#Bern Physiologus

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

this should be me

politely informing my boss that i can't do my job because i have to spend 18 hours perusing beafts on e-codices

#save me bern physiologus (cod. 318)#author of the physiologus truly the call-me-ishmael of his time. ''fun fact all lion babies are born dead and resurrected :)))''

313 notes

·

View notes

Text

Recogiendo perlas, Bern Physiologus (manuscrito del siglo IX que describe el buceo para la recolección de perlas)

0 notes

Photo

Summer Series: The Spectacle of Nature: Illustrated Natural History Books

This summer in preparation for my final year as a UW-Milwaukee History Masters student I am undertaking an Individual Study overseen by head of UWM Special Collections, Max Yela. For years now I have been fascinated by the visual representation of nature in books, especially the proliferation of images produced during the 19th century when new printing methods such as lithography and wood engraving became popular. The Victorian period is also the time when natural history study became a suitable activity for women and children, and not just networks of wealthy “gentleman scientists.” My thesis will be about the popularization of natural history during the 19th century in Europe and the United States and how books containing illustrations of plants and animals contributed to that.

To get a better sense of the scope and history of scientific illustrations, I am spending this summer researching some of the earliest known natural history books. This is largely inspired by a week-long course I took with the California Rare Book School in the Summer of 2019 on “Illustrated Scientific Books in Early Modern Europe” taught by University of Southern California Art History and History Professor Daniela Bleichmar. That course provided a foundational knowledge about the role that images play in the production of scientific knowledge. Illustrations can also be religious, allegorical, emblematic, and political. This summer I will be researching the interplay between the history of science and the history of the book. Starting with medieval bestiaries and herbals in the manuscript tradition and working my way through some of the earliest printed scientific books of the 16th to 18th centuries. I am going to be utilizing materials within the UWM Special Collections, the American Geographical Society Library, and other local libraries to deepen my understanding of the role of images in natural history books.

Today I am highlighting illustrations from some well-known natural history books to get started!

List of Images:

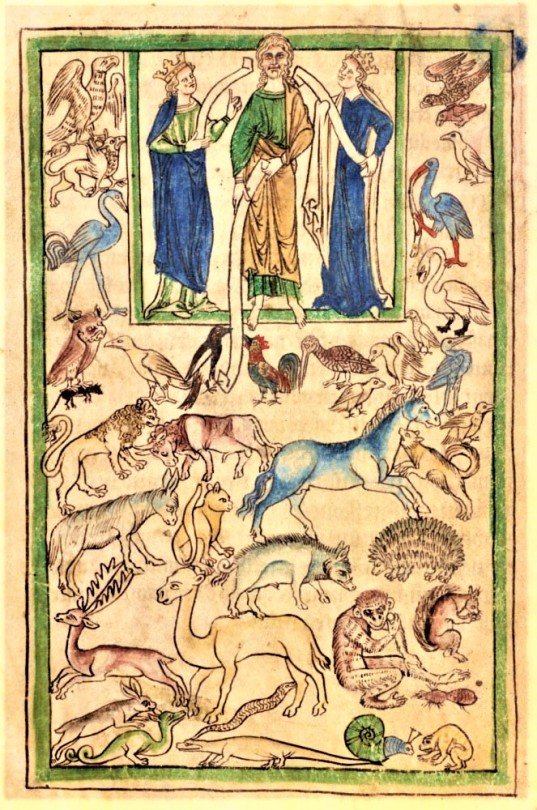

1. Bern Physiologus, 9th-century illuminated copy of the Latin translation of the Physiologus, a text that was originally written in Greek by an unknown author in Alexandria sometime between the 2nd -4th century CE. It is a didactic Christian text that describes the moral and symbolic meaning of various plants, animals, and mythical creatures and is thought to be the predecessor and inspiration to medieval bestiaries. Image courtesy of Wikipedia Commons.

2. Adam Naming the Animals from the Northumberland Bestiary, about 1250–60, English. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. 100, fol. 5v. Digital image courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program.

3. Reproduction of Albrecht Dürer’s Rhinoceros. This is a copperplate etching from our copy of Gaspar Schott’s Physica Curiosa, published in 1662. Dürer's Rhinoceros was originally a woodcut made in 1515 based on a written description and sketch of an Indian rhinoceros. It became an iconic image that was copied and included in many published books, including Conrad Gessner’s Historia animalium.

4. Hand-colored woodcut of a peacock from Conrad Gessner’s Historia animalium published 1551–1558. Image courtesy of U.S. National Library of Medicine’s online collection “Historical Anatomies on the Web.”

5. Daffodil (or Narcissus) flowers from our copy of the 1597 printing of John Gerard’s The Herball, or, Generall Historie of Plantes.

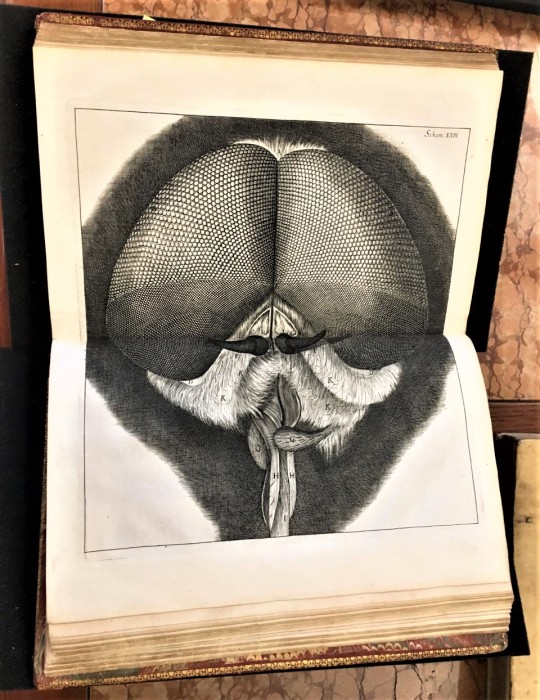

6. Head of fly from Robert Hooke’s book Micrographia: or Some Physiological Descriptions of Minute Bodies Made by Magnifying Glasses, with Observations and Inquiries Thereupon, published in 1665. This is a photograph I took of USC Special Collections copy.

7. Illustration from Maria Sibylla Merian’s Metamorphosis insectorum surinamensium, first published in 1705. Image from the Biodiversity Heritage Library’s digital copy.

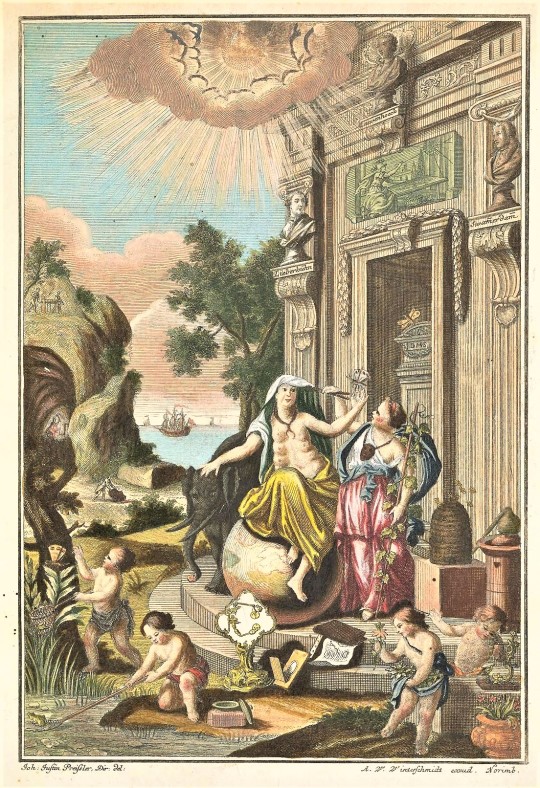

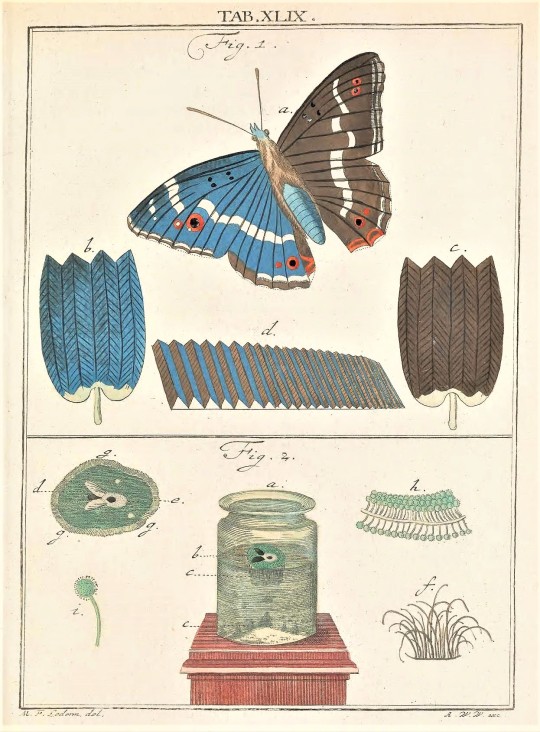

8.-9. Allegorical title page from Amusement microscopique tant pour l'esprit by Martin Frobenius Ledermüller, published 1764-1768. Illustration of a butterfly and what its wings look like under a microscope. Images from the Biodiversity Heritage Library’s digital copy.

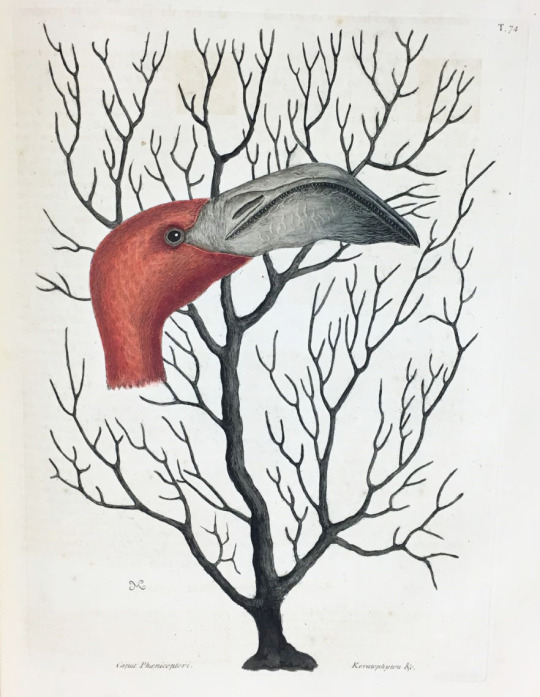

10. Flamingo from Mark Catesby’s Natural History of Carolina, Florida and the Bahama Islands. Catesby taught himself to make the engravings for the book, based on his original drawings from out in the field. He created 263 original watercolors as preparatory studies which he later turned into hand-colored etchings. The first volume was completed in 1732 and the second volume was completed in 1743. This is from Milwaukee Public Library’s copy.

I am naming my independent study “The Spectacle of Nature” as a homage to Noël Antoine Pluche’s Le Spectacle de la Nature, a popular work of natural history first published in French from 1732-1750.

–Sarah, Special Collections Senior Graduate Intern

#Summer Series#The Spectacle of Nature#Illustrated Natural History Books#Illustrated Scientific Books in Early Modern Europe#California Rare Book School#scientific illustrations#natural history#plants#animals#bestiaries#bestiary#herbal#Bern Physiologus#Physiologus#Albrecht Dürer#Gaspar Schott#Conrad Gessner#Robert Hooke#Maria Sibylla Merian#Mark Catesby#Sarah Finn#sarah

180 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Berner Physiologus, Cod. 318

Bern Burgerbibliothek

Pergament

Reims um 830

32 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Summer Series: The Spectacle of Nature

Physiologus

Earlier this month I outlined an Independent Study I am doing with the Head of Special Collections, Max Yela, where I am exploring the European tradition of plant and animal illustrations in books. I named the Summer Series “The Spectacle of Nature." As a refresher, I am investigating illustrated natural history books in the West, starting in the manuscript tradition through the advent of printing in the 15th century. From there I will track how illustrated natural history books have changed over the centuries. My goal is to form a foundation for my thesis research in the popularization of natural history books in the 19th century, when new printing technologies made books cheaper and more accessible to a wider consumer base.

Today I am highlighting the Physiologus, a collection of animal legends compiled by an anonymous author in Alexandria, Egypt around the 2nd century CE. The word “Physiologus” can be translated as “naturalist,” or more accurately, “allegorist,” someone who interprets the hidden meanings of the natural world. The Physiologus was originally written in Greek, with early translations appearing in Latin around the 4th century, and Ethiopian, Syrian, and Armenian around the 5th century. These translations increased the popularity of the stories, which were incorporated into Isidore of Seville’s encyclopedic work Etymologies (ca. 623). Illustrations and stories from Physiologus formed the primary basis of medieval bestiaries (book of beasts).

The Physiologus is a compilation of folklore from various traditions including Indian, Hebrew, and Egyptian legends, that were passed down through ancient scientific writers such as Pliny the Elder. These legends were then filtered through a Christian framework of the world. Natural things like plants, animals, and stones are shown as representing qualities of Christ. For example, the Physiologus describes the serpent growing old and losing its vision. To restore its eyesight, the serpent will fast for forty days and forty nights to shed its skin and renew itself.

My interest in the Physiologus is its visual representations of plants and animals, and how those depictions became iconographic over hundreds of years. The earliest surviving illustrated copy is the Bern Physiologus from around the 9th century CE. I’ve included illustrations of the lion and elephant from the digitized Bern Physiolgus from Europeana.

Many illustrations that first appear in copies of the Physiologus later appear in medieval bestiaries, and even early printed books.

One of my favorite examples is the pelican bird. From Michael J. Curley’s English translation:

“Physiologus says of the pelican that it is an exceeding lover of its young. If the pelican brings forth young and the little ones grow, they take to striking their parents in the face. The parents, however, hitting back kill their young ones and then, moved my compassion, they weep over them for three days, lamenting over those whom they killed. On the third day, their mother strikes her side and spills her own blood over their dead bodies (that is, of the chicks) and the blood itself awakens them from death.”

The illustration shows the mother pelican rejuvenating the chicks with her blood. I included three visual examples of this: A woodcut from UW-Madison's copy of Ortus sanitatis (Latin for The Garden of Health) from the 1490s, a woodcut from the 1587 G. Ponce de Leon edition of Physiologus from the Newberry Library in Chicago (scanned from Michal J. Curley’s book), and the 1953 Book Club of California edition of Physiologus illustrated by Mallette Dean, which we have featured in several Fine Press Friday posts. Francis J. Carmody‘s translation for the Book Club of California is a composite of Greek, Syrian, Ethiopian, and Latin.

I will explore other illustrated natural history books from the manuscript tradition in upcoming posts before moving on to early printed zoological and botanical books.

View more posts in the Summer Series: The Spectacle of Nature.

–Sarah, Special Collections Senior Graduate Intern

Scholarly works that I consulted while researching the Physiologus:

Curley, Michael J. Physiologus: A Medieval Book of Nature Lore. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009.

Kay, Sarah. Animal Skins and the Reading Self in Medieval Latin and French Bestiaries. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2017.

Morrison, Elizabeth, and Larisa Grollemond, eds. Book of Beasts: the Bestiary in the Medieval World. Los Angeles: Published by the J. Paul Getty Museum, 2019.

#The Spectacle of Nature#Summer Series#Physiologus#natural history#animals#legends#fables#allegory#tales#plants#nature#woodcuts#manuscripts#Bern Physiologus#Ortus sanitatis#The Garden of Health#Mallette Dean#Book Club of California#Isidore of Seville#Etymologies#Sarah Finn#sarah

107 notes

·

View notes