#close reading

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Note

I’d love if you ever expanded your thoughts on the way JKR writes romance, because it’s something I’ve been thinking about for a while. One thing that’s very interesting to me is that jealousy is used as a driving force for both of the main romantic storylines in HP. It’s more obvious with Ron/Hermione (the Yule Ball, basically everything that happens between them in book 6, the locket horcrux stuff) but also plays a big role in Harry/Ginny. Harry’s jealousy of her relationship with Dean is what makes him realize he’s into her, and moments where he’s pining for Ginny tend to focus on that jealousy more than an actual appreciation of Ginny’s personality. The most important part of writing a convincing romance is making readers believe that these characters actually care about each other and want to spend time together, and it feels like maybe what you describe as JKR’s obsession with pining made her lose sight of that. What do you think?

We've also got jealousy as a motif in Harry/Cho and Severus/Lily. It is absolutely a trope she uses, a lot.

When I was trying to get my head around how JKR writes romance, the main thing that made it click for me was realizing that, to her - romance is inherently threatening. And/or embarrassing, overpowering, animalistic, dangerous. (thanks to @the-phoenix-heart for that line.)

Really, the Harry Potter books are kind of a romance-free zone. It is incredibly unusual to see a romantic couple, acting like a couple, on the page. We spend a lot of time with Arthur and Molly, and while they’re both pretty fleshed out as characters, we get almost nothing of their couple dynamic (and what we do get doesn’t seem all that positive…) The blocking tends to physically separate them - Molly isn’t at the World Cup or Harry’s hearing, Arthur is working overtime when Harry is at the Burrow, etc. This is a pattern: her romantic couples, of which there are not many, have a way of being in different rooms, on different side quests, one of them is mind-controlled, one of them is unconscious, it cuts to black right before Harry kisses Cho, and right after he kisses Ginny.

Ron/Hermione takes place mostly outside of Harry’s perspective, and Harry/Ginny takes place mostly out of *the reader's* perspective. It’s a lot of narration, a lot of “Harry could not help himself talking to Ginny, laughing with her, walking back from practice with her” and “[Harry] was supposedly finishing his Herbology homework but in reality reliving a particularly happy hour he had spent down by the lake with Ginny at lunchtime.” Like, I don’t know. I might have liked to see those scenes play out.

Bill/Fleur is probably her most successful couple (I mean, who doesn't like Bill and Fleur?) But even they almost never interact with each other. They talk about their relationship to other people, other people talk about them, but like… I’m just going to go through a rundown of every single time we see Bill and Fleur interact:

“’E is always so thoughtful,” purred Fleur adoringly, stroking Bill’s nose. Ginny mimed vomiting into her cereal behind Fleur. Harry choked over his cornflakes.

(Romance = embarrassing)

What if [Ron and Hermione] became like Bill and Fleur, and it became excruciatingly embarrassing to be in their presence, so that he was shut out for good?

(Romance = embarassing, threatening)

Most [of the people at Dumbledore’s funeral] Harry did not recognize, but a few he did, including (...) Bill supported by Fleur and followed by Fred and George

(put a pin in this one, I’m going to come back to it)

“Bah,” said Fleur [in Harry’s body], checking herself in the microwave door, “Bill, don’t look at me — I’m ’ideous.”

(I actually think this is kind of cute in context, but unfortunately JKR is being uncharitable to her hyper-femme characters again, and making a joke about woman-in-male-body, which unfortunately makes it less cute in the grand scheme of things)

“I’m taking Fleur on a thestral,” said Bill. “She’s not that fond of brooms.” Fleur walked over to stand beside him, giving him a soppy, slavish look that Harry hoped with all his heart would never appear on his face again.

(Romance = embarrassing)

“We saw [Mad-Eye die]” said Bill; Fleur nodded, tear tracks glittering on her cheeks...

(Not sure if this counts as them interacting, but they are at least next to each other)

“No,” said Bill at once, “I’ll do it, I’ll come.” “Where are you going?” said Tonks and Fleur together. “Mad-Eye’s body,” said Lupin. “We need to recover it.”

(this one doesn’t even frame them as a couple, since the teams have split into Bill and Lupin and Tonks and Fleur.)

“We can’t tell you what we’re doing,” said Harry flatly. “You’re in the Order, Bill, you know Dumbledore left us a mission. We’re not supposed to talk about it to anyone else.” Fleur made an impatient noise, but Bill did not look at her.”

(... does this imply that Fleur isn’t in the Order? Anyway, they’re married at this point, and kinda disagreeing a la Molly and Arthur)

[Griphook] continued to request trays of food in his room, like the still frail Ollivander, until Bill (following an angry outburst from Fleur) went upstairs to tell him that the arrangement could not continue.

(Another conflict, but hey, at least it sounds like they resolved it. We hear about their daughter Victoire in the epilogue, but this is the last time we see Bill and Fleur together.)

But, okay. Not putting romance in the Harry Potter books is a perfectly fine creative choice. JKR can absolutely decide she just wants to give other things more emotional weight. What clarified this for me was the Fantastic Beasts films and her adult literature (particularly the Cormoran Strike books.) In those, JKR is wanting to write romance. And yet....

In Fantastic Beasts, she can write the awkward getting-to-know-you pre-romance stuff, but the second Jacob and Queenie are actually a couple - he loses his memory, then he’s brainwashed, she’s with Grindelwald, they’re different plot lines that never intersect… and then they just get married at the end of Secrets of Dumbledore. So it’s not even a slow-burn, will-they-won’t-they thing. Tina and Newt get the same treatment, except their pre-romance getting-to-know-you beats are so subtle that a lot of people missed them completely. Then Tina's angry at Newt for a very silly misunderstanding… then in a separate plotline… and is only in the third film for two minutes at the end. People compare the structure of these films to Indiana Jones, but in those movies the love interest is actually hanging out with Indy the whole time. In the Cormoran Strike books, the romantic leads do spend time together, but they’ve also been doing a pining, bad timing, will they/won’t they back-and-forth thing for seven books. And they’re long books.

So okay. What’s going on. Why is this.

JK Rowling has been very public about the trauma she has from abusive relationships and sexual assault, and I’m afraid I do have to bring that up in a conversation about why she treats romance so negatively. More specifically - if I had to guess - I think she finds male attraction towards women threatening. (I’m sure we all remember Harry’s chest monster.) I think she feels a little icky writing it, which is why when she does do it… it feels perfunctory, generic, repetitive, and also not the sort of thing that would come from a teenage boy. (Like when has a 14-year-old boy ever thought a girl was pretty because she had nice teeth. That’s such a straight girl compliment.) BUT, when she writes about the attractiveness of guys - it gets more specific, more nuanced, more interesting, and also a lot less uncomfortable. J.K. Rowling likes guys! She’s allowed.

But of course, she also tends to write male viewpoint characters, and I think this is why a lot of her guys (and Harry specifically) kinda read as queer to a lot of people. We’re told Harry is distracted by/attracted to Cho Chang… but is he though? Compared to the way “pretty boy” Cedric, or “sleek haired” Draco get under his skin?

I want to take a look at her adult romantic leads for a second. Because in Fantastic Beasts, she really did pull out all the stops to make Newt and Jacob as non-threatening as humanly possible. Newt is a gentle, pacifist, Doctor Dolittle-type conservationist who barely seems interested in women at all, and Jacob… is a Muggle baker. She pairs Newt with Tina, tough as nails American star auror. Jacob is with Queenie, who is constantly literally reading his mind. Which is an ability we’ve only seen with the most powerful wizards. These guys are not a threat to these ladies. In Queenie’s case, the power balance is tipped so insanely far in her direction that I’m a little bit worried for Jacob (and she does in fact, bewitch him into doing stuff.) I think JKR wrote her couples this way so any romance she wrote with them would also feel safe… and sadly I don’t think it worked. The most fleshed out couple dynamic we get is Dumbledore/Grindelwald, who have a coffee date and a duel in the third movie. But - that’s the one movie where she doesn’t have sole screenwriting credit, they’re exes, and they're also both GUYS, so she doesn’t have to worry about any kind of male/female power imbalance gunk, or put herself in the headspace of a guy being attracted to women.

Now I do want to talk about Cormoran Strike. Of all her non-threatening male love interests, this is the one who seems to work best for her. She’s stuck with him the longest, and it actually seems possible that we might get an actual romantic scene with him in the next book.

Here’s my theory. I think that when JKR was writing Goblet of Fire, and it came time to introduce the real Mad-Eye Moody - imprisoned in the bottom of his own trunk, weak, down a leg and an eye - something clicked. Because that is someone who is both entirely masculine, and entirely safe, and that makes him the perfect romantic figure. And I absolutely think she grabbed that archetype when it came to writing Cormoran Strike.

Basically, this character just is Mad-Eye Moody, only 15(ish) years younger, and non-magical. Strike is an ex-military cop who now freelances. He’s older than his love interest, he’s been around the block a few times. He’s gruff, but careful and kind, world-weary and grizzled, extremely capable, principled, tough, and just sort of hyper aware of what’s going on around him. He is also a bigger guy with some access weight who is not “conventionally attractive” - and for JKR this is a feature, not a bug. If your female character is into someone who is not *~*~handsome~*~* that means they’re cool, deep, not like other girls. Viktor Krum is not conventionally attractive, and (after the werewolf attack) neither is Bill. In fact “he now bore a distinct resemblance to Mad-Eye Moody.” JKR likes Mad-Eye Moody.

And you better believe that Cormoran Strike has a broken nose and a missing leg, just like Mad-Eye Moody. Strike’s prosthetic leg comes up a *lot.* I think it’s telling that the loving interaction we see between Bill and Fleur is her physically supporting him at Dumbledore's funeral post werewolf attack, and the loving little wrist squeeze we get between Lucius and Narcissa is right before Lucius hands his wand over. Basically, JKR likes someone who is sexy and capable and has a lot of presence, but who you get to take care of, and who… can’t chase you. Doesn’t pose a threat. That's the fantasy.

#hp#jkr critical#mad eye moody#cormoran strike#jacob kowalski#newt scamander#bill x fleur#bill weasley#harry x draco#harry x cedric#dumbledore x grindelwald#literary analysis#close reading#anti jkr

359 notes

·

View notes

Text

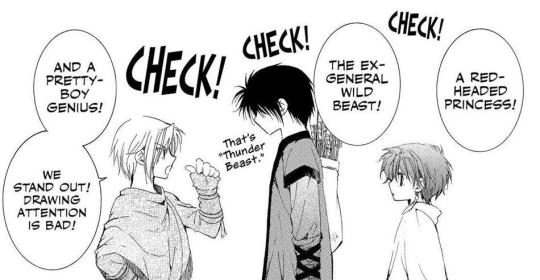

sotr content is awesome, great, amazing, but i wanted to talk a little more about the meta of the books.

tbosas is the only book in the 5 that is not in first person!!!!!! its in 3rd, which is super interesting. not only is the reader not allowed to see snow's "inner thoughts," but we are alienated entirely from *being him.* with the main trilogy and now sotr, we become katniss/haymitch because of the first person narration. it's pretty widely accepted (at least in the communities of which I am a part) that every time suzanne collins comes out with another thg book, it's because people didn't get the message with the previous books (for more info, see the epigraphs of each book in the order in which they were released; they get more and more specific) and she wants to really just nails it in to us. the main trilogy came out about 10 years ago, so i barely noticed the change in narration styles until I read sotr and tbosas back to back. then, it sticks out like a sore thumb. Collins purposefully wants the reader to connect to the districts because of the social and class commentary that goes along with affiliating with the districts and not the capitol. POV is how authors can control who "has" the narrative and snow is NEVER supposed to be in control of the overall narrative; he is never truly in control of the districts.

i was also struck with the differences in pacing when it comes to tbosas and sotr. the overarching story of tbosas is snow's story. it follows LGB because she is affiliated with him, but ultimately, it opens on him and follows his mentorship journey through the games, and then moves on to him after the games as a peacekeeper. sotr is almost more of an homage to the 2nd QQ featuring haymitch (which is much more in line with the original trilogy) but focusing on the games, but of course it is. haymitch is a spark, but he doesn't end up lighting the revolution. beetee is his predecessor, and he's a predecessor to katniss, so although he is the protagonist of sotr, the true focus of the book is not haymitch himself, but how he influences the games and the revolution.

#ballad of songbirds and snakes#bookblr#haymitch abernathy#the hunger games#books#sunrise on the reaping#sotr#tbosas#close reading

67 notes

·

View notes

Text

What Makes Feyre’s Pregnancy Plotline in A Court of Silver Flames so Upsetting?

The answer is that the events and outcome concerning Feyre’s pregnancy speak to a fear of one’s loss of autonomy, specifically one’s reproductive autonomy. Furthermore, this plotline demonstrates Maas' consistent prioritization of her male characters at the expense of her female characters. Multiple factors make this subplot feel particularly uncomfortable and upsetting, but I can condense them into three main points that converge to create one frustrating scenario.

1. Rhysand and the Question of Choice

From ACOMAF onwards, the reader is made aware of Rhysand’s unusually progressive politics and his attention to the autonomous choices of women. This is demonstrated through his selection of counsel, appointing Mor and Amren in roles of authority, and eventually crowing Feyre as High Lady of the Night Court. In addition to this, we are shown his emphasis on choice through his interactions with Feyre. Rhysand repeatedly reminds Feyre that she can choose, that she can make an autonomous decision that he will respect. So, it is these positive features of Rhysand that make the pregnancy subplot of ACOSF so disturbing.

He, and the Inner Circle by extension, purposefully omit the information that Feyre’s pregnancy will turn deadly and never volunteer the information to her. During Cassian’s meeting with Rhysand and Amren, we are shown their thought process behind withholding information from Nesta (and Feyre by extension) According to Amren, it is not lying because they are technically not telling lies in the traditional sense, only withholding information.

While this is about Nesta, the reader can see the parallels between both cases. The choice to lie by omission reveals that both Amren and Rhysand are aware of the dishonesty of their actions, choosing to mitigate it slightly on a technicality. It feels distinctly like a loophole in Rhysand’s previous promises to Feyre, making this act feel more deceitful while demonstrating Rhysand’s willingness to undermine Feyre’s authority as High Lady. If Rhysand had a condition or illness that would eventually kill him, informing him of it would be certain, you wouldn’t even consider the possibility of not telling him. However, because Feyre is pregnant, she is not afforded the same autonomy.

Wanting to keep Feyre in blissful ignorance is not a sufficient reason, especially when Feyre is still of sound mind and can advocate for herself. Rhysand’s reasoning sounds noble, but in reality, it is just benevolent sexism. It doesn’t matter if he thinks it will cause Feyre stress, she NEEDS to be aware of what’s going on and the fact that the news will ruin her peaceful pregnancy is of little consequence when her life is on the line. Rhysand prioritizes his feelings and implicitly gives himself executive authority over Feyre’s pregnancy, demonstrating his disregard for her autonomy and choices. This action directly contradicts the progressive beliefs Rhysand stated in previous books and is a betrayal for the reader as well as Feyre.

2. The Infantilization of Feyre

The omission of this critical information, good intentions or not, is based on a belief that Feyre would not be competent enough to handle such a pressing situation in her pregnant state. Amren claims that the stress and fear could have physically harmed Feyre, but such a claim assumes that Feyre would not have the fortitude or ability to handle the situation.

Amren's explanation demonstrates a belief that Feyre's input on the matter would be irrelevant and pointless because it prevents Feyre from offering any. It is a plan that assumes Feyre will not be able to add anything meaningful to the solution and that it would be less harmful to her if she was kept out of it. This is infantilizing and paternalistic because Feyre has proven herself to be capable of coping under pressure and happens to be an unprecedented magical anomaly. Feyre’s access to pertinent medical information should not be revoked and it is insane that Madja her physician, actively misleads her with Rhysand’s consent.

This infantilization of a pregnant character echoes how pregnant women have been infantilized throughout history. It is a terrifying thought to imagine that your bodily autonomy could be stripped from you in the name of serving your supposed best interest. Rosemary’s Baby is one of the most famous horror movies of all time and it explores this exact topic, the same is true for the short story The Yellow Wallpaper, both stories capture the horror of reproductive/medical abuse that still happens to women today.

3. The Aftermath & Prioritizing Male Rage

Lastly, one of the most disturbing elements of this subplot is the way the text consistently prioritizes and coddles the violent rage of male characters at the expense of female characters. This is on full display when Rhysand flies into an intense rage after Nesta reveals the truth to Feyre. Although Nesta can be faulted for her harsh phrasing, let it be known that even Feyre felt that she did the right thing and was expressing her anger at the paternalistic and unjust practices of the Inner Circle. However, Nesta is still subjected to severe physical and emotional punishment in the form of a grueling hike where she is left to stew in her guilt and suicidal ideation despite Feyre ultimately not faulting her.

Feyre admits that Rhysand “majorly overreacted” and that she wanted Nesta back in Velaris. And yet, Nesta is still punished. But why? Will Rhysand or any of the Inner Circle be punished for betraying Feyre? Why, if Feyre agreed that Nesta was right to tell her, would she ever need to be subjected to a severe punishment when she was justified in what she did?

This is a particularly telling detail that compels me to ask: is this punishment about Feyre’s feelings or Rhysand’s? Why is it that Rhysand’s “overreaction” needs to be assuaged by punishing Nesta? What I observe from this passage is the characters prioritizing the feelings of a male character and placating him with the suffering of a female character, even when he wasn’t the one who was hurt in that situation. Feyre asks Cassian to tell Rhysand that the hike will be Nesta's punishment as though it isn't truly a punishment, but it undoubtedly is.

Throughout the hike, Nesta is in a silent spiral of guilt and self-hatred, Cassian never tells her that Feyre is alright and that Rhysand overreacted, letting her dwell in it alone. He hardly speaks to her, he pushes her to the point of exhaustion and is somehow surprised that Nesta shows signs of suicidal ideation.

This isn't constructive at all, it is not evidence that Cassian cares about Nesta's well-being, and the scenes of Nesta internally repeating that she deserves to die and that everyone hates her are nothing but gratuitous and disgustingly self-indulgent. The text basks in Nesta's suffering, even when she was in the right and this hike only happened to placate Rhysand who wronged Feyre in the first place.

Hindsight am I right? Fuck off. A more productive resolution to this matter would be for Feyre and Nesta to talk it out ALONE. Feyre could express her feelings to Nesta directly and they could find a solution together, that way Feyre’s situation could be centered on the two sisters working together. Cassian can see that Feyre is alright, she’s obviously upset, but she didn’t crumble like he expected and that makes it completely baffling that he would punish Nesta anyway. It’s a solution that prioritizes his and Rhysand’s feelings as opposed to Feyre’s, making it not about a perceived transgression against Feyre, but against Rhysand.

In Conclusion

This topic has already been discussed at length by many people in the fandom, but it is a topic that still stays on my mind with how upsetting it is. It is a stunning example of the misogynistic undertones in Sarah J Maas’s writing and makes reading a very straining experience due to her obvious bias towards certain male characters. Not even her main character matters when Rhysand is factored into the situation, his emotions are always centred by other characters and is permitted to betray his wife and get off scot free.

Feyre’s reproductive autonomy is violated, and Maas doesn’t bat an eye. But when Nesta rightfully reveals the truth to Feyre, everyone loses their mind. Both Nesta and Feyre have their autonomy stripped away from the, by way of the Inner Circle’s paternalism, and when Nesta advocates for herself and Feyre, she is punished severely. Being put in her place as the hierarchy is strengthened.

#a court of silver flames#acotar#nesta archeron#acotar meta#feyre archeron#amren#rhysand critical#rhysand#cassian#sarah j maas#acosf meta#anti nessian#close reading#acotar analysis#anti sarah j maas#anti sjm#anti inner circle

256 notes

·

View notes

Text

Arwen, Elves, Honorary Elves and Mortals

There's been some interesting discussion and speculation about Arwen, and how her portrayal in The Tale of Aragorn and Arwen can be reconciled with her depiction as being someone both wise and compassionate.

Sticking points seem to be her revelation that she held scorn for the men of Numenor who turned to evil due to their fear of death, the fact she only felt the pain of mortality at Aragorn's death, despite the deaths of those she can supposed to have known during her reign (Merry, Pippin, Eomer, Faramir and Eowyn) having already taken place at this point, and the fact that despite not yet being weary of life, on Aragorn's death, she left Minas Tirith and her children and grandchildren, in order to return to Lothlorien, where she died.

Now, the Faithless who Arwen felt scorn for did terrible things (including human sacrifice) and caused a great deal of suffering. But the fact that on feeling the pain of mortality herself she could suddenly feel pity for them, suggests a rather self-centred attitude. That it was only Aragorn's death that seemed to enlighten her to the pain of mortality, despite living amongst mortals for 120 years, in itself suggests a lack of empathy.

Depression and a wish to die is not a moral fault, but that Arwen still felt young and did not wish to die until Aragorn died, whilst still having children and grandchildren, indicates that the bonds she had with her children and grandchildren were significantly of lesser value to her.

My interpretation is that while Arwen was wise, compassionate and benevolent, to receive her full compassion and respect, a degree of elvishness was required.

I will look at the three relationships Arwen had with non-elves to demonstrate this.

"Aragorn was abashed, for he saw the elven-light in her eyes and the wisdom of many days; yet from that hour he loved Arwen Undomiel daughter of Elrond. ‘In the days that followed Aragorn fell silent, and his mother perceived that some strange thing had befallen him; and at last he yielded to her questions and told her of the meeting in the twilight of the trees. ‘‘My son,’’ said Gilraen, ‘‘your aim is high, even for the descendant of many kings. For this lady is the noblest and fairest that now walks the earth. And it is not fit that mortal should wed with the Elf-kin.’’

Appendix-A

When Arwen and Aragorn meet, it is love at first sight for Aragorn, yet not for Arwen. Aragorn is made to look and feel rather a foolish, punching above his weight in his love for Arwen.

However, we cannot credit Arwen with being simply too wise to fall in love with a person at first sight. Arwen does fall in love with Aragorn at first sight, and on doing so made the decision to part with her family, a parting that would last beyond the afterlife, in order to be with him, but only once Aragorn is not only made to look kingly, but elvish.

Aragorn was grown to full stature of body and mind, and Galadriel bade him cast aside his wayworn raiment, and she clothed him in silver and white, with a cloak of elven-grey and a bright gem on his brow. Then more than any king of Men he appeared, and seemed rather an Elf-lord from the Isles of the West. And thus it was that Arwen first beheld him again after their long parting; and as he came walking towards her under the trees of Caras Galadhon laden with flowers of gold, her choice was made and her doom appointed.

Appendix-A

One look at Aragorn, now elven in appearance, Arwen was willing to give up everything to be with him.

Despite knowing that her marriage to Aragorn hinged upon him becoming a king, and a king of mortals, there is no indication that Arwen ever leaves the kingdoms of elves in order to mix with mortals, to meet with them and learn from them. She is wise and compassionate, but her wisdom and compassion has been formed to be elven centric.

The best example of Arwen's wisdom and compassion is shown through her dealings with Frodo. Frodo, she offers her place on the boats to Valinor, accurately predicting that his suffering will one day cause him too much suffering and he will need to find respite.

"But the Queen Arwen said: ‘A gift I will give you. For I am the daughter of Elrond. I shall not go with him now when he departs to the Havens; for mine is the choice of Luthien, and as she so have I chosen, both the sweet and the bitter. But in my stead you shall go, Ring-bearer, when the time comes, and if you then desire it. If your hurts grieve you still and the memory of your burden is heavy, then you may pass into the West, until all your wounds and weariness are healed. But wear this now in memory of Elfstone and Evenstar with whom your life has been woven!’ And she took a white gem like a star that lay upon her breast hanging upon a silver chain, and she set the chain about Frodo’s neck. ‘When the memory of the fear and the darkness troubles you,’ she said, ‘this will bring you aid.’"

-Arwen-RotK

This is a significant act of kindness and wisdom, and as Frodo is our central protagonist, our main hero (along arguably with Sam), it is Arwen's act that facilitates a happy (if bittersweet) ending for Frodo.

Yet Frodo, of all the hobbits, is one that is considered more elvish than most.

And for a moment he lifted up the Phial and looked down at his master, and the light burned gently now with the soft radiance of the evening-star in summer, and in that light Frodo’s face was fair of hue again, pale but beautiful with an Elvish beauty, as of one who has long passed the shadows.

–Sam, TtT

“Lugburz wants it, eh? What is it, d’you think? Elvish it looked to me, but undersized. What’s the danger in a thing like that?”

– Shagrat, TtT

“If hard days have made me any judge of Men’s words and faces, then I may make a guess at Halflings! Though,” and now he smiled, “there is something strange about you, Frodo, an elvish air, maybe. But more lies upon our words together than I thought at first.”

-Faramir -TtT

It is also worth noting that Arwen's father, Elrond, and Arwen's grandmother, Galadriel, were ring-bearers, which would have perhaps further emphasised Frodo's "elvishness" to Frodo. Compare this to Elrond and Galadriel, and their friendships with those of different races, particularly dwarves, he kindness and respect Galadriel shows Gimli is not "justified" by any show of elvishness on Gimli's part, Gimli is a dwarf, loud and proud, yet Galadriel honours him, and grants him a gift, three hairs, that she denied Feanor.

The final relationship I shall look at is one told of only through the appendices, that being Arwen and Elanor's relationship.

We get little detail here of Arwen and Elanor's personal dynamic, but we do know that Arwen took Elanor as a maid (supposedly a "maid of honour" as opposed to a serving maid), for a time.

"Thain Peregrin has been there many times; and so has Master Samwise the Mayor. His daughter Elanor the Fair is one of the maids of Queen Evenstar.’

-Appendix-A

Like Frodo, Elanor was considered elvish, more elf than hobbit.

"She became known as ‘the Fair’ because of her beauty; many said that she looked more like an elf-maid than a hobbit.

-Elanor-Appendix-B

All the relationships Arwen had with non-elves, were with those who had elvish qualities, and in Aragorn's case, hinged upon those elvish qualities.

Arwen was not alone among Man during her reign. In Ithilien, Legolas had a colony of elves, Ithilien being close to Minas Tirith.

"he (Gimli) became Lord of the Glittering Caves. He and his people did great works in Gondor and Rohan. For Minas Tirith they forged gates of mithril and steel to replace those broken by the Witch-king. Legolas his friend also brought south Elves out of Greenwood, and they dwelt in Ithilien, and it became once again the fairest country in all the westlands."

Appendix-A

Arwen would have had, for a while at least, elvish company and elvish friends, negating any need for her to form friendships among mortals, or endeavour to look at the world through a mortal mindset.

Legolas left after Aragorn's death, and we can suspect he was among the last of the elves to do so.

"But when King Elessar gave up his life Legolas followed at last the desire of his heart and sailed over Sea"

Appendix-A

It is on Aragorn's death that we get to see a side of Arwen, other than the gracious, beautiful queen.

"She was not yet weary of her days, and thus she tasted the bitterness of the mortality that she had taken upon her."

-Arwen-Appendix-A

This is an important point to consider when looking at her following actions. Arwen still felt young, Arwen still wished to live, yet Aragorn's death consequentially means Arwen's death.

‘ ‘‘Nay, dear lord,’’ she said, ‘‘that choice is long over. There is now no ship that would bear me hence, and I must indeed abide the Doom of Men, whether I will or I nill: the loss and the silence. But I say to you, King of the Numenoreans, not till now have I understood the tale of your people and their fall. As wicked fools I scorned them, but I pity them at last. For if this is indeed, as the Eldar say, the gift of the One to Men, it is bitter to receive.’’

-Arwen-Appendix-A

This quote is fascinating on many levels. First of all, it is left ambiguous if Arwen would have chosen to go to Valinor if a boat would take her, she says that no boat will take her now, whether she willed it or not. Her choice now is irrelevant, she has no choice, and she offers no comfort as to whether she would make that choice again.

In fact, her shift in attitude towards mortality even indicates that despite her widsdom, she made that choice before she could fully understand the pain of mortality.

Then she speaks of her judgement towards the Faithless, her scorn now replaced with pity. A significant shift in stance, driven entirely by her personal sufferings.

And the final thing worth considering, whereas Aragorn's death would not doubt have hit her harder than any others, that she underwent such a significant alteration in her attitudes towards mortality, despite living among mortals for many years, having witnessed their deaths, having witnessed their grief at others' deaths (including Aragorn's grief at the deaths of Eomer, Merry, Pippin, Eowyn and Faramir, who we knew Aragorn cared for deeply, and even if Arwen never bonded with them herself, might have cared for on his behalf) is striking.

That Arwen herself has not fully felt the sting of mortality to this point, even to a lesser degree than Aragorn's, indicates that Arwen formed no bonds herself with any mortals, whose deaths she suffered significantly for.

Aragorn's death would have hurt Arwen the most, perhaps more than any other deaths combined, her was her husband, her life partner, her one true love, but the deaths she would have experienced before his might have started to open her eyes towards the pain of mortality, might have allowed her to start having a more nuanced view towards the Faithless, yet they did not.

"‘But Arwen went forth from the House, and the light of her eyes was quenched, and it seemed to her people that she had become cold and grey as nightfall in winter that comes without a star. Then she said farewell to Eldarion, and to her daughters, and to all whom she had loved; and she went out from the city of Minas Tirith and passed away to the land of Lorien, and dwelt there alone under the fading trees until winter came. Galadriel had passed away and Celeborn also was gone, and the land was silent. ‘There at last when the mallorn-leaves were falling, but spring had not yet come, she laid herself to rest upon Cerin Amroth; and there is her green grave, until the world is changed, and all the days of her life are utterly forgotten by men that come after, and elanor and niphredil bloom no more east of the Sea."

Arwen left behind her son and daughters, who would have been grieving for their father, in order to die, far from the mortal land that she had been queen of for 120 years, which held her mortal friends and family, in preference of a fading elven kingdom.

We should not judge Arwen's feelings and love for her children entirely on a choice made in a time of great grief and suffering, but there is another interesting tidbit, that gives us a small insight into Arwen's feelings towards her daughters.

The making of Lembas Bread was passed down by elven women, yet the recipe for Lembas Bread was forgotten after Arwen's death, despite Arwen having two daughters she could pass the recipe down to.

The Nature of Middle-earth, "Part Three. The World, its Lands, and its Inhabitants: IV. The Making of Lembas", "Text 2", p. 296

These daughters would have been part elf, yet for whatever reason, they were never taught to make Lembas Bread, and the practise was lost after Arwen's death. Does this suggest the daughters were not, in Arwen's mind or in practise, "elven" enough to receive and use this knowledge? Did they fail or refuse to learn, or did Arwen refuse to teach them? Either way, with so much of Arwen's respect for others seeming to hinge on their "elvishness" (most notably Aragorn's elven makeover) it can give another indication as to why Arwen left them to so she could die after the death of Aragorn.

As a part elf herself, Arwen did seem to have an affinity with non-elves with elvish qualities, perhaps seeing in them another "child of two worlds" figure, yet in her attitudes towards her own part-elven children, the two distinguishing moments in her narrative between them and herself, the leaving them to die after Aragorn's death, and the failure to pass down the recipe for Lembas, are marked by there being a general lack. She loved them, but not enough to live, not enough to stay. And she didn't share with them the knowledge that had been passed down to her by her mother and grandmother. Perhaps whereas mortals who "aspired" to be like a "higher being" (elves), Arwen's children had become too much like the "lesser beings" (Man).

Arwen has a limited presence on page, so it is perhaps unjust to judge her overmuch, with so much of her personality a blank, yet consistently, we see from Arwen a marked preference for those exhibiting "elvish qualities", and either an overt or subtextual lack of compassion and understanding for other mortals.

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

Inuyasha Chapter 119

Kikyo's Arrow

Probably a 5/5 chapter. Continues to explore established themes and digs into the characters of Kikyo, Inuyasha, and Kagome and their “love triangle.” This chapter essentially is the "love triangle" manifesting in a physical fight while Miroku remains fixated on how Inuyasha's body will fuse with the demon's whether he wins or loses the fight.

There is not a lot regarding Inuyasha’s thoughts on the situation, at least not directly, but his actions enable us to draw conclusions about his feelings while also leaving some wiggle room for interpretation. Kikyo and Kagome are a more direct commentary on the dynamic between these three characters, with both girls coming at the situation with their own biased perspectives.

We get "'I've got to get Kikyo's body to a safe place!' If I don't, Inuyasha will continue fighting that demon, in order to protect her...because Inuyasha will never abandon Kikyo!" from Kagome and "Fool...now that you've shown up...Inuyasha has lost his reason..." from Kikyo.

Though Kikyo’s perspective is informed by her dislike for Kagome and her belief that Inuyasha prefers Kagome, she comes off as a more objective observer simply because she can tell that what Kagome says about Kikyo is true for Kagome as well: Inuyasha will never abandon her. Kagome’s reflections are also tainted by sadness–she is hurt by Inuyasha’s dedication to Kikyo–while Kikyo’s are more tainted by annoyance and anger.

Inuyasha fights to defend both girls, but when he notices Kagome is there, it does come across as his rage slamming into a wall of shock, like a weightier role of protector falls on his shoulders. His thoughts reiterate: "Blast it. My only choice is to fight!"

Kikyo’s presence made him think “Why is she here…?!” (which is also what Kagome thought) whereas Kagome’s feels more like “oh shit.” To be fair–her arrival means he now has to protect two people he loves.

Regarding Kikyo specifically, she continues to be a fascinating character. The poison imp steals the souls of the dead inside of Kikyo's body and declares: "The woman...she ain't human, eh? Then I'll make her part of me..." and so we get the continuation of the question: what is Kikyo? What are the impacts of death? How do souls factor in? Kikyo possesses a body made of clay; a fragment of Kagome/her original soul; and the stolen souls of girls who have died, but she is not human and not living. And now this demon, which consumes other demons, wants to make her part of it. Has Kikyo become a semi-demonic figure? She wanted Inuyasha to become human but has ended up becoming something not quite human herself.

This also connects back to Kikyo’s observations about Naraku in the previous volume: “The evil aura that permeates the castle…emanates from this man…?! What is this man?! I cannot feel any life force within his body at all. It’s as if he’s dead from the neck down.”

There’s a bunch of should-be-dead people in this love tangle (adding Naraku to the triangle), with demons giving Kikyo and Naraku new “life.” If the Shikon Jewel keeps playing out its own history in an endless cycle, I guess it is fitting that it now goes through the motions of that history with the dead like a haunting.

#inuyasha#inuyasha manga#inuyasha chapter 119#inuyasha volume 13#kikyo#kagome higurashi#inukag#analysis#close reading#naraku#annotations#why start at chapter 1 when you can start at 119?#lol sorry this is just how it happened#I'll post my book reviews for the previous volumes#but I started going chapter by chapter for this volume#I'll circle back and elaborate on the prior volumes eventually#nobody asked for this but I ran out of characters on goodreads and had to chop all my thoughts#so here they are

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

In the Silmarillion fandom, we enjoy grabbing the trope of “Nolofinwëan recklessness” and running wild with it.

The most common victims of this are Fingon the Rash Prince and Fingolfin the Impulsive King, who rushes into suicidal combat. Both father and son daring death within Morgoth’s domain.

It’s fun to write and exciting to imagine, no doubt, but I’d like to offer a different take. In fact, what makes Fingon and Fingolfin (and the rest of that family) compelling to me is their patience and endurance.

Yes, I’m aware Fingon rushes to battle at Alqualondë, but that’s a world-altering event. The light of the world has literally gone out, murder has happened in Valinor, Finwë is dead. Most of the Noldor are up on their feet and ready to depart. Everyone is rushing.

But this is not always the case with Fingon. Most significantly, the rescue of Maedhros is NOT an impulsive decision. The published Silmarillion offers no timeline on this, but in The Grey Annals, five entire years pass between the arrival of Fingolfin’s host to Beleriand and Fingon’s decision to look for Maedhros.

Five years in which the two hosts are quite literally on the verge of civil war because, let’s not forget:

No love was there in the hearts of those that followed Fingolfin for the House of Fëanor, for the agony of those that endured the crossing of the Ice had been great, and Fingolfin held the sons the accomplices of their father.

Diplomacy is a painfully slow (and absolutely frustrating!) ordeal. Fingon’s decision is born from this strife, from thirty years on the Helcaraxë, and five years of civil restlessness, not to mention the clear signs that Morgoth is ready to attack them at any moment:

Then Fingon the valiant, son of Fingolfin, resolved to heal the feud that divided the Noldor, before their Enemy should be ready for war; for the earth trembled in the Northlands with the thunder of the forges of Morgoth underground.

This is not rashness. This is the sacrifice of a captain who is willing to make the best of what time is left before full-out destruction begins. It would be rashness if Fingon got his company and crossed Mithrim to wage battle on the Fëanorians. Instead, he chooses differently for the sake of peace, stability, and renewed friendship.

The trek from Lake Mithrim to Thangorodrim could be estimated at around 150 miles, depending on the map we follow, and there are grasslands and two sets of mountains to cross, not to mention the horror of Thangorodrim. Fingon travels on foot. It would take him weeks, maybe even months, to find Maedhros. Plenty of time for the fire of rashness to cool down if that was the case. But he persists because he has no other choice.

Similarly, I often see takes on Fingolfin that he rushes to pointless combat with Morgoth in the same manner as Fëanor had done. Yet again, the timeline is crucial here. The published Silmarillion has the battle lasting at least several months. Bragollach starts in F.A. 455 during winter time:

There came a time of winter, when night was dark and without moon

The battle slows down presumably a few months later:

but the Battle of Sudden Flame is held to have ended with the coming of spring, when the onslaught of Morgoth grew less.

The onslaught grows less, but it doesn’t fully cease. Morgoth and Sauron reissue their attacks early into Fingon’s kingship.

In the Grey Annals, the timeline is stretched further out:

Year 455:

The Fell Year. Here came an end of peace and mirth. In the winter, at the year's beginning, Morgoth unloosed at last his long-gathered strength

Year 456:

Now Fingolfin, King of the Noldor, beheld (as it seemed to him) the utter ruin of his people, and the defeat beyond redress of all their houses, and he was filled with wrath and despair.

The fighting goes on actively anywhere from a season to a full year! Fingolfin tries to hold his kingdom together for a full year despite an absolute, unquestionable disaster. I mean, look at this description of the battle:

In the front of that fire came Glaurung the golden, father of dragons, in his full might; and in his train were Balrogs, and behind them came the black armies of the Orcs in multitudes such as the Noldor had never before seen or imagined. And they assaulted the fortresses of the Noldor, and broke the leaguer about Angband, and slew wherever they found them the Noldor and their allies, Grey elves and Men. Many of the stoutest of the foes of Morgoth were destroyed in the first days of that war, bewildered and dispersed and unable to muster their strength. War ceased not wholly ever again in Beleriand

Fingolfin’s decision to ride out, again, is not out of recklessness or a spur-of-the-moment decision. It’s everything but that. He has given everything and truly believes it’s all lost: “the utter ruin of his people, and the defeat beyond redress of all their houses.” (!!!)

This is a final stand, the King’s duty to stand by his people, even in death.

#fingon#fingolfin#maedhros#rescue of maedhros#dagor bragollach#close reading#silm#silmarillion#tolkien#long post#cw: war#cw: death

385 notes

·

View notes

Text

I appreciate the words “found time” in this title because it means that’s not all he was doing. That he’s been doing other things, possibly been more busy with those if he needed to find time, and those things might’ve even been helping solve the murder of Ramsey! It really highlights the absurdity that he’s selfish for having a hobby as a priority in any capacity, rather than his priorities solely being problems that need to be solved.

And it does implicitly indicate, yknow, that part of the premise for this take being absurd is that he IS doing something for the world, he can do both. He could easily enjoy himself and help people at the same time. And that his happiness shouldn’t have to derive solely from helping people. People who only care about their own comfort and not addressing the world’s ills in any capacity ARE an issue, but this man is not one of them, not necessarily because he had to find time when most of it is occupied with something else, gee I wonder what?

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

god i'm such a whore for juxtapositional dichotomy. top ten literary tools honestly.

what do you mean someone is their own foil? what do you mean they contain multitudes, all sitting at odds with one another? why haven't they burst forth at the seems? how are they holding it all together? it's so intricate. it's so beautiful. it's so interesting.

#writing#writeblr#writblr#dichotomy#writers effects#close reading#literary analysis#academia#academia aesthetic#poetry#poetryblr#poetblr#writers of tumblr#writers on tumblr#writing community

50 notes

·

View notes

Text

So I was rewatching the GID scene from Idolish7 and I realized something quite clever about the writing.

Two of the three kidnapped idols are held in abandoned, isolated buildings and are not gagged. Makes sense. No need to gag them if no one can hear them.

But the third?

He's held in an apartment building. And guess what?

He's gagged!

I love clever writing details like that in bondage scenes!

#English major go brrrrrr#close reading#idolish7#GID#whump#anime#episodes 14-15 of season 3 if anyone was curious

47 notes

·

View notes

Text

Just saw someone on here say the Baz Luhrmann Romeo & Juliet is “considered the most faithful movie version of Romeo and Juliet” and had to stop myself from chasing them down the internet like the meme goose going “BY WHO?! BY WHO!?????” Don’t start internet beef over this, self! They didn’t say THEY liked it best! They might be an innocent bystander! Also you are weirdly aggressive about Shakespeare!

Okay, deep breath, short post. Short post! We can do this!

Romeo and Juliet has an oddly small cinematic footprint, compared to its cultural impact. That’s probably why Luhrmann’s version can still hold any primacy. (Gods, are there English teachers showing this in class? Because they don’t have to fast-forward through the Zefferelli nudity? What a thought. Stay on target.) I can only theorize that other Shakespeare plays get more adaptations because they’re centered on a huge male role, so they can be a Serious Showpiece for a single male actor. R&J doesn’t operate that way.

And in my experience (having seen four or five live productions, off the top of my head) it’s a play that really lives in the theater. Stupid as it sounds, every time I see Romeo and Juliet live, some part of me feels like this time, it might end happy. The letter might not go astray: the messenger won’t get caught in a quarantine, Romeo will know Juliet isn’t dead, and everything will turn out fine. It’s so often noted that the play isn’t structured as a tragedy, but as a New Comedy (like Midsummer Night’s Dream, et c. — a story about young people defying their parents for love) that goes wrong: somehow this works on me, in person, such that I really think maybe we’ll pull it off! The kids will be all right, the parents will be chastened, and all will end well. It breaks my heart, every time, when it doesn’t.

I have small quibbles with the Luhrmann R&J, but I won’t enumerate them here. I simply want to point out that Luhrmann makes the most appalling directorial choice he possibly could. And he’s not the only one! This choice was in vogue during the 19th century in England (which is also when Bowdler took the naughty bits out of Shakespeare, so…yeah. Not very concerned with being faithful to the text.) Luhrmann, and the rest of the 19th century text-criminals, have Juliet wake up while Romeo is still dying.

I suppose some of you are now going, “why is that such a terrible thing? It allows for more acting!” Well, yeah, that’s why the hams of the London stage liked to do it in Romantic and Victorian times. Everything for more melodrama!

But it’s a sin against the text, and I’ll tell you why. That breathless stupid hope I talked about above, that the entire play’s structure induces? The hope that everything will turn out right? It builds up in you like a flood, and everything goes wrong again, and the entire weight of your hope is penned up in your heart, and they came so close! It was so close to being all right, but Romeo kills himself, and nothing will be all right.

And Juliet wakes up, still a citizen of the Country of Hope where this trick is so clever and Romeo’s going to save her, and she finds him there. And nothing makes sense to her. He was supposed to be here, but he was supposed to be alive. It’s a cruel inversion of her hopes, it’s her love made Death at last, it’s her whole world collapsing. We know how close it came to being all right, but she doesn’t know. She despairs. She sees he poisoned himself. And then she kisses him. And she says,

“Thy lips are warm.”

Now she knows as clearly as we do how nearly they were together, how close they came to a happy ending. Total understanding crashes over her, and crashes out of us. It’s the perfectly weighted moment of catharsis for the entire play. No lie: just typing her words above, I started crying with no warning. It’s the sharpened point of the play in Juliet’s heart, and ours. Those four words are the most devastating, understated thing. They are the cold, uncaring touch of Death.

And if she saw him die, they don’t work. They make no sense. She sounds like a fool saying them. And the whole weight of the play lands wrong, because some director thought he knew better than William Shakespeare how to wring the salt tears from human hearts.

#Shakespeare nerd#favorite play#Romeo and Juliet#performance history#fuck bowdler#fuck the Victorians#failed happy ending#fuck baz luhrmann#responding over here#theater#william shakespeare#Shakespeare#i have too many opinions#i have studied this intensely#close reading#catharsis#drama#in my feels

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Manipulative/Morally Grey Dumbledore? An In-Depth Canon Analysis

So when I look at Harry Potter, my goal is to separate what I think the books are intending to say, from what they actually say, from what the movies say… and what the common fan interpretation is. So today I’m interested in Dumbledore, and specifically in the common headcanon of Manipulative/Morally Gray Dumbledore. Is that (intentionally or unintentionally) supported by the text?

PART I: Omniscient Dumbledore

“I think he knows more or less everything that goes on here”

In Book 1, yes Dumbledore honestly does seem to know everything. He 100% arranged for Harry to find the Mirror of Erised, publicly left Hogwarts in order to nudge Quirrell into going after the Stone, and knew what Quirrell was doing the whole time. It is absolutely not a stretch, and kind of heavily implied, that the reason the Stone’s protections feel like a little-end-of-the-year exam designed to put Harry through his paces… is because they are. As the series goes on this interpretation only gets more plausible, when we see the kind of protections people can put up when they don’t want anyone getting through.

Book 1 Dumbledore knows everything… but what he’s actually going to do about it is anyone’s guess. One of the first things we learn is that some of Dumbledore’s calls can be… questionable. McGonagall questions his choice to leave Harry with the Dursleys, Hermione questions his choice to give Harry the Cloak and let him go after the Stone, Percy and Ron both matter-of-factly call him “mad.” The “nitwit, blubber, oddment, tweak” speech is a joke where Dumbledore says he’s going to say a few words, then literally does say a few (weird) words. I know there are theories that those particular words are supposed to be insulting the four houses, or referencing the Hogwarts house stereotypes, or that they’re some kind of warning. But within the text, this is pure Lewis Carroll British Nonsense Verse stuff (and people came up with answers to the impossible Alice in Wonderland “why is a raven like a writing desk” riddle too.)

This characterization also explains a lot of Dumbledore’s decisions about how to run a school, locked in during Book 1. Presumably Binns, Peeves, Filch, Snape are all there because Dumbledore finds them funny, atmospheric, and/or character building. He's just kind of a weird guy. He absolutely knew that Lockhart was a fraud in Book 2 (with that whole “Impaled upon your own sword, Gilderoy?” thing after Lockhart oblivates himself. ) So maybe he is also there to be funny/atmospheric/character building, or to teach Harry a lesson about fame, or because Dumbledore is using the cursed position to bump off people he doesn’t like. Who knows.

(I actually don’t think JKR had locked in “the DADA position is literally cursed by Voldemort” until Book 6. )

Dumbledore absolutely knows that Harry is listening in when Lucius Malfoy comes to take Hagrid to Azkaban, and it’s fun to speculate that maybe he let himself get fired in Book 2 as part of a larger plan to boot Lucius off the Board of Governors. So far, that’s the sort of thing he’d do. But in Books 3 and 4, we are confronted with a number of important things that Dumbledore just missed. He doesn’t know any of the Marauders were animagi, he doesn’t know what really happened with the Potter’s Secret Keeper, doesn’t know Moody is Crouch, and doesn’t know the Marauders Map even exists. But in Books 5 and 6, his omniscience does seem to come back online. (In a flashback, Voldemort even comments that he is "omniscient as ever” when Dumbledore lists the specific Death Eaters he has in Hogsmeade as backup.) Dumbledore knows exactly what Draco and Voldemort are planning, and his word is taken as objective truth by the entire Order of the Phoenix - who apparently only tolerate Snape because Dumbledore vouches for him:

“Snape,” repeated McGonagall faintly, falling into the chair. “We all wondered . . . but he trusted . . . always . . . Snape . . . I can’t believe it. . . .” “Snape was a highly accomplished Occlumens,” said Lupin, his voice uncharacteristically harsh. “We always knew that.” “But Dumbledore swore he was on our side!” whispered Tonks. “I always thought Dumbledore must know something about Snape that we didn’t. . . .” “He always hinted that he had an ironclad reason for trusting Snape,” muttered Professor McGonagall (...) “Wouldn’t hear a word against him!”

McGonagall questions Dumbledore about the Dursleys, but not about Snape. I see this as part of the larger trend of basically Dumbledore’s deification. In the beginning of the series, he’s treated as a clever, weird dude. By the end, he’s treated like a god.

PART II: Chessmaster Dumbledore

“I prefer not to keep all my secrets in one basket.”

When Dumbledore solves problems, he likes to go very hands-off. He didn’t directly teach Harry about the Mirror of Erised - he gave him the Cloak, knew he would wander, and moved the Mirror so it would be in his path. He sends Snape to deal with Quirrell and Draco, rather than do it himself. He (or his portrait) tells Snape to confund Mundungus Fletcher and get him to suggest the Seven Potters strategy. He puts Mrs. Figg in place to watch Harry, then ups the protection in Book 5 - all without informing Harry. The situation with Slughorn is kind of a Dumbledore-manipulation master class - even the way he deliberately disappears into the bathroom so Harry will have enough solo time to charm Slughorn. Of course he only wants Slughorn under his roof in the first place to pick his brain about Voldemort… but again, instead of doing that himself, he gets Harry to do it for him.

Dumbledore has a moment during Harry’s hearing in Book 5 (which he fakes evidence for) where he informs Fudge that Harry is not under the Ministry’s jurisdiction while at Hogwarts. Which has insane implications. It’s never explicitly stated, but as the story goes on, it at least makes sense that Dumbledore is deliberately obscuring how powerful he is, and how much influence he really has, by getting other people to do things for him. But the problem with that is because he is so powerful, it become really easy for a reader to look back after they get more information and say… well if Dumbledore was controlling the situation… why couldn’t he have done XYZ. Here are two easy examples from Harry’s time spent with the Dursleys:

1. Mrs. Figg is watching over Harry from day one, but she can’t tell him she’s a squib and also she has to keep him miserable on purpose:

“Dumbledore’s orders. I was to keep an eye on you but not say anything, you were too young. I’m sorry I gave you such a miserable time, but the Dursleys would never have let you come if they’d thought you enjoyed it. It wasn’t easy, you know…”

It’s pretty intense to think of Dumbledore saying “oh yes, invite this little child over and keep him unhappy on purpose.” But okay. It’s important to keep Harry ignorant of the magical world and vice versa. fine. But once he goes to Hogwarts… that doesn’t apply anymore? I’m sure when Harry thinks he’s going to be imprisoned permanently in his bedroom during Book 2, it would’ve been comforting to know that Dumbledore was sending around someone to check on him. And when he literally runs away from home in Book 3… having the address of a trusted adult that he could easily get to would have been great for everybody.

2. When Vernon is about to actually kick Harry out during Book 5, Dumbledore sends a howler which intimidates Petunia into insisting that Harry has to stay. Vernon folds and does exactly what she says. If Dumbledore could intimidate Petunia into doing this, then why couldn’t he intimidate her into, say - giving Harry the second bedroom instead of a cupboard. Or fixing Harry’s glasses. In Book 1, the Dursleys don’t bother Harry during the entire month of August because Hagrid gives Dudley a pig’s tail. In the summer between third and fourth year, the Dursleys back off because Harry is in correspondence with Sirius (a person they fear.) But the Dursleys are afraid of all wizards. Like at this point it doesn’t seem that hard to intimidate them into acting decently to Harry.

PART III: Dumbledore and the Dursleys

“Not a pampered little prince”

JKR wanted two contradictory things. She wanted Dumbledore to be a fundamentally good guy: a wise, if eccentric mentor figure. But she also wanted Harry to have a comedically horrible childhood being locked in a cupboard, denied food, given broken glasses and ill fitting/embarrassing clothes, and generally made into a little Cinderella. Then, it’s a bigger contrast when he goes to Hogwarts and expulsion can be used as an easy threat. (Although the only person we ever see expelled is Hagrid, and that was for murder.)

So, there are a couple of tricks she uses to make it okay that Dumbledore left Harry at the Dursleys.’ The first is that once Harry leaves… nothing that happens there is given emotional weight. When he’s in the Wizarding World, he barely talks about Dursleys, barely thinks about them. They almost never come up in the narration (unless Harry’s worried about being expelled, or they’re sending him comedically awful presents.) They are completely cut from movies 4, 6, and 7 part 2 - and you do not notice.

The second trick… is that Dumbledore himself clearly doesn’t think that the Dursleys are that bad. During the King’s Cross vision-quest, he describes 11-year-old Harry as “alive and healthy (...) as normal a boy as I could have hoped under the circumstances. Thus far, my plan was working well.”

Now, this could have been really interesting. Like in a psychological way, I get it. Dumbledore had a rocky home life. Dad in prison, mom spending all her time taking care of his volatile and dangerous sister. Aberforth seems to have reacted to the situation by running completely wild, it’s implied that he never even had formal schooling… and Albus doubled down on being the Golden Child, making the family look good from the outside, and finding every means possible to escape. I would have believed it if Molly or Kingsley had a beat of being horrified by the way the Dursleys are treating Harry… but Dumbledore treats it as like, whatever. Business as usual.

But that isn’t the framing that the books use. Dumbledore is correct that the Dursleys aren’t that bad, and I think it’s because JKR fundamentally does not take the Dursleys seriously as threats. I also think she has a fairly deeply held belief that suffering creates goodness, so possibly Harry suffering at the hands of the Dursleys… was necessary? To make him good? Dumbledore himself has an arc of ‘long period of suffering = increased goodness.’ So does Severus Snape, Dudley‘s experience with the Dementor kickstarts his character growth, etc. It’s a trope she likes.

It’s only in The Cursed Child that the Dursleys are given any kind of weight when it comes to Harry’s psyche. This is one of the things that makes me say Jack Thorne wrote that play, because it’s just not consistent with how JKR likes to write the Dursleys. It’s consistent with the way fanfiction likes to write the Dursleys. And look, The Cursed Child is fascinatingly bad, I have so many problems with it, but it does seem to be doing like … a dark reinterpretation of Harry Potter? And it’s interested in saying something about cycles of abuse. I can absolutely see how the way the play handles things is flattering to JKR. It retroactively frames the Dursleys’ abuse in a more negative way, and maybe that’s something she wanted after criticism that the Harry Potter books treat physical abuse kind of lightly. (i.e. Harry at the hands of the Dursleys, and house-elves at the hands of everybody. Even Molly Weasley “wallops” Fred with a broomstick.)

PART IV: Dumbledore and Harry

“The whole Potter–Dumbledore relationship. It’s been called unhealthy, even sinister”

So whenever Harry feels betrayed by Dumbledore in the books - and he absolutely does, it’s some of JKR’s best writing - it’s not because he left him with the Dursleys. It’s because Dumbledore kept secrets from him, or lied to him, or didn’t confide in him on a personal level.

“Look what he asked from me, Hermione! Risk your life, Harry! And again! And again! And don’t expect me to explain everything, just trust me blindly, trust that I know what I’m doing, trust me even though I don’t trust you! Never the whole truth! Never!” (...) I don’t know who he loved, Hermione, but it was never me. This isn’t love, the mess he’s left me in. He shared a damn sight more of what he was really thinking with Gellert Grindelwald than he ever shared with me.”

Eventually though, Harry falls in line with the rest of the Order, and treats Dumbledore as an all-knowing God. And this decision comes so close to being critiqued… but the series never quite commits. Rufus Scrimgeour comments that, “Well, it is clear to me that [Dumbledore] has done a very good job on you” - implying that Harry is a product of a deliberate manipulation, and that the way Harry feels about Dumbledore is a direct result of how he's been controlling the situation (and Harry.) But Harry responds to “[You are] Dumbledore’s man through and through, aren’t you, Potter?” with “Yeah, I am. Glad we straightened that out,” and it’s treated as a badass, mic drop line.

Ron goes on to say that Harry maybe shouldn’t be trusting Dumbledore and maybe his plan isn’t that great… but then he abandons his friends, regrets what he did, and is only able to come back because Dumbledore knew he would react this way? So that whole thing only makes Dumbledore seem more powerful? Aberforth tells Harry (correctly) that Dumbledore is expecting too much of him and he’s not interested in making sure that he survives:

“How can you be sure, Potter, that my brother wasn’t more interested in the greater good than in you? How can you be sure you aren’t dispensable (...) Why didn’t he say… ‘Take care of yourself, here’s how to survive’? (...) You’re seventeen, boy!”

But, Aberforth is treated as this Hamish Abernathy type who has given up, and needs Harry to ignite his spark again. There’s a pretty dark line in the script of Deathly Hallows Part 2:

Which at least shows this was a possible interpretation the creative team had in their heads… but then of course it isn’t actually in the movie.

So in the end, insane trust in Dumbledore is only ever treated as proper and good. Then in Cursed Child they start using “Dumbledore” as an oath instead of “Merlin” and it’s weird and I don’t like it.

PART V: Dumbledore and his Strays

“I have known, for some time now, that you are the better man.”

So Dumbledore has this weird relationship pattern. He has a handful of people he pulled out of the fire at some point and (as a result) these people are insanely loyal to him. They do his dirty work, and he completely controls them. This is an interesting pattern, because I think it helps explain why so many fans read Dumbledore’s relationship with Snape (and with Harry) as sinister.

Let’s start with the first of Dumbledore’s “strays.” Dumbledore saves Hagrid's livelihood and probably life after he is accused of opening the Chamber of Secrets - and then he uses Hagrid to disappear Harry after the Potters' death, gets him to transport the Philosopher’s Stone, and he’s the one who he trusts to be Harry’s first point of contact with the Wizarding World. Also, Hagrid's situation doesn’t change? Even after he is cleared of opening the Chamber of Secrets, he keeps using that pink flowered umbrella with his broken wand inside, a secret that he and Dumbledore seem to share. He could get a legal wand, he could continue his education. But he doesn’t seem to, and I don’t know why.

So, Harry Potter and the Methods of Rationality is a well known fix-it fic that basically asks “What if Harry Potter was a machiavellian little super genius who solves the plot in a year?” I enjoyed it when it was coming out, but the only thing I would call a cheat is the way McGonagall brings Harry to Diagon Alley instead of Hagrid. Because a Harry Potter who has spent a couple of days with McGonagall is going to be much better informed, better equipped and therefore more powerful than a Harry spending the same amount of time with Hagrid. McGonagall is both a lot more knowledgeable and a lot less loyal to Dumbledore. She is loyal, obviously, but she also questions his choices in a way that Hagrid never does. And as a result, Dumbledore does not trust her with the same kind of delicate jobs he trusts to Hagrid.

Mrs. Figg is another one of Dumbledore’s strays. She’s a squib, so we can imagine that she doesn’t really have a lot of other options, and he sets her up to keep tabs on (and be unpleasant to) little Harry. He also has her lie to the entire Wizangamot, which has got to present some risk. Within this framework, Snape is another very clear stray. Dumbledore kept him out of Azkaban, and is the only reason that the Order trusts him. He gets sent on on dangerous double-agent missions… but before that he’s sort of kept on hand, even though he’s clearly miserable at Hogwarts. Firenze is definitely a stray - he can't go back to the centaurs, and who other than Dumbledore is going to hire him? And I do wonder about Trelawney. We don’t know much about her relationship with Dumbledore, but I wouldn’t be at all surprised if she was a stray as well.

I think there was an attempt to turn Lupin into a stray that didn’t… quite work. He is clearly grateful to Dumbledore for letting him attend Hogwarts and then for hiring him, but Lupin doesn’t really hit that necessary level of trustworthy that the others do. Most of what Dumbledore doesn’t know in Book 3 are things that Lupin could have told him, and didn’t. If had to think of a Watsonsian reason why Remus is given all these solo missions away from the other Order members (that never end up mattering…) it’s because I don’t think Dumbledore trusts him that much. Lupin doubts him too much.

“Dumbledore believed that?” said Lupin incredulously. “Dumbledore believed Snape was sorry James was dead? Snape hated James. . . .”

We also see Dumbledore start the process of making Draco into a stray by promising to protect him and his parents. And with all of that… it’s kind of easy to see how Harry fits the profile. He has a very bleak existence (which Dumbledore knows about.) He is pulled out of it by Dumbledore’s proxies. It’s not surprising that Harry develops a Hagrid-level loyalty, especially after Dumbledore saves him from Barty, from his Ministry hearing, and then from Voldemort. Harry walks to his death because Dumbledore told him too.

Just to be clear, I don’t think this pattern is deliberate. I think this is a side effect of JKR wanting to write Dumbledore as a nice guy, and specifically as a protector of the little guy. But Dumbledore doing that while also being so powerful creates a weird power dynamic, gives him a weird edit. It’s part of the reason people are happy to go one step farther and say that the Dursleys were mean to Harry… because Dumbledore actively wanted it that way. I don’t think that’s true. I think Dumbledore loves his strays and if anything, the text supports the idea that he is collecting good people, because protecting them and observing them serves some psychological function for him. Dumbledore does not believe himself to be an intrinsically good person, or trustworthy when it comes to power. So, of course someone like that would be fascinated by how powerless people operate in the world, and by people like Hagrid and Lupin and Harry, who seem so intrinsically good.

PART VI - Dumbledore and Grindelwald

“I was in love with you.”

I honestly see “17-year-old Dumbledore was enamored with Grindelwald” as a smokescreen distracting from the actual moral grayness of the guy. He wrote some edgy letters when he was a teenager, at least partly because he thought his neighbor was hot. He thought he could move Ariana, but couldn’t - which led to the chaotic three-way duel that killed her.

One thing I think J. K. Rowling does understand pretty well, and introduces into her books on purpose, is the concept of re-traumatization. Sirius in Book 5 is very obviously being re-traumatized by being in his childhood home and hearing the portrait of his mother screaming. It’s why he acts out, regresses, and does a number of unadvisable things. I think it’s also deliberate that Petunia’s unpleasant childhood is basically being re-created: her normal son next to her sister’s magical son. It's making her worse, or at the very least preventing her from getting better. We learn that Petunia has this sublimated interest in the magical world, and can even pull out vocab like “Azkaban” and “Dementor” when she needs to. She wrote Dumbledore asking to go to Hogwarts, and I could see that in a universe where Petunia didn’t have to literally raise Harry, she wouldn’t be as psychotically into normalness, cleanliness, and order as she is when we meet her in the books. After all, JKR doesn’t like to write evil mothers. She will be bend over backwards so her mothers are never really framed as bad.

And I honestly think it’s possible that J. K. Rowling was playing with the concept of re-traumatiziation when she was fleshing out Dumbledore in Book 7. We learn all this backstory, that… honestly isn’t super necessary? All I’m saying is that the three-way duel at the top of the Astronomy Tower lines up really well with the three-way duel that killed Ariana. Harry is Ariana, helpless in the middle. Draco is Aberforth, well intentioned and protective of his family - but kind of useless, and kind of a liability. Severus is Grindelwald, dark and brilliant, and one of the closest relationships Dumbledore has. If this was intentional, it was probably only for reasons of narrative symmetry… but I think it's cool in a Gus Fring of Breaking Bad sort of way, that Dumbledore (either consciously or unconsciously) has been trying to re-create this one horrible moment in his life where he felt entirely out of control. But the second time it plays out… he can give it what he sees as the correct outcome. Grindelwald kills him and everyone else lives. That is how you solve the puzzle.

If you read between the lines, Dumbledore/Grindelwald is a fascinating love story. I like the detail that after Ariana’s death, Dumbledore returns to Hogwarts because it’s a place to hide and because he doesn’t feel like he can be trusted with power. I like that he sits there, refusing promotions, refusing requests to be the new Minister of Magic, refusing to go deal with the growing Grindelwald threat until he absolutely can’t hide anymore, at which point he defeats him (somehow.) I like reading his elaborate plan to break Elder Wand’s power as both a screw-you to Grindelwald, the wand’s previous master, but also as a weirdly romantic gesture. In Albus Dumbledore’s mind, there is only Grindelwald. Voldemort can’t even begin to compare. I like the detail that Grindelwald won’t give up Dumbledore, even under torture. And, Dumbledore doesn’t put him in Azkaban. He put him in this other separate prison, which always makes it seem like he’s there under Dumbledore authority specifically. Maybe Dumbledore thinks that if he had died that day instead of Ariana…he wouldn’t have had to spend the rest of his life fighting and imprisoning the man he loves.

And then of course, Crimes of Grindelwald decided to take away Dumbledore's greatest weakness and say that no, actually he was a really good guy who never did anything wrong ever. He went all that time without fighting Grindelwald because they made a magical friendship no-fight bracelet. Dumbledore is randomly grabbing Lupin’s iconography (his fashion sense, his lesson plans, his job) in order to feel more soft and gentle than the person the books have created. Now Dumbledore knows about the Room Requirement, even though in the books it’s a plot point that he's too much of a goody-two-shoes to have ever found it himself. He loved Grindelwald (past tense.) And Secrets of Dumbledore is mostly about him being an omniscient mastermind so that a magical deer can tell him that he was a super good and worthy guy, and any doubt that he’s ever felt about himself is just objectively wrong and incorrect. Also now Aberforth has a neglected son, so he’s reframed as a bit of a hypocrite for getting on his brother’s case for not protecting Harry.

So to summarize, I think Dumbledore began the series as this very eccentric, unpredictable mentor, whose abilities took a hit in Books 3 and 4 in order to make the plot happen. He teetered on the edge of a ‘dark’ framing for like a second… but at the the end of the series he's written as basically infallible and godlike. I’ve heard people say that JKR’s increased fame was the reason she added the Rita Skeeter plot line, and I don’t think that’s true. But I do think her fame may have affected the way she wrote Dumbledore. Because Dumbledore is JKR’s comment on power, and by Book 5 she had so much power. In her head, I don’t think that Dumbledore is handing off jobs in a manipulative way. She sees him as empowering other less powerful people. That is his job as someone in power (because remember - people who desire power shouldn't wield it.)