#Illustrated Scientific Books in Early Modern Europe

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

Reading Practice: The Pursuit of Natural Knowledge from Manuscript to Print

In her book "Reading Practice: The Pursuit of Natural Knowledge from Manuscript to Print," Melissa Reynolds follows a "paper trail" of historical figures in early modern Europe to gain insight into how they understood the natural world. Using books, manuscripts, and other textual artifacts, Reynolds investigates how intellectuals, scientists, and scholars of the time interacted with and made sense of their lives and landscapes.

The key purpose of Melissa Reynolds's first book, Reading Practice: The Pursuit of Natural Knowledge from Manuscript to Print, is to explore how readers interacted with texts and manuscripts related to natural knowledge and how the readers interpreted and applied the knowledge from these works to their daily lives. Reynolds does this helpfully and engagingly that features interdisciplinary connections. Reading Practice provides a detailed analysis of how reading and textual practices influenced the pursuit of natural knowledge during a transformative period in European history.

This book will be a delightful experience for any readers interested or researching bloodletting or the influence of thunder and celestial bodies on humanity and health. A cultural historian of early modern and medieval Europe, Melissa Reynolds has a wide range of interests in fields such as the history of science and medicine, gender studies, and historical texts. Specifically, she is keenly interested in studying the transmission of natural medical and scientific knowledge from noble cultures to the ordinary 'commonfolk' of the past, as well as the subsequent cultural shifts that resulted from this dissemination. She is currently Assistant Professor of Early Modern European History at Texas Christian University.

This book prominently features concepts related to astrology, feminine insights that were frowned upon yet sought after by common men, superstitions, religion, and prognostications. The author extensively analyzed a corpus of 182 manuscripts to inspire the book. These primary sources, which she discovered over a decade of research on multiple continents, build up her argument around "natural knowledge." Natural knowledge is defined as an understanding of the natural world based on observation, study, and experience, including aspects of medicine, science, and the environment.

During the early modern period, common English people created and shared practical knowledge from texts like almanacs, herbals, and medical recipes. This book explores how they used the skillfully crafted and sometimes artistic manuscripts to learn about health, nature, and their place in the universe.

Reynolds examines the transition from Latin manuscripts to Middle English folios, the emergence of printing, the development of critical thinking, and the origins of what would become copyright law. This book is valuable for historians, librarians, academics of early modern science and medicine, and others interested in the evolution of literacy and natural knowledge during this era. The text includes notes on transcriptions and manuscript titles, along with a comprehensive list of all figures and tables featured in the book.

To understand how people in the Middle Ages sought out and viewed information and the world around them, the author highlighted certain portions of the text with illustrations from the manuscripts in her corpus. Created during a time when the printing press was yet to be invented and religious beliefs were often a matter of life or death, the illustrations on the pages of parchment were symbolic in the sense that they were utilized by those who were unable to read or write.

Ancient visual calendars and pictorial tables detailing zodiac signs and how they correspond to human anatomy or visual prognostications of weather patterns are only some of the images within this book. Reynolds guides readers on a historical and scientific journey that harkens back to a simpler era, revealing the circulation and recirculation of ancient texts over time.

The author asserts that the common folk of England were well aware that the divine, who "granted virtues to be in words, in stones, and in herbs," backed up some powerful remedies created by the combination of actions and ingredients (82). This book is highly recommended as it is remarkably unique, especially at a time when the art of creating bold-lettered manuscripts has now been replaced by graphic design and word processing programs. Engaging with this book will enhance a reader's comprehension of exactly how knowledge was passed down throughout history and the significant impact of this transmission on intellectual and cultural development.

Continue reading...

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

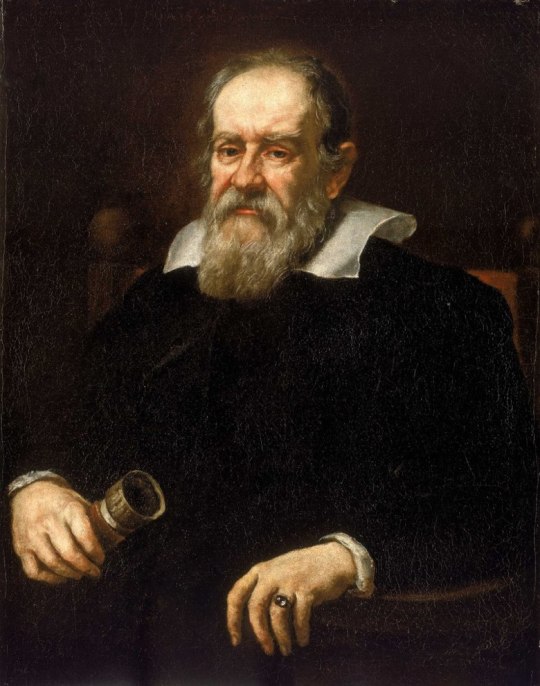

Galileo Galilei: The Father of Modern Astronomy

Few historical figures, such as Galileo Galilei, have profoundly shaped our understanding of the universe. Often called the "Father of Modern Astronomy," Galileo revolutionized how we view the cosmos with his pioneering telescope use, groundbreaking discoveries, and unshakable commitment to science.

The Renaissance Mind

Born in Pisa, Italy, in 1564, Galileo grew up during the Italian Renaissance—a period of extraordinary artistic, cultural, and scientific growth. Initially studying medicine, he quickly found his passion in mathematics and natural philosophy. This curiosity would lead him to challenge long-held beliefs and lay the groundwork for modern science.

Revolutionizing the Telescope

Although Galileo didn’t invent the telescope, he was the first to use it extensively for astronomical purposes. In 1609, he crafted an improved version capable of magnifying objects up to 30 times. What he saw through his lens astonished the world:

The Moon’s Surface: Instead of a smooth, perfect sphere, Galileo observed craters and mountains, proving that celestial bodies were not divine and unblemished.

Jupiter’s Moons: In 1610, he discovered four moons orbiting Jupiter (Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto), showing that not everything revolved around Earth.

Venus’s Phases: By observing Venus's changing phases, he provided evidence that it orbited the Sun, supporting the heliocentric model.

The Milky Way: Galileo revealed that the Milky Way was composed of countless stars, vastly expanding our understanding of the universe’s scale.

The Heliocentric Controversy

Galileo’s observations strongly supported the Copernican theory, which placed the Sun at the center of the solar system instead of Earth. This idea directly contradicted the geocentric view endorsed by the Catholic Church. In 1616, the Church declared the heliocentric theory heretical, but Galileo continued his research and writings.

1632, Galileo published Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems, a book comparing the geocentric and heliocentric models. Though cleverly written, it angered the Church, and Galileo was summoned to Rome to face the Inquisition.

Trial and Legacy

Galileo was found "vehemently suspect of heresy" and forced to recant his support for the heliocentric model. He spent the remaining years of his life under house arrest. Despite this, his work continued influencing generations of scientists, including Isaac Newton.

Galileo’s Contributions Beyond Astronomy

While his celestial discoveries are most celebrated, Galileo made significant contributions to physics:

The Law of Falling Bodies: He demonstrated that objects fall at the same rate regardless of their mass (famously illustrated by his experiment from the Leaning Tower of Pisa).

Inertia: Galileo’s work laid the foundation for Newton’s first law of motion.

The Pendulum: His studies on pendulums revolutionized timekeeping and led to the development of more accurate clocks.

Did You Know?

Galileo's early invention of a military compass was widely used for calculations in artillery and fortifications.

His later years were marked by blindness, yet he continued to work and correspond with scientists across Europe.

In 1992, the Catholic Church formally acknowledged that Galileo was correct about the heliocentric model—over 350 years after his trial.

A Legacy Written in the Stars

Galileo’s relentless pursuit of truth forever changed the course of science. He showed us that observation and experimentation—not tradition or authority—should guide our understanding of the natural world.

When you look at the night sky, remember Galileo. Through his telescope, he dared to question the status quo and revealed the universe in stunning detail, inspiring humanity to keep looking up and asking, “What’s out there?”

0 notes

Photo

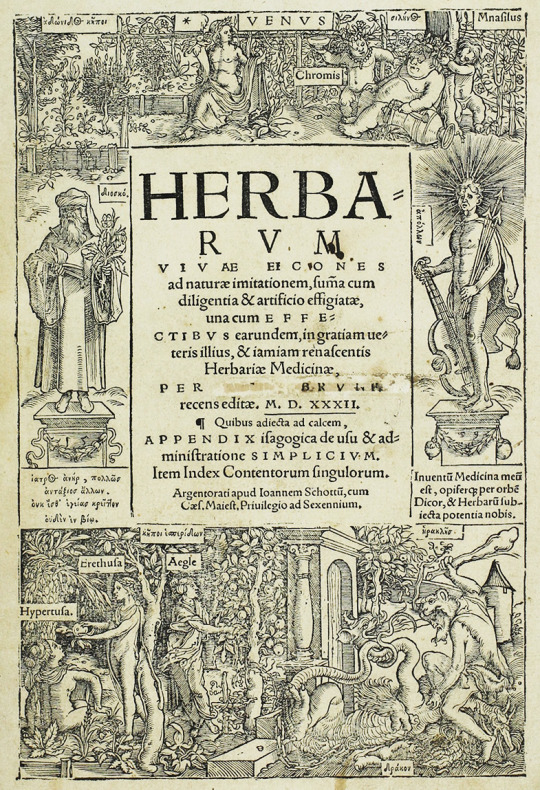

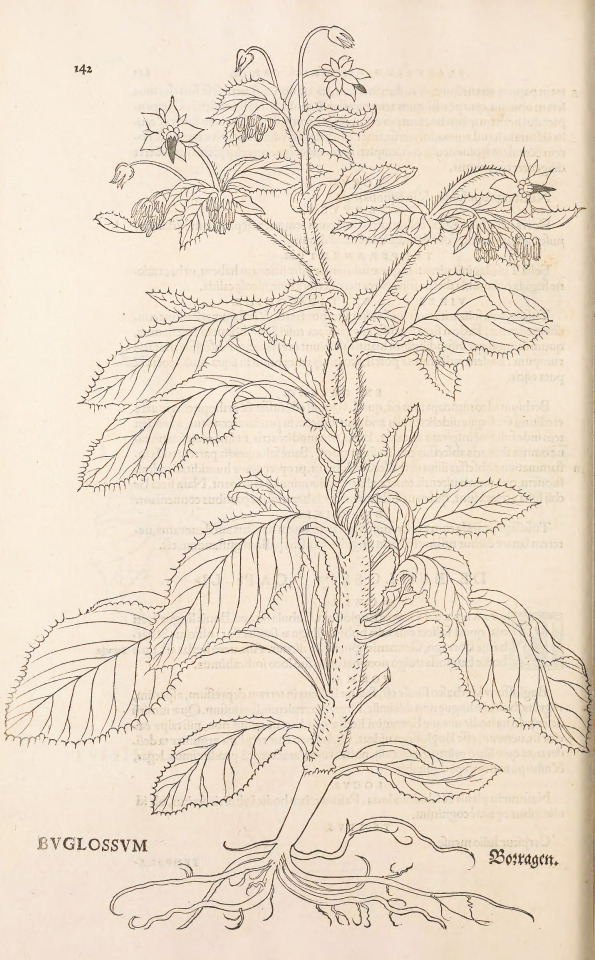

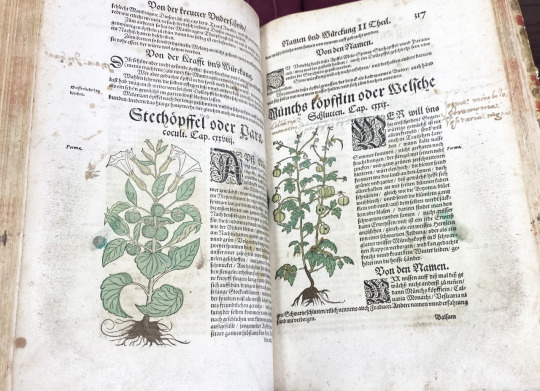

Summer Series: The Spectacle of Nature: Illustrated Natural History Books

This summer in preparation for my final year as a UW-Milwaukee History Masters student I am undertaking an Individual Study overseen by head of UWM Special Collections, Max Yela. For years now I have been fascinated by the visual representation of nature in books, especially the proliferation of images produced during the 19th century when new printing methods such as lithography and wood engraving became popular. The Victorian period is also the time when natural history study became a suitable activity for women and children, and not just networks of wealthy “gentleman scientists.” My thesis will be about the popularization of natural history during the 19th century in Europe and the United States and how books containing illustrations of plants and animals contributed to that.

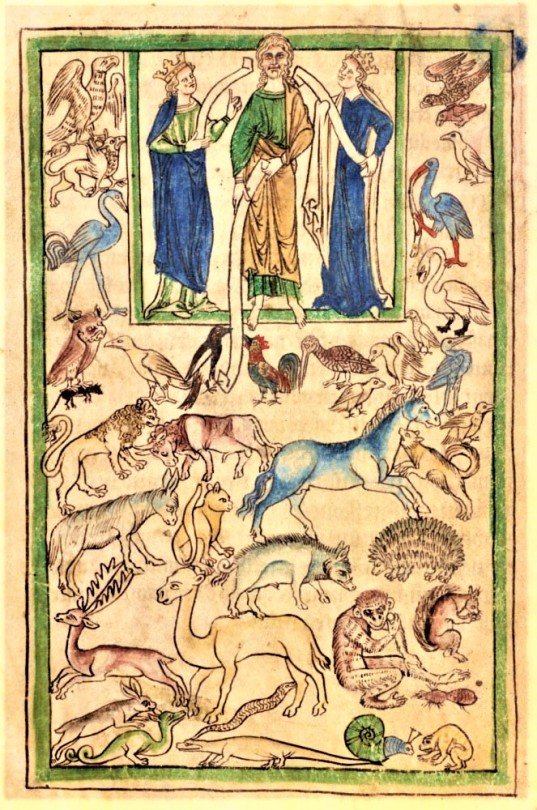

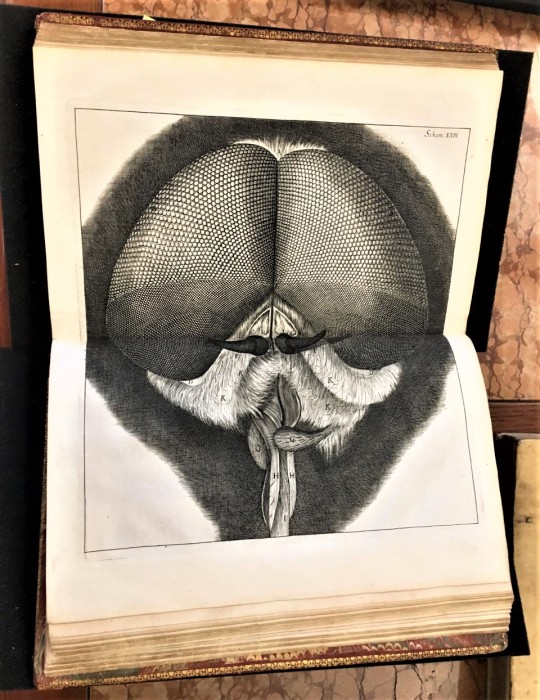

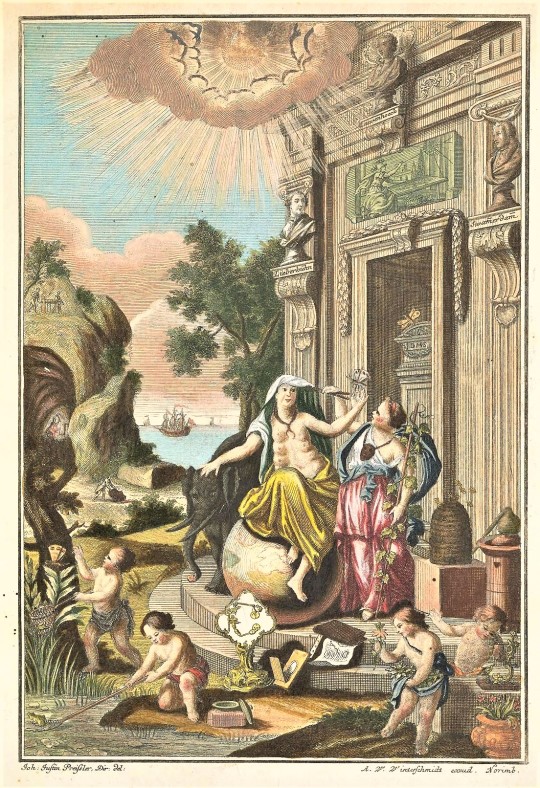

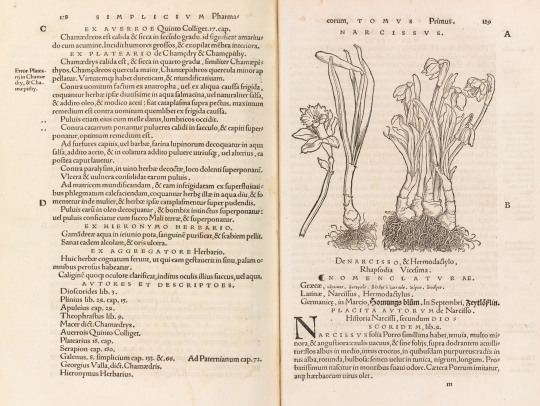

To get a better sense of the scope and history of scientific illustrations, I am spending this summer researching some of the earliest known natural history books. This is largely inspired by a week-long course I took with the California Rare Book School in the Summer of 2019 on “Illustrated Scientific Books in Early Modern Europe” taught by University of Southern California Art History and History Professor Daniela Bleichmar. That course provided a foundational knowledge about the role that images play in the production of scientific knowledge. Illustrations can also be religious, allegorical, emblematic, and political. This summer I will be researching the interplay between the history of science and the history of the book. Starting with medieval bestiaries and herbals in the manuscript tradition and working my way through some of the earliest printed scientific books of the 16th to 18th centuries. I am going to be utilizing materials within the UWM Special Collections, the American Geographical Society Library, and other local libraries to deepen my understanding of the role of images in natural history books.

Today I am highlighting illustrations from some well-known natural history books to get started!

List of Images:

1. Bern Physiologus, 9th-century illuminated copy of the Latin translation of the Physiologus, a text that was originally written in Greek by an unknown author in Alexandria sometime between the 2nd -4th century CE. It is a didactic Christian text that describes the moral and symbolic meaning of various plants, animals, and mythical creatures and is thought to be the predecessor and inspiration to medieval bestiaries. Image courtesy of Wikipedia Commons.

2. Adam Naming the Animals from the Northumberland Bestiary, about 1250–60, English. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. 100, fol. 5v. Digital image courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program.

3. Reproduction of Albrecht Dürer’s Rhinoceros. This is a copperplate etching from our copy of Gaspar Schott’s Physica Curiosa, published in 1662. Dürer's Rhinoceros was originally a woodcut made in 1515 based on a written description and sketch of an Indian rhinoceros. It became an iconic image that was copied and included in many published books, including Conrad Gessner’s Historia animalium.

4. Hand-colored woodcut of a peacock from Conrad Gessner’s Historia animalium published 1551–1558. Image courtesy of U.S. National Library of Medicine’s online collection “Historical Anatomies on the Web.”

5. Daffodil (or Narcissus) flowers from our copy of the 1597 printing of John Gerard’s The Herball, or, Generall Historie of Plantes.

6. Head of fly from Robert Hooke’s book Micrographia: or Some Physiological Descriptions of Minute Bodies Made by Magnifying Glasses, with Observations and Inquiries Thereupon, published in 1665. This is a photograph I took of USC Special Collections copy.

7. Illustration from Maria Sibylla Merian’s Metamorphosis insectorum surinamensium, first published in 1705. Image from the Biodiversity Heritage Library’s digital copy.

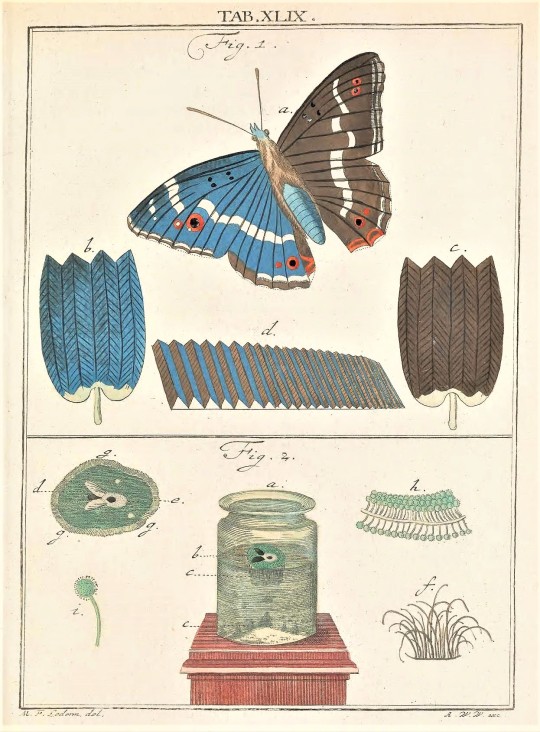

8.-9. Allegorical title page from Amusement microscopique tant pour l'esprit by Martin Frobenius Ledermüller, published 1764-1768. Illustration of a butterfly and what its wings look like under a microscope. Images from the Biodiversity Heritage Library’s digital copy.

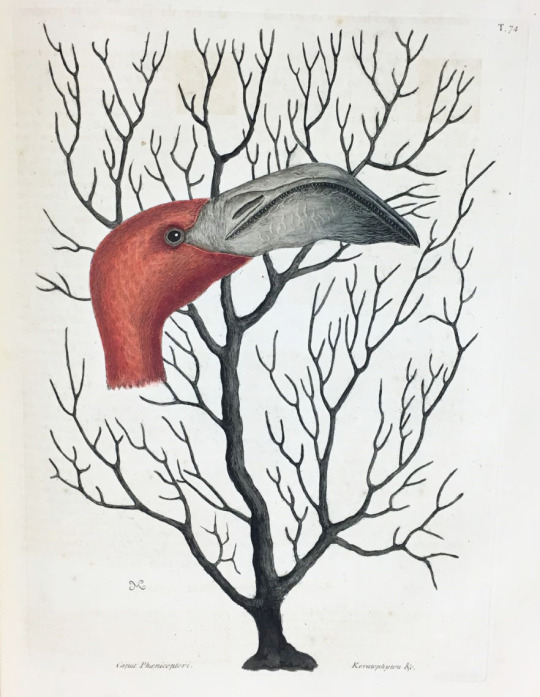

10. Flamingo from Mark Catesby’s Natural History of Carolina, Florida and the Bahama Islands. Catesby taught himself to make the engravings for the book, based on his original drawings from out in the field. He created 263 original watercolors as preparatory studies which he later turned into hand-colored etchings. The first volume was completed in 1732 and the second volume was completed in 1743. This is from Milwaukee Public Library’s copy.

I am naming my independent study “The Spectacle of Nature” as a homage to Noël Antoine Pluche’s Le Spectacle de la Nature, a popular work of natural history first published in French from 1732-1750.

–Sarah, Special Collections Senior Graduate Intern

#Summer Series#The Spectacle of Nature#Illustrated Natural History Books#Illustrated Scientific Books in Early Modern Europe#California Rare Book School#scientific illustrations#natural history#plants#animals#bestiaries#bestiary#herbal#Bern Physiologus#Physiologus#Albrecht Dürer#Gaspar Schott#Conrad Gessner#Robert Hooke#Maria Sibylla Merian#Mark Catesby#Sarah Finn#sarah

180 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Goddesses, Warrior Women, & Females at War

Reading Recommendations

Venus and Aphrodite: A Biography of Desire by Bettany Hughes

A cultural history of the goddess of love, from a New York Times bestselling and award-winning historian. Aphrodite was said to have been born from the sea, rising out of a froth of white foam. But long before the Ancient Greeks conceived of this voluptuous blonde, she existed as an early spirit of fertility on the shores of Cyprus -- and thousands of years before that, as a ferocious warrior-goddess in the Middle East. Proving that this fabled figure is so much more than an avatar of commercialized romance, historian Bettany Hughes reveals the remarkable lifestory of one of antiquity's most potent myths. Venus and Aphrodite brings together ancient art, mythology, and archaeological revelations to tell the story of human desire. From Mesopotamia to modern-day London, from Botticelli to Beyoncé, Hughes explains why this immortal goddess continues to entrance us today -- and how we trivialize her power at our peril.

The Amazons: Lives and Legends of Warrior Women Across the Ancient World by Adrienne Mayor

The real history of the Amazons in war and love Amazons--fierce warrior women dwelling on the fringes of the known world--were the mythic archenemies of the ancient Greeks. Heracles and Achilles displayed their valor in duels with Amazon queens, and the Athenians reveled in their victory over a powerful Amazon army. In historical times, Cyrus of Persia, Alexander the Great, and the Roman general Pompey tangled with Amazons. But just who were these bold barbarian archers on horseback who gloried in fighting, hunting, and sexual freedom? Were Amazons real? In this deeply researched, wide-ranging, and lavishly illustrated book, National Book Award finalist Adrienne Mayor presents the Amazons as they have never been seen before. This is the first comprehensive account of warrior women in myth and history across the ancient world, from the Mediterranean Sea to the Great Wall of China. Mayor tells how amazing new archaeological discoveries of battle-scarred female skeletons buried with their weapons prove that women warriors were not merely figments of the Greek imagination. Combining classical myth and art, nomad traditions, and scientific archaeology, she reveals intimate, surprising details and original insights about the lives and legends of the women known as Amazons. Provocatively arguing that a timeless search for a balance between the sexes explains the allure of the Amazons, Mayor reminds us that there were as many Amazon love stories as there were war stories. The Greeks were not the only people enchanted by Amazons--Mayor shows that warlike women of nomadic cultures inspired exciting tales in ancient Egypt, Persia, India, Central Asia, and China.

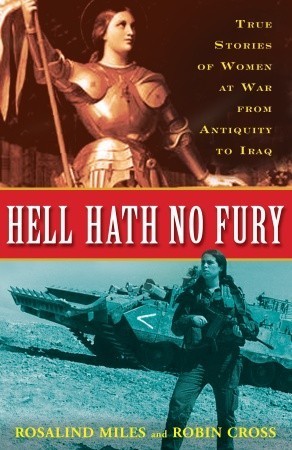

Hell Hath No Fury: True Stories of Women at War from Antiquity to Iraq by Rosalind Miles, Robin Cross

An engaging collection that uncovers injustices in history and overturns misconceptions about the role of women in war When you think of war, you think of men, right? Not so fast. In Hell Hath No Fury, Rosalind Miles and Robin Cross prove that although many of their stories have been erased or forgotten, women have played an integral role in wars throughout history. In witty and compelling biographical essays categorized and alphabetized for easy reference, Miles and Cross introduce us to war leaders (Cleopatra, Elizabeth I, Margaret Thatcher); combatants (Molly Pitcher, Lily Litvak, Tammy Duckworth); spies (Belle Boyd, Virginia Hall, Noor Inayat Khan); reporters and propagandists (Martha Gellhorn, Tokyo Rose, Anna Politkov- skaya); and more. These are women who have taken action and who challenge our perceived notions of womanhood. Some will be familiar to readers, but most will not, though their deeds during wartime were every bit as important as their male contemporaries’ more heralded contributions.

Goddesses: Mysteries of the Feminine Divine by Joseph Campbell, Safron Rossi (Editor)

The first Joseph Campbell work to focus on the Goddess, edited and introduced by Safron Rossi, PhD, Curator of Collections at Opus Archives and Research Center, home to the archival collections of Joseph Campbell, Marija Gimbutas, James Hillman, and other scholars of mythology, Jungian and archetypal psychology, and the humanities. Joseph Campbell brought mythology to a mass audience. His bestselling books, including The Power of Myth and The Hero with a Thousand Faces, are the rare blockbusters that are also scholarly classics. While Campbell’s work reached wide and deep as he covered the world’s great mythological traditions, he never wrote a book on goddesses in world mythology. He did, however, have much to say on the subject. Between 1972 and 1986 he gave over twenty lectures and workshops on goddesses, exploring the figures, functions, symbols, and themes of the feminine divine, following them through their transformations across cultures and epochs. In this provocative volume, editor Safron Rossi—a goddess studies scholar, professor of mythology, and curator of collections at Opus Archives, which holds the Joseph Campbell archival manuscript collection and personal library—collects these lectures for the first time. In them, Campbell traces the evolution of the feminine divine from one Great Goddess to many, from Neolithic Old Europe to the Renaissance. He sheds new light on classical motifs and reveals how the feminine divine symbolizes the archetypal energies of transformation, initiation, and inspiration.

#nonfiction#non-fiction#women in history#history or women#warrior women#booklr#booklist#reading recommendations#recommended reading#book recs#library#mythology#the amazons#aphrodite#venus#greek#roman

144 notes

·

View notes

Photo

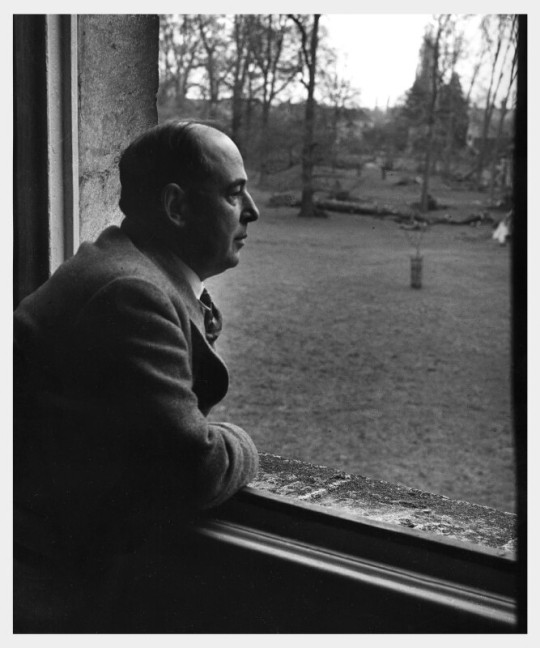

How will the legend of the age of trees Feel, when the last tree falls in England? When the concrete spreads and the town conquers The country’s heart; when contraceptive Tarmac’s laid where farm has faded, Tramline flows where slept a hamlet, And shop-fronts, blazing without a stop from Dover to Wrath, have glazed us over? Simplest tales will then bewilder The questioning children, “What was a chestnut? Say what it means to climb a Beanstalk, Tell me, grandfather, what an elm is. What was Autumn? They never taught us.” Then, told by teachers how once from mould Came growing creatures of lower nature Able to live and die, though neither Beast nor man, and around them wreathing Excellent clothing, breathing sunlight— Half understanding, their ill-acquainted Fancy will tint their wonder-paintings Trees as men walking, wood-romances Of goblins stalking in silky green, Of milk-sheen froth upon the lace of hawthorn’s Collar, pallor in the face of birchgirl. So shall a homeless time, though dimly Catch from afar (for soul is watchfull) A sight of tree-delighted Eden.

- C.S. Lewis, The Future of Forestry

In his poem “The Future of Forestry,” C. S. Lewis outlines his poetic lamentation over the erosion of the environment.

C.S. Lewis recognises that the destruction of nature is very much an urgent matter. His attitude towards the environment would also be reflected in themes throughout his Chronicles of Narnia series, where being a defender of the forest is an indicator of a character being on Aslan’s side.

How did C.S. Lewis come to this view of the importance of Christians looking after God’s creation rather than dominating it. How did Lewis get so green?

The answer lies in the destruction and decimation of World War One. For C.S. Lewis and his friend, JRR Tolkein, World War One produced, in essence, an environmental holocaust.

This aspect of the conflict left a deep impression on both Christian authors and Oxford dons. Having personally experienced the awful prodigy of modern industry and technology - both men fought bravely in the trenches in France - they enlisted nature itself as a protagonist in their epic stories of good vs. evil.

Even before the war, Tolkien and Lewis had come to resent the encroachment of industrial life into rural England. Tolkien lamented "the tragedy and despair of all machinery laid bare," meaning the modern attempt to enhance our control over the world around us, regardless of the consequences.

In "The Lord of the Rings," Saruman the wizard "has a mind for metal and wheels; and he does not care for growing things, except as far as they serve him for the moment." The hateful realm of Mordor is sustained by its black engines and factories.

Likewise, Lewis viewed respect for nature as intrinsic to human happiness. In "The Chronicles of Narnia," his series of books for children, the various animals play a central role in the story. The smallest of creatures -- such as a mouse named Reepicheep -- display the greatest of human virtues. As biographer Alister McGrath observes: "Lewis' portrayal of animal characters in Narnia is partly a protest against shallow assertions of humanity's right to do what it pleases with nature."

The experience of war deepened this sensibility.

Both men enlisted as officers in the British Expeditionary Force and saw intense fighting at the front. Lewis was injured by mortar fire - the shell killed his sergeant standing a few yards away - and was shipped back to England to recover. "My memories of the last war," he wrote, "haunted my dreams for years." Tolkien survived the ferocious Battle of the Somme, but contracted trench fever and was taken out of harm's way. In the horror of the Somme he was given a vision of Mordor: the "dead grasses and rotting weeds" and "a land defiled, diseased beyond healing." As Tolkien acknowledged years later, the Dead Marshes "owe something to Northern France after the Battle of the Somme."

The two great authors met at Oxford in 1926, where they discovered a mutual love for mythology and English literature. Tolkien, a devoted Catholic, helped convert Lewis to Christianity. Lewis persuaded Tolkien to pursue his story about hobbits and Middle-earth.

Their influence on each other's literary imagination was subtle, yet profound. In the climactic scenes in both of their epic works - stories framed by a great war - nature itself is caught up in the conflict.In Lewis' "Prince Caspian," the character Trufflehunter explains to Caspian that it will be difficult to wake the spirits of the trees in the battle against Miraz, the unlawful King of Narnia. "We have no power over them. Since the Humans came into the land, felling forests and defiling streams, the Dryads and Naiads have sunk into deep sleep." Yet the war cannot be won without their help, and Aslan, the great Lion, summons them to join the battle: the "woods on the move."

Tolkien's humanoid trees, the Ents, are among the most memorable figures in fantasy. Led by Treebeard, the oldest living creature in Middle-earth, the Ents were created as guardians of the forest. Earlier wars had decimated the land, forcing the Ents to confine themselves to Fangorn Forest, where they hoped to avoid the War of the Ring. But Sauron's advance compels them to abandon their moral neutrality. "A thing is about to happen which has not happened since the Elder Days," explains Gandalf. "The Ents are going to wake up and find that they are strong."

At the start of the 20th century, when Tolkien and Lewis began their Oxford careers, enthusiasm over "the conquest of nature" was at a fever pitch in the industrialized West. The fever raged with horrific fury during the Great War.

In the Christian imagination of these authors, the assault on nature carried spiritual significance: Man's sins against nature will not go unpunished, and nature will take its revenge.

Contemporary Christians have always had an ambivalent if not hostile attitude to tackling environmental issues such as climate change, carbon emissions or other green issues like clean air and drinking water. This is particularly so in America where scientific illiteracy as well as a distrust in science in general is a particular feature of some Christian churches, especially amongst the so-called white evangelical churches. Science has become a punching bag in the so called Culture Wars in the US between left and right when it shouldn’t be. Thankfully this attitude is only prevalent in America and generally not shared by many church denominations and movements outside of America, especially in Europe, Africa and Asia.

A biblical worldview means accepting the fact that the earth is loved by God and humans have a responsibility to care for it. We have a responsibility to not strip the land of vegetation and to allow the earth to have what it needs to be fertile and productive. That’s not liberal environmentalism, that’s Bible. If man-made climate change is true (and it is), Christians ought to be the most outspoken and supportive of change, because they believe that God has tasked us all with caring for this planet in such a way that it thrives.

Such Christians recognise the need to be good stewards of God’s creation, especially nature. In this Lewis and Tolkein provided an early and important voice to ecological good stewardship and best illustrate the aesthetic intensity of Christian green and environmental consciousness and ultimately a call to action.

**C.S. Lewis looking out from his college rooms, Magdalen College, Oxford. Photo by Arthur Strong, 1947.

#CS lewis#lewis#quote#forest#woods#countryside#environment#green#urbanisation#christianity#religion#ecology#climate change

96 notes

·

View notes

Text

Five Exceptional Fantasy Books Based in Non-European Myth

Photo by Josh Hild

Don’t misunderstand me: I love reading well-written fantasy with roots in the familiar Celtic and English folklore of my childhood, but with the vast majority of High Fantasy being set in worlds closely akin to Medieval Europe, and a large amount of of Mythic Fiction drawing on legends of similar origin, sometimes the ground begins to feel too well trodden. There is, after all, an entire world of lore out there to draw from. That’s why I’m always thrilled to find excellent works of what I call “the Realistic Sub-Genres of Fantasy” based in or inspired by myths from other cultures. Such books not only support inclusiveness, but also expand readers’ experiences with lore and provide a wide range of new, exciting realities to explore. So, if you are looking for something different in the realm of Fantasy, the following novels will provide a breath of fresh air.

The Golem and the Jinni by Helene Wrecker

In this beautifully written novel, Wrecker draws on both Middle-Eastern and Jewish mythology to tell the stories of two unwilling immigrants in Edwardian New York and the unlikely friendship that springs up between them. Chava, an unusually lifelike golem created for peculiar purposes, has only days worth of memories and is practically childlike in her innocence. Ahmad the Jinni has lived for centuries, but is trying to reclaim his forgotten past. The former is as steady and calm as the earth she’s made from while the latter is as volatile and free-spirited as the fire within him. Both must learn to live in an unfamiliar new culture and find their places in a city too modern for myths even as they hide their true natures. It’s a wonderful metaphor for the experiences of immigrants everywhere, who often find themselves feeling like outsiders—isolated and even overwhelmed— as they struggle to adapt to life in an alien society.

Full of memorable characters, vivid descriptions, and interesting twists, The Golem and the Jinni takes readers on a journey that is driven as much by internal conflict as external action. The setting of 1900’s Manhattan is well-researched and spectacular in its detail. Wrecker blends two old-world mythologies into the relatively modern Edwardian world with a deft hand. The result is not only fascinating, but also serves to illustrate the common early-twentieth-century experience of an immigrant past colliding with an American future.

The Tail of the Blue Bird by Nii Ayikwei Parkes

One part Detective Mystery and one part Magical Realism, this novel invites readers to experience modern-day Ghana in a way that is both authentic and profound. When Kayo, a forensic pathologist just beginning his career, is pushed into investigating a suspected murder in the rural village of Sonokrom, the last thing he expects is to have a life-changing experience. Soon, however, he gets the acute sense that the villagers may know more than they’re letting on. When all of the latest scientific and investigative techniques fail him, even as odd occurrences keep dogging his steps, Kayo is finally forced to accept that there is something stranger than he thought about this case. Solving the crime will require more than intelligence and deduction; it will require setting his disbelief aside and taking the traditional tales and folklore of an old hunter seriously. Because whatever is happening in Sonokrom, it isn’t entirely natural.

This novel is brilliant not only because of its deep understanding of Ghanaian society and realistic setting, but also because of Parkes writing style. The narrative is gorgeously lyrical and everything within it is described with a keen, insightful eye. The dialogue is full of local color, and while some may find the pidgin English and native colloquialisms difficult to follow, I found that the context was usually enough to explain any unfamiliar terms. Sometimes the narrative feels a little dreamlike, but that is exactly the way great Magical Realism should be. The Tail of the Blue Bird insistently tugs readers to a place where reality intertwines with myth and magic, all while providing an authentic taste of Ghanaian culture.

The Deer and the Cauldron by Jin Yong

During the reign of Manchu Emperor Kang Xi, China is in a state of barely-controlled sociopolitical unrest. Many of the older generation remember the previous dynasty, and there still remain vestiges of a resistance movement hidden among the populace. As his forces continue to hunt down the malefactors, called the Triad Societies, the boy-emperor turns to his unlikely friend and ally: a young rascal known only as Trinket. This protagonist is a study in contrasts: lazy yet ambitious, cunning yet humorous, roguish yet likable, foul-mouthed yet persuasive. Born in a brothel, Trinket has made his way by his wits alone. At age twelve, he accidentally sneaked into the Forbidden City—a bizarre occurrence in itself—afterward befriending Kang Xi. Now, rising quickly through the ranks, he is on a mission to (ostensibly) find and weed out the Triad Societies, and he uses the opportunity to infiltrate various organizations, playing their leaders against one another for his own gain. With a dangerous conspiracy brewing in the Forbidden City itself, however, he is forced to choose sides and decide what is most important to him: friendship, fortune, or freedom. Supernatural occurrences, daring escapades, and moments of deep introspection abound as Trinket struggles to navigate the perilous maze his life has become.

This novel is like a gemstone: bright, alluring, and many faceted. At times it may seem somewhat simple on the surface, but looking closer reveals new depths and multiple layers. Full of intrigue, action, horror, and even laughs, The Deer and the Cauldron mirrors not only the complexities of its setting, but those of the China the author himself knew during the Communist revolution. By blending together history, fantasy, realism, humor, and subtle political commentary, Yong not only beautifully captures these social intricacies but also creates a narrative that is as thoroughly engaging as it is unapologetically unique.

Like Water for Chocolate by Laura Esquivel

Magical realism related to food has almost become a movement in itself, with novels like Aimee Bender’s The Particular Sadness of Lemon Cake, Joanne Harris’ Chocolat, and Sarah Addison Allen’s Garden Spells all finding their places in readers’ hearts. Originally published in 1992, Like Water for Chocolate helped create this fascinating trend, and it has become something of a modern classic in the fantasy genre.

The narrative centers around Tita de la Garza, a mid-twentieth century Mexican woman possessing deep sensitivity, a strong will, and a special talent for cooking. Born prematurely, Tita arrived in her family’s kitchen, tears already in her eyes. It is in that room where she spends most of her childhood, being nurtured and taught by the elderly cook, Nacha. The relationship that flourishes between Tita and her caregiver is a special gift, as it provides the girl not only with the compassion and support her own mother denies, but also with a passion and skill for creating incredible, mouth-watering dishes. At Nacha’s side, Tita learns the secrets of life and cookery, but she also learns one terrible fact: thanks to a family tradition, she is destined never to have love, marriage, or a child of her own. Her fate, rather, is to care for her tyrannical widowed mother, Mama Elena, until the day the older woman dies. With a vibrant, independent spirit, sixteen-year-old Tita flouts this rule, falling deeply in love with a man named Pedro who asks for, and is denied, her hand in marriage. Undaunted, the young man agrees to wed one of Tita’s older sisters, Rosaura, instead, as he believes this to be the only way he can be close to the woman he loves. Thus begins a life-long struggle between freedom and tradition, love and duty, which is peppered throughout with supernatural events and delicious cuisine. So great is her skill in cooking that the meals Tita prepares take on magical qualities all their own, reflecting and amplifying her emotions upon everyone who enjoys them. Controlled and confined for much of her existence, food becomes her outlet for all the things she cannot say or do. The narrative itself echoes this, by turns as spicy, sweet, and bitter as the flavors Tita combines. At its heart, this is as much a tale about how important the simple things, like a good meal, can be as it is a story about a woman determined to be her own person and choose her own fate.

Cuisine is fundamental to this novel, with recipes woven throughout the narrative, but that is only a part of its charm. In the English translation, the language is beautiful in its simplicity. The characters often reveal hidden depths, especially as Tita grows up and is able to better understand the people around her. Heartfelt in its joys and sorrows, Like Water for Chocolate glows with cultural flavor and a sense of wonder. It’s a feast for the spirit, and like an exquisite meal, it never fails to surprise those who enjoy it.

The City of Brass by S. A. Chakraborty

When I first read this novel, I found the early chapters enjoyable and engaging, but felt the story was no more than a typical, if especially well-written, work of mythic fiction. The deeper I got into the narrative, however, the more wrong I was proven. The City of Brass is anything but ordinary. While basing her work in Middle-Eastern lore and history, Chakraborty nonetheless manages to create a setting and story that are both wonderfully unique. Lush, detailed, and bursting with magic and intrigue, this book spans the lines between several sub-genres of fantasy without ever losing its balance.

Beginning in eighteenth-century Egypt, the narrative follows a quick-witted antiheroine. Nahri doesn’t live by the rules of her society. She doesn’t believe in magic or fate or even religion. Orphaned for most of her life, survival has required her to become a con artist and a thief. As a result, she is practical and pragmatic, a realist who has never even considered donning rose-colored glasses, and the last person who would ever expect anything supernatural to occur. Which, of course, means that it does, but the way in which it is handled is intricate and interesting enough not to feel trite. When Nahri’s latest con—a ceremony she is pretending to perform and doesn’t believe in even slightly—goes awry, and the cynical young woman finds herself face to face with a Daeva. Magical beings, it transpires, are real after all, and this one is furious. To both of their dismay, he’s also bound to Nahri, who soon realizes that he has an agenda of his own. In return for rescuing her (and refraining from killing her himself) Dara, the Daeva warrior Nahri accidentally summoned, wants her to pull of the biggest con of her life: pretending to be the half-human heir to the throne of his people. Worse still, she soon realizes that Dara, whose mentality sometimes seems a little less-than-stable, actually believes she may be exactly who he claims. He has something planned, and his intentions may not be in her best interest. Dragged unwillingly into a strange world of court intrigue, danger, social upheaval, and magic, Nahri quickly discovers that some things remain familiar. People are ruled by prejudices, the strong prey on the weak, and she can’t fully trust anyone. The stakes, however, are higher than ever, and Nahri will need all of her wits, cunning, and audacity if she wants to survive.

This novel was thoroughly enjoyable, and in fact prompted me to buy the following books in the trilogy as they became available. Chakraborty’s style is lyrical, her world building is superb, her plot is intricate, and her characters are well-developed. She not only frames unfamiliar words and ideas is easily-comprehensible contexts, but weaves those explanations smoothly into the narrative. The culture, mythology, and history surrounding her tale are all carefully researched, but the tale itself is nonetheless unique. What begins feeling like a fairly ordinary mythic fiction novel will pleasantly exceed readers’ expectations.

So, while we, as fantasy readers, love the works of authors like J. R. R. Tolkien, Marion Zimmer Bradley, and Charles de Lint, there is also a plethora of other enchanting books to enjoy. Exploring magical realism and mythic fiction based in cultures and folklore from all around the globe ensures that our to-read lists will always hold something unexpected and exciting to surprise us. So, if you’re starting to feel like you’re in a bit of a reading rut, or if you’re simply looking to expand your horizons, open up new realms of imagination by opening up one of the novels above. Who knows see where it will lead you? You may just discover a new favorite to add to your bookshelf. Happy reading!

#book#books#novel#novels#fantasy#mythic fiction#magical realism#non-European#culture#cultural#review#reviews#fantasy literature#literature#book lover#book lovers#bookworm#international#suggestino#suggestions#African#Mexican#Middle-Eastern#myth#mythology#legend#lore#Asian#Chinese#Central American

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Edible Insects and Their (Possible) Appearance in Our Near-Future

Edible insects often make their way into the public eye through appearances in dystopian worlds. Movies like Snowpiercer and Blade Runner portray a pessimistic future of bug bars and the like, a product of societal deterioration. Despite their negative connotations, insect dishes are not only accepted by various cultures, but, considering their abundance and nutritional efficiency, they are also compelling options to help build a sustainable world. Their public personas aside, edible insects should really be "normalized" because of historical reliability and environmental sustainability!

Over 1,900 species of insects are edible, so it should come as no surprise that diets have included insects since the dawn of civilization. While Americans may associate them with poverty and food insecurity, insects in foreign cuisines appear according to their cultural significance.

Household pests such as ants and termites appear in African, Asian, and South American markets as popular snacks. Europe, too, has traditional insect-based foods such as the Italian Casu Marzu, a sheep-milk cheese with live larvae.

Human diets have included insects even before civilization and agriculture. Fossilized feces found in North American caves contained ants, larvae, and ticks, indicating that insects formed a significant part of early human diets. Twelve-thousand-year-old cave paintings in Spain illustrate a collection of edible insects and bee nests. Man of Bicorp Cave Painting

Ruins in Shanxi, China dated to around 2,500 years BCE contained silkworm cocoons with holes, suggesting that ancient people ate the pupae inside.

There is nothing to suggest that eating insects didn’t “age well” scientifically as we learned more about their associations with disease because they are about as sanitary as typical livestock! To let thousands of years worth of food history become irrelevant due to modern consumer disgust would be a waste of a perfectly natural food source.

Despite the long-tested reliability of edible insects, people may hesitate to replace their typical Western foods because of concerns about food safety. To comfort even the most anxious of anti-insect consumers, thorough examinations have been conducted on the food safety risks of insect-based foods. They focus on the safety of the insect itself as well as the conditions found in the processing environment. Foodborne pathogens are largely absent in insects, and manufacturers are meticulous in ensuring that safe products reach consumers.

The insect industry is ready to go, and their main obstacle is popularity. The 21st century is an exciting time to jump into this emerging industry, and the nutritional and economic potential of one of the largest ecological groups on Earth could deliver us into a new age. Try some edible insects for yourself :)

Citations:

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0924224418304874

https://www.sciencedirect.com/book/9780128028568/insects-as-sustainable-food-ingredients

https://www.scienceabc.com/eyeopeners/are-insects-the-future-of-food.html

1 note

·

View note

Text

COVID-19 Reading Log, part 3

Parts One and Two

16. An Astounding Atlas of Altered States by Michael J. Trinklein. I’ve actually read this book before but hadn’t realized it until I got started—its first edition was titled simply Lost States. It’s a coffee table book. Each double page spread has one map depicting the proposed or presumed boundaries of a piece of territory that never became a US state, and the other page is information on the history of that non-state. Most of them fall into three categories—attempts to carve up Western territories that didn’t make it (for values of the west as far east as the Appalachian Mountains, because some of these are from the 1700s), splits to existing states due to interstate politics, or overseas territories, either those actually owned by the USA (Puerto Rico, the Marshall Islands) or not (Greenland, Newfoundland). I would be just as interested, if not more so, in a more in depth approach to the subject (maybe focusing on a smaller number of candidates).

17. Written in Bones edited by Paul Bahn. This is a primer to forensic archaeology, in the form of a number of short articles about a variety of sites involving human remains. This is the first book I’ve read so far I would consider genuinely bad. Here’s why: a number of controversial topics are covered, but poorly (I will share some of these claims in parentheticals—note that these are not my claims, but the book’s). The coverage runs from being dismissive of the controversy (e.g. the butchered remains found among Anasazi dwellings are absolutely not evidence of cannibalism, and anyone who claims otherwise is ignorant) to ignoring the existence of any controversy at all (e.g. Kennewick Man is definitely not related to modern Native American groups and syphilis definitely existed in Europe before the Columbian Exchange). It claims that two skeletons found in the Tower of London, which haven’t been scientifically examined since the 1930s, are almost certainly the lost sons of Edward IV, supposedly murdered by Richard III. On top of that, several articles use outdated and super-racist terminology, like splitting human populations into “Negroid”, “Caucasoid” and “Mongoloid”. And these are just things that I noticed, and I’m by no means an expert. What else could this book be misleading about, or what outright lies is it telling? Skip this one.

18. Fantastic Archaeology by Stephen Williams. This book was chosen in part with the intention of washing the bad taste of Written in Bones out of my mouth, which it succeeded in doing. The focus of the book is on pseudoscientific takes on the archaeology of pre-contact Native Americans and various claims for pre-Columbian European expeditions to North America. The Kensington Rune Stone, Prince Madoc and various Lost Tribes related forgeries are taken to task here. The author is clearly an expert, both on the actual archeology and on the frauds, cranks and rogue professors (the author’s coinage) that appear. The final chapter is a lengthy survey of the state of the art knowledge of what actual pre-Columbian North American cultures were like, based on the evidence when the book was written (early 1990s).

19. Dinosaur Facts and Figures: The Theropods and Other Dinosauriformes by Rubén Molina-Pérez and Asier Larramendi. This book is right on the borderland between being a popular and technical volume. It’s mostly data—lengths of dinosaurs, drawings of bones, footprints and eggs, estimates for weights and speeds—but it’s sold at popular literature prices (aka reasonable for a 250 page book with color illustrations). The focus is on the largest and smallest theropods, sorted first by clade, and then chronologically. The real selling points here are the thoroughness and the art. Unusually for anything approaching the popular sphere, dinosaurs discussed in depth include animals not formally described, ichnotaxa and ootaxa (that’s names based on footprints and eggs, respectively), and various nomen dubia (specimens with doubtful or useless names attached). Some of the animals in the book are getting full life reconstructions in print for the first time, and there’s definitely species and specimens I’d never heard of throughout. The book is translated from Spanish, and there are a few places where the translation is awkward or missed a word or two. It’s the first in a three part series—the book on sauropods and their relatives releases later this year, and I am looking forward to it.

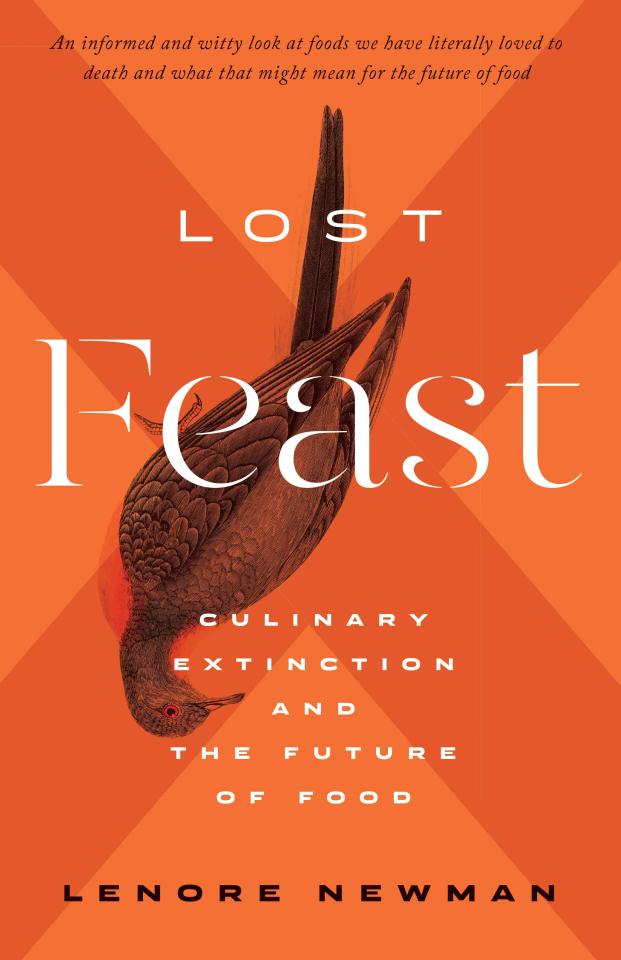

20. Lost Feast by Lenore Newman. The book is on the subject of culinary extinction, the loss of species or cultivars eaten by humans. The author is a food researcher and the book straddles the line between cultural history and ecology. Some of the losses are from overharvesting (e.g. passenger pigeons and fisheries), some are from market forces (e.g. the reduction of plant cultivars) and others are from a combination of factors, not fully understood (like colony collapse disorder). The titular feast is a series of dinner parties held throughout the book in honor of losses and featuring near misses (pear cultivars are a running theme). This book is also a milestone for this particular project—this is my last (physical) library book! All of the libraries in my area are closed due to quarantine.

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

Birds, Bonapartes, Biological Nomenclature

The more that I learn about the Bonaparte clan, the more I realize that the family most famous for Napoleon I, the emperor and military genius, had connections to basically everything in the 1700s and 1800s. One shocking connection to me was that Tarrare (that hungry guy during the French Revolution who ate basically everything) worked under Alexandre de Beauharnais, who was married to a woman known as Rose Tascher de La Pagerie. After Alexandre de Beauharnais perished during the Reign of Terror, Rose remarried to a young general named Napoleon Bonaparte and adopted the name of Josephine.

Pictured above: the curl-crested aracari, photographed by Lonnie Huffman

Just as I never expected the Bonaparte clan to have a connection to the infamous hungry guy, I also never expected them to have a real impact on ornithology. It seems so out there, so disconnected from the politics and conquest that are usually associated with their name. While reading about birds in the past, I’ve frequently stumbled upon the name “Bonaparte” or “Beauharnais” (Josephine’s martial name by her first husband, and the last name of both of her children, who became instrumental in Napoleon’s securing of power throughout Europe)[1]. I always assumed that the names simply came from people wanting to honor monarchs that hailed from the Bonaparte-Beauharnais clan, as naming new species (well, new to western scientists) after monarchs was trendy during that time. One such example is the curl-crested aracari, whose scientific name is “pteroglossus beauharnaesii.” I mention this specific example because the curl-crested aracari is awesome and vastly underrated compared to better-known species in the Ramphastidae family, such as toco toucans.

I recently learned, however, that the Bonaparte family’s influence on ornithology is more than just symbolic! I decided to dig a little bit deeper into learning why the name “Bonaparte” appears so frequently in bird information, and I found out that Napoleon’s nephew and the son of his brother Lucien, Charles Lucien Bonaparte was a prominent ornithologist who was the authority on 165 genera, 203 species, and 262 subspecies. Learning about this was really cool for me because two of my primary passions in life are Napoleon and birding, and I find it really exciting that there’s this unexpected and kind of random intersection of the two.

According to the IOC World Bird List, among the species studied by Bonaparte are a subspecies of oriental turtle dove of Europe and Asia (Streptopelia orientalis erythrocephala), the blue-winged goose (Cyanochen cyanoptera) endemic to Ethiopia, and the Pel’s fishing owl (Scotopelia peli) endemic to Africa.

Pictured above: the blue-winged goose, photographed by Dick Daniels

Among Bonaparte’s notable contributions to ornithology is also his naming of the New World dove genus, Zenaida, after his wife. Bonaparte married Zénaïde Bonaparte, who was his cousin and the daughter of Joseph Bonaparte, older brother of Napoleon and Lucien Bonaparte. This was incestuous and nasty, but what can you really expect from European nobility? The Zenaida genus notably includes the Zenaida dove (the type species) and the mourning dove. Mourning doves are common where I live, and from now on, whenever I hear its iconic call of “hoo hoo hoo,” I’ll think of the Bonaparte family.

Pictured above: The mourning dove. “Dove by Almaden Lake” by Don Debold

Bonaparte also was an early supporter of John James Audubon, who was then relatively unknown as a naturalist. I would also like to note that Audubon grew up in France[2], and used a fake passport to flee to the United States so that he wouldn’t be conscripted into the Napoleonic Wars. (I can only imagine what Bonaparte must have said if/when Audubon told him, “Yeah, I came to this country as a draft dodger because I didn’t want to die in all those wars that your uncle keeps dragging us into.”) Bonaparte recommended him for the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia (now a part of Drexel University) while living in Philadelphia, where he and his wife moved after getting married so that they could be with Joseph Bonaparte, who lived in exile in the city. Unfortunately, Audubon’s bid for membership because George Ord, an ornithologist and member of the academy, disliked his style of painting. Well, George Ord isn’t the one amongst them who has become basically synonymous with ornithology and bird conservation in the United States, so evidently, Audubon got the last laugh.

On a slightly different note, a fascinating aspect of biological nomenclature that I had never considered before learning about Bonaparte was the frequency at which people named species after their own political leaders, like the afore mentioned curl-crested aracari. Now that royalty and monarchies aren’t nearly as relevant to most people’s lives as they were during the time of the Bonapartes, the trend has evolved so that people name species to honor celebrities and other pop culture icons. (Though, whereas before famous people had birds named after them, now discovery of a terrestrial vertebrate animal is uncommon enough that people only get bugs and worms unless they’re lucky.) Take, for example, Aleiodes shakirae, Aleiodes gaga, and Aleiodes colberti, wasps that are named after Shakira, Lady Gaga, and Stephen Colbert, respectively. There’s even a whole Wikipedia page dedicated to listing the creatures whose scientific names take after the Harry Potter series. (There’s a whole dinosaur named Dracorex hogwartsia, which translates to “dragon king of Hogwarts”! I’m jealous! … Also, read another book, smh.)

Anyway, anyone who complains that people are making everything political these days clearly hasn’t read their history. One of Bonaparte’s notable contributions to ornithological nomenclature was his naming of Wilson’s bird-of-paradise, whose colloquial name comes from Alexander Wilson, a prominent American ornithologist who laid the foundation for ornithology in the United States. The scientific name for Wilson’s bird-of-paradise is “cicinnurus respublica,” with respublica commonly being translated as “public affair” or “commonwealth.” Bonaparte wanted to deviate from the tradition of naming species after royalty and royalty-adjacent people, and instead honor the concept of the republic. In my opinion, this is disdain for royalty was entirely performative, given that Bonaparte was a descendant of an imperial dynasty, was a prince himself, and was afforded his privilege in life by the fact that his uncle seized power in France, installed himself as the country’s leader, and eventually crowned himself emperor.

Pictured above: Wilson’s bird-of-paradise, photographed by Serhan Oksay

I’m always taken aback when I learn about just how connected the world was [for wealthy white men] before modern technology, and the influences that people from completely different geographical backgrounds could have on each other. It is important to acknowledge that so many of the naturalists from this time period were able to make such developments in their fields not because of their intrinsic talent as biologists and ornithologists, but also because of their immense connections and lucky circumstances that paved their way to success. Also, the “discovery” of many New World avian species wasn’t true “discovery” at all, because the indigenous people of the Americas had lived with those species for millennia. It was only “discovery” for westerners, who placed their mark of colonization on those species by naming them after rulers and other prominent western figures.

Although Bonaparte definitely had the passion to contribute so much to ornithology, he came from an incredibly powerful political dynasty that could bankroll his studies. He could travel wherever he wanted to and obtain any specimen that he wanted to obtain because of who his family was. Similarly, although Audubon certainly had a passion for birds and talent as an illustrator, he was only able to develop those skills through meeting the right people and having the generational wealth to do whatever he wanted in life. That’s not to say that every single ornithologist came from a position of wealth and power — the aforementioned Wilson, for example, was a weaver who lived in poverty in Scotland before emigrating to the United States and working as a schoolteacher. I don’t think that that makes the contributions of people like Bonaparte and Audubon less important or meaningful to the field (I’m also not an ornithologist so I don’t have that authority), but, as with most fields even today, it’s worth thinking about that the people who made these contributions reflect only the people with the access to the most resources.

NOTES: [1] Although Josephine is frequently referred to as “Josephine de Beauharnais,” she never actually went by that name during her lifetime. When she was married to Alexandre de Beauharnais, she went by Rose, and only adopted “Josephine” after having married Napoleon, because he liked the nickname. [2] Audubon was born in Haiti, where his father owned a plantation that he sold in 1789 when tensions began to rise between white slave-owning colonizers and enslaved people of African ancestry. The elder Audubon had a number of mixed-race children by a mistress who had ¼ African ancestry, but only the younger Audubon and his sister, who were both considered white, were moved to France alongside him.

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Gothic Science: The Era of Ingenuity & the Making of Frankenstein, by Joel Levy, Andre Deutsch Ltd, 2019. Info: carltonbooks.co.uk.

Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein was conceived against the backdrop of rapid change in the scientific world. And the science that inspired it is almost as strange as the novel itself. Shelley grew up surrounded by several of Europe’s prominent scientific thinkers and was familiar with experimentation into reanimation of corpses as well as the heated debate over “the elixir of life”. She was a frequent visitor to St Bart’s operating theatre, where spectators witnessed surgery performed without anaesthetic. Her monster was born in an era of bodysnatching, dissections and the philosophy of Vitalism. This book offers an engrossing insight into the world of science in late-eighteenth and early-nineteenth-century Europe, through the prism of the seminal science fiction novel. Illustrated with line drawings and colour plates, it reveals how the monster was conceived, suggests the real-life basis for Victor Frankenstein and describes in vivid detail the experiments that might have led to the Creature’s birth. It also looks at incarnations of the monster since the book was published and modern interpretations of the “mad scientist”, as well as looking ahead to permanent bionic limbs, implants and other wonders.

Contents: Introduction Chapter One. Chemical Revolution: Getting High and Losing Your Head Chapter Two. Electric Fluids and Animal Spirits: Galvanism, Voltaic Piles, Electrochemistry and the Start of a New Era Chapter Three. The Right Stuff: Vitalism, Spontaneous Generation and the Meaning of “Life” Chapter Four. Of Man and Monster: Frankenstein and the Science of the Mind Chapter Five. Anatomy of Horror: Dissection, Murder and Resurrection in the Romantic Era Chapter Six. To the Ends of the Earth: Polar Exploration and the Frozen Wastes Chapter Seven. Before and After: The Painful Birth and Dreadful Afterlife of Frankenstein and His Monster Further Readings Index and Credits

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

Take a Virtual Tour of the Smithsonian American Art Museum's Humboldt Exhibition

https://sciencespies.com/nature/take-a-virtual-tour-of-the-smithsonian-american-art-museums-humboldt-exhibition/

Take a Virtual Tour of the Smithsonian American Art Museum's Humboldt Exhibition

SMITHSONIANMAG.COM | May 1, 2020, 9 a.m.

It’s not what you’d expect from an art show. At the end of a long corridor, beyond a pulled-back heavy burgundy brocade curtain, a full-scale mastodon skeleton fills much of the rotunda-like space of the gallery. The fossil is the centerpiece of “Alexander von Humboldt and the United States: Art, Nature, and Culture,” an exhibition at the Smithsonian Museum of American Art. The show was poised to open with much fanfare earlier this year just as the COVID-19 crisis shuttered the museum. Today the stately mastodon sits waiting for crowds to return. In the meantime, viewers can go on a virtual tour of the show through a new video put together by the museum’s senior curator, Eleanor Jones Harvey.

For Harvey, the 11-foot tall, 20-foot long elephant ancestor is the uber statement on what polymath Alexander von Humboldt (1769-1859) meant to the American politicians, scientists, artists and writers who fawned over him during his brief six-week visit to the United States in 1804, and who became a part of his global network of admirers for a huge chunk of the late 18th and early 19th centuries.

The mastodon was a coup for SAAM—it is the first time the fossil will be back in America since 1847, when it made its way through Europe and ultimately ended up at The Hessisches Landesmuseum Darmstadt in Germany. A video shows the disassembly in Darmstadt and three-day reassembly at the museum.

youtube

Alexander von Humboldt and the United States: Art, Nature, and Culture

A Prussian-born geographer, naturalist, explorer, and illustrator, Alexander von Humboldt was a prolific writer whose books graced the shelves of American artists, scientists, philosophers, and politicians. Humboldt visited the United States for six weeks in 1804, engaging in a lively exchange of ideas with such figures as Thomas Jefferson and the painter Charles Willson Peale.

Buy

The mastodon—exhumed under the guidance of artist Charles Willson Peale and cobbled together with wood by a leading sculptor of the day—represents the intersection of art, culture and science, says Harvey. Similarly, Humboldt studied multiple disciplines and believed that “artists need to have enough scientific background to know what they are painting, and scientists should maintain a sense of aesthetic wonder to appreciate as they are collecting,” Harvey says.

Almost 300 plants and 100 animals are named after the Prussian-born naturalist. Have you heard of the Humboldt penguin? The Humboldt Squid, which swims in the Humboldt Current? How about the Humboldt lily, found in California, which also has a Humboldt County? Forests, rivers, peaks, mountain ranges and even a patch of plains on the moon have been named for him. Humboldt, who published 36 books, including his five-volume masterpiece, Cosmos, was a man of many interests—so many that it’s hard to catalog them all.

He mentored many young scientists and accumulated a vast network of admirers and collaborators through some 25,000 letters, often beseeching others to share findings from their explorations as a means of accumulating data to prove his “unity of nature” theory: that everything on the planet is interconnected, says Harvey. Humboldt may have been one of the first to warn about climate change, noting that the devastation of forests in Venezuela had changed the local climate.

Read more about Alexander von Humboldt in this article by Eleanor Jones Harvey

Exhumation of the Mastodon by Charles Willson Peale, ca. 1806-08

(Maryland Historical Society, Baltimore City Life Museum Collection, Gift of Bertha White in memory of her husband, Harry White)

“He’s really one of the last great enlightenment scientists and one of the first great modern scientists,” Harvey says, noting that his work was grounded in meticulously analyzed data.

Humboldt’s holistic perspective—and his desire to make people understand nature’s importance to humanity—is more relevant than ever, notes Hans-Dieter Sues, chair of paleontology at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History, in the preface to the exhibition catalogue.

Most present-day scientists “tend to focus on specific ecological changes without considering the complex web of interactions between humans and the environment,” writes Sues. Environmentalists also concentrate too much on the preservation of a particular species, “rather than taking a more integrated approach that also considers humans.”

“There is an urgent need for a Humboldtian perspective if we are to understand and address the unparalleled crisis now facing our species,” Sues writes.

Niagra by Frederic Edwin Church, 1957

(National Gallery of Art, Corcoran Collection, Museum Purchase, Gallery Fund)

It’s hard to overstate Humboldt’s popularity during his heyday—the late 18th and early-to-mid-19th centuries. Widely traveled and broadly known in Europe, he was able to secure backing from the King of Spain to travel throughout South America, Mexico and Cuba between 1799 and 1804, documenting plant life, geology, climates, peoples and discovering the location of the magnetic equator, allowing him to “recalibrate his equipment and take the most accurate readings to that point of longitude and latitude in the Americas,” according to Harvey.

His book, Personal Narrative of Travels to the Equinoctial Regions of the New Continent during the Years 1799–1804, and other writings, excerpted in newspapers, gained him fans in the United States. Humboldt arranged a stopping over in America at the end of the southern hemisphere journey, primarily to meet President Thomas Jefferson, who “he suspected was his intellectual equal,” but also to get a close-up look at democracy and to possibly explore the Louisiana Territory, says Harvey.

He was greeted like a rock star by Peale when he disembarked in Philadelphia and feted by other intellectuals during his visit. He arrived in America at an auspicious time, says Harvey. Humboldt believed that the nation should capitalize on its natural wonder—that places like Niagara Falls and Natural Bridge in Virginia (on land owned by Jefferson) were just as monumental as European castles and cathedrals.

The Natural Bridge, Virginia by Frederic Edwin Church, 1852

(The Fralin Museum of Art at the University of Virginia, Gift of Thomas Fortune Ryan)

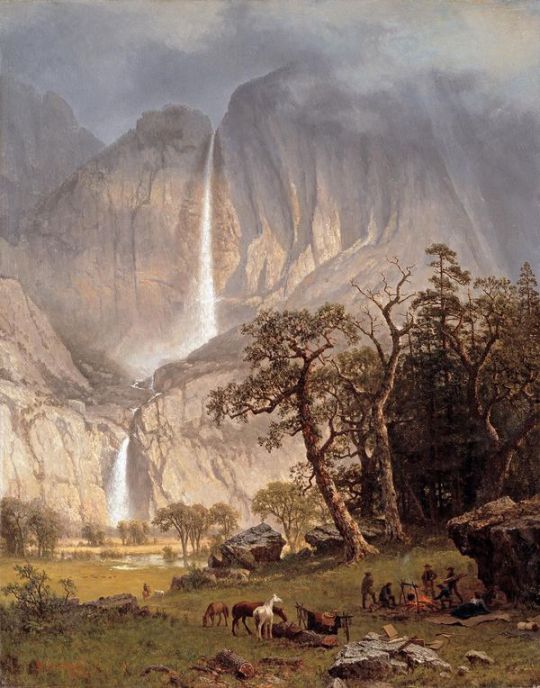

Cho-Looke, The Yosemite Fall by Albert Bierstadt, 1864

(Timken Museum of Art, Putnam Foundation)

The Peale mastodon—exhumed in upstate New York in 1801—fed into the mythology Jefferson hoped to create: that everything in America was bigger and better. Mammoth mania took over America after Peale displayed the fossil at his Philadelphia museum in late 1801. The unearthing of the bones is magnificently recalled in Peale’s 1806 painting, Exhuming the First American Mastodon.

Humboldt had written to Jefferson hoping to finagle an invite to the White House by mentioning that he’d found some mammoth teeth in the Andes. It worked, and he soon found himself hobnobbing with a network of American politicians, painters, writers and scientists. Among those who became a part of the Humboldt Hive: James Fenimore Cooper, Edgar Allan Poe, John Muir, Henry David Thoreau, Frederic Church, Walt Whitman and Samuel F.B. Morse.

The Prussian eventually came to consider himself half-American. Though he never visited the U.S. again after the 1804 trip, American luminaries frequently came to his Paris residence to bask in his presence. By 1847, Humboldt had been made a member of seven American scientific and cultural organizations.

Humboldt inspired a bevy of artists to ground their work in nature, including some of the greatest landscape painters of the time, Albert Bierstadt and Church. Twenty works by Church and two of Yosemite by Bierstadt are featured in the exhibition. Church’s paintings of Niagara Falls, Natural Bridge, and several Andean peaks, which he visited during a trip that recreated, step-by-step, Humboldt’s expedition through the same region, transport the viewer into a towering vision of nature.

Throughout his travels and his life, Humboldt was an advocate for social justice. “He thought the one flaw in American democracy was that it would not abolish slavery,” says Harvey. He urged James Madison to consider ending slavery, telling him that “nature is the domain of liberty.” Humboldt backed the anti-slavery 1856 presidential candidacy of John C. Fremont—who, during earlier explorations of the American west that were inspired by Humboldt, paid tribute to the scientist by naming various features after him, including a river in Nevada.

Valley of the Yosemite by Albert Bierstadt, 1864

(Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Gift of Martha C. Karolik for the M. and M. Karolik Collection of American Paintings)

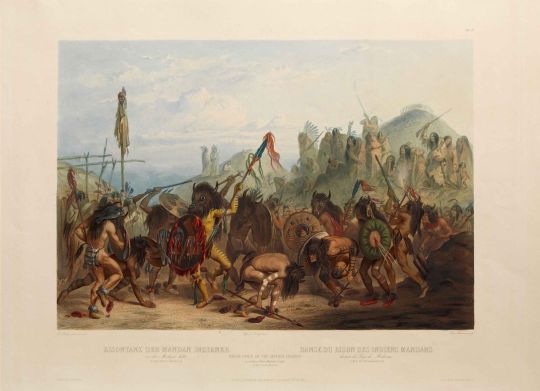

The plight of Native Americans also concerned Humboldt, especially in the wake of the Indian Removal Act of 1830. He convinced Prince Maximilian zu Wied-Neuwied, a protégé, and artist Karl Bodmer, to replicate part of the Lewis and Clark expedition to document the tribes of the Upper Missouri River. The exhibition features excerpts from the Prince’s journals and finely detailed watercolors of tribe members executed by Bodmer.

Humboldt also became friends with artist George Catlin, who had begun immersing himself in the documentation of America’s vanishing tribes starting in 1830. They meet in Paris, where Catlin has brought his portraits of Native Americans and a group of people from the Iowa tribe to educate the French—and shore up his dwindling finances. “It is the first and only time Humboldt will meet North American Indians,” says Harvey. Humboldt ends up touring the Louvre with some members of the tribe, one of whom kept a diary of the events of that trip.

A number of original Catlin portraits are on display, as is an 1845 painting depicting the visit to France, Karl Girardet’s Danse d’indiens Iowas devant le roi Louis-Philippe aux Tuileries (Dance of the Iowa Indians before the King Louis-Philippe at the Tuileries).

Not surprisingly, Humboldt is even connected with the founding of the Smithsonian Institution. When the Prussian traveled to England in 1790 to connect with a mentor there, he also ended up being introduced to a young chemist, James Smithson—the same Smithson whose bequest eventually created the Smithsonian in 1846.

Bison Dance of the Mandan Indians in front of Their Medicine Lodge in Mih-Tutta-Hankush by Alexandre Damien Manceau, engraver, after Karl Bodmer

(Joslyn Art Museum, Omaha Nebraska; 1986.49.542.18, Photograph © Bruce M. White, 2019)

The two reconnected in Paris in 1814, and spent a year in friendship, hanging out with liberal pro-American and pro-Democracy factions—making Smithson a bit of an outlier among his British compatriots. Humboldt and Smithson shared a love of collecting and analyzing, and spreading knowledge.

Well before the Smithsonian was established, Peale had already envisioned a national institution dedicated to the arts, sciences and American ideals and asked Humboldt to convince Jefferson to buy his museum collection as the foundation. Jefferson wasn’t interested in purchasing Peale’s materials. But the idea of a national institution continued to be discussed in Washington and elsewhere for decades. In 1835, Smithson’s last heir died and the estate was then, as directed by Smithson, bequeathed to the U.S. After much debate, Congress decided to accept the money. American attorney Richard Rush was dispatched to London to bring the dollars home, to, as Smithson put it, “found at Washington, under the name of the Smithsonian Institution, an Establishment for the increase & diffusion of knowledge among men.”

Those words “are a Humboldtian credo,” writes the museum’s director Stephanie Stebich in the introduction to the exhibition catalog. Most of the men ultimately involved in setting up the Smithsonian Institution had either known Humboldt, corresponded with him, or admired him, says Harvey.

“The entire Smithsonian is in some ways the bricks and mortar realization of everything that Humboldt cared about,” she says. The Institution’s 19 museums, the National Zoo, and 21 research centers and programs encompass Humboldt’s vast interests.

To make that point, the final gallery in the show features nine ongoing Smithsonian projects “that reflect Humboldtian enterprise,” says Harvey.

Though Humboldt was celebrated throughout the 19th century—with big parties in American cities every decade starting in 1869—the rise of Germany as a hostile power in the early 20th century caused Americans to stop teaching about the great scientist. Essentially, the lights went out on Humboldt, says Harvey.

“I’m trying to turn the lights back on and dust for his fingerprints, and say, ‘hey, he was here, and here and here,’” she says.

Currently, to support the effort to contain the spread of COVID-19, all Smithsonian museums in Washington, D.C. and in New York City, as well as the National Zoo are temporarily closed. The exhibition “Alexander von Humboldt and the United States: Art, Nature, and Culture” goes on view at the Smithsonian American Art Museum in 2020.

Listen to Sidedoor: A Smithsonian Podcast

It took a zealous Prussian explorer to show the colonists what they couldn’t see: a global ecosystem, and their own place in nature. Check out this season five episode, “The Last Man Who Knew It All,” about Alexander von Humboldt.

#Nature

1 note

·

View note

Note

take it as you’d like that you were the first person i thought of asking in this matter (congrats, you are now “That Historical Smut Blogger”), but: do you have any fairly detailed informational resources for (fiction) writing about historical condoms? especially/specifically late 19th/early 20th c. europe. materials, use/design, popularity of different styles? (what might be used by dudes screwing dudes on a budget in wwi/the jazz age?) even just like, some research directions would be superb

(This is the best kind of question to be asked, EVER. Anon, I salute you.)

The good news about the late 19th and early 20th centuries is that you're squarely out of the animal-skin condom era -- you’re dealing with the rubber and later the latex condom! (For better or for worse.) Comstock-type laws limiting the propagation of information related to contraception were beginning to pass away, and WWI was kind of a watershed for condom distribution -- German troops were issued condoms, British and American troops were less lucky. If you want to indicate that a character was in the service or had sufficient contact with servicemen implying a connection to the wartime use of condoms could be handy. (Apparently NZ soldiers were uncommonly well equipped.) This is where the coinage of condoms as prophylactic devices ("pros", "prophos", "prophies") became popular, as well as “preventative" and "preservative" language emphasizing STI protection for the wearer rather than prevention of conception.

Condoms of the 1920s and 1930s come largely in tins, sometimes round (with a modern-style rolled condom within) and sometimes square or rectangular, with paper-banded condoms pinched in an oblong shape; I associate this era with some uhhhh """"exotic"""" motifs (think, uh, Orientalism) as well as attempts to lean into the medical/scientific nature of the product, but this might be primarily an American thing.

Sleazy brands abounded. In many cases, the name or packaging alone was all that communicated the nature of the product: The alluring female image shown on the Safway label (Fig. 1), for example, appears elsewhere under the brand name “Carmen” but the product inside could be completely different. Other names suggestive of sexy females included Contessa, Co-Ed, Fantasy, Golden Pheasant, Peacock, and Merry Widows. Other names suggested dapper or soldierly gentlemen, exotic or luxurious places and practices, high-tech products, or nearmilitary protection: Royal Knight, Prince, Champ, Duke, Trilby; Sheik, Sultan, Ramses, Escudor; Ultrex, Texide, Silver Tex, Deer Skin, Cleo-Tex, Skin Tight; and Patrol, Surête, Three Cadets, Guardian, and Protectos. Even Schmid’s high-quality Sheik and Ramses condom tins were exotically (if not erotically) illustrated.

- '“When Pirates Feast … Who Pays?” Condoms, Advertising, and the Visibility Paradox, 1920s and 1930s', Paula A. Treichler

Brands varied country by country in this period, as well as the law's attitude toward condoms vis-a-vis obscenity, birth control, public health, etc. By the interwar years condoms could be found in pretty much every European country, with localized brand names. Most European condoms were imported from Germany; later, the Durex brand native to England gained prominence there in the late 1920s. Some of the brands from this era, like Trojan and Durex, have stuck around.