#African childhood

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

500 posts. "Best of".

WP tells me I’ve done 500 posts. Wow. I still remember, about 10 years ago, when I started blogging and didn’t have a clue. I still don’t have that many clues, but one thing’s for sure, the most important aspect is you, Dear Readers. No matter what one tries to post, it’s you who count. The talents you have. The human warmth… You make blogging worthwhile. All the bloggers I’ve met, on-line, or…

#Africa#African childhood#Creative fiction#indochina#Istanbul#montmartre#Penang#Short fiction#singapore

0 notes

Text

"Brazilian hand games and American hand games!!!! Realizing that the art of hand games comes from Africa! I never thought about it before. It was just embedded in our childhood."

"The collective consciousness is real"

"My goodness. We played this in Nigeria too."

There's a documentary with @jamilawoods called "Black Girls Play" about the history of handclap games in the US and their importance in the Black community. And a book before it called The Games Black Girls Play, by Kyra D. Gaunt.

#black culture#brazillian culture#black people#black is beautiful#music#africa#childhood#black history#black women#brazil#africans#african american#black american culture#black excellence#black lives matter#blacklivesmatter#handclap games#black films#documentary#books#books and reading

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

being african american>>> i love us ⟡♡

#african american#black is beautiful#black lives matter#90s#90s aesthetic#fashion#urban fashion#black core#black girl magic#black girls of tumblr#black girl aesthetic#childhood memories#childhood memory unlocked#girl blogging#love core#it girl#it girls#random thoughts#culture#my culture#beauty supplies#beauty supply store#hair wigs#vibes

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

A tour de force. Culling from a dazzling array of archival materials, Owens traces the beginning of modern American childhood. She carefully peels back the layers, revealing the prominent place of Black children in the construction of white manhood and American humanism... Weaving together theory and history, Like Children is rich, dynamic, timely, and moving.

#uwlibraries#history books#african american history#history of childhood#american history#19th century

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

Childhood bliss, eternal bliss. 😇

#Bronx#Zoo#Tree#Plants#Bronx Park#Nature Trek#African Plains#Childhood Memories#New York City#Bronx Zoo#New York

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

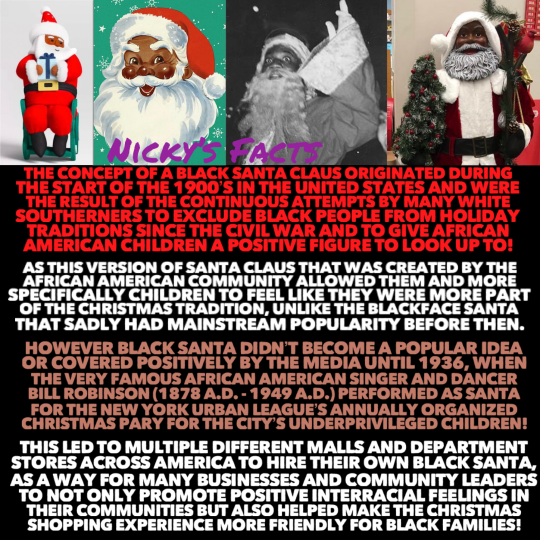

Black Santa Claus’s origin story!

❄️🎅🏾🎁

#history#happy holidays#black santa#united states#christmas#african american history#santa claus#bill robinson#holiday tradition#black christmas#christmas history#historical figures#black tumblr#role model#new york city#harlem#african american culture#childhood#black community#black excellence#soft black girls#christmas girl#holiday season#1900s#american history#christmas traditions#nickys facts

76 notes

·

View notes

Text

When I say I love r&b...THIS is what I'm talking about! 🔥🙌🏿🎤

#johnny gill#lady dujour#1990#music#black music#r&b#rhythm & blues#song#new edition#ballad#my childhood#90s#black culture#african american#vocals#talent#bring back begging ass r&b#video#sbrown82

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Who remembers this show?

#cousin skeeter#nickelodeon#teennick#sitcoms#90s#2000s#puppets#african american#family#nostalgia#childhood#retro

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

that north african dialect post is so funny. the assumption is that north africans would be able to understand the algerian guy and other arabic speakers wouldn't meanwhile north africans in the notes have no fucking clue what that man is saying

#the only reason i can understand him is because one of my childhood friends was algerian so i picked up a bit of the dialect#tbf i think tunis/morocco/algeria have much closer dialects to each other compared to other north africans#im not surprised that egyptians and libyans have no idea what he's saying😭

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

#my favorite book from childhood#it has the best illustrations and stories#personal#quotes#books & libraries#her stories#african folklore#folklore

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Another African Safari, 1969

“An African Childhood” Movie Previously on An African Childhood. We lived in East Africa from 1967 to 1971. One of the greatest kicks was to drive out in the Bush, on “safari”, a Swahili word that just means “trip”. We’d go to a National Park, and look for adventure and animals. On the previous movie, we went to Maasaï Mara, a unique game reserve in Kenya that connects with Serengeti, across the…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

African Town

By Charles Waters and Irene Latham

Category: Teen & Young Adult Fiction | Teen & Young Adult Historical Fiction

Chronicling the story of the last Africans brought illegally to America in 1860, African Town is a powerful and stunning novel-in-verse. In 1860, long after the United States outlawed the importation of enslaved laborers, 110 men, women and children from Benin and Nigeria were captured and brought to Mobile, Alabama aboard a ship called Clotilda. Their journey includes the savage Middle Passage and being hidden in the swamplands along the Alabama River before being secretly parceled out to various plantations, where they made desperate attempts to maintain both their culture and also fit into the place of captivity to which they’d been delivered. At the end of the Civil War, the survivors created a community for themselves they called African Town, which still exists to this day. Told in 14 distinct voices, including that of the ship that brought them to the American shores and the founder of African Town, this powerfully affecting historical novel-in-verse recreates a pivotal moment in US and world history, the impacts of which we still feel today.

#african culture#africa#world history#civil war#civil rights#MLK#us#nigeria#BENIN#slavery#black history#story#childhood#children books#illustrative art#illlustration#imperialism#black lives matter#artwork#holocaust#Auschwitz#freedom#free gaza#فلسطين#تمبلر#united nations#UNRWA#FUNNY#ART#artist

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

on the subject of museums though: I'm a FIRM believer that the smithsonians are genuinely some the greatest cultural heritage americans possess and I believe SO fervently in them being free to the public and accessible to all because they ARE our nation's history and tell (and ideally deconstruct) our national myths and help contextualize the natural world around us and show us the heights of human ingenuity and art. also my favorite of all of them is the national museum of the american indian and I personally think if you can only go to one smithsonian museum it should be that one

#I've only been to DC once since the National Museum of African American History and Culture opened and I wasn't able to go bc the#timed tickets for the day were all sold out :( but I'm going to attempt to go later this year#idk I feel very passionately about the smithsonians... one of my favorite childhood memories is the family trip we took there#and I walked around the natural history museum with a notebook and wrote down all my favorite things I saw that day ahaha#and the air & space museum really is just incredible. my dad has Space Race Boomer Brain but I was always really interested#in how his mind was so CAPTURED by the space race and by space exploration and him seeing the first man on the moon#and that bled into me appreciating that museum a lot#but seriously the american indian museum is just a feat to behold. just incredible.#and — I'd argue — the MOST important museum to view if you wanted to truly grasp the weight of the stories our country tries to tell itself

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bruce W. Smith’s Bébé’s Kids wasn’t just a movie—it was a cultural moment that broke new ground in the world of animation. When Bébé’s Kids hit theaters in 1992, it marked the first time an animated feature film was directed by an African American. That man was Bruce W. Smith, a visionary who brought the hilarious, unapologetically Black comedy of Robin Harris to life on screen.

At its core, Bébé’s Kids is a funny, relatable, and wild adventure that spoke directly to Black audiences. It gave us characters who felt real—people we knew from our own lives—and blended that with humor and heart. But what made this film truly special wasn’t just the jokes or the unforgettable lines. It was the fact that Bruce W. Smith, a Black man in an industry that had often shut out diverse voices, was behind it all.

For Bruce, Bébé’s Kids was more than just a film—it was about representation. It was about telling our stories through animation, a medium where Black voices had rarely been heard, let alone celebrated. With this film, Bruce didn’t just entertain; he showed Hollywood that Black creators belonged in every space, including animation.

After Bébé’s Kids, Bruce W. Smith went on to create The Proud Family and work on iconic films like The Princess and the Frog. But it all started with Bébé’s Kids, a movie that dared to be different, dared to be bold, and dared to be Black in a way animation had never seen before.

So as we celebrate Bébé’s Kids today, let’s also give credit to the man behind it—Bruce W. Smith—a trailblazer who changed the game and opened doors for future generations of Black animators and storytellers.

#bruce w. smith#bebe's kids#visionary#robin harris#my favorite movie#childhood#very funny#read about him#african american history#black history month#reading is fundamental#knowledge is power

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bronx Zoo’s Nature Trek ⛓️⛓️🦍

#Nature Trek#Bronx#Zoo#Bridge#Lake#Pond#African Plains#Bronx Zoo#Bronx Park#Childhood Memories#New York City#New York

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

My childhood can be measured easily, in pools of light spilling onto

pages and books blanketing the surfaces of our house in Aba. When

the electricity died, as it often did, I read by candlelight or with a torchlight

balanced against my body. Both my parents had been heavy readers; they

dragged their libraries into their marriage and kept them separate, distinct,

as if they both knew their relationship would end. My father had a

collection of Reader’s Digest condensed novels on the top shelf of the

bookcase in my brother’s room. In one of them, a little boy called his sister

stupid because she was seven years old. I took it personally when I first

read it, bristling with rage, because I was seven, too. That didn’t mean we

were stupid.

When my parents discovered I’d started reading the sex-advice columns

in my mother’s magazines as a child because I had run out of material, they

quickly bought me more books. Stories became my entire world, unchecked

and unrestricted; I was nine when I read V. C. Andrews’s Flowers in the

Attic, which I think is entirely too young for a child as lonely as I was. My

sister and I rummaged through my mother’s trunk, a steel tomb tucked in a

corner of the house, and we found a copy of Daphne du Maurier’s Rebecca,

with that haunting first line: “Last night I dreamt I went to Manderley

again.” My father’s library had a copy of Ken Follett’s book The Key to

Rebecca, which I’d read before, and eleven-year-old me was in awe at

finding a book that I’d first read about inside another book; worlds eating

worlds, all made by words.

By the time I started college in the States, I’d read every book in my

childhood home. The white dean of my school kept introducing me as the

sixteen-year-old freshman from West Africa who’d already read Dickens

and Tolstoy and Dostoevsky, as if any of that was surprising or special. I’d

only read those books because they were there; the awe associated with a

certain European literary canon wasn’t relevant. I’d also read Cyprian

Ekwensi, Ayi Kwei Armah, Buchi Emecheta, Chinua Achebe, the secret

copy of The Joy of Sex hidden away in my parents’ room, every

encyclopedia entry in my school library on Greek mythology, labels on

shampoo bottles, the sides of cornflakes boxes and Bournvita tins during

breakfast, countless contraband Harlequin and Mills & Boon romance

novels bartered with secondary-school classmates, narrative interludes in

my brother’s video games, and all the parts of the Bible that referenced sex.

It wasn’t until much later that I realized that there was a canon I was

expected to prioritize, especially if I wanted to consider myself a writer, that

the work of dead white men could be a type of currency.

Akwaeke Emezi, Dear Senthuran, A Black Spirit Memoir

#reading#books#akwaeke emezi#childhood#white writers#canon#writers of color#african writers#norms#publishing world#q

3 notes

·

View notes