#black women scholars

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

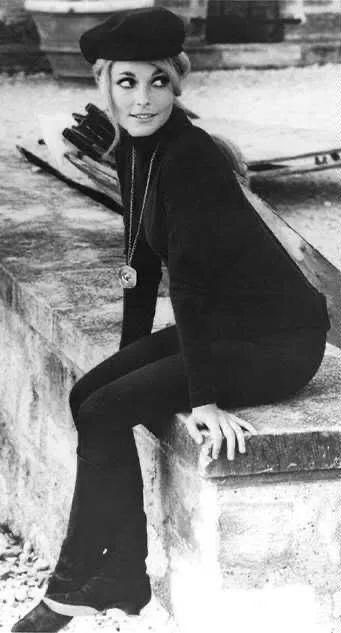

women's beatnik fashion

#beat generation#beatnik#fashion#beat poetry#women's fashion#vintage#vintage fashion#black and white#junkie scholar#60s#60s aesthetic#70s#70s aesthetic#kate moss#girlblogging

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

I did six assignments today and got an “A” on my exam. I deserve a some diamonds.

#black women#blackwomen#black women in luxury#luxuriousbw#black femininity#academia#black scholar#black students#future nurse#luxury#black women in leisure#black women fashion#black beauty

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mary Frances Berry

Civil rights activist Mary Frances Berry was born in 1938 in Nashville, Tennessee. In 1980, Berry was appointed to the US Commission on Civil Rights, and served as the Commission's chair from 1993 until 2004. She was one of the founders of the Free South Africa Movement, which helped to end apartheid in South Africa. For this work, she won the Nelson Mandela Award from the South African government in 2013. Berry is the author of twelve books and currently a professor emerita at the University of Pennsylvania.

Image source: Kennedy Space Center

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

…TV and movies advertise killing as a very easy thing—how simple to blow somebody away. If it is that easy it shouldn’t be, and I didn’t want my character to be someone who felt the need to murder somebody.

Octavia E. Butler on writing Kindred (1979), interviewed by Frances M. Beal for The Black Scholar (1986)

#black studies#octavia e. butler#speculative fiction#black sci-fi#kindred#the black scholar#black women writers

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

C’s may get degrees but they don’t keep scholarships GO FUCKING STUDY

#mrs.degree diary#high maintenance#mrs.degree educated#educated black women#education#scholars#university#college#educate yourself#educate yourselves#studyspo#studyblr

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

0 notes

Text

cw: arranged marriage, fluff, neglect at the beginning, ratio falling hard, pining, ratio being jealous of aventurine, unedited bc i wrote this with my heart not my brain

my brain has been thinking about an arranged marriage fic with dr. ratio...

he isn't kind to you at first, less than happy to share a life with a mere acquaintance. he's heard about you before in passing, noting your achievements with a grain of salt because nothing about you particularly mattered to him, irrelevant against the mass of scrolls and books he needs to read.

you don't really disturb his normal routine too much. you move in to his estate with a fair share of your belongings, but none of them crowd his house too much. you have your own room, pristine guest room unearthed by your artistic touch.

aside from dinners, you don't get to see each other too much. he starts his mornings early, getting up at the crack of dawn to exercise and start his day with a hearty meal. you wake up later, partaking in a slow morning, and if you glanced out the window, you might be able to see your husband running laps around the expanse of his gardens.

you admire his dedication and routine, it's fascinating to live beside a genius. everyday, the chest table that sits in the living room changes, the black and white pieces never remaining where you last recalled. the size of his blackboard is impressive, and yet too small to fit all of the formulas his brain remembers, hands effortlessly dancing along the surface to scratch number after number.

a frequent order of his estate is chalk. a new pile is delivered every three days, and he goes through them without fail every time.

during dinner, he tries to spare some conversation with you. you don't tell him too much about your day, not wanting to bore him with your menial chores. he's only half-listening either way, so you'll feign understanding about his work when he explains what he's up to.

ratio is not an attentive husband, but he doesn't mistreat you, either. he allows you to spend his assets without too much care, doesn't police your everyday tasks, and also doesn't bat an eye at other men or women. his pursuit of intelligence is important, and your wellbeing would not come in between that.

your monotonous, distant routine changes one autumn dusk. you're perched in the front yard with an easel set up before you, the sky in front of you now a blend of pink-purple hues. he returns home earlier than you expected, carriage stopping at the front of his estate, and he witnesses you in your tranquil state.

the paint strokes on the canvas before you are skilled, and show years of dedication to the craft. you're so invested in the piece before you, that you don't even hear him approaching until he calls your name.

"the night turns colder with each minute. shouldn't you come inside before you fall ill?" the scholar greets, and you're snapped out of your creative reverie, looking over at him.

"oh, i had not realised. let me clean up here, first." you take your canvas off the easel, but to your surprise, your spouse kneels down to organise your oil paints back into their box.

"make haste, then," he urges.

during dinner, he can't help but be curious over your hobby, the stubborn splotches of paint clinging to your hands visible to him. that night, you engage in uninterrupted conversation, and discover that he's an artist himself- a sculptor. it calms him, and all the statues reside in a removed room, adjacent to his study.

despite your years of matrimony, you had never once dared enter his study, but the design is so fittingly him. it is organised (well, as organised a genius can be), with shelves and shelves filled with books, discarded scrolls lay around the room, but even then, his taste for greco-roman aesthetics are seen. roman dorics act like stands for little plants, and his many certificates are displayed, along with other achievements.

(his study is overwhelmingly filled with them. though you knew of the merit of the man you were arranged to be married to, you had never known just how expansive the list is. perhaps, that only made him more intimidating to you, standing beside a genius does not feel so light to say anymore.)

he shows you his sculptures, and though many of them are... self portraits... the likeness is disgustingly accurate. it was as if he had casted himself in plaster and displayed it proudly. you wonder how long he must have stared in the mirror to perfect their appearance.

but, there are also various other formidable statues. some of people you recognise. you compliment his skill and don't get to see the blush that spreads along his cheeks.

it seems that you've chipped a way into his heart, because between brushstrokes and chiselled marble, he falls in love with you.

ratio knows he didn't start off being the best husband, but he tries to now, and begins by being present. asks you to dine together where possible, listens when you're talking about your day, and the two of you can be seen venturing downtown together; an unbelievable sight for those who believed that ratio was romantically inept.

perhaps, an even more unbelievable sight, was the soft smile on his face that glanced at you very adoringly, and how you remained unaware of his affections.

and, maybe a jealous veritas ratio is just as unbelievable.

he is practically glaring daggers at the side of a certain blond's head. ratio has never been fond of the scheming businessman, aventurine, and is even less so of the fact that you seem so close to him, more than you are with your own husband. you're speaking with him like how one would with old friends, a peaceful visit to the markets turned sour by his presence.

when you finally, finally, finally, bid farewell to aventurine, who gave ratio a look that signified he was up to no good, your husband held your hand in his gloved one with an unforgiving grip. his mood is dampened for the remainder of the day, and is only made better when you enquire about his sudden glumness, visiting his office to see if he was alright.

you leave him with a kiss on the crown of his head, and a whisper of 'goodnight', before retreating to your chambers, and the only thought that circulates in his head for the rest of the night is you, and how he's going to sweep you off your feet.

#*ੈ✩‧₊˚ earf's ideas that i'll never write#earthtooz: honkai star rail#dr ratio x reader#veritas ratio x reader#honkai star rail x reader#hsr x reader#ratio x reader#dr ratio fluff#dr. ratio x reader

5K notes

·

View notes

Text

A Cure for Frostbite

pairing: royal!sunghoon x fem!reader – w/c: 7209

synopsis: In the hush of the imperial palace, a forbidden romance blooms between Sunghoon—the emperor’s youngest son—and Y/N, a quiet apothecary meant to live in the shadows.

What begins with stolen glances and subtle gifts deepens into something dangerous and all-consuming. Y/N knows the risk. Sunghoon does not care. When their closeness is discovered, she pulls away to protect them both—but Sunghoon, desperate and lovesick, would burn the whole kingdom for one more moment by her side.

genre: romance, longing, historical romance, inspired by the apothecary diaries, fluff? idk, this is just a short drabble

In the eastern quarter of the Imperial Palace—past the lacquered gates where the painted cranes arched their wings eternally in mid-flight, and where plum blossoms fell like memories onto pale stone—there resided a young woman of no lineage, no crest, no glory but for the clarity of her mind and the elegance with which she existed.

Her name was Y/N, though in the palace she was called nothing so intimate—merely the apothecarian, the clever one, or sometimes, in the hushed voice of women who admired and resented her in equal measure, the beauty in white. She wore no silk but her modest uniform, no gold save the sheen of oil that glossed her hands after grinding herbs for the dowagers' sleep and princes’ fevers. Still, she carried herself as if the air bowed for her passage.

She had eyes like tea under moonlight—dark, clear, reflective of depth not seen but only guessed—and a mouth that rarely smiled, though when it did, it made even the most solemn of guards avert their eyes, ashamed to have witnessed it.

Though she never meant to be seen, she was always noticed.

To the north of that same palace, behind the walls embroidered with dragons in thread spun from silver, lived the youngest son of the Emperor.

His name was Sunghoon, the frost prince. The court called him His Serene Highness, or sometimes simply the son of Winter, for he rarely spoke in public and bore himself with a distance that even snowflakes respected. He was as beautiful as a sculpture chiseled from ice and candlelight: all pale skin, raven-black hair, and long eyes that seemed to know too much.

Yet his closest friends—noble but not royal—knew another Sunghoon. Heeseung, with the mind of a scholar and laughter like wind through open fields, and Jake, ever the diplomat’s son, quick-witted and honey-tongued, both saw through the iciness. Behind the closed shoji of his chambers, Sunghoon was warmth incarnate. He laughed at Heeseung’s ridiculous poems. He argued passionately over the best blade oil. He lay on his stomach in boyish laziness while Jake debated love and loyalty like a playwright.

He was brilliant with the sword. Too brilliant. So brilliant, the Emperor forbade him from battle.

Still, sometimes—when the moon was fat and the guards were drunk with wine—Sunghoon vanished from his quarters. And when he returned, bruises bloomed like violets along his ribs. Jake sighed. Heeseung scolded. Sunghoon only smiled, one incisor peeking out as he whispered, “I’m not dead yet.”

The two might never have crossed paths—he, a constellation born to rule; she, a shadow who kept others alive—but fate has a taste for irony, and palace walls are not made to keep hearts in.

It was early winter when Sunghoon saw her for the first time. The palace was full of cold breath and firelight. The Empress Dowager had taken ill—fevered, delirious, calling for her lost sister—and the court physicians, all swollen with status and silk, debated in circles that bled into days. Decoctions failed. Prayers echoed unanswered.

Then the apothecarian was summoned.

She entered the Dowager’s chambers like a whisper. A bundle of vials at her hip. Hands scrubbed to sanctity. She did not bow to impress, nor tremble under the weight of royal eyes. She asked only for quiet and for linen steeped in white chrysanthemum.

Sunghoon was there, in the shadow of a carved screen, bored and suspicious, idly listening to the Emperor rage at useless cures. He had no interest in women of the court—they preened like birds but spoke like reeds: all rustle, no root.

But then she spoke. Calm. Certain. Clear.

“The fever is not of the lungs but of the gut. She was fed peach kernels in her wine. The poison sleeps in sweetness.”

And the world paused to listen.

Sunghoon leaned forward.

“Who is she?” he asked, voice barely more than a breath.

Jake, beside him, shrugged. “They say she’s from the southern provinces. No family of name. She treats the kitchen maids and concubines like they were sisters.”

Sunghoon’s gaze remained fixed.

“She’s lovely,” Heeseung noted, tilting his head. “Though you’ll find no courtship there. She is wedded to her work.”

Perhaps it should have ended there—a silent admiration, an echo of curiosity, something he could dismiss with a sparring session or a bath in the onsen.

But the gods had not designed Sunghoon’s heart for quiet.

Three days later, Y/N was tending to a minor injury in the soldier’s infirmary—a foolish boy had broken his thumb while wrestling a pig, and the shame hurt more than the swelling—when she turned and found him at the door.

She knew him by title. Knew him by face, too, for who in the palace didn’t? The frost prince himself, sculpted by the heavens, lips too red, eyes too clever.

But she did not lower her gaze.

“Your Highness,” she said with the same tone she used for burnt cooks and sobbing handmaidens. “Are you ill?”

His lips curved just slightly.

“No,” he said. “But I could be.”

She blinked. Not a blush. Not a smile. Not even a breath of amusement. Just—

“Come back when you are,” she answered, turning away.

And Sunghoon—youngest son of the Emperor, undefeated in sparring, master of every noble art—stood there, momentarily robbed of speech.

He was not used to indifference.

It was intoxicating.

In the palace, time did not move; it sighed.

The courtyards bloomed in sequence like breath drawn through the mouth of heaven—first the plum blossoms in the eastern court, then magnolias by the main veranda. In the inner palace, light slanted gently through latticed windows, dust motes dancing like polite ghosts.

And somewhere in the middle of all this—between the call of the imperial bell and the rustle of silk across polished floors—Y/N was busy being useful.

She worked like a hymn—quiet, necessary, elegant in rhythm. Her footsteps made no sound in the sick wards. Her hands moved with exactitude, her eyes alert, always measuring. When she passed, the guards straightened. The other apothecaries took note. She belonged to no noble family, had no title—but in the hush of the Emperor’s palace, her name was a soft reverence.

And still, she believed she moved unseen.

She was wrong.

It began with a fever.

Not hers.

Prince Sunghoon—third son of the Emperor, youngest of the blood, and colder than jade in winter—was brought to the southern infirmary with a low-grade fever and “mild dizziness.” A meaningless case. The other court physicians had deemed it unworthy of real concern, barely requiring an herbal rinse.

But still, the order had come directly.

“Summon her,” said the guard, voice subdued. “The apothecarian.”

So she went.

He was sitting up when she arrived, arms crossed, expression unreadable. He wore no crown, no badge of status—only a pale robe embroidered with cranes, the gold thread shimmering when the light caught it.

She bowed. “Your Highness.”

“You’re not what I expected,” he said.

She raised a brow. “And what did Your Highness expect?”

He tilted his head slightly, as though studying her shape might answer the question.

“I supposed someone less… something.”

That was the first time she was summoned to tend his wounds. She diagnosed nothing unusual—likely heatstroke from overexertion. He thanked her with a polite nod, then left.

Two days later, he returned.

“A headache,” he said. “Persistent.”

She asked the routine questions: pulse, appetite, light sensitivity. Nothing of note.

“Have you been sleeping, Your Highness?”

“Not well.”

“There must be reason then.”

He looked at her for a moment too long, then said, “Restless thoughts.”

She prescribed valerian, a gentle sedative. She handed him the powder in a folded slip of paper. He held it longer than necessary, fingers brushing hers.

“Your hands are cold,” he murmured.

She pulled away. “Apologies.”

He said nothing. But when he left, he wore a ghost of a smile.

The third time, it was a cut across his palm.

Thin. Clean. Precise.

She did not look up as she began to treat it.

“Sparring?”

“A door.”

“Really?”

“A very sharp door.”

She glanced at him then, and his mouth twitched.

“You enjoy being difficult,” she said.

“I enjoy seeing you.”

A pause. Her hands stilled, breath caught between one heartbeat and the next.

“You shouldn’t say things like that.”

“Then I won’t.” A beat. “Unless you want me to.”

By the fifth visit—something about bruised ribs and “falling down”—Y/N was no longer convinced he had any true ailments at all.

Which is when she began to notice the pattern.

Every excuse was measured. A scrape on the right elbow just deep enough to require her attention. A cough that never quite returned once her tea reached his lips. He was never dramatic, never demanding. He didn’t beg for her time; he simply made her curious.

And curiosity was a dangerous thing in a place like this.

They were tucked behind the stables where no one came at this hour — too far from the scholar’s garden, too shadowed for courtiers, too ordinary for the royal sons of heaven.

But that’s what made it safe.

Jake leaned against the wooden beam, arms crossed lazily. His outer robe was half-unfastened, exposing the ivory collar of his undershirt, still damp from sword practice. Heeseung sat on an overturned water barrel, balancing a twig between his fingers like a fan. Sunghoon was the only one who remained standing, back to them, eyes on the cloudless horizon.

It had been quiet. But Jake, as usual, couldn’t let it stay that way.

“How’s your third fever this week?” he asked, voice dry.

Sunghoon didn’t turn.

“Gone,” he replied simply.

“Hmm. A miracle,” Heeseung added. “Must be that genius nurse in the infirmary. What’s her name again?”

“Y/N,” Jake supplied, the name slipping off his tongue like he’d been waiting to say it. “The one you pretend not to look at.”

Sunghoon’s shoulders rose — barely. Controlled. Still, his silence cracked the air like a blade drawn slowly.

“Don’t be ridiculous,” he said.

Heeseung grinned. “You’ve had a cut, a cough, bruised ribs, and now a migraine. All in six days. If I didn’t know better, I’d say you were fighting wild boars on the palace roof.”

“Or,” Jake said, pushing off the beam, circling him now, “you’re just in love with a girl who smells like camphor and violet water.”

At that, Sunghoon turned. Slowly. The sun lit one side of his face and cast the other into shadow — one eye unreadable, the other glinting like a secret.

“You think this is love?”

Heeseung shrugged. “We think it’s something. Don’t you?”

Jake gave him a meaningful look. “You show up to practice late, you disappear after council lessons, and you flinch when her name is mentioned.”

“I do not flinch.”

“Sunghoon,” Heeseung said carefully, tapping the edge of his boot against the barrel, “you’re the son of the Emperor. Not just any noble boy with a soft heart and an empty title. You don’t get to fall for someone just because she wraps your hand in silk and scolds you when you won’t rest.”

A beat passed. No one breathed.

Then Sunghoon said, very quietly:

“I know.”

And something in his voice silenced even Jake.

He wasn’t denying it anymore. Wasn’t laughing, wasn’t dodging. There was no smirk, no clever retort. Just a kind of quiet devastation, like a vase you see fall before it hits the ground — the knowledge that it’s already shattered.

“But I think about her,” he continued, voice barely above a whisper. “Everywhere. In court. On the practice grounds. When I try to sleep. I see her hands folding herbs, her lips when she speaks, the way she tucks her hair behind her ear when she thinks no one’s looking—”

“Gods,” Jake muttered, scrubbing a hand over his face. “You’re doomed.”

“Tell me something I don’t know.”

Heeseung sighed. “And what exactly is your plan? Keep faking injuries until someone catches on? What then? You’ll get her dismissed. Or worse.”

“I don’t have a plan.”

Jake leaned in, all sarcasm gone from his tone. “Then you better get one. Because this—this isn’t just a passing interest, is it?”

Sunghoon looked down at his hands. Pale, unmarked. The cut she stitched had healed already. But the memory of her touch had not. He could still feel her thumb against the bone of his wrist, soft and steady. As if he wasn’t dangerous at all.

As if he were just a boy.

“She sees me,” he said. “Not the title. Not the weight. Just me.”

“That’s what makes it dangerous,” Heeseung said gently.

Jake exhaled, long and slow, then clapped a hand to Sunghoon’s shoulder.

“Well,” he said, tone brightening with mock cheer, “if we’re going down, might as well go beautifully. Just… try not to fall off a roof next time, yeah?”

Sunghoon almost smiled.

“No promises.”

The palace was quieter in the mornings — a kind of hush that clung to the marble floors and whispered along the silk tapestries. Even the birds outside seemed to know not to sing too loud. In the East Wing, where few dared to wander without purpose, the apothecarian’s room remained still, perfumed with crushed herbs and sun-warmed parchment. Y/N had long made peace with the silence there. It filled the corners others found empty. She liked it, preferred it — until he began visiting.

At first, Prince Sunghoon had been a curiosity. Now, he was a habit. One she couldn’t afford, and yet, didn’t wish to break.

She was midway through grinding dried elderflowers into powder when his shadow slipped under the threshold — silent, and annoyingly graceful for someone so supposedly clumsy with “stairs,” “fencing accidents,” and “unexpected sword-related tripping hazards,” all of which had been excuses to find himself in her doorway these past weeks.

“Don’t you ever knock?” Y/N asked, not looking up.

“I tried.” His voice carried that unbothered lilt she hated that she loved. “But your door doesn’t make a very dramatic sound.”

She finally raised her gaze — and, as always, immediately regretted it. He wore blue today, deep like lapis, with gold stitching at the collar. He looked like a painting. Like something someone else should be allowed to look at. Not her.

“Let me guess,” she said, setting the mortar aside. “You’ve come to sprain your dignity again?”

“No.” His tone was mock-hurt. “Today, I come bearing peace offerings.”

He stepped inside and held out a bundle wrapped in deep crimson cloth. She frowned, but took it — her fingers brushing against his. A spark. Annoying. Predictable.

Inside was a tiny box carved from black walnut, the grain smooth and polished. She opened it carefully. Inside lay a pressed camellia — white, preserved perfectly in wax paper. It shouldn’t have meant anything. But her breath caught.

“You steal flowers now, Your Highness?”

“It wasn’t stealing,” he said, leaning against the wall like he belonged there. “It was a diplomatic transfer of assets. The camellias by the south pond were looking too proud. I humbled one.”

Y/N snorted despite herself. “And what makes you think I’d want this?”

“Because I noticed you keep dried petals tucked into your books,” he said, too casually. “And I thought — perhaps the apothecary who lives among crushed things might like something still whole.”

The words landed quietly between them, heavier than the flower.

Y/N turned away before he could see the heat in her face, busying herself with empty jars that needed no rearranging. “You should go,” she said, softening the words by not meaning them. “If your father finds out you’re sneaking around the herb rooms again—”

“He won’t,” Sunghoon replied, strolling deeper into the room, idly picking up a cork-stoppered vial. “No one follows me here. You’re the only one who bothers to talk to me for longer than a bow and a breath.”

She glanced at him sidelong. “That’s because I have no sense of self-preservation.”

“No,” he said, turning to face her properly. “It’s because you see me.”

Y/N froze.

There it was again — that subtle thread he always managed to pull. The one that tugged her thoughts loose, made her chest feel too full, her carefully composed indifference fray at the edges.

She recovered quickly. “You’re not very hard to see. You dress like a storm cloud at a wedding.”

He smiled. Slowly. “And you deflect like a cat cornered in sunlight.”

She looked down, trying not to. Trying not to give him the satisfaction of knowing how easily he undid her, just by standing there, just by bringing her quiet things and asking for nothing. Or pretending to.

“You can’t keep doing this,” she said after a moment. Her voice was steady, but only just. “Bringing me things. Spending time here.”

“Why not?”

“Because.” She turned to face him. “Because it means something.”

His gaze softened, the jest in him gentled. “It already means something,” he said. “The difference is—I’m not afraid of that.”

Y/N’s breath trembled before she could catch it. The truth was, she was afraid. Not of him. Of what he made her want.

The room felt too quiet then. The walls too close. She hated how much she wanted him to stay.

She didn’t stop him when he sat across from her on the low bench by the window, nor when he rested his elbow on the table, propping his chin in his palm like a boy too young to be royal, too sincere to be a prince.

“Tell me what you’re working on,” he said.

“You’ll be bored.”

“I’m already bored,” he replied. “That’s why I’m here.”

She hesitated. Then reached for a bundle of dried angelica root. “It’s a formula for headaches. Not that you nobles ever suffer from such mundane ailments.”

“On the contrary,” he said. “Palace life is a headache.”

She looked at him again, and this time, allowed herself to smile — just a little. He smiled back, like it was the only thing he needed today.

Outside, the sun crawled along the stone floor. The silence returned, not unwelcome, but newly charged — no longer an absence, but a presence.

And when he left — hours later, after they’d spoken of everything and nothing, after she’d almost, almost leaned too close — he left another camellia on her desk. This one pink.

And Y/N sat there long after the quiet reclaimed the room, staring at the flower, and wondering which would be her undoing first: the silence… or the boy who kept breaking it.

It had rained that morning— one of those patient, whispering rains that speak not to the ears but to the bones— making everything soft and grave, as though the earth itself bowed its head. The palace corridors, built of quiet and secrets, gleamed faintly with light that had not quite forgiven the clouds.

The apothecary wing, tucked in its solemn corner, held stillness like a breath. Y/N stood at her worktable, grinding valerian root with the sort of focus born only of desire to forget. She knew he would come. He always did. Before she heard him, she felt him—a shift in the air, the drop in her stomach that never warned, only reminded.

“You’re early,” she said, not lifting her gaze.

“You sound disappointed,” came his reply—low, silk-lined, already smiling.

She ground the root with more purpose. “I’m not. Only concerned. Your appearances are beginning to resemble habits.”

“I’m told habits become sins,” he mused, stepping further in. “And I do enjoy sinning, when it leads me here.”

Y/N looked up, against her better judgment. He stood with the storm still clinging to his cloak, a soft sheen to his hair, lashes damp from the air’s affection. And that face—he wore it like a mask of royalty, but his eyes betrayed him every time. Too honest. Too intent.

“Cloak off,” she muttered. “The floors are older than your lineage.”

With a theatrical sigh, Sunghoon complied. “How tragic, to be bested by floorboards.” He hung the garment neatly by the door, revealing a simpler tunic beneath—though even his simplicity was threaded with gold. A boy born of thrones pretending to be common.

She turned back to her bench, her fingers now arranging glass vials. “I should forbid you.”

He approached quietly, placing something beside her hand—a small, folded parchment. She opened it. Inside, between wax paper, lay forget-me-nots. Bruised blue, delicate as breath.

“They grow by the east garden wall,” he said. “No one ever looks. I thought of you.”

She swallowed. Her hands, traitorous things, lingered too long on the stem.

“What do you want from me?” she asked, softer than before.

Sunghoon leaned on the edge of her table. “Nothing,” he said, “you do not already give me freely.”

“That’s dangerous talk.”

“I’ve never feared danger.”

“You should.”

“I do,” he said. “But I fear you more.”

She dared glance up again. Mistake. He was too near. Too near and too beautiful and too aware. His smile did not ask—it confessed.

“Your Highness,” she said, voice barely spoken, barely hers. “This is madness.”

He tilted his head. “Then let us go mad together.”

Before she could reply, the world shifted—sharp as a blade drawn in sleep. A knock. Firm. Two strikes against the heavy door.

Her heart caught flame. Sunghoon moved faster than breath. To the back wall, where apothecaries kept their less lawful secrets, and she, without speaking, reached under the second shelf. A hidden panel. It clicked open. He vanished.

By the time she turned, her hands had already remembered calm. The High Steward’s assistant entered—neat, bloodless, and suspicious.

“Apothecarian,” he said, “the Empress’s physician requires belladonna.”

“Of course,” she replied, not smiling. “It’s ready.”

She retrieved the sealed vial. “Two drops, no more. It is a generous poison.”

He took it, then paused. “I thought I heard voices.”

She let her lashes fall. “Dried herbs whisper, when they settle. They are not polite.”

His lips twitched. He left.

She waited. Waited—until the silence returned to its rightful shape.

The panel creaked. Sunghoon stepped out, brushing cobwebs off his shoulder.

“Herbs whisper?” he said.

“Do not ever make me lie like that again.”

He looked at her—not with amusement this time, but with something gentler. Almost reverent.

“You risked yourself.”

“You would’ve done the same.”

He stepped toward her, his expression rare and unfamiliar. Stripped of wit.

“I’ll stop,” he whispered. “If you ask.”

The room stood still. Even the tinctures held their breath.

But she—she said nothing.

A quiet exhale left his lungs. He stepped closer, not touching, never touching. His eyes were dark and steady. His lips slightly parted, like he wanted to say something else — or kiss her instead.

“Next time,” he said, “I’ll bring violets.”

And yet, the next time Sunghoon came to see her, he broke his promise — and brought no violets.

Y/N no longer startled at the sound of his boots on the stone. Her breath always caught, but she no longer flinched.

Sunghoon had a manner of entering her space as if it were a secret they shared. He never announced himself loudly. He would lean a shoulder against the doorway, gloved fingers smoothing over the doorframe like it was a violin string, something to coax sound from. His voice, low and calm, carried the weight of meaning only she could hear.

"Tell me," he said once, eyes trained on the steam rising from a copper pot, "do you ever mix something too beautiful to use?"

Y/N glanced up, wary of the trick behind the question. “Sometimes,” she said. “And sometimes I make it just to see it undone.”

He smiled — one of those half-smiles that never touched his mouth, only his eyes. “Like poetry. Or politics.”

They talked. Always. Yet always around the thing.

Each word was a petal plucked and dropped, an offering, a risk. There was a strange formality between them, as if they had signed a treaty neither remembered writing, and it held — barely — by the virtue of long, drawn glances and averted eyes.

She should not have liked how often he stayed. Or how he never came without a token. Once, a thin chain of silver, smooth as river water. Another time, a piece of pale blue sea glass. “I found it on the windowsill,” he had said. “Or perhaps it was meant for you.”

He didn’t ask to stay. But he did.

Tonight, it was nearing dusk. The sky beyond the narrow slats of the window had turned pale with lilac — that sharp color of confession — and the wind scratched at the stones. Y/N moved quietly between shelves of vials and scrolls, her fingers absently arranging things that were already arranged.

She could feel him.

He had been sitting at her worktable for nearly twenty minutes, one leg crossed over the other, running his thumb along the edge of a small, leather-bound book he hadn’t opened.

“You know,” he said, his voice sudden in the silence, “if I were less restrained, I might steal a bottle or two. Something to fake my own death. Or sleep for a hundred years.”

Y/N exhaled, slow. “And what would that accomplish?”

He tilted his head. “It might buy me time.”

She turned her back to him. The scent of clove and crushed rosehips masked her disquiet.

“You already steal too much,” she said, her voice cooler than intended. “You take my hours.”

That made him laugh — a sound like snow melting too fast.

“But you never ask me to leave.”

She turned then, the twilight catching in her lashes. “Would you, if I did?”

He looked up at her. Really looked.

“No.”

There was a beat — long, strange, reverberating.

The room pressed in with its warmth, the scent of boiling thyme, the hush of wind through stone. Outside, the palace was a thousand windows lit with a thousand lies. Inside, the air between them crackled — but softly, the way a fire does when no one is watching.

He rose, slowly, as though standing undid something inside him.

“I brought something,” he said, reaching into his coat.

Y/N’s breath hitched. The offerings always frightened her more than his gaze. A man like him — born to the edge of crowns and war councils — should not know how to choose soft things. But he did.

He placed the object in her hand. It was a ring of carved wood, shaped like a lily, the grain polished until it glowed like honey.

“I saw it,” he said simply, “and thought of your fingers.”

Y/N did not reply. She couldn’t. Not with her throat tightening.

Sunghoon leaned a little closer — closer than the day before. His voice dropped into something just above a hush.

“Will you ever tell me the truth?” he asked. “If I asked for something dangerous.”

She met his eyes — foolishly. It was always a mistake, but one she made again and again.

“What is it you’d ask for this time?”

He didn’t smile this time.

“Your want.”

The words were clean. Precise. Unflinching.

Y/N held her breath so tightly it hurt her ribs. She wanted to step back, to be clever, to vanish into tinctures and linens and respectable restraint. But all she could say — weak and scalding — was:

“You wouldn’t know what to do with it.”

Sunghoon's mouth curved, slowly.

“No,” he said. “But I’d like the chance to try.”

And then he was gone. The door clicked shut behind him like a confession swallowed.

Y/N stood alone in the warm hush of her chamber, her heart knocking against the ribs that kept it captive. The ring sat in her palm, delicate and treacherous. Like him.

Like her.

She closed her fist around it.

The apothecary’s workroom lay quiet beneath the weight of late afternoon, gold and shadow laced across the stone floor in slow, flickering patterns. The air smelled of dried rosemary and orange peel, warm and crisp, as though the walls themselves had absorbed the scents and refused to let them go. Y/N was slicing valerian root with studied precision, the motion mechanical, her thoughts far from the blade. She had not seen Sunghoon in days.

And yet, it was the memory of the last time that haunted her most.

He had come empty-handed, no violets, no little token tucked behind his back or cradled in his palm. Only his voice, low and honey-warm, and his eyes — luminous, exhausted, pleading for something he hadn’t dared name. She had been laughing at some dry, clever nothing he’d said, her fingers stained green from herbs, when the door opened with a hush, not a bang — but it was worse that way. Quieter things cut deeper.

She didn’t hear them at first. Only the change in Sunghoon’s eyes — that flash of something gone cold — made her turn.

Heeseung stood just inside the threshold, expression unreadable, though a shadow of amusement danced at the edge of his mouth like a secret he hadn’t decided whether to keep. Jake lingered just behind him, eyes sweeping the room with a curious sort of slowness, like someone looking for the shape of something they already suspected.

“Didn’t know you’d taken up herbal studies, brother,” Heeseung said softly. Not biting. Not warm.

Y/N went still. Not a dramatic gasp, not a flinch — but the kind of stillness born of instinct, like a deer in tall grass.

She did not look at Sunghoon. She looked at her hands. She looked at the flask of steeped feverfew she hadn’t yet poured. She looked at the distance between her and the prince and found it suddenly, unforgivably small.

They didn’t look at her face.

That was what made her throat tighten.

They looked at the curve of her spine, at the disarray of the worktable behind her, at the ribbon coming undone from the end of her braid. Jake’s gaze caught on the worn edge of the stool where Sunghoon had been sitting. Heeseung’s gaze drifted to the windows — closed. The door — bolted before they'd arrived.

There was no accusation. Just awareness.

Sunghoon, to his credit, did not falter. His voice was the same careless silk he always used when pretending not to care.

“A tincture,” he said, lifting an empty bottle like a jest. “Terribly dramatic cough, as I’m sure you’ve both heard.”

Heeseung arched a brow, not smiling, not frowning. Just seeing.

Jake tilted his head. “And only our palace apothecary could soothe it, of course.”

There was no laughter. Only the echo of it, implied.

Y/N moved before she could think. She turned from the table — not toward them, not toward him. Just away. She gathered stray petals with trembling fingers and tucked them into the herb press, not trusting her voice, not daring to exist more loudly than the silence had allowed.

She had not looked at Sunghoon. She had not spoken. She had wrapped herself in the invisible distance that women like her were always meant to maintain in palaces like these — the veil between the bloodlines and the hands that tended them.

And now, in the dim, the world was quieter without him. But it did not feel safe. It felt like exile.

She did not go near the eastern hallways where he often walked. She passed his shadow in the garden without turning her head. She handed tinctures to court ladies with her voice like poured water, never lingering. And though no one said anything — though Heeseung and Jake made no scandal, no whisper behind fans or folded letters — she knew what the silence meant.

Sunghoon, for his part, did not relent.

She found, three days after the visit, a folded slip of paper on her table — the corner weighed down with a smooth, black riverstone. She told herself not to read it. She did.

“If you must pretend not to see me, then at least let me look. You’re in everything I notice anyway.”

Her hands had trembled the entire morning.

Then came a sprig of lavender tucked beside her mortar. A note scrawled in a lazy, boyish script: “This smells like how you speak. Calm, but with the threat of storms.”

And finally — this morning — a book.

Worn, water-stained, slipped between her ledgers. The cover, a faded brown. Inside, pressed between pages, a feather. Pale, grey-blue. His writing on the inside cover:

“I found this and thought of you. Even when you avoid me, I find you.”

She nearly wept.

But she could not go to him. She dared not. She saw the way Heeseung watched her now. The way Jake’s eyes softened with pity.

Sunghoon was the emperor’s son. She was a woman who smelled of rosemary and flame, whose hands healed but did not belong at court.

And yet—

And yet, when she heard his voice at the edge of her door one evening, whispering her name as though it was something holy, her resolve crumbled like dried petals.

“Y/N.” A whisper. “I know you’re in there.”

She did not respond. Her breath caught in her throat.

A pause.

“I think of you at night. When the palace is quiet. When the oil lamps make everything look like candlelight. I think of you every time I walk through the gardens, and I hope — I hope you’ll look at me again. I’m not asking for scandal. Just… a moment. A breath. Yours.”

Silence.

“I never cared what Heeseung or Jake thought. But I care that you won’t meet my eyes anymore.”

Her hand rested on the doorframe. Her body leaned toward him before her mind gave it permission.

“I feel,” he murmured on the other side, “as though I’ve done something terribly wrong. And yet, I’d do it again, just to hear you laugh.”

A throb in her chest.

She stayed silent. But her hand drifted to the door, fingers pressed to the wood where his voice had lingered. And he—on the other side—rested his palm in the same place.

No words.

Only that stillness.

Only that ache.

He left soon after. She heard his steps retreat, slower than usual.

But when she opened the door ten minutes later — the hall empty, the lanterns flickering soft — she found a single violet pressed to the floor.

A promise. A waiting.

And for the first time in days, she allowed herself to smile.

It was not a clean absence.

Y/N did not vanish in the elegant way of snow melting at dawn, nor in the dignified manner of a flower curling back into itself at dusk. She withdrew with a surgeon’s precision — averted eyes, shortened words, missing hours. Her distance was quiet, but brutal. A thousand tiny cuts beneath the surface.

And Sunghoon was bleeding.

He had tried to be patient. Dignified. He had tried, in the first day, to believe she was simply tired. Busy. The second, he convinced himself she was angry — justly so — and would come around. The third day, he stood at the far edge of the apothecary’s corridor like a man waiting for an execution, watching the door remain closed, listening to the echo of her not coming.

By the fourth day, he began to unravel.

There was a peculiar kind of madness that accompanied wanting someone you could not touch. He had endured the ceremony of court, the empty chatter of noblewomen, the endless scrolls of diplomatic grievances — all with her ghost pressing against his ribs. Her voice, her frown, her mouth — her mouth — all of it lived behind his eyes now. Memory had sharpened her into a weapon.

He saw her everywhere. In the slope of a wrist at dinner. In the laugh of a passing servant. In the lavender light before morning. And it was never her. Not her.

She had ruined solitude for him.

He could no longer sit in silence without imagining what she might be doing — where she stood, if she was thinking of him, if she hated him now. And worse — far worse — he feared she did not hate him at all, only feared him. Feared them.

As she should.

Because what they had — what they had almost had — was blasphemy. An apothecarian and a prince. A quiet girl with ink-stained fingers and a man raised in silk and distance.

But he had tasted the idea of her. And now everything else was ash.

He did not sleep. Not truly. When his body did surrender to exhaustion, he dreamt in fever. Of her breath against his throat. Her voice saying his name in a tone no court would dare speak it. He woke with the taste of longing like metal on his tongue.

He kept the ribbon she had dropped. Blue, frayed, unremarkable — and now the holiest thing he owned.

He would take it out at night, when the palace was still and the moon lay against the windows like a watching eye. He would hold it between his fingers and imagine the weight of her hair, the curve of her neck, the warmth of her cheek if he ever dared brush it.

His thoughts were obscene. Not for their vulgarity, but for their intimacy.

He thought of her hands — not on him — but doing ordinary things. Threading a needle. Stirring a tincture. Tucking a strand of hair behind her ear. He thought of her voice in the morning, low and rasped with sleep, and what it might sound like laughing beside him in bed.

He thought of her in every version of a life he was forbidden to have.

It made him furious. And hopeless. And alive in a way he had never been before.

She had become a wound he did not want to heal.

And so he found himself haunting the spaces she might occupy. Not speaking, just… hoping. A glimpse. A shadow. A sigh. He would take anything.

He told himself he would not go to her again. He had already given her too many chances to break him.

But then the rain came — thick, sudden, angry — and he remembered the way she never ran from storms.

And that was all it took.

He did not think. He ran. Not for the court. Not for the family name. Not for dignity.

He ran for her. Always, always for her.

And if she did not want him — he would hear it from her lips. Not her absence. Not her silence.

Her voice.

If he was going to be destroyed by love, it would be by her hand. And he would thank her for the mercy of it.

The rain had begun sometime past dusk — first as a whisper, then a warning. The sky bruised violet and steel. The clouds sagged with a weight they could no longer bear.

And Y/N ran.

Not fast. Not foolishly. But with a resolve that burned through the marrow of her bones. She had meant to go only as far as the conservatory’s side door — meant only to clear her thoughts, to feel air that wasn’t thick with dread and guilt and his name in her chest.

But she had wandered too far.

And he had followed.

The storm cracked open overhead, not loud — not yet — but with a rolling growl like something ancient waking up.

Y/N turned only when she heard his voice, ragged against the wind.

“Y/N.”

She froze, the syllables like a thread caught at her spine. She had not heard that voice in days. She had avoided him. Faithfully. Brutally. She had turned corridors. Sent messengers in her place. Hidden behind propriety and fear and trembling silence.

And yet here he stood.

Soaked. Disheveled. Breathing as if he’d been running after something he could no longer bear to lose.

“What do you want, Sunghoon?” she asked, without turning.

“I want—” his breath caught on the storm — “I want to know what crime I committed that was worse than loving you.”

Her eyes stung. Rain or not.

“You don’t get to say that,” she said, voice low. “Not when it can ruin us both.”

“I would be ruined a thousand times over,” he said, stepping closer, “if it meant one more moment with you.”

The wind dragged his hair into his eyes. His cloak was soaked through; he hadn’t brought a hood.

“You are the Emperor’s son,” she said bitterly. “And I — I’m the girl who measures out lavender in teaspoons and brews fever tinctures for people who forget my name.”

“You think I forget your name?” His voice cracked. “You think I forget the way you speak when you’re tired, or the way you smell like chamomile even when you’re angry? You think I don’t remember every time you touched my wrist without meaning to, or the way you never look at me the same way twice?”

She turned then, water streaming down her cheeks, rain or tears — she couldn’t tell anymore.

“It’s not fair,” she whispered.

“No,” he said, voice thick. “It isn’t.”

Lightning shattered the sky in the distance — silver slicing through blue.

“Do you know what it’s been like?” His voice trembled with the storm. “To be watched every moment? To have nothing of my own — not even my heart? And then to find it — you — and realize even that I cannot keep?”

Her chest ached. Her hands trembled at her sides.

“You were never supposed to come into my life,” she said. “Not like this.”

“And yet,” he said, a crooked, broken smile on his lips, “I have memorized your footsteps in the hallway. I know the exact hour the light hits your table in the morning. I carry the sound of your laugh like a prayer.”

“Stop,” she begged, voice splintering. “Please.”

He took a step forward.

“Do you want me to?”

Her silence was a wound.

The rain beat against the marble, against the ivy-covered walls, against the skin of two people too young to know how to carry love like this, and too old to pretend it didn’t matter.

“You make me want to be reckless,” he said, quietly now. “You make me hope, even when I know better. You make me believe I was made for something more than duty.”

“I’m afraid,” she admitted.

“I’m already afraid,” he replied. “Being with you wouldn’t change that. But at least I’d be afraid with you.”

She didn’t move.

And then he whispered, “Tell me to go. Look me in the eye and say you feel nothing and I will never trouble you again.”

The air hung between them like the breath before a kiss.

Her lips parted — but no lie could form.

Instead, she said: “If you stay, Sunghoon, we fall. You and I — we lose everything.”

“I’d rather fall with you than rise without you.”

And finally — finally — she closed the distance.

Rain between them. Fire within.

She touched his face, trembling. He leaned into her palm like a man starved for warmth.

Their kiss — when it came — was not soft.

It was desperate. It was furious. It was years of loneliness unraveling in the space between one heartbeat and the next.

The storm howled on.

But in that moment, neither of them heard it.

author's note: hiiiiiii! so… surprise?! I decided to write this short story because, as you can probably tell, I became obsessed with The Apothecary Diaries (I fell in love with Jinshi and my best friend—shout out to heejamas—and I haven’t been able to think about anything else).

after I finished the frog episode (if you know, you know), I dreamed of Sunghoon as the emperor’s son and I just knew I had to write something about it.

this is my first time writing a short story, but I think I managed to put everything I wanted into words! I hope you enjoy it—it's very different from what I’m used to writing, but it was necessary to remind me that I love writing and that it’s a hobby that brings me so much joy!

#enhypen sunghoon#sunghoon#sunghoon x y/n#sunghoon x reader#enhypen au#enhypen fanfiction#park sunghoon#park sungho x reader#enhypen romance#enhypen fluff

526 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ok, yes, but now I can't get the ghost Shen Jiu in Ghost City out of my head, perhaps having his own tea house (which other ghosts disparagingly treat as a brothel), where he gives jobs as dancers, waitresses and cleaning assistants to other ghost women who require it.

And everyone knows that Shen Jiu is someone unsociable and hostile like a territorial cat that hisses at anyone who gets too close. He has his own little corner in Ghost City filled with female company, and even sometimes plays a few pieces of music with his long black ghost nails, and everyone just wonders... what happened to him in his mortal life? It's obviously rude to ask, but that curiosity is there. He looks like a scholar, he has enough rage to be a lower rank wrath ghost. He has rough and mean spiritual power running through his veins, but his polite mannerisms and gestures are... refined, befitting someone of high standing.

Who could this Shen Jiu have been when he was alive?

No one knows, no one asks, and they just leave him in his tea house, serving and offering jobs to women who need it, taking refuge with them from the terrors of a mortal life that he can't seem to leave behind.

#svsss#svsss ideas#svsss au#tgcf#ghost city#svsss x tgcf#shen jiu#ghost shen jiu#a happy ending? ambiguous

646 notes

·

View notes

Note

Would you be willing to dunk on speak more on mainstream feminist theory you're reading? And/or share some of the non-juvenile feminist theory you've read?

(Note: I will try to link to open access versions of articles as much as possible, but some of them are paywalled. if the links dont work just type the titles into google and add pdf at the end, i found them all that way)

If there’s any one singular issue with mainstream feminist thought that can be generalized to "The Problem With Mainstream Feminism" (and by mainstream I mean white, cishet, bourgeois feminism, the “canonical feminism” that is taught in western universities) it’s that gender is treated as something that can stand by itself, by which I mean, “gender” is a complete unit of analysis from which to understand social inequality. You can “add” race, class, ability, national origin, religion, sexuality, and so on to your analysis (each likewise treated as full, discrete categories of the social world), but that gender itself provides a comprehensive (or at the very least “good enough”) view of a given social problem. (RW Connell, who wrote the canonical text Masculinities (1995) and is one of the feminist scholars who coined/popularized the term hegemonic masculinity, is a fantastic example of this.)

Black feminists have for many decades pointed out how fucking ridiculous this is, especially vis a vis race and class, because Black women do not experience misogyny and racism as two discrete forms of oppression in their lives, they are inextricably linked. The separation of gender and race is not merely an analytical error on the part of white feminists - it is a continuation of the long white supremacist tradition of bounding gender in exclusively white terms. Patricia Hill Collins in Black Feminist Thought (2000) engages with this via a speech by Sojourner Truth, the most famous line from her speech being “ain’t I a woman?” as she describes all the aspects of womanhood she experiences but is still denied the position of woman by white women because she is Black. Lugones in Coloniality of Gender (2008) likewise brings up the example of segregationist movements in the USAmerican South, where towns would put up banners saying things like “Protect Southern Women” as a rationale for segregation, making it very clear who they viewed as women. Sylvia Wynter in 1492: A New World View likewise points out that colonized women and men were treated like cattle by Spanish colonizers in South America, often counted in population measures as "heads of Indian men and women," as in heads of cattle. They were treated as colonial resources, not as gendered subjects capable of rational thought.

To treat the category of “woman” as something that stands by itself is a white supremacist understanding of gender, because “woman” always just means white woman - the fact that white is left implied is part of white supremacy, because who is granted subjecthood, the ability to be seen as human and therefore a gendered subject, is a function of race (see Quijano, 2000). Crenshaw (1991) operationalizes this through the term intersectionality, pointing out that law treats gender and race as separate social sites of discrimination, and the practical effect of this is that Black women have limited/no legal recourse when they face discrimination because they experience it as misogynoir, as the multiplicative effect of their position as Black women, not as sexism on the one hand and racism on the other.

Transfeminist theory has further problematized the category of gender by pointing out that "woman" always just means cis woman (and more often than not also means heterosexual woman). The most famous of these critiques comes from Judith Butler - I’m less familiar with their work, but there is a great example in the beginning of Bodies That Matter (1993) where they demonstrate that personhood itself is a gendered social position. They ask (and I’m paraphrasing) “when does a fetus stop becoming an ‘it’? When its gender is declared by a doctor or nurse via ultrasound.” Sex assignment is not merely a social practice of patriarchal division, it is the medium through which the human subject is created (and recall that gender is fundamentally racialized & race is fundamentally gendered, which I will come back to).

And the work of transfeminists demonstrate this by showing transgender people are treated as non-human, non-citizens. Heath Fogg Davis in Sex-Classification Policies as Transgender Discrimination (2014) recounts the story of an African American transgender woman in Pennsylvania being denied use of public transit, because her bus pass had an F gender marker on it (as all buss passes in the state required gender markers until 2013) and the bus driver refused her service because she “didn’t look like a woman.” She was denied access to transit again when she got her marker changed to M, as she “didn’t look like a man.” Transgender people are thus denied access to basic public services by being constructed as “administratively impossible” - gender markers are a component of citizenship because they appear on all citizenship documents, as well as a variety of civil and public documents (such as a bus pass). Gender markers, even when changed by trans people (an arduous, difficult process in most places on earth, if not outright impossible), are seen as fraudulent & used as a basis to deny us citizenship rights. Toby Beauchamp in Going Stealth: Transgender Politics & US Surveillance Practices (2019) talks about anti-trans bathroom bills as a form of citizenship denial to trans people - anti-trans bathroom laws are impossible to actually enforce because nobody is doing genital inspections of everyone who enters bathrooms (and genitals are not proof of transgenderism!), but that’s actually not the point. The point of these bills is to embolden members of the cissexual public to deputize themselves on behalf of the state to police access to public space, directing their cissexual gaze towards anyone who “looks transgender.” Beauchamp points out that transvestigators don’t need to be accurate most of the time, because again, the point is terrorizing transgender people out of public life. He connects this with racial segregation, and argues that we shouldn’t view gender segregation as “a new form of” racial segregation (this is a duplication of white supremacist feminism) but a continuation of it, because public access is a citizenship right and citizenship is fundamentally racially mediated (see Glenn's (2002) Unequal Freedom)

Susan Stryker & Nikki Sullivan further drives this home in The King’s Member, The Queen’s Body, where they explain the history of the crime of mayhem. Originating in feudal Europe (I don’t remember off the dome the exact time/place so forgive the generalization lol), mayhem is the crime of self-mutilation for the purposes of avoiding military conscription, but what is interesting is that its not actually legally treated as “self” mutilation, but a mutilation of the state and its capacity to exercise its own power. They link the concept of mayhem to the contemporary hysteria around transgender people receiving bottom surgery - we are not in fact self mutilating, we are mutilating the state’s ability to reproduce its own population by permanently destroying (in the eyes of the cissexual public) our capacity to form the foundational social unit of the nuclear family. Our bodies are not our own, they are a component of the state. Situating this in the context of reproductive rights makes this even clearer. Abortion access is not actually about the individual, it is the state mediating its own reproductive capacity via the restriction of abortion (premised on the cissexual logic of binary reproductive capacity systematized through sex assignment). Returning to Hill Collins, she points out that in the US, white cis women are restricted access to abortion while Black and Indigenous cis women are routinely forcibly sterilized, their children aborted, and pumped with birth control by the state. This is not a contradiction or point of “hypocrisy” on the part of conservatives, this is a fully comprehensive plan of white supremacist population management.

To treat "gender" as its own category, as much of mainstream feminism does (see Acker (1990) and England (2010) for two hilarious examples of this, both widely cited feminists), is to forward a white supremacist notion of gender. That white supremacy is fundamentally cissexual and heterosexual is not an accident - it is a central organizing logic that allows for the systematization of the fear of declining white birthrates (the conspiracy of "white genocide" is illegible without the base belief that there are two kinds of bodies, one that gets pregnant and one that does the impregnating, and that these two types of bodies are universal sources of evidence of the superiority of men over women - and im using those terms in the most loaded possible sense).

I realize that most of these readings are US centric, which is an unfortunate limitation of my own education. I have been really trying to branch into literature outside the Global North, but doctoral degree constraints + time constraints + my own research requires continual engagement with it. I also realize that most of the transfeminist readings I've cited are by white scholars! This is a continual systemic problem in academic literature and I'm not exempt from it, even as I sit here and lay out the problem. Which is to say, this is nowhere near the final word on this subject, and having to devote so much time to reading mainstream feminist theory as someone who is in western academia is part of my own limited education + perspective on this topic

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

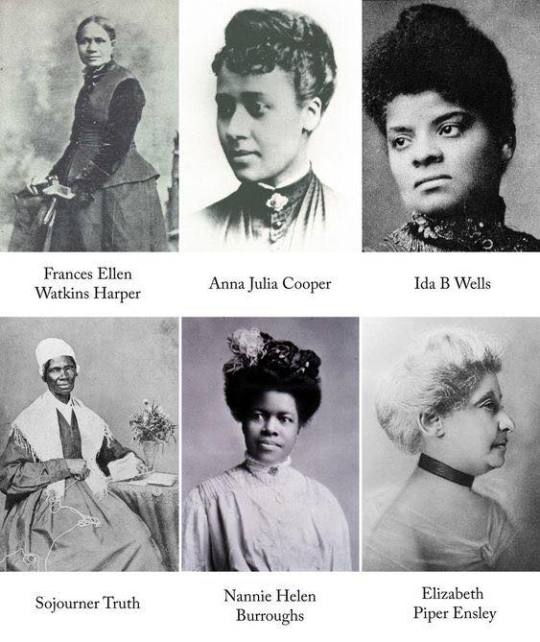

A Historical Deep Dive into the Founders of Black Womanism & Modern Feminism

Six African American Suffragettes Mainstream History Tried to Forget

These amazing Black American women each advanced the principles of modern feminism and Black womanism by insisting on an intersectional approach to activism. They understood that the struggles of race and gender were intertwined, and that the liberation of Black women was essential. Their writings, speeches, and actions have continued to inspire movements addressing systemic inequities, while affirming the voices of marginalized women who have shaped society. Through their amazing work, they have expanded the scope of womanism and intersectional feminism to include racial justice, making it more inclusive and transformative.

Anna Julia Cooper (1858–1964)

Quote: “The cause of freedom is not the cause of a race or a sect, a party or a class—it is the cause of humankind, the very birthright of humanity.”

Contribution: Anna Julia Cooper was an educator, scholar, and advocate for Black women’s empowerment. Her book A Voice from the South by a Black Woman of the South (1892) is one of the earliest articulations of Black feminist thought. She emphasized the intellectual and cultural contributions of Black women and argued that their liberation was essential to societal progress. Cooper believed education was the key to uplifting African Americans and worked tirelessly to improve opportunities for women and girls, including founding organizations for Black women’s higher education. Her work challenged both racism and sexism, laying the intellectual foundation for modern Black womanism.

Frances Ellen Watkins Harper (1825–1911)

Quote: “We are all bound together in one great bundle of humanity, and society cannot trample on the weakest and feeblest of its members without receiving the curse in its own soul.”

Contribution: Frances Ellen Watkins Harper was a poet, author, and orator whose work intertwined abolitionism, suffrage, and temperance advocacy. A prominent member of the American Equal Rights Association, she fought for universal suffrage, arguing that Black women’s voices were crucial in shaping a just society. Her 1866 speech at the National Woman’s Rights Convention emphasized the need for solidarity among marginalized groups, highlighting the racial disparities within the feminist movement. Harper’s writings, including her novel Iola Leroy, offered early depictions of Black womanhood and resilience, paving the way for Black feminist literature and thought.

Ida B. Wells (1862–1931)

Quote: “The way to right wrongs is to turn the light of truth upon them.”

Contribution: Ida B. Wells was a fearless journalist, educator, and anti-lynching activist who co-founded the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). Her investigative reporting exposed the widespread violence and racism faced by African Americans, particularly lynchings. As a suffragette, Wells insisted on addressing the intersection of race and gender in the fight for women’s voting rights. At the 1913 Women’s Suffrage Parade in Washington, D.C., she famously defied instructions to march in a segregated section and joined the Illinois delegation at the front, demanding recognition for Black women in the feminist movement. Her activism laid the groundwork for modern feminisms inclusion of intersectionality, emphasizing the dual oppressions faced by Black women.

Sojourner Truth (1797–1883)

Quote: “Ain’t I a Woman?”

Contribution: Born into slavery, Sojourner Truth became a powerful voice for abolition, women's rights, and racial justice after gaining her freedom. Her famous 1851 speech, "Ain’t I a Woman?" delivered at a women's rights convention in Akron, Ohio, directly challenged the exclusion of Black women from the feminist narrative. She highlighted the unique struggles of Black women, who faced both racism and sexism, calling out the hypocrisy of a movement that often-centered white women’s experiences. Truth’s legacy lies in her insistence on equality for all, inspiring future generations to confront the intersecting oppressions of race and gender in their advocacy.

Nanny Helen Burroughs (1879–1961)

Quote: “We specialize in the wholly impossible.”

Contribution: Nanny Helen Burroughs was an educator, activist, and founder of the National Training School for Women and Girls in Washington, D.C., which emphasized self-sufficiency and vocational training for African American women. She championed the "Three B's" of her educational philosophy: Bible, bath, and broom, advocating for spiritual, personal, and professional discipline. Burroughs was also a leader in the Women's Convention Auxiliary of the National Baptist Convention, where she pushed for the inclusion of women's voices in church leadership. Her dedication to empowering Black women as agents of social change influenced both the feminist and civil rights movements, promoting a vision of racial and gender equality.

Elizabeth Piper Ensley (1847–1919)

Quote: “The ballot in the hands of a woman means power added to influence.”

Contribution: Elizabeth Piper Ensley was a suffragist and civil rights activist who played a pivotal role in securing women’s suffrage in Colorado in 1893, making it one of the first states to grant women the vote. As a Black woman operating in the predominantly white suffrage movement, Ensley worked to bridge racial and class divides, emphasizing the importance of political power for marginalized groups. She was an active member of the Colorado Non-Partisan Equal Suffrage Association and focused on voter education to ensure that women, especially women of color, could fully participate in the democratic process. Ensley’s legacy highlights the importance of coalition-building in achieving systemic change.

To honor these pioneers, we must continue to amplify Black women's voices, prioritizing intersectionality, and combat systemic inequalities in race, gender, and class.

Modern black womanism and feminist activism can expand upon these little-known founders of woman's rights by continuously working on an addressing the disparities in education, healthcare, and economic opportunities for marginalized communities. Supporting Black Woman-led organizations, fostering inclusive black femme leadership, and embracing allyship will always be vital.

Additionally, when we continuously elevate their contributions in social media or multi-media art through various platforms, and academic curriculum we ensure their legacies continuously inspire future generations. By integrating their principles into feminism and advocating for collective liberation, women and feminine allies can continue their fight for justice, equity, and feminine empowerment, hand forging a society, by blood, sweat, bones and tears where all women can thrive, free from oppression.

#black femininity#womanism#womanist#intersectional feminism#intersectionality#intersectional politics#women's suffrage#suffragette#suffrage movement#suffragists#witches of color#feminist#divine feminine#black history month#black beauty#black girl magic#vintage black women#black women in history#african american history#hoodoo community#hoodoo heritage month#feminism#radical feminism#radical feminists do interact#social justice#racial justice#sexism#gender issues#toxic masculinity#patriarchy

612 notes

·

View notes

Text

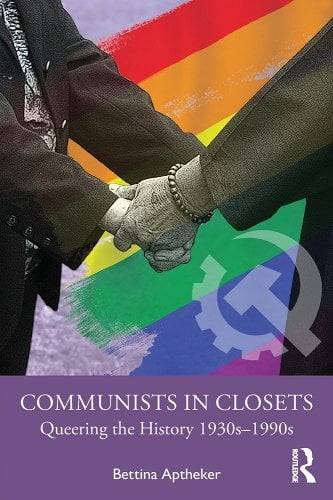

Communists in Closets: Queering the History 1930s-1990s

Bettina Aptheker

Communists in Closets: Queering the History 1930s-1990s explores the history of gay, lesbian, and non-heterosexual people in the Communist Party in the United States.

The Communist Party banned lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people from membership beginning in 1938 when it cast them off as "degenerates." It persisted in this policy until 1991. During this 60-year ban, gays and lesbians who did join the Communist Party were deeply closeted within it, as well as in their public lives as both queer and Communist. By the late 1930s, the Communist Party had a membership approaching 100,000 and tens of thousands more people moved in its orbit through the Popular Front against fascism, anti-racist organizing, especially in the south, and its widely read cultural magazine, The New Masses. Based on a decade of archival research, correspondence, and interviews, Bettina Aptheker explores this history, also pulling from her own experience as a closeted lesbian in the Communist Party in the 1960s and '70s. Ironically, and in spite of this homophobia, individual Communists laid some of the political and theoretical foundations for lesbian and gay liberation and women's liberation, and contributed significantly to peace, social justice, civil rights, and Black and Latinx liberation movements.

This book will be of interest to students, scholars, and general readers in political history, gender studies, and the history of sexuality.

(Affiliate link above)

#queer history#queer#lgbt#lgbt history#gay history#lesbian history#transgender history#making queer history

902 notes

·

View notes

Note

I think we should talk about Wu Zetian, China’s only female emperor, who historically has been regarded as a horrible and brutal leader.

She was born a commoner, became a concubine to one emperor, married his son and then took the role of emperor for herself when he died. She was politically adept, highly ambitious and extraordinarily intelligent.

History has accused her of smothering her newly born daughter and blaming a rival for her death. She had that rivals hands and feet cut off and then had her thrown into a vat of wine in which she was left to drown. She gouged out another rivals eyes and had acid poured down her throat. She wiped out 12 entire branches of a clan. She poisoned her mother. Just how accurate these things are is up for debate, but while these things might not all be true, she certainly did have several family members killed. And she did deal with her rivals and her detractors ruthlessly. Yet none of these things would have attracted criticism if she had been a man. She was no more scandalous than any other ruler during that time period.

But! Her rule was peaceful and prosperous. She avoided wars and welcomed ambassadors from as far away as the Byzantine empire. She changed laws so common people could be chosen for roles in government for their abilities rather than their name or status. She acknowledged and acted on criticisms from her retainers. She built watchtowers along the Silk Road so merchants wouldn’t be harrowed by bandits. Her reign saw women given more freedom(the ability to divorce, hold government positions, travel, hunt and ride horses, to be recognized by scholars).

She supported Buddhism and helped the religion spread and grow through commissioning temples, monasteries, and even a statue of the Buddha said to be carved in her own likeness. In the eyes of the common people, she likely would have been an incredibly popular ruler.

She remains a controversial figure primarily because of stories about her personal actions against her rivals by male Confucian officials who were prejudiced against strong and ambitious women and while they undoubtedly exaggerated aspects of Wu’s life, there is still substantial verifiable evidence of her ruthlessness.

We should also be aware that although she allegedly held her power through murder and merciless, according to Confucian philosophy, ‘while an emperor should not be condemned for acts that would be crimes in a subject, he should be judged harshly for allowing the state to fall into anarchy’ and viewed under this lens, Wu did effectively fulfill her duties as a ruler.

So we have a leader of ancient china who had two faces, one who committed acts of vile cruelty against her family and rivals and one who gave her citizens peace and prosperity.

Through a modern lens she can be viewed as an evil woman who rose from humble beginnings and coldly and calculatingly murdered her way into arguably the most powerful position in the world. A rich woman who threw crumbs to her peasant people while she lived luxuriously. She is a deadly woman, a black widow, an evil stepmother, a kinslayer. But according to historians, “without Wu there would have been no long enduring Tang dynasty and perhaps no lasting unity of China.”

The comparison to a modern mr beast obviously doesn’t hold water, but we can certainly analyze jgy to a more comparable historical figure and argue more accurately in a historical context if jgy was a good leader as the de facto emperor as the cultivation worlds Xiāndū.

It’s easy to see the comparisons between Wu and jgy, both were undesirable and deemed unfit by society. But both were politically adept, highly ambitious and extraordinarily intelligent. Both had family members murdered, perhaps sharing between them filicide. Both had a clans murdered to a man. Both are thought to have had their faces carved on religious relics for their narcissistic pleasure. Both had watchtowers built as a defense for their people. And both were torn down by the men following after them, vilified and distorted. Both forever destined to be speculated upon and misunderstood. Both of their legacy’s destroyed by rumor and falsification. It would not surprise me in the slightest if mxtx didn’t draw on Wu at least a little bit in the creation of jgy. Both Wu and jgy are culpable for some pretty heinous stuff, that can’t be denied. But like Wu, jgy also has a second face.

Moral bias and character motivation aside, his efforts to build watchtowers, his patronage of religion in the building of Guanyin temple, his fight against political corruption, his years long peaceful reign, his charity, all these things lead to the conclusion that under the rule of Confucian, he more than aptly fulfilled his role as a leader for his citizens.

And if you really want to look at Jgys leadership through a modern lens, we really don’t have to look much further than Ingersoll. “If you want to find out what a man is to the bottom, give him power.”

And really that’s part of the tragedy of his character. Because of his background he excelled when he was in a role of leadership. He was good at it.

Whether or not jgy as a literary character is a good person, is subjective and should not be used to measure his role as an effective leader.

All of that being said, jgy is my bestfriend and I love him and would I die for him.

.

242 notes

·

View notes

Note

@ The butch thing