#censorship of fairytales

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

The Yaga journal: Baba Yaga in Soviet movies

And we reach the final article I will translate from the “Yaga journal”: Baba Yaga sur l’écran soviétique (Baba Yaga on the Soviet screen), by Masha Shpolberg!

In 1979, the Soviet studio Soïuzmultfilm produced a three-part cartoon for the Olympic Games that had to happen the following year. The first episode opens with a choir of journalists proclaiming in all the languages of earth: “Micha the bear-cub was just elected Olympic mascot of Moscow”. Baba Yaga listens to this in her cabin, and becomes enraged: “Why him? Why him and not me?”. “Everybody agrees to it!” the journalists say. “And Baba Yaga is against it!” she says, before attacking the television screen with her broom. Throughout these three short episodes, the “Baba Yaga is against it!” cartoon tells the various attempts (and failures) of Baba Yaga and her assistants (Zmeï Gorynytch and Kachtcheï the Immortal) to prevent Micha from reaching the games. The plot relies on the omnipresence of Baba Yaga in the Soviet imagination, and her importance as a symbol of folk-culture. However Baba Yaga did not always have such a status. The witch and her tales were banned by the Soviet Union soon after its creation. Starting in 1918, the year of the creation of the komsomol or “union of Leninist-communist youth”, the Soviet Party reorgaized the educational system: it was decided that fairytales had no place in education. Its rural and pagan roots were problematic for a State which wanted to create an industralized and rationalized world. Galina Kabakova explained that on one side, the fairytale did not carry the values of the new society, and on the other the marvelous and fantastical was considered toxic for the minds of the youth that were to build socialism.

The persecution of the fairytale knew its peak in 1924, when Nadejda Krupskaïa , the companion of Lenine and the president of the Glavpolitprosvet, the Central Comity in charge of Political Education, demanded that all public libraries got rid of the books “with a negative emotional or ideological influence”, as well as the books that “did not conform the new pedagogic approach”. This included the fairytale books of Afanasiev. As the cultural historian Felix J. Oinas explains, in the beginning of the 20s several Soviet critics argued that the folklore was carrying the ideology of the dominant classes, which in turn led the proletarian literary organizations to receive very negatively folktales and fairy tales. A special section of the Proletkult for children even attacked fairy tales based on their “glorification of the tsars and tsarevitchs”, claiming that they were “reinforcing bourgeois ideals” and “causing unhealthy fantasies” in children. When the fairytale re-appeared in the middle of the 30s, it was because the Soviet political culture had decided to re-appropriate the Russian folklore for itself. Just like the Romantic nationalists of the pre-Revolutionnary era, this ideological turn aimed at melting the personal identity in a vaster, collective identity. And what was the best medium to do it? Cinema. Alexander Prokhorov, in his “Brief history of the Soviet cinema for children and teenagers”, explained that the cultural administrators of Staline changed their view on folk-culture, and the fairy tale became a legitimate cinema genre since it helped visualize the spirit of the miraculous reality proclaimed by the Stalinian culture. The end of the NEP, in 1928, also put an end to the importation of foreign movies, freeing the Soviet cinema from all competition - and of all commercial goals.

In 1934, during the first congress of Soviet writers, Samouil Marchak and Maxime Gorki insisted on the importance of childhood literature for the creation of a new Sovietic man, and in 1936 the Sovnarkom, the highest governemental authority, established two new studios out of the ancient Mejrabpomfilm: Soïuzdetfilm, for children movies, and Soïuzmutfilm, for cartoons. It is in this political and institutional context that the young moviemaker Alexandre Ro’ou (in English his name is spelled “Rou”) decided that, for his first film in 1937, he was to adapt a very famous fable, “Wish upon a Pike”. The success of this movie allowed here to adapt a fairytale, more complex on an ideological level: Vassilissa the Beautiful, in 1939. Through this movie he became the “founding father” of the genre of the cinematographic fairytale. It is in this movie that Baba Yaga made her first appearance in cinema, played by a man - Guéorgui Milliar. Throughout the next thirty years, Milliar would play Baba Yaga in three other movies of Ro’ou: in Morozko (1964), in “Fire, Water and Brass Pipes” (1968) and in “The Golden Horns” (1972).

In this article, the author will analyze the evolution of the character of Baba Yaga throughout these four movies - based on the social and political context. While always created by the same movie-maker, and played by the same actor, Baba Yaga is never the same character in these movies. Throughout the years she is slowly “domesticated”: from a macabre and intimidating force of nature, she becomes a vain hag, more superfical than wicked, from a relic of the past, she becomes a modern mascot. By analyzing the narrative and aesthetic choices causing this transformation, the author wants to analyze the allegories of each movie in their historical context.

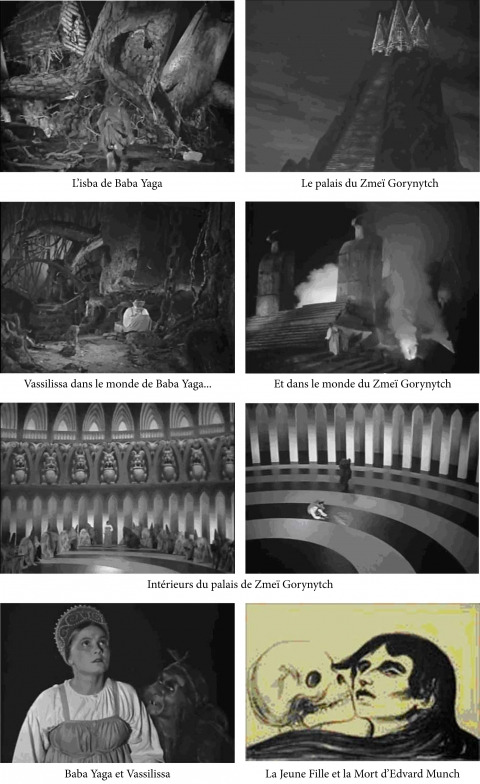

I) Baba Yaga in the Stalinian era: Vassilissa the Beautiful (1939)

Vassilissa the Beautiful, a movie adaptation of the story “The Princess-Frog”, was conceived as much as an entertainment as a teaching tool. In the version of Ro’ou, Vassilissa is not a princess and Ivanouchka is not an idiot. The two are rather hard-working, intelligent, honest people. The brothers of Ivanouchka oppose the duo by the women their find as wives: an excentric aristocrat, and a gluttonous merchant’s daughter. The entire first part of the movie presents an allegory of the fight of the social classes. The brothers and the wives do nothing while Ivanouchka goes hunting and Vassilissa does the chores, and then they pretend to have done the honest workers job.

Baba Yaga only appears in the second half of the movie, when the wives burn the frog skin of Vassilissa, and the maiden is ravished by Zmeï Gorynytch. A title-card mentions “In the land of the Zmeï, Vassilissa the very beautiful was guarded by Baba Yaga”. Traditionally, the role of kidnapper in Russian fairytales is played by Kachtcheï the Immortal, who doesn’t appear in the movie - but the Zmeï here fills his role as “the rival of the male hero for the hand of the woman, usually a fiancée or a wife, sometimes his mother” and “the male counterpart of Baba Yaga”. So, as much in their home as in the magical land, Ivanouchka and Vassilissa must fight against oppressors that take away their goods and exploit their work. Jack Zipes noted that, according to the marxist reading of the fairytales, Baba Yaga symbolizes “the entire feodal system, where the greed and brutality of aristocracy are responsible for the hard living conditions. The murder of the witch is the symbol of the hatred felt by the peasants against this aristocracy, that hoards and oppresses.” However, in the Vassilissa movie of Ro’ou, Baba Yaga plays a more ambiguous role. Her skinny and nervous figure, the rags she wears, allows her to hide herself in nature. Her hunched back imitates the rocks, the way she spreads her arms and legs imitated tree branches. By fusing with the landscape, she can attack Ivanouchka without ever being seen by him. Often Ro’ou likes to superposition to allow Baba Yaga to appear and disappear suddenly. As a result she seems half-translucid in many scenes, suggesting that she is a force of nature - or even the personification of the forest.

The “magical” part of the movie plays on the contrast between the domain of Baba Yaga (the forest) and the domain of the Zmeï (the mountain). The two realms are heavily inspired by the expressionist cinema of Germany (especially the sets of the Cabinet of Doctor Caligari, in 1920), but couldn’t be further from each other. The world of the Yaga is the one of the dark forest, confusing and threatening, but deeply organic and human. The world of the Zmeï, however, is an industrialized, hyper-sanitized, geometrical world. A post-human world, or one devoid of humanity: a fascist world. Indeed, the historical context of the movie invites an allegorical reading: the Germano-Sovietic Pact was signed the 23rd of August 1939, and the movie was released the 13th of May 1940, one year before the Nazi invasion of the Soviet Union in june 1941. At the time, while Germany wasn’t an official enemy (and it is hard to imagine that Ro’ou selected this tale with a political purpose in mind). But the movie is a proof of the tension that existed at the time about the entire situation. Baba Yaga, who keeps turning and roaming around Vassilissa, reminds of the painting of occidental paintings, “Death near the Maiden”. It isn’t just the virginity of Russia (aka, the integrity of its frontiers) that are threatened - it is her very life that is at play.

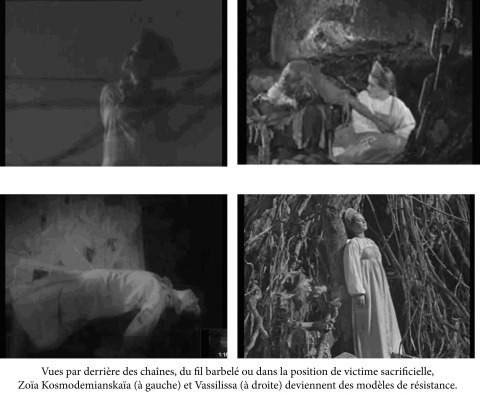

Vassilissa, a girl who is obedient and modest when she is free, becomes proud and rebellious in captivity. She is a model of resistance that anounces the true female heroes of the Second World War in Russia, such as Zoïa Kosmodemianskaïa (made famous by the movie of Leo Arnchtam in 1944). Just like Zoïa, Vassilissa is ready to sacrifice herself for the good of others, and to follow her own principles. When Baba Yaga discovers the hat of Ivanouchka in her isba she aks Vassilissa “Where is he? You say nothing? If you say nothing, I will make you talk. Maybe fire will make you more talkative.” Vassilissa is only saved from torture by the arrival of Zmeï Gorynytch.

The analogy between the monster and the foreign invader is reinforced by the third cinematographic fairytale of Ro’ou, Kachtcheï (Koschei). Filmed in the Altaï and the Tadjikistan in 1944, and released the day of the victory (9th May 1945), the movie tells “how Koschei the Immortal fell onto Russia like a thunder clap in a peaceful sky, burned out houses and our bread, massacred the population and took away thousands of women”. Even if the historical facts cannot allow us to read “Vassilissa” as a simple allegory of the war to come, the images still carry the possibility of an upcoming conflict. We can read it in the presentation of Vassilissa as a resistant-model, as much as in the glorification of the elements of folk-culture (aka, part of Russian culture). The movie is also preceeded by a prologue in which three bards introduce the tale by playing gousli (gusli), a traditional musical instrument. When Ivanouchka goes searching for Vassilissa, the text says “He wandered for a long time throughout his native earth” - even the typography of the title-cards reminds the medieval books. All these elements create throughout this movie a new “nationalist vocabulary”, and so unite a nation threatened by an external force. As Prokhorov explains, “The movies of Ro’ou, just like the kolkhoz musical comedies of Ivan Pyr’ev, were answered an official demand of art inspired by the narodnost (popular spirit/folk spirit)”, an art that “allowed the entire Soviet community to stay in touch with their popular spirit, as the metaphysical source of the communal strength”. The internationalism of the first years of the Soviet Union was slowly breaking down in front of this romantic and deeply essentialist view of the nation.

II) Baba Yaga throughout the Thaw: Morozko (1964), Fire, Water and Brass Pipes (1968) and The Golden Horns (1972)

The period that followed the war was once again difficult for the fairytales, and all those that studied folk-culture. Félix Oinas explains: “After the war, the Russian folklorists knew another series of trials, perhaps the most difficult of them all. The era of the ideological dictatorship of Jdanov, nicknamed Jdanovchtchina, started in 1946, and quickly became an anti-West witch hunt”. Vladimir Propp had just published “The historical roots of the fairy tale”, which was heavily criticize due to containing numerous quotes of Western folklorists, as well as comparativist ideas, not to say cosmopolite ones. In 1947, Soïzudetfilm was re-organized and became the Gorki studo: the studio however did not have any order or demand for children movie. In 1952, the situation led Constantin Simonov and Fedor Parfenov to publish an open letter in the Literaturnaïa gazeta “Let’s resurrect the cinematography for children”. However it was only in 1957, after the death of Staline and the succession of Khrouchtchev, that the minister of culture finally commissioned an augmentation of children movie production. In 1961, the Gork studio was named “Gorki central Studio of cinema for children and the youth”.

When Ro’ou produced Morozko, in 1964, it was in conditions very different and yet paradoxically very similar to the ones in which Vassilissa the Beautiful was produced. The first novelty was the use of color: the second half of the movie takes place in winter, which forces a restrained color palette, even in the makeup and costumes - it is limited to the red and pale blue of the traditional Russian paintings. The appearance of color makes the Baba Yaga younger, as well as more visible in the landscape - but it doesn’t make her more lively. When Ivan discovers the isba in the middle of the forest, and when said isba obeys his order for it to turn towards him, he is sincerely surprised. Baba Yaga gets out of the house yawning, and she asks grumpily “What do you want? Why, unexpected, uncalled, did you dare turn the cabin and wake up the crone?”. It is almost as if everyone in the story was forced in their part of the story against their will. If the Yaga of Vassilissa was jumping from tree-top to tree-top, but the Yaga of Morozko keeps complaining about back problems and she asks Ivanouchka to leave her alone. She only does magic because Ivanouchka forces her to, and her speech is filled with affective diminutives ending in -tchik. Ivanouchka, in the end, doesn’t need to vanquish Baba Yaga, he rather has to convince her to help.

The male equivalent of Baba Yaga, Morozko (Grandfather Forest / General Winter) turns out to be just as harmless as the witch. When he sees Nasten’ka, abandoned by her family to die of cold in the forest, he immediately comes to her help. The role of the two magical characters (Morozko and Baba Yaga) in the life of the young protagonists is limited to the one of a godfather or godmother. The equivalence of these two relationships is highlighted by a sequence which puts in parallel Morozko putting warm clothes on Nasten’ka and Baba Yaga doing the same for Ivanouchka. Another parallel can be found in the way the protagonists call their helpers: Ivanouchka calls Baba Yaga “Yagusia” or “Babulia-yagulia”, while Nastenka calls with affection Morozko “Morozouchka-batiouchka”. From villains, Morozko and Baba Yaga are transformed into helpers, the Donors of the Vladimir Propp’s functions.

The most important consequence of this transformation is the new nature of the “source of Evil”. Evil doesn’t come anymore from what is supernatural, but it rather comes from what is too natural: the flaws of ordinary humans. It is the jealousy of Nasten’ka stepmother and the boasting of Ivanouchka that cause their initial separation and the unbalance that Baba Yaga and Morozko try to remedy to. The qualities preached by Morozko are very close to the ones glorified by “Vassilissa the Beautiful”: hard-work, modesty, and intelligence. What is different is the goal of these virtues: the seriousness and gravity of “Vassilissa the Beautiful” is gone. In Morozko the characters are funny and light-hearted. Ro’ou was trying in “Vassilissa” to animate the visual popular culture, inherited from the lubok and illustrated movies. But in Morozko it all becomes a great show, a smooth surface without any depth. When Ivanouchka leaves his birth-house to go seek his fortune, he passes by a group of young girls that dance and sing when seeing him - these are traditional dances and songs, but the aesthetic is much closer to the one of a technicolor musical than a medieval fantasy.

“Fire, Water and Brass Pipes”, filmed by Ro’ou four years later, in 1968, goes even further in the idea of a show or entertainment. Caracterized by saturated colors and random explosions of music and dance, the movie is aiming at the audiovisual variety show at the cost of the stylistic coherence. This excess alos manifests at the narrative level: while Morozko reunited two distinct fairy tales (Morozko and Ivan-with-the-bear-head), “Fire, Water and Brass Pipes” is a sort of remix of elements taken from numerous myths, cultures and legends (not even all Russian!). The skeleton of the plot is roughly the same: as usual, Kachtcheï kidnaps the beloved of Ivanouchka, and he must undergo a series of trials to get her back. These trials, symbolized by the fire, water and brass pipes of the title, are so many occasions to introduce very different elements, ranging from Greek philosophers to the god Neptune.

In this movie, Ro’ou also modifies the traditional structure of his cinematic fairytales in another way: instead of beginning by the human drama which starts the plot, he begins by the presentation of the magical beings. It is in this “prologue” that we have a full humanization of Baba Yaga: she becomes a mother, and is shown to be able to feel empathy and sorrow. The movie opens with Baba Yaga flying through the sky, rushing to the wedding of her daughter with Koschei the Immortal (also played by Milliar). When she arrives, she is humiliated twice. First, she fails to land properly, implying she can’t move as she used to. Then, nobody recognizes her at the court except for her own daughter and Koschei. This is quite revealing that in this context she introduces herself not as Baba Yaga, but as a relative of the happy couple: she joyfully says (rhyming in Russian), “I am the mother of the bride, Koschei the Immortal is my son-in-law”. This image of Baba Yaga as a mother is not taken out of nowhere: already in the story of Afanassiev called “Baba Yaga and Small-One”, the witch had forty-and-one daughters, that died by her hand. In the movie of Ro’ou, a new importance is given to her maternity as well as to her physical problems (she handles her mortar badly, she falls every time she tries to dance): it all indicates that maybe the life of a witch can be affected by the flow of time. This Baba Yaga is implied to have always been as she is now: she lived a period of youth, and now she is aging. So her life can have a beginning... and an end, like the life of all mortals.

The prologue that presents the maternity of Baba Yaga also has a role in the narrative of the movie: it explains why the Yaga is so willingly helping Vasia (the new name of Ivanouchka). Indeed, when Zmeï Gorynytch offers Koschei a magical apple that makes him young again, he sends away his bride, deeming her too old for him, causing a public humiliation. By helping Vasia defeating Koschei and freeing his beloved (Alionouchka), Baba Yaga is actually avenging her own daughter. She needs Vasia as much as Vasia needs her.

The Golden Horns, made in 1972, thirty-tree years after Vassilissa the Beautiful, was the last movie of Ro’ou that uses the character of the Baba Yaga. After being reduced to a second role in Morozko and “Fire, Water and Brass Pipes”, she finally regains a prominent role. Queen of the forest, she has no rival except for the deer with golden horns - as she complains to a group of hunter, the deer keeps undoing all of her traps and ruining her projects. She doesn’t have back problems anymore, and she is healthy enough to dance and sing. Indeed, throughout the movie she keeps insisting that she is still young. In the beginning of the story she is playing cards with a friend, Duraleï. When he accuses her of cheating and calls her “old hag”, she throws him away from the isba and she says to herself “He dares to call me hag, me, who everybody says has a young soul!”. The Baba Yaga of The Golden Horns isn’t wicked, but she is vain - she is a pretentious old woman that spends hours in front of her mirror. The three young lechïï that serve her constantly flirt with her, and calls her by the diminutive “Babou-yagusen’ka”, and the witch herself flirts with a group of hunter-robbers. Baba Yaga even has a musical number, a song throughout which she turns her hand-mirror into a guitar and sings “I can’t see her enough, Yaga the Fair / Oh my love, me, me me!”.

Beyond the changes brought to the very image of Baba Yaga, Golden Horns is different from the previous movies in two main aspects. The first: the question of the relationship between genders. In Golden Horns, it isn’t a young man who tries to save his beloved from the hands of Baba Yaga or Kachtcheï. It is rather a mother, Evdokia, who tries to save her children. The final conflict is one between two women: one a mother, the other (the Yaga) an old maid. As a result the values of the more are much more conservative in nature. The song of the young girls in the prologue, with the title-cards, compare Russia to a mother. “Always happy, and a bit sad / So is Russia, my mother. / Like the fairytale, intemporal and kind / So is Russia, my mother”. It is this same Russian earth that protects Evdokia in the final battle against Baba Yaga. As the Yaga takes weapons, Evdokia remembers a small bag of soil her neighbor gave her. “Native earth, protect me!” she screams as she throws the soil towards Baba Yaga. These two sequences insist on the sacred nature of the Russian land, “mother” of the people and symbol of maternity itself. The movie implies that it is Evdokia’s maternity that makes her invincible, and that it is the vanity (the “wrong use of her gender”) that dooms Baba Yaga. The absence of a father figure also helps the manifestation of more conservative political messages. It is possible to read Evdokia as a feminist figure: she is independant, and she goes searching for her two daughters without fear. She is intelligent and strong: she isn’t even shocked when she learns she must battle Baba Yaga in a sword-fight. However, she is continuously guided and helped by masculine figure in positions of authority: the Sun, the Wind, and Golden Horns. Golden Horns also offers the perfect example of a theory brought by Evgueni Margolit and summarized by Prokhorov: “Soviet cinema expressed the ideal community of the future as a land of children, where the government filled the role of the strong, order-giving father of the people”. Evdokia, the figure of the mother, is thus treated like a child by the figures of the Father.

In conclusion, this movie offers a new definition of the political action. Like in most fairytales, the movie starts with a transgression: the twin girls of Evdokia, Machen’ka and Dachen’ka, disobey their mother’s instructions and go too far in the forest. What they cannot know is that two wicked spirits trap them, and use them to start a revolution against the Baba Yaga’s tyranny. The movie ends with a tribunal, formed by the small children-wood spirits, alongside the former friend of Baba Yaga, Duraleï. Through a vote, they decide to punish Baba Yaga by banishing her to the swamp. The events of this tale must thus be understood in a wider context, that is seen at the beginning of the movie: this movie represents a shift of powers in the forest, and is the triumph of the humble people, of the simple folks against the monarchy.

Conclusion

In “Vassilissa the Beautiful” (1939), made before the movie, Ro’ou tries for the first time to give a cinematographic shape to the world of the folktales. Taking inspiration from the iconography of the lubok, of the illustrated book, and of the German expressionism, he creates a ciaroscuro universe filled with heavily connotated characters, all either wholly good or wholly evil. Baba Yaga, in this universe, like in the one of fairytales, according to the interpretation of Propp, is a liminal character, the guardian of the frontier between the known and the unknown. Often camouflaging herself in the forest and the rocks that surround the isba, she embodies the dark side of the nature. In a movie whose goal is to enrich the nationalist vocabulary of a land threatened by an external force, Baba Yaga becomes a problematic figure, at the same meant to be “one of us”, since she is part of the Slavic folklore, but also “one of them” since she is unpredictable and hostile.

In the three movies realized by Ro’ou one after the other during the period known as the “Thaw”, the Baba Yaga of Vassilissa is domesticated, becomes a satire, her fangs are removed to make people laugh. While these movies keep feeding from the imagery of Russian nationalism, and keep trying to maintain the authority of the State, they are aimed at being more of an entertainment than a mystical communion with the soul of the people. By giving to Baba Yaga a biography - children, love interests, a passion for clothes and other fashions - these movies remove her from the mythological world, and give her a place in the contemporary world. It is how she becomes, at the time of the Olympic games of 1980, a cult figure, a legitimate rival to Micha the bear-cub for the title of Soviet mascot.

#the yaga journal#baba yaga#russian fairytales#alexander rou#soviet movies#fairytale movies#censorship of fairytales#literary censorship#banning of fairytales#russian folktales#vasilisa the beautiful#the golden horns#morozko#fire water and brass pipes#georgy millyar#baba-yaga

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Now Ladybird’s fairytales get the ‘sensitivity reader’ treatment: Classics like Cinderella and Sleeping Beauty to be re-examined after being branded 'outdated or harmful' for lack of 'inclusivity' and 'problematic tropes'

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Went to a pub and Fairytale of New York played uncensored. I just heard it uncensored again on Spotify. I think the gammons of England are just making shit up.

0 notes

Text

0 notes

Text

WEIBO 📼

230808 JUN

🐱 Exclusive fairytale with JUN

#seventeen#seventeen (세븐틴)#jun#exclusive fairytale#seventeen updates#17 todate#huihuis our strongest soldiers fr#like do I need to put a censorship on here😭 can I even do that

0 notes

Text

[Arcane preference] with a s/o with a mental issues pt.2 (the big sad)

Requests with sensitive themes are reposted with names that hint at the topic but aren’t explicit, to avoid censorship. On another note, I’m taking advantage of this post to promote myself and let you know I’m working on a mini-series of Arcane posters. Right below the "read more" line, you’ll find the link to two drawings and my other socials if you’d like to follow me elsewhere! Enjoy!

socials: | INPRNT | | Tip Jar | | X | | BlueSky |

poster: | Jayce poster | | Silco poster | | Steb poster |

Jayce:

- The panic man, but not in this scenario.

- He usually notices a crisis brewing before it’s too late, and when he picks up on the signs, he intervenes immediately.

- He’ll take you out for a walk to get some fresh air, clean the house thoroughly, and make sure to open the windows to keep everything well-ventilated.

- Breakfast? In bed. Lunch? Strategically either at your favorite spots or something he cooks himself—things he knows you can’t resist.

- If the crisis worsens, he’ll help you with dressing, making the bed, and even brushing your teeth if necessary, without making you feel bad about it.

- He refuses to let you languish and is convinced that fresh air, a refreshed you, and clean, fragrant clothes will help you feel better much faster.

- Get ready for some storytelling from any fairytale book he can get his hands on.

Viktor:

- He completely understands what you’re going through and notices it fairly quickly.

- Viktor will be the first to personally help you while also suggesting someone who could support you—not because you’re a burden but because he genuinely wants you to feel better.

- There’s no shame in asking for a little help.

- Whether you’re up for it or not, he won’t push you, but he’ll try to stay as close as possible.

- He insists on boundaries, though. Not hungry? At least two full meals a day.

- Struggling with hygiene? He’ll buy you wipes, and if needed, he’ll assist you with washing.

- He doesn’t want you to neglect your tasks, self-care, or well-being for fear that it might worsen the crisis or weaken you over time.

- If you don’t want to go out, it means you’ll watch a series together—or maybe two. He’ll work on his projects at night, but you’ll never know about it.

Ekko:

- Ekko notices it less quickly than the others, not because he’s emotionally clueless but because in Zaun, feeling unwell is both common and a part of daily life.

- He’ll pick up on it when you become less communicative, when he doesn’t see you around, and when he finds you lying in bed all the time.

- He’s the least likely to push you. Don’t feel like eating? He’ll bring a plate along with some treats he’s managed to scavenge and leave them in your room so that if you change your mind, you won’t have to get up.

- Really hungry? He’ll cook for you personally before you even ask, as soon as your stomach growls.

- Can’t bring yourself to wash? You’ll do it when you feel better—there’s no rush, no pressure. No matter how messy your room gets or how much you stay confined to that tiny space, he won’t make you feel bad about it. He’ll ask if you want to take a walk, visit the kids, or suggest plans to stimulate you.

Vander:

- The man who managed the entire Undercity, four criminal kids, the mines of Zaun, and the enforcers doesn’t back down from this challenge either.

- His approach is to never leave you alone.

- In the morning, he’ll dress you, comb your hair, and carry you to the bar. If he has to visit Benzo or go elsewhere, he won’t leave you alone for even five minutes.

- His reasoning isn’t fear that you’ll get worse but rather the belief that having stimulation without exhausting yourself will help distract you a bit.

- If possible, he’ll take you to the bridge, maybe for a picnic.

- You’ll always have a smoothie to drink so that, even if you don’t feel like eating, you can still get nutrients. At the same time, there will always be a plate of food on the table.

- Breakfast? Wherever you want. The other meals? In the living room or at the Last Drop, so the air in your room can be refreshed.

Silco:

- Before you even realize you’re having a crisis, he’ll leave some pills on your bedside table with a note explaining how to take them.

- His goons—at least the younger ones—are almost like his children, so he’s used to this kind of situation and already has everything prepared.

- If you lock yourself in your room, he’ll respect that; you need your space. But if it goes on for too long, he’ll feel compelled to intervene, if only to make sure you’re not wasting away.

- He’ll ask Sevika to take care of you when he can’t—though she won’t be thrilled about it. Still, the kingpin doesn’t want you to feel neglected or entrust you to someone unreliable or incompetent.

- He’ll adjust his work schedule to spend more time with you, though his requests will often feel more like polite orders.

- In Zaun, there aren’t good doctors to turn to, so if the choice is between letting you get a rash, an infection, or washing you himself, he won’t think twice about doing it.

- On the other side, he becomes much more affectionate. He’ll have you sit on his lap while he’s in his office and keep physical contact constant when you’re together, so you always know he’s there for you.

Jinx:

- “You’ve got the Big Sad,” as she calls it, speaking as someone with plenty of problems and few diagnoses.

- Her approach is also a way of exorcising the illness, making it less scary.

- Her main method of helping is cleaning and decorating her lair to make it brighter and more colorful, with cheerful music playing in the background and colorful lights stolen from Piltover.

- If you feel up to going out, she’ll take you to Piltover, where the air is cleaner, there’s more sunlight, and you can soak up some oxygen and vitamin D. If not, she’ll steal anything she can—fruit, toys—so you have something to engage with.

- When it comes to meals, she’s not great at managing herself. She often forgets to eat, and it’s her father who forces her to have complete meals. As a result, most of the edible things she’ll bring you are cookies, chips, pizza—tasty but not necessarily nutritious.

- The important thing is that you eat.

- She’ll try to negotiate with her father to skip missions for a while to stay close to you or go on them at night so you won’t notice her absence.

Vi:

- She doesn’t catch on too early but notices just before things worsen. She becomes very protective and more careful and kind in her actions, simply to avoid upsetting you.

- Out of personal guilt, she won’t let you know if she gets hurt, to prevent you from worrying or feeling bad about receiving help.

- If you drop something, she’ll immediately stop whatever she’s doing and come to you. First, she’ll reassure you that it’s okay—it happens to everyone—then she’ll help you clean up the mess.

- She doesn’t care if you don’t wash or dress yourself; coming from prison, she’s used to such things. If you want to but can’t, she’ll help. But if you don’t want to because it’s your favorite hoodie, she won’t push.

- When it comes to eating, though, she’s more insistent. She eats a lot, and Vander raised her with the idea that eating well is necessary to feel well. She’ll negotiate to get you to eat something—at least three times a day.

- It doesn’t matter if it’s a small amount, not very nutritious, or not a complete meal. You need energy.

- If you crave something specific, she’ll buy it—or steal it, depending on the cost—but she’ll make sure you get it.

Caitlyn:

- She’ll set up the guest room for you so you can stay at her place while still having complete independence.

- With her job keeping her busy, she can’t take full days off to be with you, so she instructs the house staff to have your meals ready at specific times, change your sheets, and clean your room to ensure you’re as comfortable as possible.

- To make up for her absence, she brings you pastries, slices of cake, or anything else she thinks you might enjoy.

- If she notices you’re not eating, she’ll simply sit with you and talk about how you need to eat at least a little, asking about your preferences so she can make sure you get the meals you want.

- In the evening, she’ll take a bath with you, washing your hair and massaging your back—both to make you feel better and to ensure you go to bed completely comfortable.

Mel:

- She struggles to notice something’s wrong until it’s too late or you tell her outright.

- Her work consumes so much of her time and energy that when she’s with you, she doesn’t immediately pick up on any issues.

- Her priority is keeping you in the light, which is why she moves you into her room with large windows to let the sunlight work its magic.

- In the mornings, she’ll prepare a coffee, a pastry from the best bakery, and a glass of water with an effervescent vitamin C tablet for you.

- Being a woman of science, she believes in medication, but if you’re not ready to seek professional help, she’ll at least ensure you take vitamins so your body doesn’t suffer as much as your mind.

- The deal is that you can do what you want during the day, but someone will bring you meals (and you’ll need to eat at least half), and all hygiene routines are moved to the evening so you can do them together with her help.

- Bath, shower, teeth, skincare, hair—you do everything together while chatting (as staff change the sheets and tidy the bed so you don’t feel burdened).

- She’ll try to skip the least important meetings to have meals or at least coffee with you, making sure you’re not left alone too much.

- At least three times a week, she gives you small errands to run, knowing that getting outside, walking, and fresh air will do you good.

Sevika:

- It might not seem like it, but despite her gruff exterior, she has a very soft heart. Surrounded by people with problems, she quickly notices when something’s wrong.

- She won’t bring it up first; instead, she’ll ask how you’re feeling, and if you hint that something’s off, her response is, “Do you want to talk about it?”

- If you break down while talking, she’ll hold you close, not interrupting or offering opinions. She just listens, lets you vent, and gives you something to wipe your tears. It’s not coldness—she simply wants you to process the pain at your own pace.

- She’ll mention it to Silco, at least to arrange more regular or reduced hours, ensuring you’re not left alone for too long.

- When she returns from a mission, she always tries to bring you something nice or that reminds her of you—a vulnerable gesture she wouldn’t usually make so lightly but does willingly when you need it.

- She’s unbothered by smells; if you don’t wash, she won’t push you. She just wants you to feel okay. At least once a week, if you can’t manage it, she’ll wash you herself to lighten your load, turning the moment into an act of care.

- If she has to leave at night, she’ll tuck you in, whisper that she’s heading out, and leave a glass of clean, fresh water and a sweet treat on your nightstand to reassure you that she didn’t want to leave but had no choice.

#jayce x reader#viktor x reader#ekko x reader#silco x reader#vander x reader#jinx x reader#vi x reader#caitlyn x reader#sevika x reader#mel x reader#jayce talis#viktor arcane#ekko arcane#silco arcane#arcane vander#jinx#vi arcane#caitlyn kiramman#mel medarda#sevika#arcane x reader#arcane headcanon#arcane 2#arcane writing#arcane caitlyn#caitlyn arcane#mel arcane#jinx arcane#arcane jinx#arcane silco

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Fangs of Fortune (Bai Ze Ling): perfect on pure aesthetics alone, but also it will tear your heart out while being very gay.

I was lured in to this show by Tumblr gifsets and friends on Bluesky talking about how queer and poly this show is. I'm old and I've been in fandom more than half my life. I know how to read queer subtext. I'm also pretty well versed in cdramas, so again, I know how to read subtext. So I went into this ready to, well, read the subtext.

But no this show is just puts the queer it right there in the text. The vague information we have about Chinese censorship repeatedly left me asking, 'wait how are they getting away with this?' Like some of these jokes and implications are just so blatant it seems incredible this show ever made it to being broadcast. It just feels very much like queer media made for queer people even if t's more subtle than something western like Queer as Folk.

Even without the heavy coloring of gay this show is incredible and so much more than I expected from the title and the promo. The premise is essentially the death of the goddess, who governed relations between humans and demons, leads to an influx of demons in the human world. This brings together the goddess's disciple, Wen Xiao--seeking to restore the goddess's power. WX's childhood sweetheart, Zhuo Yichen--seeking to restore the demon-hunting bureau after the powerful demon Zhu Yan killed his father and brother. It opens on Zhu Yan, in human disguise as as Zhao Yuanzhou, volunteering to help the imperial court restore the demon-hunting bureau to quell the chaos. They are joined by Pei Sijing, a retired female general from the rival demon hunting sect, and a very young doctor (and comic relief) named Bai Jiu. It starts off as a sort of monster-of-the-week with a grim Scooby gang doing detective work and fighting monsters. Each major demon has a mini arc that relates to the larger case (restoring the power of the goddess to balance the realms), and they are repeatedly blocked by either the demons or the rival demon hunting sect. Each mini arc also acts as a mirror or parallel story to slowly revealed backstory of all the main characters as well. In true cdrama fashion it's a mix of adventure, intense emotional drama, romance, and comedy. And queer and poly jokes and romance. It also has a kind of manga vibe in the way the comedy is woven into the more serious story, and in the fantastical depiction of the characters and how the story unfolds.

It is also just insanely beautiful. Every single shot is lovely. The costumes, make up, and hair are incredible. The casting director made all the major demons inhumanly beautiful. The sets are spectacular. The effects are nicely done. Every bit of has the vague surreality of a fairytale. The perfection of each shot ads to the manga vibe, as if we're seeing each critical storytelling panel come alive. There's recurring water-based special effects that are just gorgeous. Based on aesthetics alone this show would be worth watching to me. That it is combined with a complex, very emotional story is a spectacular gift to the watcher. A lot of the negative reviews of this complain about the staginess or that it's overly contrived in how each scene is shot. But I think it's gorgeous, works perfectly with the storytelling, and if we criticize art on whether it achieves the goal it intended then this show is doing exactly and perfectly what it means to do and doing it beautifully.

Additionally the acting is also very good, but Neo Hou is the stand out for sure. I enjoyed him in Back from the Brink, especially the later part of the story, but in Fangs of Fortune he's transformed, utterly embodying the role, the way Dylan Wang is Dongfang Qingcang in Love Between Fairy and Devil. Neo Hou has the right look, a slightly uncanny beauty perfect for a gorgeous immortal not of this world. The show does incredible things with his styling between the various looks and personas the role requires. But in acting he somehow manages to utterly transform his face and demeanor to manifest each aspect of the character as story demands changes from him.

There is a lot of crying in this drama. Like early on I joked that there was going to be a character crying a single perfect tear in every ep. Lol nope. Multiple single perfect tears per ep and many outright full on sobbing scenes. This show is just waiting to rip your heart out and you see it right from the beginning. But it was such sweet pain all the way through. Just a truly engaging and utterly wrenching set of intertwined stories.

My only criticism is that the pacing falls apart in the last 3 episodes. But overall the story is solid through the end, though like so many cdramas, it's saved by the epilogue.

You should absolutely watch it if you want the chaotic bi polycule (it's her, her girlfriend, her boyfriend, her boyfriend's boyfriend who is also her boyfriend, their two idiot sons, and her boyfriend's ex-who is also eventually sort of his boyfriend again), or if you want your heart torn out and stomped on. Or even if you just like really gorgeous cinematic things. Also if you watch, please don't skip the ending credits, as they change as the arcs change, and the radiant joy Tian Jiarui has as he dances is an excellent antidote to the emotions of each episode.

#Fangs of Fortune#大梦归离#Bai Ze Ling#cdrama#Hou Minghao#Neo Hou#侯明昊#Zhao Yuanzhou#Chen Duling#Wen Xiao#Tian Jia Rui#Zhuo Yichen#Cheng Xiao#Pei Sijing#Lin Ziye#Bai Jiu#Yan An#Li Lun#ab-HMH-mine#ab-reviews#it's really the xianxia polycule of dreams#which I didn't know to hope for until this show spoonfed it to me

250 notes

·

View notes

Text

I've described myself in the past as "overly-queerbaited" as a way of explaining why it took me so long to come around to Byler endgame as a legitimate possibility... but that's kind of a misleading way of putting it.

Truth is, I've always been too much of a cynical fuck to fall for queerbait... or any other story that promises positive queer rep.

[Sherlock couldn't touch me; I saw this cringe homophobia coming from a mile away. Fans mistaking straight anxiety jokes for meaningful gay subtext was clearly doomed to end in mockery. Nobody deserved to be treated like that... but god, it was easy to predict.]

I think it's a symptom of having grown up under Section 28 -- feeling like I'm being unreasonable for wanting to see queerness normalized is such an ingrained habit that even today I instinctively recoil like a vampire touching sunlight whenever an optimistic queer story falls unrequested into my lap.

But I'm hardly alone in feeling this way -- many queer Millennial and Gen-X fans of Stranger Things are against the idea of Byler because it would ruin the catharsis of watching the gay boy growing up in the same era as we did slowly succumb to the same despair that we did.

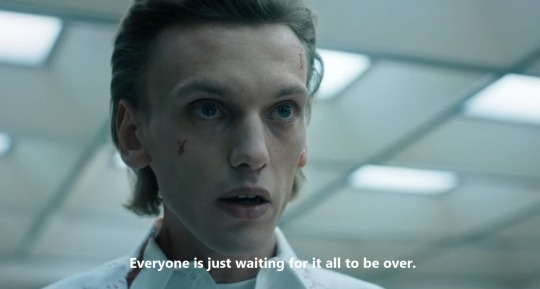

[For those who haven't played the VR game: Vecna is speaking in this screenshot.]

There's genuine comfort to be found in painful stories -- this type of catharsis is practically the cornerstone of horror as a genre -- so I can't really fault myself or anyone else for wanting it, despite the obnoxious oversaturation of disappointing queer endings in media.

This is the nostalgia show, after all -- and like it or not, for many middle-aged queers in the target audience, nostalgia is shot through with the pain of homophobia and loneliness.

But do you know who else is a hurt queer(-coded) adult who resents happy endings? This cynical fuck:

Henry personifies despair and loneliness and the dark urge to take our pain out on others -- and when Will is in the picture, I would argue that he also represents internalized homophobia.

Will might represent who we were -- but Henry represents who we've let ourselves turn into.

And I don't think many of us want to admit to that, because that would involve questioning why we have so much in common with the literal villain of the show; why we're still so consumed with self-pity after 20+ years that we're obsessing over the fate of some kid.

I'm not suggesting that wanting a less-than-fairytale ending for a fictional gay boy is equivalent to being a child killer lol. It's perfectly valid to want to see your pain acknowledged, and stories which appeal to that desire deserve to exist.

But between Henry's connection to Will and the cycle of abuse themes of the show, it's clear that this particular story simply isn't about wallowing in the bleakness of growing up gay in the 80s, but about self-actualizing in spite of it all.

So I just can't bring myself to want a "relatable" ending for Will.

As much as I struggle to enjoy positive queer rep, I don't want to be so cynical. I'd thrown up so many walls to protect myself as a teenager that I forgot how desperately I wanted to see just one of those painful queer stories end on the same uplifting note that straight stories were always entitled to: with true love overcoming the odds, saving the day, and living happily ever after.

[But I'm A Cheerleader, a surprisingly fun movie about conversion therapy, is proof that stories like this did exist when I was a teen... but finding them in the pre- and early-internet days amidst so much censorship was a tall order.]

What makes Stranger Things different from most queer stories -- and what allowed it to pierce through my defenses and stab me in the gut -- is that it perfectly mimics those bleak, acceptable-to-the-censors stories from my youth -- only this time, the secret uplifting gay plot twist is real.

Not for the sake of shock value or of grabbing some empty woke points at the last second, but because the plan all along was to slap the audience in the face for believing homophobic lies about the existence of queer happiness.

That's some gourmet catharsis, if you ask me.

Just the possibility that my inner child might finally be vindicated has allowed me to truly let myself want the things I want for the first time in 20 years -- and that's the first step towards finally crawling back out into the sunlight.

Happy Pride Month, everyone. 🌈

337 notes

·

View notes

Text

There's been some discourse going around that tries to connect Neil Gaiman writing about problematic things and him being awful to mean that everyone who writes that kind of thing is also awful or should be placed under suspicion.

Correlation is not causation. You could just as easily blame the fact that he wrote about mythology and fairytales. It has the same amount of weight as blaming dark subjects.

The truth is, there have been tens of thousands if not hundreds of thousands of authors who write/have written about dark/problematic/complicated subjects who have never hurt a soul and who never will.

Now, you could say people who have endured trauma and abuse are more likely to write about dark subjects. I'm not positive but I think this bears out in statistics. But again, the vast majority of people who have suffered abuse and whose past abuse informs their writing do NOT go on to perpetuate that cycle of violence.

I know we all wish that predators were easy to spot. But if they were, they wouldn't be predators. They'd be criminals operating in broad daylight.

The disturbing fact is that truly bad people who operate for a long time are incredibly hard to spot. They survive by manipulating those around them into providing cover for them and carefully craft personas to make it difficult to accuse them of wrongdoing. They will also use fame and money as a shield and choose victims with the least ability to fight back.

Using what happened in your crusade against dark topics and your push for censorship in fiction is incredibly disrespectful to the victims and risks making writers part of a witch hunt.

It also makes it harder to spot actual predators because it perpetuates the idea that these people have easy tells. They do not. That's what makes them monsters.

In retrospect, can we pick out certain themes in his work that aligns with the allegations against him and hints at who he really was? Yes, but hindsight is 20/20. Someone else could have written about the same subjects and been a saint of a human being.

#neil gaiman allegations#neil gaiman#tw sex assault#fandom commentary#fandom discourse#anti censorship

65 notes

·

View notes

Text

My Favorite New Manga and Graphic Novels I Read in 2023

It's time to take a look at the comics and manga I read this year! I read a whopping 78 manga and graphic novels in all. Here's a link to my Goodreads year in books (the manga is at the beginning, the novels start with Siren Queen) and my storygraph wrap up.

I also read 36 novels! If you want to see my favorites, check out my reviews here!

And finally, I've got the continuing manga series I've enjoyed this year here, so check that post out too!

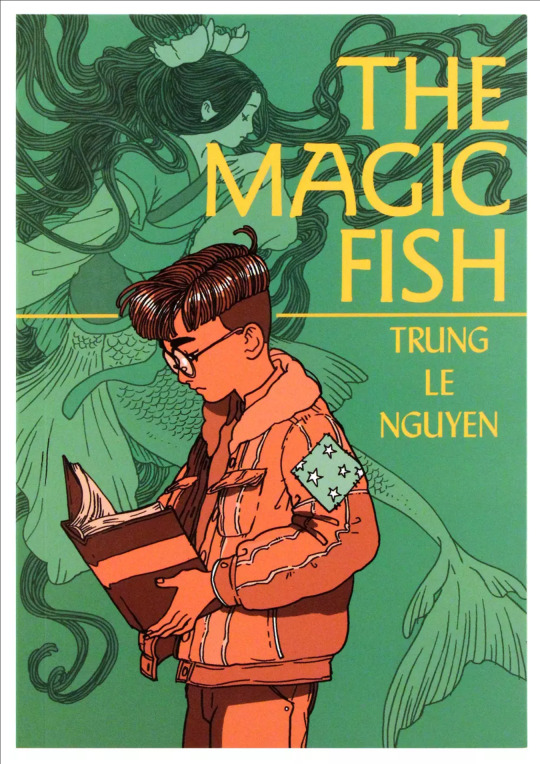

The Magic Fish by Trung Le Nguyen

This is a tale about a first-generation Vietnamese-American boy struggling with coming out to his mother. He connects with his mother through fairytales-- she uses them to express her journey as an immigrant, and he uses them to explore his queerness and identity as a Vietnamese kid growing up in America. It's an absolutely gorgeous book full of Trung Le Nguyen's signature stunning art. The fantastical, ethereal fairy tales are weaved beautifully into the lives of the characters. The book explores how fairy tales can form connection, can express culture, can tap deeply into something real and true, and can offer tragedy and catharsis. The protagonist uses fairy tales to write his own story, and the ending is lovely and moving.

Exit Stage Left: The Snagglepuss Chronicles by Mark Russell and Mike Feehan

You may know Mark Russell from his darker, socially aware re-imagining of the Flintstones, which made quite a splash on Tumblr with this post. Well, I had pleasure of meeting him at a local convention, and I finally got his comic re-imagining of Snagglepuss, also of Hanna-Barbera. He re-imagines the titular pink puma as a closeted gay playwright in the 50's dealing with McCarthyism. It's as wild as it sounds,but also really digs into the politics of the time, the struggle of standing against oppression and how art fights through suppression and censorship. It's tragic, hopeful, poignant and full of historical references. I enjoyed it ! Definitely be cautious if you're deeply disturbed by homophobia and suicide.

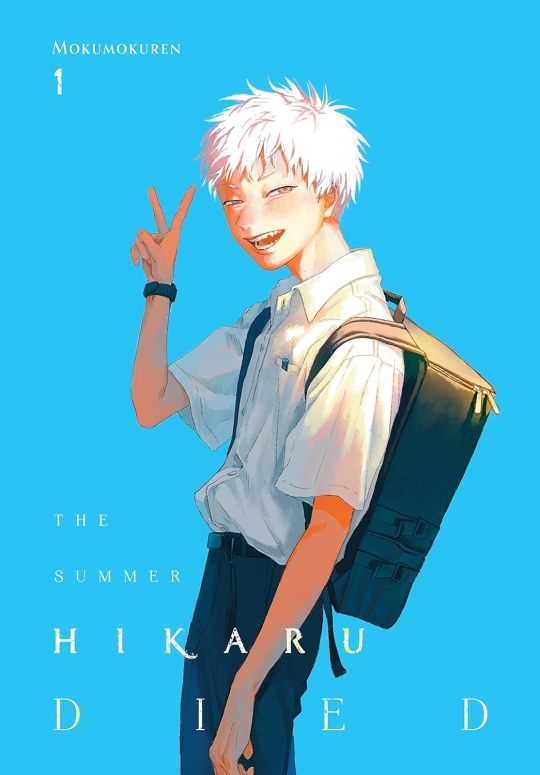

The Summer Hikaru Died by Mokumokuren

A story about a teenage boy, Yoshiki, who realizes that his best friend and crush Hikaru has died and been replaced by a strange eldritch being who is imitating him. But, missing his loved one and desperate to cling to any piece of him, Yoshiki decides to keep on having a relationship with this mysterious entity. This book's horror is visceral and sublime, especially the bizarre, creepy, beautiful body horror involving the being who replaced Hikaru. It's an exploration of anxieties involving grief, relationships, and sexuality that hits just right, and the atmosphere layered with dread is top notch. I love me some messed up relationships and unknowable queer monsters, and this book delivers.

Chainsaw Man, Look Back and Goodbye Eri by Tatsuki Fujimoto

Chainsaw Man needs no introduction, but I did end up really enjoying the story of the doggy-devil boy hunting other devils. It got so tragic and intense at the end, with lots of great surreal horror imagery and darkly funny moments. I'm impressed it went so hard, though the random powers that kept piling up made what was happening hard to follow at times, especially in fights. I'm also enjoying the current weird arc starring a class-A disaster girl and the demon sharing her body.

Look Back

I really do enjoy how Fuijimoto writes messy pre-teen/teenage girls. They ring so true. The manga follows the fraught friendship between two girls as they create manga, exploring the struggle of art mixing with real relationships, and how someone keeps creating after tragedy. It's a little hard to follow at times (especially since I have to differentiate the leads based on hairstyle), but it's a good read.

Goodbye Eri

Probably my least favorite of the three, but it's a fun read- a weird ride that examines the thin line between fiction and reality in art and makes good use of Fujimoto's cinephile background and signature gaslight gatekeep girlboss characters.

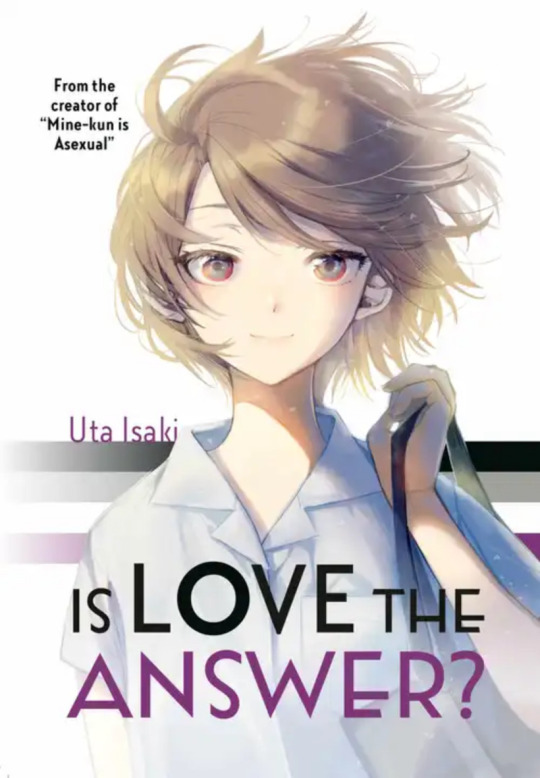

Is Love the Answer? by Uta Isaki

The story follows a teenage girl, Chika, who has always struggled with not being attracted to anyone. When Chika enters college, she meets queer people all across the spectrum of asexuality, and starts exploring her own identity. As an ace, this is the best story about asexuality that I've read. It was a nuanced look at asexuality and queerness and all the variations. Chika's journey and how she found her community was moving and poignant. It's a honest, moving look at relationships and identity, and how complicated and hard to define both of those things can be. I loved the moments of Chika imagining herself as an alien to explore and cope, and how she bonded with people through magical girl shows and other geekery. My favorite new manga of the year, it really connected with me!

The Girl that Can’t Get a Girlfriend by Mieri Hiranishi

Oh girl, I've been there. This is a fun autobiographical comic about a butch4butch lesbian's struggles finding a partner in a word that favors butch/femme, and it's just an honest look at the messiness of loneliness and relationships. I also appreciate that crushing on Haruka in Sailor Moon and becoming a HaruMichi stan was the beginning the author's queer awakening because uh...same! She has taste, and is truly relatable.

Qualia the Purple: The Complete Manga Collection by Hisamitsu Ueo and Shirou Tsunashima

See my review of the light novel here for my general thoughts on the story, since it's adapted pretty faithfully. I do think the manga is overall the best experience though, because the illustrations break up the detailed explanations of quantum mechanics a bit, and it includes a bit of extra content that fleshes things out, especially withthe ending.

The Single Life: 60 year old lesbian who is single and living alone by Akiko Morishima

Just like it says on the tin, this focuses on a 60-year-old single lesbian. And definitely the shortest thing on here, since only one 30 page chapter is out. It's a grounded story about a woman looking back on her journey to finding her identity, touching on sexism in the workplace and other challenges. It paints a portrait of a proudly gay elder who's still perfectly content being single and feels fulfilled by the life she had rather than regretting past relationships. I definitely want to see more.

Daemons of the Shadow Realm by Hiromu Arakawa

Arakawa's latest, the story is about a boy who lives in a small village with his little sister is imprisoned and has to carry out a mysterious duty...but then the village is attacked, supernatural daemons awaken, and everything he knows might be wrong. I'm enjoying this fun romp so far! It delivers an really nice plot twist right out the gate (and an excellent subversion of the usual shonen "must-protect-my-saintly-sister" narratives). It boasts Arakawa's usual fun cast and interesting world (and cool ladies). There's some slight tone and pacing issues in the first part- there's so much time spent explaining mechanics the lead doesn't really get to react to his life turning upside down. But it starts smoothing out by the second volume. I'm excited to see what's next!

Superman: Space Age by Mark Russell and Michael Allred

This is a retelling of Superman set throughout the late fifties to early eighties that has Superman interact with the political and social upheaval of the time and question his own role in things. It explored the Superman mythos through a lot of cool new angles, and has a good Lois (why yes she would break Watergate) which is how I always measure a Superman adaptation. My one complaint is, while I liked some of the things it did with Batman, the ending with the Joker was pretty weak. The ending of the overall comic will also be bizarre for anyone not uses to how weird comics can get, but I think I dug it.

#DRCL by Shin'ichi Sakamoto

A manga retelling of Dracula that focuses on Mina as the protagonist and imagines the characters at an English prep school. It adds a lot of diversity to the characters and has exquisite, evocative art. I'm curious where it will go and what it intends to do with all it's changes (especially Lucy), because right now it's mostly vibes and creepiness and the direction isn't clear.

#year in comics#manga#yuri#the summer hikaru died#the magic fish#chainsaw man#superman#daemons of the shadow realm#drcl midnight children#is love the answer?#superman: space age#goodbye eri#snagglepuss#my reviews#drcl#the girl who can't get a girlfriend#the single life#trung le nguyen#qualia the purple#tatsuki fujimoto#hiromu arakawa

152 notes

·

View notes

Text

A reminder about French literary fairytales - those of the late 17th to late 18th century. Perrault, and d’Aulnoy, and the rest.

Something that might be omitted when talking about these tales, because it isn’t well-known outside of France apparently, while in France it is so obvious we don’t tend to mention it: these fairytales were written in a time when literary censorship was in full effect.

There were things that could not be written or published during this era of the monarchy ; and the king’s men kept an eye on the world of books, novels, poems and theater ; and one could be sent to prison if their texts ever reached the wrong ears or the wrong eyes.

Just a little historical context reminder.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

simeonvanderhoeven

Yesterday, one of my posts got flagged within minutes of uploading it. It hurts my heart every time to have something that you pour your soul in be restricted and censored without further notice. Although I have had positive experiences with posts being restored after asking for a review, it doesn’t take away the damage it does in terms of reach, engagement and reaching your audience. • Creating art is not a fairytale. It asks for constant dedication finding inspiration inside (doing the hard work and digging deep into your own being - instead of copy-catting someone else), travelling around and planning to make things work and execute your visions, carefully post-processing it until it carries the exact message you wish to convey, and delivering it to the world. Not to mention the financial resources needed, the time and the constant drive you need to keep the creative spirit alive in this world. • Yes, it also is a beautiful journey. A journey that teaches you to keep going, pick yourself up, and take a step back when it is time to do so. A journey that brings you to beautiful places and connects you with beautiful people. But since my art was always aimed at inspiring the larger collective, the last step of the artistic process seems to be missing. • I found solace in exhibiting my work in real life. It is freeing to be able to showcase whatever YOU want and believe in, and to have people view it without restrictions. To truly be able to reach people’s hearts, and to touch them. To offer creative solace to those that seek and need it at that current time. But doing these exhibitions requires even more time, energy, logistics and financial investments.

The world is in a creative and spiritual crisis. Never before, there was so much creativity around, but at the same time, there never was this much censorship. At times it feels like creativity is winning the battle, at other time it seems to take a big hit again. I just can’t wrap my head around a large part of the world wanting to censor the vulnerable and spiritual connection of human bodies to nature and creation. Having these permanent bans on my profile really made me question my place here on Instagram and if all of this still makes sense. Having to monitor every word I use, every image I share, and every pixel I blur is tiring and kills the creative spirit. I know I have not chosen the easy way, and it is my choice to keep walking a path that is authentic to me. But walking it asks courage, resilience and determination. I am currently digesting how I feel about all this and taking the opportunity to express these thoughts and feelings through my art, which has put me on this path in the very first place. Grateful for all of you that have supported me over the years ro have just discovered my work. Thank you ❤️ In frame: @icelandicselkie

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

As a long time fan of minecraft I present

Ways I would change to minecraft movie if I directed it

(Qualifications: The cake is a lie)

1. You cannot convince me 2d animation wouldn't improve the movie. Shaders could provide some great visual inspiration to make it feel more cinematic. Seriously, minecraft has great models for building complex beautiful environments

2. Hire some of those minecraft short makers. Seriously

3. Nonverbal steve. Nonverbal steve. Add some good old minecraft body language. Other characters can talk, though forming a friendship with a nonverbal alex could be great. Villager type characters that talk but then our two non verbal besties exploring the world and living together

4. Bring back the credits being, maybe even let them function as a subtle guide. Make it a movie about the joy in creation and exploration and the natural world. A minecraft movie should be about the inherent creativity and desire to do that humans contain.

5. Lots of fandom easter eggs. Including older and mod/server references.

6. Excessive quantities of chickens. No explanation needed

7. Some definite horror vibes. This is minecraft afterall

8. Amnesia isekai

9. As alex/steve grow up the world grows with them through there continuous efforts to improve the place, adding walls/lamps/flowers, digging out and transforming the area around houses, curing zombie villagers. Their house following the wooden shed to the cottage to the most intricate fairytale building you've seen in your life pipeline, ideally integrated into the village. Maybe connected by a cobble stone path decorated with wildflowers?

10. I just need the movie to end with the two of them sitting next to each other on a wooden pier, almost holding hands, legs kicking, as they silently stare at the sun setting into the ocean, at peace after having rebuilt their lives, the fruits of their labor behind them in the background, with soft ambient music playing

11. And then the movie credits need to come in the style of the original game credits except they end on parrots dancing to a jukebox and they have images of some of the most iconic minecraft builds. Like the international anti censorship library or dan tdm's old lab, a creeper birthday cake, just a little treasure trove of the ways minecraft has impacted peoples' lives

12. And the most important. Never confirm who they were or how they got there. Steve gives me florist vibes and Alex reminds me of Leah, but that's not super important. Give hints to their past life, how they ended up there, but let the audience fill in the blanks, make them have to watch to learn the quirks of the cast, to pick up those hints, let the offspring of game theory loose their minds

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

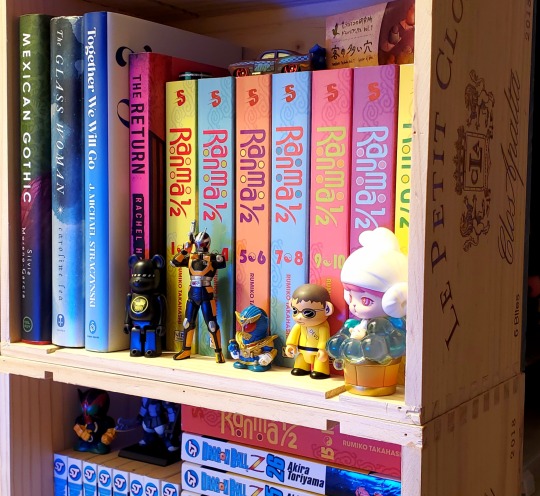

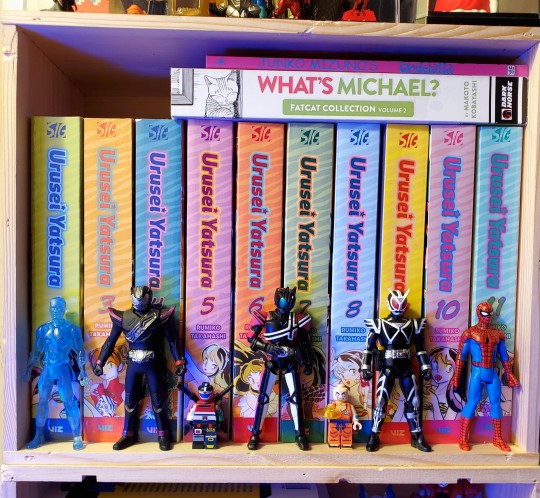

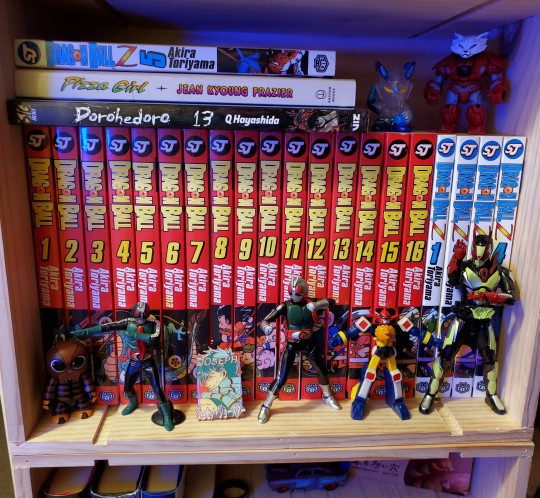

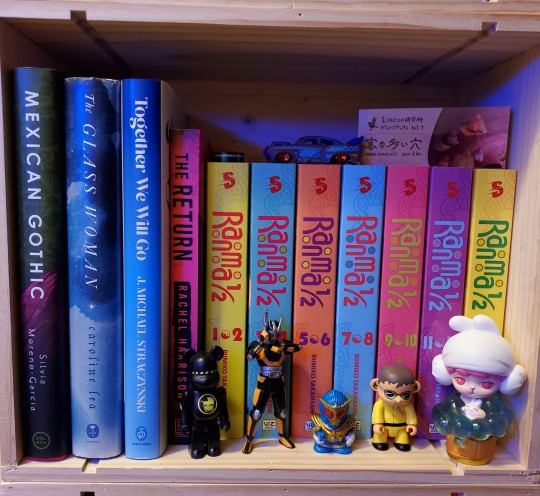

Finally got around to cleaning and rearranging the bordeaux crate shelves. A mix of books and tchotchkes from both of us.

This originally started as an overflow shelf, but now we use it for a colorful room divider.

A wildly eclectic mix of stuff here. Most of it waiting for a bigger space to transfer over.

Of note - a full run of one of the many horrible US print releases of Dragon Ball.

A masterpiece of fairytale action and comedy adventure - but almost every US release is majorly flawed. This version has name changes, poorly rewritten dialogue, inconsistent censorship, and horrendous print quality.

I'm lucky to have a full Japanese run in the other room - some of which are first printings.

[And here's the Instagram link for this post - but keep in mind it's on my personal account this time - so there's not as much fun stuff on there]

#manga#books#book collection#manga collection#shelfie#ranma#dorohedoro#ドロヘドロ#らんま½#dragon ball#ドラゴンボール#urusei yatsura#lum#うる星やつら#physical media#toy collection#toy collector#minifigures#kamen rider#仮面ライダー#action figures#action figure photography#book lover#manga lover#comics#rumiko takahashi#pop mart#qee collection#spider-man#garfield

76 notes

·

View notes

Text

Deathless Thoughts:

I only read this book in full once in 2017 and have only really paged through it a lot since. I definitely found it much more deliberate and thematically coherent this time around. I remember initially feeling like the surrealism and constant jumps ahead were disjointed but it reads very cohesively to me now. I’m very curious if that will continue past the latter 50% which I haven’t reread yet. I remember starkly disliking that portion and I have no idea if I’ll feel similarly this time around— because I already enjoyed the second act much more on reread and acknowledged its purpose, when up until now I did not lol

My initial thoughts were that the fantasy elements were too surreal to care about and that the relationship was too much of a nothing, with too little not unpleasant screen time to justify its centrality to the plot. But having read more classic surrealist Russian lit has familiarized me to the former and makes me actually understand what it’s going for. And for the latter I think I’m just more onboard with unpleasantness and abuse being the point. So currently, my perspective is almost wholly positive.

I enjoy the book’s use of its subject material— fairytales set in actual history— as many many metaphors. First folktales and fantasy specifically in the Soviet era, so rife with censorship, as a vehicle for allegory, their use and importance in literature itself being a motif. Then the metaphor for inexorable class hierarchies and unchangeable power structures before and after the revolution, the way only the branding changed, but the power structures remained. And also, most pervasively, as a way to examine gender roles and gendered loss of agency; the politics of a marriage.

I really liked the way the novel built up Koschei and how everything is about Marya’s relationship with Koschei (her relationship with agency and the lack thereof) even when he’s fairly infrequently on screen. From her sister’s bird husbands in the opening, and child Marya’s musing on the potential transformative nature of marriage— but also the inherently unequal power dynamic and resolving that she will do/be better because she knows more than they did. To the metaphor of her thinking that a secret will treat her well and then later the line where the personified secret is then likened to a husband who will be her ruin. Even that when Koschei finally shows up to take her away it’s compared to being taken away by the revolutionary government/the police.

Marya is herself highlighted for her knowledge and her desire for it. Specifically the ability to see discrepancies in the stories she is told whether that is the magical or ideological and political. The sisters in the opening marry into seemingly static unmoving snapshots of history. Meanwhile Marya’s singled out in her precociousness and open admittance of there being anything completely beyond the ideologies presented by each suitor in his human form [the power structure of the Tsarist state, and the Soviet Union]. She’s defined by wanting to see beyond dichotomies and limited scopes of propaganda. She sees it as a skill, and it is, but it’s also something that singles her out for misery, both by her peers (the scarf incident) and by the likes of Koschei who is specifically drawn to willfulness and a lack of adherence to a particular role with the intent of breaking that will.

The entire seduction segment that is turning all the food and her illness into an erotic power exchange is also just explicitly about breaking her will, and fostering perfect obedience and dependence on him. It’s also really interesting that, in going with him, she does somewhat lucidly give up and trade away her agency/ability to dictate a story/her own perspective in exchange for being physically well cared for. (But then even that is very thorny and with many strings attached)

So by part two, she is stuck in the dichotomy of “who is to rule” and either she can be a Yelena/Vasalisa or a soon-to-be Baba Yaga. Yet, either way, she is never good enough and it is still inevitably an exploitative and draining situation.

Marya being successful in her willingness to do degrading and cruel things to earn Baba Yaga’s blessing and Koschei’s favor being punctuated by all her friends— who without which she would never have succeeded at all— dying horribly illustrates that so well. In her success she is only further isolated. She will never repay their help, because being Tsaritsa of Buyan, and having any sort of power, is inherently antithetical to that.

The emphasis on Lebedeva’s girlboss magic makeup and the passage about Marya being told that girls must care only for vapid, pretty things, among other moments, might feel extremely dated. But I do think they’re intended to be employed in a way where traditional femininity presents a sort of deliberate and acknowledged safety? And it goes hand in hand with Marya, while never choosing to be a “Yelena” in traditional soft femininity, does end up choosing to try to leverage soft power and soft manipulation within deliberately gendered terms fairly often. But again it’s just presented from a very dated and particular context.

So far, the sheer dedication of the book to being an explicit Bluebeard tale and a story about abuse, and how there is no winning in that sort of relationship has been very fun for me.

I also enjoyed Koschei outright lying about the Yelenas and Vasalisas— and then later about the location of his death. I think that’s a character type you usually expect to deceive via omission but, no, he just outright lies a lot.

Another example is that Widow Likho’s book makes it clear that humans best enter into Buyan when ill, and meanwhile everything Koschei does is of course explicitly a repetition of previous stories. So it’s practically confirmed that he had taken every Yelena etc on that same long trip and made them ill on purpose. Even though in the moment he claims to be surprised by it, and spontaneous in caring for her through her illness.

Or the suggestion that he found a reason to put all the other girls in the stable when they got to Buyan as punishment for disobeying him. That the point is the punishment and breaking of the will rather than there being any sort of standard the bride could realistically meet where he would be happy with her and welcome her to her new home without that initial humiliation and fear.

It’s also incredibly funny and refreshing that this book buys into Koschei’s nonsense way less than any of its subsequent imitators. (The Grisha trilogy included!) I enjoyed Baba Yaga being like “Why is everything black, stop being dramatic 🙄”

He’s barely present in the book at all. His page count is truly negligible! And it’s great!

Like I mention earlier, that was actually something I was annoyed by on my first read, the relationship just seemed fairly thin, even though the snapshots of it that we get are fascinating. But after being inundated with so many books worshipping the ground love interests like him stand on, I love how much he doesn’t fucking matter and how little page time he has. How that itself allows Marya’s emotions and conflicted feelings to remain central. The narrative doesn’t care about him, it’s only what impact he has on her that’s relevant.

Anyway somewhat superficial but I really enjoy the goth love interest being the Tsar of Life, because authors typically go a more obvious and melodramatic route. Despite all of the goth mystique, him not being associated with death, darkness, night, etc was refreshing. But also I do generally just find the concept of life being equated with the lurid and demanding, the parasitical, something that is always in a personal sense at war with death— aka the mention of him always looking sickly or feeling skeletal initially when he kisses Marya— a compelling one. It’s death and the maiden wrapped up in a single person essentially.

Anyway I also appreciated the parallel of the Yelenas being trapped in eternity weaving soldiers while Marya’s first thought upon seeing Koschei is that if she had knitted herself a perfect lover he would look like that. There is the constant underpinning of Marya being wholly separate from them, the question of whether she is greater or more horrible than them, but at the heart of it she’s really not. She’s just another victim in a long string of them.

#cautiously hopeful that I’ll like the second half just as much despite my opinions on first read#deathless#koschei the deathless#marya morevna#book talk#*writer’s cap*#dark stories of the north

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

Since Arz has been posting about her OC's, why dont I show one of mine!

"Need to know your way through the library? Just ask our lovely librarian assistant, Linda! She knows this building like the back of her hand(especially because its her favourite place in town!)."

(sorry if this looks rushed, I'm not that good at drawing)

In the show:

She was a background-turned-side character that would appear in a few episodes, acting as a guide for the Handeemen if they need to find a specific book.

They even have their own segment called 'Linda's storytime', where she reads popular fairytales(with the Handeemen interupting them from time to time as a li'l gag). She is mostly seen around the library.

Outside of the show:

They're based off Avery(Arz's OC)'s late close friend, who used to work at the town's local Library. Avery wanted to make something to remember them by, and thus, Linda Literature was created!

Relationships with the Handeemen(Show counterparts):

- Rosco: She was at first scared of the giant pup, due to him being larger then the average golden retriever. But they slowly warmed up to him after Riley showed how harmless Rosco is.

Rosco(like how he is with everyone else) is pretty friendly with Linda, he tried to be a lap dog while she was doing her storytime segment and almost sufficated her, Don't worry, Riley managed to help them in time(Rosco also gave her a lick in the face as an apology).

- Riley: She is close friends with the scientist, as Riley is a regular visitor there. Linda would often try and make small talk with her, they find her use of scientific words 'charming'(rumor has it that she has a small crush on the scientist). Riley is one of the few people who returns the library books in a clean state, Linda appreciates this alot.

Riley sees her as a good friend, Linda is one of the few people she doesn't mind having small talk with(they're dynamic is basically the "He asked for no pickles" meme).

- Nick: Linda looks up to Nick as she is inspired by his poetry skills, they hope to one day be as good as him in writing things(she also has a small crush on him too). Although, they do wish he returns the library books with less finger paints on them.

Nick thinks of her as a great friend, he's glad to finally have someone who wilingly listens to his poems, and properly listens to them(no offense Duke, but you might need to work on your focus more).

- Daisy: The two are good friends, Linda enjoys talking to her, but she also prefers the baker to return the library books withought any flour or other baking stains that somehow got stuck in the pages(atleast she gives them freshly baked pies as an apology).

Daisy invited Linda to join her book club as they needed more members, although, its more of a gossip group really(Daisy is also the only one who knows about Linda's small crush on both Riley and Nick).