#ancestral landscapes

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Ancestral Landscapes - Primordial

youtube

0 notes

Text

#ancestral puebloans#Anasazi#archaeology#adventure#travel#my photo#desert#southwest#utah#mountains#photography#aesthetic#scenery#landscape#ruins#beauty#bears ears

147 notes

·

View notes

Text

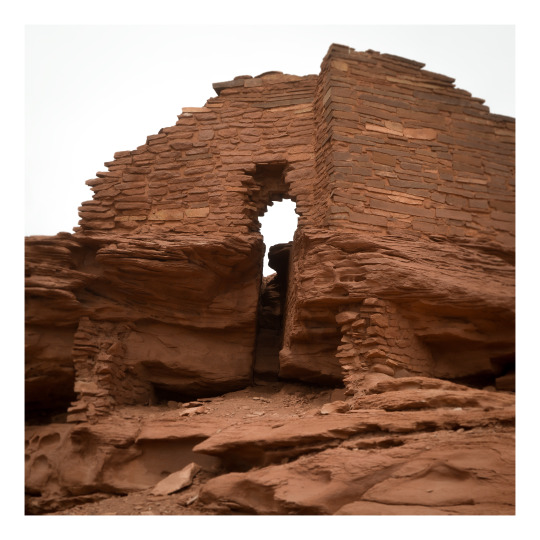

The Wukoki ruins at Wupatki National Monument, in Coconino County, Arizona.

#photographers on tumblr#landscape#ruins#Wukoki#Wupatki National Monument#San Francisco Peaks#Ancestral Puebloan People#Coconino County#Arizona

250 notes

·

View notes

Text

Delmarva Fox Squirrel, a subspecies of the fox squirrel located in coastal Virginia and Maryland.

Chincoteague National Wildlife Refuge, Virgina

2021

#chincoteague#wildlife refuge#a very important squirrel#squirrel#Sciuridae#travel#original photography#photographers on tumblr#photography#lensblr#nature#nature photography#landscape#landscape photography#delmarva#virginia#pueblo#ancestral Puebloan#native American#native American architecture#indigenous architecture#wanderingjana

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

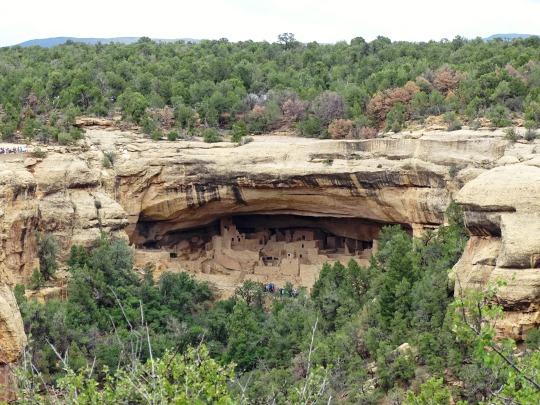

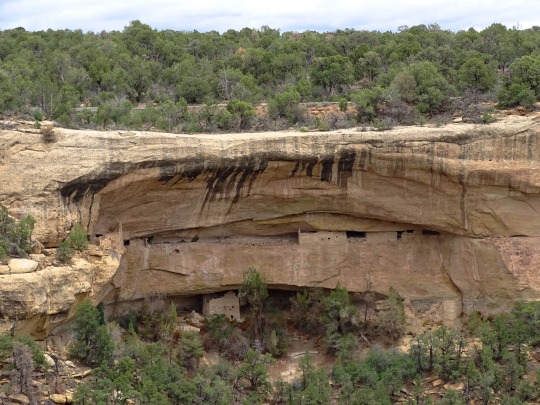

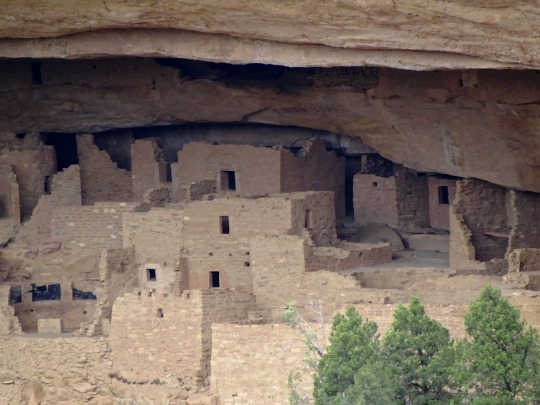

Cliff Palace, Mesa Verde National Park (No. 13)

Cliff Palace is the largest cliff dwelling in North America. The structure built by the Ancestral Puebloans is located in Mesa Verde National Park in their former homeland region. The cliff dwelling and park are in Montezuma County, in the southwestern corner of Colorado, in the Southwestern United States.

Tree-ring dating indicates that construction and refurbishing of Cliff Palace was continuous approximately from 1190 CE through 1260 CE, although the major portion of the building was done within a 20-year time span. The Ancestral Puebloans, also known as Anasazi, who constructed this cliff dwelling and the others like it at Mesa Verde were driven to these defensible positions by "increasing competition amidst changing climatic conditions". Cliff Palace was abandoned by 1300, though debate is ongoing as to the cause. Some contend that a series of megadroughts interrupting food production systems was the main cause.

Cliff Palace was rediscovered in 1888 by Richard Wetherill and Charlie Mason while they were looking for stray cattle.

Source: Wikipedia

#Cliff Palace#Mesa Verde National Park#cliff dwelling#Ancestral Puebloans#Colorado#UNESCO World Heritage Site#ancestral puebloan archaeological site#archaeology#Montezuma County#original photography#desert varnish#travel#vacation#tourist attraction#landmark#architecture#landscape#countryside#summer 2022#USA#Mountain West Region#tree#cliff

218 notes

·

View notes

Text

So, I've once again remembered that all the lore I've gathered about the Ancestral Witches, their powers, theological influence and bloodlines is not canon and I'm currently making a doc filled with the Winx lore I've invented. Was just wondering if there would be any interest in lore dumps?? Thinking about posting a complete history of Andros and its evolution, especially because of the development of witchcraft as a response to harsh climates. This would then follow the creation of witch tribes that develop a system of agriculture, the formation of a mutually beneficial bond, the rise of prejudice against witches because of The Endless War, and then the fall of witchcraft. Is this something y'all would want??

#I mean I'm gonna do it anway#even if there isn't really an audience#I'm really invested in my own lore for witches and their place in the political landscape#but also their necessity to the health of planets#winxposting#winx club#winx trix#trix#andros#ancestral witches#the ancestral witches#tharma#winx tharma#tharma winx#winx ancestral witches

18 notes

·

View notes

Video

Chetro Ketl and a Setting in Chaco Canyon (Chaco Culture National Historical Park) by Mark Stevens Via Flickr: A setting looking to the southwest while taking in views and walking around the ruins present in the Chetro Ketl area of Chaco Culture National Historical Park.

#Ancestral Puebloans#Azimuth 135#Blocks#Blue Skies#Blue Skies with Clouds#Chaco Culture National Historical Park#Chaco Interior Wall#Chaco-San Juan Basin#Chacoan Culture#Chetro Ketl#Cliff#Cliff Face#Cliff Wall#Cliffs#Colorado Plateau#Day 2#Desert Landscape#Desert Mountain Landscape#Desert Plant Life#DxO PhotoLab 7 Edited#Intermountain West#Kiva#Landscape#Landscape - Scenery#Log and Stone Construction#Looking SW#Mesa#Nature#New Mexico and Mesa Verde National Park#Nikon D850

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

#doctor strange#Tilda Swinton#Ancestral#Chiwetel Ejiofor#Barón Mordo#hechicero supremo#Benedict Cumberbatch#stephen strange#imagen#photography#my photgraphy#cottagecore#artists on tumblr#radarplz#landscape#aesthetic#aestethic#travel#yörungede#popular#room#home#desing#reading#literature#pets#architecture#nature#books#books and libraries

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Taos Pueblo, NM

it was such a privilege being able to visit the Pueblo and immerse myself with the environment, the experience was worth the trip

#new mexico#pueblos indígenas#building#architecture#ancestral puebloans#traditional design#native american#landscape#photography#religious#culture#ancestors#nature#respect#sacred space#architecture photography#summer#june#beautiful#home#travel#road trip#business#my photgraphy

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

Quadrants, by Marcus Matawhero Lloyd

#Quadrants#Marcus Matawhero Lloyd#water is life#nature#landscape#fences#river#indigenous#reddit#album cover#album concept#4 elements#elements#earth#water#perfectly#planes#regions#river spirit#sacred landscape#ancestral#new zealand#Manganuku#wooden fence

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ancestral Landscapes - Unknown Dimensions

youtube

0 notes

Text

#the galisteo basin#ancestral puebloans#New Mexico#awanyu#adventure#travel#my photo#archaeology#southwest#desert#mountains#Ortiz mountains#photography#aesthetic#scenery#landscape#beauty

57 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wukoki.

#photographers on tumblr#ruins#landscape#Ancestral Pueblan People#Wupatki National Monument#Coconino County#Arizona

141 notes

·

View notes

Text

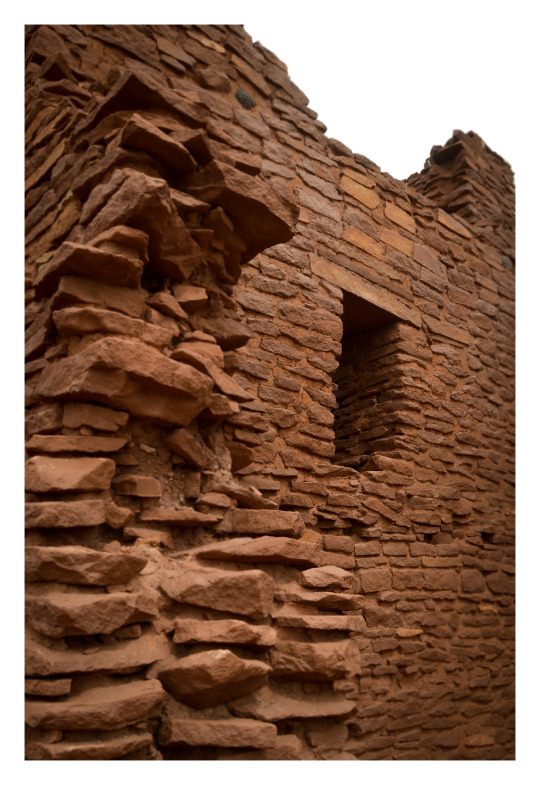

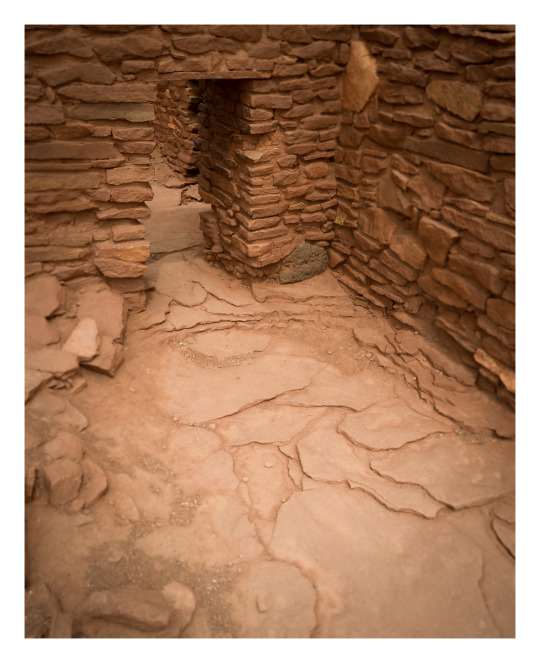

Ancestral Puebloan ruins built between 1200 and 1300.

Hovenweep National Monument, Utah

June 2018

#utah#Ancestral Puebloan#ruins#archaeology#archeology#architecture#native american#travel#original photography#photographers on tumblr#photography#lensblr#national park service#national park#landscape#landscape photography#wanderingjana

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

Forest (No. 82)

Mesa Verde National Park, CO

#Mesa Verde National Park#Montezuma County#USA#travel#original photography#vacation#tourist attraction#landmark#landscape#countryside#summer 2022#forest#woods#flora#nature#clouds#Colorado#Ancestral Puebloan#architecture#Native American history#US history#geology#archaeology#ruins#cliff

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

Some Thoughts on Ancestral Inheritance

I have long felt that one of the many signs of our collective cultural illness (and cultural orphanhood) in the contemporary West—particularly in North America—is that most of us have no sense of where we really come from. I don’t mean where we were born, of course, but what specific people-groups and landscapes we’re descended from. Generally speaking, Americans invest little to no interest in this sort of inquiry, and, in my view, are greatly diminished thereby.

I once heard the half-Scottish, half-Cherokee author and psychiatrist, Lewis Mehl-Madrona, refer to a way of introducing oneself to others that incorporates some detail about where one actually comes from as an ‘indigenous introduction’: a way that folks from most indigenous cultures around the world might be likely to introduce themselves, especially in a formal context—that is, by naming the people and communities they are descended from, and, with equal weight of importance, the Land(s) that their people hail from, where the bones of their ancient ancestors are buried and have merged with the soil for countless generations. This kind of ancestral memory was so important to my own Gaelic ancestors that in ancient times folks would frequently recite entire lineages of ancestry at public feasts and other important gatherings, often connecting individuals with certain divinized ancestors—sometimes human, sometimes not. This was seen as a way to express a healthful pride in one’s ancestry, and also in some cases to make a claim for why one should be listened to or accorded a place of trust, honor, or authority in the assembly.

In many indigenous cultures, the question of ‘authority’ is a crucial one. What, for instance, gives one authority to claim a certain title, or to pursue a vocational role that would significantly affect the lives of other people in the tribe, or of the communitas at large (i.e., of the human and other-than-human communities in a specific place)? Naturally, each culture answers this question differently, but as one example of how this kind of thing might be approached: in Diné culture, possessing some soil or stones (and/or other natural objects) from a certain sacred place in the landscape grants one the authority to speak with the spirits and ancestors in prayer: a crucial thing for all, without which life cannot proceed harmoniously. Likewise, in Diné, Hopi, and other Southwestern indigenous cultures it is considered a duty to be able to introduce oneself by naming the four clans one is most directly descended from (traced from the grandparents on both the maternal and paternal sides). Traditionally, whenever one introduces oneself to a new person or group of people, one offers the names of these four clans from which one has descended, so that the person or group right away knows something deeper about the one they’re relating with.

In any animistic worldview, knowing where on the Land one’s people are from is crucial, too, because it says something meaningful about the inheritance that person is carrying—not just from genetic and epigenetic memory, via the human (and possibly non-human) ancestors, but also from the living Land herself.

All this relates to the indispensable practice in more or less all animistic cultures of honoring the ancestors. In some cultures, ‘ancestors’ is a fairly broad category, but at very least it includes the human beings in our direct lineages of descent, all those because of whom we are who we are, here and now, in the present form in which we find ourselves.

It goes without saying that almost no one in our contemporary North American social environment asks about these kinds of things, and no one speaks this way when meeting others (in fact, to many people it would probably seem rude or outlandish to do so). In part this no doubt relates to the fact that very few of us are indigenous to this Land, and indigenous American cultures are tragically now a minority within the greater population. Most of us, in other words, are not descended from this Land, and nor were our ancestors—human or otherwise. Whether European, African, Asian, or anything else, our origins lie in another landscape, and many of us are unfortunately not in touch with that fact at all, or with the Land(s) we are actually descended from. (This certainly doesn’t mean that we can’t also feel profoundly connected to the American landscape; I certainly do—at least to certain parts of it. And it doesn’t mean that we shouldn’t also honor the Land we’re actually standing on, and engage with her and all her inhabitants relationally, wherever we happen to be. We should absolutely and unequivocally do so!)

I have sometimes introduced myself in a (broadly) indigenous way to students, for example at the beginning of a workshop or class that I’m teaching, but I almost never have the occasion to do so in general life when meeting new folks (unless those folks happen to be indigenous Americans), simply because it would seem bizarre and totally out of place in the minds of most Westerners for me to introduce myself in that manner. This is unfortunate, but it’s the plain reality. Notwithstanding, I’ve been thinking recently that perhaps I should attempt to do this kind of introduction a bit more frequently, and encourage others to do the necessary research and reflection that would allow them to do likewise, should they wish to.

In this spirit, I have decided to begin using the traditional spelling of my name more often, i.e., as it is rendered in my ancestral language of Gàidhlig (Scottish Gaelic). I will not do this everywhere (for instance in my published writing, only because at this point it would likely be unnecessarily confusing to people in that context), but I am beginning to do it in a host of other places where it seems to make sense, including here on the ‘inter-webs’.

So, this is how I would formally introduce myself in Gàidhlig—anns an Ghàidhlig (agus A’Chuimris):

An t-Athair Urramach Brèanainn Èilis Mac Uilleim, à Naomh Anna

Oighreachd shinnsireil: Mac Greumach à Lothian, Alba; Mac Glasain à Inbhir Nis, Alba; Ò Beòllàin à Slideach agus an Clàir, Connacht, Èirinn; Mac Uilleim à Monmouth, A’ Chuimrigh

Agus anns an t-A’Chuimris (and in Welsh): Y Parchedig Tad Brenhin Elisedd Ap Gwilym

This honors the clannan (‘clans’) from which I am directly descended, both matrilineally and patrilineally, in their original spellings in Gàidhlig, and names the ancestral Lands of each clann. It also gives my full name and religious title in Gàidhlig, and states where I was born (Naomh Anna: St. Anne). Oighreachd shinnsireil means literally, ‘ancestral inheritance’, or, ‘what is received from the ancestors’, and can refer to material inheritance, but also to lineages of descent. I like this double-valence of meaning because what we principally receive or ‘inherit’ from our ancestors is our particular shape of life in a given incarnation, derived to a meaningful degree from their epigenetic memories, their genetic tendencies, and a spiritual connection to the sacred Lands from which they hail. We also, of course, receive their names and stories. All this, it seems to me, is our true inheritance.

I can’t help but think that a completely different mindset and culture than what is normative today throughout the West would result from being taught (or learning) to think of oneself firstly in relation to who and where one comes from, rather than first and foremost imagining oneself as an isolated agent somehow moving through the world apart from all those threads of what I sometimes call the breacan a bhith (‘tartan/weaving of life/being’), which actually constitute a large portion of who we are in this lifetime.

I would say that to understand and honor this reality of interbeing reflects a broadly indigenous (and certainly an animistic) worldview: an interpretive lens of relationality, interdependence, and holism, rather than isolationism and consumption. And we could reasonably say that this relational way of thinking and being reflects an inherently anti-colonial worldview, because by its very nature it resists the reductionism, materialism, selfishness and egoic isolationism that modern Western thought and social practice have enforced on so many cultures the world over, not only to the destruction of the latter, but to the everlasting shame and interior erosion of the former.

If one wished to take this worldview a step further, one could begin to incorporate the notion that plants and animals and all living beings on this Earth are also in some meaningful sense our ancestors and our spiritual siblings. It is possible to engage deeply with these concepts and begin to integrate them, both ideationally and practically. (This is something I have explored at some length elsewhere, e.g., in my book, Seeds from the Wild Verge.)

A deeper and more life-giving way of seeing can indeed be learned, even if we were never taught to think in such a way when we were children. It is never too late to revisit the underlying, foundational assumptions in our minds and redress them in a way that might yield a more fruitful mode of thinking and moving in the world. Perhaps a mode in which our starting point for conceptualizing our lives and the world around us begins not with us as individuals, but with a collective, a commonage, a family of being from which our own lives have arisen and to which, by duty of honor, we owe an immense debt of gratitude.

It takes time and effort to do this work, but one can absolutely transmute their way of thinking about self and other, relationship to the Land and the ancestors and all other living things, into a vision that is holistic, realistic, and generative. It is my feeling and experience that, if one is truly open and desirous of this transmutation, no amount of corrosive, capitalistic, dominator ideology and past conditioning can prevent its unfoldment. That much, at least, I feel confident in definitively stating. And I think this is so because it is actually natural for us to relate to the world in a holistic and relational way; what is unnatural is the corrosive conditioning placed around our necks by the materialistic, self-focused, reductionistic, alienating dominator ideologies that have so thoroughly shaped our thoughts and actions for so long in the Western world.

And the process of liberating ourselves from all this can begin with some very simple things like learning to make an ‘indigenous introduction’, as described above, or going out into the natural world around where one lives—preferably alone and undistracted—to spend some time really getting to know the plant and animal species one shares that part of the world with, experiencing and reflecting on their different qualities and gifts of beauty, and on the ways in which they contribute to one’s own life and well-being, even though one ordinarily wouldn’t be aware of it.

These kinds of simple practices, if done with sincerity and intentionality, can be the beginning steps on a journey toward greater wholeness and the reclamation of our own ancestral inheritance—and, at some level, as Irish poet Seán Ó Ríordáin once put it, of ‘[our] own mind and [our] own true shape.’

Mòran beannachdan air an t-slighe (‘Many blessings on the way’),

An t-Athair Brèanainn

#brendanelliswilliams#spirituality#priest#reclamation#spiritualjourney#reflection#nature#ancestry#ancestral#ancestralwisdom#ancestors#gaelic#celtic#indigenous#inheritance#animism#religion#culture#scholar#poet#seer#theologian#colonialism#ecology#landscape#interbeing#wisdom#depth#transformation

3 notes

·

View notes