#brittonic celts

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

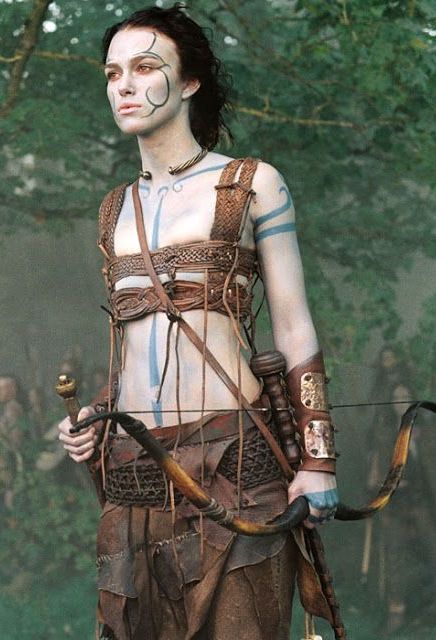

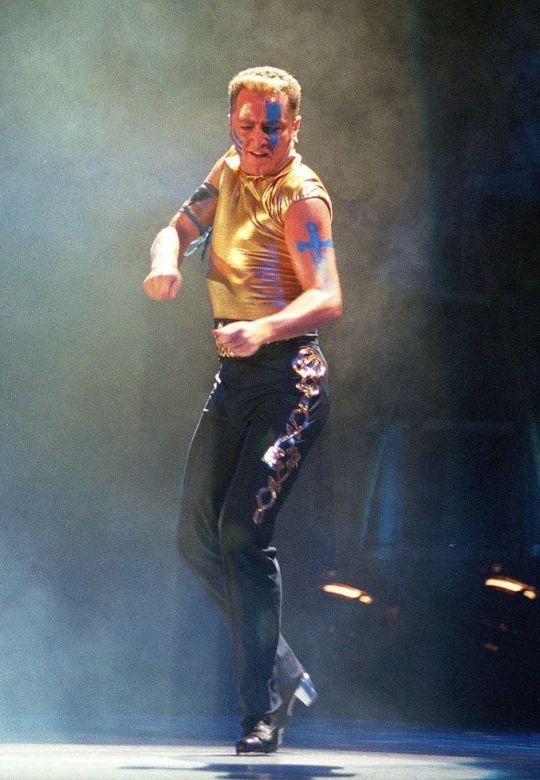

Should this Celt be blue?

An irish-dress-history game.

I've been researching the actual historical evidence behind the idea that ancient Insular Celts painted or tattooed themselves blue, and I thought it would be fun to make a game out of it. Below are various depictions of this idea along with the culture and date they are supposed to be depicting. The game is to guess whether each use of body paint or tattoos is supported by actual historical evidence. Answers are in the image descriptions.

(Note: This game is not intended to mock or criticize the artists and costume designers of any of these works. Good information on this topic is hard to find, and movie creators and artists frequently have goals other than historical accuracy. I am mocking Mel Gibson though, because f*** that guy.)

1 A 'Woad' (ie Pict) from 5th c. Britain. 2. Tattooed Irish warrior in 1170

3. A Medieval Scottish lord 4. Iceni Queen Boudica c. 60 CE

5. Ancient? Ireland 6. Britons during the time of Julius Cesar

7. Picts in 149 CE 8. Scots in 1297

Bibliography:

Hoecherl, M. (2016). Controlling Colours: Function and Meaning of Colour in the British Iron Age. Archaeopress Publishing LTD, Oxford. https://www.google.com/books/edition/Controlling_Colours/WRteEAAAQBAJ?hl=en&gbpv=0

MacQuarrie, Charles. (1997). Insular Celtic tattooing: History, myth and metaphor. Etudes Celtiques, 33, 159-189. https://doi.org/10.3406/ecelt.1997.2117

#iron age#roman era#early medieval#ancient celts#celtic#pict#tattoos#body painting#medieval#insular celts#gaelic irish#Hoecherl#brittonic celts#britons#gaels#scots

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Happy Saint Davids guys

Saint David’s Day!

Today (March 1st) is Saint David’s day in Wales. Saint David’s day is celebrated all across Wales and is a big day of celebration of our culture

Why is Saint David’s day celebrated?

Saint David’s day is, as the name may suggest, a celebration of the life of Saint David. He was the patron saint of Wales and was very important when it comes to the religious aspects of Welsh culture (obviously, only relating to our later Christianity, and not our earlier other religions sadly). He died on March 1st in the year 589 and so Saint David’s day begun as a commemmoration of his life and work. Nowadays, Saint David’s day within the Welsh community is celebrated more as a day of pride and love based around our nation and our people. It has become a day of great pride in our Welsh traditions, much like how Saint Patrick’s day has become for the Irish.

Below is the flag of St David, which is typically flown on St David’s day

How do you celebrate Saint David’s day?

This depends on the person and area, and how patriotic you’re wanting to be. A vast majority of people will celebrate by either wearing leeks or daffodils and/or by displaying one or both of these in their homes. This is because both the leek and the daffodil are national emblems of Wales.

Most primary schools and some secondary/comprehensive schools will also run a school eisteddfod, which is a celebration of Welsh culture and arts through the form of a competition. These can sometimes include students learning traditional dances or music in order to perform them to the rest of the school. Often times, the young girls will also have to dress up in traditional-wear costumes (that tend to be awfully itchy, I must add). Students will also typically all be asked to sing the national anthem. People often also partake in enjoying traditional Welsh foods, such as cawl or picau ar y maen (AKA Welsh cakes or the several other names that these go by), which are shown below.

There are also often parades in order to celebrate, especially in Cardiff city centre on St David’s day. These parades come along with flying the flag of Wales and the flag of St David, as well as many banners, costumes, colours and excitement. You may also be able to spot the red and yellow lions flag flying, which is representative of the Welsh princes. It is also very common, especially at the parades in Cardiff, to hear the national anthem sung by the crowds. National museums across Wales also tend to throw big events in order to celebrate the day, which have the added bonus of being packed with fascinating history about Wales!

Below is an image of some of the types of traditional clothing Welsh women would wear, which young female students in Wales might be asked to wear in order to celebrate Saint David’s day

Below is a picture of a Saint David’s day parade in Cardiff

I hope this could be an informative insight in to what Saint David’s day is and why us Welsh lot even celebrate it to begin with!

Have a wonderful day, whether or not you celebrate St David’s day! Dydd Dewi Sant hapus iawn, pawb. Cymru am byth

#wales#welsh#Cymru#cymraeg#st davids day#saint david#saint davids day#tradition#culture#celebration#celtic#celts#brythonic#brittonic

131 notes

·

View notes

Text

Northern & Southern European Dyes Palette(s)

It's been almost exactly two years since I made my Iron Age Palette. To celebrate that anniversary... No, you know what, actually not, it's a total coincidence 😅 I was working on a new thing and started wondering about this and that; to not bore you with the details, let's just say that one thing let to another and of course I ended up revisiting the very basics. So here it is! Not one, but TWO new colour palettes for our oldtime-y sims. Based on the lives of my Britons at some point in 1st century CE, shortly before the Roman conquest.

An important note: the southern palette is actually rather an add-on than a separate palette. As in, Romans would surely have access to the dyes from the northern palette as well. But as stated above, I made this whole thing from the viewpoint of a British Celt, hence we have two palettes: one with dyes which he could just obtain from native plants and the other with those he'd have to import. The southerners were more blessed in this aspect :]

You can download PDF files for both of those palettes and .txt files to be used in Paint.net (put them in Documents\paint.net User Files\Palettes). If anyone wants to help me out and make them useable in Photoshop too, please go ahead!

DOWNLOAD them on my Patreon! (always free, no early access etc.)

Apart from a bunch of visual changes (maybe the font will actually be readable this time? Gasp!), there's some new stuff in the palettes themselves (duh). Let's take a quick look, shall we?

undyed wool - hard to call it a dye, lol, but ofc it had to be here. The so-called primitive sheep of the Brittonic era looked quite different from what we imagine when we think 'sheep', and they most certainly came not only in white, but also in many shades of brown or even black. Perfect for making a colourful garment even without any dyes;

birch leaves - easy to obtain, easy to dye; almost no changes here, other than one added shade which used to be under 'mixed ingredients' before;

birch bark - OK, I don't remember where I took the old colours from, but I'm afraid I was being too optimistic. Birch bark gives rather pinkish than reddish shades; actually, it needs a looooooong soak and proper pH to turn anything but very bright, subtle pink. But it seems you can get them and they don't wash out that easily, so - there you go;

elderberry - here I was for sure being too optimistic, especially with that one pretty, saturated blue shade which got thrown away. From what I've read (and seen in photos...), elderberry is a very tricky dye, not particularly water- and lightfast. 'Not particularly' is mildly put - it just washes out in no time, leaving you either with a very pale or very greyish shade of the once vibrant colour. Adjusted accordingly (and they're still too pretty tbh);

apple leaves/twigs - that's a bit of a tricky point, because the Internet claims it was only Romans who brought apples to Britain. But at the same time apple cider was Britain's national drink allegedly already during the Celtic times. Heck, Welsh mythical island of Avalon literally means 'isle of apples', and mythology tends to be... you know... old. Huh? After a bit of research on the topic I'm inclined to believe that what Romans really brought with them were big, sweet apples and their organised cultivation; but small, tart, 'untasty' varieties did exist in Britain even before, growing in the wild. Perfect for making cider - or dyes 😉;

nettle - no changes here. Easy, cheap, grows everywhere, just that the colours are probably not something you'd wear to a party;

hedge bedstraw - seems it's growing everywhere in Britain, so it's plausible the ancients would've made use of it;

lichen - aaaaalriiight, now, that is a big discovery! Beautiful shades and absolutely possible to obtain from the varieties growing on the British Isles. One of the most crucial omissions from my old palette, here finally in its full glory.

That was it for the northern palette. And the southern? Glad you asked:

weld - previously called 'dyer's rocket', but no one in the whole wide natural dyeing Internet calls it that. Beautiful, vibrant, very steady yellow; won't give away even if you overdye it with indigo or woad. It's native to the Mediterranean and while it was cultivated in Britain in later centuries, I have no reason to believe that was also the case in 1 c. CE. I dub it imported;

madder - I keep reading that it's giving saturated red shades, but I have yet to see anyone dye a skein of yarn deep red with madder only. All that keeps popping up in pictures are gentle, pinkish reds, so that's what I included in my palette too. The orange comes from changed pH of the water;

woad - OK, that's my most epic fail of all. To make a Celtic palette and not include woad?! Putting aside the whole matter of Britons possibly maybe but actually maybe not using it to paint their faces (a very controversial matter, let's not go there 😅), woad was the blue dye in those times. Indigo was far away and while it was being imported to Rome, afaik it was used mostly for painting, not cloth dyeing; and besides, as crazy as it may sound, woad seems to do the job better. Seriously. Higher water and light fastness. The question is, was it cultivated in Britain or imported? Just like weld, it's native to the Mediterraean. There is a British find of a bunch of woad seeds, from 1 c. BCE - but then again, it's just one find. So... Mostly imported but slowly being introduced to the Isles? Maybe?

mixed ingredients - the ingredients specified in the PDFs are given in the order they're used - that makes a difference! My biggest discovery of this whole natural dyeing research is that, surprisingly, vibrant green is the absolutely most difficult colour to obtain. That dark green you see at the bottom - so-called Lincoln green - requires super high levels of both weld and woad, and you must put your yellow skein in the blue dye asap - if you're too slow, you get a lighter shade, e.g. like the one above it. The Hightowers surely knew how to show they're rich, huh...?

and last but not least, the luxury dyes! Some imported from far away (turmeric), some from nearby lands (Tyrian purple), some even grown locally (there were saffron plantations on Sicily. True story), but nevertheless, all super duper expensive. Tyrian purple was actually legally reserved for the emperor only - even if you could, by some miracle, afford it, you'd probably get arrested if you dared to dress in that particular shade of purple. Good that lichens could always come to the rescue!

Guess that's enough of behind-the-scenes trivia, isn't it? Props to you if you managed to get to this point, lol. Have fun with the palettes and happy recolouring!

***

Sources:

dzikiebarwy.com - in Polish, but the pictures should speak for themselves. Here you've got a post about dyeing with summer plants, including birch leaves, here - elderberry, here - apple leaves and twigs, here - nettle;

https://woolandpalette.com/blogs/news/making-vibrant-green-with-natural-dyes was my first step in finding out how to obtain a proper green shade with natural dyes;

wooltribulations.blogspot.com - dyeing with birch bark (here), another failed elderberry experiment (here) and overdyeing weld with woad for a deep Lincoln green shade (here);

www.jennydean.co.uk - an absolute godsend, especially two posts: 'Dyes of the Celts' (here) and 'Colours of the Romans' (here);

https://craftinvaders.co.uk/making-dye-from-lichen/

https://earlychurchhistory.org/fashion/colors-dyes-for-clothing-in-ancient-rome/ - on the posh dyes for the rich;

https://www.butserancientfarm.co.uk/gallery - except for the general vibe (*chef's kiss*), the 'animals and nature' section of the gallery has pictures of the 'primitive' sheep which they keep at the farm;

...and a bunch of others which I didn't save in my bookmarks 🙃

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

I personally don’t see the Kirkland brothers as biologically related at all. I think they’re more of a found family/adopted situation (which is supported by gangsta AU since they’re all from different families there) because while, they have cultural similarities and do have a lot of shared history, even outside of the uk, they are still all very distinct in their own rights. Scotland and Wales would be the only two that could make the most sense being biological brothers but still their Celtic tribes are too different and individual.

For an explanation on my understanding:

Scotland, Wales and Ireland are all Celtic by nature- England *isnt*. He’s almost entirely Germanic- plus the Viking shit and the Norman’s. So, England is no way in hell related to any of the others.

Ireland is Celtic BUT he’s an entirely different Celtic category from Scotland and Wales. Ireland is Gaelic while the other two (at first) aren’t. Scotland is likely more Pictish- a brittonic Celt group that fused with Gaelic groups migrating from Ireland to create Alba. The Picts were more culturally and linguistically similar to their welsh neighbors both being brittonic celts(although we have very little Pictish language for reference so). So, Ireland’s similarities with Wales and Scotland are minimal other than just generally being Celtic and removes him off the table.

This leaves Wales and Scotland. The only two who you could make an argument for being bio brothers.. but I’m still doing research on the differences and similarities between the welsh and the picts.

This post isn’t to like.. excuse incest shipping or anything btw- I still think shipping any of the uk brothers with eachother is nasty, even if they aren’t necessarily biologically related. It’s just something I’ve been thinking about as I develop my headcanons and storyline

And as always, if I get any information wrong, please feel free to correct me on anything!

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

hmm.

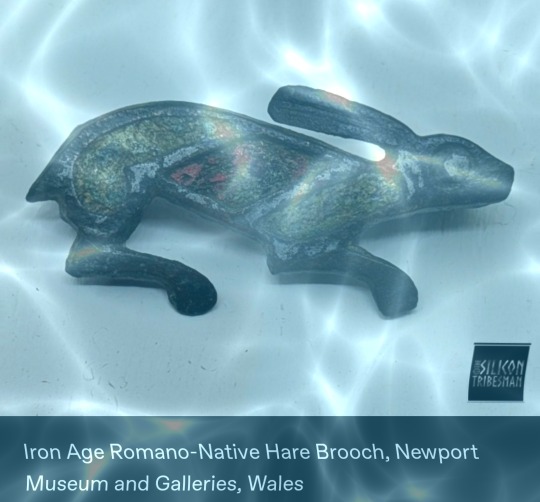

cw discussion of indigeneity related to these islands

Oh, we're calling things 'Romano-Native' now are we? Couldn't have gone for 'Brittonic' as an alternative to 'British'? Happy to give up the latter entirely to modern notions of imperialism and centralisation?

Apparently this is all the rage among museums and archaeologists working in Wales and Scotland, but it's giving unfortunate 'indigenous Celts' vibes for me. I am so deeply uncomfortable with this turn in Celtic nationalisms. Sounds like you'd rather reclaim some equivalent of blood quantum than the term British ffs. Tell me, how long did the descendants of Romans have to live here before they could be called 'native'? How many generations of mixed marriages? Oh, never? So we're also undermining all the work that's been done on, e.g., black British history to show that poc have been a part of the islands' history since at least the Roman times, because what this kind of Celtic nationalism is saying is that you can't be black and 'native'. That is one logical conclusion of this insidious notion of 'Celtic indigeneity'. It seems to me to go directly against the idea of diffusing and deweaponising history so that we can find a way forward together now, and instead wields it as a club that will undoubtedly feed into modern harms.

#the use of american definitions very much not helping matters here!!#but what do i know i had to be told the term 'hiberno-norse' was elitist the other day. i who have 0 latin.#anyway i don't like this. i don't like it at all.

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Arthurian myth: Morgan the Fey (1)

Loosely translated from the French article "Morgane", written by Philippe Walter, for the Dictionary of Feminine Myths (Le Dictionnaire des Mythes Féminins)

MORGANE

Morgane means in Celtic language “born from the sea” (mori-genos). This character is as such, by her origins, part of the numerous sea-creatures of mythologies. A Britton word of the 9th century, “mormorain”, means “maiden of the sea/ sea-virgin”, et in old texts it is equated with the Latin “siren”. A passage of the life of saint Tugdual of Tréguiers (written in 1060) tells of ow a young man of great beauty named Guengal was taken away under the sea by “women of the sea”. The Celtic beliefs knew many various water-fairies with often deadly embraces – and Morgane was one among the many sirens, mermaids, mary morgand and “morverc’h” (sea girls/daughters of the sea).

Morgane, the fairy of Arthurian tales, is the descendant of the mythical figures of the Mother-Goddesses who, for the Celts, embodied on one side sovereignty, royalty and war, and on the other fecundity and maternity. In the Middle-Ages, they were renamed “fairies” – but through this word it tried to translate a permanent power of metamorphosis and an unbreakable link to the Otherworld, as well as a dreaded ability to influence human fate. The French word “fée” comes from the neutral plural “fata”, itself from the Latin word “fatum”, meaning “fate”.

There is not a figure more ambivalent in Celtic mythology – and especially in the Arthurian legends – than Morgane. She constantly hesitates between the character of a good fairy who offers helpful gifts to those she protects ; and a terrible, bloodthirsty goddess out for revenge, only sowing death and destruction everywhere she goes. Christianity played a key role in the demonization of this figure embodying an inescapable fate, thus contradicting the Christian view of mankind’s free will.

I/ The sovereign goddess of war

It is in the ancient mythological Irish texts that the goddess later known as Morgane appears. The adventures of the warrior Cuchulainn (the “Irish Achilles”) with the war-goddess Morrigan are a major theme of the epic cycle of Ireland. The Morrigan (a name which probably means “great queen”) is also called “Bodb Catha” (the rook of battles). It is under the shape of a rook (among many other metamorphosis) that she appears to Cuchulainn to pronounce the magical words that will cause the hero’s death.

The Irish goddesses of war were in reality three sisters: Bodb, Macha and Morrigan, but it is very likely that these three names all designated the same divinity, a triple goddess rather than three distinct characters. This maleficent goddess was known to cause an epileptic fury among the warriors she wanted to cause the death of. The name of Bodb, which ended up meaning “rook”, originally had the sense of “fury” and “violence”, and it designated a goddess represented by a rook. The Irish texts explain that her sisters, Macha and Morrigan, were also known to cause the doom of entire armies by taking the shape of birds. Every great battle and every great massacre were preceded by their sinister cries, which usually announced the death of a prominent figure.

The Celtic goddesses of war have as such a function similar to the one of the Norse Walkyries, who flew over the battlefield in the shape of swans, or the Greek Keres. The deadly nature of these goddesses resides in the fact that they doom some warriors to madness with their terrifying screams. One of the effects of this goddess-caused madness was a “mad lunacy”, the “geltacht”, which affected as much the body as the mind. During a battle in 1722 it was said that the goddess appeared above king Ferhal in the shape of a sharp-beaked, red-mouth bird, and as she croaked nine men fell prey to madness. The poem of “Cath Finntragha” also tells of the defeat of a king suffering from this illness. The place of his curse later became a place of pilgrimage for all the lunatics in hope of healing.

The link between the war-goddess and the “lunacy-madness” are found back within folklore, in which fairies, in the shape of birds, regularly attack children and inflict them nervous illnesses. These fairies could also appear as “sickness-demons”. Their appearance was sometimes tied to key dates within the Celtic calendar, such as Halloween, which corresponded to the Irish and pre-Christian celebration of Samain. Folktales also keep this particularly by placing the ritualistic appearances of witches and of fate-fairies during the Twelve Days, between Christmas and the Epiphany – another period similar to the Celtic Halloween. Morgane seems to belong to this category of “seasonal visitors”.

II) The Queen of Avalon

In Arthurian literature, Morgane rules over the island of Avalon, a name which means the Island of Apples (the apple is called “aval” in Briton, “afal” in Welsh and “Apfel” in German). Just like the golden apples of the Garden of the Hesperids, in Celtic beliefs this fruit symbolizes immortality and belongs to the Otherworld, a land of eternal youth. It is also associated with revelations, magic and science – all the attributes that Morgane has. Her kingdom of Avalon is one of the possible localizations of the Celtic paradise – it is the place that the Irish called “sid”, the “sedos” (seat) of the gods, their dwelling, but at the same time a place of peace beyond the sea. Avalon is also called the Fortunate Isle (L’Île Fortunée) because of the miraculous prosperity of its soil where everything grows at an abnormal rate. As such, agriculture does not exist there since nature produces by itself everything, without the intervention of mankind.

It is within this island that the fairy leads those she protects, especially her half-brother Arthur after the twilight of the Arthurian world. Morgane acts as such as the mediator between the world of the living and the fabulous Celtic Otherworld. Like all the fairies, she never stops going back and forth between the two worlds. Morgane is the ideal ferrywoman. The same way the Morrigan fed on corpses or the Valkyries favored warriors dead in battle, Morgane also welcomes the soul of the dead that she keeps by her side for all of eternity. Some texts gave her a home called “Montgibel”, which is confused with the Italian Etna. The Otherworld over which she rules doesn’t seem, as such, to be fully maritime.

The ”Life of Merlin” of the Welsh clerk Geoffroy of Monmouth teaches us that Morgan has eight sisters: Moronoe, Mazoe, Gliten, Glitonea, Gliton, Thiten, Tytonoe, and Thiton. Nine sisters in total which can be divided in three groups of three, connected by one shared first letter (M, G, T). In Adam de la Halle’s “Jeu de la feuillée”, she appears with two female companions (Arsile and Maglore), forming a female trinity. As such, she rebuilds the primitive triad of the sovereign-goddesses, these mother-goddesses that the inscriptions of Antiquity called the “Matres” or “Matronae”. In this triad, Morgane is the most prominent member. She is the effective ruler of Avalon, since it was said that she taught the art of divination to her sisters, an art she herself learned from Merlin of which she was the pupil. She knows the secret of medicinal herbs, and the art of healing, she knows how to shape-shift and how to fly in the air. Her healing abilities give her in some Arthurian works a benevolent function, for example within the various romans of Chrétien de Troyes. She usually appears right on time to heal a wounded knight: she is the one that gave a balm to Yvain, the Knight of the Lion, to heal his madness. In these works, Morgane does not embody a force of destruction, but on the contrary she protects the happy endings and good fortunes of the Round Table. She is the providential fée that saves the souls born in high society and raised in the “courtois” worship of the lady. However, her powers of healing can reverse into a nefarious power when the fée has her ego wounded.

III/ The fatal temptress

In the prose Arthurian romans of the 13th century, Morgane can be summarized by one place. After being neglected by her lover Guyomar, she creates “le Val sans retour”, the Vale of No-Return, a place which will define her as a “femme fatale”. This place transports without the “littérature courtoise” the idea of the Celtic Otherworld. Also called “Le Val des faux amants” (The Vale of False Lovers), “le Val sans retour” is a cursed place where the fée traps all those that were unfaithful to her, by using various illusions and spells. As such, she manifests both her insatiable cruelty and her extreme jealousy. Lancelot will become the prime victim of Morgane because, due to his love for Queen Guinevere, he will refuse her seduction. The feelings of Morgane towards Lancelot rely on the ambivalence of love and hate: since she cannot obtain the love of the knight by natural means, she will use all of her enchantments and magical brews to submit Lancelot’s will. In vain. Lancelot will escape from the influence of this wicked witch. In “La Mort le roi Artu”, still for revenge, Morgan will participate in her own way to the decline to the Arthurian world: she will reveal to her brother, king Arthur, the adulterous love of Guinevre and Lancelot. She will bring to him the irrefutable proof of this affair by showing her what Lancelot painted when he had been imprisoned by her. The terrible war that marks the end of the Arthurian world will be concluded by the battle between Arthur and Mordred, the incestuous son of Arthur and Morgan. As such, Morgan appears as the instigator of the disaster that will ruin the Arthurian world. She manipulates the various actors of the tragedy and pushes them towards a deadly end. It should be noted that any sexual or romantic relationship between Arthur and Morgane are absent from the French romans – they are especially present within the British compilation of Malory, La Mort d’Arthur.

Behind the possessive woman described by the Arthurian texts, hides a more complex figure, a leftover of the ancient Celtic goddess of destinies. Cruel and manipulative, Morgan is fuses with the fear-inducing figure of the witch. Despite being an enemy of men, she keeps seeking their love. All of her personal tragedy comes from the fact that she fails to be loved. Always heart-sick, she takes revenge for her romantic failure with an incredible savagery. Her brutality manifest itself through the ugliness that some text will end up giving her – the ultimate rejection by this Christian world of this “devilish and lustful temptress”. “La Suite du Roman de Merlin” will try to give its own explanation for this transformation of Morgane, from good to wicked fairy: “She was a beautiful maiden until the time she learned charms and enchantments ; but because the devil took part in these charms and because she was tormented by both lust and the devil, she completely lost her beauty and became so ugly that no one accepted to ever call her beautiful, unless they had been bewitched”. In this new roman, she is responsible for a series of murders and suicides – and as the rival of Guinevere, she tries to cause King Arthur’s doom by favorizing her own lover, Accalon. Another fée, Viviane, will oppose herself to her schemes.

The demonization of the goddess is however not complete. Morgan appears in several “chansons de gestes” of the beginning of the 13th century, and even within the Orlando Furioso of the Arisote, in the sixth canto, in which she is the sister of the sorceress Alcina. She is presented as the disciple of Merlin. Seer and wizardess, she owns (within Avalon or the land of Faerie) a land of pleasure, a little paradise in which mankind can escape its condition. At the same time the Arthurian texts discredit her, she joins a strange historico-pagan syncretism, by being presented as the wife of Julius Caesar, and as the mother of Aubéron, the little king of Féerie.

After the Middle-Ages, the fée Morgane only mostly appears within the Breton folklore (the French-Britton folklore, of the French region of Bretagne). There, old mythical themes which inspired medieval literature are maintained alive, and keep existing well after the Middles-Ages. Morgane is given several lairs, on earth or under the sea. In the Côtes-d’Armor, there is a Terte de la fée Morgan, while a hill near Ploujean is called “Tertre Morgan”. There is an entire branch of popular literature in Bretagne (such as Charles Le Bras’ 1850 “Morgân”) where the fée represents the last survivor of a legendary land and the reminder of a forgotten past. She expresses the nostalgia of a lost dream, of a fallen Golden Age. True Romantic allegory of the lands and seas of Bretagne, she most notably embodies the feeling of a Bretagne land that was in search of its own soul.

However, it is her role of “cursed lover” that stays the most dominant within the Breton folklore. The vicomte de La Villemarqué, great collector of folktales and popular legends, noted in his “Barzaz Breiz” (1839) that the “morgan”, a type of water spirits, took at the bottom of the sea or of ponds, in palaces of gold and crystal, young people that played too close to their “haunted waters”. The goal of these fairies was to kidnap them to regenerate their cursed species. This ties the link between these “morganes” (also called “mary morgand”) and the Antique “fairy of fate”. Similar names, a same love of water, and the presence of the “land below the waves”, of a malevolent seduction – these are the permanent traits of Morgane, who keeps confusing and uniting the romantic instinct for love, and the desire for death. More modern adaptations of the legend (such as Marion Zimmer Bradley’s novels) weave an entire feminist fantasy around the figure of this fairy, supposed to embody the Celtic matriarchy.

#arthuriana#arthurian myth#arthurian legend#morgane#morgan#morgan le fey#fée#french folklore#folklore of bretagne#celtic mythology#irish mythology

50 notes

·

View notes

Text

arthur morgan is welsh, not english. boadicea was a brittonic celt legendary warrior queen, not an anglo one. letting arthur give that name to his horse is one of the examples where rockstar tries to allude to his welsh ancestry.

can't believe i'm still seeing "arthur is secretly interested in english history" takes bc of his horse's name, or "arthur is english" takes bc of his name (??? which is hella welsh??) or bc sean called him english. rockstar raised the count of welsh video game protagonists to a total of 2* and ppl still can't recognize how cool that is and try to (intentionally or not) take that away.

* (the other i know of being edward kenway)

101 notes

·

View notes

Text

I don't know if it's a red flag or not but evidently the one way you can get me to act like a Stereotypical Annoying American Celt (or as close as I can manage) is to post a meme mocking Late Antiquity/Iron Age Brittonic peoples when compared to Rome because you don't understand what "Brittonic" means and think you're successfully mocking modern white English people, who are Anglo-Saxon.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Celtic Borland

Y pouvlanç celtesc d'Istr Boral (y Bora Ale noncupað temporane) no's fort mis a regest. Y poy bustr tesmogn de lorry lengaç sousonn an dehiscenç for recent des y lengaç britton; creut es ig il alandau sull'istr des Albion, e noc des y tarmagn cos direct. The Celt population of Borland (self-described as the Bora Ale) is poorly documented. The few attestations of their language suggest only a recent divergence from the Briton tongue; they are thought to have arrived on the island from Albion, not directly from the continent.

L'oc cultur er conjognt ag sar marcer d'Europ par meyan dell'enascment de stan e de far. Jarry innajað dell'oc epoc es yent trovað tras toll'istr des loy allors remot com Egypt e Pers. This culture was connected to the European trade mesh via the export of tin and iron. Imported pottery of this period has been found across the island from as far afield as Egypt and Persia.

Y Celt stan compos ne form de bempart tribu; cascun afferjarau picq region eð er regnað des fortalleç colliner. Plaç religious diçr plusour temporane son dessevelið; y celeberrem es y labyrinth a Çadrosc, oc ayent largeç d'apponment lon fondamen cas sell'origin e bers. The Celts were organised into many tribes, each covering small regions and ruled from hill-forts. Several important religious sites of this time have been unearthed; most famously the Çadrosc labyrinth, which has sparked much unfounded theorising as to its origin and purpose.

1 note

·

View note

Text

North Sea Scotland (6): In Pictland

The Picts are Europe's noble savage.

Proud, fierce and independent, they are easy to admire, and chief among the admirers were their enemies. Tacitus, so-in-law of a Roman general who fought them, commended them for defending the world's "last inch of liberty".

The Picts could never be subdued, only wiped out. Their disappearance from the record around the 10th century adds to their mystique.

They had no writing but did not leave without a trace. About 200 carved stones remain dotted around the Picts' heartland.

A clutch of them are on display at a great little museum just north of Dundee, the Meigle Sculpture Stone Museum. They are not just stunning works of art: they bear testimony to a tragic history.

But before turning to those slabs, I'll go through a few things we know about the Picts from other sources. As mentioned in my previous post, they were a Brittonic people. Britons, by the way, are Celts who lived on the island of Britain during the Iron Age and are distinct from Gaelic Celts from Ireland.

While the Romans conquered most of Britain, Picts and other Brittonic holdouts kept them out of "Caledonia". The Anglo-Saxons who replaced the Romans also stayed south of the border – initially at least – to focus on fighting each other.

Meanwhile the Picts prospered. By the fifth century, their kingdom stretched from the top of Scotland to the Firth of Forth, the inlet just north of Edinburgh.

At a time when Anglo-Saxons and Gaelic Scots were fragmented into warring chiefdoms and clans, Pictland remained united (apart from a temporary north-south split following the introduction of Christianity).

So what was the secret of the Picts' success? I found a convincing explanation in Jamie Jeffers' engagingly erudite British History Podcast: matrilineal succession.

The rule around Europe then - and until the 20th century - was that first-born sons inherited the crown. The system might not yield the best person for the job but it had the virtue of simplicity: if a) your dad is king and b) you've got a penis but no older sibling who does, then you're next in line. End of.

The Picts had different approach. Tribal chiefs got together and settled successions through consensus, a process that was better at weeding out obvious inadequates than accident of birth.

And crucially, they chose among candidates who could trace their royal ancestry through the female line. As Jeffers notes, this prevented disputes: if the male carries the magic blood, there is always a possibility that his partner could carry another man's child and the throne loses its magic; if it's the woman who carries the magic blood, then you know that her offspring carries it as well.

Princesses, in other words, had quasi-mystical pulling power among Pictish nobles, a unifying feature reinforced by the deliberative selection system. To Jeffers' analysis, I would add the hypothesis that any increase in the status of women - even limited to royals - contributes to the cohesiveness, stability and sophistication of a society. Just look at today's Denmark vs the Tabilan's Afghanistan.

This brings me back to the Meigle museum, where the high degree of Pictish civilisation is on display.

The stones tell us about the beliefs of a deeply pious people.

Among the distinctive symbols and patterns are representations of fabulous creatures, including a lion with a man's head and dancing sea-horses (above).

The Picts were also fond of domestic animals.

The menageries above feature horses, stags, cattle as well as the manticore, a monster of middle-eastern origin with the tail of a scorpion. Clearly the Picts were aware of distant lands.

Several stones combine pagan and Christian symbols, illustrating how the new religion was assimilated into ancient beliefs. They show crosses superimposed on representations of animals. Note the seahorses again and the cat on the bottom left!

I couldn't help but see those stones as expressions of unity. As mentioned, northern Picts were slower than southerners in adopting Christianity. The carvings seem to say: whatever our beliefs, we are one nation.

The last of the stones date from about 850 AD. No trace of a Pictish civilisation remains beyond 900. This raises the question: if the Picts were so sophisticated, why did they vanish? Well, the superior nature of a civilisation does not a guarantee survival.

In the end, the Picts had too many enemies: Gaelic Scots to the west, Brittonic rivals to the south-west and increasingly assertive Anglo-Saxons in the south. For a while, the Picts dealt with these threats by a combination of force and bridal diplomacy. Pictish princesses married potential foes.

In the ninth century, Viking invasions forced the Picts to get closer to the Scots. This political shift led to Gaelic symbols appearing on Pictish stones.

In 843, Kenneth MacAlpin absorbed Pictland into his Scottish kingdom. The fact that his mother was Pictish helped the junior partner accept the takeover. But it spelled the end for their nation.

The Picts themselves, it appears, understood the limits of bridalism as a foreign-policy tool.

One of the more intriguing stones shows a human figure set upon by animals (below). Museum curators say she could be Guinevere, the wife of King Arthur.

The Welsh legend was adopted by the Picts. In their version Guinevere was a Pictish princess, known locally as Vanora, whose marriage to Arthur highlighted Brittonic unity against the Anglo-Saxons.

But the alliance did not work out: Vanora, as the carvings show, was fed to ravenous beasts by her jealous husband.

0 notes

Photo

Brittonic National Flag (Wales - Britanny - Cornwall) [The Red dragon is the symbol of Brittonic celts]

from /r/vexillology Top comment: That is a beautiful flag

#Brittonic#National#Flag#(Wales#-#Britanny#Cornwall)#[The#Red#dragon#symbol#celts]#flags#vexillology

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

Did the ancient Celts really paint themselves blue?

Part 1: Brittonic Body Paint

Clockwise from top left: participants in the Picts Vs Romans 5k, a 16th c. painting of painted and tattooed ancient Britons, Boudica: Queen of War (2023), Brave (2012).

The idea that the ancient and medieval Insular Celts painted themselves blue or tattooed themselves with woad is common in modern culture. But where did this idea come from, and is there any evidence for it? In this post, I will examine the evidence for the use of body paint among the ancient peoples of the British Isles, including both written sources and archaeology.

For this post, I am looking at sources pertaining to any ethnic group that lived in the British Isles from the late Iron Age through the early Roman Era. (Later Roman and Medieval sources will be discussed in part 2.) The relevant text sources for Brittonic body paint date from approximately 50 BCE to 100 CE. I am including all British Isles cultures, because a) determining exactly which Insular culture various writers mean by terms like ‘Briton’ is sometimes impossible and b) I don’t want to risk excluding any relevant evidence.

Written Sources:

The earliest source for our notion of blue Celts is Julius Cesar's Gallic War book 5, written circa 50 BCE. In it he says, "Omnes vero se Britanni vitro inficiunt, quod caeruleum efficit colorem, atque hoc horridiores sunt in pugna aspectu," which translates as something like, "All the Britons stain themselves with woad, which produces a bluish colouring, and makes their appearance in battle more terrible" (translation from MacQuarrie 1997). Hollywood sometimes interprets this passage as meaning that the Celts used war paint, but Cesar says that all Britons colored themselves, not just the warriors. The blue coloring just had the effect (on the Romans at least) of making the Briton warriors look scary. The verb inficiunt (infinitive inficio) is sometimes translated as 'paint', but it actually means dye or stain. The Latin verb for paint is pingo (MacQuarrie 1997).

The interpretation of vitro as woad is supported by Vitruvius' statements in De Architectura (7.14.2) that vitrum is called isatis by the Greeks and can be used as a substitute for indigo. Isatis is the Greek word for woad; this is where we get its modern scientific name Isatis tinctoria. Woad and indigo both contain the same blue dye pigment, hence woad can be used as a substitute for indigo (Carr 2005, Hoecherl 2016). The word vitro can also mean 'glass' in Latin, but as staining yourself with glass doesn't make much sense, it's more commonly interpreted here as woad (Carr 2005, Hoecherl 2016, MacQuarrie 1997). I will revisit this interpretation during my discussion of the archaeological evidence.

Almost a century later in De situ orbis, Pomponius Mela says that the Britons "whether for beauty or for some other reason — they have their bodies dyed blue," (translation by Frank E. Romer) using virtually identical language to Cesar, "vitro corpora infecti" (Lib. III Cap. VI p. 63). Pomponius Mela may have copied his information from Cesar (Hoecherl 2016).

Then in 79 CE, Pliny the Elder writes in Natural History book 22 ch 2, "There is a plant in Gaul, similar to the plantago in appearance, and known there by the name of "glastum:" with it both matrons and girls among the people of Britain are in the habit of staining the body all over, when taking part in the performance of certain sacred rites; rivalling hereby the swarthy hue of the Æthiopians, they go in a state of nature." In spite of the fact that glastum means woad in the Gaulish and Celtic languages, Pliny seems to think glastum is not woad. In Natural History book 20 ch 25, he describes different plant which is almost certainly woad, a “wild lettuce” called "isatis" which is "used by dyers of wool." (Woad is a well-known source of fabric dye (Speranza et al 2020)).

Of course, "rivaling the swarthy hue of the Æthiopians" doesn't necessarily mean blue. Pliny seems to think Ethiopians literally have coal-black skin (Latin ater). Additionally, Pliny is taking about a ritual done by women, where Cesar was talking about a practice done by everyone. Are they talking about 2 different cultural practices, or is one of them reporting misinformation? Or are both wrong? Unfortunately, there is no way to know.

The Roman poets Ovid, Propertius, and Marcus Valerius Martialis all make references to blue-colored Britons (Carr 2005), but these are literary allusions, not ethnographic reports. As such, they don't really provide additional evidence that the Britons were actually dyeing or painting themselves blue (Hoecherl 2016). These poetic references merely demonstrate that the Romans believed that the Britons were.

In the sources that come after Pliny the Elder, starting in the 3rd century, there is a shift in the terms used. Instead of inficio which means to dye or stain (Hoecherl 2016), probably a temporary application of color to the surface of the skin, later sources use words like cicatrices (scars) and stigma/stigmata (brand, scar, or tattoo) (Hoecherl 2016, MacQuarrie 1997, Carr 2005) which suggest a permanent placement of pigment under the skin, i.e. a tattoo. This evidence for tattooing will be discussed in a second post.

Discussion:

Although the Romans clearly believed that the Britons were coloring themselves with blue pigment, that doesn't necessarily mean that Julius Cesar, Pomponius Mela, or Pliny the Elder are reliable sources.

In the sentence before he claims that all Britons color themselves blue, Julius Cesar says that most inland Britons "do not sow corn [aka grain], but live on milk and flesh and clothe themselves in skins." (translation from MacQuarrie 1997). This is demonstrably false. Grains like wheat and barley and storage pits for grain have been found at multiple late Iron Age sites in inland Britain (van der Veen and Jones 2006, Lightfood and Stevens 2012, Lodwick et al 2021). This false characterization of Insular Celts as uncivilized savages would continue to show up more than a millennium later in English descriptions of the Irish.

Pomponius Mela, in addition to believing in blue-dyed Britons, also believed that there was an island off the coast of Scythia inhabited by a race called the Panotii "who for clothing have big ears broad enough to go around their whole body (they are otherwise naked)" (Chorographia Bk II 3.56 translation from Romer 1998). Pliny the Elder also believed in Panotii.

15th-century depiction of a Panotii from the Nuremberg Chronicle. Was Celtic body paint as real as these guys?

The Roman historians Tacitus and Cassius Dio make no mention of body paint in their coverage of Iron Age British history (Hoecherl 2016). Their silence on the subject suggests that, in spite of Cesar's claim that all Britons colored themselves blue, the custom of body staining or painting was not actually widespread.

Considering all of these issues, is any of this information trustworthy? Based on my experience studying 16th c. Irish dress, even bigoted sources based on second-hand information often have a grain of truth somewhere in them. Unfortunately, exactly which bit is true is hard to identify without other sources of evidence, and this far in the past we don't have much.

Archaeological Evidence:

There are no known artistic depictions of face paint or body art from Great Britain during this time period. There are some Iron Age continental European coins that show what may be face painting or tattoos, but no such images have been found on British coins (Carr 2005, Hoecherl 2016).

In order for the Britons to have dyed themselves blue, they needed to have had blue pigment. Woad is not native to Great Britain (Speranza et al 2020), but Woad seeds have been found in a pit at the late Iron Age site of Dragonby in England, so the Britons had access to woad as a potential pigment source in Julius Cesar's time (Van der Veen et al 1993). Egyptian blue is another possible source of blue pigment. A bead made of Egyptian blue was found at a late Bronze Age site in Runnymede, England. Pieces of Egyptian blue could have been powdered to produce a pigment for body paint. (Hoecherl 2016). Egyptian blue was also used by the Romans to make blue-colored glass (Fleming 1999). Perhaps this is what Cesar meant by 'vitro'.

Potential sources of blue: Isatis tinctoria (woad) leaves and a lump of Egyptian blue from New Kingdom Egypt

Modern experiments have found that reasonably effective body paint can be made by mixing indigo powder either with water, forming a runny paint which dries on the skin, or with beef drippings, forming a grease paint which needs soap to be removed (Carr 2005, reenactor description). The second recipe is very similar to one used by modern east African argo-pastoralists which consists of ground red ocher mixed with cow fat (unpublished interview*).

Finding blue pigment on the skin of a bog body might confirm Julius Cesar's claim, but unfortunately, the results here are far from conclusive. To my knowledge, Lindow II is the only British bog body that has been tested for indigotin, the dye pigment in woad and indigo. No indigotin was found (Taylor 1986).

The late Iron Age-early Roman era bog bodies Lindown II and Lindown III show some evidence of mineral-based body paint (Joy 2009, Giles 2020). Both of them have elevated levels of calcium, aluminum, silicon, iron, and copper in their skin. Lindow III also has elevated levels of titanium. The calcium levels may simply be the result the of the bog leeching calcium from their bones. Some researchers have suggested that the other elements may be from mineral-based paints applied to the skin. The aluminum and silicon may be from clay minerals. The iron and titanium could be from red ocher. The copper could be from malachite, azurite, or Egyptian blue (CuCaSiO4), pigments that would give a green or blue color (Pyatt et al 1995, Pyatt et al 1991). These elements may have other sources however, and are not present in large enough amounts to provide definitive proof of body paint (Cowell and Craddock 1995, Giles 2020). Testing done on the early Roman Era (80-220 CE) Worsley Man has found no evidence of mineral-based paint (Giles 2020).

One final type of artifact that provides some support for Julius Cesar's claim is a group of small cosmetic grinders from late Iron Age-Roman Era Britain. These mortar and pestle sets are found almost exclusively in Great Britain and are of a style which appears to be an indigenous British development. They are distinctly different from the stone palettes used by the Romans for grinding cosmetics which suggests that these British grinders were used for a different purpose than making Roman-style makeup (Carr 2005). Archaeologist Gillian Carr has suggested that these British grinders might have been used by the Britons for grinding, mixing, and applying a woad-based body paint (Carr 2005).

Left and center: Cosmetic grinder set from Kent. Right: Cosmetic mortar from Staffordshire. images from Portable Antiquities Scheme under CC attribution license

The mortars have a variety of styles of decoration, but the pestles (top left and top center) typically feature a pointed end which could be used for applying paint to the skin (Carr 2005). The grinders are quite small, (most are less than 11 cm (4.5 in) long), making them better suited to preparing paint for drawing small designs rather than for dyeing large areas of skin (Carr 2005, Hoecherl 2016).

Conclusions:

Admittedly, this post is a bit off-topic, since the Irish are not mentioned, but dress history is also about what people did not wear. Hollywood has a tendency to overgeneralize and expropriate, so I want to be clear: There is no known evidence that the ancient Irish used body paint.

So, who did? For the reasons I have already discussed, I don't consider any of the Roman writers particularly trustworthy, but I think the following conclusions are plausible:

A least a few people in Great Britain dyed/stained or painted their bodies between circa 50 BCE and perhaps 100 CE, after which mentions of it end. Written sources from c. 200 CE on talk about tattoos rather than painting or staining. The custom of body dyeing/painting may have started as something practiced by everyone and later changed to something practiced by just women.

None of the writers mention any designs being painted, but Julius Cesar's description could encompass designs or solid area of color. Pliny, on the other hand, states that women were coloring their entire bodies a solid color. The dye was probably blue, although Pliny implies it was black. (I know of no plants in northern Europe that resemble plantago and produce a black dye. I think Pliny was reporting misinformation.)

Archaeological evidence and experimental recreations support the possibility that woad was the source of the pigment, but they cannot confirm it. Data from bog bodies indicate that a mineral pigment like azurite or Egyptian blue is more likely, but these samples are too small to be conclusive.

The small cosmetic grinders are suitable for making designs which might match Cesar and Mela's descriptions, but not Pliny's description of all-over body dyeing.

*Interview with a Daasanach woman I participated in while doing field school in Kenya in 2015.

Leave me a tip?

Bibliography:

Carr, Gillian. (2005). Woad, Tattooing and Identity in Later Iron Age and Early Roman Britain. Oxford Journal of Archaeology 24(3), 273–292. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0092.2005.00236.x

Cowell, M., and Craddock, P. (1995). Addendum: Copper in the Skin of Lindow Man. In R. C. Turner and R. G. Scaife (eds) Bog Bodies: New Discoveries and New Perspectives (p. 74-75). British Museum Press.

Fleming, S. J. (1999). Roman Glass; reflections on cultural change. University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, Philadelphia. https://www.google.com/books/edition/Roman_Glass/ONUFZfcEkBgC?hl=en&gbpv=0

Giles, Melanie. (2020). Bog Bodies Face to face with the past. Manchester University Press, Manchester. https://library.oapen.org/viewer/web/viewer.html?file=/bitstream/handle/20.500.12657/46717/9781526150196_fullhl.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

Hoecherl, M. (2016). Controlling Colours: Function and Meaning of Colour in the British Iron Age. Archaeopress Publishing LTD, Oxford. https://www.google.com/books/edition/Controlling_Colours/WRteEAAAQBAJ?hl=en&gbpv=0

Joy, J. (2009). Lindow Man. British Museum Press, London. https://archive.org/details/lindowman0000joyj/mode/2up

Lightfoot, E., and Stevens, R. E. (2012). Stable Isotope Investigations of Charred Barley (Hordeum vulgare) and Wheat (Triticum spelta) Grains from Danebury Hillfort: Implications for Palaeodietary Reconstructions. Journal of Archaeological Science, 39(3), 656–662. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2011.10.026

Lodwick, L., Campbell, G., Crosby, V., Müldner, G. (2021). Isotopic Evidence for Changes in Cereal Production Strategies in Iron Age and Roman Britain. Environmental Archaeology, 26(1), 13-28. https://doi.org/10.1080/14614103.2020.1718852

MacQuarrie, Charles. (1997). Insular Celtic tattooing: History, myth and metaphor. Etudes Celtiques, 33, 159-189. https://doi.org/10.3406/ecelt.1997.2117

Pomponius Mela. (1998). De situ orbis libri III (F. Romer, Trans.). University of Michigan Press. (Original work published ca. 43 CE) https://topostext.org/work/145

Pyatt, F.B., Beaumont, E.H., Buckland, P.C., Lacy, D., Magilton, J.R., and Storey, D.M. (1995). Mobilization of Elements from the Bog Bodies Lindow II and III and Some Observations on Body Painting. In R. C. Turner and R. G. Scaife (eds) Bog Bodies: New Discoveries and New Perspectives (p. 62-73). British Museum Press.

Pyatt, F.B., Beaumont, E.H., Lacy, D., Magilton, J.R., and Buckland, P.C. (1991) Non isatis sed vitrum or, the colour of Lindow Man. Oxford Journal of Archaeology, 10(1), 61–73. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/227808912_Non_Isatis_sed_Vitrum_or_the_colour_of_Lindow_Man

Speranza, J., Miceli, N., Taviano, M.F., Ragusa, S., Kwiecień, I., Szopa, A., Ekiert, H. (2020). Isatis Tinctoria L. (Woad): A Review of Its Botany, Ethnobotanical Uses, Phytochemistry, Biological Activities, and Biotechnical Studies. Plants, 9(3): 298. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants9030298

Taylor, G. W. (1986). Tests for Dyes. In I. Stead, J. B. Bourke and D. Brothwell (eds) Lindow Man: the Body in the Bog (p. 41). British Museum Publications Ltd.

Van der Veen, M., and Jones, G. (2006). A Re-analysis of Agricultural Production and Consumption: Implications for Understanding the British Iron Age. Vegetation History and Archaeobotany, 15 (3), 217–228. doi:10.1007/s00334-006-0040-3 https://www.researchgate.net/publication/27247136

Van der Veen, M., Hall, A., and May, J. (1993). Woad and the Britons painted blue. Oxford Journal of Archaeology, 12(3), 367-371. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/249394983

#cw anti-black racism#romano-british#period typical bigotry#iron age#bog bodies#no photographs of bog bodies though#roman era#ancient celts#celtic#woad#insular celts#anecdotes and observations#body paint#brittonic#archaeology

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

History of the Welsh language

Welsh is an ancient Celtic language that has been spoken in Britain for many hundreds of years. This may leave you wondering why not all Welsh people speak Welsh. In order to answer this, we have to take a look at the history of Wales and the Welsh language.

Nobody’s particularly too sure when Welsh began, or how. Unfortunately, old and scarcely documented history is pretty difficult to pin down like that. It is, however, widely proposed that Welsh has been around for at least roughly 4000 years. I don’t know if you’d agree, but that’s a hell of a long time! However, we do know that Welsh developed alongside closely related languages like Cornish and Breton, as well as the more distantly related Gaelic languages, across the British isles and parts of mainland Europe.

For a long time, Welsh was free to grow and develop from Old Welsh into Middle Welsh. Lots of Welsh prose was created during this time, and it is within the lifespan of Middle Welsh that the Mabinogion (a famous collection of Welsh mythologies) was compiled. Many great bards* also passed on tales in Welsh during this period. Welsh continued to thrive and grow freely for a period of time *Bards in Welsh culture are storytellers through the medium of music and poetry. They were considered to be fairly powerful in courts of nobles and are an important historical and tradtional position to have been appointed

However, trouble struck when Henry VIII was on the English throne. Wales had previously been conquered by the English and, during Henry VIIIs rule of England and Wales, the Act of Union was passed. As part of this act, the use of Welsh for administrative purposes (e.g. in laws, in the workplace) was completely banned, with the Welsh language no longer being recognised as an official language under the crown. This act meant that all students in Wales were no longer allowed to be taught in their native language and, for most people, the only language they knew at all. Children were forced to attend schools in a completely foreign language, which began the supression of Welsh. Additionally, within schools a tool of supression was used to stifle all communications in Welsh. Any child caught speaking Welsh during the school day would be made to wear the Welsh Not, which was typically a wooden board with the words “Welsh Not” painted on. The child that was wearing the Welsh Not at the end of the day would be subject to corporal punishment, which typically was a beating with a cane.

It was not until the Welsh Language Act of 1967 that the Welsh language gained any form of legal protection against the supression and brutalities faced previously. This act allowed the use of Welsh in legal proceedings within the government. However, Welsh still had a long ways to go. In 1980, members of the political party Plaid Cymru pledged that they would go to prison rather than pay for TV licenses in order to advocate for the need for a Welsh language television channel. Their efforts were successful and they were rewarded with the Welsh Fourth Channel, commonly known as S4C. Finally, in 1993, the Welsh Language Act of 1993 was passed. This act meant that, for the first time in hundreds of years, the Welsh language was now considered legally equal to that of the English language. Alongside the passing of this act came the benefits for the Welsh language that Welsh could not legally be discriminated against and must be available easily from all public bodies. This meant that all road signs in Wales could now be bilingual and that all government work must be published bilingually, to name a few examples.

I greatly hope that I have managed to teach you something interesting, and if not that you enjoyed the read on the history of the Welsh language. As a Welsh person and Welsh speaker, this topic is very important to me and fills me to the brim with a fiery Celtic passion. I hope those of you from elsewhere can empathise with our fight to preserve our language and I hope it might encourage interest in Welsh as a whole.

Diolch am wedi darllen, Cymru am byth <3

#wales#welsh#welsh language#history#language#language learning#langblog#language history#celtic#Celts#celt#Brythonic#brittonic#united kingdom#uk#great britain#britain#british#education#educational#info#info post#information#cymru#cymraeg#dysgu cymraeg#cymru am byth#cymraes#welsh langblr#learn

175 notes

·

View notes

Text

I'm getting that feeling of being slowly pulled into a research rabbit hole again...

How do you separate medieval architecture from Roman and Christian influences? With great difficulty, it turns out.

Basically throw pre-Romanised Celtic architecture, pre-Christianised Germanic architecture, and a smattering of Norse Viking era architecture into a blender, and forget everything you know about church or castle architecture...

So far (and this is simplifying things down to a criminal degree here) I've got roughly that Brittonic, Irish and Scottish Celts ere towards round houses and anti right angle constructions, Anglo Saxon's ere towards more rectangular and square dwellings, but can be partial to a circle or two at times, and the Norse like long things with spiky roofs.

Most of these are non-stone constructions too, so archaeological sources are somewhat sparse... Must Farm being a glorious and local exception, but one cannot build an architectural style from one marshland settlement alone.

Oh well, I do love a challenge.

Pretty Pictures Below:

Newgrange, County Meath, Ireland - 3200 BC (ish)

Photograph from Johnbod Wikimedia Commons

Skara Brae, Bay of Skaill, Orkney - 3180 BC-2500 BC

Photograph from Dr John F. Burka Wikimedia Commons

Reconstructed Longhouse, Viking Museum Borg, Vestvågøy/Lofoten, Norway

Photograph from Jörg Hempel Wikimedia Commons

Reconstruction Bryn Eryr Farmstead, St Fagans National History Museum, South Glamorgan, Wales

Photograph from M J Roscoe Wikimedia Commons

Reconstruction, West Stow Anglo-Saxon Village, Suffolk

Photograph from Midnightblueowl Wikimedia Commons

Now all I've got to do is stick about 800 years of development on what I can scrape out of the blender!

#MyrkMire#background research#background work#interactive fiction#hosted games#choice of games#interactive games

54 notes

·

View notes

Note

honestly hadn't thought of the first men/native americans parallels before but you're right they're definitely there! personally my first impression was first men = celts, andals = saxons, ironborn = danes but that's v much from a british perspective.

i mean theres obvs a lot of inspiration from gaelic cultures for the first men (pre-andal reach is wales ill die on this hill) and i guess i would argue that the andal invasions are more similar to saxon settlement than european colonisation? as in, not nearly as genocidal, not coming in as a unified force or trying to create a unified state, those left in the andal/saxon controlled portion end up assimilating to the invaders' culture. oh and also im a bit obsessed with the whole mystery around the vanishing of brittonic languages in saxon britain and mayyy have elaborate headcanons on the andal replacing of the first men languages based on that.

oh and the whole ironborn/danes thing. well the viking parallels are obvious. and then the danelaw was my first thought when i read about ironborn controlled riverlands haha.

ah sorry just to be clear im not trying to say you're wrong!! i just find pre-targ westeros v fun and would love to hear more about your headcanons cause it sounds like they'd be p different to mine! i also don't know that much about different native american cultures - do u have thoughts on the inspirations for different first men regions? i mean obvs the north and wildlings you'd be looking at inuit cultures but do you have thoughts on the others? i also thought an interesting parallel to the north would be the saami altho im also pretty uneducated on them haha.

anyway i just really love worldbuilding fantasy cultures because of how it prompts me to find out more about various real world cultures - and it makes sense to take inspiration from multiple real world cultures. i mean one of the reasons i love tolkien's dwarves so much is they prompt the question 'what exactly would a fusion of old norse and jewish cultures + a few original bits such as a love of geology and craftsmanship even begin to look like'. (although i do also know it's important to remember that real world cultures are real and to be respectful of them, especially when they're not my own and especially when it's an oppressed culture)

anyway sorry for the essay in your inbox feel free to ignore i just love rambling on about this stuff! also in terms of your original point - yeah the people who whine about 'bla bla but they're meant to be white' are so dull. i mean 1) it's all made up anyway who cares 2) 'white' is either a post-colonial construction within a specific political, historical, and cultural context or just a description of skin colour. it means basically nothing from an in-universe fantasy perspective (obviously the choice of which characters are white and how they're written is important from an out-universe perspective grrm would it kill you to be normal about non-northwestern european cultures). also the valyrians aren't white they do not have pale skin just look at where valyria is located on a map. sometimes the author is wrong.

no worries i LOVE this ask i lovelovelove just talking and rambling about things im interested in and care about and i LOVELOVELOVE when people do it back!!

yeah personally i figured the northern first men were based on the picts since the wall is clearly inspired by hadrian's wall and the celtic influence is clear too. in the show the spiral motif they introduced reminded me of the celtic triskelion (though its more proto-indo-european than celtic) which tickled my brain!! YES ON THE REACH WALES THING because garth greenhand and their national founding myth is SOOO king arthur they have such a culture of chivalry plus there’s a bunch of arthurian-inspired names sprinkled throughout the reach (off the top of my head there’s agramore(agravain), gawen (gawain) and perceon(percival))

the ironborn danes is very much text and canon, they’re clearly vikings and i think GRRM has specfically said that. however i think sea-faring peoples can easily be identified as polynesian/pasifika.

for me there what the text presents which is that westeros is grea britain with medieval moorish spain taped to the bottom of it, and then there’s the more culturally interesting fanon in my head that still mostly fits into canon! since the concept of whiteness obvi doesnt exist like you said and genetics are hand waved there’s really nothing in the text that denies an indigenous north.

i personally see them as indigenous siberian (specifically yakut) since the first men allegedly travelled from the dothraki sea and many indigenous ethnic groups of siberia such as the yakut are north asian and turkic which fits into the way the dothraki are written. im not american so i dont know much about inuit and first nations american traditions but in my head i see the free folk as inuit!

i really agree with your last paragraph, i think the way fandom projects whiteness onto these characters is due to a majority northern american fanbase who aren’t doing it out of malice but more ignorance. take the example of dorne: theyre obviously based on medieval al-andalus spain, specifically after the umayyad conquest. this textually implies west asian middle eastern influence.

its a little funny how people cling to daeron targaryen’s racial classification guide when harassing artists over their depictions of characters because if anything that’s the literal whitest part of the text lol. his three categories (stony, salty and sandy) vary from ‘european’ pale skinned to olive-skinned to dark-skinned. whos to say that doesn’t fit a popular fanon dornish india, which famously has many ethnic groups of varying physical appearance? regardless of the fact this is fiction books where people can do what they want, there’s nothing textually that rejects a physically indian-looking dorne.

many characters aren’t described with pale skin. sansa, dany and cersei are a few i can think of but rarely are side characters described as such. there is a presumption from the reader and the author that these characters are white simply because that’s just the norm, right? but it’s not, nor is this series real-life. a lot of my headcanons are still based on the text but really that doesnt matter!! its fake books and we’re having fun and i can think of the characters however i want. and lastly, youre so right about valyria. i see them as east asian since theyre, well, from east essasia but i think its funny to argue with redditors by saying theyre egyptian since well thats obviously part of the inspiration!! what are you gonna do, argue with grrm???

idk your ask was really well presented and my answer is distinctly ramblings of a brain with no stoplights so apologies but your ask made me think lots thank you!!!!

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Who are their parents?

I like to think that, aside from sibling relationships, some Nations had parents, either adopted or ‘biologically’. We know in the canon they were Ancient Nations, such as Ancient Greece, Ancient Egypt or Germania. That includes Britannia for the UK+Ireland brothers, but I believe they had more than one parent.

Nations aren’t ‘born’ the human way. Instead, they can either be born from the Land itself by having a cord-like attached to them from the ground (explaining why they have a belly button) or just appearing (also with a belly button with the power of ~magic~). Like one day, they just woke up as a young child in the middle of a field. Were they humans before, or did they just materialize out of thin air? No one knows. Humans usually adopt them or at least let them stay in the village, thinking the nation is an orphan or lost.

However, there’s a difference between being born from the Land and appearing on the Land. That’s where the ‘biological’ versus ‘adopted’ come into play.

When a Land is already occupied and a new nation is born from it, that means they’re ‘biologically’ related because they share the same foundation. The foundation can mean the same language, culture, people and more. They’re normally a descendant of the older nation.

For example, my headcanon for Ireland is that her mother wasn’t Britannia or, as others call her, Albion. Ireland’s mother was in fact Ériu or Cessair as her human name. I took inspiration from the collection of poems “Lebor Gabála Érenn”, the Book of Invasions. It says that Cessair was the leader of the first inhabitant of Ireland. In a way, that makes her one of the Ancients. Our modern Ireland, Éire, was born on the sixth and final invasion, the Milesians. They represent the Irish people we know today. She found him as a baby, attached to the Land, and knew he was hers. They shared a deeper connection because they come from the same Land. Sadly, she Faded shortly after so Ireland was later adopted by Albion.

A nation that is born by ‘appearing’ doesn’t share the same foundation as the older nation. Appearing nations usually represent a new language, a shift in culture, or other bigger change. Imagine blowing on a dandelion and one of the seeds fall into the ground before growing into a plant: that’s an Appearing nation. They’re different from the Old ones and more prone to danger because it meant that change is on the way.

Another example, my hc for Britannia, aka Albion, is that she found baby England wandering one day in her Land. He wasn’t born from the Land, instead, he Appeared because the Anglo-Saxon was quite different from her Brittonic roots. Whereas for Wales, he was born from the Land since he shares some of the same foundations as hers. She knew what that meant for her to raise little ones, that it meant her time was coming, but she loved them as her sons and raised them as much as she could before she returned to the Land, just like Ériu.

Not all Ancient nations were compassionate with new nations. It wasn’t uncommon to kill the young ones, back in the day, when they appeared or were born from the Land. Ancients nations were different from the modern ones, they had a different way of living and would not hesitate to eliminate the first sign of trouble for fear of being replaced or claimed.

That was what almost happened to Scotland when he was found by Celt. The man didn’t want anything to do with the baby that came from the Land and was ready to let mother nature claim him. Unfortunately for him, baby Scotland was stubborn and wouldn’t leave him alone, even with threats thrown at him. In the end, Celt begrudgingly took him under his wing (by leaving him most of the time with Albion, but he tried lol). This is why the four of them see each other as brothers because Albion raised them until she Faded.

Nowadays, there’s a small chance for a new nation to appear/be born since most of the world is already populated. Unless there’s a big change that spurs the birth of a nation on claimed land, then the sight of a baby/toddler would be quite a shock. Which was the case for Northern Ireland when he was born from the Land back in the 1920s. Even the micronations are a novelty because it has been a long time since nations were children themselves.

More headcanons

#hetalia#hws ireland#aph ireland#hws aph england#hws england#aph wales#hws wales#aph scotland#hws scotland#aph norhtern ireland#hws northern ireland#headcanon#hopefully my rambling makes sense lol#I could go on and on about this but I had to stop xD

38 notes

·

View notes