#Ultimate Anti-climax

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

It’s supposedly to show that Taylor has become no better than Alexandria, willing to do anything if it means “saving humanity.”

Because she’s terrified that literally anyone could be the one Jack interacts with and causes the end of the world. I mean, she would’ve thrown hands with Eidolon because she has absolutely no idea who it could be. (My money was on Taylor, for the record.)

Sparing the baby from eternal torture would be a valid justification, but Taylor thinks that the woman who was undergoing an eternity of torture should have kept her damn mouth shut. So I doubt she was thinking of sparing Aster from that.

I didn't expect the baby shooting to happen so casually. And not much explanation to why. So she wouldn't come under Gray Boy's power? Or maybe there is more I missed or that is coming.

#the ends justify the means#right?#child murder#fiction#Eidolon musta been burning to say who it was#But nooooooo#Let’s not fucking tell anyone so everyone’s caught with their fucking pants down#i get setting it off then might have been the best time#But fuck#Maybe have a PSA ready to go?#Also find it funny that things could’ve ended in about fifteen minutes#Ultimate Anti-climax#Boy would Cauldron’s faces be fucking RED#worm#wildbow#parahumans

50 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hi, hey there, did you know that the whole "Jedi can deflect blasters so Mandalorians used solid-shot weapons to kill them because blocking a bullet with a lightsaber just results in molten metal spraying the Jedi" meme is actually bullshit?

Like, first thing you have to know about that lore is that it was written by Karen Traviss. Traviss is fairly infamous for writing a shitton of military wank and really hating the Jedi, portraying them as cruel, cold, fascist idiots, who are much, much lamer than the cool Mandalorians, who are badass military types and definitely haven't carried out multiple genocides in the past (they have). She was also known for not exactly playing ball with other writers, and ultimately ragequit the franchise when TCW started to include Mandalorians and portrayed them differently. This was not a detail that basically any other writer in anything Star Wars ever actually backs up.

And like, here's the thing... this exists.

That's a Jedi using the Force to deflect bullets with her bare hand.

This is Tutaminis. And/or Force Deflection, it's not really clear whether they're the same thing or not. It's a pretty standard Force ability that a bunch of characters have demonstrated. Obi-Wan blocks both bullets and a flamethrower with it in the 03 Clone Wars microseries. It's how Yoda catches and redirects Force Lightning during his duels with Dooku in Attack of the Clones and Palpatine in Revenge of the Sith. It's how Vader absorbs Han's shots with his hand in The Empire Strikes Back.

It's also evident from the amount of times that the Mandalorians fight the Jedi with normal blasters instead of breaking out their "anti-Jedi" weapons for their ancient enemies. And the fact that the Mandalorians lost their wars against the Jedi.

If solid-shot guns/slugthrowers were the amazing anti-Jedi weapons that totally always worked against Jedi, then we'd see a lot more slugthrowers and a lot fewer Jedi. We see the CIS' Droid armies fight against the Jedi for three years, we see the Clones being designed from the get-go to kill the Jedi at the end of the war and being highly successful at it, we see the Empire hunting Jedi for the next 19 years and the rest of the Galactic Civil War after that, and y'know what they have in common? None of them use slugthrowers. They all just keep using blasters.

The answer to "How to kill a Jedi" equation has traditionally been depicted as "Use more blasters than they can actually physically deflect."

There's also the detail that Jedi are precognitive space wizards who can move with superhuman speed. If you're actually in range to shoot one with a gun, they'll sense you, evade or block with the Force, close the gap before you can chamber the next round, and revoke your Hand Privileges.

Even the "You'll kill them with a spray of molten metal from the melted bullet!" thing doesn't actually track with what we see on-screen. At the climax of Revenge of the Sith, we see Obi-Wan and Vader fight in the middle of an active volcano. They get splashed with showers of lava a couple of times, and at the end of the fight, both of their clothes are scorched and burned from the embers. Obi-Wan continues to wear his charred robes throughout the rest of the movie. And he's fine. No lava burns. Neither of them actually gets hurt by the lava until Obi-Wan cuts Vader's limbs off and he can no longer move or protect himself, and even then, Vader survives getting burned to a crisp by being really fucking mad about it.

So yeah, it's nonsense. A dumb "Hurr, Jedi are so lame and my unproblematic genocidal warrior race could totally kill them super-easy" take written by Star Wars' own version of Ken Penders.

#Star Wars#Jedi#Meta#Yeah sorry the Legends Mandos were pretty much straight-up villains most of the time

559 notes

·

View notes

Text

This was a good read. The first review I've found that isn't all "boo hoo, they put too many cameos in superhero movies these days"

But there is such an intimacy to their combat that "Ha Ha, Wolverine stabbed Deadpool in the junk" feels like a shallow interpretation of the fight scene. Wade names edging as one of his favorite sexual activities, and that's precisely what a fight between Deadpool and Wolverine will always be. No matter how much pain they inflict — they'll never be able to stop the other. They're in a constant game of edging, where fighting is in place of f***ing.

Their most intimate fight takes place within the confines of a Honda Odyssey, as they beat the living piss out of each other immediately after Logan's grounded, dramatic reveal of his tortured past. If this were a romantic drama, it would be a passionate sex scene to break the serious tension that erupts after a character allows another person to see them be vulnerable. But since this is a Deadpool movie, it's a whole lot of slappin' each other around set to the tune of "You're The One That I Want" from "Grease." Sorry, but there's simply no straight explanation for that song choice in this context.

During the film's climax, Deadpool and Wolverine join forces in the ultimate bromance handshake, but the force of anti-matter and matter (a joke on Deadpool and Wolverine's perceived respective importance) is so strong that Wolverine's yellow suit explodes off of him to reveal Hugh Jackman's physique that makes him look like a Tom of Finland drawing.

Matter and anti-matter. I swear to god, this movie has Layers.

106 notes

·

View notes

Note

I don't know if you were asked this before or already addressed it before, but what do you think of the argument that Belos' death was supposed to be anticlimatic

See, the problem with these arguments is that it assumes that people who were disappointed with Belos' death wanted a grand, epic battle when in reality, everyone that I've spoken to wanted him to suffer more. We wanted him to go out screaming, realizing that all he did for centuries was for nothing, since that was what the previous episodes were building up to. That's not grandiose, that's even more pathetic than what we got in canon.

Belos' death is anti-climactic because for two episodes, the show was expanding on his background, making him see ghosts or hallucinations, lashing out at the idea of being wrong when he sees "Caleb," all of this suggested that this would play into his ultimate undoing. Instead, we get Luz-With-Anime-Powers yank him off the Titan heart and then he melts in the rain. Cool.

What was the point of the previous episodes then?

Anti-climaxes can work if there is a point to them, be it comedic or tragic. But there was no point to how Belos died. Luz didn't need to learn anything about herself in order to earn the Titan powers, she didn't use anything she learned about the Wittebanes against Belos in the final battle, all that happened is that the Titan told her she's a good witch and to stop comparing herself to someone Obviously Evil like Belos. Great character moment there.

Hell, nothing about Belos played in his death. Not his backstory. None of his lies. Nothing. It just happens. Giving a megalomaniac an undignified death or defeat can work though. Just look at Ozai. He built himself as the Supreme Ruler of the World, as the Phoenix King. He sees himself superior to all others and uses everyone--even his own children as pawns. So to have him be defeated by the Avatar, by an Air Nomad child, who doesn't even give him the dignity of killing him in battle but by taking away the ultimate symbol of his power, his bending, works because it's the antithesis of everything Ozai believes in.

But Belos' death has nothing to do with him as a character or his beliefs. The idea that he needs an undignified death to bring down the megalomaniac doesn't work because Belos has suffered nothing but indignities since he got slammed into a wall. He's been dying for several episodes, lost his human form and the world he knew and loved is long gone and none of this is used against him in the final episode.

In fact, Belos' death actually supports his ideology: for centuries, he's believed that witches are evil and inferior to humans. And he justified all the evil he's done in the name of the greater good: of defeating what he saw as evil. So, picture the scene, you have a rapidly dying man who is no longer a threat to anyone, who is trying to reach out to the one person he thinks is moral by virtue of her species, only to be stomped on by beings who proudly proclaim that they are in fact, immoral.

Congrats gang. You just let the evil bigot die with his feelings justified.

Even how he died doesn't make narrative sense because we've seen him rebuild himself from a droplet and King even mentions some being stuck between his toes. How is it this fight is what finishes him off for good? He's both progressively weaker in each episode and yet is able to outrun (or out crawl) both the Hexsquad after entering the portal and Raine in the castle and possess the Titan heart. Plus, despite having possessed the literal Titan's heart, that equated to having just enough power to transform into his younger self and then get melted by the rain. Ok then.

So let's say that Belos' death works for meta reasons; that evil and bigotry should be given anticlimactic deaths. Ok fine, but it's still disappointing and boring af to watch. Giving a bigoted villain a gruesome, over the top, and entertaining death doesn't mean you suddenly validate the villain's ideals, just look at Raiders of the Lost Ark and its melting Nazis.

Also, unpopular opinion, but The Owl House is not about bigotry; it doesn't say anything about where it comes from, what perpetuates it, how people fall into it, how it can be stopped, etc. The writing is too inconsistent and the world building is too flat for any kind of deep or compelling themes. Instead, it has the grotesquely simplistic idea that "Bad Man Cause Bad Things. Get Rid of Bad Man and Bad Things Go Away."

And that's ultimately why Belos' death doesn't work; because The Owl House never had anything deep to say. It's a fun, escapist fantasy that wants to have deeper themes but can't commit to them. Anything "real" a person might interpret is largely projection because the show is too ineffectual in exploring its own world building and characterization beyond surface level meanings.

#the owl house#toh critical#toh criticism#emperor belos#philip wittebane#asks#long post#belosfanstakeover

117 notes

·

View notes

Note

hi!!! i'm new to tvc and your blog so im not sure if this has been done yet but :'D i just wanted to ask your thoughts on akasha, even generally speaking? thanks!

Welcome!!! I have lots of thoughts on Akasha, but mainly I think her existence tells us a lot about the author and provides a lot of context for how AR approaches female characters in the series overall. I think Akasha, Claudia, and Gabrielle are a very succinct look at how Anne viewed women and the archetypes she felt existed within womanhood. Akasha is really the final boss of anti-feminist strawmen, written to be the ultimate evil and Bad Woman, but she just kind of ends up being an almost-compelling female character instead.

I think Gabrielle has strong elements of that, but the fact that she was so heavily inspired by AR's mother softens the narrative to her some despite the bitterness there. Akasha is something else though, and the narrative on a meta level does not seem to feel sympathy for her.

AR obviously had a very complicated relationship with her own womanhood and a virtually unshakable "not like other girls" mentality her entire life. It was some truly breathtaking internalized misogyny or maybe even a case of gender dysphoria that turned toxic. I doubt we'll ever know for sure, but that loathing she seemed to feel towards womanhood is very much on display in QotD.

Looking at the book as a female reader, I can't help but feel sorry for Akasha on some fundamental level despite the absolute evil she also commits. She was a queen, but doomed to be subservient to her husband on the basis of gender. Then, through some incredible accident, she's suddenly the most powerful human being there's even been, only to then be tortured and spend thousands of years internally conscious but unable to move, speak, or do anything at all.

It's almost an Eve story, a woman who is designed to be a man's inferior who instead seized knowledge and power (and the narrative), gained autonomy from and influence over her male counterpart, and then was punished for it by the larger forces at play. In some ways she reminds me of Claudia too, driven insane by her circumstances and unable to comprehend her own monstrosity, but she's also more evil than Claudia was ever capable of being due to her age (torturing and ordering the rape of of Maharet and Mekare, forcibly turning Khayman, etc).

If Anne had left it at that and changed her goals to be less grandiose, I think her character would have read better and been a more complex and convincing villain in the evil-but-a-victim-of-circumstance way that so many VC vampires are. That's one of my favorite things about the original VC vampires that was present in Akasha but not executed with quite enough finesse. Instead, I think Anne takes it way too far into cartoonish hatred for feminist stereotypes.

For most authors I wouldn't feel confident saying that was the intention but AR, if nothing else, aggressively involves her personal feelings and beliefs in her work, often to the detriment of the story. VC is just the fictionalized inside of her head and we know that. Combined with her other female characters and her own public statements, it's hard not to eye roll at the climax of QotD when Akasha decides she's going to kill 90% of human men and turn the Earth into a new Eden with her as the goddess for the human women (and male human chattel).

In that sense of her character, it seems like foreshadowing to Blood Canticle Lestat reprimanding the audience directly, just Anne finding something to be irrationally angry about and writing it into her book. I've said before that QotD is a step below IWTV and TVL because the cracks in her writing really start to drag the book down like they would for the rest of the series to a rather extreme degree. Knowing this was her last book with an editor, I'm curious how much of the overall readability of the book can be attributed to that/how far gone Anne already was at this point.

In spite of all that, it is kind of fun to go balls to the wall and take a Hell Yeah Get Them mentality when Akasha goes scorched earth because despite it all, it's sort of cathartic to watch a overpowered female vampire go on the warpath and scream all the deepest frustrations with patriarchy that many women struggle with. At the same time, it's hard to fully enjoy it knowing authorial intent (and reading it all within the context of the sexual violence Akasha perpetrated with Anne's usual lack of nuance). That's kind of par for the course though, most things in VC are Almost Good and that's what keeps us on the hook.

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

Okay.

I don't often gush about movies on this blog. Hell, I don't often go to the movies anymore. I just don't have the attention span for it. And I honestly was going to give this one a miss until someone who's opinion I trust was adamant that I needed to see this film right now on the biggest screen possible while I still had the chance. So, FOMO out won over, and I went to go see Godzilla Minus One in Imax.

...

Look, I've been a Godzilla fan practically all my life. My family used to rent those old english dubs of the films on VHS from Blockbuster in the early nineties. I grew up with these monsters. But I have to admit, I've never seen the original, nor have I seen Shin Godzilla. To me, Godzilla is about one thing and one thing only.

Fuck.

Yeah.

Gimme the big monsters just going HAM on each other. Rubber suits, CGI, I don't care! I want the big boys with beef to beef with a large side of cheese!

I guess that's why Godzilla 2014 ultimately left me feeling kind of cold while I absolutely loved KOTM despite how stupid a lot of it was. I just want my big monsters absolutely wrecking shit.

This was different. I knew it was going to be different. A remake of the original Godzilla, this time from the viewpoint of the common citizens still trying to get their lives together after WW2? I knew I was in for some heavy drama.

What I didn't expect was one of the most amazing theater experience I have ever had.

And I'm not just saying that because the movie is good, even though it is.

I'm not just saying that because the movie is great, even though it is.

I'm not just saying that because it's a goddamn masterpiece, even though it is.

I'm saying that because it's about as close to perfect of a film as you can get, and not just of a Godzilla movie, but just as a movie!

Like, it's a running joke that you can cut the human characters out of any Godzilla movie. Here, you could cut Godzilla out and still have a great movie. That's how good the human side of things was.

Like, you really grow attached to these people who have literally lost everything. You grow invested in their struggles, in their relationships, in their baggage, in their love for one another. You come to care about them and are genuinely happy as they eke out a new life after having their homes literally blown to bits. You just want to see them succeed and be happy together.

And that's when Godzilla shows up.

This movie is called Godzilla Minus One in reference to how post-war Japan was basically a Zero Society, left devastated by the conflict. And these people who literally were left with nothing suddenly find even that ripped away as an enormous monster just starts rampaging through the recovering cities.

And this time, Godzilla isn't an avenging hero. He's not a destructive anti-hero. He's not a fun mascot. He's not even a poor, suffering monster unaware of the destruction that he's wreaking. This Godzilla is goddamn menace, an outright monster that is absolutely terrifying. He wants to crush, kill, and destroy. This is Godzilla at his most actively malicious, and all you can do is gape up in horror with these people that you've come to care so much about, wondering how in the hell are they supposed to deal with this!

I won't give away how the day is eventually saved, only to say that it is a masterclass of character-driven suspense and emotion. You honestly come to root for the humans for once. You want to see them succeed, and are genuinely in fear for their lives. No exaggeration, I had my heart in my throat and tears in my eyes all throughout the climax. I don't cry during movies, and this movie made me sob like a baby. It was that good.

And it also had so much to say! Not only about Japan's collective trauma following the nuclear bombs or the other bombing raids like the original, but also about how the Japanese government dehumanized its own people during the war, treating them as expendable resources to fuel the war machine. The main character is a freaking kamikaze pilot who lost his nerve and abandoned his mission, and that plus another act of what he saw as cowardice haunts him throughout the movie, and while it realistically shows how such a person would be treated like a pariah by his former friends and neighbors, it is nothing but sympathetic toward him. He blames himself constantly, but the narrative never seems to.

And there's just this wonderful moment near the end, when it's clear that the government isn't coming to the rescue, so it's up to the common man to band together and find a solution, when a few men leave the mission for fear of their lives and that of their families, and are not condemned for it. And the scientist spearheading the whole thing gives this lovely little speech about how carelessly life has been treated during the war, from the kamikazes to the poorly maintained supply chains to how the common folk were left to fend for themselves, and he hopes to just once be able to secure a win that doesn't sacrifice any more lives. Wow.

I know it's probably too late for anyone else to see it, because I'm pretty sure it's theatrical run ends today. I just wanted to get this review off my chest, because wow, this was the best movie I've seen all year. What a goddamn masterpiece.

134 notes

·

View notes

Note

Have yoh written about crknenberg’s crash / baudrillard’s passage about ballard’s novel

no... i did enjoy elements of the film but i also think ballard and baudrillard both took fairly reactionary stances toward technology as part of their respective understandings of alienation lol. i mean ballard's work displays much more bi-polarity of techno-dystopia and -utopia, and baudrillard situated his critique using nominally anti-capitalist ideas, but both of them ultimately have a similar problem imo of not distinguishing between the effects of capitalism as mediated by technology, and the effects of technology in itself. so a lot of what works about cronenberg's crash is also what's irritating about ballard—like, the sexual drama really hinges on the idea that alienation is a condition of technological overload. in one sense ballard quite clearly writes about capitalism—the techno-landscapes he describes are highways, concrete, housing developments—but i've never read anything from him that seems to realise this.

without weighing in on "is crash a cautionary tale" (locked by a moderator after 12,367 pages of heated debate) it's certainly fair to point out that the trajectory in both ballard's novel and cronenberg's film is inexorably toward escalation of the techno-climax of the car crash—ie, ultimately toward death. also, the novel and film are pretty openly invoking disability and transfemininity as markers of danger, perversion, social sickness, &c: they are figured as the products of a fetish, and the fetish in turn arises as the only way the characters can seek connection or catharsis with one another in a world of artifice. baudrillard, again, is unlike ballard in that he does place his critique broadly within an analysis of economic relations, but i think he's kind of bad at doing this and he's also generally more interested in the affective or psychological effects of simulation than he is in interrogating how it arises or making the actual economic critique that should be underlying. mostly i think of ballard and baudrillard both as like... sometimes hitting on a really effective description of certain affective experiences but also generally failing to theorise these experiences in any serious or productive way.

it has been a while since i read simulacra and simulation though so this may be a bit unfair to baudrillard lol

58 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rewatching s5, I realized why Claudia HAD to lose. And no, it wasn't because it's the heroes who have to set Aaravos free, but because Claudia needs to hit rock bottom and fully transition into a villain before Aaravos gets out.

This is because Callum and Claudia's character arcs have largely been oppositional to one another. Every step of the story, her downfall parallels Callum's rise as a hero - their character journeys are direct inverses. Callum the ascending hero who defeats his inner demons; Claudia the fallen hero who lets her demons consume her:

Callum takes the Sky primal stone, which leads him to realizing he's a mage. But in taking the primal stone, this pushes Claudia to rely exclusively on dark magic.

Callum then learns the Sky Arcanum and rejects dark magic. Meanwhile, Claudia delves deeper in dark magic, changing her hair color for the first time.

Callum learns to create mage wings, solidifying himself as a powerful Sky mage. Claudia, meanwhile, embraces more powerful dark magic, discoloring half her hair in the process.

Callum adopts Ibis' staff, the mage who Claudia fought nearly to the death.

Callum learns the Ocean Arcanum while Claudia transforms herself into a sea creature. Callum then steals her potion which prevents her from healing her leg and releasing Aaravos, leading to...

...where we see the characters in the s6 teaser. While Claudia descends into further dark magic depths, Callum begins to embrace ever higher forms of primal magic (potentially deep magic). The fact that the only new s6 content focuses primarily on the two of them is significant.

And that's the kicker here. While Claudia has done questionable things in the name of family, she was still more of an anti-hero than a villain because she was also tethered by them. And that's why she couldn't free Aaravos yet, as her motivation for doing so (to save her father) was sympathetic, and she was also seemingly ignorant of his actual nature.

But now that she's hit rock bottom with nothing to lose, we may now finally start to see a more villainous, vengeful side of Claudia. Now, she might free him not to save her dad, but to get revenge on the people who let him die. In the end, she becomes the figure who perpetuates the cycle of violence. Not out of misguided necessity as before, but for revenge. This cements her choice to perpetuate violence, contrasting Callum. That is the kind of person Claudia needs to be before she sets Aaravos free - a villain.

If anything, this means that Claudia and not Callum still must be the one to free Aaravos. Not only is it the culmination of her journey so far, Callum is - meanwhile - moving completely in a thematically different direction to Claudia. He is learning to embrace deeper forms of magic, wrestling with but ultimately overcoming his flaws.

The story necessitates this choice - Callum overcomes flaws embracing deeper magic, while Claudia's fall culminates in perpetuating violence. She must release Aaravos, not through self-deception, but embracing the darkness within. Only then will both characters' arcs achieve their heroic - and tragic - climax.

77 notes

·

View notes

Text

So these are just memory-based, impromptu thoughts but I want to write them down as a starting point for when I'll finally write about Julia Wright and Jesse Turner.

I've said that I don't really like the general vibe of S14 regarding Jack because I feel like the story heavily relies on a false dichotomy that I don't personally find compelling. I'm talking about the trite "good vs evil"/"nature vs nurture" dilemma. The presence of evil is posited as an unquestionable presence while good is only present via its absence. By paralleling Jack with Nick the story implies that Jack is both evil by default (because of Lucifer's influence) and he can't do anything about it because he ultimately depletes his soul, the last symbol of human choice, to help his family out and to fix his mistakes.

Jack's story reaches its climax when he accidentally kills Mary and Cas says that what happened was due to "the absence of good". I think that it's a good summary of the whole season.

I'm absolutely not advocating for a real "good vs evil" dichotomy because that would be even more boring, but I just want to point out the unfairness of it all and how it flattens Jack out as a character: if you tell me that he's evil from the start but you also remove that one thing that could've created real conflict then you're basically saying that this character cannot change. And if he cannot change how should we understand his story? Or, to be more honest, how should we find it interesting?

So, of course, I've tried another way.

Although I still stand by all this, I also have to admit that not only does Jack tick all the items off the "Evil/Monstrous Child" trope list but he also happens to be a good Antichrist figure. In a way, he couldn't "only" be a Nephilim, he also had to be inherently connected with Lucifer and The Evil because he was written, I think, having in mind a conflation of the lore about the Antichrist, the Nephilims and their respective connections to the biblical/christian concept of World Ending.

So this got me thinking about all the ways in which Jack's an Antichrist figure and how it relates to the Alternate World where Apocalypse did very much happen. Not only does he help fighting that specific war but his birth is also precisely what opens the rift to a world where Apocalypse is sort of an on-going thing.

I was deep into my musings and speculations when I realized that, while this justification serves to make Jack a more distinct character, more disentangled from his father'/family' s looming presence and with his own individual attributes, it still doesn't free him from the comparison with another character: Christ.

For all its creative usage of God, SPN has always been careful when it comes to the other son of God, at least according to Christianity. Apart from the archangels and the angels, in the world of SPN God's son is the one&only Lucifer.

I don't know how to interpret this but even if I want to see Jack in this light I'm still not free from the above-mentioned false dichotomy: the "anti" part of "Antichrist" is very clear and very present, thank you very much, however, it's the Christ part that's still... absent.

If the absence of good left Jack to face his only other alternative (the certainty of evil), the absence of Christ leaves Jack with the only possible choice: he has to become Christ as well. This puts Jack in the uncomfortable position of being both the Antichrist and the Christ in a way that doesn't result in a unity between two antithetic parts but as a way to sacrifice what he certainly is (the Antichrist) for who he is not (Christ).

The moment Jack "chooses" to save humanity he's actually going against the very reason he was brought into the world for: to end it. This should settle the issue, right? Jack is actually free to choose? Well, I don't know.

For the narrative Jack can only be either Lucifer or Christ: the first is Bad and Sure, the second is Good but Absent so in order to be good, to make good present and manifest, Jack must kill who the story tells us from the start that he must be, someone who cannot change: in other words, in order to be good Jack must be willing to sacrifice his (supposedly) Evil Self, he "must" kill himself.

I feel like, although in different terms, this is the same route the show went with Dean and, as you probably know, I find that route very problematic.

#i have no idea where i'm going with this nor if this is correct fact-wise so don't take me too seriously#but i must start writing about julia wright and jack and kelly and jesse#i have to start somewhere#let's see how it goes and if it goes#jack kline#spn#supernatural#jack the puer#b/w spn#julia wright spn#jesse spn#lucifer spn#tram thoughts

6 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

Metroid Other M Part 8: The hallow ending

You know...I’ve noticed that Sakamoto’s Metroid games seem to have issues in regards to their endings

With the exception of Super, most of his other games tend to have some sort of weirdness to them. Fusion’s ending is too abrupt, with the AI turning good on a whim simply because Samus just happened to pronounce the magic word by accident, which effectively resolved the X-threat right then and there. Zero Mission ends on a bit of an anti-climax due to the added stealth section ending with a fight against a random Ridley robot. Samus Returns’ Ridley fight is wholly unneeded and goes against the feel of the original Metroid 2. Dread’s ending is clearly rushed with Raven Beak pretty much just dumping a truck load of exposition at you with little explanation.

But none of them even comes remotely close to the absolute train wreck that is Other M’s ending

So let’s run this shit by the order in which it happens shall we?

So Samus fights and kills a Metroid Queen that Madeline sicks on her. Y’know what? This is actually the one useful thing that Samus does in this entire game: had she not taken care of this thing, MB may have used it to eliminate the Federation guys that had just arrived, including Anthony. So yeah, after all this time, Samus does one useful thing

She kills a walking plothole

Why is there a Queen on the Bottle Ship? It had been long established, since at least Fusion, that Metroids are only capable of evolving into their mature forms when they are raised in the environment of their homeworld SR388, which is why the BSL had a whole Sector dedicated to imitating that place, as ADAM explained. The Bottle Ship was not modelled after SR388, in fact Samus compares it more to Zebes. Now to be as fair as possible: Fusion never outright states that Metroids ABSOLUTELY need their homeworld to evolve, ADAM could’ve just meant that it was more ideal and easier. However whatever the initial intentions may have been that’s not what the series ultimately went with, as the Prime games feature Metroids evolving into different subspecies, such as the Tallon Metroids, as explicitly demonstrated by that one room on the Pirate Homeworld in Prime 3, which featured autopsies of Metroids of various origins. Normally I’d say that the two subseries should be kept relatively seperate so as to not create any clashings, but in this case the Prime games simply evolved a concept already hinted at in a 2D game, so in the interest of continuity Other M should’ve kept this into consideration. I mean this didn’t need to be a Metroid Queen, its narrative role could’ve easily been fulfilled by just any other big monster, it’s only a Queen because fanservice and nothing else. We lost continuity due to dumb fanservice and now Samus’ most substantial contribution to this plot is getting rid of a plothole. Just great.

MB is the mastermind behind it all! So now the game enters full movie mode in order to quickly explain to me her generic backstory just before she’s killed off so that I can feel sorry for her. Samus’ narration during the ending is flat out laughable, she’s literally explaining to us why we should feel sorry for MB and how her character worked because the story itself could not be arsed to.

This doesn’t work for so many reasons, first of all being that MB’s backstory is built on some impressive levels of stupidity and unclear logistics. These dumb asshole scientists created an AI based on Mother Brains. MOTHER. BRAIN. The AI infamous for betraying her creators and trying to conquer the galaxy. You base your AI on that thing’s “thought patterns”, put her in charge of your station’s Metroids and other highly dangerous creatures, take absolutely no precautions whatsoever, and then you go full surprised Pikachu face when she starts to grow independent? And then when you decide to reprogram her you do it by trying to forcefully restrain her when you know her android body is stronger than normal humans and can telepathically order every creature on the station to rip you to shreds? I’ve seen time travelling demons with Deviantart-level designs with better layed out plans than this!!

We are not informed about MB’s personality in any way whatsoever, aside from her developing a daughter-mother bond with Madeline. She has literally no personality beyond that. Which was also the case with Mother Brain, but at least past games never waxed poetry about how deep the characrer was and why I should be feeling bad for her! The best thing I can say about MB is that her tricking Samus into walking to her death in Sector Zero was actually pretty smart, but that’s it. That’s all there is to her. She’s a fucking muppet otherwise, which is pretty funny, given that her “developing emotions” was the crux that started this whole shitshow in the first place

I must also ask: how DID they analyze Mother Brain’s “thought patterns” to create MB? Mother Brain was a literal brain in a jar who never left Zebes. Sure the Federation was aware of her existence, so I guess she must’ve come into contact with them in the past I...guess through telepathy? Crossing galactic distances? Whatever.

And of course Samus doesn’t even take her down. No that honor goes to Madeline and the GF troops, followed by Anthony being revealed alive and as the one who previously stopped the engines of the station and is now allowing Madeline to be brought in for questioning. I mean why should Samus even do anything after all? She’s just an outsider as Adam put it at the start of the game: all this shit that’s been going on isn’t her story, it’s Adam and his men’s!

Oh and, just to put this here real quick, it’s sometimes said that the japanese version makes a distinction between the broader Galactif Federation and the guys behind the scenes here, who are supposed to be part of the Army, which is absent in the English version...except that’s not true. The English script certainly uses the terms “Galactic Federation” and “Galactic Army” pretty interexchangeably, but the distinction is there, especially with Adam flat out calling these guys a group of Ringleaders, saying that the broader GF was indeed contemplating making Metroids but that Adam conviced them otherwise with the exception of these guys, so the whole “the Galactic Federation as a whole is not corrupt, only a select few members are” idea has always been there in every version of the script. I’m more interested in knowing if this idea also existed in Fusion and was already a thing back then or if it’s a retcon that Other M came up with as a way to justify Samus still working with the GF in later games like Dread.

Anyway the day is saved! The villain was anti-climactically disposed of! Adam was a dick head to the end and died uselessly! Samus seems to have gotten over her issues for some reason, but hey if she’s happy then who am I to complain right?

Unfortunately we’re not quite done yet. We still have a little bit left before it’s truly over

6 notes

·

View notes

Note

I’m not too well versed in the comics history, Has there been clear progress made for mutant rights and acceptance in the marvel universe? Like , between the big events and Orchises of the marvel (and real world) setting things back, is there a big difference with how mutants are treated de facto and dejure across the decades since the 60s? Any particular mutant rights milestones?

Great question!

People's History of the Marvel Universe, Week 22: Anti-Mutant Prejudice and Mutant Rights In the Longue Durée

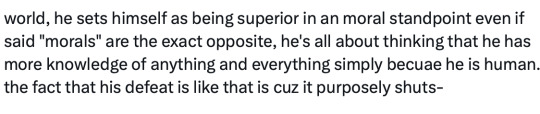

This is a difficult question to answer, because Chris Claremont was very much of the "torture your darlings" school of comics writing, believing that the way to wring endless drama out of your characters was to keep piling tragedy on tragedy on top of them before finally giving them a moment of catharsis. This was especially true for how he handled the mutant metaphor from as far back as X-Men #99, where even when the X-Men saved the day, it would only seem to further fan the flames of anti-mutant prejudice.

That being said, Claremont didn't present an unchanging portrait of anti-mutant prejudice constantly getting worse and worse - after all, the very beating heart of dramatic structure is variation, without which even the most grimdark tragedy becomes numbing and monotonous. So there are definitely key moments in the Claremont run where the X-Men are able to score a victory for mutantkind.

Perhaps the first and most famous instance of the mutants notching a win comes in the climax of God Loves, Man Kills - Claremont's first great Statement Comic about bigotry. After having foiled the Reverend Stryker's plans to exterminate mutantkind by kidnapping Charles Xavier and using a Cerebro-like device to project lethal strokes into mutant brains across the world, the X-Men confront Stryker on live T.V - again, part of Chris Claremont's endless fascination with the power of media to shape our minds that would recur in Fall of the Mutants - fighting him on the level of ideology and rhetoric. Kitty Pryde is able to bait Stryker into attempted murder in front of the television cameras, ending his crusade of hate:

(I'll do a full in-depth analysis of God Loves, Man Kills and how it both codifies and reveals Chris Claremont's approach to the mutant metaphor in a future issue of PHOMU.)

The next big moment of victory I've already written about in PHOMU Week 20, was Fall of the Mutants. In this storyline, the X-Men face off against Freedom Force and the Registration Act and ultimately sacrifice their lives to save the world in Dallas - once again, using the power of rhetoric and media to strike back against discrimination and oppression.

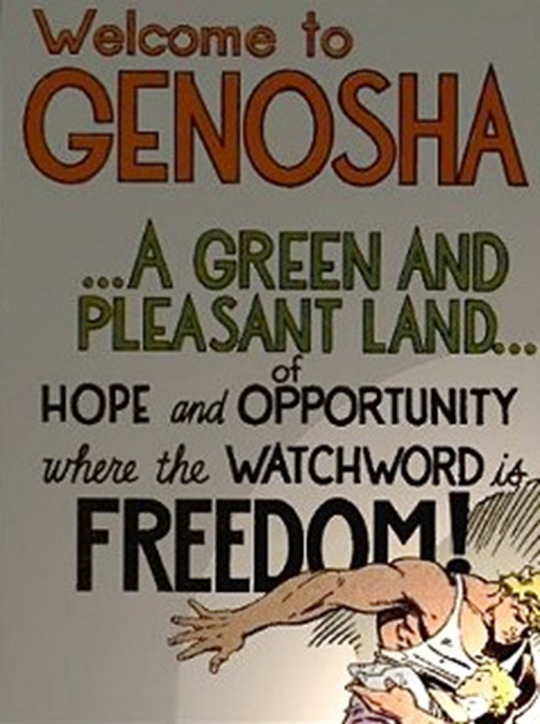

After that, Claremont's next (and arguably last) big victory for mutant rights came in the "Genoshan Saga." (I'll also be doing an in-depth analysis of Genosha in a future issue of PHOMU.) Beginning in UXM #235 and winding its way through Inferno and the X-Tinction Agenda, the fictional nation of Genosha was Chris Claremont's big Statement about apartheid South Africa. An island nation off the east coast of Africa, Genosha seems to be a utopia free of poverty, crime, and disease - but its entire society rests on a foundation of mutant slavery, where mutants are press-ganged, mind-controlled, and genetically-manipulated to serve the human ruling class.

After a series of clashes between the X-Men and the Genoshan Magistrates, the X-Men defeat Genosha's anti-mutant military and their cyborg ally Cameron Hodge. But whereas most superhero comics end with the heroes foiling the evil plan of the supervillain and restoring the status quo, this time Chris Claremont and Louise Simonson went a step beyond the norm and had the X-Men carry out a political revolution that brings lasting structural change - toppling the Genoshan government and abolishing apartheid.

Under the pen of later writers like Joe Pruett, Fabien Nicieza, and (most enduringly) Grant Morrison, the island of Genosha would be refashioned as a mutant homeland, a prosperous and advanced nation of sixteen million mutants ruled by Magneto. (Yet again, a topic for another issue of PHOMU.) Arguably ever since then, the story of the X-Men has been the story of the struggle to restore mutantkind to the position it was in before Cassandra Nova ended the first mutant nation-state, culminating in HOXPOX and the foundation of Krakoa. (A topic we'll be covering next year when FOTHOX/ROTPOX writes the final chapter in the Krakoan Era.)

#xmen#xmen meta#people's history of the marvel universe#the mutant metaphor#chris claremont#the claremont run#grant morrison#brian michael bendis#jonathan hickman#louise simonson

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

jjk 265

In the end the ultimate technique to end sukuna's whole career was the same one that ended gojo, yuji sent him to a public transportation hub. I'm still disappointed sukuna hasn't killed and or eaten more characters. Tomas the Tank Engine about to shred sukuna, isekai'd and reincarnated into a jrpg world as like a baguette or something.

Real twin vibes this chapter with the banter like the crayfish. Sukuna making up excuses for knowing what a hydrangea because Yuji's mocking him about it, bro's a poetry snob and traditional Japanese poetry is all about nature and flowers, he's cultured, a contrast to Yuji's typical teenager action movies and manga tastes. Yuji's arms are back to how they were before and his hair is down again, is this how he sees himself? His eyes for most of the chapter have the single pupil but at the end where he downs down the ultimatum of get back in his body or die, Yuuji's eyes have the same rings as Sukuna's. Two worsties wandering an empty city, I love the vibes of 265. Sukuna is having the worst day of his life being forced to follow Yuuji around while he prattles on about his childhood memories while not being able to commit violence. Sukuna's just simmering there in anger and hatred without being able to vent it as violence all he can do is make snippy comments here and there and insult Yuji. Also my religious iconography isn't too good but is that Kannon/Guanyin when Sukuna questions is this whole chapter has been Yuji's mercy/compassion?

https://tcbscans.me/chapters/7778/jujutsu-kaisen-chapter-265

Someone on reddit brought up how jjk's delulu brother sequences with Todo and Choso previously shown might have actually been a result of Yuji's soul resonance abilities since Yuji is shown to be able to affect souls. And so in a way Todo's false memories of going to a normal school together with Yuji and Choso's false memories of all the Death Painting siblings eating together foreshadowed 265 where Yuji shows Sukuna the town he grew up in. As for why this didn't happen with Sukuna earlier, a lot of it is probably narrative and thematic flow, it's rather fitting that it happens at the climax of the manga. Sukuna and Yuji have always been kinda special. For most of the manga there's also been a significant power gap between them. Yuji was never powerful enough to effect Sukuna, until Yuji got his offscreen power ups and sorcerers threw themselves at Sukuna for 40 chapters straight to wear him down.

Yuji talks a lot of his grandpa the most important person in his life. He wonders if his grandpa would have died alone if his friend hadn't died first. Just like how his grandpa was sick, bedridden and alone, everyone's lives have meaning. It isn't about how someone dies but how they lived.

In 265 Yuji has stopped forcing himself into a role resigning himself to being a cog in a machine. He also reflects and discards his literal interpretation of his grandfather's dying wish, the thing he had been clinging to to guide him lost and directionless as he was in life after his grandpa's passing, realizing that that was an excuse he used for his anger. And this is the part I'm unsure of I think what Yuji's saying is that the value of life in in the acting of living itself and the ways your life touches others. Comparing the translations I think it's an existence proceeds essence answer Yuji's saying it's not memories and the past that determine value and a person's purpose, instead through living and creating memories that value is created, pretty Buddhist.

I talked about this previously. Yuji's erasure of his selfhood to make himself a cog in the machine of Jujutsu society formed an ideological opposite to Sukuna's self centered hedonism and this forms the primary philosophical battle underpinning the series. With strong sorcerers repeatedly being those who just do whatever they want unbound by the wills of others, this forms a sort of anti-Buddha archetype, with a consistent theme of subverting Buddhist motifs (iconography, mudra, lines, imagery, etc) when it comes to these characters primarily Sukuna and Gojo. With this framing in mind Yuji was always going to lose until he changed his mindset.

This is why there was so much speculation about Yuji taking up Sukuna's philosophy and "becoming the new Sukuna". I never believed that jjk0 reveals Akutami's optimistic intentions. The subversion of the twin trope also offers hints as to the future. With Maki and Mai, irl Ryomen Sukuna, and Akutami's interview statements about being inspired by conjoined twins, the audience was led to believe Yuji and Sukuna were twins or Yuji was part of Sukuna's soul (same thing according to sorcerers). But this is partly subverted when their real relationship is revealed as Yuji is Sukuna's reincarnated twin's son, created by Kenjaku with one of Sukuna's fingers. Their connection is thus messy, not two pure opposites or halves but like a distorted mirror. As such I don't think their fates will directly mirror each other. If they had actually been halves I think them dying together or ending back in the same body would be extremely likely. But since the duality is warped Yuji's survival chance increases. Yuji plans to shove Sukuna back into his body and that might succeed or Sukuna might finally die.

Yuuji stakes his life and identity on his role as Sukuna's vessel. He'd already envisioned their destiny of eating all the fingers and dying. But Sukuna never needed him, took over Megumi, and shattered Yuuji's world. What is he if not Sukuna's vessel? The loss of both his friend, and the loss of his role his world view his place in the universe is what has driven Yuuji up until dec 24.

"Jin's name in Japanese are written in kanji as (仁), which means benevolence; consideration; compassion; humanity; charity. Interestingly, Yuuji's name, (悠仁), also contain the very same Kanji with an addition of the kanji (悠), which means composed, distant; boundless; endless; eternal. ... Now, we know Sukuna Killed Jin in the womb, considering Jin's name, it's as if the moment Sukuna killed Jin, Sukuna also killed HIS Jin (仁), His HUMANITY... It's as if The HUMANITY (double meaning as Jin and the actual humanity) that Sukuna Killed and trumpled upon all these years are blessed with stronger representative to get revenge on Sukuna" (MasterNature9559)

"This would also explain the lastest chapter (265), why Sukuna doesn't feel a thing for the value of humanity that Yuuji explained, and why Itadori still pity Sukuna despite everything" (MasterNature9559)

I (and many others) did hypothesize that Yuuji was Sukuna's discarded humanity before the Jin twin reveal. I didn't predict Yuji being the son of reincarnated twin. In some ways since Sukuna ate Jin/humanity once it makes sense that only a remade stronger humanity in Yuuji that could take down Sukuna.

Sukuna wouldn't have gotten angry at the end if Sukuna was apathetic about this chapter. He participated this chapter, he got drawn into stupid crawfishing competitions and wanted to show off archery. 265 was Yuuji's attempt to show Sukuna humanity, the worth of a life by showing the little shattered memories he has of the town he grew up in. And Sukuna of course rejects this but something about Yuuji affected him.

Notably Yuuji's recognition in the meaning and worth of life is anti-Buddhist which would be consistent with the rest of the series where Buddhist symbolism is brought up and subverted repeatedly.

10 notes

·

View notes

Note

I found this take a little while ago and since then, I've been reflecting on what makes for "satisfaction" in storytelling.

"Any story to be satisfying requires the villains to get what they deserve. Even if Heroes die, the Villain MUST be punished."

Putting aside the fact that what counts as satisfying easily varies from person to person, the tone here comes off as saying "it's not a good story if it's not satisfying." But if that's the case, why are tragedies and horror stories so popular? More often than not, those stories don't end with the villain's comeuppance.

Or for a different example, take Revenge of the Sith. Palpatine gets away scot-free with everything, and while Anakin does suffer for his evil actions by being mutilated and burned, he's still put back together and free to continue serving Palpatine in his reign of terror. Sure, it's a prequel to a story where Palpatine does receive his ultimate comeuppance in the future, but as an individual story and not part of a wider saga, Revenge of the Sith is arguably not "satisfying," as this guy puts it. And that's widely regarded to be the best of the prequel trilogy.

So do you think a story needs to punish its villain to be satisfying, or is that only a requirement for a story set in a specific genre? Is that even a requirement for any genre, given that the writer could be trying to make a point with their story that necessitates the villain going unpunished?

That statement is very Western minded. In other countries, anti-climaxes are much more of a thing. Something that robs you of your satisfaction and leaves you in a disquieting void. Such an ending is often used to leave one to think and ponder on the themes and concepts and come up with their own conclusions to such things rather than cut it black and white. Inception is a small but good example of an anti-climax because while we get the climax in the dream of them succeeding, the spinning top on the table is still given to the audience to make them reflect on what the film had to say.

I also bring up Inception because, and my memories are BLURRY so sorry if I'm a bit off base, it is essentially a heist movie. There isn't a villain in it to be punished. There is a conflict that must be resolved. That is a large part of what this statement is trying to get across but fails because it's too narrow minded. It's not understanding its own goal well enough not to think about just one type of story. Not every story has a villain... FAR fewer have zero conflict.

A better way to put this sort of statement is:

All stories must conclude their conflict. Even if you do not fix the problem, the problem must be addressed and given a climax.

An anti-climax is not a cliffhanger after all. It's usually something where the hero attempts to fix a problem but then it's made clear that the problem is too big, or ongoing, or that what they were searching for didn't actually exist. You still arrive to an answer to the question posed though. If a man needs to learn that paradise exists with others instead of in a place but he sacrifices all those around him to arrive in a barren field, left all alone, he still finds paradise. He simply found the WRONG paradise and might start crying, both evoking tragedy and the feeling that this can't be the end of the story. That there's a scene missing where he must be happy. There isn't something missing though because this is the conclusion of the story and a version of a climax.

This argument makes me think a lot of how some people judge video games entirely on how fun they are. If you give a player a gun, you must then give them things to shoot with that gun because shooting things is fun. If you let them walk, let them run. If they can jump, give them a reason to. This idea that the only correct goal of a work is to be entertainment. I've criticized things for not being entertaining but only when it clearly had the goal of being entertainment. If something is trying to be disquieting, emotional, thought provoking, etc. like that, it does not need to be entertaining because its goals are different. This is actually why so much that seeks base entertainment is treated as low art because so often the easiest way to be moody and thoughtful is also to be fucking miserable, hence the split between what is popular and what is nominated for the Oscars.

It does not have to be this way though. We can let the two mingle. We can have a great story with a hero where the villain gets away because that is thematically correct. We can have a miserable trudge that pays off in joy. People who want to make definitive statements like this, who want to pin down storytelling to a formula...

Look, a Man with a Thousand Faces is just fucking wrong in trying to state all stories follow the hero's journey and you're going to be just as wrong. Even my own statement is not entirely true but I'm willing to admit that. Some of these people and Cambell definitely weren't and it shows in their piss poor grasp on the true breadth of human expression. If they're right... Well, I won't see you next tale. Because the next tale will just be the same tale according to these people and they're wrong.

======+++++======

I have a public Discord for any and all who want to join!

I also have an Amazon page for all of my original works in various forms of character focused romances from cute, teenage romance to erotica series of my past. I have an Ao3 for my fanfiction projects as well if that catches your fancy instead. If you want to hang out with me, I stream from time to time and love to chat with chat.

A Twitter you can follow too

And a Kofi if you like what I do and want to help out with the fact that disability doesn’t pay much.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

If you have any doubts that the phenomenon of Donald Trump was a long time a’coming, you have only to read a piece that Gore Vidal wrote for Esquire magazine in July 1961, when the conservative movement was just beginning and even Barry Goldwater was hardly a glint in Republicans’ eyes.

Vidal’s target was Paul Ryan’s idol, and the idol of so many modern conservatives: the trash novelist and crackpot philosopher Ayn Rand, whom Vidal quotes thusly:

“It was the morality of altruism that undercut America and is now destroying her.

“Capitalism and altruism are incompatible; they are philosophical opposites; they cannot co-exist in the same man or in the same society. Today, the conflict has reached its ultimate climax; the choice is clear-cut: either a new morality of rational self-interest, with its consequence of freedom… or the primordial morality of altruism with its consequences of slavery, etc.

“To love money is to know and love the fact that money is the creation of the best power within you, and your passkey to trade your effort for the effort of the best among men.

“The creed of sacrifice is a morality for the immoral…”

In most quarters, in 1961, this stuff would have been regarded as nearly sociopathic nonsense, but, as Vidal noted, Rand was already gaining adherents: “She has a great attraction for simple people who are puzzled by organized society, who object to paying taxes, who hate the ‘welfare state,’ who feel guilt at the thought of the suffering of others but who would like to harden their hearts.”

Because he was writing at a time when there was still such a thing as right-wing guilt, Vidal couldn’t possibly have foreseen what would happen: Ayn Rand became the guiding spirit of the governing party of the United States. Her values are the values of that party. Vidal couldn’t have foreseen it because he still saw Christianity as a kind of ineluctable force in America, particularly among small-town conservatives, and because Rand’s “philosophy” couldn’t have been more anti-Christian. But, then, Vidal couldn’t have thought so many Christians would abandon Jesus’ teachings so quickly for Rand’s. Hearts hardened.

The transformation and corruption of America’s moral values didn’t happen in the shadows. It happened in plain sight. The Republican Party has been the party of selfishness and the party of punishment for decades now, trashing the basic precepts not only of the Judeo-Christian tradition, but also of humanity generally.

Vidal again: “That it is right to help someone less fortunate is an idea that has figured in most systems of conduct since the beginning of the race.” It is, one could argue, what makes us human. The opposing idea, Rand’s idea, that the less fortunate should be left to suffer, is what endangers our humanity now. I have previously written in this space how conservatism dismantled the concept of truth so it could fill the void with untruth. I called it an epistemological revolution. But conservatism also has dismantled traditional morality so it could fill that void. I call that a moral revolution.

To identify what’s wrong with conservatism and Republicanism — and now with so much of America as we are about to enter the Trump era — you don’t need high-blown theories or deep sociological analysis or surveys. The answer is as simple as it is sad: There is no kindness in them.

(continue reading)

#politics#republicans#capitalism#ayn rand#libertarians#calvinism#kindness#selfishness#greed#donald trump#conservatism#neoliberalism#the cruelty is the point#reaganism#white america#gore vidal#ayn randroids

102 notes

·

View notes

Text

thoughts on priory of the orange tree (minor structural spoilers)

i liked the first 3/4s of this book a lot more than the final stretch. the book builds its world from familiar fantasy tropes remixed in fun ways and then subverted in even more interesting ways. the basic structure of the book, alternating its narrative between east and west, with 4 PoV characters, lends the story a good rhythm, at least after the first couple chapters where it feels like reading four different first chapters in a row. but all 4 pov characters felt distinct and powerfully realized and I enjoyed my time with all of them.

for a fantasy book I felt like it all felt a bit un-magical. by about halfway through the book has explained the rules of its world, the types of magic and how they work and who can use them, and it cleaves totally to those rules until the end. its just a bit "magic is when you shoot fire out of your hands" for me. doesn't spoil the book or anything but its not my preference. like if you can explain it then its not really magic is my feeling.

my biggest gripe is that there's a point towards the end where all the conflict seems to go totally out of the book. like once all the mysteries are solved and the protagonists have the full picture, they make their plan to win the day, and then the last 20% of the book is just them doing that with very few hiccups.

okay i think i'm being too harsh. they definitely still encounter difficulties on their way to it but the plan they execute is exactly the plan they made. that just feels a bit anti-climactic to me? like the book just tells you how its going to end about 100 pages before the end. and then it does end that way. there's a lack of tension. feels like either something should have gone wrong, or they realize they've misunderstood some fundamental aspect of things and need a new plan.

like it's very much a book about Realizing Things, which is exactly what I loved about it. its about the conflicting beliefs of various cultures and the way ideology distorts history, etc. the big mystery of the book is "What is the real history of this world?" but that mystery is solved about 80% of the way through, and we're left with a big battle scene that doesn't meaningfully engage with the question. just needed one more fundamental shift in understanding right at the end I thought. honestly I was convinced the book was setting us up for that too, but then it just doesn't happen.

in general the ending feels a bit rushed. i dont mind the pacing picking up for the climax of a story but the earlier chapters are so vivid and lush with detail, and then at a certain point we just stop learning new things, so it ends up feeling like just a list of things that happen, idk.

anyway endings are hard, and it's ultimately a pretty small part of a very long book, and the sense that there is some enduring mystery does set it up well for a sequel, which I'd be eager to read. apparently there's a prequel book, which I think I would read if I knew a true sequel was coming, but might not get around to otherwise.

i always sound so negative when i book post but I genuinely liked this book.

last few thoughts uhhh. the book has this really amusing tendency to just kill characters as soon as its done with them. not a criticism except in the instance of (minor spoilers) Tané's friend who got sent to feather island. that one felt odd in that it really seemed like Tané was being set up to meet her there and maybe learn something about how she viewed people (and herself) growing up but then oops! she's actually already dead when we get there.

the romance was very good.

shout out to Roslain I just think she's a great character and she gets one of the best lines in the whole story

also I wish we'd gotten more Tané but apparently the author agrees on that point lol. dragon-hearted girl you mean everything to me

5 notes

·

View notes

Note

Top 5 favourite films?

Thank you, @hiddenlookingglass!

Before I continue, I have to give the obvious caveat that I haven't watched a ton of films, relatively speaking. I think most of these films were watched last year alone. And, making this list, I have to give honorable mentions, because, fuck me, originally this list was seven entries and, short of cheating this ask to write out top seven or ten, it was never going to happen without title-dropping the runner-ups, so here goes:

You Were Never Really Here: Take the premise of John Wick, drain it of all the orchestra and slickness, ground it in broken people, scarred by violence in childhood to adulthood, and polish it off with some of the tightest film editing and sound design in the industry, and you get my unquestionably favorite anti-violence film.

The Final Exit of the Disciples of Ascenscia: A lovely and tragic indie gem of an animated film about a cult, one that finally clicked the appeal of them without diminishing their harm, and one that breaks me in touching on my own questions of loneliness... and whether being in an unhealthy dynamic is better than being alone.

Paddington: The second one is undeniably an even better film, but this one's rain scenes and leisurely narrative feels cozier to me. Whenever I feel like complete dogshit, I rewatch this, because Paddington's charm and earnestness winning over the Browns before realizing he found his family and home with them is hrrgh.

The Green Knight: A visually sumptuous banquet of the senses, trippy and wondrous in how it depicts Gawain's knightly trials, with moral and literary themes that scratch my itches and a fantastic leading actor who carries the film, complete with an ending that brings it all home, landing with such an earned emotional punch.

The Witch: Eggers' mastery at inhabiting the psychological reality of his time periods is impeccable, and it all started with this horror tale of a family plagued by the supernatural outside their walls... and religious anguish and Puritan misogyny among its members. Paired with a hell of an ending and arresting last shot? Delicious.

And, now, onto the proper top five!

1. Everything Everywhere All at Once

Look, is the script overstuffed with exposition about how the multiverse works? Yes. Is it ultimately narratively unwieldly, even faking us out with a false climax, and increasingly uneven to the end? Yes. Are some of the jokes pretty juvenile in the "haha, dildos are funny" realm? Yes. Could it have been more queer? Yes. Is the conclusion a little too tidy and pat, especially for my Chinese childhood abused-ass? Yes, yes, yes. There are definitely fair criticisms that I can agree to, but...

Every time I revisit this film, it wrecks me a whole another way. I never escape this film emotionally unscathed, I philosophically and morally match to it like an alternate version of me jumped into my mind, slipped into my flesh. There are at least five scenes in it that crack me open like a chestnut and I'm left a blubbering mess and astonished at how it manages to tie together all the chaos at the end in such believable catharsis that I can still buy into.

It's still an amazingly-acted film that allows for a rough, unpleasant, and embittered middle-aged female protagonist to lead the events, quite a few ladies dictate and command the plot, and manages to juggle a ton of disparate tones, balancing genuine pathos with bathos, and emotional weight undergirding every bit of silliness and goofy concepts it throws at you. It's still a multiversal familial drama that, at the heart of it, is centered around the experience of what if our first-generation immigrant parents made different choices, that failure can be its own positive experience in a lifetime full of not living up to your parents-demanded potential, and that, in depressive ennui, loneliness, and intense nihilism, all we can do is love, embrace what little joys our speck of lives get, and be there for each other. That, despite the material hardships and pain of a life, our connections still matter enough to keep at it.

It throws the totality of everything beyond the universe at our minds and senses, even down to "talking" rocks and sausage-fingers people, calling to the sheer information overload that most everyone in 2022 felt keenly, acknowledging that it can be such a burden that threatens to hollow us out with existential indifference... and earnestly makes its own case against that. If nothing matters, if all we do and are is worthless in the grander scope of the universe, then these moments we're facing right now, the people in our lives, they matter.

We're not built to attend to everything everywhere all at once. We'll always feel the whisper of what-ifs, the weight of different paths not taken. We might even be useless alone. All we can really do, in the end, is be there for these moments and people around our present. I can't help, but cherish this film on those grounds, but it offered such an awe-inspiring, emotionally resonant experience that it jumps up to my favorite as a result.

2. Pig

How has this masterpiece of a debut, depicting grief, human connection, the heart and art being hollowed by loss and commercial concerns, and masculine vulnerability with such finesse, flown under the radar, nor been nominated for any major accolades? I'm genuinely asking, because, aside from maybe one particular scene that tries to fake us out into thinking it'll become a more conventional John Wickesque revenge thriller, I don't see any crucial flaws that wouldn't warrant it in the discussion as one of 2021's best films. If you haven't yet, treat yourself to one of the best films I've watched.

I watched one of its mid-section scenes, that speech, you know the one if you've watched it, on its own, and wept at the power of its acting, dialogue, and direction by itself. The fact that I still broke down, despite primed, when watching it in the context of the full film should tell you how good Sarnoski's hands are at his first try as director. He brings an intimacy and restraint to the camera in capturing the events in the film, often situating his central characters against the wider scope of his landscapes and environments through a wider lens, showing them as small people against the greater beasts of being scored by grief and loneliness.

Though, given I brought up John Wick, one facet these two share, despite the bait-and-switch of premise, is that almost every character, no matter how minor, has a personality and some texture of history with the protagonist, by direction or sheer acting. Sarnoski just trusts us to infer the weight of history between our characters and, if you want to know how well that approach turns out, Cage's performance should be the clear-cut sign. If you have any doubts of how good Nicholas Cage could be, and trust me, I had a few, this is easily his subtlest, most restrained performance. No signs of a Cage hamfest, this is him at his best and minutely controlled, portraying a stoic man whose hardened demeanor and lack of social graces belies a painful past and years spent in intentional human disconnect.

And how we disconnect from other people bleeds into this narrative, permeates like an unspoken wound that won't scar and heal without proper treatment. Our central characters are haunted by ghosts in the narrative, unable to process what they've lost or reach out to others, for fear of surrendering to the totality of pain from that absence. But there's also disconnect from retreating to what others want, never showing ourselves and only what's acceptable to our social peers, our patrons, or our families, and it costs us piece-by-piece until there's slowly nothing left of us.

And it ends up on an unexpected climax and such a gentle note about masculinity, about how men suffer in trying to bear their griefs stoically, instead of permitting a chink of vulnerability. I dare not spoil more, you have to see it for yourself in how it succeeds in defining its own terms for masculinity and how much emotion cracks through the narrative. It's a film that divulges into the nature of art and food, and how they can bring forth an invitation of connection to others, and it deserves so much consideration and attention, given how much of a powerhouse it is.

3. A Ghost Story

Oh, this sleeper hit of heartache. I knew, going in, that the ending scene would cut to the emotional bone, having checked it out in a clip before, but the knife this slid between my ribs was unexpected in its depth and sharpness, especially given when I watched it. This was after I watched both Pig and The Green Knight, both stellar, emotional films, and while I think Lowery's later work there is better put-together in both pacing and visuals (A Ghost Story absolutely has scenes that drag, and I genuinely think one in particular suffered from overstaying its moment and not fitting Lowery's strengths as a visual/atmospheric director), this touched me so much more in its statement of grief and time.

I've watched enough films to get a decent grasp on my tastes, and its meandering, contemplative, more mundane fares that let scenes breathe in their silence without a quippy aside. This one suffused me in its haunting, contemplative atmosphere from the halfway point, lingering onwards and well after it ended. Lowery's direction is grounded in its intimacy, choosing to focus long stretches on mundanities other directors would've skipped past, as if to say these small moments, daily and common as they are, are what's most important in the grand scope of life and what we focus on, despite the vastness on time upon us all.

And the time spent during grief is where the film guts me in its first half. Going from cozier domesticity, full of lived-in marital discussions and intimacies, to the tangle of strangers sorting through the post-death ceremonies and the silences in the griever's life, booming from the absence of their beloved. Those long, uninterrupted shots, from then on, serve to point out how life persists after our bereavements. There is such attention and empathy to the camera, in how the director wants to show how people cope with grief, how it dogs our every movement, weighs down our limbs, loosens out the tears inside, and make us focus our energies on such simple things like eating food in the dark, to fill the hole our losses leave behind.

But if some trace of us survive as ghosts, upon death, then loss cuts both ways, and it's here that this film truly unmakes me in how it handles grief and remembrance on the ethereal side. Using ghosts as a speculative vehicle, it invites us to see how differently they experience the passage of time, as these beings are temporally untethered, but stay geographically tethered to a particular land. There's such a bitter loneliness to their existences, how being unravaged by time means they are unable to grieve being left alone themselves, they cannot move on by the temporal march by itself.

It's a beautiful, tender film, where centuries can pass by in the blink of a transition, but tiny affections take up whole minutes. A quiet narrative where snapshots of marriage and the tolls of grief take up uninterrupted stretches, letting them sit inside us and linger. A poignant story that ponders, sincerely, if something, anything survives of us after we are gone from this earth, or if we are doomed to have our impact on this mortal plane swept aside and forgotten after we pass away and time moves on from us.

4. The Last Duel

I have a confession: this is my first and, so far, only Ridley Scott joint for various reasons. I don't love R-rated films, I easily get squeamish over live-action gore, and his biggest film and the one most people remember him by was Alien, which wasn't The Thing graphic, but definitely still above my comfort level! So I never touched him for a decade and a half. Now, later, I watched some of the earlier grisly parts of Game of Thrones and found out he directed plenty of period dramas, which was more my speed, and I got the opportunity to check his The Last Duel out with a group viewing. Now, given that preamble, imagine how I felt at its opening scene: a slow-burn of an opening with a lady being dressed before a duel between two men, shot in the same way they are being armored, as if she bears her life as well on the line, and bears witness to two knights charging at each other, before they converge, both hoping to break bones and shed blood.

That, and the subsequent Battle of Limoges, would absolutely impressed onto me that holy shit, Scott directs action in two minutes unquestionably better than some directors do in entire films. He portrays the inherent viciousness, filth, and ferocity of battle in a way that immediately clicked to me as a fan of Joe Abercrombie and a lesser one of Miles Cameron. And armor matters! But that, by itself, wouldn't have made for a favorite of mine. No, it's how this is a proper medieval legal drama with three central, compelling characters at its heart, each explored through a Rashomon-style framing device, and a heartbreakingly timeless message of what a rape victim's choices are in the patriarchy. Does it have its flaws? A few admittedly key ones of editing and dialogue that give away its directorial intent, but nothing so critical to weigh it down from its vaulted highs.