#Abolition for the People

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

BY BREE NEWSOME BASS

BLACK COPS DON’T MAKE POLICING ANY LESS ANTI-BLACK

The idea that we can resolve racism by integrating a fundamentally anti-Black institution in the U.S. is the most absurd notion of all

This article is part of Abolition for the People, a series brought to you by a partnership between Kaepernick Publishing and LEVEL, a Medium publication for and about the lives of Black and Brown men. The series, which comprises 30 essays and conversations over four weeks, points to the crucial conclusion that policing and prisons are not solutions for the issues and people the state deems social problems — and calls for a future that puts justice and the needs of the community first.

Amid recent growing calls for defunding police this summer, a set of billboards appeared in Dallas, Atlanta, and New York City. Each had the words “No Police, No Peace” printed in large, bold letters next to an image of a Black police officer. Funded by a conservative right-wing think tank, the billboards captured all the hallmarks of modern pro-policing propaganda. The jarring choice of language, a deliberate corruption of the protest chant “no justice, no peace,” follows a pattern we see frequently from proponents of the police state. Any word or phrase made popular by the modern movement is quickly co-opted and repurposed until it’s rendered virtually meaningless. But perhaps the most insidious aspect of modern pro-police propaganda is reflected in the choice to make the officer on the billboard the face of a Black man.

This is in keeping with a narrative pro-police advocates seek to push on a regular basis in mass media — that policing can’t be racist when there are Black officers on the force, and that the police force itself is an integral part of Black communities. When Freddie Gray died in police custody, police defenders quickly pointed out that three of the officers involved were Black, implying that racism couldn’t be a factor in a case where the offending officers were the same race as the victim.

When I scaled the flagpole at South Carolina’s capital in 2015 and lowered the Confederate flag, many noted that it was a Black officer who was tasked with raising the flag to the top of its pole again. When an incident of brutality brings a city to its brink, Black police chiefs are paraded to podiums and cameras to serve as the face of the United States’ racist police state and to symbolically restore a sense of order. One of the most frequent recommendations from police reformists is to recruit and promote more Black officers. This is based on an argument that the primary problem with policing centers on a “breakdown of trust” between police forces and communities they have terrorized for decades; the solution, then, is to “restore trust” between the two parties by recruiting officers who resemble the communities they police. Images of police officers dancing or playing basketball with Black children in economically deprived neighborhoods are often published as local news items to help drive this narrative home. The idea gained traction in the aftermath of numerous urban rebellions in the 1960s and has seen a resurgence in the wake of the 2014 Ferguson uprising.

When protests broke out in Atlanta this past summer in response to the killings of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and Ahmaud Arbery, the city’s Black mayor, Keisha Lance Bottoms, held a press conference flanked by some of Atlanta’s most famous and wealthy Black residents. Together they pleaded for protestors to go home and leave property alone. Soon after, Rayshard Brooks was killed by white police officers in Atlanta. The moment exposed a class divide that exists in cities all over the nation: A chasm between the image of Black affluence promoted by Black politicians and the Black petite bourgeoisie (middle class) and the lived realities of the majority of Black residents in those cities, many of whom still face disproportionate unemployment, displacement by rapid gentrification, and policies that cater to white corporate interests. If the solution to racism were simply a matter of a few select Black people gaining entry to anti-Black institutions, we would see different outcomes than what we’re witnessing now. But the idea that we can resolve racism by integrating what is perhaps the most fundamentally anti-Black institution in the U.S. — its policing and prison industry — is the most absurd notion of all.

Part of the reason why calls to defund police have sent such shock waves through the nation, prompting placement of pro-police billboards and pushback from figures of the Black establishment, is because it cuts right to the heart of how structural racism operates in the United States. At a time when the Black elite would prefer to measure progress by their own tokenized positions of power and symbolic gestures like murals, the push to defund police would require direct confrontation with how the white supremacist system has been organized since the end of chattel slavery — when the prisons replaced plantations as the primary tool of racial control. Actions that may have been widely seen as adequate responses to injustice just a couple of decades ago now ring hollow to many observers who see that Black people continue to be killed by a system that remains largely unchanged.

Police forces represent some of the oldest white fraternal organizations in the United States. The rules of who is empowered to police and who is subject to policing are fundamental to the organization of the racial caste system. Even in the earliest days of integrating police forces, Black officers were often told they couldn’t arrest white people. The integration of police forces does nothing to alter their basic function as the primary enforcers of structural racism on a daily basis, and the presence of Black officers only serves as an attempt to mask this fact.

Police forces in America began as slave patrols, and their primary function has always been to act in service of the white ownership class and its capitalist production. In one century, that meant policing and controlling enslaved Black people, with the purview to use violence against free Black people as well; in another, it involved cracking down on organized labor, for the benefit of white capitalists. Receiving a badge and joining the force has been an entryway to white manhood for many European immigrants — providing them a sense of citizenship and superiority when they would have traditionally been part of the peasantry rather than the white owner class.

That spirit of white fraternity remains deeply entrenched in the culture of policing and its unions today, regardless of this new wave of Black police chiefs and media spokespeople. Police forces became unionized around the same time various other public employees sought collective bargaining rights — however, under capitalism, their role as maintainers of race-property relations remains the same. The most fundamental rule of race established under chattel slavery was that Black people were the equivalent of white property (if not counted as less than property). This relationship between race and property is most overt during periods of open rebellion against the police state, where officers are deployed to use lethal force in the interest of protecting inanimate property. We see swifter and harsher punishments handed out to those who vandalize police cars than to police who assault and kill Black people. (This is a major reason why the press conference in Atlanta with T.I. and Killer Mike struck people as classist and out of touch with the majority Black experience.)

This same pattern extends throughout the carceral state. Roughly a quarter of all bailiffs, correctional officers, and jailers are Black, yet there’s no indication that diversifying the staff of a racist institution results in less violence and death for those who are held within it. That’s because the institution continues to operate as designed. It is not “broken,” as reformists are fond of saying. The fallacy is in believing the function of police and prisons is to mete out punishment and justice in an equitable manner and not to first and foremost serve as a means of maintaining the race, gender, and class hierarchy of an oppressive society.

Believing that the system is “broken” rather than functioning exactly as intended requires a certain adherence to white supremacist and anti-Black beliefs. One has to ignore the rampant amount of violence, fraud, and theft being committed by some of the most powerful figures in society with little to no legal consequence while massive amounts of resources are devoted to the hyper-policing of the poor for infractions as minor as trespassing, shoplifting, and turnstile jumping at subway stations.

The Trump era has provided some of the starkest examples of this dynamic. The most powerful person in the nation and his associates have been able to break the law and violate the Constitution — including documented crimes against humanity — in full view of the public while he proclaims himself the upholder of law and order. Wealthy celebrities involved in the college admissions bribery scandal have gotten away with a slap on the wrist for orchestrating a multimillion-dollar scheme while a dozen NYPD officers surrounded a Black teenager, guns drawn, for the “crime” of failing to pay $2.75 for a subway ride.

The propaganda that depicts this type of policing as being essential to public safety and order is fundamentally classist and anti-Black. It traces its roots to the Black Codes that were passed immediately after the Civil War to control the movements of newly freed Black people. It relies on the racist assumption that Black people would run amok and pose a threat to the larger society if not kept under the constant surveillance of a police force that has authority to kill them if deemed necessary, and with virtual impunity. That’s why we are inundated with a narrative that depicts the police officer who regularly patrols predominantly Black communities as being an essential part of maintaining order in society.

One of the primary talking points against calls to defund and abolish police is that Black communities would have no way to maintain peace and order, and that a state of chaos would ensue. In wealthier neighborhoods, if an officer is present at all, they’re most likely positioned by a gate at the top of the neighborhood to monitor who enters. Meanwhile, the officer assigned to the predominantly Black community is there to keep a watchful eye on the residents themselves, and to ensure they are contained in their designated place within the larger city or town.

The current political divide on this issue falls exactly along these lines, separating those who think the system is simply in need of reform and those who correctly define the problem as the system itself. The reality is that Black people fall on both sides of this divide, which is why we find so many Black officers in uniform arguing for a reformist agenda even as every reform they propose is vociferously opposed by the powerful, majority-white police unions and most of the rank and file. Reformists remain committed to preserving the existing system even though the idea of reforming it to be the opposite of what it was designed to be is an unproven theory that’s no more realistic than the idea of abolishing police altogether.

The most pressing question remains: Why are we seeking to integrate and reform modern manifestations of the slave patrols and plantations in the first place? In Mississippi and Louisiana, state penitentiaries are converted plantations. What is a reformed plantation — and what is its purpose?

We must remember that many of these so-called “reforms” are not new. For as long as the plantation and chattel slavery systems existed, there also existed Black slaveowners, Black overseers, and Black slave catchers who participated in and profited from the daily operations of white supremacy. The presence of these few Black people in elevated positions of power did nothing to change the material conditions of the millions of enslaved people back then. And it makes no greater amount of sense to believe they indicate a shift in material conditions for Black people now.

#us politics#news#op eds#medium#level#Abolition for the People#Bree Newsome Bass#2020#end systemic racism#institutional racism#racism#racists#criminal justice reform#criminal justice system#defund the police#abolish the police#slavery didn’t get abolished it just got modernised#american slavery#american civil war#black codes#stop police brutality#police brutality#2020 protests

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

just a friendly reminder that, just because slavery was formally "abolished" in the so-called united states* in 1865, enslavement itself is still ongoing in the form of incarceration, which disproportionately affects Black and Indigenous people

(*i say "so-called" because the US is a settler-colonial construction founded on greed, extraction, and white supremacy) recommended readings/resources:

The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness by Michelle Alexander

"How the 13th Amendment Kept Slavery Alive: Perspectives From the Prison Where Slavery Never Ended" by Daniele Selby

"So You're Thinking About Becoming an Abolitionist" by Mariame Kaba

"The Case for Prison Abolition: Ruth Wilson Gilmore on COVID-19, Racial Capitalism & Decarceration" from Democracy Now! [VIDEO]

#i know most of u probably followed me for fandom stuff but abolition and decolonization and sex workers' rights are so close to my heart#normally i'd post this on my academia blog but i have more followers here so. here ya go#enslavement is still ongoing in SO many other ways and it disproportionately targets BIPOC and disabled and impoverished people#might make another post about that#prison abolition#abolition#racial justice#juneteenth#social justice#human rights#resources#police abolition#decolonization#michelle alexander#mariame kaba#ruth wilson gilmore#13th amendment#antiracism

9K notes

·

View notes

Text

last year i started trying to write an article where i documented every reported instance of psych abuse that happened in 2023 that i could find and had to stop halfway through because it was so fucking horrific. and that was only the shit that had been reported, that i could find in databases and in local news articles. the numbers and stories of psych abuse were staggering and what was worse is that i knew it was only a fraction of the actual abuse that happened that year, and that the actual number was so much worse. And even in just that fraction of news articles, in the half the states I searched for: there were dozens of deaths. Over a hundred different reported instances of rape. Over 300 different reported instances of illegal use of restraint and seclusion.

And i just keep thinking, over and over again, about how that is just a fraction of the reality. It is almost impossible to report psych abuse as it's happening when you're locked up in a psych facility where you don't have independent access to a phone, you can get cut off from your friends and family, and your access to a "grievance and reporting process" depends entirely on the same people who are abusing you. Even after you get out, there are so many barriers. It is very, very difficult to get anyone to believe you as a credible witness once you get certain things written in your chart. Psych staff can point to your diagnoses, their documentation, and say a million fucking things to get away with abuse.

and sometimes it feels like no one gives a shit besides other psych survivors, other mad/mentally ill/neurodivergent/disabled people. this is the same shit that happened in asylums, that happened in the "reformed" institutions of the 50s, that happened in group homes, that happens in psych wards, that happens in residential treatment. it hasn't fucked changed--it's just gotten new names, hiding behind the labels of "evidence based care" and "least restrictive alternative." when i really start to think about it, i get so fucking angry and full of grief for everyone i love who is still fucking locked up in these places. it just cements my determination to never shut up about this because we need to look out for each other and take care of each other, and i do not take my freedom to even be out here and advocating for granted.

#personal#psych abolition#antipsych#survivingpsych#mad liberation#psych abuse tw#this shit makes me so mad.#and forever and always what is at the core of that rage is so much fucking love for so many people who deserve#much better. than to be discarded to a cruel system

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

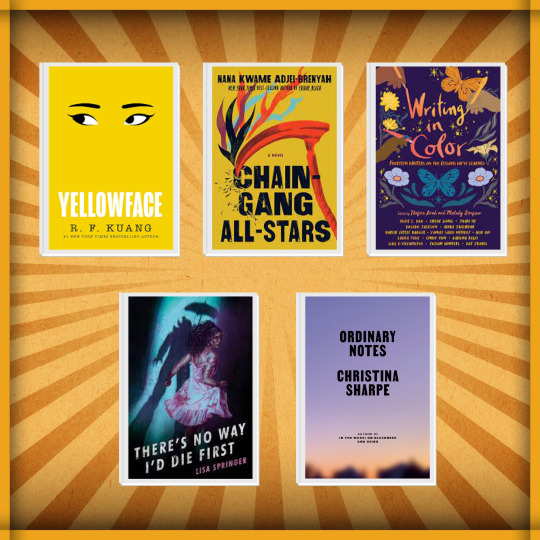

Top Anticipated Book Releases of 2023

Happy World Book Day! To celebrate, I'm bringing you my most anticipated book releases coming in 2023. Check 'em out. Save 'em on Goodreads. Absorb them with your eyeball meat. Etc, etc.

There’s so many amazing books coming out in 2023, so I figured I’d share a list of my most anticipated upcoming book releases of 2023 that I recommend you check out and maybe absorb with your pretty brain meats. Please Note: I have the attention span of a wet noodle, so the books on this list will consist of some very different genres. Also Note: I adore anthologies/collections, so this list…

View On WordPress

#2023 book releases#abolition for the people#anticipated books#book publishing#book releases#books#fantasy#nana kwame adjei-brenyah#new books#novels#publishing#publishing industry#r.f. kuang#sci-fi#science fiction#scifi#upcoming book releases#upcoming books

1 note

·

View note

Text

disturbed by the number of times i've seen the idea that calling gaza an open-air prison is not okay because "that implies that gazans have done something wrong", the subtext being unlike those criminals who deserve to be in prison. i'm sorry but we HAVE to understand criminalization and incarceration as an intrinsic part of settler colonialism and racial capitalism, because settler states make laws that actively are designed to suppress indigenous and racialized resistance, and then enforce those laws in even more racist and discriminatory ways so that who is considered "criminal" is indelibly tied up with who is considered a "threat" to the settler state. that's how law, policing, and incarceration function worlwide, and how they have always functioned in israel as part of the zionist project.

talking about prison abolition in this context is not a distraction from what's happening to palestinians; it's a key tool of israel's apartheid and genocide. why do you think a major hamas demand has been for israel to release the palestinians in israeli prisons? why do you think israel nearly doubled the number of palestinians incarcerated in their prison in just the first two weeks after october 7? why do they systematically racially profile palestinians (particularly afro-palestinians, since anti-blackness is baked into israel's carceral system as well, like it is in much of the world) and arrest and charge 20% of palestinians, an astonishingly high rate that goes up even higher to 40% for palestinian men? why are there two different systems of law for palestinians and israelis, where palestinians are charged and tried under military law, leading to a conviction rate of almost 100%? why do they torture children and incarcerate them for up to 20 years just for throwing rocks? why can palestinians be imprisoned by israel without even being charged or tried? why do they keep the bodies of palestinians who have died in prison (often due to torture, execution, or medical neglect) for the rest of their sentences instead of returning them to their families?

this is not to say that no palestinians imprisoned by israel have ever done harm. but incarceration worldwide has never been about accountability for those who have done harm, nor about real justice for those have experienced harm, nor about deterring future harm. incarceration is about controlling, suppressing, and exterminating oppressed people. sometimes people from privileged classes get caught up in carceral systems as well, but it is a side effect, because the settler colonialist state will happily sacrifice some of its settlers for its larger goal.

so yes, gaza is an open-air prison. that doesn't means gazans deserve to be there. it means that no one deserves to be in prison, because prisons themselves are inherently oppressive.

#free palestine#prison abolition#abolition#settler colonialism#racial capitalism#police abolition#fyi if people have seen my other post about palestinians incarcerated by israel this one doesn't have anything new i'm just upset#also while we're at it can we get rid of the term “political prisoner”#who gets imprisoned and who doesn't is always political

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

Calling Lesbians' attraction to vaginas a mere genital "preference" erases the sheer violence behind corrective rape of millions of sapphic women. I do not just "dislike" dick, I am physically incapable of being attracted to it. My allure to the female genitilia is not a choice, it's my biological reality. Dismissal of same-sex attraction as a choice reinforces the homophobic ideology that attractions can be altered and also paves the way for discrimination. One cannot opt out of their sexuality, they are always born with it.

#I am physically repulsed by dicks#And the reason is because i am a Lesbian#Not because i have some sort of trauma or discriminative bone or whatever bs tras say#Tras calling homosexuality a choice is what peaked me tbh#The only reason i supported trans people was because i was friends with great tifs lol#And with a LOT of tirfs on edtwt#Im greatful to them for introducing me to radical feminism but now im confused why would you be a tirf#No point in it#rad fem#radblr#radical feminism#terfsafe#radical feminists do interact#radical feminists do touch#trans exclusionary radical feminist#radical feminist safe#female seperatism#women are the superior sex#terfblr#terfism#terf#gender critical#gender abolition#sex not gender#sapphic#wlw#Lesbian#wlw post#lesbianism#anti trans

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

btw your homophobic republican grandma is not a radfem. no, the conservative woman talking about “womanly brain” & being explicitly anti-abortion isn’t a radfem, either. no… the spiritual woman telling young girls to “return to their divine feminine” & selling out cheap dating instructions & “tips” & promoting the idea of “female-specific” emotions, thoughts, and feelings, most likely isn’t a radfem. your radical christian mom that disowned you for being trans isn’t a radfem. please. PLEASE LEARN what radical feminism is. i am BEGGING you.

#these people are insane#like no you cannot use the woman you saw promoting otherwise extremely misogynistic rhetoric & saying mean things about trans people#as a “gotcha” against radfems#because that is NOT a radfem#conservative women calling themselves gender critical & co-opting our terms is a worthy thing to talk about#but they aren’t some “magical proof” of all radfems = bad#because they don’t know fuckshit about radfeminism#women who use our terms & call themselves feminists only when they get to shit on innocent trans people#are despicable and do not belong in our spaces#they aren’t radfems#radical feminism#gender abolition#gender critical#radblr

518 notes

·

View notes

Text

I’ll never forget when I was arguing with a person in favor of total prison abolition and I asked them “what about violent offenders?” And they said “Well, in a world where prisons have been abolished, we’ll have leveled the playing field and everyone will have their basic needs met, and crime won’t be as much of an issue.” And then I was like “okay. But…no. Because rich people also rape and murder, so it isn’t just a poor person thing. So what will we do about that?” And I don’t think they answered me after that. I’m ashamed to say I continued to think that the problem was that I simply didn’t understand prison abolitionists enough and that their point was right in front of me, and it would click once I finally let myself understand it. It took me a long time to realize that if something is going to make sense, it needs to make sense. If you want to turn theory into Praxis (I’m using that word right don’t correct me I’ll vomit) everyone needs to be on board, which mean it all needs to click and it needs to click fast and fucking clear. You need to turn a complex idea into something both digestible and flexible enough to be expanded upon. Every time I ask a prison abolitionist what they actually intend to do about violent crime, I get directed to a summer reading list and a BreadTuber. It’s like a sleight-of-hand trick. Where’s the answer to my question. There it is. No wait, there it is. It’s under this cup. No it isn’t. “There’s theory that can explain this better than I can.” As if most theory isn’t just a collection of essays meant to be absorbed and discussed by academics, not the average skeptic. “Read this book.” And the book won’t even answer the question. The book tells you to go ask someone else. “Oh, watch this so-and-so, she totally explains it better than me.” Why can’t you explain it at all? Why did you even bring it up if you were going to point me to someone else to give me the basics that you should probably already know? Maybe I’m just one of those crazy people who thinks that some people need to be kept away from the public for everyone’s good. Maybe that just makes me insane. Maybe not believing that pervasive systemic misogyny could be solved with a UBI and a prayer circle makes me a bad guy. But it’s not like women’s safety is a priority anyway. It’s not like there is an objective claim to be made that re-releasing violent offenders or simply not locking them up is deadly.

#I’m sorry#there are just people out here who need punishment and to be contained and rehabilitation will not work#like I’m one of the more insane people who thinks that you can rehabilitate anyone if they want to change and learn from their behavior#ANYONE#but there are people out here who do not and will not ever want it#and those people shouldn’t get a pass because you read incomplete abolitionist theory once#and now you think that a UBI would solve everything#that’s the thing about most abolitionists that I’ve noticed#once you press them on the hard shit#they go#well there are some good books on the subject#there are some other creators#okay#and what have those other books and creators said?#Tee Noir once started off a video telling people not to ask her to defend her defense of prison abolition#they should just ‘Google it’ she said (or something like that)#now I don’t watch Tee Noir#gothra#feminism#social justice#prison abolition#criminal justice#prison reform#tw vomit

922 notes

·

View notes

Text

All the jokes about Ken and horses are good but I just wanna say it's such a good parallel to how actual young men get swept into misogyny and the patriarchy.

Like they're told to believe it means men get to be cool and manly and have this power but with that comes extremely rigid commands of what they can be as a man and a cycle of self hatred for never matching those gender roles perfectly. Patriarchy tells men that if they just do exactly what is expected of them, then they get all the "cool stuff" that comes with. That doesn't work though when there's only a small group that actually gets that power, but men will keep trying to fit into those roles in hopes that they can.

In the end there are no horses or the myth men are told, it's just endless cycles of self hatred and ingroup fighting.

#barbie#barbie movie#barbie spoilers#ig#ive got a lot more on how barbie looks at feminism and the patriarchy cause god they did it#not to say there isnt faults such as very little conversation about intersectionality#but i can also understand the impossible task of talking about EVERYTHING in one movie#not everyone will be happy and thats fine#anyway i think something barbie did really well is fight this battle of both wanting so deeply to love (romantically or not) men but also#not dismissing the fact its mens job to solve their problems themselves#that even if women need to be the front runners of breaking the patriarchy men cannot rely on them to solve their own problems completely#also just god im so glad this wasnt a girl boss slay movie#women deserve respect and love and life regardless of accomplishment#we should not have to be ceos and presidents and world problem solvers to gain equality#i can also understand if nonbinary people feel left out/disconnected from the movie#but as always gender abolition and acknowledging the gender binary (ie the one societially impossed) go hand and hand 👍#just incase cause idfk terfs dni the barbie movie is not for you#barbie literally states constantly that her gender has nothing to do with (non existent) genitals so f off

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Adorable Transgender Girl... She's soooo pretty!

#transgirl#trans community#transgender#trans#lgbtlove#trans pride#transgenderwoman#transfem#gay#gay yearning#so gay#lgbtqplus#lgbtqia#lgbtqia+#lgbtq positivity#lgbt nsft#gender abolition#lgbtq history#lgbtq community#lgbtq people#t4t#nsft t4t#ftm t4t#t4t yearning#mtf t4t#t4t lesbian#t4t nsft#t4t ns/fw#mtf nsft#t4t wlw

578 notes

·

View notes

Text

(U.S.) two people are being put to death this month

thomas creech in idaho and ivan cantu in taxes are both scheduled to be executed by the state on february 28, 2024. if you are so inclined, please sign these petitions asking for clemency for them.

#death penalty#death penalty action#petitions#capital punishment#prison abolition#if you signed all of the petitions in my previous post these were included in that but i think people get#overwhelmed by so many at once so i tried to break it up in hopes that's easier for people.

242 notes

·

View notes

Text

content note: this post talks about eugenics, incarceration and institutionalization, and violent ableism

tangent from that post because i didn't want to start writing an essay on someone else's post and this is about a conversation i had irl this month, not intended as a reply to that post. but i actually feel very complicated about the idea of whether or not we should be pushing for more "accessibility" in jails and prisons and psych wards and institutions. i put that word in quotes because i don't think there is ever a way that being incarcerated is actually accessible to our bodies and minds; it is a disabling experience on so many levels. i'm not going to list out all the reasons why on this post; i've made so many posts talking explicitly about the harms of institutionalization before and i don't want to do that again right now. Talila Lewis has given several interviews about ableism, incarceration, and disability that are really worth reading and go more in depth into what that violence looks like. Liat Ben Moshe has also given another interview about disability and incarceration that goes over many of the same topics. given that these places are intense sites of violence towards disabled people, it feels difficult for me to claim that they could ever truly be accessible in any meaningful sense of the word.

what's also true right now is that institutions and prisons are incredibly inaccessible for physically disabled people in particular. i've been arrested with a wheelchair, i've been institutionalized with a feeding tube on top of that as well, i've been held on medical floors for psych treatment before, and i know very well exactly how bad it is. i've watched myself and so many other physically disabled people almost die in these places because of sheer neglect. i have physically disabled neighbors who were killed in these places. it is so dangerous for physically disabled people who are locked up in these places, yet at the same time, often psych wards are so inaccessible that physically disabled people just can't even be admitted because wards refuse to take people with mobility aids, medical devices, specific types of medication or care needs, if you have some kinds of terminal illness, and on and on and on.

what's also true is that when these places are so inaccessible that many physically disabled people are excluded and unable to even access them in the first place, it doesn't mean that we then somehow access other types of care instead. it just means that we're also discarded and left to die. this also is a really similar dynamic for a ton of other marginalized groups that get excluded from psych care--many of my comrades who are people of color have also experienced this same type of denial of care. initially i think that can seem like a confusing contradiction--how is it that psych wards are locking up some people up against their will but refusing to take in other people? but when you start thinking about the underlying logic at the core of these systems, it makes sense.

psych wards operate under this idea that madness must be cured by any means possible, up to and including eradication. institutions are a way of disappearing madness from the world--hiding us away so that we don't disturb a sane society, and not letting us free again until we either die in there or are able to appear like we've sufficiently eradicated madness from our mind. preventing physically disabled people from accessing inpatient treatment is operating under the same assumptions--except that this particularly violent convergence of ableism is happy to just let us die, both because it eradicates madness from the world and because they view our lives as unworthy of living in the first place. eugenics is still alive and well in the united states and it's still fucking killing us; both inside institutions and outside of them.

i would never tell someone that they're privileged for getting institutionalized--i think that would be a cruel thing to say to someone who has just survived a lot of violent ableism. and at the same time, our current systems of mental health care are set up in a way where not being able to access inpatient care can be a deadly logistical nightmare. there are some partial hospitalization programs that have such a long waiting list that you can only really get in if you just got an urgent referral because you're getting discharged from inpatient care--how the fuck are physically disabled people supposed to access those programs? if you need meal support for your eating disorder 6 times a day and the only places that offer that are residential treatment in a house with stairs, what the fuck are you supposed to do? if noncarceral outpatient forms of treatment like therapy, support groups, PHP programs, peer support funding, etc etc etc are often prioritizing people who have recently been discharged from inpatient care, how are you supposed to access any type of mental health care at all? (to be clear i know that not all forms of outpatient care operate in this way, but a lot of state run/low cost programs that accept Medicaid/Medicare operate in that way, and i've seen it cause enough barriers that i know this is a very real problem.)

so when i think about what it would take to actually ensure that physically disabled people can access mental healthcare, there's a lot that comes up for me. on one hand, so much of my work is about tearing down institutions and ensuring that no one is forced into these places to face that type of violence. on the other hand, so many physically disabled people need care right now, and we have to figure out some way of making that happen given the current systems we have in place. i will never be okay with just discarding physically disabled people as collateral damage, and any world that we're building needs to be one that embraces disability from the beginning.

i keep thinking about the concept of non-reformist reforms that gets talked about a lot in the prison abolition movement. the idea behind non-reformist reforms is that usually, reforms work to reinforce the status quo. they're usually talked about in liberal language of "improvement" and "human rights", but when it comes down to it, they're still giving more power to harmful institutions and reinforcing state power. an example of a reformist reform is building a new jail that is bigger and has "nicer" services. or when the cops in my city tried to get funding for more wheelchair accessible cop vans. these are reformist reforms because when it comes down to it, it's still giving more money and legitimacy to the prison system and increasing the capacity to keep people locked up--even when people talk about it using language about welfare for prisoners, that's not actually what's happening. having more wheelchair accessible cop vans would be dangerous for the disabled people in my city--it's helped us out a LOT that it's so difficult for the cops to arrest multiple wheelchair users at once.

non-reformist reforms are the opposite of that--they're reforms that work to dismantle systems, redistribute power, and set the stage for more even more dramatic transformations. They're sort of an answer to the question of "what do we do right now if we can't go out and burn down all the prisons overnight?" Examples of a nonreformist reform are defunding prisons, getting rid of paid administrative leave for cops, shutting down old prisons and not building new ones, etc. they're steps we can take right now that don't fully abolish prisons, but still work to dismantle them, rather than making it easier for the system to keep going.

so, when we apply this to the psych system, what are some nonreformist reforms that could help make sure that all disabled people are having their needs met right now? Some ideas I'm having include fixing the problem of PHP/outpatient care requiring referrals from inpatient, increasing the amount of Medicaid/Medicare funding for outpatient mental health care, building physically accessible peer respites that allow caregivers to stay with you if needed, increasing SSI/SSDI to an actually liveable rate, creating more disability specific mental health resources, support groups, care webs, and a million other things we'd probably need to actually get our needs met. non-reformist reforms for people in psych wards right now might look like ensuring everyone has 24/7 access to phones and internet, ensuring that disabled people have access to mobility aids in these spaces, making sure that there's accessible nutrition for people with dietary restrictions and/or feeding tubes, and more.

when i see people saying that we need to ensure that psych wards or prisons are made accessible it makes me feel nervous. i worry that the changes required to do that wouldn't actually provide care to disabled people, i worry it would just make it easier for increasing numbers of disabled people to get locked up and harmed all while people claimed it was a success story of "inclusion." i worry that it would just continue to cement carceral treatment as the only option for existing as a disabled person, and that it would make it harder for us to live in our communities, with the services and adaptations we need. when i think about abolition, i'm always thinking about what can we do right now, what do disabled people who are incarcerated and institutionalized need right now, what can we do right now to ensure that everyone is surviving and getting their needs met. i'm not willing to ignore or discard my incarcerated disabled comrades in the moment because of my dreams for an abolitionist future, i'm always going to support our organizing in these places as we try to survive them.

overall i guess what i'm saying is that i think making inpatient psych care accessible would require dismantling and fundamentally destroying the whole system. I can't imagine a way of doing that within the current system that wouldn't just continue to harm disabled people. and that as a psych abolitionist i think that means we have a responsibility to each other right now to fight for that, to understand that physically disabled people not being able to access mental health care is an incredibly urgent need. I refuse to treat my MadDisabled comrades as disposable: our lives are valuable and worth fighting for.

i'm also going to link to the HEARD organization on this post. They're one of the few abolitionist organizations that does direct advocacy and support for deaf and disabled people in prisons. if you or one of your disabled community members ever gets incarcerated in jail/prison, they have a lot of resources. donate to support their work if you can.

#personal#psych abolition#survivingpsych#ableism#psych ward tw#eugenics tw#disability justice#antipsych#antipsychiatry#prison abolition#i just have a lot of thoughts about this all the time. it makes me so mad how often the answer to things is just#'we don't care if disabled people live or die.'#and how many systems are set up based on control. coercion. fear. instead of care

315 notes

·

View notes

Text

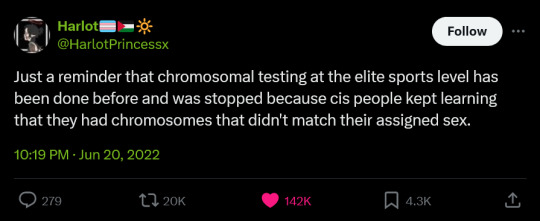

#lgbtqia#lgbt pride#lesbian#nonbinary#lgbtq community#queer#lgbtq#sapphic#nonbinary lesbian#gay girls#gender#gender ideology#gender critical#gender abolition#sex not gender#gender stuff#queer stuff#queerness#genderfluid#trans stuff#intersex#trans sports#trans woman#trans women are beautiful#trans women are valid#trans women are amazing#trans women positivity#trans joy#trans people#transblr

143 notes

·

View notes

Text

Genuine challenge (I've made a similar one before, but let's do it again):

If you talk about "mental health" in any context (wanting better mental health, something being bad for your mental health, etc.), describe what that means to you -- without using the words "health(y)," "well(ness)," "ill(ness)," "disorder," "trauma," "symptom," or the names of any DSM disorders, symptoms, or neurochemicals.

It's really hard. I'm struggling with it, because the psychiatric paradigm has so thoroughly colonized our language and vocabulary that it's hard to describe emotional experiences without it, without being overly vague and nondescriptive.

#anti psych#psych abolition#mad liberation#mad people are awesome#pop neuroscience#neurodiversity#mad pride

53 notes

·

View notes

Text

Legality ≠ morality

#abolition#abolitionist#acab1312#acab#abolish the police#abolish the state#abolish police#abolish ice#abolish prisons#abolish family policing#leftist theory#leftist#abolish landlords#abolish capitalism#abolish the supreme court#1312#human rights#incarcerated people#incarceration#cripple punk#cripplepunk#chronically couchbound#fuck 12

285 notes

·

View notes

Text

lots of talks on here about how "the left" and "leftists" are a bad, ignorant and hypocritical monolithic group from people who've never been a member of a leftist political party nor even talked to an actual leftist once in their life

#people acting surprised a communist party supports prostitution abolition#also no liberals don't count as leftists

26 notes

·

View notes