#history of writing

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

#christmas facts#writers#creative writing#writing#writing community#writers of tumblr#creative writers#writing inspiration#history of writing#a chirstmas carol#christmas cards#holiday season#festive season#fun facts about books#fun facts#writer#writers on tumblr#writers and poets

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

Your Brain Was Never Supposed to Read

How a Man-Made Invention Rewired Human Cognition

Literacy: A Modern Superpower We Overlook

Reading feels just like second nature to us, so much so that we tend to forget that it's not something our brains were originally programmed to accomplish. Whether you're texting on your cell phone, browsing headlines, or reading a movie with subtitles, literacy's so integral to contemporary life that it feels like a hardwired ability. But this ease is illusory.

While people learn to speak automatically, starting from infancy, reading is an artificial invention. It has to be consciously taught and laboriously acquired. And nevertheless, today more than 87% of the world's population is literate. The question is: how did it happen? And more interestingly, what did this invention do to our brains?

Writing: A Surprisingly Recent Innovation

Spoken words are old, perhaps as old as Homo sapiens themselves, at least 135,000 years old. But writing is ridiculously recent. The earliest known writing system, Sumerian cuneiform, did not appear until about 3200 BCE. That's only about 5,000 years ago, the equivalent of a blink of the eye in evolutionary time.

This implies that for more than 95% of the history of our species, we transmitted knowledge verbally. Tales, legislation, and ceremonies, all remembered and articulated. Writing did not augment language; it revolutionized it. It made it possible to save thoughts for good, preserving them in a permanent form; carry ideas across geographies and across epochs; and, most importantly, free communication from the sender's location. Civilization, as we understand it, was founded on this transformation.

Recycling the Brain: The Neuroscience of Reading

So, how did our brains adjust to this revolutionary invention? The quick answer: they didn't, not initially. Reading was not something the human brain developed for. Rather, it's a cognitive hack, a genius repurposing of what was already there.

Neuroscientist Stanislas Dehaene refers to this as "neuronal recycling." The brain hijacks areas initially devoted to object and face recognition, visual processing, and spoken language, and uses them for reading. For instance, the "visual word form area" in the left fusiform gyrus is responsible for identifying written words and letters. But this area wasn't designed for reading; it was developed to recognize intricate visual patterns in the environment. With time and practice, our brains adapted to recognizing letters as shapes and relating them to sound and meaning.

Briefly: your brain doesn't read words as much as it sees patterns, makes sense of them based on learned connections, and imposes them on sound-based networks of language. Reading is a neural hack, a genius one.

The Cognitive Trade-Off

Reading brought huge benefits: memory outsourced through books, concepts traded across the globe, and knowledge amplified beyond the confines of the oral tradition. But this progress had cognitive trade-offs.

In cultures where oral tradition was prevailing, individuals had remarkable memory and listening abilities. Epic poems such as the Iliad and the Mahabharata were being recited orally, word by word, generation after generation. With the discovery of writing, followed by that of the printing press, such acts of memory were no longer required. In return, we inherited something potentially greater: selectively forgetting, storing externally, and abstract thinking via symbols.

But our brains were reconditioned, gradually, over decades, to read with ease. Kids don't learn to read the way they naturally learn to talk. It takes practice, focus, and sometimes grit. That's because each time you read, your brain is actually executing a sophisticated simulation, connecting shape to sound to meaning, in an instant.

Why It Matters Today

Understanding that reading is not an evolved instinct but a trained skill matters more than ever in an age of digital distraction. Screens and fast-scrolling content increasingly pull us away from deep reading. Yet deep reading, the kind that activates critical thinking, reflection, and empathy, is one of the highest cognitive functions we’ve developed.

As AI begins to read, write, and summarize for us, there’s a temptation to offload even this skill. But that would be a mistake. Reading is not just about information consumption. It’s about cognitive development. It strengthens our focus, expands imagination, and rewires the brain in ways few other activities do.

Conclusion: Reading as a Radical Act

Your brain didn't evolve to read. But it did. And as it did so, it changed human culture, and human brains,

Whenever you read a book or stop to read a contemplative article, you're doing one of the most advanced and unnatural things a human being can do. And that's what makes it beautiful. Reading isn't something we do; it's a revolution that occurs silently in the mind, word by word, neuron by neuron.

#neuroscience#reading#brain rewiring#literacy#history of writing#cognitive science#neuroplasticity#language and thought#deep reading#humanevolution#education#slow thinking

2 notes

·

View notes

Link

#cuneiform#news article#writing history#history of writing#lexical lists#clay tablets#ancient history#ancient mesopotamia#mesopotamia

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Evolution of the Alphabet: A Story of Human Ingenuity and Innovation 🤯

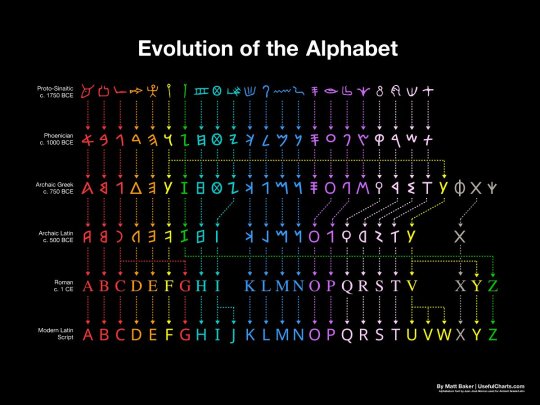

How the Alphabet Changed the World: A 3,800-Year Journey

The evolution of the alphabet over 3,800 years is a long and complex story. It begins with the ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs, which were a complex system of pictograms and ideograms that could be used to represent words, sounds, or concepts. Over time, the hieroglyphs were simplified and adapted to represent only sounds, resulting in the first true alphabets.

The first alphabets were developed in the Middle East, and the Phoenician alphabet is considered to be the direct ancestor of the Latin alphabet. The Phoenician alphabet had 22 letters, each of which represented a single consonant sound. This was a major breakthrough, as it made it much easier to write and read.

The Phoenician alphabet was adopted by the Greeks, who added vowels to the system. The Greek alphabet was then adopted by the Romans, who made some further changes to the letters. The Latin alphabet, as we know it today, is essentially the same as the Roman alphabet, with a few minor modifications.

The English alphabet is derived from the Latin alphabet, but it has undergone some further changes over the centuries. For example, the letters "J" and "U" were added to the English alphabet in the Middle Ages, and the letter "W" was added in the 16th century.

The evolution of the alphabet has had a profound impact on human history. It has made it possible to record and transmit knowledge, ideas, and stories from one generation to the next. It has also helped to facilitate communication and trade between different cultures.

The alphabets are a fascinating invention that have revolutionized the way humans communicate and record information. The history of the alphabets spans over 3,800 years, tracing its origins from the ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs to the modern English letters.

Here is a brief overview of how the alphabets have evolved over time:

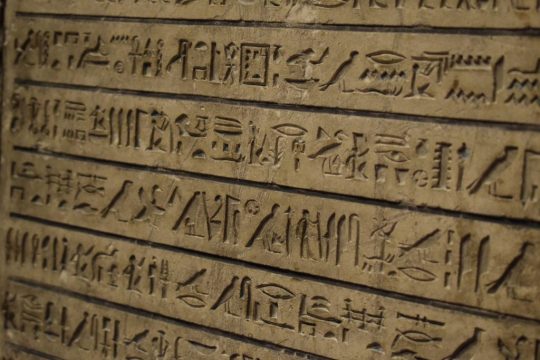

Egyptian hieroglyphs (c. 3200 BC): The earliest form of writing was the pictographic system, which used symbols to represent objects or concepts. The ancient Egyptians developed a complex system of hieroglyphs, which combined pictograms, ideograms, and phonograms to write their language. Hieroglyphs were mainly used for religious and monumental purposes, and were carved on stone, wood, or metal.

Proto-Sinaitic script (c. 1750 BC): Around 2000 BCE, a group of Semitic workers in Egypt adapted some of the hieroglyphs to create a simpler and more flexible writing system that could represent the sounds of their language. This was the first consonantal alphabet, or abjad, which used symbols to write only consonants, leaving the vowels to be inferred by the reader. This alphabet is also known as the Proto-Sinaitic script, because it was discovered in the Sinai Peninsula.

Phoenician alphabet (c. 1000 BC): A consonantal alphabet with 22 letters, each of which represented a single consonant sound. The Proto-Sinaitic script spread to other regions through trade and migration, and gave rise to several variants, such as the Phoenician, Aramaic, Hebrew, and South Arabian alphabets. These alphabets were used by various Semitic peoples to write their languages, and were also adopted and modified by other cultures, such as the Greeks, Etruscans, and Romans.

Greek alphabet (c. 750 BC): The Greek alphabet was the first to introduce symbols for vowels, making it a true alphabet that could represent any sound in the language. The Greek alphabet was derived from the Phoenician alphabet around the 8th century BCE, and added new letters for vowel sounds that were not present in Phoenician. The Greek alphabet also introduced different forms of writing, such as uppercase and lowercase letters, and various styles, such as cursive and uncial.

Latin alphabet (c. 500 BC): The Latin alphabet was derived from the Etruscan alphabet, which was itself derived from the Greek alphabet.

Roman alphabet (c. 1 CE): The Roman alphabet is essentially the same as the Latin alphabet, as we know it today. The Latin alphabet was used by the Romans to write their language, Latin, and became the dominant writing system in Europe after the fall of the Roman Empire. The Latin alphabet was also adapted to write many other languages, such as Germanic, Celtic, Slavic, and Romance languages.

English alphabet (c. 500 AD): The English alphabet is derived from the Latin alphabet, but it has undergone some further changes over the centuries. For example, the letters "J" and "U" were added to the English alphabet in the Middle Ages, and the letter "W" was added in the 16th century. The English alphabet consists of 26 letters, but can represent more than 40 sounds with various combinations and diacritics. The English alphabet has also undergone many changes in spelling, pronunciation, and usage throughout its history.

The evolution of the alphabet is a remarkable example of human creativity and innovation that have enabled us to express ourselves in diverse and powerful ways. It is also a testament to our cultural diversity and interconnectedness, as it reflects the influences and interactions of different peoples and languages across time and space.

Thank you for reading! I hope you enjoyed the post about the evolution of the alphabet. If you did, please share it with your friends and family. 😊🙏

#evolution of the alphabet#history of writing#alphabet#hieroglyphs#proto-sinaitic script#phoenician alphabet#greek alphabet#roman alphabet#english alphabet#language#linguistics#consonantal alphabet#syllabic alphabet#ancient egyptian#greek mythology

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

I just wanted to post something i made

#writing#writers on tumblr#words#artists on tumblr#book photography#dystopia#dystopian fiction#history of writing#history#dystopian 1984#1984

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fascinating Footnotes

I doubt anyone who has been reading either my blog or my newsletter for any length of time is unaware that I like to use footnotes, both to cite sources and to add a bit of clarity/an amusing aside when I think putting it in the main text would break the flow. However I realised, thanks to a comment left on one be-footnoted post1, that I really didn’t have much idea of the history of the footnote…

View On WordPress

#earliest footnotes#footnotes#Hadrian&039;s Wall#History#history of footnotes#history of writing#Jingo by Terry Pratchett#longest footnote in history#northumberland#Pavlovian response#precursors of footnotes#research#Reverend John Hodgekin#Roman History#Terry Pratchett#Terry Pratchett&039;s footnotes

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Those who cannot remember the past..."

Can’t believe Jane Austen wrote Pride and Prejudice in the 2000s

And in 2015 Emily Brontë released literary clsssic Wuthering Heights

Thank God someone paved the way for them…

#...are schmucks#women writers#btw great list thanks!#women in history#history of writing#misogny#patriarchy tunnelvision#long post

135K notes

·

View notes

Text

Huge thanks to Richard of the Order of the Blade for throwing me around!

(If you’re in the UK, consider checking them out! The order are a combat school with a really fun and welcoming ethos)

And as always, more bows, swords, and nonesense on Patreon

60K notes

·

View notes

Text

Learn to let go, it will be okay

#quotes#quoteoftheday#wholesome#positivity#writing#life quotes#love quotes#book quotes#aesthetic#art#vintage#photooftheday#photography#history#text#spilled thoughts

16K notes

·

View notes

Text

Stuck in a parragraph because I can't find accurate information on whether or not parchment in the 18th century could be water resistant up to some point. Its not paper paper so... maybe?

#im literaly screaming into the void while i do research but if anyone actually reads this as knows the answer#by all means hit me up#my wiritng#creative writing#writing#historical writing#parchment#history of art#history of writing#18th century history

0 notes

Text

From Manuscripts to E-Readers: 10 Milestones in Book History

The book, in its various forms, has been humanity’s most enduring and impactful medium for preserving knowledge, sharing stories, and transmitting ideas across generations. From the earliest scratches on clay tablets to the pixels on a modern e-reader, its evolution is a fascinating journey that mirrors the progress of civilization itself. Each transformation in how books are created, reproduced,…

#Aldus Manutius#ancient libraries#ancient manuscripts#book formats#book technology#Clay tablets#codex#communication history#digital books#e-readers#evolution of books#Friedrich Koenig#future of books#Gutenberg Bible#historical innovations#history of books#history of reading materials#history of writing#illuminations#industrial printing#information dissemination#Johannes Gutenberg#Keywords: book history#Kindle#knowledge transfer#Library of Alexandria#literacy history#mass market books#medieval scriptoriums#modern publishing

0 notes

Text

#writers#creative writing#writing#writing community#writers of tumblr#creative writers#did you know#writing facts#bookish facts#cuneiform#epic of gilgamesh#the epic of gilgamesh#history of writing

63 notes

·

View notes

Text

In the late 1970s a glowing orb appeared in the sky. Every day at about 5:00 Greenwich standard time, the orb would go somewhere new, shoot out something similar to a laser, and kill one person. Every day, always at the same time, always exactly one person.

The person killed by the orb seemed completely random, with almost fifty years of studying it we've been able to find no rhythm or reason to who it kills. It kills the old, the young, the rich, the poor, the urban, the rural, anyone. Every human on earth seems to have an equal chance of being killed by the orb. It's a headline the few times someone of note is killed by the orb: Britain famously lost a Parliament member to the orb, Brazil to this day remains the only country where a head of state was killed by the orb while in office, there was a short lived sitcom in the 1990s called Friends that ended halfway through its first season due to the orb killing one of the main actors on set. However, these are outliers, on any given day the person who dies via orb is very likely to be someone you never heard of. There are billions of people on earth, and only one is killed by the orb every day. In almost fifty years only a little over 18000 have died because of the orb, which is nothing in the face of the sheer amount of humans that exist.

When the orb first appeared people were horrified. Both the US and USSR thought it was a weapon from the other side. Almost every religion made some claim of it being proof of their beliefs, oftentimes claiming it was divine punishment. Atheists claimed it was proof no loving God could exist. People were so very apocalyptic and horrified by it, they thought of it as part of the end times, because when it was new that's really how it looked.

However, it's been long enough so that's changed. Most people have lived their entire lives in a world where the orb exists. The orb isn't that scary a concept. People know their odds of being killed by it are low and that it's not going to end the world or anything. The orb has become normal, and we've accepted that the orb is just something that kills people the same way cancer, or heart attacks, or natrual disasters, or car crashes kill people. In the nineteen eighties there were efforts to find a way to stop the orb, but it's since proven to be extremely difficult, and it's as distant and nebulous as finding a cure for cancer. When a community is struck by the orb you'll see that community in mourning, but it's not a global thing anymore.

So people grow up learning about the orb, as part of science, like anything else. A lot of gen z remembers learning about the orb from Magic School Bus. It's just something normal. There are a few people with an orb hyperfixation, and a few cults that give the orb importance but it's not most people's concern. The orb is how we first confirmed that interdimensional objects existed and are possible. A lot of people theorize dimensional studies wouldn't exist without it, meaning without the orb we might not have thermitizers or grand drives, we might not even have a moon base without the orb. Some have even rather tastelessly claimed that the orb has saved more lives at this point than its taken with all the knowledge it's given us.

Which is why I regret to inform you, that just last week, without warning, the orb killed two people in one day. And for the past seven days it's been killing two people instead of just one. Nobody knows why.

#196#worldbuilding#my worldbuilding#writing#my writing#short fiction#urban fantasy#short story#flash fiction#fantasy#unreality#alternate history#alternate universe#creative writing#writers#writer#writers on tumblr#writeblr#writers and poets#writerscommunity

7K notes

·

View notes

Text

#the constitution of the united states#the constitution#blue sky#mom was a history teacher#i am a history nerd#thats one of her 3 copies of the constitution#us current events#april 2025#izzy writes#id in alt text

11K notes

·

View notes

Text

"No one, to my knowledge, has done the kind of analysis of fiction in the 20th century that Halberstam did (first in the late 1970s, and then again in this article). Sure, there’s been a lot of writing about the history of fiction, in America in particular.

But that writing is myopic. The literary historians in the university system (including my late brother) focused on literary works or “mainstream” bestsellers, books that took over the national consciousness and led to changes and/or discussions.

....

The genres aren’t immune from the myopia. I have read as many books on the history of science fiction and fantasy as I can get my hands on, and probably just as many on the history of mystery fiction (both here and in the U.K.).

....

So, let me put this out there for graduate students in search of a topic: Examine all of fiction publishing since the 1890s or so—genres, pulps, digests, and paperbacks as well as hardcovers and “important” books. See where such an examination takes you. If nothing else, I can guarantee that your dissertation will be different than all the others."

I found Kris challenge interesting and wanted to help spread it in case someone finds it a good idea. (I'm not American so I'm probably missing a lot of context). The rest is also an interesting read.

1 note

·

View note