#cinema of resistance

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Persepolis (2007) Directed by Marjane Satrapi & Vincent Paronnaud

#persepolis#marjane satrapi#vincent paronnaud#2007#animated film#graphic novel adaptation#iranian cinema#coming of age#political cinema#revolution and exile#black and white animation#women in film#history and identity#cinema of resistance#visual storytelling#personal journey#family and war#modern classic#social change#existential reflection#bold filmmaking#cinematic storytelling#2000s movies#international women's day#women's history month#march 8#women's rights#feminist cinema#2000#8 march

126 notes

·

View notes

Text

How to construct a revolutionary, multidimensional creative matrix, the operating system of THE REVOLUTION OF THE MIND.

1 note

·

View note

Text

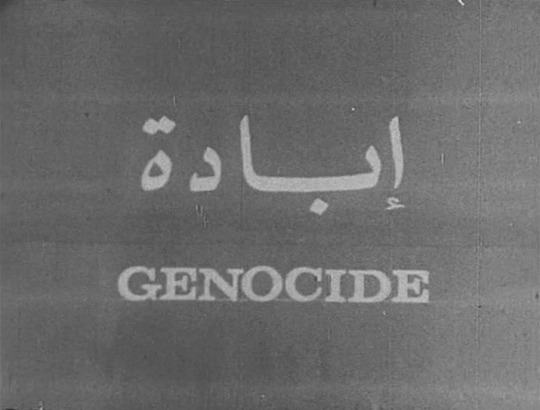

They Do Not Exist (1974) by Mustafa Abu Ali (watch)

from PalestineCinema.com:

Salvaged from the ruins of Beirut after 1982, Abu Ali's early film has only recently been made available. Shooting under extraordinary conditions, the director, who worked with Godard on his Ici et Ailleurs (Here and Elsewhere), and founded the PLO's film division, covers conditions in Lebanon's refugee camps, the effects of Israeli bombardments, and the lives of guerrillas in training camps. They Do Not Exist is a stylistically unique work which demonstrates the intersection between the political and the aesthetic. Now recognised as a cornerstone in the development of Palestinian cinema, the film only received its Palestine premiere in 2003, when a group of Palestinian artists "smuggled" the director to a makeshift cinema in his hometown of Jerusalem (into which Israel bars his entry). Abu Ali, who saw his film for the first time in 20 years at this clandestine event noted: "We used to say 'Art for the Struggle', now it's 'Struggle for the Art'"

#mustafa abu ali#they do not exist#they do not exist 1974#for the missing subs pls message me for the link. just got the yt version and the subs to sync!#palestinian cinema#documentary#screencaps#global struggle#resistance#palestine#jean luc godard#post#history

16K notes

·

View notes

Text

Conrad Veidt in Kreuzzug des Weibes (Martin Berger, 1926)

#i couldn't resist now could i#conrad veidt#kreuzzug des weibes#martin berger#classic film#silent film#silent era#german film#german cinema#weimar cinema#1920s#gifset#my gifs

443 notes

·

View notes

Text

L'armée des ombres (1969) dir. Jean-Pierre Melville

#army of shadows#jean pierre melville#film noir#movies#french movie#french cinema#movie stills#movie quotes#L'armée des ombres#world war ii#french resistance#cinematography#cinema#pierre lhomme

57 notes

·

View notes

Text

Succession 3x4 | Red White & Royal Blue

#lmao#cackling#i could not resist#little lord fuckleroy#dead#red white and royal blue#succession#gif#gifs#gifset#poetic cinema#cinematic parallels#3x4#kendall roy#nicholas galitzine#prince henry#alex claremont diaz#taylor zakhar perez#sarah shahi

406 notes

·

View notes

Text

III. Toward an Anarchist Film Theory

In his article “What is Anarchist Cultural Studies?” Jesse Cohn argues that anarchist cultural studies (ACS) can be distinguished from critical theory and consumer-agency theory along several trajectories (Cohn, 2009: 403–24). Among other things, he writes, ACS tries “to avoid reducing the politics of popular culture to a simplistic dichotomy of ‘reification’ versus ‘resistance’” (ibid., 412). On the one hand, anarchists have always balked at the pretensions of “high culture” even before these were exposed and demystified by the likes of Bourdieu in his theory of “cultural capital.” On the other hand, we always sought ought and found “spaces of liberty — even momentary, even narrow and compromised — within capitalism and the State” (ibid., 413). At the same time, anarchists have never been content to find “reflections of our desires in the mirror of commercial culture,” nor merely to assert the possibility of finding them (ibid.). Democracy, liberation, revolution, etc. are not already present in a culture; they are among many potentialities which must be actualized through active intervention.

If Cohn’s general view of ACS is correct, and I think it is, we ought to recognize its significant resonance with the Foucauldian tertia via outlined above. When Cohn claims that anarchists are “critical realists and monists, in that we recognize our condition as beings embedded within a single, shared reality” (Cohn, 2009: 413), he acknowledges that power actively affects both internal (subjective) existence as well as external (intersubjective) existence. At the same time, by arguing “that this reality is in a continuous process of change and becoming, and that at any given moment, it includes an infinity — bounded by, situated within, ‘anchored’ to the concrete actuality of the present — of emergent or potential realities” (ibid.), Cohn denies that power (hence, reality) is a single actuality that transcends, or is simply “given to,” whatever it affects or acts upon. On the contrary, power is plural and potential, immanent to whatever it affects because precisely because affected in turn. From the standpoint of ACS and Foucault alike, then, culture is reciprocal and symbiotic — it both produces and is produced by power relations. What implications might this have for contemporary film theory?

At present the global film industry — not to speak of the majority of media — is controlled by six multinational corporate conglomerates: The News Corporation, The Walt Disney Company, Viacom, Time Warner, Sony Corporation of America, and NBC Universal. As of 2005, approximately 85% of box office revenue in the United States was generated by these companies, as compared to a mere 15% by so-called “independent” studios whose films are produced without financing and distribution from major movie studios. Never before has the intimate connection between cinema and capitalism appeared quite as stark.

As Horkheimer and Adorno argued more than fifty years ago, the salient characteristic of “mainstream” Hollywood cinema is its dual role as commodity and ideological mechanism. On the one hand, films not only satisfy but produce various consumer desires. On the other hand, this desire-satisfaction mechanism maintains and strengthens capitalist hegemony by manipulating and distracting the masses. In order to fulfill this role, “mainstream” films must adhere to certain conventions at the level of both form and content. With respect to the former, for example, they must evince a simple plot structure, straightforwardly linear narrative, and easily understandable dialogue. With respect to the latter, they must avoid delving deeply into complicated social, moral, and philosophical issues and should not offend widely-held sensibilities (chief among them the idea that consumer capitalism is an indispensable, if not altogether just, socio-economic system). Far from being arbitrary, these conventions are deliberately chosen and reinforced by the culture industry in order to reach the largest and most diverse audience possible and to maximize the effectiveness of film-as-propaganda.

“Avant garde” or “underground cinema,” in contrast, is marked by its self — conscious attempt to undermine the structures and conventions which have been imposed on cinema by the culture industry — for example, by presenting shocking images, employing unusual narrative structures, or presenting unorthodox political, religious, and philosophical viewpoints. The point in so doing is allegedly to “liberate” cinema from its dual role as commodity and ideological machine (either directly, by using film as a form of radical political critique, or indirectly, by attempting to revitalize film as a serious art form).

Despite its merits, this analysis drastically oversimplifies the complexities of modern cinema. In the first place, the dichotomy between “mainstream” and “avant-garde” has never been particularly clear-cut, especially in non-American cinema. Many of the paradigmatic European “art films” enjoyed considerable popularity and large box office revenues within their own markets, which suggests among other things that “mainstream” and “avant garde” are culturally relative categories. So, too, the question of what counts as “mainstream” versus “avant garde” is inextricably bound up in related questions concerning the aesthetic “value” or “merit” of films. To many, “avant garde” film is remarkable chiefly for its artistic excellence, whereas “mainstream” film is little more than mass-produced pap. But who determines the standards for cinematic excellence, and how? As Dudley Andrews notes,

[...] [C]ulture is not a single thing but a competition among groups. And, competition is organized through power clusters we can think of as institutions. In our own field certain institutions stand out in marble buildings. The NEH is one; but in a different way, so is Hollywood, or at least the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Standard film critics constitute a sub-group of the communication institution, and film professors make up a parallel group, especially as they collect in conferences and in societies (Andrews, 1985: 55).

Andrews’ point here echoes one we made earlier — namely, that film criticism itself is a product of complicated power relations. Theoretical dichotomies such as “mainstream versus avant-garde” or “art versus pap” are manifestations of deeper socio-political conflicts which are subject to analysis in turn.

Even if there is or was such a thing as “avant-garde” cinema, it no longer functions in the way that Horkheimer and Adorno envisaged, if it ever did. As they themselves recognized, one of the most remarkable features of late capitalism is its ability to appropriate and commodify dissent. Friedberg, for example, is right to point out that flaneurie began as a transgressive institution which was subsequently captured by the culture industry; but the same is true even of “avant-garde” film — an idea that its champions frequently fail to acknowledge. Through the use of niche marketing and other such mechanisms, the postmodern culture industry has not only overcome the “threat” of the avant-garde but transformed that threat into one more commodity to be bought and sold. Media conglomerates make more money by establishing faux “independent” production companies (e.g., Sony Pictures Classics, Fox Searchlight Pictures, etc) and re-marketing “art films” (ala the Criterion Collection) than they would by simply ignoring independent, underground, avant-garde, etc. cinema altogether.

All of this is by way of expanding upon an earlier point — namely, that it is difficult, if not impossible, to determine the extent to which particular films or cinematic genres function as instruments of socio-political repression — especially in terms of simple dichotomies such as “mainstream” versus “avant-garde.” In light of our earlier discussion of Foucault, not to speak of Derrida, this ought not to come as a surprise. At the same time, however, we have ample reason to believe that the contemporary film industry is without question one of the preeminent mechanisms of global capitalist cultural hegemony. To see why this is the case, we ought briefly to consider some insights from Gilles Deleuze.

There is a clear parallel between Friedberg’s mobilized flaneurial gaze and what Deleuze calls the “nomadic” — i.e., those social formations which are exterior to repressive modern apparatuses like State and Capital (Deleuze & Guattari, 1987: 351–423). Like the nomad, the flaneur wanders aimlessly and without a predetermined telos through the striated space of these apparatuses. Her mobility itself, however, belongs to the sphere of non-territorialized smooth space, unconstrained by regimentation or structure, free-flowing, detached. The desire underlying this mobility is productive; it actively avoids satisfaction and seeks only to proliferate and perpetuate its own movement. Apparatuses of repression, in contrast, operate by striating space and routinizing, regimenting, or otherwise constraining mobile desire. They must appropriate the nomadic in order to function as apparatuses of repression.

Capitalism, however one understands its relationship to other repressive apparatuses, strives to commodify flaneurial desire, or, what comes to the same, to produce artificial desires which appropriate, capture, and ultimately absorb flaneurial desire (ibid., esp. 424–73). Deleuze would agree with Horkheimer and Adorno that the contemporary film industry serves a dual role as capture mechanism and as commodity. It not only functions as an object within capitalist exchange but as an ideological machine that reinforces the production of consumer-subjects. This poses a two-fold threat to freedom, at least as freedom is understood from a Deleuzean perspective: first, it makes nomadic mobility abstract and virtual, trapping it in striated space and marshaling it toward the perpetuation of repressive apparatuses; and second, it replaces the free-flowing desire of the nomadic with social desire — that is, it commodifies desire and appropriates flaneurie as a mode of capitalist production.

The crucial difference is that for Deleuze, as for Foucault and ACS, the relation between the nomadic and the social is always and already reciprocal. In one decidedly aphoristic passage, Deleuze claims there are only forces of desire and social forces (Deleuze & Guattari, [1972] 1977: 29). Although he tends to regard desire as a creative force (in the sense that it produces rather than represses its object) and the social as a force which “dams up, channels, and regulates” the flow of desire (ibid., 33), he does not mean to suggest that there are two distinct kinds of forces which differentially affect objects exterior to themselves. On the contrary, there is only a single, unitary force which manifests itself in particular “assemblages” (ibid.). Each of these assemblages, in turn, contains within itself both desire and various “bureaucratic or fascist pieces” which seek to subjugate and annihilate that desire (Deleuze & Guattari, 1986: 60; Deleuze & Parnet, 1987: 133). Neither force acts or works upon preexistent objects; rather everything that exists is alternately created and/or destroyed in accordance with the particular assemblage which gives rise to it.

There is scarcely any question that the contemporary film industry is subservient to repressive apparatuses such as transnational capital and the government of the United States. The fact that the production of films is overwhelmingly controlled by a handful of media conglomerates, the interests of which are routinely protected by federal institutions at the expense of consumer autonomy, makes this abundantly clear. It also reinforces the naivety of cultural studies, whose valorization of consumer subcultures appears totally impotent in the face of such enormous power. As Richard Hoggart notes,

Studies of this kind habitually ignore or underplay the fact that these groups are almost entirely enclosed from and are refusing even to attempt to cope with the public life of their societies. That rejection cannot reasonably be given some idealistic ideological foundation. It is a rejection, certainly, and in that rejection may be making some implicit criticisms of the ‘hegemony,’ and those criticisms need to be understood. But such groups are doing nothing about it except to retreat (Hoggart, 1995: 186).

Even if we overlook the Deleuzean/Foucauldian/ACS critique — viz., that cultural studies relies on a theoretically problematic notion of consumer “agency” — such agency appears largely impotent at the level of praxis as well.

Nor is there any question that the global proliferation of Hollywood cinema is part of a broader imperialist movement in geopolitics. Whether consciously or unconsciously, American films reflect and reinforce uniquely capitalist values and to this extent pose a threat to the political, economic, and cultural sovereignty of other nations and peoples. It is for the most part naïve of cultural studies critics to assign “agency” to non-American consumers who are not only saturated with alien commodities but increasingly denied the ability to produce and consume native commodities. At the same time, none of this entails that competing film industries are by definition “liberatory.” Global capitalism is not the sole or even the principal locus of repressive power; it is merely one manifestation of such power among many. Ostensibly anti-capitalist or counter-hegemonic movements at the level of culture can and often do become repressive in their own right — as, for example, in the case of nationalist cinemas which advocate terrorism, religious fundamentalism, and the subjugation of women under the banner of “anti-imperialism.”

The point here, which reinforces several ideas already introduced, is that neither the American film industry nor film industries as such are intrinsically reducible to a unitary source of repressive power. As a social formation or assemblage, cinema is a product of a complex array of forces. To this extent it always and already contains both potentially liberatory and potentially repressive components. In other words, a genuinely nomadic cinema — one which deterritorializes itself and escapes the overcoding of repressive state apparatuses — is not only possible but in some sense inevitable. Such a cinema, moreover, will emerge neither on the side of the producer nor of the consumer, but rather in the complex interstices that exist between them. I therefore agree with Cohn that anarchist cultural studies (and, by extension, anarchist film theory) has as one of its chief goals the “extrapolation” of latent revolutionary ideas in cultural practices and products (where “extrapolation” is understood in the sense of actively and creatively realizing possibilities rather than simply “discovering” actualities already present) (Cohn, 2009: 412). At the same time, I believe anarchist film theory must play a role in creating a new and distinctively anarchist cinema — “a cinema of liberation.”

Such a cinema would perforce involve alliances between artists and audiences with a mind to blurring such distinctions altogether. It would be the responsibility neither of an elite “avant-garde” which produces underground films, nor of subaltern consumer “cults” which produce fanzines and organize conventions in an attempt to appropriate and “talk back to” mainstream films. As we have seen, apparatuses of repression easily overcode both such strategies. By effectively dismantling rigid distinctions between producers and consumers, its films would be financed, produced, distributed, and displayed by and for their intended audiences. However, far from being a mere reiteration of the independent or DIY ethic — which, again, has been appropriated time and again by the culture industry — anarchist cinema would be self — consciously political at the level of form and content; its medium and message would be unambiguously anti — authoritarian, unequivocally opposed to all forms of repressive power.

Lastly, anarchist cinema would retain an emphasis on artistic integrity — the putative value of innovative cinematography, say, or compelling narrative. It would, in other words, seek to preserve and expand upon whatever makes cinema powerful as a medium and as an art-form. This refusal to relegate cinema to either a mere commodity form or a mere vehicle of propaganda is itself an act of refusal replete with political potential. The ultimate liberation of cinema from the discourse of political struggle is arguably the one cinematic development that would not, and could not, be appropriated and commodified by repressive social formations.

In this essay I have drawn upon the insights of Foucault and Deleuze to sketch an “anarchist” approach to the analysis of film — on which constitutes a middle ground between the “top-down” theories of the Frankfurt School and the “bottom-up” theories of cultural studies. Though I agree with Horkheimer and Adorno that cinema can be used as an instrument of repression, as is undoubtedly the case with the contemporary film industry, I have argued at length that cinema as such is neither inherently repressive nor inherently liberatory. Furthermore, I have demonstrated that the politics of cinema cannot be situated exclusively in the designs of the culture industry nor in the interpretations and responses of consumer-subjects. An anarchist analysis of cinema must emerge precisely where cinema itself does — at the intersection of mutually reinforcing forces of production and consumption.

#cinema#film theory#movies#anarchist film theory#culture industry#culture#deconstruction#humanism#truth#the politics of cinema#anarchism#anarchy#anarchist society#practical anarchy#practical anarchism#resistance#autonomy#revolution#communism#anti capitalist#anti capitalism#late stage capitalism#daily posts#libraries#leftism#social issues#anarchy works#anarchist library#survival#freedom

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Free Palestinian film archive via google docs

231 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lacombe, Lucien (1974)

Director : Louis Malle

Director of Photography : Tonino Delli Colli

#Louis Malle#Tonino Delli Colli#Lacombe#Lucien#lacombe lucien#wwii#cinematography#cinematographer#cinema#movie#dop#film#film stills#film still#france#world war 2#gestapo#resistance

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

“I Drove Over Hundreds Of Palestinians In Gaza With Bulldozers”

They accused the Palestinians of being human-animals.

Those Zionists are neither human nor animals.

They are Demons!

May God always curse them!

#photography#palestine#gaza#free palestine#islamophobia#israel#free gaza#gaza genocide#gaza strip#gazaunderattack#palestine genocide#palestinian lives matter#palestinian genocide#justice for palestinians#save palestinians#palestinian resistance#free palastine#long live palestine#gaza news#palestinian cinema#palestinian civilians#palestinian hostages#palestinian history#palestinian heroes#genocide#israel is committing genocide#stop the genocide#end the genocide#ethnic cleansing#war crimes

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

Original one was on paper rsrsrssrrs

#se7en (1995)#se7en#david mills#brad pitt#fanart#art#yes the red things are just excuse to the sedond eye...i hate to draw the second eye#I rewatched the other day at the cinema and I couldn't resist#coverede on blood..#suck the quality tumblr!!

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Grapes of Wrath (1940) Directed by John Ford

#the grapes of wrath#john ford#1940#american classic#great depression#dust bowl#road movie#henry fonda#social realism#steinbeck adaptation#cinematic storytelling#family and survival#struggle and hope#new deal era#cinema of resistance#visual poetry#black and white cinema#hollywood golden age#timeless storytelling#cinema of the people#social justice film#classic literature adaptation#historical drama#1940s movies

1 note

·

View note

Text

instagram

#billford#gravity falls#the book of bill#bill cipher#bill x ford#save palestine#gravity falls bill#peter maximoff#all eyes on palestine#donate to palestine#palestinian solidarity#palestinian children#palestinian culture#palestine resistance#palestinian state#palestinian cinema#palestinian art#palestinian authority#palestinian#palestine news#i stand with palestine#free palestine#palestinian genocide#instagram#instagood#source: instagram#palestine flag#palestine family#palestine liberation#palestine children

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

if this gets one like i will wear my markiplier crop top to the fnaf movie later today. yeah ik its a fucking insane thing to own my mum got it for me. also its absolutely freezing today so its a horrible idea but consider. its also hilarious

#if you are the provider of the like please know it is the equivalent of you daring me to do it bc i cant resist a dare lmao#ok to reblog#beep beep gets personal#personal#textpost#text post#fnaf#fnaf movie#five nights at freddys#five nights at freddy's#cinema#movie#film#markiplier#crop top#cold#hilarious

64 notes

·

View notes

Text

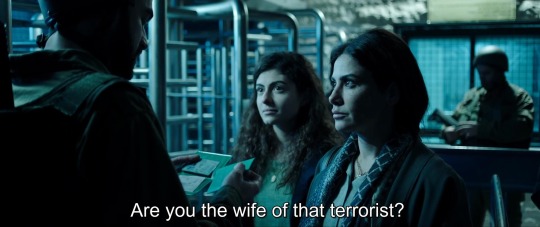

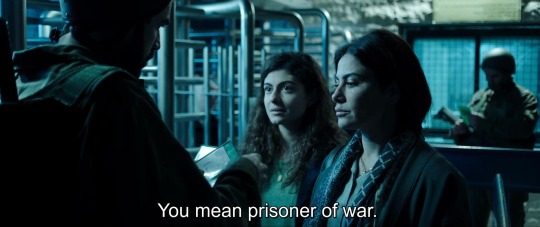

أميرة [Amira] (Mohamed Diab, 2021)

#أميرة#Mohamed Diab#Amira#Palestine#فلسطين#פלשתינה#Israeli occupation#Gaza Strip#West Bank#resistance#liberation#Palestinian society#Tara Abboud#Saba Mubarak#Ali Suliman#Ziad Bakri#Waleed Zuaiter#Saleh Bakri#Kais Nashef#middle east cinema#2020s movies#segregation#apartheid#freedom#drama film#occupied territories#Arab people#Middle East#SWANA#love

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

DAVID ARGUE as Dicko Baker in RAZORBACK (1984) dir. Russell Mulcahy

#I can't resist a stinky little rat boy#so I had to make a gifset just for him 😅#david argue#razorback 1984#australian horror#horroredit#horrorgifs#horrorfilmgifs#userhorroredits#classichorrorblog#societyclub#fyeahmovies#junkfooddaily#dailyflicks#80s cinema#80s horror#crumbedit

109 notes

·

View notes