Text

Outside of her co-creation of the fairytale anthology with Ellen Datlow, Terri Windling also created "The Fairy Tale Series" gathering novels retelling fairytales, written by various fantasy authors of the time (who also often participated in the aforementioned anthology series).

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Illustration by William Heath Robinson of Thumbelina, facing page 64 of Hans Andersen's Fairy Tales, London: Constable, 1913. Now in the New York Public Library.

240 notes

·

View notes

Text

Anne Yvonne Gilbert, 'Wicked Queen', 'Snow White'', 2013

298 notes

·

View notes

Text

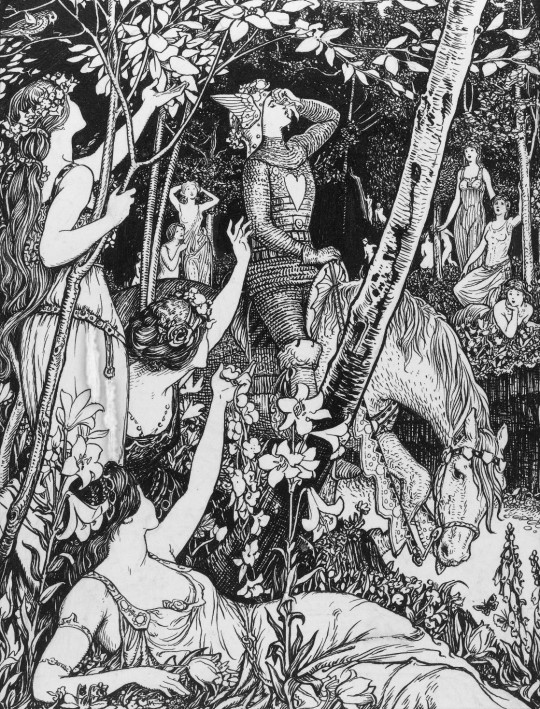

Among the flowers were lovely maidens calling to him with soft voices, from The Fairy of the Dawn for Andrew Lang's The Violet Fairy Book by Henry Justice Ford (1906)

8K notes

·

View notes

Text

Anne Yvonne Gilbert, ''Snow White'', 2013

540 notes

·

View notes

Text

Genderqueer Folktales (part 2)

I’ve gathered some new gender nonconforming folktales since making part 1, so it’s time for a new post! Again, please keep in mind these are all translations and products of their time. I will still attempt to put some modern-day labels on them to make them easier to navigate:

The Story of the Maiden-Knight Indian legend, published in 1916, based on the Mahabharata.

[Cw: being outed, threat of violence, awkward use of pronouns.]

A king prays for a son to go to battle his enemy, but the god Shiva reveals to him that he “should have a son who should first be a daughter”. Accordingly the child born to them – Shikhandi – is raised as a boy and married to a princess. When he finds out the situation the bride’s father is furious however, and wants to go to war over it. Shikhandi goes into the forest, in the hope that without him there will be no war. There he meets a kind Yakshas (nature spirit) who is willing to lend Shikhandi his manhood until he has saved his father from this threat. But when the king of the Yakshas finds out about this he decrees that the Yakshas will not get his manhood back until Shikhandi’s death.

The Stirrup Moor Albanian folktale, published in 1895.

[Cw: violence, king attempts to steal son’s wives, some uncomfortable descriptions of a black person.]

A prince, through his many adventures, wins the love of three wives: one human lady, one jinn princess, and one Earthly Beauty (a type of fae-like spirit from the underworld). The latter of the three regularly changes between her supernatural female shape and her chosen human form, that of a black man. In this male shape he is a formidable warrior and helps protect both the prince and the other wives. All four eventually live happily ever after.

The Boy-Girl and the Girl-Boy A Gond folktale from Central India, published in 1944.

[Cw: attempt at being outed, awkward use of gendered terms and pronouns, some doubt as to whether the AFAB protagonist is completely happy with the physical change.]

An AFAB child is adopted by a Raja, who accepts him as his son. Near the palace an old woman raises one of her many AMAB children as a girl and arranges a marriage for her. The young couple is very startled at finding out they have “the same parts” but there are not other repercussions. Later the young wife doesn’t dare to go bathing with the other women and meets the Raja’s adopted son, who has run away and changed himself into a bird. The bird offers to “exchange parts” and both protagonists end the story with a body matching their presented gender.

The Girl Who Became a Boy Albanian folktale, published in 1879.

[Cw: preoccupation with sexual ability, attempts to kill protagonist.]

AFAB protagonist answers the king’s call for warriors, dressed as a man. After several great deeds the young man wins a princess’s hand in marriage in another kingdom. He is liked at the court, but they feel obliged to get rid of him because he seems unable to consummate his marriage. He survives every dangerous task, however, and finally is sent to confront a snake infested church. The snakes curse him to become a boy, after which he returns to the court and all ends well.

With an affectionate mention for the 13th century French poem Yde and Olive, which was brought to my attention by @pomme-poire-peche. You can read about this brave princess-turned-knight married to a loyal princess here.

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sleeping Beauty vibes

Resting (c.1890) by Victor Gabriel Gilbert

543 notes

·

View notes

Text

How come this post gained 70 notes in just a few hours? That's more than most of my posts in two years.

You might have noticed my posts have recently been centered around a same specific... wave? Circle? I don't know how to call this exactly, and I am not an expert of it all...

But there is this wave of authors and editors, a sort of loose group focusing on retelling, rewriting and twisting fairytales and folktales for a modern, adult audience, and that had their era from the 70s to the 90s. Angela Carter, Terri Windling and Tanith Lee, and all the others that came along (Jane Yolen, Charles de Lint, Neil Gaiman, Robin McKinley, Steven Brust)...

And what is truly fascinating, at least for me, is that this is where the thing we call today the "Grimmification" seems to come from. (At least within the English-speaking world)

Today the process of "Grmmification" (as TV Tropes named it) has earned a certain reputation for being a cheap and gratuitous way of offering in a superficial way an edgy, pseudo-anti-conformism, with just a desire to oppose Disney and not true appreciation and care for the original fairytales. You know, a reputation that was gathered by big blockbusters like "Snow White and the Huntsman" or "Hansel and Gretel Witch Hunters", or by B-horror movies (the Asylum's fairytale horrors), or by massive pin-up comic publications (Grimm Fairy Tales)... Of course there's a lot of "grimmified" pieces that nuance this a lot by showing a lot of poetry, beauty and art in their harshness, trauma and gore (Pan's Labyrinth, Changeling the Lost) or by just being embraced by the Internet (Gretel and Hansel, Neverafter, The Grimm Variations). But still, you know what I am talking about. We are in an era re-embracing the romance, the humor and the epic within fairytales, a time of re-evaluating positively classic Disney movies and other childhood productions, a much more colorful, optimistic, un-edgy time compared to the boom of dark, edgy, "grimmification" of the 2000s and 2010s. Ended is the generation of McFarlane's Twisted Fairy Tales or of DeviantArt's Twisted Disney Princesses (sorry I forgot who the creator of this series was).

And so, in front of the... I'll say "soft backlash" against the Grimmification process, it is quite fascinating for me to see that the root of this unofficial movement, or the first modern manifestation of this "phenomenon" was the previously described wave/circle of authors. This women-driven wave of authors (Carter, Lee, Windling and Datlow clearly led the dance) who were the first to truly bring all of what we associate with "Grimmification" (making things darker, more violent, the tales more frightening or bloody, bringing Gothic horror or harsh realism to fairytales, sliding in more sexuality and eroticism, openly standing in opposition and rejection of Disney's pop culture version of fairytales)... But out of a movement that...

... stood up for the perpetuation of the art of fairytales ("modern fairytales")

... defended feminist principles (putting the female characters at the heart of the story, highlighting the trauma they had to go through, deconstructing harmful fairytale stereotypes and cliches for women)

... embraced the idea of fairytale as a product for adults (they were the leaders of complexifying and deepening fairytales into a true "fairytale fantasy")

... stood up with queerness (part of the eroticism and sexuality of these tales was also to include lesbianism, homosexuality and a much more open and honest look at sexuality)

... and encouraged research and exploration of the history of fairytales (exploration of Perrault's text versus Disney ; presentation of the alternate versions and uncensored versions of the Grimm's stories) and of other cultural folktales than those traditionally known (exploration of Asian, Russian, African tales...).

And all of these things, that are still thinks people are looking for today in fairytale retellings, came hand in hand with the blood and the gore, the vile and the rape, the dark and the disturbing. The "Grimmification".

I am not at all an expert on this time era or those publications, mind you - I am just beginning to dig into all this, and I speak from the point of view of a casual enjoyer and a researcher of "vintage" books and half-forgotten fictions. I am here doing broad generalizations and I might be dead wrong. But it is just the feeling I got - that the "Grimmification" process took root within these things... Somewhere in the dark psycho-sexual and folk-horror Gothic of the 70s, was the beginning of our modern "Grimmification".

#discussion#i still don't get why some of my posts become so popular#and others grow stale and moldy like an old piece of bread#heck this was just random notes written late at night before going to sleep I didn't even double check#there's typos in there

110 notes

·

View notes

Note

Until the dust settles, best to avoid mentioning multiple-rapes enjoyer Neil Gaiman who allegedly committed some of the rapes while his kid was in the room; so much so that his kid started addressing his rape victim the same way he was. You know better.

You know, I very precisely thought dropping his name in the post might have someone upset, but then I thought I would still include it, for one simple reason - it cannot be avoided.

Gaiman was part of this "wave" I am talking about, whether you want it or not. He was historically there and if you want to read Terri Windling's anthologies, you WILL have to face his name big on the covers. Yeah he was not one of the leaders, just a follower, and he was here for the last part of the wave, the 90s, but he was still part of it and a (quite famous) symbol of this specific "movement", to the point of sometimes overshadowing the others. In fact, understanding where Gaiman's own fairy retellings and approaches come from is going to read the stories and works of the authors he published with (Tanith Lee, Charles de Lint, etc). So, you know, I can't just erase the fact he was an influence back then. Heck the Gaiman of the 90s wasn't even the big successful Gaiman you know today - he was still a little comic book author just making his big break through Sandman.

You might be of the position of "Don't ever mention anybody who has done anything wrong ever" but I am on the contrary position. "Know thy enemy" or "Get how the monster lives" or "Document yourself on the disease" or however you want to call it. I like to use this comparison because we are roughly in the same case but - Marion Zimmer Bradley. She was so much worse than Gaiman (not that you can rank the worseness of these things, but you know) and yet we cannot erase the fact her "Mists of Avalon" was a BIG, big influential landmark of modern Arthuriana and "feminist" Arthuriana, whether you want it or not. And when you look back at what this book contains, how it looks today, and how it was received back then, with the stuff we know today... This is very enlightening on the socio-historical context back then, and on how the rules and limits of fiction moved. Same thing with Polanski and his Macbeth or his Rosamery's Baby. When one talks of generational influences, of waves of fiction, of the history of retellings, names have to be spoken. For those familiar with French literature, it is the Céline case.

And I think it is better to mention Gaiman's name right here in my post just in case somebody didn't know about this group of authors/editors and wanted to check them out. Better be prepared to see him appear in the books, rather than having some sort of jumpscare, don't you think? I know some people would feel betrayed or angry at not "being warned" somebody they didn't like was "in there". Well the warning's in the post, I didn't lie about the content.

#i don't usually do trigger warnings#but consider me placing gaiman's name in there a subtle one#i know some people might not enjoy the way i'm doing things here#but it is still just a Tumblr blog you know#if I want to talk about serial killers on my fairytale blog I will and I have#and also when is the “dust going to settle”? It is a question that troubles me#can there be a “time limit” to these things?#i didn't even tag his name in there to make sure it wouldn't clog the feed about the accusations#as people have repeatedly demanded

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

You might have noticed my posts have recently been centered around a same specific... wave? Circle? I don't know how to call this exactly, and I am not an expert of it all...

But there is this wave of authors and editors, a sort of loose group focusing on retelling, rewriting and twisting fairytales and folktales for a modern, adult audience, and that had their era from the 70s to the 90s. Angela Carter, Terri Windling and Tanith Lee, and all the others that came along (Jane Yolen, Charles de Lint, Neil Gaiman, Robin McKinley, Steven Brust)...

And what is truly fascinating, at least for me, is that this is where the thing we call today the "Grimmification" seems to come from. (At least within the English-speaking world)

Today the process of "Grmmification" (as TV Tropes named it) has earned a certain reputation for being a cheap and gratuitous way of offering in a superficial way an edgy, pseudo-anti-conformism, with just a desire to oppose Disney and not true appreciation and care for the original fairytales. You know, a reputation that was gathered by big blockbusters like "Snow White and the Huntsman" or "Hansel and Gretel Witch Hunters", or by B-horror movies (the Asylum's fairytale horrors), or by massive pin-up comic publications (Grimm Fairy Tales)... Of course there's a lot of "grimmified" pieces that nuance this a lot by showing a lot of poetry, beauty and art in their harshness, trauma and gore (Pan's Labyrinth, Changeling the Lost) or by just being embraced by the Internet (Gretel and Hansel, Neverafter, The Grimm Variations). But still, you know what I am talking about. We are in an era re-embracing the romance, the humor and the epic within fairytales, a time of re-evaluating positively classic Disney movies and other childhood productions, a much more colorful, optimistic, un-edgy time compared to the boom of dark, edgy, "grimmification" of the 2000s and 2010s. Ended is the generation of McFarlane's Twisted Fairy Tales or of DeviantArt's Twisted Disney Princesses (sorry I forgot who the creator of this series was).

And so, in front of the... I'll say "soft backlash" against the Grimmification process, it is quite fascinating for me to see that the root of this unofficial movement, or the first modern manifestation of this "phenomenon" was the previously described wave/circle of authors. This women-driven wave of authors (Carter, Lee, Windling and Datlow clearly led the dance) who were the first to truly bring all of what we associate with "Grimmification" (making things darker, more violent, the tales more frightening or bloody, bringing Gothic horror or harsh realism to fairytales, sliding in more sexuality and eroticism, openly standing in opposition and rejection of Disney's pop culture version of fairytales)... But out of a movement that...

... stood up for the perpetuation of the art of fairytales ("modern fairytales")

... defended feminist principles (putting the female characters at the heart of the story, highlighting the trauma they had to go through, deconstructing harmful fairytale stereotypes and cliches for women)

... embraced the idea of fairytale as a product for adults (they were the leaders of complexifying and deepening fairytales into a true "fairytale fantasy")

... stood up with queerness (part of the eroticism and sexuality of these tales was also to include lesbianism, homosexuality and a much more open and honest look at sexuality)

... and encouraged research and exploration of the history of fairytales (exploration of Perrault's text versus Disney ; presentation of the alternate versions and uncensored versions of the Grimm's stories) and of other cultural folktales than those traditionally known (exploration of Asian, Russian, African tales...).

And all of these things, that are still thinks people are looking for today in fairytale retellings, came hand in hand with the blood and the gore, the vile and the rape, the dark and the disturbing. The "Grimmification".

I am not at all an expert on this time era or those publications, mind you - I am just beginning to dig into all this, and I speak from the point of view of a casual enjoyer and a researcher of "vintage" books and half-forgotten fictions. I am here doing broad generalizations and I might be dead wrong. But it is just the feeling I got - that the "Grimmification" process took root within these things... Somewhere in the dark psycho-sexual and folk-horror Gothic of the 70s, was the beginning of our modern "Grimmification".

110 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cinderella

1876

Artist : Henry Lejeune (1820-1904)

182 notes

·

View notes

Text

Little Red Riding Hood

Artist: Isabel Oakley Naftel (British, 1832–1912)

Date Created: 1862

Medium: Watercolor and Gouache on Paper

Isabel Naftel (1832-1912) was an English painter of principally portraits and landscapes. She exhibited regularly at the Royal Academy and the New Watercolour Society. She was married to the artist Paul Jacob Naftel.

Little Red Riding Hood is a European fairy tale about a young girl and a sly wolf; it's origins can be traced back to several pre-17th century folk tales. The two best known versions were written by Charles Perrault and the Brothers Grimm. The story has been changed considerably in various retellings and subjected to numerous modern adaptations and readings.

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ann Macbeth, "Once Upon a Time" (1902)

via ninaclarebooks on instagram

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Arthur Rackham (British/English, ), illustrator for English Fairy Tales by Flora Annie Steel • 1918

”Somebody has been at my porridge, and has eaten it all up!”

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

Warwick Goble (British, 1863-1942) • Illustration for Beauty and the Beast • 1913

67 notes

·

View notes

Text

My collection of fairytale covers continue... With a little shout-out to the 90s anthology series by Terri Windling and Ellen Datlow, dedicated to "fairytales for adults" - rewrites of traditional folk tales allying "the fantasy and the horror" in an homage to the "pre-Disney" fairytales.

Volume 1: Snow White, Blood Red

Volume 2: Black Thorn, White Rose

Volume 3: Ruby Slippers, Golden Tears

Volume 4: Black Swan, White Raven

Volume 5 + 6: Silver Birch, Blood Moon + Black Heart, Ivory Bones

#fairytale retelling#terri windling#ellen datlow#dark fairytales#fairytale rewrites#fairytale anthology#series#covers

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

'Spindle, Shuttle, and Needle: The waiting maid sprang down first and Maid Maleen followed' by Arthur Rackham.

Interior illustration from 'Little Brother & Little Sister', a collection of Grimm's fairy tales illustrated by Arthur Rackham, published in 1917.

24 notes

·

View notes