#proto-sinaitic script

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

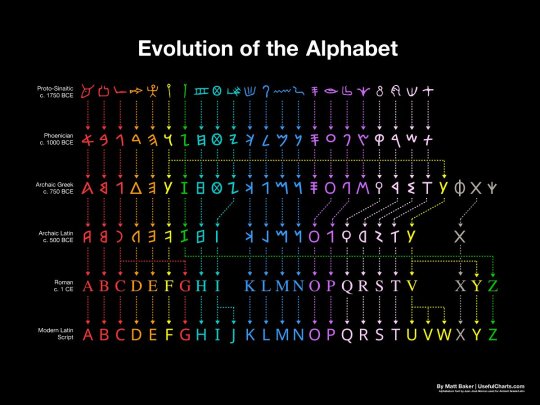

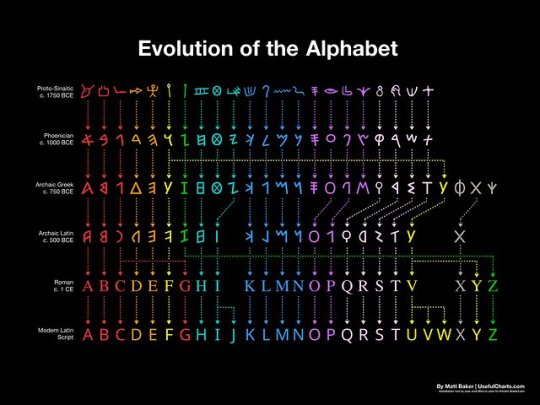

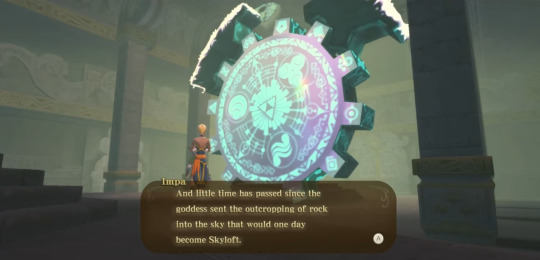

The Evolution of the Alphabet: A Story of Human Ingenuity and Innovation 🤯

How the Alphabet Changed the World: A 3,800-Year Journey

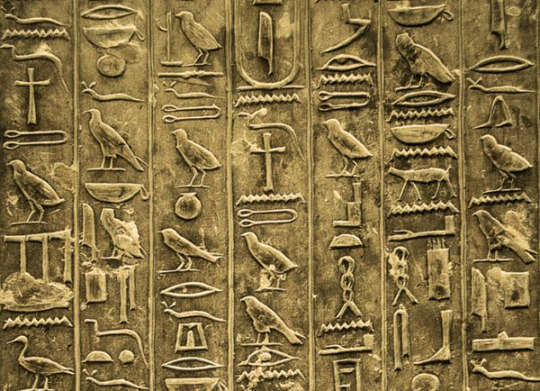

The evolution of the alphabet over 3,800 years is a long and complex story. It begins with the ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs, which were a complex system of pictograms and ideograms that could be used to represent words, sounds, or concepts. Over time, the hieroglyphs were simplified and adapted to represent only sounds, resulting in the first true alphabets.

The first alphabets were developed in the Middle East, and the Phoenician alphabet is considered to be the direct ancestor of the Latin alphabet. The Phoenician alphabet had 22 letters, each of which represented a single consonant sound. This was a major breakthrough, as it made it much easier to write and read.

The Phoenician alphabet was adopted by the Greeks, who added vowels to the system. The Greek alphabet was then adopted by the Romans, who made some further changes to the letters. The Latin alphabet, as we know it today, is essentially the same as the Roman alphabet, with a few minor modifications.

The English alphabet is derived from the Latin alphabet, but it has undergone some further changes over the centuries. For example, the letters "J" and "U" were added to the English alphabet in the Middle Ages, and the letter "W" was added in the 16th century.

The evolution of the alphabet has had a profound impact on human history. It has made it possible to record and transmit knowledge, ideas, and stories from one generation to the next. It has also helped to facilitate communication and trade between different cultures.

The alphabets are a fascinating invention that have revolutionized the way humans communicate and record information. The history of the alphabets spans over 3,800 years, tracing its origins from the ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs to the modern English letters.

Here is a brief overview of how the alphabets have evolved over time:

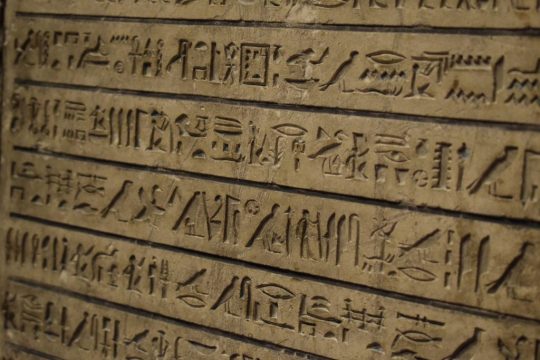

Egyptian hieroglyphs (c. 3200 BC): The earliest form of writing was the pictographic system, which used symbols to represent objects or concepts. The ancient Egyptians developed a complex system of hieroglyphs, which combined pictograms, ideograms, and phonograms to write their language. Hieroglyphs were mainly used for religious and monumental purposes, and were carved on stone, wood, or metal.

Proto-Sinaitic script (c. 1750 BC): Around 2000 BCE, a group of Semitic workers in Egypt adapted some of the hieroglyphs to create a simpler and more flexible writing system that could represent the sounds of their language. This was the first consonantal alphabet, or abjad, which used symbols to write only consonants, leaving the vowels to be inferred by the reader. This alphabet is also known as the Proto-Sinaitic script, because it was discovered in the Sinai Peninsula.

Phoenician alphabet (c. 1000 BC): A consonantal alphabet with 22 letters, each of which represented a single consonant sound. The Proto-Sinaitic script spread to other regions through trade and migration, and gave rise to several variants, such as the Phoenician, Aramaic, Hebrew, and South Arabian alphabets. These alphabets were used by various Semitic peoples to write their languages, and were also adopted and modified by other cultures, such as the Greeks, Etruscans, and Romans.

Greek alphabet (c. 750 BC): The Greek alphabet was the first to introduce symbols for vowels, making it a true alphabet that could represent any sound in the language. The Greek alphabet was derived from the Phoenician alphabet around the 8th century BCE, and added new letters for vowel sounds that were not present in Phoenician. The Greek alphabet also introduced different forms of writing, such as uppercase and lowercase letters, and various styles, such as cursive and uncial.

Latin alphabet (c. 500 BC): The Latin alphabet was derived from the Etruscan alphabet, which was itself derived from the Greek alphabet.

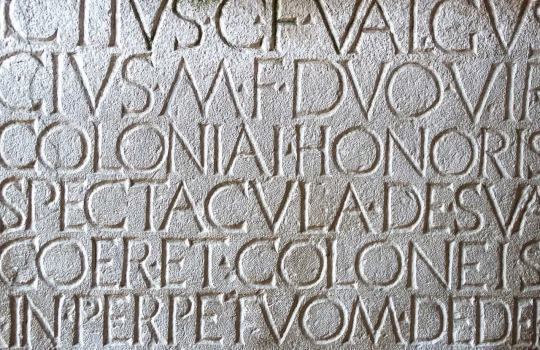

Roman alphabet (c. 1 CE): The Roman alphabet is essentially the same as the Latin alphabet, as we know it today. The Latin alphabet was used by the Romans to write their language, Latin, and became the dominant writing system in Europe after the fall of the Roman Empire. The Latin alphabet was also adapted to write many other languages, such as Germanic, Celtic, Slavic, and Romance languages.

English alphabet (c. 500 AD): The English alphabet is derived from the Latin alphabet, but it has undergone some further changes over the centuries. For example, the letters "J" and "U" were added to the English alphabet in the Middle Ages, and the letter "W" was added in the 16th century. The English alphabet consists of 26 letters, but can represent more than 40 sounds with various combinations and diacritics. The English alphabet has also undergone many changes in spelling, pronunciation, and usage throughout its history.

The evolution of the alphabet is a remarkable example of human creativity and innovation that have enabled us to express ourselves in diverse and powerful ways. It is also a testament to our cultural diversity and interconnectedness, as it reflects the influences and interactions of different peoples and languages across time and space.

Thank you for reading! I hope you enjoyed the post about the evolution of the alphabet. If you did, please share it with your friends and family. 😊🙏

#evolution of the alphabet#history of writing#alphabet#hieroglyphs#proto-sinaitic script#phoenician alphabet#greek alphabet#roman alphabet#english alphabet#language#linguistics#consonantal alphabet#syllabic alphabet#ancient egyptian#greek mythology

17 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Alphabet

The history of the alphabet started in ancient Egypt. By 2700 BCE Egyptian writing had a set of some 22 hieroglyphs to represent syllables that begin with a single consonant of their language, plus a vowel (or no vowel) to be supplied by the native speaker. These glyphs were used as pronunciation guides for logograms, to write grammatical inflections, and, later, to transcribe loan words and foreign names. However, although seemingly alphabetic in nature, the original Egyptian uniliterals were not a system and were never used by themselves to encode Egyptian speech. In the Middle Bronze Age an apparently "alphabetic" system known as the Proto-Sinaitic script is thought by some to have been developed in central Egypt around 1700 BCE for or by Semitic workers, but only one of these early writings has been deciphered and their exact nature remains open to interpretation. Based on letter appearances and names, it is believed to be based on Egyptian hieroglyphs. This script eventually developed into the Proto-Canaanite alphabet, which in turn was refined into the Phoenician alphabet. It also developed into the South Arabian alphabet, from which the Ge'ez alphabet (an abugida) is descended. Note that the scripts mentioned above are not considered proper alphabets, as they all lack characters representing vowels. These early vowelless alphabets are called abjads and still exist in scripts such as Arabic, Hebrew, and Syriac. Phoenician was the first major phonemic script. In contrast to two other widely used writing systems at the time, cuneiform and Egyptian hieroglyphs, it contained only about two dozen distinct letters, making it a script simple enough for common traders to learn. Another advantage of Phoenician was that it could be used to write down many different languages since it recorded words phonemically.

Phoenician colonization allowed the script to be spread across the Mediterranean. In Greece, the script was modified to add the vowels, giving rise to the first true alphabet. The Greeks took letters which did not represent sounds that existed in Greek and changed them to represent the vowels. This marks the creation of a "true" alphabet, with both vowels and consonants as explicit symbols in a single script. In its early years, there were many variants of the Greek alphabet, a situation which caused many different alphabets to evolve from it. The Cumae form of the Greek alphabet was carried over by Greek colonists from Euboea to the Italian peninsula, where it gave rise to a variety of alphabets used to inscribe the Italic languages. One of these became the Latin alphabet, which was spread across Europe as the Romans expanded their empire. Even after the fall of the Roman Empire, the alphabet survived in intellectual and religious works. It eventually became used for the descendant languages of Latin (the Romance languages) and then for the other languages of Europe.

Continue reading...

146 notes

·

View notes

Text

MFA Boston Returns Stolen Egyptian Child Sarcophagus to Sweden

The coffin was taken from the collection of a museum in Uppsala.

A coffin that was used to bury an Egyptian child named Paneferneb between about 1295 and 1186 B.C.E., which has been in the hands of the Museum of Fine Arts Boston since 1985, has been returned to a museum in Sweden after MFA staff discovered that the piece was stolen from the Gustavianum, Uppsala University Museum, around 1970.

The British School of Archaeology in Egypt unearthed the coffin in 1920 at Gurob, Egypt. Overseeing the dig was Flinders Petrie, who, with his wife, Hilda Urlin, excavated numerous important archaeological sites. Among his most significant finds was the Merneptah Stele in 1896; he also discovered the Proto-Sinaitic script, the ancestor of almost all alphabetic scripts, in 1905.

At the time, the Egyptian government had put in place a system of “partage,” or a division of finds, whereby it distributed the results of archaeological excavations between Egypt and the foreign parties sponsoring the digs. As part of that system, the coffin went in 1922 to Uppsala University’s Victoria Museum of Egyptian Antiquities, as it was then called. But the sarcophagus, made of pottery and measuring about 43 inches in length, went missing by at least 1970.

The coffin resurfaced in 1985, when the MFA bought it from one Olof S. Liden, who claimed to represent the artist Eric Ståhl. He presented a forged letter in which Ståhl supposedly recounted having excavated the coffin at Amada, Egypt, in 1937. Liden also presented falsified documents authenticating the coffin, purportedly from experts in Sweden. Ståhl, noted the museum in its announcement of the return of the coffin, “is not known to have participated in any excavation in Egypt.”

Curators at the MFA first smelled a rat upon finding a photograph of the coffin in the process of excavation in the 2008 book Unseen Images: Archive Photographs in the Petrie Museum, which noted that it went to Uppsala. When they noted the discrepancy, they contacted the staff at the Gustavianum, and the process of returning the piece began; the museum’s website stated that it was deaccessioned in October.

“It has been wonderful working with our colleagues in Uppsala on this matter, and it is always gratifying to see a work of art return to its rightful owner,” said Victoria Reed, senior curator of provenance at the MFA. “In this case, we were fortunate to have an excavation photograph showing where and when the coffin was found, so that we could begin to correct the record. Anytime we deaccession and restitute a work of art from the museum, it serves as a good reminder that we need to exercise as much diligence as possible as we build the collection.”

The MFA Boston’s department of the art of ancient Egypt, Nubia, and the Near East includes some 65,000 artifacts, including sculpture, jewelry, coffins, mummies, mosaics, and more, placing it among the world’s largest collections of such items, along with institutions like the Grand Egyptian Museum in Giza and London’s British Museum. The Gustavianum houses a collection of about 5,000 examples.

By Brian Boucher.

#MFA Boston Returns Stolen Egyptian Child Sarcophagus to Sweden#Egyptian child named Paneferneb#sarcophagus#ancient artifacts#archeology#archeolgst#history#history news#ancient history#ancient culture#ancient civilizations#ancient egypt#egyptian history#egyptian hieroglyphs#egyptian art#egyptian antiquities#looted art#stolen art

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

So I thought of script evolutions.

You know, first there was pictographic - you write pictures and basically charade your way through. Like writing in emojis by reading only the initial letter of what the emoji represents, 🦵🍦🦘👂 👅🔨🍦🎷.

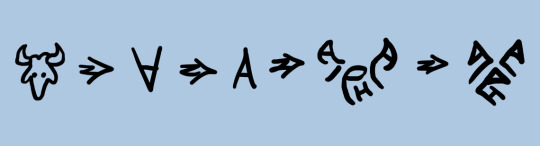

Then the letters evolve and lose their attachment to the pictographic nature (like Proto-Sinaitic -> Phoenician -> Ancient Greek/Latin).

But what if it went elsewhere, like in hieroglyphic scripts?

Say they invented a way of writing, first pictographic, then alphabetic, and with alphabetic, they wrote-out words Hangeul style in one letterspace, STYLING them to look pictographic.

Or worse, a number system appearing earlier than a writing system, and someone using it to write down stuff by counting sounds in words and then specifying further what the thing is.

Banana -> 6 sounds sequence, 3 sounds general, idk, fruit similar to the number 7. 637.

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

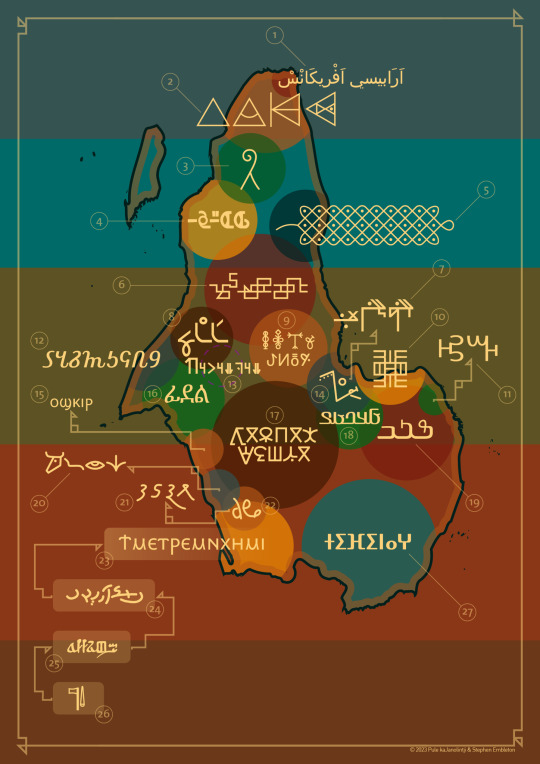

In conjunction with isibheqe.org.za this is a visual representation of various African writing systems Pule kaJanolinji and I have been working on for the past few months. A continuous work in progress. Visit their site for more information and links to the respective syllabary projects.

The map depicts the array of ancient and modern writing forms found all over the continent, and some show the branches of origins. 📜 👀 ❤️

It is included in Pule’s August 2023 presentation:

UBUCIKO BOKULOBA: African Writing Systems as Creative Cultural Technologies

In respect to the modern scripts and syllabaries, it is vital the developers of those works get the support and recognition they need to continue and to produce creative language representations.

Included here are:

1. Arabiese-Afrikaans

2. isiBheqe soHlamvu / Ditema tsa Dinoko

3. chiMbire

4. Mwangwego

5. Lusona

6. Mandombe

7. Ńdébé

8. Luo

9. Bamum

10. Adinkra

11. Vai

12. Osmanya

13. Wakandan

14. Nsibidi

15. Old Nubian

16. Ge’ez

17. Zaghawa

18. Adlam

19. N’ko

20. Proto-Sinaitic Script

21. Meroitic (derivative of Mdw Ntr)

22. Wadi el-Hol

23. Coptic*

24. *from Demotic

25. *from Hieratic

26. *from Mdw Ntr (Egyptian name for Hieroglyphs)

27. Tifinagh

13 notes

·

View notes

Note

The scripts that replaced cuneiform are also phonetic-logographic, don't you know how Egyptian hieroglyphs work? (Aka., you are displaying your ignorance on cuneiform)

What? Egyptian didn’t replace cuneiform. It was roughly contemporaneous with it, though there’s debate about which came first. Cuneiform was replaced in Mesopotamia, Asia Minor, and Persia by various abjads, alphabets, syllabaries, and abugidas, none of which were logographic, and all of which descended from the Proto-Sinaitic/Canaanite alphabet. And this was after cuneiform writing had been adapted to syllabic/alphabetic forms in Ugarit and Persia.

I don’t think there are *any* logographic scripts in west Asia or the Mediterranean outside Egypt after the decline of cuneiform. Nevermind in just the regions where cuneiform was used. What scripts are you thinking of?

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Fun fact: This process is the origin of nearly every alphabet that's ever existed! Most writing systems use syllabaries rather than alphabets, where each symbol represents a syllable (like "na") rather than a single phoneme (like "n"). Syllabaries have appeared independently all over the world, but alphabets apparently don't arise easily.

(I've heard it said that every alphabet is descended from the Proto-Sinaitic script described here, that "the alphabet has only been invented once." But I've also heard Korean Hangul, which isn't derived from Proto-Sinaitic, described as an alphabet, so I'm not really sure.)

the origin of the letter 🇦

(from the documentary The Odyssey of the Writing, 2020)

114K notes

·

View notes

Text

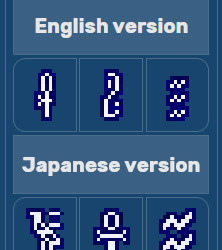

This image is a comparative chart that shows the evolution of the modern alphabet over a span of 7,000+ years across different cultures and writing systems worldwide.

It traces the development of individual letters from ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs and Semitic scripts through Phoenician, Greek, and other intermediate writing systems, culminating in the modern Latin alphabet.

Each column represents a stage in the evolution of writing, showcasing how each letter has transformed over millennia in different scripts, such as Hieroglyphics, Proto-Sinaitic, Phoenician, Greek, and Arabic, among others. The chart is a visual representation of the continuity and adaptation of characters as they transitioned from one culture to another, demonstrating the shared heritage and interconnectedness of written communication across civilizations.

The creator of this chart is Rich Ameninhat, as credited at the bottom of the image.

0 notes

Text

youtube

500 Open Tabs: episode 6 Every Dam Has Its Þ

This week Kaveh concludes the Katamari style horrors of the Johnstown flood and Hannah shares how the Europeans had their own American Idol but for letters of the alphabet instead of singers. A listener email reveals if a childhood memory was in fact cake, and how it exploded.

Originally posted on February 21, 2024. (x)

Correction: the Phoenician alphabet comes after the Proto-Sinaitic script and before the Greek alphabet.

0 notes

Text

What is the primary sacred text of Judaism? There are 24 books Judaism claims as its holy writings. They are the five books which tell of the origin of the Israelites and discuss the laws their God gave to them, the Torah (law); eight books written by or about the prophets of ancient Israel, the Neviʾim (prophets); and eleven books which contain wisdom and miscellaneous aspects of Israelite history, the Ketuvim (writings). Altogether, these books comprise the Tanakh. The Christian Old Testament as used by Protestants has the exact same content as the Tanakh, but arranges the constituent books differently and usually splits the books of Samuel, Kings, Chronicles, and Ezra-Nehemiah into two each, and the book of the minor prophets into twelve. Jews are generally uncomfortable with this name, as it implies that the Tanakh is complete without the New Testament, along with different misconceptions on how Christians have translated and presented the Tanakh, discussed below. For the rest of this FAQ, this set of books will be referred to as the Tanakh except in its capacity of a constituent part of the Christian Bible. Non-Protestant Christians include a number of books written during the Second Temple era or later in their Old Testament canons. These books are collectively known as the Apocrypha or Deutercanon, and are outside the scope of this FAQ.

What language(s) was the Tanakh written in? Almost the entire Tanakh was written in Hebrew, while parts of the Daniel and Ezra(-Nehemiah), along with words and phrases from throughout the Tanakh, were written in Aramaic.

Was Biblical Hebrew written with vowels? The Tanakh was originally written in a writing system called the Paleo-Hebrew alphabet, found in the Dead Sea Scrolls and other very early examples of Hebrew writing, and retained by the Samaritans. During the time of the Second Temple, the Jews gradually adopted a script derived from the Imperial Aramaic script, and modified it to become the square script, which is now the more familiar "Hebrew script." Both were ultimately derived from the Phoenician alphabet, and operate on similar principles, to the point where there is essentially a one-to-one correspondence. They are both technically defined as abjads rather than proper alphabets, the reason being that they lack letters whose primary use is to express vowel sounds.

Why wasn't Biblical Hebrew written using a system that clearly marked vowels? Hebrew is a member of a larger family called the Semitic languages, most of which do not have (or did not use to have) many distinct vowels. Arabic only has three, and there is no strong evidence that Akkadian had more than four. Aramaic, Ge'ez and Amharic all have at least five, and there is evidence that Ugaritic did as well, but the additional vowels in these languages do not converge the way they would if they had been inherited from a common ancestor. At the beginning of its written history, a predecessor of Hebrew, either Proto-Northwest Semitic or an immediate descendant, likely had three vowel qualities /a i u/. Its writing system, the Proto-Sinaitic alphabet, accordingly lacked vowel letters, as a given consonant sequence would have been substantially less ambiguous than in other languages with larger vowel inventories. In the stages between PNWS and Hebrew, and in Hebrew itself, a number of different sound changes caused its vowel inventory to expand, ultimately adding two, possibly three, more vowel sounds /e o (ǝ)/. As Hebrew developed, so did the variant of the Proto-Sinaitic script used to write it, albeit more slowly, giving rise to both the Paleo-Hebrew alphabet and the square script. As the written forms of a language are more conservative than their spoken forms, and the changes which brought about these additional vowels were very gradual, there was no impetus for any group of scholars to sit down and propose the addition of vowel letters to be used in writing Hebrew before it went extinct around the beginning of the fourth century. That being said, four letters, alpeh א, waw ו, he ה, and yodh י, used ordinarily to express consonants /ʔ w~v h j/, took on a secondary role of expressing vowels in variant spellings. The letters aleph and he were used for essentially any vowels, waw for rounded vowels, and yod for front vowels. In this capacity, such a letter is called an ʾem qriʾa or mater lectionis.

How do we determine the pronunciation of Biblical Hebrew if it is extinct and did not have proper vowel letters? Hebraicists rely on a number of different methods for determining the pronunciation of Biblical Hebrew words. Even though Hebrew went extinct, it was retained liturgically in Judaism, leading to three different vocalizations, the Tiberian, Babylonian, and Palestinian. During the high middle ages, a group of Jewish scholars called the Masoretes developed systems of vowel markings called the niqqud to clarify these vocalizations in Hebrew writing. Only the Tiberian vocalization survived the middle ages or was extensively covered by niqqud, and it is referenced when determining the pronunciation of Biblical Hebrew. The matries lectionis produced variant spellings of certain words, which also clarifies the pronunciation. In ancient times, a Greek translation of the Tanakh was produced called the Septuagint (abbreviated LXX). Its origins are shrouded in fable, but it is generally agreed by historians of the Bible that in the mid-third century BC, about seventy rabbis gathered in Alexandria and translated at least the Torah into Hebrew, with the rest of the Old Testament completed by the first century. As Greek is written in a proper alphabet, the vowels used in proper nouns and loanwords give insight into how these words would have been pronounced in Hebrew. Around the middle of the third century AD, a critical edition of the Tanakh called the Hexapla was produced. Consisting of six columns, it placed the Hebrew text alongside an attempt to write the Hebrew text with the Greek alphabet (in the second column, this text is called the Secunda), and four different Greek translations. Though it exists in fragmentary condition, the Secunda gives some insights into the pronunciation of Hebrew. Syllable timing can be predicted based on Biblical poetry. Finally, as it is part of a larger language family, Hebrew can be compared with other Semitic languages that have been spoken constantly since antiquity. Special emphasis is put on comparison to its closest living relatives, Aramaic and Arabic.

What is the Tetragrammaton? It is a name for God used well over 6000 times in the Tanakh, spelled using four Hebrew letters, יהוה.

Have any of the above methods been useful in determining the pronunciation of the Tetragrammaton? Judaism developed a taboo against pronouncing the Tetragrammaton during the Second Temple Period. For this reason, except for one possible exception (and even that is doubtful), no LXX manuscript presents a genuine effort to transliterate the Tetragrammaton; the only remaining fragments of the Secunda which include sections featuring the Tetragrammaton replace it with the Hebrew form amidst the Greek letters; and Tiberian vocalization lacks a pronunciation for it. In addition, all four of its letters can be matries lectionis, and it lacks known cognates in other Semitic languages. Samaritanism developed the taboo later, and a group of Jewish mystics that survived a century or so after the destruction of the Second Temple never had it. In the fourth century, Theodoret, in his Quaestiones in Exodum, records a Samaritan pronunciation of /i.a.ve/, consistent with Clement of Alexandria recording a mystic pronunciation of /i.a.we/ in the fifth book of his Stromata. Since /v/ and /w/ were never distinguished readily in any form of Hebrew, this points to a pronunciation /jah.weh/, hence the spelling Yahweh. The name "Jehovah" was an earlier rendering of the name, produced from a misconception among Christian Hebraists when encountering the Tetragrammaton in Masoretic texts. To prevent anyone from even accidentally saying the name aloud, a practice arose of saying it with the vowels in the word for "Lord," אדוני adonai. Christian Hebraicists did not realize this was a hybrid word and thought it was God's actual name, producing /ja.ho.vah/, eventually Jehovah.

Is Lashawan Qadash as promoted by various Black Hebrew Israelite groups remotely authentic to the actual pronunciation of ancient Hebrew? As with almost all other particular teachings of the BHIs, the Lashawan Qadash lacks any kind of historical evidence and is easily disproven. For example, under LQ, the name of God is not "Elohim," but rather "Alahayam." However, the first element is cognate with Arabic إله /ʔi.laːh/ and is an element of a mile-long list of different theophoric names from the Tanakh, such as Elijah, Daniel, etc, consistently spelled ηλ /eːl/ in the LXX. This points to a front vowel, both long before Hebrew became a distinct language, and towards its extinction. The second vowel is confirmed by the spelling variant which includes a waw, indicating a rounded vowel. However, the BHIs who employ LQ do not use a variant "Alahawayam." The word itself is the plural of the word "eloah" (please note that verbs always indicate grammatical number in Hebrew, and that the actions of the God of Israel are described using singular verbs in the Tanakh) which has always had a letter waw. The same plural ending shows a consistency with vowels in Aramaic plural endings. The pronunciation of the entire word is consistent with the form ελωειμ as found in the Secunda for Psalm 72:18. Black Hebrew Israelitism is usually conspiratorial, and BHIs will suggest the pronunciations of Hebrew proposed through accepted methods of historical methods are actually some kind of wicked plot perpetrated by the Jesuits, Masoretes, adherents of Babylonian mystery religion, or some combination thereof, usually in cahoots with each other. Whatever shadowy force(s) which acted to produce the pronunciation "Elohim" would have had to alter every last Hebrew scroll and carving which contains the singular "eloah," waw in tow, and every last Septuagint and New Testament manuscript containing a theophoric name containing "El" to include the letter ēta, including those manuscripts which laid in dark caves and buried in the desert for centuries; every remaining Secunda fragment to spell the name as ελωειμ; convinced millions of Arabic speakers, men, women, and children, rich and poor, to say "ilah" and write accordingly; and convinced millioned of Aramaic speakers, men, women, and children, rich and poor, to use front vowels when saying nouns in the plural, and write accordingly, centuries before anyone seriously proposed that Arabic, Aramaic, and Hebrew were related languages. This is all that would have had to have been done just to deceive the whole world of the pronunciation of just one word. There are far more words which also present a host of problems under LQ.

The existing evidence suggests that LQ originated in 20th-century Harlem, without any historical precedent whatsoever, and does not belong in any serious discussion of Biblical Hebrew.

Why is it said that Hebrew "went extinct" when it has been in constant use by the Jews until the present day? The term "extinction" in linguistics is used of languages without living native speakers. When the last native speaker of a language dies, that language is then extinct. Sumerian is extinct. Ancient Egyptian is extinct. Gaulish is extinct. Wampanoag is extinct. Ubykh is extinct. No informed person disputes any of these languages are actually extinct. However, many Jews and philosemites take offense at the term "extinction" when used to describe the ultimate fate of Biblical Hebrew. The fact of the matter is that Assyria dispersed most of the tribes of Israel, and Babylon captured what was left. We do not know what happened to the 10 lost tribes, but the members of Judah and Levi began to speak Aramaic. Even after Cyrus the Great allowed the Jews to resettle Judaea, most Jews continued to speak Aramaic and teach it to their children. Through the Second Temple Era, Hebrew went from threatened to endangered. It did not matter that Hebrew was used in the synagogues; whether a language is alive or dead is determined at the cradle rather than the altar. Bar Kochba attempted to reinvigorate Hebrew during his revolt around AD 130. After this revolt was suppressed by the Romans, any hope of Hebrew continuing were essentially dashed. The Mishnah, thought to have been among the final documents written in Hebrew during the lifetime of any native speakers, was completed around the turn of the third century, and was in a form that showed obvious changes one would expect of a language approaching extinction. There is not a shred of evidence that there were any native speakers more than a century after the Mishnah. Extinct languages find use liturgically in different religious traditions throughout the world. No Jewish person or philosemite would deny, given sufficient information, that Avestan is extinct, despite its continuing use in Zoroastrianism. Nor would they deny the same about Coptic, Latin, Ge'ez, or Sanskrit, nor would they deny that Sumerian was in use by various pagan groups as long as 2000 years after it went extinct. Yet, for these same people, it is "inaccurate" or even "bigoted" to suggest the same regarding Hebrew. The knowledge of Hebrew during late antiquity and the middle ages was restricted almost exclusively to rabbis and Jewish literati, exactly 100% of whom spoke some other language natively. Yes, Hebrew was revived during the modern period, but it took great effort in creating enough vocabulary to describe the modern world, and there are enough difference between modern and Biblical Hebrew to motivate Avraham Ahuvya to create a modern Hebrew translation (for lack of a better term) of the Tanakh. Simply put, if these people want to discuss historical linguistics, they need to use terms which are found in historical linguistics, as they are defined by historical linguistics, terms which specialists in the field, Jew and gentile, accepted a long time ago. This includes the term “extinction.”

Why don't Christians use Hebrew source texts when translating the Tanakh? They do, and have been doing so constantly since the Reformation. The printed Hebrew edition of the Tanakh, by Daniel Bomberg, was arranged from several Masoretic manuscripts collected and collated by Jacob ben Hayyim. This was the primary base text of the Old Testament in all Protestant English translations of the Bible from at least the Geneva Bible (first published 1557) up until at least the Revised Version (published 1885), and seemingly the Darby Bible of 1890 and American Standard Version of 1901. Only Catholic Bibles used the Vulgate as a source, and an obscure translation of the LXX by Charles Thompson was printed in 1808; this translation made its source clear on the title page, not that almost anyone paid attention to it. A scholar of the Tanakh named Rudolph Kittel collated an even greater set of Masoretic manuscripts, creating the Biblia Hebraica Kittel (BHK), first published 1906. Later, it was determined that a manuscript, which had been produced in Cairo, mysteriously ended in the possession of a Russian Jewish collector named Abraham Firkovich, was displayed in Odessa, and then later in St. Petersburg (later Leningrad) was in fact the oldest complete copy of the Tanakh in Hebrew. It is now known as the Westminster-Leningrad Codex, and was made the primary source of printings of the BHK from 1937 onward, and by extension the OT of the Revised Standard Version. It later became the primary basis of the Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia (BHS), first published 1968, and by extension the OT in the New American Standard Bible, New International Version, Good News Bible, New RSV, New KJV, Contemporary English Version, World English Bible, English Standard Version, and New Living Translation, just to name a few. Another printed edition of the Old Testament in Hebrew, the Biblia Hebraica Quinta, was completed last year, also derived from the WLC, and there is no reason to believe it will not serve as the basis of future translations. The LXX, Targumim, Dead Sea Scrolls, and Samaritan Pentateuch are occasionally consulted, mostly to illuminate the meaning of obscure Hebrew words or phrases, or solve inconsistencies among Masoretic manuscripts. The translators invariably place conspicuous footnotes to indicate such. If you do not believe Jewish translators of the Tanakh do the same thing, you need to explain how “amber” appears three separate times in the book of Ezekiel (1:4, 1:27, and 8:2) in the JPS Tanakh, in exactly the same places as it appears in Christian translations, despite the mystery which would surround the meaning of the base word, חשמל apart from the LXX.

#Hebrew#Hebrew language#Hebraicist#Hebraicists#Hebrew studies#Tetragrammaton#Language death#Tanakh#Old Testament#Seputagint#LXX#Dead Sea Scrolls#DSS#Targum#Targumim#Masoretes#Masoretic#Textual criticism#History of the Bible

0 notes

Text

Historical Calligraphy Scripts: A Timeless Beauty

Envision a world where the strokes of a pen immortalize cultural heritage and artistic expression — this is the realm of calligraphic art. Calligraphy, from ancient civilizations to present-day flourishes, stands as a testament to the timeless beauty of calligraphy. You, as an admirer or perhaps a practitioner, are part of a lineage that connects with calligraphy history, exploring the nuances and fine details of historical calligraphy scripts. Join us on a journey through the pages of history where the elegance of script enlightens our understanding of the past.Key Takeaways - Discover the profound historical roots and enduring allure of calligraphy art. - Experience the impact of historical calligraphy scripts on modern design and culture. - Uncover the stories behind calligraphy's progression through civilizations. - Learn about the disciplined craft that preserves the beauty of calligraphy across ages. - Appreciate the role of calligraphic heritage in shaping the narratives of history.

The Art and Evolution of Calligraphy Through the Ages

The birth of writing systems marked a revolutionary step in human civilization, allowing the communication of complex ideas across time and space. As you explore the origins of writing, you'll find that each script encapsulates the culture from which it comes, with calligraphy serving as the artistic embodiment of language.The Origins of Writing and Early CalligraphyDelving into the origins of writing, you unearth the rich tapestry of early scripts such as Sumerian Cuneiform and Egyptian Hieroglyphics, which are among humanity's earliest records. The transition from pictographs to phonetic writing, like the Proto-Sinaitic script, demonstrates how writing evolved from simple representations to complex systems of communication. - Sumerian Cuneiform began as pictorial representations and evolved over time into abstract shapes that conveyed not just objects, but syllables and concepts. - Egyptian Hieroglyphics, visually striking with their detailed depictions of gods, animals, and daily life, served both decorative and functional purposes. These ancient scripts were not merely methods of recording information but were also artistic achievements in themselves, reflecting the skills of early calligraphers. Their efforts would lay the foundation for Ancient Greek calligraphy, which would further influence the aesthetics and function of alphabetic writing.Calligraphy in the Middle Ages: Religious and Secular InfluencesThe Middle Ages invited a new era of calligraphic brilliance, where calligraphy found sanctuary within monastic walls, scripting sacred texts with divine precision. Scripts such as Gothic and Uncial crystallized the spiritual and artistic aspirations of the time, while simultaneously serving the practical needs of burgeoning kingdoms and nascent bureaucracies.The harmonious interlace of religious and secular narratives through the medium of calligraphy casts a long shadow on the cultural landscape of the era. Script Style Characteristics Usage Blackletter Calligraphy Dense, angular, and vividly textural Largely religious texts but eventually adopted for secular documents Gothic Script Stark, bold, and dramatically ornate Common in Northern European religious and intellectual texts Uncial Script Wide, rounded, and legible Used in Western European manuscripts and religious documents In your hands, each manuscript page and calligraphic example is a testament to the medieval mastery that turned everyday writing into an art form, reflecting both the divine reverence and the earthly authority of the historical worldviews. - The Blackletter Calligraphy, with its strong ties to ecclesiastical history, is still recognized as a paragon of medieval calligraphic art. - Gothic Script stands as a milestone that has shaped much of our modern interpretation of medieval aesthetics. - The clarity and elegance of the Uncial Script embodies a reverence for legibility and beauty. As these timeless masterpieces whisper ancient wisdom, you are reminded that each line and curve embodies a rich heritage of human creativity, a treasure that continues to enchant and inspire.

Exploring the Aesthetic of Gothic Script

When you think of medieval manuscripts, the striking visuals of Gothic Script likely come to mind. Being one of the most emblematic writing styles in medieval times, the Aesthetic of Gothic Script is characterized by its bold, angular lines and an almost architectural solidity. This style, known also as Blackletter Calligraphy, was not simply a way of writing but an art form that expressed the cultural and spiritual fabric of the Middle Ages.The visual density of Gothic Script's letters, with their vertical emphasis and sharp, pointed arches, captures the eye and commands attention. This was an intentional feature which made the script ideal for important religious and literary texts, symbolizing authority and tradition. The Medieval Calligraphy preserved in Gothic Script holds a sense of mystery and grandeur that continues to fascinate calligraphers and typography enthusiasts alike.Each stroke of the Gothic Script is imbued with the spirit of an age where the written word was both a divine gift and a vessel of human endeavor.Let's delve deeper into the stylistic features that define the aesthetic allure of this medieval artistry: Feature Description Textura High degree of stroke contrast and a texture reminiscent of woven fabric, lending the script its name. Quadrata Use of quadrangular shapes leading to a tightly packed appearance on the page. Batarde A hybrid script with a more rounded form, considered a more casual style of Blackletter. Rotunda Rounded form of Gothic Script used primarily in southern Europe with wider spacing and softer edges. Despite its ancient roots, the Gothic Script has left a lasting legacy that segues into modern design. Its influence can be seen in today's logos, typography, and various forms of graphic art that seek to embody a sense of history and significance. Whether through the recreation of ancient texts or the reinterpretation of the style in contemporary designs, the Aesthetic of Gothic Script continues to leave an indelible imprint on the canvas of art and design. - The pointed arch and linear precision in Gothic Script bring a dramatic flair to calligraphy. - Aesthetic of Gothic Script evokes a medieval ambiance, often used to complement historical and fantasy themes. - Blackletter Calligraphy is a striking choice for modern branding seeking a classic, authoritative feel. As you admire Gothic Script's aesthetics, remember you are not just looking at letters on a page, but also at a narrative — the story of a world that revered the written word and celebrated it through the beauty of Medieval Calligraphy.

The Elegance of Italic and Copperplate Scripts

Imagine gliding your pen across a canvas, conjuring words adorned with the refinement of Italic Script and the sophistication of Copperplate Script. These calligraphic styles, which flourished during the Renaissance Calligraphy period, encapsulate the very essence of artistic elegance and communicate it through each meticulously crafted curve and line. With the guidance of Laura Lavender's instructional resources, you can delve into the nuanced world of these scripts, shaping your calligraphic journey with finesse.Graced with a rich lineage, the Italic Script stands as a hallmark of the Elegance of Calligraphy, renowned for its angled strokes and cursive flow. On the other hand, Copperplate Script, with its exquisite loops and fine flourishes, impressively demonstrates a timeless allure that continues to captivate the hearts of calligraphy enthusiasts.The grace of Italic and the precision of Copperplate come together to form a calligraphic dance that is as mesmerizing to watch as it is to execute.As you explore these scripts, it becomes evident that their beauty is not merely in their visual appeal but also in their versatility. - Italic Script can be both casually inviting and formally impressive, making it ideal for a range of contexts from personal letters to official documents. - Copperplate Script, with its refined beauty, is often reserved for the most special of occasions and projects—such as wedding invitations and certificate inscriptions. Below, you'll find a table contrasting the characteristics of Italic and Copperplate scripts, offering insight into their distinct features and historical contexts: Script Style Features Historical Context Italic Script Slanted, cursive style with loops and variable stroke weight Originating in the Renaissance, it brought legibility and fluidity to European script. Copperplate Script Even spacing, formality, and a focus on intricate curves and flourishes Developed in the 16th century, it became popular for its ornate appearance and precision. Copperplate Script particularly stands as a testament to the Elegance of Calligraphy. It requires discipline and practice, but with dedication, you could possess the skill to create art that resonates with the grandeur of bygone eras.Employing tools designed by artists like Laura Lavender, you have the opportunity to immerse yourself in the world of Renaissance Calligraphy and carry its legacy forward. Whether your interest lies in constructing personal masterpieces or contributing to the cultural fabric through your scriptwork, the journey of learning and perfecting Italic and Copperplate scripts promises a fulfilling path.

Blackletter Calligraphy: A Testament to Medieval Mastery

The visual language of the Middle Ages is encapsulated in the dramatic and textured strokes of Blackletter Calligraphy. As you trace the paths of ink across vellum, you'll find that these Medieval Manuscript Scripts are not just forms of writing but are, indeed, artworks that echo the cultural ethos of an era defined by meticulousness and grandeur. Let's delve into the distinctive Characteristics of Blackletter, which make it so timeless and revered.Understanding the Characteristics of BlackletterBlackletter, also referred to as Gothic Script, is renowned for its dense and angular appearance; a stark contrast to the rounded scripts of contemporary handwriting. Each letter stands like an architectural pillar, with bold vertical strokes and elaborate embellishments. Historically, its practical application varied from religious texts to proclamations of law, owing to its authoritative presence on the page.Within the vast confines of medieval scriptoriums, scribes labored to produce manuscripts that stood as testaments to their mastery. The distinct appearance of Blackletter was their hallmark.Among the various forms of Blackletter, the Fraktur Script gained prominence, particularly in the German-speaking regions, showcasing an evolution of the traditional Gothic aesthetic with its broken lines and added complexity. To grasp the essence of Blackletter's artistry, observe these defining features: - Heavy use of straight, narrow edges producing a woven, textured look - Genesis in the 12th century, reaching prominence in the later Middle Ages - Compilation of Fraktur and Textualis forms, each with unique attributes but united by a common aesthetic Emblems of power and piety, these characters illustrate a page with an intensity that captures the solemn spirituality and earnest governance of the times.The Influence of Blackletter on Modern TypographyToday, the legacy of Blackletter Calligraphy extends its roots into the field of Modern Typography. Although the script is no longer a staple in everyday writing, its visual impact remains a source of inspiration for designers and artists worldwide. Gothic Script continues to be synonymous with solemnity and formality, making it a popular choice for ceremonial occasions and branding that seeks to evoke a classic and powerful image. Blackletter Style Modern Usage Traditional Gothic Logos, music industry, branding Fraktur Publishing, decorative text Textualis Diplomas, formal invitations Schwabacher Historical reenactment, role-playing games Digital technologies have allowed Blackletter to be more accessible, with typefaces influenced by Gothic Script being utilized in contemporary contexts around the globe. Though the pens and the parchment may have changed, the impact of Medieval Calligraphy prevails, inviting you to marvel at the prowess of past artisans, whose legacy continues to shape the contours of today's design and cultural artistry.

The Renaissance Influence on Calligraphy Styles

The cultural rebirth of the Renaissance era played a pivotal role in the evolution of Western calligraphy. As you explore Renaissance Calligraphy, you'll discover an aesthetic driven by a return to classicism and a burgeoning emphasis on clarity and form. It was during this period that Humanist Minuscule emerged, a script characterized by its rounded characters and increased legibility, evoking an elegance that would profoundly influence the development of modern Cursive Script.These shifts reflect not merely stylistic preferences but also cultural transformations, where humanism fostered an environment ripe for Calligraphy Evolution. The humanist scribes, in their quest for clarity and beauty, delivered a writing style that balanced artistic expression with functional readability, which has since cascaded through time into our contemporary alphabets.The elegance and legibility of the Humanist Minuscule offered a visual clarity that echoes through the corridors of time, influencing the cursive hand of today.Let's delve into the distinctive traits that defined Renaissance calligraphic styles: - The drive for classical learning reintroduced the precise and unadorned Caroline Minuscule, which Humanist Minuscule would later refine. - Humanist Minuscule favored narrower letterforms and a more upright position than its medieval predecessors, reflecting the Renaissance ideal of harmony. - Cursive Script gained popularity for its efficiency, flowing smoothly from one letter to the next, ideal for rapid writing. To map the transformative journey of calligraphy during the Renaissance, the following table juxtaposes key attributes of medieval scripts against those of the emerging Renaissance calligraphy styles: Attribute Medieval Script Renaissance Script Proportion Irregular and complex More uniform and geometric Legibility Varied greatly based on context and style Enhanced for ease of reading Aesthetics Often ornate with intricate embellishments Simpler forms with a focus on balance and proportion Orientations More angular and vertical More horizontal and aligned Adoption Primarily for religious and authoritative texts Broadened to include humanist literature and secular texts Indeed, orating the history of calligraphic art without lauding the Renaissance would leave the narrative incomplete. It was an era that heralded an intellectual effervescence, redefining artistic norms and charting a new course for Calligraphy Evolution. Through the mingling of pen and parchment, the era's scribes etched a legacy that continues to shape our interpretation and practice of calligraphy, marrying the artistry of the past with the flowing communication needs of the present.

Islamic Calligraphy Scripts: A Fusion of Art and Devotion

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uL6Yo9qKAZQAs you trace the elegant strokes and intricate patterns of Islamic Calligraphy Scripts, you become intertwined with a spiritual and artistic tradition that has captivated the Muslim world for centuries. Arabic Calligraphy Styles have evolved over time, diversifying into several forms, each with its own aesthetic and function. Among them, Naskh, Thuluth, Diwani, and Kufic Script stand out as quintessential examples of Islamic Art. These scripts are more than mere writing; they represent a devout fusion of beauty and worship in Islamic culture.Let's explore the distinctive characteristics of each script style and their role in Islamic art: Script Style Characteristics Use in Islamic Art Naskh Clear and legible with thin lines and small curves Widely used in printing the Quran and other religious texts Thuluth Elegant and elongated, with generous vertical proportions Decorative purposes on buildings and in traditional artwork Diwani Flowing and intricate with overlapping strokes Historical significance for official documents and correspondence Kufic Script Geometric, with angular lines and square or rectangular shapes Architectural ornamentation, especially on mosque walls Naskh script, for instance, is highly revered for its clarity, making it the perfect choice for scribing the holy verses of the Quran, where every word must be precisely conveyed. In contrast, Thuluth script is often preferred for its majestic appearance, enhancing the walls and domes of mosques with its timeless grandeur.Through the harmonious curvature of Diwani, you can witness the intertwined legacy of Islamic governance and art, while the Kufic Script draws you into its labyrinth of geometric shapes, reflecting the meticulous nature of Islamic architectural design. - The flowing grace of Arabic Calligraphy Styles has the power to move both the heart and the spirit. - Contemplating the mastery of Naskh reveals the meticulous care given to the transcription of divine words. Read the full article

0 notes

Photo

#Phoenician#Archaic Greek#Archaic Latin#Roman#Modern Latin Script#Alphabet#Latin Alphabet#Proto-Sinaitic

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

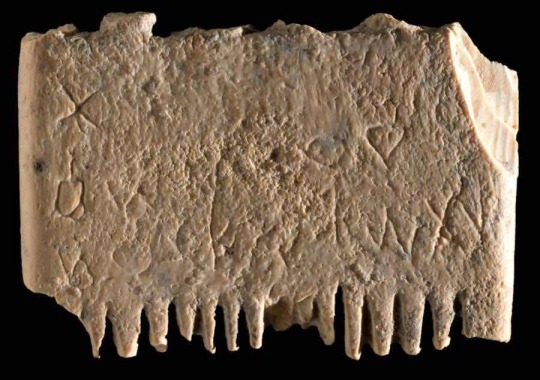

A very special comb.

Considering the very recent announcement coming from Tel Lachish I thought I’d write a little about what this discovery means in terms of the history of writing in the Near East, and Canaan specifically.

In the 2016 June-July archaeological season an ivory comb was discovered and put into storage (standard practice, it takes years to go through finds). It was only re-examined recently, and an inscription was found, the inscription, a spell of protection against lice was possibly written circa 1700 BCE. The inscription reads "May this tusk root out the lice of the hair and the beard.” The teeth of the comb even had the remains of lice nymphs, this comb was used for the purpose given.

But that, whilst cool is not why we are so excited.

What makes this comb particularly special is what language this inscription was written in, and the proposed date.

The comb (if this date is correct) is the oldest example of the Proto-Sinaitic script, it is also the earliest full sentence of this writing system found in Israel. This writing system has so few examples that it is a running joke whenever the “Australians” join a dig that we will write the alphabet on a rock and joke about it being the greatest find ever. It was one of the jokes pulled by a friend of mine at this exact dig.

Now we seemingly not only have proof that this was more than a few letters and names that Canaanites were playing around with at the time, but we now have a solid example of Canaanites using their own alphabet in daily life during the Middle Bronze Age in Canaan proper, a time where the most prevalent script was Akkadian Cuneiform.

The timeline for Proto-Sinaitic script is not well established (very few examples of this script exist, and nothing from the early phases) but the consensus is that this script was invented by Canaanites in Egypt circa 1800 BCE. However, there are some doubts as to whether the script really arose in Egypt, or the Hyksos homeland. What we do know is this alphabet, the first in existence and the basis for our current writing system, was greatly influenced by Egyptian hieroglyphics. We only had a few words, and a few letters dating from this early period, the thought was that, because most of the substantial examples of the Proto-Sinaitic script date from the 13 century BCE onwards, that it was not really used prior to the early Iron Age, after the Akkadian Cuneiform writing system went into disuse due to the Bronze Age collapse. Anything before the 13th century BCE is either poor in quality or removed from its original context (makes dating the text harder). All pre 13th century BCE inscriptions were single letters or words.

Enter Tel Lachish and this ivory louse comb, Lachish was a major city state during the Second Millennium BCE and is where most of these Proto-Sinaitic inscriptions were found, if any writing dating earlier than the Iron Age exists, it’s at this site. The existence of this comb, found at the highest point of the site (where you typically find both public buildings and elite homes) tells us that firstly, Lachish was importing ivory from Egypt and making these combs in the same style as those found during the Second Intermediate Period (the comb is double sided as opposed to the more traditional Canaanite one sided comb), and that our scribe was not great at writing in a confined space. The letters are increasingly smaller and more squished as they go along. It also suggests that the wealthy were learning to write their own language in their own script, alongside Akkadian Cuneiform.

The comb being used for lice removal tells us that Canaanites were using their own language and their own writing system at home at least for ritual purposes, something we also see in Egyptian and Hittite cities, and its use may have been more commonplace than initially though. From what we know about our Iron Age examples, Proto-Sinaitic script was mostly written on perishable materials with ink (Lachish is moist as anything and the soil is incredibly fertile, not a great preserver of papyri or ink).

Why is this important? Akkadian Cuneiform was the major form of international writing during the Middle to Late Bronze Age and was used from Babylonia to Egypt, Canaan to Anatolia, and all the way to Iran. The Amarna Letters, a collection of correspondence between the pharaohs of the late 18th Dynasty and their Canaanite constituents were written in this international script, a script mostly written with a reed stylus on clay or carved into stone stele. The thought that Canaanites may have had two writing systems makes a lot of sense when you take this international correspondence into context, Egypt won’t write to Canaanite kings in hieroglyphs or hieratic script, Hittites won’t communicate using Luwian cuneiform of hieroglyphs, those are specifically liturgical languages.

What this find tells us if the 1700 BCE date is true (the layer it was found in has an Early Iron Age date, which complicates everything), is that Canaanites were using their own alphabet for ritual purposes at least 400 years earlier than what we initially thought.

#I wrote this for the Bronze Age table top games i'm working on#I'm both a concept artist and the Near Eastern Historical consultant#I do bronze age digos#archaeology#history#bronze age

62 notes

·

View notes

Text

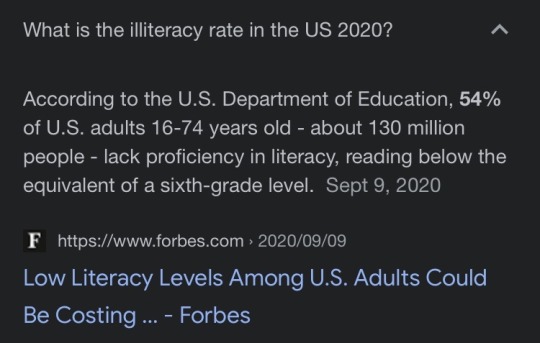

How can ppl who only speak English still be unable to differentiate between “their” “they’re” and “there.” Or write “cookies” for example as “cookie’s.” Bad syntax & grammar is such a turn off like Wtf is going on in the brain dead Anglosphere. Whenever I wonder why ppl are so stupid and gullible these days I recall this stat and everything makes sense:

I mean bro unless someone has a legitimate reading disability or it’s their second language they should not struggle with Latin script it’s like the easiest one in existence. Chinese and Slavic alphabet readers are just looking at dumb Anglos like 👀 Like how are North Americans gonna be racist to the whole world yet that low iq.

When I was young my parents forced me to go to Sikh Sunday school and I hated them for it but without it I wouldn’t have been able to read Gurmukhi script. Learning a strange Proto-Sinaitic alphabet suddenly made English look so simple in comparison:

I’m lucky that my family emphasized I learn multiple languages because it’s so important towards development and critical thinking skills. I love that I can think and read in other languages and I can’t imagine only knowing one and poorly at that! So whenever anyone is racist towards me idgaf bc I’m happy to have a rich cultural background I can’t imagine life without it.

59 notes

·

View notes

Note

By Hylia, TELL ME about your Mudora theory!

THIS POST CONTAINS HEAVY SKYWARD SWORD SPOILERS

I MEAN HEAVY

READ AT YOUR OWN RISK

The Book of Mudora is an item you get in A Link to the Past.

Looks a lot like Hyrule Historia, doesn't it?

The Book of Mudora is, according to the ALttP manual, "a collection of Hyrule legends and lore," that contains stories about the Triforce. In-game, its use is in tranlating the game's Hylian script.

Unlike all other Zelda games, its script doesn't translate into Japanese or English, instead having three unique glyphs depending on which localization you play.

But why? Why is this particular script so unintelligible?

My theory is that Mudoran Hylian is the very first iteration of Hylian, from before even Skyward Sword.

As far as language goes, plenty of languages tend to start out as logographies (hieroglyphic systems) before they turn into simpler, easier to write markings. Look at the Latin alphabet, for example.

The Proto-Sinaitic pictures up at the top got progressively simplified into the Greek alphabet, then turned into Archaic Latin. The reason Roman Latin looks so crisp and clean is because they started carving these letters into stone. The serif (the little stroke at the ends of the lines) is a chisel mark.

Given how similar Mudoran Hylian is to Egyptian hieroglyphs, we can make that connection and say that Hylian started out the same way.

HEAVY SKYWARD SPOILERS BELOW

Skyward Sword has a LOT of architecture in it. Despite it being the first Zelda game, before Hyrule was ever established, we find ruins of ancient civilizations.

A cistern so good at purifying water that the impurities of it creates the world’s first redead-esque monsters. It contains mechanical wonders like Koloktos and the elevators, and marvels of plumbing and watercourses all throughout.

Colorful palaces capable of channeling LAVA. The kind of structural integrity this would have to have, and the Fire Sanctuary is almost completely untouched by ruin!

Factories! Circuitry! Usage of stones that literally CHANGE TIME, as an integral mechanic!

Even Skyview Temple has a working water system, despite everything, and contains the best item Zelda’s ever come out with.

The civilization that came before Hyrule was ADVANCED. Insanely so. Using everything from AI to magic, these people knew how to fully take advantage of the world the goddesses left them, perhaps even through use of the Triforce.

Back to Mudora.

Although plenty of stuff on the surface uses Skylian text, mostly as easter egg content from the Zeldevs, you can find a lot of designs in Lanayru that capture interest.

Particularly this marking on the ground at that one roller coaster island in the sand sea.

The swirly marks here aren’t seen anywhere else, to my knowledge, and they look a lot like the cover of the Book of Mudora.

Now, why Mudora? Why is it called Mudora?

It doesn’t mean anything in English. And it’s the same name it has in source Japanese.

ムドラの書 | Mudora no Sho

Which, I checked; also doesn’t mean anything different from English.

Here’s the thing. The Surface is nameless. We know it’s later called Hyrule, and that’s derived from Hylia; if it was named that before, Impa or Fi would have called it such. And it had to have had a name before the tragedy of war struck it down.

So, my theory is that Mudora is the name of the world before the Battle of Demise.

When the demons broke free of the ground, Mudora must have been THRIVING. Automatons! Port cities! Dragon nobility, the Triforce itself being a well-known treasure! All of that lost in the destruction that followed.

When Hylia sent humanity skyward, it was her last resort. Almost everyone had perished in the war.

Demise even brags about that conquest.

But...that time also had a hero.

Originally, I thought that this was a time loop; that the legends were about Link and Zelda, just post Gate-of-Time and passed down through legends. However...

By the time you get there, Skyloft is long gone.

They wouldn’t have known about you.

So the first hero, the original hero, was the champion of Mudora. We don’t know what happened to them, but we know that, from Demise’s dialogue, the two never faced each other.

They may have lived a hundred years before Demise, for all we know.

But they existed.

#loz#zelda#my MUDORA THEORY HI#I HAVE BEEN WAITING TO TALK ABOUT THIS#skyward sword spoilers#THAT TAG IS VERY IMPORTANT#skyward sword#mudora#now. the real question. do i make linked universe mudoran hero a girl. because i am tempted#theories#worldbuilding#headcanons#analysis#ask bee#THANK YOU FOR ASKING I LOVE THIS

962 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Colorful Chart Reveals Evolution of English Alphabet From Egyptian Hieroglyphics

Most of us use the letters of the alphabet everyday, but did you ever stop to wonder how their shapes came to be? The history of the alphabet is fascinating, and each of the 26 letters has its own unique story. Matt Baker (of UsefulCharts) has designed a handy poster that documents the evolution of our familiar alphabet from its ancient Egyptian Proto-Sinaitic roots (c. 1750 BCE) up to present day Latin script.

The limited edition Evolution of the Alphabet chart shows how early shapes and symbols eventually morphed to become the ABCs we know today. While some letters are recognizable quite early on, others have little resemblance at all. The letter “A” for example, began as an Egyptian hieroglyphic that looks like an animal head with horns. Through Phoenician (c. 1000 BCE), early Greek (c. 750 BCE), and early Latin (c. 500 BCE) periods, the lines that made “A” eventually simplified to become the symbol we know today...

Read more: https://mymodernmet.com/history-of-the-alphabet-usefulcharts/

#alphabet#writing#history#history of writing#language#linguistics#elnglish language#english#anthropology#archaeology#ancient egypt#ancient rome#Rome#world history#ancient greece#Phoenecia

61 notes

·

View notes