#roman era inscription

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Roman-Era Inscription Found at Building Demolition Site in Bulgaria

A fragment of a marble slab with an inscription, believed to date from the time of Roman Emperor Septimius Severus, has been found at the site of a demolished house in Bulgaria’s city of Plovdiv.

Septimius Severus was Roman Emperor from 193 to 211 CE.

The find was made at the site of a house at 17 Metropolitan Panaret Street that had been demolished. The developer contacted the Regional Archaeological Museum in Plovdiv.

The fragment measures 70 x 40cm and was found at a depth of about 1.6 metres.

Archaeologist Dessislava Davidova told Bulgarian National Radio that over the centuries, the marble had been used as part of building material.

BNR reported that Dr Nikolai Sharankov, a specialist in classical languages and epigraphy, was consulted and said that the fragment was most likely part of an inscription on the pedestal of a statue dating from the time of Emperor Septimius Severus.

The inscription mentions the name of the distinguished citizen Veranius, tribune and high priest of the imperial cult in Philippopolis, an ancient name of Plovdiv in antiquity.

Sharankov said that Veranius most likely belonged to the local Thracian aristocracy, obtained Roman citizenship and was included in the Roman equestrian class and thus began his career in the Roman army and he reached the position of military tribune.

From the inscription it is understood that Veranius organised gladiator fights.

Sharankov said that the dating was done according to the specific font of the inscription, characteristic of the time of Emperor Septimius Severus.

#Roman-Era Inscription Found at Building Demolition Site in Bulgaria#Plovdiv Bulgaria#Roman Emperor Septimius Severus#marble#marble fragment#ancient artifacts#archeology#archeolgst#history#history news#ancient history#ancient culture#ancient civilizations#roman history#roman empire#roman art#ancient art

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

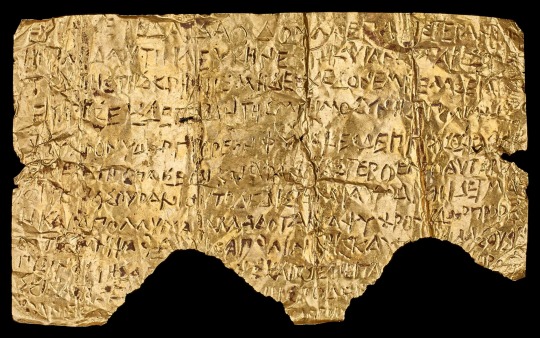

The Petelia Tablet, Greek, c.300-200 BCE: this totenpass (a "passport for the dead") was meant to be buried in a human grave; it bears an inscription that tells the dead person exactly where to go and what to say after crossing into the Greek Underworld

Made from a sheet of gold foil, this tablet measures just 4.5cm (a little over 1.5 inches) in length, and although it was found inside a pendant case in Petelia, Italy, it's believed to have originated in ancient Greece. It was meant to aid the dead in their journey through the Underworld -- providing them with specific instructions, conferring special privileges, and granting them access to the most coveted realms within the afterlife.

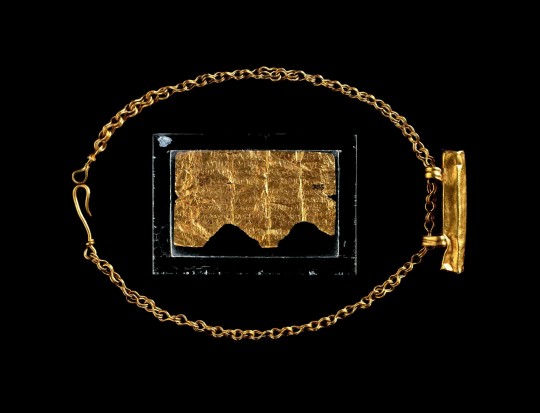

The Petelia tablet, displayed with the pendant case in which it was discovered

The tablet itself dates back to about 300-200 BCE, while the pendant case/chain that accompanies it was likely made about 400 years later, during the Roman era. It's believed that the tablet was originally buried with the dead, and that an unknown individual later removed it from the burial site and stuffed it into the pendant case. Unfortunately, in order to make it fit, they simply rolled it up and then snipped off the tip of the tablet. The final lines of the inscription were destroyed in the process.

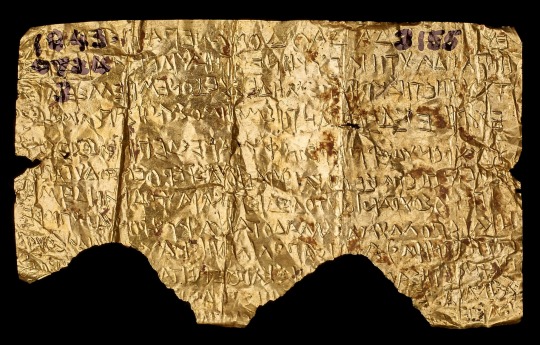

The inverse side of the Petelia tablet

These textual amulets/lamellae are often referred to as totenpässe ("passports for the dead"). They were used as roadmaps to help guide the dead through the Underworld, but they also served as indicators of the elite/divine status of certain individuals, ultimately providing them with the means to obtain an elevated position in the afterlife.

The Petelia tablet is incised with an inscription in ancient Greek, and the translated inscription reads:

You will find a spring on your left in Hades’ halls, and by it the cypress with its luminous sheen.

Do not go near this spring or drink its water. You will find another, cold water flowing from Memory’s lake; its guardians stand before it.

Say: "I am a child of Earth and starry Heaven, but descended from Heaven; you yourselves know this. I am parched with thirst and dying: quickly, give me the cool water flowing from Memory’s lake."

And they will give you water from the sacred spring, and then you will join the heroes at their rites.

This is [the ... of memory]: [on the point of death] ... write this ... the darkness folding [you] within it.

The final section was damaged when the tablet was shoved into the pendant case; sadly, that part of the inscription does not appear on any of the other totenpässe that are known to exist, so the meaning of those lines remains a mystery (no pun intended).

Lamellae that are inscribed with this motif are very rare. They're known as "Orphic lamellae" or simply "Orphic tablets." As the name suggests, these inscriptions are traditionally attributed to an Orphic-Bacchic mystery cult.

The inscriptions vary, but they generally contain similar references to a cypress tree, one spring that must be avoided, another spring known as the "Lake of Memory," the sensation of thirst, and a conversation with a guardian (or another entity within the Underworld, such as the goddess Persephone) in which the dead must present themselves as initiates or divine individuals in order to be granted permission to drink from the Lake of Memory. They are thereby able to obtain privileges that are reserved only for the elite.

Though the specifics of this reward are often vague, it may have been viewed as a way to gain access to the Elysian Fields (the ancient Greek version of paradise) or as a way to participate in sacred rites; some totenpässe suggest that it may have allowed the soul to break free from the eternal cycle of reincarnation. Regardless, the overall objective was likely the same: to obtain a special status and acquire privileges that were inaccessible to most of the souls in the Underworld.

Sources & More Info:

Altlas Obscura: The Ancient Greeks Created Golden Passports to Paradise

The Museum of Cycladic Art: The Bacchic-Orphic Underworld

Bryn Mawr College: Festivals in the Afterlife: a new reading of the Petelia tablet

The Getty Museum: Underworld (imagining the afterlife)

The British Museum: Petelia tablet (with pendant case; chain)

#archaeology#history#anthropology#ancient greece#ancient history#greek mythology#Petelia tablet#Greek mysteries#orphic mysteries#orphism#greek underworld#hades#persephone#anthropology of death#religon#afterlife#tw death#classical antiquity#classical archaeology#ticket to paradise#whoever damaged this#probably#got#a#ticket#to tartarus#instead

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Jordan :D

greetings yall! what i love more than my home and heritage and history is yapping about it lol so special thanks to my dearest @sporadicallyanenthusiast whos curiosity and deep desire for knowledge mirrors mine and makes my life all the more wonderful :3

anyway heres a short history of what is now my homecountry of jordan mostly translated from my first year jordan history and civics book lol bc it was presented in nice concise points :]

^^^ jordanian shemagh & national flower; black iris. in typical me fashion i sidetracked so hard and ended up going on a very long and interesting tangent where i started reading about orientalism and will probably be talking about it too after i finish edward saids book and doing some more research on my part (shout out to my super cool parents for being a big part of said research lol) so yeah stay tuned ig

--

The name jordan means decending/ down flowing (there are many hypotheses about the etymology but hebrew & greek is what im going with here), which is a reference to the jordan river that runs from lake tiberias to the dead sea, and is extremely crooked lol.

In arabic its read as al urdun, a cognate to the hebrew yarden, from yarad meaning “the descender”. according to the arabic wiki page it also means severity and dominance which i find quite interesting.

--

the prehistoric civilisations that lived in what is now jordan include:

canaanites (الكنعانية): circa 3000 BC, lived mostly in palestine (ariha, akka, bisan and more). around the same time several semetic peoples established themselves in syria and jordan; phoenicians centred at the coast and the amorites in the west of the euphrates river (modern day iraq)

edomites (الأدومية): circa 2000 BC, their rule extended from al aqaba (southernmost jordan) to wadi hessa in the north and their capital was basirah near al tafilah today

moabites (المؤابيون): 2000-800 BC, from wadi hessa to wadi mujib and dhiban was their capital. Their most prominent king was mesha (who iconically invented my beloved mansaf lmao) whose history was documented on the mesha stele; the longest Iron Age inscription ever found in the region, the major evidence for the Moabite language, and a unique record of military campaigns.

ammonites (العمونيون): from the northeastern moab regions since the 12th century BC, their capital was named amun which is now amman the capital of jordan.

nabteans (الأنباط): between 600-106 AD built its civilisation in the south of jordan and were proficient in agriculture, trade, and stonemasonry; the rose city, petra, is famous for its rock cut architecture. Its also one of the new 7 wonders of the world

the nabteans extended from damascus in the north and were the first to settle in the village of um al jimal near al mafraq, which served as a guard point at the borders of the badiyah/ desert to the west of palestine and reached the banks of the nile. a famous king of theirs was al harith III/ aretas philhellen (friend of the greeks) who surrounded/ sieged jerusalem in 85 BC and his rule (and therefore the independence of the nabtean kingdom) ended when the roman emperor trajan took over syria in 106 AD

roman/ byzantine empire (الحضارة الرومانية و البيزنطية): rome conquered bilad al sham in 63 AD and ruled for 400 years, during which the decapolis was formed; union of 10 hellenistic cities across jordan syria and palestine.

In jordan: philadelphia (amman), gerasa (jerash), gadara (um qais), pella (tabqet fahl), and arabella (irbid) <- my city :3 byzantine rule was confined to the eastern roman empire, and during the era of the emperor constantine (who embraced christianity in 333 AD) the decapolis flourished noticeably with the influx of roman christians who sought refuge there. anyway arts and architecture and irrigation projects and agriculture prospered, christianity became the official religion of the population and churches were built decorated with mosaics to the east and west of the jordan river (which is religiously significant btw to both christianity and judaism) esp during justinians rule (527-565 AD)

Ghassanids (الغساسنة): are of arab origins from yemen who migrated in the late 3rd century AD after the collapse of a great dam known as ma’rib (which I was fascinated to learn was mentioned in the quran in the chapter of saba (sheba) 34:15-17)

anyhow they settled in bilad al sham and took houran as their capital (houran is the name of the area between syria and jordan back in ye olden days when borders didn’t exist). their rule and reach grew slowly till they eventually had tadmur (palmyra) in syria to the euphrates and al aqaba under their control. the official language was arabic but they mastered aramaic as it was the language of trade at the time, dominating the trade routes that linked yemen to bilad al sham. they embraced christianity as well, allying themselves with the byzantines, and their rule came to an end after their amirs/ princes divided among themselves around 584 AD.

--

which brings us to the end of prehistoric civilisations of jordan! thank u for reading this far I appreciate it lol. hope u enjoyed :D

will reblog with the islamic eras of jordan up until the ottoman empire which ill get into someday after I read the two books I bought nearly 2 years ago :')

#palestinian city names bc israel can go fuck itself#jordan#history#ancient civilisations#had way too much fun making this lol#canaanite#edomites#moab#ammonite#nabteans#roman empire#byzantine empire#ghassanids#arabic#hebrew#jordan river#ancient history#damascus#euphrates river#iraq#syria#jerusalem#palestine#yemen#aqaba#petra#unesco world heritage site#barely proofread sdfgfd#ignore the inconsistencies pls#shemagh

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Heritage News of the Week

Discoveries!

Archaeologists in London have found the remains of the city’s first basilica underneath the basement of an office building set to be demolished. Dubbed “the beating heart of Roman London,” it has been deemed one of the most important finds from the city’s Roman history.

Major discovery of a pre-Roman necropolis in Trento

More than 200 tombs have been discovered beneath layers of Roman and medieval material, at a depth of eight metres below the current street level.

Gold jewelry with leopard and tiger designs unearthed in 2,400-year-old burial in Kazakhstan

Striking gold jewelry and weapons made by Sarmatian nomads have been unearthed from three burial mounds in Kazakhstan that date to about the fifth century B.C.

Britain’s largest Viking Age building found near Holme St Cuthbert

Archaeologists from Grampus Heritage & Training Limited have uncovered a Viking Age timber building near the village of Holme St Cuthbert, located in the county of Cumbria, England.

People have been dumping corpses into the Thames since at least the Bronze Age, study finds

A new study of human remains dredged from the Thames River reveals that people frequently deposited corpses there in the Bronze and Iron ages.

Recent excavations unveil five remarkable statues, shedding light on Perge’s Roman heritage

During the excavations in the ancient city of Perge in Antalya, one of the most organized Roman cities of Anatolia, five different statues were unearthed.

Man buried with Roman pugio found at ancient fortress

Excavations at Cortijo Lobato, conducted during the construction of a new photovoltaic park, have revealed the skeletal remains of a man buried with a pugio (a Roman dagger) placed on his back.

Burial of ascetic monk in chains reveals surprising identity: A woman in Byzantine Jerusalem

A recent archaeological discovery near Jerusalem has challenged long-held beliefs about ascetic practices in the Byzantine era, revealing the remains of a woman in a burial typically associated with male ascetics, thus prompting a reevaluation of women’s roles in extreme religious traditions of the 5th-century AD.

Rare bronze beverage filter discovered in Hadrianopolis

Archaeologists excavating in Hadrianopolis, located in Turkey’s Karabük province, have discovered a 5th century AD bronze object believed to have been used as a beverage filter.

2,000-year-old artifacts found at Swat’s Butkara site in Pakistan, including coins and Kharosthi inscriptions

Excavations at the Butkara Stupa, located near Mingora in Swat, Pakistan, have uncovered significant findings, including two-thousand-year-old coins, pottery, and inscriptions in the Kharosthi script, all of which provide valuable insights into the Saka-Parthian period and the rich Buddhist heritage of the region.

Key Silla Kingdom palace site found in South Korea after decade-long probe

A decade-long investigation conducted by the Korea Heritage Service has uncovered a crucial palace site of the Silla Kingdom (57 BC-935 AD), revealing findings that could potentially reshape the historical narrative of this ancient kingdom.

Cemetery for enslaved people rediscovered at Andrew Jackson’s Tennessee plantation

Long-obscured and forgotten, the burial plots of more than two dozen people enslaved by the seventh president of the US are located and honoured

Museums

The Textile Museum of Canada will close its doors on 16 February, with a re-opening date still to be determined but tentatively expected in September. Funding is a major concern, along with accessibility—the building’s elevator is in need of serious repair.

The Alabama museum grappling with the 'Gulf of America'

The world's only museum dedicated to the history and culture of the Gulf of Mexico may be in hot water following Trump's decision to change the name of the planet's largest gulf.

I feel for this museum. They spent $100,00 to rebrand and less than a year later the orange one blows things to pieces.

Also, @greenekatgrey, fyi, this museum is planning an exhibit about your favourite, Jimmy Buffett.

The Bunny Museum in LA looks to rebuild after fires

The co-founders of the world’s largest collection of rabbit-themed items want to recreate “the hoppiest place in the world.”

History lovers invited to sketch museum artefacts

A Devon museum is encouraging people to get closer to their local history - by drawing it.

Repatriation

National Museums Northern Ireland (NMNI) is to return further human remains to Hawaii.

Have you seen this book?

The initiative ‘Have you seen this book?’ also known as the Library of Lost Books, is run by the Leo Baeck Institute and intends to both publicise the history of these books in a beautifully created interactive exhibition and to appeal to the general public for their support in locating them.

Heritage at risk

The Uzbekistan government is on an ambitious tourism drive – but is sparring with heritage experts over how to protect its historical sites.

AI-powered initiative HeritageWatch.AI to safeguard cultural heritage from crises

HeritageWatch.AI, a new collaboration launched in Paris, combines satellite imagery, 3D modelling, and AI to provide real-time data that will help protect cultural heritage sites from disasters and conflict.

Organised crime threatening cultural heritage by trafficking irreplaceable artefacts

Cultural artefacts and historic sites around the world are being threatened by organised crime groups who traffic the items for lucrative profits, a team of researchers from The University of Queensland found.

Israeli bill on West Bank antiquities oversight faces opposition from government body

The Israel Antiquities Authority (IAA), a body of the Israeli government that oversees national artifacts and sites, rejected a proposal to take on an official role overseeing West Bank antiquities under a bill presented by Likud party member Amit Halevi on Tuesday.

As Sudan’s civil war rages on, its heritage is under siege

At least six museums and multiple historic sites have suffered looting or damage as a result of the conflict

Odds and ends

Almost eight centuries after it was crafted in a workshop in Salisbury, the Sarum Master Bible, a vividly illustrated medieval manuscript, has returned home and will go on display at the city’s cathedral this month.

Iraq’s ancient marshes are running out of time

Iraq’s southern marshes, the birthplace of early civilization, face ruin from environmental and political mismanagement. As the water disappears, so too does a 5,000-year-old culture.

Smell like an Egyptian: researchers sniff ancient mummies to study preservation

Scientists hope that smell could be a non-invasive way to judge how well-preserved a mummy is

The landmark home of a California family was destroyed by fire. Now a city reckons with its painful history

The Bidwell mansion was a symbol for the city of Chico, but for some it was a reminder of colonization and genocide

Library Crunchie muncher sought for 'relic' wrapper

Workmen dismantling shelves at Cambridge University Library got a sweet surprise when out fluttered an old chocolate bar wrapper from at least 50 years ago.

Blue plaque unveiled to honour boy chimney sweep

A blue plaque to commemorate a Victorian child chimney sweep has been unveiled at the place of his death. George Brewster, 11, became trapped in the chimney in 1875, and could not be saved. He is thought to be the last of what were known as "climbing boys" to have died in England.

Groundbreaking botanical discoveries on Captain Cook voyage were thanks to Indigenous people

New book reveals that Pacific islands inhabitants helped European scientists identify hundreds of plant species

Date set for Sycamore Gap tree felling trial

Daniel Graham, 39, and Adam Carruthers, 32, both from Cumbria, are charged with causing £622,191 worth of criminal damage to the famous Northumberland tree.

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Favorite History Books || Assyria: The Rise and Fall of the World’s First Empire by Eckart Frahm ★★★★☆

… This birth of Assyria in the proper sense of the term— its emergence as a land that included great cities such as Nineveh, Calah, and Arbela, and soon others much farther away— marked the beginning of a new era: the Middle Assyrian period. Now a full-fledged monarchy, Assyrians started to see their land as a peer of the most powerful states of the time, from Babylonia in the south to Egypt in the west. During the eleventh century BCE, the Assyrian kingdom experienced a new crisis, this one caused by climate change, migrations, and internal tensions. It lost most of its provinces, especially in the west. But when the dust settled, it managed to rise from the ashes faster than any of the other states in the region. A number of energetic and ruthless Assyrian rulers of the Neo-Assyrian period (ca. 934– 612 BCE) took advantage of the weakness of their political rivals, embarking on a systematic campaign of subjugation, destruction, and annexation. Their efforts, initially aimed at the reconquest of areas that had been under Assyrian rule before and then moving farther afield, were carried out with unsparing and often violent determination, cruelly epitomized in an aphoristic statement found in another of Esarhaddon’s inscriptions: “Before me, cities, behind me, ruins.” . . . During the last years of Esarhaddon’s reign, Assyria ruled over a territory that reached from northeastern Africa and the Eastern Mediterranean to Western Iran, and from Anatolia in the north to the Persian Gulf in the south. Parks with exotic plants lined Assyrian palaces, newly created universal libraries were the pride of Assyrian kings, and an ethnically diverse mix of people from dozens of foreign lands moved about the streets of Assyrian cities such as Nineveh and Calah. Yet it was not to last. Only half a century after Esarhaddon’s reign, the Assyrian state suffered a dramatic collapse, culminating in the conquest and destruction of Nineveh in 612 BCE. Assyria’s fall occurred long before some better- known empires of the ancient world were founded: the Persian Empire, established in 539 BCE by Cyrus II; Alexander the Great’s fourth-century BCE Greco-Asian Empire and its successor states; the third-century BCE empires created by the Indian ruler, Ashoka and the Chinese empero, Qin Shi Huang; and the most prominent and influential of these, the Roman Empire, whose beginnings lay in the first century BCE. The Assyrian kingdom may not have the same name recognition. But for more than one hundred years, from about 730 to 620 BCE, it had been a political body so large and so powerful that it can rightly be called the world’s first empire. And so Assyria matters. “World history” does not begin with the Greeks or the Romans— it begins with Assyria. “World religion” took off in Assyria’s imperial periphery. Assyria’s fall was the result of a first “world war.” And the bureaucracies, communication networks, and modes of domination created by the Assyrian elites more than 2,700 years ago served as blueprints for many of the political institutions of subsequent great powers, first directly and then indirectly, up until the present day. This book tells the story of the slow rise and glory days of this remarkable ancient civilization, of its dramatic fall, and its intriguing afterlife.

#historyedit#assyrians#neo assyrian empire#asian history#iraqi history#history#history books#nanshe's graphics

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

A cold winter, an old poem, and Mabon ap Modron

Short is the day; let your counsel be accomplished.

(Image source at the end)

Mabon is a figure of medieval Welsh folklore with a relatively minor (if distinctly supernatural) role in the early Arthurian tale Culhwch ac Olwen; a hunter who must be released from a magical prison. Unlike a lot of figures floated as euhemerised deities on pretty questionable grounds, his connection to the god Maponos, worshipped in Britain and Gaul in the Roman era, is fairly sound.

Recently I've been reading Jenny Rowland's Early Welsh Saga Poetry (bear with me, this will all come together), which I was led to by my interest in the 6th-century north-Brittonic king Urien Rheged and the stories that sprung up around him and related figures (his bard the celebrated Taliesin, and his son Owain, later adapted into the Yvain of continental Arthuriana). It includes an early medieval poem called Llym Awel, which immediately struck a chord with me.

It begins with a description of the harshness of winter, then transitions into either a dialogue debating bravery/foolishness versus caution/cowardice, or (I favour this interpretation) a monologue in which the narrator debates this within himself. In the final section, the context is revealed; the narrator has a dialogue with his guide through this frozen country, the wise Pelis, who encourages him and their band to continue in order to rescue Owain son of Urien from captivity.

(There then follow several more stanzas which seems to be a totally separate poem--Llywarch Hen, a different figure with his own saga-cycle, laments the death of his son. The traditional interpretation was that all this was a single poem, the narrator of the first part was Llywarch's son, and this shift represented a 'flash forward' to after the expedition ended poorly. Rowland points out various inconsistencies that point to this whole section being a different poem altogether, motivated by a mistaken interpolation of an earlier stanza with names from the Llywarch cycle)

Where this comes back to my introduction is the book also theorises that the story the poem is telling was originally about Mabon, not Owain. Rowland points to several instances where the two were conflated; from early poetry in the Book of Taliesin to the 'Welsh Triads' (lists of things/people/ideas bards used as aids to remembering legends) to much later folklore. As mentioned, one of the only stories we have about Mabon centres around his role as an "Exalted Prisoner" (as the Triads put it) whose release bears special significance, while no other such story survives about Owain.

This is obviously all conjectural, but I feel there's even another angle of support for the idea the book doesn't consider. The Romano-British/Gallo-Roman Maponos was very consistently equated with Apollo, god of the sun, in inscriptions (most of which show worship located in the same area of Owain's later kingdom of Rheged, which could support the possibility of folklore getting mixed together). Certainly identification with a god who appears as idealised beautiful youth would fit his name--"Mabon son of Modron/Maponos son of Matrona" is basically "Young Son the son of Great Mother". This could be all there was to the connection; Roman syncretism wasn't always 1:1. But it's entirely possible both figures shared the spectrum of youth-renewal-sun associations, or that Maponos originally didn't but picked these up over centuries of being equated with Apollo.

Whatever the case (and with emphasis that this is not sound enough to be considered anything like scholarship, just an interesting "what-if"), if Apollini Mapono was associated with the sun as well as youth, wouldn't it make perfect sense for the story of journeying to release him from captivity to have a winter setting? The winter is harsh, but if the sun can be set free, warmer times will come again.

(I'm a little hesitant in writing this, because "seeing sun-gods everywhere" was a bit of a bad habit of 19th-century scholars whose work is now disproven, especially in Celtic studies, and the internet loves to let comparative mythology run wild with vague connections, but I think the case is reasonable here)

I'll put below Rowland's translation of the poem, with the Llywarch stanzas removed (so something like its 'early' form):

Sharp is the wind, bare the hill; it is difficult to obtain shelter. The ford is spoiled; the lake freezes: a man can stand on a single reed.

Wave upon wave covers the edge of the land; very loud are the wails (of the wind) against the slope of the upland summits - one can hardly stand up outside.

Cold is the bed of the lake before the stormy wind of winter. Brittle are the reeds; broken the stalks; blustering is the wind; the woods are bare.

Cold is the bed of the fish in the shadow of ice; lean the stag; bearded the stalks; short the afternoon; the trees are bent.

It snows; white is its surface. Warriors do not go on their expeditions. The lakes are cold; their colour is without warmth.

It snows; hoarfrost is white. Idle is a shield on the shoulder of the old. The wind is very great; it freezes the grass.

Snow falls on top of ice; wind sweeps the top of the thick woods. Fine is a shield on the shoulder of the brave.

Snow falls; it covers the valley. Warriors rush to battle. I do not go; an injury does not allow me.

Snow falls on the side of the hill. The steed is a prisoner; cattle are lean. It is not the nature of a summer day today.

Snow falls; white the slope of the mountain. Bare the timbers of a ship on the sea. A coward nurtures many counsels.

Gold handles on drinking horns; drinking horns around the company; cold the paths; bright the sky. The afternoon is short; the tops of the trees are bent.

Bees are in shelter; weak the cries of the birds. The day is harsh; . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . White-cloaked the ridge of the hill; red the dawn.

Bees are in shelter; cold the covering of the ford. Ice forms when it will. Despite all evading, death will come.

Bees are in captivity; green-coloured the sea; withered the stalks; hard the hillside. Cold and harsh is the world today.

Bees are in shelter against the wetness of winter; ?. …; hollow the cowparsley. An ill possession is cowardice in a warrior.

Long is the night; bare the moor; grey the hill; silver-grey the shore; the seagull is in sea spray. Rough the seas; there will be rain today.

Dry is the wind; wet the path; ?….. the valley; cold the growth; lean the stag. There is a flood in the river. There will be fine weather.

There is bad weather on the mountain; rivers are in strife. Flood wets the lowland of homesteads. ? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

The stooped stag seeks the head of a sheltered valley. Ice breaks; the regions are bare. A brave warrior can escape from many a battle.

The thrush of the speckled breast, the speckle-breasted thrush. The edge of a bank breaks against the hoof of a lean, stooping, bowed stag. Very high is the loud-wailing wind: scarcely, it is true, can one stand outside.

The first day of winter; brown and very dark are the tips of the heather; the sea wave is very foamy. Short is the day; let your counsel be accomplished.

Under the shelter of a shield on a spirited steed with brave, dauntless warriors the night is fine to attack the enemy.

Strong the wind; bare the woods; withered the stalks; lively the stag. Faithful Pelis, what land is this?

Though it should snow up to the cruppers of Arfwl Melyn it would not cause fearful darkness to me; I could lead the host to Bryn Tyddwl.

Since you so easily find the ford and river crossing and so much snow falls, Pelis, how are you (so) skilled?

Attacking the country of ?. does not cause me anxiety in Britain tonight, following Owain on a white horse.

Before bearing arms and taking up your shield, defender of the host of Cynwyd, Pelis, in what country were you raised?

The one whom God deliver from the too-great bond of prison, the type of lord whose spear is red: it is Owain Rheged who raised me.

Since a lord has gone into Rhodwydd Iwerydd, oh warband, do not flee. After mead do not wish for disgrace.

We had a major cold snap here recently, and having spent day after day going "WHY is it so COLD" every time I emerged from a pile of blankets and hot water bottles--and even having come through it, I'm sure we'll be right back there in the coming months--needless to say, a lot of this stuff resonated.

Rowland discusses some ambiguous lines that suggest the narrator is ultimately overcoming their doubts to boldly press on throughout the poem, even before Pelis chimes in:

A coward nurtures many counsels. i.e. "Deliberating this isn't getting anything done"

Despite all evading, death will come. i.e. "When danger approaches, hiding won't help."

A brave warrior can escape from many a battle. i.e. "Conversely, you can survive by meeting that danger head-on."

There will be fine weather. i.e. "Amid all this description of how cold and miserable it is now, a reminder that warmer times will come again"

Short is the day; let your counsel be accomplished. i.e. "Let's hurry up and act decisively."

-with brave, dauntless warriors the night is fine to attack the enemy. i.e. "Fighting during night (much less during winter) is rarely done in this era because it's hard and it sucks, but we're built different, we'll simply handle it."

In my opinion, many of these would take on an interesting dimension with the above interpretation vis a vis Mabon; it's best to press on through the cold and difficult conditions, because success (the release of the sun from frozen "imprisonment"--a metaphor the poem uses multiple times with animals) will bring an end to those conditions. If the sun can be released, there will be fine weather.

Now, I'm not saying there was some "lost original version" of this poem itself. It's a medieval poem about Owain, and quite a moving one in that context; frankly the addition of the Llywarch stanzas, even if they change the meaning, might make it more moving still. But I do agree it's a distinct possibility that the story the poem was retelling was originally one about Mabon, and I would add that it has perhaps gone unappreciated that this could contain otherwise unattested details to the story of the Exalted Prisoner, and just why it was so important to set Maponos Apollo free.

And on a personal level, especially these past couple weeks while I shiver and glance at the mounting ice outside, I can't help be touched by the imagery of summoning up the courage to press on through the cold to find this buried god.

- - -

For further reading, Rachel Bromwich's Trioedd Ynys Prydein: The Triads of the Island of Britain, as well as going through the Triads themselves, contain an encyclopedia of every figure mentioned in them (so near enough every figure of medieval Welsh legend, literature and folklore, including all the ones mentioned here), and runs down basically everything we know about each one. An invaluable resource.

Image at the top: Winter in Gloucester, site of Mabon's imprisonment in Culhwch ac Olwen. Publicly downloadable. Link to the photographer's gallery:

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

From Frédéric Poulsen, "Le buste du bronze de Cato trouvé à Volubilis", in the journal of the Académie des inscriptions et belles-lettres, 1947:

"The first thing which surprises [the viewer] about this admirably preserved bust is how clearly it has retained a certain rustic trace. This is a true country man, like to the wealthy farmers of the agricultural nations of our day. Cato, however, belonged to the stifling circle of the high Roman nobility (which fact is demonstrated above all by the marriages of his sisters and daughter). Here, he appears as the descendant of Cato Priscus, that prototype of the great Roman country man—and the urban life of multiple generations of that family, three of whose representatives held the consulship, has not erased this spirit.

The second great impression [one has] of this visage is the seriousness of its features, in perfect accord with the literary tradition: "It was difficult," Plutarch says (Plut. Cat. Min. 1-2), "to move Cato to laughter, and rare that a smile should appear on his face". He was harsh, tenacious, and, when ill, demonstrated an admirable forbearance.

Adding to the serious expression of those features is the movement of the head: it is turned toward the left shoulder and, at the same time, gently, peacefully inclined; and the movement which tenses the neck muscles, combined with the lines of the mouth, creates an impression of severity, even of unavailability. It is not impossible that the absence of colored stones, which would have once indicated the iris and pupils, contributes to the hardness of the gaze.

At the time of his death, Cato was forty-eight years old, but this portrait speaks of a man who lived a hard life and was aged prematurely by it. It is true that [one contemporary scholar] finds the Cato of this bust younger than the age of his death—an impression probably due to his observation of the bust's profile, since from that angle the expression is both younger and more peaceful, as if disclosing traces of the features of a young man; it is only by virtue of the large nose, particularly its curve, that a powerful masculine energy is revealed and even emphasized.

But, seen from the front, the face is haggard, the forehead is crossed by deep wrinkles that run parallel to the thick eyebrows, the creases that run down from the lower eyelids, the large and profound furrows of the cheeks, and the great lines between the mouth and chin, all contribute to give the face an expression of pain and age. In my opinion he could well have been a sexagenarian, this great country man with his proud, tranquil expression.

[...]

Even if the portrait from Volubilis dates from as late as ±150 years after Cato's death [the author dates the bust about the time of Domitian or Trajan, ed.], it goes without saying that an older and more contemporary portrait has been copied. This is confirmed when one observes the profile of the bust once more: one sees the tufts of hair in the nape of the neck shaped like long, curved leaves, and stylized in a bladelike form, a mode of stylization characteristic of precisely the period in which Cato lived, ±50 BCE.

[...]

Naturally we might suppose that a certain alteration of the features must have taken place in this transmission from copyist to copyist. [...] Where an artist, from the time of Nero for example, has copied a republican portrait meant for the atrium of a young, newlywed nobleman [an ancestral imago], the result is inevitably a mixture of styles, a circumstance which makes it still more difficult to date many Roman portraits.

Certain points of resemblance, then, may have been diminished in the face of the Volubilis Cato—on the other hand, the artistic effect could have been strengthened by an emphasis on the essential lines and forms of the visage. Happily, the artist appears to have stuck to the veracity of the original, without adding any suggestions of that saintliness or divine inspiration which the writers of the imperial era attribute to Cato, from Seneca to Plutarch."

#cato minor#c#il pourrait être sexagénaire — ce grand paysan à l'expression tranquille et fière. ;;_;;#good to stretch my french a little. also really funny how whipped mr. poulsen obviously is. another one bites the dust

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

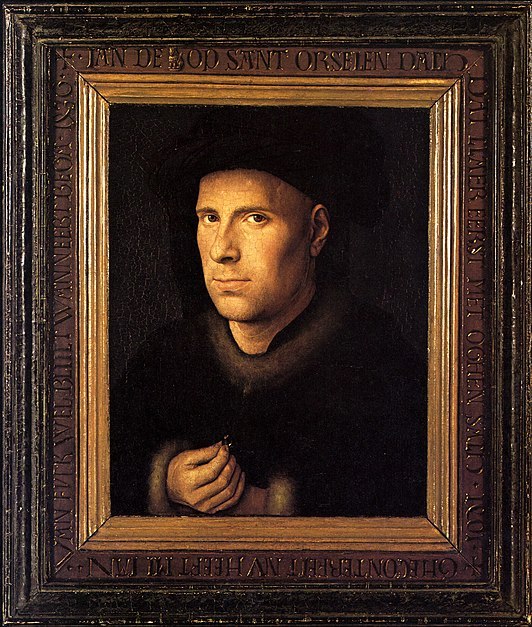

Differences Between the Southern and Northern Renaissance: A Study Through Jan van Eyck's "Portrait of a Man" (self portrait?)"

Written by ArtZoneStuff, 2024

The Renaissance, a period of cultural rebirth and revival of classical learning, manifested differently in the southern and northern regions of Europe. While both regions shared a common interest in humanism, art, and science, the way these ideas were expressed varied significantly due to differing cultural, social, and economic contexts.

The Southern Renaissance, centered in Italy, emphasized classical antiquity, proportion, perspective, and human anatomy. Artists like Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519), Michelangelo (1475-1564), and Raphael (1483-1520) focused on idealized beauty, harmony, and balanced compositions.

In contrast, the Northern Renaissance, which flourished in regions such as the Netherlands, Germany, and Flanders, focused more on meticulous detail, naturalism, and domestic interiors. Northern artists like Jan van Eyck (1390-1441), Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528), and Hieronymus Bosch (?-1516) were known for their detailed and realistic depictions of nature, landscapes, and everyday life. Their work often contained rich symbolism and a focus on surface textures and fine details.

Jan Van Eyck's self portrait

Jan van Eyck's "Portrait of a Man" (Appendix 1), also known as his Self-Portrait from 1433, is a small-scale Dutch portrait measuring 25.9 x 33.1 cm (Google Arts and Culture, n.d.). The man in the painting emerges from a dark background, with his body depicted in three-quarter view. On his head, he wears a red chaperon, often mistaken for a turban, styled upward rather than hanging down (Nash, 2008, p.154). His dark fur-lined garment resembles the attire in "The Arnolfini Portrait" (Appendix 2), indicative of wealth during an era when textiles were extremely costly (ArtUK, 2019). His detailed face features a faint stubble, white highlights in his eyes and on his cheekbones, non-idealized features such as wrinkles and veins on his forehead, showcasing the Northern realism (Hall, 2014, p.44).

As described by the English art historian James Hall, the painting appears almost fleeting and alive - with the gaze seeming to capture the viewer before the face, and just like that, the penetrating stare turns away, perhaps followed by the light streaming from the right (Hall, 2014, p.43). The portrait conveys that the artist scrutinizes everything closely, including himself, without losing sight of the bigger picture (Hall, 2014, p.43). All these naturalistic details clearly indicate a Flemish painting.

The work is considered a self-portrait due to the frame. Jan van Eyck often used frames he designed and painted to enhance understanding and add meaning to his works (Hall, 2014, p.43; The National Gallery, 2021, 4:45-5.15). The gilded original frame of "Portrait of a Man" is crucial for interpreting the piece. Inscribed at the top of the frame is Jan van Eyck’s motto: "Als Ich can," translated to English: "As I can." At the bottom is his signature, and the date in Roman numerals: October 21, and in Arabic numerals, the year 1433. This results in the inscription: "Jan van Eyck made me on October 21, 1433" (Hall, 2014, p.43). He capitalizes the "I" in "Ich," playing on the pun Ich/Eyck. The motto can be interpreted as either boastful, "As I can," or modest, "As best as I can" (Hall, 2014, p.43).

The inscription highlights the relationship between words and image, indicating his awareness of his talent. His skill in painting surpasses that of a craftsman, which painters in this period was considered as. "As I can" suggests he is the only one capable of achieving such stylistic naturalism which cannot be imitated (The National Gallery, 2021, 5:10-5:58). "Jan van Eyck made me" also reflects a high degree of self-awareness, as he claims a painting of this quality, emphasizing that he created it and is conscious of his own abilities (The National Gallery, 2021, 5:10-5:58). All of this, along with his signing of his works as one of the first artists to do so, demonstrates a desire not to remain an anonymous craftsman (Hall, 2014, p.43; Farmer, 1968, p.159; Blunt, 1962).

The motto "Als Ich can" appears on several of his works, but the self-portrait is the only one where it is so prominent and clear. Additionally, the motto is placed at the top of the frame, where he would usually write the model’s name, thus, the motto can be seen as the model's identity (The National Gallery, 2021, 5:15-6:25). This, along with his direct gaze at the viewer, suggesting it was painted from a mirror, are the strongest indicators that the portrait is a self-portrait (Hall, 2014, p.43).

However, this can be taken with some skepticism, as other portraits by him, such as "Portrait of Margaret van Eyck" (Appendix 3) and "Portrait of Jan De Leeuw" (Appendix 4), share the same penetrating gaze (Pächt, 1994, p.107). This might instead indicate his realism, where the painter’s position does not function as an observer but rather takes an active role. The model’s direct gaze towards the viewer shows that the model has looked at Jan Van Eyck. This shows Jan Van Eyck possessing an active role, which was very different from painters in this period, and by doing so, creating a new respect for the painter as an artist, again showcasing his self-awareness of his position and talent (Pächt, 1994, pp.106-108).

Literature

Books and Journals:

Hall, James (2014). The self-portrait, a cultural history. London: Thames & Hudson Ltd

Nash, Susie (2008). Northeren Renaissance Art. New York: Oxford University Press.

Blunt, Anthony (1962). The Social Position of the Artist. Artistic Theory in Italy, 1450-1600. Oxford & New York: Oxford University Press

Farmer, David (1968). Reflections on a Van Eyck Self-Portrait. Oud Holland. S. 159

Online

Google Arts and Culture (n.d.): Portrait of a Man in a Red Turban (selfportrait). Found at: https://artsandculture.google.com/asset/portrait-of-a-man-in-a-red-turban-selfportrait/SAFcS1U8kYssmg?hl=en

ArtUK: Butchart, Amber (2019). Fashion reconstructed: the dress in Van Eyck's Arnolfini portrait. Found at: https://artuk.org/discover/stories/fashion-reconstructed-the-dress-in-van-eycks-arnolfini-portrait

The National Gallery (2021). Jan van Eyck's self portrait in 10 minutes or less | National Gallery. Found at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VMJK1EDG2X8&t=1s&ab_channel=TheNationalGallery

#my post#history#famous artists#art exhibition#jan van eyck#renaissance#northern renaissance#netherlands#flanders#germany#painting#oil painting#art history#artwork#art#histoire#literature#portrait#raphael#leonardo da vinci#arnolfinis wedding#art historian#research#analysis#art analysis#art anatomy#self portrait#self portrature#self portrayal#portraiture

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sat, Jan 12 - I visited the ancient Roman city of Sardes today for the first time. (Information about the city is under this post.) It consisted of the Gymnasium with the remains of many Byzantine shops including restaurants and painting shops, a public pool, tombs, and a Synagogue. It was truly refreshing to see the place overall, but what I adored about the visit was the fact that you could imagine and experience the feeling of what it was like to be living in an ancient city, as it was empty because of the weather conditions. No voices, no noise, no motion, just the smell and the air of this ancient place. (I bet Henry Winter would die for it.) The Temple of Artemis was also close and I went there as well. I'll publish the pictures from the Synagogue and the Temple next if you want to check them out.

Sardis (/ˈsɑːrdɪs/ SAR-diss) or Sardes (/ˈsɑːrdiːs/SAR-de ess; Lydian: 𐤳𐤱𐤠𐤭𐤣, romanized: Sfard; Ancient Greek: Σάρδεις, romanized: Sárdeis; Old Persian: Sparda) was an ancient city best known as the capital of the Lydian Empire. After the fall of the Lydian Empire, it became the capital of the Persian satrapy of Lydia and later a major center of Hellenistic and Byzantine culture. It is now an active archaeological site in modern-day Turkey, in Manisa Province near Sart.

In 334 BC, Sardis was conquered by Alexander the Great. The city was surrendered without a fight, the local satrap having been killed during the Persian defeat at Granikos. After taking power, Alexander restored earlier Lydian customs and laws. For the next two centuries, the city passed between Hellenistic rulers including Antigonus Monophthalmos, Lysimachus, the Seleucids, and the Attalids. It was besieged by Seleucus I in 281 BC and by Antiochus III in 215-213 BC, but neither succeeded at breaching the acropolis, regarded as the strongest fortified place in the world. The city sometimes served as a royal residence, but was itself governed by an assembly.

In this era, the city took on a strong Greek character. The Greek language replaced the Lydian language in most inscriptions, and major buildings were constructed in Greek architectural styles to meet the needs of Greek cultural institutions. These new buildings included a prytaneion, gymnasium, theater, hippodrome, and the massive Temple of Artemis still visible to modern visitors. Jews were settled at Sardis by the Hellenistic king Antiochos III, where they built the Sardis Synagogue and formed a community that continued for much of Late Antiquity.

In 129 BC, Sardis passed to the Romans, under whom it continued its prosperity and political importance as part of the province of Asia. The city received three neocorate honors and was granted ten million sesterces as well as a temporary tax exemption to help it recover after a devastating earthquake in 17 AD.

Sardis had an early Christian community and is referred to in the New Testament as one of the seven churches of Asia. In the Book of Revelation, Jesus refers to Sardians as not finishing what they started, being about image rather than substance.

I take the pictures that are on my blog myself. In case you're interested in this post, I also post/reblog content including travel/cultural pictures, books, book recommendations, analysis, quotes, anything related to movies, series, and girl blog entries.

#sardes#ancient rome#ancient greek#gymnasium#ancient history#ancientmonuments#roman architecture#archeology#blog#travel#history#the secret history#henry winter#synagogue#dark academia#aesthetic#light academia#books#girlblogging#hellenistic#reading#if we were villains

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

2,000 Bronze Statue Fragments Found in Turkey Ancient Scrap Yard

Archaeologists in Izmir, Turkey have made an extraordinary discovery in the ancient city of Metropolis: Approximately 2,000 bronze statue fragments have been found in a section believed to have served as an “ancient scrap yard”.

The excavations are being carried out within the scope of the ‘Heritage to the Future Project’ of the Ministry of Culture and Tourism, under the direction of Prof. Serdar Aybek, Professor of Archaeology at Dokuz Eylül University, and in cooperation with the Sabancı Foundation.

Archaeologists have discovered evidence of many civilizations, from the earliest settlements in the Late Neolithic Age to the Classical Age, from the Hellenistic Age to the Roman, Byzantine, and Ottoman periods, in the ancient city of Metropolis, also called the “City of Mother Goddess,” where excavations have been going on since 1990.

In the ancient city, where many monumental structures were unearthed, these fragments, uncovered in an area believed to have served as an “ancient scrap yard,” offer a unique glimpse into the cultural and religious shifts of the region during the Late Antiquity period.

Professor Serdar Aybek stated that the bronze statue fragments were found in a corner of a space referred to as an “ancient scrap yard,” where they had been broken apart for melting and stored in bulk.

Aybek explained that the findings include statue pieces from the Hellenistic period and figures from the Roman era, describing them as “extraordinary discoveries, even for our field of work. We have uncovered approximately 2,000 bronze statue fragments,” he said.

He highlighted the significance of the bronze statues being broken into pieces, noting, “The collection and recycling of statues in the Late Antiquity provide concrete evidence in Metropolis. Among the findings are parts such as heads, eyes, fingers, and sandals.”

Drawing attention to the dismantling of these statues, Aybek said, “In the Late Antiquity, as mythological beliefs were abandoned in favor of monotheistic religions and Christianity became dominant in the region, bronze statues from mythological and earlier eras were dismantled. Although we do not yet have archaeological evidence to confirm this claim, we can suggest that a significant portion of them was repurposed for minting coins. During that period, rather than producing new materials, bronze groups, mainly consisting of outdated or damaged statues, were broken apart by the ancient scrap yard worker and prepared for melting.”

The fragments might be from the statues built to honor the benefactors listed in the “Metropolitan Apollonios” inscription, according to Aybek, who also underlined the historical significance of bronze statues in antiquity.

What makes this discovery even more remarkable is the evidence of recycling practices that date back over a millennium.

In addition to the fragmented statues, archaeologists discovered square and rectangular bronze plates that were probably used for statue casting and repair. This implies that, at its height, Metropolis might have served as a center for the creation or repair of bronze statues.

By Leman Altuntaş.

#2000 Bronze Statue Fragments Found in Turkey Ancient Scrap Yard#ancient city of Metropolis#ancient scrap yard#bronze#bronze statue#bronze sculpture#ancient sculpture#ancient artifacts#archeology#archeolgst#history#history news#ancient history#ancient culture#ancient civilizations#late antiquity period#ancient art

173 notes

·

View notes

Text

Archaeologists have uncovered dozens of ancient Egyptian tombs and numerous artifacts, including a remarkable set of objects made from gold foil.

An Egyptian archaeological mission coordinated by the Supreme Council of Antiquities unearthed 63 mud-brick tombs and some simple burials at the Tel el-Deir necropolis in New Damietta, a Mediterranean coast city in the country's north.

The tombs are thought to date to ancient Egypt's Late Period, which lasted from 664 to 332 B.C., the country's Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities announced in a statement.

Among these, researchers uncovered a "huge" tomb containing burials of people who appear to have been of high social class. Inside, archaeologists found a collection of gold foil artifacts in a variety of different forms, such as those shaped like religious symbols or figures.

The archaeological mission also uncovered a pottery vessel containing dozens of bronze coins from the later Ptolemaic era during the excavation, as well as a group of local and imported ceramic artifacts. The latter shed light on trade links between the ancient city of Damietta and other settlements along the Mediterranean coast.

The Ptolemaic era began following Alexander the Great's conquest of Egypt—then controlled by the Persians—in 332 B.C. A Hellenistic polity known as the Ptolemaic Kingdom was subsequently established in 305 B.C. and ruled Egypt until 30 B.C., when the region was conquered by the Romans.

Another intriguing find during the excavation in New Damietta was ushabti statuettes, small figurines used in ancient Egyptian funerary practices. They were placed in tombs in the belief that they would act as servants for the deceased in the afterlife.

The layout of the newly discovered tombs at Tel el-Deir has been seen in other ancient Egyptian tombs of the Late Period, the ministry said.

Mohamed Ismail Khaled, secretary-general of the Supreme Council of Antiquities, the latest discoveries at the Tel el-Deir necropolis highlight the fact that ancient Damietta was a center of foreign trade during different historical eras.

Earlier this month, archaeologists announced that a collection of ancient Egyptian artworks and inscriptions had been uncovered hidden below the waters of the Nile.

A joint Egyptian-French archaeological mission identified works in an area of the iconic river, near the city of Aswan, the Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities said in a statement.

The settlement that existed in this location in ancient times was strategically significant, marking the southern frontier of pharaonic Egypt.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

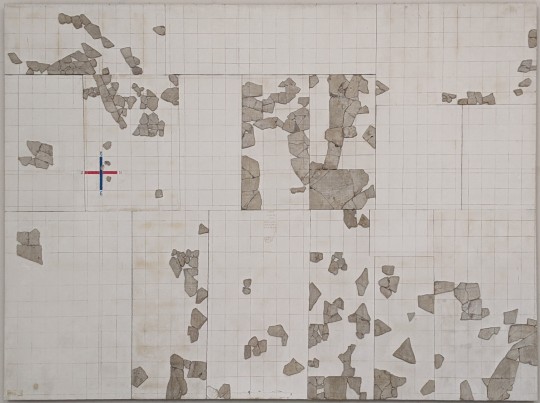

Cadastre B; Cadastre C; Cadastre A

The cadastres of Orange

Dating from 77 BC and commissioned by Vespasian, the three so-called Orange cadastres consisted of large white marble tablets, of which 300 fragments have been preserved. They represent the plan of the colony, and are the only surviving example of their kind for the entire Roman era. This cadastre provides us with information about the land and fiscal administration of the times.

The term 'cadastre' refers to the administrative organisation of ancient Roman territory for the requirements of land and fiscal administration. The cadastres covered the entire territory of the colony of Orange.

On cadastre B [image 1], the representation of the kardo and the decumanus [the two lines forming a crossroads created by a surveyor from which to measure land] enabled the territory to be divided into four major regions and determined the coordinates of each centuria. Each of these, measuring 750 x 750 metres, covered an area of 50 hectares (i.e. 200 jugeri, the unit of measurement of land area used by the Romans).

The inscriptions show the various legal statuses of the territories:

EX TR. [ex tributario]: land allocated to the settlers

REL. COL. [reliqua coloniae]: leased land (the amount of the lease and the name of the lessee are mentioned)

TRIC. REDD. [tricastinis reddita]: land restored to the defeated indigenous peoples (in this case, the Tricastini tribe).

-- Text from the Museum of Orange [with a couple clarifications]

^ detail of a section of cadastre B [image 1] showing the outline of river

^ more example details from cadastre B

+ dad for scale:

#sorry this is badly formatted bc I'm on my phone but it was SO cool to see & I wanted to post it so hopefully it makes some sense#I wish I had better detail photos but I was sort of dying from heat when I took them so#the river in particular I found very cool#thoughts#+ dad for scale bc it was fairlyhuge but I couldn't work out how to show it in the photo

55 notes

·

View notes

Text

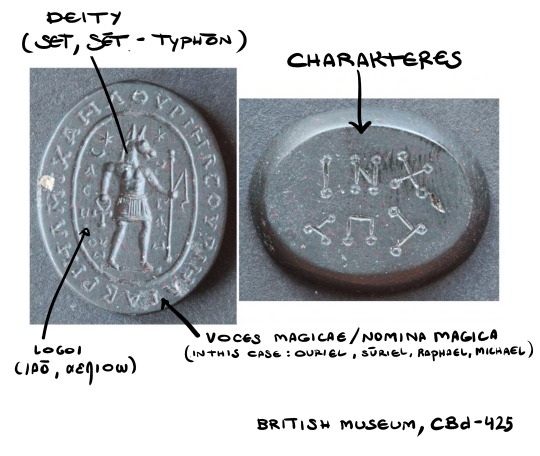

Magical Gemstones: An Abridged Guide

Magical gemstones are a type of talisman made of semiprecious stones —such as hematite, carnelian or amethyst— that were worn set in rings or as pendants and their size ranges from 1.5 cm to 3 cm.These gemstones haven't magical, protective characteristics because of the nature of the gem itself but because the representations of Gods and holy names carved conceded them virtues through holy dynamis: This is, among other things, the inherent power of divine names and/or their representations.

These depictions are normally inverted (negative) This, together with the fact that some of the gems show a certain degree of worn indicates that they were manipulated in some way—probably rubbed or even licked, in order to increase their efficacy—proves that they were not conceived as seals but as amulets or talismans.

A magical gemstone, to be considered as such, should have one or more of the following elements:

An iconographic language generally belonging to syncretic Gods or that combines Gods from different origins.

Charakteres (magical signs. They can be planetary, protective, etc.)

Voces magicae (Words of power and phrases whose formulation and structure may hide secret, sacred names of Gods as well as prayers or incantations dedicated to them, sometimes with the intention of controlling their emanations and daimonēs) and logoi (magical names, permutation of magical names and vocals).

The practice and use of magical voices was transmitted orally across the eastern Mediterranean, but it wasn't until the early 1st century b.c.e. the practice began to be included in written form. The abundance of amulets and gems with magical names and signs are evidence of this change of paradigm.

In addition, elements are usually complemented by two structural features:

The gemstone is engraved on both the obverse and the reverse, sometimes even on the edge.

The inscription appears directly and not in mirror writing.

These magic gemstones, in addition, can be magical gemstones stricto sensu and amuletic gems. The latter differ from the former in:

That the iconographic patterns they contain are explicitly described as belonging to amulets in textual sources such as Posidippus's Lithika

They bear a prophylactic inscription, usually "diaphylasse" (protect me!), "sōzon" (save me!) or "Heis Theos" (One God).

Its production began during the late Hellenistic period, but it was not until the 2nd and 4th centuries c.e. that it reached its apogee. Magical gemstones' imagery demonstrates the diversity and plurality of Greek, Roman, Egyptian, Egyptian, Christian, Gnostic and Jewish representations and ideas from the Mediterranean from the Roman period, as well as the popularity and diversity of magical activities and practices.

These magic gemstones were rarely used for evil purposes, such as harming someone. Their most common use was to offer protection or solve personal health problems: those showing an ibis tied by an altar and including the command "pésse!" (digest) were used to heal indigestion and other stomach problems; others, depicting a uterus, offered represented a womb, offered protection during childbirth and guaranteed fertility.

Although most of these magic gemstones were used as jewelry, it is possible that they also had other uses, as part of a ritual to heal a patient or as a physical component for an incantation, such as those with depictions of Harpocrates seated on a lotus the nomina magica Bainchōōōch (Bainchōōōch, Ba of the Shadow, isn't only a vox magica/nomina magica but a God on their own right. PGM aside, Bainchōōōch appears in Pistis Sophia as a triple powered deity that descends onto Jesus, giving him his powers)

An interesting fact is that of the production of magical gemstones during the 17th and 18th centuries of our era. Although the production of these gems continued during the Middle Ages and the Renaissance —irregularly, of course— they reflected the magical and religious reflected the magical and religious practices of their historical context.

This, however, was not the case during the 17th and 18th centuries, where magical gemstones of great quality and sophistication were produced, which not only reproduced the iconographic motifs and logoi of the pre-existing graeco-egyptian magic gemstones, but also introduced new ones. An example of these gems are those with representations of Christ-Osiris or Jesus-Khepri

Sources:

Nagy, M. A., (2015) Engineering Ancient Amulets: Magical Gems of the Roman Imperial Period. in D. Boschung and J. Bremmer (eds), The Materiality of Magic (Morphomata 20). Paderborn, 205-240.

Faraone, C. (2018) The Transformation of Greek Amulets in Roman Imperial Times, Filadelfia; University of Pennsylvania Press.

Simone, M., (2005) (Re)Interpreting Magical Gems, Ancient and Modern en Shaked, S., Officina Magica: Essays on the Practice of Magic in Antiquity (IJS Studies in Judaica, vol. 4), Leiden; Brill, 141-170.

Campbell-Bonner Magical Gems Database (http://cbd.mfab.hu)

#magical gemstones#gemstones#PGM#Set#Sutekh#Set-Typhon#Sēt-Typhon#magic#religious syncretism#polytheism#egyptian polytheism#hellenic polytheism#kemetic polytheism#greek magical papyri#Bainchoooch#Thoth#talismans#amulets#talismanic magic

72 notes

·

View notes

Text

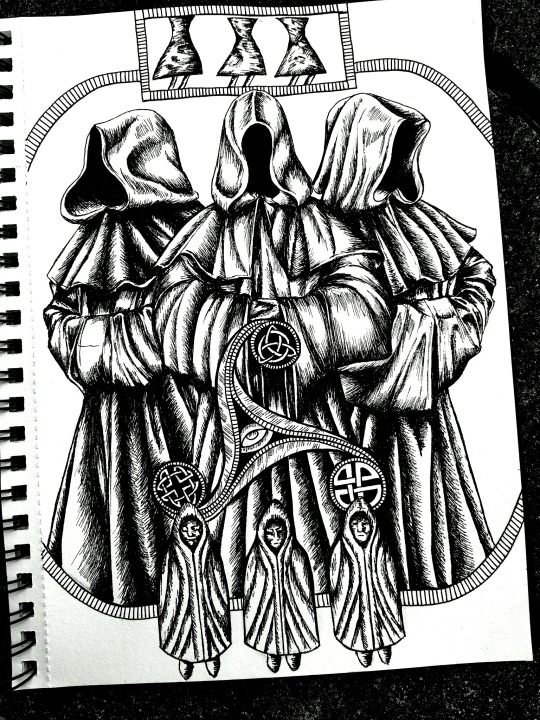

The Hooded Ones

'The Genii Cucullati are otherworldly entities whose image appears throughout Celtic Britain and Europe during the era of Roman domination. Genius means “a spirit” and a cucullus is a full-length hooded woollen robe. If they look more than a little like mediaeval monks, then this is because their successors also adopted this pragmatic attire. Thus the Genii Cucullati are literally the “hooded spirits.” In Britain they tend to be found in a triple deity form, which seems to be specific to the British representations.

No surviving documentation explains their identity or function. Instead what we know of them is pieced together from archaeological evidence and surviving inscriptions. They are thought to be guardian-type figures offering protection and sanctuary. Some scholars theorise that their hoods are an artistic motif indicating that the beings depicted are normally invisible, “slippery avoidance of being too-clearly defined, preferring instead to remain hidden/hooded/held in obscurity.”

Sometimes, however, the hoods appear very phallic. Sometimes the phallic imagery is overt: some Cucullati have removable hoods revealing the phallus hidden within. An exposed phallus traditionally serves as an amulet that promotes personal fertility, and magically averts death. It may also chase away ghosts and many evil spirits. Indeed, Genii Cucullati are often depicted carrying items indicating fertility, such as eggs and coin purses or martial prowess such as swords of daggers.

In Britain, their images appear in two key locations, the Cotswolds, and Northumbria – a direct correlation with the concentration of Black Monk sightings .Celtic Scholar Miranda Green wrote “The cult of the Genii Cucullati appears to have embraced profound and sophisticated belief systems” and that “such traditions did not wholly die after the coming of Christianity.” She believed that these hooded figures seem to have left an impression of supernatural power in our countryside.'

#Genii Cucullati#The hooded spirits#Romano-British culture#celtic mythology#my artwork#My pen and ink scribbles#paganblr

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Egyptian mythology, rich with gods, pharaohs, and mystical beliefs, offers a unique glimpse into ancient Egyptian culture, captivating the world for millennia. At its core lies the ‘Ka’ concept, transcending definition and embodying life’s essence. In this belief system, Ka isn’t merely a spiritual double but the life force itself, vital in life’s journey and beyond. Intertwined with Egyptians’ views on mortality, spirituality, and the afterlife, this article delves into the world of Ka, illuminating its multifaceted role in Egyptian mythology and its enduring significance. Exploring Ka helps us grasp ancient Egyptian beliefs and how these timeless concepts resonate in modern times.OriginAncient Egyptian Religion and CultureConcept TypeSpiritual Essence and Life ForceDescriptionThe Ka is the individual’s life force or spiritual double, often depicted as a twin or guardian spiritRoleBelieved to reside in the body and continue to exist after death; necessary for an individual’s journey in the afterlifeRitualsRituals and offerings were made to honor and sustain the Ka of the deceasedTombs and StatuesKa statues were placed in tombs to ensure the continued existence and well-being of the deceasedCultural SignificanceIntegral part of ancient Egyptian beliefs about the afterlife and the continuity of the soulOverview of Ka

1. Historical Context of Ka in Ancient Egypt

Emergence of Ka in Egyptian History

The concept of Ka traces its roots back to the very cradle of Egyptian civilization, emerging in the Predynastic period, around 6000-3150 BCE. This era, characterized by the formation of the first Egyptian state, saw the development of distinct religious beliefs and practices, among which the idea of Ka was fundamental. As the Egyptians’ understanding of life, death, and the afterlife evolved, so too did the conception of Ka, becoming more refined and integral during the Old Kingdom period (c. 2686–2181 BCE).

Cultural and Religious Significance of Ka

Archaeological Insights into the Understanding of Ka

The understanding of Ka is further illuminated by archaeological discoveries. Tomb inscriptions, such as those found in the pyramids and the Valley of the Kings, often reference Ka, indicating its significance in burial rites and beliefs about the afterlife. Ancient religious texts, like the Pyramid Texts and the Book of the Dead, provide a more detailed glimpse into the Egyptians’ perceptions of Ka. These texts, some of the oldest religious writings in the world, outline rituals and spells to protect and nourish the Ka, underscoring its centrality in ancient Egyptian spirituality. The consistency of these references across various dynasties and regions within Egypt attests to the widespread and enduring nature of the belief in Ka.

See alsoGeb: The Ancient Egyptian Earth God

2. The Concept of Ka

Understanding Ka in Egyptian Mythology

In the realm of Egyptian mythology, Ka represents more than just a concept; it’s an integral part of the human existence, akin to a spiritual double. It is believed that Ka is created at the moment of birth, mirroring the physical body but existing in the spiritual realm. This life force is not just a static entity; it’s dynamic, requiring nourishment and care, both in life and after death. The Ka was thought to reside in the tomb with the deceased’s body and needed offerings of food and drink to sustain itself. The preservation of the body through mummification was also crucial, as it provided a physical anchor for the Ka in the afterlife.

Ka and Comparative Mythological Concepts

The concept of a life force or a spiritual double is not unique to Egyptian mythology. Similar notions can be found in other ancient cultures. For instance, the ‘anima’ in Roman beliefs or the ‘chi’ in Chinese philosophy share resemblances with Ka, embodying the vital force or essence of life. However, the Egyptian Ka is distinct in its complex interplay with physical existence and the afterlife, setting it apart from other cultural interpretations of the soul or life essence.

Ka’s Role in the Afterlife

3. Symbolism and Representation of Ka

Depictions of Ka in Egyptian Art and Architecture

The ancient Egyptians manifested their reverence for the Ka through various artistic and architectural forms. In statues, particularly those placed in tombs or near burial sites, people found one of the most iconic representations of Ka. They believed that these statues, which often resembled the deceased, would provide a physical vessel for the Ka if someone were to destroy the mummified body. Hieroglyphs, another significant medium, frequently depict Ka as a pair of upraised arms, symbolizing the concept of embrace or protection. This imagery appears in tombs, temples, and manuscripts, serving as a visual testament to the importance of Ka.

See alsoEgyptian Pharaoh Ramses III: Hero and Builder

Symbolism Embedded in Representations of Ka

4. Ka in Egyptian Religious Practices

Rituals and Ceremonies Centered Around Ka

Ka’s Influence in the Lives of Pharaohs

The concept of Ka permeated all levels of Egyptian society, impacting both pharaohs and commoners. Pharaohs symbolized their divine right to rule through the Ka, often depicting it in royal iconography. They built temples dedicated to the Ka of deceased pharaohs, which served as centers for worship and offerings. Commoners, on the other hand, played a more personal role with their Ka, regularly making offerings to seek protection and prosperity. The belief in Ka also influenced moral and ethical behaviors, as people considered it essential to maintain a harmonious relationship with their Ka for a favorable existence and afterlife.

See alsoBastet(Bast): The Egyptian Goddess of Protection

Daily Life and Beliefs Shaped by Ka

The presence of Ka in everyday life was profound. The actions, decisions, and ethics of the Egyptians were often guided by their relationship with their Ka. The need to provide for the Ka in the afterlife influenced the construction of tombs and the accumulation of wealth and goods. Even in daily language and expressions, references to Ka were prevalent, reflecting its deep integration into the cultural and spiritual fabric of ancient Egyptian life. This omnipresence of Ka in religious, social, and personal spheres highlights its foundational role in shaping the worldview and practices of one of history’s most fascinating civilizations.

5. Modern Interpretations and Influence

Ka in Contemporary Interpretations

Influence of Ka in Modern Culture

Ka’s influence is discernible in various facets of contemporary culture, particularly in literature and film. Writers and filmmakers, inspired by the mystique of ancient Egyptian beliefs, have incorporated elements of Ka into their narratives. These references are often seen in stories exploring themes of immortality, spiritual journey, and the afterlife. By weaving Ka into their works, creators not only pay homage to this ancient belief system but also introduce it to new audiences, keeping the concept alive in popular imagination.

Relevance of Ka in Today’s Society

The study and understanding of concepts like Ka hold significant relevance in modern society. By examining these ancient beliefs, we gain insights into the human condition and our perennial quest to understand life, death, and existence. The principles underlying the concept of Ka – the importance of nurturing the soul, ethical living, and the belief in life beyond the physical – resonate with many contemporary spiritual and philosophical ideas. This relevance underscores the timeless nature of such ancient beliefs, reminding us that the pursuit of understanding life’s mysteries is a universal and enduring human endeavor.

6. Conclusion

The exploration of Ka, the ancient Egyptian concept of the life force, reveals not only the intricacies of their mythology but also the depth of their understanding of life and afterlife. Ka, central to Egyptian beliefs, was more than a spiritual entity; it was a reflection of existence, encompassing ethics, rituals, and the eternal journey of the soul. The enduring influence of Ka in modern interpretations, literature, and film highlights its universal appeal and the continuous human quest to understand the unseen aspects of life. Studying such ancient beliefs like Ka enriches our current understanding of history and culture, bridging the past with the present and offering a deeper appreciation of the complexities of human spirituality and the timeless pursuit of existential meaning.

10 notes

·

View notes

Note

Doesn't the marble bust of Alcibiades at the Capitoline museum resemble Frodo from LOTR? The hair and facial features

1. That's not actually for sure Alcibiades, the base with the inscription is a modern addition. We don't know who that is. It's also a roman copy of a late classical century greek original. There are only 2 extant depictions of Alcibiades that we know for sure are him because it was actually written on them. The severely damaged bust from aphrodisias, and the mosaic from sparta, which both are roman era works.

2. I think Frodo has much thinner lips and I'm personally not seeing it, but if it looks like him to you that's perfectly valid, I'm a little face blind anyway.

3 notes

·

View notes