#black codes

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

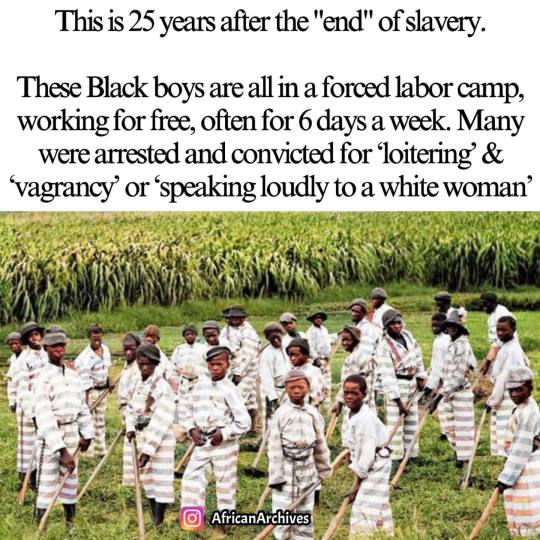

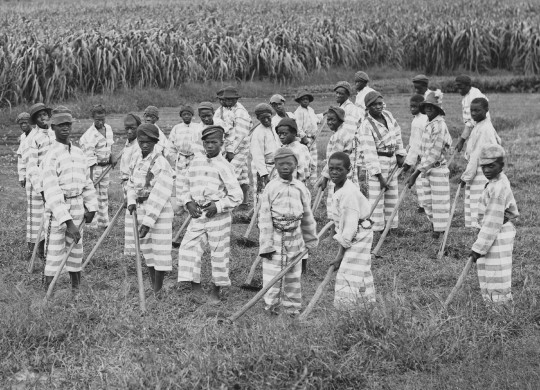

In 1865, enslaved people in Texas were notified by Union Civil War soldiers about the abolition of slavery. This was 2.5 years after the final Emancipation Proclamation which freed all enslaved Black Americans. But Slavery Continued… In 1866, a year after the amendment was ratified, Alabama, Texas, Louisiana, Arkansas, Georgia, Mississippi, Florida, Tennessee, and South Carolina began to lease out convicts for labor. This made the business of arresting black people very lucrative, thus hundreds of white men were hired by these states as police officers. Their primary responsibility being to search out and arrest black peoples who were in violation of ‘Black Codes’ Basically, black codes were a series of laws criminalizing legal activity for black people. Through the enforcement of these laws, they could be imprisoned. Once arrested, these men, women & children would be leased to plantations or they would be leased to work at coal mines, or railroad companies. The owners of these businesses would pay the state for every prisoner who worked for them; prison labor. It’s believed that after the passing of the 13th Amendment, more than 800,000 Black people were part of that system of re-enslavement through the prison system. The 13th Amendment declared that "Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction." Lawmakers used this phrase to make petty offenses crimes. When Blacks were found guilty of committing these crimes, they were imprisoned and then leased out to the same businesses that lost slaves after the passing of the 13th Amendment. The majority of White Southern farmers and business owners hated the 13th Amendment because it took away slave labor. As a way to appease them, the federal government turned a blind eye when southern states used this clause in the 13th Amendment to establish the Black Codes.

#slavery#emancipation proclamation#black americans#convict leasing#black codes#13th amendment#involuntary servitude#prison labor#re-enslavement#southern states#racial discrimination

976 notes

·

View notes

Text

t/w: death

👉🏿 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Slave_codes

#politics#robert brooks#blacklivesmatter#police#racism#modern day lynching#casual killing act#abolish prisons#nypd#prison#lynching#structural racism#systemic racism#systematic racism#anti blackness#black codes

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

NEVER FORGET. We are a people who have been terrorized for centuries.

Never Again

#we dont owe nodody NOTHING#black history#black people#black lives matter#blacklivesmatter#never forget#racial injustice#slavery#jim crow#cointelpro#civil rights movement#13th amendment#police brutality#mass incarceration#redlining#medical bias#alligator bait#school to prison pipeline#black codes#lynchings#housing discrimination#homestead act#rosewood#human zoo's#kkk#project 2025#maga#trump#alt right#tulsa race massacre

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

I guess this is what Trump means when he says "Make America Great Again," it's when segregation was loved by White Supremacists.

Photographer Gordon Parks

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Shocking Truth About Black Codes: How They Reinvented Slavery

youtube

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

B1

#black culture#black women#black people#black lives matter#blacklivesmatter#black excellence#quotes#black codes

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Schools do a poor job of teaching about America’s legacy of white supremacy, according to a scholar who researches racial discrimination.

A Ku Klux Klan parade in Washington, D.C., in 1926

When it comes to how deeply embedded racism is in American society, blacks and whites have sharply different views.

For instance, 70 percent of whites believe that individual discrimination is a bigger problem than discrimination built into the nation’s laws and institutions. Only 48 percent of blacks believe that is true.

Many blacks and whites also fail to see eye to eye regarding the use of blackface, which dominated the news cycle during the early part of 2019 due to a series of scandals that involve the highest elected leaders in Virginia, where I teach.

The donning of blackface happens throughout the country, particularly on college campuses. Recent polls indicate that 42 percent of white American adults either think blackface is acceptable or are uncertain as to whether it is.

One of the most recent blackface scandals has involved Virginia Gov. Ralph Northam, whose yearbook page from medical school features someone in blackface standing alongside another person dressed in a Ku Klux Klan robe. Northam has denied being either person. The more Northam has tried to defend his past actions, the clearer it has become to me how little he appears to know about fundamental aspects of American history, such as slavery. For instance, Northam referred to Virginia’s earliest slaves as “indentured servants”. His ignorance has led to greater scrutiny of how he managed to ascend to the highest leadership position in a racially diverse state with such a profound history of racism and white supremacy.

Ignorance is Pervasive

The reality is Gov. Northam is not alone. Most Americans are largely uninformed of our nation’s history of white supremacy and racial terror.

As a scholar who researches racial discrimination, I believe much of this ignorance is due to negligence in our education system. For example, a recent study found that only 8 percent of high school seniors knew that slavery was the central cause of the Civil War. There are ample opportunities to include much more about white supremacy, racial discrimination and racial violence into school curricula. Here are three things that I believe should be incorporated into all social studies curricula today:

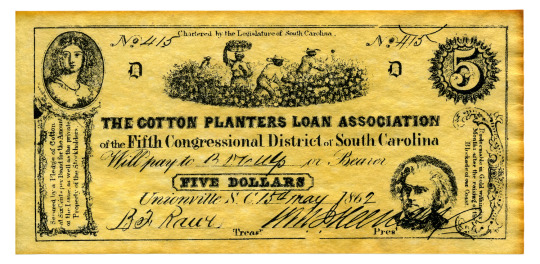

1. The Civil War was fought over slavery and one of its offshoots – the convict-lease system – did not end until the 1940s.

The Civil War was fought over the South’s desire to maintain the institution of slavery in order to continue to profit from it. It is not possible to separate the Confederacy from a pro-slavery agenda and curriculums across the nation must be clear about this fact.

A Confederate treasury note from the Civil War Era shows how reliant the South’s economy was on slave labor. Photo from Scott Rothstein / www.shutterstock.com.

After the end of the Civil War, southern whites sought to keep slavery through other means. Following a brief post-Civil War period known as Reconstruction, white southerners created new laws that gave them legal authority to arrest blacks over the most minor offenses, such as not being able to prove they had a job.

While imprisoned under these laws, blacks were then leased to corporations and farms where they were forced to work without pay under extremely harsh conditions. This “convict leasing” was, as many have argued, slavery by another name and it persisted until the 1940s.

Southern jails made money leasing convicts for forced labor in the Jim Crow South. Circa 1903. Photo from Everett Historical / www.shutterstock.com.

2. The Jim Crow era was violent.

While students may be taught about segregation and laws preventing blacks from voting, they often are not taught about the extreme violence whites enacted upon blacks throughout the Jim Crow era, which took place from 1877 through the 1950s. Mob violence and lynchings were frequent occurrences – and not just in the South – throughout the Jim Crow era.

Racial terror was used as a means for whites to maintain power and prevent blacks from gaining equality. Notably, many whites – not just white supremacist groups like the Klu Klux Klan – engaged in this violence. Moreover, the torture and murder of blacks was not associated with any consequences.

During this same time, white society created negative stereotypes about blacks as a way to dehumanize blacks and justify the violence whites enacted upon them. These negative stereotypes included that blacks were ignorant, lazy, cowardly, criminal and hypersexual.

Blackface minstrelsy refers to whites darkening their skin and dressing in tattered clothing to perform the negative stereotypes as part of entertainment. This imagery and entertainment served to solidify negative stereotypes about blacks in society. Many of these negative stereotypes persist today.

3. Racial inequality was preserved through housing discrimination and segregation.

During the early 1900s, a number of policies were put into place in our country’s most important institutions to further segregate and oppress blacks. For example, in the 1930s, the federal government, banks and the real estate industry worked together to prevent blacks from becoming homeowners and to create racially segregated neighborhoods.

This process, known as redlining, served to concentrate whites in middle-class suburbs and blacks in impoverished urban centers. Racial segregation in housing has consequences for everything from education to employment. Moreover, because public school funding relies so heavily on local taxes, housing segregation affects the quality of schools students attend.

All of this means that even after the removal of discriminatory housing policies and school segregation laws in the 1950s and 1960s, the consequences of this intentional segregation in housing persist in the form of highly segregated and unequal schools. All students should learn this history to ensure that they do not wrongly conclude that current racial disparities are based on individual shortcomings – or worse, black inferiority – as opposed to systematic oppression.

Americans live in a starkly unequal society where health and economic outcomes are largely influenced by race. We cannot begin to meaningfully address this inequality as a society if we do not properly understand its origins. The white supremacists responsible for sanitizing our history lessons understood this. Their intent was clearly to keep the country ignorant of its racist past in order to stymie racial equality. To change the tide, we must incorporate a more accurate depiction of our country’s racist history in our K-12 curricula.

#3 Things Schools Should Teach About America’s History of White Supremacy#white supremacy#american hate#american white supremacy#education#white lies#white history of hate#homegrown supremacy#systemic racism#convict leasing#13th amendment#vagrancy laws#racism in american systems#systemic oppression#Jim Crow#Jim Crow Laws#Black Codes

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

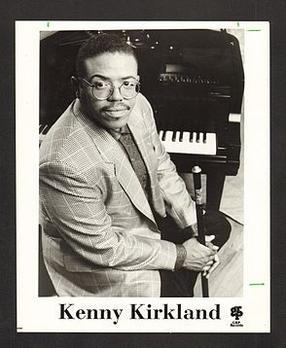

Kenny Kirkland: The Pianistic Prodigy of Modern Jazz

Introduction: In the realm of modern jazz, few pianists left as indelible a mark as Kenny Kirkland. A virtuoso with an uncanny ability to blend technical prowess with profound musicality, Kirkland’s contributions continue to resonate through the annals of jazz history. This article delves into this extraordinary musician’s life, music, and enduring legacy. Early Days: Kenny Kirkland was born…

View On WordPress

#Black Codes#Blue Turtles#Branford Marsalis#Bring on the Night#First Meeting#Hot House Flowers#Jazz History#Jazz Pianists#Kenny Kirkland#Michal Urbaniak#Miroslav Vitous#Miroslav Vitous Group#Police#Sting#The Dream of the Blue Turtles#Think of One#Wynton Marsalis

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

#lana del rey#girl interrupted#girlblog#girlblogging#hell is a teenage girl#lizzy grant#girlhood#manic pixie dream girl#im just a girl#coquette dollete#so me coded#alana champion#sofia coppola#coquette#dollette#i wanna be sk1nn1#i wanna be perfect#i need a lobotomy#nymph3t#girl blog#this is what makes us girls#manic pixie nightmare#pinterest#gaslight gatekeep girlblog#girl boss gaslight gatekeep#natalie portman#black swan#the virgin suicides#pink#gaslight gatekeep girlboss

9K notes

·

View notes

Text

#black codes#black women#workforce inequality#marginalized#racial inequality#racism#systemic racism#forced labor#economic inequality#historical injustice

628 notes

·

View notes

Text

Special Field Orders, No. 15 (series 1865) were military orders issued during the American Civil War, on January 16, 1865, by General William Tecumseh Sherman, commander of the Military Division of the Mississippi of the United States Army. They provided for the confiscation of 400,000 acres (160,000 ha) of land along the Atlantic coast of South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida and the dividing of it into parcels of not more than 40 acres (16 ha), on which were to be settled approximately 18,000 formerly enslaved families and other black people then living in the area.

The orders were issued following Sherman's March to the Sea. They were intended to address the immediate problem of dealing with the tens of thousands of black refugees who had joined Sherman's march in search of protection and sustenance, and “to assure the harmony of action in the area of operations.” Critics allege that his intention was for the order to be a temporary measure to address an immediate problem, and not to grant permanent ownership of the land to the freedmen, although most of the recipients assumed otherwise. General Sherman issued his orders four days after meeting with twenty local black ministers and lay leaders and with U.S. Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton in Savannah, Georgia. Brig. Gen. Rufus Saxton, an abolitionist from Massachusetts who had previously organized the recruitment of black soldiers for the Union Army, was put in charge of implementing the orders. Freedmen were settled in Georgia, particularly along the Savannah River, in the Ogeechee district of Chatham County, and on islands off of the coast of Savannah.

In the end, the orders had little concrete effect because President Andrew Johnson issued a proclamation that returned the lands to southern owners who took a loyalty oath. Johnson granted amnesty to most former Confederates and allowed the rebel states to elect new governments. These governments, which often included ex-Confederate officials, soon enacted black codes, measures designed to control and repress the recently freed slave population. General Saxton and his staff at the Charleston SC Freedmen Bureau's office refused to carry out President Johnson's wishes and denied all applications to have lands returned. In the end, Johnson and his allies removed General Saxton and his staff, but not before Congress was able to provide legislation to assist some families in keeping their lands.

Although mules are not mentioned in the orders, they were a main source for the expression “forty acres and a mule.” A historical marker commemorating the order was erected by the Georgia Historical Society in Savannah, near the corner of Harris and Bull streets, in Madison Square. (source)

👉🏿 40 Acres & A Lie (podcast)

#politics#slavery#reparations#black history#juneteenth#racism#40 acres and a mule#special field order 15#american history#civil war#reconstruction#40 acres and a lie#black codes

57 notes

·

View notes

Text

#amerikkka#America#united states#racism#immigrants#jobs#American jobs#slavery#incarceration#enslaved#incarcerated people#13th amendment#war on drugs#black codes#involuntary servitude#history#American history#critical race theory#convict leasing#prison system#ronald reagan#civil rights act#civil rights#real American history#accurate history#reality#racist#systemic racism#history lesson#learn something

0 notes

Text

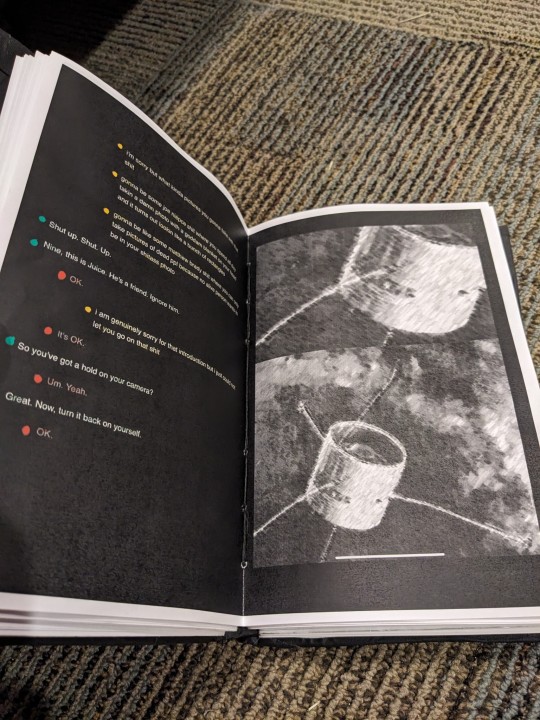

I'm like super normal and not unhinged in the slightest (I spent 3 days formatting, printing, and binding a niche internet story about sci fi football into a 280 page physical book)

#it's a little crusty around the edges but. i am not a professional i just like binding books#the colored dots are bc my printer is strictly black and white and i needed a way to differentiate text colors#so. posca pens.#all the videos are QR codes !!#17776#is there even a fandom for this i legitimately don't know#if there is i love y'all

24K notes

·

View notes

Text

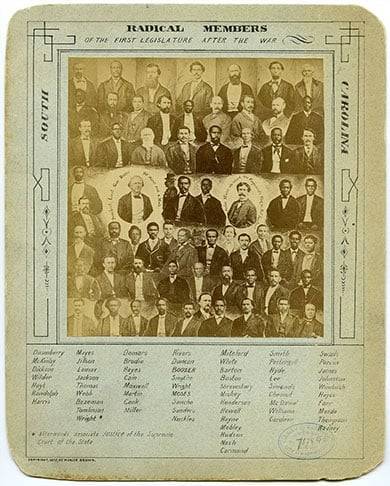

1865: Following the war, white South Carolinians rewrite the state constitution in order to return to the union.

They restrict the right to vote and elect an all-white legislature that then passes the “Black Codes,” which restrict rights of the newly freed people. Congress responds by passing the Reconstruction Acts, which require that the state rewrite the Constitution. African-Americans participated under federal military supervision.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

South Carolina Passes Negro Act of 1740, Codifying White Supremacy

On May 10, 1740, the South Carolina Assembly enacted the “Bill for the better ordering and governing of Negroes and other slaves in this province,” also known as the Negro Act of 1740. The law prohibited enslaved African people from growing their own food, learning to read, moving freely, assembling in groups, and earning money. It also authorized white enslavers to whip and kill enslaved Africans for being "rebellious."

South Carolina implemented this act after the unsuccessful Stono Rebellion in 1739, in which approximately 50 enslaved Black people resisted bondage and waged an uprising that killed between 20 and 25 white people. In addition to establishing a racial caste and property system in the colony, the assembly sought to prevent any additional rebellions by including provisions that mandated a ratio of one white person for every 10 enslaved people on a plantation. The Negro Act treated enslaved Africans as human chattel and revoked all forms of civil rights.

The law served as a model for other states; Georgia authorized slavery within its borders in 1750 and enacted its own slave code five years later. In 1865, the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment legally abolished slavery in the U.S. except as punishment for crime, but discriminatory Black Codes and Jim Crow laws developed to maintain the oppression of Black people, ensuring that the legacy of the Negro Act of 1740 and similar laws remained present throughout the country for more than two centuries.

#history#white history#Passes Negro Act of 1740#us history#May 10#black history#republicans#democrats#politics#us politics#law#us law#us laws#georgia#south carolina#1750#1865#Jim Crow#Black Codes#Negro Act of 1740

0 notes