#culinary history of african american cooking

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

youtube

Race in America: Black Culinary History with Stephen Satterfield and Jessica B. Harris

“High on the Hog” is a new docuseries about Black culinary history. Based on the seminal book of the same name by Jessica B. Harris, it follows the host Stephen Satterfield as he travels from West Africa to the Deep South. On Wednesday, July 14 at 3:00pm ET, Satterfield and Harris join opinions columnist Michele Norris to discuss how African American food has shaped our culinary landscape and offers a lens into larger questions about our country’s history.

#Youtube#Race in America: Black Culinary History with Stephen Satterfield and Jessica B. Harris#Black Culinary History#food#Blacks in food#Black cooking#culinary history of african american cooking#soul food

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

🍲Black food history

:1. Fried Chicken: Originated in West Africa, brought to Americas by enslaved people

.2. Gumbo: African, French, and Indigenous fusion dish from Louisiana.

Barbecue: African and European influences merged in Southern BBQ.

Soul Food: Post-Civil War cuisine developed by African American women.

Juneteenth: Celebratory foods like red velvet cake, strawberry soda.

African Diasporic Cuisines: Caribbean, Latin American, African American.

Foodways of Enslavement: Cooking techniques, ingredients.

Freedom Food: Post-Emancipation culinary innovations.

The Black Chef''s Movement: Modern culinary activism.

Black Food Culture Preservation: Efforts to document, celebrate heritage. 🍲Books:

"High on the Hog: A Culinary Journey from Africa to America" by Jessica B. Harris

"Soul Food: The Surprising Story of an American Cuisine" by Adrian Miller

"The Oxford Companion to American Food and Drink" by Andrew F. Smith 🍲Documentaries:

"The Search for General Tso"

"Soul Food Junkies"

"The African Americans: Many Rivers to Cross" 🍲African American culinary contributions are vast and diverse, reflecting the community''s rich cultural heritage. Here are some key aspects: 🍲Traditional Dishes

Fried Chicken

Barbecue (ribs, brisket, etc.)

Gumbo

Jambalaya

Soul Food (mac and cheese, collard greens, etc.)

Cornbread

Red Velvet Cake

Sweet Potato Pie 🍲Culinary Influences

African (fufu, jollof rice)

Caribbean (jerk seasoning, curry)

Southern American (biscuits and gravy)

European (French, Spanish, Italian) 🍲Historical Context

Slavery: Enslaved Africans brought culinary traditions.

Reconstruction: Freedmen established restaurants, food businesses.

Great Migration: African Americans introduced Southern cuisine to urban centers. 🍲Iconic Figures

Abby Fisher (first African American cookbook author)

Nat Fuller (renowned chef, Charleston)

Edna Lewis (celebrated chef, author)

Leah Chase (legendary New Orleans chef) 🍲Modern Contributions

Innovative chefs (e.g., Marcus Samuelsson, Carla Hall)

Food media (e.g., "Soul Food Junkies," "High on the Hog")

Food festivals (e.g., Essence Food Festival)

Food justice movements (e.g., Soul Fire Farm) 🍲Regional Cuisines

Southern (e.g., Lowcountry, Cajun)

Caribbean-American (e.g., Haitian, Jamaican)

West Coast (e.g., California soul food)

Midwestern (e.g., Detroit-style soul food) 🍲Books

"The Oxford Companion to American Food and Drink" by Andrew F. Smith

"Soul Food: The Surprising Story of an American Cuisine" by Adrian Miller

"High on the Hog: A Culinary Journey from Africa to America" by Jessica B. Harris 🍲Documentaries

"The Search for General Tso"

"Soul Food Junkies"

"The African Americans: Many Rivers to Cross" 🍲Websites

The Southern Foodways Alliance

Black Food Studies

The Food and Culture Exchange

#Black history#black liberation#black community#black power#black people#black culture#black history 365#black history matters#black history is american history#black history is world history#black history month

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

second third of 2024 in books

23. Don't Look at Me Like That, Diana Athill [I brought this book on a trip and loved it; it was the perfect vacation companion] 24. Cahokia Jazz, Francis Spufford [I know I wrote my thoughts out at the time but. lovely! frustrating!] 25. To Paradise, Hanya Yanagihara [you all know already which section was my favorite] 26. Catch-22, Joseph Heller [obviously I've Gone On about it but. god.] 27. Slaughterhouse-Five, Kurt Vonnegut [reread] 28. All-Of-A-Kind Family, Sydney Taylor [reread, but not since childhood] 29. "The Good War," Studs Terkel [reread] 30. Coming Out Under Fire: The History of Gay Men and Women in World War II, Allan Bérubé [mostly a reread? I'm not sure I'd ever read it cover to cover before] 31. Looking for the Good War: American Amnesia and the Violent Pursuit of Happiness, Elizabeth D. Samet 32. What Soldiers Do: Sex and the American GI in World War II France, Mary Louise Roberts 33. HHhH, Laurence Binet (trans. Sam Taylor) [did I like it? unclear! was I fascinated by it? absolutely.] 34. Once There Was a War, John Steinbeck 35. X Troop: The Secret Jewish Commandos of World War II, Leah Garrett 36. Cosmopolitans: A Social and Cultural History of the Jews of the San Francisco Bay Area, Fred Rosenbaum 37. More All-Of-A-Kind Family, Sydney Taylor [reread] 38. The Cooking Gene: A Journey Through African American Culinary History in the Old South, Michael W. Twitty

#yes there is an element of humor to this list. yes you may laugh.#wow might i be working through some kind of ''obsession''#books tag#i realized a few days ago that i hadn't read a novel written for adults since JUNE so that has now been rectified

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Southern Food Heritage Day

Every year, Southern Food Heritage Day is celebrated on October 11. The Southern Food & Beverage Museum celebrates the culturally rich and delicious food of the Southern States in America. The cuisine deserves to be recognized and celebrated officially because it is a testament to American history and legacy. Southern food also represents the essence of America — the coming together of a variety of people from all over the world, each bringing with themselves their own ingredients and recipes to create a unique cuisine. Iced tea, pickled shrimps, and fried chicken are some of the most loved Southern foods throughout history. Along with the cuisine, the day also celebrates the racial and ethnic diversity in America.

History of Southern Food Heritage Day

Southern Food Heritage Day celebrates the best that Southern food and beverages have to offer. The South’s cuisine in America can be found in the historical regional culinary form of states generally south of the Mason-Dixon line dividing Pennsylvania and Delaware from Maryland, along the Ohio River, and extending west to southern Missouri, Oklahoma, and Texas. The most notable influences on Southern cuisine are African, English, Scottish, Irish, German, French and Native American.

The food of the American South displays a unique blend of cultures and culinary traditions. The Native Americans, Spanish, French, and British have contributed to the development of Southern food, with recipes and dishes from their own cultures. Food items such as squash, tomatoes, corn, as well as certain cooking practices such as deep pit barbecuing, were introduced by south-eastern Native American tribes such as the Caddo, Choctaw, and Seminole. Many foods derived from sugar, flour, milk, and eggs have European roots. Black-eyed peas, okra, rice, eggplant, sesame seed, sorghum, and melons, along with spices, are of African origin.

Southern food can be further divided into categories: ‘Soul food’ is heavily influenced by African cooking traditions that are full of greens and vegetables, rice, and nuts such as peanuts. Okra and collard greens are also considered Soul Food, along with thick stews. ‘Creole food’ has a French flair, while ‘Cajun cuisine’ reflects the culinary traditions of immigrants from Canada. ‘Lowcountry’ cuisine features a lot of seafood and rice, while the food of the Appalachians is mostly preserved meats and vegetables. Southern food is partial to corn, thanks to the Native American influence.

Southern Food Heritage Day timeline

1860

Southern Diet Expands

Following the emancipation from slavery, the Southern diet becomes versatile.

1916

The Great Migration

African Americans travel from rural communities in the South to large cities in the North and West — they carry their cuisine with them.

1940s

Southern Foods in Restaurants

Southern foods start appearing on restaurant menus and appeal to a diverse clientele.

1964

Soul Food

This term, describing everyday Southern food, first appears in print.

Southern Food Heritage Day FAQs

What is the difference between Southern food and soul food?

The difference between soul food and Southern food is rooted more in class than race, and what families were able to afford to put on the table.

What is a typical Southern meal?

A traditional Southern meal is pan-fried chicken, field peas, greens, mashed potatoes, cornbread or corn pone, sweet tea, and a pie for dessert.

Why is Southern food so unhealthy?

The Southern diet is commonly high in processed meats, which are high in salt and in nitrates, which are in turn linked to heart risk. The high sugar content of the diet may also lead to negative effects, like insulin resistance and inflammation.

How To Celebrate Southern Food Heritage Day

Organize a cook-off: Gather all your friends and organize a cook-off on Southern Food Heritage Day. Revive old recipes or add a twist to create something new.

Go out for a meal: Enjoy the best of Southern foods at your favorite Southern foods restaurant. Don’t forget to enjoy the classics like fried chicken, hush pies, and pies.

Set up a barbecue: Barbecues are an integral part of the Southern food heritage. It is also one of the most popular styles of cooking. Barbecue your favorite meats and vegetables, and serve them with sauces and seasonings.

5 Facts About Southern Foods That Will Blow Your Mind

Redeye gravy has a unique recipe: Redeye gravy is made with pan drippings and leftover coffee.

It is more calorie-dense: Southern fried chicken breast typically has more than 400 calories in an ounce.

Peanut butter is an essential: Half the annual crop of peanuts is used to make peanut butter.

Collard green has been around forever: It’s been a part of our diet for more than 2,000 years.

Black-eyed peas are also good luck charms: It is believed that black-eyed peas bring good luck on New Year’s Day.

Why We Love Southern Food Heritage Day

A day to indulge: You cannot celebrate Southern Food Heritage Day without enjoying a hearty meal of your favorite foods. This is truly a day of indulgence!

Try something new: The best thing about Southern food is that it has something for everyone. Use this day to try a new food item or the cuisine of Southern heritage. Who knows, you might just discover your next favorite dish!

It is historically significant: Southern foods have a rich cultural and historical significance. Learn more about the origins of your favorite foods on Southern Food Heritage Day.

Source

#Peach Blackberry Cobbler#Peach Pie#Fried Chicken Sandwich#ice tea#Fried Chicken#collard green#Okra stew#Southern Food Heritage Day#USA#soul food#original photography#travel#vacation#restaurant#SouthernFoodHeritageDay#Coconut Cake#Shrimp and Grits#Hot Sausage Po'Boy#candied yam#Florida Gator Tail#Gumbo#Jambalaya#Pecan Pie#Chicken Fried#corn cob#Baby Back Ribs#11 October

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Culinary Cousins: Louisiana's Culinary Kaleidoscope of Cajun and Creole

Welcome back to our Louisiana kitchen, cher! Let’s delve into a topic close to my heart – the captivating world of Cajun and Creole cuisines. While these two culinary traditions share the same vibrant home, there are nuances that make each one a unique celebration of flavor.

Similarities

Most cousins share some traits and us Cajuns and Creoles? Well, now, we aren’t that different.

Rich Heritage Both Cajun and Creole cuisines are born from the rich cultural tapestry of Louisiana. They intertwine elements from French, Spanish, African, and Native American traditions, creating a delicious mosaic that reflects our diverse history.

Holy Trinity The "Holy Trinity" – a medley of bell peppers, onions, and celery in the heart of both cuisines. This aromatic trio serves as the flavor foundation for many dishes, providing depth and character to Cajun gumbos and Creole étouffées.

Rice Is A Staple Rice is a fundamental component in both Cajun and Creole cooking. Whether it's a bed for gumbo or jambalaya or a side dish, rice ties these culinary traditions together.

Differences

Everyone has their differences, even something as small as ordering a Dr. Pepper instead of a Big Shot. (It happens.)

Geographic Roots One key distinction lies in their geographic roots. Cajun cuisine hails from the rural areas of Louisiana, particularly the Acadiana region, while Creole cuisine originates in the urban centers, primarily New Orleans.

Influences and Ingredients Cajun cuisine often leans towards heartier, rustic fare with influences from the French countryside. Game meats, seafood, and ingredients like andouille sausage are staples. On the other hand, Creole cuisine showcases more refined flavors, often incorporating tomatoes, fine herbs, and a variety of spices.

Cooking Techniques The cooking techniques also set them apart. Due to their rural roots, Cajun dishes are often one-pot wonders simmered to develop robust flavors. In Creole cuisine, you might find more intricate sauces and delicate preparations, showcasing the finesse of French culinary techniques.

Global Influences in Creole Being born in a melting pot like New Orleans, Creole cuisine has been influenced by a broader array of international flavors. Spanish, African, Caribbean, and Italian influences are more pronounced in Creole dishes, offering a diverse and eclectic culinary experience.

In the end, both Cajun and Creole cuisines share a love for bold, flavorful dishes that bring people together. Whether you're simmering a gumbo on the bayou or enjoying a Creole-inspired feast in the heart of New Orleans, you're partaking in the magic of Louisiana's culinary heritage.

Jambalaya: A Culinary Symphony

The iconic Jambalaya is one dish that is beloved by both Cajun and Creole communities. Jambalaya reflects the diverse cultural influences and rich culinary heritage of Louisiana. While there may be variations in the recipes between Cajun and Creole versions, the heart of the dish remains a shared love for bold flavors and hearty, one-pot creations.

Cajun Jambalaya

Ingredients Typically, it includes andouille sausage, chicken, and sometimes game meats like rabbit or alligator. It's seasoned with a robust blend of spices, and the trinity of onions, bell peppers, and celery forms the flavor base.

Cooking Style Cajun jambalaya often features a brown roux for added depth and a rustic, hearty feel. It's a flavorful dish that reflects the down-to-earth, rural roots of Cajun cuisine.

Creole Jambalaya

Ingredients Creole jambalaya may include a mix of proteins like shrimp, ham, and smoked sausage. Tomatoes are a distinguishing feature, giving the dish a slightly reddish hue. The trinity is present, but green bell peppers are more common.

Cooking Style Creole jambalaya tends to have a lighter, tomato-based sauce. The cooking style aligns more with the sophisticated techniques often associated with Creole cuisine.

Despite these variations, the essence of jambalaya as a communal, flavorful dish that brings people together is a shared sentiment in both Cajun and Creole communities.

It truly reflects Louisiana's cultural melting pot, where diverse influences meld into a harmonious culinary symphony.

Whether enjoyed at a family gathering, a festival, or a casual dinner, jambalaya embodies the spirit of Louisiana's love for good food, good company, and good times.

Cajun Jambalaya Recipe

This Jambalaya is a meal that brings folks together, so gather your loved ones and savor the taste of Louisiana's heart and soul.

Ingredients

1 lb andouille sausage, sliced

1 lb boneless, skinless chicken thighs cut into bite-sized pieces

1 large onion, finely chopped

1 bell pepper, diced

3 celery stalks, chopped

3 cloves garlic, minced

1 can (14 oz) diced tomatoes

1 cup long-grain white rice

2 cups chicken broth

2 teaspoons Cajun seasoning (adjust to taste)

1 teaspoon dried thyme

1 teaspoon dried oregano

Salt and black pepper to taste

Green onions, chopped, for garnish

Fresh parsley, chopped, for garnish

Instructions

Prepare Ingredients

Slice the andouille sausage.

Cut chicken thighs into bite-sized pieces.

Chop onion, bell pepper, celery, garlic, green onions, and parsley.

Sear Meats

In a large, heavy pot or Dutch oven, sear the andouille sausage over medium-high heat until browned. Remove and set aside.

In the same pot, add the chicken pieces and brown them on all sides. Remove and set aside.

Sauté Vegetables

In the same pot, add a bit of oil if needed. Sauté the onion, bell pepper, celery, and garlic until softened.

Build Flavors

Stir in the diced tomatoes and cook for a few minutes.

Add Cajun seasoning, dried thyme, and dried oregano. Season with salt and black pepper to taste.

Combine Ingredients

Return the seared andouille sausage and chicken to the pot.

Add the rice and stir to coat the rice with the flavorful mixture.

Simmer

Pour in the chicken broth and bring the mixture to a boil.

Reduce heat to low, cover the pot, and let it simmer for 20-25 minutes or until the rice is cooked and has absorbed the liquid. Stir occasionally to prevent sticking.

Serve

Once the rice is tender, remove the pot from heat.

Garnish with chopped green onions and fresh parsley.

Enjoy

Serve hot, and enjoy the flavorful goodness of Cajun Jambalaya!

Nutritional Information

(Per Serving, Assuming 6 Servings)

Remember that the nutritional values are approximate and can vary based on specific ingredients and portion sizes. The values provided are for one serving of Cajun Jambalaya, assuming the recipe makes approximately six servings.

Calories: Approximately 450-500 calories

Total Fat: 20-25g

Saturated Fat: 7-9g

Trans Fat: 0g

Cholesterol: 80-90mg

Sodium: 1200-1400mg

Total Carbohydrates: 35-40g

Dietary Fiber: 2-3g

Sugars: 3-4g

Protein: 20-25g

Note

The nutritional values can vary based on the specific brands and types of andouille sausage, chicken, rice, and other ingredients used.

Adjustments, such as using leaner sausage or brown rice, can impact the nutritional content.

For precise nutritional information, especially if you have specific dietary considerations, it's advisable to use a nutrition calculator with the exact brands and quantities of ingredients you use.

Until next time, I wish you warmth and flavor!

#grandmamarie#grandmamaries#grandmamarieslouisianakitchen#cajun#creole#cooking#recipe#recipes#culture#history#heritage#jambalaya#jambalaya recipe

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

My #BLEWISH ancestry shows up in different ways. My maternal DNA is Ashkenazi-Russian Jewish. On the paternal side, like many African Americans, my ancestors are a swirl of Black, Native American, and European White — largely German, though I don’t know how much of that was added to the mix consensually.

Rosalyn and Kelly, my parents, were married in Seattle, Washington long before the Supreme Court made unions like theirs fully legal throughout the United States. But unlike many interracial couples, they grew up together during the Depression in North Minneapolis, where Black people and Jewish people were “allowed” to live side by side.

My parents divorced when I was two, just before my younger brother was born. Mom raised us in the very diverse Central Area of Seattle, which (pre-gentrification) was where many Black and Asian people resided.

My mother was proud of her Jewish heritage. While she wasn’t religiously observant, she did send my brother and I to Hebrew school. “I want you to learn about my people’s history, culture, and beliefs,” she explained.

Food was my mother’s love language and a form of spiritual expression. Everything from the simplest dishes to elaborate meals were always cooked to perfection. Most Sundays, she turned out a soul food feast with chicken (baked, not fried), collard greens, candied yams, rice, and often black-eyed peas. Sometimes she even threw in a sweet potato pie. My father had tutored her in creating these delicacies during their years together.

When it came to traditional Jewish dishes, she didn’t cook many, though she’d rhapsodize about her mother’s knishes, rugelach, and schmaltz. But she was serious about her chicken soup. She cooked it old school: a whole chicken, plump chunks of carrots, silvered slices of celery, and plenty of “nature’s antibiotics:” onion and garlic. Sometimes she added noodles; other times, rice. One thing was certain: Mom’s chicken soup was a powerful healing elixir for body, mind, spirit, and soul. And true to form, she whipped some up and administered it at the first sign of any illness.

My approach to cooking is more serviceable than spiritual, and I don’t have my mom’s gift for making everything flawless. But I have carried on the traditions of two cherished dishes: collard greens and chicken soup. My now-grown son and daughter request and expect collard greens for every holiday meal, and they grew up eating chicken soup as a cure-all. Their adult palates are more vegetarian–vegan, so the chicken soup tradition might well end with my generation. But the spirit of healing chicken soup lives on in spirit and memory. Who knows, maybe they’ll come up with a non-poultry option.

Every New Year’s Eve, my mother cooked collards and black-eyed peas, and made sure we all ate at least a little before midnight. “The greens are for money, and the peas for good luck,” she’d remind us. I didn’t realize how deeply this was rooted in African American tradition until I moved to the South.

I thought all the mothers of Mixed-Black children were experts at preparing soul food. It wasn’t until I was grown that I realized how extraordinary my mother was. As my brother and I brought people from different places into our multicultural home, I watched in amazement as she mastered their traditional dishes as well from lumpia and adobo for my brother’s Filipina girlfriend to berbere and Doro Wot for my Ethiopian beau.

My mother’s eclectic approach to culinary expression taught me a lot about being from a mixed-race background. Her kitchen was a living laboratory of what we now call diversity. She learned and then produced the dishes from different cultures with reverence and seasoned them with love. They mirrored her approach to people and life: open-minded and open-hearted with a hearty appreciation for the cultural spice of life.

Unlike my late mother, I normally take shortcuts in the kitchen. But chicken soup and collard greens are sacred, and require elaborate rituals, often taking a couple of days. I clear my counters and my schedule, and savor the opportunity to commune with my parents and to reflect on the paths of their ancestors that brought them together in a rule-breaking love with the audacity to produce children who were destined to live outside the lines.

And when I place small amounts of those special dishes upon my ancestral altar, I give special thanks for the vision, heart, and culinary prowess of a mama who spoke — and cooked — Yiddish and jazz.*

Note: Use your favorite seasonings to flavor your greens. Lawry’s Seasoning Salt is popular and Seasonest (sold in Whole Foods and online) is a Black family-owned alternative with all-natural ingredients.

*I borrowed the phrase, “a mother who speaks Yiddish and jazz” from my #BLEWISH sister-author Lisa Jones and her wonderful book “Bulletproof Diva“.

Make sure to Check out TaRessa Stovall’s most recent book “Swirl Girl: Coming of Race in the USA“.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

watching High on the Hog and Stephen Satterfield is talking with a man that was a sharecropper as a boy. and Elvin Shields is describing to him what it was like and the conversation shifts to how machinery led to these black people being kicked off of the land they lived on, farmed and died on.

Satterfield says that we’ve suppressed our plantation origin story and often a lot of us don’t want to work the land bc it feels too close to what our ancestors went through and Shields tells him that we shouldn’t be ashamed. this kind of cultivation of the land is something we created as a people.

Shields says that his ancestors lived and died on the plantation and the first sources of black community in America were on plantations for centuries. that plantations shouldn’t be this source of shame for us. i agree. African American culture is indigenous to the US. and there is no United States without us. I feel no shame from where I come from. I don’t feel like I need to own another’s history bc my history is right here and my history is a story of resilience. and I feel like so many of us forget that.

they’re having this conversation on a plantation too.

this reminds me of how a black chef that went on to start her own successful restaurant was told by her parents that she should possibly reconsider this culinary career at the beginning bc cooking for someone as a black woman has a certain connotation and they wanted better for her or something like that. her name is Mashama Bailey. she had an episode on Netflix’s Chef’s Table. we carry so much shame. we have some legitimate claim over American cuisine and the land. it’s best not to run from that.

#living here has really taught me the importance of ownership#i knew already but it hits home to be able to return to land that in your blood is yours.#the deed is over 100 years old and falling apart lol but I have seen it

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Last Song I Listened To:

"You" by Tennyson! it's a sweet little song and i use it for my qpr-in-my-series playlist. "What's the point of that? I could be pressing flowers with you. Savor all this time rather than fret all afternoon. Take me from my thoughts, now would be riper than limes in June." so soft.

Last Book I Read:

The Ballad of Black Tom by Victor LaValle is the last book i finished. phenomenal book. absolutely wonderful on a craft level. It pushes the reader to question the role of a black main character in an american horror, pushes the reader to question what constitutes horror is for black americans, and in that push answers your question for you, delicately, carefully. Deserves all the praise it got. Recontextualizes one of the most racist lovecraft stories and shows the character of Black Tom's humanity even as Black Tom tries to leave humanity behind. also. sentence level? so fucking good. down to the sentence it's so good.

I'm currently in the middle of like 15 books but off the top of my head

Witch King by Martha Wells

Dreadgod by Will Wight

To Say Nothing of the Dog by Connie Willis

On the Shoulders of Titans by Andrew Rowe

The Future Is Disabled by Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha which feels more like a manifesto than anything else so im not really getting as much out of it bc disabled people on tumblr have been talking about the contents of this manifesto since 2015 or earlier

The League of Gentlewomen Witches by India Holton

The Last Sun by K.D. Edwards

Paul Takes the Form of a Mortal Girl by Andrea Lawlor

Way of the Hunter by Samer Rabadi

Female Masculinity by Jack Halberstam

Coming up, I'm doing a buddy read soon of The Black Shoals: Offshore Formations of Black and Native Studies by Tiffany Lethabo King with @markeyverse and a buddy read of The Cooking Gene: A Journey of African American Culinary History in the Old South by Michael W. Twitty with @toopunkrockforshul and a book club read of When the Angels Left the Old Country by Sacha Lamb

Last Thing I Watched:

Star Trek: The Next Generation. I simply don't Watch things these days, unless we count youtube, in which I have watched Drawfee's "Driving from Washington to Mexico for Charity" to cope with grief bc omg you do not need your brain for that. it's comforting. and also my roommate is obsessed with Azerbaijani Village Cooking Videos and points out different foods and how like the ones he grew up with they are and how they differ from Georgian and Russian preparation and consumption and he tells me the names of the food and what they taste like. so we watch that almost every night if i dont fall asleep first.

Current Obsession:

my own work tbh. my poetry, my fiction, my paintings. trying to get better. i suppose outside of that. hm. my interest is turning toward gay nuns as of yesterday with a Realization of christian religious trauma being more real than i thought. im looking at "Immodest Acts", "Lesbian Nuns: Breaking Silence", "Scorched Grace: A Sister Holiday Mystery", and im hoping "Sisters of Sorrow" is gay bc if its not what the fuck are you doing. but i cant delve into them all yet nor buy them yet. and im trying to prioritize my TBR.

i'm also reading eco-justice poetry/nonfiction, afrofuturist, transformative justice, disabled, and solarpunk literature for my solarpunk wip

Tags 8 people:

im tagging yall. no big if you dont wanna do the meme. im gonna go lay down now. sleepy.

@filthburgur @cadencekismet @mysanaf @vorellaraek @markeyverse @pacifistrun @outside-your-window @cassandors

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

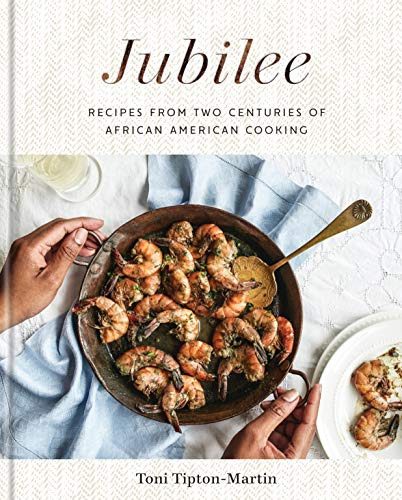

Click to download this book for free on Z-Lib

Adapted from historical texts and rare African-American cookbooks, the 125 recipes of Jubilee paint a rich, varied picture of the true history of African-American cooking: a cuisine far beyond soul food. Toni Tipton-Martin, the first African-American food editor of a daily American newspaper, is the author of the James Beard Award-winning The Jemima Code, a history of African-American cooking found in-and between-the lines of three centuries' worth of African-American cookbooks.

Tipton-Martin builds on that research in Jubilee, adapting recipes from those historic texts for the modern kitchen. What we find is a world of African-American cuisine-made by enslaved master chefs, free caterers, and black entrepreneurs and culinary stars-that goes far beyond soul food. It's a cuisine that was developed in the homes of the elite and middle class; that takes inspiration from around the globe; that is a diverse, varied style of cooking that has created much of what we know of as American cuisine.

“A celebration of African American cuisine right now, in all of its abundance and variety.”—Tejal Rao, The New York Times JAMES BEARD AWARD WINNER • IACP AWARD WINNER • IACP BOOK OF THE YEAR • TONI TIPTON-MARTIN NAMED THE 2021 JULIA CHILD AWARD RECIPIENT NAMED ONE OF THE BEST COOKBOOKS OF THE YEAR BY The New York Times Book Review • The New Yorker • NPR • Chicago Tribune • The Atlantic • BuzzFeed • Food52 Throughout her career, Toni Tipton-Martin has shed new light on the history, breadth, and depth of African American cuisine. She’s introduced us to black cooks, some long forgotten, who established much of what’s considered to be our national cuisine. After all, if Thomas Jefferson introduced French haute cuisine to this country, who do you think actually cooked it? In Jubilee, Tipton-Martin brings these masters into our kitchens. Through recipes and stories, we cook along with these pioneering figures, from enslaved chefs to middle- and upper-class writers and entrepreneurs. With more than 100 recipes, from classics such as Sweet Potato Biscuits, Seafood Gumbo, Buttermilk Fried Chicken, and Pecan Pie with Bourbon to lesser-known but even more decadent dishes like Bourbon & Apple Hot Toddies, Spoon Bread, and Baked Ham Glazed with Champagne, Jubilee presents techniques, ingredients, and dishes that show the roots of African American cooking—deeply beautiful, culturally diverse, fit for celebration. Praise for Jubilee “There are precious few feelings as nice as one that comes from falling in love with a cookbook. . . . New techniques, new flavors, new narratives—everything so thrilling you want to make the recipes over and over again . . . this has been my experience with Toni Tipton-Martin’s Jubilee.”—Sam Sifton, The New York Times “Despite their deep roots, the recipes—even the oldest ones—feel fresh and modern, a testament to the essentiality of African-American gastronomy to all of American cuisine.”—The New Yorker “Jubilee is part-essential history lesson, part-brilliantly researched culinary artifact, and wholly functional, not to mention deeply delicious.”—Kitchn “Tipton-Martin has given us the gift of a clear view of the generosity of the black hands that have flavored and shaped American cuisine for over two centuries.”—Taste

#Jubilee#african american cookbooks#African American Cooking#toni tipton Martin#American Cuisine#African American Cuisine#homegrown recipes#roots of African American Gastronomy

10 notes

·

View notes

Quote

I dare to believe all Southerners are a family. We are not merely Native, European, and African. We are Middle Eastern and South Asian and East Asian and Latin American, now. We are a dysfunctional family, but we are still a family. We are unwitting inheritors of a story with many sins that bears the fruit of the possibility of ten times the redemption. One way is through reconnection with the culinary culture of the enslaved, our common ancestors, and restoring their names on the roots of the Southern tree and the table those roots support.

Michael Twitty in Afroculinaria. American Food and Race: Ten Things I Learned from Writing and Living The Cooking Gene

THE COOKING GENE: A Journey Through African American Culinary History in the Old South

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Creole Seasoning Blend: The Spice Mix That Transforms Dishes

If you're a fan of adding a burst of flavour to your dishes, you've probably come across the term "Creole seasoning blend" at some point. In this article, we'll delve into the world of Creole seasoning, exploring its origins, ingredients, and how you can use it to elevate your culinary creations.

What is Creole Seasoning Blend?

Creole seasoning is a zesty and aromatic spice mix used in Southern cuisine, particularly in Creole and Cajun dishes. It's renowned for its ability to infuse dishes with a bold and tantalising flavour profile. This seasoning blend can be the secret weapon in your kitchen, adding depth and complexity to a wide range of recipes.

A Brief History of Creole Cuisine

To truly understand Creole seasoning, it's essential to grasp the rich history of Creole cuisine. Creole cooking is deeply rooted in the multicultural influences of Louisiana, particularly New Orleans. It's a fusion of French, Spanish, African, and Native American culinary traditions.

The word "Creole" itself refers to the descendants of European settlers in the region, but over time, Creole cuisine evolved to include a diverse array of ingredients and cooking techniques. Creole seasoning emerged as a cornerstone of this cuisine, contributing its unique blend of flavours to countless iconic dishes.

The Ingredients in Creole Seasoning Blend

Creole seasoning typically contains a medley of spices and herbs. While the exact ingredients may vary from one blend to another, common components include paprika, cayenne pepper, garlic powder, onion powder, thyme, oregano, and salt. These ingredients work in harmony to deliver a spicy, savoury, and slightly smoky flavour that's unmistakably Creole.

How to Use Creole Seasoning in Your Cooking?

One of the beauties of Creole seasoning is its versatility. You can use it to add depth to meats like chicken, pork, or shrimp, or sprinkle it onto vegetables and potatoes before roasting. It's also a key player in classic dishes like jambalaya, gumbo, and red beans and rice. Just a pinch or two can transform an ordinary meal into a culinary masterpiece.

Where to Buy or Make Your Own Creole Seasoning

When it comes to Creole seasoning, you have two main options: buying it pre-made or making your own at home. Many grocery stores carry commercially prepared Creole seasoning, often in convenient shaker bottles. These are a great choice if you're looking for convenience and consistency.

If you prefer to craft your own seasoning blend, it's easy to do so with readily available spices. By adjusting the proportions of ingredients to your taste, you can create a customised blend that suits your palate perfectly. A homemade Creole seasoning can be a source of pride in your kitchen.

Final Thoughts

Creole seasoning spice blend is a culinary treasure with roots in the vibrant and diverse Creole cuisine of Louisiana. Its combination of spices and herbs adds depth and character to a wide range of dishes, from seafood to meats and vegetables. Whether you choose to buy it pre-made or make your own, this seasoning blend is sure to become a staple in your kitchen.

So, the next time you're looking to spice up your meals, don't forget to reach for that trusty Creole seasoning. Its unique flavours will transport your taste buds to the heart of the South, creating a dining experience that's nothing short of magical.

#diet coaching program#personalized weight loss plan#buy glass oil dispenser online#personalized meal plan for weight loss#weight loss program#creole spice blend#creole seasoning blend

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

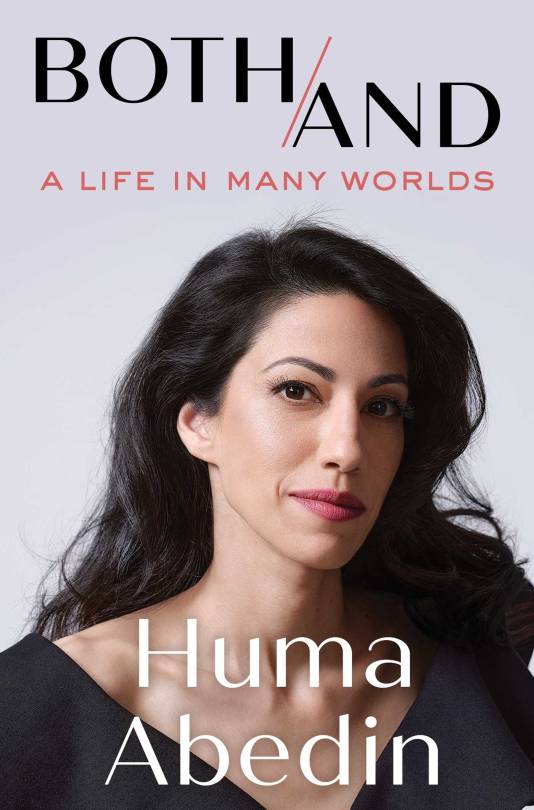

Nonfiction Thursday: Asian American & Pacific Islander (AAPI) Biographies

Both/And by Huma Abedin

The daughter of Indian and Pakistani intellectuals and advocates, Abedin grew up in the United States and Saudi Arabia and traveled widely. Both/And grapples with family, legacy, identity, faith, marriage, motherhood—and work—with wisdom, sophistication, grace, and clarity.

Abedin launched full steam into a college internship in the office of the First Lady in 1996, never imagining that her work at the White House would blossom into a career in public service, nor that her career would become an all-consuming way of life. She thrived in rooms with diplomats and sovereigns, entrepreneurs and artists, philanthropists and activists, and witnessed many crucial moments in 21st-century American history—Camp David for urgent efforts at Middle East peace in the waning months of the Clinton administration, Ground Zero in the days after the September 11 attacks, the inauguration of the first African American president of the United States, and the convention floor when America nominated its first female presidential candidate.

Abedin’s relationship with Hillary Clinton has seen both women through extraordinary personal and professional highs, as well as unimaginable lows. Here, for the first time, is a deeply personal account of Clinton as mentor, confidante, and role model. Abedin cuts through caricature, rumor, and misinformation to reveal a crystal-clear portrait of Clinton as a brilliant and caring leader, a steadfast friend, generous, funny, hardworking, and dedicated.

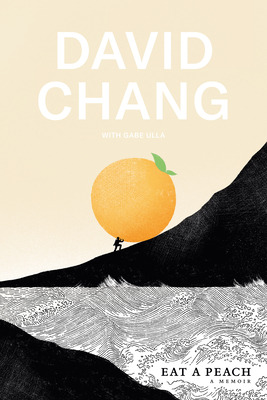

Eat a Peach by David Chang

In 2004, David Chang opened a noodle restaurant named Momofuku in Manhattan's East Village, not expecting the business to survive its first year. In 2018, he was the owner and chef of his own restaurant empire, with 15 locations from New York to Australia, the star of his own hit Netflix show and podcast, was named one of the most influential people of the 21st century and had a following of over 1.2 million. In this inspiring, honest and heartfelt memoir, Chang shares the extraordinary story of his culinary coming-of-age.

Growing up in Virginia, the son of Korean immigrant parents, Chang struggled with feelings of abandonment, isolation and loneliness throughout his childhood. After failing to find a job after graduating, he convinced his father to loan him money to open a restaurant. Momofuku's unpretentious air and great-tasting simple staples - ramen bowls and pork buns - earned it rave reviews, culinary awards and before long, Chang had a cult following.

Chang's love of food and cooking remained a constant in his life, despite the adversities he had to overcome. Over the course of his career, the chef struggled with suicidal thoughts, depression and anxiety. He shied away from praise and begged not to be given awards. In Eat a Peach, Chang opens up about his feelings of paranoia, self-confidence and pulls back the curtain on his struggles, failures and learned lessons.

Stay True by Hua Hsu

In the eyes of eighteen-year-old Hua Hsu, the problem with Ken--with his passion for Dave Matthews, Abercrombie & Fitch, and his fraternity--is that he is exactly like everyone else. Ken, whose Japanese American family has been in the United States for generations, is mainstream; for Hua, the son of Taiwanese immigrants, who makes 'zines and haunts Bay Area record shops, Ken represents all that he defines himself in opposition to. The only thing Hua and Ken have in common is that, however they engage with it, American culture doesn't seem to have a place for either of them.

But despite his first impressions, Hua and Ken become friends, a friendship built on late-night conversations over cigarettes, long drives along the California coast, and the textbook successes and humiliations of everyday college life. And then violently, senselessly, Ken is gone, killed in a carjacking, not even three years after the day they first meet.

Determined to hold on to all that was left of one of his closest friends--his memories--Hua turned to writing. Stay True is the book he's been working on ever since. A coming-of-age story that details both the ordinary and extraordinary, Stay True is a bracing memoir about growing up, and about moving through the world in search of meaning and belonging.

The Stories We Tell by Joanna Gaines

"The only way to break free was to rewrite my story. Because something would happen every time my pen stopped: it was like my soul was coming back to my body. Like the deepest parts of me that got knocked around and drowned out by all the crap I let the world convince me about who I was came back to the surface. And what was left was only what was real and true. I was, finally, standing in the fullness of my story. I felt hopeful. I felt full. Our story may crack us open, but it also pieces us back together.

We all have a story to tell. This happens to be mine--every chapter a window into who I am, the journey I'm on, and the season I'm in right now. Because this is my story, maybe you won't always relate, or maybe it will feel like you're looking in a mirror. Whatever we have in common and whatever differences lie between us, I only hope my story can help shine a light on the beauty of yours. That my own soul work will stir something of your own. And that by the time you get to the end of my story, you're also holding the beautiful beginnings of your own.

A story only you can tell. And I hope that you will."

- Joanna Gaines

#biography#biographies#memoir#AAPI authors#AAPI#aapiheritagemonth#nonfiction#nonfiction books#Nonfiction Reading#Library Books#Book Recommendations#book recs#Reading Recs#reading recommendations#TBR pile#tbrpile#tbr#to read#Want To Read#Booklr#book tumblr#book blog#library blog

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Skip to content Soul food Friday

BLACK FOODIE

MAIN MENU

BLACK CULTURE

The Humble History of Soul Food

Vanessa Hayford | January 22, 2018

soul food

Soul food is one of the most popular and recognizable types of cooking coming out of the United States. For centuries, Black Americans have passed on hearty, sumptuous recipes that have marked many a special occasion.

If you’re like me, you’re a sucker for soul food. The mere idea of fried chicken, collard greens, and cornbread is enough to make my mouth water. But most of us spend more time drooling over soul food than thinking about it.

Soul food takes its origins mostly from Georgia, Mississippi, and Alabama, a collection of states commonly referred to as the Deep South. During the Transatlantic Slave Trade, enslaved African people were given meager food rations that were low in quality and nutritional value. With these rations, enslaved people preserved African food traditions and adapted traditional recipes with the resources available. Over time, these recipes and techniques have become the soul food dishes we are familiar with today. This food genre, now associated with comfort and decadence, was born out of struggle and survival.

Soul food has a rich and important history that ties Black culture to its African roots, and that history is deeply reflected in the staple recipes and techniques. In soul food cooking, there are four key ingredients that establish a historical link to America’s dark slavery past and the African cultures that the enslaved carried with them.

Rice

jambalaya

It may surprise you to know that rice is not indigenous to the Americas. In fact, many crops that are key ingredients in soul food cooking were nowhere to be found in the Western Hemisphere prior to the slave trade.

During the Middle Passage, slave traders intentionally took several crops native to Africa and made limited portions of these foods available on the slave ships in order to keep the enslaved alive. Once in the Americas, the enslaved Africans grew these crops on the plantations as food sources that would keep their energy up during the long days of hard labor.

The transport of the African variety of rice in particular through the slave trade arguably set the foundation for the most notable southern American culinary traditions. Since rice is a staple in many African dishes, enslaved Africans adapted their cooking in the Americas with the food items that were most accessible, creating some of the most renowned soul food staples.

Today, we can still see clear similarities between one-pot rice recipes like jambalaya, and Jollof, a wildly popular traditional dish in many West African countries. Other dishes, like Hoppin’ John, bear resemblance to Ghana’s waakye, and Senegal’s thiebou niebe.

Okra

okra

Whether it’s stewed, fried or baked, okra has grown to become a cornerstone of southern American cooking despite its African roots. The slimy green vegetable has a deep history, likely originating from Ethiopia. Over the centuries the vegetable made its way through the Middle East, North Africa, and even South Asia. It wasn’t until the 18th century when Okra made its way to the Americas through the slave ships. Historically, okra has been used as a soup thickener, a coffee substitute, and even as a material for rope.

Okra is still used today in a variety of African soups, stews, and rice dishes, and the recipes vary widely from country to country. While it is usually served fried in the Deep South, many are most familiar with okra as an ingredient in gumbo, a rich and savory stew usually consisting of some sort of meat or seafood, vegetables, and served with rice. Strangely enough, the word “gumbo” is derived from “ki ngombo”, the Bantu word for Okra.

Pork

bbq

Barbeque in the south of the United States isn’t just reserved for casual celebrations and backyard gatherings; it is a time-honored and sophisticated art form with very humble beginnings.

Pork has been the choice meat in the South for centuries, and the preferred method of preserving the meat in the past was to salt and smoke it. During the Atlantic slave trade, it was slaves who were frequently given the grueling task of preserving the meat. As a result, many of the techniques in curing meat are said to have been developed by African-Americans of the era.

The cheapest, least desired cuts of pork – such as the head, ribs, feet, or internal organs – were reserved for the slaves’ weekly food rations. As would be expected, the taste of these cuts of meat is not the best. So, to mask the poor flavor of the meat enslaved people drew from their traditional African cooking and used combinations of seasonings on their meat. A mixture of hot red peppers and vinegar was very common, and this flavoring has served as the base of many different barbecue sauces that are still used in the South.

Greens

collard greens

Last but not least, the ubiquitous greens of soul food.

It’s no secret that many cultures have a practice of boiling leafy greens. Nowhere is this practice most common than in African countries, where the selection of leafy green vegetables is unparalleled. Several dishes across the African continent, such as Ethiopia’s gomen wat and Ghana’s kontomire stew, are comparable to the collard greens dish we are familiar with in the West.

As one of the most recognizable aspects of soul food cuisine, it is very clear that the culinary technique of boiling greens has a specific link to traditional African methods of eating.

During the slavery, era greens were boiled in pork fat and seasoning with a combination of whatever vegetables were available at the time. The juices left over from the cooking process, casually known as “potlikker”, was soaked up and eaten with cornbread. This style of eating is reminiscent of various traditional dishes in Africa. Whether it’s injera in Ethiopia or fufu in Nigeria, many African countries have a practice of dipping a staple starch into a vegetable and meat-based gravy.

Sources:

http://mgafrica.com/article/2015-11-02-african-food-america

http://ushistoryscene.com/article/slavery-southern-cuisine/

http://www.un.org/africarenewal/web-features/slave-trade-how-african-foods-influenced-modern-american-cuisine

http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2014/03/140301-african-american-food-history-slavery-south-cuisine-chefs/

http://www.epicurious.com/expert-advice/real-history-of-soul-food-article

http://www.gloryfoods.com/blog/the-origin-of-collard-greens/

WANT MORE BLACK FOODIE?

Our best tips for eating thoughtfully and living joyfully, right in your inbox.

Enter your email

ENTER YOUR EMAIL

JOIN NOW

RELATED ARTICLES

You might be interested in...

Sweet N Nice article cover 2

BLACK FOODIE’s California Guide

BLACK CULTURE

California is well known for its beaches and its laid-back way of life, but you might not realize that the Golden State is rich with […]

Bess scaled

A BLACK FOODIE Guide to Ottawa

BLACK CULTURE | BLACK-OWNED BUSINESSES | GUIDES

At BLACK FOODIE we believe the best way to experience a new city is to explore its local food scene beyond the tourist favourites. While […]

Detroit, MI

313.351.5643

COMPANY

Articles

Recipes

Partner

Video Archives

COMMUNITY

BLACK FOODIE Week

Donate

Instagram

Facebook

Twitter

SIGN UP FOR OUR NEWSLETTER

Get monthly perks and tips for eating, cooking, and enjoying your best #blackfoodie life!

Enter your email

ENTER YOUR EMAIL

JOIN NOW

© 2023 BLACK FOODIE.

Privacy Terms Cookies

Web Development by Awesome Web Designs

Scroll to Top

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Southern Food Heritage Day

Every year, Southern Food Heritage Day is celebrated on October 11. The Southern Food & Beverage Museum celebrates the culturally rich and delicious food of the Southern States in America. The cuisine deserves to be recognized and celebrated officially because it is a testament to American history and legacy. Southern food also represents the essence of America — the coming together of a variety of people from all over the world, each bringing with themselves their own ingredients and recipes to create a unique cuisine. Iced tea, pickled shrimps, and fried chicken are some of the most loved Southern foods throughout history. Along with the cuisine, the day also celebrates the racial and ethnic diversity in America.

History of Southern Food Heritage Day

Southern Food Heritage Day celebrates the best that Southern food and beverages have to offer. The South’s cuisine in America can be found in the historical regional culinary form of states generally south of the Mason-Dixon line dividing Pennsylvania and Delaware from Maryland, along the Ohio River, and extending west to southern Missouri, Oklahoma, and Texas. The most notable influences on Southern cuisine are African, English, Scottish, Irish, German, French and Native American.

The food of the American South displays a unique blend of cultures and culinary traditions. The Native Americans, Spanish, French, and British have contributed to the development of Southern food, with recipes and dishes from their own cultures. Food items such as squash, tomatoes, corn, as well as certain cooking practices such as deep pit barbecuing, were introduced by south-eastern Native American tribes such as the Caddo, Choctaw, and Seminole. Many foods derived from sugar, flour, milk, and eggs have European roots. Black-eyed peas, okra, rice, eggplant, sesame seed, sorghum, and melons, along with spices, are of African origin.

Southern food can be further divided into categories: ‘Soul food’ is heavily influenced by African cooking traditions that are full of greens and vegetables, rice, and nuts such as peanuts. Okra and collard greens are also considered Soul Food, along with thick stews. ‘Creole food’ has a French flair, while ‘Cajun cuisine’ reflects the culinary traditions of immigrants from Canada. ‘Lowcountry’ cuisine features a lot of seafood and rice, while the food of the Appalachians is mostly preserved meats and vegetables. Southern food is partial to corn, thanks to the Native American influence.

Southern Food Heritage Day timeline

1860

Southern Diet Expands

Following the emancipation from slavery, the Southern diet becomes versatile.

1916

The Great Migration

African Americans travel from rural communities in the South to large cities in the North and West — they carry their cuisine with them.

1940s

Southern Foods in Restaurants

Southern foods start appearing on restaurant menus and appeal to a diverse clientele.

1964

Soul Food

This term, describing everyday Southern food, first appears in print.

Southern Food Heritage Day FAQs

What is the difference between Southern food and soul food?

The difference between soul food and Southern food is rooted more in class than race, and what families were able to afford to put on the table.

What is a typical Southern meal?

A traditional Southern meal is pan-fried chicken, field peas, greens, mashed potatoes, cornbread or corn pone, sweet tea, and a pie for dessert.

Why is Southern food so unhealthy?

The Southern diet is commonly high in processed meats, which are high in salt and in nitrates, which are in turn linked to heart risk. The high sugar content of the diet may also lead to negative effects, like insulin resistance and inflammation.

How To Celebrate Southern Food Heritage Day

Organize a cook-off: Gather all your friends and organize a cook-off on Southern Food Heritage Day. Revive old recipes or add a twist to create something new.

Go out for a meal: Enjoy the best of Southern foods at your favorite Southern foods restaurant. Don’t forget to enjoy the classics like fried chicken, hush pies, and pies.

Set up a barbecue: Barbecues are an integral part of the Southern food heritage. It is also one of the most popular styles of cooking. Barbecue your favorite meats and vegetables, and serve them with sauces and seasonings.

5 Facts About Southern Foods That Will Blow Your Mind

Redeye gravy has a unique recipeRedeye gravy is made with pan drippings and leftover coffee.

It is more calorie-denseSouthern fried chicken breast typically has more than 400 calories in an ounce.

Peanut butter is an essentialHalf the annual crop of peanuts is used to make peanut butter.

Collard green has been around foreverIt’s been a part of our diet for more than 2,000 years.

Black-eyed peas are also good luck charmsIt is believed that black-eyed peas bring good luck on New Year’s Day.

Why We Love Southern Food Heritage Day

A day to indulge: You cannot celebrate Southern Food Heritage Day without enjoying a hearty meal of your favorite foods. This is truly a day of indulgence!

Try something new: The best thing about Southern food is that it has something for everyone. Use this day to try a new food item or the cuisine of Southern heritage. Who knows, you might just discover your next favorite dish!

It is historically significant: Southern foods have a rich cultural and historical significance. Learn more about the origins of your favorite foods on Southern Food Heritage Day.

Source

#Fried Chicken Sandwich#ice tea#Fried Chicken#collard green#Okra stew#Southern Food Heritage Day#USA#soul food#original photography#travel#vacation#restaurant#SouthernFoodHeritageDay#Coconut Cake#Shrimp and Grits#Hot Sausage Po'Boy#candied yam#Florida Gator Tail#Gumbo#Jambalaya#Pecan Pie#Chicken Fried#gravy#corn cob#Baby Back Ribs#11 October#Peach Cobbler#Pulled Pork Sandwich#Okra#Collard Greens

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Remembering Caesar, Colonial Virginia’s Enslaved Chocolatier In Gastro Obscura’s Q & A series A Seat at the Table, we speak with people of color who are reclaiming their culinary heritage and shaping today’s food culture. At Stratford Hall, the plantation of the Lee family and the future birthplace of Confederate general Robert E. Lee, lavish Christmas dinners would end with Virginia’s White elite gathering around small, steaming cups of hot chocolate. The drink was sure to impress the guests, as the Lee family owned one of the colony’s few household chocolate stones for turning imported beans into a luxurious brew. Said hot chocolate was the work of one of Virginia’s few chocolatiers: a man known only as Caesar, the enslaved African-American chef whose virtuosity helped make Stratford Hall a centerpiece of Virginia’s high society during the mid-1700s. “It's a life mission to be able to help the world understand that people like Caesar existed,” says historical interpreter Dontavius Williams. Several times a year, Williams dons Colonial attire and fires up the hearth at Stratford Hall. Williams is on a quest to show how the brilliance of African-American cooks shaped the South, a mission that’s especially radical within the birthplace of the most prominent Confederate leader. Caesar was born in 1732, and helmed Stratford Hall’s kitchen starting in the middle of the 1700s. He managed one of the most extravagant kitchens in the colonial South, catering to the needs of the Lee family at all hours of the day. At banquets, he would ply up to 100 guests with multiple courses of fanciful delicacies. Caesar’s ability at chocolate-brewing was exceptional, but he also mastered everything from fancy cakes to oyster stew to roasted pheasant. His kitchen operated at the cutting edge of Southern culinary fashion. Williams’ journey to telling Caesar’s story began when, as a college student, he volunteered at a plantation museum in South Carolina. Around 2015, Williams founded The Chronicles of Adam, a project in which he researches the life of a historical enslaved man named Adam and does demonstrations—often involving cooking—to show how he might have lived. In 2019, historian Dr. Kelley Fanto Deetz, author of Bound to the Fire: How Virginia's Enslaved Cooks Helped Invent American Cuisine and Vice President of Collections and Public Engagement at Stratford Hall, invited Williams to cook at the museum. Since then, he has become the resident African-American Foodways Interpreter. Drawing on Stratford Hall’s preserved 18th-century cookbooks and bills of fare, Dr. Deetz’s research, and other primary and secondary sources, he brings the work of African-American cooks to life at the museum’s Juneteenth celebration to programs like “Caesar's Chocolate: The History and Legacy of One of Virginia's Earliest Chocolate Makers,” which paired a discussion of Caesar’s work with a demonstration of historic chocolate-making techniques. Gastro Obscura talked with Williams about Caesar’s culinary skill, the influence of African-American foodways on Southern cuisine, and changing people’s minds with food. What role do you think food plays in historical interpretation? It's the great leveler [and also] the great divider … We all eat. We just eat differently. And I'm able to use those foods and those commonalities to be able to break down the barriers between people, and to eventually change their hearts. I've had some of the most racist people come through. They come to the site of the birthplace of Robert E. Lee in their Confederate caps, and they're coming to honor the president of the Confederacy … And whenever they come in the kitchen, their bubbles are burst a little bit, [but] they leave so much better. They see the fatback [bacon] on the table. They see something that they remember from their grandmother's house. In that type of situation, what might you have said or done to change their attitudes? I pull a page from my mentor Nicole A. Moore. She said, in America, especially in the American South, we eat more closely to the diet of the enslaved than we do the big house. Whenever [guests] come in and say, “Oh, my grandma used to make this,” I'm like, “You know something? If you think about the diet of the enslaved, our diet in the 21st-century South is very close.” I'm able to talk about food rations that were given to the enslaved on certain plantations. And I ask them about other vegetables and fruits that, as Southerners, they may like. I'm like, “So do you like okra?” “Yeah.” “What about black-eyed peas?” “Yeah.” “Did you know that black eyed peas were not considered fit for human consumption?” They're like, “Wait, no, I love black-eyed peas and hoppin’ john!” Okra and black-eyed peas are both native to West Africa. Were there ways, when you were looking at the recipes served in Stratford Hall, that you saw West African influences in what Caesar was cooking? Curry chicken, peanut soup, okra and red tomatoes, things like that: those are direct recipes from West Africa. The black-eyed peas, the cow peas, all those things that were not seen as fit for human consumption [in the 1700s] were actually consumed, and now are fan favorites of Virginia and of our country. What are some aspects of Caesar’s work that you think are really remarkable? The fact that Caesar was one of three chocolate makers in the colonies was amazing. It's been said that Caesar conducted that kitchen as a conductor would do an orchestra, from working with scullery maids to working to bring in wood and water, to ensuring that the produce was always on point and the supplies never ran out. Caesar had to have a lot going on in his brain. I'm able to help to break that mentality of the public that the enslaved population was a dumb population. What do we know about his day-to-day life? His day starts before dawn, and it ends well after dusk. As head cook of the plantation, much like a head chef that you would see in a five-star restaurant today, the weight was heavy. The difference is, a head chef gets paid. [Caesar] ensures that everyone in the big house is fed and satisfied from breakfast until the last chocolate drink at the end of the night. But during the holiday season, he goes into overtime … People are coming in to visit and they're not leaving in 24 hours or in two or three hours; they stay for days and weeks and months. If you were Caesar, or if you were one of those cooks, you're working so hard to make sure that this family is satisfied, but you have January 1 coming. [Enslaved] families are broken up on that day. People are getting rented out, people may get sold, because that's the time where the plantation owner has to balance the books. Do you know if Caesar received recognition for his work from people locally? I haven't seen anything recorded. You don't see a lot of information out there about these guys unless it's been dug up by historians researching their lives, [or] they do something that's completely amazing. Caesar was just doing his job. That's the downside of slavery, right? You work your whole life, and you never get recognition for the wonderful things that you do. What do you think are some lessons that you'd like people to learn from Caesar's story? There are a lot of people who make differences, whose names we never know. But because we do know Caesar's name, I'll scream it from the mountaintop every time I walk into that kitchen. He's not there physically, but every time I walk into that kitchen at Stratford Hall, I say, “Good morning,” or “Good afternoon, Caesar. Thank you for letting me use your space.” He may not have viewed that space as something sacred to him, but for him to be able to survive and thrive, even in the face of slavery, shows me that there was something that kept him motivated. https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/enslaved-chocolate-maker-virginia

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

My #BLEWISH ancestry shows up in different ways. My maternal DNA is Ashkenazi-Russian Jewish. On the paternal side, like many African Americans, my ancestors are a swirl of Black, Native American, and European White — largely German, though I don’t know how much of that was added to the mix consensually.

Rosalyn and Kelly, my parents, were married in Seattle, Washington long before the Supreme Court made unions like theirs fully legal throughout the United States. But unlike many interracial couples, they grew up together during the Depression in North Minneapolis, where Black people and Jewish people were “allowed” to live side by side.

My parents divorced when I was two, just before my younger brother was born. Mom raised us in the very diverse Central Area of Seattle, which (pre-gentrification) was where many Black and Asian people resided.

My mother was proud of her Jewish heritage. While she wasn’t religiously observant, she did send my brother and I to Hebrew school. “I want you to learn about my people’s history, culture, and beliefs,” she explained.

Food was my mother’s love language and a form of spiritual expression. Everything from the simplest dishes to elaborate meals were always cooked to perfection. Most Sundays, she turned out a soul food feast with chicken (baked, not fried), collard greens, candied yams, rice, and often black-eyed peas. Sometimes she even threw in a sweet potato pie. My father had tutored her in creating these delicacies during their years together.

When it came to traditional Jewish dishes, she didn’t cook many, though she’d rhapsodize about her mother’s knishes, rugelach, and schmaltz. But she was serious about her chicken soup. She cooked it old school: a whole chicken, plump chunks of carrots, silvered slices of celery, and plenty of “nature’s antibiotics:” onion and garlic. Sometimes she added noodles; other times, rice. One thing was certain: Mom’s chicken soup was a powerful healing elixir for body, mind, spirit, and soul. And true to form, she whipped some up and administered it at the first sign of any illness.

My approach to cooking is more serviceable than spiritual, and I don’t have my mom’s gift for making everything flawless. But I have carried on the traditions of two cherished dishes: collard greens and chicken soup. My now-grown son and daughter request and expect collard greens for every holiday meal, and they grew up eating chicken soup as a cure-all. Their adult palates are more vegetarian–vegan, so the chicken soup tradition might well end with my generation. But the spirit of healing chicken soup lives on in spirit and memory. Who knows, maybe they’ll come up with a non-poultry option.

Every New Year’s Eve, my mother cooked collards and black-eyed peas, and made sure we all ate at least a little before midnight. “The greens are for money, and the peas for good luck,” she’d remind us. I didn’t realize how deeply this was rooted in African American tradition until I moved to the South.

I thought all the mothers of Mixed-Black children were experts at preparing soul food. It wasn’t until I was grown that I realized how extraordinary my mother was. As my brother and I brought people from different places into our multicultural home, I watched in amazement as she mastered their traditional dishes as well from lumpia and adobo for my brother’s Filipina girlfriend to berbere and Doro Wot for my Ethiopian beau.

My mother’s eclectic approach to culinary expression taught me a lot about being from a mixed-race background. Her kitchen was a living laboratory of what we now call diversity. She learned and then produced the dishes from different cultures with reverence and seasoned them with love. They mirrored her approach to people and life: open-minded and open-hearted with a hearty appreciation for the cultural spice of life.

Unlike my late mother, I normally take shortcuts in the kitchen. But chicken soup and collard greens are sacred, and require elaborate rituals, often taking a couple of days. I clear my counters and my schedule, and savor the opportunity to commune with my parents and to reflect on the paths of their ancestors that brought them together in a rule-breaking love with the audacity to produce children who were destined to live outside the lines.

And when I place small amounts of those special dishes upon my ancestral altar, I give special thanks for the vision, heart, and culinary prowess of a mama who spoke — and cooked — Yiddish and jazz.*

Note: Use your favorite seasonings to flavor your greens. Lawry’s Seasoning Salt is popular and Seasonest (sold in Whole Foods and online) is a Black family-owned alternative with all-natural ingredients.

*I borrowed the phrase, “a mother who speaks Yiddish and jazz” from my #BLEWISH sister-author Lisa Jones and her wonderful book “Bulletproof Diva“.

2 notes

·

View notes