#florio

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Henri Cartier-Bresson - Florio, Ischia - 1952

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

#murkrow#pokemon#new pokemon snap#florio#florio nature park#repost from main#ive posted this before#but i didnt crop out the watermark before#and it bothers me now

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

INCREDIBLE FLOOR

In una delle sale di Palazzo Florio Fitalia a Palermo, si trova un prezioso pavimento in maiolica a petali di rosa realizzato nel 1892 da Filippo Palizzi. Il pavimento è una meravigliosa composizione di petali di rosa sparsi realisticamente su piastrelle bianche.

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Italian influence on English

Italian influence on English Italian influence on English, an article that explains the influence of the Italian language, culture and authors on the English language through the centuries. The Italian language is a Romance language spoken by some 66,000,000 persons, the vast majority of whom live in Italy (including Sicily and Sardinia). It is the official language of Italy, San Marino, and (together with Latin) Vatican City. Italian is also (with German, French, and Romansh) an official language of Switzerland, where it is spoken in Ticino and Graubünden (Grisons) cantons by some 666,000 individuals. Italian is also used as a common language in France (the Alps and Côte d’Azur) and in small communities in Croatia and Slovenia. On the island of Corsica a Tuscan variety of Italian is spoken, though Italian is not the language of culture. Overseas (e.g., in the United States, Brazil, and Argentina) speakers sometimes do not know the standard language and use only dialect forms. Increasingly, they only rarely know the language of their parents or grandparents. Standard Italian was once widely used in Somalia and Malta, but no longer. In Libya too its use has died out. Dante, the main Italian poet, in exile about 1300, began a book meant to guide the development of Italian poetics. He dropped it after a few chapters, but what he finished of "De vulgari eloquentia" contains an explanation in medieval terms of the linguistic map of Europe. In the introduction he begins by stating something obvious to him, and no doubt to his peers, but that might seem strange to us. In most of the world around him, he says, there are two languages in the same place. Call them "low" and "high," or "vulgar" and "classical," or "common" and "learned." Dante calls the first "vulgar" or "vernacular." We moderns can miss something obvious to Dante: we study the language of Cicero and Caesar, and then assume French, Italian, and Spanish descended from that. They didn't. They descend from the common speech of the people going about their lives in the Empire, the "Vulgar Latin," which always was a separate thing from the artificial literary Latin. Dante goes on to make a radical, revolutionary statement, by the way, but a necessary one for his purpose: he identifies the common speech as the more valuable, because the more human. Of these two kinds of language, the more noble is the vernacular: first, because it was the language originally used by the human race; second, because the whole world employs it, though with different pronunciations and using different words; and third because it is natural to us, while the other is, in contrast, artificial.

Dante Alighieri Geoffrey Chaucer, the renowned English poet of the Middle Ages, lived from approximately 1343 to 1400. While there is no direct evidence that Chaucer had personal knowledge of the main literary Italian authors of his time, he was certainly aware of Italian literature and its influence. Chaucer's most famous work, "The Canterbury Tales," includes several stories and characters that are influenced by Italian literature. For example, his story "The Knight's Tale" is based on the work of the Italian poet Giovanni Boccaccio, specifically his work "Teseida," which tells a similar story of love and chivalry. Chaucer also drew inspiration from Boccaccio's "Decameron" for some of his other tales. Additionally, Chaucer was familiar with the works of Dante Alighieri, particularly Dante's "Divine Comedy." Chaucer's "The House of Fame" and "The Parliament of Fowls" show signs of Dantean influence. So, while Chaucer may not have personally known these Italian authors, he was certainly aware of their works and drew inspiration from them, incorporating elements of Italian literature into his own writing. This reflects the broader trend of the influence of Italian literature on English literature during the late Middle Ages and the Renaissance. The Italian Renaissance had a significant influence on English language and culture during the 15th and 16th centuries. This period of intellectual and artistic revival in Italy had several notable impacts. Italian literature in particulary with works by authors like Petrarch and Dante, was translated into English and inspired English writers such as Geoffrey Chaucer. Chaucer's "Canterbury Tales" was influenced by Italian storytelling techniques. Italian humanistic ideas emphasizing the value of individualism, human potential, and classical learning influenced English scholars and thinkers. This led to a renewed interest in classical Greek and Roman texts, which shaped English intellectual discourse. Then Italian Renaissance art, characterized by realism and perspective, influenced English artists and architects. Renaissance ideas can be seen in English cathedrals, palaces, and paintings of the period. In this period the English language absorbed many Italian words, especially related to art, music, and cuisine. Words like "piano," "opera," and "spaghetti" entered the English lexicon during this time. What's more Italian Renaissance advances in science and exploration, such as developments in navigation and cartography, indirectly contributed to the growth of English exploration and the expansion of the English language. Last but not least the Italian Renaissance's political ideas, including the concept of the "Renaissance prince" as described by Machiavelli, influenced English political thought, contributing to discussions on monarchy and governance. In summary, the Italian Renaissance had a multifaceted impact on English language and culture, leaving a lasting imprint on literature, art, language, philosophy, and politics during this transformative period in history.

Italian language and English John Mullan explores how Italian geography, literature, culture and politics influenced the plots and atmosphere of many of Shakespeare’s plays. John Mullan is Lord Northcliffe Professor of Modern English Literature at University College London. John is a specialist in 18th-century literature and is at present writing the volume of the Oxford English Literary History that will cover the period from 1709 to 1784. He also has research interests in the 19th century, and in 2012 published his book What Matters in Jane Austen? So frequent and thorough is Shakespeare’s engagement with Italy in his plays that it has been suggested that he travelled to Italy some time between the mid-1580s and the early 1590s – the so-called ‘lost years’ when we have no reliable information about his whereabouts. There is no evidence to support this claim, but it is clear that Italy was his primary land of the imagination. Unlike other countries – such as France, Austria or Denmark – in which he set particular plays, his representations of Italy are diverse and usually precise. Different cities in Italy are chosen for different plays and given distinct qualities and associations. When he so often chose Italian settings for his plays, Shakespeare was exploiting his contemporaries’ lively interest in the country. It was the destination of many Elizabethan travellers and the subject of many travel writings. (In As You Like It, when Jaques tells Rosalind that he has the ‘humorous sadness’ of a ‘traveller’, she naturally assumes ‘you have swam in a gundello ’ (4.1.19–21). Any serious traveller would have been to Venice.) If Shakespeare did not know Italian, many of his educated contemporaries did. It is likely that he encountered educated Italians in London – he might well have known leading humanist scholar John Florio, an Italian who was tutor to his patron, the Earl of Southampton. Italy had a special hold on poets. The very forms of Elizabethan verse and the terminology of its patterns (stanza, sestina) often came from Italy. The sonnet (from the Italian sonetto) was introduced to English in the 1550s in explicit imitation of Italian models, and especially of the Italian poet Petrarch. In Romeo and Juliet, a play whose very prologue is a sonnet, Mercutio, mocking Romeo for his lovelorn posturing, tells Benvolio to expect from him the poetry of unrequited passion: ‘Now is he for the numbers that Petrarch flow’d in’ (2.4.38–39). The 14th-century Italian poet Francesco Petrarca (known as ‘Petrarch’ in English) was greatly admired in England, especially for his sonnets, which elaborately expressed his hopeless love for the nearly divine ‘Laura’. John Florio was an Italian-born linguist and scholar who played a significant role in influencing the English language through his works. His influence primarily stems from his contributions to English lexicography and his translations of Italian literature. In 1598 and in 1611 he published the first two Italian-English dictionaries: A World of Words, and Queen Anna's New World of Words. Unlike the lexicographers that preceded him, he didn't use just Dante, Boccaccio, and Petrarch, but as a wide a variety of works as possible. This dictionary was a valuable resource for English speakers seeking to learn Italian and helped introduce numerous Italian words and phrases into the English language. It facilitated cross-cultural communication and enriched English vocabulary with terms related to art, music, literature, cuisine, and daily life. This scholar also translated several Italian literary works into English, most notably the essays of Michel de Montaigne. His translation of Montaigne's essays introduced English readers to Montaigne's humanist philosophy and literary style, influencing English prose writing in the process. He is recognised as the most important humanist in Renaissance England. John Florio contributed to the English language with 1,149 words, placing third after Chaucer (with 2,012 words) and Shakespeare (with 1,969 words), in the linguistic analysis conducted by Stanford professor John Willinsky. He was also the first translator of Montaigne into English, the first translator of Boccaccio into English and he wrote the first comprehensive Dictionary in English and Italian (surpassing the only previous modest Italian–English dictionary by William Thomas published in 1550).

Firenze Tuscany Italy Florio was also known for his playful and inventive use of language. He often incorporated puns, wordplay, and creative expressions into his writing. His linguistic experimentation contributed to the development of a more flexible and expressive English language. Some scholars suggest that Florio's translations and linguistic style may have inspired aspects of Shakespeare's works, including the use of Italian words and phrases in Shakespearean plays like "Romeo and Juliet" and "Othello." On December 2020, Bbc aired a documentary titled "Scuffles, Swagger & Shakespeare: The Hidden story of English", in which Dr John Gallagher uncovered the real, complex story of how English conquered the world. John Florio was there too, described as a man who wanted to bring European culture and literature to the English masses. Gallagher reminded the audience that while in Italy and France a renaissance had been transforming art and literature, in England it had struggled to put down roots, and some thinkers were worried that the country was falling behind. But John Florio was determined to change that. He made his mission to bring continental ideas in England. Gallagher showed the difficulties that immigrants faced in Elizabethan England, by reading the words John Florio wrote in 1591: "I know they have a knife at command to cut my throat. An Englishman in Italian is a devil incarnate." Italian literature, and indeed standard Italian, have their origins in the 14th-century Tuscan dialect - the language of its three founding fathers, Dante, Petrarch, and Boccaccio. The thread of literature bound these pioneers together with later practitioners, such as the scientist and philosopher Galileo, dramatist Carlo Goldoni, lyric poet Giacomo Leopardi, Romantic novelist Alessandro Manzoni, and poet Giosuè Carducci. Women writers of the Renaissance such as Veronica Gàmbara, Vittoria Colonna, and Gaspara Stampa were also influential in their time. Rediscovered and reissued in critical editions in the 1990s, their work prompted an interest in women writers of all eras within Italy. Italian music has been one of the supreme expressions of that art in Europe: the Gregorian chant, the innovation of modern musical notation in the 11th century, the troubadour song, the madrigal, and the work of Palestrina and Monteverdi all form part of Italy’s proud musical heritage, as do such composers as Vivaldi, Alessandro and Domenico Scarlatti, Rossini, Donizetti, Verdi, Puccini, and Bellini. Music in contemporary Italy, though less illustrious than in the past, continues to be important. Italy hosts many music festivals of all types - classical, jazz, and pop - throughout the year. In particular, Italian pop music is represented annually at the Festival of San Remo. The annual Festival of Two Worlds in Spoleto has achieved world fame. The state broadcasting company, Radiotelevisione Italiana (RAI), has four orchestras, and others are attached to opera houses; one of the best is at La Scala in Milan. The violinists Uto Ughi and Salvatore Accardo and the pianist Maurizio Pollini have gained international acclaim, as have the composers Luciano Berio, Luigi Dallapiccola, and Luigi Nono. Contemporary productions maintain Italy’s eminence in opera, notably at La Scala in Milan, as well as at other opera houses such as the San Carlo in Naples and La Fenice Theatre in Venice, and the annual summer opera productions in the Roman arena in Verona. Tenors Luciano Pavarotti and Andrea Bocelli were among Italy’s most acclaimed performers at the turn of the 21st century. As Michael Ricci explains in an article, Italian-American citizens have influenced both our language and our society. With the immigration of many Italians to our country, they not only have contributed to our language, but also to our culture. Words used in English that are borrowed from the Italian language are commonly known as loan words.

Venice in Italy Our language contains many Italian loans words. These words encompass many areas of our society like food, music, architecture, literature and art, the military, commerce and banking. The Italian loan words are the most dominantly descriptive in the subject area of our foods. We are all familiar with pizza, ravioli, pasta, bologna (baloney), coffee, pepperoni, salami, soda, artichoke and broccoli, but the more discriminate gourmets might find many other foods and drinks found here to excite their palates. Other delicious offerings are available at many choice Italian restaurants like panini, an Italian sandwich made usually with vegetables, cheese, and grilled or cooked meat. Ciabatta an open textured bread made with olive oil. Foccacia is a flat Italian bread traditionally flavored with olive oil and salt, and often topped with herbs and onions. Fish items are available like calamari, a squid prepared as food; or scampi, which are large shrimp boiled or sautéed and served in garlic and butter sauce. Most people in our society who are not Italian-Americans refer to all kinds of macaroni as pasta; we Italian-Americans like to call them macaroni. Some macaronis are used with soup and are often given to infants because of their small size, like acite de pepe and pastina. Besides servings being given to babies, these are also used in soup. These small macaronis are sometimes used as toppings on salads. Other macaronis like spaghetti, linguini and ziti are cooked in seasoned tomato sauce. Manicotti is stuffed with ricotta or other soft cheeses. Lasagna is a favorite as a baked macaroni, which is layered with cheese, and ground beef baked between the sheets of precooked lasagna. Tortellini is a specialty pasta in small rings, stuffed usually with meat or cheese, and served in soup or with a sauce. Pesto is a tomato sauce consisting of, usually, fresh basil, garlic, pine nuts, olive oil and grated cheese. Many of these meals are topped off with many delicate sweet foods like biscotti, crisp Italian cookies flavored with anise, and often containing almonds and filberts. Tiramisu is a dessert of cake infused with a liquid, such as coffee or rum. Tortoni is a rich ice cream often flavored with sherry. Amaretto is a sweet, almond-flavored liqueur. Maraschino is a bittersweet clear liqueur with marasca cherries. Food words are only the tip of the Italian-American iceberg. Other Italian loan words can be found in music. By far, music seems a topic dominated by Italian loan words. The more familiar musical ones are alto, soprano, basso (voice ranges); cello, piano, cello, piccolo, viola, oboe, violin and harmonica (musical instruments); largo, andagiettio and fermata (musical tempos); crescendo, forte and sforzando (volume); agitato, bruscamente and affettuoso (mood); molto, poco and meno (musical expressions); and altissimo, acciaccatura and pizzicato (musical techniques). Examples in the literature category are novel and scenario; in art, fresca (fresh painting) and dilettante (amateur); in architecture, balcony and studio; in banking, bank and bankrupt; military: alarm, colonel and sentinel; politics: ballot, ghetto and bandit. Italians formerly used balls in their voting, and the word “ball” eventually became “ballot.” Read the full article

#Boccaccio#Bocelli#canzone#Chaucer#cinema#commedia#Dante#Decameron#divina#English#Europe#festival#Florio#food#influence#Italian#Italy#language#latin#literature#music#opera#pasta#Pavarotti#Petrarca#Pizza#poet#Poetry#Renaissance#SanRemo

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

<<Non voglio la solita villa con le colonne, i balconi e le statue. Voglio qualcosa che nessuno ha mai nemmeno immaginato di realizzare, e la voglio qui, perché parli del mondo in cui io sono cresciuto: dovrà essere diversa. Non voglio una villa, voglio una casa che sia la mia casa.>>

Ed è allora che Giachery vede.

Si spalanca l'orizzonte, metaforico e reale.

<<Il mare...>>

<<Il mare. Esatto. E il mondo che c'è oltre, e la ricchezza che viene da esso. Voglio che tutti vedano, e capiscano.>> Vincenzo si ferma. <<Tu non sei nato qui, come me. Hai viaggiato in Europa, hai vissuto a Roma, ma hai scelto di venire qui perché sai che Palermo è il tuo posto. Tu hai capito cosa voglio. Dammelo.>>

E in quella frase è racchiuso un mondo.

(quote: I LEONI DI SICILIA - Stefania Auci)

(pics: Tonnara Florio - web)

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Gambero Rosso 2024 Special Awards Masterclass

Gambero Rosso 2024 Special Awards #Masterclass. #Franciacorta #Amarone #Barolo @GamberoRossoINT @UmaniRonchiVino @PrimosicWines @CantinaTramin @GiovanniRosso @VelenosiVini

Gambero Rosso seminar with speaker Gambero Rosso is an Italian food and wine magazine and publishing group founded in 1986. Last year a selection of people from Gambero Rosso reviewed 2,647 Italian wineries and a total of 25,231 wines, rating them from 1 to 3 glasses according to the quality of the wines. Through a series of blind tastings, 498 wines were awarded their top honour, Tre Bicchieri…

View On WordPress

#awards#biodynamic#Camerani#Cantina Tramin#Enrico Gatti#Florio#Fradiles#Gambero Rosso#Giovanni Rosso#Giuliano Pettinella#italy#Primosic#sustainable#Tenuta Ceri#Terre Margaritelli#Umani Ronchi#Velenosi

0 notes

Text

Phaeton to his Friend Florio

William Shakespeare (?)

Sweet friend, whose name agrees with thy increase How fit a rival art thou of the spring! For when each branch hath left his flourishing, And green-locked summer’s shady pleasures cease, She makes the winter’s storms repose in peace And spends her franchise on each living thing: The daisies spout, the little birds do sing, Herbs, gums, and plants do vaunt of their release. So when that all our English wits lay dead (Except the laurel that is evergreen) Thou with thy fruits our barrenness o’erspread And set thy flowery pleasance to be seen. Such fruits, such flowerets of morality Were ne’er befroe brought out of Italy.

0 notes

Text

Vino Liquoroso Marsala Vergine Baglio Florio 2001 (Cantine Florio - Duca di Salaparuta Spa)

#baglioflorio#cantineflorio#degustazione#ducadisalaparuta#florio#ilvinoeoltre#marsala#marsalavergine

0 notes

Text

A Terni l’élite dei calzolai: da Metelli a Florio e la sua raccolta di “santini speciali”

Storia e Memoria di SERGIO BELLEZZA Il collezionismo per gli Italiani più che un hobby, è una vera e propria mania. Collezionano di tutto: dagli oggetti d’arte alle scatole di fiammiferi, dai trenini elettrici ai modellini d’auto, dai soldatini di piombo alle figurine, dai vecchi giornali agli antichi amanuensi. … Leggi tutto_>>

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Night is the mother of thoughts.

-- John Florio

(Bern, Switzerland)

#night#thoughts#life#john florio#travel photography#bern#switzerland#rooftops#night photography#quote#photography

362 notes

·

View notes

Text

Strome and McMichael spilling the tea that Dewey only barks for a select few guys. (Pro and Franky and the various Bears. But tragically, not McMikey anymore.)

#'Because that's how much he loves the boys.'#Dylan Strome#Brandon Duhaime#Connor McMichael#Aliaksei Protas#Ethen Frank#Washington Capitals#Katie Florio#The Line Change

141 notes

·

View notes

Text

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Daniel Ricciardo photographed at the wheel of a 1972 Alfa Romeo T33 at the Targa Florio | December 2014 | Jim Krantz

The Targa Florio, a legendary road race in Sicily that was first run in 1906, is renowned for its breathtakingly narrow roads winding through towns and mountains, making it both exhilarating and perilous. With his Sicilian heritage, Ricciardo embraced the challenge of racing the course in the very car that Helmut Marko once drove to set a lap record.

#the targa florio series of photos of daniel are some of my all time favourites#but I'd never seen these ones before. They're not included on the RBCP photos - maybe the photographer has exclusive rights to these ones?#either way first one is insaaaane#although I will say seeing him sitting in a red car in Italy does make me revisit my ferrari daniel what-ifs 🙃#daniel ricciardo#dr3#2014#targa florio#red bull daniel

132 notes

·

View notes

Text

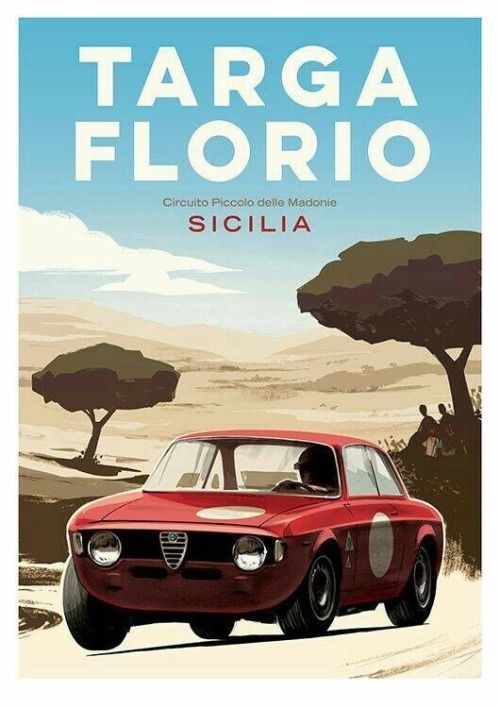

#lifestyle#roadtrip#autos#classic car#targa florio#alfa romeo#sicilia#sicile#italia#italie#historic rally

99 notes

·

View notes

Text

Giorgio Scarlatti & Pietro Ferraro - Ferrari 250 GTO - 4ème de la Targa Florio 1962. - source Moto Vitelloni - Wheels n' wings.

87 notes

·

View notes