#anecdotes and observations

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Did the ancient Celts really paint themselves blue?

Part 2: Irish tattoos

Clockwise from top left: Deirdre and Naoise from the Ulster Cycle by amylouioc, detail from The Marriage of Strongbow and Aoife by Daniel Maclise, a modern Celtic revival tattoo, Michael Flatley in a promotional image for the Irish step dance show 'Lord of the Dance'

This is my second post exploring the historical evidence for our modern belief that the ancient and medieval Insular Celts painted or tattooed themselves with blue pigment. In the first post, I discussed the fact that body paint seems to have been used by residents of Great Britain between approximately 50 BCE to 100 CE. In this post, I will examine the evidence for tattooing.

Once again, I am looking at sources pertaining to any ethnic group who lived in the British Isles, this time from the Roman Era to the early Middle Ages. The relevant text sources range from approximately 200 CE to 900 CE. I am including all British Isles cultures, because a) determining exactly which Insular culture various writers mean by terms like ‘Briton’, ‘Scot’, and ‘Pict’ is sometimes impossible and b) I don’t want to risk excluding any relevant evidence.

Continental Written Sources:

The earliest written source to mention tattoos in the British Isles is Herodian of Antioch’s History of the Roman Empire written circa 208 CE. In it, Herodian says of the Britons, "They tattoo their bodies with colored designs and drawings of all kinds of animals; for this reason they do not wear clothes, which would conceal the decorations on their bodies" (translation from MacQuarrie 1997). Herodian is probably reporting second-hand information given to him by soldiers who fought under Septimius Severus in Britain (MacQuarrie 1997) and shouldn't be considered a true primary source.

Also in the early 3rd century, Gaius Julius Solinus says in Collectanea Rerum Memorabilium 22.12, "regionem [Brittaniae] partim tenent barbari, quibus per artifices plagarum figuras iam inde a pueris variae animalium effigies incorporantur, inscriptisque visceribus hominis incremento pigmenti notae crescunt: nec quicquam mage patientiae loco nationes ferae ducunt, quam ut per memores cicatrices plurimum fuci artus bibant."

Translation: "The area [of Britain] is partly occupied by barbarians on whose bodies, from their childhood upwards, various forms of living creatures are represented by means of cunningly wrought marks: and when the flesh of the person has been deeply branded, then the marks of the pigment get larger as the man grows, and the barbaric nations regard it as the highest pitch of endurance to allow their limbs to drink in as much of the dye as possible through the scars which record this" (from MacQuarrie 1997).

This passage, like Herodian's, is clearly a description of tattooing, not body staining or painting. That said, I have no idea of tattoos actually work like this. I would think this would result in the adult having a faded, indistinct tattoo, but if anyone knows otherwise, please tell me.

The poet Claudian, writing in the early 5th c., is the first to specifically mention the Picts having tattoos (MacQuarrie 1997). In De Bello Gothico he says, "Venit & extremis legio praetenta Britannis,/ Quæ Scoto dat frena truci, ferroque notatas/ Perlegit exanimes Picto moriente figuras."

Translation: "The legion comes to make a trial of the most remote parts of Britain where it subdues the wild Scot and gazes on the iron-wrought figures on the face of the dying Pict" (from MacQuarrie 1997).

Last, and possibly least, of our Mediterranean sources is Isidore of Seville. In the early 7th c. he writes, "the Pictish race, their name derived from their body, which the efficient needle, with minute punctures, rubs in the juices squeezed from native plants so that it may bring these scars to its own fashion [. . .] The Scotti have their name from their own language by reason of [their] painted body, because they are marked by iron needles with dark coloring in the form of a marking of varying shapes." (translation from MacQuarrie 1997)

Isidore is the earliest writer to explicitly link the name 'Pict' to their 'painted' (Latin: pictus) i.e. tattooed bodies. Isidore probably borrowed information for his description from earlier writers like Claudian (MacQuarrie 1997).

In the 8th century, we have a source that definitely isn't Romans recycling old hearsay. In 786, a pair of papal legates visited the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms of Mercia and Northumbria (Story 1995). In their report to Pope Hadrian, the legates condemn pagans who have "superimposed most hideous cicatrices" (i.e gotten tattoos), likening the pagan practice to coloring oneself "with dirty spots". The location of the visit indicates that these are Anglo-Saxon tattoos rather than Celtic, but some scholars have suggested that the Anglo-Saxons might have adopted the practice from the Brittonic Celts (MacQuarrie 1997).

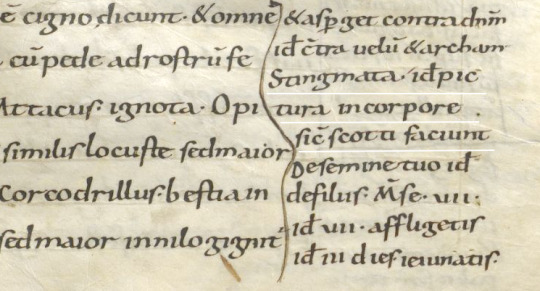

A gloss in the margin of the late 9th c. German manuscript Fulda Aa 2 defines Stingmata [sic] as "put pictures on the bodies as the Irish (Scotti) do." (translation from MacQuarrie 1997).

Fulda Aa 2 folio 43r The gloss is on the left underlined in white.

Irish Written Sources:

Irish texts that mention tattoos date to approximately 700-900 CE, although some of them have glosses that may be slightly later, and some of them cannot be precisely dated.

The first text source is a poem known in English as "The Caldron of Poesy," written in the early 8th c. (Breatnach 1981). The poem is purportedly the work of Amairgen, ollamh of the legendary Milesian kings. In the first stanza of the poem, he introduces himself saying, "I being white-kneed, blue-shanked, grey-bearded Amairgen." (translation from Breatnach 1981)

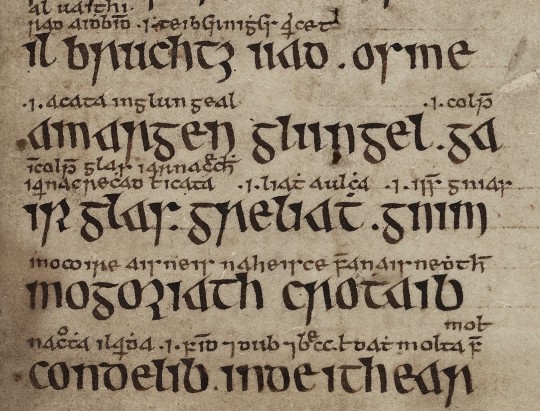

The text of the poem with interline glosses from Trinity College Dublin MS 1337/1

The word garrglas (blue-shanked) has a Middle Irish (c. 900-1200) gloss added by a later scribe, defining garrglas as: "a tattooed shank, or who has the blue tattooed shank" (Breatnach 1981).

Although Amairgen was a mythical figure, the position ollamh was not. An ollamh was the highest rank of poet in medieval Ireland, considered worthy of the same honor-price as a king (Carey 1997, Breatnach 1981). The fact that a man of such esteemed status introduces himself with the descriptor 'blue-shanked' suggests that tattoos were a respectable thing to have in early medieval Ireland.

The leg tattoos are also mentioned c. 900 CE in Cormac’s Glossary. It defines feirenn as "a thong which is about the calf of a man whence ‘a tattooed thong is tattooed about [the] calf’" (translation from MacQuarrie 1997)

The Irish legal text Uraicecht Becc, dated to the 9th or early 10th c., includes the word creccoire on a list of low-status occupations (Szacillo 2012, MacNeill 1924). A gloss defines it as: crechad glass ar na roscaib, a phrase which Szacillo interprets as meaning "making grey-blue sore (tattooing) on the eyes" (2012). This sounds rather strange, but another early Irish text clarifies it.

The Vita sancti Colmani abbatis de Land Elo written around the 8th-9th centuries (Szacillo 2012) contains the following episode:

On another time, St Colmán, looking upon his brother, who was the son of Beugne, saw that the lids of his eyes had been secretly painted with the hyacinth colour, as it was in the custom; and it was a great offence at St Colmán’s. He said to his brother: ‘May your eyes not see the light in your life (any more). And from that hour he was blind, seeing nothing until (his) death. (translation from Szacillo 2012).

The original Latin phrase describing what so offended St Colmán "palpebre oculorum illius latenter iacinto colore" does not contain the verb paint (pingo). It just says his eyelids were hyacinth (blue) colored. This passage together with the gloss from the Uraicecht Becc implies that there was a custom of tattooing people's eyelids blue in early medieval Ireland. A creccoire* was therefore a professional eyelid tattooer or a tattoo artist.

A possible third reference to tattooing the area around the eye is found in a list of Old Irish kennings. The kenning for the letter 'B' translates as 'Beauty of the eyebrow.' This kenning is glossed with the word crecad/creccad (McManus 1988). Crecad could be translated as cauterizing, branding, or tattooing (eDIL). McManus suggests "adornment (by tattooing) of the eyebrow" as a plausible interpretation of how crecad relates to the beauty of the eyebrow (1988). The precise date of this text is not known (McManus 1988), but Old Irish was used c. 600-900 CE, meaning this text is of a similar date to the other Irish references to tattoos.

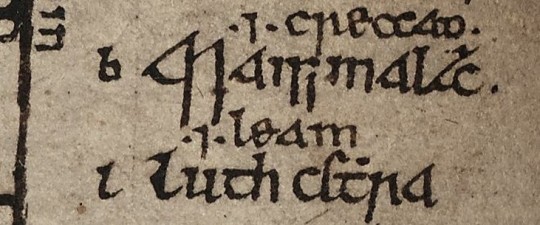

Kenning of the letter 'b' with gloss from TCD MS 1337/1

There is a sharp contrast between the association of tattoos with a venerated figure in 'The Caldron of Poesy', and their association with low-status work and divine punishment in the Uraicecht Becc and the Vita. This indicates that there was a shift in the cultural attitude towards tattoos in Ireland during the 7th-9th centuries. The fact that a Christian saint considered getting tattoos a big enough offense to punish his own brother with blindness suggests that tattooing might have been a pagan practice which gradually got pushed out by the Catholic Church. This timeline is consistent with the 786 CE report of the papal legates condemning the pagan practice of tattooing in Great Britain (MacQuarrie 1997).

There are some mentions of tattooing in Lebor Gabála Érenn, but the information largely appears to be borrowed from Isidore of Seville (MacQuarrie 1997). The fact that the writers of LGE just regurgitated Isidore's meager descriptions of Pictish and Scottish (ie Irish) tattooing without adding any details, such as the designs used or which parts of the body were tattooed, makes me think that Insular tattooing practices had passed out of living memory by the time the book was written in the 11th century.

*There is some etymological controversy over this term. Some have suggested that the Old Irish word for eyelid-tattooer should actually be crechaire. more info Even if this hypothesis is correct, and the scribe who wrote the gloss on creccoire mistook it for crechaire, this doesn't contradict my argument. The scribe clearly believed that eyelid-tattooer belonged on a list of low-status occupations.

Discussion:

Like Julius Cesar in the last post, Herodian of Antioch c. 208 CE makes some dubious claims of Celtic barbarism, stating that the Britons were: "Strangers to clothing, the Britons wear ornaments of iron at their waists and throats; considering iron a symbol of wealth, they value this metal as other barbarians value gold" (translation from MacQuarrie 1997). If the Britons wore nothing but iron jewelry, then why did they have brass torcs and 5,000 objects that look like they're meant to attach to fabric, Herodian?

Brass torc from Lochar Moss, Scotland c. 50-200 CE. Romano-British trumpet brooch from Cumbria c. 75-175 CE. image from the Portable Antiquities Scheme.

Trumpet brooches are a Roman Era artifact invented in Britain, that were probably pinned to people's clothing. more info

Although Herodian and Solinus both make dubious claims, there are enough differences between them to indicate that they had 2 separate sources of information, and one was not just parroting the other. This combined with the fact that we have more-reliable sources from later centuries confirming the existence of tattoos in the British Isles makes it probable that there was at least a grain of truth to their claims of tattooing.

There is a common belief that the name Pict originated from the Latin pictus (painted), because the Picts had 'painted' or tattooed bodies. The Romans first used the name Pict to refer to inhabitants of Britain in 297 CE (Ware 2021), but the first mention of Pictish tattoos came in 402 CE (Carr 2005), and the first explicit statement that the name Pict was derived from the Picts' tattooed bodies came from Isidore of Seville c. 600 CE (MacQuarrie 1997). Unless someone can find an earlier source for this alleged etymology than Isidore, I am extremely skeptical of it.

Summary of the written evidence:

Some time between c. 79 CE (Pliny the Elder) and c. 208 CE (Herodian of Antioch) the practice of body art in Great Britain changed from staining or painting the skin to tattooing. Third century Celtic Briton tattoo designs depicted animals. Pictish tattoos are first mentioned in the 5th century.

The earliest mention of Irish tattoos comes from Isidore of Seville in the early 6th c., but since it seems to have been a pre-Christian practice, it likely started earlier. Irish tattoos of the 8-9th centuries were placed on the area around the eye and on the legs. They were a bluish color. The 8th c. Anglo-Saxons also had tattoos.

Tattooing in Ireland probably ended by the early 10th c., possibly because of Christian condemnation. Exactly when tattooing ended in Great Britain is unclear, but in the 12th c., William of Malmesbury describes it as a thing of the past (MacQuarrie 1997). None of these sources give much detail as to what the tattoos looked like.

The Archaeology of Insular Ink:

In spite of the fact that tattooing was a longer-lasting, more wide-spread practice in the British Isles than body painting, there is less archaeological evidence for it. This may be because the common tools used for tattooing, needles or blades for puncturing the skin, pigments to make the ink, and dishes to hold the ink, all had other common uses in the Middle Ages that could make an archaeologist overlook their use in tattooing. The same needle that was used to sew a tunic could also have been used to tattoo a leg (Carr 2005). A group of small, toothed bronze plates from a Romano-British site at Chalton, Hampshire might have been tattoo chisels (Carr 2005) or they might have been used to make stitching holes in leather (Cunliffe 1977).

Although the pigment used to make tattoos may be difficult to identify at archaeological sites, other lines of evidence might give us an idea of what it was. Although the written sources tell us that Irish tattoos were blue, the popular modern belief that woad was the source of the tattoo pigment is, in my opinion, extremely unlikely for a couple of reasons:

1) Blue pigment from woad doesn't seem to work as tattoo ink. The modern tattoo artists who have tried to use it have found that it burns out of the person's skin, leaving a scar with no trace of blue in it (Lambert 2004).

2) None of the historical sources actually mention tattooing with woad. Julius Cesar and Pliny the Elder mention something that might have been woad, but they were talking about body paint, not tattoos. (see previous post) Isidore of Seville claimed that the Picts were tattooing themselves with "juices squeezed from native plants", but even assuming that Isidore is a reliable source, you can't get blue from woad by just squeezing the juice out of it. In order to get blue out of woad, you have to first steep the leaves, then discard the leaves and add a base like ammonia to the vat (Carr 2005). The resulting dye vat is not something any knowledgeable person would describe as plant juice, so either Isidore had no idea what he was talking about, or he is talking about something other than blue pigment from woad.

In my opinion, the most likely pigment for early Irish and British tattoos is charcoal. Early tattoos found on mummies from Europe and Siberia all contain charcoal and no other colored pigment. These tattoos range in date from c. 3300 BCE (Ötzi the Iceman) to c. 300 CE (Oglakhty grave 4) (Samadelli et al 2015, Pankova 2013).

Despite the fact that charcoal is black, it tends to look blueish when used in tattoos (Pankova 2013). Even modern black ink tattoos that use carbon black pigment (which is effectively a purer form of charcoal) tend to look increasingly blue as they age.

A 17-year-old tattoo in carbon black ink photographed with a swatch of black Sharpie on white printer paper.

The fact that charcoal-based tattoo inks continue to be used today, more than 5,000 years after the first charcoal tattoo was given, shows that charcoal is an effective, relatively safe tattoo pigment, unlike woad. Additionally, charcoal can be easily produced with wood fires, meaning it would have been a readily available material for tattoo artists in the early medieval British Isles. We would need more direct evidence, like a tattooed body from the British Isles, to confirm its use though.

As of June 2024, there have been at least 279 bog bodies* found in the British Isles (Ó Floinn 1995, Turner 1995, Cowie, Picken, Wallace 2011, Giles 2020, BBC 2024), a handful of which have made it into modern museum collections. Unfortunately, tattoos have not been found on any of them. (We don't have a full scientific analysis for the 2023 Bellaghy find yet though.)

*This number includes some finds from fens. It does not include the Cladh Hallan composite mummies.

Tattoos in period art?

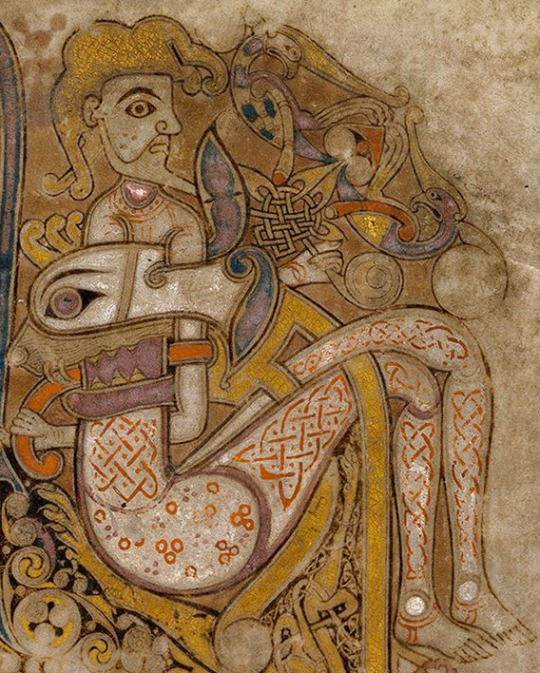

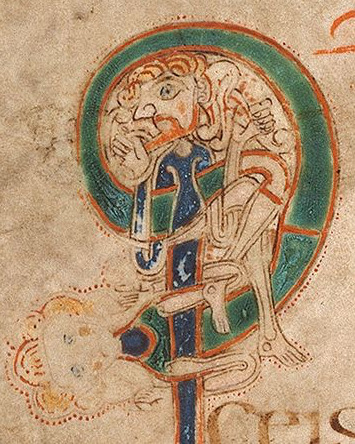

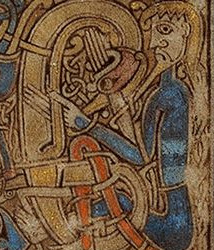

It has been suggested that the man fight a beast on Book of Kells f. 130r may be naked and covered in tattoos (MacQuarrie 1997). However, Dress in Ireland author Mairead Dunlevy interprets this illustration as a man wearing a jacket and trews (Dunlevy 1989). Looking at some of the other figures in the Book of Kells, I agree with Dunlevy. F. 97v shows the same long, fitted sleeves and round neckline. F. 292r has long, fitted leg coverings, presumably trews, and also long sleeves. The interlace and dot motifs on f. 130r's legs may be embroidery. Embroidered garments were a status symbol in early medieval Ireland (Dunlevy 1989).

Left to right: Book of Kells folios 130r, 97v, 292r

A couple of sculptures in County Fermanagh might sport depictions of Irish tattoos. The first, known as the Bishop stone, is in the Killadeas cemetery. It features a carved head with 2 marks on the left side of the face, a double line beside the mouth and a single line below the eye. These lines may represent tattoos.

The second sculpture is the Janus figure on Boa Island. (So named because it has 2 faces; it's not Roman.) It has marks under the right eye and extending from the corner of the left eye that may be tattoos.

I cannot find a definitive date for the Bishop stone head, but it bears a strong resemblance to the nearby White Island church figures. The White Island figures are stylistically dated to the 9th-10th centuries and may come from a church that was destroyed by Vikings in 837 CE (Halpin and Newman 2006, Lowry-Corry 1959). The Janus figure is believed to be Iron Age or early medieval (Halpin and Newman 2006).

Conclusions:

Despite the fact that tattooing as a custom in the British Isles lasted for more than 500 years and was practiced by at least 3 different cultures, written sources remain our only solid evidence for it. With only a dozen sources, some of which probably copied each other, to cover this time span, there are huge gaps in our knowledge. The 4th century Picts may not have had the same tattoo designs, placements or reasons for getting tattooed as the 8th c. Irish or Anglo-Saxons. These sources only give us fragments of information on who got tattooed, where the tattoos were placed, what they looked like, how the tattoos were done, and why people got tattooed. Further complicating our limited information is the fact that most of the text sources come from foreigners and/or people who were prejudiced against tattooing, which calls their accuracy into question.

'The Cauldron of Posey' is one source that provides some detail while not showing prejudice against tattoos. The author of the poem was probably Christian, but the poem appears to have been written at a time when Pagan practices were still tolerated in Ireland. I have a complete translation of the poem along with a longer discussion of religious elements here.

Leave me a tip?

Bibliography:

BBC (2024). Bellaghy bog body: Human remains are 2,000 years old https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-northern-ireland-68092307

Breatnach, L. (1981). The Cauldron of Poesy. Ériu, 32(1981), 45-93. https://www.jstor.org/stable/30007454

Carey, J. (1997). The Three Things Required of a Poet. Ériu, 48(1997), 41-58. https://www.jstor.org/stable/30007956

Carr, Gillian. (2005). Woad, Tattooing and Identity in Later Iron Age and Early Roman Britain. Oxford Journal of Archaeology 24(3), 273–292. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0092.2005.00236.x

Cowie, T., Pickin, J. and Wallace, T. (2011). Bog bodies from Scotland: old finds, new records. Journal of Wetland Archaeology 10(1): 1–45.

Cunliffe, B. (1977) The Romano-British Village at Chalton, Hants. Proceedings of the Hampshire Field Club and Archaeological Society, 33(1977), 45-67.

Dunlevy, Mairead (1989). Dress in Ireland. B. T. Batsford LTD, London.

eDIL s.v. crechad https://dil.ie/12794

Giles, Melanie. (2020). Bog Bodies Face to face with the past. Manchester University Press, Manchester. https://library.oapen.org/viewer/web/viewer.html?file=/bitstream/handle/20.500.12657/46717/9781526150196_fullhl.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

Halpin, A., Newman, C. (2006). Ireland: An Oxford Archaeological Guide to Sites from Earliest Times to AD 1600. Oxford University Press, Oxford. https://archive.org/details/irelandoxfordarc0000halp/page/n3/mode/2up

Hoecherl, M. (2016). Controlling Colours: Function and Meaning of Colour in the British Iron Age. Archaeopress Publishing LTD, Oxford. https://www.google.com/books/edition/Controlling_Colours/WRteEAAAQBAJ?hl=en&gbpv=0

Lambert, S. K. (2004). The Problem of the Woad. Dunsgathan.net. https://dunsgathan.net/essays/woad.htm

Lowry-Corry, D. (1959). A Newly Discovered Statue at the Church on White Island, County Fermanagh. Ulster Journal of Archaeology, 22(1959), 59-66. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20567530

MacQuarrie, Charles. (1997). Insular Celtic tattooing: History, myth and metaphor. Etudes Celtiques, 33, 159-189. https://doi.org/10.3406/ecelt.1997.2117

McManus, D. (1988). Irish Letter-Names and Their Kennings. Ériu, 39(1988), 127-168. https://www.jstor.org/stable/30024135

Ó Floinn, R. (1995). Recent research into Irish bog bodies. In R. C. Turner and R. G. Scaife (eds) Bog Bodies: New Discoveries and New Perspectives (p. 137–45). British Museum Press, London. ISBN: 9780714123059

Pankova, S. (2013). One More Culture with Ancient Tattoo Tradition in Southern Siberia: Tattoos on a Mummy from the Oglakhty Burial Ground, 3rd-4th century AD. Zurich Studies in Archaeology, 9(2013), 75-86.

Samadelli, M., Melisc, M., Miccolic, M., Vigld, E.E., Zinka, A.R. (2015). Complete mapping of the tattoos of the 5300-year-old Tyrolean Iceman. Journal of Cultural Heritage, 16(2015), 753–758.

Story, Joanna (1995). Charlemagne and Northumbria : the in

fluence of Francia on Northumbrian politics in the later eighth and early ninth centuries. [Doctoral Thesis]. Durham University. http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/1460/

Szacillo, J. (2012). Irish hagiography and its dating: a study of the O'Donohue group of Irish saints' lives. [Doctoral Thesis]. Queen's University Belfast.

Turner, R.C. (1995). Resent Research into British Bog Bodies. In R. C. Turner and R. G. Scaife (eds) Bog Bodies: New Discoveries and New Perspectives (p. 221–34). British Museum Press, London. ISBN: 9780714123059

Ware, C. (2021). A Literary Commentary on Panegyrici Latini VI(7) An Oration Delivered Before the Emperor Constantine in Trier, ca. AD 310. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. https://www.google.com/books/edition/A_Literary_Commentary_on_Panegyrici_Lati/oEwMEAAAQBAJ?hl=en&gbpv=0

#early medieval#roman era#pict#tattoos#ancient celts#apologies to people who wanted a shorter post#archaeology#art#anecdotes and observations#statutes and laws#irish history#gaelic ireland#medieval ireland#anglo saxon#insular celts#romano british

119 notes

·

View notes

Text

The topic of Danny Phantom came up in conversation with a coworker and I mentioned I'm active in the fandom, and he asked me what the weirdest thing in the fandom is, so I said the dissection/vivisection fics and then showed him art of Little Baby Man and Diddles Piddles. He was like "yeah that's weird." Stay classy, Phandom.

#anecdotes by peachdoxie#danny phantom#also my library's intern heard us talking and said that she has a friend who observes the phandom on tumblr from a distance#but will infodump to her about it#so hi if you see this i guess#no way to ID who you are lol

456 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tbqh I understand why so many ppl in Healthcare and nursing are hateful malicious hags like I can't condone it but after a 16 hour shift you really lose your grip on what matters. And if ur patient would just do x..-> Then you could get y out of the way. Which means you could finally do z. This of course is no way to treat a human being and god willing this whole system is bound for major reform in a few short decades. None of this is fair to residents or patients or staff and we need to pretty radically reimagine as a society (because people have done some pretty hard and deep imagining at the smaller scale) what "health care" actually means

#In my communist utopia everyone would be forced to be a med student. Just kidding obviously that'd be stupid and bad#Coming off of a few anecdotal observations from today but primarly trying to convince the ER to provide a resident with transportation home#(They can not promise this and are not legally required to)#Being transfered 4 times and with a lot of obvious commotion but also the resident was essentially scolded for#''Treating the ER like a taxi service''. Well I understand u are enormously busy but also she came in w concerns and now cannot get home

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

...I guess zen's in the driving seat now

like for something from zenyatta!

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

i do think it's funny that there are about 5% more people on that poll who selected "i am not queer and i like tommy" than "i am queer (but not a man) and i dislike tommy"

#further evidence for my theory that the BT fandom has more cishets than the buddie side lol#that c/anichangemyblogname guy who wrote paragraphs ranting abt me and hima#one of the things he was mad about was me saying that from my anecdotal observations#there are more cishet women on that side of the fandom#but it would seem i might be correct 🤔#also i did SAY it was anecdotal so idk why he was even mad#i only skimmed his posts about us bc tbh they were way too long for me to read in full#my brain is already too full with smart and coherent takes rooted in a socialist worldview. sorry

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

I think the most depressing thing that’s happened in my life over the past couple of months is watching an otherwise intelligent friend descend into paranoia and conspiracy. maybe ex friend now, because I don’t feel all that inclined to talk to him these days, but it’s still sad to be a bystander to this who can’t help even if you try to intervene.

#something I’ve been trying to get better at as I’ve gotten older is trying to avoid situations that#spurn incredibly strong emotions in me that impair my social function.#it’s not fair to the people around me and it’s not fair to me either. i deserve better than treating myself like that#and I’m starting to wonder if how someone answers ‘how willing am I to pull my own pigtails’ is correlative with extreme paranoia#social behavior isn’t really my bag outside of being in the world and observing it yknow#but a common denominator here has definitely been seeing someone come to this crossroads#and just choosing to engage anyway instead of telling themselves ‘I need to remove myself from being…#…so fired up constantly. it’s starting to boil my brain.’ they just can’t quit it.#the best kind of evidence – white hot anecdote#but there’s something about this that does seem functionally similar to addiction. just in how compulsive it is.#is anger addiction possible? I guess that’s the burning question.

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

You should have seen my therapist’s face when I asked for her birth date, she was like ????

But I really needed to know if she had placements in my 8th house. Turns out her planets fall in my 4th house

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

Guy who has recently read Umineko, reading The Flower that Bloomed Nowhere: Getting a lot of 'Umineko' vibes from this...

#oh youve gone from being an observer to a meta-hero? you have to figure out who/how/whydunnit across time loops?#immediate anecdote about grief and what truth people focus on after death?#aeroplanes talking#umineko#tftbn

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

People say that kids these days behave extra badly but I wonder what the gap is between girls and boys and if there is an increase in a specific type of bad behavior by sex.

#ic.text#like im sure boys are extra misogynistic because of manosphere stuff and it makes me shudder#and although ive seen anecdotes id like to see some survey/study on women who teach#and what they have to say about this particular topic because i feel like a lot of these discussions leave#out these factors and observations and the SA that these teachers face

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

WHY ARE YOU CONSULTING A SOCIAL SCIENTIST ON WHETHER ASTROLOGY COUNTS AS A SCIENCE. WHY DOESN'T ANYONE EVER CONSULT ACTUAL ASTRONOMERS. BECAUSE THEY KNOW THE ANSWER THEY'LL GET THAT'S WHY!!!

#DOES PRECESSION OF THE EQUINOXES MEAN NOTHING TO YOU PEOPLE#THE SUN ISNT EVEN IN YOUR ''SUN SIGN'' IT MEANS NOTHING !!! ITS MEANINGLESS !!!#brot posts#astro posting#'i dont know if i feel comfortable calling astrology a science' BECAUSE IT ISNT#FLAT OUT. ITS NOT.#even ignoring the fact its blatantly falsified#just . the definition of science relying on observations.#hold on let me ltierally get my fucking science research methods textbook#SCIENCE MUST BE. 1. empirical 2. systematic 3. replicable 4. self-correcting#ASTROLOGY. IS NONE OF THOSE THINGS#1. its based entirely on anecdotes 2. again its based entirely on anecdotes theres no institution no system no research#3. BECAUSE its not systematic it sure as fuck cannot be replicable#and in fact it frequently ISNT. the accuracy of astrological predictions varies so wildly from person to person#4. self correcting? well there's no institution and no repeatability and so theres no future research to constantly fact check#prior assumptions and prior research#and also even on individual cases astrologers just double down and find a loophole to work around anything that falsifies their claims#which is literally the number one sign that something is pseudoscience and not science#if you cannot feasibly falsify something without there being ten million loopholes then its just an excuse machine its not real science.#so no. just from the sheer basic definition of science and scientific research. astrology is not science.#nevermind the fact its just. its just not fucking true. nothing it predicts is true#now the OBSERVATIONS behind astrology ie the actual observing of the night sky is a different conversation#but the ASTROLOGY of it - the predictions about human beings - is pseudoscience

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

I try not to be a music snob but sometimes songs come on the radio and I think "how does anyone enjoy listening to this?"

#anecdotes by peachdoxie#this isnt about any specific genre or musician#just an observation made with frustration while im at this doctors appointment#most of it is just stuff where the artist is more speaking on pitch than singing and has a LOT of vocal fry#along with lyrics that i dislike#or are so mumblecore that i can't tell what they're saying

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

To circle back to that ask from a couple days ago about the band becoming mascots - I *do* have a long-term, long-shot theory that the more profit-driven and corporate Gorillaz becomes, the more they're going to push away fans who aren't shippers. Eventually, the shippers are going to be the dominant - perhaps the ONLY - presence in the community. This isn't to say shippers can't also be music fans, gen fans, collectors, art analysts etc, but the shipping/shipping fanservice, imo, makes people a lot more likely to stay attached compared to the people who don't care about any of that. Does this mean a ship *cough2Doccough* might someday be canonized? Probably not. Maybe? It probably depends on how much the demographics shift over the next few phases (it might not...but I also kinda think it will as the fan service becomes more of a focus). It's wild to think about...the double-edged sword of it all. We (2Doc shippers) win, but at the cost of everything the band and characters stood for 🤔

#personals.#I honestly have no supporting evidence#just anecdotal#and inferring based on the patterns I've observes over my time here#but still...it's something I think about as a possible future

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

an incredibly long, draining, at times truly infuriating week spent w my 80 y/o grandma is nearly over.

made all the more difficult because none of the rest of my so-called “family” want anything to do with her, so she feels betrayed and let down on all sides & is incapable of talking about anything for very long without sliding into a tangent about how good things used to be in the past and how awful they are now.

perhaps her modus operandi has always been to find the nearest eldest daughter to terrorise

#I’ve been using this week as a dry run to see what living with her longer term might be like#and I have some concerns as to whether whatever’s wrong with her is the sort of thing that CAN get better over time with company#and a modicum of support#because sometimes I swear to you it seems like she can’t take on new information at all#mostly I observe an abiding terror of everything in the world around her#can’t be fun to live with but like. it’s like the ‘hey dipshit’ comic#motherfucker dude. I have to listen to all 80 chapters of an endless anecdote about a friend of a friend trying to get a refund for a taxi#but if I say something that might even approach making her uncomfortable it’s time to move on quickly!!!!!!#so I don’t know if I could live with all that. albeit it’s a nice place#newsflash: family of immature freaks w psychological issues want interpersonal relationships to be easy#‘no interpersonal work ever please��#bye lol#personal

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

I've be following a few of those "do you know this anime/album/movie" blogs and it really blows my mind how the majority of this site seems to have never interacted with any media produced before 2011

#personal#anecdotal observation and ehat have you#tho I'm always suspect of people who dont consume media from the 70s and earlier

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

I think the movie Serendipity had a special relationship to my parents. I don't remember off the top of my head, but I think it was one of the first films they saw together. So it's a movie with special significance to them. I've never fully paid attention to it, but I've still seen it with them. Now that my mom's dead, I imagine it has even more meaning.

#I do remember Eugene Levy in that movie#He was pretty funny#as he always is#Don't know why I chose to share this now#but this film holds a special significance to my parents#probably moreso now that my mom is dead#serendipity#my thoughts#asd#autism#random observations#neurodivergent#adhd#audhd#anecdote#autistic

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Gilt leather shoes in 16th c. Ireland

Drawing of a 16th c. Irish shoe by A. T. Lucas over a gilt leather wall hanging from the National Museum Machado de Castro in Portugal

In his 1518 description of Irish clothing, Laurent Vital says the following about shoes worn by Irish women and girls:

Elles portent petits soliers à singles semelles, bien jolys et mignotz, ouvrés pardessus d'aultres couleur de cuyr et parfois doretz de cuyr estainnet, comme s'il estoit doré, et comme j'ay veu porter les enffans parcy-devant, quant on leur achetoit des soliers de ducasse. They wear little shoes with single soles, very pretty and cute, finely worked on top with other colors of leather and sometimes adorned with gilt leather, as if they were gilded, like the shoes which were bought for children at fairs in past times. (translation by Dorothy Convery, edited by me)

In this post, I discuss what Laurent Vital meant by gilt leather and how it might have been used in 16th c. Irish shoes.

Sadly, we do not have any surviving examples of gilt leather shoes from medieval or early modern Ireland. This is unsurprising, because gilt leather is a fragile material which can be destroyed by excessive moisture, (Gilt Leather Society 2019) and most surviving Irish shoes have been found in damp locations like bogs, crannogs, and wells (Lucas 1956, Miller 1991, Nicholl 2023).

As Vital points out, although medieval doretz de cuyr or gilt leather looks like gilding, it is not really gold. Gilt leather was made from carefully prepared leather that was sealed with rabbit-skin glue and then had silver foil placed on top of it. The foil was then painted with a yellow varnish, giving it its golden appearance (Pereira 2012). Gilt leather could be stamped with patterns or painted with designs.

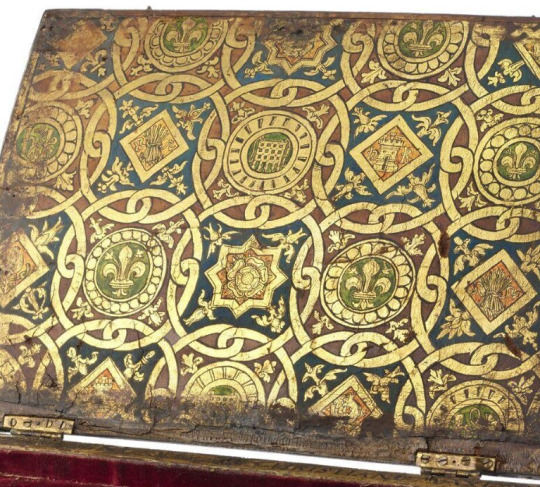

Painted gilt leather on a writing box belonging to King Henry VIII, made circa 1525 Victoria and Albert Museum collection

Learning what gilt leather actually was left me puzzled as to how the Irish made shoes out of it. Early 16th c. Irish shoes were largely made using a turnshoe or turn-welt construction. These methods involve sewing the shoe together inside out and then turning it right side out. In order to turn successfully, the shoe leather needs to be thin and flexible. Turnshoes are typically soaked in water to soften them before they are turned (Miller 1991, Nicholl 2023). I would expect that the layers of rabbit-skin glue and varnish in gilt leather would make the leather too stiff to turn. Also, as previously noted, being soaked with water is bad for gilt leather.

Although there are no surviving Irish examples of gilt leather shoes, there are a few continental European examples of episcopal sandals from the 12-13th centuries which appear to be embellished with gilt leather.

All of these shoes have a base layer of plain leather; the gilt leather is an applique which is glued or stitched on top. This method of construction is consistent with Vital's description that Irish shoes were estainnet i.e. adorned or plated*, with gilt leather. This method also explains how it was possible for Irish shoemakers to make shoes with gilt leather. Turnshoes of plain leather could be appliqued with gilt after they were turned right side out.

*estainnet: modern French étamer: to tin plate or to plate with metal

Irish shoemakers probably used gilt leather that was imported from Spain. During the Middle Ages, gilt leather was made in Spain and Portugal. It was not made elsewhere in Europe until the 17th century. (Pereira 2012). 16th c. Irish merchants imported luxury goods like silk and wine from Spain (Flavin 2011).

Neither Vital's account nor period illustrations give us any idea what kind of designs these Irish gilt shoes had on them. Rinceaux or scrolling foliage motifs like those on the sides of the 16th c. St. Brigid's shoe shrine are a likely option.

Further reading: Robert Gresh of the group Wilde Irish has written an interesting article on evidence for the use of gilt leather in 16th c. Irish armor. Download here

Bibliography:

Dictionnaire du Moyen Français 2020

Flavin, Susan (2011). Consumption and Material Culture in Sixteenth-Century Ireland. [Doctoral thesis]. University of Bristol.

The Gilt Leather Society. (2019). Conservation Challenges. https://giltleathersociety.org/conservation/conservation-challenges/

Lucas, A. T. (1956). Footwear in Ireland. Journal of the County Louth Archaeological Society, 13(4), 309-394. https://www.jstor.org/stable/27728900

Miller, O. G. (1991). Archaeological Investigations at Salterstown, County Londonderry, Northern Ireland. [Doctoral thesis]. University of Pennsylvania.

Nicholl, John (2023). https://broguesandshoes.com/

Pereira, Franklin (2012). Gilt leather/guadameci in Coimbra – comments on documents of the 12th and 16th centuries. Boletim do Arquivo da Universidade de Coimbra, 15, 169-180. http://hdl.handle.net/10316.2/5514

Ryan, Trisha (2022). Online Pop Up Talk: St. Brigid's Shoe Shrine. National Museum of Ireland Archaeology. https://www.museum.ie/en-IE/Museums/Archaeology/Engage-And-Learn/For-Adults/Online-Pop-Up-Talk-St-Brigid-s-Shoe-Shrine

Vital, Laurent (1518). Archduke Ferdinand's visit to Kinsale in Ireland, an extract from Le Premier Voyage de Charles-Quint en Espagne, de 1517 à 1518. http://research.ucc.ie/celt/document/T500000-001

#irish dress#dress history#16th century#gaelic ireland#historical fashion#shoes#historical women's fashion#irish history#brog#anecdotes and observations

7 notes

·

View notes