#medieval illuminators and their methods of work

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

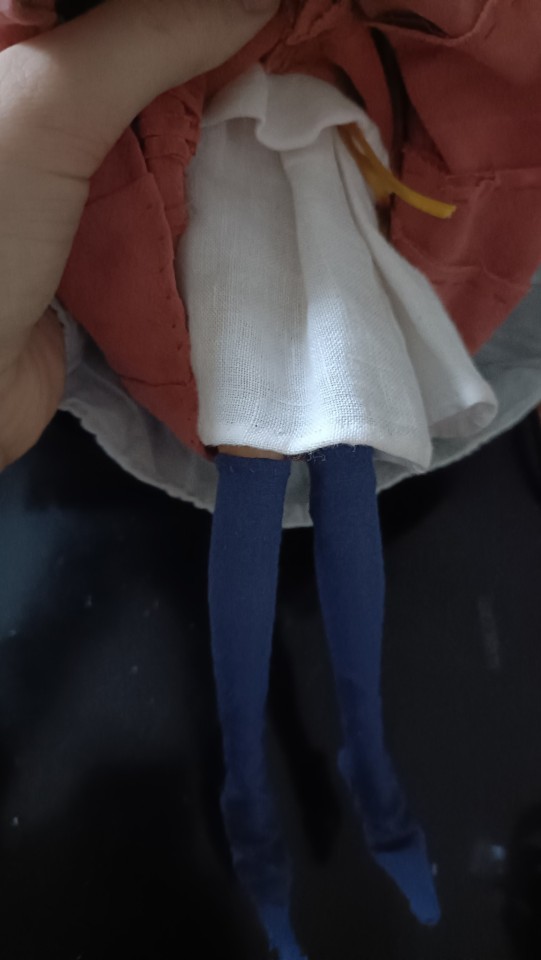

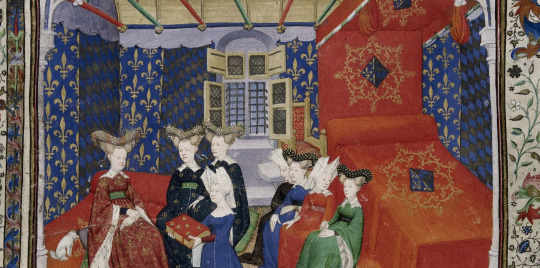

Sewing a turn of the 15th century French kirtle in doll scale

Another day, another historical doll outfit! This time it's Late Medieval. This was a popular style from about 1380-1420 France and Alpine area, but I specifically based this dress on French illuminations from the early 15th century, which mostly effects the details, like headwear. As always I hand stitched everything and stuck to historical construction methods as much as I could.

Chemise

I made a very simple chemise. The construction is based on what we know from extant finds, made out of simple rectangles and triangles, like earlier unlaced kirtles. Based on illustrations, chemise was fairly slim but unfitted enough it didn't need closures. I made it from linen, because it's not very gathered and won't bulk up too much, so I don't need to use my very fine cotton voile.

Cote

Cote is just the French word for kirtle, so appropriate here. This is the supportive layer cote, which was sort of an undergarment, but was considered fully dressed, if informal on it's own. The sleeves on this underlayer were always long and either fully fitted or gathered at the wrist. Some fitted sleeve styles had a flare at the wrist which covered the hand. The very fitted look was achieved with buttons. The silhouette was smooth and fitted, the waistline was slightly above the natural waist, though that was not as pronounced in France as in Northern Italy. Abdomen was emphasized, round lower stomach was the body ideal. The cut of the dress left plenty of room there. To fill that room I folded the chemise under the abdomen as a sort of padding. This was common to do with any kind of skirts, primarily to raise the hem when working, but why not for this purpose also? The necklines were fairly low and very wide.

I used cotton because I didn't have suitable thin enough wool that wouldn't have created too much bulk on this scale, but the cote should have been made from. The cotton is tightly woven and sells the look of a woven wool in this scale well enough for me. I didn't finish seems or line it to avoid bulk. I did give the lacing a cording to reinforce it and avoid wrinkling. The cotton was originally white, but I dyed it with iron oxide, basically rust, which at least is very much historical.

Hose

I made the hose from cotton as well for the same reasons as I did the cote. Long pointed style became fashionable around this time, as well as sewing leather soles in the bottoms of the hose instead of using shoes. Though often pattens (wooden flipflops basically) could be used when walking outside to protect the leather soles.

Cornettes or horned hair

I tied the hair with a tape on cornettes, where the volume of hair was tied on the temples to create a bit of horned appearance, especially when combined with the horned headwear. The sort of fillet which became more of a forehead loop seemed to have been tied into the hair, which I did.

Cotehardie

Cotehardie meant literally "bold cote", and in France that was what the formal outer cote was called. It was basically the same as cote, but made from more expensive materials and often had large hanging sleeves. I went with widening triangular sleeves, since they were perhaps the most popular sleeves at the time. I used fine fulled wool (verka) I had enough scraps left from. White fur was popular lining material, but obviously I can't use fur in this scale, I wish I had some light white velvet, it would have been pretty good, but I didn't. I lined the skirt and the sleeves with white cotton to imitate the look without adding too much body or extra bulk. I decorated the neckline with a simple golden trim. I thought about adding a bit of golden embroidery around it too, like seemed to have been popular, but my local crafts store had run out of golden thread so I decided to go with this only.

Accessories

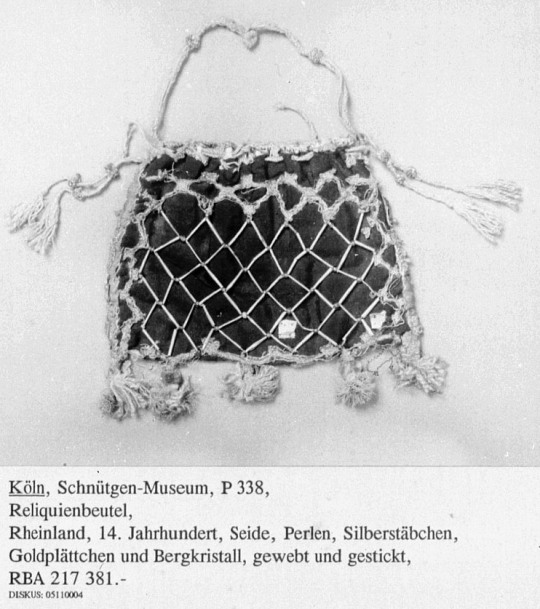

Unlike the belt used with houppelande, which was below bust, the belt used with the kirtle or cotehardie, was very low, under the abdomen to emphasize it. I went for a silk belt look, which I'm imagining is embroidered/woven with golden thread, since embroidery that small would have been too painful. I had an old broken necklace, which I could use for the metallic parts.

With the pouch I went for the tasseled drawstring look, with simple embroidery manageable in this scale. I used linen for it.

Headwear

I made her a chaperon, which likely was where the escoffion got it's beginning, escoffion being the round tube-like headwear worn on top of the head seen in several primary source images above. Early form of escoffion was becoming very popular at the time, though chaperon's were still seen on women too. Chaperon, as seen below both on the left-most woman and the man in the middle was actually just the hood rolled into a circle.

Because the horned look was popular, the escoffion and chaperon were often worn over the wired horned veil, so I first made that. I made it from cotton to make it as light as possible. It was just a square I hemmed. I just used some wire to poke out the horns from her hair and pinned the veil close from the back and onto her hair from the top.

Then I made the open hood. It was just the regular hood which had become very popular during the last century and which had ever longer narrow tip, but it was pinned and worn open, probably because of the hair style and to again create the horned look. I made if from the same cotton I made the hose, even though it too should be from wool. But it was already too bulky as it was.

And finally I could make the chaperon. Here's first chaperon without wire or veil under it and then with those. The effect isn't as pronounced as I would have hoped because the hood is too bulky, but there is an effect which is nice.

#fashion history#historical fashion#sewing#custom doll#ooak doll#fashion doll#historical sewing#medieval fashion#late medieval fashion#history#historical costuming#my art#doll customization#dollblr#dolls#doll clothes

522 notes

·

View notes

Note

Ok but the Hallewell!?!

Declan?!?!

He's so unhealthily attached I love some toxicity in fiction tbh

So his storyline is like medieval times, right? What if his heart ended up being a prince or princess or upper Nobility that couldn't usually marry commoners, you know?

What messed up method would he figure to be with his heart?? 👀

Ha

Haha

You think social rank stops him?

Tw: mass murder not detailed, death, parental death(as a possibility) blood not detailed

Hallewell are beast of nightmare, Declan is one who preys on humans with a greed of power. There's going to be ample targets within nobility for him to hunt down one by one.

When he realizes his Heart is the Queen's child, grown and of the age of courtships, he'll try to be proper... At first. Only because he wants his heart(who I'm calling you from this point cause that's the whole thing) to genuinely love him. He'll approach you the first chance he gets to see you alone. Either sneaking into a ball and finding you alone out in the gardens, trying to charm you among the flowers that tend to wilt just slightly when he breezes by... Or, what's more likely, is he'll just appear.

Probably when you're alone in the castle.

Walking down a dimly candle lit hall, most likely during a heavy storm so none can hear the sounds of his approach, and you'll hear footsteps behind you, approaching faster, the heavy fall of boots against polished stone flooring, you turn swiftly to see who has followed you and-

Nothing. A strike of lightning illuminated the dark hall through the windows, and truly there was nothing behind you.

So you turn to continue walking and almost bowl over a massive figure that's knelt before you on the ground.

A stranger, cloaked in black fabrics and leather armor, gloved hands held just under your own, softly opened, waiting to hold yours. Dark scruffy hair and stubble but the brightest gaze you've ever seen on anyone in your kingdom. Deep brown eyes that almost seem black in the dark hallway. You'd stumble back if you could, but at the motion, one large hand reaches forward, wrapping so so delicately around your lower leg, and his voice is a low rumble, an accent you cannot name-

"Step lightly, my heart. I'd hate to see you fall upon such harsh stone workings."

The hulking form before you speaks with a reference as he bows lower, carefully lifting your leg at the ankle, observing the detailed leather boot that had come unlaced somehow. He lowers himself further to dutifully tie the laces before just as gingerly placing your booted foot back on the ground with an enamored grin up to you, so very ecstatic to simply bask in your presence.

You can absolutely run away if you're uncomfortable. Declan would be hurt, but he'd follow, submissive the way a massive guard dog is. Loyal with a bite.

You could try for conversation and find this intimidating presence would crave nothing more than to sit at your feet while you rest in only the softest chair. Maybe you could even pet his head? He'd never argue if you don't want to though.

Point is, it's a fate bound meeting and I'm sorry regardless of your reaction you're forevermore stuck with this Hallewell. You can control your relationship, tell him how you view him and he'll lean into it 100% with no disappointment I mean all you have to do is look at him and he's so happy he could cry.

So take that

And then, if you care for your family, if you want things done properly, he'll try and ask for your hand or at least to court you, he'll ask the current king or queen since you're theirs.

"Your heir to the throne, I wish to court them, I wish to marry them, may I?"

If they agree? Wonderful! He'll stay his hand despite his instincts trembling with unadulterated rage at the amount of power hungry souls he ought reap in this castle. He'll redirect his attention towards fawning over and adoring you.

If they don't? Even better.

He wants a fight.

Declan is made for nothing but violence and loving you. And he is brand new to loving, but pain and hurt and violence is as familiar as breathing. He'll offer you a leash of his own making. Clip it to him and keep it tight lest he run rampant, unless you want that?

If he's refused your hand, especially if you actually do want him as well but he's barred due to social class and rank?

Declan is a creature made to kill, his prey is humans who's greed for power has grown past the point of correction. Do you know how many in nobility can fall so easily into that rank? So, he can do what he does best. He can kill.

He'll start with lower nobility, the easy pickings. Once that level has been swept clean in his eyes, he returns to the king and queen and ask again.

"Your heir to the throne, I wish to court them, I wish to marry them, may I?"

No.

He returns to mid level nobility, the killings are more brutal, more bloody, taking more time.

He returns to the king and queen to ask for your hand again.

"Your heir to the throne, I wish to court them, I wish to marry them, may I?"

This is his third time asking, and as everything comes in threes this is the last time he'll ask.

If it's no? The high level nobility is next. Tell him anyone you want spared because if you say nothing, none are spared. If they fall into his path of being too corrupt, too power hungry, too evil for redemption, which in a castle among royalty is rampant. When he feels he's made his point, he approaches the only two he's intentionally spared without you telling him to.

Declan doesn't come to the royal court, doesn't come with tidings of peace.

He comes with barely contained malice and hate

He appears in the king and queens bedchambers, fresh blood covering his form draped in darkness and what was once lifeblood. His eyes alight with the adrenaline of a life taken, his own life's purpose reinvigorated many times over. Declan stands at the foot of the queen and kings bed, watching them sleep. In his hand, a sword that's too dark to be steel, but too dark to be true steel.

For a moment he debates slaying both so none can come between you two... But to stay in your graces he waits. Instead, Declan draws his heavy boot back and kicks the bedframe, easily kicking off the corner leg, making the bed drop heavily, Jolting the sleeping pair awake. Once he has their attention, he asks again.

"Your heir to the throne, I wish to court them, I wish to marry them, may I?"

If he is told no a single more time, he will swiftly raise his sword that steams in the cold air as if pulled straight from the fires that forged it, and he will cut the head off of the one to refuse him. Amidst the fresh scent of blood and screaming of a freshly made widower, he will no longer ask, he will only inform.

"Your heir to the throne, I will court them. I will marry them. When they say the time is right, we will be together."

With this, he tips his head down, and leaves.

Let any try to stand between you at that point, he'll only slay any who attempt to do so

And if you hate him for it, that's fine! Hit him, strike him, hurt him, he'll accept it with a smile because it's you! He'll simply continue to follow you, hoping one day you'll allow him closer, he'll never force such a thing but would relish in the chance to be closer if only you allow it

#letters of yearning#x reader#gender neutral reader#monster boyfriend#monster x reader#monster romance#declan the Hallewell#my boy is fucked up alright#tw: murder#tw: death#walking red flag but he'll treat you so so sweetly just will be happy to slay anyone else

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

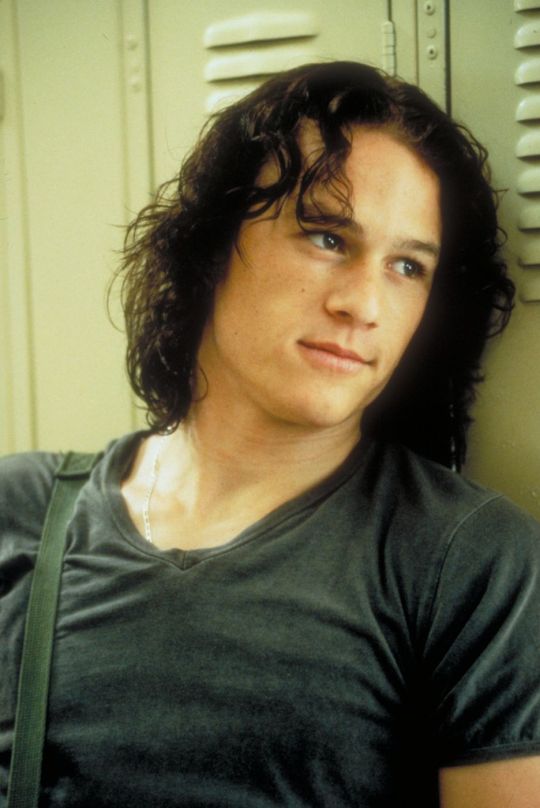

Heath Ledger: The Legendary Joker and Beyond

Introduction

In the annals of Hollywood history, certain actors shine so brightly that their brilliance continues to illuminate the industry long after they are gone. Heath Ledger, a charismatic and talented Australian actor, was undeniably one of these luminaries. From his early life to his iconic portrayal of the Joker in "The Dark Knight," Ledger left an indelible mark on the film industry and the hearts of countless fans worldwide.

Early Life and Career Beginnings

Heath Andrew Ledger was born on April 4, 1979, in Perth, Western Australia. From a young age, Ledger displayed an innate passion for the performing arts. He took his first steps into the world of acting with small roles in local theater productions and television shows.

Breakthrough Role: "10 Things I Hate About You"

It was in 1999 that Ledger secured his breakthrough role as Patrick Verona in the teen romantic comedy "10 Things I Hate About You." His magnetic screen presence and impeccable acting skills garnered critical acclaim and put him on the radar of Hollywood's major players.

Rising Stardom: "A Knight's Tale" and "The Patriot"

With his star on the rise, Ledger delivered captivating performances in the medieval adventure film "A Knight's Tale" (2001) and the historical drama "The Patriot" (2000). Audiences and critics alike took note of his versatility and ability to immerse himself fully in his characters.

The Legendary Joker: "The Dark Knight"

The year 2008 saw Ledger's career reach stratospheric heights with his portrayal of the Joker in Christopher Nolan's "The Dark Knight." Ledger's mesmerizing and chilling interpretation of the iconic Batman villain was nothing short of a revelation. He delved deep into the character's psyche, employing his unique approach to method acting to create an unforgettable, anarchic performance.

Heath Ledger's Method Acting

Heath Ledger was known for his commitment to the craft of acting, often delving deep into the minds of his characters. His preparation for the role of the Joker in "The Dark Knight" was legendary. Ledger isolated himself and maintained a diary filled with the Joker's thoughts and motivations. The result was a hauntingly realistic and unpredictable character portrayal.

Personal Life and Tragic Demise

Despite his professional success, Ledger faced personal challenges and battles with anxiety and insomnia. Tragically, on January 22, 2008, the world was shaken by the news of his untimely passing at the age of 28 due to accidental prescription drug intoxication. Hollywood mourned the loss of an exceptional talent taken too soon.

Legacy and Impact on the Film Industry

Heath Ledger's legacy lives on through his remarkable body of work. He posthumously received critical acclaim for his portrayal of the Joker and earned numerous awards, including the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor. His dedication to his craft and the raw intensity he brought to his roles continue to inspire actors and filmmakers worldwide.

Awards and Recognitions

Heath Ledger's exceptional talent did not go unnoticed during his lifetime or after his passing. In addition to his Academy Award, he received multiple prestigious awards for his roles in "The Dark Knight" and other films. Ledger's name became synonymous with excellence in acting.

Iconic Quotes and Memorable Characters

From the witty lines of Patrick Verona in "10 Things I Hate About You" to the haunting words of the Joker in "The Dark Knight," Ledger's performances gifted the world with unforgettable quotes that continue to echo in the minds of fans.

Heath Ledger's Influence on Future Actors

Heath Ledger's acting prowess and his dedication to his craft have left an enduring impact on aspiring actors. His unique approach to method acting and his fearlessness in exploring complex characters have set a high bar for future generations of performers.

Documentaries and Tributes

Numerous documentaries and tributes have been dedicated to the life and career of Heath Ledger. These projects offer an intimate look into the man behind the roles and celebrate the brilliance he brought to the silver screen.

Conclusion

Heath Ledger was not just an actor; he was an artist who had the power to touch the hearts and souls of those who watched him perform. His contribution to the film industry and the depth of his performances ensure that his memory will live on forever. Although his time in this world was tragically brief, his impact was immense and continues to inspire and captivate audiences around the globe.

FAQs

What is Heath Ledger's most famous role? Heath Ledger's most famous role was undoubtedly his portrayal of the Joker in "The Dark Knight," for which he posthumously won the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor.

How did Heath Ledger prepare for the role of the Joker? To prepare for the role of the Joker, Ledger isolated himself and immersed himself in the character's mindset, maintaining a diary filled with the Joker's thoughts and motivations.

What other awards did Heath Ledger win for his role in "The Dark Knight"? In addition to the Academy Award, Ledger received several other awards, including a Golden Globe and a BAFTA Award, for his exceptional portrayal of the Joker.

Did Heath Ledger leave behind any unfinished projects? Yes, at the time of his passing, Ledger was in the middle of filming "The Imaginarium of Doctor Parnassus," and his role was completed with the help of other actors as a tribute to him.

What is Heath Ledger's lasting legacy in the film industry? Heath Ledger's lasting legacy is his impact on acting, inspiring future generations of actors to fully commit to their characters and bring depth and authenticity to their performances.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

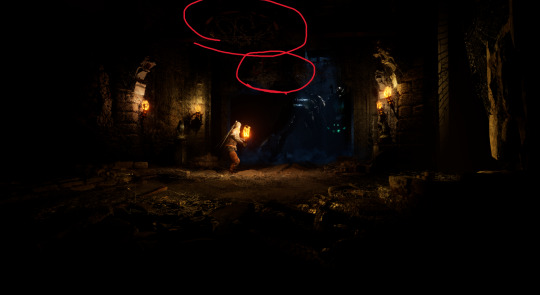

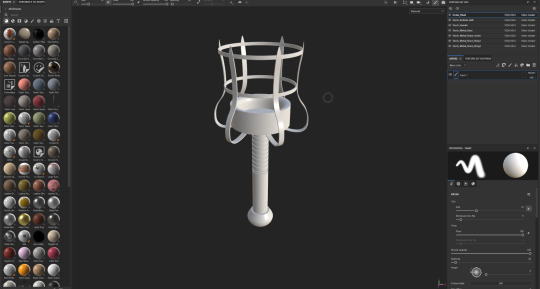

Blog Post 28: Final Project 1: Week 4 Progression

In this blog I will detail the progress made in week 4 of the final project development cycle. In this blog I will discuss the progression, including the assets created as well as the difficulties faced during the development phase.

As I sit to write this blog, I am quite shaken by the extent of progress I managed to make in one week, especially given that I also am currently working on another major project as well. The progress made was strictly related to asset generation, using Blender 3D modelling software, and texturing using Adobe Surface Painter.

Progression

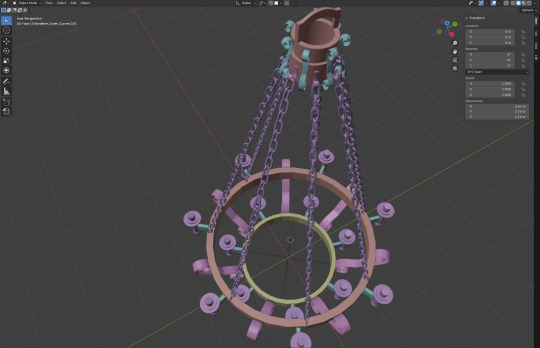

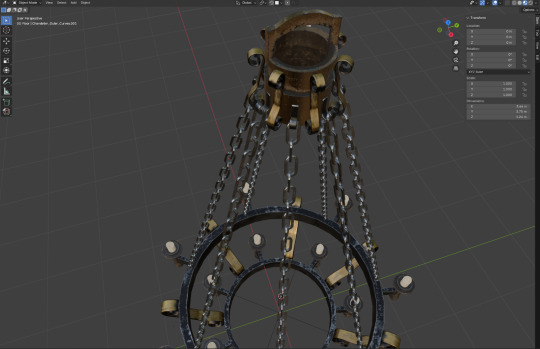

Chandelier

One of the most difficult, yet hidden, parts of this project was the chandelier that adorned the roof of the dark walkway. This is on account of the relatively low contrast, dimmed lighting and the presence of an abundance of spider webbing.

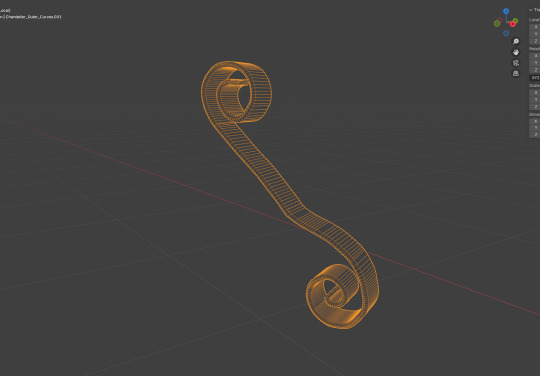

While I was, initially, suggested to create simple and seemingly undetailed chandelier models, I decided to do the opposite. Since the overall scope of the project was reduced, my goal for this project now is to focus on quality. Thus, I took inspiration from several sources and modelled a detailed chandelier in Blende

With several, highly detailed assets – including candle holders, chains, decorations and roof connectors – I decided to once again use Blender’s array modification to reproduce multiple copies of single assets in a circular iteration.

One of the problems I faced during the modeling was the creation of the spiral decoration of the chandelier. The shape of which was peculiar and required me to use a single vertex, that was then extruded to create the initial form. Using a circle, and the spiral modifier I was able to shape the edges of the decoration using “Weight Painting”, to create the spiral shape.

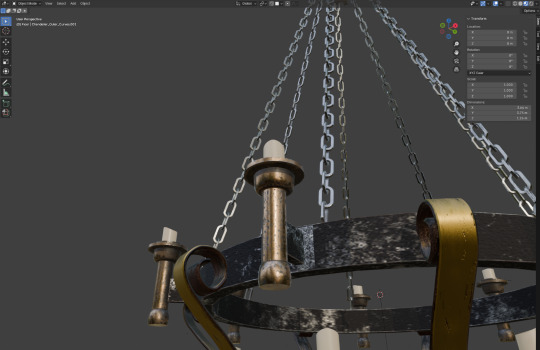

youtube

I then finished the process by texturing the model in Adobe Surface Painter. I used multiple stacking layers to recreate the old metallic colors of medieval chandeliers. Additional layers of rust and rust were added to all parts with the candles being assigned the wax textures. Copper and brass accents were used to texture the decor elements of the chandeliers. Finally, using custom brushes, rust and scratches were added to the body of the chandelier.

Torch

Central to the original scene, the torch is perhaps the most important and visible part of the original, as it was the prime method of illumination for the entire scene. To recreate the torch, I took inspiration from ancient medieval torches, used centuries ago. The metal bodies with wooden grips seemed appropriate for the atmosphere of the scene itself.

Once again, the same pattern of modelling and texturing was employed to recreate the asset.

After completing the texturing process, the torch was then placed carefully into the scene, replacing every instance in the original.

Final Thoughts:

Once again, I am extremely happy to have limited the scope of the project, as it allowed me to focus on making each asset as detailed as possible. Not only was I able to create these assets in record time, I also learnt new techniques like Weight Painting and vertex groups that allowed me to create new shapes that I did not think possible.

Plan for next week

Next week, I plan to:

Finalize the scene

Adust lighting

Change the flooring and

RESOURCES USED:

Abishek Sharma. (2024). Gothic Cathedral, Abhishek Sharma. [online] Available at: https://www.artstation.com/artwork/JrDRJz [Accessed 23 Nov. 2024].

hbitproject (2023). Mastering details in Blender - trim sheets tutorial. [online] YouTube. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1M-GNe_pB9M [Accessed 23 Nov. 2024].

SKILLS TO LEARN

Trim sheet

Improved lighting

Post processing

VFX, smoke and mist

0 notes

Text

Final Major Project Week 9

In week 9 I moved onto my second technical test, I also started creating a mock version of my puppet I could use in my other tests. For this puppet I used the wire armature method I learnt in my first year stop motion module, whilst this will work well for the tests, I think that I should invest in a professional armature for the final puppet, as Gwaine features in every scene. For the secondary characters that feature in fewer scenes and have les movement, I think that the wire armature method will suffice. I started working on my 2D animation test in class as it was the only test that didn't require the puppet, additionally, I intend to use this 2D animation style several times throughout the film and so I wanted to make sure I really had the look of it locked down. With that in mind I researched illustrations from illuminated manuscripts. For my test I am animating a man scything some wheat, a small action that will feature in the opening sequence, recounting the history of the village.

Within the week I also reworked my concept art, revisiting my initial Moodboard, I was drawn to the work of Czech illustrator Stephan Zavrel. his work features interesting perspectives, similar to that of medieval artwork, and I was particularly drawn to his use of shape, colour, and pattern. With this in mind I adapted a reference image of my chosen landscape using these features. I really tried to enhance the colours of the moors and used more oranges, browns and pinks to represent the heather on the hills, I also used pattern strategically, using angular lines on the cliff face, and the looser lines for the clouds and vegetation. The end result was a combination of watercolour and oil pastel, and I feel much more confident with this concept art than my previous attempt.

For the Friday week of this class, we had a character design workshop in which we learnt about important elements such as shape language. I was quite happy with the design of my protagonist, and so really used this class to flush out some of my secondary characters. One task I really enjoyed was picking a shape at random and creating a character around it. I chose a square and based the character of the king around it. The king is a character I hadn't given much thought to design-wise and this exercise really allowed me to experiment. I am really happy with the design I came up with as i feel like it is distinct and fits with the story, and i do not know if i would have created such a design without this workshop.

I also worked more on the dragon character, experimenting with texture using the side of my pencil to create scales and also creating a technique where i would load the end of a palette knife with ink before smudging it on the paper to create a scale shape. In terms of references for my character I unfortunately did not have access to any real0life dragons to base his actions and poses on, and instead sought out the next best thing, my dog Bernie. He shares a lot of physical traits with my first draft of the dragon, such as a long body, short legs an a long snout. I completed some observational drawings and really tried to study his physicality and how he shows emotion through his body so that I can I achieve similar results within my animation, and make the dragon appear fully realised.

I also completed some more full body sketches of Gwaine, as well as experimenting with his face shape to see how that affected his character. I also drew Gwaine's face with each of the different mouth shapes, so I would have better understanding of this when I start working on the lip-sync.

0 notes

Text

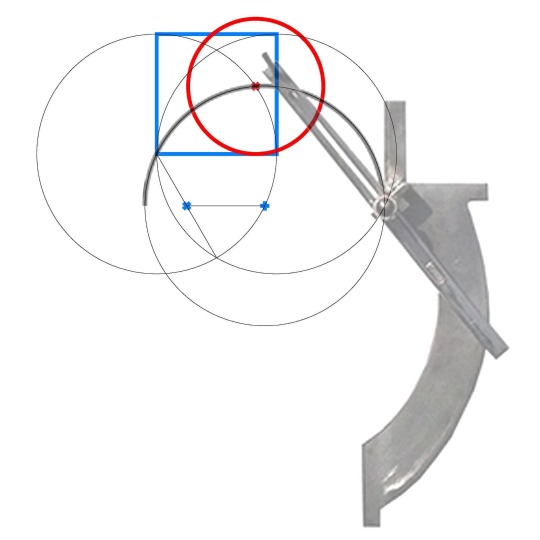

“The Compass and the Bailey”

A Mini Novella

In the quiet hours before dawn, London’s streets seemed an odd combination of both familiar and eternal. The dome of the Old Bailey—Lady Justice perched atop—watched over the city as it had done for over a century. You stood across the street, taking in the grand structure that had woven itself into your family’s legacy. This courthouse, with its monumental dome and the symbolic scales of justice, was more than just a historical landmark—it was your personal anchor to a heritage steeped in both architecture and the search for truth. You traced its roots not just through its physical form but through your family’s bloodline, the Baileys and Pigott’s of the past.

Your grandmother, a Bailey, had lived a life far removed from the steel and stone of London, her heart entwined in the balmy shores of the Bahamas, where her missionary father had taken their family. But it was here, in the streets of London, that her path would intertwine with your grandfather, Richard, an architect with an eye for precision. Richard, apprenticed under his uncle, E.W. Mountford, had helped shape the very building that now stood before you—the Central Criminal Court, the Old Bailey itself. The irony of their union was not lost on you, a Bailey married to the architect of the Bailey. The ancestral threads of architecture, justice, and heritage tied tightly together in a knot of fates.

But even this iconic building, with all its history, spoke only in half-measures. The concept of a “bailey,” that fortified outer wall of a medieval castle, was a structure designed to protect something far more fragile inside—the keep. A simple idea that shaped your family’s life philosophy: protection, safety, endurance.

Yet, with every generation, the question of how to protect became more complex. Your mother’s illness, during which you devoured the works of James Joyce, echoed this uncertainty. Finnegans Wake and Ulysses were not just intricate tales—they were Ireland, they were complexity, and they were a mirror to the world of architecture. The question that had haunted you in those hours beside her bed was the same one you faced in your work as an architect: How could something be constructed, whether through words or brick and mortar, that simultaneously protects and sets free?

In Joyce’s absence of punctuation in Ulysses, you found your answer—or at least a question that illuminated another path. What if, just as Joyce deconstructed language, you could deconstruct architecture’s reliance on the centere on the singularity that always returns to a fixed point? It was an Irish quandary, as much architectural as it was philosophical. Could geometry hold the answers?

You had always been fascinated by the Vesica Piscis, the shape formed when two circles intersect—a balance of opposites, the perfect representation of your family’s life. The two halves of Ireland. The union of heritage and modernity. North and South. Tradition and innovation. In the compass of your family, one circle was always grounded in the past, while the other stretched endlessly forward, and at the intersection, there was a third space—a new understanding.

That was when you began your own exploration, creating a new kind of compass, one that abandoned the need for a centre point. What was the point, after all, of always returning to a fixed centre? The very earth beneath Ireland was fractured—north from south, past from future. The Vesica Piscis, with its duality and its tension, represented a middle ground. This was the world of architecture you sought to enter, one where the conventional rules no longer applied.

Your compass, unlike any that had come before it, eschewed the need for a centre. It operated in balance and contradiction, in reflection and rotation, much like the architecture of your forefathers. When you created this new method—a way to turn a square into a circle through geometric projections—you were continuing their legacy. The impossibility of it, the mathematical precision with which you challenged traditional quadrature, became your rebellion and your inheritance.

My grandmother , herself part of this grand equation, seemed to embody the harmony of art and architecture. She, too, understood that there was music in the mortar, that design was not just function but a form of expression. Yet she, like your ancestors, lived the role of the architect’s wife—a balancing act between art and life, between creation and the pursuit of security.

What would your children inherit? This was the question that followed you through sleepless nights, that haunted your projects. Could they, like you, protect the legacy while also being free to reinvent it? Could the grandchild of architects and artists continue this balance?

At the core of it all, though, was the compass—the tool that tied you to the long history of architectural tradition. But this compass, much like Joyce’s writing, refused to follow a prescribed path. It was radical, just as Ireland’s division was radical, and yet, in its rebellion, it sought to find unity.

Much like the bailey of old, your family’s legacy would protect something fragile: not just a keep, but an idea. The notion that architecture, at its most profound, is more than just structures of stone. It is protection and projection. It is the balance between history and innovation. And, like the impossible quest of quadrature, it is a challenge that remains tantalizingly out of reach, but always worth pursuing.

As the first rays of dawn filtered through the streets, you took one last look at the Old Bailey. Its walls were still strong, still standing, but your compass—your own bailey—pointed to something beyond, to the vast horizon of possibility.

And so, you continued your work, for your family, for your heritage, and for the future.

#ArchitectureLegacy

#OldBailey

#IrishHeritage

#VesicaPiscis

#FamilyHistory

#ArchitectsOfLondon

#JamesJoyceInfluence

#CompassesAndCircles

#Quadrature

#ArchitecturalInnovation

#ArtAndArchitecture

#LegacyOfDesign

#PhilosophyOfArchitecture

#ArchitectsJourney

#GeometricArt

#TraditionAndModernity

0 notes

Link

0 notes

Text

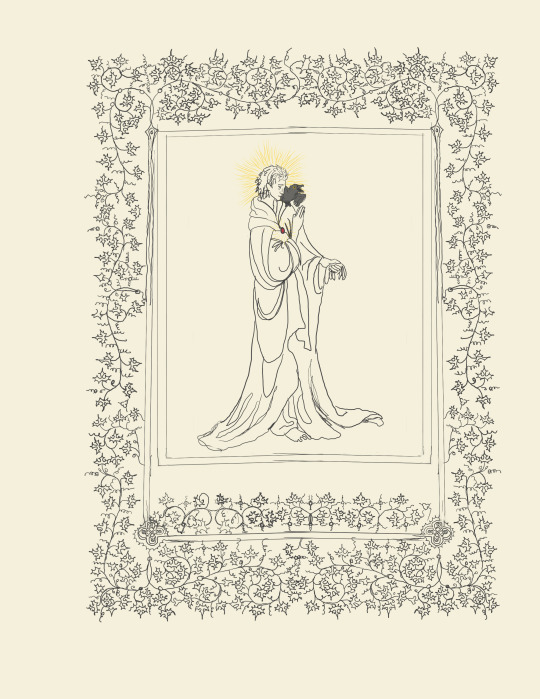

Xenia's Journey started out as traditional art in large format. This page is on the stage between blueprint and colouring - the method is based on Medieval methods where the illumination got a layer of pre-inking before colour was added. After counting man-hours for this method I said "Eff this! I'd better get a Wacom!" The day I work seriously on this project it'll be fully digital.

The details serve a purpose in enhancing the story - in this case they show the game Xenia and Sunniva are poaching on their way from Askedal. It's yet another design for an old way of reading web comics; you went to the comic's web page, hoping it was updated, and read the old episode once again. With a lot of details that would be a more fun experience for the reader.

Black fineliner on aquarelle paper.

Since Xenia's Journey is a 24h comic that grew you can read the raw first draft here.

#xenia's journey#comic#page design#traditional art#web comics#web comics history#reposters get cursed

0 notes

Text

Book 454

Medieval Illuminators and Their Methods of Work

Jonathan J.G. Alexander

Yale University Press 1992

With hundreds of illustrations, some in full color, this beautiful survey examines the work of European medieval illuminators spanning from the 4th to the 16th centuries. Of particular note, author Jonathan Alexander not only discusses the historical contexts of the artists’ lives but looks closely at their source materials, their methods, and the ways in which they influenced each other. With fascinating chapters on the technical aspects of illumination and the instructions they were given, this is a valuable and rewarding resource about the beautiful work of these medieval master craftsmen.

#bookshelf#illustrated book#library#personal library#personal collection#books#book lover#bibliophile#booklr#medieval illuminators and their methods of work#Jonathan J.G. Alexander#Yale university press#medieval art#history

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The inking layer for my very, very cheap and cheating version of the illuminated page from “the unknown and static strange” by @qqueenofhades . I am just tracing a page from jastor by the Limbourgs brothers for the border. After a few hours of that, I can say with the confidence of an autistic that whichever of them did the borders was autistic /as balls/. All the “leaves” are looped patterns, my dude was (beautifully!) stimming on paper and getting paid for it. Link - https://archiveofourown.org/works/45673276/chapters/114935725

it is /amazing/. Go read if you like ““I’m going to write my fav doing my job” in the best way possible. Deeply academic ( and amnesiac?) Hob hunts down missing-and-presumed-dead Dream though magically appearing medieval artworks?! It’s so rich and vibrant, many, many heart emojis worthy.

Not super in love with using the whole Christian halo on an immortal Greek god/immortal/etc being. I’ll isolate that on its own layer. But how else do I get “glowing magic” across in a vaguely historic way? Please mention methods.

60 notes

·

View notes

Text

Educating the princesses

“All of these princesses, both foreign and French, had received a first-rate education. Some were raised at the French court from childhood, such as Philip IV’s wife Joan of Navarre and Charles VIII’s young fiancée Margaret of Austria. Others were educated within their own families in their respective principalities.

Educators had long debated what women should be taught. In 1265, Philip of Novara had advised against teaching girls—except for nuns— how to read and write. He was, however, in the minority. Far from being neglected when it came to aristocratic education, women were the recipients of veritable miroirs aux princesses (didactic works presenting the exemplary image of the good ruler or, for women, the ideal princess), which reveal all the care that went into their training—as religious as it was moral and intellectual.

(...)

Beyond these theoretical treatises, sources on the practice of that time provide information about the educational methods of the period. Young princesses learned to read and often write. Such instruction often took place within the palace under a tutor. At the court of Savoy in the mid-fifteenth century, Pierre Aronchel was the schoolmaster of Louis and Anne of Cypress’s eldest daughters Margaret and Charlotte (future wife of Louis XI).

Like their brothers, young princesses first learned reading and religion. They learned to read using an alphabet book (Margaret of Austria learned the alphabet using a book handsomely bound in black velvet) and continued with psalters and books of hours. At the age of seven, young Joan of France, who was married to the Count of Montfort, received a richly illuminated book of hours of Notre-Dame from her mother Isabeau of Bavaria. During the fourteenth century, young girls at the court of Savoy practiced reading using liturgical collections, matins and penitential psalms, which were replaced by books of hours in the fifteenth century. Like their brothers, Savoyard princesses also learned to write.

Latin, however, was reserved for boys, which was one of the primary differences when it came to education. Princesses only knew the necessary prayers and formulas for following mass and reading their books of hours. There were a few exceptions nonetheless. Saint Louis’s sister Isabella of France (d. 1270), for example, was reputedly an excellent Latinist.

Failing Latin, aristocratic ladies knew other languages. John II’s future wife Bonne of Luxembourg, who had been raised in Bohemia, spoke Czech, German and French. Yolanda of Bar —daughter of Robert, Duke of Bar, and wife of John I, King of Aragon—could read ‘Limousin’ and Latin in addition to being able to write in French and Catalan. Others had a harder time learning a foreign language. During her entry ceremony in Paris in 1389, Isabeau of Bavaria was criticized for her poor understanding of French—four years after she had arrived in the kingdom.”

Queenship in medieval france 1300-1500, Murielle Gaude-Ferragu

#history#women in history#women's history#queens#middle ages#medieval women#france#french history#medieval history#isabeau of bavaria#Joan of navarre

108 notes

·

View notes

Text

Birds and the Birth of Commercial Color Printing

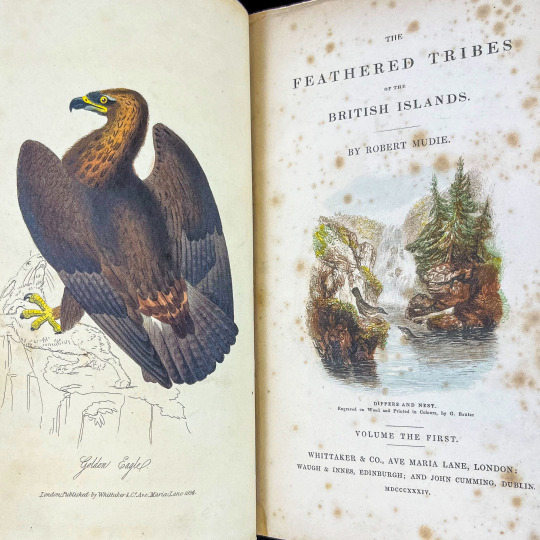

In celebration of Bird Day, we are featuring a set of ornithological volumes written by the self-taught Scottish polymath Robert Mudie (1777-1842). The Feathered Tribes of the British Islands (1834) served as a handbook for the average literate British bird enthusiast of the early nineteenth century. But what really makes the first edition of this work remarkable is it contains a landmark in Western book history: a specimen of the first color-printed illustration made using a commercially viable process.

To appreciate the gravity of this achievement, it may help to take a step further back in history. Johannes Gutenberg’s famous printing press of the mid-fifteenth century may have revolutionized the production and spread of textual knowledge, but it came with a cost. The printing technology of the time simply could not replicate the masterful paintings that illustrated medieval manuscripts. At best, a skilled printer could print in two colors by running the same sheet through the press twice: once for black ink and once for red. Even then, getting different colored elements to register (that is, to be properly aligned on the page) was challenging. If the early modern bibliophile wanted to add some color, they would have to commission artists to embellish their texts, which was quite an expensive undertaking. If we may use a modern metaphor, imagine paying your dream team of comic book pencillers and inkers to custom-illustrate the margins of your unillustrated copy of Lord of the Rings. For some breathtaking examples of illuminated incunabula (early printed books with medieval illustration), check out this blog from Trinity College Library, Cambridge: https://trinitycollegelibrarycambridge.wordpress.com/2017/10/25/italian-illuminated-incunabula/.

Unsurprisingly, color gradually drained from Western books in favor of sleek black and white copper-plate engravings that used cross-hatching to add dimension to illustrations. Hand-colored images remained a luxury. Yet some still held out hope that color illustration could be reproduced via the printing process. Enter English printer and artist George Baxter (1804-1867).

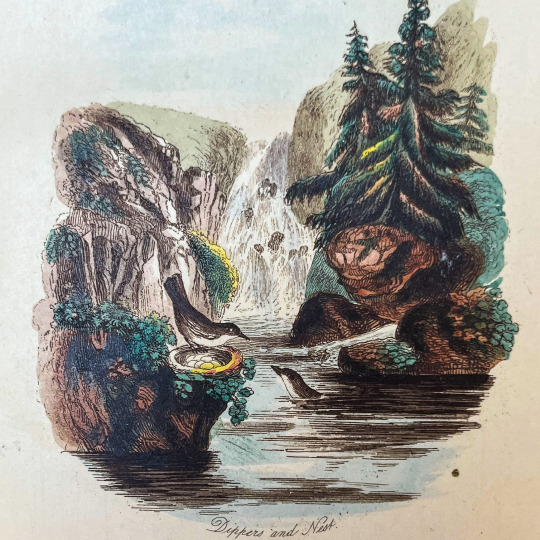

Beginning the late 1820s, Baxter experimented with color printing methods. By the time he collaborated with Robert Mudie in the early 1830s, he had developed a system in which he used a steel key plate inked in black to make a monochrome print and then added each color separately using a series of wood and metal (copper and zinc) blocks. Baxter’s process allowed him to apply up to 20 different colors, each requiring a different block, and ever the perfectionist, he would not print more than two colors per day in order to allow drying time between impressions and thereby produce a cleaner image. Among the first subjects Baxter published using his color printing technology is a vignette featuring a pair of dippers and nest that appears on the title-page of Feathered Tribes volume 1. For comparison with traditional color illustration, we’ve included a copy of the same vignette that was hand-colored in the third edition.

Dippers and nest vignette from the first edition of Robert Mudie’s Feathered Tribes, vol. 1 (printed in color by George Baxter).

Dippers and nest vignette from the third edition of Robert Mudie’s Feathered Tribes, vol. 1 (hand-colored).

Coloring in book illustration can have a profound impact on how people experience an illustrated text. It influences the reader’s imagining of events in a narrative text. For books of a more scientific nature, like the featured ornithological handbook, coloring can affect learning about the natural world. After all, so many birds are distinctive because of their uniquely colored plumage, and Robert Mudie created Feathered Tribes so that British inhabitants could identify and better enjoy their avian compatriots:

“... if [Feathered Tribes] shall continue, as I am told it has hitherto done, to send its readers to the haunts of birds to observe and study them there, I shall have accomplished a task which is to me far more delightful than if I had won the greenest laurels which are to be obtained in the field of literature and science.” (From Robert Mudie’s “Note to the Second Edition” of The Feathered Tribes of the British Islands.)

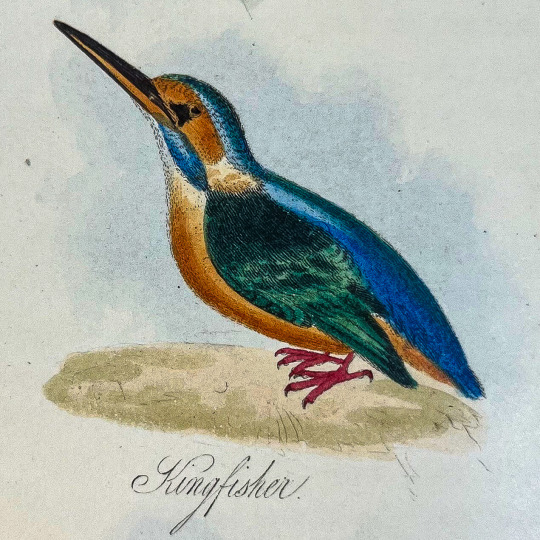

To conclude, what follows is an assortment of hand-colored plates from Mudie’s work. Enjoy, and have a Happy Bird Day!

Cross Bill

Curlew

Goatsucker

Great eared owl

Kingfisher

Kitty Wake

Mule Pheasant

Quail

Teal

Images from:

Mudie, Robert. The Feathered Tribes of the British Islands. London: Whittaker & Co., 1834. First edition. https://bit.ly/3MPmDDi

Mudie, Robert. The Feathered Tribes of the British Islands. London: Henry G. Bohn, 1841. Third edition. https://bit.ly/39tCyIR

124 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Arts and Crafts Art of the Book

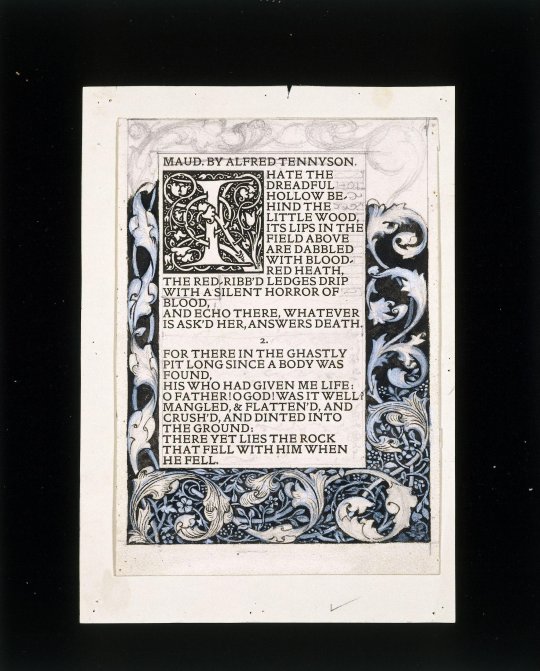

As the Nineteenth Century progressed, the legacy of the Industrial Revolution brought massive changes to the way goods were produced, and many people began to feel these changes were not all for the best. Mechanization allowed vast qualities of goods to be produced, but many felt it alienated workers and produced inferior goods. The Arts and Crafts Movement was one of many artistic and social reform movements of this time. Its adherents believed that happy workers made beautiful things, and making beautiful things made happy workers. They looked to the medieval workshop method of production, in which the craftsman-designer over saw the production of objects from start to finish, as the ideal model of production.

Given the Arts and Crafts Movement's focus on reviving medieval forms and methods of craftsmanship, the art of the book was a natural area of interest, with artists turning to the medieval tradition of illuminated manuscripts for their inspiration.

The most famous Arts and Crafts book artist and publisher, as with most things Arts and Crafts, is William Morris. William Morris was fascinated by medieval manuscripts, such as the ones he saw at Canterbury Cathedral as a young man and the Bodleian Library while a student at Oxford. Morris began experimenting with calligraphy in the 1870s, teaching himself a number of scripts, and learning about the technical aspects of manuscripts, such as margin size and letter spacing. These experiments gave Morris an in depth understanding of the scribal arts, allowing him to do more that simply copy existing styles and texts. During this time, Morris also began to develop a sense of decoration as it related to the text, and with his friend and fellow artist Edward Brune-Jones, produced several manuscripts.

The next step for Morris would be to move from manuscripts to printed books. Morris already had some experience in the printing business, having worked as the editor for the Oxford and Cambridge Magazine as a student in the 1850s. However, he did not begin to seriously think about starting a publishing company until the 1880s. One major problem for Morris was that, in keeping with the Arts and Crafts ideal of the fully integrated craftsman-designer, Morris wanted to design his own type. However, he lacked the specialized skills needed to cut the steel punches used for the first step in that process. This problem was solve in 1888 when Morris realized he could use a new projection and photoengraving technology to design the type at full size, which could then be shrunk down for specialized craftsmen to produce the punches. With this problem solved, Morris was able to set up the Kelmscott Press in 1891, publishing 66 titles in the five years before his death in 1896.

As with many other aspects of the Arts and Crafts Movement, William Morris' Kelmscott Press and its Art of the Book proved very popular in America, particularly the idea of the craftsman-designer producing a “whole book” intended to be a thing of beauty from cover to cover, instead of simply a cheap, mass produced object. Thus, a number of Arts and Crafts presses were founded in America, particularly in the Midwest, with Chicago acting as a major center for Arts and Crafts books. Notable presses included Clerks's Press in Fremont, Ohio, Cranbook Press in Detroit, and Village Press in Park Ridge Illinois. Notable publishers included Herbert Stone &Co., Stone and Kimball, and Way and Williams.

One of the best known examples of American Arts and Crafts books is Auvergne Press' The House Beautiful, which included photographic studies of dried weeds and highly stylized pen and ink designs of flower patterns drawn by Frank Lloyd Wright. The text itself was a reprint of a sermon by William C. Gannett, a famous Unitarian clergyman and social reformer. Gannett was also a friend of Frank Lloyd Wright's uncle and fellow Unitarian minster, Jenkin Lloyd Jones. Although the sermon itself is not particularly inspired, the chance to work in a new medium, and the message itself seemed to have appealed to Wright.

Image 1: Leaf from an Antiphoner from the Franciscan Convent of St. Klara, Cologne, ca. 1350, manuscript cutting. Photo Credit: The V&A Museum.Book makers of the Arts and Crafts Movement were inspired by the medieval manuscripts such as this one. They saw these manuscripts as beautiful works of art made by craftsman-designers who combined technical and design skills to create entire works of art, which were far superior to mass produced books. An antiphoner contains the choral parts sung during Mass by a monastic or other religious community. They were typically written in a large format so the whole choir could read them at the same time.

Image 2: William Morris, Maud, 1893, drawing. Photo Credit: The V&A Museum.William Morris was one of the leading artist and designers of the Arts and Crafts Movement. In 1891 he set up Kelmscott Press. As with other ventures, Morris designed and produced the books as a whole work of art, designing typefaces, page layouts, illustrations, bindings, and covers for each work as a whole.

Image 3: William C Gannet and Frank Lloyd Wright, The House Beautiful, Auvergne Press, 1896-1898. Photo Credit:Princeton University.Frank Lloyd Wright produced a series of photographs and ink drawing designs for Auvergne Press's The House Beautiful, a reprinting of a sermon by Unitarian minister William C. Gannet.

Image 4: Frank Lloyd Wright, Collotype of Weeds for The House Beautiful, Auvergne Press, 1896-1898. Photo Credit: Princeton University.Frank Lloyd Wright produced these collotypes of roadside weeds for Auvergne Press's The House Beautiful. Collotype is an early form of photographic printing, in which plates covered with a light sensitive gelatin is exposed to photographic transparencies.

#art history#Arts and Crafts#arts and crafts movement#william morris#frank lloyd wright#book#bookbinding#book art

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sewtube/Costube AU #4

A little ways into Kara's friendship with Lena, after she's been assimilated into the costube group chat, Kara sets out to build an historically-accurate-as-possible middle ages gown. She chooses rich, plush fabrics in vibrant, silky colors. Colors she would never normally wear.

She shows as much of her process as possible, collabing with medieval scholars and fashion historians to get their direct input, basically learn as much as she can about the style. She also takes time to elaborate on various misconceptions the public has on the middle ages, and gets experts to weigh in with the truth.

It's the most complicated project Kara has undertaken, a multi-part series that is heavily researched and most meticulously crafted. It's embellished and garnished to stunning effect, and even on the mannequin it's clear that it's just plain beautiful.

Just before the reveal, Kara has a segment talking to the camera.

"Well, it's almost finished. But, as some of you may have noticed, this color--and honestly the sizing of this monstrosity-- is way off for me to wear it. So, it's time to reveal the surprise: I didn't make this for me."

Kara grins, and the camera cuts to slow pan of Lena wearing the gown, fitted perfectly to her frame and her form flattered by long flowing lines. Lena's even done her long hair special, emulating the styles depicted in extant illustrations. The lighting is soft, almost holy as it illuminates regal features as intimately as it does the garment.

Lena is, simply, breathtaking.

She looks like a lady of olden days, a woman out of time. She gazes at the camera as though she were a queen, sharp eyed yet gentle. And if the camera lingers a little longer than it normally would for Kara, well... could you blame it?

After the reveal, the video cuts back to Kara, only this time Lena has joined her, still in her gown. Kara shares how big an endeavor it was, how taxing it was to plan so heavily when she's usually far more whimsical and sporadic with her projects. But overall she's pleased with the result.

As is Lena, who shares how comfortable it is and how she's noticed and appreciates the small details that Kara has stitched by hand. Lena's not an expert in medieval fashion like she is in her niche of edwardian fashion, but from what she's remembered from some of her college courses, it's as accurate as she could expect.

Lena also shares how many people enjoyed working with Kara, and how many of their non-medieval friends are pleading that Kara do a project in their niche as well so that they can participate. Kara asked good insightful questions, and worked with such respect for the people and material that she may as well go into historical fashion herself.

To which Kara blushes and demures, embarrassed to be spoken so highly of, before sharing how honored she was that so many people were willing to give their time and expertise to her project.

At the very end, Kara's smile turns mischievous. She calls on her viewership to issue a challenge-- which vintage project (of Kara's style and method) should Lena take on herself?

Comment down below.

#supercorp#sewtube au#costube au#yes lena evokes strong morgana vibes#but like... with a better costume#btw i mean princess morgana not witch morgana

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Passion of Joan of Arc

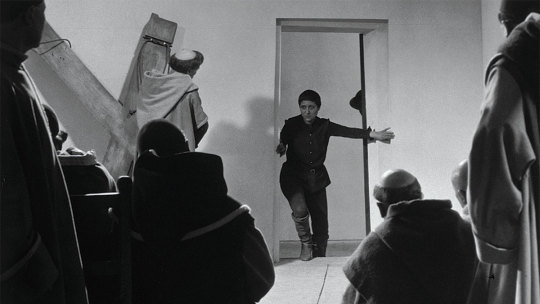

(1928, Denmark-France, silent, directed by Carl Dreyer)

Carl Dreyer's legendary picture about the martyr Joan of Arc has been cloaked in mystery from the day its production began. French nationalists were concerned that such a controversial project was being carried out on French soil by avant garde (read: non-Catholic) artists. Predictably, censors severely edited the film for its French premiere. Meanwhile, Dreyer's original version was destroyed in a fire. After the director composed an identical second print from remaining elements, a second fire destroyed that print. As the notes in the Criterion DVD version of the film point out, Dreyer's film endured the same fate as Joan herself: judges, scissors, and fire.

Over decades, badly altered and "musically enhanced" versions could be seen in theaters, and Dreyer is said to have been devastated by the sorry state of affairs. He died believing that his greatest work had been lost forever. However, in 1981, someone discovered in an office closet several canisters of film, one of which contained an original print . The office was located in a mental institution in Oslo, Norway.

For almost half a century, the only audiences enjoying an authentic version of this marvelous film were comprised of the mentally ill and their caretakers. Yet there's an uncanny consistency in that fact. Renee Falconetti, the actress who portrays Joan, is said to have never worked in motion pictures again because she was so emotionally spent by the experience (she did suffer some emotional breakdowns during and after production).

Another key player, Antonin Artaud, the Dada-Surrealist wild child, opium fiend, and Theatre of the Absurd founder, was eventually institutionalized (after a short and notorious career) because he was tormented by "voices." All of the bizarre circumstances of the film's history notwithstanding, Dreyer's work remains a landmark example of cinema as art.

Regarding its impact—primarily through a highly stylized conveyance of a real event—Jean Cocteau commented, "It seems like an historical document from an era in which the cinema didn't exist."

Dreyer's achievement is remarkable considering that he abandoned every common cinematic technique that might convey anything approaching reality. Art director Hermann Warm (The Cabinet of Doctor Caligari) found inspiration in the primitive art of illuminated manuscripts, in which perspective is entirely ignored. The result is an Expressionist take on medieval art (a successful convergence of Surrealism and medieval minimalism, one could argue) manifested in one of the most peculiar sets in film history. In this realm, physical structures, light, and angles do not observe geometry, and it is not possible to perceive their scale in relation to the actors.

The "geometry" and rhythm commonly associated with motion pictures are also absent from Dreyer's work. Spatial relationships between actors are seldom consistent, if they can be determined at all. There are no establishing shots as such, and cuts from one player to another do not always match dialogue or action. Most of the shots are close-ups of faces—but what amazing faces they are. Gifted veterans from the French stage are captured in carefully sustained, intricately detailed shots, and the result is unforgettable. Except for a few brief glimpses, almost none of the set is visible.

Dreyer's production notes indicate that he merely wished to employ a set that could immerse his actors in a milieu that might emotionally transport them to the historical setting. That speaks to Dreyer's confidence considering that he was working with gifted set designers at the peak of their talents. Notes also suggest that the disorienting visual style works at "unmooring from the present" the imaginations of viewers.

This method provides a stunning emotional immediacy appropriate to a historical subject. The resulting series of images is also beautiful (that's hardly surprising with cinematographer Rudolph Maté at the helm), and at some point it is uncertain if the film seems like a work of art because we are so disoriented, or if encountering such a deeply satisfying image disorients us. Add to this Renee Falconetti's performance, which utterly defies comparison, and you have a rare motion picture experience.

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Summer Series: The Spectacle of Nature: Illustrated Natural History Books

This summer in preparation for my final year as a UW-Milwaukee History Masters student I am undertaking an Individual Study overseen by head of UWM Special Collections, Max Yela. For years now I have been fascinated by the visual representation of nature in books, especially the proliferation of images produced during the 19th century when new printing methods such as lithography and wood engraving became popular. The Victorian period is also the time when natural history study became a suitable activity for women and children, and not just networks of wealthy “gentleman scientists.” My thesis will be about the popularization of natural history during the 19th century in Europe and the United States and how books containing illustrations of plants and animals contributed to that.

To get a better sense of the scope and history of scientific illustrations, I am spending this summer researching some of the earliest known natural history books. This is largely inspired by a week-long course I took with the California Rare Book School in the Summer of 2019 on “Illustrated Scientific Books in Early Modern Europe” taught by University of Southern California Art History and History Professor Daniela Bleichmar. That course provided a foundational knowledge about the role that images play in the production of scientific knowledge. Illustrations can also be religious, allegorical, emblematic, and political. This summer I will be researching the interplay between the history of science and the history of the book. Starting with medieval bestiaries and herbals in the manuscript tradition and working my way through some of the earliest printed scientific books of the 16th to 18th centuries. I am going to be utilizing materials within the UWM Special Collections, the American Geographical Society Library, and other local libraries to deepen my understanding of the role of images in natural history books.

Today I am highlighting illustrations from some well-known natural history books to get started!

List of Images:

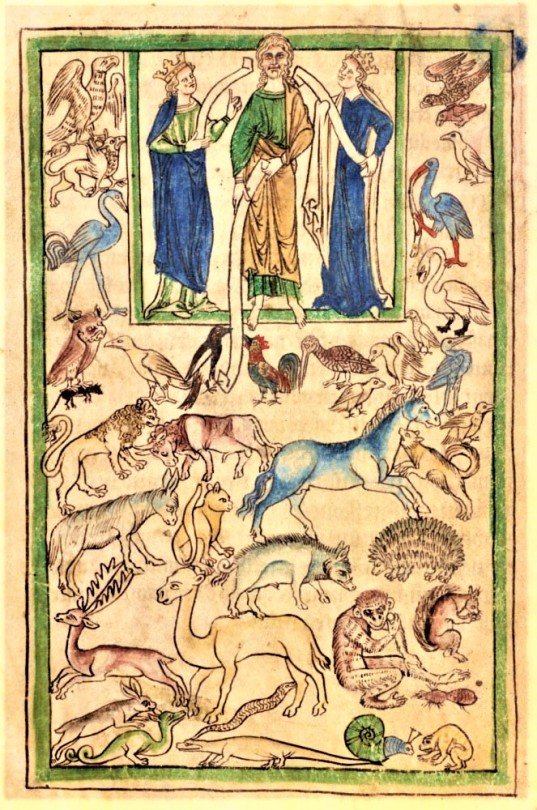

1. Bern Physiologus, 9th-century illuminated copy of the Latin translation of the Physiologus, a text that was originally written in Greek by an unknown author in Alexandria sometime between the 2nd -4th century CE. It is a didactic Christian text that describes the moral and symbolic meaning of various plants, animals, and mythical creatures and is thought to be the predecessor and inspiration to medieval bestiaries. Image courtesy of Wikipedia Commons.

2. Adam Naming the Animals from the Northumberland Bestiary, about 1250–60, English. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. 100, fol. 5v. Digital image courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program.

3. Reproduction of Albrecht Dürer’s Rhinoceros. This is a copperplate etching from our copy of Gaspar Schott’s Physica Curiosa, published in 1662. Dürer's Rhinoceros was originally a woodcut made in 1515 based on a written description and sketch of an Indian rhinoceros. It became an iconic image that was copied and included in many published books, including Conrad Gessner’s Historia animalium.

4. Hand-colored woodcut of a peacock from Conrad Gessner’s Historia animalium published 1551–1558. Image courtesy of U.S. National Library of Medicine’s online collection “Historical Anatomies on the Web.”

5. Daffodil (or Narcissus) flowers from our copy of the 1597 printing of John Gerard’s The Herball, or, Generall Historie of Plantes.

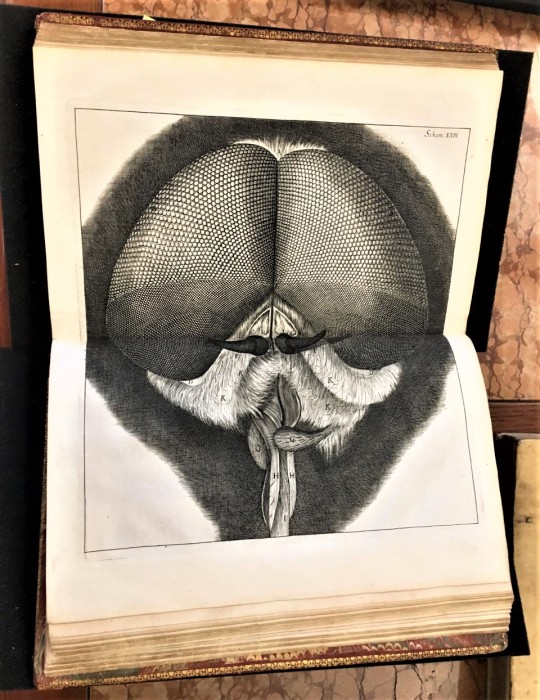

6. Head of fly from Robert Hooke’s book Micrographia: or Some Physiological Descriptions of Minute Bodies Made by Magnifying Glasses, with Observations and Inquiries Thereupon, published in 1665. This is a photograph I took of USC Special Collections copy.

7. Illustration from Maria Sibylla Merian’s Metamorphosis insectorum surinamensium, first published in 1705. Image from the Biodiversity Heritage Library’s digital copy.

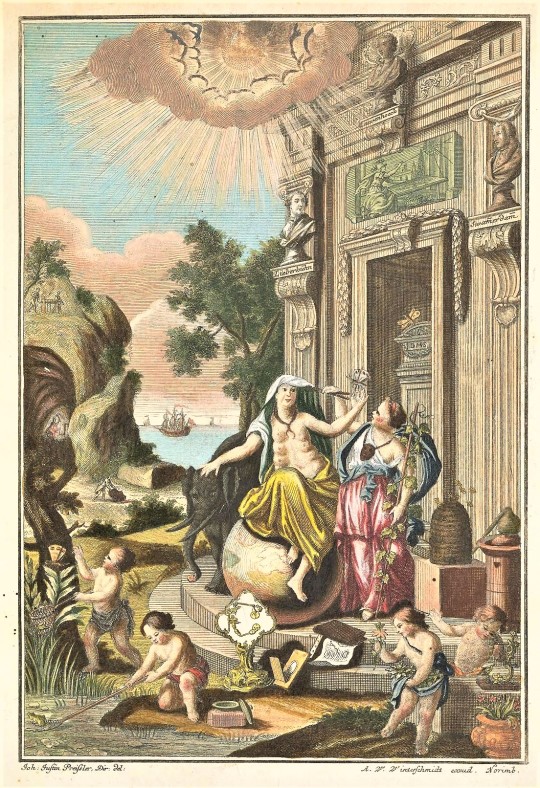

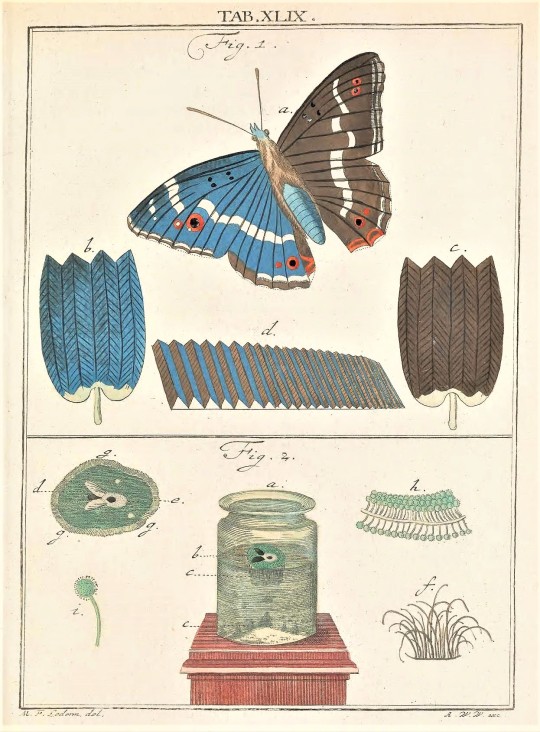

8.-9. Allegorical title page from Amusement microscopique tant pour l'esprit by Martin Frobenius Ledermüller, published 1764-1768. Illustration of a butterfly and what its wings look like under a microscope. Images from the Biodiversity Heritage Library’s digital copy.

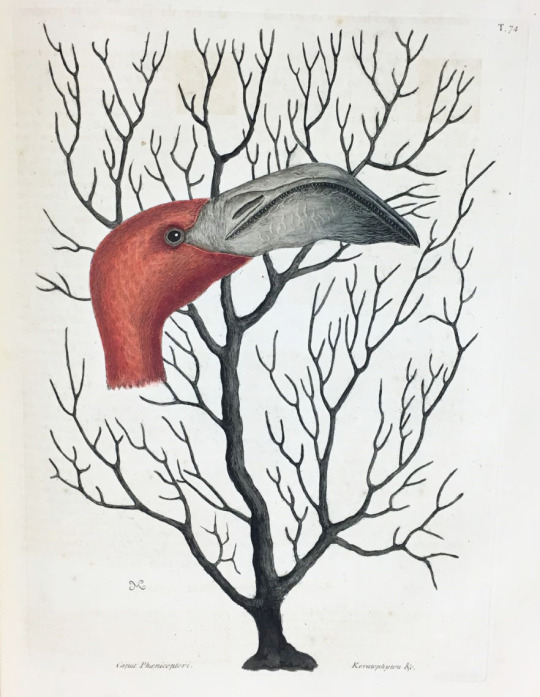

10. Flamingo from Mark Catesby’s Natural History of Carolina, Florida and the Bahama Islands. Catesby taught himself to make the engravings for the book, based on his original drawings from out in the field. He created 263 original watercolors as preparatory studies which he later turned into hand-colored etchings. The first volume was completed in 1732 and the second volume was completed in 1743. This is from Milwaukee Public Library’s copy.

I am naming my independent study “The Spectacle of Nature” as a homage to Noël Antoine Pluche’s Le Spectacle de la Nature, a popular work of natural history first published in French from 1732-1750.

–Sarah, Special Collections Senior Graduate Intern

#Summer Series#The Spectacle of Nature#Illustrated Natural History Books#Illustrated Scientific Books in Early Modern Europe#California Rare Book School#scientific illustrations#natural history#plants#animals#bestiaries#bestiary#herbal#Bern Physiologus#Physiologus#Albrecht Dürer#Gaspar Schott#Conrad Gessner#Robert Hooke#Maria Sibylla Merian#Mark Catesby#Sarah Finn#sarah

180 notes

·

View notes