#catherine eddowes

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

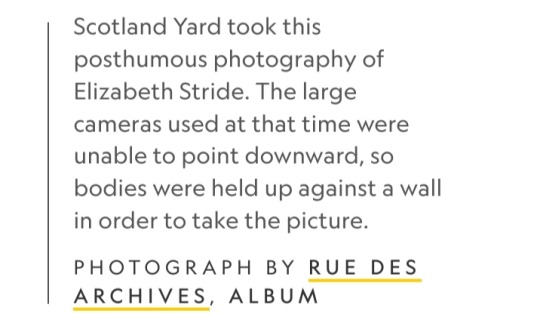

By Parissa DJangi

August 18, 2023

Some say he was a surgeon. Others, a deranged madman — or perhaps a butcher, prince, artist, or specter.

The murderer known to history as Jack the Ripper terrorized London 135 years ago this fall.

In the subsequent century, he has been everything to everyone, a dark shadow on which we pin our fears and attitudes.

But to five women, Jack the Ripper was not a legendary phantom or a character from a detective novel — he was the person who horrifically ended their lives.

“Jack the Ripper was a real person who killed real people,” reiterates historian Hallie Rubenhold, whose book, The Five, chronicles the lives of his victims. “He wasn’t a legend.”

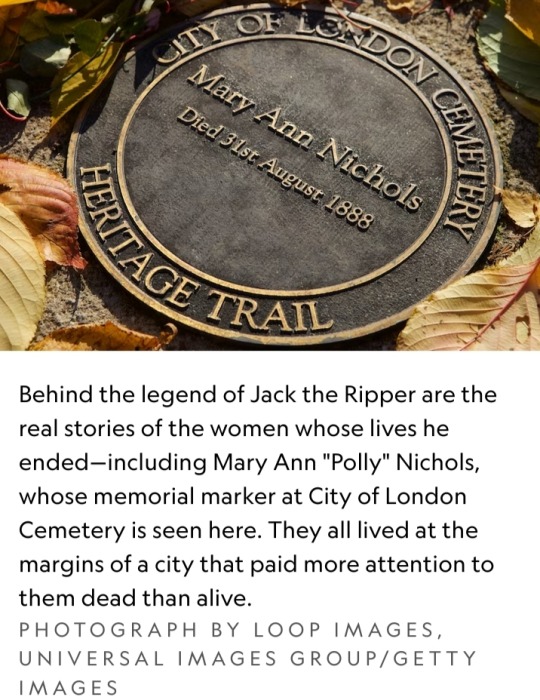

Who were these women? They had names: Mary Ann “Polly” Nichols, Annie Chapman, Elizabeth Stride, Catherine Eddowes, and Mary Jane Kelly.

They also had hopes, loved ones, friends, and, in some cases, children.

Their lives, each one unique, tell the story of 19th-century London, a city that pushed them to its margins and paid more attention to them dead than alive.

Terror in Whitechapel

Their stories did not all begin in London, but they ended there, in and around the crowded corner of the metropolis known as Whitechapel, a district in London’s East End.

“Probably there is no such spectacle in the whole world as that of this immense, neglected, forgotten great city of East London,” Walter Bessant wrote in his novel All Sorts and Conditions of Men in 1882.

“It is even neglected by its own citizens, who had never yet perceived their abandoned condition.”

The “abandoned” citizens of Whitechapel included some of the city’s poorest residents.

Immigrants, transient laborers, families, single women, thieves — they all crushed together in overflowing tenements, slums, and workhouses.

According to historian Judith Walkowitz:

“By the 1880s, Whitechapel had come to epitomize the social ills of ‘Outcast London,’ a place where sin and poverty comingled in the Victorian imagination, shocking the middle classes."

Whitechapel transformed into a scene of horror when the lifeless, mutilated body of Polly Nichols was discovered on a dark street in the early morning hours of August 31, 1888.

She became the first of Jack the Ripper’s five canonical victims, the core group of women whose murders appeared to be related and occurred over a short span of time.

Over the next month, three more murdered women would be found on the streets of the East End.

They had been killed in a similar way: their throats slashed, and, in most cases, their abdomens disemboweled.

Some victims’ organs had been removed. The fifth murder occurred on November 9, when the Ripper butchered Mary Jane Kelly with such barbarity that she was nearly unrecognizable.

This so-called “Autumn of Terror” pushed Whitechapel and the entire city into a panic, and the serial killer’s mysterious identity only heightened the drama.

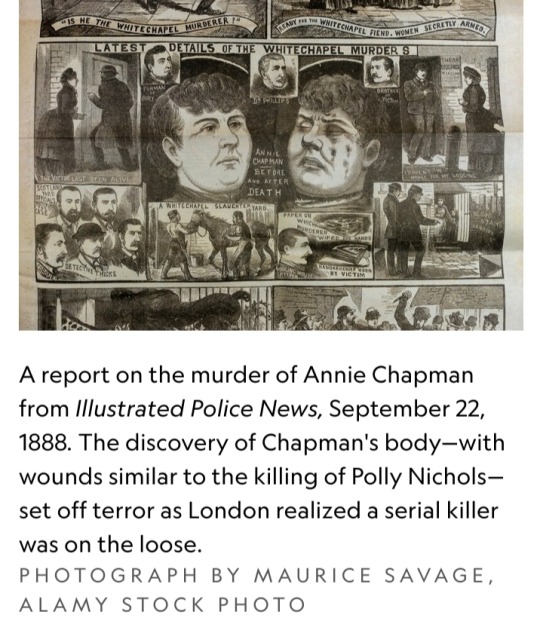

The press sensationalized the astonishingly grisly murders — and the lives of the murdered women.

Polly, Annie, Elizabeth, Catherine, and Mary Jane

Though forever linked by the manner of their death, the five women murdered by Jack the Ripper shared something else in common:

They were among London’s most vulnerable residents, living on the margins of Victorian society.

They eked out a life in the East End, drifting in and out of workhouses, piecing together casual jobs, and pawning their few possessions to afford a bed for a night in a lodging house.

If they could not scrape together the coins, they simply slept on the street.

“Nobody cared about who these women were at all,” Rubenhold says. “Their lives were incredibly precarious.”

Polly Nichols knew precarity well. Born in 1845, she fulfilled the Victorian ideal of proper womanhood when she became a wife at the age of 18.

But after bearing five children, she ultimately left her husband under suspicions of his infidelity.

Alcohol became both a crutch and curse for her in the final years of her life.

Alcohol also hastened Annie Chapman’s estrangement from what was considered a respectable life.

Annie Chapman was born in 1840 and spent most of her life in London and Berkshire.

With her marriage to John Chapman, a coachman, in 1869, Annie positioned herself in the top tier of the working class.

But her taste for alcohol and the loss of her children unraveled her family life, and Annie ended up in the East End.

Swedish-born Elizabeth Stride was an immigrant, like thousands of others who lived in the East End.

Born in 1843, she came to England when she was 22. In London, Stride reinvented herself time and time again, becoming a wife and coffeehouse owner.

Catherine Eddowes, who was born in Wolverhampton in 1842 and moved to London as a child, lost both of her parents by the time she was 15.

She spent most of her adulthood with one man, who fathered her children. Before her murder, she had just returned to London after picking hops in Kent, a popular summer ritual for working-class Londoners.

At 25, Mary Jane Kelly was the youngest, and most mysterious, of the Ripper’s victims.

Kelly reportedly claimed she came from Ireland and Wales before settling in London.

She had a small luxury that the others did not: She rented a room with a bed. It would become the scene of her murder.

Yet the longstanding belief that all of these women were sex workers is a myth, as Rubenhold demonstrates in The Five.

Only two of the women — Stride and Kelly — were known to have engaged in sex work during their lives.

The fact that all of them have been labeled sex workers highlights how Victorians saw poor, unhoused women.

“They have been systematically ‘othered’ from society,” Rubenhold says,"even though this is how the majority lived.”

These women were human beings with a strong sense of personhood. According to biographer Robert Hume, their friends and neighbors described them as “industrious,” “jolly,” and “very clean.”

They lived, they loved, they existed — until, very suddenly on a dark night in 1888, they did not.

A long shadow

The discovery of Annie Chapman’s body on September 8 heightened panic in London, since her wounds echoed the shocking brutality of Polly Nichols’ murder days earlier.

Investigators realized that the same killer had likely committed both crimes — and he was still on the loose. Who would he strike next?

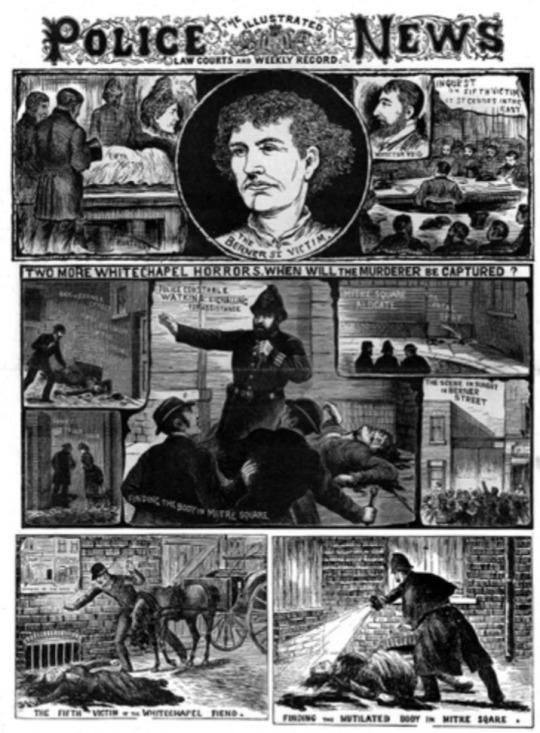

In late September, London’s Central News Office received a red-inked letter that claimed to be from the murderer. It was signed “Jack the Ripper.”

Papers across the city took the name and ran with it. Press coverage of the Whitechapel Murders crescendoed to a fever pitch.

Newspapers danced the line between fact and fiction, breathlessly recounting every gruesome detail of the crimes and speculating with wild abandon about the killer’s identity.

Today, that impulse endures, and armchair detectives and professional investigators alike have proposed an endless parade of suspects, including artist Walter Sickert, writer Lewis Carroll, sailor Carl Feigenbaum, and Aaron Kosminski, an East End barber.

"The continued fascination with unmasking the murderer perpetuates this idea that Jack the Ripper is a game,” Rubenhold says.

She sees parallels between the gamification of the Whitechapel Murders and the modern-day obsession with true crime.

“When we approach true crime, most of the time we approach as if it was legend, as if it wasn’t real, as if it didn’t happen to real people.”

“These crimes still happen today, and we are still not interested in the victims,” Rubenhold laments.

The Whitechapel Murders remain unsolved after 135 years, and Rubenhold believes that will never change:

“We’re not going to find anything that categorically tells us who Jack the Ripper is.”

Instead, the murders tell us about the values of the 19th century — and the 21st.

#Jack the Ripper#Hallie Rubenhold#The Five#Mary Ann “Polly” Nichols#Annie Chapman#Elizabeth Stride#Catherine Eddowes#Mary Jane Kelly#19th-century#1800s#Whitechapel#London#Walter Bessant#Judith Walkowitz#Outcast London#East End#Autumn of Terror#Victorian society#Victorian era#Robert Hume#1888#Central News Office#Whitechapel Murders#Whitechapel Murderer#Leather Apron#murder#crime#mystery#unsolved case#National Geographic

94 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hey guys this is your occasional reminder that using song lyrics as evidence in a criminal trial is kinda bullshit. K thanx

#yes this is about the#young thug#trial#music#but also it's so fucking stupid#if your evidence is so freaking weak#you have to use SONG LYRICS#you need to be examining the merits of your case#rap music#these people need to listen to#bluegrass music#or study#jack the ripper#the canonical five#catherine eddowes

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

CATHERINE EDDOWES

Catherine Eddowes, 46 years old. Her body was found on September 30 in Miter Square in a pool of blood and in a supine position, like all the other victims. The woman had been subjected to a real martyrdom by the assassin, who, having failed to inflict violence on the previous victim, would have sought a second victim to attack. The face was completely disfigured and unrecognizable except for the color of the eyes. The face was disfigured with a "V" cut. Not very far from the crime scene, more precisely in Goulston street around 2:55 in the morning, a bloody section of Eddowes' apron was found and a graffiti directly above the apron piece which read: "Jews are those that they will not be accused of anything". The message seemed to imply that a Jew or several Jews in general were responsible for the series of murders.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

#catherine eddowes#illustrated police news#mitre square#ripper victim#jack the ripper#whitechapel murders#victorian history#circa 1888#victorian#ripperology#true crime#true crime meme#ripper memes#newspaper#london 1888#london

1 note

·

View note

Text

0 notes

Text

*Check out our blogspot for victorian Whitechapel here*

World Television Day

On the 21st of November is World Television Day. Obviously, on Victorian times the TV didn't exist yet, but there are some TV films, series and mini-series that portrayed the Whitechapel Murder Victims. As a way of tributing these women, we decided to celebrate World Television Day by posting TV shows that featured them.

Jack The Ripper (1988 mini series):

In this TV mini-series starring Michael Caine, Annie Chapman is played by Deirdre Costello:

Angela Crow plays Liz Stride:

Susan George plays Catherine Eddowes:

And Lysette Anthony plays the role of Mary Kelly:

The Ripper (1997 TV film):

In this TV movie, Josephine Keen plays the role of Elizabeth Stride:

Catherine Eddowes is played by an unknown actress (please, contact me if you can identify her!):

And Mary Kelly is played by Karen Davitt:

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Lost World (2001 TV Series):

In this fantasy TV series, there is an episode about the Whitechapel murders, the 5th episode of the 3rd season called "The Knife".

In it, Jennifer O'Dell plays Catherine Eddowes:

And Rachel Blakely plays the role of Mary Kelly:

--

PS: As Tumblr only allows to post 10 photos in one post, I cannot post the shows posters.

#World Television Day#Special Dates#Popular Culture#TV#Jack The Ripper 1988#Annie Chapman#Deirdre Costello#Angela Crow#Elizabeth Stride#Susan George#Catherine Eddowes#Lysette Anthony#Mary Kelly#The Ripper 1997#Josephine Keen#Karen Davitt#The Knife#Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Lost World#Jennifer O'Dell#Rachel Blackely#TV film#TV movie#TV series#tv mini series#victims#muse#victorian inspired#victorian inspiration#victorian today#links

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wot on erf... Started reading Theodora: Actress Empress Saint and there's like... just copy editing stuff within the first few pages... Saying Theodora "had born [sic] a daughter"? It's "borne," sir... Describing an image depicting kids cheering at chariot races, saying "the images of children cheering her [sic] may show us one of Theodora's own activities"? Um... And it's written by this person?

David Stone Potter (born 1957) is the Francis W. Kelsey Collegiate Professor of Greek and Roman History and the Arthur F. Thurnau Professor, Professor of Greek and Latin in Ancient History at The University of Michigan. Potter is a graduate of Harvard (A.B. 1979) and Oxford (D.Phil 1984) universities and specializes in Greek and Roman Asia Minor, Greek, and Latin historiography and epigraphy, Roman public entertainment, and the study of ancient warfare.[1]

You can graduate Harvard and Oxford and not know this stuff? This is like when I was reading Femina by Janina Ramirez and she didn't know the difference between "grisly" and "grizzly." She studied at Oxford too

#sorry but this stuff just makes me sooooooo doubtful and i know it's ridiculous#this is like when judith flanders got a minor detail in catherine eddowes' murder wrong in 'the invention of murder'#and i immediately started doubting the whole book :(

7 notes

·

View notes

Link

In this episode of the Family Plot Podcast we talk Jack the Ripper! His most likely victims, the area of Whitechapel in 1888, suspects and so much more. Krysta talks her love interest Bunny and about life on a high school debate team in her Catching Up with Krysta segment in our final spooky season episode of the Family Plot Podcast!

#polly#annie#apron#catherine#chapman#eddowes#jack#kelly#leather#liz#martha#mary#nichols#ripper#saucy#spitalfields#stride#tabram#the#whitechapel

0 notes

Note

Same anon that just sent the post about the victims of Jack the Ripper. I looked up more about them, and found out that all of them struggled with alcoholism and alcohol addiction. Catherine Eddowes reported to be in an abusive relationship, and it seems like most of them had turned to sex work to survive.

I just. It’s. Upsetting. The way this is being used in the show. And maybe it’s petty and nitpickey of me but. I just see the story now using the deaths of these women, who dealt with a lot of struggles in life, specifically to give “lore” and sympathetic backstory to a fictional character. And their struggles are something the story claims to respect and want to raise awareness about. And I just. I don’t know. It feels like their murders are being used in a gross way to me. I think I may just be too sensitive but. It’s just. A lot.

I don't think you're too sensitive at all. These were real women who had hard lives and absolutely brutal deaths, and Viv appropriated them for her OC's sob story without researching who they were as people or giving a shit about them at all.

73 notes

·

View notes

Text

Around the World Part 7

I know I said that Nanny would be out this week, but I just finished this and am really wanting to get it out as soon as possible and that includes the epilogue.

But if I time it right, this series and Hellfire will end the same week and I'll be able to return to some kind of normal schedule instead of pumping these out on a fucking grinder.

That said, I probably won't do a Christmas story with the way things are right now. But we'll see the closer we get to the holiday.

In this we get the proper Jack the Ripper tour and the author has opinions, okay! Steve draws attention to himself at the Paris Opera house. Murray is a bit too knowing. And of course as @val-from-lawrence guessed, visited the Catacombs!

Part 1 Part 2 Part 3 Part 4 Part 5 Part 6

~

They had done the Tower of London and St. Paul’s Cathedral during the day and got ready for the Bauman Experience as Murray called it. They all had a flashlight and went to go meet him where they had the night before.

They caught him dealing with some obnoxious tourists.

“Oh thank god!” the Karen cried. “An American. Could you please explain to this woman that we only have dollars to pay with. She has to take it!”

Murray blinked at her for a moment. “Well that is quite the cock up, you absolute muppet. Are you dead from the neck up? British pound sterling is the brass here, you silly cow!”

The woman’s head reared back in shock, clutching her chest. “I beg your pardon!”

“To make it perfectly clear,” Murray said leaning forward into her space. “You fucked up, you moron. Are you really that stupid? Dollars aren’t the currency here, the British pound is. Just like you can’t use the pound anywhere but here, you can’t use the dollar anywhere but America so why don’t you go to an ATM or bank and get it exchanged. Or and here’s the really neat part about living in the age of technology, use or credit or debit card and your bank does the conversion for you.”

When she started sputtering angrily, Murray waved her off. “Now, shoo! I’ve got actual paying customers waiting for me.”

Murray turned to the four of them with a smiled. “Well, hello! Welcome. Now that things are dark and therefore sufficiently spooky, let’s take you on a proper tour of Jack’s slaying grounds.”

He went through the different murders until he got to the double murders of Elizabeth Stride and Catherine Eddowes.

“Now,” he said, rubbing his chin thoughtfully, “Miss Stride is usually considered his third victim and that he was interrupted, moving on to Miss Eddowes. But I think Stride was a copycat. The person only knew the bodies were mutilated, but not how. So for me, I don’t count her in the confirmed kills.”

Robin nodded sagely. “I don’t either. There was far too little evidence to prove he had been frightened off, because otherwise Eddowes would have been more brutal than it was. He would have been angry he couldn’t finish with Stride. You would have expected her to look like what Mary Kelly’s body looked like, not cool and calm.”

Murray smiled up at her. He turned to Eddie. “I really like her. She’s clever.”

Robin blushed and ducked her head.

A short time later, just as they were wrapping up the Kelly murder, Murray stopped. He looked at a pair of older teenagers and then back at the group.

Chrissy picked up on it first. “You thinking what, I’m thinking, Mur?”

Murray turned to her and cocked his head to the side, considering. He nodded and Chrissy pursed her lips.

Steve caught on just as quick. “Eds, baby. I think those boys may have guessed who you are, love.”

Robin and Eddie shared a concerned glance.

“Fuck,” Eddie huffed. “I liked this jacket.”

Robin grabbed it from him and gave him her jacket. “Mine doesn’t look as fancy,” she explained pulling his jacket on. “Just like Boston, peeps!”

Murray tilted his head to the side and did a quick Google search. “Or... if you’d like, my car is literally around the corner.”

The four of them stopped swapping clothes and looked up at him.

“That’s easier,” Steve said. “Who’s all for easier?”

The other three raised their hands and they followed Murray to his car. Robin sat up front while Steve and Chrissy covered Eddie between them.

“Drop me off at the hotel,” Steve said, tapping on Murray’s shoulder. “I’ll check us out and then meet you at Shakespeare’s Head.”

Murray looked behind him and grinned. “Smart thinking.”

~

Eddie had changed into a trucker hat and a puffy hunting vest over sturdy blue jeans and thick work boots.

“Kids and their cameras these day,” Murray huffed, sliding a pint of beer over at Steve as he sat down between Robin and Chrissy. “So what’s the story with loverboy here?” he asked Eddie, cocking his head to indicate Steve.

“He’s not out,” Eddie said dryly. “His parents are complete assholes who could and would make things very difficult for him if he was.”

“Nothing says asshole parents,” Murray said with a nod, “quite like those that have the money to make you miserable.”

Steve snorted. “You’ve got that right. But I’m more than equipped to make it work.” He half shrugged. “I’ve been doing it for almost a year.”

Murray’s went wide and he gave an opened mouthed smile. “Have you really? I would have never guessed. Good job! ”

“How did you spot the kids, by the way?” Robin asked around her fruity cocktail.

“Oh,” Murray said, ducking his head a bit. “You’re walking around a small group of people at night in a bad area of London. Whitechapel isn’t as bad as it was in Jackie’s time, but it’s still not a good neighborhood. You have to keep an eye out for people, but especially older teens wishing to knock you over for a bit of loose change.”

Steve cleared his throat and ducked his head. “I am about to ask the most bougie question imaginable. And you can tell me to go to hell if I’m out of line here.”

Murray’s eyebrows went up and he leaned back in his chair. “Wha’cha got, kid?”

Steve licked his lower lip as he tried to word this in a way that wasn’t instantly offensive. “How entrenched are you in this job?”

“Not very,” he replied with a shrug. “I’m just moving through the world enjoying myself and taking jobs that would be fun. I’ve got more than enough money. Why?”

“We were talking in our group chat,” Chrissy explained taking over from a very embarrassed Steve, “and we thought we’d offer you a job as main look out and part time driver for when we’re in Europe. You really saved Eddie today and we could really use someone like you with us.”

Murray glared at her. “You sure I wouldn’t cramp your little foursome you’ve got going on here’s style?” He made a little circling motion with his hand to indicate all of them.

Robin shook her head. “It’ll make it harder for people to recognize a quartet if it suddenly became a quintet. Plus, we’d pay for your room and board. None of us are skint, believe you me.”

“We’ll be staying in haunted hotels, motels, and bed and breakfasts,” Eddie added. “But we won’t force you to join us. We can put you up in a nice place nearby and we join back up whenever we go out.”

Murray eyed them suspiciously until Steve slid over an envelope. He picked it up and pulled out a check. His eyes went wide. “That’s quite the pretty penny.”

“That’s half,” Robin huffed, crossing her arms and throwing herself against the back of the chair. “You’ll get the other half once we leave Europe for Asia.”

“All that for a month’s worth of driving you four around and making sure fans and paparazzi don’t find Eddie here?” Murray asked. “Have you gone crazy?”

Eddie shook his head. “We just want a romantic tour of the spooky places of Europe. I hate the thought Steve getting caught up in something just because I’m recognized everywhere I go and he isn’t.”

Murray licked his lips slowly as his eyes narrowed. “That’s not how that’s usually said.”

Steve frowned and tilted his head to the side. “What do you mean? How is what said?”

Robin put her hand on his elbow as he bristled slightly at his tone.

“Usually people will say ‘famous and they’re not’,” Murray said thoughtfully, “he said ‘recognized’. Meaning Stevie here is famous too, but not in a way people would recognize him on the street. What is a famous painter or some shit?”

She cocked her to the side and said dryly, “If I told you that, I’d have to kill you.”

Murray laughed. Just full on cackled. “Have I mentioned how much I like her? Because I really like her.”

Eddie leaned forward to put his elbows on the table. “So what do you say, Murray?” he asked tilting his head to the side. “You want to work for me again?”

Murray slipped the check into his coat pocket and stuck out his hand. “I think you’ve got yourself a deal.”

~

Their first stop on the Continent was Paris and the catacombs. Eddie was still trying to figure out how Robin did that one. It had been closed to the public for years.

Robin just smirked and said, “Well we aren’t the public.”

Steve was also sure they didn’t open it up to anyone who opened their wallet, either, but wisely stayed silent. Plus he was having fun watching Chrissy and Robin run circles around Murray in terms of sheer knowledge.

“Um...Stevie?” Eddie murmured so the trio couldn’t hear him. “Can I hold your hand? It’s getting a little creepy in here.”

Steve held out his hand, the one that had the little guitar on the inner wrist. Eddie looked down at the offered hand with a fond smile. He took the offered hand and their tattoos matched up. Eddie felt braver with every step knowing that Steve would always be there to hold his hand through the darkness.

Chrissy looked back at them and grinned at their clasped hands. She sped up her walk just a little, forcing Murray and Robin to speed up to match her pace, leaving the two love birds the privacy they so richly deserved.

Once they were out in the sunlight and among the city once again, Eddie refused to let go of Steve’s hand.

Steve looked at their joined hands and then back at Eddie. Eddie gave him his brightest smile and Steve was smitten. Even more so than before. He just loved him so much.

They toured the Paris Opera house and Eddie pulled out a cape and mask.

“Sing for me my angel of music!” he said to Chrissy.

She burst out laughing. “My name may be Christine, but I really don’t think they’d want me shattering the glass.”

Eddie turned to Robin who waved her arms in front of her. “No way! I sing like a frog in heat!”

“No.” Was all Murray said.

Steve raised an eyebrow and Eddie grinned.

“Sing!” Eddie crowed.

Steve took a deep breath and belted out that high note, held it perfectly and then took a bow.

Murray blinked and slow smile spread over his features. “You’re in one of those bands with the masks aren’t you? Like Sleep Token or The Fallen, huh? That’s Eddie here said recognized and not famous. Good on you.”

They all shared looks of concern.

“I’m not going to tell anyone,” Murray huffed, holding up his hands in surrender. “And I’m certainly not even going to try and guess which band it is.” He pulled out his phone and messed around on it for a while.

During which they all watched with ever increasing dread. The silence seemed to stretch out on and on.

Then Chrissy’s phone pinged. Everyone jumped as she scrambled for her phone. She opened it up and blinked a moment.

“You signed a blanket statement NDA?” she asked handing her phone to Robin. “Why?”

Murray licked his lips and crossed his arms over his chest. “Did it suck when Corroded Coffin pulled out of my management causing a shit ton of other people pulling out, too? Sure. But that’s the nature of the business. One that I had been in for over twenty years. I took it as a sign from the universe to retire and enjoy my life. Unlike the CC boys pulling out on Nancy Wheeler because she about to do some pretty shady shit. And I say that having been part of a business that used to be built on shady ass shit.”

Chrissy coughed and looked away to hide her smile.

“I’m guessing Steve’s band is why Corroded Coffin went nuclear on her in the first place?”

Steve looked over at Eddie and then nodded. “She was an ex-girlfriend and she tried to hold that over my head to get me to work with her.”

Murray let out a long and low whistle. “Shady doesn’t even begin to cover that shit. The void would be fucking closer. Shit.”

Robin handed back Chrissy her phone. “How did you get an NDA that fast anyway?”

“Oh that?” Murray asked with a huff of laughter. “I have a bunch of basic contracts and shit in my Google docs. Things can move fast in this business and it’s a good idea to keep a few on hand. Back in the old days we kept them in our briefcases that we carted around. This is sooo much easier.”

“Smart.”

Murray grinned back at her. He turned to Steve. “Come on, show us what that classical vocal training can really do.”

Steve blushed and began warming up his vocals as Robin grinned.

“You may think you’ve heard Steve sing,” she crowed, “but you’ve ain’t seen nothing yet.”

Then Steve really opened up and began to sing. There was a deepness to his voice that didn’t have anything to do with his range. He was clearly a tenor, but the rich quality to his voice just elevated it somehow.

“Rigoletto,” Murray said nodding appreciatively. “Well done.” He clapped slowly, but it wasn’t mocking. “Your parents must have been livid when you didn’t go into opera.”

Steve snorted. “About as angry as when they found out I was bisexual. They know what I am but if I go public with it...”

“They’ll make your life a nightmare?” he asked. Steve nodded. “I feel for you, kid.”

He looked around and grimaced. “I thick it’s time we make like Opera Ghost and scram. That performance of Steve’s here, is getting more attention than I thought it would.”

They looked around and sure enough there were people pointing at Steve.

“I’m not sure what the Venn diagram of opera and metal fans,” Chrissy said, “but I’m betting it’s not two separate circles.”

“Yeaahhh,” Eddie said with a wince.

He grabbed Steve’s hand and they ran for the doors. Murray and the girls hot on their heels.

~

Part 8 Part 9

Tag List: CLOSED

1- @mira-jadeamethyst @rozzieroos @itsall-taken @redfreckledwolf @zerokrox-blog

2- @gregre369 @a-little-unsteddie @chaosgremlinmunson @messrs-weasley @val-from-lawrence

3- @goodolefashionedloverboi @carlyv @wonderland-girl143-blog @irregular-child @blondie1006

4- @yikes-a-bee @bookworm0690 @anne-bennett-cosplayer @awkwardgravity1 @littlewildflowerkitten

5- @genderless-spoon @y4r3luv @dragonmama76 @ellietheasexylibrarian @thedragonsaunt

6- @disrespectedgoatman @dawners @thespaceantwhowrites @tinyplanet95 @garden-of-gay

7- @iamthehybrid @croatoan-like-its-hot @papergrenade @cryptid-system @counting-dollars-counting-stars

8- @ravenfrog @w1ll0wtr33 @child-of-cthulhu @kultiras @dreamercec

9- @machete-inventory-manager @useless-nb-bisexual @stripey82 @dotdot-wierdlife @kal-ology

10- @sadisticaltarts @urkadop @chameleonhair @clockworkballerina

#my writing#stranger things#steddie#ladykailtiha writes#rockstar au#rockstar steve harrington#rockstar eddie munson

63 notes

·

View notes

Text

THE JACK THE RIPPER CASE IN YUUMORI AND IN REALITY

One of my favourite arcs is the Phantom of Whitechapel because it adapted the real Jack the Ripper case quite well and the story was full of elements what actually happened. I wanted to write a little about the similarities as recently was the anniversary of the first murder.

The Jack the Ripper murders or Whitechapel murders took place in 1888 in the East End of London, the infamously poor Whitechapel district where the underclass people lived. Lot of women here earned their money for the living from selling their bodies and a serial killer, Jack the Ripper started to target them. The number of the victims is unsure, the police accepted five murders to be surely connected to Jack the Ripper, they are often referred to as the canonical five. The women got murdered by their throats being cut away and some of their inestines were also removed from their bodies.

The first victim was called Mary Ann Nichols whose body was discovered at 3:40 a.m. on 31th August. She was last seen alive by a woman she lived with in a lodging house. These all are very similar to how Moriarty the Patriot described the murder details, except that there, the victim's name was Melanie Nichols and she was seen with a blond man.

The second victim was Annie Chapman, her body was found at 6 a.m on 8th September and she was last seen half an hour ago in a company of a dark-haired man. The details shown in Yuumori are again similar, just the victim was called Adeline Bergman.

(Interesting addition to here - just like you see, the fan translation uses the victims' real names while the official gave them fake ones. In the original Japanese, also the fake ones are what are used.)

When it comes to the later murders, Yuumori's story deviates from the historical events, since here, the last three victims of the canonical five was just a stage-play by William who tried to catch the killer(s) with setting up a fake Jack the Ripper. In reality, two of the victims, Elizabeth Stride and Catherine Eddowes were found on the same morning of 30th September - the Morigang placing two of the dead bodies at the same place so they get discovered at the same time must be a reference to that. The last victim, Mary Jane Kelly was discovered in the room where she lived on 9th November - her murder was the most gruesome out of the five, what I think Yuumori also referenced with Jack's show who pretended to kill a woman brutally on the roof.

Several letters signed as Jack the Ripper were sent to the newspapers. The media, especially the Central News Agency where some of the letters arrived, also overexaggerated about the details when they wrote about the murders, spreading a lot of misinformation just to sell more papers. In Yuumori, the group of people responsible for the murders who committed them to cause fear in the public and make a revolution by the Whitechapel Vigilance Committee and the police forces collide, hired Milverton to create the Jack the Ripper agenda with the help of his media power and he also manipulated the public opinion. The quotes shown from the letter sent to the Central News in the Moriarty the Patriot manga are from the first letter (called as Dear Boss letter) signed as Jack the Ripper what was also sent to Central News in reality - now researchers say it was written by a journalist to sell the papers better. The real letter was longer and the writer threatened to send the lady's ears to the police instead of her organs (however, with one of his later letters, Jack truly sent one of his victims kidney to the police), otherwise they are the same.

The Scotland Yard, just like in Yuumori wasn't really on the top when it came to solve the murders what resulted in riots and conflicts with the Whitechapel Vigilance Committee in reality too. And just like Chief Inspector Arterton was removed from his position in Scotland Yard - tho, for a slightly different reason - for not solving the Jack the Ripper case one of the police chiefs of London back then was also fired. In Moriarty the Patriot, a doctor was wrongly arrested and sent to prison in order to silence the raging public and in real life, lot of doctors were suspected to commit the murders.

In Yuumori, the identity of Jack the Ripper was solved by both Sherlock Holmes and the Morigang - who killed them - but it stayed unsolved for the public. In reality, the identity of Jack the Ripper either remained unsolved or not - few years ago, there was a DNA test what was said to determine the killer's identity, but lot of researchers believe that the test was incorrect and don't accept the answer.

I adore this arc for how well the series merged reality with fiction and it was especially exciting to read knowing the details of the real Jack the Ripper case.

#moriarty the patriot#yuukoku no moriarty#analysis#jack the ripper#i really hope i got every details right correct me if i was wrong

26 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Five: The Untold Lives of the Women Killed by Jack the Ripper

"The Five" by Hallie Rubenhold offers a fresh perspective on the victims of Jack the Ripper, focusing on their lives rather than their deaths. Rubenhold's meticulous research brings these women to life, challenging misconceptions and shedding light on the socio-economic struggles of Victorian London. Unlike typical true crime narratives, this book emphasizes the humanity of its subjects. It's a must-read for history enthusiasts of all levels.

The Five: The Untold Lives of the Women Killed by Jack the Ripper takes a refreshing approach by focusing on the lives of the women believed to be victims of the notorious killer rather than simply on their deaths. Unlike typical ripperology literature, this book barely mentions Jack the Ripper himself. Instead, it successfully brings the so-called canonical five victims to life, shedding light on who they were beyond their tragic ends. It offers a new perspective that challenges preconceived notions about these women and their places in history.

Hallie Rubenhold, author of The Covent Garden Ladies (2012) and The Harlot's Handbook (2007), showcases her mastery in The Five. She diverges from traditional Jack the Ripper narratives and focuses instead on the lives of the overlooked women. Through meticulous research, Rubenhold breathes life into their stories, exploring their relationships, livelihoods, and tragedies. This book isn't just for ripperologists; it appeals to anyone interested in British history. Offering a captivating glimpse into Victorian London's socio-economic landscape, it is a must-read for history enthusiasts and the curious alike.

Rubenhold's dedication to the five victims of Jack the Ripper is fitting, as she brings their stories to life with respect and dignity. Mary Ann Nichols, facing marital struggles, finds herself among the many homeless in Trafalgar Square. Elizabeth Stride, a Swedish immigrant, escapes a troubled past only to end up on the streets of London. Catherine Eddowes undergoes an abusive relationship. Mary Jane Kelly, once employed in a Paris brothel, seeks refuge in London. Rubenhold's portrayal of these women goes beyond their tragic ends, shedding light on the challenges they faced in life.

The Five challenges common misconceptions about the victims of Jack the Ripper, revealing a stark contrast to the sensationalized narratives often depicted in popular culture. Contrary to popular belief, only two of the five women—Elizabeth Stride and Mary Jane Kelly—were confirmed sex workers. Moreover, the ages of these women varied significantly: Mary Ann Nichols was 43, Annie Chapman 47, Elizabeth Stride between 44 and 45, Catherine Eddowes 46, and the youngest, Mary Jane Kelly, 25. Rubenhold's narrative offers a profound reexamination of these women's lives, moving beyond their tragic demise to illuminate the complexities of their individual stories. Placing each woman within the socio-economic backdrop of Victorian London, The Five provides a compelling exploration of the era's pervasive poverty and the harsh realities of daily life. Delving into the intricacies of workhouses, the narrative offers insights into the grim existence endured by those who found themselves within their confines. Additionally, it vividly depicts contrasting experiences, from the newly established Peabody Estate to the squalid brothels of the East End. Moreover, the book delves into the widespread perils of addiction, a prevalent issue among the urban poor, and the profound challenges of homelessness and familial disconnection. Through poignant storytelling, readers are transported into the harsh and unforgiving world faced by these five women.

This book is a remarkable literary work that transcends the confines of true crime literature, appealing to history enthusiasts of all levels of familiarity with the Whitechapel murders. Suitable for the teenage audience and beyond, this book offers a captivating journey into the hardships of Victorian London, making it a must-read for anyone interested in this era. What sets this book apart is its unparalleled depth of research and unique narrative approach. It stands as a singular masterpiece, offering a profound exploration of societal struggles and individual resilience. With no rivals in its genre, this book is an indispensable addition to any reader's collection. In its pages, this book unveils the forgotten snapshots of lives, preventing historical figures from being relegated to mere footnotes. Through poignant storytelling, it celebrates the endurance and resilience of its subjects, leaving an indelible impression on its readers.

Continue reading...

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

#catherine eddowes#kate eddowes#jack the ripper#victorian#victorian history#whitechapel murders#ripper memes#ripperology#circa 1888#true crime meme#true crime#feminism#ripper victim

0 notes

Text

This vaguely reminds me of when a friend very seriously told me (this was like a decade ago) that it'd just been PROVEN that Jack the Ripper didn't really exist! It was made up by the newspapers! She had READ about it on the news!

Like, I'm sorry, but DO YOU THINK THAT JACK THE RIPPER'S NAME WAS ACTUALLY "JACK D. RIPPER?" SHALL I TELL MARY ANN NICHOLS, ANNIE CHAPMAN, ELIZABETH STRIDE, CATHERINE EDDOWES, AND MARY JANE KELLY?

#the press stoked public interest in the case#and there are cases to be made for some of the Canonical Five not being the work of the same killer#(especially MJK)#but like...these women were killed by SOMEONE#and there's a case to be made for the study of the Ripper as a cultural phenomenon as much as the Whitechapel Murders are a historical even

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Funny what you hear...

A couple of days ago I found a TV series on YouTube that I haven't seen since 1973: "Jack The Ripper - Barlow & Watt Investigate".

It's an intriguing show, using two of the currently most popular TV policemen: they'd appeared in about three linked-but-separate crossover series, "Z Cars", "Softly Softly" and "Softly Softly Task Force".

However in this instance the crimes they're investigating, and the theories they're examining, are the notorious non-fictional Whitechapel murders.

*****

After about 50 years, watching this Is like seeing it for the very first time, and the very first episode contained the following exchange, which made me laugh a bit.

("Jack" is slang for a policeman, like "Bobby", "Peeler" or "cop", though I think Jack is more regionally North of England, where the Barlow and Watt characters originate.)

Barlow: "They had eight inspectors on the case." Watt: "And two Lancashire Jacks are worth how many from the south?" Barlow: "Well, at least we are Jacks. Starting with the evidence, and testing some theories. Not starting with the theory and selecting the evidence…"

*****

Why did I laugh?

It's because Barlow's final observation sums up Patricia Cornwell's infamous approach to her "Portrait of a Killer: Jack the Ripper: Case Closed".

Like any detective-story writer, she started with her chosen perpetrator (artist Walter Sickert) then arranged the rest of the book to "prove" it was 'im wot dunnit.

It's a book crammed full of circumstantial evidence and leap-of-logic speculations such as "...while there is no evidence Sickert was in London on that date, there is no evidence that he wasn't".

Well, duh.

Cornwell goes after her target with such obsession that one reviewer - a lawyer - pointed out that if Sickert had been still alive, the book would have been Exhibit A in a case of malicious libel. (Another comment, however, suggested he would have revelled in such notoriety...)

*****

As for closing the Ripper case or providing solid proof of who he / she / they was or were, it won't happen; the speculation industry is worth too much money and new books, new names and new theories - or old stuff recycled - keep coming out, with the most recent in July of this year (2023).

The only names that really matter are Mary Ann "Polly" Nichols, Anne "Annie" Chapman, Elizabeth "Long Liz" Stride, Catherine "Kate" Eddowes and Mary Jane Kelly.

They were people, not just names to tick off a check-list.

47 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Catherine “Kate” Eddowes

[Previous post]

Last days & murder

Catherine was five feet tall, with dark auburn hair, hazel eyes. Friends described her as “intelligent and scholarly, but possessed of a fierce temper” and “a very jolly woman, always singing.”

On Saturday September 29th 1888, at 8:00am, Catherine met her common-law husband John Kelly at Cooney’s lodging house where he spent the night, saying there had been some trouble at the Mile End Casual Ward where she spent the night and was turned out early. Between 10:00 and 11:00am, Frederick Wilkinson, deputy at Cooney’s, saw Catherine and John eating breakfast in the kitchen of Cooney’s. Wilkinson noted that Catherine had on an apron. It was agreed that Catherine would pawn a pair of Kelly’s boots at a broker, Smith or Jones, in Church Street. Catherine got 2/6d (12 1/2p), and the ticket was in the name of Jane Kelly. With the money, they bought tea, coffee, sugar, and food. In the early afternoon she told him she would go to Bermondsey (London Borough of Southwark) to try to get some money from her daughter Annie, whom she believed was living there. She said she would have returned by 4:00pm and she and John separated in good terms. With money from pawning his boots, a bare-footed Kelly took a bed at the lodging-house just after 8:00 p.m., and according to the deputy keeper remained there all night.

At 8.30 p.m. Catherine Eddowes was found lying drunk in the road on Aldgate High Street by PC Louis Robinson. She was taken into custody and then to Bishopsgate police station, where she was detained, giving the name “Nothing”, until she was sober enough to leave at 1 a.m. on the morning of 30 September. On her release, she gave her name and address as “Mary Ann Kelly of 6 Fashion Street”. When leaving the station, instead of turning right to take the shortest route to her home in Flower and Dean Street, she turned left towards Aldgate. Around the same time, Louis Diemschutz found Elizabeth Stride’s body in gateway of Dutfield’s Yard.

Catherine Eddowes was last seen alive at 1.35 a.m. by three witnesses, Joseph Lawende, Joseph Hyam Levy and Harry Harris, who had just left a club on Duke Street. She was standing talking with a man at the entrance to Church Passage, which led south-west from Duke Street to Mitre Square along the south wall of the Great Synagogue of London. Only Lawende could furnish a description of the man, whom he described as a fair-moustached man wearing a navy jacket, peaked cloth cap, and red scarf. Chief Inspector Donald Swanson intimated in his report that Lawende’s identification of the woman as Eddowes was doubtful. He wrote that Lawende had said that some clothing of the deceased’s that he was shown resembled that of the woman he saw—“which was black … that was the extent of his identity [sic]”. A patrolling policeman, PC James Harvey, walked down Church Passage from Duke Street very shortly afterwards but his beat took him back down Church Passage to Duke Street, without entering the square.

Discovery

Catherine was murdered and mutilated in the square between 1:35 and 1:44 a.m. At 1:45 a.m., a mutilated body of then an unidentified woman was found in the south-west corner of Mitre Square by the square’s beat policeman PC Edward Watkins, who said that he entered the square at 1:44 a.m, having previously been there at 1:30 a.m. He called for assistance at the Kearly and Tonge’s tea warehouse in the square, where night watchman George James Morris, who was an ex-policeman, had noticed nothing unusual. Neither had another watchman George Clapp at 5 Mitre Square or an off-duty policeman Richard Pearse at 3 Mitre Square. ”For God’s sake, mate, come to assist me,“ said PC Watkins. ”What’s the matter?“ asked Morris. ”Oh dear, there’s another woman cut to pieces.“ replied PC Watkins. Morris returned with PC Watkins to view the body. At the same time, Inspector Edmund Reid arrived at Dutfield’s Yard. Superintendent Thomas Arnold arrived shortly after. Around 3 minutes later, at 1:47am, PC Watkins stayed with the body while Morris blew his whistle, running down Mitre St and into Aldgate. One minute later, PC Harvey heard whistle, saw Morris running, and went over to him. Morris Told PC Harvey about the body. Morris saw Police Constable Holland and called him over. One minute later, PC Harvey, PC Holland, and Morris went to Mitre Square. After viewing the body, PC Holland went to fetch Doctor George William Sequeira from his surgery at 34 Jewry Street. At 1:55am Inspector Edward Collard notified at Bishopsgate Police Station about the body and sent a PC to notify Doctor Frederick Gordon Brown, City Police Surgeon, 17 Finsbury Circus. Dr Sequeira was notified about the body. At 1:58am Detective Constable Daniel Halse, Detective Constable Edward Marriott, and Detective Sergeant Robert Outram, at bottom of Houndsditch near St Boloph’s Church, responded to Morris’s whistle and went to Mitre Square.

At 2:00am PC Holland returned with Dr Sequeira, who pronounced Catherine dead. DC Halse, DC Marriott, and DS Outram arrived at scene. Three minutes later, Insp. Collard arrived and immediately organized a search of the district. At the same time, Dr Sequeira was informed of Dr Brown’s impending arrival and waited before conducting the exam further. At 2:05am, DC Halse went into Middlesex Street and then on into Wentworth Street. Police surgeon Dr. Brown, who arrived at 2:18 a.m., said of the scene: “The body was on its back, the head turned to left shoulder. The arms by the side of the body as if they had fallen there. Both palms upwards, the fingers slightly bent. A thimble was lying off the finger on the right side. The clothes drawn up above the abdomen. The thighs were naked. Left leg extended in a line with the body. The abdomen was exposed. Right leg bent at the thigh and knee. The bonnet was at the back of the head—great disfigurement of the face. The throat cut. Across below the throat was a neckerchief. … The intestines were drawn out to a large extent and placed over the right shoulder…. The lobe and auricle of the right ear were cut obliquely through… Body was quite warm. No death stiffening had taken place. She must have been dead most likely within the half hour. We looked for superficial bruises and saw none… Several buttons were found in the clotted blood after the body was removed. There was no blood on the front of the clothes…”

Investigation

At 2:20am, Detective Superintendent Alfred Lawrence Foster and Superintendent James McWilliam arrived at the scene. DC Halse was in Goulston St returning to Mitre Square, and PC Alfred Long was on patrol in Goulston Street - saw nothing suspicious there. It was also at this time that PC Pearse first heard about the murder. At 2:35am DC Halse back in Mitre Square as a part of his beating. The body was placed into ambulance and taken to Golden Lane Mortuary. Sergeant Jones found three buttons, a thimble, and a mustard tin containing 2 pawn tickets issued to Emily Birrell and Anne Kelly beside the body. These eventually led to her identification by John Kelly as his common-law wife, after he read about the tickets in the newspapers. His identification was confirmed by Catherine Eddowes’ sister, Eliza Gold. No money was found on her. Sergeant Phelps, Inspector Izzard, and Sergeant Dudman went at the scene to preserve the public order. DC Halse and Insp Collard went to mortuary, where the body was stripped and a piece of ear dropped from the clothing. Inspector Collard itemized Catherine’s possessions and DC Halse noticed a piece of her apron was missing.

Dr Brown, Dr Sequeira and Doctor William Sedgwick Saunders, Medical Officer of Health and Public Analyst, City of London, conducted a post-mortem that afternoon attended by Dr Phillips. Dr Brown noted: “After washing the left hand carefully, a bruise the size of a sixpence, recent and red, was discovered on the back … between the thumb and first finger… The hands and arms were bronzed… The cause of death was haemorrhage from the left common carotid artery. The death was immediate and the mutilations were inflicted after death … There would not be much blood on the murderer. The cut was made by someone on the right side of the body, kneeling below the middle of the body. … the left kidney carefully taken out and removed. … I believe the perpetrator of the act must have had considerable knowledge of the position of the organs in the abdominal cavity and the way of removing them. The parts removed would be of no use for any professional purpose. It required a great deal of knowledge to have removed the kidney and to know where it was placed. Such a knowledge might be possessed by one in the habit of cutting up animals. I think the perpetrator of this act had sufficient time … It would take at least five minutes. … I believe it was the act of one person.”

Police physician Thomas Bond, disagreed with Brown’s assessment of the killer’s skill level. Bond’s report to police stated: ”In each case the mutilation was inflicted by a person who had no scientific nor anatomical knowledge. In my opinion he does not even possess the technical knowledge of a butcher or horse slaughterer or any person accustomed to cut up dead animals.“ Local surgeon Dr Sequeira, who was the first doctor at the scene, and City medical officer Saunders, who was also present at the autopsy, also thought that the killer lacked anatomical skill and did not seek particular organs. In addition to the abdominal wounds, the murderer had cut Eddowes’ face: across the bridge of the nose, on both cheeks, and through the eyelids of both eyes. The tip of her nose and part of one ear had been cut off.

Due to the location of Mitre Square, the City of London Police under Detective Inspector James McWilliam joined the murder enquiry alongside the Metropolitan Police who had been engaged in the previous murders. Though the murder occurred within the City of London, it was close to the boundary of Whitechapel where the previous Whitechapel murders had occurred. The mutilation of Eddowes’s body and the abstraction of her left kidney and part of her womb by her murderer bore the signature of Jack the Ripper and was very similar in nature to that of earlier victim Annie Chapman.

Goulston Street Graffiti

At about 3 a.m. on the same day as Eddowes was murdered, PC Long found a blood-stained fragment of Catherine’s apron lying in the passage of the doorway leading to Flats 108 and 119, Model Dwellings, Goulston Street, Whitechapel. Above it on the wall was a graffito in chalk. There are at least 4 different versions of what was written in the graffiti:

PC Long told at an inquest that it read ”The Juwes are the men that Will not be Blamed for nothing“. Superintendent Arnold wrote a report which agrees with his account.

DC Halse arrived short time later, and took down a different version: “The Juws are not the men who will be blamed for nothing”.

City Surveyor Frederick Foster recorded a third version: “The Juws are not the men To be blamed for nothing”.

A summary report on the writing by Chief Inspector Swanson rendered it as “The Jewes are not the men to be blamed for nothing”. However, it is uncertain if Swanson ever saw the writing.

A copy according with Long’s version of the message was attached to a report from Metropolitan Police Commissioner Sir Charles Warren to the Home Office. PC Long searched staircases and surrounding area. The writing may or may not have been related to the murder, but either way, and despite the protests of PC Halse, it was washed away before dawn on the orders of Metropolitan Police Commissioner Warren, who feared that it would spark anti-Jewish riots. Mitre Square had three connecting streets: Church Passage to the north-east, Mitre Street to the south-west, and St James’s Place to the north-west. As PC Harvey saw no-one from Church Passage, and PC Watkins saw no-one from Mitre Street, the murderer must have left the square northwards through St James’s Place towards Goulston Street. Goulston Street was within a quarter of an hour’s walk from Mitre Square.

To this day, there is no consensus on whether or not the graffito is relevant to the murders. Some modern researchers believe that the apron fragment’s proximity to the graffito was coincidental and it was randomly discarded rather than being placed near it. If, as some writers contend, the apron fragment was cut away by the murderer(s) to use to wipe his hands, he could have discarded it near the body immediately after it had served that purpose, or he could have wiped his hands on it without needing to remove it. Author and former homicide detective Trevor Marriott raised another possibility: the piece of apron may not necessarily have been dropped by the murderer on his way back to the East End from Mitre Square. The victim herself might have used it as a sanitary towel, and dropped it on her way from the East End to Mitre Square.

On 30th September, John Kelly read in paper about victim having pawn ticket with Birrell’s name on it. He presented himself to the police and identified the body. Until then, he had no idea that Catherine was the victim.

Inquest

The Eddowes inquest was opened on 4 October by Samuel F. Langham, coroner for the City of London. A house-to-house search was conducted but nothing suspicious was discovered. Brown stated his belief that Eddowes was killed by a slash to the throat as she lay on the ground, and then mutilated.

October 11th, 1888 was the last day of her inquest. Verdict: “wiliful murder by person or persons unknown.”

Funeral

Catherine Eddowes was buried on Monday, 8 October 1888 in an elm coffin in the City of London Cemetery, in an unmarked (public) grave 49336, square 318. John Kelly and one of Catherine Eddowes’s sister attended.

After Catherine’s burial, her former husband Thomas Conway was located. The October 16th, 1888 issue of Echo, said: “Conway was at once taken to see Mrs. Annie Phillips, Eddowes’s daughter, who recognised him as her father. … He knew that [Catherine] had since been living with Kelly, and had once or twice seen her in the streets but has, as far as possible, kept out of her way, as he did not wish to have any further communication with her. Conway had followed the occupation of a hawker. The police describe him as evidently of very exemplary character. He alluded to his wife’s misconduct before their separation with evident pain”.

Today, square 318 has been re-used for part of the Memorial Gardens for cremated remains. Eddowes lies beside the Garden Way in front of Memorial Bed 1849.

In late 1996, the cemetery authorities decided to mark her grave with a plaque. The plaques used to have “victim of ‘Jack the Ripper” on them, but since 2003 have been replaced with ‘Heritage Trail’ markings instead. The grave can be found either side of the path in ‘Gardens Way’, to the east of the cemetery.

Aftermath

The Royal London Hospital on Whitechapel Road preserves some crime scene drawings and plans of the Mitre Square murder by the City Surveyor Frederick William Foster; they were first brought to public attention in 1966 by Francis Camps, Professor of Forensic Medicine at London University. Based on his analysis of the surviving documents, Camps concluded that “the cuts shown on the body could not have been done by an expert.”

In 2014, mitochondrial DNA that matched that of one of Eddowes’ descendants was extracted from a shawl said to have come from the scene of her murder. The DNA match was based on one of seven small segments taken from the hypervariable regions. The segment contained a sequence variation described as 314.1C, and claimed to be uncommon, with a frequency of only 1 in 290,000 worldwide. However, Professor Sir Alec Jeffreys and others pointed out this was in fact an error in nomenclature for the common sequence variation 315.1C, which is present in more than 99% of the sequences in the EMPOP database. Other DNA on the shawl matched DNA from a relation of Aaron Kosminski, one of the suspects. This match was also based on a segment of mitochondrial DNA, but no information was given that would enable the commonness of the sequence to be estimated. The owner of the shawl, British author Russell Edwards, claimed the matches proved Kosminski was Jack the Ripper. Others disagree. Donald Rumbelow criticized the claim, saying that no shawl is listed among Eddowes’ effects by the police, and mitochondrial DNA expert Peter Gill said the shawl “is of dubious origin and has been handled by several people who could have shared that mitochondrial DNA profile.” Two of Eddowes’ descendants are known to have been in the same room as the shawl for 3 days in 2007, and, in the words of one critic, “The shawl has been openly handled by loads of people and been touched, breathed on, spat upon.”

On July 2, 2015 Russell Edwards unveiled a blue plaque to Catherine Eddowes at Wolverhampton Civic & Historical Society. The plaque features an image of Catherine Eddowes and is inscribed, “Catherine Eddowes. Born nearby, at 20 Merridale Street, Graisley Green on 14-4-1842 and murdered on 30-9-1888 in Whitechapel, London. An innocent victim of ‘Jack The Ripper’.”

Photos from: Escrito en Sangre blogspot & Pinterest.

***

To know more:

Wikipedia

Casebook website - Wiki Casebook - Casebook Message boards - Casebook Timeline - Casebook Last Movements - Casebook Forums

Dissertation: Catherine Eddowes and Gallows Literature in the Black Country

Dissertation: Catherine Eddowes: Wolverhampton and Birmingham

Catherine Eddowes wordpress

JTR Forums

Find a Grave

Jack The Ripper Experience

Jack The Ripper.org - Jack The Ripper.org Catherine-s last night

Whitechapel Jack

Ripper Vision

Jack The Ripper Tour Mitre Square - Jack the Ripper Tour Double Event

Jack Ripper

Jack The Ripper Time

Jack The Ripper Map

BEGG, Paul (2003): Jack the Ripper: The Definitive History.

BEGG, Paul (2013): Jack The Ripper. The Facts.

COOK, Andrew (2009): Jack the Ripper.

EDDLESTON, John J. (2001): Jack the Ripper: An Encyclopedia.

EDWARDS, Russell (2014): Naming Jack the Ripper.

EVANS, Stewart P. & RUMBELOW, Donald (2006): Jack the Ripper: Scotland Yard Investigates.

EVANS, Stewart P. & SKINNER, Keith (2000): The Ultimate Jack the Ripper Sourcebook: An Illustrated Encyclopedia.

EVANS, Stewart P. & SKINNER, Keith (2001): Jack the Ripper: Letters from Hell.

FIDO, Martin (1987): The Crimes, Death and Detection of Jack the Ripper.

FROST, Rebecca (2018): The Ripper’s Victims in Print. The Rethoric Portrayals Since 1929.

HUME, Robert (2019): The hidden lives of Jack the Ripper’s victims.

KENDELL, Colin (2010): Jack the Ripper - The Theories and The Facts.

MARRIOT, Trevor (2005): Jack the Ripper: The 21st Century Investigation.

PRIESTLEY, Mick P. (2018): One Autumn in Whitechapel.

RANDALL, Anthony J. (2013): Jack the Ripper. Blood lines.

RUBENHOLD, Hallie (2019): The Five: The Untold Lives of the Women killed by Jack the Ripper / The Five: The Lives of Jack the Ripper’s Women.

RUMBELOW, Donald (2004): The Complete Jack the Ripper: Fully Revised and Updated.

SHELDEN, Neal E. (2013): Mary Jane Kelly and the Victims of Jack the Ripper: The 125th Anniversary.

SHELDEN STUBBINGS, Neal (2007): The Victims of Jack the Ripper.

SUDGEN, Philip (2002): The Complete History of Jack the Ripper.

TROW, M. J. (2009): Jack The Ripper: Quest for a Killer.

WHITE, Jerry (2007): London in the Nineteenth Century.

WHITEHEAD, Mark; RIVETT, Miriam (2006): Jack the Ripper.

WILSON, Colin; ODELL, Robin (1987): Jack the Ripper: Summing Up and Verdict.

WOOD, Simon Daryl (2015): Deconstructing Jack: The Secret History of the Whitechapel Murders.

WOODS, Paul; & BADDELEY, Gavin (2009): Saucy Jack: The Elusive Ripper.

#Kate Eddowes#Catherine Eddowes#victim#victims#1888#1880s#on this day#otd#gone but not forgotten#gone but never forgotten#rest in peace#violence against women#victorian women#victorian clothes#victorian clothing#women's history#19th century

17 notes

·

View notes