#ancient britons

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Genetic analysis of people buried in a 2000-year-old cemetery in southern England has bolstered the idea that Celtic communities in Britain placed women centre-stage, showing that women remained in their ancestral homes while men moved in from other communities—a practice that lasted centuries.

The work supports growing archaeological evidence that women had high status within Celtic societies across Europe, including Britain, and gives credence to Roman written accounts that were often thought to be exaggerated for Mediterranean audiences when they described Celtic women as empowered.

“Men typically still dominate formal positions of authority, but women can wield huge influence through their strong networks of matrilineal relatives and their central role in the local economy,” says Cassidy.

“This is very exciting new research and is revolutionising how we understand prehistoric society,” says Rachel Pope at the University of Liverpool, UK, who has previously found evidence of female-focused kinship in Iron Age Europe. “What we are learning is that the nature of society in Europe before the Romans was really very different.”

#matrilocality#celtic women#celts#ancient history#iron age#ancient britons#empowered women#prehistory

1 note

·

View note

Text

I got curious and..

(Cassius Dio)

12 1 There are two principal races of the Britons, the Caledonians and the Maeatae, and the names of the others have been merged in these two. The Maeatae live next to the cross-wall which cuts the island in half, and the Caledonians are beyond them. Both tribes inhabit wild and waterless mountains and desolate and swampy plains, and possess neither walls, cities, nor tilled fields, but live on their flocks, wild game, and certain fruits; 2 for they do not touch the fish which are there found in immense and inexhaustible quantities. They dwell in tents, naked and unshod, possess their women in common, and in common rear all the offspring. Their form of rule is democratic for the most part, and they are very fond of plundering; consequently they choose their boldest men as rulers. 3 They go into battle in chariots, and have small, swift horses; there are also foot-soldiers, very swift in running and very firm in standing their ground. For arms they have a shield p265 and a short spear, with a bronze apple attached to the end of the spear-shaft, so that when it is shaken it may clash and terrify the enemy; and they also have daggers. 4 They can endure hunger and cold and any kind of hardship; for they plunge into the swamps and exist there for many days with only their heads above water, and in the forests they support themselves upon bark and roots, and for all emergencies they prepare a certain kind of food, the eating of a small portion of which, the size of a bean, prevents them from feeling either hunger or thirst.

Well huh... That's weird...

201 notes

·

View notes

Text

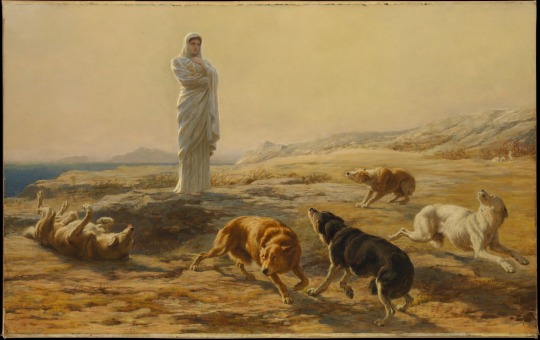

Pallas Athena and the Herdsman's Dogs by Briton Rivière

Then drew she nigh, in shape a stately dame,

Graced with all noble gifts of womanhood:

None save Odysseus saw her; for to few

Of mortal birth the gods reveal themselves.

But the dogs knew her coming, and with whine

And whimpering crouched aloof.

#pallas athena#art#briton riviere#briton rivière#dogs#dog#animals#animal#goddess#ithaca#herdsman#greek mythology#the odyssey#odyssey#homer#odysseus#mythology#british#athena#shepherd#minerva#ancient greece#ancient greek#europe#european#classical antiquity#disguised

142 notes

·

View notes

Text

like i get all the mutuals who said theyd put me in ancient rome bc im interested (understatement) in the era but like. id love to visit it but id never want to actually live there. the smells would be too much. the people sound insane, etc. id love to visit there, see the views, meet the people, experience the setting for a little bit and see what its all about, but id rather die than actually live there for a long period of time. its like england.

#blorbo from my degree....#yes ik ancient romans wouldve killed me for comparing them to britons but sti

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

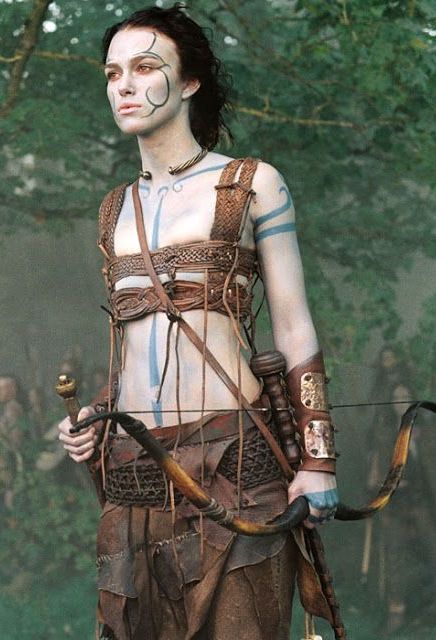

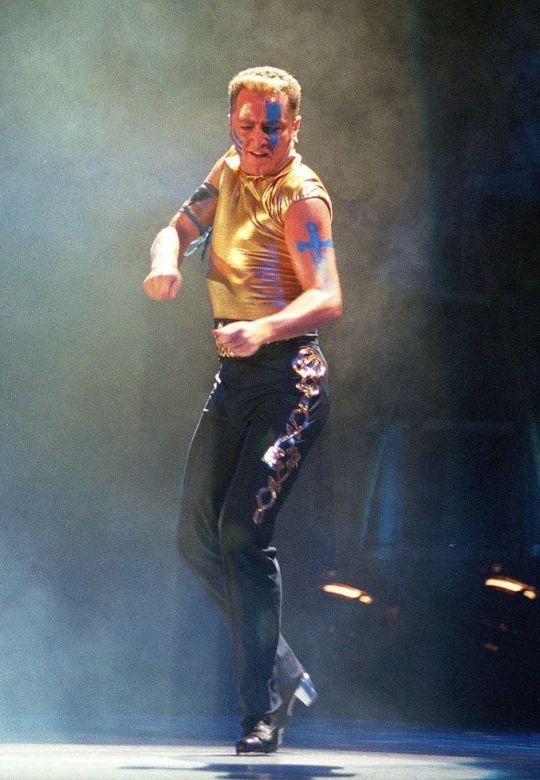

Should this Celt be blue?

An irish-dress-history game.

I've been researching the actual historical evidence behind the idea that ancient Insular Celts painted or tattooed themselves blue, and I thought it would be fun to make a game out of it. Below are various depictions of this idea along with the culture and date they are supposed to be depicting. The game is to guess whether each use of body paint or tattoos is supported by actual historical evidence. Answers are in the image descriptions.

(Note: This game is not intended to mock or criticize the artists and costume designers of any of these works. Good information on this topic is hard to find, and movie creators and artists frequently have goals other than historical accuracy. I am mocking Mel Gibson though, because f*** that guy.)

1 A 'Woad' (ie Pict) from 5th c. Britain. 2. Tattooed Irish warrior in 1170

3. A Medieval Scottish lord 4. Iceni Queen Boudica c. 60 CE

5. Ancient? Ireland 6. Britons during the time of Julius Cesar

7. Picts in 149 CE 8. Scots in 1297

Bibliography:

Hoecherl, M. (2016). Controlling Colours: Function and Meaning of Colour in the British Iron Age. Archaeopress Publishing LTD, Oxford. https://www.google.com/books/edition/Controlling_Colours/WRteEAAAQBAJ?hl=en&gbpv=0

MacQuarrie, Charles. (1997). Insular Celtic tattooing: History, myth and metaphor. Etudes Celtiques, 33, 159-189. https://doi.org/10.3406/ecelt.1997.2117

#iron age#roman era#early medieval#ancient celts#celtic#pict#tattoos#body painting#medieval#insular celts#gaelic irish#Hoecherl#brittonic celts#britons#gaels#scots

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Luck, Mischief & the Truth About Leprechauns

A Wild Elf’s Guide to Saint Patrick’s Day: Ah, mortals and their fondness for grand celebrations! Once again, the land is turning green, the taverns overflow with frothy beverages, and mortals prance about in their finest shamrock-clad attire. But what is Saint Patrick’s Day really about? Allow me, Runa, your well known and adored elderly Wild Elf with far too many centuries of experience (and…

#adventurer#Alrunia Ahn#Alrunia Ahn Art#ancient customs#beer#briton#celebration#celenration#Celtic myths#Christianity#Fae#folklore#fortune#four-leaf clover#gold#good luck charms#Green#history#Holy Trinity#illusions#imp#ireland#Irish#irish fae#Irish traditions#ko-fi shop#Leprechaun#leprechauns#luck#Mischief

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Our Vinecone. I had to work from three reference pics for this but yes, this is Firmus Piett had he lived in the Roman Empire in the first century.

(Yes I found Ken Colley with a beard from a Shakespeare production 😉)

Roman General Veers is next!

#firmus piett#admiral piett#star wars#star wars original trilogy#star wars au#Star Wars Roman au#Roman au#Piett as an ancient Briton#my illustration#drawing#digital art#illustrating stories

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

Various art shit, you’re welcome babes ❤️

1) Im a sucker for demon Vene rather than angel Vene, also obvious good omens inspired lmao

2) I looooooove the idea of Germany having a mini schnauzer! I did a poll on my other blog and the name Pretzel won! I based her personality on the mini schnauzer I had, Sir Lewis. Talkative, very loyal, a massive cuddler, abandonment and anxiety issues. I think Germany adopted her from a (verified) show dog breeder for the purpose of going on different kinds of hunts with him and Prussia, but in the long run it didn’t work out because Germany may have neglected to train her properly and spoiled her far more than he meant to. So her job is exactly like the other three dogs; a cuddly lap dog.

3) Not many notes here. Just transmasc Romano and I think Romano got a perm in the past as an attempt to bring back his once VERY curly hair because he honestly missed it. He gave up in the 90s lol

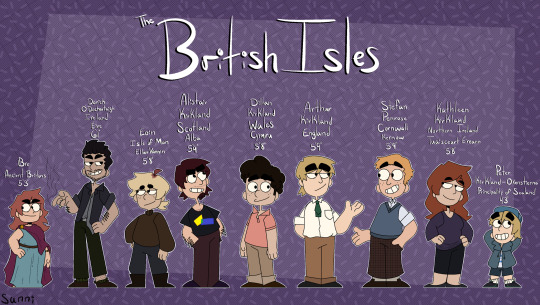

4) Redrew the old line up for the British Isles family! Very slight redesigns too! I think the canon uk bros designs are nice but also idc, I’ll draw these uk bros all the time instead 👀

#hetalia#hetalia fanart#hetalia ocs#hetalia headcanons#hws romano#hws south italy#hws veneziano#hws north italy#hws germany#hws england#hws british isles#hws ancient britons#hws ireland#hws northern ireland#hws cornwall#hws wales#hws scotland#hws isle of man#hws sealand

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Northern Britain: Coel Hen is a familiar figure in many ancient Welsh genealogies, with most of the kings of the north of Britain being able to trace their descent from him.

#historyfiles#history#Post-Roman#Romano-Britons#britain#ancient welsh#welsh#Coel Hen#Old King Cole#kings#genealogies#descent

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

We know next to nothing about the gods and goddesses of the Celts. Unlike the Greeks and Romans, the Celts had no single pantheon or divine ‘family’ of deities. Gods were apparently specific to particular tribes, or were connected to important features in the landscape, such as a river, spring, forest or mountain. The association of gods with watery places may explain why so many examples of high-status Celtic metalwork have been found in the rivers, streams, lakes and bogs of Britain. Communication with the gods, and control over the sacrifices made to them, was in the hands of a class of priests and priestesses that the Romans called druids. Sadly nothing is really known about the nature of the druids and what their precise role was in Celtic society.

Some British gods were combined with their classical equivalent when Celtic lands were conquered by the pragmatic and deeply superstitious Roman empire. The Romans were only too keen to combine their gods and goddesses with native ones in order to keep the natives happy. Hence we hear of the goddess Sulis, Celtic deity of the hot springs at Bath, who was merged with Minerva, the Roman goddess of healing, in order to create the super-deity ‘Sulis-Minerva’. Elsewhere we find examples of the merging together of Celtic and Roman war gods like ‘Mars-Toutatis’ or ‘Mars-Camulos’.

— The Celts: Who Were They, Where Did They Live, & What Happened After The Romans Left Britain?

#miles russell#the celts: who were they where did they live & what happened after the romans left britain?#history#classics#religion#celtic mythology#roman mythology#iron age#celts#celtic britons#britain#ancient rome#sulis#toutatis#camulus

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Forgot I never shared this experience 😅. As y'all know I express Finding out the hidden black history of all lands & also that genealogy is key👌🏿. Regarding the latter normally I generally search American bloodlines but Years ago I told myself I would eventually try one of the few European lineages I knew. We all know American History so there wasn't a conflict of how I would be related to anything in that line. With that said I eventually did so around the beginning of this yr and found most of Europe Royalty+ other lands were apart of that European lineage 😳. Now with me already having researched and read books about the Hidden Black History of Europe I knew that a lot of em were secretly Black/Moorish . My book collection above shows different sources I used to mentally pair info like the Castles & The black Rulership during different periods. As I always say Genealogy I think will provide a better connection in teaching Black folks once again to reclaim their history. If they don't feel a connection then their simply will be no want nor need to reconnect with the lost history. Whether it be concerning Ancestry from Europe, Asia, Africa or America 👍🏿

* Ignore the # with grandparents because if you know European royal genealogy then you know they intermixed Constantly 😫. Charlemagne, King Alfred etc all are grandparents at least 20x -100x 😭

The first statement is definitely true as I've shown many times.. This in contrast to the last pic where after they whitewashed us out of history they would symbolize us by being devils instead which is the opposite of how black in Europe use to be viewed

#black history#aboriginal#african history#muurs#black history month#black history 365#black European#afro british#black culture#black Twitter#occult#hidden history#muurish#moorish history#moors of europe#tartary#Tartaria#people of color in medieval art#genealogy#ancient and modern britons#black royalty

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

“All of our individuals were included in a project based at the Natural History Museum in London, which aimed to establish and interpret information about our European ancestors from ancient DNA. The same team of scientists released results of research to the public in 2018 about ‘Cheddar Man’, a ten thousand year old modern human from the Mesolithic Period, whose ancient DNA demonstrated that he was dark skinned.

While DNA could not be retrieved from Whitehawk Woman, the ‘Cheddar Man’ team advised that she would probably have had dark skin of a southern Mediterranean/Near Eastern/North African colour, brown hair and brown eyes. This is based on the genetic analysis of ancient individuals dating to the Neolithic from around Europe as well as from Britain specifically. This information was passed on to our forensic artist who included it within the facial reconstruction on display in the new gallery.

The same analysis produced predictions of lighter skin for other individuals included in the gallery and these predictions were also included in their facial reconstructions.”

1 note

·

View note

Text

Posted about British colonial officials in 1860s South India being fascinated by studying geology of Deccan Plateau as both a potential source of material wealth but also as more like intellectual curiosity that allowed them to consider "deep time" and the place of "civilization" in history. And someone shared post, commenting in tags something sort of like "interesting how British Empire could be so focused on rocks."

And really:

Both British imperial power and British popular imagination are tied to "ancient rocks"

British coal and coal-powered engines transformed global ecologies and societies with railroads and factories at the same time that British public became widely aware of dinosaurs, extinct Pleistocene megafauna, the vast scale of deep time, geology, and uniformitarian Earth systems. Then British anthropology, Egyptomania, archaeology, etc., were implicated in professionalization of sciences and ideas of primitivsm/racial hierarchy. Then British extraction of liquid fossil fuels instantiated expansion of petroleum products. Victorian popular culture had a penchant for contemplating death, decay, deep past, civilizational collapse, classical antiquity. So there's a simultaneous fixation on both temporality and materiality. Which both involve "earth."

-

Consider:

Coal. How the mining of "ancient rock" (300-million-year-old Carboniferous) and coal-burning probably strongly propelled Britain (tied also to enclosure laws and Caribbean slave profits reinvested in ascendant financial/insurance institutions) to the "first" industrialization around 1830, helping cement its global hegemony and setting a blueprint for European/US industry. How burning that ancient rock "unlocked steam power" for Britain and facilitated the rapid expansion of railroad networks after the first public steam railway in 1825 (steam engines then let Britain reach and extract resources from hinterlands) while the rock also powered textile mills after the 1830s (putting poorer Britons to work in mills and factories while "Poor Laws" were put into effect outlawing "vagrancy" and "joblessness") which reshaped "the countryside" in Britain and reshaped global ecologies and labor regimes. Provincial realist novels and other literature reflect anxiety about this ecological/social transition. Even later Victorian novels and fin de siecle commentaries hint how coal and industrialization invoke temporality more directly, in that the engines and technologies provoke rhetoric and discourses about exponential growth, linear progress, and dazzling future horizons.

Fossils of Pleistocene megafauna: How an extinct Mastodon was displayed at Pall Mall in London in 1802. And how William Conybeare's discovery/description of coal-bearing rock in Britain led him to name "the Carboniferous period" in 1822, but it wasn't just coal power that this event inspired. in the very same year, Conybeare described the remains of extinct Pleistocene hyenas at Kirkdale Cave in Britain. The promotion of this discovery of Ice Age hyenas gave many Britons for the first time an awareness of deep past and obsession with Creatures. But the promotion also brought spectacle, public display, poetics, and marketing into natural history like "edu-tainment," a "poetics of popular science." This took place in the context of the rapid rise of British mass-market print media. Geological verse, Victorian novels, and cheap miscellanies reflect anxiety about this temporality and natural history.

Geology as a discipline: How the 1830 publishing of Lyell's monumentally significant Principles of Geology, directly inspired after he observed British ancient rock formations at Isle of Arran, completely changed European/US understanding of deep time and geology and the scale of Earth systems (uniformity principle), which made people wonder about linear notions of history and whether empires/societies can survive forever in such vast time scales.

Dinosaur fossils: How the "first dinosaur sculptures in the world" (dinosaur fossils reminiscent of ancient rock?) were reconstructed and put on display by Britain in 1854 at Crystal Palace in London following "the Great Exhibition," an event which set the model for future exhibitions and started the global craze for "world's fairs" and expositions showcasing imperial/industrial power for decades (the model for Chicago's Columbian Exposition of 1893, Paris event of 1900, St. Louis event of 1904, and beyond).

Soil mapping: How "ancient rock" was entangled with one of the most significant scientific projects of all-time, Britain's "The Great Trigonometric Survey of India" in 1802, undertaken to survey and record soil types across South Asia. After the resistance of the leaders of Mysore had finally been defeated, the subcontinent was vulnerable to consolidated British colonial power, and surveys were ordered immediately. The mapping of acreage for tax administration by the East India Company would remake societies with bordered property, contracted ownership, tax/wealth extraction. But the Survey also let Britain map soil for purposes of monoculture agriculture planning. Britain then used geology/soil as potential indicators of biological essentialism that equated "ancient" Gonds of India or "ancient" Aboriginal peoples of Australia with primitivism. Adventure stories and sportsmen's pulp magazines reflect anxiety about these cultural and geographical frontiers.

Diamonds: How the discovery of ancient rock (diamonds, from tens of millions of years old kimberlite) in the Kimberly (South Africa) rocketed Britain to more power when their colonial commissioners took possession in 1871, giving Britain a foothold and paving the way for Cecil Rhodes to amass astonishing wealth while completely remaking social institutions, labor regimes, and environments in southern Africa, giving Britain so much profit from diamonds that in 1882 Kimberly was only the second city on the whole planet to install electric street lighting.

Egyptomania: How British archaeologists digging around in ancient rock of their vassal/colony of Egypt, especially the tens of thousands of ancient Egyptian artifacts that they collected between 1880 and 1890, contributed to a craze for classical antiquity and a fixation on the ancient Mediterranean and mummies.

Victorian death fascination: How British archaeologists interacting with ancient rock in Southwest Asia (Mesopotamia, Levant) coupled with the Egyptomania also strongly influenced Late Victorian obsessions with death, decay, the occult, millennarian dates, and civilizational collapse which continued to influence culture, fashion, historicity, and narrativizing in Europe/US for years. Perhaps they wondered: "If Ur could fall, if Thebes could fall, if Mycenae could fall, if ROME could fall, then how could our civilization based in fair London survive such vast eons of time and such strong geological and environmental forces?"

Liquid fossil fuels: How "ancient rock" yielded liquid fossil that was extracted by British industrialsits when the first test oil wells were dug at "the Black Spot" in Borneo in 1896 which led to creation of Shell Oil company in 1897 led by a British director who was fascinated with ancient fossils. Followed then the global expansion of combustion engines, oil lubricants, and networks of imperial infrastructure to extract and refine oil. And how British tinkering with "ancient rock" of Persia and Southwest Asia led to the bolstering of a "Middle East" oil industry; the Anglo-Persian Oil Company was founded in 1909, giving Britain yet more geopolitical leverage in the region; the company would later become BP, one of the biggest and most profitable corporations to ever exist.

-

So the immaterial imaginaries of place/space and time (frontiers, the exotic/foreign, the tropical/Orient, ascent/decay, civilization/savagery, deep past/future horizons) justify or organize or pre-empt or service the material dispossession and accumulation.

British Empire transformed Earth and earth. Both materially/physically and immaterially/imaginatively.

382 notes

·

View notes

Text

Greetings! This is a blog meant for discussions about Greek mythology and the Ancient Greek Gods! All are welcome, even if you have limited knowledge of Greek mythology/lore

- DMs are accepted, ONLY related to Greek mythology

- Be kind and respectful

- 16+ recommended

- Have fun discussing!

(Painting above is not mine, it is ‘Circe And Her Swine’ by Briton Rivière)

#greek tumblr#greek mythology#greek gods#Epic#epic the circe saga#circe#hellenism#hellenic polytheism

188 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Hadrian's Wall

Hadrian's Wall (known in antiquity as the Vallum Hadriani or the Vallum Aelian) is a defensive frontier work in northern Britain which dates from 122 CE. The wall ran from coast to coast at a length of 73 statute miles (120 km). Though the wall is commonly thought to have been built to mark the boundary line between Britain and Scotland, this is not so; no one knows the actual motivation behind its construction but it does not delineate a boundary between two countries.

While the wall did simply mark the northern boundary of the Roman Empire in Britain at the time, theories regarding the purpose of such a massive building project range from limiting immigration, to controlling smuggling, to keeping the indigenous people at bay north of the wall. The wall continued in use until it was abandoned in the early 5th century CE.

Purpose

The military effectiveness of the wall has been questioned by many scholars over the years owing to its length and the positioning of the fortifications along the route. The argument goes that, had the wall actually been built as a defensive barrier, it would have been constructed differently and at another location. Regarding this, Professors Scarre and Fagan write,

Archaeologists and historians have long debated whether Hadrian's Wall was an effective military barrier…Whatever its military effectiveness, however, it was clearly a powerful symbol of Roman military might. The biographer of Hadrian remarks that the emperor built the wall to separate the Romans from the barbarians. In the same way, the Chinese emperors built the Great Wall to separate China from the barbarous steppe peoples to the north. In both cases, in addition to any military function, the physical barriers served in the eyes of their builders to reinforce the conceptual divide between civilized and noncivilized. They were part of the ideology of empire. (Ancient Civilizations, 313)

This seems to be the best explanation for the underlying motive behind the construction of Hadrian's Wall. The Romans had been dealing with uprisings in Britain since their conquest of the region. Although Rome's first contact with Britain was through Julius Caesar's expeditions there in 55/54 BCE, Rome did not begin any systematic conquest until the year 43 CE under the Emperor Claudius (r. 41-54 CE).

The revolt of Boudicca of the Iceni in 60/61 CE resulted in the massacre of many Roman citizens and the destruction of major cities (among them, Londinium, modern London) and, according to the historian Tacitus (56-117 CE), fully demonstrated the barbaric ways of the Britons to the Roman mind.

Boudicca's forces were defeated at The Battle of Watling Street by General Gaius Suetonius Paulinus in 61 CE. At the Battle of Mons Graupius, in the region which is now Scotland, the Roman General Gnaeus Julius Agricola won a decisive victory over the Caledonians under Calgacus in 83 CE. Both of these engagements, as well as the uprising in the north in 119 CE (suppressed by the Roman governor and general Quintus Pompeius Falco), substantiated that the Romans were up to the task of managing the indigenous people of Britain.

The suggestion that Hadrian's Wall, then, was built to hold back or somehow control the people of the north does not seem as likely as that it was constructed as a show of force. Hadrian's foreign policy was consistently “peace through strength” and the wall would have been an impressive illustration of that principle. In the same way that Julius Caesar built his famous bridge across the Rhine in 55 BCE simply to show that he, and therefore Rome, could go anywhere and do anything, Hadrian perhaps had his wall constructed for precisely the same purpose.

Continue reading...

213 notes

·

View notes

Text

Northern & Southern European Dyes Palette(s)

It's been almost exactly two years since I made my Iron Age Palette. To celebrate that anniversary... No, you know what, actually not, it's a total coincidence 😅 I was working on a new thing and started wondering about this and that; to not bore you with the details, let's just say that one thing let to another and of course I ended up revisiting the very basics. So here it is! Not one, but TWO new colour palettes for our oldtime-y sims. Based on the lives of my Britons at some point in 1st century CE, shortly before the Roman conquest.

An important note: the southern palette is actually rather an add-on than a separate palette. As in, Romans would surely have access to the dyes from the northern palette as well. But as stated above, I made this whole thing from the viewpoint of a British Celt, hence we have two palettes: one with dyes which he could just obtain from native plants and the other with those he'd have to import. The southerners were more blessed in this aspect :]

You can download PDF files for both of those palettes and .txt files to be used in Paint.net (put them in Documents\paint.net User Files\Palettes). EDIT: the amazing @kyrassimhoard went ahead and made the .aco version of the palettes for all the Photoshop users! Thank you so much Kyra (also, special thanks to @aheathen-conceivably for double checking them for me 💗)

DOWNLOAD them on my Patreon! (always free, no early access etc.)

Apart from a bunch of visual changes (maybe the font will actually be readable this time? Gasp!), there's some new stuff in the palettes themselves (duh). Let's take a quick look, shall we?

undyed wool - hard to call it a dye, lol, but ofc it had to be here. The so-called primitive sheep of the Brittonic era looked quite different from what we imagine when we think 'sheep', and they most certainly came not only in white, but also in many shades of brown or even black. Perfect for making a colourful garment even without any dyes;

birch leaves - easy to obtain, easy to dye; almost no changes here, other than one added shade which used to be under 'mixed ingredients' before;

birch bark - OK, I don't remember where I took the old colours from, but I'm afraid I was being too optimistic. Birch bark gives rather pinkish than reddish shades; actually, it needs a looooooong soak and proper pH to turn anything but very bright, subtle pink. But it seems you can get them and they don't wash out that easily, so - there you go;

elderberry - here I was for sure being too optimistic, especially with that one pretty, saturated blue shade which got thrown away. From what I've read (and seen in photos...), elderberry is a very tricky dye, not particularly water- and lightfast. 'Not particularly' is mildly put - it just washes out in no time, leaving you either with a very pale or very greyish shade of the once vibrant colour. Adjusted accordingly (and they're still too pretty tbh);

apple leaves/twigs - that's a bit of a tricky point, because the Internet claims it was only Romans who brought apples to Britain. But at the same time apple cider was Britain's national drink allegedly already during the Celtic times. Heck, Welsh mythical island of Avalon literally means 'isle of apples', and mythology tends to be... you know... old. Huh? After a bit of research on the topic I'm inclined to believe that what Romans really brought with them were big, sweet apples and their organised cultivation; but small, tart, 'untasty' varieties did exist in Britain even before, growing in the wild. Perfect for making cider - or dyes 😉;

nettle - no changes here. Easy, cheap, grows everywhere, just that the colours are probably not something you'd wear to a party;

hedge bedstraw - seems it's growing everywhere in Britain, so it's plausible the ancients would've made use of it;

lichen - aaaaalriiight, now, that is a big discovery! Beautiful shades and absolutely possible to obtain from the varieties growing on the British Isles. One of the most crucial omissions from my old palette, here finally in its full glory.

That was it for the northern palette. And the southern? Glad you asked:

weld - previously called 'dyer's rocket', but no one in the whole wide natural dyeing Internet calls it that. Beautiful, vibrant, very steady yellow; won't give away even if you overdye it with indigo or woad. It's native to the Mediterranean and while it was cultivated in Britain in later centuries, I have no reason to believe that was also the case in 1 c. CE. I dub it imported;

madder - I keep reading that it's giving saturated red shades, but I have yet to see anyone dye a skein of yarn deep red with madder only. All that keeps popping up in pictures are gentle, pinkish reds, so that's what I included in my palette too. The orange comes from changed pH of the water;

woad - OK, that's my most epic fail of all. To make a Celtic palette and not include woad?! Putting aside the whole matter of Britons possibly maybe but actually maybe not using it to paint their faces (a very controversial matter, let's not go there 😅), woad was the blue dye in those times. Indigo was far away and while it was being imported to Rome, afaik it was used mostly for painting, not cloth dyeing; and besides, as crazy as it may sound, woad seems to do the job better. Seriously. Higher water and light fastness. The question is, was it cultivated in Britain or imported? Just like weld, it's native to the Mediterraean. There is a British find of a bunch of woad seeds, from 1 c. BCE - but then again, it's just one find. So... Mostly imported but slowly being introduced to the Isles? Maybe?

mixed ingredients - the ingredients specified in the PDFs are given in the order they're used - that makes a difference! My biggest discovery of this whole natural dyeing research is that, surprisingly, vibrant green is the absolutely most difficult colour to obtain. That dark green you see at the bottom - so-called Lincoln green - requires super high levels of both weld and woad, and you must put your yellow skein in the blue dye asap - if you're too slow, you get a lighter shade, e.g. like the one above it. The Hightowers surely knew how to show they're rich, huh...?

and last but not least, the luxury dyes! Some imported from far away (turmeric), some from nearby lands (Tyrian purple), some even grown locally (there were saffron plantations on Sicily. True story), but nevertheless, all super duper expensive. Tyrian purple was actually legally reserved for the emperor only - even if you could, by some miracle, afford it, you'd probably get arrested if you dared to dress in that particular shade of purple. Good that lichens could always come to the rescue!

Guess that's enough of behind-the-scenes trivia, isn't it? Props to you if you managed to get to this point, lol. Have fun with the palettes and happy recolouring!

***

Sources:

dzikiebarwy.com - in Polish, but the pictures should speak for themselves. Here you've got a post about dyeing with summer plants, including birch leaves, here - elderberry, here - apple leaves and twigs, here - nettle;

https://woolandpalette.com/blogs/news/making-vibrant-green-with-natural-dyes was my first step in finding out how to obtain a proper green shade with natural dyes;

wooltribulations.blogspot.com - dyeing with birch bark (here), another failed elderberry experiment (here) and overdyeing weld with woad for a deep Lincoln green shade (here);

www.jennydean.co.uk - an absolute godsend, especially two posts: 'Dyes of the Celts' (here) and 'Colours of the Romans' (here);

https://craftinvaders.co.uk/making-dye-from-lichen/

https://earlychurchhistory.org/fashion/colors-dyes-for-clothing-in-ancient-rome/ - on the posh dyes for the rich;

https://www.butserancientfarm.co.uk/gallery - except for the general vibe (*chef's kiss*), the 'animals and nature' section of the gallery has pictures of the 'primitive' sheep which they keep at the farm;

...and a bunch of others which I didn't save in my bookmarks 🙃

53 notes

·

View notes