Text

From Fun (1879):

ROYALTY Miss Kate Santley begins the season with a new comedy by Palgrave Simpson Little Cinderella The plot of the old story is made to fit to 19th century incidents The Cinderella of the piece named Lottie is admirably played by Miss Santley the next most interesting character is Old Foxglove the gardener Of course Lottie gains the hand of the modern Prince to the discomfiture of her ill natured sisters The piece is followed by Tita in Thibet a comic opera in which Miss Santley sustains the principal character with her usual vivacity and is well supported by C Groves F Leslie and the other members of the company Altogether there is a capital evening's entertainment at this pretty little theatre.

From Musical Standard (1883):

COMIC OPERA AT THE ROYALTY THEATRE Miss Kate Santley opened this pretty theatre on Monday with M Audran's comic opera operetta entitled Gillette adapted from the French by a very clever litterateur Mr H Savile Clarke The story is a very awkward affair in the original if that word may be used when the delicate incidents are con verted from one of Boccaccio's moral tales I have read whole of the Decamerone in choice Italian Mr Clarke however has extracted the poison and left some of honey his libretto might perhaps be smarter and more flavoured with modern wit but it is generally approved as work of an experienced and accomplished dramatic writer The music of M Audran composer of that peculiar piece called La Mascotte must be dismissed as poor trivial and common place An ironical critic predicted a run 100 nights when I accosted him in the lobby on Monday persons in England cherish a notion that musical men care only for something deep and as once said of an erudite critic that they breakfast on a fugue of Bach's take luncheon properly Nuncheon with a Lied ohne worte and appease their hunger at or after dinner with two symphonies and a concerto Silly folks are these to be answered by Solomon according to their folly All good music of whatever kind will command respect and admiration I lately lauded the arrangement at St James's Hall for a provision of elegant overtures and pretty valses during the trying hour of heavy dinners But M Audran in this case only offers an effervescent beverage that tastes sweet to evaporate with a hint at dyspepsia The tunes certainly take the ear but always tell the same old story The scoring for the band would hardly satisfy a disciple of Wagner but here I pause in awe One learned judge with whom I agree pronounces the orchestration to be of an elementary kind Another who writes to the effect that Audran has written invitâ minervá and repeated himself proceeds to say that the airs are set off orchestration such as in the amateur's opinion make up for many shortcomings elsewhere Most of the choruses are unison and the two part writing would be torn to pieces at the Royal Academy if presented in the form of exercises finale of Act II a soldier's chorus is thought to be the best specimen of the music Les Pommes d Or and Mr Slaughter contributes a capital chorus in Act III The air of Tarantelle danced in rather original style by Miss A Wilson is ascribed to Mr Hamilton Clarke The principal parts of operetta are allotted to Miss Kate Santley Miss Kate Monroe Mr Walter Browne and F Kaye Miss M Taylor and Mr WJ Hill A dreadful and most unmeaning bore a ChiefPolice is cruelly thrust upon the audience His nonsensical talk about the majesty of the law reminds me of the old parish beadle at the Surrey Theatre under the Davidge dynasty who in April 1841 ranted about offences against the authorities The verdict of the audience on this operetta can hardly be called a favourable one but this is not the fault of Mr Savile Clarke.

From THE ACADEMY. A WEEKLY REVIEW OF LITERATURE, SCIENCE, AND ART. (1877):

A TRIFLING dramatic piece brought out at the Royalty on Saturday night and ominously though politely described by a Sunday contemporary as of judicious brevity is from the pen of Mr Alfred Thompson and is the vehicle for the exhi bition in various guises of Miss Kate Santley The Three Conspirators are only one in reality and his plot is not of a very appalling character It is matter of tradition that some of those most closely connected with the stage from Macready downwards have been the least willing to let their young relations have any asso ciations with it A principal personage in The Three Conspirators is not a Macready at all but an agent and organiser of opéra bouffe possessed of the like ideas His niece would find it im possible to adopt the profession of the theatre did she not with the aiding and abetting of his office clerk assume disguises and so win upon him as a dramatic aspirant of much promise Mr JD Stoyle Mr Beyer and Miss Kate Santley are the performers engaged in this trifle and each does his part well so that none of what little fun and liveliness there are in the piece may be lost and when the curtain falls it is felt that the brevity is beyond denial whether or no it be judicious LADY SEBRIGHT and Mrs Monckton two amateur actresses of note in large private circles appear to day at an amateur performance at the Opéra Comique Theatre.

From The Dart and Midland Figaro (1887):

THEATRE ROYAL The reception accorded Miss Kate Santley when she made her ap pearance on Monday night at this house in Farnie and Audran's comic opera Indiana must have convinced that talented lady of the very favourable regard in which she is held by Birmingham playgoers and helped her to contemplate with equanimity possible prospective adverse criticism There was a capital house and the opera from the com mencement to the finish appeared to give lively satisfaction The plot if not entirely original is at least intelligible the music is tuneful and catchy the dresses rich and tasteful the scenery appropriate and the chorus sprightly and fair to look upon Miss Kate Santley as Indiana Grayfaunt is the life of the piece The part fits her like a glove and her excellent voice stands her in good stead Mr Ashley's Mat o the Mill a not such a fool as he looks sort of individual is a perfect study The other characters are in good hands A feature in the production is the introduction of several grace ful dances in which Miss Alice Lethbridge is seen at her best Next week HB Conway and the English Comedy Company.

From St. Stephen's Review (1886):

Miss Kate Santley whose name is already indissolubly associated with the palmy days of opera bouffe and whose production of the Merry Duchess at the Royalty was one of the successes of the season is about to make a new departure in comic opera The suffrages of provincial audiences are to be asked for Vetah work of which the principal action takes place in India In addition to a corps de ballet which will lend a vivid oriental colour to the second act in A Dream of Fair Women several well known artistes have been engaged including Mr Henry Ashley Miss Edith Bland Mr Robert Courtnedge and Mr L Rignold The dresses are said to be magnificent and Mr Charles Douglas a gentlemen who is himself a traveller of some experience in the East will manage the front of the show At Christmas we may look forward to welcoming back Miss Santley to the merry little house in Dean Street when Vetah will be snbmitted to Metropolitan audiences.

#classical music#opera#music history#bel canto#composer#classical composer#aria#classical studies#maestro#chest voice#Kate Santley#coloratura soprano#soprano#The London Stereoscopic & Photographic Company#actress#comedian#Opera buffa#The London Stereoscopic#Drury Lane Theatre#Opera Comique#W. S. Gilbert#Gilbert and Sullivan#the Lyric Theatre#Apollo Theatre#Golden Age of Opera#classical musician#classical musicians#classical history#history of music#historian of music

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Maria de Macchi - Di quai soavi lacrime [Poliuto] - 1907

From Musical Courier 1909-01-20: Vol 58 Iss 3:

Maria de Macchi, Italy’s most famous dramatic soprano, died at Milan, Italy operation to remove a tumor. It January 13, from the effects of an was known the operation involved danger, but a fatal result was not expected. Her death is not only a blow to her friends and relatives, but a loss to the world of art. Maria de Macchi was forty-one years old. She leaves parents in Milan and a brother in New York City.

Maria de Macchi was engaged by Heinrich Conried early in his régime as the leading dramatic soprano of the Metropolitan Opera Company’s Italian wing. She came with the recommendation of many prominent singers. Her first appearance in New York was to have been made in “Gioconda,” but for a reason not revealed publicly the réle was given to Nordica exclusively. De Macchi sang first in “Lucrezia Borgia,” which, in spite of Caruso’s presence in the cast, was a failure. Her next rodle was Santusza in “Cavalleria Rusticana,” the second offering of a double bill. Only two critics were in the auditorium at the time. The others wrote slightingly of her performance. Her third appearance took place in “Aida” on a Saturday night. Again most of the critics were absent. Maria de Macchi went on tour with the Metropolitan Opera Company. Philip Hale, critic of the Boston Herald, gave high praise to her. Everywhere outside of New York she was received with acclaim. But disappointment at failure in this city was keen. Before she left America the soprano was taken ill, and her condition, with its fatal result, was traced directly to chagrin at the treatment she received here.

For several years Maria de Macchi assisted her brother, Celestino, in the management of his National Opera Company, which gives a season in Rome every Summer. De Macchi, who teaches singing in New York in the Winter, is related by marriage to Carl Schurz, Jr.

#classical music#opera#music history#bel canto#composer#classical composer#aria#classical studies#maestro#chest voice#Maria de Macchi#dramatic soprano#soprano#Golden Age Of Opera#Di quai soavi lacrime#Polito#Gaetano Donizetti#classical musician#classical musicians#classical history#history of music#historian of music#musician#musicians#diva#prima donna#La Scala#teatro alla scala#MET#Metropolitan Opera

1 note

·

View note

Text

Exactly 120 years ago is this castlist from May 2.1905 at the Royal Opera Covent Garden. Wagner's „Die Walküre“ conducted by Hans Richter.

#classical music#opera#music history#bel canto#composer#classical composer#aria#classical studies#maestro#chest voice#royal opera house#Royal Opera#Covent Garden#Die Walküre#Richard Wagner#Golden Age Of Opera#cast#classical musician#classical musicians#classical history#history of music#historian of music#musician#musicians#diva#prima donna

0 notes

Text

Here we see this special Page in the Magazine „Der Merker“ Vienna from 1910 .

#classical music#opera#music history#bel canto#composer#classical composer#aria#classical studies#maestro#chest voice#Magazine#Der Merker#Golden Age Of Opera#classical musician#classical musicians#classical history#history of music#historian of music#musician#musicians#diva#prima donna

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

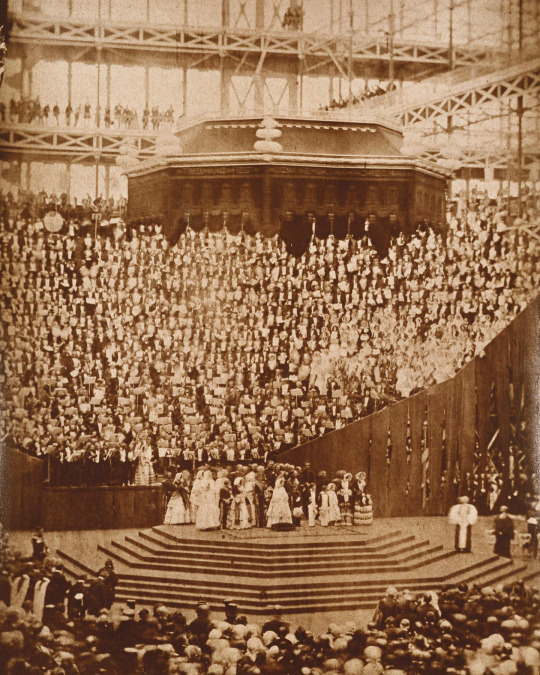

Photograph of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert opening The Crystal Palace in Sydnenham 1854.

After the closure of The Crystal Palace in Hyde Park it was moved to Sydenham and rebuilt in even grander form there between 1852 and 1854, using twice the amount of glass, with barrel-vaulted transepts at both ends of the nave. Situated in landscaped gardens it became one of London’s major tourist attractions until its destruction by fire in 1936.

The opening ceremony on 10th June 1854, featured Michael Costa who conducted a vast orchestra and choir of over 1,700 performers featuring three military bands, the orchestra from Covent Garden Theatre, and a chorus recruited from twenty-one provincial choirs on a 6,000 square foot stage at a 42 degree rake so that they could all see the conductor. The audience of over 30,000 witnessed a magnificent state spectacle.

Queen Victoria and Prince Albert were the guests of honour, and the Queen noted in her journal: ‘I cannot describe the splendid effect of the music, it was beyond all description & most imposing. Clara Novello’s fine voice sounded so well in that large space. Most conspicuous among the singers were good old Lablache, Formes, & Hözel. After the National Anthem was sung the Address was read by the Chairman, describing the origin & objects of the undertaking & I read my answer. Medals & books were presented. When Paxton came up the steps of the dais, he was immensely cheered, but he himself was low & sad, his dear & revered Master, & benefactor, the Duke of Devonshire being had a stroke, & though going on well, is still feeble & confined to bed. We now walked round the whole building, in procession, after which the 100th Psalm was sung, the Archbishop of Canterbury, invoked the Divine Blessing on this great work, & the Hallelujah Chorus was most magnificently sung. Then, Ld Breadalbane announced that the Crystal Palace was opened. This & the singing of the National Anthem concluded the interesting & really imposing ceremony. I fervently hope that so great & noble an undertaking may be crowned with success. There were immense crowds all along the road.’

#classical music#opera#music history#bel canto#composer#classical composer#aria#classical studies#maestro#chest voice#Queen Victoria#Prince Albert#The Crystal Palace#Golden Age Of Opera#Clara Novello#soprano#classical musician#classical musicians#classical history#history of music#historian of music#musician#musicians#diva#prima donna

1 note

·

View note

Text

OTD in Music History: Russian composer, pianist, and mystically-inclined artistic visionary Alexander Scriabin (1872 - 1915) dies from blood poisoning in his Moscow apartment 110 years ago, at the age of 43. A few weeks earlier, Scriabin had begun complaining about the return of a very large and painful pimple on his right upper lip. (He had previously complained about an earlier iteration of this troublesome zit in 1914.) Scriabin’s condition gradually worsened, and about a week before his death he took to bed. Scriabin's doctor later recalled that an uncontrollable blood-borne infection began to spread across his face "like a purple fire,” and as Scriabin’s temperature soared up to 41 °C (106 °F), he grew delirious and eventually began to hallucinate. In those days, before antibiotics, there was little that medicine could offer him… In his early years, the young Scriabin wrote works that were heavily inspired by Frederic Chopin (1810 - 1849). Later on, however, he developed a very personal musical language inspired by his mystical inclinations which pushed tonality almost to the breaking point. Scriabin’s stock plummeted after the tragedy of his early death was further compounded by the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917 – only to rise once again, in the 1960s, when he was rediscovered by a new generation of music lovers who were fascinated by this most “psychedelic” of composers. PICTURED: A (c. 1910s) Russian real photo postcard showing the middle-aged Scriabin.

#classical music#opera#music history#bel canto#composer#classical composer#aria#classical studies#maestro#chest voice#Golden Age Of Opera#classical musician#classical musicians#classical history#history of music#historian of music#musician#musicians#diva#prima donna#Alexander Scriabin

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

It’s 85 years today since the death in Milan of Luisa Tetrazzini

From My life of song by Tetrazzini, Luisa, 1871-1940:

When she sang, he said, she made the people forget everything that was nasty and bad, and think only of the sweet and beautiful. He said that everyone who loved singing dreamed of being like Patti. To have a voice like Patti was to walk about with heaven inside. As he spoke my eyes must have opened very wide, as children’s eyes do when they hear a wonderful story.

When at my kindergarten school I used to improvise music to the words with which I answered my teacher’s questions—sometimes to her great annoyance and my subsequent physical discomfiture; many times have I had my knuckles rapped for singing when I should have been studying. I have sung my way all through life. When trouble and bereavement have clouded my day, I have stilled my aching heart with song. When T have been ill, I have sung on my sick-bed and partially allayed my physical pains thereby. Nothing but the loss of my voice will ever stop me from singing. I think I shall try to sing to my nurse on my dying bed.

There is one little feature of my childhood concerning which members of my family still speak when telling of my love for song. At one period of my life my mother always allotted to me the duty of sweeping and scrubbing all the stairs in our apartment. Sometimes I used to protest, as the task was not the pleasantest of all the household duties. Many other protests of mine to my mother were favourably considered. Not so ‘this one. One day my mother explained the reason why : it was because I had a habit of selecting an act from one of the great operas and singing it through during my work. I used to take the four parts and sing them all—bass, tenor, contralto, and soprano. My mother declared that the time when I was cleaning the stairs was the happiest hour of her day.

As he departs Lakmé gathers the flowers of the deadly stramonium tree, kisses her lover, bids him good-bye, and presses the fatal flower to her lips. Lakmé’s prayer to Durga and the other Brahmin gods for protection for her English lover, and the famous bell song, were heard almost nightly in our home, and I am still singing arias from this great and ever-popular opera to-day. It was Lakmé that I sang in the Royal Albert Hall, London, on October 10, 1920, at a special concert which it was necessary to give to demonstrate to the British public that some reports which had been circulated as to my voice were entirely false. The London public, though they had heard me sing Lakmé, I thought, until they were weary, gave me their accustomed ecstatic welcome. The hall was packed with nearly 18,000 people. All the boxes save one were filled. The next day the newspapers criticized the owner of this box for not lending it to someone in the large crowds who had been turned away. When we left the hall our car was mobbed by enthusiasts who were shouting to me to return soon and sing them Lakmé once: again.

‘‘ You have a good heart, Tetrazzini,’ is a sentence which, occasionally used by some of my acquaintances, has caused me as much secret pleasure as some of the extravagant outbursts of the audiences whom I have pleased with my songs. It has often happened that when I have arrived at the opera in one of the big world-cities, and seen crowds of people in evening dress going away because of the ‘‘ House Full’’ sign, I have sent round to the tail of the gallery queue and asked half a dozen of the music lovers of those less fortunately placed, who it was evident stood a poor chance of obtaining admission, if they would honour Tetrazzini by occupying her own private box for the evening’s performance. I have watched with quiet enjoyment the curious glances directed towards the occupants of my box by some of the bejewelled ladies in the other boxes and stalls. The rough clothes worn by my selected half-dozen, it is true, are usually out of keeping with the elegant side of the house, yet to me it is the one touch of nature which makes the whole world kin. And these usually eager though shabby members of the human race are -generally the best listeners.

I was not in the least nervous. It was not until some time afterwards, when I had left Florence and had begun to make progress in my profession, that I awoke to the seriousness of operatic singing and began to grow really afraid of the limelight, of making false moves, of not doing justice to my natural gifts when facing a great crowd of watching, criticizing fellowcreatures.

Then someone standing near said: ‘‘ Signorina Tetrazzini, when they sing so badly at general rehearsal you can always be sure that the opening performance will go magnificently. It has always been so, and it always will be so. I, Donna Lina Crispi, say so.’? It was the lady autocrat of the opera house who spoke, and so impressed had I been with her knowledge of opera that I felt her prophecy would be fulfilled.

The morning of the opening performance the conductor, the maestro Usiglio, gave me some words of counsel. ‘‘ During the unaccompanied portion of the great sextette you must keep ‘your eye on me, and I will give you the cues,”’ said he. ‘‘ When I hear Selika singing flat I will make a sign for you to sing sharp, and this will pull the others up.’’ On reflection it seems that it was asking a very great deal of a girl of sixteen to make her début in the capital before the Court and to adjust her voice so as to assist others who might drop out of tune.

It was during that performance that I accidentally produced a phenomenal note. Instead of finishing up on E, as I had intended and as the score ordered, I found myself singing a note a full octave higher, the E alt. The note came as clearly as it did unexpectedly. It was heard with general surprise all over the opera house, , and many people who had been turned away, and were listening outside in the hope of hearing some of the higher notes, heard it distinctly and discussed it excitedly. ‘‘ Wherever did you get that note?” I was asked afterwards ; to which I was obliged to answer that I did not know. This answer was absolute truth. I had never tried to get it until then, and did not know I was capable of producing it. When it is achieved it is usually thin or cloudy, but that note came forth as full and round and easy as any of the others. Since then I have touched higher notes without difficulty, but I have never forgotten the surprise I felt when I first produced the E alt. It was this note which caused the mild sensation at my last London recital. I had not intended to try so high a flight during my first song, as it is always well to work gradually up to the mountain peaks. It was my intention to warm up the voice with smaller arias, but the programme was not arranged according to my plan. Before that vast concourse of people I felt slightly nervous at the beginning, and was not fully prepared when the time came to throw out that high note, so I did not attempt it. The audience, however, were very generous with their applause, and it was during the long burst of cheering that I decided to sing the last line over again. I tried the note quietly before I turned to the pianist, and found that it would come quite readily. And so it did. The second outburst of cheering was far greater than the first, and was so genuine that it convinced me that I had done the right thing.

‘* No matter what anyone says, I am now a real prima donna, even though I am only a girl. I have appeared before the Royal Family, I have spoken with the Queen and been praised for my singing by the greatest lady in the land, and the Queen says I am going to have a great career.”’ I danced and laughed and sang for joy during those fleeting early days. I revelled in my life. Everyone was kind to me. Everyone seemed anxious to do what he (or she) could to make my every minute as enjoyable as possible. The world I lived in seemed to be an earthly fairyland. I began to be known in the capital. As I walked about the streets with my friends I would see someone drawing another’s attention to me. ‘‘ There is Signorina Tetrazzini, the youngest prima donna,”’ or ‘‘ She is:our new nightingale. Everybody is going to the opera to hear her,”’ were phrases which I was frequently overhearing in Rome. What young girl is there who would not feel a warm glow of pleasure as she heard people speaking her name and eulogizing her talent as she moved about the capital of her native country? And I must admit that I was very conscious of and gratified at the public interest which my presence in Rome aroused.

When singing, always smile slightly. This slight smile at once relaxes the lips, allowing them free play for the words which they and the tongue must form. It also gives the singer a slight sensation of uplift necessary for singing. It is impossible to sing well when mentally depressed or even physically indisposed. Unless one has complete control over the entire vocal apparatus, and unless one can simulate a smile one does not feel, the voice will lack some of its resonant quality, particularly in the upper notes. Be careful not to simulate too broad a smile. Too wide a smile often accompanies what is called ‘‘ the white voice.”’ This is a voice production where a head resonance alone is employed, without sufficient of the appoggio or enough of the mouth resonance to give the tone a vital quality. This ‘‘ white voice’’ should be thoroughly understood, and is one of the many shades of tone a singer can use at times, just as the impressionist uses various unusual colours to produce certain atmospheric effects.

Another thing the young singer must not forget in making her initial bow before the public is the question of dress. When singing on the platform or stage, dress as well as you can. Whenever you face the public, have at least the assurance that you are looking your very best; that your gowns hang well, fit perfectly, and are of a becoming colour. It is not necessary that they should be gorgeous or expensive, but let them always be suitable; and for big cities let them be just as sumptuous as. you can afford. At morning concerts in New York, velvets and handpainted chiffons are considered good form, while in the afternoon handsome silk or satin frocks of a very light colour are worn with hats. If the singer chooses to wear a hat, let her be sure that its shape will not interfere with her voice. A very large hat, for instance, with a wide brim that comes down over the face, acts as a sort of blanket to the voice, eating up sound and detracting from the beauty of tone, which should go forth into the audience. It is also likely to screen the singer’s features too much and hide her from view of those sitting in the balconies and galleries.

#classical music#opera#music history#bel canto#composer#classical composer#aria#classical studies#maestro#chest voice#Luisa Tetrazzini#the Florentine nightingale#the nightingale#golden age of opera#My life of song#dramatic soprano#dramatic coloratura soprano#coloratura soprano#soprano#Soprano sfogato#Covent Garden#classical musicin#classical musicians#classical history#history of music#historian of music#musician#musicians#diva#The queen of staccato

1 note

·

View note

Text

Take a look on this two pages from 1910 with the Programs for the Concert Season in Vienna.

#classical music#opera#music history#bel canto#composer#classical composer#aria#classical studies#maestro#chest voice#concert season#Concert#Vienna#golden age of opera#classical musician#classical musicians#classical history#history of music#historian of music#musician#musicians#diva#prima donna

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

OTD in Music History: Important opera composer Ruggero Leoncavallo (1857 - 1919) is born in Italy. Leoncavallo was inspired to write his enduring operatic masterpiece “Pagliacci” (1892) in response to the tremendous success of Pietro Mascagni’s (1863 - 1945) “Cavalleria rusticana” (1890), which is often cited as having kicked off the influential “verismo” (or “realistic”) opera movement of the 1890s. "Pagliacci" tells the tale of Canio, the leader of a "commedia dell'arte" theater company who brutally murders his own wife Nedda and her lover Silvio on stage during a performance. In the modern era, "Pagliacci" is often staged alongside "Cavalleria rusticana" as part of a double bill that is colloquially known as "Cav and Pag." (According to Leoncavallo, he actually derived the plot of “Pagliacci” from a real-life murder trial that took place in his hometown and over which his own father, a judge, presided.) The most famous aria from “Pagliacci," “Vesti la giubba” ("Put on the costume"), is one of the most beloved arias in the entire operatic repertoire and the recording of it by celebrated tenor Enrico Caruso (1873 - 1921) is reportedly the first commercial recording to ever sell a million copies (although this is probably a grand total which combines the sales of several different versions that Caruso released in 1902, 1904, and 1907, respectively). In 1907, "Pagliacci" became the first opera to be recorded in its entirety, under Leoncavallo's personal supervision. In 1931, it also became the first complete opera to ever be filmed with sound. In addition to his gifts as a composer, Leoncavallo was also one of the finest librettists of his time, second only to Arrigo Boito (1842 - 1918). Particularly worthy of note on this front is Leoncavallo's contribution to the libretto for one of Giacomo Puccini's (1858 - 1924) earliest hits, “Manon Lescaut” (1893). PICTURED: A real photo postcard featuring a photo portrait of Leoncavallo (c. 1890s).

#classical music#opera#music history#bel canto#composer#classical composer#aria#classical studies#maestro#chest voice#Ruggero Leoncavallo#opera composer#librettist#Pagliacci#La bohème#golden age of opera#classical musician#classical musicians#classical history#history of music#historian of music#musician#musicians#diva#prima donna

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Belgian or French soprano Mariette Mazarin (1874-1953) sang the title rôle in the first American production of Richard Strauss‘ Elektra at the Manhattan Opera in New York on February 1st, 1910. It took more than twenty years till the next production of the one-act piece in New York: On December 3rd in 1932 the German soprano Gertrud Kappel (1884-1971) sang the first Elektra at the MET.

From Interpreters, by Carl Van Vechten:

SOMETIMES the cause of an intense impression in the theatre apparently disappears, leaving "not a rack behind," beyond the trenchant memory of a few precious moments, inclining one to the belief that the whole adventure has been a dream, a particularly vivid dream, and that the characters therein have returned to such places in space as are assigned to dream personages by the makers of men. This reflection comes to me as, sitting before my typewriter, I attempt to recapture the spirit of the performances of Richard Strauss's music drama Elektra at Oscar Hammerstein's Manhattan Opera House in New York. The work remains, if not in the répertoire of any opera house in my vicinity, at least deeply imbedded in my eardrum and, if need be, at any time I can pore again over the score, which is always near at hand. But of the whereabouts of Mariette Mazarin, the remarkable artist who contributed her genius to the interpretation of the crazed Greek princess, I know nothing. As she came to us unheralded, so she went away, after we who had seen her had enshrined her, tardily to be sure, in that small, slow-growing circle of those who have achieved eminence on the lyric stage.

Before the beginning of the opera season of 1909-10, Marietta Mazarin was not even a name in New York. Even during a good part of that season she was recognized only as an able routine singer. She made her début here in Aida and she sang Carmen and Louise without creating a furore, almost, indeed, without arousing attention of any kind, good or bad criticism. Had there been no production of Elektra she would have passed into that long list of forgotten singers who appear here in leading rôles for a few months or a few years and who, when their time is up, vanish, never to be regretted, extolled, or recalled in the memory again. For the disclosure of Mme. Mazarin's true powers an unusual vehicle was required. Elektra gave her her opportunity, and proved her one of the exceptional artists of the stage.

I do not know many of the facts of Mariette Mazarin's career. She studied at the Paris Conservatoire; Leloir, of the Comédie Française, was her professor of acting. She made her début at the Paris Opéra as Aida; later she sang Louise and Carmen at the Opéra-Comique. After that she seems to have been a leading figure at the Théâtre de la Monnaie in Brussels, where she appeared in Alceste, Armide, Iphigénie en Tauride and Iphigénie en Aulide, even Orphée, the great Gluck répertoire. She has also sung Salome, the three Brünnhildes, Elsa in Lohengrin, Elisabeth in Tannhäuser, in Berlioz's Prise de Troie, La Damnation de Faust, Les Huguenots, Grisélidis, Thais, Il Trovatore, Tosca, Manon Lescaut, Cavalleria Rusticana, Hérodiade, Le Cid, and Salammbô. She has been heard at Nice, and probably on many another provincial French stage. At one time she was the wife of Léon Rothier, the French bass, who has been a member of the Metropolitan Opera Company for several seasons.

Away from the theatre I remember her as a tall woman, rather awkward, but quick in gesture. Her hair was dark, and her eyes were dark and piercing. Her face was all angles; her features were sharp, and when conversing with her one could not but be struck with a certain eerie quality which seemed to give mystic colour to her expression. She was badly dressed, both from an æsthetic and a fashionable point of view. In a group of women you would pick her out to be a doctor, a lawyer, an intellectuelle. When I talked with her, impression followed impression—always I felt her intelligence, the play of her intellect upon the surfaces of her art, but always, too, I felt how narrow a chance had cast her lot upon the stage, how she easily might have been something else than a singing actress, how magnificently accidental her career was!

She was, it would seem, an unusually gifted musician—at least for a singer,—with a physique and a nervous energy which enabled her to perform miracles. For instance, on one occasion she astonished even Oscar Hammerstein by replacing Lina Cavalieri as Salomé in Hérodiade, a rôle she had not previously sung for five years, at an hour's notice on the evening of an afternoon on which she had appeared as Elektra. On another occasion, when Mary Garden was ill she sang Louise with only a short forewarning. She told me that she had learned the music of Elektra between January 1, 1910, and the night of the first performance, January 31. She also told me that without any special effort on her part she had assimilated the music of the other two important feminine rôles in the opera, Chrysothemis and Klytæmnestra, and was quite prepared to sing them. Mme. Mazarin's vocal organ, it must be admitted, was not of a very pleasant quality at all times, although she employed it with variety and usually with taste. There was a good deal of subtle charm in her middle voice, but her upper voice was shrill and sometimes, when emitted forcefully, became in effect a shriek. Faulty intonation often played havoc with her musical interpretation, but do we not read that the great Mme. Pasta seldom sang an opera through without many similar slips from the pitch? Aida, of course, displayed the worst side of her talents. Her Carmen, it seemed to me, was in some ways a very remarkable performance; she appeared, in this rôle, to be possessed by a certain diablerie, a power of evil, which distinguished her from other Carmens, but this characterization created little comment or interest in New York. In Louise, especially in the third act, she betrayed an enmity for the pitch, but in the last act she was magnificent as an actress. In Santuzza she exploited her capacity for unreined intensity of expression. I have never seen her as Salome (in Richard Strauss's opera; her Massenetic Salomé was disclosed to us in New York), but I have a photograph of her in the rôle which might serve as an illustration for the "Méphistophéla" of Catulle Mendès. I can imagine no more sinister and depraved an expression, combined with such potent sexual attraction. It is a remarkable photograph, evoking as it does a succession of lustful ladies, and it is quite unpublishable. If she carried these qualities into her performance of the work, and there is every reason to believe that she did, the evenings on which she sang Salome must have been very terrible for her auditors, hours in which the Aristotle theory of Katharsis must have been amply proven.

Elektra was well advertised in New York. Oscar Hammerstein is as able a showman as the late P. T. Barnum, and he has devoted his talents to higher aims. Without his co-operation, I think it is likely that America would now be a trifle above Australia in its operatic experience. It is from Oscar Hammerstein that New York learned that all the great singers of the world were not singing at the Metropolitan Opera House, a matter which had been considered axiomatic before the redoubtable Oscar introduced us to Alessandro Bonci, Maurice Renaud, Charles Dalmores, Mary Garden, Luisa Tetrazzini, and others. With his productions of Pelléas et Mélisande, Louise, Thais, and other works new to us, he spurred the rival house to an activity which has been maintained ever since to a greater or less degree. New operas are now the order of the day—even with the Chicago and the Boston companies—rather than the exception. And without this impresario's courage and determination I do not think New York would have heard Elektra, at least not before its uncorked essence had quite disappeared. Lover of opera that he indubitably is, Oscar Hammerstein is by nature a showman, and he understands the psychology of the mob. Looking about for a sensation to stir the slow pulse of the New York opera-goer, he saw nothing on the horizon more likely to effect his purpose than Elektra. Salome, spurned by the Metropolitan Opera Company, had been taken to his heart the year before and, with Mary Garden's valuable assistance, he had found the biblical jade extremely efficacious in drawing shekels to his doors. He hoped to accomplish similar results with Elektra....

One of the penalties an inventor of harmonies pays is that his inventions become shopworn. A certain terrible atmosphere, a suggestion of vague dread, of horror, of rank incest, of vile murder, of sordid shame, was conveyed in Elektra by Richard Strauss through the adroit use of what we call discords, for want of a better name. Discord at one time was defined as a combination of sounds that would eternally affront the musical ear. We know better now. Discord is simply the word to describe a never-before or seldom-used chord. Such a juxtaposition of notes naturally startles when it is first heard, but it is a mistake to presume that the effect is unpleasant, even in the beginning.

Now it was by the use of sounds cunningly contrived to displease the ear that Strauss built up his atmosphere of ugliness in Elektra. When it was first performed, the scenes in which the half-mad Greek girl stalked the palace courtyard, and the queen with the blood-stained hands related her dreams, literally reeked with musical frightfulness. I have never seen or heard another music drama which so completely bowled over its first audiences, whether they were street-car conductors or musical pedants. These scenes even inspired a famous passage in "Jean-Christophe" (I quote from the translation of Gilbert Cannon): "Agamemnon was neurasthenic and Achilles impotent; they lamented their condition at length and, naturally, their outcries produced no change. The energy of the drama was concentrated in the rôle of Iphigenia—a nervous, hysterical, and pedantic Iphigenia, who lectured the hero, declaimed furiously, laid bare for the audience her Nietzschian pessimism and, glutted with death, cut her throat, shrieking with laughter."

But will Elektra have the same effect on future audiences? I do not think so. Its terror has, in a measure, been dissipated. Schoenberg, Strawinsky, and Ornstein have employed its discords—and many newer ones—for pleasanter purposes, and our ears are becoming accustomed to these assaults on the casual harmony of our forefathers. Elektra will retain its place as a forerunner, and inevitably it will eventually be considered the most important of Strauss's operatic works, but it can never be listened to again in that same spirit of horror and repentance, with that feeling of utter repugnance, which it found easy to awaken in 1910. Perhaps all of us were a little better for the experience.

An attendant at the opening ceremonies in New York can scarcely forget them. Cast under the spell by the early entrance of Elektra, wild-eyed and menacing, across the terrace of the courtyard of Agamemnon's palace, he must have remained with staring eyes and wide-flung ears, straining for the remainder of the evening to catch the message of this tale of triumphant and utterly holy revenge. The key of von Hofmannsthal's fine play was lost to some reviewers, as it was to Romain Rolland in the passage quoted above, who only saw in the drama a perversion of the Greek idea of Nemesis. That there was something very much finer in the theme, it was left for Bernard Shaw to discover. To him Elektra expressed the regeneration of a race, the destruction of vice, ignorance, and poverty. The play was replete in his mind with sociological and political implications, and, as his views in the matter exactly coincide with my own, I cannot do better than to quote a few lines from them, including, as they do, his interesting prophecies regarding the possibility of war between England and Germany, unfortunately unfulfilled. Strauss could not quite prevent the war with his Elektra. Here is the passage:

"What Hofmannsthal and Strauss have done is to take Klytæmnestra and Ægisthus, and by identifying them with everything evil and cruel, with all that needs must hate the highest when it sees it, with hideous domination and coercion of the higher by the baser, with the murderous rage in which the lust for a lifetime of orgiastic pleasure turns on its slaves in the torture of its disappointment, and the sleepless horror and misery of its neurasthenia, to so rouse in us an overwhelming flood of wrath against it and a ruthless resolution to destroy it that Elektra's vengeance becomes holy to us, and we come to understand how even the gentlest of us could wield the ax of Orestes or twist our firm fingers in the black hair of Klytæmnestra to drag back her head and leave her throat open to the stroke.

"This was a task hardly possible to an ancient Greek, and not easy even for us, who are face to face with the America of the Thaw case and the European plutocracy of which that case was only a trifling symptom, and that is the task that Hofmannsthal and Strauss have achieved. Not even in the third scene of Das Rheingold or in the Klingsor scene in Parsifal is there such an atmosphere of malignant, cancerous evil as we get here and that the power with which it is done is not the power of the evil itself, but of the passion that detests and must and finally can destroy that evil is what makes the work great and makes us rejoice in its horror.

"Whoever understands this, however vaguely, will understand Strauss's music. I have often said, when asked to state the case against the fools and the money changers who are trying to drive us into a war with Germany, that the case consists of the single word 'Beethoven.' To-day I should say with equal confidence 'Strauss.' In this music drama Strauss has done for us with utterly satisfying force what all the noblest powers of life within us are clamouring to have said in protest against and defiance of the omnipresent villainies of our civilization, and this is the highest achievement of the highest art."

Mme. Mazarin was the torch-bearer in New York of this magnificent creation. She is, indeed, the only singer who has ever appeared in the rôle in America, and I have never heard Elektra in Europe. However, those who have seen other interpreters of the rôle assure me that Mme. Mazarin so far outdistanced them as to make comparison impossible. This, in spite of the fact that Elektra in French necessarily lost something of its crude force, and through its mild-mannered conductor at the Manhattan Opera House, who seemed afraid to make a noise, a great deal more. I did not make any notes about this performance at the time, but now, seven years later, it is very vivid to me, an unforgettable impression. Of how many nights in the theatre can I say as much?

Diabolical ecstasy was the keynote of Mme. Mazarin's interpretation, gradually developing into utter frenzy. She afterwards assured me that a visit to a madhouse had given her the inspiration for the gestures and steps of Elektra in the terrible dance in which she celebrates Orestes's bloody but righteous deed. The plane of hysteria upon which this singer carried her heroine by her pure nervous force, indeed reduced many of us in the audience to a similar state. The conventional operatic mode was abandoned; even the grand manner of the theatre was flung aside; with a wide sweep of the imagination, the singer cast the memory of all such baggage from her, and proceeded along vividly direct lines to make her impression.

The first glimpse of the half-mad princess, creeping dirty and ragged, to the accompaniment of cracking whips, across the terraced courtyard of the palace, was indeed not calculated to stir tears in the eyes. The picture was vile and repugnant; so perhaps was the appeal to the sister whose only wish was to bear a child, but Mme. Mazarin had her design; her measurements were well taken. In the wild cry to Agamemnon, the dignity and pathos of the character were established, and these qualities were later emphasized in the scene of her meeting with Orestes, beautiful pages in von Hofmannsthal's play and Strauss's score. And in the dance of the poor demented creature at the close the full beauty and power and meaning of the drama were disclosed in a few incisive strokes. Elektra's mind had indeed given way under the strain of her sufferings, brought about by her long waiting for vengeance, but it had given way under the light of holy triumph. Such indeed were the fundamentals of this tremendously moving characterization, a characterization which one must place, perforce, in that great memory gallery where hang the Mélisande of Mary Garden, the Isolde of Olive Fremstad, and the Boris Godunow of Feodor Chaliapine.

It was not alone in her acting that Mme. Mazarin walked on the heights. I know of no other singer with the force or vocal equipment for this difficult rôle. At the time this music drama was produced its intervals were considered in the guise of unrelated notes. It was the cry that the voice parts were written without reference to the orchestral score, and that these wandered up and down without regard for the limitations of a singer. Since Elektra was first performed we have travelled far, and now that we have heard The Nightingale of Strawinsky, for instance, perusal of Strauss's score shows us a perfectly ordered and understandable series of notes. Even now, however, there are few of our singers who could cope with the music of Elektra without devoting a good many months to its study, and more time to the physical exercise needful to equip one with the force necessary to carry through the undertaking. Mme. Mazarin never faltered. She sang the notes with astonishing accuracy; nay, more, with potent vocal colour. Never did the orchestral flood o'er-top her flow of sound. With consummate skill she realized the composer's intentions as completely as she had those of the poet.

Those who were present at the first American performance of this work will long bear the occasion in mind. The outburst of applause which followed the close of the play was almost hysterical in quality, and after a number of recalls Mme. Mazarin fainted before the curtain. Many in the audience remained long enough to receive the reassuring news that she had recovered. As a reporter of musical doings on the "New York Times," I sought information as to her condition at the dressing-room of the artist. Somewhere between the auditorium and the stage, in a passageway, I encountered Mrs. Patrick Campbell, who, a short time before, had appeared at the Garden Theatre in Arthur Symons's translation of von Hofmannsthal's drama. Although we had never met before, in the excitement of the moment we became engaged in conversation, and I volunteered to escort her to Mme. Mazarin's room, where she attempted to express her enthusiasm. Then I asked her if she would like to meet Mr. Hammerstein, and she replied that it was her great desire at this moment to meet the impresario and to thank him for the indelible impression this evening in the theatre had given her. I led her to the corner of the stage where he sat, in his high hat, smoking his cigar, and I presented her to him. "But Mrs. Campbell was introduced to me only three minutes ago," he said. She stammered her acknowledgment of the fact. "It's true," she said. "I have been so completely carried out of myself that I had forgotten!"

August 22, 1916.

#classical music#opera#music history#bel canto#composer#classical composer#aria#classical studies#maestro#chest voice#Mariette Mazarin#soprano#Conservatoire de Paris#Opéra Paris#Opéra-Comique#Richard Strauss#Elektra#Golden age of opera#classical musician#classical musicians#classical history#history of music#historian of music#musician#musicians#diva#prima donna

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

April 25.1926 Puccini’s last Opera “Turandot” premiered in Scala di Milano. Here you can read the article one day later in “The Observer” about this very special evening.

#classical music#opera#music history#bel canto#composer#classical composer#aria#classical studies#maestro#chest voice#Giacomo Puccini#Turandot#Teatro alla Scala#La Scala#Golden age of opera#musician#musicians#history of music#historian of music#classical musician#classical musicians#classical history#diva#prima donna

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

OTD in Music History: Notable French composer Edouard Lalo (1823 - 1892) dies in Paris. After completing his musical studies at the Paris Conservatoire under historically important conductor Francois Habeneck (1781 - 1849), Lalo worked as a freelance string player and teacher in Paris. Lalo composed voluminously throughout his career – but today, he is chiefly remembered for the “Symphonie Espagnole” (1875), an unorthodox five-movement concerto for violin and orchestra that was written for Spanish virtuoso Pablo Sarasate (1844 - 1908) and remains firmly ensconced in the standard violin repertoire. Premiered just one month before Georges Bizet’s (1838 - 1875) opera “Carmen,” it is not a coincidence that both of these French masterpieces boast an overtly “Spanish” theme. Spanish music was en vogue in both France and Russia throughout the 1870s and 1880s… a trend which arguably reached its peak with Nicolai Rimsky-Korsakov’s (1844 - 1908) “Capriccio Espagnol” (1887), for which Pyotr Tchaikovsky (1840 - 1893) actually played castanets during the world premiere performance. (Really!) PICTURED: A c. 1910s real photo postcard showing Lalo sporting a "Princess Leia" haircut. Also shown is a copy of the first edition printed score of a slightly less famous work by Lalo, his 1st String Quartet (1855)... which he later substantially revised and thereby turned into his 2nd String Quartet (1884). Shrewd! Lalo signed and inscribed this particular copy to Alfred-Louis-Guillaume Turban (1847 - 1896), a violin professor at the Paris Conservatoire.

#classical music#opera#music history#bel canto#composer#classical composer#aria#classical studies#maestro#chest voice#Edouard Lalo#classical musician#classical musicians#classical history#history of music#historian of music#musician#musicians#diva#prima donna#golden age of opera

1 note

·

View note

Text

Aino Ackté: A nightingale from the snow-clad north

From The Sibelius companion:

Another Finnish soprano, Aino Ackté,* inspired some of Sibelius’s most powerful and individual expressions in song. She was tall, slim, attractive, and graceful enough to dance Salomé’s Dance of the Seven Veils. She had had a successful operatic career outside of Scandinavia and was a passionate and dramatic performer. “Her voice appears to have combined the powerful, lush quality of the dramatic soprano with the poetry of the lyric soprano, and even a measure of the suppleness of the coloratura virtuoso.” *’ Her roles ranged from the lighter ones like Nedda and Michaela to the weightier Tosca and Salomé. Sibelius heard her sing Strauss’s decadent heroine in 1910 in London in the company of his great friend, composer and conductor Granville Bantock. Bantock’s daughter and biographer, Myrrha Bantock, wrote that Ackté “made a very strong impression on the Finnish composer, who, according to my mother, was deeply attracted to her.” *

[...] The period during which Ackté and Sibelius were associated, roughly between 1903 and 1915, was a turbulent one for the composer and the time when he wrote the greatest number of songs. The soprano seems to have inspired some of his most profound and unique works. The seven songs that we know Sibelius composed for her include the vocally demanding Luonnotar for voice and orchestra, the profound sentiments of Hdstkvdll and J ubal, the passionate Teodora and Kyssen, Fafdng onskan (Idle Wishes), which demands vocal power, and Kaiutar, for which delicacy is needed.

[...] The approach of the empress Teodora elicits a melody of longing that soars over one and one-half octaves. While the theme of the poem and the musical pattern of tension and restraint are similar to Hymn to Thais, the Unforgettable, the musical language of Teodora is much more elaborate. Along with Kyssen, these three songs, two of which are closely connected to Aino Ackté, reveal an aspect of Sibelius’s psyche that is not often discussed. Teodora, unique in his entire song collection, is probably one of the most effective evocations of sexual desire in music.

Ackté, Aino (née Achté, 1876-1944). Born in Helsinki, this great dramatic soprano came from a family of singers. Her mother was her first teacher, and both she and her sister Emmy (1850-1924) became noted vocalists. Ackté studied in Paris with Paul Vidal and others. After her debut at the Paris Opera in 1897, she made guest appearances the world over, at Covent Garden, at New York’s Metropolitan Opera House, and in Paris. Together with Edvard Fazer (a pianist born in 1861, a brother of Karl Fazer [1866-1922] who founded Finland’s noted candy-making factory, and a relative of the Fazer who founded the still-thriving Fazer’s music store), Ackté established the first permanent Finnish Opera in 1911 and later served as its director. Sibelius dedicated to Ackté some of his most beautiful and demanding songs, including Jubal, Hostkvall, and Luonnotar, the last of which she premiered in Gloucester in 1913.

From Jean Sibelius by Rickards, Guy:

Sibelius still harboured the desire to write a work for Aino Ackté, not least after twice disappointing her over The Raven and Juha. He had also wanted to compose a tone-poem on the Kalevala creation myth, centred on the daughter of the air, Luonnotar (and in 1905 Pohjolas Daughter had originated in this way), and decided to combine this with a commission from the Three Choirs Festival in Britain for a choral work. In July 1913, alongside the early stages of Scaramouche, he set to work and completed the score, for solo soprano and orchestra with no choral parts, in late August. Ackté went over the piece, a unique fusion of orchestral song and symphonic poem, with the composer at Ainola before travelling to Gloucester to give the premiére on 10 September. Although well received, Sibelius made some minor adjustments to the score and sent it off to Breitkopf in October. They were nervous about publishing what they viewed as a song of such large (at nine minutes’ duration) dimensions, and it only appeared in a voice-and-piano edition; the orchestral score was not published until 1981.

From Sibelius : a composer's life and the awakening of Finland by Goss, Glenda Dawn:

One wonders for whom Sibelius was writing Luonnotar. Ostensibly, it was the beautiful soprano Aino Ackté (1876-1944), to whom the tone poem was dedicated. Myrrha Bantock, the sharp-eyed offspring of composer Granville, recalled that Aino Ackté “made a very strong impression on the Finnish composer, who, according to my mother, was deeply attracted to her.” It was something of a love-hate relationship that had been despoiled when Sibelius backed out of a promise to compose an orchestral song for Ackté. It was to be on Edgar Allan Poe’s poem The Raven [...].

[...] And aside take the new work on a central European tour.** That was in 1910, and Ackté made her diva displeasure crystal-clear at such unheard-of abandonment. Luonnotar offered Sibelius some kind of redemption. Ackté gave its first performance, at the Three Choirs Festival in Gloucester, England, on September 10, 1913, without Sibelius in view (the work was conducted by the British composer Herbert Brewer).

Did Sibelius truly expect so personal, so esoteric, so mystically Finnish a work, to succeed abroad? At the first performance, the audience, even with an English translation in hand, found the text nearly incomprehensible. As one reviewer bravely declared, “The orchestral undercurrent seemed more interesting than the vocal part, but . . . one has to exert faith that there is more in the music than is apparent on one hearing.”** And aside from Ackté, who could be expected to perform so demanding a composition? Not only are its formidable language and its weird and wondrous tale far removed from Western thought traditions, but so too are its musical demands. The most well-known is the cry Ei! on a high C-flat (bars 125-30), the first time poco forte, the second time—heaven forfend!—pianissimo. Cecil Gray later described it as “one of the highest pinnacles in the whole range of Sibelius’s creations, and consequently in the entire range of modern music.”*” And he was not just talking about that C-flat.

From Sibelius by Layton, Robert, 1930-:

[...] Although Lwonnotar is not a symphonic poem in the usual sense of the word (or even the Sibelian unusual sense), it is on too extended a scale to be regarded as a song with orchestra or even a scena like Hostkvall. Indeed it is quite unlike anything else in music. Original even by Sibelius’s own standards, the work bears the subtitle ‘tone poem for voice and orchestra’. While in design it is not as subtle or complex as Pobjola’s Daughter or The Oceanides, it is remarkably continuous in feeling. Lwonnotar is the mistress of the air in Finnish mythology, and the words tell of the story of the creation of the world as related in the first Runo of the Kalevala. It seems likely that it was nearing completion as early as 1910, since the first performance of a ‘new tone-poem written for the Finnish soprano Aino Ackté’ was promised for that year. In the event, however, it appeared only after a further three years, in which the fourth symphony and The Bard saw the light of day, when it was given its premiére in Gloucester.

#classical music#opera#music history#bel canto#composer#classical composer#aria#classical studies#maestro#chest voice#The nightingale#dramatic soprano#soprano#Paris Opera#Conservatoire de Paris#Metropolitan Opera#Met#Covent Garden#Golden age of opera#A nightingale from the snow-clad north#classical musician#classical musicians#classical history#history of music#historian of music#musician#musicians#diva#prima donna#Aino Ackté

1 note

·

View note

Text

OTD in Music History: British composer and suffragist Dame Ethel Smyth (1858 - 1944), the first female composer to ever be granted a damehood (in 1922), is born in London. Few figures in musical history have led a more colorful life than Smyth. After having a bitter fight with her father over her desire to pursue music as a career, Smyth was allowed to study composition at the Leipzig Conservatory. Although she left after only a year (disillusioned with what she considered to be the low standard of teaching), her brief attendance there put her in contact with a host of musical luminaries including Clara Schumann (1819 - 1896), Johannes Brahms (1833 - 1897), Pyotr Tchaikovsky (1840 - 1893), Antonin Dvorak (1841 - 1904), and Edvard Grieg (1843 - 1907)... and upon her return to England, she also formed a fast friendship with Sir Arthur Sullivan (1842 - 1900). Smyth's extensive body of work includes two notable operas: - For more than a century, "Der Wald" (1903) claimed the distinction of being the only opera composed by a woman to have ever been produced at New York's Metropolitan Opera (until Kaija Saariaho's [1952 - 2023] "L'Amour de loin" was premiered in 2016). - "The Wreckers" (1906) is also widely admired, and considered by some critics to be the greatest and most historically important British opera composed between Henry Purcell (1659 - 1695) and Benjamin Britten (1913 - 1976). Smyth’s last major completed work was a symphony entitled "The Prison" (1931). By the mid-1930s, she had gone almost completely deaf. But that's not all. Smyth was *also* a prominent British suffragist (she was imprisoned for her political activism) who lived openly as a lesbian at a time when such things were almost unheard of. At the age of 71, she fell in love with writer Virginia Woolf (1882 - 1941), who was nearly 25 years her junior. Woolf was both alarmed and amused, comparing it to “being caught by a giant crab." The two women eventually settled into a close platonic friendship. PICTURED: A formal portrait photograph showing the young Smyth her beloved dog, Marco. Also shown is an 1931 autograph letter written and signed by Smyth concerning her musical activities.

Smyth rescued Marco from the streets of Vienna during his student days at the Conservatory. In her memoirs, Smyth later described Marco as “half St. Bernard, and the rest whatever you please.” Marco quickly became the joy of Smyth's life, and he would happily spend hours lying quietly by her side as she composed -- often with his head resting on the pedals of her piano. Marco’s most infamous moment undoubtedly occurred when Smyth was invited to attend a rehearsal of Johannes Brahms' (1833 - 1897) F minor Piano Quintet that was taking place at Brahms's apartment. Although Smyth wisely left Marco tethered outside, he simply refused to be parted from her for that long -- and so at some point while the young Smyth was inside seated at the piano and turning pages for Brahms, Marco managed to get loose from his leash, dash up two flights of stairs, nuzzle open the unlocked front door, and make his way into the drawing room where Brahms and four local Viennese musicians were rehearsing. Bounding onto the scene, Marco immediately dove under the piano (overturning the cellist's music stand in the process) and wiggled his way in between Smyth and the astonished composer. As Smyth later described it, Brahms “rose to the occasion” and “laughed till he got purple in the face" while happily petting Marco. (No word on how the cellist reacted.)

#classical music#opera#music history#bel canto#composer#classical composer#aria#classical studies#maestro#chest voice#Dame Ethel Smyth#Ethel Smyth#women's suffrage#Metropolitan Opera#Met#classical musician#classical musicians#classical history#history of music#historian of music#musician#musicians#diva#prima donna#golden age of opera#woman in music

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

"At Midnight On My Pillow Lying" from Jakobowski's opera Erminie Elizabeth Spencer

Erminie is a comic opera in two acts composed by Edward Jakobowski with a libretto by Claxson Bellamy and Harry Paulton, based loosely on Charles Selby's 1834 English translation of the French melodrama, Robert Macaire. The piece opened at the Grand Theatre, Birmingham, England, on 26 October 1885 before transferring to the Comedy Theatre in London on 9 November 1885 and playing for a total of 154 performances. A long-running production opened on Broadway in 1886, and the opera enjoyed unusual international success that endured into the twentieth century. Erminie became a revered classic, produced all over the United States and the second act “Lullaby” becoming universally known and loved. The New York Times: The success of Erminie can scarcely be questioned. The chief merit of Erminie is the combination it offers of pleasing and enlivening strains with an exceptionally good libretto.

The youngest of four children, Elizabeth Spencer was born Elizabeth Dickerson on April 12, 1871; her father died eight months later. In 1874, her mother remarried to Col. William Gilpin, who had served as the first governor of the Territory of Colorado in 1861. The family moved to Denver, where Spencer received vocal training and learned to sing, recite stories and poetry, and play piano and violin. She graduated from St. Mary’s Academy and, after going on an extensive European tour, married Otis Spencer, an attorney.

A recognized society woman, Spencer sang in churches, concerts, clubs, parties and amateur theatricals. She got her big break in 1905, performing a successful solo act at the local Orpheum Theatre, her professional debut in a major vaudeville house.

Her second engagement, a one-act sketch, displayed her acting abilities, and the experience led to roles in Broadway road companies. By 1910, she was residing in New York City and making her first recordings in an era dominated by a formal, opera-influenced style of singing. Signing an exclusive contract with inventor and businessman Thomas Edison’s staff, she became its most prolific vocalist in the studio, participating in solos, duets, trios, quartets and choruses. Edison loved Spencer’s rich, high-quality voice—she was often billed as a “dramatic soprano”—and he would frequently study its vibrations and quality.

Having made only phonograph cylinders, Edison decided to add a disc format to the product line because of increasing competition from rivals such the Victor Talking Machine Company. His “Diamond Discs” enjoyed commercial success from the mid 1910s to the early 1920s. Spencer’s first Diamond Discs were distributed as samples to dealers to demonstrate on phonographs. The Diamond Disc was where the majority of her best work was heard, her singing quality reproduced with greater accuracy.

The public “Tone Test” demonstrations would prove to be Edison’s greatest promotional scheme. He chose Spencer to travel around the country and fill theaters and auditoriums, greeted by dealers, salespeople and thousands of Edison phonograph owners. She would sing at the same level with the phonograph. The venue would darken, and the audience members had to guess when the artist stopped singing and when the phonograph took over, revealing the superior qualities of Edison’s sound reproduction.

The Edison studio cashbooks document Spencer in approximately 661 sessions by the time her Edison commitment expired in 1916, more than any other vocalist. She signed with the Victor Talking Machine Company, but her output there paled in comparison to that at Edison. She returned to Edison in 1920, though her recording sessions slowed down considerably. When radio broadcasting began in the 1920s, she sang and recited “on the air.” Despite the greater audio fidelity of Diamond Discs, they were more expensive than and incompatible with other brands of records, ultimately failing in the marketplace; Edison closed the record division a day before the 1929 stock market crash. Spencer died in Montclair, New Jersey in 1930, ten days after her 59th birthday.

#classical music#opera#music history#bel canto#composer#classical composer#aria#classical studies#maestro#chest voice#Elizabeth Spencer#mezzo-soprano#soprano#dramatic soprano#comic opera#Edward Jakobowski#Golden Age of Opera#classical musician#classical muscians#classical history#history of music#historian of music#musician#musicians#diva#prima donna#early recordings#Edison

1 note

·

View note

Text

Ilma de/di/von Murska photographed as Juliette from Charles Gounod’s Roméo et Juliette

From Divas : Mathilde Marchesi and her pupilsby Neill, Roger:

One of Marchesi’s greatest pupils, IIma di Murska, had already toured Australasia accompanied by massive media coverage. And she was followed there by a steady stream of other Marchesi pupils, both foreign and Australian, most prominently Nellie Melba herself.

The fourth major star to emerge from Mathilde Marchesi’s first period teaching at the Conservatoire in Vienna was the Croatian-born soprano, Ilma di Murska. She had one of those lives which are substantially lived in public, her celebrity driven by a combination of her talent and her oddness. It would take a very dedicated researcher to untangle truth from fiction in the story of her life, and perhaps the outrageousness of it all is really who she was. Di Murska was the first of Mathilde Marchesi’s students to achieve success in Englishspeaking countries — in Great Britain and Ireland, America, Australia and New Zealand.

She was born Ema Pukéec in 1834 at Ogulin, her mother Krescencia Brodarotti de Trauenfeld, her father, Josip PukSec, a senior army officer in the Austrian army. Croatia was at that time part of the Austrian Empire and for his good work as a soldier, Puk&ec was granted an aristocratic title by the emperor, adding Murski to his name, the feminine form of this, Murska, being adopted in due course by his daughter. By contrast with Gabrielle Krauss’s long and glittering career, Ilma di Murska’s started brilliantly, but eventually faded disastrously.

Ema studied piano from five years old and, after her family moved to Zagreb in 1850, she started singing. At seventeen she married a soldier, Josip Eder, with whom she had two children, Alfons and Hermine. The young family moved to Graz in Austria in 1857, then to Vienna three years later, so that Ema could pursue her studies as a singer. Auditioning for Mathilde Marchesi at the Conservatoire, she made it clear that she ‘was already married and the mother of two small children’. Nevertheless, she had ‘a sweet, flexible, and high soprano voice, but was also very musical, and a quick learner’. Just the sort of musician that Mathilde really liked to teach.

After Ema’s first year at the Conservatoire, Marchesi decided to give up her teaching role in Vienna, moving herself, her family and her practice to Paris. Twelve students followed her there, one of them Ema PukSec. Did Ema take her husband and children to Paris with her? They no longer seem to be referred to in despatches, so in all likelihood they were either left in Vienna, or the children were parked with relatives.

Her professional career, in which she was now known as Ilma di Murska, started at the Pergola Theatre in Florence in 1862, either as Lady Harriet in Flotow’s Martha, or as Marguérite de Valois in Meyerbeer’s Les Huguenots — no one seems sure which came first. She then toured Europe, performing in Hungary, Spain and Italy. After a string of successful appearances, Ilma arrived in Vienna, where she made her debut at the Court Opera on 16 August 1862 in I/ rovatore. That season ended with Ilma as Ophélie in Ambroise Thomas’s Hamlet, its first performance in that city. She was particularly noted also for her Queen of the Night in The Magic Flute, in the title role of Lucia di Lammermoor, as Dinorah and as Isabella in Rodert le Diable. It was in Vienna that she was first dubbed the ‘Croatian Nightingale’.

From Vienna Ilma moved on to be prima donna in James Mapleson’s company in London, making her debut as Lucia di Lammermoor at Her Majesty's Theatre on 11 May 1865. Mapleson was arguably the most important opera impresario in Britain and the United States in the second half of the nineteenth century, regularly recruiting the world’s best singers to his company. He was born in London and from the age of fourteen studied as a singer and violinist at the Royal Academy. By 1856 he was operating as a musical agent in the Haymarket, engaging artists for Her Majesty’s and for Covent Garden, and in 1862 he became manager of Her Majesty’s, forming for the first time his own company. It was this ensemble that IIma di Murska joined in 1865 — ‘a lady who at once took high rank from her phenomenal vocal qualities’, wrote Mapleson. Two weeks after her entry as Lucia, Ilma took the title role in another of Donizetti’s de/ canto vehicles, Linda di Chamounix.' This had not been seen for over twenty years in London and Ilma made a big impression years in London and Ilma made a big impression, the Pa// Mall Gazette greeting her warmly:

It is quite true that she is entirely original, it is also true that she has the feu sacré, and if we take the trouble to speak so very outset by false and unfriendly praise.!”

That first season with Mapleson, Ilma also sang Dinorah and the Queen of the Night in what Mapleson calls I/ auto magico (The Magic Flute), sung in Italian. At the first performance of The Magic Flute, Ilma’s co-star, the baritone Sir Charles Santley (who was to sing with Ilma regularly over the following years in Mapleson’s company) told the story in his memoirs of a back-stage fire at Her Majesty’s:

Ilma di Murska ran across the stage, followed by two gentlemen in evening dress; immediately an alarm for fire was raised ... The stage manager hurriedly told me that some gauze had caught fire, but the fire had been extinguished ... I saw not a moment was to be lost to save many from being trampled to death, so I rushed to the footlights, and called out with more energy than politeness: “There is no fire; it is put out! Sir still we are going on with the opera!”!

Herman Klein later wrote:

In the role of the Queen of the Night I heard her more than once. In that trying part no one — not even Marcella Sembrich — ever in my experience approached Ilma di Murska. The exceptionally lofty range of her voice enabled her to cope effortlessly with the octave leading to the F in alt. She simply revelled in it; making every note as clear, strong, and dramatic, as pure and ringing in tone, as the two octaves below that forming a wholly perfect 3-octave scale.'”

The opera critic and historian Harold Rosenthal noted in 1958 that ‘Di Murska was almost as popular in London in the Patti roles as the great soprano herself”. She played the ‘demented heroine’ Dinorah again the following season, ‘a truly magnificent performance’, wrote Mapleson. In 1868 Mapleson took his company to Covent Garden, where they were to remain for three seasons, Ilma starring in many of the leading roles. Of the 1869 season, Rosenthal observed: included Di Murska, Lucca, Nilsson, Patti and Tietjens.”"

In 1870-71 Mapleson’s company moved on to the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, where aside from her regular roles, IIma sang Senta in The Flying Dutchman (with Santley as the Dutchman) — the first time that an opera by Wagner had been performed in London. Ilma spent 1872 and the early months of 1873 with Mapleson’s company touring the major cities of Britain and Ireland, giving both concerts and operas. In his memoirs, Mapleson joyfully noted both her reliability and her eccentricity:

Ilma di Murska was punctual with a punctuality which put one out quite as much as utter inability to keep an appointment would have done. She was sure to turn up on the very evening, and at the very hour when she was wanted for a representation. But she had a horror of rehearsals, and thought it never worthwhile, when she was travelling from some distant place on the Continent, to announce that she had started, or to give any idea as to when she might really be expected.”

She would take what she thought of as ‘short cuts’, but these frequently turned out to be ‘of the most extraordinary kind’. In particular, she had grown an aversion to the railway station at Cologne, ‘where she declared that a German officer had once spoken to her without being introduced’. At some point, at the height of her popularity, she disappeared for a while, rumoured to be involved with the King of Prussia.” Mapleson vividly described the collection of animals with which she always travelled:

[Every] prima donna has generally a parrot, a pet dog, or an ape, which she loves to distraction, and carries with her wherever she goes. Ilma di Murska, however, travelled with an entire menagerie. Her immense Newfoundland, Pluto, dined with her every day. A cover was laid for him as for her, and he had learned to eat a fowl from a plate without dropping any of the meat or bones on the floor or even on the table cloth. Pluto was a good-natured dog, or he would have made short work of the monkey, the two parrots, and the Angora cat, who were his constant associates ... I must do the monkey justice to say that he did his best to kill the cat ... [The parrots] flew about the room, perching everywhere and pecking at everything.”

Briefly Ilma returned to Drury Lane, before leaving Mapleson’s company and going on to tour America, Australia and New Zealand. She had been with Mapleson for eight seasons. Not too accurately, The Times in London had named her ‘the Lovely Hungarian Nightingale’, a name that stuck. That year she toured Europe again, then leaving for the United States, where she travelled and performed extensively. From October 1873 she toured with Max Maratzek’s Italian Opera Company, opening as Amina in La sonnambula at the Grand Opera House (previously Pike’s) in New York. She had great success there, Watson’s Art Journal commenting on a scena from Lucia dt Lammermoor:

Di Murska’s singing of this aria could hardly be surpassed; in all points of execution it evidences almost absolute perfection; all her fioriture was rapid, clear and brilliant; her trills or shakes, even up in altissimo, were even and rapid, and in all, her intonation was altogether faultless.

Her time with Maratzek would have been accompanied by significant risk. As both impresario and conductor, he had a reputation for an explosive temperament, and at the same time Ilma shared top billing with one of the other great sopranos of her generation, Pauline Lucca, who had recently left Berlin, where she had been engaged in a fractious and long-running rivalry with another diva, Mathilde Mallinger. In the event, at least on the surface, things seem to have run quite smoothly between the three of them, and Ilma went on to perform in cities across the continent. In Cincinnati, she was compared favourably with Patti:

The trill, in its several varieties, the run, the crescendo, and the delicious little bird-like staccato with which Adelina Patti took the town captive when she first went upon the stage — all these accomplishments Mme di Murska had at her tongue’s end. She is a singer to delight connoisseurs and amaze the singer to delight connoisseurs and amaze the multiude.