#partisans of liberty

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

“Fantasy is escapist, and that is its glory. If a soldier is imprisoned by the enemy, don't we consider it his duty to escape? . . .If we value the freedom of mind and soul, if we're partisans of liberty, then it's our plain duty to escape, and to take as many people with us as we can!” | J.R.R. Tolkien |

#brownsugar4hersoul#soul candy#sugar for the soul#eye candy#ear candy#brown sugar#spilled ink#j.r.r. tolkien#self care reminder#life advice#deep quotes#note to self#fantasy#escapist#glory#escape#imprisonment#value#freedom#mind#soul#partisans of liberty#our duty#reminder#self reminder#friendly reminder#gentle reminder#reminders#good advice#advice

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

I will add to this, you can check out:

-Blue Voter Guide, for Democratic voters.

-State government sites may have information on candidates - for example my state of Colorado gave performance ratings of judicial candidates.

-State Bar Associations may also have information on judicial candidates

And of course, you can try local news, but be wary of bias (as with all sources).

Please don't tune out when you get to the non-partisan section of your ballot this November. First off, where state Supreme Court justices are elected, Republicans are trying their darndest to elect candidates who will destroy reproductive freedom, gut voting rights, and do everything in their power to give "contested" elections to Republicans. Contrast Wisconsin electing a justice in 2023 who helped rule two partisan gerrymanders unconstitutional, versus North Carolina electing a conservative majority in 2022, who upheld a racist voter ID law and a partisan gerrymander that liberal justices had previously struck down both of.

Second, local judicial offices will make infinitely more of an impact on your community than a divided state or federal legislature will. District and circuit courts, especially, are where criminalization of homelessness and poverty play out, and where electing a progressive judge with a commitment to criminal justice reform can make an immediate difference in people's lives.

It's a premier example of buying people time, and doing profound-short-term good, while we work to eventually change the system. You might not think there will be any such progressive justices running in your district, but you won't know unless you do your research. (More on "research" in a moment.)

The candidates you elect to your non-partisan city council will determine whether those laws criminalizing homelessness get passed, how many blank checks the police get to surveil and oppress, and whether lifesaving harm reduction programs, like needle exchanges and even fentanyl test strips, are legal in your municipality. Your non-partisan school board might need your vote to fend off Moms for Liberty candidates and their ilk, who want to ban every book with a queer person or acknowledgement of racism in it.

Of course, this begs the question — if these candidates are non-partisan, and often hyper-local, then how do I research them? There's so much less information and press about them, so how do I make an informed decision?

I'm not an expert, myself. But I do think/hope I have enough tips to consist of a useful conclusion to this post:

Plan ahead. If you vote in person, figure out what's on your ballot before you show up and get jumpscared by names you don't know. Find out what's on your ballot beforehand, and bring notes with you when you vote. Your city website should have a sample ballot, and if they drop the ball, go to Ballotpedia.

Ballotpedia in general, speaking of which. Candidates often answer Ballotpedia's interviews, and if you're lucky, you'll also get all the dirt on who's donating to their campaign.

Check endorsements. Usually candidates are very vocal about these on their websites. If local/state progressive leaders and a couple unions (not counting police unions lol) are endorsing a candidate, then that's not the end of my personal research process per se, but it usually speeds things up.

Check the back of the ballot. That's where non-partisan races usually bleed over to. This is the other reason why notes are helpful, because they can confirm you're not missing anything.

#US#Politics#Election#2024#Ballots#Research#Election Information#Candidates#Non-Partisan Candidates#Judicial Elections#Local Elections#Civil Rights#Housing#Criminal Justice Reform#Police Reform#Harm Reduction#Education#School Boards#Censorship#Queer Rights#Moms For Liberty#Ballotpedia#Blue Voter Guide#League of Women Voters#Bar Associations#State Government#Vote#Vote Early#Vote Blue

7K notes

·

View notes

Text

Mal Partisan: O.A.R.: Liberalism, the Philosophy of Individual Rights & Freedom

Source:The New Democrat I’m a Liberal and when I hear the term ‘Modern Liberal’ today it makes me a little angry. Because today’s so-called ‘Modern Liberals’ would be called Socialists in any other country. Because they have a collectivist view of society and believe that government should always be looking out for the society as a whole, even protecting people from themselves. Both an economic…

View On WordPress

#America#Center Right#Classical Liberalism#Classical Liberals#Constitutional Rights#Freedom#Individual Freedom#Individual Rights#Individualism#Individualists#Liberal Constitution#Liberal Democracy#Liberalism#Liberals#Liberty#Mal Partisan#United States#United States Constitution

0 notes

Text

Some Americans seem unable to accept how much peril they face should Trump return, perhaps because many of them have never lived in an autocracy. They may yet get their chance: The former president is campaigning on an authoritarian platform. He has claimed that “massive” electoral fraud—defined as the vote in any election he loses—“allows for the termination of all rules, regulations, and articles, even those found in the Constitution.” He refers to other American citizens as “vermin” and “human scum,” and to journalists as “enemies of the people.” He has described freedom of the press as “frankly disgusting.” He routinely attacks the American legal system, especially when it tries to hold him accountable for his actions. He has said that he will govern as a dictator—but only for a day.

Trump is the man the Founders feared might arise from a mire of populism and ignorance, a selfish demagogue who would stop at nothing to gain and keep power. Washington foresaw the threat to American democracy from someone like Trump: In his farewell address, he worried that “sooner or later the chief of some prevailing faction” would manipulate the public’s emotions and their partisan loyalties “to the purposes of his own elevation, on the ruins of public liberty.”

Many Americans in 2016 ignored this warning, and Trump engaged in the greatest betrayal of Washington’s legacy in American history. If given the opportunity, he would betray that legacy again—and the damage to the republic may this time be irreparable.

The Moment of Truth

218 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Shadows of History: Parallels and Warnings in American Democracy

As a historian, I am acutely aware that while history does not repeat itself, it often presents echoes that serve as warnings for the future. The United States today stands at a crossroads, with certain elements reminiscent of 1930s Nazi Germany and the ambitious plans of Project 2025, raising concerns about the direction in which the country is heading.

The 1930s in Germany were marked by the rise of authoritarianism, a period where democratic institutions were systematically dismantled in favor of a totalitarian regime. The parallels drawn between that era and the current political climate in the United States are not to suggest an identical repetition of events, but rather to highlight concerning trends that, if left unchecked, could undermine the very foundations of American democracy.

**Project 2025 and the Unitary Executive Theory**

Project 2025, a conservative initiative developed by the Heritage Foundation, aims to reshape the U.S. federal government to support the agenda of the Republican Party, should they win the 2024 presidential election. Critics have characterized it as an authoritarian plan that could transform the United States into an autocracy. The project envisions widespread changes across the government, particularly in economic and social policies, and the role of federal agencies.

This initiative bears a resemblance to the early strategies employed by the Nazi Party, which sought to consolidate power and align all aspects of government with their ideology. The unitary executive theory, which asserts absolute presidential control over the executive branch, is a central tenet of Project 2025. This theory echoes the power consolidation that occurred under Hitler's regime, where legal authority was centralized to bypass democratic processes.

**The Erosion of Democratic Norms**

In both historical and contemporary contexts, the erosion of democratic norms is a precursor to the loss of liberty. The United States has witnessed a polarization of politics, where partisan interests often override the common good. The Supreme Court, once a non-partisan arbiter of the Constitution, has been accused of partisanship, with decisions increasingly influenced by political ideologies rather than constitutional law. This shift mirrors the way the judiciary in Nazi Germany became a tool for enforcing the will of the regime, rather than a protector of the constitution.

**The Role of Propaganda and Media**

Propaganda played a crucial role in Nazi Germany, shaping public opinion and suppressing dissent. Today, the media landscape in the United States is deeply divided, with outlets often serving as echo chambers that reinforce ideological beliefs. This division hampers the ability of citizens to engage in informed discourse and make decisions based on factual information, a cornerstone of a functioning democracy.

**Civil Liberties and Minority Rights**

The targeting of minority groups was a hallmark of Nazi policy, justified by a narrative of nationalism and racial purity. In the United States, there has been a rise in xenophobia and policies that discriminate against certain groups. The protection of civil liberties and minority rights is essential to prevent the kind of societal divisions that can lead to the marginalization of entire communities.

**Conclusion**

The parallels between the United States today, Project 2025, and 1930s Nazi Germany serve as a stark reminder of the fragility of democracy. It is imperative that as Americans, we remain vigilant against the forces that seek to undermine democratic institutions and principles. The lessons of history implore us to safeguard the values of liberty, equality, and justice, lest we allow the shadows of the past to shape our future.

As a historian and educator, I believe it is our responsibility to draw upon these parallels not to incite fear, but to inspire action. We must engage in civic education, promote critical thinking, and encourage participation in the democratic process. Only through collective effort can we ensure that the American experiment continues to be a beacon of hope and freedom for the world.

126 notes

·

View notes

Text

The framing of public-sector workers and unions as parasites rests on a longstanding discursive distinction between society’s “makers and takers,” to borrow a phrase made popular by Mitt Romney’s 2012 presidential campaign. Its success depends on the premise that populist politics—and the producerist ideology at its heart—flows from identifiable grievances by those who produce society’s wealth against those who consume it without giving back. This “producer ethic,” as Alexander Saxton calls it, has roots in the Jeffersonian belief that the yeoman farmer, as neither a master nor a slave, was the proper subject of civic virtue, republican liberty, and self-rule. But it first emerged as a broad partisan identity in the antebellum era, where it expressed in the Democratic Party an opposition between white labor and those who would exploit it. Producerist ideology posited not an opposition between workers and owners but a masculine, cross-class assemblage connecting factions of the elite with poor whites both in cities and on the frontier in what Senator Thomas Hart Benton, a Democrat from Missouri, called “the productive and burthen-bearing classes” in opposition to those cast as unproductive and threatening, including bankers and speculators, slaves, and indigenous people. As such, producerism provided a template for subsequent political intersections of whiteness, masculinity, and labor that would include different groups and target different foes, but always secured by a logic that described a fundamental division in society between those who create society through their efforts and those who are parasitic on, or destructive of, those efforts.

[...] The deep logic of producerism thus structures representations of its negation, the parasite, which since the 1960s in particular has been constructed in highly racialized and gendered terms—the mother on welfare, an immigrant draining public coffers, the criminal “coddled” by liberal judges, or the undeserving recipient of affirmative action. These scripts animate the attack on public-sector unions and workers, continually contrasting its version of the producer—in this case the taxpayer and private-sector worker—with public unions and workers. As we demonstrate, these workers are depicted as unproductive, wasteful, excessive, and indolent, indulging the envied pleasures of shorter working hours, long vacations, and early retirement. They are cognizable precisely because they invoke a longer genealogy of the discourse of racial parasitism and producerism, and its representation of fiscal burdens. Framed this way, unionized public-sector workers become threats to taxpayers—not merely economically, but socially and psychologically as well.

Key to the successful development of populist antistatism has been its selective racial deployment, avoiding discussion of forms of state authority and distribution that have been enjoyed by most of the white electorate since the New Deal, such as Social Security, Medicare, and government-secured home loans. Attacks on the state from the right were aimed originally at school desegregation after the Brown v. Board of Education decisions, and later at busing, fair housing, antidiscrimination law, and affirmative action, and at response programs seen to favor poor people of color, such as AFDC and Medicaid. Conservatives extended this strategy by targeting other figures of racial vulnerability, such as immigrant children in public schools.

At each stage of the development of antistatism, a racialized line separating the deserving from the undeserving was drawn to bolster its claims. Now, the logic of antistatism has become so pervasive, and its success against everything from busing to affirmative action to welfare so thorough, that advocates have begun to turn its logic against new targets. Political elements made vulnerable in class terms can now be attacked via racial logic. The line between the deserving and undeserving has been moved such that a large number of white workers now fall on the latter side of the line as “takers.”

This transformation is rooted in a generation of neoliberal economic restructuring, as cuts in income transfer payments and reductions in property, income, and capital gains taxes shifted more of the responsibility for funding public services from corporations and the wealthy onto middle- and low-income workers. Households faced with flattening wages and rising levels of debt increasingly came to demand tax relief of their own as a way to safeguard their income, giving rise to a populist tax revolt. In this context, the public sector itself became stigmatized as a drain on the budgets of ordinary workers rather than as a keystone of social equity and income security and mobility.

“Parasites of Government”: Racial Antistatism and Representations of Public Employees amid the Great Recession by Hosang and Lowndes (2016)

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

Daniel Villarreal at LGBTQ Nation:

The president has signed an executive order targeting the law firm Jenner and Block because it is involved in a court case challenging his executive order banning gender-affirming care for transgender youth. The law firm denounced the order, but it’s just the latest example of the president persecuting legal firms that oppose his illegal actions. “Jenner engages in obvious partisan representations to achieve political ends [and] supports attacks against women and children based on a refusal to accept the biological reality of [gender],” the president wrote in his order, which he signed Tuesday. He also criticized the law firm for opposing the administration’s attempts to conduct mass extra-judicial deportations of immigrants, for trying to hire a diverse workforce, and for working with special prosecutor Robert Mueller in his investigation into Russia’s support of the president’s 2016 election campaign. Jenner and Block are working on behalf of the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) to block the president’s ban on gender-affirming care. The ban prohibits the federal government from funding, promoting, or supporting gender-affirming care for people under age 19 in any way. This included cutting-off funds — pre-approved by Congress — for any medical schools or institutions that research, provide, or teach about gender-affirming care. [...] The order targeting Jenner and Block directs government agencies to revoke any security clearances held by the firm’s attorneys and to end all federal material support to the firm. It also requires all government contractors to alert the administration if they plan on working with the law firm, and directs the Director of the Office of Management and Budget to provide a list of all entities that do business with the firm.

Lawless tyrant Trump targets yet another law firm…this time, Jenner and Block is under such needless scrutiny, because it is involved in a case against his gender-affirming care EO and also retaliation for their role in the Mueller Special Counsel Investigation.

See Also:

Daily Kos: Trump punishes law firm that hired lawyer who investigated him

The Advocate: Trump executive order targets law firm challenging anti-trans policies

#Donald Trump#Law Firms#Jenner and Block#Andrew Weissman#Executive Orders#Trump Russia Scandal#Mueller Special Counsel Investigation#Gender Affirming Healthcare

26 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Fantasy is escapist, and that is its glory. If a soldier is imprisoned by the enemy, don’t we consider it his duty to escape? ... If we value the freedom of mind and soul, if we’re partisans of liberty, then it’s our plain duty to escape, and to take as many people with us as we can!

Ursula K. Le Guin

#writing#writers#write#writing tips#writing quotes#writing advice#amwriting#writing life#writeblr#quote#quotes

610 notes

·

View notes

Text

You stood beneath a stolen flag,

a coward’s grin behind your mask,

breaking glass like you broke your oath,

spilling blood, spilling truth, spilling both.

The Capitol stood like a sentinel of time,

until you tore it down, crime by fucking crime.

The floors ran red where history walked,

and democracy bled as your chants mocked.

You came as a mob, a tide of rage,

hands on riot shields, fists on the stage.

Tear gas kissed the marble halls,

while “patriots” desecrated sacred walls.

Tarrio, you fucking coward,

Rhodes, you spineless son of a bitch.

Barnett, who pissed on freedom

while democracy screamed in the ditch.

QAnon prophets in horned disguise,

Nazis and “militia” with vacant eyes.

You called it liberty, called it war,

but all you left were shattered doors.

Then the ink of the pen, the coward’s decree,

fifteen hundred pardons for your fucking heresy.

Trump stood tall on lies today,

“Unify!” he cried, while justice decayed.

The audacity of that son of a bitch,

to pardon the mob and their seditious itch.

“Merit-based justice,” he dared to say—

yet he handed treason a golden bouquet.

He spat in the face of every cop who stood,

every drop of blood spilled in those halls of wood.

He pardoned the wreckers, the rioters, the damned,

and gave democracy its final backhand.

Where were you, McConnell, when the blood dried?

Where were you, Thune, when democracy cried?

Greene, you cheered; your voice rang clear—

you gutless motherfuckers, complicit in fear.

Your silence, your nods, your partisan games,

have carved your legacy into the flames.

You are the ghosts of this dying nation,

mute accomplices to its damnation.

And to you who stayed silent, stayed home that day,

clutching your morals as the country frayed,

spare me your protests, your outrage, your blame—

this fire’s on you; you stoked the flame.

You fucking stood back, let them torch the house,

and now you want to cry about the ashes.

Don’t you dare whisper a single goddamn word—

you let others fight while the country burned.

The tear of glass, the battering ram,

the fists that struck, the shields that slammed.

The cries of fear, the clash of will,

the officers falling, the chambers still.

They stormed the gates with malice bright,

and made a coup of that January night.

Freedom fell with every cheer,

the sound of treason in the atmosphere.

And for those who fell defending the line,

we carry their memory through space and time.

But let me tell you something, loud and true:

You may pardon the guilty, but we’re coming for you.

Two years from now, we’ll clear the House;

we’ll take your seats and call you out.

We’ll vote, we’ll march, we’ll raise our fists,

we’ll break the chain of your accomplice list.

And four years from now, your reign will end,

this nightmare gone, this wound will mend.

You’ve made a coup the morning’s norm,

treason an acceptable form,

but you don’t get the final say—

we’ll take this country back one day.

Traitors, cowards, you hollowed the flag,

turned stars to scars, left stripes to sag.

You spat on the graves of those who fought,

and shredded the ideals they thought were taught.

Your pardons are nothing, your names will fade,

while the strength of the people sharpens its blade.

This isn’t your country—it never was.

It belongs to the dreamers, to the cause.

So hear this now, from sea to sea:

We are America, the land of the free.

You tore it down, but we’ll rebuild—

your names forgotten, your dreams killed.

This is the anthem of those betrayed,

a promise to history: you won’t evade.

For every flag, for every vote,

for every tear in the words we wrote.

True patriots rise, unbroken, free—

the soul of this nation will always be.

We are coming.

We are rising.

We are America.

#trump#donald trump#trump 2024#january 6#fuck qanon#proud boys#congress#maga#supreme court#politics and government#democrats#democracy#republicans#trump administration#mike johnson#american politics#jd vance#gop#liberals#joe biden#progressives#democratic party#americans#usa#united states#united states of america#poems and poetry#poetry#poem#poets on tumblr

25 notes

·

View notes

Photo

US Presidential Election of 1796

The US presidential election of 1796 was the first contested presidential election in the history of the United States. John Adams, the candidate of the Federalist Party, won the presidency, defeating his rival, Thomas Jefferson, candidate of the Democratic-Republican Party. Since Jefferson won the second most votes, he became Vice President, as was the protocol at the time.

In the previous two national elections – the US presidential election of 1789 and 1792 – George Washington had been unanimously voted into office, and the presidency had never seriously been contested. Now, with Washington declining to serve a third term, each political party scrambled to secure support for its candidate. Adams, as the incumbent vice president, was widely viewed as Washington's natural successor, but his association with the haughty, nationalist Federalists led to accusations that he was a pro-British monarchist. Jefferson, likewise, was attacked for his party's support of the bloody French Revolution, and his hypocritical opinions on slavery were brought into question. The use of partisan newspapers to attack the candidates became prevalent in this election, reflecting the increase of factionalism in US politics.

At the time, presidential elections were conducted very differently than they are today. Candidates did not run on a shared ticket; instead, each member of the Electoral College cast two votes for whichever candidates they pleased. The candidate who got the most votes was elected president, while the candidate with the second most votes became vice president, regardless of political party. It was for this reason that Adams ended up winning the presidency with Jefferson as his vice president, even though they had been rivals in the election. The partisanship that fueled this election would only worsen four years later, when Adams and Jefferson rematched in the US presidential election of 1800.

Background: Washington's Farewell Address

It was less than two months before the election, on 19 September 1796, when President Washington's famous Farewell Address appeared in the Philadelphia newspaper American Daily Advisor, confirming that he would not seek a third term in office. In the address, Washington revealed that he had initially planned on retiring after his first four years in office but had decided to serve a second term because of heightening tensions with Great Britain. Now, with that crisis averted, Washington saw no reason to stick around and was happy to hand the torch off to a successor. He then went on to emphasize the importance of the Union, which bound all Americans together and protected their liberties, before warning against three existential dangers that threatened to destroy that Union: regionalism, partisanship, and foreign entanglements. On the issue of political partisanship – or 'factionalism' as it was then known – Washington warned that it would lead to a 'spirit of revenge' and would open the door to 'foreign influence and corruption'. He went on to say:

serve to organize faction, to give it an artificial and extraordinary force; to put, in the place of the delegated will of the nation the will of the party, often a small but artful and enterprising minority of the community…they are likely, in the course of time and things, to become potent engines, by which the cunning, ambitious, and unprincipled men will be enabled to subvert the power of the people and to usurp for themselves the reins of government, destroying afterward the very engines which have lifted them to unjust dominion.

(constitutioncenter.org)

George Washington

Gilbert Stuart (Public Domain)

Continue reading...

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Fantasy is escapist, and that is its glory. If a soldier is imprisoned by the enemy, don't we consider it his duty to escape?. . .If we value the freedom of mind and soul, if we're partisans of liberty, then it's our plain duty to escape, and to take as many people with us as we can!”

― J.R.R. Tolkien

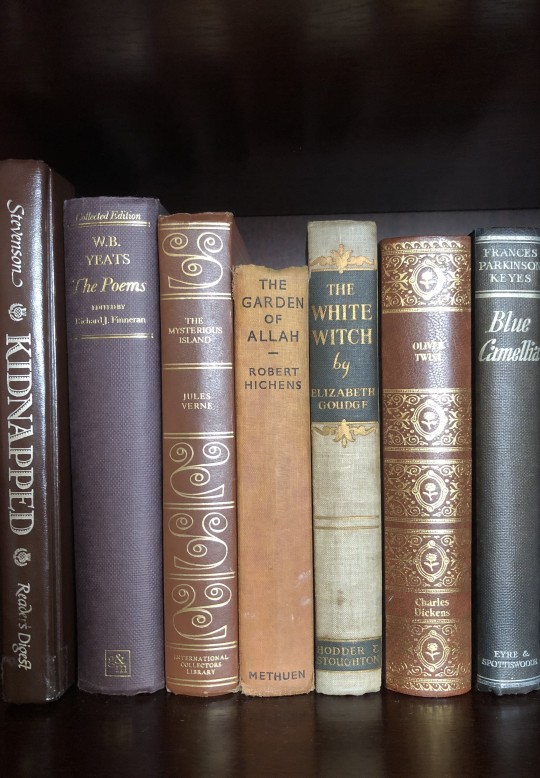

#light academia#j r r tolkien#lotr#nejj bookblr#books#book quotes#quotes#bookworm#bookish#book blog#bookblr#booklr#classic academia#dark academia#romantic academia#literature#english literature#photography#fiction#reading

78 notes

·

View notes

Text

“The oldest argument against SF is both the shallowest and the profoundest: the assertion that SF, like all fantasy, is escapist.

This statement is shallow when made by the shallow. When an insurance broker tells you that SF doesn’t deal with the Real World, when a chemistry freshman informs you that Science has disproved Myth, when a censor suppresses a book because it doesn’t fit an ideological canon and so forth, that’s not criticism; it’s bigotry. If it’s worth answering, the best answer was given by Tolkien, author, critic, and scholar. Yes, he said, fantasy is escapist, and that is its glory. If a soldier is imprisoned by the enemy, don’t we consider it his duty to escape? The moneylenders, the know-nothings, the authoritarians have us all in prison; if we value the freedom of the mind and soul, if we’re partisans of liberty, then it’s our plain duty to escape, and to take as many people with us as we can.”

― Ursula K. Le Guin, The Language of the Night: Essays on Fantasy and Science Fiction

#quote#Ursula K. Le Guin#The Language of the Night: Essays on Fantasy and Science Fiction#The Language of the Night#science fiction#fantasy#reading#writing#from the writer's desk#current reading#current reading quotes#not out of void but out of chaos

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

my reading group finally finished The Black Jacobins by CLR James. It's a really excellent book — James is a great writer, moving deftly between social analyses and individual narratives with literary flair. It definitely leans towards the individual narrative, drawing heavily on personal correspondence as source material and focusing specifically on Toussaint Louverture; but James's guiding light is that "men make their own history, but they do not make it as they please". He's careful to contextualize all the individual actions of the powerful with the relevant material conditions and the will of the masses (in both France and Saint-Domingue).

James said in the 60s that if he'd written it at that time he'd have focused more on the masses and less on the top few individuals, but that would have been quite a different book. As is, it's a well-told narrative of an extraordinary individual who rose to extraordinary circumstances, and how the nature of that rise led almost inevitably to his tragic downfall. James is unabashedly and rightly partisan — a pose of neutrality would be impossibly grotesque when recounting these events — without letting this cloud his judgement of the flaws of Toussaint and others.

The key points, to me, were that Toussaint's successes came from his uncompromising principles in defense of freedom and his correct suspicion of all the imperial powers offering deals and promises they planned to betray as soon as they got the chance, which won him the support of the masses; and his failures came when he began to take the support of the masses for granted, and when he trusted too deeply in the ideals of the French Revolution. Some of the habits which had made him such an effective military leader, like keeping everyone unsure of what he was doing and why, proved harmful once he had to rule. He was forced by economic circumstances to compromise on agriculture and made the terrible mistake of violently suppressing laborers who revolted for better working conditions. Trying to keep up appearances with France and avoid outright war, he confused the masses and his own generals in ways that completely hamstrung their initial response to Napoleon's armies.

Toussaint was arrested and killed by neglect in prison in France; the figure for the moment was Dessalines, portrayed by James as a rather one-sided talent with a penchant for brutality but, crucially, an excellent military leader who hated those he needed to hate. He could promise to his soldiers that any surrender he made was a lie, he could tell a vastly larger army that he'd blow his entire fortress up rather than let a single Frenchman step inside and have his men cheer, he could fight the war he was faced with — which made him the final guarantor of Haitian life and liberty against Napoleon's slavers and genocidaires, whose plan was to wipe out the entire black population and import new slaves from Africa.

(As for the much-vaunted post-independence massacres, James cites a contemporary source who says a key deciding factor was British agents claiming they'd only trade with Haiti if they killed all the French. Had they not, he argues, Christophe and Clairveaux would have checked Dessalines, and Haiti would have been much the better for it. And — though he doesn't bring this up in that moment — he makes it clear throughout the book that the brutality of the white French towards the black population exceeded all their vengeances.)

It's sprinkled throughout with commentary on the world situation of 1938, which is fascinating. The final chapter ends with an especially striking prediction of revolution and decolonization in Africa — of which James is clearly, in the 1963 additions, very proud. It includes the painfully optimistic sentence "International socialism will need the products of a free Africa far more than the French bourgeoisie needed slavery and the slave-trade."

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Choosing to focus on some positive things to keep from despair. Context: living in suburbia in a red state that just had every single race on the ticket go red, local and national.

My non-partisan school board election resulted in the progressive candidates I campaigned for being elected! They won by a wide margin over the candidates who were affiliated with moms for liberty and other ultra right wing groups. This means our schools will (to the extent permitted by shitty state law) continue to have a diversity of books in the library, continue to emphasize diversity and inclusion, and continue to provide social emotional learning. This is a huge win for me personally since I have two kids in middle school.

I saw more yard signs for democrats in my community than I have in any other election in the past.

Now I know that at least two neighbors on my street alone hold similar values to me, instead of having to think we're all alone.

My suburb is full of rich people, and if it's moving to the left over time, then so is the money.

Abortion rights measures won in 7/10 states where they were on the ballot, and had a majority of votes in Florida though not enough to meet their 60% cutoff. Our shitty-ass state laws mean that we can't vote on it here, but the tide of public opinion is clear.

#lita talks about herself#us politics cw#this is probably the last i will say on the matter of the election#to maintain my sanity and ability to get through my work day

14 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hiii!

📝 🏢 🎙 for the ask game :3

Hey!! Thanks for the ask!

Favourite quote: Fantasy is escapist, and that is its glory. If a soldier is imprisioned by the enemy, don't we consider it his duty to escape?. . .If we value the freedom of mind and soul, if we're partisans of liberty, then it's our plain duty to escape, and to take as many people with us as we can!

This is often attributed to JRRT, but they aren't his exact words; more like paraphrasing for what he said in his 1939 essay On Fairy Stories (published 1947).

Dream job: I don't work yet, but my dream job is being an archaeologist. I've always had an interest for it. In fact, I'm currently studying to be one.

Can I sing? Yes, and I've taken classes all through my childhood, and am still continuing learning Carnatic music. It was a requirement for my mother that her children learn music, and luckily I do enjoy it.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fantasy is escapist, and that is its glory. If a soldier is imprisioned by the enemy, don't we consider it his duty to escape?. . .If we value the freedom of mind and soul, if we're partisans of liberty, then it's our plain duty to escape, and to take as many people with us as we can!

J.R.R. Tolkien

21 notes

·

View notes