#the twelve brothers

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Queering kinship in "The Maiden who Seeks her Brothers" (A)

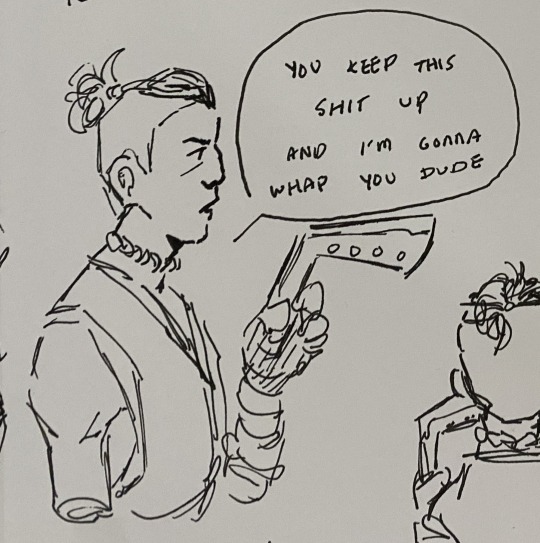

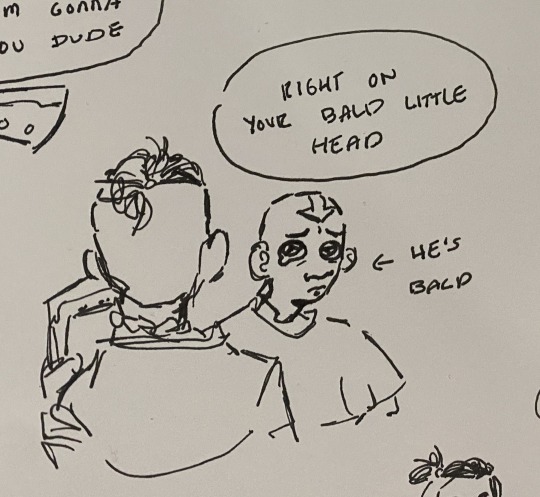

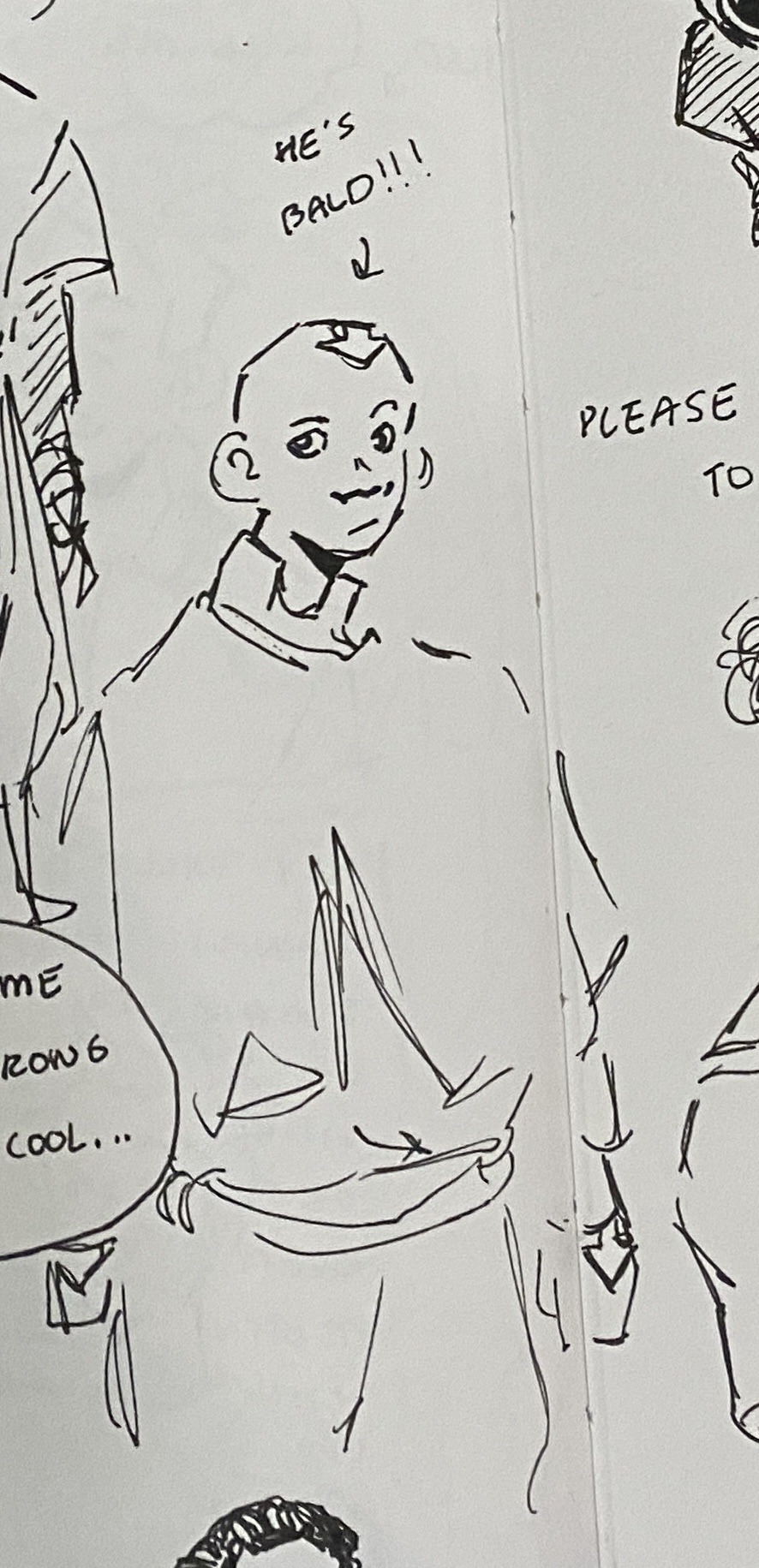

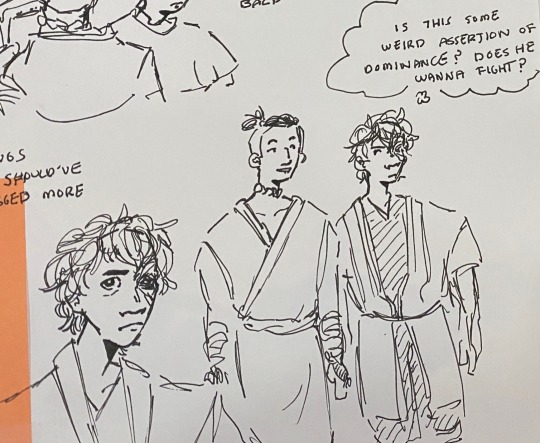

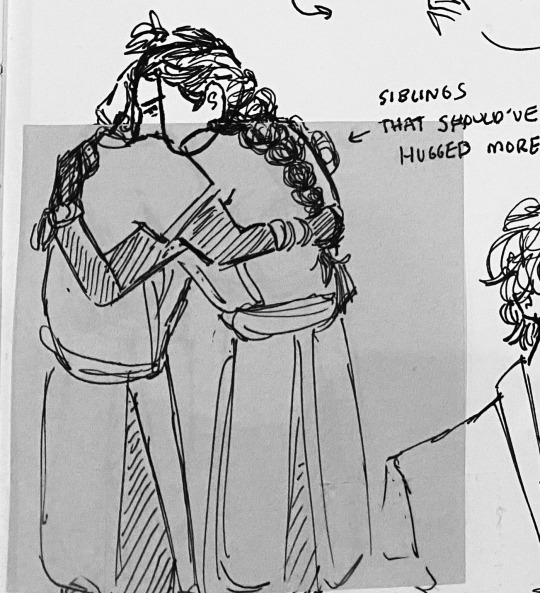

As I promised before, I will share with you some of the articles contained in the queer-reading study-book "Queering the Grimms". Due to the length of the articles and Tumblr's limitations, I will have to fragment them. Let's begin with an article from the Faux Feminities segment, called Queering Kinship in "The Maiden who Seeks her Brothers", written by Jeana Jorgensen. (Illustrations provided by me)

The fairy tales in the Kinder- und Hausmärchen, or Children’s and Household Tales, compiled by Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm are among the world’s most popular, yet they have also provoked discussion and debate regarding their authenticity, violent imagery, and restrictive gender roles. In this chapter I interpret the three versions published by the Grimm brothers of ATU 451, “The Maiden Who Seeks Her Brothers,” focusing on constructions of family, femininity, and identity. I utilize the folkloristic methodology of allomotific analysis, integrating feminist and queer theories of kinship and gender roles. I follow Pauline Greenhill by taking a queer view of fairy tale texts from the Grimms’ collection, for her use of queer implies both “its older meaning as a type of destabilizing redirection, and its more recent sense as a reference to sexualities beyond the heterosexual.” This is appropriate for her reading of “Fitcher’s Bird” (ATU 311, “Rescue by the Sister”) as a story that “subverts patriarchy, heterosexuality, femininity, and masculinity alike” (2008, 147). I will similarly demonstrate that “The Maiden Who Seeks Her Brothers” only superficially conforms to the Grimms’ patriarchal, nationalizing agenda, for the tale rather subversively critiques the nuclear family and heterosexual marriage by revealing ambiguity and ambivalence. The tale also queers biology, illuminating transbiological connections between species and a critique of reproductive futurism. Thus, through the use of fantasy, this tale and fairy tales in general can question the status quo, addressing concepts such as self, other, and home.

The first volume of the first edition of the Grimm brothers’ collection ap[1]peared in 1812, to be followed by six revisions during the brothers’ lifetimes (leading to a total of seven editions of the so-called large edition of their collection, while the so-called small edition was published in ten editions). The Grimm brothers published three versions of “The Maiden Who Seeks Her Brothers” in the 1812 edition of their collection, but the tales in that volume underwent some changes over time, as did most of the tales. This was partially in an effort to increase sales, and Wilhelm’s editorial changes in particular “tended to make the tales more proper and prudent for bourgeois audiences” (Zipes 2002b, xxxi). “The Maiden Who Seeks Her Brothers” is one of the few tale types that the Grimms published multiply, each time giving titular focus to the brothers, as the versions are titled “The Twelve Brothers” (KHM 9), “The Seven Ravens” (KHM 25), and “The Six Swans” (KHM 49). However, both Stith Thompson and Hans-Jörg Uther, in their respective 1961 and 2004 revisions of the international tale type index, call the tale type “The Maiden Who Seeks Her Brothers.” Indeed, Thompson discusses this tale in The Folktale under the category of faithfulness, par[1]ticularly faithful sisters, noting, “In spite of the minor variations . . . the tale-type is well-defined in all its major incidents” (1946, 110). Thompson also describes how the tale is found “in folktale collections from all parts of Europe” and forms the basis of three of the tales in the Grimm brothers’ collection (111).

In his Interpretation of Fairy Tales, Bengt Holbek classifies ATU 451 as a “feminine” tale, since its two main characters who wed at the end of the tale are a low-born young female and a high-born young male (the sister, though originally of noble birth in many versions, is cast out and essentially impoverished by the tale’s circumstances). Holbek notes that the role of a low-born young male in feminine tales is often filled by brothers: “The relationship between sister and brothers is characterized by love and help[1]fulness, even if fear and rivalry may also be an aspect in some tales (in AT 451, the girl is afraid of the twelve ravens; she sews shirts to disenchant them, however, and they save her from being burnt at the stake at the last moment)” (1987, 417). While Holbek conflates tale versions in this description, he is essentially correct about ATU 451; the siblings are devoted to one another, despite fearsome consequences.

The discrepancy between those titles that focus on the brothers and those that focus on the sister deserves further attention. Perhaps the Grimm brothers (and their informants?) were drawn to the more spectacular imagery of enchanted brothers. In Hans Christian Andersen’s well-known version of ATU 451, “The Wild Swans,” he too focuses on the brothers in the title. However, some scholars, including Thompson and myself, are more intrigued by the sister’s actions in the tale. Bethany Joy Bear, for instance, in her analysis of traditional and modern versions of ATU 451, concentrates on the agency of the silent sister-saviors, noting that the three versions in the Grimms’ collection “illustrate various ways of empowering the hero[1]ine. In ‘The Seven Ravens’ she saves her brothers through an active and courageous quest, while in ‘The Twelve Brothers’ and ‘The Six Swans’ her success requires redemptive silence” (2009, 45).

The three tales differ by more than just how the sister saves her brothers, though. In “The Twelve Brothers,” a king and queen with twelve boys are about to have another child; the king swears to kill the boys if the newborn is a girl so that she can inherit the kingdom. The queen warns the boys and they run away, and the girl later seeks them. She inadvertently picks flowers that turn her brothers into ravens, and in order to disenchant them she must remain silent; she may not speak or laugh for seven years. During this time, she marries a king, but his mother slanders her, and when the seven years have elapsed, she is about to be burned at the stake. At that moment, her brothers are disenchanted and returned to human form. They redeem their sister, who lives happily with her husband and her brothers.

In “The Seven Ravens,” a father exclaims that his seven negligent sons should turn into ravens for failing to bring water to baptize their newborn sister. It is unclear whether the sister remains unbaptized, thus contributing to her more liminal status. When the sister grows up, she seeks her brothers, shunning the sun and moon but gaining help from the stars, who give her a bone to unlock the glass mountain where her brothers reside. Because she loses the bone, the girl cuts off her small finger, using it to gain access to the mountain. She disenchants her brothers by simply appearing, and they all return home to live together.

In “The Six Swans,” a king is coerced into marrying a witch’s daughter, who finds where the king has stashed his children to keep them safe. The sorceress enchants the boys, turning them into swans, and the girl seeks them. She must not speak or laugh for six years and she must sew shirts from asters for them. She marries a king, but the king’s mother steals each of the three children born to the couple, smearing the wife’s mouth with blood to implicate her as a cannibal. She finishes sewing the shirts just as she’s about to be burned at the stake; then her brothers are disenchanted and come to live with the royal couple and their returned children. However, the sleeve of one shirt remained unfinished, so the littlest brother is stuck with a wing instead of an arm.

The main episodes of the tale type follow Russian folklorist Vladimir Propp’s structural sequence for fairy-tale plots: the tale begins with a villainy, the banishing and enchantment of the brothers, sometimes resulting from an interdiction that has been violated. The sister must perform a task in addition to going on a quest, and the tale ends with the formation of a new family through marriage. As Alan Dundes observes, “If Propp’s formula is valid, then the major task in fairy tales is to replace one’s original family through marriage” (1993, 124; see also Lüthi 1982). This observation holds true for heteronormative structures (such as the nuclear family), which exist in order to replicate themselves. In many fairy tales, the original nuclear family is discarded due to circumstance or choice. However, the sister in “The Maiden Who Seeks Her Brothers” has not abandoned or been removed from her old family, unlike Cinderella, who ditches her nasty stepmother and stepsisters, or Rapunzel, who is taken from her birth parents, and so on. Although, admittedly, “The Seven Ravens” does not end in marriage, I do not plan to disqualify it from analysis simply because it doesn’t fit the dominant model, as Bengt Holbek does when comparing Danish versions of “King Wivern” (ATU 433B, “King Lindorm”).1 The fact that one of the tales does not end in marriage actually supports my interpretation of the tales as transgressive, a point to which I will return later.

Dundes’s (2007) notion of allomotif helps make sense of the kinship dynamics in “The Maiden Who Seeks Her Brothers.” In order to decipher the symbolic code of folktales, Dundes proposes that any motif that could fill the same slot in a particular tale’s plot should be designated an allomotif. Further, if motif A and motif B fulfill the same purpose in moving along the tale’s plot, then they are considered mutually substitutable, thus equivalent symbolically. What this assertion means for my analysis is that all the methods by which the brothers are enchanted and subsequently disenchanted can be treated as meaningful in relation to one another. One of the advantages of comparing allomotifs rather than motifs is that we can be assured that we are analyzing not random details but significant plot components. So in “The Six Swans” and “The Seven Ravens,” we see the parental curse causing both the banishment and the enchantment of the brothers, whereas in “The Twelve Brothers,” the brothers are banished and enchanted in separate moves. Even though the brothers’ exile and enchantment happen in a different sequence in the different texts, we must view their causes as functionally parallel. Thus the ire of a father concerned for his newborn daughter, the jealous rage of a stepmother, the homicidal desire of a father to give his daughter everything, and the innocent flower gathering of a sister can all be seen as threatening to the brothers. All of these actions lead to the dispersal and enchantment of the brothers, though not all are malicious, for the sister in “The Twelve Brothers” accidentally turns her brothers into ravens by picking flowers that consequently enchant them.

I interpret this equivalence as a metaphorical statement—threats to a family’s cohesion come in all forms, from well-intentioned actions to openly malevolent curses. The father’s misdirected love for his sole daughter in two versions (“The Twelve Brothers” and “The Seven Ravens”) translates to danger to his sons. This danger is allomotifically paralleled by how the sister, without even knowing it, causes her brothers to become enchanted, either by picking flowers in “The Twelve Brothers” or through the mere incident of her birth in “The Twelve Brothers” and “The Seven Ravens.” The fact that a father would prioritize his sole daughter over numerous sons is strange and reminiscent of tales in which a father explicitly expresses romantic de[1]sire for his daughter, as in “Allerleirauh” (ATU 510B), discussed in chapter 4 by Margaret Yocom. Even in “The Six Swans,” where a stepmother with magical powers enchants the sons, the father is implicated; he did not love his children well enough to protect them from his new spouse, and once the boys had been changed into swans and fled, the father tries to take his daughter with him back to his castle (where the stepmother would likely be waiting to dispose of the daughter as well), not knowing that by asserting control over her, he would be endangering her. The father’s implied ownership of the daughter in “The Maiden Who Seeks Her Brothers” and the linking of inheritance with danger emphasize the conflicts that threaten the nuclear family. Both material and emotional resources are in limited supply in these tales, with disastrous consequences for the nuclear family, which fragments, as it does in all fairy tales (see Propp 1968).

Holbek reaches a similar conclusion in his allomotific analysis of ATU 451, though he focuses on Danish versions collected by Evald Tang Kristensen in the late nineteenth century. Holbek notes that the heroine is the actual “cause of her brothers’ expulsion in all cases, either—innocently—through being born or—inadvertently—through some act of hers” (1987, 550). The true indication of the heroine’s role in condemning her brothers is her role in saving them, despite the fact that other characters may superficially be blamed: “The heroine’s guilt is nevertheless to be deduced from the fact that only an act of hers can save her brothers.” However, Holbek reads the tale as revolving around the theme of sibling rivalry, which is more relevant to the cultural context in which Danish versions of ATU 451 were set, since the initial family situation in the tale was not always said to be royal or noble, and Holbek views the tales as reflecting the actual concerns and conditions of their peasant tellers (550; see also 406–9).2 Holbek also discusses the lack of resources that might lead to sibling rivalry, identifying physical scarcity and emotional love as two factors that could inspire tension between siblings.

The initial situation in the Grimms’ versions of “The Maiden Who Seeks Her Brothers” is also a comment on the arbitrary power that parents have over their children, the ability to withhold love or resources or both. The helplessness of children before the strong feelings of their parents is cor[1]roborated in another Grimms’ tale, “The Lazy One and the Industrious One” (Zipes 2002b, 638).3 In this tale, which Jack Zipes translated among the “omitted tales” that did not make it into any of the published editions of the KHM, a father curses his sons for insulting him, causing them to turn into ravens until a beautiful maiden kisses them. Essentially, the fam[1]ily is a site of danger, yet it is a structure that will be replicated in the tale’s conclusion . . . almost.

But first, the sister seeks her brothers and disenchants them. The symbolic equation links, in each of the three tales, the sister’s silence (neither speaking nor laughing) for six years while sewing six shirts from asters, her seven years of silence (neither speaking nor laughing), and her cutting off her finger and using it to gain entry to the glass palace where she disenchants her brothers merely by being present. The theme unifying these allomotifs is sacrifice. The sister’s loss of her finger, equivalent to the loss of her voice, is a symbolic disempowerment. One loss is a physical mutilation, which might not impair the heroine terribly much; the choice not to use her voice is arguably more drastic, since her inability to speak for herself nearly causes her death in the tales.4 Both losses could be seen as equivalent to castration.5 However, losing her ability to speak and her ability to manipulate the world around her while at the same time displaying domestic competence in sewing equates powerlessness with feminine pursuits. Bear notes that versions by both the Grimms and Hans Christian Andersen envision “a distinctly feminine savior whose work is symbolized by her spindle, an ancient emblem of women’s work” (2009, 46). Ruth Bottigheimer (1986) points out in her essay “Silenced Women in Grimms’ Tales” that the heroines in “The Twelve Brothers” and “The Six Swans” are forced to accept conditions of muteness that disempower them, which is part of a larger silencing that occurs in the tales; women both are explicitly forbidden to speak, and they have fewer declarative and interrogative speech acts attributed to them within the whole body of the Grimms’ texts.

Ironically, in performing subservient femininity, the sister fails to perform adequately as wife or mother, since the children she bears in one version (“The Six Swans”) are stolen from her. When the sister is married to the king, she gives birth to three children in succession, but each time, the king’s mother takes away the infant and smears the queen’s mouth with blood while she sleeps (Zipes 2002b, 170). Finally, the heroine is sentenced to death by a court but is unable to protest her innocence since she must not speak in order to disenchant her brothers. In being a faithful sister, the heroine cannot be a good mother and is condemned to die for it. This aspect of the tale could represent a deeply coded feminist voice.6 A tale collected and published by men might contain an implicitly coded feminist message, since the critique of patriarchal institutions such as the family would have to be buried so deeply as to not even be recognizable as a message in order to avoid detection and censorship (Radner and Lanser 1993, 6–9). The sis[1]ter in “The Six Swans” cannot perform all of the feminine duties required of her, and because she ostensibly allows her children to die, she could be accused of infanticide. Similarly, in the contemporary legend “The Inept Mother,” collected and analyzed by Janet Langlois, an overwhelmed mother’s incompetence indirectly kills one or all of her children.7 Langlois reads this legend as a coded expression of women’s frustrations at being isolated at home with too many responsibilities, a coded demand for more support than is usually given to mothers in patriarchal institutions. Essentially, the story is “complex thinking about the thinkable—protecting the child who must leave you—and about the unthinkable—being a woman not defined in relation to motherhood” (Langlois 1993, 93). The heroine in “The Six Swans” also occupies an ambiguous position, navigating different expectations of femininity, forced to choose between giving care and nurturance to some and withholding it from others.

Here, I find it productive to draw a parallel to Antigone, the daughter of Oedipus. Antigone defies the orders of her uncle Creon in order to bury her brother Polyneices and faces a death sentence as a result. Antigone’s fidelity to her blood family costs her not only her life but also her future as a productive and reproductive member of society. As Judith Butler (2000) clarifies in Antigone’s Claim: Kinship between Life and Death, Antigone transgresses both gender and kinship norms in her actions and her speech acts. Her love for her brother borders on the incestuous and exposes the incest taboo at the heart of kinship structure. Antigone’s perverse death drive for the sake of her brother, Butler asserts, is all the more monstrous because it establishes aberration at the heart of the norm (in this case the incest taboo). I see a similar logic operating in “The Maiden Who Seeks Her Brothers,” because according to allomotific equivalences, the heroine is condemned to die only in one version (“The Six Swans”) because she allegedly ate her children. In the other version that contains the marriage episode (“The Twelve Brothers”), the king’s mother slanders her, calling the maiden “godless,” and accuses her of wicked things until the king agrees to sentence her to death (Zipes 2002b, 35). As allomotific analysis reveals, in the three versions, the heroine is punished for being excessively devoted to her brothers, which is functionally the same as cannibalism and as being generally wicked (the accusation of the king’s mother in two of the versions).

In a sense, the heroine’s disproportionate devotion to her brothers kills her chance at marriage and kills her children, which from a queer stance is a comment on the performativity of sexuality and gender. According to Butler, gender performativity demonstrates “that what we take to be an internal essence of gender is manufactured through a sustained set of acts, posited through the gendered stylization of the body” ([1990] 1999, xv). This illusion, that gender and sexuality are a “being” rather than a “doing,” is constantly at risk of exposure. When sexuality is exposed as constructed rather than natural, thus threatening the whole social-sexual system of identity formation, the threat must be eliminated.

One aspect of this system particularly threatened in “The Maiden Who Seeks Her Brothers” is reproductive futurism, one form of compulsory teleological heterosexuality, “the epitome of heteronormativity’s desire to reach self-fulfillment by endlessly recycling itself through the figure of the Child” (Giffney 2008, 56; see also Edelman 2004). Reproductive futurism mandates that politics and identities be placed in service of the future and future children, utilizing the rhetoric of an idealized childhood. In his book on reproductive futurism, Lee Edelman links queerness and the death drive, stating, “The death drive names what the queer, in the order of the social, is called forth to figure: the negativity opposed to every form of social viability” (2004, 9). According to this logic, to prioritize anything other than one’s reproductive future is to refuse social viability and heteronormativity—this is what the heroine in “The Maiden Who Seeks Her Brothers” does. Her excessive emotional ties to her brothers disfigure her future, aligning her with the queer, the unlivable, and hence the ungrievable. Refusing the linear narrative of reproductive futurism registers as “unthinkable, irresponsible, inhumane” (4), words that could very well be used to describe a mother who is thought to be eating her babies and who cannot or will not speak to defend herself.

The heroine’s marriage to the king in two versions of the tale can also be examined from a queer perspective. Like the tale “Fitcher’s Bird,” which queers marriage by “showing male-female [marital] relationships as clearly fraught with danger and evil from their onset,” the Grimms’ two versions of ATU 451 that feature marriage call into question its sanctity and safety (Greenhill 2008, 150, emphasis in original). Marriage, though the ultimate goal of many fairy tales, does not provide the heroine with a supportive or nurturing environment. Bear comments that in versions of “The Maiden Who Seeks Her Brothers” wherein a king discovers and marries the heroine, “the king’s discovery brings the sister into a community that both facilitates and threatens her work. The sister’s discovery brings her into a home, foreshadowing the hoped-for happy ending, but it is a false home, determined by the king’s desire rather than by the sister’s creation of a stable and complete community” (2009, 50)

#queering the grimm#queering the grimms#queer fairytales#the maiden who seeks her brothers#the twelve brothers#the six swans#the seven ravens#grimm fairytales#fairytale analysis#fairytale type

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Anne Anderson, Golden Wonder Book, The Twelve Brothers, 1934

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

1 note

·

View note

Text

So, to anyone that doesn't know, my current main project is adapting the Grimm brothers fairytale 'The Twelve Brothers' into a musical.

it's nothing serious, and definitely not at this stage of just a completed first draft, I just really wanted a creative project to work on and had the idea to do this after I came across a Grimm fairytale collection book.

It occured to me that if I'm going to document my creative journey in a blog, I should probably document whatever it is I'm adapting! So, without further ado, may I present:

The Twelve Brothers Fairytale

as told well by the brothers Grimm, and summarized not-very-well by your obedient servant. 🤏🎩

(If this story's interesting to you, I highly advise you look it up, I had to leave out some parts to make it short enough for a post, and I will change a lot of stuff in my writing)

--------------

Once upon a time, a queen and a lunatic king were living peacefully with their twelve sons. The queen was pregnant, and would be giving birth soon.

One day, the king said to his wife: "If our next child is a girl, I'll have our twelve sons killed, so she alone inherits our wealth and our kingdom." Twelve coffins were prepared at his order.

(Listen, this is a Grimm brothers fairytale, we have to meet the quota of crazy parental figures one way or another.)

The king put the coffins in a locked room, gave the key to his wife, and told her to tell no one. The mother (obviously) grieved. Finally, her youngest son Benjamin, went to her and asked her why she was crying. She showed him the room with the coffins, saying that if their new sibling was a girl, they would be killed and buried in them.

"Don't worry, mother." The boy said, weirdly calm. "We can take care of ourselves. We'll just run away."

I'll summarize this next part, because it's a little long. Basically, four main things happen:

The brothers part ways with their mother and run away into the woods close to the castle.

They made an agreement with their mother. When she gives birth, she'll raise a flag above the castle. If the flag is white, she has given birth to a boy and they can return safely. If the flag's red, it's a girl and they're screwed.

Twelve days of flag-checking later: crap, the flag's red. Better swear that if we ever find our sister, we'll get our revenge and kill her immediately.

The brothers escape to a random hut in the woods that's just... there.

Ten years pass, the little princess grows up. When she looks through a closet, she finds twelve shirts that are too small to be her father's. She asks her mother about them, and she tells her that she has twelve brothers that ran away when she was born.

(I'm just imagining the original-fairytale-princess regularly trying to have a normal conversation with her mom and her saying the most insane things so casually)

She decides to look for her brothers, and after some time searching, finds Benjamin. He brings her back to the hut, where he tells her to hide while he convinces their brothers to not kill her. He then proceeds to younger-sibling-annoy the brothers into agreeing not to kill anyone, which is when he reveals the princess. They're all happy, and promise to live happily ever after together.

One day, the princess is foraging in the forest when she comes across twelve white lilies. She picks the flowers, hoping to give one to each of her brothers at dinnertime. As it turns out, the lilies were cursed, and when she returns to their home, she finds that her twelve brothers have been turned into ravens.

An old woman(who, again, just happens to be there) tells her that she has cursed them, and they'll be stuck like that forever unless she swears an oath to remain silent and to not smile for seven years. She swears it, finds a place to hide in for the seven years, and spins yarn as she waits.

An undisclosed amount of time later, a king finds her in her hiding place and immediately falls in love with her.

(Wait, sorry, I just need to check something... *takes out checklist* Yeah ok we reached the required amount of questionable-royals-in-a-fairytale, feel free to continue👍)

He asks whether she'd like to be his queen, and she nods. He takes her to his palace, and they are wed.

Her new mother-in-law despises the princess for literally no reason, and she tries to convince her son that the princess he married is secretly evil and needs to be executed. He doesn't believe her at first, but after she insists again and again and again and uses the fact she never speaks or smiles as 'evidence', he finally gives in and sentences his wife to death. Everyone gathers outside to burn the princess at the stake.

And just as the flames reach her... the seven years end. The curse is lifted. A murder of ravens fly down, and the moment they touch the ground they turn back into the princess's twelve brothers. They quickly put out the fire and free their little sister.

The princess, now able to speak, explains that she took the oath of remaining silent to save her brothers.

The evil mother-in-law is brutally punished for her crimes, and the princess lives happily ever after with her new family. The End!

--------------

Yeah, it's pretty simple and straightforward. It DEFINITELY needs a LOT of changes and plot hole patching, but it really caught my eye when I was reading through the Grimm book looking for material to adapt. I don't have a lot of experience with writing, I'm an amateur creator in literally every sense of the word, but I still think there's some potential in this to be turned into a different type of media.

Well, thank you for coming to my little storytime about the fairytale I like, I hope you enjoyed the past few minutes we spent together, and I hope you have a great day! :D

#The twelve brothers#grimm fairy tales#scripts are neat#musicals are neat#The Twelve Brothers Musical#grimm fairy tale#I wanted to post this yesterday but I had to do other stuff :\

1 note

·

View note

Text

Welcome to Bezirkland, where Gammelgeld the Great has bartered away his kingdom to the Reichlands, the Raven Masters flee the court, and twelve princes are left angry enough to return with an army, the only proper response to their father's cruel iron fist.

#bezirkland#fairy tales#short story#fairy tale retellings#the twelve brothers#grimm fairy tales#original story

1 note

·

View note

Text

was chatting with my brother about gravity falls (again) and i said something like “man, can you believe stan waited and worked for 30 years just for the chance to try and bring his brother back?” to which my brother responded, “yeah, it’s nuts when you think about it. i wonder if stan got trapped in the multiverse instead, if ford would do the same.” HELLO???

#my brother is out here accidentally thinking up angst on a pro level#someone get this man on ao3 please#like because what do you mean#WOULD HE??#my mind says no but my heart wants to say yes#god bless the book of bill for making us think of these things twelve years later#once again#stanley pines you will always be famous#gf#gravity falls#the book of bill#book of bill#stanley pines#stanford pines#gravity falls stanford#gravity falls stanley#bill cipher#gravity falls bill#mabel pines#dipper pines#soos ramirez#wendy corduroy#gravity falls soos#gravity falls dipper#gravity falls mabel#gravity falls theory#americanbi’s posts

7K notes

·

View notes

Text

Want to make a minor adjustment to my Steve With Much Older Siblings post from yesterday. I think it’d be a much more interesting dynamic if he’s actually their half sibling from an affair.

Their father had an affair with his secretary and then married her when she got pregnant. It broke up their family and they blamed Steve for it for years.

When they stayed over for their weekend with Dad, they were either outright cruel to him or pretended he didn’t exist. When they were old enough to stop coming over, they did. It’s only after growing up and maturing that (most of) his siblings were able to acknowledge that Steve was never at fault for their family breaking up.

They tried to mend their relationship with him, especially after realizing how absent his parents are, but by then Steve was old enough to build up his own resentment. It’s an uphill battle.

It’s a lot of actually coming around for holidays and a lot of teasing when they do. It’s actually picking the phone when the hospital calls, something that’s happening with increasing frequency.

Steve has never asked any of them for anything until one day, he shows up on Richie’s front porch smelling like death and gasoline. He’s got blood drying all over him and is visibly shaking, and Richie thinks that he’s been hurt in the earthquake but Steve barely acknowledges the concern, “I need you to represent my friend.”

“What?”

“You’re the only lawyer I know, and -“ Steve takes a big shuttering breath. “They’ll kill him, Rich. He never hurt anybody but no one will listen. They’ll lock him up and it won’t be fair, and Dustin can’t… I never ask you for anything but. But I need…”

“Eddie Munson?” He asks incredulous. “You’re friends with Eddie Munson?”

#Eddie meeting his lawyer for the first time: This is your brother? Dick?#Richie: Rich#Eddie: I’m sure you are#update made because I upset myself with my original post as a person who has a good relationship with their big age gap sister#I figure Steve’s got four siblings#the oldest is his sister Elizabeth who pretends his doesn’t exist and never comes around#and then Richie who was named after their dad. he’s a lawyer#and then Jason who was the family fuck up until Steve came along#and then Claire who is twelve years older than Steve#she’s a nurse#steve harrington#stranger things#Steve Has Older Siblings AU

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

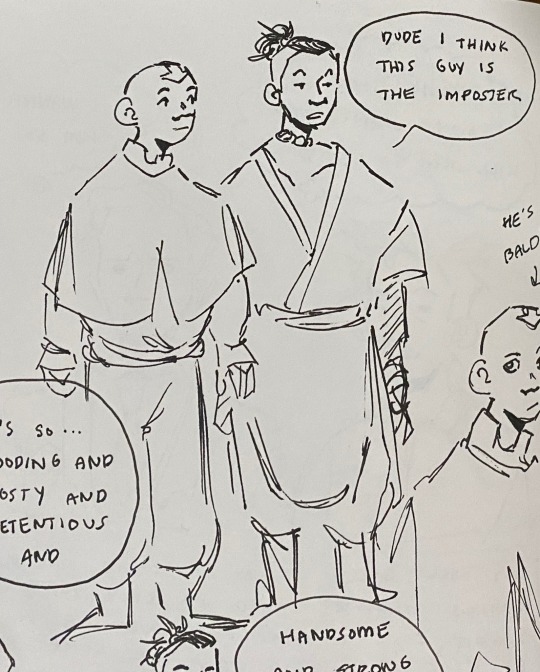

Dude I can’t believe that the avatar is bald he’s bald oh my god he’s fucking bald he’s so aerodynamic it’s crazy he’s bald ohhh nooo baaaald

#memes#my crappy art#art#kay draws#atla art#atla fanart#atla#avatar#avatar the last airbender#aang#zuko#zukka#sokka#katara#the gaang#imagine seeing this fucking twelve year old strolling down the street with his bald and shiny head#I’d lose my mind I fear#skethcbook#sketchbook#doodles#avatar aang#sokka and katara#they’re such siblings#literally the brother and sister ever

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Julian Blackthorn’s constant awareness of his siblings is both so heartwarming and so heartbreaking to read

#he really is their dad#he thinks the way a parent should think and its amazing#he is always putting them first#checking if they’re okay#making note of what they need#its so sweet knowing how much he cares about them#and how amazing of a job he has done at raising them#but man does it make me sad#because he has done it all at his own expense#the idea of raising FOUR kids from the age of twelve#on top of having your father killed and older brother taken away and sister banished#this poor boy#oh and also secretly and illegally being in love with his parabatai#and secretly running the institute and taking care of his sick uncle without ANYONE finding out#truly one of the strongest and most amazing characters in this franchise#i am always blown away at how much he is constantly taking on#i love julian blackthorn with all my heart#he is just so amazing#julian blackthorn#the dark artifices#lady midnight#the shadowhunter chronicles#shadowhunters#cassandra clare#blackthorns#emma carstairs#ty blackthorn#livvy blackthorn#tavvy blackthorn#kate's post

282 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jerk Ford AU: Silliness V

If you mean Watchdog Ford by @nowimjustastranger, whom is sometimes called "Guard Dog Ford" Those two aren't friends. They just happen to run into each other a statistically impossible amount of times in the multiverse.

Any and all reports that they've saved each other skin at least once, and hang out sometimes are just rumours spread by their mutual ally (ALLY not friend) the Anti-Ford.

If you mean Guard Ford from the AU by @skeptiql... it's their AU, I'm not imposing on it.

If there is a cosmic security guard out there monitoring the Fordverse, considering that all Jerk Ford does in the multiverse is be a total jerk to everyone and cause trouble (and then get banned from dimensions for the two aforementioned reasons), I imagine reactions to him are typically going to be:

He's not heinous, malicious, or evil, he's just a really big jerk for no good reason.

---

Me and @nowimjustastranger are in the process of proper crossover, don't worry.

In the meantime...

Pre-Weirdmageddon:

Jerk Ford: Watch, this is Stanley. Stanley, this is Watchdog Ford and Lee.

Watchdog Ford: ...

Lee: ...

Stan: Well heya pal. It's nice to see Stanford's made more friends! I knew he had it in him to be nice and compassionate.

Jerk Ford: Stanley, I swear to God.

Watchdog Ford:...You're-

Lee: You're tall.

Stan: *looks between Watchdog Ford and Jerk Ford in an exaggerated up-and-down to annoy his brother*

Stan: *to Watchdog Ford* So are you.

Lee: *grinning* Oh, we're going to get along just fine. Let's chat.

---

Watchdog Ford: You... You aren't suffering?

Stan: If you don't call grading two hundred student assignments without assistance suffering, then sure.

Lee: ...nothings wrong?

Stan: Right now, no. I did miss my brother for the thirty years he was gone. It wasn't easy... the townsfolk truly believed I murdered him, and thought that was a good thing. And then acted like I was wrong for missing him.

Lee: So everything went okay for you?

Stan: I don't know what to tell you, pal- excluding not having Stanford in my life for thirty years and the issues that comes with that, things are going fine. If I'm having trouble I can just ask someone for help, and if I have problems emotionally I have friends and family that would lend me an ear or two. Also, I am medicated and seeing a therapist for stuff.

Lee: ...

Meanwhile Jerk Ford is in the corner sipping from his #1 Big Brother mug, and Watchdog Ford gets suspiciously misty eyed.

[Dialogue primarily by @tearosepedall]

---

It's a misconception at that Jerk Ford does not experience empathy (or at least not any for anyone besides his twin brother). This misconception is one of the reasons why The Ford Hate Club is always tripped up by him - they don't understand him. They think he's unfeeling with little to no emotional intelligence.

He has a surprising amount of empathy, you can see in this post he even says that most other Fords do not hate their Stanley, what they really have is resentment.

Jerk Ford just uses that empathy to know how to get under peoples skin and really hurt their feelings. Can't hurt feelings very well if you don't know what they are or how they work!

What he does lack is compassion, as in he doesn't help, support, or uplift people. That's a Stanley thing.

---

Jerk Ford: Your attack misses.

Dipper: Misses?! With my bonuses I had a total of twenty-three to hit!

Jerk Ford: That doesn't even touch the monsters THAC0.

Dipper: THAC0? Great Uncle Ford, 3.5 Edition is over! It's armour class now!

Jerk Ford: I'm the DM, and I rule your attack misses.

Dipper: *flips the battlemap, forgetting that the infinity dice is there*

---

Jerk Ford had such a bad habit of getting engrossed into his research and study that he would overlook things like finances (and showering). Stanley managed the finances between himself and and his brother, and he did send money back to the family, not millions but it was something.

Jerk Ford also had most of the money because he had his grant, and also a few patents, but Jerk Ford only cared about anamolies and terrorizing humanity so money wasn't something he thought about very much as long as their basic needs were being met.

When he lived back in Glass Shard Beach with his family, however...

"We should go graffiti Pines Pawns."

"Hell no, dude."

"What, you scared of Old Man Pines?"

"Forget Old Man Pines, don't know know what his son did to Crampelter? We don't need to be on his sh*t list."

#Jerk Ford AU#Jerk Ford#Stanford Pines#Ford Pines#Grunkle Ford#Stanley Pines#Stan Pines#Grunkle Stan#Watchdog Ford#stcmo#guard ford#guard ford au#gravity falls#gravity falls au#People loved Stanley when they thought he committed fratricide#And then kinda turned on him when he brought Jerk Ford back#Imagine feeling guilty because you accidentally pushed your brother into an interdimensional portal#And you have no idea what happened to him#And now everyone is spreading rumours that you straight up just killed him#Also after thirty years of dealing with the Fordverse#You'd have to pry that No.1 Best Big Brother mug from Jerk Fords cold dead non-living twelve fingers

101 notes

·

View notes

Text

my outsiders musical hot take is steve being reduced to ensemble is kinda not at all that serious 🥸

#and that giving two bit a prominent role was a good choice!#i need to do like a twelve days of outsiders musical takes bc i fear i have so many#the whole story is told from an unreliable narrators pov who is also 14 and grieving#of course he doesn’t care about his big brothers best friend who doesn’t even seem to like him#obviously steve Does but similar to darry he doesn’t show it very obviously and. the kid is dense as fuck#of courseeee he’s not going to be very prominent in pony’s head!!?#also the word two-bit is said over double the amount of times as steve is in the book lollll#if this post breaches containment and i start getting hate for this i actually do not care im not dying on the steve randle hill#if u disagree good for you! thats all!

87 notes

·

View notes

Text

Queering kinship in "The Maiden who Seeks her Brothers" (B)

Continuation of the previous post! I will point out that I am not copying everything there (for example I won't include all the footnotes). If you are interested in more then you'll have to buy the book (or its PDF) :p

The manner in which the king discovers the heroine is also questionable in ATU 451. In “The Twelve Brothers,” a king comes upon the heroine while out hunting and fetches her down from the tree in which she sits; in “The Six Swans,” the king’s huntsmen carry her down from a tree after she throws down all of her clothing except for a shift, after which she is taken to the king. The implication that the heroine is actually the king’s quarry subtly exposes the workings of courtship as a hunt or chase with clearly prescribed gender roles. In both cases, the king weds her for her beauty, and the heroine silently acquiesces. The heroine is slandered in her own home, and, tellingly, her marriage is not stable until her brothers are returned to human form. As Holbek notes, “There is an intriguing connection between the brothers and the king: the heroine only wins him for good when she has disenchanted her brothers” (1987, 551). This suggests that issues with the natal family must be worked out before a new family can be successfully formed.

Anthropological methods also help to illuminate the kinship dynamics of this tale. In particular, the culture reflector theory is useful, but only to a degree, as ethnographic information about nineteenth-century German family structure is limited. More generally, European families in the nineteenth century were undergoing changes reflecting larger societal changes, which in turn influenced narrative themes at the time. Marilyn Pemberton writes, “Family structure and its internal functioning were the keys to en[1]couraging the values and behavior needed to support a modern world which was emerging at this time” (2010, 10). The family in nineteenth-century Germany faced upheavals due to industrialization, wars, and politics, as the German states were not yet unified. Jack Zipes situates the Grimms in this historical context: “The Napoleonic Wars and French rule had been upsetting to both Jacob and Wilhelm, who were dedicated to the notion of German unification” (2002b, xxvi). And yet the contributors to a book titled The German Family suggest that the socialization of children remained a central function of the family structure (Evans and Lee 1981). The German family was the main site of the education of children, with the exception of noble or bourgeois males who could be sent to school, until the late nineteenth century (Hausen 1981, 66–72). Thus we may expect to see in the tales some reflection of the family as an educational institution, even if the particular kinship dynamics of the Grimms’ historical era are still being illuminated.

Two Grimm-specific studies support this. August Nitschke (1988) uses historical documents such as autobiographies and novels to demonstrate that nineteenth-century German mothers utilized folk narratives from oral tradition to interact with their children, both as play and instruction. Ruth Bottigheimer’s (1986) historical research on the social contexts of the Grimms’ tales shows how by the nineteenth century, women’s silence had come to be a prized trait, praised in various media from children’s manuals to marriage advice. This message was in turn echoed in the Grimms’ tales, with their predominantly speechless heroines, a stark example of a social value reflected in the tales. Additionally, Bottigheimer notes that it “was generally held in Wilhelm’s time that social stability rested on a stable family structure, which the various censorship offices of the German states wished to be presented respectfully, as examples put before impressionable minds might be perceived as exerting a formative influence” (1987, 20). Thus, rigid gender roles and stable families came to be foregrounded in the Grimms’ tales.

Moving from the general reflection of social values to kinship structures in folktales, I would like to draw a parallel between German culture and Arab cultures based on how many of the tales in the Grimms’ collection feature a close brother-sister bond. The folktales Ibrahim Muhawi and Sharif Kanaana collected from Palestinian Arab women almost all feature close and loving brother-sister relationships. Muhawi and Kanaana read these relationships in light of their hypothesis that the tales present a portrait of the Arab culture, sometimes artistically distorted, but still related. Based on anthropological research, they note that the relationship between the brother and the sister is warm and harmonious in life, and it is one of the most idealized relationships in the folktale. Clearly I am not trying to imply in a reductionist fashion that German and Palestinian Arab cultures are the same, though a number of their folktale plots overlap; rather, I am stating that if we have evidence that the tales reflect kinship arrangements in one culture, then perhaps something similar is true in a culture with similar tales. Perhaps the Grimms’ tales, collected and revised in a society where families still provided an educational and nurturing setting permeated by storytelling traditions and values, contain information about how families can and should work. Sisters and brothers may have needed to cooperate to survive childhood and the natal home, and behavior that the narrative initially constructs as self-destructive might guarantee survival later on.

Hasan El-Shamy’s work on the brother-sister syndrome in Arab culture provides a second perspective on siblings in Arab folktales. In his monograph on a related tale type, ATU 872* (“Brother and Sister”), El-Shamy summarizes a number of texts and analyzes them in the context of an Arab worldview.8 What these texts have in common with “The Maiden Who Seeks Her Brothers” is that the sister-brother dyadic relationship is idealized and provides the motivation for the plot.9 However, since the brother-sister relationship is so strong emotionally as to border on the potentially incestuous, the desire of the brother and sister to be together must be worked out narratively through a plot that makes sense to its tellers and the audience so that “the tale reaches a conclusion which is emotionally comfortable for both the narrator and the listener” (1979, 76). Thus in Arab cultures, this tale type makes meaningful statements about the proper relationships between brothers and sisters, both reflecting and enforcing the cultural mandate that brothers and sisters care for one another

The brother-sister relationship in the same tale or related tales in different cultures can take on various meanings according to context; as discussed previously, Holbek interprets ATU 451 as a tale motivated by sibling rivalry, while El-Shamy interprets related tales as expressing a deep sibling love. Both scholars interpret the tales drawing on information from their respective cultures and yet reach different conclusions about the psychology underlying the tales. The importance of cultural context is thus paramount, and in the case of the Grimms’ inclusion of three versions of “The Maiden Who Seeks Her Brothers” in their collection, the life contexts of the collectors also feature prominently

The life histories of the Grimm brothers themselves influenced the shaping of this tale in very specific ways. Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm came from a family that was once affluent but become impoverished when their father died, and for much of their lives, Jacob and Wilhelm struggled to provide an adequate income on which to support their aging mother, their sister, and their four surviving brothers. Jacob never married but rather lived with Wilhelm and his wife and children (Zipes 2002b, xxiii–xxviii; see also Tatar 1987).10 The correspondence between Jacob and Wilhelm “reflects their great concern for the welfare of their family,” as did their choices in obtaining work that would allow them to care for family members who were unable to work (Zipes 2002b, xxv). Hence one reason “The Brothers Who Were Turned into Birds” appears in their collection three times could be that its message, the importance of sibling fidelity, appealed to the Grimms. Zipes comments on the brothers’ revisions of the text of “The Twelve Brothers” in particular, noting that they emphasize two factors: “the dedication of the sister and brothers to one another, and the establishment of a common, orderly household . . . where they lived together” (1988b, 216). Overall, the numerous sibling tales that the Grimms collected and revised stressed ideals “based on a sense of loss and what they felt should be retained if their own family and Germany were to be united” (218).

Though the love between (opposite-gendered) siblings is emphasized in the Grimms’ collection as a whole, as well as in their three versions of “The Maiden Who Seeks Her Brothers,” there is also ambivalence. As fundamentally human emotions, love and hate are sometimes transformations of each other, as misplaced projection or intensified identification.11 Thus Holbek’s and El-Shamy’s seemingly opposing interpretations of brother-sister tales can be reconciled, since each set of tales, in their cultural context, grapples with the question of how brother-sister relations should be. The Grimms’ tales veer more toward sibling fidelity, but there is a marked ambivalence in “The Twelve Brothers” in particular. When the sister sets out to find her twelve brothers, she encounters the youngest one first, who is overjoyed to see her. However, he tells her that the brothers vowed “that any maiden who came our way would have to die, for we had to leave our kingdom on account of a girl” (Zipes 2002b, 33). The youngest brother tricks the older brothers into agreeing not to kill the next girl they meet, after which the older brothers warmly welcome their sister into their midst. The initial hostility of the brothers toward their sister, though narratively constructed and transformed, could also represent the Grimms’ ambivalent feelings about their family: as a family that frequently suffered hardship and poverty, there must have been some strain in supporting all of their siblings. As eldest, Jacob in particular bore many of the responsibilities. Zipes notes, “It was never easy for Jacob to be both brother and father to his siblings—especially after the death of their mother, when they barely had enough money to clothe and feed themselves” (9). Including and revising brother-sister tales may thus have been a way for the Grimms to navigate their own complicated feelings toward their many siblings by achieving a narrative resolution for an initial situation fraught with resentment.

The message of sibling fidelity also upholds social norms in a patriarchal, patrilocal society, for brothers and sisters would not be competing for the same resources. In contrast, many of the Grimms’ tales (and fairy tales in general) feature competition between women for resources, a struggle that ultimately disempowers women. Maria Tatar comments on the heroines in the Grimms’ collection who, lowly by day, beautify themselves at night in dresses “that arouse the admiration of a prince and that drive rival princesses into jealous rages” (1987, 118). Classical texts of ATU 510A (“Cinderella”) in particular tend to present women competing for eligible men, portrayals that have drawn attention from feminist critics (Haase 2004a, 16, 20). Kay Stone’s reception-based research on gender roles in fairy tales reveals that readers are aware of the competition between women featured in the tales, “a competition our society seems to accept as natural” (1986, 137).

Inasmuch as “The Maiden Who Seeks Her Brothers” depicts a woman leaving her birthplace and getting married, it upholds the patriarchal mandate that anthropologist Gayle Rubin (1975) identified as “the traffic in women.” According to Rubin’s theory, men cement their homosocial bonds by exchanging women as wives, essentially as commodities. Yet in each of the versions of this tale type in the Grimms, the sister continues to live with her brothers at the tale’s conclusion. The brothers do not necessarily take wives of their own, which in two versions leads to an odd arrangement where the brothers live with their sister and her husband. The nuclear family is replicated, but with the addition of the bachelor brothers, thus altering the original family that was present at the opening of the tale. This familial constellation, which may have been recognizable to the extended family structures of nineteenth-century Germany, nonetheless does not conform to heteronormative ideas of the ideal nuclear family.12 Instead, it parallels the extraordinary image of the littlest brother in the third tale left with a wing instead of an arm because his disenchantment was incomplete—a compelling icon of fantasy penetrating reality, demanding to be made livable. The brothers form a queer appendage when added to the family unit of the heterosexual couple plus their children, and the visibly liminal status of the winged littlest brother highlights the oddness of the brothers’ inclusion

This third tale, “The Six Swans,” is more specifically woman centered and queer than the other two, as it begins with female desire (the witch ensnaring the father/king to be her daughter’s husband) and female inventiveness (the father/king’s new wife sewing and then enchanting shirts to turn the king’s sons into swans).13 The sister then defies the father/king’s authority by refusing to come with him, where the new wife is ostensibly waiting to dispose of the remainder of the unwelcome offspring. The sister wanders until she finds her brothers and undertakes to free them by remaining silent for six years while sewing them six shirts from asters. Her efforts are nearly thwarted by her new husband’s mother, who steals her children and attempts to frame her for murder. It is notable that the women in this tale who are the most active—the witch, the witch’s daughter who becomes stepmother to the siblings, and the old woman who is mother to the sister’s husband—are the most villainous. The sister, in contrast, turns her agency inward, acting on herself in order to remain silent and productive. Her agency, the most positively portrayed female agency in this tale, is thus queer in the sense that it resists and unsettles; it acts while negating action, it endures while refusing to respond to life-threatening conditions. That agency should be complex and contradictory makes sense, for, according to Butler, “If I have any agency, it is opened up by the fact that I am constituted by a social world I never chose. That my agency is riven with paradox does not mean it is impossible. It means only that paradox is the condition of its possibility” (2004, 3). The sister’s agency, so quiet as to be almost unnoticeable, is nevertheless not congruent with being silenced.

The queerness of this tale also manifests in transbiology. Judith Halberstam discusses the transbiological as manifesting in “hybrid entities or in-between states of being that represent subtle or even glaring shifts in our understandings of the body and of bodily transformation” (2008, 266). More specifically, transbiological connections “question and shift the location, the terms and the meaning of the artificial boundaries between humans, animals, machines, states of life and death, animation and reanimation, living, evolving, becoming and transforming” (266). The transitions and affinities between humans and animals in “The Maiden Who Seeks Her Brothers” interrogate the very notion of humanity as a discrete state. If the heroine’s brothers are birds, how can they still be her brothers? The tale seems to affirm a kinship between humans and animals, allowing for the possibility that family bonds transcend species divisions. The heroine herself is close to an animal state, especially during her silent time sewing in the forest. Viewing the heroine’s state from a transbiological perspective helps illuminate Bottigheimer’s statement linking muteness and sexual vulnerability, when she describes how, in “The Six Swans,” “against all contemporary logic the treed girl tries to drive off the king’s hunters by throwing her clothes down at them, piece by piece, until only her shift is left” (1987, 77). This scene does in fact make sense if the heroine is read to be in a semi-animalistic state, having renounced some of her humanity. Shedding human garments is akin to shedding social skins, layers of human identity, though her morphological stability betrays her when the king perceives her as a beautiful human female and decides to wed her

However, the fact that this remains a human-centered tale renders its subversiveness incomplete. We never learn what the brothers think and feel while they are enchanted; do they keep their sister company as she silently sews shirts for them? Do they retain any fragments of their human identities or memories while in swan or raven form? The fact that the brothers fly to where their sister is bound to a pyre, about to be immolated, suggests that they acknowledge some kind of tie to her. The brothers’ inability to use their bird beaks to form human speech parallels the sister’s silence, rendering both brothers and sister unintelligible in human terms. For the brothers to become human again, they must be framed as legibly human. Bear notes the importance of “publicly dressing the swans as human beings” in order to disenchant them in certain versions of “The Maiden Who Seeks Her Brothers” (2009, 55). In “The Six Swans,” the heroine tosses the shirts she had sewn onto the swans as they fly near the pyre to which she is bound. In “The Twelve Brothers,” the brothers as ravens swoop into the yard where the sister is about to be burned at the stake, at which point the seven years of the sister’s silence elapse. Exactly at that moment, “just as they touched the ground, they turned into her twelve brothers whom she had saved” (Zipes 2002b, 35–36). In “The Seven Ravens,” the brothers assume human form after flying into their home as ravens, and when they go to their table to eat and drink, they notice signs of the sister’s presence and exclaim, “Who’s been eating from my plate? Who’s been drinking from my cup? It was a human mouth” (92). The sister’s presence is enough to disenchant the brothers, but it is significant that her humanness causes them to comment and initiates the transformation. Thus, in each of these three tales, the brothers must reengage with human activities—wearing clothing, acknowledging their relationship with gravity and the ground, and eating in human fashion—in order to become human once again.

To explore the issues presented by these tales further, I return to the comparative method, asking why three versions of this tale type really needed to be published in one collection, and what the differences between the versions can tell us. Queer and anthropological perspectives on the brother[1]sister relationship each illuminate the meanings of tales where brothers and sisters love each other excessively—both as taboo and survival strategy. Parental love is almost always destructive, whether it is excessive fatherly love or a stepmother’s desire to be the sole loved object. We learn from the anomalous ending of the text “The Seven Ravens” that neither silence nor heterosexual marriage is required for this tale type to work as a story, to make sense narratively. In that tale, the sister disenchants her brothers when she arrives at their domicile and drops a ring into one of their cups as a recognition token, at which point the seventh brother says, “God grant us that our little sister may be here. Then we’d be saved!” (Zipes 2002b, 92). After the brothers are transformed back into humans, they “hugged and kissed each other and went happily home” (93). Here, enfolding back into the nuclear family is the happily ever after—the only price was the sister’s little finger and her sacrifice to seek her brothers. In the texts where marriage does occur, it is queered by danger and ambivalence. According to my allomotific analysis, silence is but one method of disenchantment. A sacrifice of another sort will do: the sacrifice of a “normal” marriage, the sacrifice of a reproductive future. Yet these things seem a small price to pay for the reward of a family structure, however unconventional, bonded by love and loyalty

As I’ve shown, the Grimms’ versions of “The Maiden Who Seeks Her Brothers” affirm some family values on the surface, but the texts are also radical in their suggestions for alternate ways of being. The nuclear family is critiqued as dangerous, and the formation of a new marital family does not guarantee the heroine any more safety. Greenhill describes a parallel phenomenon in the tales she analyzes in her essay: “‘Bluebeard’ and ‘The Robber Bridegroom’ queer kinship by exposing the sine qua non of heterosexual relationships—between bride and groom, husband and wife—as explicitly adversarial, dangerous, even murderous” (2008, 150). The husband in “The Maiden Who Seeks Her Brothers” (when he appears) is not dangerous through action so much as inaction, by allowing his mother to slander and threaten his wife. Both men and women are alternately active and passive in this tale type, making it difficult to state to what degree this tale type exhibits female agency, a task made even more difficult when the heroine voluntarily gives up her voice. The sister’s agency lies partially in negation and endurance, which is one way that the tale queers the notion of agency, despite the fact that in each of the three tales the sister takes the initiative and sets out on a quest to find her brothers. By simultaneously questioning the family and making it the sought-after object, the Grimms’ three versions of “The Maiden Who Seeks Her Brothers” complicate the notion of kinship, presenting myriad possibilities for how humans and non-humans can relate to and live with one another. As a story that explores and opposes lethal and idealized families, this tale investigates themes of attachment, ambivalence, and ambiguity that were central to the Grimms’ cultural context and life histories and remain relevant today.

#queering the grimm#queering the grimms#fairytale analysis#queer fairytales#the maiden who seeks her brothers#the six swans#the seven ravens#the twelve brothers#grimm fairytales#german fairytales

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

ey-🤨🤨🤨

#the inheritance games#the hawthorne legacy#the hawthorne brothers#grayson hawthorne#avery grambs#nash hawthorne#libby grambs#the brothers hawthorne#the grandest game#the final gambit#games untold#hannah the same backwards as forewards#toby hawthorne#avery kylie grambs#lyra kane#jlb#tig#tgg#lyragrayson#the naturals#dean redding#cassie hobbes#micheal townsend#sloane tavish#lia zhang#cassie x dean#dean x cassie#all in#twelve novella#bad blood

72 notes

·

View notes

Text

one small detail from the epistolary fic that no one has pointed out in the comments yet but that makes me personally go :)!!:

superboy is chris kent here (not jon!) and he's changed his name from lor-zod to lor-el :D

#literally TWICE the baby brothers for kon. except jon isn't actually mentioned this whole fic bdhjsjek#he is simply not in the public eye no one knows about superbaby (jon vc: IM TWELVE >:[!!!!!)#rimi talks#chris

74 notes

·

View notes

Text

ABYSSAL: [MERMAN! KOKUSHIBO /MICHIKATSU TSUGIKUNI X FEMALE! READER]

-> Chapter One: Purest of all

Warnings: mentions of injuries, drowning, blood and sea storm and amnesia.

The soft splash of the sea waves hugging the shore echoed throughout the land. Sea breeze brushing against their skin, acting as a reliever from the draining summer day which now came to its end with a lovely sunset. It could be considered as a reward for all the hard work done by her throughout the day. Just as the sky was being tainted in the blossoming hues of settling evening, their hearts melted with love and longing for one another. Salty waters of shore ends kissed her feet which were dangling down the wooden ramp as she was seated at the edge of it.

The maiden looked down at him. Her [eye color] orbs holding nothing but admiration and affection. For him. Her eyes comparable to that of a marble. So beautiful. So alluring as she had held him captivate under her gaze. Yet, she was unaware. Unaware of the hold she had upon him which tied his heart and soul to her. It was almost foolish that how vulnerable he felt in front of her. But he wouldn't have it the other way. As they succumbed into the moment, the only thing surrounding them was serenity.

Her hands in his.

The tender hold of her hands against his was simply blissful. Her mere presence was enough to calm the raging turmoil within him. She was the missing piece of his soul which completed the puzzle of his being. With her by his side it felt like his search for the unknown was complete.

He was complete.

A claw, embroidered with elegantly shimmering scales beneath the setting rays of sun, reached up to brush itself against the delicate texture of her cheek. She didn't flinch or tried to pry off his hand, instead she only leaned into it and smiled at him. She always managed to catch him off guard. No matter how many times she did that, it always felt new. Her reaction, it was different, different from what he had experienced throughout his life from others. He was used to the looks of fear and cowering figures beneath him. Yet, there was she, seated at the top of a wooden ramp which connected the land to the sea, gazing down at him with eyes filled with affection while he was submerged in the water as his tail helped his upper body to stay afloat upon the surface of the water.

A mutual madness, a mutual desire, and a mutual flowing emotion in the eyes as she leaned down and he leaned up slightly. Their faces inches apart. Their lips hovered over each other's lime a taunting indication of what might happen next. Senses on fire from the drug of love. Then their lips met-

Eye lids opened to reveal a pair of [eye color] iris, as cold as the ice, as shimmer-less as a rusted metal and devoid of any emotion. They were just empty. Slowly, a movement took place as they shifted to observe their surroundings. A wooden hurled room, number of barrels and a couple of ropes and fine weapons.

The vertigo of rocking from left to right sent sensations down the body of the wooden blight on its voyage towards it's next destination unknown and undisclosed towards the figure bound by the shackles of metal forged by fire and repeated beating of a mighty hammer. The rocking motion made the wooden prison creak and groan from the perpetrator responsible for it's sick cradle of motion. However unlike an infant's cradle that was supposed to bring comfort, this was anything but comforting.

Sensations from the rocking and creaking reached the numb body that slowly awoken from the deep slumber she had been in a moment ago.

COLD.

Cold was the first sensation that returned to her. Stinging her awakened flesh like a string of wasps. Hurting and painful. Second was the throbbing and pulsating sensation clawing at the side of her head making her groan. Third was pins and needles and tiredness the more her body moved. And last was the cold of the metal shackles and chains, clanking with every small movement of her body.

They sounded together echoing in the dark as her arm reached out and she flipped onto her stomach. As if to insult her small triumph, a roll of thunder and strike of lightning sounded off from above. Lighting up the strange room just for a brief moment. Letting tired confused orbs get a glimpse of what might've been a ship's storage room. Tied barrels thumped against each other as the rocking continued with a roll of thunder off the tip of the storm's violent lashing tongue.

The sounds muffled together in her ears as her vision swam about. Her ears ring. Her body stings. Her visions blur with roundabout darkness. Where was she? What had happened?

CRACK-!!

The harsh rocking back and forth increases suddenly increased from the left as a mighty wave must've crashed into this alleged ship's side. The bottom of the ship where the wave him made the floorboards push inwards briefly from the force used to smash into them. The entire room dipped right sending her rolling sideways around and around. Shackle chains clanking crazily and sounds leaving her mouth indescribable in the moment until with a final thud she collided face and stomach first into a line of crates where they leaned against the left wall. Other objects tumbled down around her thudding and crashing from the force of the ship leaning left.

A sharp hiss left her throat at the harsh welcome of the ship from her slumber. Eyes closing momentarily as she tried to take in whatever was happening.

What happened?

The answer to that question came as a sharp sting going throughout her head. Passing images were blur and negative. The train of thoughts seemingly halting at the absence of the pieces to the puzzle.

How do I get out of here?

[eye color] orbs unveiled to search through her surroundings for a way to escape the hellish torment. It was as if the fate was playing a cruel joke with her. Waking up and finding herself tied up with no idea of where she was being sailed to. The growing headache and fatigue did not help either and she found herself helpless in the clutches of a threatening situation.

But she knew she could not give up.

Not when she is in such situation.

She had to stay alive.

She promised--

Promise?

What did she promise? And to whom? The side of her head stung painfully at the attempt to recall. All she got in the response was a pulsating disturbance clawing her mind which seemed to be not her own at this moment.

Was it because of the way she was thrown around? Think. What was the last thing she remembered? She remembered...Eyes narrowed hard at the wooden floor. Her numb and fuzzy mind trying to comb through the fog which rolled over her memories. She remembered...a pain. A quick jabbing pain she had when she first passed out but that was it. She had no memory of anything else before or after that until she woke up here.

Where was here? A ship obviously. But how she got here or why was a mystery. When did she get here? Where was she heading? Judging by the rocking motion they were going somewhere. Why was she tied up? Who put her here? Her mind could only come up with blanks. Alright. Never-mind what she couldn't remember. Focus on what she does know. Firstly she was tied up. Secondly she was trapped somewhere. So her first order of business was just focusing on getting out of these shackles. Maybe there was a key somewhere.

Orbs slowly looked around at her surroundings but it was mostly dark except for the occasional lightning strike. Where would there be a ke-

THUD.

Any thought process was halted by the sounds of a loud thud. Followed shortly by more similarly sounded thuds one after another coming closer and closer and closer to the door at the far end of the room where she was.

THUD. THUD. THUD. THUD.

The sounds only halted right outside of the door as another lightning flash lit up the room from the tiny round window on the side wall. That to disappeared only to lit up the room again when the wooden door slammed open, revealing a pissed looking man holding a lantern in his hand. He was drenched, head to toe and his hair too sticking to his forehead. The storm seemingly had spat out it's wrath on him-- and his crew-mates as well since two more men soon appeared after him.

"Sir, the woman is up!"

"I too can see that, 'zander." Bit the said man as he as completely discarded any attempt to acknowledge the mentioned woman. "Just get the supplies and necessities you need and get back to work."

"Who...are you? Where am I..?!" She mustered up the courage to question the man who continued to ignore her and look around for something that might fit his needs for the situation beforehand.

"I'm talking to you!" She cried out again, a scowl plastered on her face which made her reflect on the feeling of the stick-en dried blood-path which has left a trail of red behind on the side of her face down her forehead. "Where am I being taken to?!"

Her earlier disoriented state mended into the bubbling wrath and rush of adrenaline at the sight of her abductors. The earlier fatigue momentarily forgotten at the wake of anger and disgust.

It was then that the man finally turned around snarling his disgusting yellowed teeth at the girl. The other men momentarily looked up from picking up objects and moving things to look at her. She realized her mistake when the man stomped up to her, each heavy thud with his weight until he stood in front of her. A cry of pain left her mouth as a large hand snatched up the shackles on her wrists and pulled her painfully up into the air towards the snarling face.

"Quiet you stupid wench! Little betrayers like you don't get to talk!"

A hiss left her throat as she winced from the pain. Cracking one eye open just as another crack of lightning lit up his face. Betrayer? What was he talking about?

"What are you talking about?"

"Don't play stupid. You're lucky to still be breathing where you lay."

"I'm not laying down!"

....A grin spread across his face. "You're right. My mistake. Lemme fix that."

She cried out as he let her go and with a hard thud landing on the floor at his feet. A bout of rude laughter was right after echoing throughout her already throbbing head and making her clamped her eyes shut.

Stop it. Stop it. STOP IT!!

The sounds blurring with the storm outside thundered it's way to the mind. Pounding to the point nothing but a blurring blinding ringing in her ears could be heard from the storm or from those that'll be the victims of the bring deep before their very feet.

C R A C K

The world then dipped sideways knocking all to their sides with curses and yells. Thudding along the room from the ship tilting far left. A force from the outside brutally slamming into them from the depths below.

"What was that?!"

"We must've hit a reef or collided with a whale!"

"Get to the-"

CLASH RUMBLE went the thunder and lightning as the ocean claimed.

The ship began to rock from side to side and the temperature dipped to freezing cold in their veins from bodies thudding to and from from the force. Dark clouds obscured the moon. They rocked grimly in the darkness as black as death. The full moon’s light was painted silver, casting down rays of light with a ghostly glow. Underneath the moon, the rain moved towards them ike a veil of doom knitted with pretty lace by the grim reaper's skeletal hands. A ghastly wind yelled and groaned, rippling the surface of the raged ocean.

The heaved and tossed in the rising swell and the shrieks of the men cried out as they slid from side to and from the waves.

Left. Right. Left. Right.

Then all light disappeared as the cloaked sky blotted out the light of the moon other than the occasional lightning. She shrieked herself as she slid tumbling in circles as the storm downed out their screams and some force continued to slam against the floor pushing up harder and harder with each slam.

THUD THUD THUD

The floorboards pushed up with each desperate hit.

THUD THUD THUD

Spiderweb cracks began forming in the creaking wood as it gave way.

T H U D. T H U D. T H U D.

Water began seeping through between the cracks and crevices.

C R A C K!!

Blackened liquid spurted from the opening in the floor. Water rushed out into the new opening as the space was quickly filled. Digits strong, webbed poked through as an arm raised up through the ever growing hole. Wood and splinters washing away from the being pulling itself into the opening it made. Claws ran along the bottom of the ship as they pulled the creature in and a loud hiss escaped it alongside the sounds of rushing water still pouring in around it's form and the storm outside.

C L A S H

Lightning lit up the room illuminating six glowing eyes and a maw of fangs slowly turning around to carefully scan the remains of the wooden ship and the screams of the doomed humans until with a sharp turn they met eye to eye with the frozen woman in the few seconds the lightning lit up the space. Then when darkness once again shrouded everything-

The depths of Tartarus unleashed upon them all.

The rain whipped down like a laughing audience of evil and lightning emblazoned the sky. The waves rose and she shrieked as she felt water rush over her body, scrambling back with the sounds of desperate splashes and clanking shackles. The wind blew and sped them to their doom.

The ship bobbed like a cork upon the black sea as screams and terror broke out. The depths hissed and laughed as it eagerly claimed it's victim. The oak wood planks bulged and cracked then creaked and screamed as sharpened blades and claws in unison rectified it's vengeance on the haul, port, mast, and everything making it easy for the storm and sea to do their jobs of drowning the mighty ships.