#land dispossession

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

ESTATU KOLONIAL & ARRAZISTA

#Kanaky#colonialism#France : a colonial & racist state#working for white supremacy#traffic ban#forced labor#land dispossession#P.Messmer: “make white” (send 100 000)#Ataï#cut the head of Kanaky chief and exposed in the museum#human zoo#1931: 111 Kanaky exposed#Nickel#Mururua#Ouvea#2024

5 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Although over 8% of India's population belongs to a tribe, according to the latest census, tribal communities are increasingly being squeezed to the margins of society. "Despite more than two decades of impressive GDP growth, India's growth has remained confined to enclaves of prosperity surrounded by vast hinterlands of deprivation. Indigenous communities of India have been pushed farther away from alluvial plains and fertile river basins into the harshest ecological regions of the country like hills, forests and drylands,” a "tribal development report" from the Bharat Rural Livelihoods Foundation (BRLF) reads.

Murali Krishnan, ‘India's tribes living on the margin of society’, Deutsche Welle

#Deutsche Welle#Murali Krishnan#India#tribal communities#deprivation#Indigenous communities#Bharat Rural Livelihoods Foundation#Land dispossession

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

[Image Description: There are nine images being described. The images describe different crisis' the Congo is facing at the hands of three trillion-dollar corporations (Apple, Alphabet (the parent company of Google), Microsoft) and two billion-dollar corporation (Tesla and Dell Technologies). The resulting ID is long, and thus has been placed behind the 'Keep reading' link.

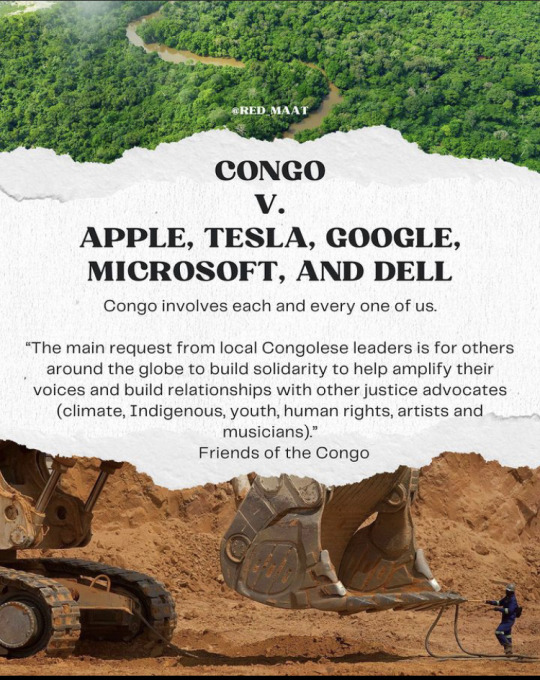

The first image contains two pictures, one at the top of the image and the other at the bottom, with black text on a white background in the middle. The top picture is of the Congo Rainforest and Basin, a vibrant green rainforest with a winding brown river cutting through the middle of the picture from top to bottom. The bottom picture is of a mining expedition in the Congo. A large Hydraulic Mining Shovel is in the foreground of the picture and a comparatively tiny human stands beside it on the right side of the picture. The background of the picture is brown, dug-up dirt and the wall of dirt behind the Hydraulic Mining Shovel and human extends past the top of the picture. They are far below surface level. The text in the middle is titled "Congo v. Apple, Tesla, Google, Microsoft, and Dell. Congo involves each and every one of us." and contains a quote from Friends of the Congo which reads: "The main request from local Congolese leaders is for others around the globe to build solidarity to help amplify their voices and build relationships with other justice advocates (climate, Indigenous, youth, human rights, artists and musicians)."

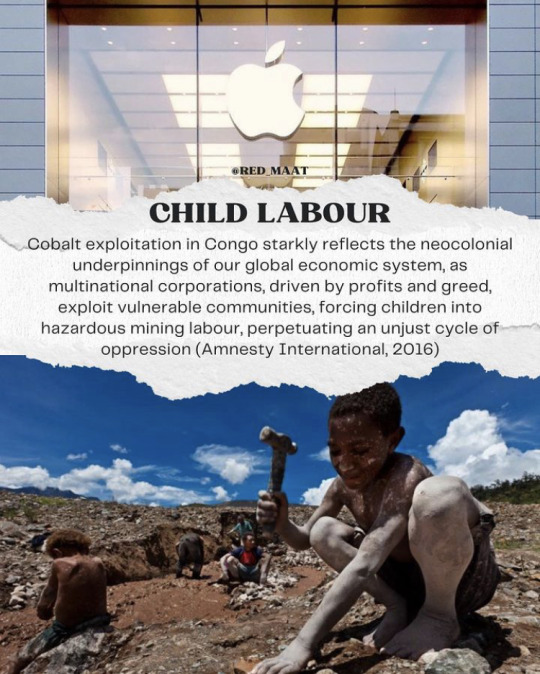

The second image uses the same format as the prior image, with two pictures and a section of text in the middle. The top picture is of the outside of an Apple store, with the Apple logo shown clearly in the centre of the image. The bottom picture is of underage children mining cobalt. There is a young boy in the foreground, wearing only shorts and covered in dust, crouched and holding a small hammer. There are four other people in the background of indeterminate age. The text in the middle is titled "Child Labour" and reads: Cobalt exploitation in Congo starkly reflects the neocolonial underpinnings of our global economic system, as multinational corporations, driven by profits and greed, exploit vulnerable communities, forcing children into hazardous mining labour, perpetuating an unjust cycle of oppression (Amnesty International, 2016).

The third image uses the same format as the prior image, with two pictures and a section of text in the middle. The top picture is of the outside of a Google store, with the logo and brand name clearly shown. The bottom picture is of a young woman in a field of dirt mounds. She is in the foreground of the picture, and is bent over and holding a cardboard box with fabric lining the bottom in one of her hands while the other holds a small child to her chest. There is a young man present in the background, on the right side of the picture. The text in the middle is titled "Women's Rights" and reads: Within the cobalt mining landscape, women bear the brunt of an inherently unequal system, where their rights are trampled upon amidst a backdrop of corporate greed and capitalist structure that systemically marginalizes and subjects them to gender-based violence (Human Rights Watch, 2019).

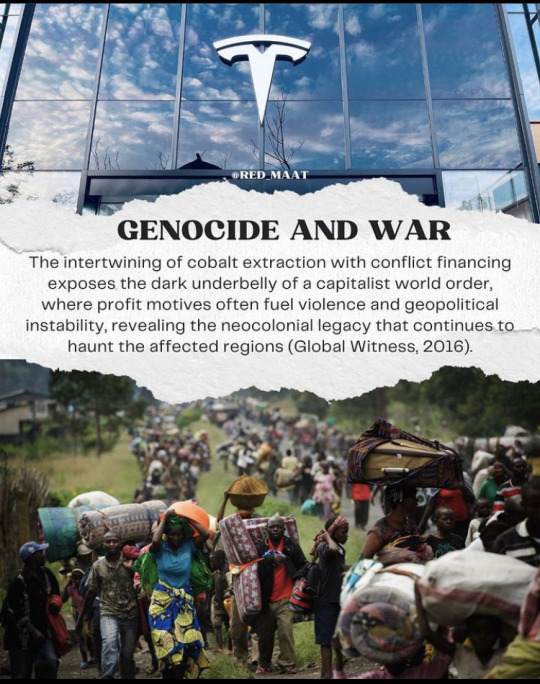

The fourth image uses the same format as the prior image, with two pictures and a section of text in the middle. The top picture is of the outside of a Tesla store, with the logo clearly shown in the middle of the picture. The bottom picture is of a large group of displaced Congolese people. They are moving in three lines and are transporting essential items such as bedding. The text in the middle is titled "Genocide and War" and reads: The intertwining of cobalt extraction with conflict financing exposes the dark underbelly of a capitalist world order, where profit motives often fuel violence and geopolitical instability, revealing the neocolonial legacy that continues to haunt the affected regions (Global Witness, 2016).

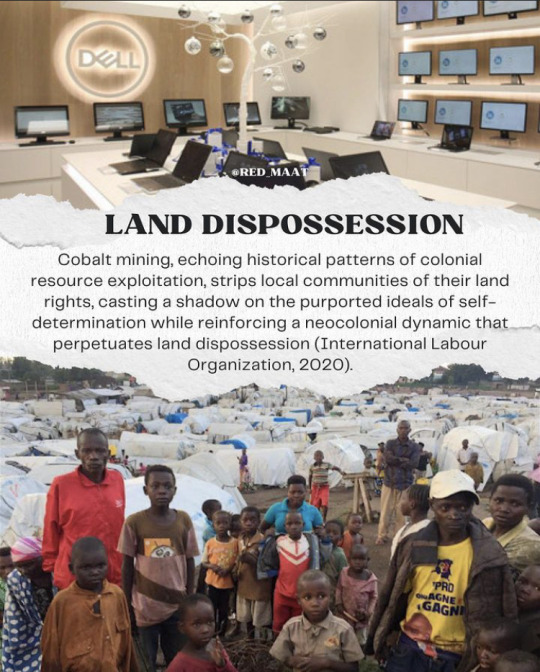

The fifth image uses the same format as the prior image, with two pictures and a section of text in the middle. The top image is of the inside of a Dell Technologies store, with the Dell Technologies logo and brand name shown clearly alongside 23 display computers. The bottom picture is of 24 Congolese people standing in the foreground of the image. Behind them are numerous white tents that extend past the top of the image. The text in the middle is titled "Land Dispossession" and reads: Cobalt mining, echoing historical patterns of colonial resource exploitation, strips local communities of their land rights, casting a shadow on the purported ideals of self-determination while reinforcing a neocolonial dynamic that perpetuates land dispossession (International Labour Organization, 2020).

The sixth image uses the same format as the prior image, with two pictures and a section of text in the middle. The top image is of the outside of a Microsoft store, with the Microsoft logo and brand name clearly shown on the left and right of the image. The second image is of a dirt valley, which is likely an old cobalt mine, with numerous people in the middle. There is no vegetation to be seen and countless sandbags piled on top of each other to decrease land degradation. The text in the middle is titled "Environmental Degradation" and reads: The environmental degradation resulting from cobalt exploitation serves as a poignant metaphor for the ecological costs paid by marginalized nations to fuel the insatiable machinery of capitalist consumption, underscoring the urgent need for a more sustainable and just economic paradigm (United Nations Environment Programme, 2017).

The seventh image contains five graphs and is aptly titled "Big Tech Profits Off Atrocities". Each graph shows the revenue of the five companies (In order of graph appearance: Google, Microsoft, Dell, Tesla, and Apple). The first graph is titled "Revenue of Google from 1st quarter 2008 to 3rd quarter 2023 (in million U.S. dollars)". The most recent data point plotted is from the 1st quarter of 2023, which rests just under 80,000 million U.S. dollars. The second graph is titled "Microsoft's net income from 2002 to 2023 (in billion U.S. dollars)". The most recent data point plotted is from 2023, which rests at 72.36 billion U.S. dollars. The third graph is titled "Dell Technologies net revenue worldwide from 1996 to 2023 (in billion U.S. dollars)". The most recent data point plotted is from 2022, which rests at just above 100 billion U.S. dollars. The fourth graph is titled "Tesla's revenue from FY 2008 to FY 2022 (in million U.S. dollars)". The most recent data point plotted is from 2022, which rests at 81,462 million U.S. dollars. The fifth graph is titled "Apple's net income in the company's fiscal years from 2005 to 2023 (in billion U.S. dollars)". The most recent data point plotted is from 2023, which rests at 96.99 billion U.S. dollars.

The eight image contains three paragraphs of white text on a black background, with lines coloured green, red, and blue separating them. The first paragraph reads: We're not buying McDonalds in 2024, or Starbucks or Puma. 🇵🇸 We're not replacing our phones because we feel like it. We're not replacing our laptops because we don't know what else to ask for for Xmas. The second paragraph reads: We're not buying five devices that are identical in every way but size. 🇨🇩 We're not being friends with people who deny that what is happening in Palestine, Sudan or Congo is horrific and has to stop. The third paragraph reads: We're not explaining empathy to Zionists or racists in 2024.

The ninth image contains three rectangular sections: the top section is coloured black, the middle section is coloured green, and the bottom section is coloured red. There is text in each section. The top section's text is written in white. It reads: The UAE are funding crimes against humanity in Sudan, Palestine, Yemen, and Congo. The words "crimes against humanity" are written in red. The middle section's text is written in black and all capitals. It reads: Join us to protest the force that funds these atrocities. The bottom section's text is written in white. It reads: Sunday 14th January 12 noon. London.

/.End ID]

Learn about Congo 🇨🇩 We cannot , after finding out so shamefully late about the genocide, continue as per. We have to change our choices and make the effort to be as ethical as we can and talk about this!

#image description#accessability#long post#congo#the republic of congo#trillion dollar companies#billion dollar companies#apple#tesla#google#microsoft#dell#dell technologies#crimes against humanity#child labour#women's rights#genocide#war#land dispossession#environmental degradation

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

"In these circumstances, the commercial economy of the fur trade soon yielded to industrial economies focused on mining, forestry, and fishing. The first industrial mining (for coal) began on Vancouver Island in the early 1850s, the first sizeable industrial sawmill opened a few years later, and fish canning began on the Fraser River in 1870. From these beginnings, industrial economies reached into the interstices of British Columbia, establishing work camps close to the resource, and processing centers (canneries, sawmills, concentrating mills) at points of intersection of external and local transportation systems. As the years went by, these transportation systems expanded, bringing ever more land (resources) within reach of industrial capital. Each of these developments was a local instance of David Harvey's general point that the pace of time-space compressions after 1850 accelerated capital's "massive, long-term investment in the conquest of space" (Harvey 1989, 264) and its commodifications of nature. The very soil, Marx said in another context, was becoming "part and parcel of capital" (1967, pt. 8, ch. 27).

As Marx and, subsequently, others have noted, the spatial energy of capitalism works to deterritorialize people (that is, to detach them from prior bonds between people and place) and to reterritorialize them in relation to the requirements of capital (that is, to land conceived as resources and freed from the constraints of custom and to labor detached from land). For Marx the

wholesale expropriation of the agricultural population from the soil... created for the town industries the necessary supply of a 'free' and outlawed proletariat (1967, pt. 8, ch. 27).

For Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari (1977) - drawing on insights from psychoanalysis - capitalism may be thought of as a desiring machine, as a sort of territorial writing machine that functions to inscribe "the flows of desire upon the surface or body of the earth" (Thomas 1994, 171-72). In Henri Lefebvre's terms, it produces space in the image of its own relations of production (1991; Smith 1990, 90). For David Harvey it entails the "restless formation and reformation of geographical landscapes," and postpones the effects of its inherent contradictions by the conquest of space-capitalism's "spatial fix" (1982, ch. 13; 1985, 150, 156). In detail, positions differ; in general, it can hardly be doubted that in British Columbia industrial capitalism introduced new relationships between people and with land and that at the interface of the native and the nonnative, these relationships created total misunderstandings and powerful new axes of power that quickly detached native people from former lands. When a Tlingit chief was asked by a reserve commissioner about the work he did, he replied

I don't know how to work at anything. My father, grandfather, and uncle just taught me how to live, and I have always done what they told me-we learned this from our fathers and grandfathers and our uncles how to do the things among ourselves and we teach our children in the same way.

Two different worlds were facing each other, and one of them was fashioning very deliberate plans for the reallocation of land and the reordering of social relations. In 1875 the premier of British Columbia argued that the way to civilize native people was to bring them into the industrial workplace, there to learn the habits of thrift, time discipline, and materialism. Schools were secondary. The workplace was held to be the crucible of cultural change and, as such, the locus of what the premier depicted as a politics of altruism intended to bring native people up to the point where they could enter society as full, participating citizens. To draw them into the workplace, they had to be separated from land. Hence, in the premier's scheme of things, the small reserve, a space that could not yield a livelihood and would eject native labor toward the industrial workplace and, hence, toward civilization. Marx would have had no illusions about what was going on: native lives, he would have said, were being detached from their own means of production (from the land and the use value of their own labor on it) and were being transformed into free (unencumbered) wage laborers dependent on the social relations of capital. The social means of production and of subsistence were being converted into capital. Capital was benefiting doubly, acquiring access to land freed by small reserves and to cheap labor detached from land.

The reorientation of land and labor away from older customary uses had happened many times before, not only in earlier settler societies, but also in the British Isles and, somewhat later, in continental Europe. There, the centuries-long struggles over enclosure had been waged between many ordinary folk who sought to protect customary use rights to land and landlords who wanted to replace custom with private property rights and market economies. In the western highlands, tenants without formal contracts (the great majority) could be evicted "at will." Their former lands came to be managed by a few sheep farmers; their intricate local land uses were replaced by sheep pasture (Hunter 1976; Hornsby 1992, ch. 2). In Windsor Forest, a practical vernacular economy that had used the forest in innumerable local ways was slowly eaten away as the law increasingly favored notions of absolute property ownership, backed them up with hangings, and left less and less space for what E.P. Thompson calls "the messy complexities of coincident use-right" (1975, 241). Such developments were approximately reproduced in British Columbia, as a regime of exclusive property rights overrode a fisher-hunter-gatherer version of, in historian Jeanette Neeson's phrase, an "economy of multiple occupations" (1984, 138; Huitema, Osborne, and Ripmeester 2002). Even the rhetoric of dispossession - about lazy, filthy, improvident people who did not know how to use land properly - often sounded remarkably similar in locations thousands of miles apart (Pratt 1992, ch. 7). There was this difference: The argument against custom, multiple occupations, and the constraints of life worlds on the rights of property and the free play of the market became, in British Columbia, not an argument between different economies and classes (as it had been in Britain) but the more polarized, and characteristically racialized juxtaposition of civilization and savagery...

Moreover, in British Columbia, capital was far more attracted to the opportunities of native land than to the surplus value of native labor. In the early years, when labor was scarce, it sought native workers, but in the longer run, with its labor needs supplied otherwise (by Chinese workers contracted through labor brokers, by itinerant white loggers or miners), it was far more interested in unfettered access to resources. A bonanza of new resources awaited capital, and if native people who had always lived amid these resources could not be shipped away, they could be-indeed, had to be-detached from them. Their labor was useful for a time, but land in the form of fish, forests, and minerals was the prize, one not to be cluttered with native-use rights. From the perspective of capital, therefore, native people had to be dispossessed of their land. Otherwise, nature could hardly be developed. An industrial primary resource economy could hardly function.

In settler colonies, as Marx knew, the availability of agricultural land could turn wage laborers back into independent producers who worked for themselves instead of for capital (they vanished, Marx said, "from the labor market, but not into the workhouse") (1967, pt. 8, ch. 33). As such, they were unavailable to capital, and resisted its incursions, the source, Marx thought, of the prosperity and vitality of colonial societies. In British Columbia, where agricultural land was severely limited, many settlers were closely implicated with capital, although the objectives of the two were different and frequently antagonistic. Without the ready alternative of pioneer farming, many of them were wage laborers dependent on employment in the industrial labor market, yet often contending with capital in bitter strikes. Some of them sought to become capitalists. In M. A. Grainger's Woodsmen of the West, a short, vivid novel set in early modern British Columbia, the central character, Carter, wrestles with this opportunity. Carter had grown up on a rock farm in Nova Scotia, worked at various jobs across the continent, and fetched up in British Columbia at a time when, for a nominal fee, the government leased standing timber to small operators. He acquired a lease in a remote fjord and there, with a few men under towering glaciers at the edge of the world economy, attacked the forest. His chances were slight, but the land was his opportunity, his labor his means, and he threw himself at the forest with the intensity of Captain Ahab in pursuit of the white whale. There were many Carters.

But other immigrants did become something like Marx's independent producers. They had found a little land on the basis of which they hoped to get by, avoid the work relations of industrial capitalism, and leave their progeny more than they had known themselves. Their stories are poignant. A Czech peasant family, forced from home for want of land, finding its way to one of the coaltowns of southeastern British Columbia, and then, having accumulated a little cash from mining, homesteading in the province's arid interior. The homestead would consume a family's work while yielding a living of sorts from intermittent sales from a dry wheat farm and a large measure of domestic self-sufficiency-a farm just sustaining a family, providing a toe-hold in a new society, and a site of adaptation to it. Or, a young woman from a brick, working-class street in Derby, England, coming to British Columbia during the depression years before World War I, finding work up the coast in a railway hotel in Prince Rupert, quitting with five dollars to her name after a manager's amorous advances, traveling east as far as five dollars would take her on the second train out of Prince Rupert, working in a small frontier hotel, and eventually marrying a French Canadian farmer. There, in a northern British Columbian valley, in a context unlike any she could have imagined as a girl, she would raise a family and become a stalwart of a diverse local society in which no one was particularly well off. Such stories are at the heart of settler colonialism (Harris 1997, ch. 8).

The lives reflected in these stories, like the productions of capital, were sustained by land. Older regimes of custom had been broken, in most cases by enclosures or other displacements in the homeland several generations before emigration. Many settlers became property owners, holders of land in fee simple, beneficiaries of a landed opportunity that, previously, had been unobtainable. But use values had not given way entirely to exchange values, nor was labor entirely detached from land. Indeed, for all the work associated with it, the pioneer farm offered a temporary haven from capital. The family would be relatively autonomous (it would exploit itself). There would be no outside boss. Cultural assumptions about land as a source of security and family-centered independence; assumptions rooted in centuries of lives lived elsewhere seemed to have found a place of fulfillment. Often this was an illusion - the valleys of British Columbia are strewn with failed pioneer farms - but even illusions drew immigrants and occupied them with the land.

In short, and in a great variety of ways, British Columbia offered modest opportunities to ordinary people of limited means, opportunities that depended, directly or indirectly, on access to land. The wage laborer in the resource camp, as much as the pioneer farmer, depended on such access, as, indirectly, did the shopkeeper who relied on their custom.

In this respect, the interests of capital and settlers converged. For both, land was the opportunity at hand, an opportunity that gave settler colonialism its energy. Measured in relation to this opportunity, native people were superfluous. Worse, they were in the way, and, by one means or another, had to be removed. Patrick Wolfe is entirely correct in saying that "settler societies were (are) premised on the elimination of native societies," which, by occupying land of their ancestors, had got in the way (1999, 2). If, here and there, their labor was useful for a time, capital and settlers usually acquired labor by other means, and in so doing, facilitated the uninhibited construction of native people as redundant and expendable. In 1840 in Oxford, Herman Merivale, then a professor of political economy and later a permanent undersecretary at the Colonial Office, had concluded as much. He thought that the interests of settlers and native people were fundamentally opposed, and that if left to their own devices, settlers would launch wars of extermination. He knew what had been going on in some colonies - "wretched details of ferocity and treachery" - and considered that what he called the amalgamation (essentially, assimilation through acculturation and miscegenation) of native people into settler society to be the only possible solution (1928, lecture xviii). Merivale's motives were partly altruistic, yet assimilation as colonial practice was another means of eliminating "native" as a social category, as well as any land rights attached to it as, everywhere, settler colonialism would tend to do.

These different elements of what might be termed the foundational complex of settler colonial power were mutually reinforcing. When, in 1859, a first large sawmill was contemplated on the west coast of Vancouver Island, its manager purchased the land from the Crown and then, arriving at the intended mill site, dispersed its native inhabitants at the point of a cannon (Sproat 1868). He then worried somewhat about the proprieties of his actions, and talked with the chief, trying to convince him that, through contact with whites, his people would be civilized and improved. The chief would have none of it, but could stop neither the loggers nor the mill. The manager and his men had debated the issue of rights, concluding (in an approximation of Locke) that the chief and his people did not occupy the land in any civilized sense, that it lay in waste for want of labor, and that if labor were not brought to such land, then the worldwide progress of colonialism, which was "changing the whole surface of the earth," would come to a halt. Moreover, and whatever the rights or wrongs, they assumed, with unabashed self-interest, that colonists would keep what they had got: "this, without discussion, we on the west coast of Vancouver Island were all prepared to do." Capital was establishing itself at the edge of a forest within reach of the world economy, and, in so doing, was employing state sanctioned property rights, physical power, and cultural discourse in the service of interest."

- Cole Harris, “How Did Colonialism Dispossess? Comments from an Edge of Empire,” Annals of the Association of American Geographers, Vol. 94, No. 1 (Mar., 2004), p. 172-174.

#settler colonialism#settler colonialism in canada#dispossession#violence of settler colonialism#land theft#canadian history#indigenous people#first nations#reading 2024#cole harris#history of british columbia#reservation system#resource extraction#british empire#canada in the british empire#homesteading#marxist theory#capitalism#capitalism in canada#immigration to canada

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

The plan IS genocide

Everything else is window dressing, posturing, slowrolling and denying.

#palestine#palestinians#gaza#genocide#rafah#west bank#israeli atrocities#israeli apartheid#israeli occupation#idf terrorists#iof terrorism#war crimes#right wing extremism#ethnic cleansing#free palestine#free gaza#justice#human rights#annexation#annihilation#dispossession#land grab#state theft#fraud#settler colonialism#illegal settlements#illegal occupation#dirty war#us complicity#us weapons

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

got reminded of the "saying Arabs conquered and colonized North Africa is Zionist because obviously no one saying that coulx possibly draw a distinction between North African Arabs and Palestinian Arabs, and even drawing a distinction between Arabs and Imazighen is colonizer shit" school of thought

#cipher talk#I have seem Zionists co-opt the language of MENA Indigenous groups but MF that doesn't mean we're WRONG#It means they're stealing our talking points to appeal to more left leaning people#How is it you can recognize that they've co-opted the language of social justice and that that doesn't mean social justice is bad#Until the people YOU dispossess are mentioned and suddenly you're doing step 8 of the 8 steps of white settler colonial denial#Just like the Israelis do!#And yeah like. Some people don't draw the distinction. That's a product of intergenerational trauma and how our communities#Get manipulated by the US and shit. I've also met Arabs not from North Africa that refuse to draw a distinction#And see a discussion of how Arabs have hurt Indigenous Africans as an attack on them when it doesn't make sense to do so#I've also met a lot of people who DO clearly draw a distinction because the material conditions of Palestinians are that of Indigenity#Are your material conditions as a postcolonial North African with an Arab name and a mosque and skin that isn't black that of Indigenity?#Do you not have people with your face in the government (regardless of how shifty it is)? Did someone take your land or your churches land?#Do you struggle with employment? Is your tongue not the most common one? Are your cultural clothes looked at with distaste?#Are your girls targeted for kidnapping and rape to force them to not be of your culture? Are your women called whores who WANT rape?#Are you harassed by cops? Does the government try to take your kids because they have bullshit adoption laws?#Do your kids get arrested at 12 or 13 and almost sent a thousand miles away from home before pressure stays the order?#Is your language called feudal? Do people tell you they hope it dies soon? Is your name a barrier in your life?#Did they drown your fucking village?#Because all of these are things Copts and Nubians can say yes to#Before I even start on the shit done in the Maghreb or the fuckery about how Egypt defines 'Amazigh territory' (which is very complicated)

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jewish tankies are one of the most fascinating I don’t think they’ll eat my face say people advocating monkeys eating peoples faces party situations I’ve ever seen

#Yes I do think there’s a strong history of leftism and radicalism and anti capitalism that must continue in the present#Yes I also think the ussr was a violent empire no I don’t think we should wash away#Cultural repression genocide mass murder land dispossession and ethnic cleansing

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine - Ilan Pappé (2006)

#dispossession#The Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine#Ilan Pappé#Palestine#Israel#Free Palestine#Free Gaza#ethnic cleansing#zionism#nsnv#colonialism#atypicalreads#politics#history#state of israel#ideology#nonfiction#Ilan Pappe#west bank#land

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

"the stones cry out. voices of the palestinian christians" / yasmine perni

The Stones Cry Out – Voices of the Palestinian Christians. A film by Yasmine Perni. 56 min. Language: English, and Arabic with English subtitles https://www.thestonescryoutmovie.com

View On WordPress

#1947#1948#dispossession of homes#dispossession of land#ethnic cleansing#genocide#invasion#Israel#Israeli invasion#Nakba#Palestina#Palestine#The Stones Cry Out - Voices of the Palestinian Christians#Yasmine Perni

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Thinkin bout the kid wanting to go west, wanting to pick up a security job, seedling instincts that BW allowed to flourish unabashedly to the skillsets he'd scraped together surviving as some street urchin

#ooc;; mun barks#The way it fell away from him bc he became so fond of ashe - and by extension DL; the way he really didn't think twice abt it#how in another universe he meets gabriel reyes the detective as a fledgling recruit/cadet in LA and learns to protect people#how this would probably all fall apart anyway due to rats and inside jobs and it's the splintering of ovw just w another face#or maybe he makes it to a rural town and takes up sheriff-hood#and yet how there seems to be an inevitability that this will fall apart on him somehow - through some disillusionment -#How some snake will always slither into an eden bc#this is ultimately a small whim of a then-15 year old boy that thinks maybe his bloody hands could do good#(But then - instead - they just got bloodier thru DL)#Thinking abt him saying he'd like to own land one day and work it up to something to be proud of but the way this one#Carries more complications to his tendencies to always be uprooted either by his own volition or outside circumstances#The way he is married to disruption and that This is even less likely to ever be in his cards#but not bc he recognizes this pattern of dispossession but bc he never thought he could accrue the finances#and the way this small little want falls further and further away from him and#how he is so certain that he's going to end up dead in a ditch someplace somewhere someday#it's the way there's these small things of childhood sincerity that managed to survive n persist thru the horrors#but are then proceeded to be strangled out of him n it is a slow suffocation#Thinking abt him thinking abt him thinking abt him

1 note

·

View note

Text

Regarding last post but I think about that so much like. I think about the amount of Blackfullas who tell me "yeah I had to leave Country because it wasn't safe for me anymore" / "I needed affordable living" / "basic healthcare and human needs" and it is a fucking tragedy. It's a fucking tragedy each and every single time. Makes me wild.

#I think about the fact that I left my country town BECAUSE it wasn't safe for me to live there any more#and how absolutely miserable that was and it's NOT EVEN MY COUNTRY. It's wasn't ancestral lands but it had been *home* for a#very long time and it was close to my actual Country and then by leaving for the city I had to leave all of that behind like. It ripped me#apart. It truly did#I don't know I just think that white leftists and leftists who aren't Indigenous proposing further Indigenous dispossession of land as#a ''solution'' to conservative states - towns - areas etc is one of not just intellectual laziness but also genuine apathy#captain's log

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

every time I open Rediker I form new neural pathways. I’m begging any black sails fans (any pirate/age of sail fans tbh, but especially bs) to read his entire oeuvre you will not regret it.

#Marcus Rediker could tell me the x marks the spot cliché appeals to the psyche because of innate human longing from being dispossessed from#the land by the ruling class and I would believe him.#whatever you say marcus. you got it king#ooc. ( ࿐ྂ ) lesjibbities dangereuses.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

"In the hands of some of its most able practitioners, postcolonial scholarship is a potent means of exploring the reworking ("provincializing") of European thought at and for the margins of empire (Chakrabarty 2000, 16). However, most postcolonial scholarship is written out of British or American universities and emanates from the heart of a recently superceded empire or of a recently ascendant one that hesitates to acknowledge its own imperial background. American postcolonial scholarship is not preoccupied with America (Hulme 1995; Thomas 1994172-73). In the background of such scholarship are European theorists, particularly Foucault, Derrida, and Gramsci; in the foreground, European colonial thought and culture. In these circumstances, as many have pointed out, it tends to be Eurocentric - or as the Australian anthropologist Patrick Wolfe puts it, occidocentric (1999,1). So positioned, it is well placed to comment on the imperial mind in its large diversity, and even - especially in the hands of scholars like Homi Bhabha and Dipesh Chakrabarty who grew up in former colonies - on the ways in which European thought has been inflected and hybridized by its colonial encounters, but not on the diverse, on-the-ground workings of colonialism in colonized spaces around the world. A central claim of the distinguished Indian subaltern historian, Ranajit Guha, is that if British historical writing on the subcontinent reveals something of Britain and the Raj, it reveals nothing of India (1997). Somewhat similar criticisms have been made of much of the postcolonial literature: that it (or parts of it) anticipates a radically restructured European historiography, that it allows for nothing outside the (European) discourse of colonialism, that it is yet another exercise in metatheory and in European universalism (e.g., Slemon 1994; McClintock 1994). As the literary theorist Benita Parry puts it, the postcolonial emphasis on language and texts tends to offer "the World according to the Word" (1997, 12)-and the word tends to be European. But unless it can be shown that colonialism is entirely constituted by European colonial culture (a proposition for which it is hard to imagine any convincing evidence unless the concept of culture is understood so broadly that it loses any analytical value), then studies of colonial discourse, written from the center, must be a very partial window on the workings of colonialism.

...

But if the aim is to understand colonialism rather than the workings of the imperial mind, then it would seem essential to investigate the sites where colonialism was actually practiced. Its effects were displayed there. The strategies and tactics on which it relied were actualized there. There, in the detail of colonial dispossessions and repossessions, the relative weight of different agents of colonial power may begin to be assessed. If colonialism is the object of investigation, then the sparse Canadian Shield is promising terrain. It was not detached from London, of course, and may have been profoundly influenced by elements of imperial thought and culture, but the extent of this influence cannot be ascertained in London. Rather, I think, one needs to study the colonial site itself, assess the displacements that took place there, and seek to account for them. To do so is to position studies of colonialism in the actuality and materiality of colonial experience. As that experience comes into focus, its principal causes are to be assessed, among which may well be something like the culture of imperialism. To proceed the other way around is to impose a form of intellectual imperialism on the study of colonialism, a tendency to which the postcolonial literature inclines.

The experienced materiality of colonialism is grounded, as many have noted, in dispossessions and repossessions of land. Even Edward Said (for all his emphasis on literary texts) described the essence of colonialism this way:

Underlying social space are territories, land, geographical domains, the actual geographical underpinnings of the imperial, and also the cultural contest. To think about distant places, to colonize them, to populate or depopulate them: all of this occurs on, about, or because of land. The actual geographical possession of land is what empire in the final analysis is all about (1994, 78).

Frantz Fanon held that colonialism created a world "divided into compartments," a "narrow world strewn with prohibitions," a "world without spaciousness." He maintained that a close examination of "this system of compartments" would "reveal the lines of force it implies." Moreover, "this approach to the colonial world, its ordering and its geographical layout will allow us to mark out the lines on which a decolonized society will be reorganized" (1963, 37-40).

Along the edge of empire that was early-modern British Columbia, colonialism's "geographical layout" was primarily expressed in a reserve (reservation) system that allocated a small portion of the land to native people and opened the rest for development. Native people were in the way, their land was coveted, and settlers took it. The line between the reserves and the rest-between the land set aside for the people who had lived there from time immemorial and land made available in.various tenures to immigrants became the primary line on the map of British Columbia. Eventually, there were approximately 1,500 small reserves, slightly more than a third of 1 percent of the land of the province. Native people had been placed in compartments by an aggressive settler society that, like others of its kind, was far more interested in native land than in the surplus value of native labor (Wolfe 1999, 1-3)."

- Cole Harris, "How Did Colonialism Dispossess? Comments from an Edge of Empire," Annals of the Association of American Geographers, Vol. 94, No. 1 (Mar., 2004), p. 166-167.

#postcolonial theory#postcolonialism#settler colonialism#settler colonialism in canada#dispossession#land theft#materialist history#empire of theory#canadian history#indigenous people#first nations#reading 2024#cole harris

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Palestinian Dispossession Day 76 years ago:

Seventy-six years ago, Zionist militias stormed Palestine, killing 15,000 Palestinians and violently expelling 750,000 more from their villages and lands to make way for the formation of Israel. This is known as the Nakba - the "catastrophe" in Arabic, and many have tried to draw parallels between that historical trauma and the current assault Israel is waging on Gaza. In 1948, more than 500 Palestinian villages were raided and destroyed by militia forces.

...

The war crimes committed by Israel today are the same as 1948 and we are seeing repetitive patterns of barbarism and savagery.

#nakba

#nakba2.0

#palestine#palestinians#gaza#rafah#west bank#genocide#nakba#israeli atrocities#israeli apartheid#israeli occupation#idf terrorists#iof terrorism#war crimes#free palestine#free gaza#justice#right wing extremism#zionism#racism#annexation#illegal occupation#illegal settlements#settler colonialism#dispossession#land grab#annihilation#us weapons#us complicity#israeli apologism#humanitarian crisis

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

"I’m personally a Holocaust survivor as an infant, I barely survived.

My grandparents were killed in Aushwitz and most of my extended family were killed.

I became a Zionist; this dream of the Jewish people resurrected in their historical homeland and the barbed wire of Aushwitz being replaced by the boundaries of a Jewish state with a powerful army…and then I found out that it wasn’t exactly like that, that in order to make this Jewish dream a reality we had to visit a nightmare on the local population.

There’s no way you could have ever created a Jewish state without oppressing and expelling the local population. Jewish Israeli historians have shown without a doubt that the expulsion of Palestinians was persistent, pervasive, cruel, murderous and with deliberate intent - that’s what’s called the 'Nakba' in Arabic; the 'disaster' or the 'catastrophe'.

There’s a law that you cannot deny the Holocaust, but in Israel you’re not allowed to mention the Nakba, even though it’s at the very basis of the foundation of Israel.

I visited the Occupied Territories (West Bank) during the first intifada. I cried every day for two weeks at what I saw; the brutality of the occupation, the petty harassment, the murderousness of it, the cutting down of Palestinian olive groves, the denial of water rights, the humiliations...and this went on, and now it’s much worse than it was then. It’s the longest ethnic cleansing operation in the 20th and 21st century.

I could land in Tel Aviv tomorrow and demand citizenship but my Palestinian friend in Vancouver, who was born in Jerusalem, can’t even visit! So then you have these miserable people packed into this, horrible…people call it an 'outdoor prison', which is what it is. You don’t have to support Hamas policies to stand up for Palestinian rights, that’s a complete falsity.

You think the worse thing you can say about Hamas, multiply it by a thousand times, and it still will not meet the Israeli repression and killing and dispossession of Palestinians.

And 'anybody who criticises Israel is an anti-Semite' is simply an egregious attempt to intimidate good non-Jews who are willing to stand up for what is true."

49K notes

·

View notes

Text

im mostly interested in how many ppl are children of immigrants, so if one of your parents is an immigrant and one isn't, vote parents are immigrants. for previous generations, choose whichever applies to most members of that generation or if that doesn't work, whichever feels most right to you.

say where ur from in the tags!

#aside from that comment fitting one side of my family (unfortunately common here) as a yuro there's nothing on this north american poll#that i can choose besides the last option#and while we're definitely native to this land we thankfully no longer fit the un/western definition of 'indigenous'#aka 'dispossessed stateless minority'#it'd be interesting to see smth like this but excluding countries that began as colonies and with a wider range of options to choose from#cause this is so focused on immigration lol

12K notes

·

View notes