#Marxist history

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

“He [Napoleon] remained deeply attached to the refusal of the Ancien Régime, to the refusal of national degradation in the face of the Bourbons and aristocratic Europe. It is from this refusal that he will draw the strength to think and set up this powerful resistance movement which will be the return from the island of Elba in March 1815. This is why the forces of the Holy Alliance reject him, ostracizing him from humanity as an ‘anarchist’. He was in his time ‘the revolutionary emperor’ because his conquest was transformative for the social order.”

— Antoine Casanova, Vive la Révolution: 1789-1989: Réflexions autour du bicentenaire

#Antoine Casanova#Casanova#Vive la Révolution: 1789-1989: Réflexions autour du bicentenaire#Vive la Révolution#napoleon#napoleonic era#napoleonic#napoleon bonaparte#first french empire#french empire#history#france#french revolution#La Révolution française#Révolution française#19th century#the hundred days#hundred days#french history#revolution#Marxist history#Marxism

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

THE CIA'S SECRET GENOCIDE

youtube

One of the best documentaries RareEarth ever did, and still one of the best documentaries on YouTube, The CIAs Secret Genocide provides an in-depth dive into the history of Guatamala and its takeover by United Fruit Company and suffering under brutal US Imperialism.

"Anyone caught espousing anti-imperialism was called a terrorist and killed for actions against the State. Which wasn't really wrong, because the State existed for Imperialism. That was the system."

"he [General Ubico] was everything the CIA wanted and more. It's just that he wouldn't stop calling himself Hitler."

"So with the US media turning its Sauranic eye towards the oppressions of this openly Fascist ally, the CIA decided his time was up. But it wasn't like they wanted actual change. This was their goal. Hell, this was their guy. Fascism was fine for them, as long as it doesn't call itself that in public to the media."

"In 1954, Allen Dulles, head of the CIA, with the full backing of the United States Government, deliberately killed democracy in Guatemala. And just like that, a new Hitler in Power."

"The CIA's best plan for keeping the country in line was violence, and the more it slipped away, the more violence they inflicted to keep it in line."

"So for all their years of terror and enslavement, the company had no real response to a complete social collapse. All they knew how to do was what they'd always done. And so in response to this unprecedented threat to their power, the puppet government took off whatever velvet they pretended to still have left on those gloves and sent Death Squads roaming through the Mayan villages, breaking in doors and killing anyone they deemed a threat."

"It didn't matter if the people they killed were Communist or just happened to own some land that a local rich guy wanted to steal, their obituary always said 'terrorist'."

"The Civil War that followed would be the longest in the history of the Americas. It would last for the next 36 years, only truly ending in 1996. Although, calling it a Civil War implies that the country was divided, fighting itself, and for the most part that simply wasn't true. This was the violence of Imperialism brought by a puppet government against its own people."

(coughs) Ukraine!

Excuse me.

"In debt, and unable to keep control over the lands they'd stolen, United Fruit fell on its sword. Their name was so tarnished in the public eye that they had little choice but to be broken up and redistributed under new brands. But beyond that, little really changed except who got to be the 'us'."

"Today, United Fruit exists under the name Chiquita. They still sell bananas, and they still grow them in Guatamala."

"Since 1996, Guatamala has returned to a fledgeling form of democracy, it's just with the quiet understanding that things can only go so far before they're going to get toppled. Because things here never got returned to the peasants. This country is still a banana republic. And the United States is still an Empire."

#guatemala#guatamalan history#Guatamala history#cia#cia history#socialist history#socialism#communism#marxism leninism#socialist politics#socialist news#socialist worker#socialist#communist#marxism#marxist leninist#progressive politics#marxist history#history#us history#politics#allen dulles#us imperialism#western imperialism#us hegemony#united fruit company#chiquita#imperialism#us wars#banana republic

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

percolating an essay on the positionality of American millennials and their seeming inability to grow up in the context of their status as children in the golden age of the American middle class.

like, existing in a time where liberalism provided a near-utopian experience for white middle class folks to seeing it almost completely collapse in 2006-08 to existing off of fumes and oxygen until now as a material explanation for why they cling to childhood media and their weird youth conventions in very juvenile ways.

and being unable to cope with being the core adult cohort at this time while being outnumbered by a youth culture which is very critical of them in similar ways to which they were criticized by their elders while growing up.

not that this concept of generations is genuinely meaningful but white middle class American children born 1985-1995 were ideologically primed for a future that never came into being and it’s like they’ve frozen in a state of waiting for that future to come still, rather than actually adapting to the reality of their dynamic positions.

and I look at the children they’ve raised and I can’t help but wonder if that’s why the iPad kid comes into being - because their parents have done nothing but distract themselves from reality their whole lives.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

TODAY IN PHILOSOPHY OF HISTORY

Christopher Hill and Marxist History

Tuesday 06 February 2024 is the 112th anniversary of the birth of Christopher Hill (06 February 1912 – 23 February 2003), who was born in York on this date in 1912.

Hill, one of the most prominent British Marxist historians of his generation, dedicated his career as an historian to the early modern period in England, drawn to the period for its radical and revolutionary possibilities, writing books such as Intellectual Origins of the English Revolution, The Century of Revolution, 1603-1714, Some Intellectual Consequences of the English Revolution, and The World Turned Upside Down: Radical Ideas during the English Revolution.

Quora: https://philosophyofhistory.quora.com/

Discord: https://discord.gg/r3dudQvGxD

Links: https://jnnielsen.carrd.co/

Newsletter: http://eepurl.com/dMh0_-/

Podcast: https://podcasters.spotify.com/pod/show/nick-nielsen94/episodes/Christopher-Hill-and-Marxist-History-e2fe5t0

#philosophy of history#historians#Christopher Hill#Marxist history#Marxism#revolution#radicalism#Youtube

0 notes

Text

The chart does not capture the astonishing fact that these accomplishments were achieved under brutal sanctions imposed by the world’s superpower. Viva la revolución.

They also have ad-free TV ✌️📺 (you don’t need commercials with Socialism).

#cuba#important#fidel castro#current events#social justice#human rights#history#history posting#history tumblr#history side of tumblr#leftist#socialist#communist#marxist leninist#marxism leninism#marxist#socialism#leftism#leftisim#left wing#socialist politics#leftist politics#left wing politics#communism#anti capitalism#anti facist#anti imperialism#political#political posting#politics

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Harpo , Groucho, Chico, and Zeppo making an appearance as Arthur, Julius, Leonard and Herbert ❣️

#old hollywood#the marx brothers#leonard marx#zeppo marx#harpo marx#groucho marx#marx brothers#marxist#marxism#history

78 notes

·

View notes

Text

Soviet Teapot, 1970s

#soviet union#soviet art#soviet russia#soviet aesthetic#communist#communism#marxist leninist#marxism#ussr#history

80 notes

·

View notes

Text

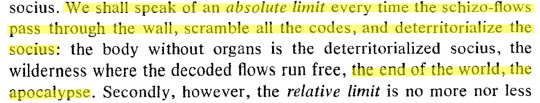

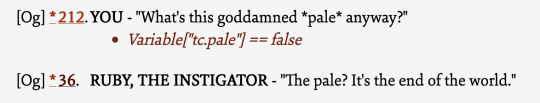

the pale without organs

disco elysium // félix guattari and gilles deleuze, anti-oedipus: capitalism and schizophrenia (1972) // sam shields (@dogffish), "hope, holes in the world & disco elysium"

#disco elysium#anti oedipus#capitalism and schizophrenia#ive been soooooooo insane about this for days like. ok so obviously i do not think it is a 1/1 comparison but kurvitz obviously read most#seminal marxist texts#and i see the pale less as a parallel of the body without organs and more like using the concept (in conjunction with benjamin's angel of#history) to build a sort of territorialized body without organs#the parallels are too many that it can't have been an inspiration i think. anyway. paradoxically helped me a bit understand the BwO concept#lol#antipsych#not really but i want it in that tag

60 notes

·

View notes

Note

all of your posts are usually so good. i show them to my 'progressive'(non-communist) friends pretty often to show them a developed Marxist worldview.

do you have any tips on how to further your development as a Marxist? id love to have the same capacity to analyze like you do

ultimately i can only give three good pieces of advice which is 1. read a lot and 2. do a lot of political activism in 'real life' so that you can understand how what you've read intersects with reality. and 3. when marx said 'ruthless criticism of all that exists' he wasn't kidding. & that isn't criticism as in, like, saying mean things obvsies, but like -- never accept anything because it is 'normal', never accept any transhistorical explanation about abstract factors like 'human nature' or 'the way things are'. investigate the historical and economic roots of everything you come up against. respond to 'common sense' with 'common among whom?' apply real critical consideration to just-so explanations and obvious truths because sometimes (often!) you will discover they are not so obvious.

#ask#silverthered#and ty!#nicey ask :)#and btw when i say read a lot dont ONLY read marxist theory you also have to read history#economic and oscial theory is vital and important but read history too!

213 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kurban Tulum (قۇربان تۇلۇم) (1883-1975) an Uyghur peasant who worked as a seasonal labourer for Uyghur landlords. During the land reforms of 1952, Kurban received land and various other properties. He is said to have visited Ürümqi, the capital of Xinjiang, by riding a donkey, to show his appreciation for the People's Liberation Army.

The People's Republic of China promotes him as a symbol of unity between the Uyghurs and Han Chinese. A song named "Where Are You Going, Uncle Kurban?" (库尔班大叔您去哪儿?) and a film titled Uncle Kurban Visits Beijing (库尔班大叔上北京) were produced in 2002. Monuments of Kurban's handshake with Mao stand in the town centres of Keriya and Hotan (Tuanjie Square).

#Chinese#Mao Zedong#China propaganda#Communist#Marxist leninist#Communism#Socialist#Marxism#China#中国#Uyghur#History#Uighur#Beijing#Türk#Cultural Revolution

145 notes

·

View notes

Text

Missing Fred Hampton extra 🙏🏼🙏🏼 now that was a man who could truly unite the people

#fred hampton#black panthers#marxism#marxist#rainbow coalition#civil rights#history#politics#black history#unity#leftist#antifascist#anti capitalism

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

History of The Hungarian People's Republic Part I

youtube

After WWI, Fascist Capitalist dictators were installed in Eastern European countries with the support of the Western Powers, including the United States.

In Hungary, as in Germany, Fascist forces mustered up enormous resources to disseminate anti-Communist and anti-Jewish propaganda to lay blame for Hungary's troubles on these populations.

This is just a small part of the incredible detail the Finish Bolshevik goes into while analyzing the history of the Hungarian People's Republic.

There's so much more and if you prefer to read rather than watch videos, here's the like to Part I:

#hungarian peoples republic#socialist history#communist history#history#socialist hungary#hungary#socialism#communism#marxism leninism#socialist politics#socialist worker#socialist news#socialist#communist#marxism#marxist leninist#progressive politics#politics#marxist history#history of marxism#historical materialism#dialectical materialism#history of hungary#hungary history#ussr history#ussr#soviet history#soviet union#socialist revolution#working class history

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

You Need to Read.

When people tell you to read, they aren't being pretentious. We are trying to help you. It wasn't until I started reading actual books that I realized how little you can inform yourself on Wikipedia and YouTube alone.

If you read books about race, you will understand racism better. If you read books about feminism, you will understand feminism better. If you want to deeply understand anything you will want to find a book about it. It will save you time to read books because you will understand faster. It will help you deeply understand issues so as to not be skewed by false analysis.

This does not mean that all books are good. Some are poorly written, some misrepresent evidence. Take time to find a good book from a scholar you respect. If it's an older text, find a podcast or guide breaking it down into easier language. There are thousands of good books out there, find one at your level to engage with. There's so much information that hasn't been made into an infographic.

#socialism#leftist#theory#communism#anarchism#leftblr#marxism#marxist leninist#history#politics#reading#academia#feminism#queer#colonialism#liberalism#leftism

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Capitalism was..."

#marxism#communism#socialism#marxism leninism#marxist leninist#fake screenshot#alternate history#alt history#ussr#I'm pretty sure i already posted this but i can't find it in my post history so.????

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

"In these circumstances, the commercial economy of the fur trade soon yielded to industrial economies focused on mining, forestry, and fishing. The first industrial mining (for coal) began on Vancouver Island in the early 1850s, the first sizeable industrial sawmill opened a few years later, and fish canning began on the Fraser River in 1870. From these beginnings, industrial economies reached into the interstices of British Columbia, establishing work camps close to the resource, and processing centers (canneries, sawmills, concentrating mills) at points of intersection of external and local transportation systems. As the years went by, these transportation systems expanded, bringing ever more land (resources) within reach of industrial capital. Each of these developments was a local instance of David Harvey's general point that the pace of time-space compressions after 1850 accelerated capital's "massive, long-term investment in the conquest of space" (Harvey 1989, 264) and its commodifications of nature. The very soil, Marx said in another context, was becoming "part and parcel of capital" (1967, pt. 8, ch. 27).

As Marx and, subsequently, others have noted, the spatial energy of capitalism works to deterritorialize people (that is, to detach them from prior bonds between people and place) and to reterritorialize them in relation to the requirements of capital (that is, to land conceived as resources and freed from the constraints of custom and to labor detached from land). For Marx the

wholesale expropriation of the agricultural population from the soil... created for the town industries the necessary supply of a 'free' and outlawed proletariat (1967, pt. 8, ch. 27).

For Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari (1977) - drawing on insights from psychoanalysis - capitalism may be thought of as a desiring machine, as a sort of territorial writing machine that functions to inscribe "the flows of desire upon the surface or body of the earth" (Thomas 1994, 171-72). In Henri Lefebvre's terms, it produces space in the image of its own relations of production (1991; Smith 1990, 90). For David Harvey it entails the "restless formation and reformation of geographical landscapes," and postpones the effects of its inherent contradictions by the conquest of space-capitalism's "spatial fix" (1982, ch. 13; 1985, 150, 156). In detail, positions differ; in general, it can hardly be doubted that in British Columbia industrial capitalism introduced new relationships between people and with land and that at the interface of the native and the nonnative, these relationships created total misunderstandings and powerful new axes of power that quickly detached native people from former lands. When a Tlingit chief was asked by a reserve commissioner about the work he did, he replied

I don't know how to work at anything. My father, grandfather, and uncle just taught me how to live, and I have always done what they told me-we learned this from our fathers and grandfathers and our uncles how to do the things among ourselves and we teach our children in the same way.

Two different worlds were facing each other, and one of them was fashioning very deliberate plans for the reallocation of land and the reordering of social relations. In 1875 the premier of British Columbia argued that the way to civilize native people was to bring them into the industrial workplace, there to learn the habits of thrift, time discipline, and materialism. Schools were secondary. The workplace was held to be the crucible of cultural change and, as such, the locus of what the premier depicted as a politics of altruism intended to bring native people up to the point where they could enter society as full, participating citizens. To draw them into the workplace, they had to be separated from land. Hence, in the premier's scheme of things, the small reserve, a space that could not yield a livelihood and would eject native labor toward the industrial workplace and, hence, toward civilization. Marx would have had no illusions about what was going on: native lives, he would have said, were being detached from their own means of production (from the land and the use value of their own labor on it) and were being transformed into free (unencumbered) wage laborers dependent on the social relations of capital. The social means of production and of subsistence were being converted into capital. Capital was benefiting doubly, acquiring access to land freed by small reserves and to cheap labor detached from land.

The reorientation of land and labor away from older customary uses had happened many times before, not only in earlier settler societies, but also in the British Isles and, somewhat later, in continental Europe. There, the centuries-long struggles over enclosure had been waged between many ordinary folk who sought to protect customary use rights to land and landlords who wanted to replace custom with private property rights and market economies. In the western highlands, tenants without formal contracts (the great majority) could be evicted "at will." Their former lands came to be managed by a few sheep farmers; their intricate local land uses were replaced by sheep pasture (Hunter 1976; Hornsby 1992, ch. 2). In Windsor Forest, a practical vernacular economy that had used the forest in innumerable local ways was slowly eaten away as the law increasingly favored notions of absolute property ownership, backed them up with hangings, and left less and less space for what E.P. Thompson calls "the messy complexities of coincident use-right" (1975, 241). Such developments were approximately reproduced in British Columbia, as a regime of exclusive property rights overrode a fisher-hunter-gatherer version of, in historian Jeanette Neeson's phrase, an "economy of multiple occupations" (1984, 138; Huitema, Osborne, and Ripmeester 2002). Even the rhetoric of dispossession - about lazy, filthy, improvident people who did not know how to use land properly - often sounded remarkably similar in locations thousands of miles apart (Pratt 1992, ch. 7). There was this difference: The argument against custom, multiple occupations, and the constraints of life worlds on the rights of property and the free play of the market became, in British Columbia, not an argument between different economies and classes (as it had been in Britain) but the more polarized, and characteristically racialized juxtaposition of civilization and savagery...

Moreover, in British Columbia, capital was far more attracted to the opportunities of native land than to the surplus value of native labor. In the early years, when labor was scarce, it sought native workers, but in the longer run, with its labor needs supplied otherwise (by Chinese workers contracted through labor brokers, by itinerant white loggers or miners), it was far more interested in unfettered access to resources. A bonanza of new resources awaited capital, and if native people who had always lived amid these resources could not be shipped away, they could be-indeed, had to be-detached from them. Their labor was useful for a time, but land in the form of fish, forests, and minerals was the prize, one not to be cluttered with native-use rights. From the perspective of capital, therefore, native people had to be dispossessed of their land. Otherwise, nature could hardly be developed. An industrial primary resource economy could hardly function.

In settler colonies, as Marx knew, the availability of agricultural land could turn wage laborers back into independent producers who worked for themselves instead of for capital (they vanished, Marx said, "from the labor market, but not into the workhouse") (1967, pt. 8, ch. 33). As such, they were unavailable to capital, and resisted its incursions, the source, Marx thought, of the prosperity and vitality of colonial societies. In British Columbia, where agricultural land was severely limited, many settlers were closely implicated with capital, although the objectives of the two were different and frequently antagonistic. Without the ready alternative of pioneer farming, many of them were wage laborers dependent on employment in the industrial labor market, yet often contending with capital in bitter strikes. Some of them sought to become capitalists. In M. A. Grainger's Woodsmen of the West, a short, vivid novel set in early modern British Columbia, the central character, Carter, wrestles with this opportunity. Carter had grown up on a rock farm in Nova Scotia, worked at various jobs across the continent, and fetched up in British Columbia at a time when, for a nominal fee, the government leased standing timber to small operators. He acquired a lease in a remote fjord and there, with a few men under towering glaciers at the edge of the world economy, attacked the forest. His chances were slight, but the land was his opportunity, his labor his means, and he threw himself at the forest with the intensity of Captain Ahab in pursuit of the white whale. There were many Carters.

But other immigrants did become something like Marx's independent producers. They had found a little land on the basis of which they hoped to get by, avoid the work relations of industrial capitalism, and leave their progeny more than they had known themselves. Their stories are poignant. A Czech peasant family, forced from home for want of land, finding its way to one of the coaltowns of southeastern British Columbia, and then, having accumulated a little cash from mining, homesteading in the province's arid interior. The homestead would consume a family's work while yielding a living of sorts from intermittent sales from a dry wheat farm and a large measure of domestic self-sufficiency-a farm just sustaining a family, providing a toe-hold in a new society, and a site of adaptation to it. Or, a young woman from a brick, working-class street in Derby, England, coming to British Columbia during the depression years before World War I, finding work up the coast in a railway hotel in Prince Rupert, quitting with five dollars to her name after a manager's amorous advances, traveling east as far as five dollars would take her on the second train out of Prince Rupert, working in a small frontier hotel, and eventually marrying a French Canadian farmer. There, in a northern British Columbian valley, in a context unlike any she could have imagined as a girl, she would raise a family and become a stalwart of a diverse local society in which no one was particularly well off. Such stories are at the heart of settler colonialism (Harris 1997, ch. 8).

The lives reflected in these stories, like the productions of capital, were sustained by land. Older regimes of custom had been broken, in most cases by enclosures or other displacements in the homeland several generations before emigration. Many settlers became property owners, holders of land in fee simple, beneficiaries of a landed opportunity that, previously, had been unobtainable. But use values had not given way entirely to exchange values, nor was labor entirely detached from land. Indeed, for all the work associated with it, the pioneer farm offered a temporary haven from capital. The family would be relatively autonomous (it would exploit itself). There would be no outside boss. Cultural assumptions about land as a source of security and family-centered independence; assumptions rooted in centuries of lives lived elsewhere seemed to have found a place of fulfillment. Often this was an illusion - the valleys of British Columbia are strewn with failed pioneer farms - but even illusions drew immigrants and occupied them with the land.

In short, and in a great variety of ways, British Columbia offered modest opportunities to ordinary people of limited means, opportunities that depended, directly or indirectly, on access to land. The wage laborer in the resource camp, as much as the pioneer farmer, depended on such access, as, indirectly, did the shopkeeper who relied on their custom.

In this respect, the interests of capital and settlers converged. For both, land was the opportunity at hand, an opportunity that gave settler colonialism its energy. Measured in relation to this opportunity, native people were superfluous. Worse, they were in the way, and, by one means or another, had to be removed. Patrick Wolfe is entirely correct in saying that "settler societies were (are) premised on the elimination of native societies," which, by occupying land of their ancestors, had got in the way (1999, 2). If, here and there, their labor was useful for a time, capital and settlers usually acquired labor by other means, and in so doing, facilitated the uninhibited construction of native people as redundant and expendable. In 1840 in Oxford, Herman Merivale, then a professor of political economy and later a permanent undersecretary at the Colonial Office, had concluded as much. He thought that the interests of settlers and native people were fundamentally opposed, and that if left to their own devices, settlers would launch wars of extermination. He knew what had been going on in some colonies - "wretched details of ferocity and treachery" - and considered that what he called the amalgamation (essentially, assimilation through acculturation and miscegenation) of native people into settler society to be the only possible solution (1928, lecture xviii). Merivale's motives were partly altruistic, yet assimilation as colonial practice was another means of eliminating "native" as a social category, as well as any land rights attached to it as, everywhere, settler colonialism would tend to do.

These different elements of what might be termed the foundational complex of settler colonial power were mutually reinforcing. When, in 1859, a first large sawmill was contemplated on the west coast of Vancouver Island, its manager purchased the land from the Crown and then, arriving at the intended mill site, dispersed its native inhabitants at the point of a cannon (Sproat 1868). He then worried somewhat about the proprieties of his actions, and talked with the chief, trying to convince him that, through contact with whites, his people would be civilized and improved. The chief would have none of it, but could stop neither the loggers nor the mill. The manager and his men had debated the issue of rights, concluding (in an approximation of Locke) that the chief and his people did not occupy the land in any civilized sense, that it lay in waste for want of labor, and that if labor were not brought to such land, then the worldwide progress of colonialism, which was "changing the whole surface of the earth," would come to a halt. Moreover, and whatever the rights or wrongs, they assumed, with unabashed self-interest, that colonists would keep what they had got: "this, without discussion, we on the west coast of Vancouver Island were all prepared to do." Capital was establishing itself at the edge of a forest within reach of the world economy, and, in so doing, was employing state sanctioned property rights, physical power, and cultural discourse in the service of interest."

- Cole Harris, “How Did Colonialism Dispossess? Comments from an Edge of Empire,” Annals of the Association of American Geographers, Vol. 94, No. 1 (Mar., 2004), p. 172-174.

#settler colonialism#settler colonialism in canada#dispossession#violence of settler colonialism#land theft#canadian history#indigenous people#first nations#reading 2024#cole harris#history of british columbia#reservation system#resource extraction#british empire#canada in the british empire#homesteading#marxist theory#capitalism#capitalism in canada#immigration to canada

25 notes

·

View notes

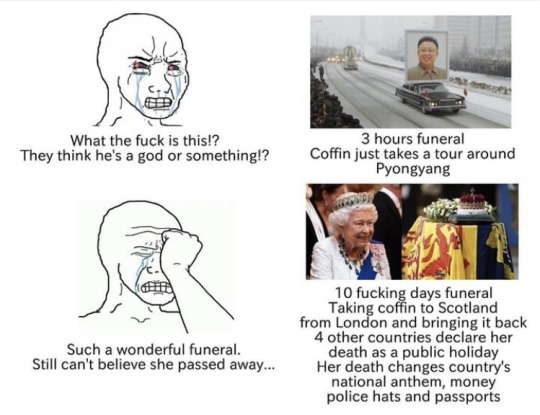

Text

#tumblr memes#meme#memes#meme humor#political memes#political humor#political shitposting#leftist memes#socialist memes#communist memes#marxist memes#communist#lol memes#lol#shitpost#dank humor#dank memes#dankest memes#humor#humour#funny#funny shit#funny memes#ha ha funny#history memes#history humour#history shitposting#funny meme haha#funny meme xd#funny post

385 notes

·

View notes