are common when starting valproic acid, but, if these side effects occur, they tend to fade over time.

The medication also can cause weight gain.

Uncommon but serious side effects are damage to the liver and problems with blood platelets (platelets are necessary for the blood to clot).

Lamotrigine (Lamictal) may or may not be effective for treating a depression that is active, but some studies show that it is more effective than lithium for preventing the depression of bipolar disorder.

(Lithium, however, is more effective than lamotrigine in preventing mania.)

The most troubling side effect of lamotrigine is a severe rash — in rare cases, the rash can become dangerous.

To minimize the risk, usually the doctor will recommend a low dose to start and increase dosages very slowly.

Other common side effects include nausea and headache.

ANTIPSYCHOTIC MEDICATIONS. In recent years, studies have shown that some of the newer antipsychotic medications can be effective for controlling bipolar disorder symptoms.

Side effects often have to be balanced against the helpful effects of these drugs:

olanzapine: sleepiness, dry mouth, dizziness and weight gain

risperidone: sleepiness, restlessness and nausea

quetiapine: dry mouth, sleepiness, weight gain and dizziness

ziprasidone: sleepiness, dizziness, restlessness, nausea and tremor

aripiprazole: nausea, stomach upset, sleepiness (or sleeplessness) or restlessness

asenapine: sleepiness, restlessness, tremor, stiffness, dizziness, mouth or tongue numbness.

Some of these new antipsychotic drugs can increase the risk of diabetes and cause problems with blood lipids.

Olanzapine is associated with the greatest risk.

With risperidone, quetiapine and asenapine, the risk is moderate.

Ziprasidone and aripiprazole cause minimal weight change and not as much risk of diabetes.

ANTIANXIETY MEDICATIONS. Such as lorazepam (Ativan) and clonazepam (Klonopin) sometimes are used to calm the anxiety and agitation associated with a manic episode.

ANTIDEPRESSANTS. The use of antidepressants in bipolar disorder is controversial. Many psychiatrists avoid prescribing antidepressants because of evidence that they may trigger a manic episode or induce a pattern of rapid cycling. Once a diagnosis of bipolar disorder is made, therefore, many psychiatrists try to treat the illness using mood stabilizers.

Some studies, however, continue to show the value of antidepressant treatment to treat low mood, usually when a mood stabilizer or antipsychotic medication is also being prescribed.

There are so many different forms of bipolar disorder that it is impossible to establish one general rule.

Using an antidepressant alone may be justified in some cases, especially if other treatments have not given relief. This is another area where the pros and cons of treatment should be reviewed carefully with your doctor.

PSYCHOTHERAPY. Talk therapy (psychotherapy) is important in bipolar disorder as it provides education and support and helps a person come to terms with the illness. Therapy can help between mood episodes to help people recognize the early symptoms follow a course of treatment more closely. For depression, psychotherapy can help people develop coping strategies. Family education helps family members communicate and solve problems. When families are kept involved, patients adjust more easily, are more likely to make good decisions about their treatment and have a better quality of life. They have fewer episodes of illness, fewer days with symptoms and fewer admissions to the hospital.

Psychotherapy helps a person deal with painful consequences, practical difficulties, losses or embarrassment stemming from manic behavior.

A number of psychotherapy techniques may be helpful depending on the nature of the person's problems.

Cognitive behavioral therapy helps a person recognize patterns of thinking that may keep him or her from managing the illness well.

Psychodynamic, insight-oriented or interpersonal psychotherapy can help to sort out conflicts in important relationships or explore the history that has contributed to current problems.

If left untreated, a first episode of mania lasts an average of 2-4 months and a depressive episode up to 8 months or longer, but there can be many variations. If the person does not get treatment, episodes tend to become more frequent and last longer as time passes.

Self-Care. You can also take steps to help yourself. During periods of depression, consider the following:

Get help. If you think you may be depressed, see a healthcare provider right away.

Set realistic goals and don’t take on too much at a time.

Break large tasks into small ones. Set priorities and do what you can as you can.

Try to be with other people and confide in someone. It's usually better than being alone and secretive.

Do things that make you feel better. Going to a movie, gardening, or taking part in religious, social, or other activities may help. Doing something nice for someone else can also help you feel better.

Get regular exercise.

Expect your mood to get better slowly, not right away. Feeling better takes time.

Eat healthy, well-balanced meals.

Don't drink alcohol or use illegal drugs. These can make depression worse.

It’s best to postpone big decisions until the depression has lifted. Before making big decisions, such as changing jobs or getting married or divorced, discuss it with others who know you well and have a more objective view of your situation.

People don’t snap out of a depression. But with treatment they can feel a little better day by day.

Try to be patient and focus on the positives. It may help replace the negative thinking that is part of the depression, and the negative thoughts will disappear as your depression responds to treatment.

As difficult as it may be, tell your family and friends that you are not feeling well and let them help you.

Sources: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 ⚜ More: References ⚜ Writing Resources PDFs

Consider the above notes, and then the following tips & advice to further develop your character:

Writing about Mental Health Conditions

Character Development

You can find more details as well as some useful fact sheets in the sources. Speaking with a person/s with bipolar disorder would also lend valuable insight into your story, as well as doing further research on media portrayals of and by people with bipolar disorder. Hope this helps with your writing!

#anonymous#bipolar disorder#writing reference#writeblr#psychology#literature#dark academia#writers on tumblr#spilled ink#writing prompt#creative writing#light academia#writing ideas#writing inspiration#writing resources

96 notes

·

View notes

Text

van wasn’t just endlessly protective and giving with tai because they loved tai. they also were coping and had severe attachment issues because their mom literally would get drunk and look through them or fail to meet their eyes at all. van just wanted someone to look back at them, to love them, and they finally got that with tai but in the same morbid way that unhealed trauma is destined to repeat itself, van was caught in that as well with tai because half the time it wasn’t the tai she wanted and she was reliving the experience of giving giving giving in hopes of being enough to make tai be there for them too just like what they always wanted from their mom and never got.

#i have so much to say about van#i have so much to say about the PSYCHOLOGY of van#am i projecting?#yes.#yes i am#but#also van definitely is either avoidant or disorganized which makes this so fucking tragic#van palmer you mean the world to me#yellowjackets#taissa x van#taivan#van palmer#van yellowjackets#van yj#vanessa palmer#taissa turner#taivan yellowjackets#tai yellowjackets#taissa yellowjackets#tai turner#psychology

50 notes

·

View notes

Text

Parents who are afraid of "phases" aren't so much concerned about their kids' well-being -- they're afraid of potentially having to adopt a whole new lifestyle and mindset to accommodate the kid only to have it flipped like a table when the next "trend" comes along. It's largely about their own personal comfort and inertia, but this is unconscious. They look at the wonderful adventure of life and see an intolerable roller coaster.

“what if kids identify with something and it ends up just being a phase-?” good. stop teaching and expecting kids (and adults honestly) to formulate permanent traits and ideas of themselves. everything in life is a phase. that doesn’t make it any less legitimate while you experience it. let people explore themselves and know it’s okay if what you think about yourself changes.

146K notes

·

View notes

Text

Emotional numbness

#artists on tumblr#artwork#charcoal#digital art#my art#creature#fyp#fypシ#tumblr fyp#psychology#darkness#dark art#charcol#horror#creepy art#creepypasta#fypツ#fypage#mental illness#mental health#emotions#emotional#numbness#love yourself#love#dark aesthetic#scary#sketch#doodle#doodlysketch

31 notes

·

View notes