#including a silent film in like 1912

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Titanic was a little bitch movie star who died tragically young in spectacular fashion. We know. Is nobody going to talk about her older sisters who both had incredibly successful careers? They fought in the war!

Britanic deserved a Medal of Honor, acting as a hospital vessel until a mine sank her in Greece. (Side note, sank in a tenth of the time Big T did, and 97% of the victims survived 🙄). She never got into the entertainment biz. She wanted to be a nurse, and she was a damn good one.

Olympic stepped on people and they liked it. She tore a U-boat in half (also a friendly boat but they had it coming), and served as troop transport until the war ended. They called her “Old Reliable”. Here that Unsinkable? They called her reliable. She was in service two years before the Titanic was born, and she was still serving two decades after the Titanic sank. The Olympic retired during the Great Depression, for which the Axis are eternally grateful.

And then the Nasties made The Titanic(1943) as anti-capitalist propaganda, But it ended up banned because of the uncomfortable parallels with a special kind of camping

Anyway, one of the titanic’s fuel depots was on fire for most of the trip, which resulted in the ship leaning slightly. Fortunately, the side with a hole in it was the opposite side, so it balanced back out for a while.

#titanic#britanic#Olympic#white star line#died young#real heroes#drama queen#sinkable#veteran appreciation#did you know?#Germany made two other Titanic films#including a silent film in like 1912#just 2 years after she sank#I know nothing about the other one#they probably made more#everyone seems to do it.#movie making rite of passage#I don’t know.#my hyperfixations and history classes both end well before I was born.#which is a damn shame#knowing about what goes on around me#instead of what happened a hundred years ago#sounds super useful

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

I'm all for the changes they made to the story although I'm still saddened they chose not to include "I'm Wishing" and "Someday My Prince Will Come" for the Snow White remake. Are they too outdated for the current audience or could they have still fit in somehow, you think?

I think if they had kept the Prince rather than introducing Jonathan, they could have kept those songs. I honestly think they could have made it work.

My solution would have been to make the Prince be a childhood friend of Snow White's. This has precedent, not only in Snow White and the Huntsman, but all the way back to the 1912 stage play and its 1916 silent film adaptation (the one that inspired Walt). In all three of those versions, Snow White and the Prince knew each other as children when her father was alive, though they haven't seen each other since the Queen took over. The 1912 play also has Snow White mention that the Prince sends her a valentine every year.

In fleshing out Snow White and the Queen's backstory, the new movie could have shown her growing up with the Prince, then reaching the age where they begin to have feelings for each other, only for the Queen to separate them. She could lie that she's sending Snow White away to finishing school (another detail from the 1912 play) only to secretly banish her to the kitchen and reduce her to a scullery maid instead. Then their meeting scene at the well could become a reunion scene. "I'm Wishing" and "One Song" could be sung with the basis of an already-existing relationship, without needing to change a single lyric.

"Someday My Prince Will Come" would be trickier, because of the inherent passivity in Snow White's waiting for him to come to her. But maybe it could be placed in a new context. Maybe dialogue could establish that Snow White wishes she could go looking for the Prince, but can't because she's in hiding from the Queen. So the dwarfs could resolve to help Snow White find a way to let the Prince know where she is without letting the Queen know. Some type of secret communication system in which Snow White is an active participant... maybe a network of different animals who can deliver a letter to him, or something like that. Then, as they put the plan into action, Snow White can sing the song, expressing her faith that someday soon the Prince will find her thanks to their efforts.

If this version also emphasizes Snow White as a leader and future queen, then maybe a new verse could also be added to the song, in which she imagines all the good that she and the Prince will do together for their kingdoms. That way her dreams will revolve around more than just romance.

These are my two cents on how I think the songs could still have worked in modern remake.

#disney#snow white#snow white and the seven dwarfs#snow white 2025#songs#i'm wishing#one song#someday my prince will come

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

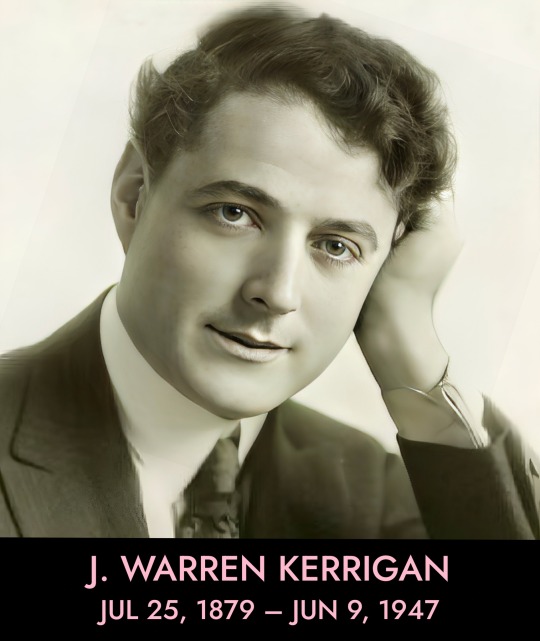

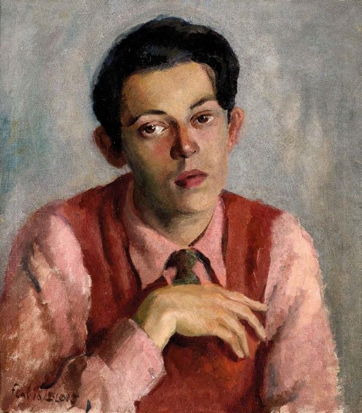

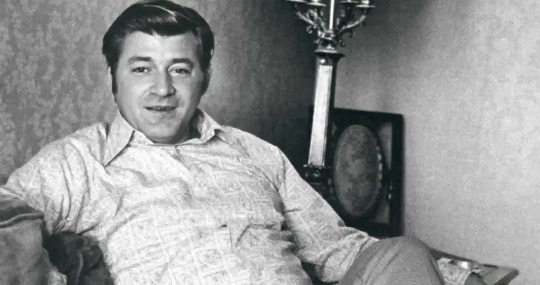

J. Warren Kerrigan (Jack to his friends) was a popular actor in the early years of silent film. He made as many as 300 movies and shorts between 1910 and 1924.

In 1917, a fan magazines voted Kerrigan the most popular actor. The press dubbed him “The Great God Kerrigan”.

Contrary to Kerrigan on screen persona as a “fast-shooting, buckskin-wearing roughneck”, he had a reputation for being effeminate. Allan Dwan, a director, would harass him on the set. In 1912, while shooting the short “The Poisoned Flume”, Dwan held Kerrigan’s head underwater for the amusement of the crew, forcing the star struggled to break free.

Kerrigan got his revenge. By the next year his star power had risen. He threatened the studio that he would go on strike if they didn’t fire Dwan. Kerrigan got his way.

Kerrigan lived with his mother. When asked by reporters, he said he liked women best when "they leave me alone." As long as he made the studio money, in those early days of Hollywood, they didn’t care. And Kerrigan made them plenty of money.

In 1917 Kerrigan used some of his wealth to build a large house on Cahuenga Blvd, near the Hollywood Bowl. He lived there with his mother. Two years later he met James Vincent, a "juvenile" actor, on the set of “Out of Court”. Vincent, 18 years younger than Kerrigan, was invited to move into the house on Cahuenga. Later Vincent would be referred to as Kerrigan’s secretary or gardner.

In 1922, Hollywood was rocked by off-screen scandals involving movie stars, including Roscoe Arbuckle’s trial for murder of a starlet. The studios hired Will Hays, a Republican politician and Presbyterian minister, to help improve Hollywood’s image with both the public, but perhaps more importantly, Congress.

In 1924, Hayes recommended his "Formula" that would severely control the content of the movies. Plus the studios would be mandated to control the behavior of its stars.

Perhaps it’s no coincidence that Kerrigan decided to retire from acting in 1924. But the next year, he continued to assert his masculinity, by purchasing an ad in Motion Picture Magazine:

“From the time I was 13, I had the support of a family on my hands, Later, my mother and I were so very close that I didn't feel the need of any other companion. It is only since I have been alone that I have had time and opportunity to think of marriage and - so far - I haven't found any girl who would think about it with me! But I will fool 'em! I'm going to catch one, one of these days --- you'll see! J. Warren Kerrigan”

Kerrigan and Vincent would continue to live together at the house on Cahuenga Boulevard. Kerrigan died in 1947 from pneumonia at the age of 67. Sadly, nine months later Vincent took his own life. They had been together for 28 years.

#gay icons#in the closet#J. Warren Kerrigan#silent films#fast-shooting buckskin-wearing roughneck#effeminate#lived with his mother#hollywood scandals#fatty arbuckle#hays office

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rewind the Tape —Episode 4

Art of the episode

Just like we did for the pilot and for episodes two and three, we took note of the art shown and mentioned in the fourth episode while we rewatched it. Did we miss any? Can you help us put a name to the unidentified ones? Do you have any thoughts about how these references could be interpreted?

Bust of a Woman with Her Left Hand on Her Chin

Edgar Degas, 1898 [Identified by @terrifique.]

Degas, whose work already appeared in the second episode, was a French painter of the 19th to early 20th century. His impressionist paintings often depicted ballet dancers, racehorses, and human portraits of isolation.

Krumau on the Molde, Kneeling Girl with Spanish Skirt and Self portrait in a jerkin with right elbow raised

Egon Schiele, 1912, 1911 and 1914

Schiele, whose work we have also been seeing around Rue Royale since the pilot, was an Austrian Expressionist painter, very prolific despite passing before turning 30. His work is recognizable for its transgressive portrayal of the nude body, including his nude self-portraits; but his later oeuvre features many landscapes.

The Kitten's Art Lesson

Henriette Ronner Knip, 1821-1909 [Identified by @terrifique.]

Knip was a Dutch-Belgian romantic style artist best known for paintings of animals, particularly cats and dogs of a playful nature. See more of her work here.

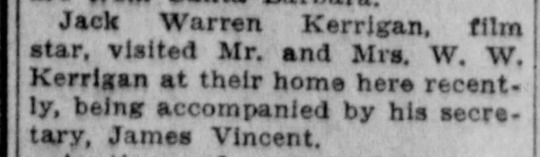

Nosferatu

F.W. Murnau, 1922

Nosferatu is a silent expressionist horror film from the legendary German director F.W. Murnau. It is an unauthorized adaptation of Bram Stoker's Dracula. While not a commercial success upon release in 1922, film historians now consider it an influential and revolutionary film in the horror genre. Since it has been in the public domain since 2019 in the U.S., it is now free to stream on YouTube.

Untitled piece

Sadie Sheldon, undated [Identified by @lanepryce.]

The incredible metalwork piece on the wall of the reading room was made by a New Orleans-based artist, for New Orleans... pizzeria! It was made for Pizza Delicious, using dozens of tin cans. Sheldon describes her work as "site and time-specific projects from found materials (...) related to adaptability, renewal, and appreciating the objects of our everyday life".

New York

George Bellows, 1911 [Identified by @nicodelenfent, here.]

Several of Bellows' pieces have been featured in previous episodes. He was an American realist painter, known for his bold depictions of urban life in NYC. His work "revolutionized the conventions of the traditional American urban vista and surpassed the efforts of other contemporary urban realists" [x].

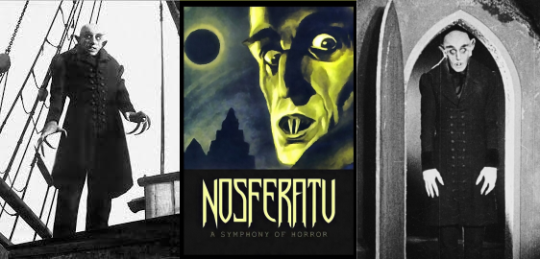

Backstage at the Opera

Jean Beraurd, 1889

Beraurd was a Russian born French painter known for his depictions of Parisian life and society during the Belle Epoque. [Identified by @nicodelenfent.]

Unidentified works

In Claudia's room: above the Knip we can see a painting of what looks like four people, maybe women sitting at a balcony. To the left of the door we can see, on top, a floral bouquet over a dark background, and below that, an illustration or painting of a woman with flowers over a bright pink background.

You can see all unidentified works from the first season in this post. If you spot or put a name to any other references, let us know if you'd like us to add them with credit to the post!

Starting tomorrow, we will be rewatching and discussing Episode 5, A Vile Hunger for your Hammering Heart. We can't wait to hear your thoughts!

And, if you're just getting caught up, learn all about our group rewatch here ►

#the vampire claudia#claudia iwtv#louis de pointe du lac#daniel molloy#lestat de lioncourt#vampterview#interview with the vampire#iwtv#amc interview with the vampire#interview with the vampire amc#amc iwtv#iwtv amc#IWTVfanevents#rewind the tape#analysis and meta#art of the episode#the ruthless pursuit of blood with all a child's demanding

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

THIS DAY IN GAY HISTORY

based on: The White Crane Institute's 'Gay Wisdom', Gay Birthdays, Gay For Today, Famous GLBT, glbt-Gay Encylopedia, Today in Gay History, Wikipedia, and more … November 21

Transgender Day Of Remembrance (since 1999) set aside to memorialize those who were killed due to anti-transgender hatred or prejudice (transphobia). The event is held on November 20, founded by Gwendolyn Ann Smith, to honor Rita Hester, whose murder in 1998 kicked off the "Remembering Our Dead" web project and a San Francisco, California candlelight vigil in 1999. Since then, the event has grown to encompass memorials in hundreds of cities around the world.

1873 – Daniel Gregory Mason, American composer, born (d.1953); Mason came from a long line of notable American musicians, including his father Henry Mason. He studied under John Knowles Paine at Harvard University from 1891 to 1895, continuing his studies with George Chadwick and Goetschius. In 1894 he published his Opus 1, a set of keyboard waltzes, but soon after began writing on music for his primary career. He became a lecturer at Columbia University in 1905, where he would remain until his retirement in 1942, successively being awarded the positions of assistant professor (1910), MacDowell professor (1929) and head of the music department (1929-1940). He was the lover of composer-pianist John Powell.

1883 – Edwin August (d.1964) was an American actor, director and screenwriter of the silent era. He appeared in 152 films between 1909 and 1947. He also directed 52 films between 1912 and 1919. He co-founded Eaco Films in 1914.

Edwin was born Edwin August Phillip von der Butz in St. Louis, Missouri, to August and Sarah Butz. He was educated at the Christian Brothers College.

He began working with Biograph Studios in New York as early as 1908 and moved to Hollywood with that company in 1910. He starred in several films by D. W. Griffith, who was also with the company, and continued to work well into the 1930s as a writer and director.

In 1916, he entered his name as a candidate for President of the United States, and spoke out against censorship in cinema. The candidate wasn't taken very seriously, and perhaps that wasn't the point. He didn't like the road that his industry was going down, and wanted to voice his opinion in the hope of change.

A co-star, Blanche Sweet, would later bluntly state: "He was a homo." He owned a chicken ranch at 648 South Figueroa in Hollywood and was friends with gay silent film star J. Warren Kerrigan and most likely Kerrigan's long time partner James Vincent.

Edwin passed away from cerebral metastatic disease on March 4, 1964 at the Motion Picture County Hospital in Woodland Hills, Los Angeles County, California.

1916 – James Pope-Hennessy (d.1974) was a British biographer and travel writer.

James Pope-Hennessy was born in London on 20 November 1916, the younger son of Ladislaus Pope-Hennessy, a soldier from County Cork, Ireland, and his wife, Una, the daughter of Arthur Birch, Lieutenant-Governor of Ceylon. He was the younger of two sons; his elder brother, John Pope-Hennessy, was an English art historian, museum director and writer of note. James came from a close-knit Catholic family and was educated at Downside School and at Balliol College, Oxford, but generally showed a lack of interest in formal education and did not enjoy his time at either Downside or Oxford.

Largely owing to his mother's influence, he decided to become a writer and left Oxford in 1937 without taking a degree. He went to work for the Catholic publishers Sheed and Ward as an editorial assistant. While working at the company's offices, in Paternoster Row in London, he worked on his first book, London Fabric (1939), for which he was awarded the Hawthornden Prize. During this period, he was involved in a circle of notable literary figures including Harold Nicolson, Raymond Mortimer and James Lees-Milne.

He left the publishers in 1938 when his mother found him a job as private secretary to Hubert Young, the Governor of Trinidad. Although his time abroad provided the material for his later West Indian Summer (1943), he disliked both the West Indies and the atmosphere of Government House. The outbreak of the Second World War gave him an excuse to return to Britain, where he enlisted as a private in an anti-aircraft battery under the command of Sir Victor Cazalet. Rising through the ranks, he was transferred to military intelligence, given a commission and spent the latter part of the war as a member of the British army staff at Washington.

Pope-Hennessy enjoyed his time in the United States and made many friends there. After the end of the war he wrote an account of his experiences in America. On his return to London in 1945 he shared a flat with the British intelligence officer Guy Burgess, who later defected to the Soviet Union. He had a brief spell as the literary editor of The Spectator between 1947 and 1949, before he decided to travel to France and write Aspects of Provence, which was published in 1952.

He would eventually establish himself as one of the leading biographers of his time; his first effort in this direction being a two-volume biography of Monckton Milnes that appeared in 1949 under the titles The Years of Promise and The Flight of Youth. This was followed by further biographies of the Earl of Crewe and of Queen Mary, for which he was created Commander of the Royal Victorian Order in 1960. He also wrote a life of his grandfather, the colonial governor John Pope Hennessy, under the title Verandah (adapted as a documentary for BBC Television under the title "Strange Excellency", 1964), followed by an account of the Atlantic slave traffickers, Sins of the Fathers (1967).

In 1970, he took out Irish citizenship and went to live at Banagher in County Offaly, and during the next few years produced authoritative biographies of both Anthony Trollope and Robert Louis Stevenson. Trollope himself had chosen James' grandfather, John Pope Hennessy, as the basis for the character Phineas Finn in his novel of the same name. Robert Louis Stevenson was published posthumously and without revision in 1974. He became a popular figure in Banagher, evidenced by the fact that he was asked to adjudicate at a local beauty pageant and the horse fair, the oldest in Ireland. On being given a large advance he returned to London in 1974 to begin work on his next subject, Noël Coward.

Despite being a successful professional writer, Pope-Hennessy was careless with money. He suffered a series of financial crises and often relied on the goodwill of friends to get him by. A homosexual, he was a heavy drinker and frequented back-street bars and shady pubs where he mixed with a rough crowd, associations that eventually contributed to his death when he was brutally murdered on 25 January 1974 in his London flat by three young men. He had been sexually acquainted with one of them.

1941 – Oliver Sipple, the man who saved President Gerald Ford's life, was born today.

Sara Jane Moore attempted to assassinate U.S. President Gerald Ford outside the St. Francis Hotel in San Francisco, just seventeen days after Lynette "Squeaky" Fromme had also tried to kill the president. Moore was forty feet away from Ford when she fired a single shot at him. The bullet missed the President because bystander Oliver Sipple grabbed Moore's arm and then pulled her to the ground, using his hand to keep the gun from firing a second time. Sipple said at the time: "I saw [her gun] pointed out there and I grabbed for it. I lunged and grabbed the woman's arm and the gun went off." The single shot which Moore did manage to fire from her .38-caliber revolver ricocheted off the entrance to the hotel and slightly injured a bystander.

Sipple goes for the gun.

Sipple, a decorated Marine and Vietnam War veteran, was immediately commended by the police and the Secret Service for his action at the scene. The news media portrayed Sipple as a hero but would eventually report on his outing by Harvey Milk and other San-Francisco gay activists. Though he was known to be Gay by various fellow members of the gay community, Sipple had not made this public, and his sexual orientation was a secret from his family. He asked the press to keep his sexuality off the record, making it clear that neither his mother nor his employer had knowledge of his orientation; however, his request was not complied with.

The national spotlight was on him immediately, and Milk responded. While discussing whether the truth about Sipple's sexuality should be disclosed, Milk told a friend: "It's too good an opportunity. For once we can show that Gays do heroic things, not just all that ca-ca about molesting children and hanging out in bathrooms." Milk contacted the newspaper.

Several days later Herb Caen, a columnist at The San Francisco Chronicle, exposed Sipple as a Gay man and a friend of Milk. Sipple was besieged by reporters, as was his family. His mother, a staunch Baptist in Detroit, refused to speak to him. Although he had been involved with the Gay community for years, even participating in Gay Pride events, Sipple sued the Chronicle for invasion of privacy. President Ford sent Sipple a note of thanks for saving his life. Milk said that Sipple's sexual orientation was the reason he received only a note, rather than an invitation to the White House.

Sipple filed a $15 million invasion of privacy suit against Caen, seven named newspapers, and a number of unnamed publishers, for publishing the disclosures. The Superior Court in San Francisco dismissed the suit, and Sipple continued his legal battle until May 1984, when a state court of appeals held that Sipple had indeed become news, and that his sexual orientation was part of the story.

According to a 2006 article in The Washington Post, Sipple went through a period of estrangement with his parents, but the family later reconciled with his sexual orientation. Sipple's brother, George, told the newspaper, "(Our parents) accepted it. That was all. They didn't like it, but they still accepted. He was welcomed. Only thing was: Don't bring a lot of your friends."

Sipple's mental and physical health sharply declined over the years. He drank heavily, gained weight to 300 lb (140 kg), was fitted with a pacemaker, became paranoid and suicidal. On February 2, 1989, he was found dead in his bed, at the age of forty-seven. Earlier that day, Sipple had visited a friend and said he had been turned away by the Veterans Administration hospital where he went concerning his difficulty in breathing. His $334 per month apartment near San Francisco's Tenderloin District was found with many newspaper clippings of his actions on the fateful September afternoon in 1975. His most prized possession was the framed letter from the White House.

Sipple held no ill will toward Milk, and remained in contact with him. The incident brought him so much attention that, later in life, while drinking, he would regret grabbing Moore's gun. Sipple, who was wounded in the head in Vietnam, was also diagnosed paranoid schizophrenic according to the coroner's report.

Sipple's funeral was attended by 30 people, and he was buried in Golden Gate National Cemetery in San Bruno, California. A letter addressed to the friends of Oliver Sipple was on display for a short period after his death at one of his favorite hangouts, the New Belle Saloon:

"Mrs. Ford and I express our deepest sympathy in this time of sorrow involving your friend's passing..." President Gerald Ford, February, 1989

In a 2001 interview with columnist Deb Price, Ford disputed the claim that Sipple was treated differently because of his sexual orientation, saying: "As far as I was concerned, I had done the right thing and the matter was ended. I didn't learn until sometime later — I can't remember when — he was Gay. I don't know where anyone got the crazy idea I was prejudiced and wanted to exclude Gays."

1990 – A London judge convicted 14 gay men of committing criminal assaults upon themselves because of their participation in S&M. All 14 receive prison sentences.

1998 – John Geddes Lawrence and Tyrone Garner of Texas were ordered to pay fines of $125 each after being arrested for having sex in their home. The couple refused to pay and announced they would challenge the Texas sodomy law - initiating what became known as the historic "Lawrence vs Texas" Supreme Court decision which decriminalized homosexual sex.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

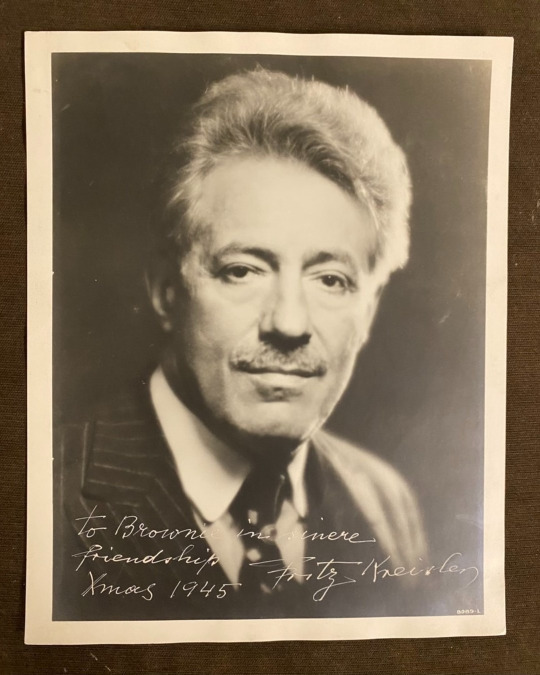

OTD in Music History: Legendary violin virtuoso Friedrich "Fritz" Kreisler (1875 - 1962) makes his American debut at Steinway Hall in New York City in 1888, kicking off his 1st American tour (1888–1889) with famed concert pianist Moritz Rosenthal (1862 - 1946).

A remarkable child prodigy, Kreisler first studied music at the Vienna Conservatory from 1882-1885 (where his teachers included Anton Bruckner [1824 – 1896]) before moving on to the Paris Conservatory from 1885-1887 (where his teachers included Léo Delibes [1836 - 1891] and Jules Massenet [1842 – 1912]).

When Kreisler graduated from the Paris Conservatory at the tender age of 12, he was awarded a prestigious gold medal -- beating out 40 other violinists (all of whom were at least 20 years old) to secure that honor.

Kreisler was also a noted composer who wrote a number of enduringly popular short pieces for the violin.

Some of these compositions were pastiches, ostensibly penned in the style of other composers -- and indeed, Kreisler originally "passed them off" as the work of famous Baroque composers including Giuseppe Tartini (1692 - 1770) and Antonio Vivaldi (1678 - 1741).

When Kreisler finally came clean about this deception in 1935, a number of prominent music critics who had been completely taken in by this ruse raised a fuss in the press.

Kreisler, however, took great pleasure in wryly pointing out that whatever their qualms, the critics themselves had already conceded the high quality of the music itself: "The name printed on the sheet music may now change, but the musical value of the underlying notes remains very much the same!”

PICTURED: A publicity headshot showing the elderly Kreisler, which he signed and inscribed to a friend with "Xmas" wishes in 1945.

Today: Watch the only known (unfortunately silent) film footage of legendary violin virtuoso and composer Fritz Kreisler (1875 – 1962) playing his violin, which was shot at the house of a family friend c. 1930. It is actually rather surprising that we don’t have *more* film footage of Kreisler in action (including sound footage), considering that he lived into the 1960s. The most likely explanation comes from the fact that Kreisler was involved in a serious traffic accident in 1941, which put him in a coma for a week and largely derailed his later career. This unfortunate incident probably robbed of us many additional opportunities for film footage with sound to be shot... According to one eagle-eyed observed, Kreisler appears to be playing part of the “Sarabande” from J.S. Bach’s (1685 – 1750) 1st Violin Partita (BWV 1002).

#classical music#music history#composer#classical composer#classical studies#maestro#Fritz Kreisler#Kreisler#violin#violinist#virtuoso#Concerto#Concert#classical musician#classical musicians#classical history#history of music#historian of music#musician#musicians#music education#music theory#cadenza#Steinway Hall#Philharmonic

13 notes

·

View notes

Video

Mistinguett by Truus, Bob & Jan too! Via Flickr: French postcard by J.D. & Cie, Paris, series 20. Photo: DuGui (?). Caption: Mistinguette, Eldorado. Sent by mail in 1904. French actress and singer Mistinguett (1875-1956) captivated Paris with her risqué routines. She became the most popular French entertainer of her time and the highest-paid female entertainer in the world. She appeared more than 60 times in the cinema. Mistinguett was born as Jeanne Florentine Bourgeois in Enghien-les-Bains, France, in 1875. She was the daughter of labourer Antoine Bourgeois, and seamstress Jeannette Debrée. At an early age, Jeanne aspired to be an entertainer. She began as a flower seller in a restaurant in her home town, singing popular ballads as she sold her flowers. When a song-writing acquaintance made up the name Miss Tinguette, Jeanne liked it. She made it her own by joining it together and eventually dropping the second S and the final E (Mistinguett). Mistinguett debuted at the Casino de Paris in 1895 and appeared in shows at the Folies Bergère, Moulin Rouge, and Eldorado. In 1908 she made her film debut in the short silent film L'empreinte ou La main rouge/The Impression or the Red Hand (Henri Burguet, 1908) for Pathé Fréres. Her co-star in this film was Max Dearly, who chose her the next year to be his partner in creating La valse chaloupée (or the Apache Dance) in the Moulin Rouge. Between 1909 and 1915, she appeared on the stages of the Paris music halls but also in dozens of short films for Pathé, including Fleur de pavé/Her Dramatic Career (Albert Capellani, Michel Carré, 1909) with Charles Prince, Une petite femme bien douce/A Sweet Little Lady (George Denola, 1910) which she also wrote, and Le clown et le pacha/The Clown and the Pasha (Georges Monca, 1911), again with Prince. In Une bougie récalcitrante/A Stubborn Spark Plug (Georges Monca, 1912), she appeared for the first time opposite the much younger Maurice Chevalier. With Chevalier, she would have a relationship of more than 10 years. The most successful film among her Pathé films was Les misérables (Albert Capelani, 1913), a four-part serial based on the famous novel by Victor Hugo. During the First World War Mistinguett continued to appear in Pathé productions like the comedies La valse renversante/The Amazing Waltz (Georges Monca, 1914) again opposite Maurice Chevalier, and Rigadin et la jolie manucure/Rigadin and the Pretty Manicurist (Georges Monca, 1915) with Charles Prince. In Italy she appeared in La doppia ferita/The Double Injury (Augusto Genina, 1915). Opposite the legendary Harry Baur, she starred in Chignon d'or/The Gold Chignon (André Hugon, 1916) and Fleur de Paris/Flower of Paris (André Hugon, 1916). In 1916 she first recorded her signature song Mon Homme. It was popularised under its English title My Man by Fanny Brice and has become a standard in the repertoire of numerous pop and jazz singers. In 1918, she succeeded Gaby Deslys at the Casino de Paris and remained the undisputed star of nocturnal Paris until 1925. In 1919 her legs were insured for the then astounding amount of 500,000 francs. During a tour of the United States, she was asked by Time magazine to explain her popularity. Her answer was: "It is a kind of magnetism. I say 'Come closer' and draw them to me." After WWI Mistinguett's film career halted. She only appeared in a few more films, including L'île d'amour/Island of Love (Berthe Dagmar, Jean Durand, 1928) and Rigolboche (Christian-Jaque, 1936). Mistinguett's stage career prospered and lasted over fifty years. Her last film appearance was as herself in the Italian musical Carosello del varietà/Variety Carousel (Aldo Bonaldi, Aldo Quinti, 1955). In 1956, Mistinguett died at the age of 80. She is buried in the Cimetiere Enghien-les-Bains, Île-de-France, France. Sources: Wikipedia and IMDb. And, please check out our blog European Film Star Postcards.

#Mistinguett#Mistinguette#French#Actress#Artist#Singer#Music#Hall#Cabaret#Theatre#Film Star#European#Film#Cinema#Star#Vintage#Postcard#Eldorado#JD & Cie#DuGuy#flickr

1 note

·

View note

Text

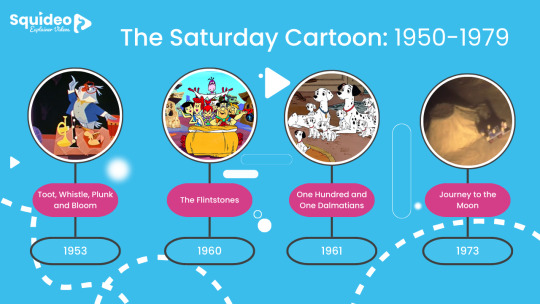

It’s hard to pin the invention of animation on a single date. Film archivists have estimated that more than 90 percent of films made before 1929 are lost forever, which makes it almost impossible to say with any certainty which first can be credited to which film.

Multiple techniques, developments and technologies were instrumental in the creation of animation as we know it today. And this progression has continued, with more variations created every decade since the 1900s. Squideo is going to dive into the evolution of animation, from its murky beginnings to the multibillion dollar industry it has become.

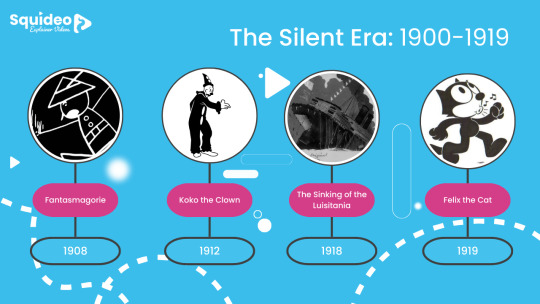

The first animated film has been credited to multiple titles, including Pauvre Pierrot (1892), The Enchanted Drawing (1900), Fantasmagorie (1908) and Gertie the Dinosaur (1912). The names of other films have been listed in newspapers from the time, but since they’ve been lost these cannot be verified.

Like live-action films of the time, these early hand-drawn animation films were silent. They would be shown in cinemas or, as in the case of Winsor McCay’s Gertie the Dinosaur, at circuses and vaudeville acts. Animators of this age were working without the later constraints of studios or censorship, and had a lot of freedom to develop new animation styles and techniques.

The realism of early animation was greatly improved by the invention of rotoscoping, first showcased in 1912’s Koko the Clown by Max Fleischer. The rotoscope technique traced motion picture footage of a human performer, and is still used to this day albeit with the use of a computer rather than manually tracing film frames.

youtube

Animation improved rapidly within these twenty years, and this is perhaps best demonstrated with The Sinking of the Lusitania (1918), by Winsor McCay. The detail from this film, which was the longest made at that time (12 minutes) and the first confirmed example of an animated documentary, was vastly improved from his first because of the introduction of cel animation. This is named after the celluloid sheets which replaced paper in the animation process, and saved animators the time of creating multiple drawings of backgrounds and stationary objects.

The realistic animation style of McCay’s film, which was widely praised, was quickly eclipsed however by a new style which swept across the American animation industry: rubber hose animation. This debuted in 1919 when Pat Sullivan and Otto Messmer created Felix the Cat.

Felix the Cat was a huge draw for 1920 cinema goers, becoming a hugely popular character which featured in 89 animated cartoons between 1919 and 1925. However the creators’ reluctance to embrace sound film technology, which was debuted in 1923, saw the ultimate decline of Felix and paved the way for Disney’s eventual domination of the American animation industry.

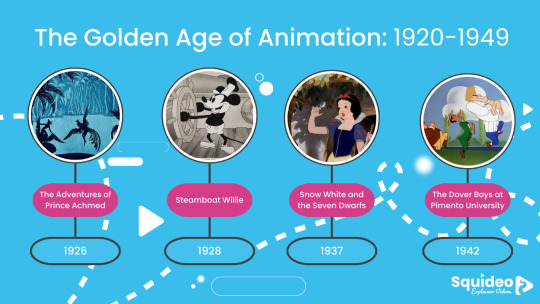

Despite sound technology emerging early in the decade, it took time for animators to adapt it into their work. Some of the most notable animated works of the period are still silent, such as the first claymation film, Long Live the Bull (1926), and the first feature-length animated film: The Adventures of Prince Achmed (1926). Created by Lottie Reiniger, this silhouette animated film famously introduced the multiplane camera which the Walt Disney Company would later reinvent and use for their first feature-length film Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937). It was Disney which arguably popularised sound in animation, with their animated short Steamboat Willie (1928).

Walt Disney was convinced that sound technology would change the future of film, and was the secret to making his new animated character – Mickey Mouse – a hit with audiences. He was right, which imbued the company with the confidence to use other animation technologies that emerged. Five years later, Disney became the first animation company to use Technicolor when it released Flowers and Trees (1932).

youtube

Disney’s style began to dominate animation, especially in America. For the smaller studios that lacked their budget and workforce, there was a desire for a different animation style that could be made faster and cheaper. Limited animation was the solution, and it ushered in a new era.

Warner Brothers Animation launched in 1933. It would soon become notable for its Looney Tunes series, but it was Merrie Melodies that brought in limited animation. This technique reduced the number of drawings required for each frame, in turn reducing the work for animators and speeding up the production process. It was ideal for television, a burgeoning medium post-WW2, which had smaller screens than cinemas. The Dover Boys at Pimento University (1942) was one of the first notable uses of the technique.

A lot of innovation during this next period occurred in television production, and it also saw the rise of amateur productions as filming equipment became more readily available to the public. Changing technology additionally created a divide between film and television animation which had differing styles and quality standards during these decades.

Disney was the first studio to use CinemaScope for its animated short Toot, Whistle, Plunk and Bloom (1953). Created by 20th Century Fox in that same year, it remained popular until its discontinue in 1967. This changed the aspect ratio of productions to accommodate wider, rectangular cinema screens. Television screens on the other hand were small and square. And at the start of the 1950s, many households still only had black and white televisions. This was perfect for limited animation, masking the reduction in animation quality. Television ownership grew rapidly through the decade, and producers started investing in cartoons.

youtube

The first animated TV series was Crusader Rabbit (1949), followed by shows more familiar to modern audiences like The Woody Woodpecker Show (1957), Captain Pugwash (1957), Yogi Bear (1958), and a reappearance from Felix the Cat (1958). The first animated show to make it to prime-time was The Flintstones, which ran from 1960 to 1966. These shows were more specifically targeted at children: referred to as cartoons rather than animated television. Created by the most successful cartoon studio of the era – Hanna-Barbera (1957-2001) – The Flintstones was followed by hits like Top Cat (1961), Wacky Races (1968) and Scooby-Doo, Where Are You? (1969).

Animated films, however, were marketed as motion pictures. By the end of the decade, animation studios had started to use xerography animation – first trialled in Sleeping Beauty (1959), then fully used in One Hundred and One Dalmatians (1961). Disney’s Ub Iwerks had adapted the Xerox process, first introduced during WW2, to work on film. This copying technique allowed animator drawings to be printed directly onto cels, massively speeding up the production process. This technique was used throughout the 1960s and 70s and other animation studios adopted the technology.

youtube

New technology also became available to the general public. The commercially successful Super 8 camera launched in 1965, and amateur animators were able to record their own cartoons. This inspired new animation styles, such as brickfilming. Journey to the Moon (1973) was the first recorded of its kind, and paved the way for future animated films like The Lego Movie (2014).

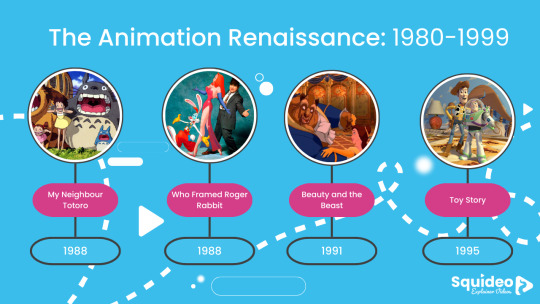

At the start of the 1980s, ‘Saturday morning cartoons’ were flourishing while animated motion pictures were in decline. This was perhaps best exemplified by Disney, who launched Disney Television Animation (1984), while the Walt Disney Animation Studios had its budget slashed. One of its most popular 1980s films, Who Framed Roger Rabbit (1988), was created by an animation department which had just been sent into exile from the main studio lot.

Likewise, the other Big Five production companies started focusing on television animation. Paramount Studios created Nickelodeon (1977) and Warner Brothers Cartoons shifted to create television content. This unit would later become Cartoon Network Studios (1994). The biggest television cartoon to emerge from this period is The Simpsons, which first aired in 1987 on The Tracey Ullman Show, and is one of Fox Broadcasting Company’s biggest assets.

This did leave space for overseas animation companies, most notably the Japanese Studio Ghibli, to find the spotlight with English-speaking audiences. Castle in the Sky (1986) and My Neighbour Totoro (1988) were both critically acclaimed. Likewise, Aardman Animation – the British claymation studio – rose to prominence with its work on the Peter Gabriel Sledgehammer (1986) music video which paved the way for its Creature Comforts and Wallace and Gromit series in the 1990s. Universal Pictures also launched DreamWork Pictures in 1994, releasing its first film Antz in 1998, and would become a big player in the 2000s.

youtube

Arguably the most successful studio to emerge was a small computer division originally created by Lucasfilm in 1979. Pixar pioneered 3D computer animation which they first publicly debuted in The Adventures of André & Wally B (1984). They would go on to make the first 3D computer animation feature film, Toy Story (1995), with Disney – although they were beaten in television by Canadian studio Mainframe Entertainment’s ReBoot (1994).

Disney was already developing digital production techniques such as its Animation Photo Transfer (APT) process was first used in Black Cauldron (1985). Their partnership with Pixar, formalised in 1991, massively improved this digitalisation; most notably with CAPS. First used in The Rescuers Down Under (1990), the Computer Animation Production System provided a host of new digital tools to animators, and kickstarted the Disney Renaissance.

This produced massive hits, not just for Disney but also breaking global box office records. The success of their films, especially The Lion King (1994) prompted their rivals to revive their own animated feature film projects. Other animated feature hits of the 1990s included Space Jam (1996), Anastasia (1997), Antz (1998), The Rugrats Movie (1998) and The Iron Giant (1999).

youtube

The highest-grossing hits of the 1990s belonged to Disney and Pixar with the top five films being The Lion King (1994), Aladdin (1992), Toy Story 2 (1999), Tarzan (1999) and Beauty and the Beast (1991). The latter film also became the first animated film to be nominated for the Academy Award for Best Picture.

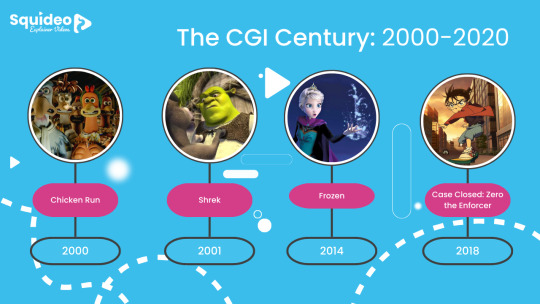

Alongside 3D computer animation, CGI (computer-generated imagery) was growing in popularity for live-action films. First appearing in Westworld (1973), it opened the door for creators. In 1999, the latest CGI trend – motion capture animation – was used to add the first fully animated character into a live-action picture. While Jar Jar Binks wasn’t the biggest hit, Star Wars: The Phantom Menace (1999) proved to be a turning point for computer animation as the new century began.

CGI and 3D computer animation has permanently changed animation. Few films over the past twenty years were created using the traditional hand-drawn 2D animation process, although they still proved popular with audiences. This included the French film Les Triplettes de Bellville (2003), Spain’s Klaus (2019), Japan’s Ponyo (2008) and America’s The Simpsons Movie (2007). All of these films still use digital animation tools to streamline production and minimise costs.

What these changes mean, however, is that animation is no longer ruled by the largest corporations with the largest animation departments. Small teams of animators can create quality feature films using the available technology, and this has propelled the growth of small production studios. The introduction of streaming platforms has also widened the viewership for international animation.

Japanese animation, particularly in the anime style, has benefited from this. While Japanese studios gained a foothold with western audiences in the late 1980s, it has recently catapulted in popularity. Netflix reported that 50 percent more households around the world watched at least one anime title during the first nine months of 2020 compared to the whole of 2019. Studio Ghibli remains the most successful export, continuing its success with Spirited Away (2001), Howl’s Moving Castle (2004) and The Tale of Princess Kaguya (2013) to name a few. More studios are joining their ranks, such as the record-breaking MAPPA, WIT Studio, Madhouse and CoMix Wave Films.

youtube

Other non-American studios that are benefiting from the decentralisation of the animation industry include Aardman Animation, Les Armateurs, BreakThru Films, The SPA Studios and Cartoon Saloon. American animators have also broken away from the studio system. LAIKA was created following the success of A Nightmare Before Christmas (1993), this studio has since released Coraline (2009) which is America’s highest-grossing stop-motion film.

Many of these films are still distributed through large American companies or made in partnership with them. Illumination Studios, the makers of Despicable Me (2010) and The Grinch (2018), was incorporated into a Universal Pictures division almost as soon as it was founded. And Aardman Animation’s stop-motion feature film Chicken Run (2000) was made with DreamWorks Animation, a unit of Universal Pictures.

Since its first film in 1998, DreamWorks has gone on to create two of the most profitable animated franchises: Shrek and Madagascar. Shrek (2001) helped define the future of DreamWorks and its aim to become the antithesis of Disney – an interesting goal considering it was co-founded by a former Disney chairman, Jeffrey Katzenberg, and Disney collaborator, Stephen Spielberg. Shrek modelled its characters after their celebrity voiceover artists; it ditched original scoring for pop songs; and it leant into juvenile humour.

youtube

Disney – which purchased Pixar Animation Studios in 2006 – continued to make 2D style animation at the beginning of the 2000s. With the rising success of other 3D animation features like Toy Story and Shrek however, this was phased out. Disney’s last 2D animated feature film to date was Winnie-the-Pooh (2011), and its last 2D Disney Princess was Tiana in Princess and the Frog (2009).

Their biggest hits were Pixar productions – Finding Nemo (2003), Up (2009), The Incredibles (2004), Ratatouille (2007), Monsters, Inc. (2001), WALL-E (2008) and Cars (2006) – until Frozen (2013) returned them to the top. The top three highest-grossing animated films of the 2010s belonged to Disney.

Disney hasn’t ruled out a return to 2D animated features and, for its 100th anniversary celebrations, has created new 2D animated shorts which resurrect original characters like Oswald the Lucky Rabbit.

As one of the oldest animation studios in existence, it feels natural to look to Disney for an indication where the industry is heading in the 2020s. But as the past thirty years have proved, the industry has become a more even playing field where anyone can succeed.

Work With Us

Ready to create an animated video of your own? Watch the video below to get a better understanding of how Squideo can help promote your business, then get in touch with us to find out more!

youtube

#animation history#lost films#fantasmagorie#gertie the dinosaur#rotoscope#koko the clown#the sinking of the lusitania#cel animation#rubber hose#rubber hose animation#felix the cat#claymation#long live the bull#the adventures of prince achmed#multiplane camera#snow white and the seven dwarfs#steamboat willie#mickey mouse#technicolor#flowers and trees#merrie melodies#limited animation#cinemascope#the flintstones#xerography#super 8 camera#brickfilm#who framed roger rabbit#studio ghibli#aardman animations

1 note

·

View note

Text

Things that existed: 1890′s-1914 (For fanfics, hc or rp!)

For me to reblog in the future with more. Notes: I did not include most of the cigarettes, guns and alcohol. These are mostly American brands or international brands in the U.S at the time. Lots of wars, psychological studies, economic recessions, inventions, and media published in this time. This is obviously not an exhaustive list. Spans from a bit before canon to RDR 1′s epilogue Pre 1890′s: (Just for fun) 1883: The Monopolist (Yes, an early rendition of the board game) The game of Logic, Oscar Mayer, Pinocchio, Long John Silvers,

1884: First modern Cash Register (Imagine the gang trying to figure out how to open one of these)

1885: Dr. Pepper (the soda), first automobile

1886: Heinz Beans, Coco-Cola, Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr, Hyde by Robert Louis Stevenson

1887: Sherlock Holmes Book 1 by Arthur Conan Doyle

1888: Vending Machine, Drinking Straw, Four Roses (Bourbon Whiskey) Kessler Whiskey, Seltzer's for upset stomach/heartburn, Mum’s Deodorant, Hunts (the brand)

1889: Lysol 1890′s: 1890: The Picture of Dorian Gray By Oscar Wilde, Prom (The event for teens) Matryoshka doll, The Edison Talking Doll (Yes, those creepy ass ones), Lipton Tea, Vicks, Marston’s Brewery,

1891: Basketball, Rayon, Fig Newtons, Swiss Army Knife, Hormel,

1892: The second bicycle boom, the “modern” clothes washer, Maxwell Coffee House, Ithaca Kitty - an early paper doll, later stuffed toy?

1893: Cream of Wheat, Juicy Fruit Gum, Johnson’s Baby, Good and Plenty, Wrigley’s Gum, popcorn maker, toaster, Diesel Engine, moving walkways, meth, Ferris wheel, The Jungle Book by Rudyard Kipling, Sunkist Co,

1894:Corn flakes, Phonograph, Silent Films, different fonts for typewriters? Hydrogen Peroxide (The fizzy stuff that burns like hell), lobster thermidor, mousetraps, Purina animal feed,

1895:Rugby leagues, Volleyball, Budweiser, T. Martzetii Dips, Whittaker’s Chocolate, X-rays, 1896: Cracker Jacks, Movie theaters, Frank Merriwell’s Books (A children’s series), Del Monte canning

1897: Jell-O, Cotton Candy, Grape-Nuts (cereal), mufflers, vasectomies, Smucker’s (jelly company), Dracula by Bram Stoker, 1898: Pepsi, Palmolive (Brand), steering wheel, heroin, Walker’s Shortbread, Nabisco, War of the Worlds by H.G. Welles,

1899: Martha white (food), Pall mall cigarettes', Wesson cooking oil, Lux soap, flashlights, revolving doors, first early telephone 1900′s: 1900: Wizard of Oz Book 1 released by L. Frank Baum, Chiclets, Hershey Bars, Kodak cameras, Triskets, escalators, 1901: Disposable Safety Razor, Sweethearts (The candy) the Scholastic Altitude Testing (Standardized Testing that American high schoolers take. Jack would have to take one, I think.) Necco’s candy, The Tale of Peter Rabbit by Beatrix Potter (All of her books then) 1902: Neon Lamps, Teddy Bear, periscope, air conditioning, polygraph tests, Peter Pan, The Virginian by Owen Wister - A western novel

1903: Kraft Food’s Company, Crayons

1904: Banana Split, tea bags, Ovaltine, Canada Dry, French’s (The brand), K-Y Jelly, Discoll’s Berries, 1905: Cadbury Dairy Milk, Hebrew National Brand, popsicles, RC Cola, Planters brand, Kellogg’s Brand, Arsène Lupin by Maurice Leblanc (Stories about a master thief) 1907: Gumball machine, rear-view mirrors, tootsie rolls, Hershey's kisses, 1908: Coffee filters, Ford Motel T engine, Hydrox cookies (Oreo’s lemony older brother), Milk-bone the biscuit (For Rufus), Anne of Green Gables, by L. M. Montgomery, Mr. Toad - the kid’s character, 1909: More modern lightbulbs, Pearson’s candy company, Tillamook Creamery, Phantom of the Opera by Gaston Leroux 1910: instant coffee, milkshake machines, 1911: Wall plugs, Nivea products, Midol (pain reliever), Crush Soda, Crisco, processed cheese, Mars brand, 1912: Edison Disc Record, Goo Goo Clusters, Oreos, LifeSavers candy, Lorna Doone Cookies, Tarzan by Edgar Rice Burroughs 1913: Zippers, Crossword Puzzles, Camel Cigarettes, Hellman’s Food company,

1914: Traffic Cone, Gasmask, Tinker Toys, Listerine, Salad Cream, Heath Bar, Mary Jane Candies, Grapico Soda, Turkish Delight, Mother’s Cookies (The rainbow animal cookies with sprinkles), Chicken of the Sea, TastyKake,

Bonus: Modern Slang they would know. Sorry for the tags, but I worked hard on this and I want it to go out. Edit: Wow, thanks, guys! I didn’t expect this to gain traction. At all. Anyway, I’m a historian so feel free to send me asks about stuff like this! I will probably edit it for medical stuff.

#rdr 2#charles smith#arthur morgan#hosea matthews#dutch van der linde#van der linde gang#john marston#javier escuella#red dead redemption 2#sadie adler#sean macguire#jack marston#abigail marston

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

Titanic was a little bitch movie star who died tragically young in spectacular fashion. We know. Is nobody going to talk about her older sisters who both had incredibly successful careers? They fought in the war!

Britanic deserved a Medal of Honor, acting as a hospital vessel until a mine sank her in Greece. (Side note, sank in a tenth of the time Big T did, and 97% of the victims survived 🙄). She never got into the entertainment biz. She wanted to be a nurse, and she was a damn good one.

Olympic stepped on people and they liked it. She tore a U-boat in half (also a friendly boat but they had it coming), and served as troop transport until the war ended. They called her “Old Reliable”. Here that Unsinkable? They called her reliable. She was in service two years before the Titanic was born, and she was still serving two decades after the Titanic sank. The Olympic retired during the Great Depression, for which the Axis are eternally grateful.

And then the Nasties made The Titanic(1943) as anti-capitalist propaganda, But it ended up banned because of the uncomfortable parallels with a special kind of camping

Anyway, one of the titanic’s fuel depots was on fire for most of the trip, which resulted in the ship leaning slightly. Fortunately, the side with a hole in it was the opposite side, so it balanced back out for a while.

#titanic#britanic#Olympic#white star line#died young#real heroes#drama queen#sinkable#veteran appreciation#did you know?#Germany made two other Titanic films#including a silent film in like 1912#just 2 years after she sank#I know nothing about the other one#they probably made more#everyone seems to do it.#movie making rite of passage#I don’t know.#my hyperfixations and history classes both end well before I was born.#which is a damn shame#knowing about what goes on around me#instead of what happened a hundred years ago#sounds super useful

1 note

·

View note

Text

youtube

If the ending described in this video really is the ending of the new Snow White, then it sounds like it borrows freely from other, non-Disney adaptations of the tale!

The idea of Snow White's friends and allies storming the castle to avenge her death and overthrow the Queen dates back to the 1912 stage play and its 1916 silent film adaptation, which inspired Walt Disney to adapt the tale in the first place!

Those versions also have the mirror shatter and the Queen lose her beauty as a result, and has Snow White become queen in the end. (Though the evil Queen doesn't die, she just goes into exile.)

Many other versions also have the mirror shatter and its magic backfire on the Queen in the end. Including one that has her rapidly age and turn to dust: the 1987 Cannon Movie Tales version.

Snow White and the Huntsman and the German TV adaptation Snow White and the Magic of the Dwarfs also have the Queen's castle be stormed by Snow White's allies at the climax (although in those versions the sieges take place after Snow White revives and Snow White herself leads them), and both of those versions, as well as the German Sechs auf einen Streich adaptation and the cheesy 2012 TV movie Grimm's Snow White, all have Snow White become queen in the end too.

I'm glad I've seen so many Snow White adaptations, so I can trace all these ideas back to their sources.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Monseigneur Myriel speaks of Les Misérables (1912, 1934)

What I learned from this is that Colm Wilkinson is not the first Valjean to later play Myriel in a film adaptation...Henry Krauss played Valjean in Capellani’s 1912 adaptation and then played Myriel in Bernard’s 1934 adaptation. This article is mostly him listing the actors in the two but it was still fun to read and includes some cute anecdotes...notably I thought it was interesting that in 1933 he was also playing Valjean in a stage adaptation and that people were excited for the play because they were looking forward to the movie. Also was happy to see Jean Toulout’s name pop up (1925 Javert) to find out that he was still playing Javert 9 years later.

[Source: L’Image, 1933]

Mme Charlotte Barbier-Krauss, the devoted housekeeper of M. Madeleine-Harry Baur, takes pity upon seeing my disappointment.

“My husbands is at the clinic, Madame, but he is already recovering. He will gladly receive you and I am certain that he will take great pleasure in speaking to you about Les Misérables…it will distract him…”

All the same, it was not without scruples that I had arrived at the rue de Texel, at the Léopold Bellan foundation. I was going to bother an invalid in order to hear the memories of he who played Jean Valjean in 1912, in the original silent film version, and 20 years later, played Bishop Myriel, under the direction of Raymond Bernard…

As soon as I entered into the well lit little bedroom, I felt all my apprehensions melt away. Rosy skinned and smiling, sitting with an open book, it was truly a man on the mend who greeted me. His quilted collar and white knit vest lent more color to his face than the threadbare cassock of the Bishop of Digne. But his good grace, his soft voice, his measured gestures, Henry Krauss certainly had no problem lending them to the character: it comes naturally to him.

And his white hair still flows like a wave- just like when it was still brown and I was a very young girl- and which moved the hearts of all the women of Brussels.

“Ah! Monsieur,” I say, “From nights spent watching Le Bossu or l’Alhambra!...and la Reine Margot!...all of Brussels was at your feet!...though I must admit to you that my heart wasn’t beating for you…It oscillated between your brother Charles Krauss and the romantic Henry Soyer, both of whom are dead now. I never knew which I preferred, which is to say, as far as sentiments, you didn’t exist to me, though you were the most famous of the group and the idol of my natal city! It would have been more tactful if I didn’t reveal this to you today. Please tell me that you’ll forgive me?”

“I forgive you, my child! You know that Monseigneur Myriel holds no grudges. Take a seat there, the sun setting behind you will provide the most beautiful lighting that a picky camera operator could ask for. When the question of lighting comes to the forefront, when cinema understands light as well as Renoir or like Rembrandt, what beautiful images they’ll show to the masses! But…what exactly is it you want me to talk about?”

“Tell me about yourself, about Les Misérables, and about one in relation to the other.”

“About myself? I was already ill when Raymond Bernard asked me to play the role of Monseigneur Myriel, and to conserve myself a little I would leave the studio as soon as my work finished, and so I would never see the regular screenings. So I have no idea ‘how it’s going’ and I’m sorry for it because I would like to be sure that it’s going well…for I’ve always doubted myself….but it’s too late to change it.”

“How do you feel presently?”

“I am recovering at full speed! And cared for wonderfully, with devotion that I can’t praise enough. I sense that speaking about theater and cinema today will do me a great amount of good!”

“Les Misérables will really have counted for something in your life.”

“Well yes. I was Jean Valjean in the first silent version; It was in the second version that Gabriel Gabrio played the role. I also played, just recently, Jean Valjean at the Ambigu theater. The success seemed unlikely to me, the play was poorly constructed, it wasn’t written very well, we were anticipating the release of the film in autumn, a film that has a thousand advantages that the play has not, in short, I thought that the public would shun us. And well! Not at all, it was me who was wrong! It was a big, a very big success. People were crying over the scene between Jean Valjean and Monseigneur Myriel! The Parisian public has been living for months in the imaginary company of Cosette, M. Madeleine, and Fantine…they are interested in them…Thanks to the film we are speaking of, Victor Hugo’s novel is back in vogue and the play benefited from that!

“That’s what I would have predicted. I believe you reprised the role of Jean Valjean after having played the Bishop of Digne in the studio?”

“Yes and that permitted me to better understand the importance of their encounter, which changed the life of the runaway convict…I believe…it seems to me that I rendered more delicately the interior and definite transformation of my character, which Monseigneur Myriel’s goodness illuminated in his soul.

“In the first film, who played Monseigneur Myriel?”

“A great actor: Léon Bernard. Javert, was played by Eti��vant. That is a role that is lucky: in the latest revival at the Ambigu theater, he was played by my friend Jean Toulout [Javert in the 1925 film], an actor like few others. In Raymond Bernard’s film, he is played by Charles Vanel, who’s talent I don’t have to extol to you. By the way, this role suits him wonderfully, because too many people forget that while Javert is a brutal and perhaps heavy handed incarnation, he is also profoundly sincere and guided by conscience. Is there anyone more conscientious than Charles Yanel?

Thénardier was first played by Millot [Émile Mylo]; today he’s played by Charles Dullin; I did not have the chance to meet him at the Joiville studio, but I acted with him in the Brother Karmazoff; I know what a powerful hand he shapes his characters with. We can be sure that his Thénardier will be a striking figure, just like the Madame Thénardier of Marguerite Moreno will be. No actor is able, more so than she is, to renew herself, to transform herself. Yesterday she was the ideal interpreter of poets, a muse with an exquisite voice. Today she is a lucid fantasy, always appearing teasing and measured.

In 1912, in Paul Capellani’s film, Gillenormand was played by Lerand, who was a good strong actor. Today he’s played by Max Dearly, for whom there is no role not made to his size. Big roles, he’s big enough for them. Small roles, he is at ease in them too.

Enjolras was played by Jean Angelo…who later made so many hearts flutter…today he’s played by Vidalin, of la Comedie-Francaise. When I was in charge of certain scenes, along with Abel Gance, in his film Napoleon, I chose Vidalin to play Camille Desmoulins, that shows the high regard I hold. The poor and charming Francine Mussey played Lucie Desmoulins.

Marius, that’s Jean Servais, who proved himself in Brussels and in Paris in the Compagnie du Marais and who has a spirited and charming youthfulness. The first Marius was Gabriel de Gravone…He had big black eyes, an olive complexion, and curly hair… after the matinees at the Park Theater in Brussels, this was around 1908, all the young girls held out pens and postcards to the youth. And he would sign them….he was more intimidated than they were!

And Jean Valjean, that was me. Today he’s played by my good friend Harry Baur…A man of good taste, culture, intelligence, to him art is second nature and he is incapable of uttering a false note…”

“Would you like to speak of any of the other women, apart from Moreno-Thénardier?”

“Why yes! I will first off tell you what a joy it was for me to have as my ‘sister,’ my exquisite friend Marthe Mellot, who we don’t see enough of. She also acted with me in Brussels in a play by Paul Spaak that was very successful. She’s a charming woman with a lot of talent. I know that it’s just a little role, she is not on screen long, but it’s an important time because of the influence it has on the whole life of Jean Valjean.”

“I know that the role of passer-by, a small part in its length but extremely important because of the influence it had on the whole life of Jean Valjean, is held by Blanche Denège, who I saw many times backstage when she was acting in La Fleur des Pois [this one is kind of a mystery to me, I can’t find her connection to Les Miserables. My only guess is that she was uncredited in the role of Baptistine in the 1912 adaptation? But she seems too young.]

Florelle, who I acted with in Berlin, will be a very touching Fantine; it was Ventura who played the role in 1912. I never had the occasion to works with Orane Demazis, but like you I have applauded her on the stage and on the screen and I think that she will give a strong performance in the many complex faces of Eponine. Do you know who played the first Eponine on film, if I dare to say it?”

“I have no idea.”

“Mistinguett. She was quite simply stunning, and never has anyone deserved success as much as she does! To tell the truth, she took us all by surprise with her moving power, with…I don’t know…it is inexpressible yet very expressive.

Josseline Gael is a new comer but has already shown her potential, notably under the direction of Jacques Tourneur in Tout ça ne vaut pas l’amour.

And the young Gaby Triquet already has a well established reputation. I wish her much luck as the young Cosette, like the success which once welcomed the young Maria Fromet, who is today a performer at the Theater du Gymnase.

“And what of Gavroche?”

“Gavroche, that role is gold! The sparrow in the city! I will let myself say that Emile Genevois is an enchanting example of that formidable and charming creature.”

The sun had moved from my left shoulder to my right, the “beautiful light of the setting sun” had faded and a nurse appeared armed with a thermometer but smiling nonetheless and I took my leave of the ensemble of Karainozoff, Lagardere…and Monseigneur Myriel, taking with me the joy of having brought back old memories from one of our most brilliant actors.

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hans Walter Conrad Veidt (22 January 1893 – 3 April 1943) was a German actor best remembered for his roles in the films Different from the Others (1919), The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920), and The Man Who Laughs (1928). After a successful career in German silent films, where he was one of the best-paid stars of UFA, he and his new Jewish wife Ilona Prager were forced to leave Germany in 1933 after the Nazis came to power. The couple settled in Britain, where he took British citizenship in 1939. He appeared in many British films, including The Thief of Bagdad (1940), before emigrating to the United States around 1941, which led to his being cast as Major Strasser in Casablanca (1942).

Hans Walter Conrad Veidt was born in his parents' home at Tieckstraße 39 in Berlin to Amalie Marie (née Gohtz) and Philipp Heinrich Veidt, a former military man turned civil servant. Veidt would later recall, “Like many fathers, he was affectionately autocratic in his home life, strict, idealistic. He was almost fanatically conservative.” By contrast, Amalie was sensitive and nurturing. Veidt was nicknamed 'Connie' by his family and friends. His family was Lutheran, and Veidt was confirmed in a ceremony at the Protestant Evangelical Church in Alt-Schöneberg, Berlin on 5 March 1908. Veidt's only sibling, an older brother named Karl, died in 1900 of scarlet fever at the age of 9. The family spent their summers in Potsdam.

Two years after Karl's death, Veidt's father fell ill and required heart surgery. Knowing that the family could not afford to pay the lofty fee that accompanied the surgery, the doctor charged only what the family could comfortably pay. Impressed by the surgeon's skill and kindness, Veidt vowed to "model my life on the man that saved my father's life" and he wished to become a surgeon. His hopes for a medical career were thwarted, though, when in 1912 he graduated without a diploma and ranked 13th out of 13 pupils and became discouraged over the amount of study necessary for him to qualify for medical school.

A new career path for Veidt opened up in 1911 during a school Christmas play in which he delivered a long prologue before the curtain rose. The play was badly received, and the audience was heard to mutter, "Too bad the others didn't do as well as Veidt." Veidt began to study all of the actors he could and wanted to pursue a career in acting, much to the disappointment of his father, who called actors 'gypsys' and 'outcasts'.

With the money he raised from odd jobs and the allowance his mother gave him, Veidt began attending Berlin's many theaters. He loitered outside of the Deutsches Theater after every performance, waiting for the actors and hoping to be mistaken for one. In the late summer of 1912 he met a theater porter who introduced him to actor Albert Blumenreich, who agreed to give Veidt acting lessons for six marks. He took ten lessons from him before auditioning for Max Reinhardt, reciting Goethe's Faust. During Veidt's audition, Reinhardt looked out of the window the entire time. He offered Veidt a contract as an extra for one season's work, from September 1913 to August 1914 with a pay of 50 marks a month. During this time, he played bit parts as spear carriers and soldiers. His mother attended almost every performance. His contract with the Deutsches Theater was renewed for a second season, but by this time World War I had begun, and on 28 December 1914, Veidt enlisted in the army.

In 1915, he was sent to the Eastern Front as a non-commissioned officer and took part in the Battle of Warsaw. He contracted jaundice and pneumonia, and had to be evacuated to a hospital on the Baltic Sea. While recuperating, he received a letter from his girlfriend Lucie Mannheim, telling him that she had found work at the Front Theatre in Libau. Intrigued, Veidt applied for the theatre as well. As his condition had not improved, the army allowed him to join the theatre so that he could entertain the troops. While performing at the theatre, his relationship with Mannheim ended. In late 1916, he was re-examined by the Army and deemed unfit for service; he was given a full discharge on 10 January 1917. Veidt returned to Berlin where he was readmitted to the Deutsches Theater. There, he played a small part as a priest that got him his first rave review, the reviewer hoping that "God would keep Veidt from the films." or "God save him from the cinema!"

From 1917 until his death, Veidt appeared in more than 100 films. One of his earliest performances was as the murderous somnambulist Cesare in director Robert Wiene's The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920), a classic of German Expressionist cinema, with Werner Krauss and Lil Dagover. His starring role in The Man Who Laughs (1928), as a disfigured circus performer whose face is cut into a permanent grin, provided the (visual) inspiration for the Batman villain the Joker. Veidt starred in other silent horror films such as The Hands of Orlac (1924), also directed by Robert Wiene, The Student of Prague (1926) and Waxworks (1924), in which he played Ivan the Terrible. Veidt also appeared in Magnus Hirschfeld's film Anders als die Andern (Different from the Others, 1919), one of the earliest films to sympathetically portray homosexuality, although the characters in it do not end up happily. He had a leading role in Germany's first talking picture, Das Land ohne Frauen (Land Without Women, 1929).

He moved to Hollywood in the late 1920s and made a few films there, but the advent of talking pictures and his difficulty with speaking English led him to return to Germany. During this period, he lent his expertise to tutoring aspiring performers, one of whom was the later American character actress Lisa Golm.

Veidt fervently opposed the Nazi regime and later donated a major portion of his personal fortune to Britain to assist in the war effort. Soon after the Nazi Party took power in Germany, by March 1933, Joseph Goebbels was purging the film industry of anti-Nazi sympathizers and Jews, and so in April 1933, a week after Veidt's marriage to Ilona Prager, a Jewish woman, the couple emigrated to Britain before any action could be taken against either of them.

Goebbels had imposed a "racial questionnaire" in which everyone employed in the German film industry had to declare their "race" to continue to work. When Veidt was filling in the questionnaire, he answered the question about what his Rasse (race) was by writing that he was a Jude (Jew). Veidt was not Jewish, but his wife was Jewish, and Veidt would not renounce the woman he loved. Additionally, Veidt, who was opposed to antisemitism, wanted to show solidarity with the German Jewish community, who were in the process of being stripped of their rights as German citizens in the spring of 1933. As one of Germany's most prominent actors, Veidt had been informed that if he were prepared to divorce his wife and declare his support for the new regime, he could continue to act in Germany. Several other leading actors who had been opposed to the Nazis before 1933 switched allegiances. In answering the questionnaire by stating he was a Jew, Veidt rendered himself unemployable in Germany, but stated this sacrifice was worth it as there was nothing in the world that would compel him to break with his wife. Upon hearing about what Veidt had done, Goebbels remarked that he would never act in Germany again.

After arriving in Britain, Veidt perfected his English and starred in the title roles of the original anti-Nazi versions of The Wandering Jew (1933) and Jew Süss (1934), the latter film was directed by the exiled German-born director Lothar Mendes and produced by Michael Balcon for Gaumont-British. He naturalised as a British subject on 25 February 1939. By this point multi-lingual, Veidt made films both in French with expatriate French directors and in English, including three of his best-known roles for British director Michael Powell in The Spy in Black (1939), Contraband (1940) and The Thief of Bagdad (1940).

By 1941, he and Ilona had settled in Hollywood to assist in the British effort in making American films that might persuade the then-neutral and still isolationist US to join the war against the Nazis, who at that time controlled all of continental Europe and were bombing the United Kingdom. Before leaving the United Kingdom, Veidt gave his life savings to the British government to help finance the war effort. Realizing that Hollywood would most likely typecast him in Nazi roles, he had his contract mandate that they must always be villains.

He starred in a few films, such as George Cukor's A Woman's Face (1941) where he received billing under Joan Crawford's and Nazi Agent (1942), in which he had a dual role as both an aristocratic German Nazi spy and the man's twin brother, an anti-Nazi American. His best-known Hollywood role was as the sinister Major Heinrich Strasser in Casablanca (1942), a film which began pre-production before the United States entered World War II. Commenting about this well-received role, Veidt noted that it was an ironical twist of that that he was praised "for portraying the kind of character who had forced him to leave his homeland".

Veidt enjoyed sports, gardening, swimming, golfing, classical music, and reading fiction and nonfiction (including occultism; Veidt once considered himself a powerful medium). He was afraid of heights and flying, and disliked interviews and wearing ties.

In a September 1941 interview with Silver Screen, Veidt said,

I see a man who was once for years studying occult things. The science of occult things. I had the feeling there must be – something else. There are things in our world we cannot trace. I wanted to trace them. The power we have to think, to move, to speak, to feel – is it electricity, I wanted to know? Is it magnetism? Is it the heart? Is it the blood? When the body dies, where is all that? Where is the power that made the body live? No one can tell me it is not somewhere. If you believe in waves, which you must believe after you have the radio, why couldn't human beings contact the wave lengths of someone who is dead? ... this is the kind of thing with which I was, for many years, preoccupied. This is what I tried to find, the answer. I did not find it. But in looking for it there was etched, perhaps, on my face, some hint of the strange cabals I kept with unseen and unknown powers. I did not find it, I say. But I found something else. Something better. I found –faith. I found the ability, very peaceful, to accept that which I could neither see, nor hear nor touch. I am a religious man. My belief is that if we could help to make all people a little more religious, we would do a great lot. If we would pray more ... we forget to pray except when we are in a mess. That is too bad. I believe in prayer. Because when we pray, we always pray for something good.

He went on:

I must tell you something that will disappoint you ... far from being one engaged in strangle rituals of thought or action, what I like best to do is sit in this small garden, on this terrace, and – just sit. Sometimes, I confess, I think a lot; about my past. About my parents who are dead. I like to dream, to go away ... At other times, I sit and read. I read, often, a whole day through. I play golf. I used to be a golf fiend. Now I am not a fiend even on the links. Now I play because it is relaxation. I like the beach very much, the sea. I go to the films often, to the neighborhood theater, my wife and I. Sometimes we go to the Palladium, where there is dancing. It is an amazing sight to me to see young people, how they are like they were thirty years ago, how they hold hands, how they enjoy their lives. To me, the most beautiful thing in California is the Hollywood Bowl, the Concerts Under the Stars. For me, it is a terrific experience. I have never seen an audience in my life like that. 30,000 people, simple people, most of them, listening to music under the stars. I have never seen 30,000 people, simple people, so quiet. I like to think of them as a symbol that one day there may be that oneness for all mankind....

On 18 June 1918, Veidt married Gussy Holl, a cabaret entertainer. They had first met at a party in March 1918, and Conrad described her to friends as "very lovely, tall, dignified and somewhat aloof". They separated in 1919 but attempted to reconcile multiple times. Holl and Veidt divorced in 1922.

Veidt said of Holl, "She was as perfect as any wife could be. But I had not learnt how to be a proper husband." and, "I was elated by my success in my work, but shattered over my mother's death, and miserable about the way my marriage seemed to be foundering. And one day when my wife was away, I walked out of the house, and out of her life, trying to escape from something I could put no name to."

After his separation and eventual divorce from Holl, Veidt allegedly dated his co-star Anita Berber.