#swiss reformation

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

I found a quote of a Hutterite yelling at a pastor in 1525, and I couldn't stop myself turning it into something. Sloppy as fuck cause this is like, 10 minutes work.

#history#medieval history#early modern history#european history#swiss reformation#reformation#hutterite#anabaptist#take up your hoe and work#you godless bastard

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Roman Catholics and Orthodox have got to knock it off with "Protestants have brutalist corporate churches". A particular modern strain of Protestantism has hideous modern churches. It's a depressingly common strain, and arguably the dominant one in America, but it's either ignorant or dishonest to pretend as though all Protestants have ugly churches.

Behold:

Clockwise from top left:

St. Peter's Church, Geneva, canton of Geneva, Switzerland (Swiss Reformed)

Barnes Methodist Church, London, England, UK (Methodist)

Dutch Reformed Church, Newbury, New York state, USA (Dutch Reformed)

St. Jude's Church, Glasgow, Scotland, UK (Presbyterian)

#i'm not arguing for protestantism#i am arguing for honesty and accuracy in apologetics#christianity#theology#churches#protestantism#swiss reformed#methodism#dutch reformed#presbyterian

166 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Only fools, pure theorists, or apprentices fail to take public opinion into account.”

Jacques Necker was a Genevan banker and statesman who served as finance minister for Louis XVI. He was a reformer, but his innovations sometimes caused great discontent.

Born: 30 September 1732, Geneva, Switzerland

Died: 9 April 1804, Geneva, Switzerland

Swiss Origins: Necker was born in Geneva, Switzerland, in 1732. His Swiss background made him a foreigner in the French political landscape, and this sometimes influenced the perception of his policies.

Self-Financed Publication: Necker was known for his publication titled "Compte Rendu," or "Report on the Finances." This document, which detailed the state of France's finances, was unique in that Necker personally financed its publication. This move aimed to showcase transparency and gain public support.

Resignation through Illness: In 1781, Necker resigned from his position as Finance Minister, citing health reasons. His resignation was accepted, but he continued to influence French politics from behind the scenes. He was later recalled to office in 1788.

Criticized by Revolutionaries: Despite being initially celebrated for his efforts to improve financial transparency, Necker faced criticism from revolutionary figures like Maximilien Robespierre. They accused him of being too sympathetic to the monarchy and not fully supporting the revolutionary cause.

Exile in Switzerland: After the fall of the Bastille in 1789 and the escalation of the French Revolution, Necker resigned once again. Fearing for his safety, he sought refuge in Switzerland. His departure marked the end of his active political career.

#Jacques Necker#French Revolution#Finance Minister#Louis XVI#Economic Reforms#Enlightenment#Transparency in Government#Swiss Banker#Statesman#Political Reform#Public Finances#1789 Crisis#National Assembly#Royal Finances#Dismissal from Office#Necker Reports#French Monarchy#Social Unrest#Financial Management#Legacy of Jacques Necker#quoteoftheday#today on tumblr

1 note

·

View note

Text

Sometimes you have a meme in your heart that no one around you will understand.

#The best thing I've ever done with my university degree#The man kicked off the Swiss Reformation by eating a sausage during lent#Why does no one talk about him more?#Reformation#Protestants#Tudors#I knew a weed dealer in college who looked like Philipp Melanchthon#Martin Luther#Sausage Dinner

1 note

·

View note

Photo

On 11 March 1421 construction began on the Bern Minster under the direction of the Strasbourg master builder Matthäus Ensinger.

#Junkerngasse#11 March 1421#construction#Bern Minster#Gothic style#architecture#old town#cityscape#original photography#day trip#landmark#tourist attraction#Berner Münster#Swiss Reformed cathedral#church#exterior#Bern#Schweiz#Switzerland#anniversary#Swiss history

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

I know I just reblogged this but I came back to say that in a galaxy chock full of evil corporations and crime syndicates eluding the justice of the Republic, the Jedi needed to do more Heists and Scams. Give me Jedi grifters who use their heightened insight and persuasion to sell a con. Jedi hackers with astoundingly precise control of Force lightning and an entourage of one-of-a-kind helper droids. Jedi hitters who learned every form of lightsaber combat but specialize in nonlethal damage and rendering people unconscious. Jedi thieves who can pick a pocket after they've already walked away from the mark and unlock a safe from across the room. And one Jedi Master(mind) to keep them all working together as a team.

What I'm saying is, the rich and powerful, they take what they want. Jedi steal it back for you. Sometimes bad Jedi make the best good guys. We provide...leverage.

Jedi as serial scammers though. Every mission includes a sidequest to sabacc table for extra cash. Padawans on their first outing be like ‘but I thought the senate was funding this mission’ yes little one but they will ride our arses for every cent so let’s go fleece some rich asshole. He won’t even notice. You know how cops were invented to protect private property? Well jedi are here to protect your everything except your private property. *force tricks an atm into printing free money* that, my very young padawan, is something we call a victimless crime.

#Jedi#star wars#leverage#the AU that would ignite my soul#technically the Leverage team are probably closer to reformed Sith but you see my vision#the Jedi have a super swiss army knife of powers and half the time forget they have anything but the stabbing one#and sometimes the pushing one

14K notes

·

View notes

Text

Switzerland, Day 1 - Zurich

Switzerland, day 1, Zurich. Though Zug would be my base in Switzerland. A small town 30 minutes train ride from Zurich in the canton of Zug. Not really a base; my friend has been living there for over 15 years, Kim. Having no plans whatsoever for Switzerland (nothing new), Kim had kindly invited me to stay with her. Heading back to Europe it felt like going home, going back to familiarity. Having…

View On WordPress

#Carolingian#Carolingian dynasty#Charlemagne#Fraumünster#Funicular#Grossmunster#Huldrych Zwingli#King of the Franks#King of the Lombards#limmat#Pollyterrasse#Polybahn#Predigerkirche#Reformation of Switzerland#river Limmat#St. Peter Church#St. Peterskirche#Swiss-German#Switzerland#UBS Polybahn#Zurich

0 notes

Text

Cross-posting an essay I wrote for my Patreon since the post is free and open to the public.

Hello everyone! I hope you're relaxing as best you can this holiday season. I recently went to see Miyazaki's latest Ghibli movie, The Boy and the Heron, and I had some thoughts about it. If you're into art historical allusions and gently cranky opinions, please enjoy. I've attached a downloadable PDF in the Patreon post if you'd prefer to read it that way. Apologies for the formatting of the endnotes! Patreon's text posting does not allow for superscripts, which means all my notations are in awkward parentheses. Please note that this writing contains some mild spoilers for The Boy and the Heron.

Hayao Miyazaki’s 2023 feature animated film The Boy and the Heron reads as an extended meditation on grief and legacy. The Master of a grand tower seeks a descendant to carry on his maddening duty, balancing toy blocks of magical stone upon which the entire fabric of his little pocket of reality rests. The world’s foundations are frail and fleeting, and can pass away into the cold void of space should he neglect to maintain this task. The Master’s desire to pass the torch undergirds much of the film’s narrative.

(Isle of the Dead. Arnold Böcklin. 1880. Oil on Canvas. Kunstmuseum. Basel, Switzerland.)

Arnold Böcklin, a Swiss Symbolist(1) painter, was born on October 16 in 1827, the same year the Swiss Evangelical Reformed Church bought a plot of land in Florence from the Grand Duke of Tuscany, Leopold II, that had long been used for the burials of Protestants around Florence. It is colloquially known as The English Cemetery, so called because it was the resting place of many Anglophones and Protestants around Tuscany, and Böcklin frequented this cemetery—his workshop was adjacent and his infant daughter Maria was buried there. In 1880, he drew inspiration from the cemetery, a lone plot of Protestant land among a sea of Catholic graveyards, and began to paint what would be the first of six images entitled Isle of the Dead. An oil on canvas piece, it depicts a moody little island mausoleum crowned with a gently swaying grove of cypresses, a type of tree common in European cemeteries and some of which are referred to as arborvitae. A figure on a boat, presumably Charon, ferries a soul toward the island and away from the viewer.

(Photo of The English Cemetery in Florence. Samuli Lintula. 2006.)

The Isle of the Dead paintings varied slightly from version to version, with figures and names added and removed to suit the needs of the time or the commissioner. The painting was glowingly referenced and remained fairly popular throughout the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The painting used to be inescapable in much of European popular culture. Professor Okulicz-Kozaryn, a philologist (someone with a deep interest in the ways language and cultural canons evolve)(2) observed that the painting, like many other works in its time, was itself iterative and became widely reiterated and referenced among its contemporaries. It became something like Romantic kitsch in the eyes of modern art critics, overwrought and excessively Byronic. I imagine Miyazaki might also resent a work of that level of manufactured ubiquity, as Miyazaki famously held Disney animated films in contempt (3). Miyazaki’s films are popularly aspirational to young animators and cartoonists, but gestures at imitation typically fall well short, often reducing Miyazaki’s weighty films to kitschy images of saccharine vibes and a lazy indulgence in a sort of empty magical domestic coziness. Being trapped in a realm of rote sentiment by an uncritical, unthoughtful viewership is its own Isle of Death.

(Still from The Boy and the Heron, 2023. Studio Ghibli.)

The Boy and the Heron follows a familiar narrative arc to many of Miyazaki’s other films: a child must journey through a magical and quietly menacing world in order to rescue their loved ones. This arc is an echo of Satsuki’s journey to find Mei in My Neighbor Totoro (1988) and Chihiro’s journey to rescue her parents Spirited Away (2001). To better understand Miyazaki’s fixation with this particular character journey, it can be instructive to watch Lev Atamanov’s 1957 animated film, The Snow Queen (4)(5), a beautifully realized take on Hans Christian Andersen’s 1844 children’s story (6)(7). Mahito’s journey continues in this tradition, as the boy travels into a painted world to rescue his new stepmother from a mysterious tower.

Throughout the film, Miyazaki visually references Isle of the Dead. Transported to a surreal world, Mahito initially awakens on a little green island with a gated mausoleum crowned with cypress trees. He is accosted by hungry pelicans before being rescued by a fisherwoman named Kiriko. After a day of catching and gutting fish, Mahito wakes up under the fisherwoman’s dining table, surrounded by kokeshi—little wooden dolls—in the shapes of the old women who run Mahito’s family’s rural household. Mahito is told they must not be touched, as the kokeshi are wards set up for his protection. There is a popular urban legend associated with the kokeshi wherein they act as stand-ins for victims of infanticide, though there seems to be very little available writing to support this legend. Still, it’s a neat little trick that Miyazaki pulls, placing a stray reference to a local legend of unverifiable provenance that persists in the popular imagination, like the effect of fairy stories passed on through oral retellings, continually remolded each new iteration.

(Still from The Boy and the Heron, 2023. Studio Ghibli.)

Kiriko’s job in this strange landscape is to catch fish to nourish unborn spirits, the adorable floating warawara, before they can attempt to ascend on a journey into the world of the living. Their journey is thwarted by flocks of supernatural pelicans, who swarm the warawara and devour them. This seems to nod to the association of pelicans with death in mythologies around the world, especially in relationship to children (8). Miyazaki’s pelicans contemplate the passing of their generations as each successive generation seems to regress, their capacity to fulfill their roles steadily diminishing.

(Still from The Boy and the Heron, 2023. Studio Ghibli.)

As Mahito’s adventure continues, we find the landscapes changing away from Böcklin’s Isle of the Dead into more familiar Ghibli territories as we start to see spaces inspired by one of Studio Ghibli’s aesthetic mainstays, Naohisa Inoue and his explorations of the fantasy realms of Iblard. He might be most familiar to Ghibli enthusiasts as the background artists for the more fantastical elements of Whisper of the Heart (1995).

(Naohisa Inoue, for Iblard Jikan, 2007. Studio Ghibli.)

By the time we arrive at the climax of The Boy and the Heron, the fantasy island environment starts to resemble English takes on Italian gardens, the likes of which captivated illustrators and commercial artists of the early 20th century such as Maxfield Parrish. This appears to be a return to one of Böcklin’s later paintings, The Island of Life (1888), a somewhat tongue-in-cheek reaction to the overwhelming presence of Isle of the Dead in his life and career. The Island of Life depicts a little spot of land amid an ocean very like the one on which Isle of the Dead’s somber mausoleum is depicted, except this time the figures are lively and engaged with each other, the vegetation lush and colorful, replete with pink flowers and palm fronds.

(Island of Life. Arnold Böcklin. Oil on canvas. 1888. Kunstmuseum. Basel, Switzerland.)

In 2022, Russia’s State Hermitage Museum in Saint Petersburg acquired the sixth and final Isle of the Dead painting. In the last year of his life, Arnold Böcklin would paint this image in collaboration with his son Carlo Böcklin, himself an artist and an architect. Arnold Böcklin spent three years painting the same image three times over at the site of his infant daughter’s grave, trapped on the Isle of the Dead. By the time of his death in 1901 at age 74, Böcklin would be survived by only five of his fourteen children. That the final Isle of the Dead painting would be a collaboration between father and son seemed a little ironic considering Hayao Miyazaki’s reticence in passing on his own legacy. Like the old Master in The Boy and the Heron, Miyazaki finds himself with no true successors.

The Master of the Tower's beautiful islands of painted glass fade into nothing as Mahito, his only worthy descendant, departs to live his own life, fulfilling the thesis of Genzaburo Yoshino’s 1937 book How Do You Live?, published three years after Carlo Böcklin’s death. In evoking Yoshino and Böcklin’s works, Hayao Miyazaki’s The Boy and the Heron suggests that, like his character the Master, Miyazaki himself must make peace with the notion that he has no heirs to his legacy, and that those whom he wished to follow in his footsteps might be best served by finding their own paths.

(Isle of the Dead. Arnold and Carlo Böcklin. Oil on canvas. 1901. The State Hermitage Museum. Saint Petersburg, Russia.)

INFORMAL ENDNOTES

1 - Symbolists are sort of tough to nail down. They were started as a literary movement to 1 distinguish themselves from the Decadents, but their manifesto was so vague that critics and academics fight about it to this day. The long and the short of it is that the Symbolists made generous use of a lot of metaphorical imagery in their work. They borrow a lot of icons from antiquity, echo the moody aesthetics from the Romantics, maintained an emphasis on figurative imagery more so than the Surrealists, and were only slightly more technically married to the trappings of traditionalist academic painters than Modernists and Impressionists. They're extremely vibes-forward.

2 - Okulicz-Kozaryn, Radosław. Predilection of Modernism for Variations. Ciulionis' Serenity among Different Developments of the Theme of Toteninsel. ACTA Academiae Artium Vilnensis 59. 2010. The article is incredibly cranky and very funny to read in parts. Contains a lot of observations I found to be helpful in placing Isle of the Dead within its context.

3 - "From my perspective, even if they are lightweight in nature, the more popular and common films still must be filled with a purity of emotion. There are few barriers to entry into these films-they will invite anyone in but the barriers to exit must be high and purifying. Films must also not be produced out of idle nervousness or boredom, or be used to recognise, emphasise, or amplify vulgarity. And in that context, I must say that I hate Disney's works. The barrier to both the entry and exit of Disney films is too low and too wide. To me, they show nothing but contempt for the audience." from Miyazaki's own writing in his collection of essays, Starting Point, published in 2014 from VIZ Media.

4 - You can watch the movie here in its original Russian with English closed captions here.

5 If you want to learn more about the making of Atamanoy's The Snow Queen, Animation Obsessive wrote a neat little article about it. It's a good overview, though I have to gently disagree with some of its conclusions about the irony of Miyazaki hating Disney and loving Snow Queen, which draws inspiration from Bambi. Feature film animation as we know it hadonly been around a few decades by 1957, and I find it specious, particularly as a comic artistand author, to see someone conflating an entire form with the character of its content, especially in the relative infancy of the form. But that's just one hot take. The rest of the essay is lovely.

6 - Miyazaki loves this movie. He blurbed it in a Japanese re-release of it in 2007.

7 - Julia Alekseyeva interprets Princess Mononoke as an iteration of Atamanov's The Snow Queen, arguing that San, the wolf princess, is Miyazaki's homage to Atamanoy's little robber girl character.

8 - Hart, George. The Routledge Dictionary of Egyptian Gods And Goddesses. Routledge Dictionaries. Abingdon, United Kingdom: Routledge. 2005.

#hayao miyazaki#the boy and the heron#how do you live#arnold böcklin#carlo böcklin#symbolists#symbolism#animation#the snow queen#lev atamanov#naohisa inoue#the endnotes are very very informal aksjlsksakjd#sorry to actual essayists

526 notes

·

View notes

Text

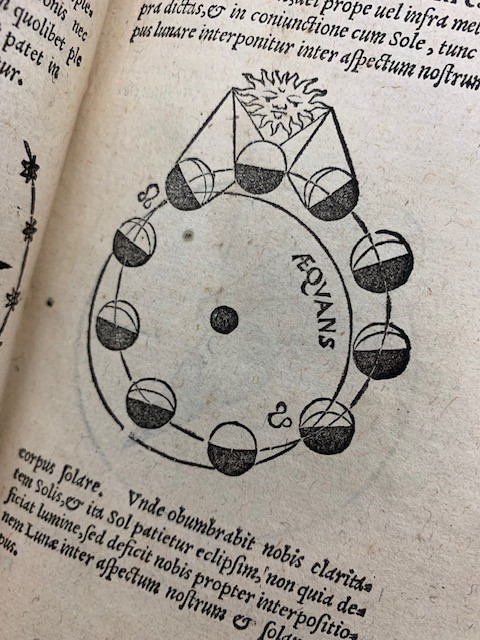

Eclipse(s)!

We are pleased to be positioned on Earth like one of figures in the first picture and will get to experience the 2024 solar eclipse!

These diagrams illustrating solar and lunar eclipses are from a 16th century book of astronomy. For more on this interesting little book (including its volvelles, and an inscription by Swiss Reformed theologian Simon Sulzer) see earlier post here.

Sacro Bosco, Joannes de. Libellus de sphaera : Accessit eiusdem autoris computus ecclesiasticus, et alia quaedam, in studiosorum gratiam edita...Vitebergae : Per Iohannem Crationem, 1558.

127 notes

·

View notes

Text

why can't you just say Calvinist

#been a Protestant all my life went to Protestant and Catholic schools never heard the phrase 'swiss reformed' in my life#now suddenly most of us are swiss reformed?

204 notes

·

View notes

Text

It’s a well-known fact that Hugo was deeply invested in reforming the penitentiary system and led a lifelong campaign against the death penalty. He first saw the conditions of imprisonment for those condemned to death and hard labour while visiting the prison of Bicêtre with his friend David d’Angers (a sculptor) in 1828. Their main intent was to preserve the gothic past and explore the ancient prison building. It was easy to get inside the jail because prisons at that time were open to the public. David Bellos explains:

“jails and dungeons were considered picturesque, and tourists in Paris visited all kinds of places that modern visitors shun. A prim Swiss student who came to Paris in 1830, for example, whiled away a Sunday afternoon at the women’s ward in a lunatic asylum and then dropped in at the morgue, just to see. Fashionable interest in ruins and medieval remains and a widely shared taste for the quaint and the bizarre — the main components of Romanticism when reduced to a statement of style — provided respectable cover for interests now served by the noirest genre of film.”

71 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Zwingli's Persecution of the Anabaptists

Huldrych Zwingli (l. 1484-1531) broke with the Church in 1522 and defended his beliefs at the First Disputation in 1523, encouraging many people in Zürich to embrace his teachings. Among his followers was a group, soon known as Anabaptists, who felt he had compromised himself at the Second Disputation, and they were then persecuted for their convictions.

Zwingli advocated for rejection of Catholic doctrine and practice and strict adherence to the authority of the scriptures. Zwingli's 67 Articles, presented at the First Disputation at which he denounced the Church as unbiblical, inspired a number of his adherents to take his claims to their natural conclusion that the Bible should be understood literally as God's word and its precepts followed faithfully without picking and choosing only what suited one's interests. When the Bible stated, "Thou Shalt Not Kill", they claimed, it meant a Christian should not take the life of another no matter the circumstances and, further, since there was no mention of infant baptism in the Bible, this practice should be rejected in favor of adult baptism. Zwingli rejected both of these challenges.

At the Second Disputation of 1523, Zwingli compromised on a number of points including infant baptism, alienating some of his more ardent supporters including Conrad Grebel (l. c. 1498-1526) and Felix Manz (l. c. 1498-1527) who formed their own Christian community, the Swiss Brethren, notable for their practice of adult baptism. Their opponents, who included Zwingli, called them Anabaptists (rebaptizers), and considered them dangerous radicals as they refused military service, denounced tithes, and challenged both civil and ecclesiastical authority.

When the city council of Zürich condemned them through a mandate, and when four of them were executed as heretics in 1527, including Manz, Zwingli made no objection. He had already spoken out against them as extremists who threatened the success of his movement, and he seems to have been relieved when the Anabaptist community left Zürich after the executions. Their exodus was only the beginning of the Anabaptist reform movement, however, which continued to spread throughout Europe despite severe persecution from religious and secular authorities. The Anabaptist sect went on to influence the development of others still practicing today, including the Amish and Mennonites.

Disputation & Division

Zwingli began his reform movement in 1519, as soon as he was appointed the people's priest of the Grossmünster (Great Church) in Zürich, by rejecting the Church's liturgy in Latin and reading from the Gospel of Matthew in the vernacular while interpreting and commenting on it. This encouraged members of his congregation to form their own Bible-study groups, which met in members' homes and applied Zwingli's teachings to interpret scripture.

In 1522, Zwingli broke with the Church over an event known as the Affair of the Sausage, when some members of his congregation (with Zwingli in attendance) broke the Lenten fast and the prohibition on eating meat by serving sausage at dinner. Zwingli defended this practice, denouncing Lenten fasting – and Lent itself – as unbiblical. He defined his stand in two sermons, Regarding the Choice and Freedom of Foods and On Rejecting Lent and Protecting Christian Liberty from Man-Made Obligations, and then further clarified his views through his 67 Articles delivered at the First Disputation with Catholic delegates in January 1523.

Zwingli's stand at the First Disputation inspired his more zealous supporters to fully embrace his call for the supremacy of biblical authority over any other, ecclesiastical or civil, and the Bible study led by Conrad Grebel and Felix Manz began advocating for a radical revision of Christian practice completely in accordance with scripture. Scholar Randolph C. Head comments:

Zwingli's sermons unleashed powerful responses from his audiences, which included Zurich's population, rich and poor, and clergy and laity from the surrounding areas…the broad (though by no means unanimous) support Zwingli's movement enjoyed by 1525 suggests many listeners found his sermons persuasive. Zwingli's impact was amplified by a number of Bible-study circles that formed in Zurich, whose participants often became proselytizers for increasingly bold reform projects. (Rublack, 170-171)

Although Zwingli had inspired this movement, he rejected their proposals as too extreme. At the Second Disputation in 1523, Zwingli completely rejected the views of Grebel and Manz and compromised on various issues with the Zürich city council. Head notes, "among the most pressing issues were clerical celibacy, the use of images in ceremonies, and the economic obligations of the laity to the church, especially tithes" (Rublack, 171). Zwingli agreed with Grebel and the others on the first two points but not on tithes, and he also rejected their claim that infant baptism was unbiblical and condemned them as dangerous rebels.

Grebel, Manz, and others in their circle, including George Blaurock (l. c. 1491-1529), felt betrayed by Zwingli and formed the Swiss Brethren, a counter- – and more extreme – reform movement to his own. Zwingli met with them in 1524 to reconcile, but no compromise could be reached. In response, Zwingli published his sermon Whoever Causes Unrest, denouncing the new movement as divisive – the same charge the Catholics had brought against Zwingli at the First Disputation – and this led to another disputation in early January 1525 to resolve the issue. Zwingli won this debate as he had the others, especially on the point of infant baptism. The city council then issued a mandate that anyone refusing to have their babies baptized must leave the city.

Continue reading...

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Just saw this excerpt from 17th century Swiss Reformed theologian, Johanne Heidegger:

15 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi! Hope you're doing well!

So. On the note of Tyler Seguin. Tyler Seguin, current stars Center and Alternate to Captain Jamie Benn, is known a little bit as a sort of a reformed party boy, who has (had?) fun night outs and such, and immensely talented and skilled. Dallas Stars, now, but first, a little context.

He played for three, two? seasons with the Boston bruins right after he was drafted 2nd overall in 2010. who were a terrible cesspool at the time, around the 2010s seasons, and was generally treated. Not well.

The coach had his own issues, an old school "tough love" kind in the wrong way, (ahem, julien).

Seguin was a healthy scratch, in the first two playoffs of that 10-11 season, and he had scored goals and points in his first career playoff game, and they won the Stanley cup. (He contributed to immensely to it.) Amidst all this glory and insane stuff, and his Swiss league achievements and hat tricks during the lockout, was a shit ton of drama.

There was a lot of inter team below the surface conflict, while the media was basically left to rip into Seguin for without team support, talk about guarding his room, buddy systems, so he didn't go out and had wild nights, a way overblown reputation and criticism. Including from fellow teammates.

Before he got traded, rumours about his "hard party lifestyle" being the reason went around, and Gm Chiarelli (paraphrasing to shorten) said "it's about the focus, little things, play prep, not a strictly on ice decision but not about extracurricular" (massive side eye.) he took a lot of media heat for the playoffs loss in the 12-13 season.

Oh and apparently a last straw was when he missed a mandatory team breakfast because of a wrong alarm, He was a healthy scratch off the roster for the game that day.

The best thing to happen to him was him leaving the Bruins. He joined the stars, a far more supportive team, and formed a close friendship with Jamie Benn, stars captain. His production and consistent rise helped clinch the stars a playoff spot, in eighth, for the first time since 2008.

You should watch their videos with Dude Perfect, those are fun! But anyways, Tyler Seguin may be fun loving, but he is so so intensely hockey minded, and the Dallas stars was truly a much better, more supportive team to him that could give him the space to grow as both player, playmaker and person. He is currently unfortunately out on a rough IR, hip injury. He's just, so good. Leading and cheer and all that.

Point is, I love him <3, and I would adore seeing him in your art!!! I've been a long time fan of yours and it's so good to see u locked into nhl. it would be so very lovely! I'm adding some pictures below. Thank you for entertaining such a long drop, and there's so much more to him, but these are the basics. I'm feeling hype cuz the stars won today's game.

- atlas / @tynedtime

This is so LONG LMAO but perfect…. Yes I’m moved. I will be reading his Wikipedia page before bed and adding him to my list… perhaps even searching his name on TikTok mhm mhmmmmmm

Ppl should do this more often.. lore drop in the box guys add more pookies to my roster I have nothing to draw but non f1 ppl until March feed me

#rubbing my hands together and grinning evilly#babe wake up new pookie just dropped#and his name is Seguin like the town..#THE TOWN IN TEXAS#yes he was meant to play for the stars#fated.#adding this to my beliefs system#I also feel like I’ve heard so much about this man his name is so familiar….#ask anni#this is perfect exactly what I wanted

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Last Supper

Artist: Hans Holbein the Younger (German-Swiss, 1498–1543)

Genre: Religious Art

Date: circa 1524-1525

Medium: Oil on Panel

Collection: Kunstmuseum Basel, Switzerland

The Last Supper is the final meal that, in the Gospel accounts, Jesus shared with his apostles in Jerusalem before his crucifixion. The Last Supper is commemorated by Christians especially on Holy Thursday.

Holbein painted his version of the subject under the influence of Leonardo da Vinci's The Last Supper, which he may have seen on a visit to northern Italy or have known from prints. Only nine of the apostles appear in Holbein's picture, because the outer boards of the painting, which was part of an altarpiece, were lost during iconoclastic riots by reformers in Basel. The head of Christ was sawn out of the picture at one time, and dents from hammer blows are visible on the work. According to the 16th-century inventory of the Amerbach collection, the damaged painting was "coarsely" (aber vnfletig) glued back together. It was often repainted over the centuries and has only been restored to Holbein's work since 1988, though some paint and subtle glazes have been lost.

#oil on panel painting#religious art#last supper#jesus#jesus's disciples#table#meal#supper#16th century painting#german painter#hans holbein the younger#new testament#bible gospels#christian art#christianity

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

ALRIGHT. I don’t usually do politics on this website but it’s a special occasion and I Know people are struggling. So, with the preface that I’m praying for yall, and praying for the new president (Lord knows he's gonna need it and we’re gonna need him to have it) - Here are the survival rules for the next four years:

None of you are allowed to die or disappear. I have in fact made it illegal. You start slipping, you Tell People. You remind yourself of something to hold onto and you keep doing that.

We Pray Every Day Now. Every Hour. Look, sometimes the ‘all powers and princes of the world are put in their places by the Lord’ means He has allowed us to make our own dumbass decisions. Free will is still a thing so here we are. But what is ALSO true is ‘God works out all things for good’ so until we can see it with our eyeballs, we walk in faith. This will be worked out for good. We have a promise.

We Pay Attention. We don’t watch the Cheeto man give speeches, it will just cause rage bc he doesn’t know how to talk like anything other than a NYC monopoly man. That includes the dang Instagram and Twitter clips, none of that shit is helpful and most of it is out of context. instead we keep track of every reform, every law passed. If regulations are loosened, we stop consuming the product. If pay is cut we stop buying from the company. The thing he cares about more than anything is the economy, your money is a second smaller vote you use every single day to tell his supporters they were right or wrong.

Yea you can take a job he creates or a handout he gives, if there are any. people who voted for him certainly will, and at the end of the day you will not change things by refusing help based on a sense of Justice that will save nobody.

if you suddenly have to wait four years for something you had planned, be that whatever it may be, I’m sorry. That’s frustrating and difficult. I’m sure you’ve heard ‘just wait a little longer’ a thousand times, so I won’t say that. I’ll just say, fill this time so full of good you don’t have room to wallow in the bad. Make a friend, join a club, start a hobby, play an instrument, learn to sing, write a book, learn to code and make a video game. Do something worthwhile, so when you look back on the time, you don’t feel like the years were wasted, because that more than anything will Ruin the way you feel and live in your body and mind.

when you’re talking to family about this who are happy about it, focus on love. Focus on the value of human life, the value of charity and kindness, use language they’re going to understand. Don’t say crap like “he’s a greedy capitalist who’s gonna fund a war-“ say “I’m concerned that he talks a lot about Christian values but doesn’t actually care as much about charity and helping the poor as he does getting richer.”

Read the Bible. I don’t believe it matters if you’re not a Christian, you should still read it, and you should go into it with at least a little willingness to learn. It’s not misogynistic, it’s not racist, it’s not classist, and it’s very VERY anti-the capitalist system we use in America today. YES the church often supports those things today, WE KNOW. We’re fallen people in a fallible system with a cultural upbringing that sometimes conflicts with the Bible while insisting it doesn’t. Understanding the values and beliefs of the people this administration SAYS it supports will be helpful later, when it starts doing things directly against those values and beliefs. And, more important than any political ideology, I want you to read the Bible because it’s true. Whether you believe it or not, you are loved and valued by a God that is so much bigger than anything happening in this nation and nothing will ever compare to that knowledge. Certainly not a president.

(Don’t read the KJV, it’s got more mistranslations than Swiss cheese has holes, I personally like the NIV, but there are plenty of options. Find one translated by a woman. A good litmus test right in the beginning is if the creation story makes Eve sound barely important and a slave to Adam: if it does, you might have a scuffed translation. She’s made completely equal, and the word describing her translated as ‘helper’ is translated ‘warrior’ everywhere else.)

LOVE ONE ANOTHER. Hold onto what really matters, stick up for your disabled and minority friends and peers and don’t let their accommodations slip an inch further than you absolutely have to. Pray for one another if you do, even if none of your friends believe. It’s worth it more now than ever. Do not let despair turn you towards sin and hate and blank apathy, remain strong in the Lord if you’re a Christian and if you aren’t, the advice honestly still applies. Stick up for what is right. Work for what you believe in. Don’t let anger make you stupid or impulsive. Love those around you, even if your first impression leads you to think they don’t deserve it. In the end, this will pass, and you will live on with whoever you were over these four years. You, as you one single person, are more powerful to affect the future than this entire presidential administration, because you will be IN the future, and it will only be a paragraph in a textbook. Live like it, and love like it. I love you all, and I’m praying for you.

9 notes

·

View notes