Formerly known by the username "sixteenseveredhands." She/her. I'm a 33-year-old anthropologist, a former archaeology tech, a traveler, and a writer. I created this blog so that I could share info about unique archaeological discoveries and interesting/obscure bugs (especially moths); I occasionally write posts about other obscure animals, too.

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Rock Crystal Flask from Ancient Rome, c.25 BCE: this stunning little flask measures just 5.7cm (2.25 in) tall, and it was carved from a solid piece of rock crystal more than 2,000 years ago

Known as an amphoriskos, this miniature vessel was likely used as a vial for perfumed oils.

Vessels made of rock crystal were rare and highly treasured throughout the Roman world, as the Getty Museum explains:

Due to the limited sources of the material and the labor-intensive process of making the vessels, rock crystal vessels were rare and expensive luxury items in the Roman world. A small amphoriskos such as this one probably contained expensive perfumed oils. This form of flask, with angular handles and a bottom knob, was also popular in ceramic vessels of the late first century B.C.

Rock crystal was also prized for its natural beauty, resilience, and mystical significance:

Like the Greeks before them, the Romans believed that rock crystal was ice that had been hardened through intense freezing. Fittingly, such a miraculous stone was believed to have the powers of an amulet and was highly valued.

The stone's hardness made it difficult to work but also highly desirable because the finished piece possessed a glossy finish and was resistant to scratches. To hollow out the vessel, an artisan used ground emery as an abrasive. Small vessels like this multi-faceted amphoriskos took advantage of the natural elongated, hexagonal structure of the quartz mineral.

Sources & More Info:

Getty Museum: Roman Amphoriskos (Flask)

Seeking Transparency: Rock Crystal and the Nature of Artifice in Ancient Rome

Travel to Eat: Roman Perfume Bottles

#archaeology#artifact#history#anthropology#rock crystal#perfume vial#flask#roman#art#classical antiquity#vessel#amphoriskos#ancient greece#quartz#gemology#amulet

78 notes

·

View notes

Text

48,000-Year-Old Cave Painting from Indonesia: this painting shows several animals being hunted by tiny figures that are part-human and part-animal (known as therianthropes); researchers believe that this may be the earliest known depiction of mythical beings

This painting was found at Leang Bulu' Sipong 4, which is a limestone cave located on the island of Sulawesi, in Indonesia.

The panel shown here is just one part of a much larger painting that measures nearly 4.5 meters (about 15 feet) long, and it decorates the wall of a hidden chamber that was discovered back in 2017. The full-length painting portrays six animals, including two wild pigs and four anoas (which are small, buffalo-like creatures that are endemic to Indonesia). All of the animals are shown being captured, hunted, and/or pursued by tiny figures that appear to be part-human and part-animal; their vaguely human-like bodies are depicted with animalistic features such as tails, beaks, muzzles/snouts, lizard-like torsos, and horns.

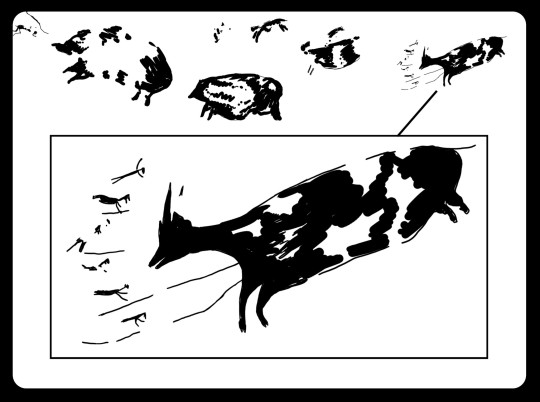

Above: a digital tracing of the full-sized painting, with one of the anoas and several human-like figures magnified

It's possible that some of these animal-like traits represent masks, headdresses, or costumes, but several of the figures also exhibit more extreme features that cannot be produced by simple costumes. Researchers argue that the animal-like costumes would also be useless and impractical as hunting props, given that they mostly seem to mimic small animals like birds and lizards.

Above: two of the figures that are described as therianthropes, both of which seem to be using spears or ropes to subdue the much larger anoa

The original analysis of this painting in 2019 indicated that it was created over 43,900 years ago, but further testing in 2024 revealed that it was created even earlier, dating back to at least 48,000 years ago -- which makes this the world's second-oldest example of figurative art (i.e. artwork that depicts real or recognizable subjects, such as humans or animals).

It's unclear whether or not the animal-like figures actually represent therianthropes, but if they are therianthropic, as archaeologists speculate, then this painting would be the world's oldest known depiction of mythical beings, and it would constitute the earliest known evidence of spiritual or supernatural thinking. It is more than 8,000 years older than the famous Löwenmensch ("lion-man") carving from Germany, which has long been recognized as the world's oldest depiction of a therianthrope.

According to this article:

For whoever painted these figures, they represented much more than ordinary human hunters. One appears to have a large beak while another has an appendage resembling a tail. In the language of archaeology, these are therianthropes, or characters that embody a mix of human and animal characteristics.

"The images of therianthropes may also represent the earliest evidence for our capacity to conceive of things that do not exist in the natural world, a basic concept that underpins modern religion,” said Adam Brumm, study co-author and associate professor at the Australian Research Centre for Human Evolution. “Therianthropes occur in the folklore or narrative fiction of almost every modern society, and they are perceived as gods, spirits or ancestral beings in many religions worldwide.”

These interpretations are speculative, however, and the inspiration for the painting, as well as its significance to the humans who created it, is likely to remain a mystery.

Archaeologists have been aware of Sulawesi's abundant cave art since the 1950's, but dating techniques were not used on the paintings until 2014. For decades, it was assumed that the artwork was less than 10,000 years old, but when animal paintings and hand stencils from seven different caves were finally analyzed in 2014, researchers were shocked to discover that some of the artwork was created more than 39,900 years ago -- predating most of the world's earliest known cave paintings. Since then, archaeologists have discovered and/or dated many other cave paintings from Sulawesi that date back to more than 40,000 to 51,200 years ago.

These discoveries firmly contradict the traditional (and deeply eurocentric) assumptions that had previously been made about the origins of artistic expression, as this article explains:

Previously, the oldest known cave art was thought to have first appeared in Europe 40,000 years ago, showcasing abstract symbols. By 35,000 years ago, the art became more sophisticated, showing horses and other animals.

These latest finds in Indonesia have challenged a long-standing belief that artistic expression – and the cognitive leap that may have accompanied it – began in Europe.

It’s now thought that the capability to create figurative art either emerged before Homo sapiens migrated out of Africa and headed for Europe and Asia more than 60,000 years ago, or that it emerged more than once as humans spread around the globe.

Unfortunately, many of the cave paintings in Sulawesi and other parts of Indonesia are now rapidly crumbling away as a result of climate change. The limestone surfaces of the cave walls are peeling away at an alarming rate, erasing large sections of the paintings in the process; in some caves, patches of artwork measuring 2-3cm wide are vanishing every few months.

Sources & More Info:

The Guardian: Earliest Known Cave Art by Modern Humans Found in Indonesia

Scientific American: Is This Indonesian Cave Painting the Earliest Portrayal of a Mythical Story?

National Geographic: Ancient Cave Art May Depict the World's Oldest Hunting Scene

The Leakey Foundation: Indonesian Cave Paintings Show the Dawn of Imaginative Art

Nature: Earliest Hunting Scene in Prehistoric Art

Nature: Narrative Cave Art in Indonesia by 51,200 Years Ago

The New York Times: Mythical Beings May be Earliest Imaginative Cave Art by Humans

Science: World's Oldest Hunting Scene Shows Half-Human, Half-Animal Figures -- and a Sophisticated Imagination

Smithsonian Magazine: A Journey to the Oldest Cave Paintings in the World

Art Net: Some of the Oldest and Most Revered Cave Paintings in the World Are Under Extreme Threat Due to Climate Change

Nature: Humanity's Oldest Art is Flaking Away

#archaeology#artifact#history#anthropology#cave painting#prehistoric art#sulawesi#indonesia#leang bulu sipong#art#painting#therianthropes#mythology#spirituality#folklore#humanity#mythical figures#or just weird looking art#probably a little bit of both

102 notes

·

View notes

Text

45,500-Year-Old Painting of a Warty Pig from the Island of Sulawesi, in Indonesia: this is one of the world's oldest examples of figurative art, and one of the earliest known depictions of an animal

This painting was found at Leang Tedongnge, which is a limestone cave located on the island of Sulawesi, in Indonesia. It was created at least 45,500 years ago, but it's still remarkably well-preserved.

Above: a close-up of the pig's face, showing a pair of "spiky" head crests and preorbital facial warts, which are characteristic features of the Sulawesi warty pig (Sus celebensis), a species that still inhabits the forests of Sulawesi

The painting was created using dark red mineral pigments; it measures 136cm long (about 4.5 feet) from tail-to-snout, and two hand stencils mark the wall just above the pig's haunches. Partial figures from at least two other pigs are visible on the wall several meters away.

Above: two additional paintings are located toward the right side of the wall, but only fragments of the pigs' faces and shoulders remain

The caves of Sulawesi contain the world's oldest known examples of figurative art (i.e. artwork that depicts real or recognizable subjects, like animals and human beings); the oldest figurative painting in the world is a 51,200-year-old depiction of a warty pig with three human-like figures, from the cave of Leang Karampuang. Unfortunately, that painting is much more faded and more badly damaged.

Above: this 51,200-year-old painting from Leang Karampuang is faded and badly damaged, but it depicts another pig interacting with several anthropomorphic figures; this is currently recognized as the world's oldest surviving example of figurative art

Warty pigs appear in over 87% of the prehistoric animal paintings that have been documented in Sulawesi. Many of the other paintings depict a small, buffalo-like creature called an anoa (Bubalus sp.), which is a type of wild bovid that is also endemic to Indonesia. Both animals can still be found on the island of Sulawesi.

Above: anoas depicted in the cave paintings of Leang Timpuseng (top) and Leang Bulu' Sipong (bottom); the painting from Leang Bulu' Sipong dates back to at least 48,000 years ago, making it the second-oldest figurative painting in the world

Archaeologists have been aware of Sulawesi's cave art since the 1950's, but dating techniques were not used on the paintings until 2014. For decades, it was assumed that the artwork was less than 10,000 years old, but when animal paintings and hand stencils from seven different caves were finally analyzed in 2014, researchers were shocked to discover that some of the artwork was created more than 39,000 years ago. Since then, archaeologists have discovered and/or dated many other cave paintings from Sulawesi (and some from the neighboring island of Borneo) that date back to between 35,000 and 51,200 years ago.

Above: the painting from Leang Tedongnge

When this particular painting was discovered in 2017, it briefly qualified as the world's oldest example of figurative art and the oldest known depiction of an animal, but it has since been surpassed by two other cave paintings from other sites in Sulawesi. This is still the third-oldest figurative painting in the world.

These discoveries firmly contradict the traditional (and deeply eurocentric) assumptions that were once made regarding the origins of artistic expression, as this article explains:

Previously, the oldest known cave art was thought to have first appeared in Europe 40,000 years ago, showcasing abstract symbols. By 35,000 years ago, the art became more sophisticated, showing horses and other animals.

These latest finds in Indonesia have challenged a long-standing belief that artistic expression – and the cognitive leap that may have accompanied it – began in Europe.

It’s now thought that the capability to create figurative art either emerged before Homo sapiens migrated out of Africa and headed for Europe and Asia more than 60,000 years ago, or that it emerged more than once as humans spread around the globe.

And this article adds:

The geographic location of the painting is significant. Although experts have long recognized that humans originated in Africa, “Europe was once thought of as a ‘finishing school’ for humanity,” says archaeologist April Nowell of the University of Victoria in Canada, because all the oldest known examples of art and other sophisticated behaviors were found there. But in reality, the pattern of discoveries just reflected the disproportionate amount of archaeological research that was being carried out in Europe, especially in France.

“This new discovery adds to an already rich record of early and varied rock art from [Indonesia and Australia] and underscores the importance of conducting research outside Europe,” Nowell says.

Unfortunately, many of the cave paintings in Sulawesi and other parts of Indonesia are now rapidly crumbling away as a result of climate change. The limestone surfaces of the cave walls are peeling away at an alarming rate, erasing large sections of the paintings in the process; in some caves, patches of artwork measuring 2-3cm wide vanish every few months.

Sources & More Info:

Science Advances: Oldest Cave Art Found in Sulawesi

CNN: A Warty Pig Painted on a Cave Wall 45,500 Years Ago is the World's Oldest Depiction of an Animal

Smithsonian Magazine: A Journey to the Oldest Cave Paintings in the World

Nature: Narrative Cave Art in Indonesia by 51,200 Years Ago

Nature: Pleistocene Cave Art from Sulawesi, Indonesia

Art Net: Archaeologists Have Discovered a Pristine 45,000-Year-Old Cave Painting of a Pig that May be the Oldest Artwork in the World

Art Net: Some of the Oldest and Most Revered Cave Paintings in the World Are Under Extreme Threat Due to Climate Change

#archaeology#artifact#history#anthropology#prehistoric art#cave painting#warty pig#leang tedongnge#sulawesi#indonesia#art#painting#eurocentrism#conservation#art history#pigs#hand stencils#pleistocene#all hail the warty pig

280 notes

·

View notes

Text

Frother Moths (Genus Amerila): when these moths feel threatened, they secrete a frothy yellow substance from the glands on their thorax, producing chemicals that are distasteful to predators

Above: Amerila astreus

Moths of the genus Amerila are commonly known as "frother moths," because they can produce a pungent, unpalatable froth in order to deter predators. A distinctive "sizzling" or "hissing" sound is also emitted as the frothy substance bubbles out.

Above: Amerila crokeri, commonly known as Croker's frother moth (top), and Amerila rubripes, also known as Walker's frother moth (bottom)

The substance, which has a bright yellow or orange appearance, is secreted from the prothoracic glands located near the base of each wing, just behind the moth's eyes.

As this article explains:

If molested, resting adults produce quantities of a frothy, orange fluid from their prothoracic glands, accompanied by a sizzling sound. The froth not only has an aversive odor to humans but also contains PAs [pyrrolozidine alkaloids] which are likely taste-repelling. This phenomenon applies to all the Amerila and has been recorded from other Arctiids including Creatonotos.

Above: close-up of Amerila crokeri secreting its bright yellow froth

The adult moths are pharmacophagous, obtaining the aversive chemicals that are used to create their froth by ingesting plants that contain toxic/noxious compounds. Those compounds are then sequestered within the moth's body, where they are repurposed as a defensive secretion.

Above: Amerila astreus

The genus Amerila contains dozens of documented species, all of which are known to possess this defense mechanism. They are widely distributed throughout many different parts of the world; depending on the species, they can be found in the Himalayas, Indochina, Southeast Asia, Melanesia, Australia, or Central/Southern Africa.

Above: Amerila crokeri

Sources & More Info:

Metamorphosis Australia: The Australian Arctiid Moths

Metamorphosis Australia: Weird and Wonderful Moths

Australian Lepidoptera: Amerila crokeri

Entomo Brasilis: Defensive Froth in Arctiidae Species in the Rio Grande do Sul State, Brazil (PDF)

Moths of Australia: Adult Adaptations for Survival

Advances in Insect Chemical Ecology: The Curious Relationship Between Tiger Moths and Plants Containing Pyrrolozidine Alkaloids (PDF)

Neotropical Entomology: A Fieldwork-Oriented Review and Guide to PA-Pharmacophagy

#entomology#lepidoptera#arthropods#frother moth#genus amerila#moths#bugs#insects#defense mechanisms#chemical defense#animal facts#colorful moths#the frothy pom pom defense

136 notes

·

View notes

Text

Snake-Mimicking Sphinx Moth (Hemeroplanes triptolemus): the caterpillars of this species are able to mimic snakes by turning upside-down and inflating the area around their head

It's very common for moths to engage in mimicry during the larval stage of their development, and their caterpillars are often known to mimic snakes. In most cases, they'll simply mimic the snake's eyes (or eye) and its general morphology, but there are a few species that take their disguises to a much higher level, mimicking the snake's eyes, scaly texture, coloration, posture, and even its behavior with such a startling degree of accuracy that the tiny, harmless caterpillars are often mistaken for actual snakes.

Hemeroplanes triptolemus is probably the most famous example of this.

Above: a caterpillar of the species Hemeroplanes triptolemus displaying its defensive posture

This species of sphinx moth can be found in the rainforests of Central and South America. When threatened, the caterpillar suspends itself from a twig, turns its body over to expose its underbelly, tucks in its legs, and inflates the anterior segments of its body in order to mimic the shape of a serpent's head. As the body segments expand, several markings on each side of the caterpillar's body are exposed, mimicking the eyes and nostrils of a snake.

Above: the caterpillar is shown hanging upside-down; its actual head is visible near the tip of the "snake nose"

As this article explains:

At the slightest hint of danger—be it a stooping bird or pouncing lizard—the sphinx moth caterpillar begins its masquerade. Dangling from a twig, it reveals an underside patterned in faux snakeskin and eyespots that appear to glisten. By sucking in air through tiny holes in its surface, the caterpillar inflates its head to create the illusion of a triangular skull swollen with venom glands. If the shape of a deadly snake isn’t enough to startle away a hungry predator, the caterpillar will lunge as if to strike. And despite the larva’s comical lack of any actual weaponry, the strategy appears to be effective.

Above: detailed photos of the "snake's head"

This disguise is only present in the final instar, which is the last stage of development before the caterpillar undergoes pupation and then matures into an adult moth.

Above: the adult form of Hemeroplanes triptolemus

As I've said before, moths are some of the very best mimics in the world. I've also written posts about wasp-mimicking moths, moths that mimic jumping spiders, a moth that can mimic a broken birch twig, a moth that disguises itself as two flies feeding on bird poop, another snake-mimicking moth caterpillar, a moth that mimics a curled-up leaf, a moth that mimics a cuckoo bee, moths that mimic hornets and bumblebees, and a moth that can mimic the leaves of a poplar tree.

Sources & More Info:

BioGraphic: Snake Fake

National Geographic: This Harmless Caterpillar Looks Like a Pit Viper

Animal Behaviour: Defensive Posture and Eyespots Deter Avian Predators from Attacking Caterpillar Models

University of Nebraska: Mimicry in Insects (PDF)

Ecology and Evolution: Outstanding Issues in the Study of Antipredator Defenses

#entomology#arthropods#lepidoptera#snake-mimicking sphinx moth#hemeroplanes triptolemus#sphinx moths#caterpillars#moths#sphingidae#hawkmoths#mimicry#animal camouflage#evolution#defense mechanisms#animal facts#bugs#insects#mind-blowing moths

113 notes

·

View notes

Text

Yellowjacket-Mimicking Moth: this is just a harmless moth that mimics the appearance and behavior of a yellowjacket/wasp; its disguise is so convincing that it can even fool actual wasps

This species (Myrmecopsis polistes) may be one of the most impressive wasp-mimics in the world. The moth's narrow waist, teardrop-shaped abdomen, black-and-yellow patterning, transparent wings, smooth appearance, and folded wing position all mimic the features of a wasp. Unlike an actual wasp, however, it does not have any mandibles or biting/chewing mouthparts, because it's equipped with a proboscis instead, and it has noticeably "feathery" antennae.

There are many moths that use hymenopteran mimicry (the mimicry of bees, wasps, yellowjackets, hornets, and/or bumblebees, in particular) as a way to deter predators, and those mimics are often incredibly convincing. Myrmecopsis polistes is one of the best examples, but there are several other moths that have also mastered this form of mimicry.

Above: Pseudosphex laticincta, another moth species that mimics a yellowjacket

These disguises often involve more than just a physical resemblance; in many cases, the moths also engage in behavioral and/or acoustic mimicry, meaning that they can mimic the sounds and behaviors of their hymenopteran models. In some cases, the resemblance is so convincing that it even fools actual wasps/yellowjackets.

Above: Pseudosphex laticincta

Such a detailed and intricate disguise is unusual even among mimics. Researchers believe that it developed partly as a way for the moth to trick actual wasps into treating it like one of their own. Wasps frequently prey upon moths, but they are innately non-aggressive toward their own fellow nest-mates, which are identified by sight -- so if the moth can convincingly impersonate one of those nest-mates, then it can avoid being eaten by wasps.

Above: Pseudosphex laticincta

I gave an overview of the moths that mimic bees, wasps, yellowjackets, hornets, and bumblebees in one of my previous posts, but I felt that these two species (Myrmecopsis polistes and Pseudosphex laticincta) deserved to have their own dedicated post, because these are two of the most convincing mimics I have ever seen.

Above: Pseudosphex sp.

I think that moths in general are probably the most talented mimics in the natural world. They have so many intricate, unique disguises, and they often combine visual, behavioral, and acoustic forms of mimicry in order to produce an uncanny resemblance.

Several of these incredible mimics have already been featured on my blog: moths that mimic jumping spiders, a moth that mimics a broken birch twig, a moth caterpillar that can mimic a snake, a moth that disguises itself as two flies feeding on a pile of bird droppings, a moth that mimics a dried-up leaf, a moth that can mimic a cuckoo bee, and a moth that mimics the leaves of a poplar tree.

Moths are just so much more interesting than people generally realize.

Sources & More Info:

Journal of Ecology and Evolution: A Hypothesis to Explain Accuracy of Wasp Resemblances

Entomology Today: In Enemy Garb: A New Explanation for Wasp Mimicry

iNaturalist: Myrmecopsis polistes and Pseudosphex laticincta

Transactions of the Entomological Society of London: A Few Observations on Mimicry

#entomology#arthropods#lepidoptera#yellowjacket-mimicking moth#wasp-moth#clearwing moths#animal camouflage#myrmecopsis polistes#pseudosphex laticincta#pseudosphex aequalis#moths#insects#bugs#mimicry#evolution#hymenopteran mimics#defense mechanisms#animal facts#wasps#yellowjackets#moths are amazing#and wildly underrated

9K notes

·

View notes

Text

Sculpture of a Woman with Four Children, from Mali, c.1100-1450 CE: this sculpture was created in the ancient city of Djenné-Djenno

Created during the 12th-15th centuries CE, this sculpture depicts a woman sitting cross-legged on the ground, with two children on her lap and two more clinging to her back. Scarification patterns are visible on the woman's temples, and there is a thick, undulating line running from her forehead to the nape of her neck, likely representing a serpent.

As this article explains:

Snakes on Inner Niger Delta sculptures are a common element and should be seen as a positive iconographic component. They represent control of a potentially dangerous benevolent power that must be tamed, domesticated, nourished, and satisfied so it will continue to provide protection.

This is one of the many terracotta sculptures that were produced in Djenné-Djenno, located in the Niger River Valley of Mali, in West Africa; Djenné-Djenno sits just to the south of the Medieval city of Djenné, which is still a major center of Islamic scholarship.

The ancient city of Djenné-Djenno dates back to at least 250 BCE, making it one of the oldest cities in West Africa. For centuries, it also served as one of the largest urban centers/trading hubs in the region, with a peak population of about 20,000 people. The city began to decline in the 9th century CE, when residents (and trade) began moving northward to the nearby city of Djenné, which had just recently been founded by Muslim traders. Djenné-Djenno was ultimately abandoned by the end of the 15th century.

Unfortunately (and unsurprisingly), most of the artifacts from Djenné-Djenno were looted or destroyed by colonizing forces during the 19th-20th centuries. Some of those artifacts have been repatriated in recent years, and there are ongoing efforts to return more of them.

Why Western museums should return African artifacts.

Sources & More Info:

Yale University Art Gallery: Female Figure with Four Children

World History Encyclopedia: Djenné-Djenno

Tribal Art: Scrofulous Sogolon (PDF)

ArtNews: Museum of Fine Arts Boston to Return Terra-Cotta Figures from Mali in Latest Restitution Efforts

CBS: African Nations Want their Stolen History Back, and Experts Say it's Time to Speed up the Process

Fair Observer: It is Now Time for the West to Return African Art

#archaeology#artifact#history#anthropology#dogon#djenne-djenno#mali#west africa#medieval art#sculpture#art#motherhood#children#djenne#african art#african history#repatriation#inner niger valley#terracotta#conservation#timbuktu

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

Child's Sock from Egypt, c.250-350 CE: this colorful sock is nearly 1,700 years old

This sock was discovered during excavations in the ancient city of Oxyrhynchus. It was likely created for a child during the late Roman period, c.250-350 CE.

Similar-looking socks from late antiquity and the early Byzantine period have also been found at several other sites throughout Egypt; these socks often have colorful, striped patterns with divided toes, and they were crafted out of wool using a technique known as nålbinding.

Above: a similar child's sock from Antinoöpolis, c.250-350 CE

The sock depicted above was created during the same period, and it was found in a midden heap (an ancient rubbish pit) in the city of Antinoöpolis. A multispectral imaging analysis of this sock yielded some interesting results back in 2018, as this article explains:

... analysis revealed that the sock contained seven hues of wool yarn woven together in a meticulous, stripy pattern. Just three natural, plant-based dyes—madder roots for red, woad leaves for blue and weld flowers for yellow—were used to create the different color combinations featured on the sock, according to Joanne Dyer, lead author of the study.

In the paper, she and her co-authors explain that the imaging technique also revealed how the colors were mixed to create hues of green, purple and orange: In some cases, fibers of different colors were spun together; in others, individual yarns went through multiple dye baths.

Such intricacy is pretty impressive, considering that the ancient sock is both “tiny” and “fragile."

Given its size and orientation, the researchers believe it may have been worn on a child’s left foot.

Above: another child's sock from Al Fayyum, c.300-500 CE

The ancient Egyptians employed a single-needle looping technique, often referred to as nålbindning, to create their socks. Notably, the approach could be used to separate the big toe and four other toes in the sock—which just may have given life to the ever-controversial socks-and-sandals trend.

Sources & More Info:

Manchester Museum: Child's Sock from Oxyrhynchus

British Museum: Sock from Antinoupolis

Royal Ontario Museum: Sock from Al Fayyum

Smithsonian Magazine: 1,700-Year-Old Sock Spins Yarn About Ancient Egyptian Fashion

The Guardian: Imaging Tool Unravels Secrets of Child's Sock from Ancient Egypt

PLOS ONE Journal: A Multispectral Imaging Approach Integrated into the Study of Late Antique Textiles from Egypt

National Museums Scotland: The Lost Sock

#archaeology#artifact#history#anthropology#child's sock#ancient textiles#ancient egypt#roman egypt#fabric arts#knitting#fashion#naalebinding#art#classical antiquity#children in archaeology#natural dyes#wool#yarn#ancient clothing#children#roman#sewing#egyptology#cute little stripy socks

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Hedgehog on Wheels, from Iran, c.1500-1100 BCE: this 3,500-year-old figurine of a hedgehog on a wheeled platform was found with several similar artifacts depicting animals on carts

The body of the hedgehog measures just 2.8cm long (about 1.1 inch) and was crafted out of limestone, while the cart was made using a bitumen compound. The hedgehog's feet are attached to four round sockets located at the front of the cart.

There are eight more empty sockets at the back of the platform, and their pattern/spacing could indicate that two smaller hedgehogs were originally mounted on the cart just behind this larger one, like a pair of baby hedgehogs following their mother.

The hedgehog was found with another figurine depicting a lion on a wheeled platform. Both of these artifacts were unearthed at the Temple of Inshushinak, located in what was once the ancient city of Susa; they date back to the Middle Elamite Period, c.1500-1100 BCE.

Their original function/significance is still widely debated, with some experts arguing that they were created as toys, while others argue that they were used as votive offerings. Their presence in the temple suggests that they likely had some cultural/ritual significance, but it's important to note that those two explanations may not be mutually exclusive -- some artifacts were used as both toys and ritual objects.

The distinction between those two terms is not necessarily as clear-cut as it seems, because toys are often incoporated into ritual contexts (as offerings or grave goods, for example) and they can also be used to familiarize children with rituals and religious beliefs.

Regardless of why they were made, they are strikingly adorable.

Sources & More Info:

The Louvre: Hedgehog Toy & Lion Toy

Metropolitan Museum of Art: Artifacts from The Royal City of Susa

Journal of the British Institute of Persian Studies: Probing the Margins in Search of Elamite Children

Portrait of a Plaything: Hedgehog

Cambridge University Press: Ritual, Play, and Belief in Evolution and Early Human Societies

#archaeology#artifact#history#anthropology#hedgehog on wheels#toys#votive offerings#susa#elamite#iran#ancient art#hedgehog#ancient toys#ritual artifacts#children in archaeology#art#sculpture#animal figurine#ancient near east

116 notes

·

View notes

Text

Life-Sized Mortuary Doll from Siberia, c.250 CE: a small pouch filled with cremated human remains was tucked into the body of this mannequin, which was then stuffed with grass, dressed in furs, and buried

The mannequin measures about 1.5 meters (nearly 5 feet) tall, and it was crafted out of leather, fur, woollen fabric, tendon thread, silk, and grass. This is one of several mortuary dolls that have been found at the burial complex known as Oglakhty cemetery, which is located in the Oglakhty mountains of southern Siberia.

The mannequin's face was created from a patch of red woollen fabric; a rolled-up piece of leather was tucked beneath that patch in order to create the shape of the nose, while leather flaps were used to form the ears. Several black lines were also drawn across the face using charcoal.

The mannequin was positioned with its head resting atop a leather cushion filled with grass and reindeer fur.

Oglakhty cemetery is associated with the Tashtyk culture of southern Siberia. This article describes their unique burial practices, which often included a mix of mummification and cremation rituals:

The communities belonging to this group left numerous burial sites with an expressive funeral rite famous for its tradition of funeral masks and ‘dummies’: leather-made models of human bodies up to 1.5m in length, stuffed with grass, and containing charred human bones.

Of special interest is the fact that different rites were used to bury individuals in the same grave: the mummies and dummies both contained human bones. Remains of the mummies, i.e. dry bodies with trepanned skulls and faces covered with gypsum masks were lying side by side with the dummies.

And as this article notes:

These mannequins or so-called ‘dolls’ are the only surviving examples of burials of this type.

It's believed that the mannequins are dressed in clothing that was originally worn by the dead people they represent. Some of the mannequins also have plaits of human hair that were likely taken from the dead just prior to cremation; the hair was then used to form neatly-braided hairpieces that were typically placed upon the mannequins' heads.

Many of the graves at Oglakhty cemetery exhibit a peculiar mix of both inhumation and cremation. That blend of rituals is often attributed to the arrival of peoples/traditions from other regions, and the cultural diffusion that gradually occurred as a result:

Different ways of burying people in the same graves in the early Tashtyk cemeteries may reflect their different origins: descendants of local population and immigrants living and buried alongside each other.

Sources & More Info:

Antiquity: Pastoralists and Mobility in the Oglakhty Cemetery of Southern Siberia

Masters of the Steppe: Mummies and Mannequins from the Oglakhty Cemetery in Southern Siberia

Quarternary International: New Results of Radiocarbon Dating from the Oglakhty Cemetery

Research Square: First Ancient DNA Analysis of Mummies from the Post-Scythian Oglakhty Cemetery

Archeotravelers: The Face Hidden Behind the Mask

Great Sites of the Ancient World: Siberia's Oglakhty Mountains

#archaeology#artifacts#history#anthropology#oglakhty#mortuary dolls#mannequins#cremation#mummification#burial practices#siberia#russia#funerary rites#rituals#tashtyk#scythians#cultural diffusion#mummies and dummies

66 notes

·

View notes

Text

This is Jinx: my brother found her after she was abandoned at a local park, but he scooped her up and brought her home; she has a neurological disorder that impairs her ability to walk properly, and thanks to a birth defect, she doesn't have any teeth

In addition to the neurological disorder and the dental defect, Jinx also has some minor deformities in one of her eyes, her tail is kinked, she's a runt, and she apparently had a botched spay procedure at some point in her life. She's mostly just heart-stoppingly adorable, though.

Here is a video of her trying to be ferocious:

My brother brought her home about three years ago, after he found her sitting in the parking lot of a local park. When he first approached her, she tried to run away, but she immediately fell over and then struggled to get back up again. My brother just assumed that she was injured, so he scooped her up and carried her back home.

When we took her to the vet, we learned that she wasn't injured, but that her balance issues are likely the result of a disorder known as cerebellar hypoplasia (CH), which is sometimes referred to as "wobbly cat syndrome." It's a developmental disorder in which the cerebellum (the part of the brain that controls movement and balance) fails to develop properly in utero. The disorder affects her ability to stand, walk, jump, etc.

Cats with CH can have mild, moderate, or severe disabilities, but Jinx's impairments are on the mild/moderate side of that scale -- she can walk, but she is very uncoordinated, and she frequently staggers, sways, or tips over, especially when she's startled or in distress. She then has a lot of trouble regaining control of her limbs and getting back up again, which sort of makes her look like a "fainting goat." It's hard for her to keep her head steady, so she repeatedly "bops" her nose against anything that she's trying to sniff or eat.

The bobbing motion means that she is a very messy eater, and that issue is made even worse by the fact that she doesn't have any teeth and she generally forgets to close her mouth. Her toothlessness is the result of another congenital defect known as oligodontia, meaning that her teeth failed to develop, aside from a couple of tiny, mishapen "toothlets" near the front of her mouth.

She also seems to have had a botched spay procedure at some point, because there's evidence that another vet attempted to spay her (and she has the scar to prove it) but she still goes into heat at erratic intervals, and it seems to cause her much more distress than you'd normally see in a healthy cat. Our veterinarian suspects that the person who performed her surgery accidentally left behind some of the ovarian tissue, thereby wreaking havoc on her hormones.

Given the circumstances, we're pretty sure that someone deliberately abandoned her. The lot in which she was found is located in the middle of a very large park, and it's surrounded by several acres of pine forest, densely packed thickets, thorns, tall grass, and muddy terrain. Given her mobility issues, there's no way that she could have traversed all of those obstacles on her own, especially not without getting at least a little bit disheveled and dirty, but her fur was still clean and well-groomed when we found her...which means that someone must have driven her there and then left.

She's an absolute sweetheart, though. She has some peculiar habits, but she is still incredibly affectionate. She literally comes running to greet me every time I open my bedroom door, and she does the same thing with my brother.

She always sleeps next to my Dad at night, too, and as soon as he goes to bed, she follows him in and says "goodnight" to him by snuggling up to his neck, kneading his shoulder, and kissing his face (tho her kisses are kind of messy, because the toothlessness means that she drools a lot and almost always leaves her mouth hanging open).

Edit: Jinx was diagnosed with CH, but there's a possibility that her symptoms are the result of a congenital vestibular dysfunction instead, because both disorders are known to cause issues with balance, movement, and posture, but she has some symptoms that are more closely associated with CH, and others that are more closely associated with vestibular disorders. CH is still the likelier culprit, tho.

#Jinx#pets#cute animals#cerebellar hypoplasia#rescue#cats#not an arthropod#not an artifact#just a toothless little kitty#sticking her tongue out#and blepping with the best of them

65 notes

·

View notes

Text

Moss-and-Lichen Katydid: these katydids are covered in cryptic markings and textures that allow them to blend in with their mossy, lichen-covered habitat, and their wings even mimic the appearance of a twig

The katydids of this genus (Anaphidna) can be found in the rainforests of Central and South America. They have cryptic features that mimic the mossy, lichen-covered environments in which they live -- their bodies are covered in green, brown, and white markings that are accented by bumpy, moss-like features, and their long, slender wings are usually held upward at a 45-degree angle in order to mimic the shape of a twig.

As this article notes:

These katydids fly well and probably live in the canopy, perhaps on trunks and mossy branches, where the camouflage should be particularly effective.

The moss-and-lichen mimic katydids of the group treated here are easily recognized by their long and slender wings held upward at an almost 45-degree angle. They live in rainforests of central and northern South America, with one species ranging southward to subtropical forest in NE Argentina.

Sources & More Info:

Journal of Orthoptera Research: The Group Paraphidniae, with Three New Species from Guatemala and Ecuador

iNaturalist: Genus Anaphidna

Zoosystematica Rossica: Review of the Neotropical Genus Paraphidnia

Orthoptera Species File: Anaphidna

#entomology#orthoptera#arthropods#katydids#anaphidna#paraphidnia#moss-and-lichen katydid#insects#bugs#cryptic#mimicry#animal camouflage#evolution#animal facts

759 notes

·

View notes

Text

Giant Antlions (Palpares immensus): these enormous antlions have been known to attack geckos and other small reptiles

The images above depict the larval stage of Palpares immensus, which is one of the largest antlion species in the world.

This article provides more information about the unusual behavior of this species:

The larvae live freely in sand and are ambush hunters. They are voracious predators and feed mainly on other arthropods, but have been known to attack geckos and, in one case a small adder. They are unable to feed on these reptiles and usually die as a result of not being able to extract their jaws from the vertebrate prey.

These antlions can be found in sandy, arid environments throughout southern Africa.

The adult form of Palpares immensus is also depicted in the images below:

Sources & More Info:

Biodiversity and Development Institute: Palpares immensus

Global Biodiversity Information Facility: P. immensus

Animal Life: Giant Antlion Larva

What's That Bug?: Uncovering Antlion Habitats

#entomology#neuroptera#arthropods#giant antlion#palpares immensus#antlions#baby graboids#larvae#insects#bugs#owlflies#lacewings#animal facts#nature is weird#and also terrifying

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Palmetto Tortoise Beetle: the larvae of this species produce long, thin strands of feces that are gradually woven together to form protective "fecal shields" around their bodies

During its larval stage, the Palmetto tortoise beetle (Hemisphaerota cyanea) uses its own feces to create a defensive layer known as a "fecal shield" or "fecal thatch."

As this article explains:

Most remarkable, perhaps, is the fecal “thatch” of Hemisphaerota cyanea. In the larva of this beetle, the feces are emitted in strands, which, as they build up over the course of larval life, form a loose assemblage that totally hides the larva from view.

The construction of the "fecal thatch" begins almost immediately after the larva hatches. Each larva begins to feed within minutes of hatching, and the very first fecal strands emerge from its anal turret just a few minutes later. Subsequent strands are then produced in quick succession, and they begin to accumulate around the larva's body; as each strand emerges, it is made to curve around the larva's left or right side depending on whether the anal turret is flexed to the left or right. The direction of the curve usually alternates from one strand to the next, ensuring that a nest-like structure is formed around the larva's body.

As they emerge, the fecal strands are gathered together and then cemented into place with the help of an anatomical feature known as a caudal fork. Once an individual strand has been extruded to its full length, the anal turret is rotated upward until it comes into contact with the caudal fork, and the larva then pinches off the strand while secreting a droplet of "glue," which effectively cements each fecal strand into place against the caudal fork.

It generally takes about 12 hours for the larva to finish building its very own "fecal shield."

As an adult, the Palmetto tortoise beetle has another unusual defense mechanism: its tarsi (i.e. feet) are each lined with 10,000 tiny adhesive bristles, and when the beetle is attacked, it can press its feet flat against the surface of a leaf and secrete an oil that allows it to adhere to that surface with an enormous amount of strength. The adhesive mechanism is strong enough to resist pulling forces that are up to 60 times greater than the beetle's own weight for a full 2 minutes; it can resist even greater forces (up to 230 times greater than the beetle's own weight) for shorter periods of time.

According to this article from the University of Florida:

Each of the greatly enlarged tarsi is equipped with approximately 10,000 adhesive bristles. Each bristle has two terminal pads. When walking, only a few of the bristles touch the leaf surface. However, when attacked by a predator, the beetle puts all or nearly all of the bristles in contact with the surface and secretes oil onto the pads. With the adhesive force created by the oil between the leaf surface and tarsi, the beetle is able to clamp its hemispherical shell down tightly against the leaf and has been demonstrated to withstand pulling forces of approximately 60 times its own weight for up to two minutes. This time period is sufficient to thwart the efforts of predatory ants attempting to pry the beetle from the leaf.

Palmetto tortoise beetles are native to the southeastern United States, and they're especially common in Florida (which is why they're also known as Florida tortoise beetles).

Sources & More Info:

Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences: Defensive Use of a Fecal Thatch by a Beetle Larva (Hemisphaerota cyanea)

Earth Touch News Network: By the Power of the Poop-Shield: Beetle Defenses of the Faecal Kind

Cornell Chronicle: Fecal Defense: This Beetle Uses 'Overhead Sewer System' to Ward off (most) Predators, Cornell Biologists Discover

Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences: Defense by Foot Adhesion in a Beetle (Hemisphaerota cyanea)

University of Florida: Palmetto Tortoise Beetle

Bug Guide: Hemisphaerota cyanea

#entomology#arthropods#coleoptera#palmetto tortoise beetle#hemisphaerota cyanea#insects#beetles#bugs#animal facts#tortoise beetles#larvae#fecal shield#evolution#defense mechanisms#nature is weird

125 notes

·

View notes

Text

African Woolly Chafers (Genus Sparrmannia): these beetles have a uniquely "fluffy" appearance, thanks to the long, fur-like setae that covers their bodies

Beetles of the genus Sparrmannia are widely distributed throughout the arid regions of southern Africa. They have very distinctive features, with large, plump bodies and tawny-colored "fur," and some species can measure up to 25mm (nearly 1 inch) long.

They generally hide in underground burrows during the day, and emerge only at night, when the desert is substantially cooler. The dense layer of "fur" acts as insulation, which allows the beetles to remain active at night, even when the temperatures plummet.

Sources & More Info:

The Coleopterists Bulletin: Biology of Sparrmannia flava

The Book of Beetles: Sparrmannia

Eyewitness Travel Guide to South Africa: Sparrmannia flava

Journal of the Entomological Society of Southern Africa: Revision of the Genus Sparrmannia

Descriptive Catalogue of the Coleoptera of South Africa: Genus Sparrmannia

Excerpts from the Book Pollinators, Predators, and Parasites: Temperature Control in Sparrmannia flava and Dung Feeding in Woolly Chafer Beetle Larvae

#entomology#coleoptera#arthropods#african woolly chafer#scarab beetles#sparrmannia flava#beetles#insects#animal facts#bugs#sparrmannia#cute animals#woolly chafers#fuzzy beetles

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

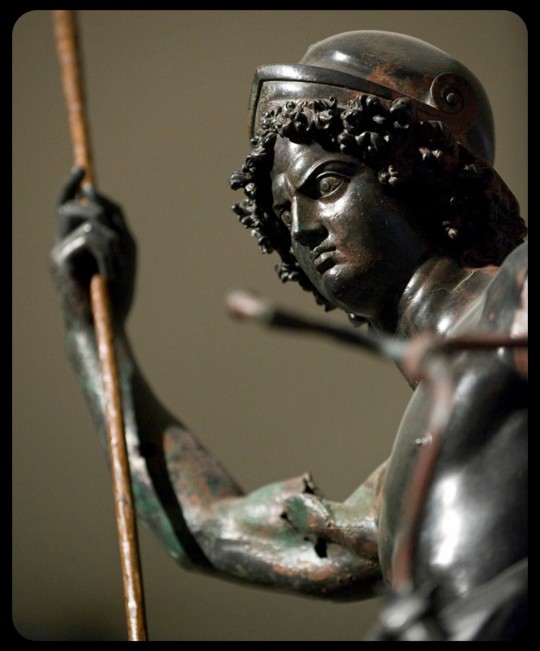

"Zeugma Mars" Statue from Turkey, c.250 CE: this statue depicting Mars, the Roman god of war, was unearthed from the ruins of a city that was occupied and plundered by the Sassanids in 253 CE

The bronze figure is nearly 1.5 meters (5 feet) tall. It has a strikingly intense expression, with eyes that are highlighted by gold and silver inlays.

According to this article:

A bronze statue of Mars, the Roman god of war, was found in the ancient city of Zeugma in the course of an excavation campaign in 1999-2000. The statue represents one of the most interesting and spectacular finds from this city on the banks of the Euphrates river in southern Anatolia.

The statue is of great interest on one side for its rarity, as few Roman bronzes of such size are so well preserved, and on the other for its unusual iconography, depicting the standing God as a young athlete. The figure stands with the weight centered on the right leg, while the left, slightly bent, rests only on the flexed toes. The right arm is raised, its hand closed around a spear that has not been found, while the left is bent at the elbow, to almost 90° and with the hand wielding an object that appears to be a scourge with multiple and symmetrical endings.

Beneath the helmet, thick curls frame the face of the young man whose frown is marked by strongly furrowed eyebrows and a very intense gaze, highlighted by silver and gold inlays around the pupils.

A chandelier was found along with the bronze. It is composed of a drum, similar in length to the sculpture, which passes through a disc and is inserted in a base. The small size of the space in which the artifacts were discovered and its place in the general plan of the villa suggests a closet where the precious materials were hidden to escape the pillaging of the city, carried out in 253-6 AD by the Sassanids.

Sources & More Info:

CCA (Centro di Conservazione Archeologica): Zeugma Mars Conservation Project

Journal of Roman Archaeology: The Bronze Mars of Zeugma

Turkish Museums: Time Capsule of Ancient Roman Art: Zeugma

Packard Humanities Institute: The Rescue Excavations at Zeugma in 2000 (PDF)

UNESCO: The Archaeological Site of Zeugma

Archaeological Institute of America: Troubled Waters

Archaeology Magazine: Zeugma After the Flood

#archaeology#artifact#history#anthropology#zeugma#turkey#anatolia#roman art#mars#god of war#ares#roman pantheon#paganism#ancient art#statue#bronze#classical antiquity#religion#art#sculpture#conservation

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Giant Emerald Pill-Millipede: when these enormous millipedes are all rolled up, their bodies can be as big as a baseball, a tennis ball, or a small orange

This species (Zoosphaerium neptunus) is commonly known as a giant emerald pill-millipede. The females can measure up to 90mm long (roughly 3.5 inches), making this the largest species of pill-millipede in the world.

There is a significant degree of sexual dimorphism in this species, with the males measuring only about 45mm (1.8 inches) long -- roughly half the size of the females.

Giant emerald pill-millipedes are found only in Madagascar, which is home to several endemic species of giant pill-millipedes (order Sphaerotheriida). The Malagasy name for giant pill-millipedes is "Tainkintana," which means "shooting-star."

Pill-millipedes use conglobation as a defense mechanism, which means that they can curl their bodies up into a spherical shape so that their dorsal plates form a protective shield around the softer, more vulnerable parts of their bodies, just like an actual pill-bug or a "roly-poly."

When they roll themselves up completely, they look almost like gently polished chunks of malachite, emerald, or jade.

Giant emerald pill-millipedes will sometimes form large swarms that travel together as a group. This is the only species of giant pill-millipede that engages in any sort of swarming behavior, and the purpose of that behavior is still unclear. The swarms often contain thousands of individuals, with almost all of them moving in the same direction, even when there is no physical contact that might allow the millipedes to "herd" one another along.

Their swarming behavior also has some very peculiar features, as this article explains:

During swarming, Zoosphaerium neptunus individuals pay little attention to their surroundings; many specimens were observed walking straight into and drowning in small puddles. Some swarms even display ‘cliché lemming behaviour:' in Marojejy, a large part of a swarm walked into and drowned in a small river.

No single specimen was observed walking ‘against the current,' all specimens were moving in the same direction (southeast), even when not in contact with one another.

Of 273 randomly collected individuals, 105 were males, while 168 were females. The males were 8.3 - 14.1 mm wide (average width 10.4 mm). According to the inner horns of the posterior telopods, all males were sexually mature. The females were 9.95 - 15.4 mm wide (average width 11.4 mm). All females displayed non sclerotized vulvae and were sexually immature.

Some researchers argue that the swarming serves as a defense mechanism, providing a layer of protection (or at least some cryptic cover) against local predators, but the swarming behavior is still poorly understood.

Important Note: I just want to remind everyone that these animals belong in their own natural habitat -- they should not be trapped, bought/sold, traded, shipped, collected, or kept as pets. This particular species does not survive well in captivity, either, and the demand for these "exotic" invertebrates is putting the wild populations in jeopardy. The previous article discusses those issues, too:

Another possible threat for Z. neptunus swarms are collections for the pet trade. There exists a large demand in Japan, Europe and North America for 'green -eyed monsters’ as pets. Giant pill -millipedes from Madagascar unfortunately have a very short survival time in terraria. The species is specialized on low-energy food (dead leaves), and adapted to the cool climates (<20°C) of the highlands. Specimens in terraria often starve to death quickly.

So I know that they're adorable and really, really fascinating...but let's just let them be their chunky, adorable little selves out in the wild where they belong.

Sources & More Info:

European Journal of Taxonomy: Seven New Giant Pill-Millipede Species and New Records of the Genus Zoosphaerium from Madagascar

Madagascar Conservation & Development: Swarming Behavior in the World's Largest Giant Pill-Millipede, Z. neptunus, and its Implication for Conservation Efforts

Bonn Zoological Bulletin Supplementum: The Giant Millipedes, Order Sphaerotheriida (an Annotated Species Catalogue) (PDF)

African Invertebrates: Madagascar's Living Giants: Discovery of Five New Species of Endemic Giant Pill-Millipedes from Madagascar (PDF)

#arthropods#giant green pill-millipede#zoosphaerium neptunus#myriapods#diplopoda#millipedes#island gigantism#entomology#evolution#malagasy#cool animals#bugs#insects#animal facts#madagascar#pill-millipede#pill bugs#but not really#Tainkintana#conglobation#swarming#conservation#giant emerald pill-millipede

4K notes

·

View notes