#while Iphigenia and Orestes take after Agamemnon more

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

I wonder if Clytemnestra fully checked out of motherhood and wifedom (is that a word?) after what happened with Iphigenia resulting in the very neglectful/abusive dynamic we see her share with Electra later on.

Because 1. What is the point of being good or caring as a mother if your children get sacrificed and 2. What is the point of being a good wife if your husband sacrifices your children and is unfaithful to you 3. NO ONE suggests he should be punished for these actions so if he does it it's fine if you do it too 4. The daughter you have left loves her father more because you treated her like shit

#and like yeah we can talk about the double standard of infidelity back then but even if women werent supposed to care#i bet they fucking did#the whole family is a frog 2 me i need to dissect it#also this is just me speculating but in my head i think Electra and Clytemnestra are very similar#while Iphigenia and Orestes take after Agamemnon more#she went there is no point to being a good mother -> there is no point to being a good wife -> there is no point to being a good person#love her so much#clytemnestra

92 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi! Can u please talk more abt Helen, Menelaus & Paris in ur AU? C:

omg thanks for asking!

(i should warn that helen comes with trigger warnings. i’ll put a warning before whatever bullet point mentions something of note)

so helen is sort of a cliche high school movie popular girl. she’s beautiful, she’s wealthy, she’s smart. she’s not a huge fan of the attention and she prefers to just stick with her twin clytemnestra and her cousin penelope, but she guesses it can’t be helped

paris has been pursuing her for a while and she’s not thrilled about it. he’s far too insistent and pushy. she much prefers menelaus who she was partnered with on an assignment. they like each other but menelaus knows helen has a rep of not liking people who are too pushy with her. helen knows menelaus likes her but clytemnestra and agamemnon are having a nasty breakup and for obvious reasons dating her twin’s ex’s brother is a messy situation she does NOT want to be involved in

have i mentioned menelaus is shorter than helen bc he is and i like it very much.

helen is a fairly tall girl (around 5’10) and menelaus is a cool 5’5, which is short but not as short as odysseus who’s 5’3.

(bless)

don’t let his height fool you he is on the wrestling team and he is on the wrestling team for a REASON.

having said that he 100% wears socks and crocs to class. he dresses like a loser next to helen who’s like

perfect hair perfect clothes perfect makeup

helen and clytemnestra are rly tight with their brothers who are ALSO twins. you know them you love them. castor and pollux. people thought they were quadruplets but luckily for leda they were not

iphigenia, electra, orestes, chrysothemis and hermione do exist, but for obvious reasons they’re not their kids they’re kids about pyrrhus’ age who are their cousins. they‘re still protective of them don’t get me wrong. it’s the whole reason clytemnestra and agamemnon break up. call that shit the orestea on the remix

menelaus is a year younger than agamemnon and they have a love-hate relationship going on. it’s mostly generational trauma. and agamemnon.

which reminds me menelaus and agamemnon have had a go of it. their dad atreus was arrested for attempting to murder his brother after he found out his wife was having an affair with him. since then thyestes (the brother) and aerope (the ex wife) have been married but it’s not doing so hot.

as you can see that does wonders for menelaus and agamemnon’s perspective on relationships. they just go in opposite directions with it.

agamemnon repeats the cycle menelaus fears the cycle it’s a tale as old as time

um… so… speaking of bad relationships…

at one point clytemnestra and penelope’s Boy Problems™️ overlap (clytemnestra’s having a messy breakup, penelope’s boyfriend is having something of an awakening) so they decide to go to a party

(TW: RAPE) helen gets separated from them and paris takes this opportunity to dr drug and rape her. clytemnestra and penelope find her and they go straight to their parents who are obviously outraged. they take her to court but the court rules that, since paris has been courting her and there were no witnesses and no way to prove she hadn’t taken the drug of her own accord, that paris wasn’t in the wrong and actually helen should marry paris and drop out of high school. they threaten to sue helen and her family for emotional damages if she doesn’t

(this is your friendly reminder that this is still an ancient civilisation in the modern era and women’s rights have very blurred lines. in this world such a sentence is about the same morality level as being legally ruled a housewife. women’s rights are in place, but there are a lot of exploits that allow corrupt courts to keep backwards rulings based on technicalities and loopholes)

obviously this is ridiculously backwards so helen’s parents take it to a higher court which overrules this decision and nobody’s getting sued. all things considered the whole issue ends quite quickly. the only issue is that paris gets off with only paying a fine and the school not allowing them to be in the same classes to minimise contact

but obviously paris is paris so the situation just kind of dissolves into him provoking menelaus (since he’s not allowed near helen). then he’d hide behind hector as soon as menelaus or one of his friends try to absolutely pummel him. the trojan war is essentially menelaus and co trying to beat paris up, hector beating them up back, and then they all end up in detention

in case you’re wondering how hector feels about all of this: he doesn’t support paris — in fact quite the opposite — but when his brother is using him as essentially a human shield and people start punching him to get to paris, he’s obviously going to punch back

anyway it’s a whole mess. everyone’s fighting. clytemnestra and cassandra are having an enemies to lovers romance— wait who said that?!

the whole thing ends when paris accidentally ends up in the same room as helen but odysseus manages to convince a teacher that he did it on purpose and he gets expelled and suddenly there’s no fighting in the hallways anymore woah

the things odysseus does not only for bros but also to win back his girl it’s crazy

helen and menelaus take things slow for obvious reasons

but they do go on nice dates where they hold hands and leave room for artemis

i should mention that this one is a storyline i haven’t solidified and some things may change!

#this one was more plot than the patrochilles one#not my intention#greek mythology#tagamemnon#ancient greek mythology#the iliad#trojan war#ancient greece#helen of troy#helen of sparta#menelaus#agamemnon#clytemnestra#penelope#odysseus#paris of troy#hector of troy#ask me anything

28 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello there, just some lil questions I wanted to ask: what do you think about Odysseus? Since I am still unsure if he is a good guy after all…and what do you think about the wooden horse ?

Sending best wishes :)

Hi!

Overall? I do like Odysseus.

The question about if he is a good or bad guy? I feel it depends a lot of which Odysseus we are talking about. The many different adaptational Odysseus, one can argue, but I feel it's unfair measuring homeric Odysseus in a good vs bad measure. This is something you can't really make with any homeric figure, not only Odysseus.

One thing I enjoy of Troy (2004) is how in this analogy with modern imperialism it positions Odysseus as a cunning king that remains subservient to the imperial power in order to secure his land. Ithaca is in this kinda third world country position to an United States-coded Mycenae and that is very interesting to see.

However, there is also the fact that the dynamic of Odysseus and Agamemnon resembles Gandalf and Denethor in the Return of the King. He is the only one seeing the bigger picture while this armchair general calling himself " King of Kings" (the movie makes its own specifical use of this epithet from the Iliad) takes the worst choices ever. In the context of the film, with Agamemnon in the middle of a power driven mystic delirium oathing to Zeus he will sacrifice 40.000 greeks smashing the walls of Troy, you really can't blame the guy.

At that point of the film, Agamemnon is pretty much like grief over Boromir crazy Denethor about to burn Faramir alive, only he is about to get them all killed to destroy Troy in memory of Menelaus. Odysseus reacts as a way to preserve everyone, just as Gandalf sort of taking command in the Siege of Gondor. Arguably, Paris also attempts the same with Priam when he tells him not to accept the horse, but fails.

Speaking of Troy (2004) Odysseus? Yes, he is meant to be one of the good guys. The movie responsabilizes Agamemnon for him having to come up with the trojan horse and for the brutality displayed on the fall of Troy. It's not about power for him anymore, it has became a personal vengeance. He is, essentially, doing to that city for Menelaus exactly what Achilles did to the corpse of Hector over Patroclus.

Now, if we get in mythological territory, things get more complicated. This is why I feel you can't really judge him on good vs bad mentality. Homeric/ Trojan Cycle Odysseus is not a " did nothing wrong" neither a " figure of evil" character. He has both very redeemable and very loathsome moments.

For example, he is a devoted parent. Despite being far away from his boy, Telemachus is his life. While all the other heroes describe themselves in name of their parents, he adresses himself publicly as " the father of Telemachus". However, he is the direct responsible for the death of two kids: encouraged the sacrifice of Iphigenia, and in some versions, killed by his own hand the baby boy of Hector to stop him from growing and possibly seeking revenge for the atrocities commited.

I do feel blaming him for the trojan horse would be as ridiculous as the people who hate on Hector for killing Patroclus. It's an act of war in a war story, the guy did what Athena inspired him to do in order to win. However, the especially vile atrocities commited during the fall of Troy are another story. With the all white cast of the film the thing got a bit unnoticed, but Troy (2004) introduced the concept of the trojan war as the first genocide of the West against the East. As my very first introduction to the story, this idea kind of stayed with me.

I hate what the greeks did in Troy, but the story itself brings them their karma. Am I pissed off about Astyanax and Andromache? Absolutely, but the gods punished Odysseus for me with that trip back home and Pyrrhus got disowned by Peleus to later get killed by Orestes. Most of the greeks turned out cursed, and the trojans ended up founding Rome!! I have nothing left to hate, gods balanced the universe for me.

( If you like to see greek karma in action, like I do, I recommend the book " The Talisman of Troy " by Valerio Massimo Manfredi. Despite it takes the post war greek pov of a wide variety of characters, but mostly follows Diomedes, it is cathartic from the trojan one. The conversation stopping the Aeneas vs Diomedes duel in italy is delicious when it comes to trojan catharsis.)

When it comes to mythological Odysseus, I fall on a middle ground. I am against those fully negative " Odysseus was a cheater asshole" narratives represented by stuff like Madeline Miller's Circe. However, I am not as forgiving of the heaviest Odysseus' wrongs as, let's say, some sections of the Epic fanbase.

And btw, he was not a cheater. When the options are " sleep with this goddess or risk her wrath", there is nothing much the man could have done even if it happened twice. The only time he had the capacity to consent was when Nausicaa got infatuated with him, and he didn't sleep with her. I just say people who hate on Odysseus for " cheating " are looking at the wrong reasons lol.

Books Odysseus is a complicated man, but I enjoy his character too.

( all but the Telegony, in this blog we pretend the Telegony never existed. It's such an OOC trainwreck, even if it's ancient, I refuse to take it in consideration.)

#the odyssey was a comfort book growing up for me#my first copy from back then was a censored one my mom read in highschool#( she went to school during a dictatorship regime so it was heavily censored.)#for a long time i didn't know the whole details#that being said i admit i feel a strange filial kind of love for odysseus#like he is my fictional dad i grew up reading about lol#so yes he is capable of despicable things and many of those make me angry#but at the end i am good with him#he got what he deserved for those#in what comes to the war i have a leaning towards pro troy stance#and I defend the trojan heroes from all the unfair slander they get#but i don't hate odysseus#asks#messages#odysseus#the odyssey#troy 2004

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Thousand Ships excerpt

Several more years passed, and Penelope, Clytemnestra and I all gave birth around the same time. For Clytemnestra, this marked her third child, for Penelope and I our first. I gave birth to a daughter, while Clytemnestra and Penelope both had boys. Menelaus and I named her Hermione.

The three of us agreed that we simply had to meet up, but the question remained where. Clytemnestra insisted Penelope and I come to Mycenae, saying that young Iphigenia and little Elektra wanted to see their aunts. We obliged. Menelaus said he had royal duties to attend to, so I was accompanied by a royal escort. Fortunately, we made it to Mycenae safely.

I was surprised to see that Penelope and Odysseus had arrived before I, Ithaca being further away than Sparta, and over water rather than land. Penelope sat on an arrangement of pillows, cradling a baby that looked like a perfect mix of her and Odysseus. He wasn’t chubby like little Hermione or most of the babies I’d seen, but he wasn’t too skinny either. He looked happy and healthy. He had a full head of dark hair and piercing gray eyes.

“Penelope!” I greeted her. “It’s been so long! Is this your son?” I sat down inches from her.

“It really has,” my cousin said. “And yes, this is Telemachus.” I nodded.

“This is Hermione.” In that moment I realized for the first time that my daughter didn’t look much like me at all. She had my eyes and skin tone, but that was all. She had Menelaus’ fiery red hair and as much of his face shape as an infant could have.

That was when Clytemnestra stalked over. Five-year old Elektra was clinging to her skirts, and she carried a baby that was the spitting image of herself. Whereas Elektra and Iphigenia had more of their father in them- something I knew Clytemnestra despised- the baby boy in my sister’s arms looked exactly like her.

“Helen, Penelope,” she said with a smile. “This is my son, Orestes.” Penelope nodded.

“He’s beautiful.” I pressed my lips together and wetted them with my tongue.

“I know how much you were longing for a child that looked like you, my dear sister.”

“Was I?” My sister looked amused, like she hadn’t the slightest idea what I was talking about. “I suppose the other two do take a little more after Agamemnon, but they have my spirit in them at least.” Elektra giggled and let go of her mother’s dress.

“Aunt Helen! Aunt Penelope! Mother, I want to play with my cousins!”

“Ask your aunts,” Clytemnestra smiled. “Helen, do tell me what your daughter’s name is.”

“This is Hermione,” I said with a smile. “She has some of me in her, but really she looks like Menelaus.”

“I see,” Clytemnestra said. “Though your hair is nearly red itself.”

“True,” I said. “And of course Telemachus looks like a perfect mix of his mother and father. Another of Penelope’s masterpieces.”

“True,” my sister said, and we laughed.

#writing#excerpt#greek mythology#trojan cycle#helen of sparta#helen of troy#hermione of sparta#clytemnestra#penelope#telemachus#orestes#elektra#idk I just really love the spartan princesses#and I wanted to write this fluffy excerpt so enjoy

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Even in our sleep, pain which cannot forget falls drop by drop upon the heart until, in our own despair, against our will, comes wisdom through the awful grace of God.” - Aeschylus via Robert Kennedy (4 April 1968)

“The Oresteia, broadly speaking, is a mythological story about a fundamental shift from vengeful retribution to a new civic justice system based on dialogue and lawful process, and in that sense, Kennedy’s use of the verses to emphasize justice and reconciliation makes sense. The translation by Edith Hamilton that he quotes adds a Christian dimension of God’s mercy and compassion that doesn’t exist in the original, but as long as the overall idea of justice remains intact, there should be no issue with Kennedy viewing Aeschylus from his own perspective.

(…)

Agamemnon’s murder by his wife in retaliation for Iphigenia is imminent. She is to be killed by her son Orestes in the trilogy’s second installment, Libation Bearers. In the third act, Eumenides, Orestes is pursued by the vengeful Furies, and the goddess Athena does not institute the new justice system to adjudicate the conflict until the end of the play. So, the light at the end of the tunnel is far off. We are still trapped in the cycle of violence and vengeance, with no end in sight.

The word I translate as “favor”–“grace” in Kennedy’s quotation–is charis in Greek. The word refers to “grace” in the sense of beauty, as well as kindness or goodwill. It can mean “favor,” in the sense of thankfulness or gratitude toward someone, but it also refers to an actual favor–an action–performed to reciprocate another’s kindness.

The phrase “comes about by force” is really a single word in Greek, biaios, meaning “forcible” or “violent,” which clashes harshly with the idea of kindness attached to charis.

So we might very literally translate that sentence: “Perhaps the reciprocal response of the gods sitting on their sacred throne is violent.” This gives the entire passage a completely different meaning that instead suggests the so-called wisdom of the gods can only be achieved through greater violence. It foreshadows the vengeance for Iphigenia that is going to come for Agamemnon.

If this is true, then the words of Aeschylus clearly do not align with Robert Kennedy’s intention. He meant to say that our response to suffering and violence should be to rise above it, and to learn through the “awful grace of God” how to have the wisdom to respond with love and compassion. Instead, Aeschylus’ Chorus seems to be worried about “the violent favor of the gods,” and given Robert Kennedy’s assassination, maybe they are right after all.

But we know what the Chorus does not: that the end of the Oresteia holds the greater promise of a new worldview, one in which these traditional ideas of violence in response to violence no longer hold true. Vengeance will be put aside, and the new democratic justice system of Athens, based on open dialogue and debate, lawful procedure, and reconciliation will be established, perhaps in the way Robert Kennedy would have hoped for.

That message is what we see when we step back and take a broader look at the overall meaning of the Oresteia: while in the present moment of suffering it may seem as if there are only more struggles ahead, in the end it is possible to strive toward the greater ideals of justice. So, there is only a real disconnect in meaning if we look at these verses in isolation, in the specific part of the play’s story where they appear, but together with the rest of the play–and in the new context of Kennedy’s speech–they take on a new, optimistic meaning in the face of suffering and tragedy.”

#aeschylus#kennedy#robert kennedy#sirhan sirhan#god#wisdom#grace#agamemnon#martin luther king jr#assasination#oresteia

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

This might be incoherent but I wanna talk about tumblr’s girlbossification of Clytemnestra because like. A) “Clytemnestra was right” ignores/erases a lot of really fascinating complexity from the story and frankly does a massive disservice to both Electra and Iphigenia, the daughter Agamemnon killed, two of my favorite girlbosses in the canon (and Orestes, who I also adore), and B) Clytemnestra is way more interesting when we open up the moral ambiguity of what she did as opposed to oversimplifying it to “grieving mother kills her husband for killing her daughter,” which is arguably not even a simple version of what happened.

First off, “was Agamemnon right to kill Iphigenia,” “was Clytemnestra right to kill Agamemnon,” and “was Orestes right to kill Clytemnestra” are three separate questions, and the latter two take the answer to the previous ones into account but aren’t solely determined by them, but tumblr seems to get stuck on “no, obviously,” therefore “yes, obviously,” therefore “no, obviously,” which is an interpretation, but all three are really interesting complex questions, that’s why people keep fucking writing Oresteias!!

“Was Agamemnon right to kill Iphigenia” is often looked at as “is it cool to kill a teenage girl so you can go to war” but it is WAY more complicated than that. Like I am fully on the fuck Agamemnon train but not for the reasons I feel like a lot of people here are. Euripides’ Iphigenia at Aulis is so fucking good and really highlights how utterly and completely Agamemnon did not have a choice. It wasn’t “sacrifice Iphigenia or go home,” it was “sacrifice Iphigenia or all the armies die here at Aulis,” which means that functionally it was “sacrifice Iphigenia or the men kill you and then her anyway.” On top of that, it’s not like turning around and going home would be a real option even if it was a logistical one, and this is Not the post to get into the causes of the Trojan War but the short version for this purpose is that is simply not how a tragedy works. Still extremely fuck Agamemnon for lying to Iphigenia and to Clytemnestra and for using Achilles, and Achilles in that play does a great job demonstrating how we’d want Agamemnon to act by telling Iphigenia fuck that I will take on every single soldier here if you say the word but like. That isn’t a rational response, that’s a prideful, emotional response and the narrative knows it and Iphigenia knows it. Iphigenia was tricked to Aulis and for that Agamemnon is a shithead, but Iphigenia went willingly to the altar and she died a hero and she knew it, and that is way too sexy and powerful to bury to make an uncomplicated vengeful mother story out of Clytemnestra. Of course that’s only one telling and there are others where Iphigenia doesn’t have that kind of power but why would you ignore the ones where she’s so fucking cool. My best friend Iphigenia

“Was Clytemnestra right to kill Agamemnon” I gotta say I am still on board with “lmao yeah” to that one but there is so much more to it than revenge. I think it’s important to acknowledge that Clytemnestra very much was cheating with Agamemnon with his cousin and she very much did kill him for power and while it is a sexist double standard to condemn her for infidelity and not Agamemnon I think we can in fact condemn them both! And there’s also that there is so much indignity in the way she killed him that I feel like gets lost in cultural translation but like. Agamemnon did not get to die gloriously in battle. Agamemnon died naked and tangled in a shower curtain after returning home victorious. It’s the same kind of thing that makes Medea’s prophecy of Jason’s death so powerful, that a great hero dies pathetically, and you absolutely could argue he fucking deserves it (Jason certainly did) but it is also worth acknowledging that Agamemnon does not get the dignified death that Iphigenia does. Even if we take Clytemnestra killing Agamemnon as purely revenge, she gave him worse than he gave Iphigenia. And we gotta acknowledge that she did also axe murder Cassandra which is just plain fucked up. I don’t think I have to explain that one that’s fucked up. But my point is Clytemnestra is frankly SO much more interesting if we separate “did Agamemnon deserve what he got” (yeah, probably) from “did Clytemnestra do it for the right reasons” (who knows!)

And “was Orestes right to kill Clytemnestra” I mean. That one’s so complicated it gets an entire play of the Oresteia dedicated to it. That one’s so complicated Aeschylus had the Athenian justice system invented to deal with it. And this post about Clytemnestra is not NEARLY gonna get into All My Thoughts About That (affirmations voice I am NOT going to go off about Hamlet-Orestes parallels in this post) but the main factor in how it relates to Thoughts On Clytemnestra Specifically is like. Pretty consistently Clytemnestra was a shitty mother at least to Electra and (looks at smudged writing on hand) chrysanthemums [Chrysothemis] and depending on the telling just straight-up Sold Orestes. In at least three of four tellings I’m familiar with (I do not remember if it comes up in the Odyssey and I cannot be assed to check rn) Electra is 100% on board with the mother-murdering, and in Euripides she actually holds the sword with Orestes and helps him physically do it which is fucking metal I adore Electra with my entire heart. Like. Yes the final argument Aeschylus gives to acquit Orestes (that the father is more closely related to the child than the mother) is utter bullshit but he also doesn’t (directly) address a lot of the factors that are Very Relevant to us today (like, any of the non-avenging-his-father reasons for Orestes to kill Clytemnestra, nor any of the non-because-she’s-his-mother reasons for him not to), so I think analysis can and should go well beyond what Aeschylus brings up

Anyway I. I swear this isn’t an anti-Clytemnestra post this is just a pro-acknowledging Clytemnestra’s complexity post because frankly she (and Iphigenia, and Electra) is WAY too cool a character to be oversimplified how I keep seeing. I mean I don’t know what I expected to happen to one of the most juicily morally gray stories I’ve ever encountered on a site where black-and-white hot takes are encouraged but also I hope people who are big enough nerds to read my five-paragraph essay about Clytemnestra are on board for deeper analysis dhfgdhg

#bloop#Clytemnestra#the oresteia#god fucking dammit am I having another Oresteia phase. I don’t even remember why I started thinking about this#anyway this has not even scratched the SURFACE of my Oresteia thoughts#many of my most beloved blorbos ❤️

747 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bob's Burgers, Season 11, Episode 7, Diarrhea of a Poopy Kid

When Gene can't eat Thanksgiving dinner because of a stomach flu, the family tries to make him hate food, by telling him horror stories about food: in both Tina's — a parody of Harrison Ford's Air Force One (1997) — and Bob's —a parody of Michael Bay's Armageddon (1998) — stories, Gene insists that his wife be played by Linda. The others find it questionable, while Linda finds it sweet.

Bob's Burgers, Season 9, Episode 14, Every Which Way but Goose

Oedipus Mythology

Laius, king of Thebes, was warned by an oracle that his son would slay him. So, Laius started avoiding physical contacts with his wife, Jocasta. Unfortunately, a night, while he was strongly drunk, ended up sleeping with her, getting Jocasta pregnant. So, when Jocasta, bore a son, Laius had the baby exposed (a form of infanticide) on Cithaeron. (Tradition has it that the name Oedipus, which means “Swollen-Foot,” was a result of his feet having been pinned together, but modern scholars are skeptical of that etymology.) A shepherd took pity on the infant and decided to rescue him and gave little Oedipus to the royal couple that didn't have child of their own. So, Oedipus was adopted by King Polybus of Corinth and his wife and was brought up as their son. In early manhood Oedipus visited Delphi and upon learning that he was fated to kill his father and marry his mother. Horrified by this reveal, Oedipus, who didn't know to have been adopted, he decided to never return to Corinth.

A depiction of Oedipus and the sphinx, taken from an Attic kylix produced by an artist known to modern scholars as ‘Painter of Oedipus’. Gregorian Etruscan Museum, Vatican City, Rome. 470 B. C.

Traveling toward Thebes, the young man encountered Laius, who provoked a quarrel in which Oedipus killed him. Continuing on his way, Oedipus found Thebes plagued by the Sphinx, who put a riddle to all passersby and destroyed those who could not answer. Oedipus solved the riddle, and the Sphinx killed herself. In reward, he received the throne of Thebes and the hand of the widowed queen, his mother, Jocasta. They had four children: Eteocles, Polyneices, Antigone, and Ismene. Later, when the truth became known, Jocasta committed suicide, and Oedipus (according to another version), after blinding himself, went into exile, accompanied by Antigone and Ismene, leaving his brother-in-law/uncle Creon as regent. Oedipus died at Colonus near Athens, where he was swallowed into the earth and became a guardian hero of the land.

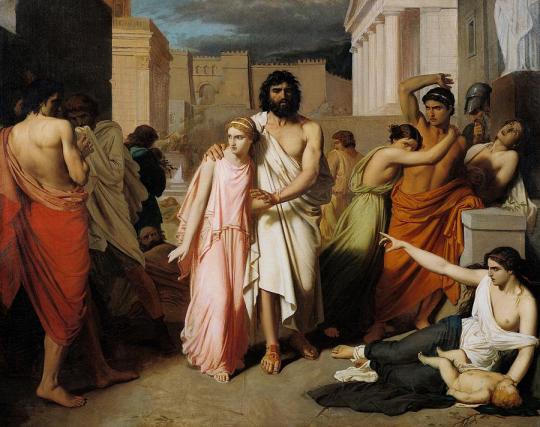

Charles Francois Jalabert, Oedipus and Antigone (1843)

Antoni Brodowski, Oedipus and Antigone (1823)

Oedipus' children and his uncle/brother-in-law have a tragic mythological story of their own: Antigone and Ismene, after the death of their unfortunate father, returned to Thebes, where they attempted to reconcile their quarreling brothers—Eteocles, who was defending the city and his crown, and Polyneices, who was attacking Thebes. In fact, Eteocles and Polynices were twins and they made a pact in which they would govern on Thebes togheter in alternate years, but at the end of his first year of government, King Eteocles decided to not pass the crown to his brother, breaking their pact. So, Polynices with his loyal followers and allies decided to attack Thebes to obtain the crown for himself. Both brothers, however, were killed, and their uncle Creon became king. After performing an elaborate funeral service for Eteocles, Creon forbade the removal of the corpse of Polyneices, condemning it to lie unburied, declaring him to have been a traitor. Antigone, moved by love for her brother and convinced of the injustice of the command, buried Polyneices secretly. For that she was ordered by Creon to be executed and was immured in a cave, where she hanged herself. Her beloved, Haemon, son of Creon, committed suicide.

Antigone with Polynices' Body, painting by Sebastien Norblin, 1825 CE, Paris, Ecole Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts.

Oedipus in art: X

Oedipus complex

in classical psychoanalytic theory, the erotic feelings of the son toward the mother, accompanied by rivalry and hostility toward the father, during the phallic stage of psychosexual development. Sigmund Freud derived the name from the Greek myth in which Oedipus unknowingly killed his father and married his mother. Freud saw the Oedipus complex as the basis for neurosis when it is not adequately resolved by the boy’s fear of castration and gradual identification with the father. The corresponding relationship involving the erotic feelings of the daughter toward the father, and rivalry toward the mother, is referred to as the female Oedipus complex, which is posited to be resolved by the threat of losing the mother’s love and by finding fulfillment in the feminine role. Although Freud held the Oedipus complex to be universal, most anthropologists question this universality because there are many cultures in which it does not appear. Contemporary psychoanalytic thought has decentralized the importance of the Oedipus complex and has largely modified the classical theory by emphasizing the earlier, primal relationship between child and mother.

Here the link to a post of mine in which I analyze the relationship between Freud and his parents:

Electra complex

Electra complex is the female equivalent of the Oedipus complex. Carl Jung introduced this concept in his Theory of Psychoanalysis in 1913; however, Freud did not accept this theory as he believed that Oedipus complex applies to both boys and girls although they experience it differently.

What happens in the Electra complex is that girls become unconsciously attracted to their father and develop hostile feelings towards mothers, seeing them as their rivals. Penis envy is an element in female psychosexual development, where the daughter blames the mother for depriving her of a penis. Eventually, this resentment leads the girl to identify with and emulate the mother, incorporating many of the mother’s characteristics into her ego.

Electra Myth

Electra was the daughter of King Agamemnon and Queen Clytemnestra of Mycenae. She was the sister of Iphigenia (who Agamemnon sacrificed to Neptune to have a good sail to Troy) and as well as Orestes, with whom they planned the murder of their mother and her lover Aegisthus, seeking revenge for the murder of their father. Agamemnon was the brother of Menelaus, who was king of Sparta and married with Helen (the woman fallen in love with Prince Paris of Troy and "kidnapped" by him) and Clytemnestra was Helen's sister.

When Agamemnon returned from the Trojan War along with his slave-lover Cassandra (was a fromer priestess of Apollus, cursed by Apollus himself to tell future and not be believed for refusing his love attentions, and also the sister of Paris), he was murdered by his wife and her lover, Aegisthus, who was also his cousin. Aegisthus had a rotten past of being born by an incestuous rape and in a family history of adultery, murders and revenge: Thyestes, Aegisthus' father, and Atreus, father of Menelaus and Agamemnon, were brothers and they were exiled by their father for killing their own half-brother to rule over Olympia. They moved to Mycenae and started fighting for the throne. Thyestes was the lover of Atreus' wife and Atreus for revenge murdered all Thyestes' sons and severed their flesh to their unwilling father as meal. Horrified by have eaten his own children, Atreus plotted his revenge and asked for help to an oracle, that told him that his revenger would be born from the rape of his own daughter, Pelopia. However, when Aegisthus was first born, he was abandoned by Pelopia, ashamed of the origin of her son. A shepherd found the infant Aegisthus and gave him to Atreus, who raised him as his own son. Only as he entered adulthood did Thyestes reveal the truth to Aegisthus, that he was both father and grandfather to the boy and that Atreus was his uncle. Aegisthus then killed Atreus, accused of murdering his brothers/uncles and forcing Thyestes to rape his own daughter. While Thyestes ruled Mycenae, the sons of Atreus, Agamemnon and Menelaus, were exiled to Sparta. There, King Tyndareus accepted them as the royalty that they were and gave his daughters' hands (Clytemnestra and Helen) in marriage to the brothers. Shortly after, he helped the brothers return to Mycenae to overthrow Thyestes, forcing him to live in Kythira, where he died. Clytemnestra was furious at her husband for sacrificing their daughter Iphigenia before his departure to Troy and Aegisthus with a similar past wasn't that happy with his uncle and cousins too. So, they killed both Agamemnon and Cassandra upon their arrival, even though Cassandra had warned of this ill fate.

Clytemnestra after the Murder, oil painting by John Collier, 1882, London, Guildhall Art Gallery

Clytemnestra hesitates before killing the sleeping Agamemnon as Aegisthus urges her on. 1817. Pierre Narcisse Guerin. French 1774-1833. oil/canvas.

Electra and Orestes sought refuge in Athens, and when Orestes was 20 years old, he consulted the Oracle of Delphi; there, he was told to take revenge for his father's death. Along with his sister, they went back to Mycenae and plotted against their mother and Aegisthus. With the help of his cousin and best friend, Pylades, Orestes managed to kill his mother and her lover; before her death though, Clytemnestra cursed Orestes and as a result, the Furies or Erinyes (justice or revenge goddess, who punish people who committed most horrible crimes) chased him, as it was their duty to punish anyone commiting matricide or other similar violent acts. Electra, instead, was not haunted by the Erinyes.

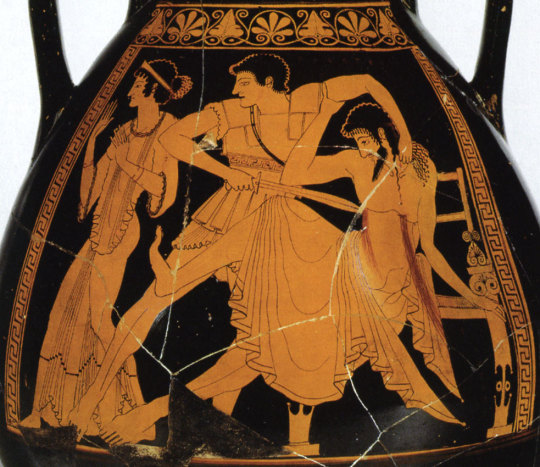

Orestes murders Aegisthus, (On the left Chrysothemis), Red-figure pelike. Detail. Attic., by an ancient artist known as the Berlin Painter. Clay. Ca. 500 B. C., Vienna, Museum of Art History

The Ghost of Clytemnestra Awakening the Furies, John Downman, 1781, Yale Center for British Art, New Haven, Connecticut, United States of America

About the House of Atreus: X

#vavuskapakage#bob's burgers#Bob's Burger#bobs burgers#bobs burger quotes#gene belcher#Bobs burger#Oedipus complex#Electra complex#Oedipus#electra#sigmund freud#Freud#carl jung#Jung#Psychoanalytic theories#psychoanalysis#greek mythology#Cassandra#helen of troy#paris of troy#Agamemnon#clytemnestra#Aegisthus#antigone#orestes#ancient greek mythology#history art#linda belcher#louise belcher

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Worship of Taurian Artemis and Iphigeneia

I wanted to write this post because I worship Iphigeneia and I think it is kinda neat. There is a connection between Artemis as she was worshipped in Tauris and Iphigeneia. Iphigeneia may have been syncretized with Artemis and the goddess who was worshipped in Tauris. Artemis has a few epithets that are related to Iphigeneia.

“O′RTHIA (Orthia, Orthias, or Orthôsia) a surname of the Artemis who is also called Iphigeneia or Lygodesma, and must be regarded as the goddess of the moon. Her worship was probably brought to Sparta from Lemnos. It was at the altar of Artemis Orthia that Spartan boys had to undergo the diamastigosis (Schol. ad Pind. Ol. iii. 54 ; Herod. iv. 87; Xenoph. de Rep. Lac. ii. 10). She also had temples at Brauron, in the Cerameicus at Athens, in Elis, and on the coast of Byzantium. The ancients derived her surname from mount Orthosium or Orthium in Arcadia.” (Theoi.com-Artemis Cult titles and epithets)

“TAU′RICA (DEA) (hê Taurikê), "the Taurian goddess," commonly called Artemis. Her image was believed to have been carried from Tauris by Orestes and Iphigenia, and to have been conveyed to Brauron, Sparta, or Aricia. The worship of this Taurian goddess, who was identified with Artemis and Iphigenia, was carried on with orgiastic rites and human sacrifices, and seems to have been very ancient in Greece. (Paus. iii. 16. § 6; Herod. iv. 103.) (Theoi.com-Artemis Cult titles and epithets)

“TAURIO′NE, TAURO, TAURO′POLOS, or TAURO′POS (Tauriônê, Taurô, Tauropolo, Taurôpos), originally a designation of the Taurian goddess, but also used as a surname of Artemis or even Athena, both of whom were identified with the Taurian goddess. (Hesych. s. v. tauropolai.) The name has been explained in different ways, some supposing that it means the goddess worshipped in Tauris, going around (i. e. protecting) the country of Tauris, or the goddess to whom bulls are sacrificed; while others explain it to mean the goddess riding on bulls, drawn by bulls, or killing bulls. Both explanations seem to have one thing in common, namely, that the bull was probably the ancient symbol of the bloody and savage worship of the Taurian divinity. (Schol. ad Soph. Ajac. 172 ; Eurip. Iphig. Taur. 1457 ; Müller, Orchom. p. 305, &c. 2d ed.)”(Theoi.com-Artemis Cult titles and epithets)

Iphigenia is also mentioned alongside Artemis and the Taurian goddess in Herodotus’ Histories and Pausanias’ description of Greece. This shows that Iphigeneia was worshipped but was also syncretized with Artemis which is interesting.

“Among these, the Tauri have the following customs: all ship-wrecked men, and any Greeks whom they capture in their sea-raids, they sacrifice to the Virgin goddess1 as I will describe: after the first rites of sacrifice, they strike the victim on the head with a club; [2] according to some, they then place the head on a pole and throw the body off the cliff on which their temple stands; others agree as to the head, but say that the body is buried, not thrown off the cliff. The Tauri themselves say that this deity to whom they sacrifice is Agamemnon's daughter Iphigenia. [3] As for enemies whom they defeat, each cuts his enemy's head off and carries it away to his house, where he places it on a tall pole and stands it high above the dwelling, above the smoke-vent for the most part. These heads, they say, are set up to guard the whole house. The Tauri live by plundering and war.” (Herodotus Book 4 chapter 103)

“Pausanias has left us two sources that identify Artemis with Iphigenia: in one of them he mentions a temple of Artemis at Hermione in Argolis where this goddess is called Iphigenia (Paus. II, 35, 1), i.e. testifies of a cult of Artemis-Iphigenia; in the other – a temple of Artemis with a statue of Iphigenia in Aigira, Achaea, which according to the explanation of the periegetes meant that in ancient times the temple had been dedicated to Iphigenia” (Paus. VII. 26. 5).” (The Cult of Artemis-Iphigenia,Ruja Popova 59) “[7.26.5] There is also a temple of Artemis, with an image of the modern style of workmanship. The priestess is a maiden, who holds office until she reaches the age to marry. There stands here too an ancient image, which the folk of Aegeira say is Iphigeneia, the daughter of Agamemnon. If they are correct, it is plain that the temple must have been built originally for Iphigeneia.” (Pausanias 7.26.5)

“Near the latter is a temple of Dionysus of the Black Goatskin. In his honor every year they hold a competition in music, and they offer prizes for swimming-races and boat-races. There is also a sanctuary of Artemis surnamed Iphigenia, and a bronze Poseidon with one foot upon a dolphin. Passing by this into the sanctuary of Hestia, we see no image, but only an altar, and they sacrifice to Hestia upon it.” (Pausanias 2.35.1)

“They say that there is also a shrine of the heroine Iphigenia; for she too according to them died in Megara. Now I have heard another account of Iphigenia that is given by Arcadians and I know that Hesiod, in his poem A Catalogue of Women, says that Iphigenia did not die, but by the will of Artemis is Hecate. With this agrees the account of Herodotus, that the Tauri near Scythia sacrifice castaways to a maiden who they say is Iphigenia, the daughter of Agamemnon. Adrastus also is honored among the Megarians, who say that he too died among them when he was leading back his army after taking Thebes, and that his death was caused by old age and the fate of Aegialeus. A sanctuary of Artemis was made by Agamemnon when he came to persuade Calchas, who dwelt in Megara, to accompany him to Troy.” (Pausanias 1.43.1) “Four ideas must be kept in mind when considering this conundrum. The first is that Herodotos did travel to the Crimea personally, and thus he was a first-hand observer of this aspect of Tauric religion. Second, the historian specifies that it is the Tauroi themselves who make this claim, not Greeks who attribute this identity to a foreign deity. Third, it is obvious that both the word “Parthenos” and the name Iphigeneia are Greek, meaning that the indigenous Tauroi were clearly sufficiently influenced by their Greek neighbors by the fifth century at the latest to have adopted a foreign identification for their own goddess. Fourth, we have virtually no indigenous evidence about Tauric religion, and thus we are unable to see the native divinity behind the Greek overlay.” (Gods and Heroes: Artemis, 123)

I think that the author here raises a good question about the quotes in Herodotus’ Histories regarding Iphigeneia in Tauris, and we don’t really have an answer yet. But what is in Herodotus’ Histories combined with Iphigeneia being mentioned more than once in Pausanias’ description of Greece shows that she was worshipped even in Greece.

Bibliography

"Artemis Titles And Epithets". Theoi.Com, 2000, https://www.theoi.com/Cult/ArtemisTitles.html. Accessed 18 Jan 2021.

"Herodotus, The Histories,Book 4, Chapter 103". Perseus.Tufts.Edu, 2021, http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus:text:1999.01.0126:book=4:chapter=103. Accessed 18 Jan 2021.

"Pausanias, Description Of Greece,Achaia, Chapter 26, Section 5". Perseus.Tufts.Edu, 2021, http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Paus.+7.26.5&fromdoc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.01.0160. Accessed 18 Jan 2021.

"Pausanias, Description Of Greece,Attica, Chapter 43, Section 1". Perseus.Tufts.Edu, 2021, http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Paus.+1.43.1. Accessed 18 Jan 2021.

"Pausanias, Description Of Greece,Corinth, Chapter 35, Section 1". Perseus.Tufts.Edu, 2021, http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Paus.+2.35.1&fromdoc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.01.0160. Accessed 18 Jan 2021.

Budin, Stephanie. Gods And Heroes-Artemis. Routledge, 2016, p. 123.

Popova, Ruja. "The Cult Of Artemis-Iphigenia In The Tauric Chersonesus: The Movement Of An Aition". Orpheus Journal Of Indo European And Thracian Studies, vol 18, 2011, p. 59., Accessed 18 Jan 2021.

29 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi! do you have any recs for someone who has never read a greek tragedy before? such as the best ones to begin with & best translations? thank you in any case. :)

i answered a similar question here a while ago but i’ve just finished a seminar on greek tragedy so i feel a little more qualified to give recommendations now! there are three classical athenian playwrights whose work survives: aeschylus (seven surviving tragedies, including the only surviving complete trilogy), sophocles (seven surviving tragedies), and euripides (eighteen surviving tragedies and one satyr play). i’ve read about half of these in translation and three in greek.

for starting out, i’d probably recommend aeschylus’s agamemnon (the first and, in my opinion, best in the oresteia trilogy) and prometheus bound, sophocles’s antigone and oedipus rex (which deal with the same family but were written a decade or so apart), and euripides’s medea and bacchae.

alternatively, you could start out with the house of atreus, a family that all three wrote plays about. aeschylus’s oresteia (agamemnon, libation bearers, and eumenides) deals with this family, and sophocles and euripides both wrote electras that cover the same material as the libation bearers but with different takes, and euripides also wrote an orestes, a characteristically euripidean take set between the libation bearers and the eumenides. anne carson combines aeschylus’s agamemnon, sophocles’s electra, and euripides’s orestes in one translation volume that she calls an oresteia. euripides also wrote two more plays about this family: iphigenia in aulis (takes place before aeschylus’s oresteia) and iphigenia among the taurians (set in a time frame after aeschylus’s oresteia). his four plays about this family aren’t meant to be taken as a consistent or coherent narrative, but it’s interesting to look at aeschylus’s trilogy and at the later plays that treat the same or adjacent subject matter. each author has different interpretations of the characterizations of the family members as well as different narratives of the course of events. fair warning though: it can be pretty exhausting to sit with this family and their trauma for long periods of time.

in terms of translations, i’m a big fan of the greek tragedy in new translations series. their concept is to either get a translator who is also a poet or to pair a classicist and a poet “based on the conviction that only translators who write poetry themselves can properly recreate the celebrated and timeless tragedies,” and i’d recommend those editions. the translations sometimes don’t end up being super literal if you look line by line, but i like them a lot. (also they generally have great introductions.) anne carson as a translator is kind of complicated and even sometimes controversial (she tends to lean more on the interpretive side of translation and parts of her translations are often easily taken out of context and reframed), but i think i really do like her work. apart from her compilation an oresteia (aeschylus’s agamemnon, sophocles’s electra, euripides’s orestes), she’s published translations of about half of euripides’s work and of sophocles’s antigone (both a more traditional translation, done for performance, and a more interpretive and artistic one titled antigonick). seamus heaney also published two translations of sophocles under different titles that i’d recommend: the cure at troy (philoctetes) and the burial at thebes (antigone).

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Riddle of the Sphinx as a Greek Tragedy

Warning – this essay includes spoilers (under the read more link)

It may be set in modern day Cambridge but in its referring to the story of the Sphinx of Thebes (and Oedipus) and its plot involving multiple revelations and betrayals, its exploration of revenge it deliberately calls back to the golden age of Greek tragedy, This is a point Steve Pemberton and Reece Shearsmith have commented on in interview, particularly to explain the episode.

As mentioned, the main story from Greek mythology that the episode references is Oedipus, specifically his banishing the Sphinx from Thebes by answering her riddle. However, it also references elements from Sophocles play ‘Oedipus Tyrannus/Rex’ and other Greek tragedies both in plot elements and how the narrative unfolds.

Firstly it is important to note that there are some major differences between this episode and Greek tragedies. For example there is no chorus commenting on the action and we see all the major action happen in front of us rather than key events happening off stage which then are relayed by a messenger, amongst other things (However it could be argued the crossword itself acts as a Greek chorus commenting on the action and as the messenger as it will tell others what has transpired between Squires and 'Nina')

However, there are a great number of ways in which this episode very accurately reproduces the practices of ancient Greek drama.

In Greek tragedy we usually see dialogues between two characters (Sophocles introduced a third actor, but we usually only see two characters interact in his and Euripides plays). We only see dialogue between Squires and Nina/Charlotte then Squires and Tyler. There are often long passages of exposition and monologues which are also echoed in this episode with Nina, Squires and Tyler all getting opportunities to explain what is happening.

The Riddle of the Sphinx (like many episodes of Inside No.9) conforms to the three Aristotelian unities for drama set out in in The Poetics. It has unity of action (it concerns Squires confrontation with Nina/Charlotte and Tyler with no subplots), unity of time (it occurs in real time over a half hour) and unity of place (Squire’s office). Indeed, almost two third of the episodes of Inside No.9 in the first four series also conform to these three unities.

The plot could be said to conform to three-episode structure of Greek tragedy with Squires and Nina/Charlotte’s initial interactions about crosswords being the first episode, Nina/Charlotte revealing her true motives being the second episode and Tyler’s arrival being the third episode. The Poetics also set out that a discovery should occur within a play and this certainly happens in The Riddle of the Sphinx!

The referencing of the myth of Oedipus in the story must be deliberate with Squires involvement with the death of his two children and sexual assault on a young woman who turns out to be his daughter echoing Oedipus unknowingly killing his father Laius and marrying his mother Jocasta.

Squire’s real crime like most characters in Greek tragedy is his ‘Hubris’ (ὑβρῐ́ς). This goes beyond our concept of pride or arrogance (both of which Squires is more than guilty of). In Greek Tragedy it is almost a form of blasphemy (certainly in the plays of Sophocles and Aeschylus) in that it is a form of disrespect for the gods and fate. Oedipus may be infamous for (unknowingly) killing his father Laius and marrying his mother Jocasta. But in Greek myth, this is not his actual crime. His and his parents were informed separately by oracles that Oedipus is fated to kill his father and marry his mother. They both take action to try and avoid this, but these actions only ensure that they occur. More pertinently it is flaws in all three’s personalities that allow these events to pass. All three act rashly or impulsively when told about the prophecy (Laius and Jocasta command baby Oedipus to be left to die, Oedipus runs away from his adopted parents). In spite of the prophecy Oedipus and Laius get into a violent argument when they encounter each other which leads to Laius’s death. So both had tempers that leads them to have violent arguments with apparently random strangers they encounter. Jocasta marries Oedipus almost immediately when he arrives in Thebes as a hero for having vanquished the sphinx even though she has only recently been widowed and he is quite literally young enough to be her son (despite the prophecy).

The plot of Sophocles’ ‘Oedipus Tyrannus/Oedipus Rex ‘occurs years into Oedipus’ rule of Thebes and concerns the eventual revelation of his actions. Throughout the play Oedipus behaves in high handed and arrogant manner toward all those around him, such as the sear Tiresias, in investigating the cause of the plague that has befallen Thebes and the circumstances of the death of Laius. He refuses to heed warnings of what he might uncover or that he may himself be the cause of the plague. This exacerbates his horror when his actions are eventually revealed. Jocasta kills herself offstage (hanging herself – with her scarf, rather like Simon had done) and Oedipus blinds himself.

It could be argued that Squires has his fate foretold him in Tyler apparently warning him that Nina/Charlotte plans to kill him. In trying to avoid this fate and not exploring why Nina/Charlotte wants him dead or Tyler’s motivation for telling him, he ensures his eventual death and that of his daughter.

Squires thinks he can outwit ‘Nina’ and that he will not be called to account for his behaviour toward others who have less power than him (Simon in the crossword quiz, the other young female undergraduates he presumably sexually assaulted). He refuses to show sympathy for those who have suffered because of his arrogance. In the end one of his victims, Tyler, will call him to account in the most horrendous manner possible.

Jacob Tyler in many ways acts in the role of the avenging god that we see frequently appear at Euripides’ tragedies (such as Dionysus in the Bacchae). These gods often reveal at the end of Euripides plays to the central figure the full consequences of their action and punish them accordingly. Tyler’s actions bring around the downfall of Squires and he exposes Squires hubris in his treatment of others. He could also be said to act as a Deus Ex Machina (a trope especially associated with Euripides) in supplying Squires with the bullet to kill himself with. However, these figures are frequently shown to be petulant and deeply cruel in Euripides’ dramas (particularly in plays such as The Bacchae and Hippolytus). Tyler is shown to be similarly cruel and petulant with no compassion toward Squires or even Nina/Charlotte who he raised as his daughter.

Jacob’s first name may be an allusion to Jacobean tragedy. Many Jacobean tragedies (also known as revenge dramas) were every bit as bloody and revenge driven as many Greek tragedies and undoubtably this was another influence on Pemberton and Shearsmith.

Professor Squires middle name Hector (revealed only at the end of the episode) may be another allusion to Greek myth. In the Iliad Hector was the Trojan warrior who kills Achilles’ companion Patroclus in battle. This evokes the wrath of Achilles (the stated theme of the Iliad) who in turn kills Hector.

One of the main themes of the Iliad and many Greek tragedies is ‘honour’ and its maintenance. Characters such a Medea are shown to go to extreme lengths when they perceive themselves as being dishonoured. Squires is determined to maintain his honour as a Crossword specialist over a young man even if it means cheating and abusing his position of power. Tyler feels he has lost his honour both by Squires cuckolding him and his resulting withdrawal from his promising academic career. Both men have an unhealthy preoccupation with their standing in the eyes of others and with being successful. Honour and excelling is linked to identity and power in Greek myth and is seen as almost conferring a form of immortality. The maintenance of honour becomes a deadly matter. Tyler can only see one way of restoring his lost honour- by avenging himself upon Squires and robbing him of his honour by exposing him to shame.

Nina/Charlotte has some interesting comparisons with two figures from Greek tragedy in Electra and Antigone. Electra and her brother Orestes’s killing of their mother Clytemnestra and stepfather Aegisthus in revenge for the murder of their father Agamemnon was the theme of plays by both Euripides and Sophocles (and the Oresteia). In Euripides’ play Electra’s desire for vengeance is met but she is then beset by guilt and regret. It is also worth notig that at least in Euripides plays Clytemnestra's killing of Agamemnon was in large part motivated by his apparent sacrifice of their daughter Iphigenia)

But Nina/Charlotte also has some parallels with Antigone, Oedipus’s daughter (who is herself the subject of a play by Sophocles). Antigone ensures her brother Polynices is given a proper burial after her uncle Creon expressly forbids anyone doing this. She is caught and punished by being entombed alive. Like Antigone, Nina/Charlotte is concerned with doing what she perceives as right by her dead brother. Her fate of being left completely paralysed while dying a slow death could be said to echo Antigone’s fate.

Alexandra Roach gives a powerful performance as Nina/Charlotte showing her fierce determination to avenge her brother and later her horror as the extent of Tyler’s betrayal become evident (all the more so as the character is completely paralysed – but her eyes speak volumes). She has been betrayed by both her ‘fathers’ (particularly Tyler) and her life has been lost as collateral in their power game. This echoes both Electra and Antigone having little power as women in their stories, a reflection of the highly patriarchal nature of ancient Athenian society.

There was always a clear moral purpose to Catharsis for the of any Greek tragedy. These were collective experiences whih deliberately explored religious and moral questions for the audience. To this end each play needed an act of ‘Catharsis’ (fear and pity) which Aristotle wrote was so critical to a successful drama. We get this act of catharsis. Squires is confronted with his role in the death of his two children (and the fact he assaulted his own daughter). Steve Pemberton manages to make Squires a pitiable character in the final moments of the episode. We see Squires is genuinely distraught at what he has done to Nina/Charlotte as he cradles her in her final moments. We pity Squires as a man who inadvertently destroyed the family he could have had if he had been more honest, less arrogant and less lecherous. We are also left with feelings of fear that people like Tyler are so ruthless in their quest for revenge and that our own misdeeds. The gunshot at the end resolves the action and ironically both Squires and the audience are released from the tension of the events of the episode.

The Riddle of the Sphinx may at first be nasty fun but as with much of Inside No.9 there is a moral message. Both Squires and Tyler behave in a toxic and entitled way which no one in the audience is supposed to admire. Squires may be physically destroyed by the end of the episode but Tyler is destroyed morally. Nina/Charlotte is so warped by a desire for revenge she is consumed (quite literally!) by it. All this in a story apparently about crosswords

#inside no.9#Reece Shearsmith#Steve pemberton#Alexandra Roach#Riddle of the sphinx#Oedipus#Euripides#sophocles

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Children of Atreus

Let's talk a bit about the coolest of the mythological Greeks, the children of Atreus - Agamemnon, Menelaus, and Anaxabia. And let me just name three things about them that are guaranteed to make you fall in love with them.

Before that, here is a quick summary of the things that everyone already knows anyway: Menelaus is the famous king of Sparta whose wife Helen’s disappearance sparked the Trojan War. The Greeks’ troops are led by his brother, Agamemnon, king of mighty Mycenae (who, when returning from the war, gets murdered by his wife Clytemnestra). Anaxabia is their sister, and she is married to Strophius, king of Phocis.

Secondly, here are three of the (many) reasons why they are The Best:

1 - They are the best of siblings.

Obviously, they are called the Atrides (or Atreides) after their father, Atreus, who is the son of Pelops and grandson of Tantalus. That makes them part of the forever cursed family of the Tantalides. That curse manifests itself in their father’s relationship with his brother, Thyest. Atreus and Thyest come to Mycenae after they get thrown out of Elis, the territory around Olympia, for murdering their half-brother. They then quickly gain power and influence in Mycenae and use the majority of it to stab each other in the back - repeatedly and quite literally, as they both end up dead.

With role models such as these (plus the curse that Tantalus brought on his family for murdering and cooking his own son just to prove a point), it is absolutely amazing and quite heart-warming how close the Atrides are. Despite their family history of betrayal and murder, they always, ALWAYS stand by one another and support each other.

I mean, Agamemnon starts a war to end all wars to get justice for his brother, for fuck’s sake (yeah, yeah, there’s that bit about the oath of Helen; I’ll get to that later), and for that ten-year-long war they are practically joined at the hip.

And it’s not just a matter of obvious power-politics either: Agamemnon sends his son Orestes to his sister and brother-in-law in Phocis when he has to leave for war. To entrust his only male heir to them is massive proof of his trust in them, in her. Anaxabia and Strophius continue to raise Orestes as their own, and Orestes becomes best friends (and quite definitely lovers, according to my man Euripides) with their son, Pylades who supports him through thick and thin.

Pylades ends up marrying Electra, Agamemnon’s daughter, while Orestes gets wed to Hermione, Menelaus’s kid with Helen. While for today’s standards this might be a bit too incestuous for comfort, it is further proof how tightly knit that family now (in contrast to previous generations and their fondness for throwing people down wells / dismemberment) is because of the bond of the three siblings.

2 - They are strategic and diplomatic masterminds.

Agamemnon and Menelaus are often reduced to being one entitled and power-hungry dick and his arrogant but ultimately impotent little brother. While that makes them the perfect cardboard-cut-villain for everyone in need of one (such as grieving Achilles, for one) and while I enjoy Brian Cox and Brendan Gleeson as “Troy”’s villains as well as Sophocles's characterization of them in "Aias" as much as the next guy, it really doesn’t do them justice.

First of all, as for the notion that they are entitled and/or feeble: Both of them are self-made men. Not only are they (as well as Anaxabia) kids of a refugee / man living in exile, after their uncle Thyest overthrows their father and has him murdered, they have to flee from Mycenae and seek refuge in Sparta, with king Tyndareos, their future father-in-law, (step) father of Clytemnestra and Helen. From there, they not only manage to mobilize enough man power to overthrow Thyest and conquer Mycenae. They also turn Mycenae into the most influential and mightiest of all the Greeks’ kingdoms. And by proving himself over and over again, Menelaus inherits the right to the throne of Sparta from his father-in-law, while Anaxabia marries the king of Phocis, a kingdom North of the gulf of Corinth with influential Delphi right in the center.

The Atrides’s influence is not just gained by clever marriage and perseverance, however. Sure, the famous oath of Helen (in which all the kings that asked for Helen’s hand in marriage swore to protect her and her husband-to-be) is thought up by wily Odysseus. But who makes sure (for all those years before Paris) that it would be upheld? It’s not like alliances between Greek kingdoms are all that stable. And yet, the council of kings - including extremely strong-willed characters such as Achilles, Aias, and Odysseus - WORKS and works well for ten years, even under the pressure of a prolonged war. Why? It’s because Agamemnon knows how to choose advisers (such as wise Nestor), knows how to utilize the human equivalent of an eel (I am looking at you, Odysseus) etc. He is a fucking brilliant politician. (And it was his RIGHT (AND a necessity) to demand Briseis from Achilles, however much the Myrmidon may moan about it; but more about that later).

Simple proof in numbers: Three exiled kids with NOTHING; fast-forward a decade or two and you have this: Agamemnon commands the largest of the Greek fleets (100 ships). If you add to those the number of Spartan (60) and Phocian (40) ships as well, that’s a whooping 200, even if you disregard for instance the huge Cretan fleet (80) which is led by their uncle, Idomeneus. Brilliant strategists and politicians.

3 - They are so highkey EXTRA when it comes to the love department. (Well, the brothers are. Anaxabia rolls her eyes at them.)

Before I talk about the brothers and their highkey Extra relationships to their wives, let me just again go back to Anaxabia. Her marriage to Strophius is delightfully stable and uneventful and no one ends up dead (which is quite rare in Greek mythology, really). It produces delightfully stable and unproblematic children, such as the original bestest of mates, Pylades. Just think of Anaxabia and her husband just looking at each other silently at a family dinner,when her dramatic brothers and their dramatic wives start throwing food (and possibly knives) across the table. Next year, we’re doing a couple’s retreat in Delphi, my dear. I love her.

But the brothers’ marriages are equally fascinating.

Paris kidnaps Helen while Menelaus is attending his grandfather Catreus’s funeral btw - dick move, prince of Troy -, and for some reason THEIR relationship is the stuff of legends? Well, fuck that. While I have all the love in the world for one (1) flamboyant and canonically cowardly favourite of Aphrodite, let’s not forget how superglue-strong Menelaus’s bond with Helen is.

First of all, out of all the suitors for her hand in marriage, she chooses HIM without hesitation - after they must’ve known each other for years, btw considering Menelaus’s time in exile in Sparta.

And when she is suddenly gone, he mobilizes literally every available man in Greece to get her back.

That’s a matter of pride, you say? That’s because - much like Agamemnon when he demands Achilles’s prize of war, Briseis, because he had to give his own, Chryseis, back to appease Apollo - he would lose face and power (and thus massively endangering the stability of his reign and consequently the safety of his country, btw)? Sure, it’s that as well.

But.

It’s not like other kings haven’t “misplaced” a wife before. It’s not like he couldn’t simply have claimed she died. He could have. And you know what? It would have saved him from being both the laughing stock of all of Greece (“Here comes Menelaus who couldn’t hold on to his wife”) and also everyone’s favourite villain for having to go to war for him.

And later, what does he do when he finds her again - either in the ruins of Troy or in far away Egypt? Does he kill her? Does he demand a divorce?

No. They sail back to Sparta together and - and this is the kicker - rule together for many years, quite happily reunited.

He fucking loves her, and she loves him. (Okay, she might ALSO love Paris and that whole war could’ve been avoided if they just got into a poly relationship. I wouldn’t have been opposed to that either.)

The same goes for Agamemnon and his family.

Iphigenia, you yell at me in outrage? Well, the unquestioned villain in THAT story is so clearly vengeful Artemis for demanding her life in the first place. And yes, you may fight me on this.

And okay, I am having a slightly harder time explaining away Agamemnon murdering Clytemnestra’s first husband as a romantic gesture, fine. But my point is, Agamemnon’s and Clytemnestra’s relationship status throughout is clearly “it’s complicated”, it’s ENDLESSLY fascinating. Plus, Clytemnestra is such a fierce and badass (Spartan) woman who without problem competently takes care of Mycenae during the war. They are SO well suited for one another, and their relationship is brilliant, from a storytelling point of view.

So, in conclusion: Give me Rufus Sewell as Agamemnon, Dominic West as Menelaus, and Oona Chaplin as Anaxabia, and I’d watch the hell out of twenty plus seasons about the Atrides and how they feel rightfully superior to all those other Peloponnesian peasants .

The Atrides are the best. It’s just a fact.

#mythology#greek mythology#mycenae#agammnon#menelaus#anaxabia#Trojan war#iliad#atreus#aerope#thyest#strophius

77 notes

·

View notes

Note

True. Also, Euripides’ two Iphigenia plays are another case of Buzzword Bingo for the goings-on in the North with the Baratheons.

Agamemnon-Stannis needs to sacrifice his daughter after he killed a deer in a sacrilegious manner (kinslaying Renly).

Mother and daughter are lured to Aulis under the pretext of marriage (like Sansa!) when it’s for death. (Dany burning Drogo: “This is a wedding, too.”) Drama. The fanaticism of their people causes Agamemnon to relent and agree to the sacrifice. At the moment of the sacrifice, Iphigenia is replaced by a deer (Baratheon) and transported to different place, Tauris.

In the second play, in Tauris Iphigenia is reunited with a brother, Orestes, whom she initially doesn’t recognize, in a situation where she will be asked to sacrifice him. That is basically Theon and Asha in Theon’s TWOW sample chapter. Stannis is jonesing to kill Theon, Asha tells him to “give him to the tree”, to the old gods of the North. Stannis is more keen on burning him for R’hllor. Iphigenia and her brother Orestes escape together.

Maybe GRRM will mesh the two plays. Asha will free Theon and their escape triggers the sacrifice of Shireen, the deer who replaces Theon, because the fire-happy fanatics want to see royal blood burn?

Also, Randyll Tarly was skinning a deer and ripping its heart out while explaining to his son and heir Samwell why he had to take the black or be murdered, i.e. two kinds of death. Because he wasn’t worthy of touching the hilt of their special sword Heartsbane. Killing childen for special swords is a thing.

Damn, but deer are not a good sign in this universe.

Do you think stannis will either be responsible or complicit in shireen's death? I've read that this story line is similar to iliad where agaemnon sacrifice his daughter life but under pressure n influence.

You know what? I think so. Why?

Ned and Cat “sacrificed” Sansa the same way.

He knew Joffrey was not quite Right, though obviously not the extent.

“Gods, Catelyn, Sansa is only eleven,” Ned said. “And Joffrey … Joffrey is …” She finished for him. “… crown prince, and heir to the Iron Throne. And I was only twelve when my father promised me to your brother Brandon.”

(AGFOT, Catelyn II)

But for a higher purpose...

"You must," he said. "Sansa must wed Joffrey, that is clear now, we must give them no grounds to suspect our devotion. And it is past time that Arya learned the ways of a southron court. In a few years she will be of an age to marry too."

Sansa would shine in the south, Catelyn thought to herself, and the gods knew that Arya needed refinement. Reluctantly, she let go of them in her heart.

(AGOT, Catelyn II)

Like Stannis and Selyse, the father is thinking strategically, while the mother is a “true believer”. Both are hesitant but don't really doubt that they are doing the right thing.

Ned then ALSO kills Lady at the behest of an evil queen. Melisandre is described as Stannis’ “true queen”. He didn’t put up much of a fight. He later deeply regrets it. Eventually, he dies and fails at attaining the goals he had in mind while sacrificing his daughter.

Ned is not Stannis, and I don’t hate Ned, but that parallel is there and it hints at ugly things.

70 notes

·

View notes

Text

In which I finally write a long ass post about all my grievances with the never ending shenanigans I see in the Iliad tag because I can’t take it anymore and needed to get it out tbh

Things y’all really need to stop doing, in no particular order: • Treating Clytemnestra like a Bad Bitch Feminist Icon #goals because she killed a character you don’t like. Know what she also was? Pretty hypocritical. Half her motive for killing Agamemnon is the mistreatment of their daughter, but guess what, Clytemnestra then goes on to treat 2/3 of her remaining children pretty much like shit. I suppose you could consider Electra to be an unreliable narrator in terms of her relating how coldly she was treated at home, but the facts don’t lie in that Cly let her new hubby Aegisthus pass Electra off to be married to some peasant so that she and her children would die without any power and wouldn’t be able to take revenge. It’s pretty indisputable though that her treatment of her son Orestes was flat out terrible. As a child, Orestes has to go into exile, as it’s implied Aegisthus would have had him killed otherwise. Cly just Lets This Happen. When Orestes returns to murder both her and Aegisthus as instructed by Apollo, Clytemnestra entreats him with a set of pretty flimsy excuses. Here’s a part from The Libation Bearers:

CLYTAEMESTRA Have you no regard for a parent's curse, my son?

ORESTES You brought me to birth and yet you cast me out to misery.

CLYTAEMESTRA No, surely I did not cast you out in sending you to the house of an ally.

ORESTES I was sold in disgrace, though I was born of a free father. CLYTAEMESTRA Then where is the price I got for you? ORESTES I am ashamed to reproach you with that outright.

Furthermore, she attempts to manipulate Orestes by entreating him to spare her because she is his mother, the one who nursed him, yet we know that this wasn’t actually done by her, and since a young age she has been completely absent in his life otherwise. When Orestes finally does kill her, this girl cannot even let it go at that but essentially makes sure he’s haunted by demons for the rest of his life. Talk about #petty, not even Agamemnon took it that far. So this character who's set up as like Badass Mama Bear is actually….not. Post Iphigenia at Aulis Clytemnestra is actually pretty self-serving, but not in the sort of way that should be admired. I think Clytemnestra is a great flawed character. Please no more ‘my perfect queen deserved better’ posts. I’m beggin’ ya. Read more than a summary of like 1/4th of her history and then let’s talk. • So I’m gonna follow this up with my long stewing Agamemnon Apologist rant (you: yikes me: Buckle Up). I’d like to begin this by saying we can all definitely agree that this man is a garbageboy stinkman. No arguing that. I love a good ‘Agamemnon is an asshole’ joke as much as the next guy. HOWEVER, when, when will I be free from posts that act like this character is honestly so completely one dimensional, that jokes about it comprise literally 98% of the tag. Where are the actually interesting meta posts that consider things about him beyond JUST being a dumpster of a man. For example, we know he was at least a half-decent bro. In book 4 of the Iliad, Menelaus basically scrapes his knee and Agamemnon essentially calls a T.O. on the entire war because HIS BROTHER, OK!!! Like yeah, he also includes a hilariously selfish line in that part that Menelaus can’t bite it because then he will be disgraced when he goes home, but the point stands. Further evidence of these having a tight relationship can be found in the Iphigenia at Aulis play. After the two of them have had a savage as hell argument about whether or not to sacrifice Iphigenia, taking some serious pot shots at each other, they have this exchange

MENELAUS I’ve changed, and I’ve changed because I love you, brother. I’ve changed because of my love for my mother’s son. It’s a natural thing for men with decent hearts to do the decent thing. AGAMEMNON I praise you, Menelaus for these unexpected words, proper words, words truly worthy of you. Brothers fight because of lust and because of greed in their inheritance. I hate such relationships; they bring bitter pain to all.