#the six swans

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

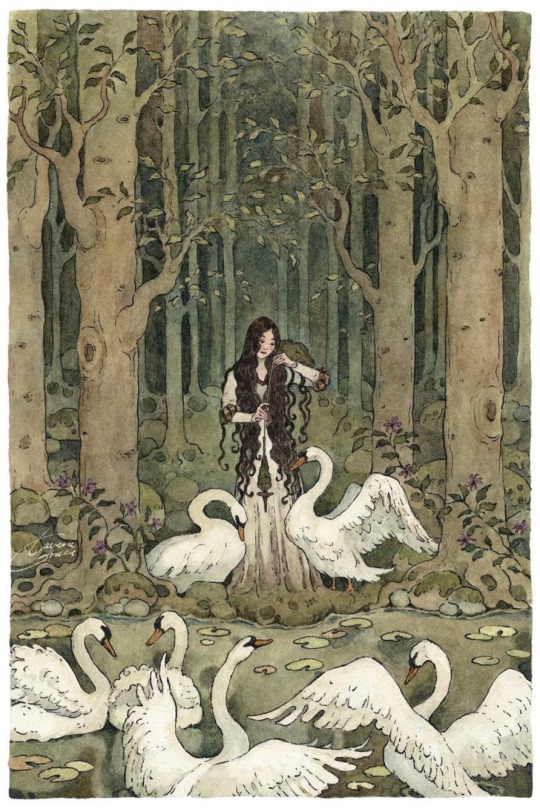

'The Six Swans', illustration from 'The Candlewick Book of Tales :by P. J. Lynch

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

The Six Swans

Artist : Patrick James Lynch

#the six swans#les six cygnes#children's literature#fairy tale#children's books#fairy story#children's book#fairy tales#fairy#p. j. lynch#patrick james lynch#brothers grimm#the brothers grimm#les frères grimm#die sechs schwäne#german fairytales#german fairy tale#prince#wing#1993

1K notes

·

View notes

Note

ok what about swan maidens are they more in of a cursed situation like werewolves?

or are they actually swans wanting human partners?

sorry my understanding of this myth creature is more from an animated movie than actual folklores

oh sincere! sincerity! oh shit i was being funny! i could've been infodumping this whole time?? fuck

swan maidens come from a variety of fairy tales, the most famous (european) one probably being Swan Lake. in that case it was a curse situation, so a sorcerer had cast a spell on them to only be women when the light of the moon touched them. the rest of the times they were swans. this is cause they ran away from arranged marriages or cheated on their boyfriends or shit (the sorcerer was a sexist read The Black Swan by mercedes lackey for an amazing adaptation of swan lake). there's also stories of boy swans though! like The Six Swans (also bc of a curse). and there's leda and the swan where zeus turns into a bird to seduce* this woman, leda.

overall i know of instances of individual characters transforming into various birds as a power they have but i dont know of any staple myths about Swan People as like. a race. maybe cause we have angels for that niche? or maybe cause we have bird ladies in the form of harpies and stuff. most stories of bird people are about curses.

AND to answer your previous question about selkies: they are a different class of "underwater person" than mermaids. mermaids are permanently half fish half person, selkies are either 100% seal or 100% person; they have a magic seal skin they put on to transform. you could trap them as humans if you steal it. a lot of stories about them center around fishermen trapping them as their wives. 👎

*i am using this term delicately, how consensual the sex was is up to interpretation

394 notes

·

View notes

Text

• The Six Swans •

lavera.grace

#faerie vibes#faeriecore#faerie#fairy aesthetic#fairycore#art#fae#aesthetic#faecore#fairy#the six swans#swans#fairytale aesthetic#fairytale#faerie scenery#faerie inspo#the land of faerie#fairy character#fairy vibes

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

Once upon an evil...

Today's shade of vile womanhood: The witch of "The Maiden who Seeks her Brothers"

You know this story. For some it will be Andersen's Wild Swans. For others it will be the Grimms' Six Swans. Or maybe it was The Storyteller's Three Ravens? She can be traced back all the way to the sons of Lir, and you probably met her one way or another. Not all witches turn princes into frogs...

16 notes

·

View notes

Note

What if Disney adapted the Six Swans?

Ah this is yet another fairy tale that does not need further adaptation, because the adaptation nestled in my heart is the one by Jim Henson's the Storyteller! As far as I'm concerned it gets to the core of this tale exactly. All the sisterly devotion, hopelessly romantic love, desperation and bravery in the face of cruelty are there.

This adaptation does make three notable changes to the Grimms' version:

• They changed the six swans into three ravens (taken from another tale recorded by the Grimms). This changes the aesthetic, but has no other bearing on the story.

• They take away the accusation of cannibalism when the Evil Queen kidnaps the young queen's babies, which I do not fault them for. The implied infanticied (don't worry, all three babies are saved) is bad enough.

• They give the Evil Queen extra magic and make it so that she is both the Evil Stepmother and the Evil Mother-In-Law. I personally think this is a fantastic addition. Her memory altering, beguiling magic is very unnerving and this one woman crossing paths with the poor heroine is not more or less tragic than her happening to come across two different evil queens who wish to harm her. This way there is one clear villain throughout the whole tale, which works very well. And Miranda Richardson plays a fantastic evil queen.

I just have such a soft spot for this series, just look at it:

And the narration is delightful:

"The Princess spoke three minutes too soon. And because of that her youngest brother kept one wing forever. But he didn't mind, and nor do I, and nor, my dear, should you!"

57 notes

·

View notes

Text

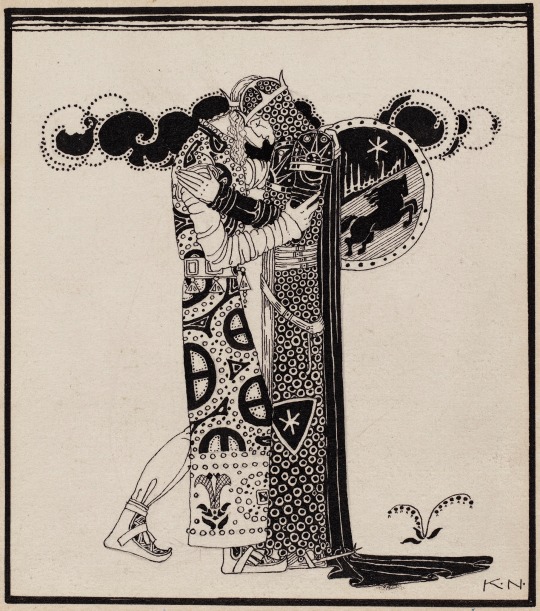

Kay Nielsen "The Six Swans” from "Red Magic: A Collection of the World’s Best Fairy Tales from All Countries" (1930)

#kay nielsen#the six swans#red magic#A Collection of the World’s Best Fairy Tales from All Countries#circa 1930

115 notes

·

View notes

Text

Then she saw a hunter's hut and went inside. She found a room with six little beds, but she did not dare to get into one of them. Instead she crawled under one of them and lay down on the hard ground where she intended to spend the night.

The sun was about to go down when she heard a rushing sound and saw six swans fly in through the window. Landing on the floor, they blew on one another, and blew all their feathers off. Then their swan-skins came off just like shirts. The girl looked at them and recognized her brothers. She was happy and crawled out from beneath the bed. The brothers were no less happy to see their little sister, but their happiness did not last long.

"You cannot stay here," they said to her. "This is a robbers' den. If they come home and find you, they will murder you."

"Can't you protect me?" asked the little sister.

"No," they answered. "We can take off our swan-skins for only a quarter hour each evening. Only during that time do we have our human forms. After that we are again transformed into swans."

Crying, the little sister said, "Can you not be redeemed?"

"Alas, no," they answered. "The conditions are too difficult. You would not be allowed to speak or to laugh for six years, and in that time you would have to sew together six little shirts from asters for us. And if a single word were to come from your mouth, all your work would be lost."

After the brothers had said this, the quarter hour was over, and they flew out the window again as swans.

Excerpt from The Six Swans by the Grimm brothers.

The Six Swans by @Lavera.grace.

#the six swans#art#fairy tales#fairytale#fairy tale art#traditional painting#literature#watercolour illustration#grimm brothers#brothers grimm#guys follow the original artists on ig her works are amazing#painting#drawing#watercolor#watercolor painting#watercolour

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Six Swans

Illustrated by Donn P. Crane for The Magic Garden (1947)

#the six swans#Donn p crane#the magic garden#my book house#olive beaupre miller#childrens illustration#children’s literature#fairy tale#nostalgia#storybook

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Here’s my piece for prompts 20 and 21 of StreamINK 2023 folktale and cursed! I’ve been rewriting a version of the classic fairytale The Six Swans on and off for a number of years and had always planned on making my own header art for it so I decided to take this opportunity!

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

excerpt from “Halfway People” by Karen Joy Fowler, published in My Mother She Killed Me, My Father He Ate Me: Forty New Fairy Tales, edited by Kate Bernheimer

#not that this makes that much sense out of the context of the full story but this part got to me#fairy tales#the six swans#time#my posts#book excerpts

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

twinklefish:

The Six Swans

100 notes

·

View notes

Text

Queering kinship in "The Maiden who Seeks her Brothers" (A)

As I promised before, I will share with you some of the articles contained in the queer-reading study-book "Queering the Grimms". Due to the length of the articles and Tumblr's limitations, I will have to fragment them. Let's begin with an article from the Faux Feminities segment, called Queering Kinship in "The Maiden who Seeks her Brothers", written by Jeana Jorgensen. (Illustrations provided by me)

The fairy tales in the Kinder- und Hausmärchen, or Children’s and Household Tales, compiled by Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm are among the world’s most popular, yet they have also provoked discussion and debate regarding their authenticity, violent imagery, and restrictive gender roles. In this chapter I interpret the three versions published by the Grimm brothers of ATU 451, “The Maiden Who Seeks Her Brothers,” focusing on constructions of family, femininity, and identity. I utilize the folkloristic methodology of allomotific analysis, integrating feminist and queer theories of kinship and gender roles. I follow Pauline Greenhill by taking a queer view of fairy tale texts from the Grimms’ collection, for her use of queer implies both “its older meaning as a type of destabilizing redirection, and its more recent sense as a reference to sexualities beyond the heterosexual.” This is appropriate for her reading of “Fitcher’s Bird” (ATU 311, “Rescue by the Sister”) as a story that “subverts patriarchy, heterosexuality, femininity, and masculinity alike” (2008, 147). I will similarly demonstrate that “The Maiden Who Seeks Her Brothers” only superficially conforms to the Grimms’ patriarchal, nationalizing agenda, for the tale rather subversively critiques the nuclear family and heterosexual marriage by revealing ambiguity and ambivalence. The tale also queers biology, illuminating transbiological connections between species and a critique of reproductive futurism. Thus, through the use of fantasy, this tale and fairy tales in general can question the status quo, addressing concepts such as self, other, and home.

The first volume of the first edition of the Grimm brothers’ collection ap[1]peared in 1812, to be followed by six revisions during the brothers’ lifetimes (leading to a total of seven editions of the so-called large edition of their collection, while the so-called small edition was published in ten editions). The Grimm brothers published three versions of “The Maiden Who Seeks Her Brothers” in the 1812 edition of their collection, but the tales in that volume underwent some changes over time, as did most of the tales. This was partially in an effort to increase sales, and Wilhelm’s editorial changes in particular “tended to make the tales more proper and prudent for bourgeois audiences” (Zipes 2002b, xxxi). “The Maiden Who Seeks Her Brothers” is one of the few tale types that the Grimms published multiply, each time giving titular focus to the brothers, as the versions are titled “The Twelve Brothers” (KHM 9), “The Seven Ravens” (KHM 25), and “The Six Swans” (KHM 49). However, both Stith Thompson and Hans-Jörg Uther, in their respective 1961 and 2004 revisions of the international tale type index, call the tale type “The Maiden Who Seeks Her Brothers.” Indeed, Thompson discusses this tale in The Folktale under the category of faithfulness, par[1]ticularly faithful sisters, noting, “In spite of the minor variations . . . the tale-type is well-defined in all its major incidents” (1946, 110). Thompson also describes how the tale is found “in folktale collections from all parts of Europe” and forms the basis of three of the tales in the Grimm brothers’ collection (111).

In his Interpretation of Fairy Tales, Bengt Holbek classifies ATU 451 as a “feminine” tale, since its two main characters who wed at the end of the tale are a low-born young female and a high-born young male (the sister, though originally of noble birth in many versions, is cast out and essentially impoverished by the tale’s circumstances). Holbek notes that the role of a low-born young male in feminine tales is often filled by brothers: “The relationship between sister and brothers is characterized by love and help[1]fulness, even if fear and rivalry may also be an aspect in some tales (in AT 451, the girl is afraid of the twelve ravens; she sews shirts to disenchant them, however, and they save her from being burnt at the stake at the last moment)” (1987, 417). While Holbek conflates tale versions in this description, he is essentially correct about ATU 451; the siblings are devoted to one another, despite fearsome consequences.

The discrepancy between those titles that focus on the brothers and those that focus on the sister deserves further attention. Perhaps the Grimm brothers (and their informants?) were drawn to the more spectacular imagery of enchanted brothers. In Hans Christian Andersen’s well-known version of ATU 451, “The Wild Swans,” he too focuses on the brothers in the title. However, some scholars, including Thompson and myself, are more intrigued by the sister’s actions in the tale. Bethany Joy Bear, for instance, in her analysis of traditional and modern versions of ATU 451, concentrates on the agency of the silent sister-saviors, noting that the three versions in the Grimms’ collection “illustrate various ways of empowering the hero[1]ine. In ‘The Seven Ravens’ she saves her brothers through an active and courageous quest, while in ‘The Twelve Brothers’ and ‘The Six Swans’ her success requires redemptive silence” (2009, 45).

The three tales differ by more than just how the sister saves her brothers, though. In “The Twelve Brothers,” a king and queen with twelve boys are about to have another child; the king swears to kill the boys if the newborn is a girl so that she can inherit the kingdom. The queen warns the boys and they run away, and the girl later seeks them. She inadvertently picks flowers that turn her brothers into ravens, and in order to disenchant them she must remain silent; she may not speak or laugh for seven years. During this time, she marries a king, but his mother slanders her, and when the seven years have elapsed, she is about to be burned at the stake. At that moment, her brothers are disenchanted and returned to human form. They redeem their sister, who lives happily with her husband and her brothers.

In “The Seven Ravens,” a father exclaims that his seven negligent sons should turn into ravens for failing to bring water to baptize their newborn sister. It is unclear whether the sister remains unbaptized, thus contributing to her more liminal status. When the sister grows up, she seeks her brothers, shunning the sun and moon but gaining help from the stars, who give her a bone to unlock the glass mountain where her brothers reside. Because she loses the bone, the girl cuts off her small finger, using it to gain access to the mountain. She disenchants her brothers by simply appearing, and they all return home to live together.

In “The Six Swans,” a king is coerced into marrying a witch’s daughter, who finds where the king has stashed his children to keep them safe. The sorceress enchants the boys, turning them into swans, and the girl seeks them. She must not speak or laugh for six years and she must sew shirts from asters for them. She marries a king, but the king’s mother steals each of the three children born to the couple, smearing the wife’s mouth with blood to implicate her as a cannibal. She finishes sewing the shirts just as she’s about to be burned at the stake; then her brothers are disenchanted and come to live with the royal couple and their returned children. However, the sleeve of one shirt remained unfinished, so the littlest brother is stuck with a wing instead of an arm.

The main episodes of the tale type follow Russian folklorist Vladimir Propp’s structural sequence for fairy-tale plots: the tale begins with a villainy, the banishing and enchantment of the brothers, sometimes resulting from an interdiction that has been violated. The sister must perform a task in addition to going on a quest, and the tale ends with the formation of a new family through marriage. As Alan Dundes observes, “If Propp’s formula is valid, then the major task in fairy tales is to replace one’s original family through marriage” (1993, 124; see also Lüthi 1982). This observation holds true for heteronormative structures (such as the nuclear family), which exist in order to replicate themselves. In many fairy tales, the original nuclear family is discarded due to circumstance or choice. However, the sister in “The Maiden Who Seeks Her Brothers” has not abandoned or been removed from her old family, unlike Cinderella, who ditches her nasty stepmother and stepsisters, or Rapunzel, who is taken from her birth parents, and so on. Although, admittedly, “The Seven Ravens” does not end in marriage, I do not plan to disqualify it from analysis simply because it doesn’t fit the dominant model, as Bengt Holbek does when comparing Danish versions of “King Wivern” (ATU 433B, “King Lindorm”).1 The fact that one of the tales does not end in marriage actually supports my interpretation of the tales as transgressive, a point to which I will return later.

Dundes’s (2007) notion of allomotif helps make sense of the kinship dynamics in “The Maiden Who Seeks Her Brothers.” In order to decipher the symbolic code of folktales, Dundes proposes that any motif that could fill the same slot in a particular tale’s plot should be designated an allomotif. Further, if motif A and motif B fulfill the same purpose in moving along the tale’s plot, then they are considered mutually substitutable, thus equivalent symbolically. What this assertion means for my analysis is that all the methods by which the brothers are enchanted and subsequently disenchanted can be treated as meaningful in relation to one another. One of the advantages of comparing allomotifs rather than motifs is that we can be assured that we are analyzing not random details but significant plot components. So in “The Six Swans” and “The Seven Ravens,” we see the parental curse causing both the banishment and the enchantment of the brothers, whereas in “The Twelve Brothers,” the brothers are banished and enchanted in separate moves. Even though the brothers’ exile and enchantment happen in a different sequence in the different texts, we must view their causes as functionally parallel. Thus the ire of a father concerned for his newborn daughter, the jealous rage of a stepmother, the homicidal desire of a father to give his daughter everything, and the innocent flower gathering of a sister can all be seen as threatening to the brothers. All of these actions lead to the dispersal and enchantment of the brothers, though not all are malicious, for the sister in “The Twelve Brothers” accidentally turns her brothers into ravens by picking flowers that consequently enchant them.

I interpret this equivalence as a metaphorical statement—threats to a family’s cohesion come in all forms, from well-intentioned actions to openly malevolent curses. The father’s misdirected love for his sole daughter in two versions (“The Twelve Brothers” and “The Seven Ravens”) translates to danger to his sons. This danger is allomotifically paralleled by how the sister, without even knowing it, causes her brothers to become enchanted, either by picking flowers in “The Twelve Brothers” or through the mere incident of her birth in “The Twelve Brothers” and “The Seven Ravens.” The fact that a father would prioritize his sole daughter over numerous sons is strange and reminiscent of tales in which a father explicitly expresses romantic de[1]sire for his daughter, as in “Allerleirauh” (ATU 510B), discussed in chapter 4 by Margaret Yocom. Even in “The Six Swans,” where a stepmother with magical powers enchants the sons, the father is implicated; he did not love his children well enough to protect them from his new spouse, and once the boys had been changed into swans and fled, the father tries to take his daughter with him back to his castle (where the stepmother would likely be waiting to dispose of the daughter as well), not knowing that by asserting control over her, he would be endangering her. The father’s implied ownership of the daughter in “The Maiden Who Seeks Her Brothers” and the linking of inheritance with danger emphasize the conflicts that threaten the nuclear family. Both material and emotional resources are in limited supply in these tales, with disastrous consequences for the nuclear family, which fragments, as it does in all fairy tales (see Propp 1968).

Holbek reaches a similar conclusion in his allomotific analysis of ATU 451, though he focuses on Danish versions collected by Evald Tang Kristensen in the late nineteenth century. Holbek notes that the heroine is the actual “cause of her brothers’ expulsion in all cases, either—innocently—through being born or—inadvertently—through some act of hers” (1987, 550). The true indication of the heroine’s role in condemning her brothers is her role in saving them, despite the fact that other characters may superficially be blamed: “The heroine’s guilt is nevertheless to be deduced from the fact that only an act of hers can save her brothers.” However, Holbek reads the tale as revolving around the theme of sibling rivalry, which is more relevant to the cultural context in which Danish versions of ATU 451 were set, since the initial family situation in the tale was not always said to be royal or noble, and Holbek views the tales as reflecting the actual concerns and conditions of their peasant tellers (550; see also 406–9).2 Holbek also discusses the lack of resources that might lead to sibling rivalry, identifying physical scarcity and emotional love as two factors that could inspire tension between siblings.

The initial situation in the Grimms’ versions of “The Maiden Who Seeks Her Brothers” is also a comment on the arbitrary power that parents have over their children, the ability to withhold love or resources or both. The helplessness of children before the strong feelings of their parents is cor[1]roborated in another Grimms’ tale, “The Lazy One and the Industrious One” (Zipes 2002b, 638).3 In this tale, which Jack Zipes translated among the “omitted tales” that did not make it into any of the published editions of the KHM, a father curses his sons for insulting him, causing them to turn into ravens until a beautiful maiden kisses them. Essentially, the fam[1]ily is a site of danger, yet it is a structure that will be replicated in the tale’s conclusion . . . almost.

But first, the sister seeks her brothers and disenchants them. The symbolic equation links, in each of the three tales, the sister’s silence (neither speaking nor laughing) for six years while sewing six shirts from asters, her seven years of silence (neither speaking nor laughing), and her cutting off her finger and using it to gain entry to the glass palace where she disenchants her brothers merely by being present. The theme unifying these allomotifs is sacrifice. The sister’s loss of her finger, equivalent to the loss of her voice, is a symbolic disempowerment. One loss is a physical mutilation, which might not impair the heroine terribly much; the choice not to use her voice is arguably more drastic, since her inability to speak for herself nearly causes her death in the tales.4 Both losses could be seen as equivalent to castration.5 However, losing her ability to speak and her ability to manipulate the world around her while at the same time displaying domestic competence in sewing equates powerlessness with feminine pursuits. Bear notes that versions by both the Grimms and Hans Christian Andersen envision “a distinctly feminine savior whose work is symbolized by her spindle, an ancient emblem of women’s work” (2009, 46). Ruth Bottigheimer (1986) points out in her essay “Silenced Women in Grimms’ Tales” that the heroines in “The Twelve Brothers” and “The Six Swans” are forced to accept conditions of muteness that disempower them, which is part of a larger silencing that occurs in the tales; women both are explicitly forbidden to speak, and they have fewer declarative and interrogative speech acts attributed to them within the whole body of the Grimms’ texts.

Ironically, in performing subservient femininity, the sister fails to perform adequately as wife or mother, since the children she bears in one version (“The Six Swans”) are stolen from her. When the sister is married to the king, she gives birth to three children in succession, but each time, the king’s mother takes away the infant and smears the queen’s mouth with blood while she sleeps (Zipes 2002b, 170). Finally, the heroine is sentenced to death by a court but is unable to protest her innocence since she must not speak in order to disenchant her brothers. In being a faithful sister, the heroine cannot be a good mother and is condemned to die for it. This aspect of the tale could represent a deeply coded feminist voice.6 A tale collected and published by men might contain an implicitly coded feminist message, since the critique of patriarchal institutions such as the family would have to be buried so deeply as to not even be recognizable as a message in order to avoid detection and censorship (Radner and Lanser 1993, 6–9). The sis[1]ter in “The Six Swans” cannot perform all of the feminine duties required of her, and because she ostensibly allows her children to die, she could be accused of infanticide. Similarly, in the contemporary legend “The Inept Mother,” collected and analyzed by Janet Langlois, an overwhelmed mother’s incompetence indirectly kills one or all of her children.7 Langlois reads this legend as a coded expression of women’s frustrations at being isolated at home with too many responsibilities, a coded demand for more support than is usually given to mothers in patriarchal institutions. Essentially, the story is “complex thinking about the thinkable—protecting the child who must leave you—and about the unthinkable—being a woman not defined in relation to motherhood” (Langlois 1993, 93). The heroine in “The Six Swans” also occupies an ambiguous position, navigating different expectations of femininity, forced to choose between giving care and nurturance to some and withholding it from others.

Here, I find it productive to draw a parallel to Antigone, the daughter of Oedipus. Antigone defies the orders of her uncle Creon in order to bury her brother Polyneices and faces a death sentence as a result. Antigone’s fidelity to her blood family costs her not only her life but also her future as a productive and reproductive member of society. As Judith Butler (2000) clarifies in Antigone’s Claim: Kinship between Life and Death, Antigone transgresses both gender and kinship norms in her actions and her speech acts. Her love for her brother borders on the incestuous and exposes the incest taboo at the heart of kinship structure. Antigone’s perverse death drive for the sake of her brother, Butler asserts, is all the more monstrous because it establishes aberration at the heart of the norm (in this case the incest taboo). I see a similar logic operating in “The Maiden Who Seeks Her Brothers,” because according to allomotific equivalences, the heroine is condemned to die only in one version (“The Six Swans”) because she allegedly ate her children. In the other version that contains the marriage episode (“The Twelve Brothers”), the king’s mother slanders her, calling the maiden “godless,” and accuses her of wicked things until the king agrees to sentence her to death (Zipes 2002b, 35). As allomotific analysis reveals, in the three versions, the heroine is punished for being excessively devoted to her brothers, which is functionally the same as cannibalism and as being generally wicked (the accusation of the king’s mother in two of the versions).

In a sense, the heroine’s disproportionate devotion to her brothers kills her chance at marriage and kills her children, which from a queer stance is a comment on the performativity of sexuality and gender. According to Butler, gender performativity demonstrates “that what we take to be an internal essence of gender is manufactured through a sustained set of acts, posited through the gendered stylization of the body” ([1990] 1999, xv). This illusion, that gender and sexuality are a “being” rather than a “doing,” is constantly at risk of exposure. When sexuality is exposed as constructed rather than natural, thus threatening the whole social-sexual system of identity formation, the threat must be eliminated.

One aspect of this system particularly threatened in “The Maiden Who Seeks Her Brothers” is reproductive futurism, one form of compulsory teleological heterosexuality, “the epitome of heteronormativity’s desire to reach self-fulfillment by endlessly recycling itself through the figure of the Child” (Giffney 2008, 56; see also Edelman 2004). Reproductive futurism mandates that politics and identities be placed in service of the future and future children, utilizing the rhetoric of an idealized childhood. In his book on reproductive futurism, Lee Edelman links queerness and the death drive, stating, “The death drive names what the queer, in the order of the social, is called forth to figure: the negativity opposed to every form of social viability” (2004, 9). According to this logic, to prioritize anything other than one’s reproductive future is to refuse social viability and heteronormativity—this is what the heroine in “The Maiden Who Seeks Her Brothers” does. Her excessive emotional ties to her brothers disfigure her future, aligning her with the queer, the unlivable, and hence the ungrievable. Refusing the linear narrative of reproductive futurism registers as “unthinkable, irresponsible, inhumane” (4), words that could very well be used to describe a mother who is thought to be eating her babies and who cannot or will not speak to defend herself.

The heroine’s marriage to the king in two versions of the tale can also be examined from a queer perspective. Like the tale “Fitcher’s Bird,” which queers marriage by “showing male-female [marital] relationships as clearly fraught with danger and evil from their onset,” the Grimms’ two versions of ATU 451 that feature marriage call into question its sanctity and safety (Greenhill 2008, 150, emphasis in original). Marriage, though the ultimate goal of many fairy tales, does not provide the heroine with a supportive or nurturing environment. Bear comments that in versions of “The Maiden Who Seeks Her Brothers” wherein a king discovers and marries the heroine, “the king’s discovery brings the sister into a community that both facilitates and threatens her work. The sister’s discovery brings her into a home, foreshadowing the hoped-for happy ending, but it is a false home, determined by the king’s desire rather than by the sister’s creation of a stable and complete community” (2009, 50)

#queering the grimm#queering the grimms#queer fairytales#the maiden who seeks her brothers#the twelve brothers#the six swans#the seven ravens#grimm fairytales#fairytale analysis#fairytale type

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

This golden crown with red stones and white pearls on is worn on Christoph m.ohrt as King in König Drosselbart - Der Schöne und das Biest (King Drosselbart and The Beauty and the Beast) 2007 and later worn on Julia Jäger as Dronning Sieglinde in The Six Swans (Die sechs Schwäne) 2012

#recycled accessories#The ProSieben Fairy Tale Hour#Die ProSieben Märchenstunde#Christoph m.ohrt#sechs auf einen streich#the six swans#die sechs schwäne#Julia Jäger#costume drama#reused jewellery#perioddramasource#dramasource

0 notes