#foreign poetry

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Arabic Language

"حُرّيتي أن أكون كما لا يريدون لي أن أكون."

“My freedom is to be what they don’t want me to be.”

– Mahmoud Darwish (1941-2008)

#arabic#arab#arabic language#arabic literature#arabic langblr#arabic learning#polyglot#foreign languages#langblr#language learning#baghdad#petra#palestine#free palestine#jordan#iraq#calligraphy#arabic calligraphy#poc dark academia#arabic quotes#palestinian poetry#middle east#arabia#bookish aesthetic

217 notes

·

View notes

Text

Italy would fix me 🤍

#italy#italia#call me by your name#cmbyn#thought daughter#girlblogging#letterboxd#target audience#foreign countries#rome#countryside#chemtrails over the country club#country summer#lana del rey#sylvia plath#poetry#brat summer#lorde#big thief#this is what makes us girls#angel#angelic#yearning hours#girl yearning#girl so confusing#delusional

77 notes

·

View notes

Text

Forough Farrokhzad poetry for today

#persian literature#persian poetry#iranian cinema#modern poetry#forough farrokhzad#mahmoud darwish#foreign languages#poetry by women#poems by women#writers of color#web weaving#text post#contemporary literature#litblr#contemporary poetry#sylvia plath#joan didion#virginia woolf#farsi

179 notes

·

View notes

Text

hey! Foreigner! I love you!

#This is from my soul this is from my soul#Why can’t you fucking understand just how deep I feel in this moment#My words hold immortal and eternal meaning#Please please please#this holds far more meaning than even certain poetry#Plz just understand it#no???#will you not even dive into it?#….#the foreigner of which my soul yearns to - a face which is long forgotten#The barrier between languages that kindness still prevails in#YOURE MORTAL AND YET DIVINITY STILL CARES FOR YOU#my eepy ramblings#divine illumination#alterhuman#otherkin#divinekin#Poetic#poetry#my writing

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sometimes your mother tongue isn't always a home,sometimes your childhood place isn't always your wish. Sometimes home resides somewhere far,outside these barriers,of time,age, and languages. And that's okay.

#poetic#my writing#writing#poetry#life#poets on tumblr#spilled thoughts#writers and poets#life quotes#free verse#no land is foreign and no humans strange#no men are foreign#languages#my thoughts#thoughts#my words#words words words#words#humans#humanity#love#spilled ink#spilled words#spilled feelings#feelings#poems and poetry#creative writing#poetry is not dead#poetry is alive#poetry is life

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Loving you was a gift I didn't know how to receive until you showed me."

"At Louis V doing iPhone taps at the register. I just laugh cause..."

LEW

#poetry#poema#life#love#art#heart#romance#romantic#relationships#quote#soulmate#soulmates#true love#couple#lovers#friends#music#lyrics#lew#idk what it is#blue#ocean#foreign car#vacation#nightlife#los angeles#hong kong#laugh#aesthetic#fun

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Minha mãe achava estudo a coisa mais fina do mundo. Não é.

A coisa mais fina do mundo é o sentimento.

Aquele dia de noite, o pai fazendo serão, ela falou comigo:

“Coitado, até essa hora no serviço pesado”.

Arrumou pão e café, deixou tacho no fogo com água quente.

Não me falou em amor. Essa palavra de luxo.

- Adélia Prado, "Ensinamento"

#adélia prado#adelia prado#literature#poem#poems and poetry#poetry#spilled ink#spilled poetry#poem and poetry#poemas#poems and quotes#poesia#poesia brasileira#língua portuguesa#artistas brasileiros#brasil#poesia poema#foreign literature#female poets#female writers#poetas#mujeres poetas#women poets#love#amor#work#work life#family#sentido da vida#meaning

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

I’m so anxious

A Night of Waiting

I’m I sit with screens and glowing maps,

Red and blue in endless gaps.

Each pixel’s shade, a pulse, a sigh,

For dreams I’ve woven deep and high.

I love this land, its sweeping skies,

Yet tonight I watch with wary eyes.

A fear so raw it shakes the bone—

How can I save what feels alone?

Local leaders bicker, fight,

But who will rise to do what’s right?

It feels like Rome, on a brittle edge,

With promises crumbling, once a pledge.

I’ve cast my vote, I’ve done my part,

Yet still this pounding, restless heart.

If only others felt the weight,

Of each decision, each twist of fate.

So here I sit, in shadowed room,

Maps aglow like stars in gloom.

A single voice, but fierce and true,

I love my country—hope shines through.

For though this night is thick and long,

And fear feels sharp, hope still is strong.

So I’ll hold tight, as dawn will bring

Another chance for change to sing.

#foreign policy#journalism#foreign relations#writing#poet#writers and poets#poets on tumblr#poem#original poem#poetic#poetry#general election#elections#election#election 2024#us elections#presidential election#electronic#election day#anxitey#angry#please help#ugh#ughhhh#ugh fml

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

hey guys i have SCOURED the internet and cannot find panda love unit anywhere except for the five songs uploaded to youtube. if anyone out there has the files for the rest of them i would give my entire left arm for them PLEASE. literally u could just post them all on tumblr and ill download them from there i SWEARRR. Thamk you

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

All Means All by Karen Kaiser

#pastormike1976#words#quote#quotes#empathy#sin of empathy#poem#karen kaiser#lgbt#lgbtq#lgbtqia#gay#love is love#all means all#2024#poetry#foreigner#sojourner#stranger#ice#dei#marginalized#member#don't want#club#exclusive#exclusive club#rules#laws#concerned

3 notes

·

View notes

Note

Do you do your translations yourself? I haven't really had the opportunity to talk much with other poets who regularly translate their own work, and I would be interested to know how other people approach it. Keep up the good work!

Hello!

Thank you for the kind words.

Poetry translation is actually a tricky topic. Whether I translate it myself or rely on others (including AI) depends on both the language I'm writing in and the language I'm translating into. Since I'm a native English speaker, I find it much easier to translate from Portuguese and/or Spanish into English.

Translating from my native language, English, into either Spanish or Portuguese is much more challenging. I often have to rely on others or on AI, depending on availability. A lot of this difficulty comes from how dense and deeply literary my writing style is in English, whereas in Portuguese, my writing tends to be simpler. In Spanish, my style is very lyrical—it relies heavily on metaphors and verb tenses that don’t exist in English.

Personally, I’ve found that one of my limitations as a translator is being too literal. Each language carries unique literary nuances that don’t always translate cleanly through a literal approach. Translating between Spanish and Portuguese (or vice versa) tends to be easier because of their lexical similarities. However, English–Spanish and English–Portuguese translations are much more difficult because English developed within a completely different societal, linguistic, and literary milieu than both Spanish and Portuguese, which share common roots in Iberian history, Latin American colonial expansion, and deeply entrenched Catholic tradition.

These cultural and linguistic differences become even more apparent when translating between languages that are vastly different. For example, I speak basic Arabic due to my upbringing in the Middle East. The Arabic language contains an entire ocean of words, concepts, and ideas that are difficult—if not impossible—to translate cleanly into other languages. This is largely due to its unique root system and its deep religious significance as the language of revelation in Islamic tradition.

I try my best with the tools I have, but in my experience, translating poetry is truly an art form. If I ever had the opportunity to publish, I would, without a doubt, hire a professional poetry translator—someone who understands the remarkably difficult task of preserving a poem’s literary essence while optimizing its readability in the target language.

I'd also be curious to hear how you approach translation in your own work—it’s always fascinating to see how different poets handle the same challenge.

Cheers!

✦ @dervishlatino | NNF نشوان نازاريو فيريرا ✦

#poetry translation#translation#translator#translated#phonetics#learning spanish#language learning#langblr#learning languages#foreign languages#polyglot#language stuff#languages#lingblr#spanish#portuguese poetry#spanish poetry#arabic poetry

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ten Dollars

It's one banana, Michael, how much could it cost?

Sixty-three thousand gallons of bunker fuel burned? A couple rainforests? One point seven million dollars for paramilitary terrorists? A few democratically elected governments? Thirty-six years of civil war? A superfluity, raped, tortured, and murdered?

It's one banana, Michael, how much could it cost?

from Sophistry and Solipsism in the New Millennium

#poetry#political poetry#satire#dark humor#imperialism#american empire#capitalism#central america#banana republics#arrested development#writing#original poem#ten dollars#united fruit company#us foreign policy#consumerism#anti imperialism

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

stupid french practice, might delete later

tu as tout ce que je veux

partagerez-vous avec moi?

arrete de penser a toi

je veux que tu penses a moi aussi

tu dis que tu le fais,

mais si tu fait

tu partagerais avec moi

translation/explaination

just a stupid practice poem to learn french lol. there are probably tons of mistakes but im only starting out TT

.

you have everything i want (informal)

won't you share with me? (formally requesting)

stop thinking about yourself (switches back to informal for the rest of the poem)

i want you to think about me too

you say you do,

but if you did,

you would share with me

.

i wanted to make it rhyme, but my french vocabulary is practically non existent.

this isnt even a poem TT just random bs..

#french#french poem#poem#poetry#short poetry#poems#poets of tumblr#languageblr#language#foreign language#learning

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

You had already made your mind against me

To tell my heart to stay with you, how could I do

– Parveen Shakir

#parveen shakir#urdu literature#modern poetry#contemporary poetry#contemporary literature#modern literature#foreign literature#south asian literature#ahmad faraz#faiz ahmed faiz#jaun elia#desiblr#desi blog

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

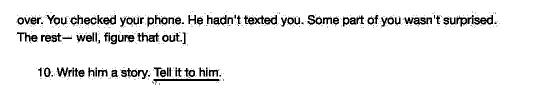

old thing from the Situationship Trenches of 2023. transcript below cut

HOW TO FALL IN LOVE WITH AN AMERICAN BOY

for AL

So let's define x as falling, as love, as boy. The most important rule of loving an American boy is this: to call what you have anything else but what it is.

2. Think about him in a supermarket aisle, holding a pack of cup noodles in the flavour he likes. Think about him as you're rifling through fifty-dollar sweaters with his college crest on them. Think about him in a Subway, a Safeway, a somewhat-kind of-okay well very obsessive way.

3. Tell him that you're in America for Christmas. Make a joke about Walmart, about the weather. Reread his text back a thousand times. Giggle. Twirl your hair. Kick your legs a little, just because you can. So it feels familiar? Of course it does. That's the whole point. ¹

[1: To fall in love with an American boy you have to first resign yourself to cliché. But that's not really right, is it? Resign's such a funny word: both reluctant compliance and forceful withdrawal. To fall in love with an American boy is to willingly make yourself a cliché. To shrink yourself into something easy to define, easy to swallow, a three-act story with a rise and fall. Maybe that's better for everyone involved, you included. Maybe it's better to be Butterfly. Because Butterfly, despite everything, is still a part people want to play.]

4. Buy an extravagant peppermint-gingerbread-mistletoe concoction at an overpriced hipster cafe, just for the hell of it. When they ask for your name—this is important—don't give them your legal name (they'll butcher it) or your English one (you've always hated it). Instead, give them his nickname for you. Pay attention: you don't want to miss them calling it out. An actress always watches for her cue.

5. On long road trips, draft and redraft lines of poetry in your head. Maybe this time you won't forget them the moment you open your notes app. Maybe this line will finally be The One, whatever The One means. Maybe you'll finally be able to explain yourself to him, autopsy yourself, sell yourself like a story: blurbs and back-flaps and signatures and movie tie-in covers. (Plus a pronunciation guide at the back, just in case.) Good poetry, like everything else, has a little bit of performance to it. A little bit of acting. A little bit of lying. ²

[2: So, okay, fine. Let's say it's not love. Let's say it never was. Let's say you just wanted your own personal Beatrice, the wizened mentor who dies to make way for the second act. So what? You can't write about yourself forever, a snake eating its own tail. You used to have real friends. You used to be a good writer. You used to be a good person. Now the most interesting thing that's ever happened to you is a boy. What happened to the Bechdel test, babe? What happened to being a strong female character? Are you even a character at all?]

6. Try and figure out when you stopped being a person and started being a trope. Give up halfway through, and settle for the small stuff instead: When you overhear snatches of accented conversation in the Target aisle, try not to jump to the conclusion that someone’s turned up their Tiktok a little bit too loud. Walk through streets like movie sets and feel a little bit like you've slipped through a silver screen, an unreal thing in a real place. Try not to think that this is the most real you've felt in the last few years.

7. On the morning of Christmas Day, have a spirited conversation with him about your favourite species of dinosaurs. You didn't even know he knew anything about dinosaurs, but apparently the dream-version of him does. You don't know anything about dinosaurs, either, but you would learn everything about them if it meant he would keep talking to you. You don't know when you started talking to your friends more in dreams than in real life.³

[3: He'd kill you if he knew you were thinking of him like this. He'd kill you if he knew you dreamt of him the way you did, the way you still do. Well. Probably not kill, but something close to it. Maybe one of these days you'll stop. Maybe one of these days your predictive text will forget who he is. Maybe one of these days you'll have something to live for that isn't the fact he knows your name.]

8. Wake. He's gone, of course. You're in a sofa bed in a motel somewhere in San Jose. The morning light’s filtering through the blinds. Look at them and think The morning light’s filtering through the blinds, and think, or maybe not filtering, maybe slicing, maybe leaching— in your head open up your notes app, rifle through Dictionary.com. Try and figure out when you stopped writing for yourself and started writing for him.

9. Your parents are still asleep on separate ends of the big bed. For the first time in a week they're not yelling. The room is quiet. Nobody in the world knows you're awake. Nobody's looking at you. Nobody's watching you. This moment is entirely yours, and yours alone. What do you do with it? ⁴

[4: The world is so vast and so small and none of it is real in any meaningful way except for him. You're twelve hours away from home and still every road leads back to the only person you've ever known how to love. Or at least you think you love him. Probably. If not— if not—

What do you do with it? What a stupid question. Is there anything else you know how to do? Despite all appearances to the contrary, this is a story written in past tense: You rolled over. You checked your phone. He hadn't texted you. Some part of you wasn't surprised. The rest— well, figure that out.]

10. Write him a story. Tell it to him.

#i put a lot of this into love songs in a foreign language so im not sure if there's anything new here#actually i don't even think this was a situationship at this point this was just a Situation#writing#poetry#now back to uni apps 🫡

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Poet Who Lost His Writing Hand in The Battle of Champagne

No war has been fought by more poets and artists than the First World War and no war has taken a higher toll on its intellectuals. Few live long enough to see their poetry in print and those who did, all came back wounded from the trenches. One of the survivors was the Swiss modernist and futurist writer and poet Blaise Cendrars. He joined the 3rd Foreign Legion March Regiment in August 1914. Here he became a comrade of Eugene Bullard, one of the three American protagonists of my new book - Fighting for The French Foreign Legion.

Cendrars was an outstanding artistic adventurer constantly seeking new ways of expression in the 20th century, an Elon Musk of writing in his time. But on the first day of mobilisation in August 1914, Cendrars wrote an open letter under the headline “L’heure est grave” in which he urged all friends of France to join the army and fight oppression. The modernist artist stressed that in this dark moment there was no need for words, only action. The letter was published in leading French newspapers and signed by him and 16 other foreign intellectuals, and it is not least because of this letter that thousands of artists living in Paris volunteered to fight in the war without knowing anything about the horrors awaiting them.

At first, Cendras was annoyed that he as a volunteer had to serve in the Foreign Legion and not in the regular French Army, but soon he forgot that and called it with pride “The First Parisian Regiment”:

“We young brainless, enthusiastic or indolent students, poets, painters, journalists, writers, actors, artists of cinema or circus, sons of bankers, manufacturers, engineers, famous architects or workers: hairdresser, tailors, leather worker, upholsterer, bookbinder, shoemaker; or funny or gigolos, restaurant hunters, waiters, hotel employees, nightclub musicians, street sellers, hucksters, anarchists, socialists, revolutionaries, rentiers, race drivers, boxers, gamblers, aviators, night owls, party goers, amateurs, dilettantes, dancers; Montmartrois, Boulevardiers, Montparnos, jokers and pranksters, imposters who made up our 3rd Foreign Legion March Regiment, the most Parisian of all French army regiments, and the most intellectual of all, in short a luxury regiment”

The 3rd Foreign Legion March Regiment had enough artistic talent and innovative thinking to form the avantgarde of the 20th Century - and to some extend it did. But it came with a horrible price. At the Battle of Champagne on 25 September 1915 Blaise Cendrars had his right arm shot off - his writing hand - and he was invalided out of the army. His comrade, a Polish avantgarde painter Moïse Kisling, was wounded several times in the breast at the Battle of Artois a few months earlier and he was similarly sent home. Kisling had a studio in Paris close to Les Jardin de Luxembourg where he allowed friends to sleep over when in town, amongst them one of the heros of my book: Eugene Bullard.

In 1916 Kisling and Cendras collaborated on a book with the title ”La Guerre au Luxembourg”. One thousand copies were printed of this book, which described the horror of the war through the eyes of the children playing in the Jardin de Luxembourg, which you could see from Kisling’s studio.

Cendrars is just one of the hundreds of people I present and describe in my book, and in the research and writing process I have realised how important they were. Europe today is standing on their shoulders.

34 notes

·

View notes