#mezzogiorno

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

" Tutti erano indifferenti, qui, quelli che desideravano salvarsi. Commuoversi, era come addormentarsi sulla neve. Avvertita dal suo istinto più sottile, la borghesia non smetteva di sorridere, e urtata continuamente dalla plebe, dai suoi dolori sanguinosi, dalla sua follìa, resisteva pazientemente, come un muro leccato dal mare. Non si poteva prevedere quanto questa resistenza sarebbe durata. Infine, anche la borghesia aveva dei pesi, ed erano l'impossibilità di credere che l'uomo fosse altra cosa dalla natura, e dovesse accettare la natura in tutta la sua estensione: erano l'antica abitudine di rispettare gli ordinamenti della natura, accettare da essa le illuminazioni come l'orrore. Dove nel popolo scoppiava di tanto in tanto la rivolta, e dalle alte mura della prigione uscivano bestemmie e rumore di pianti, qui la ragione taceva in un silenzio assoluto, temendo di rompere con una benché minima osservazione l'equilibrio in cui ancora la borghesia si reggeva, e vedere i suoi giorni sciogliersi al sole, come mai stati. La paura, una paura più forte di qualsiasi sentimento, legava tutti, e impediva di proclamare alcune verità semplici, alcuni diritti dell'uomo e, anzi, di pronunciare nel suo vero significato la parola uomo. Tollerato era l'uomo, in questi paesi, dall'invadente natura, e salvo solo a patto di riconoscersi, come la lava, le onde, parte di essa. "

-------------------

Brano tratto da Il silenzio della ragione, dalla raccolta di racconti:

Anna Maria Ortese, Il mare non bagna Napoli, Adelphi (collana Gli Adelphi n. 329), 2024¹⁷; p. 156.

[Prima edizione: Einaudi (collana I gettoni n. 18), 1953]

#Anna Maria Ortese#Il mare non bagna Napoli#letture#libri#letteratura italiana del XX secolo#citazioni letterarie#leggere#scrittrici italiane del '900#Napoli#Campania#narrativa italiana#neorealismo letterario#raccolte di racconti#sottosviluppo#Italia meridionale#Mezzogiorno#secondo dopoguerra#meridionalismo#Luigi Compagnone#Domenico Rea#Pasquale Prunas#Raffaele La Capria#Luigi Incoronato#Vasco Pratolini#povertà#miseria#Il silenzio della ragione#bambini#infanzia#plebe

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

CONSIGLI PER CHI VIENE IN CALABRIA

di Vito Teti

"Chi viene in Calabria deve prepararsi a un viaggio che richiede sguardi lucidi e amorevoli.

Non è facile dire cosa è la Calabria perché tutt’ora è terra leggendaria, mitica, caricata e sovrastata da una molteplicità di immagini ostili e superficiali, di cui non sono responsabili solo gli altri.

Io, come scriveva Alvaro, non so bene perché la amo. Perché a volte vorrei fuggire, mi domando che ci faccio qui; poi mi affaccio dai balconi, giro nei vicoli, incontro le persone di sempre, dialogo con i defunti, scavo nel mio sottoterra e intuisco, sento, perché la amo.

Non sarà facile il viaggio di chi verrà in questi luoghi, ma se è disponibile all’incontro, a capire, a mettersi in discussione, incontrerà una terra meravigliosa di cui non si libererà mai, perché la Calabria, nel bene e nel male, è una metafora del pianeta, che dovremmo sapere riguardare, amare, curare".

Foto di Federico Ferraboschi e Carlo Paone

Seguici su Instagram, @calabria_mediterranea

#calabria#italia#italy#south italy#southern italy#mediterranean#mare#consigli#italian#europe#landscape#italian landscape#sud italia#langblr#monasterace#vito teti#sud#mezzogiorno

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

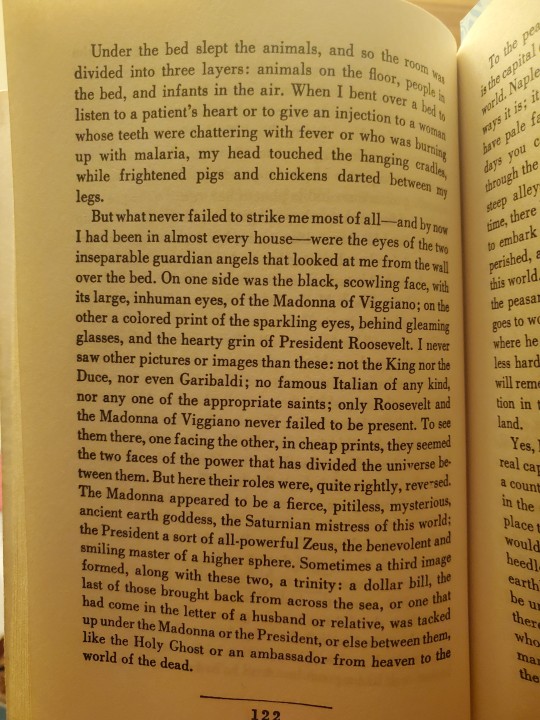

Insane passage from Christ Stopped at Eboli by Carlo Levi.

#books#reading#currently reading#italy#mezzogiorno#meridionalism#carlo levi#christ stopped at eboli#cristo si è fermato a eboli

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bollettino di mezzogiorno Campi

Bollettino di mezzogiorno Campi Biscotti Usiamo i cookie (cookie) per capire come usi il nostro sito e per migliorare la tua esperienza. Continuando a utilizzare il nostro sito, accetti di utilizzare i cookie. Politica sulla privacy Consenti tutto DTP – Source link original clik here

0 notes

Photo

PRIMA PAGINA Osservatore Romano di Oggi domenica, 23 febbraio 2025

#PrimaPagina#osservatoreromano quotidiano#giornale#primepagine#frontpage#nazionali#internazionali#news#inedicola#oggi romano#quotidiano#politico#religioso#domani#mezzogiorno#preghiera#policlinico#pero#sara#pubblicato#preparato#papa#alla#terapia#ancora#fuori#oggi#sala#della

0 notes

Text

#Sottosviluppo#CriminalitàOrganizzata#mezzogiorno#mafia#disuguaglianze#Italia#politica#magistratura#stato#giustizia#antimafia#ndrangheta#società#cosanostra#economia#collusione#sviluppo

0 notes

Text

Italia, un Paese che perde i giovani: 750.000 in meno in dieci anni

L’Italia sta affrontando una crisi demografica senza precedenti, con un esodo giovanile che ha ridotto di 750.000 unità (-5,8%) la popolazione tra i 15 e i 34 anni nell’ultimo decennio. Questo fenomeno, particolarmente acuto nel Mezzogiorno, riflette problematiche strutturali che minacciano la sostenibilità socioeconomica del paese. Un’emorragia generazionale senza freni Il calo colpisce in…

#Abbandono scolastico#calo demografico#Demografia#denatalità#disoccupazione#Divario Nord-Sud#Fuga di cervelli#giovani#Italia#Mezzogiorno#migrazione

0 notes

Link

Il lavoro da remoto è un trend che è sempre più popolare tra i giovani professionisti soprattutto quelli con maggiori con competenze nell'IT. Attirare i nomadi digitali potrebbe essere una strategia per rilanciare il Mezzogiorno d'Italia? Ne parliamo con Nicolò Andreula che lavora in Puglia su questi temi e ci suggerisce qualche idea per rendere i nostri paesi appetibili ai nomadi digitali.

0 notes

Text

Quali rischi per le donne sulle riforme del premierato e autonomia differenziata. Il pensiero femminista è cruciale per contrastare queste riforme che potrebbero aumentare le disuguaglianze e limitare la libertà di scelta delle donne.

#abbandono scolastico#autonomia differenziata#Cristina Montagni#democrazia#diritti delle donne#disuguaglianze#gap salariale#Lavoro#mezzogiorno#partecipazione#pensiero femminista#povertà#premierato#Salute#women for women Italy

1 note

·

View note

Text

“ Glielo vorrei dire, ma non saprei proprio come fare: non gli ho mai detto nulla. Le uniche parole che ci scambiamo da anni, sono queste: «Giovanni»; «Domenico». Giovanni è il mio nome, Domenico è il suo. Ogni mattina, quando esco, richiudo piano la porta e scendo le scale: lui è lì, a lavare le scale o l’ingresso dello stabile. Comincia dall’ultimo piano e arriva fino al piano terra, tutti i giorni. Quando mi vede, alza appena il capo e dice: «Giovanni». Che vuol dire: «Buongiorno Giovanni». E forse pure: «Come va?». E io rispondo: «Domenico». Che vuol dire: «Buongiorno anche a lei, Domenico. Spero che non sarà una giornata faticosa» o roba del genere. Ma non riusciamo a dire altro che i nostri nomi: «Giovanni»; «Domenico». Ogni mattina quando esco, e ogni volta quando torno all’ora del pranzo - il pomeriggio lui va via. Così, da anni. In qualsiasi circostanza; in qualsiasi stagione. «Giovanni»; «Domenico». Una volta, una vigilia di Natale di qualche anno fa, disse - lo ricordo così bene: «Giovanni, è Natale». Restai stupito, e per qualche attimo cercai di capire cosa volesse dire. Poi risposi: «Sì, Domenico, è Natale» e quel giorno pensai che finalmente i nostri rapporti sarebbero cambiati.

Ma poi il giorno dopo lui era in ferie e nei giorni seguenti non fu più Natale, e così per tutti i mesi successivi, quando ormai un anno intero di «Giovanni» e «Domenico» avevano allontanato la confidenza di quel giorno. E alla vigilia di Natale dell’anno seguente, scendendo le scale con una speranza remota ma viva, gli andai incontro deciso. Lui alzò per un attimo la schiena dalla scopa e disse senza indecisione: «Giovanni». Non potei fare altro che rispondere: «Domenico». Da quel giorno mancarono aggiunte al nostro saluto. Anche alla vigilia di Natale o in altre festività. “

Francesco Piccolo, Storie di primogeniti e figli unici, Feltrinelli (collana Universale Economica n° 1483), 1998; pp. 15-16.

#letture#leggere#festività#condominio#condomini#riserbo#Francesco Piccolo#Italia meridionale#riservatezza#portinaio#raccolta di racconti#anni '90#discrezione#timidezza#libri#Storie di primogeniti e figli unici#Mezzogiorno#ritrosia#ferie#letteratura contemporanea#racconti brevi#Campania#tempo#intellettuali contemporanei#vigilia di Natale#indecisione#vita#confidenza#conoscenti#esitazione

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

"There can be no systematic intellectual progress in the study of organized crime assuming contentious governing structures beforehand.

Feuds and vendettas are endemic within underworld societies though one cannot assume there are never any effective restraints. It makes perfectly good sense for mobsters of any ethnic or racial background in any era to realize that killing other mobsters is dangerous and for them to seek allies or determine the range of opponents when contemplating such action. Sometimes those they wish to kill are frightening enough to restrain violence; sometimes not. Reasonable fear aside, there are other factors which either impede or stimulate organized crime's internal violence. Among the most important is whether or not there is a serious law enforcement investigation focusing on particular syndicates. For when organized criminals face potentially decisive prosecutions, they turn to killing one another with abandon knowing that their closest allies pose an unacceptable risk.

Informing is often good for business particularly when it eliminates competition in various illicit activities. Giving up other criminals thus helps to keep the police away from one's own door. Informing is also demanded by law enforcement for its own organizational needs, both for continuing general intelligence and to maintain a record of arrests and prosecutions. All this without mentioning corruption in the classic sense, where police figures are more deeply embedded members of criminal syndicates, or those variants where police units are in effect criminal syndicates. In these variations, intelligence-gathering through a flow of coerced underworld informants is constant. In the complex web of relations between organized crime and law enforcement, informing on others is a crucially important activity. That organized criminals "grass" to police is more the rule than is the romantic notion of "omerta." This naturally sets off a murderous Cycle - those with critical information know they may well be killed by their closest confederates so they in turn either kill them, flee, turn to law enforcement as informants. It is always a very precarious business, with treachery at every step.

Patron-client networks which can be thought of as complex grids of constantly changing social power holding precariously together professional criminals, their clients and victims, criminal lawyers, police and politicians, are the predominant form of association characteristic of underworlds. Obviously crime bosses and others in these networks seek to achieve a situation in which they will be protected-bosses from ambitious underlings and rival bosses, underlings and associates from bosses either somewhat psychopathic or under pressure from law enforcement. But there are no methods for controlling violence once these networks begin to change as they invariably do, except the traditional one of murdering actual and more importantly potential informers.

In the social world of organized crime who can ever know with certainty what criminal with important knowledge will inform? The fluid structure of criminal syndicates and the turbulent world within which organized criminals operate always undermine loyalty and restraint despite what crime bosses anxious about their safety may wish. The most important variables of instability are the waxing and waning of law enforcement's needs, the pressures of political reform movements, and simple ambition. They all have a corrosive effect on the connective tissue of patron-clientage.

Nonetheless, the notion of contained violence still persists, as Buscetta's testimony makes clear, indicating it probably serves other purposes or represents an "idealization" of organized crime. In fact, an "idealized" version of organized crime's development may well aid the bureaucratic needs of state agencies. It also appears to fit with popular though mistaken social science paradigms; in this case that of criminal modernization. In the latter case this theme-- sanctioned murder leading to a more complex criminal organization or the other way round-gained a foothold among criminologists because it seemed so logical. Hence, it was not noticed that it reversed the link between data and interpretation. Underworld tattlers filled in the appropriate empirical slots in an already extant theoretical structure.

The most cogent criminological statement that reveals this backward development was given by Robert T. Anderson several decades ago, In his quite famous article, "From Mafia to Cosa Nostra," published in the American Journal of Sociology, argued that the Sicilian Mafia was changing as Sicily itself underwent the process of modernization. Part of that process can be observed, Anderson noted, in the Mafia's adaptation and expansion of its "techniques of exploitation." Quoting from a 1960 article by reporter Claire Sterling, Anderson found that the Mafia had become urbanized:

Today there is not only a Mafia of the feudo (agriculture) but also Mafias of truck gardens, wholesale fruit and vegetable markets, water supply, meat, fishing fleets, flowers, funerals, beer, carrozze (hacks), garages, and construction. Indeed, there is hardly a businessman in western Sicily who doesn't pay for the Mafia's 'protection' in the form of 'u pizzu.

It is not certain what is urban about all these activities (fishing fleets, for instance), but it is plain that Mafia enterprises had widened from what earlier accounts had suggested.

When all was said and done, the dramatic point was that the Mafia "has bureaucratized," or almost bureaucratized, or was on the road to bureaucratization. Anderson wrote that the old or traditional Mafia was "family-like," lacking at least three of the four necessary "characteristics of a bureaucracy." However, that was all changing as Sicily "poised for industrialization with its concomitant changes." But because Sicily was on the brink of modernization, the Sicilian Mafia was momentarily, at least, a mix of the old and the new. There was no doubt, however, where it was heading.

Remarkably enough, it was the American Mafia that provided the example and model. It had achieved bureaucratization, remarked Anderson, "beyond that even of bureaucratized Sicilian groups." One of the key elements in this process involved a striking change in Mafia custom: "Modern mafiosi avoid the use of force as much as possible, and thus differ strikingly from old Sicilian practice." Here, Anderson intimates that the contemporary Sicilian Mafia is also moving in the same direction--away from violence toward other methods of dispute settlement. His discussion of the American Cosa Nostra holds that this overarching structure which is both a proof and attribute of Mafia bureaucratization serves to "adjudicate disputes…to minimize internecine strife, rather than to administer co-operative undertakings."

- Alan A. Block, "Organized Crime: History and Historiography,” in Space, Time & Organized Crime. Second Edition. New York: Routledge, 2020 (originally 1994). p. 33-35.

#criminology#history of criminology#historiography#mafia#organized crime#mezzogiorno#organized criminals#history of drug use#academic quote#reading 2024#history of crime and punishment#convict code#honour among thieves#professional criminals#snitches get stitches#violent crime#criminal informant

0 notes

Text

Practice English

share.libbyapp.com/title/1313204

View On WordPress

#“Treasure Hunt”#Camilleri Andrea#El Sur#English as a Second Language#ESL#Inspector Montalbano#Le Midi#Mezzogiorno#practice English#Pre-Italian#Salvo Montalbano#trinacria#triskelion

0 notes

Text

The Wounded Man (1983) dir. Patrice Chéreau

#the wounded man#l’homme blesse#patrice chéreau#jean hugues anglade#vittorio mezzogiorno#gérard depardieu#film screencaps#film stills#films#screencaps#cinematography

850 notes

·

View notes

Text

L'homme blessé (1983) dir. Patrice Chéreau

#the wounded man#l'homme blessé#jean-hugues anglade#vittorio mezzogiorno#filmgifs#dailyflicks#lgbtedit#gayedit#holesrus#men#menedit#patrice chéreau#usermichi#userviet#userdckingston#gifs#mine#*#jean hugues anglade

821 notes

·

View notes

Photo

PRIMA PAGINA Osservatore Romano di Oggi sabato, 22 febbraio 2025

#PrimaPagina#osservatoreromano quotidiano#giornale#primepagine#frontpage#nazionali#internazionali#news#inedicola#oggi romano#quotidiano#politico#religioso#domani#mezzogiorno#preghiera#policlinico#pero#sara#pubblicato#preparato#papa#alla#terapia#ancora#fuori#oggi#sala#della

0 notes

Text

The Wounded Man. Patrice Chéreau. 1983

#the wounded man#patrice chereau#french film#80s#jean hugues anglade#vittorio mezzogiorno#liminal#liminal spaces#cinema

59 notes

·

View notes