#schizophrenia advocate

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

My Story Living with Schizophrenia: A Journey Working In Progress

Hello, my name is Rain, and this is my story of living with schizophrenia. It's a journey that has shaped me in ways I never anticipated, filled with struggles, self-discovery, and ultimately, resilience. I want to share my experiences to help others understand what it's like to live with this condition and to foster a sense of connection and hope for those facing similar challenges.

The Early Years: A Cry for Help

My parents took the advice of medical professionals and placed me on ADHD medication. However, the medication had the opposite effect; instead of helping me, it left me in a fog. I struggled to stay awake, sleeping for nearly over a month with no more than a little bit of time, leaving me with just enough energy so I could use the restroom. I lost my appetite and felt like a ghost of a child, living without quality of life. Eventually, my parents took me off the medication, realizing that ADHD was not my issue.

Looking back, I can trace the earliest signs of my struggles to the start of kindergarten. I remember being a crybaby, feeling overwhelmed while the other kids seemed to navigate the world with ease. It was evident that I was in an extreme emotional state that my peers could not relate to. My teacher noticed and suggested to my parents that I should not return to school until I was ready, recommending that we seek help through medication. This was my first taste of being seen as "different."

The Misunderstanding: Feeling Like The Black Sheep

Growing up, I often felt mistreated and misunderstood. I was labeled as the "problem child," someone who just wanted attention or who couldn’t control their emotions. My cries for help went unheard, and I often found myself shunned to my room. The isolation was stifling. I yearned for life to be easier, wishing that I could find happiness, but no matter how hard I tried, joy seemed elusive.

At the age of nine, I experienced the first signs of my hallucinations while drawing at the dinner table. I began hearing voices—conversations that no one else seemed to hear. I remember looking at my mother and father, realizing that they were oblivious to my experience. I thought I had tapped into some otherworldly frequency, believing I must possess psychic abilities. I never told my parents about these voices, fearing they wouldn’t believe me. I felt trapped in my reality, unable to articulate the turmoil brewing inside me.

A Desperate Act: My Helpful Alarm

At eleven, feeling completely lost and overwhelmed, I attempted to end my life. My parents found me and saved me, but it was a turning point. It marked the moment they began to understand that I wasn’t just a "problem" but someone in need of serious help. The psychiatrist explained that my behavior was beyond my control and that I needed support, leading to my first experience with psychiatric care.

However, being diagnosed at a young age posed a challenge for doctors, who were reluctant to label me due to my developing brain. I was placed on mood stabilizers on and off throughout my teenage years. The rebellious spirit of adolescence made it difficult to adhere to my medication regimen. I would feel great and believe I no longer needed medication, only to crash back down into a cycle of despair.

The Struggles of Adolescence: Navigating Medications At School

My teenage years were fraught with challenges. Finding the right medication was like searching for a needle in a haystack. Some medications increased my symptoms rather than alleviating them, while others made me feel nauseous or lethargic. School became a battleground; I often fell asleep in class, leading to trouble when my parents insisted I go to school, even when I was sick. The medications also had side effects that were difficult to manage, like unexpected bruising and rashes that made me feel self-conscious.

At sixteen, I decided to stop taking my medication entirely. This decision came back to haunt me when, at eighteen, I experienced my first psychotic break. It was a terrifying experience, one that left me feeling utterly helpless and out of control. I lost track of time and reality, not recalling significant portions of what transpired. When I finally emerged from this episode, the support I received from doctors, nurses, my partner at the time & his family, and the fellow patients in the hospital, they helped me piece together the fragments of my experience.

A Turning Point: Committed & Commitment To Recovery

That psychotic break was a wake-up call. It made me realize the importance of medication in stabilizing my mental health. I promised myself that I would never again intentionally go without treatment. I began taking my medications religiously, understanding that they were not just a means to control my symptoms but a lifeline to my well-being.

Now, at 28, I have come to terms with my identity as someone living with schizophrenia. Rather than viewing it solely as a disability, I see it as part of who I am. It has taught me resilience, empathy, and the importance of mental health advocacy. I am more self-aware than ever and actively engage in conversations about mental health, breaking down the stigma that surrounds it.

Conclusion: Embracing My Journey

My journey has been anything but easy, but it is a testament to the strength of the human spirit. I want others who may be struggling to know that they are not alone. Life with schizophrenia is challenging, but it can also be filled with moments of joy, connection, and self-discovery. I share my story to inspire hope and understanding, reminding us all that there is strength in vulnerability and power in sharing our experiences.

My name is Rain, and this is my story of living with schizophrenia. It is not just a story of struggle; it is a story of survival, growth, and the relentless pursuit of a meaningful life. Thank you for reading.

— Rain

#my story#my life#real story#mental health struggles#mental health awareness#schizophrenia advocate#seriously schizophrenic#schizophrenic disorder#schizophrenia awareness#schizophrenic spectrum#paranoid schizophrenic#bipolar schizoaffective#schizoposting#actually schizophrenic#schizoaffective#schizophrenia#real life stories#real life#true story#true self#my journey#embrace the journey#mental health journey#spiritual journey#healing journey#self journey#health and wellness#wellnessjourney#wellness journey#mental wellness

1 note

·

View note

Text

This is for the people who lost opportunities, friends, family, possessions, homes and years because of mental illness. There is still so much that you can have or regain. This isn't the end for you. Better things are ahead. It's still possible for you to be happy and feel whole. Your dreams are still within reach. You aren't broken... you're growing... and I hope someday you'll be satisfied that things didn't pan out ideally for you.

#schizophrenia#psychosis#schizoaffective#bipolar#mental illness#mental health awareness#mental health advocate#positive vibes#positive mental attitude

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

mental illness runs in the black family as a result of incest and im giving sirius bipolar depression and bellatrix minor schizophrenia

#the noble and most ancient house of black#dead gay wizards#marauders#marauders era#the marauders#sirus black#sirius orion black#regulus black#the black family#hp marauders#bellatrix black#bellatrix lestrange#bellatrix with schizophrenia advocate

124 notes

·

View notes

Text

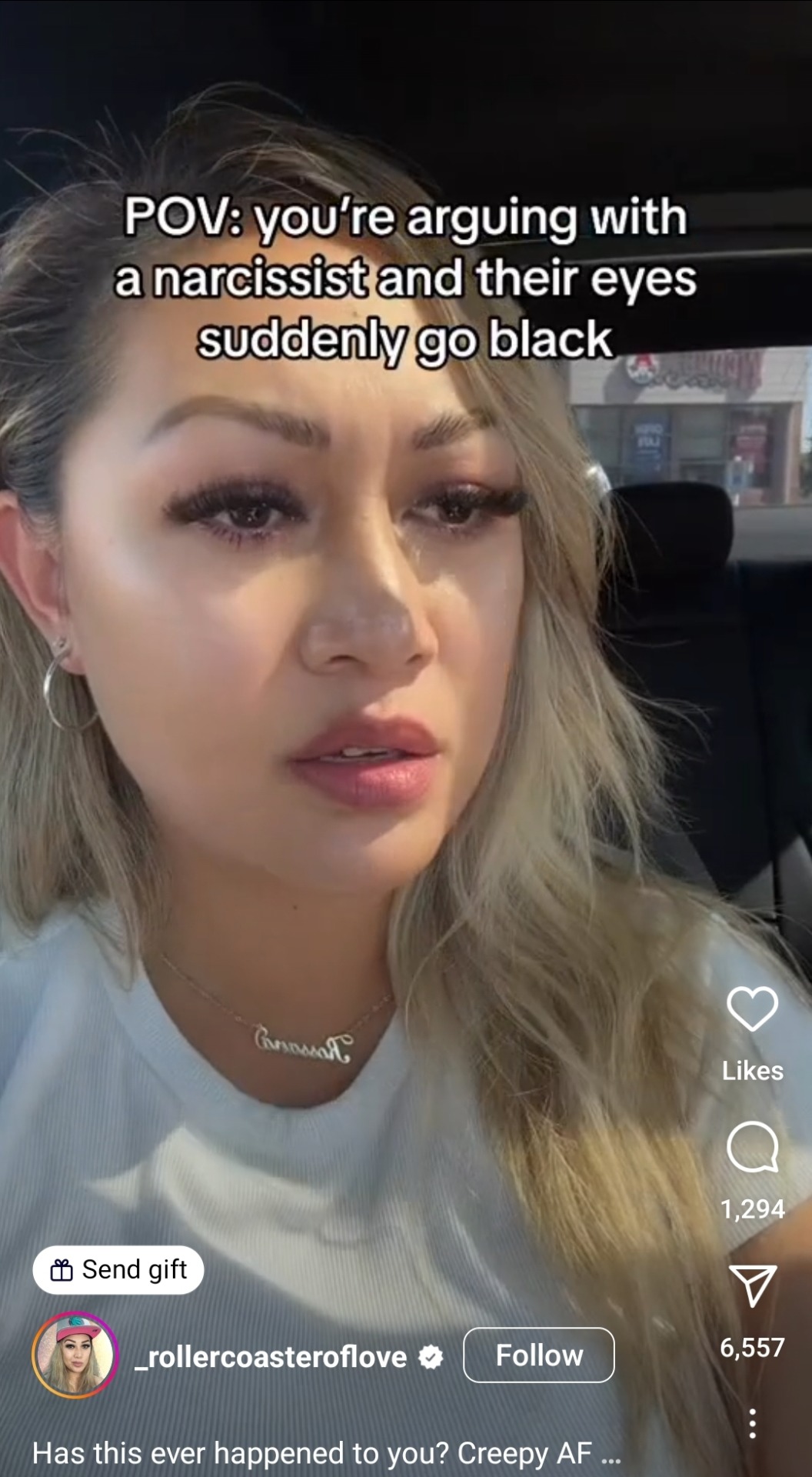

this is fucking crazy to me i mean people w npd arent mythological demons, how the hell does someone's eyes turn black. these shitheads are just ableist, no other explanation. these survivors gather to shit on people who were ALSO traumatized as a child.

if you support every other mental illness except for cluster b disorders, schizophrenia, did, etc. then you are ableist. you're not that mental health advocate you think you are.

not every abuser is a narcissist, psychopath, sociopath, etc. abusers are people who choose to abuse. abuse is something that is done INTENTIONALLY. you can see someone who is hurting.

#npd abuse isnt real#actually npd#npd positivity#npd#narcisstic personality disorder#narcissistic abuse#narcissism#aspd#antisocial personality disorder#did#actually dissociative#dissociation#schizophrenia#ableism#mental health advocate#mental health#schizoid#psychosis#conduct disorder#cptsd#ptsd#dpdr

94 notes

·

View notes

Text

Clozapine: Unlocking Relief for Negative Symptoms in Schizophrenia

🔥 It’s no secret—I’m a huge advocate for clozapine. This life-changing medication remains underutilized in treating serious mental illness, and unfortunately, the consequences of this gap are felt throughout the community. Compared to my colleagues, I prescribe clozapine at a significantly higher rate. Why? Because as clinicians, it’s our responsibility to follow the evidence, champion the most effective treatments, and push the boundaries of what’s possible for our patients.

#psychiatry#mental health#doctor#medical#shrinks in sneakers#mental health matters#mental illness#psychosis#schizophrenia treatment#schizo spectrum#schizoaffective#schizophrenia#clozapine#clozaril#mental health advocate#mental health support#mental health awareness

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

For years I have been fighting and advocating on this small platform for mental illness and fighting to have a way to tell my story that recovery is possible. I have searched my area for years and years with availability. I finally on whim decided to put in a application for a company called nami (national alliance of mental illness) and got an email back. Today I had a meeting and there are finally availabilities and she said she has been looking for people with my specific passion for a while. I happy to say I'm soon going to start training to facilitate classes to people struggling and in the beginning stages of mental illness and give them hope. These are literally the same classes my mom took when I was diagnosed over a decade ago. Life is coming full circle and I'm so emotional right now. I'm hoping and praying this works out and I can finally get my voice out there.

#mental health#mental health advocate#mental illness#bipolar disoerder#borderline personality disorder#anxiety#depression#schizophrenia#schizoaffective#eating disorders

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sorry sorry I was just reading a reply of a post where someone was like the difference between a mental illness and a mental disorder is that one implies a strive to find a cure and I'm just like... babe what world do you live in where people don't want to "fix" you

#yes even so called destigmatized disorders are still seen as something that needs to be solved and eradicated#this was on like a post about how neurodivergent doesnt just mean adhd and autism but also a plethora of other#mental disorders and illnesses that people dont make cute little aesthetic jokes about#but thats just the thing loves you make the jokes and the positivity posts about yourself others still want you to sit calmly and shut up#and that leads into why i have so much resentment over neurotypical bc by using this one umbrella term you are completely erasing#and fucking sanitizing the experiences of other mentally ill people that dont fit your fun quirky image#i didnt want to rant on that post bc i get it i get why people find comfort in the term but the more i think about the more i dislike it#having adhd doesnt give you a pass to leave other mentally ill people behind to not learn and advocate for eachother#to dismiss them of their struggles when they beg you to sympathize with them bc you want stable people to feel comfortable#meant to say neurodivergent there it is too early in the morning im just having a cynical laugh#delete later#it was just such a fucking weird hill to die on even ignoring everything else who are you to say someone with ptsd or anxiety#or schizophrenia cant call themselves whatever the fuck they want

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

My sister said I’m a role model for people with severe mental disorders because I show that there’s a light at the end of the tunnel

#very cool very nice yes#my dad keeps telling me I’m a good person and that I’m going to heaven#personal#if you have schizophrenia and struggle with it daily I love you#bipolar disorder too#she’s a social worker and wants to be an advocate for mental health in our family she just got her doctorate

0 notes

Text

Understanding Bipolar Disorder: Why Persistent Depression May Signal More

Understanding Bipolar Disorder: Why Persistent Depression May Signal More - #bipolar #mentalhealth #depression #anxiety #mentalhealthawareness #ptsd #mentalillness #bpd #mentalhealthmatters #bipolarawareness #bipolardisorder #recovery #love #endthestigma

Depression is a pervasive mental health issue affecting millions worldwide. For some individuals, however, the experience of depression can be persistent and challenging, leading to ongoing struggles with mood regulation. In certain cases, the underlying cause of this relentless depression may not solely be unipolar depression. Instead, bipolar disorder could be a significant contributing factor.…

#adhd#anxiety#bi polar awareness#bi polar disorder#bipolar#bipolar depression#borderline personality disorder#bpd#depression#end the stigma#mental health#mental health advocate#mental health awareness#mental health matters#mental health recovery#mental health support#mental illness#ocd#ptsd#recovery#schizophrenia#selfcare#selflove#therapy#trauma

0 notes

Text

youtube

Living with bipolar schizoaffective disorder is a complex and often challenging experience. It's a condition that combines symptoms of both bipolar disorder and schizophrenia, which can create a unique and difficult journey. Understanding what it feels like to live with this condition requires a deep dive into its emotional, psychological, and social aspects.

The Daily Reality

Each day can be unpredictable. Some moments, I feel elated, bursting with creativity and energy, while others plunge me into deep despair. These mood swings can be intense and significantly affect my daily life. During a manic phase, I might stay up all night, fueled by ideas and plans, feeling invincible and capable of anything. However, this high is often followed by a crash into depression, where even getting out of bed feels like an insurmountable task.

In addition to mood fluctuations, the schizoaffective aspect brings its own set of challenges. I might experience hallucinations or delusions that distort my perception of reality. For example, I may hear voices that aren't there or feel as though I'm being watched. These experiences can be terrifying and isolating, making it hard to connect with others or feel safe in my surroundings.

Coping Mechanisms

To navigate the complexities of living with bipolar schizoaffective disorder, I've developed various coping strategies. Therapy plays a crucial role in my management plan. Having a therapist to talk to helps me process my feelings and experiences, and provides me with tools to handle my symptoms. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) has been particularly effective for me, as it helps challenge and reframe negative thoughts.

Medication is another cornerstone of my treatment. Finding the right combination of medications has been a journey in itself. Some days, I feel like a lab rat, trying different pills and dosages, but when I find something that works, it can make a significant difference. It's important to recognize that medication is not a cure, but rather a way to manage symptoms and provide stability.

Social Interactions and Relationships

Building and maintaining relationships can be difficult. Friends and family often don’t fully understand what I’m experiencing. I’ve had to learn how to communicate my needs and symptoms effectively. There are times when I withdraw from social situations, fearing that my mood swings or hallucinations will alienate those I care about. This isolation can lead to loneliness, reinforcing the cycle of depression.

However, I have also found incredible support from others who understand what it’s like to live with a mental health condition. Joining support groups, both in-person and online, has helped me connect with people who share similar struggles. These connections remind me that I am not alone in my journey.

The Importance of Advocacy

Understanding and raising awareness about bipolar schizoaffective disorder is important for both those who live with it and the general public. Stigma can create barriers to treatment and understanding. By sharing my story, I hope to shed light on the realities of this condition, encouraging empathy and support from others.

Conclusion

Living with bipolar schizoaffective disorder is not just about managing symptoms; it's about navigating a complex emotional landscape. It's a journey filled with ups and downs, requiring strength, resilience, and understanding. By sharing my experiences, I hope to foster a greater understanding of this condition, helping others to see the person behind the diagnosis.

Ultimately, while this journey can be daunting, it is also filled with moments of hope and connection. I strive to take each day as it comes, celebrating the small victories and learning from the challenges. Understanding my condition is a continuous process, and I welcome the journey ahead.

#Youtube#schizophrenia#schizophrenic disorder#bipolar schizoaffective#actually schizophrenic#schizoaffective#schizoposting#schizophrenic spectrum#paranoid schizophrenic#bipolar disorder#true story#personal story#true life#real story#this is my life#spread awareness#schizophrenia awareness#schizophrenia advocate#mental health#mental health advocate#mental health awareness#difficult disability#disability advocacy#invisible illness#invisible disability#invisible disease#not all disabilities are visible#understanding#bipolar schizophrenic#bipolar schizophrenia

1 note

·

View note

Text

They aren't "just" psychiatric wards. Nor are they solely hospitals. They're places where you lose fundamental rights... from using something as simple as a ballpoint pen, as common as mouthwash, a belt, a smartphone, you name it. They're locations where you are isolated from your loved ones. Areas of boredom that make you dive further into your head. Spots where if you fail to comply you'll be sedated, strapped, limited or locked away. But don't get me wrong... people do need psychiatric care. Absolutely. It's just that we need a more compassionate approach to be used more often. One that is more sympathetic, understanding and sensitive to people's specific needs.

All in all there is a lot of advocating to be done still. A massive amount. Psychiatric assistance isn't perfect yet. There is a lot to be improved. So much is still unacceptable.

#schizophrenia#psychosis#psychotic#schizoaffective#mental illness#psychiatry#psych ward#schizophrenic spectrum#mental hospital#mental institution#psychotic break#schizo spectrum#mental health advocate#mental health awareness

518 notes

·

View notes

Text

also in regards to that last article about varied ways of thinking about psychosis/altered states that don't just align with medical model or carceral psychiatry---I always love sharing about Bethel House and their practices of peer support for schizophrenia that are founded on something called tojisha kenkyu, but I don't see it mentioned as often as things like HVN and Soteria House.

ID: [A colorful digital drawing of a group of people having a meeting inside a house while it snows outside.]

"What really set the stage for tōjisha-kenkyū were two social movements started by those with disabilities. In the 1950s, a new disability movement was burgeoning in Japan, but it wasn’t until the 1970s that those with physical disabilities, such as cerebral palsy, began to advocate for themselves more actively as tōjisha. For those in this movement, their disability is visible. They know where their discomfort comes from, why they are discriminated against, and in what ways they need society to change. Their movement had a clear sense of purpose: make society accommodate the needs of people with disabilities. Around the same time, during the 1970s, a second movement was started by those with mental health issues, such as addiction (particularly alcohol misuse) and schizophrenia. Their disabilities are not always visible. People in this second movement may not have always known they had a disability and, even after they identify their problems, they may remain uncertain about the nature of their disability. Unlike those with physical and visible disabilities, this second group of tōjisha were not always sure how to advocate for themselves as members of society. They didn’t know what they wanted and needed from society. This knowing required new kinds of self-knowledge.

As the story goes, tōjisha-kenkyū emerged in the Japanese fishing town of Urakawa in southern Hokkaido in the early 2000s. It began in the 1980s when locals who had been diagnosed with psychiatric disorders created a peer-support group in a run-down church, which was renamed ‘Bethel House’. The establishment of Bethel House (or just Bethel) was also aided by the maverick psychiatrist Toshiaki Kawamura and an innovative social worker named Ikuyoshi Mukaiyachi. From the start, Bethel embodied the experimental spirit that followed the ‘antipsychiatry’ movement in Japan, which proposed ideas for how psychiatry might be done differently, without relying only on diagnostic manuals and experts. But finding new methods was incredibly difficult and, in the early days of Bethel, both staff and members often struggled with a recurring problem: how is it possible to get beyond traditional psychiatric treatments when someone is still being tormented by their disabling symptoms? Tōjisha-kenkyū was born directly out of a desperate search for answers.

In the early 2000s, one of Bethel’s members with schizophrenia was struggling to understand who he was and why he acted the way he did. This struggle had become urgent after he had set his own home on fire in a fit of anger. In the aftermath, he was overwhelmed and desperate. At his wits’ end about how to help, Mukaiyachi asked him if perhaps he wanted to kenkyū (to ‘study’ or ‘research’) himself so he could understand his problems and find a better way to cope with his illness. Apparently, the term ‘kenkyū’ had an immediate appeal, and others at Bethel began to adopt it, too – especially those with serious mental health problems who were constantly urged to think about (and apologise) for who they were and how they behaved. Instead of being passive ‘patients’ who felt they needed to keep their heads down and be ashamed for acting differently, they could now become active ‘researchers’ of their own ailments. Tōjisha-kenkyū allowed these people to deny labels such as ‘victim’, ‘patient’ or ‘minority’, and to reclaim their agency.

Tōjisha-kenkyū is based on a simple idea. Humans have long shared their troubles so that others can empathise and offer wisdom about how to solve problems. Yet the experience of mental illness is often accompanied by an absence of collective sharing and problem-solving. Mental health issues are treated like shameful secrets that must be hidden, remain unspoken, and dealt with in private. This creates confused and lonely people, who can only be ‘saved’ by the top-down knowledge of expert psychiatrists. Tōjisha-kenkyū simply encourages people to ‘study’ their own problems, and to investigate patterns and solutions in the writing and testimonies of fellow tōjisha.

Self-reflection is at the heart of this practice. Tōjisha-kenkyū incorporates various forms of reflection developed in clinical methods, such as social skills training and cognitive behavioural therapy, but the reflections of a tōjisha don’t begin and end at the individual. Instead, self-reflection is always shared, becoming a form of knowledge that can be communally reflected upon and improved. At Bethel House, members found it liberating that they could define themselves as ‘producers’ of a new form of knowledge, just like the doctors and scientists who diagnosed and studied them in hospital wards. The experiential knowledge of Bethel members now forms the basis of an open and shared public domain of collective knowledge about mental health, one distributed through books, newspaper articles, documentaries and social media.

Tōjisha-kenkyū quickly caught on, making Bethel House a site of pilgrimage for those seeking alternatives to traditional psychiatry. Eventually, a café was opened, public lectures and events were held, and even merchandise (including T-shirts depicting members’ hallucinations) was sold to help support the project. Bethel won further fame when their ‘Hallucination and Delusion Grand Prix’ was aired on national television in Japan. At these events, people in Urakawa are invited to listen and laugh alongside Bethel members who share stories of their hallucinations and delusions. Afterwards, the audience votes to decide who should win first prize for the most hilarious or moving account. One previous winner told a story about a failed journey into the mountains to ride a UFO and ‘save the world’ (it failed because other Bethel members convinced him he needed a licence to ride a UFO, which he didn’t have). Another winner told a story about living in a public restroom at a train station for four days to respect the orders of an auditory hallucination. Tōjisha-kenkyū received further interest, in and outside Japan, when the American anthropologist Karen Nakamura wrote A Disability of the Soul: An Ethnography of Schizophrenia and Mental Illness in Contemporary Japan (2013), a detailed and moving account of life at Bethel House. "

-Japan's Radical Alternative to Psychiatric Diagnosis by Satsuki Ayaya and Junko Kitanaka

#personal#psych abolition#mad liberation#psychosis#altered states#antipsych#antipsychiatry#mad pride#peer support#schizophrenia#i have a pdf of the book somewhere if anyone wants#the book and the documentary also discuss some of the pratical struggles in creating a community like this which i also found helpful as#someone who is very interested in helping open a peer respite.

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

If you advocate for mental health awareness, but joke about things like intrusive thoughts and schizophrenia, think it’s disgusting and lazy when people who are depressed can’t do things like showering or cleaning their room, use terms like “narcissistic abuse”, and believe that having ASPD, BPD, or NPD makes someone a bad person, you are not a mental health advocate. You don’t actually care about helping people or de-stigmatizing mental illness, you just want to make yourself feel like you do. You can’t pick and choose what disorders and symptoms are acceptable, and which ones make someone a bad person. Either you support everyone, or you support no one.

and if you’re neurodivergent/mentally ill and you do any of those things, you are part of the problem. there’s no such thing as “good/moral” disorders, or “bad/immoral” disorders. We all need to have each other’s backs.

#mental health#mental illness#tw abelism#npd safe#bpd#npd#aspd safe#aspd#ocd#schizophrenia#cluster b#neurodivergent

7K notes

·

View notes

Note

Do you know much about how antipsych applies to autism?

autism is one of very few psych diagnoses that has a semi organised tradition of actual self advocacy and a communal tendency to reject and criticise the proffered treatments (ABA, various other forms of abuse). autistic advocates have also played huge roles in developing and articulating the neurodivergency paradigm—arguing that autism is not a 'disease' in need of a cure, but simply a way that some people are, as a result of value-neutral variation that all human minds display.

i don't actually love the neurodivergency paradigm because i don't think the 'neurotypical' exists or is a useful benchmark against which to compare oneself; also, many proponents of this framework are explicitly hostile to deconstructing their very monolithic understanding of each psych diagnosis, and they tend to continue viewing these diagnoses as 'real' biological conditions that simply need to be destigmatised. i don't think this destigmatisation is truly possible as long as we still believe that autism or anything else truly is a distinct, identifiable 'brain difference', even if we're construing it as a neutral variation instead of a pathology. these categories are made up; what unites two people with autism is not necessarily anything to do with their brains, it's a function of (and disgnosed by) external behaviours and the failure to perform social normality. every single person varies biologically (again, there is no 'neurotypical') and varies as much within psychiatrically delineated categories as much as across them.

but anyway i digress: autism is probably the psych diagnosis with the single most organised critique of psychiatry right now. there are of course self advocacy groups for other diagnoses but i haven't really seen any break through with their critique the way that like ASAN have for example. historically i think one thing that has made autism friendly ground for this is that it's the rare psych dx that isn't legal gatekeeping for a drug (compare autistic self advocacy to adhd 'self' 'advocacy' for example) and another huge factor is that autism in its present form is historically differentiated from achizophrenia by being the less stigmatised, more benign 'version' with schizophrenia explicitly reserved for more vulnerable and marginalised populations (eg in the US, black political radicals). so it's not terribly surprising that some of those diagnosed autistic then push this logic even further and say, hey, there's nothing actually Wrong with us though—and it's especially not surprising that the institutional and public response to this has been, while hardly universally positive, generally much more amenable than to people with 'scarier' and racialised diagnoses who say the same thing about themselves. non-radicality of mainstream autistic advocacy aside, even.

729 notes

·

View notes

Text

In that vein... (No, the following is not about autism or ADHD)

TL;DR: Using medical terms as insults or otherwise misusing medical terms (even as a joke) leads to uninformed people thinking they have to stop saying these words and creating new words. Either because they think the old term isn't precise enough anymore or because they incorrectly think that we're insulted by the old word.

The constant appearance of new words is confusing to people who struggle to learn new words. It excludes them from participating in discussions about their own condition.

We have to be more sensitive regarding possible repercussions and stop unnecessary discourse by uninformed people.

In Germany, the official word for my disability ID card category and the assessment is "Hirnschädigung", which literally translates to brain damage/damaged brain. And that's a neutral description, nothing outdated.

But many many people have been asking if someone has brain damage whenever they wanted to insult someone who is either slow on the uptake or who just made a very strange or silly suggestion, for example. They used it as an insult all the time, sometimes jokingly, sometimes not.

This is why now a lot of people ask "Uh, can we still say that in the 21st century? Shouldn't we change "brain damage" to something nicer? Isn't that word insulting?" when actually no, it isn't. (Of course you still shouldn't use that term if someone directly tells you they don't want to be called that)

It's the same with "disabled". People used and still use "disabled" and "dumb" synonymously in Germany. So now, well-meaning politicians and even advocates create all kinds of euphemisms because they think that disabled people will be offended by the word "disabled". Because some people use it as an insult.

When I say I'm disabled in German ("behindert"), people flinch. They think I just insulted myself. But no, "behindert" is a normal medical word, it's in the name of our disability ID card. Even more, the literal translation is "severely disabled person's pass", there's a "severe" accompanying the word "disabled". They flinch even more when I say I'm severely disabled.

"Disorder" has a negative connotation because it's been used as an insult. "Disabled" has a negative connotation because it's been used as an insult. People mixed up schizophrenia and DID and now many think that "feeling schizophrenic" is a sophisticated way to say that you feel conflicted.

The pattern is always the same: People use normal medical words either as insults or in an unrelated, non-medical way, and as a result well-meaning but uninformed advocates create "nicer" sounding words because they think the original word is either outdated or offensive. Or they think "Now that everyone misuses it, we need a new word for the medical term so that there are no misunderstandings."

In both cases, "our" words were successfully co-opted and we have to learn 10 new words to know that people talk about our conditions.

Unfortunately, not everyone sees 10 new words for their condition and intuitively picks up the meaning and knows what everyone's talking about. Sometimes words are hard. Sometimes it's hard to learn all these words and then be told by some uninformed activist that we shouldn't call ourselves what we've always called ourselves.

And what kind of people sometimes struggle with learning new words? People with cognitive impairments. People with brain damage. People who had a stroke. People who survived a ruptured aneurysm.

If you hear "Please stop saying you have a stroke or an aneurysm", etc., did it ever occur to you that maybe it's not because we're offended, but because we don't want these words to get negative connotations? Whenever something gets a negative connotation, there's a possibility for it to be seen as a slur and that would lead to 10 new words to learn because uninformed activists think the original term is offensive or not precise enough.

When I say "Hey, please stop saying you have a stroke when you don't understand something", I'm not offended and I'm not saying it's ableist. I've just noticed enough patterns to be quite sure that at some point there'll be an uninformed well-meaning advocate who suggests a new word for stroke survivors because they think the old word isn't precise enough anymore.

And I don't know if there are enough stroke survivors on social media who could stop this new word and mindset from reaching other uninformed advocate spaces...

330 notes

·

View notes

Text

Schizophrenia, DID and delusion jokes became popular because it became less socially acceptable to joke about ocd, autism etc. and people still wanted to be ableist. I see you making jokes about being delusional and thinking people with actual delusions need to be locked away. I see you making schizo jokes. you would say the r slur if you could get away with it.

It's easy to pick on the most misunderstood mental illnesses because you know the people you are hurting are way less that the people who don't care.

you don't get to pick and choose which mental illness to respect. And if you ever try to advocate for disabled or neurodivergent people rights I know your words are actually empty and performative.

Sorry if tagging your post as unreality ruins the joke. It must be so hard to live in a world where there are such insane people that can't tell reality apart. They should just get locked away from your eyes, right? I hope you don't ever put trigger warnings just to stay coherent, unless you think there's a certain level a neurodivergent person can be weird until it's acceptable. Well, they can't be too ridiculous right? they should be a little normal at least. They don't reserve respect because something that's out of their control is too far right? Respect is only given if you don't have to think too hard or do a little work right?

I see you.

273 notes

·

View notes