#bretagne legends

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Anyone here for Celtic Jayvik?

(bretagne représente)

#my art#arcane#digital art#jayvik#viktor#viktor arcane#jayce talis#jayce arcane#lol#league of legends#celt#celtic#bretagne#brittany

512 notes

·

View notes

Text

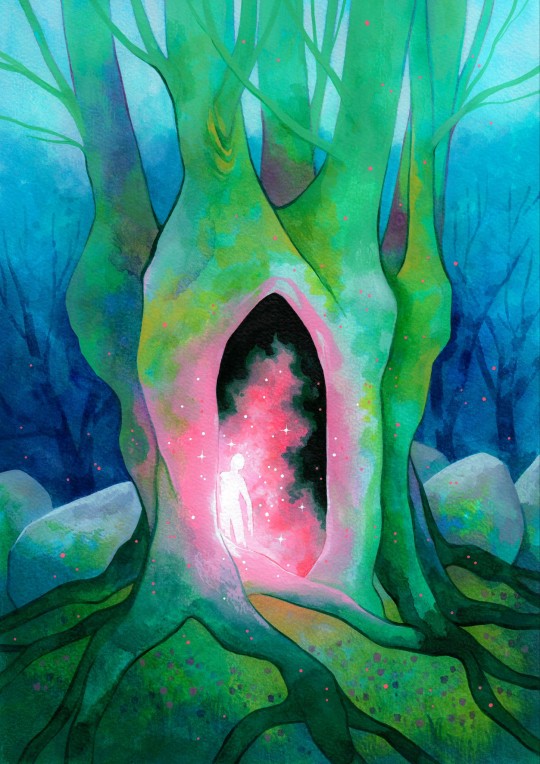

Korrigan.

#art#my art#artwork#my artwork#traditional art#artists on tumblr#illustration#paint#painting#draw#drawing#watercolor#watercolour#gouache#markers#fantasy ambient#fantasy#dark fantasy#folklore#legend#bretagne#december#colorful

129 notes

·

View notes

Text

Légendes rustiques by George Sand, completed English translation

Original French at Project Gutenberg

Les Légendes rustiques is a collection of twelve creepy French folk legends gathered up and written down by George Sand and illustrated by her son, Maurice Sand, published in 1858. These stories were collected in the Berry region, but there are connections made to legends from Brittany and Normandy as well.

I came across a mention of the Rustic Legends a few years ago and realized there was no official English translation available, despite that George Sand is a very famous author. It turns out, Sand was such a prolific writer that much of her work has never been translated into English. I ordered a "translation" from Amazon and was disappointed to find that someone had just run the text through translation software without any editing or providing any cultural context. It was unreadable and I threw it in the trash.

I asked some fandom friends if they would be interested in trying to translate all twelve legends into English on our own. It has been a few years and each story has had several revisions and rounds of editing. This was a challenging translation project - there are many words in archaic French or not in French at all. Thanks to everyone who helped - I am really proud of the results here.

The purpose of this project is simply to make these twelve legends accesible to an English-reading audience. They have been available in the original French at Project Gutenberg for a long time. Use this post as a table of contents - each line will take you to a new story published on Tumblr. Sometimes they are creepy, they are often funny, and Sand's rambling style is cozy, making you feel like she is sitting right across a candle from you, telling you a story she once heard from someone else, a long time ago. Enjoy!

Introduction

1. Les Pierres-Sottes

2. Les Demoiselles

3. Les Laveuses de nuit

4. La Grand’Bête

5. Les Trois Hommes de Pierre

6. Le Follet d’Ep-Nell

7. Le Casseu’ de Bois

8. Le Meneu’ de Loups

9. Le Lupeux

10. Le Moine des Étangs-Brisses

11. Les Flambettes

12. Lubins et Lupins

#légendes rustiques#george sand#maurice sand#french literature#in translation#folklore#rustic legends#french folklore#translation project#bretagne#brittany#normandie#normandy#berry

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

#evariste-vital luminais#la fuite du roi gradlon#1884#art#painting#painter#bretagne#breton#breizh#brittany#celtic#legend#legandary#ys#finistère#douarnenez#france#french#xix century#folklore#history#culture#europe#european#ocean

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Arthurian myth: Morgan the Fey (1)

Loosely translated from the French article "Morgane", written by Philippe Walter, for the Dictionary of Feminine Myths (Le Dictionnaire des Mythes Féminins)

MORGANE

Morgane means in Celtic language “born from the sea” (mori-genos). This character is as such, by her origins, part of the numerous sea-creatures of mythologies. A Britton word of the 9th century, “mormorain”, means “maiden of the sea/ sea-virgin”, et in old texts it is equated with the Latin “siren”. A passage of the life of saint Tugdual of Tréguiers (written in 1060) tells of ow a young man of great beauty named Guengal was taken away under the sea by “women of the sea”. The Celtic beliefs knew many various water-fairies with often deadly embraces – and Morgane was one among the many sirens, mermaids, mary morgand and “morverc’h” (sea girls/daughters of the sea).

Morgane, the fairy of Arthurian tales, is the descendant of the mythical figures of the Mother-Goddesses who, for the Celts, embodied on one side sovereignty, royalty and war, and on the other fecundity and maternity. In the Middle-Ages, they were renamed “fairies” – but through this word it tried to translate a permanent power of metamorphosis and an unbreakable link to the Otherworld, as well as a dreaded ability to influence human fate. The French word “fée” comes from the neutral plural “fata”, itself from the Latin word “fatum”, meaning “fate”.

There is not a figure more ambivalent in Celtic mythology – and especially in the Arthurian legends – than Morgane. She constantly hesitates between the character of a good fairy who offers helpful gifts to those she protects ; and a terrible, bloodthirsty goddess out for revenge, only sowing death and destruction everywhere she goes. Christianity played a key role in the demonization of this figure embodying an inescapable fate, thus contradicting the Christian view of mankind’s free will.

I/ The sovereign goddess of war

It is in the ancient mythological Irish texts that the goddess later known as Morgane appears. The adventures of the warrior Cuchulainn (the “Irish Achilles”) with the war-goddess Morrigan are a major theme of the epic cycle of Ireland. The Morrigan (a name which probably means “great queen”) is also called “Bodb Catha” (the rook of battles). It is under the shape of a rook (among many other metamorphosis) that she appears to Cuchulainn to pronounce the magical words that will cause the hero’s death.

The Irish goddesses of war were in reality three sisters: Bodb, Macha and Morrigan, but it is very likely that these three names all designated the same divinity, a triple goddess rather than three distinct characters. This maleficent goddess was known to cause an epileptic fury among the warriors she wanted to cause the death of. The name of Bodb, which ended up meaning “rook”, originally had the sense of “fury” and “violence”, and it designated a goddess represented by a rook. The Irish texts explain that her sisters, Macha and Morrigan, were also known to cause the doom of entire armies by taking the shape of birds. Every great battle and every great massacre were preceded by their sinister cries, which usually announced the death of a prominent figure.

The Celtic goddesses of war have as such a function similar to the one of the Norse Walkyries, who flew over the battlefield in the shape of swans, or the Greek Keres. The deadly nature of these goddesses resides in the fact that they doom some warriors to madness with their terrifying screams. One of the effects of this goddess-caused madness was a “mad lunacy”, the “geltacht”, which affected as much the body as the mind. During a battle in 1722 it was said that the goddess appeared above king Ferhal in the shape of a sharp-beaked, red-mouth bird, and as she croaked nine men fell prey to madness. The poem of “Cath Finntragha” also tells of the defeat of a king suffering from this illness. The place of his curse later became a place of pilgrimage for all the lunatics in hope of healing.

The link between the war-goddess and the “lunacy-madness” are found back within folklore, in which fairies, in the shape of birds, regularly attack children and inflict them nervous illnesses. These fairies could also appear as “sickness-demons”. Their appearance was sometimes tied to key dates within the Celtic calendar, such as Halloween, which corresponded to the Irish and pre-Christian celebration of Samain. Folktales also keep this particularly by placing the ritualistic appearances of witches and of fate-fairies during the Twelve Days, between Christmas and the Epiphany – another period similar to the Celtic Halloween. Morgane seems to belong to this category of “seasonal visitors”.

II) The Queen of Avalon

In Arthurian literature, Morgane rules over the island of Avalon, a name which means the Island of Apples (the apple is called “aval” in Briton, “afal” in Welsh and “Apfel” in German). Just like the golden apples of the Garden of the Hesperids, in Celtic beliefs this fruit symbolizes immortality and belongs to the Otherworld, a land of eternal youth. It is also associated with revelations, magic and science – all the attributes that Morgane has. Her kingdom of Avalon is one of the possible localizations of the Celtic paradise – it is the place that the Irish called “sid”, the “sedos” (seat) of the gods, their dwelling, but at the same time a place of peace beyond the sea. Avalon is also called the Fortunate Isle (L’Île Fortunée) because of the miraculous prosperity of its soil where everything grows at an abnormal rate. As such, agriculture does not exist there since nature produces by itself everything, without the intervention of mankind.

It is within this island that the fairy leads those she protects, especially her half-brother Arthur after the twilight of the Arthurian world. Morgane acts as such as the mediator between the world of the living and the fabulous Celtic Otherworld. Like all the fairies, she never stops going back and forth between the two worlds. Morgane is the ideal ferrywoman. The same way the Morrigan fed on corpses or the Valkyries favored warriors dead in battle, Morgane also welcomes the soul of the dead that she keeps by her side for all of eternity. Some texts gave her a home called “Montgibel”, which is confused with the Italian Etna. The Otherworld over which she rules doesn’t seem, as such, to be fully maritime.

The ”Life of Merlin” of the Welsh clerk Geoffroy of Monmouth teaches us that Morgan has eight sisters: Moronoe, Mazoe, Gliten, Glitonea, Gliton, Thiten, Tytonoe, and Thiton. Nine sisters in total which can be divided in three groups of three, connected by one shared first letter (M, G, T). In Adam de la Halle’s “Jeu de la feuillée”, she appears with two female companions (Arsile and Maglore), forming a female trinity. As such, she rebuilds the primitive triad of the sovereign-goddesses, these mother-goddesses that the inscriptions of Antiquity called the “Matres” or “Matronae”. In this triad, Morgane is the most prominent member. She is the effective ruler of Avalon, since it was said that she taught the art of divination to her sisters, an art she herself learned from Merlin of which she was the pupil. She knows the secret of medicinal herbs, and the art of healing, she knows how to shape-shift and how to fly in the air. Her healing abilities give her in some Arthurian works a benevolent function, for example within the various romans of Chrétien de Troyes. She usually appears right on time to heal a wounded knight: she is the one that gave a balm to Yvain, the Knight of the Lion, to heal his madness. In these works, Morgane does not embody a force of destruction, but on the contrary she protects the happy endings and good fortunes of the Round Table. She is the providential fée that saves the souls born in high society and raised in the “courtois” worship of the lady. However, her powers of healing can reverse into a nefarious power when the fée has her ego wounded.

III/ The fatal temptress

In the prose Arthurian romans of the 13th century, Morgane can be summarized by one place. After being neglected by her lover Guyomar, she creates “le Val sans retour”, the Vale of No-Return, a place which will define her as a “femme fatale”. This place transports without the “littérature courtoise” the idea of the Celtic Otherworld. Also called “Le Val des faux amants” (The Vale of False Lovers), “le Val sans retour” is a cursed place where the fée traps all those that were unfaithful to her, by using various illusions and spells. As such, she manifests both her insatiable cruelty and her extreme jealousy. Lancelot will become the prime victim of Morgane because, due to his love for Queen Guinevere, he will refuse her seduction. The feelings of Morgane towards Lancelot rely on the ambivalence of love and hate: since she cannot obtain the love of the knight by natural means, she will use all of her enchantments and magical brews to submit Lancelot’s will. In vain. Lancelot will escape from the influence of this wicked witch. In “La Mort le roi Artu”, still for revenge, Morgan will participate in her own way to the decline to the Arthurian world: she will reveal to her brother, king Arthur, the adulterous love of Guinevre and Lancelot. She will bring to him the irrefutable proof of this affair by showing her what Lancelot painted when he had been imprisoned by her. The terrible war that marks the end of the Arthurian world will be concluded by the battle between Arthur and Mordred, the incestuous son of Arthur and Morgan. As such, Morgan appears as the instigator of the disaster that will ruin the Arthurian world. She manipulates the various actors of the tragedy and pushes them towards a deadly end. It should be noted that any sexual or romantic relationship between Arthur and Morgane are absent from the French romans – they are especially present within the British compilation of Malory, La Mort d’Arthur.

Behind the possessive woman described by the Arthurian texts, hides a more complex figure, a leftover of the ancient Celtic goddess of destinies. Cruel and manipulative, Morgan is fuses with the fear-inducing figure of the witch. Despite being an enemy of men, she keeps seeking their love. All of her personal tragedy comes from the fact that she fails to be loved. Always heart-sick, she takes revenge for her romantic failure with an incredible savagery. Her brutality manifest itself through the ugliness that some text will end up giving her – the ultimate rejection by this Christian world of this “devilish and lustful temptress”. “La Suite du Roman de Merlin” will try to give its own explanation for this transformation of Morgane, from good to wicked fairy: “She was a beautiful maiden until the time she learned charms and enchantments ; but because the devil took part in these charms and because she was tormented by both lust and the devil, she completely lost her beauty and became so ugly that no one accepted to ever call her beautiful, unless they had been bewitched”. In this new roman, she is responsible for a series of murders and suicides – and as the rival of Guinevere, she tries to cause King Arthur’s doom by favorizing her own lover, Accalon. Another fée, Viviane, will oppose herself to her schemes.

The demonization of the goddess is however not complete. Morgan appears in several “chansons de gestes” of the beginning of the 13th century, and even within the Orlando Furioso of the Arisote, in the sixth canto, in which she is the sister of the sorceress Alcina. She is presented as the disciple of Merlin. Seer and wizardess, she owns (within Avalon or the land of Faerie) a land of pleasure, a little paradise in which mankind can escape its condition. At the same time the Arthurian texts discredit her, she joins a strange historico-pagan syncretism, by being presented as the wife of Julius Caesar, and as the mother of Aubéron, the little king of Féerie.

After the Middle-Ages, the fée Morgane only mostly appears within the Breton folklore (the French-Britton folklore, of the French region of Bretagne). There, old mythical themes which inspired medieval literature are maintained alive, and keep existing well after the Middles-Ages. Morgane is given several lairs, on earth or under the sea. In the Côtes-d’Armor, there is a Terte de la fée Morgan, while a hill near Ploujean is called “Tertre Morgan”. There is an entire branch of popular literature in Bretagne (such as Charles Le Bras’ 1850 “Morgân”) where the fée represents the last survivor of a legendary land and the reminder of a forgotten past. She expresses the nostalgia of a lost dream, of a fallen Golden Age. True Romantic allegory of the lands and seas of Bretagne, she most notably embodies the feeling of a Bretagne land that was in search of its own soul.

However, it is her role of “cursed lover” that stays the most dominant within the Breton folklore. The vicomte de La Villemarqué, great collector of folktales and popular legends, noted in his “Barzaz Breiz” (1839) that the “morgan”, a type of water spirits, took at the bottom of the sea or of ponds, in palaces of gold and crystal, young people that played too close to their “haunted waters”. The goal of these fairies was to kidnap them to regenerate their cursed species. This ties the link between these “morganes” (also called “mary morgand”) and the Antique “fairy of fate”. Similar names, a same love of water, and the presence of the “land below the waves”, of a malevolent seduction – these are the permanent traits of Morgane, who keeps confusing and uniting the romantic instinct for love, and the desire for death. More modern adaptations of the legend (such as Marion Zimmer Bradley’s novels) weave an entire feminist fantasy around the figure of this fairy, supposed to embody the Celtic matriarchy.

#arthuriana#arthurian myth#arthurian legend#morgane#morgan#morgan le fey#fée#french folklore#folklore of bretagne#celtic mythology#irish mythology

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

ohhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhh it makes so much sense that “beleriand” started out as “broseliand” (brocéliande)

#cannot believe i didn't piece that together#the silmarillion#edit: especially since beleriand + the rest of middle-earth's western coastline is straight-up shaped like bretagne#(and if i said i first heard the name brocéliande not in its proper legends but in a les mis fic. well. what then.)#arthurian legend

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Flight of King Gradlon, oil on canvas made around 1884 by Evariste-Vital Luminais

King Gradlon and the Legend of Ys:

"King Gradlon (Gralon in Breton) ruled in Ys, a city built on land reclaimed from the sea, sometimes described as rich in commerce and the arts. He lived in a wealth palace of marble, cedar and gold. In some versions, Gradlon built the city upon the request of his daughter Dahut, who loved the sea. To protect Ys from inundation, a dike was built with a gate that was opened for ships during low tide. The one key that opened the gate was held by the king.

Some versions, especially early ones, blame Gradlon's sins for the destruction of the city. However, most tellings present Gradlon as a pious man, and his daughter Dahut as a sorceress or a wayward woman who steals the keys from Gradlon and opens the gates of the dikes, causing a flood which destroys the whole city. A Saint (either St. Gwénnolé or St. Corentin) wakes the sleeping Gradlon and urges him to flee. The king mounts his horse and takes his daughter with him, but the rising water is about to overtake them. Dahut either falls from the horse, or Gradlon obeys a command from St. Gwénnolé and throws Dahut off. As soon as Dahut falls into the sea, Gradlon safely escapes. He takes refuge in Quimper and reestablishes his rule there." - Gradlon wikipedia article

#Evariste-Vital Luminais#art#The Flight of King Gradlon#bretagne#legend of ys#breton#breton folklore#brittany mythos

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Korrigans

Note: I'm an English learner and I wrote this text to practise my written English. If you want to give me feedback about my English, please go ahead!

Korrigans are creatures from the folklore of Brittany (North-West of France) that look like little black and hideous people. They are described as hairy, thickset and they have frizzy hair. They keep with them a purse which is said to be full of gold. But if someone stole it, they would find inside only dirty horsehair and a pair of scissors. These pranksters like playing tricks on Christians who don’t respect their duty. They are sometimes accused of stealing animals or objects, or making a mess in houses.

See more :

They usually live in megalithic monuments, which are sometimes called “ville des korrigans,” “city of the korrigans”. They keep inside of these constructions their treasure, which they take out at night to spread it out on the ground. Sometimes they do it in the summer sunshine. Still at night, in some stories at full moon, they dance around blocks of stone, singing often the days of the week till Friday. If one tries to complete the song adding the two last days, the korrigans might dislike it and shower them with blows. If one runs into them, they could get swept up in the korrigans’ dance. They are forced to dance to the point of exhaustion.

Korrigans seem to be related to fairies. For instance, when a fairy steals a human baby, sometimes, it substitutes it with a korrigan.

In Chants populaires de la Bretagne, Théodore Hersart de La Villemarqué explains his theory about the origins of korrigans. The ancient bards venerated a goddess called Korid-Gwen. She was associated with another character who was similar to dwarves and who was called Gwion. He was nicknamed “le Nain” (the Dwarf) or “le Nain à la bourse” (the Dwarf with the purse), because he was sometimes represented with a purse in his hand. He was in charge of guarding a mystical vase containing the water of genius, divination and science. Three drops fell on his hand, and he took them to his mouth. Thus, he discovered the future and science. In addition to carrying a purse with them, Armorican dwarves are related with magic, occult, alchemy, metallurgy and divination, which reminds of the legend of Gwion. This link can also be found in a medicinal plant that dwarves are said to like. It is sometimes called the herb of kov, but the Welsh also call it the herb of Gwion, while the Gaulish used the word korig.

In an article from Bulletin de la Société polymathique du Morbihan, Alfred Fouquet tells a legend about a very poor farmer. One night, the farmer saw little black men around a tumulus. Some were dancing on it, others came in and out. The farmer let out a scream in surprise. The little men, who were korrigans, ran away when they heard him. A few days later, the man wanted to go back there at night. It took him the whole night to clear the entrance of the tumulus, but he eventually managed to go inside. He saw the goblins gathered around a pot. They noticed him and started to run all over the place. One of them even went to the neighbouring wood to hang itself, giving to the place the name of “bois du Pendu” (wood of the Hanged one). The man, who was, as we said, very poor, took their pot filled with their treasure, and brought it home. He became rich, and bought the farm where he worked. Years passed, and his children grew up used to a wealthy life. The farmer died, and shortly afterwards, his children reached the bottom of the pot. Finally, his grandson was buried in debt. He had to sell the farm. As he wasn’t able to pay the land rent anymore, he was evicted.

Emile Souvestre, in Foyer Breton, tells another story about these tiny beings. Lao was a Breton bagpipes player. One night, he went down the mountains with a group of people to play during the pardon of the Armor. They reached a crossroads. The women wanted to go down the path that leads to the ocean. But Lao wanted to take the one that goes through the heath. The women explained that there was a city of korrigans and only those who never committed any sin could go through there without trouble. He didn’t believe in these stories and said he would play for them since they liked dancing. He took the path to the heath and began playing. The women went down the way to the sea. He saw the menhir and the korrigans’ home. He heard a murmur which, little by little, became a rumble. Tussocks shook and became hideous dwarves. Surprised and intimidated, Lao stepped back against the menhir. The korrigans surrounded him and forced him to play. The musician was unable to stop, and he played and danced until dawn. Eventually, he collapsed from exhaustion.

Sources

Marie-Charlotte DELMAS. “Korrigan”. In: Dictionnaire de la France Merveilleuse. Paris, France: Omnibus, 2017, p. 418-420.

Alfred FOUQUET. “Un kilomètre en Crach”. Bulletin de la Société polymathique du Morbihan, 1863, p. 1-7.

URL (Gallica)

Théodore Hersart de La Villemarqué. Chants populaires de la Bretagne, First Volume, Fourth edition, p. 46-53. Paris : Leipzig, 1846.

Désiré Monnier, Aimé Vingtrinier. “Les Fées Chrétiennes”. In : Croyances et traditions populaires recueillies dans la Franche-Comté le Lyonnais la Bresse et le Bugey. Lyon : Henri Georg, 1874, p. 393-397.

Prisma Media. “Korrigan : qui est cette créature légendaire bretonne ?” Geo [online]. Gennevilliers. 05/11/2021. [Visited between 01/06/23 and 02/06/23]

URL

Louis Pierre François Adolphe Chesnel de la Charbouclais (marquis de). “Gauriks ou Gores”, p. 216, “Korandons”, p. 262, “Korigans ou Korigs”, p. 262, “Korils ou Kourils”, p. 264, “Kornikaneds”, p. 267, “Poulpicans, Poulpiquets, ou Korils”, p. 466, “Teus”, p. 594. In: Dictionnaire des superstitions, erreurs, préjugés et traditions populaires, vol. 20 of Troisième et dernière encyclopédie théologique. J.-P. Migne, 1856

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

La pierre tremblante de Huelgoat

Nouvel article publié sur https://www.2tout2rien.fr/la-pierre-tremblante-de-huelgoat/

La pierre tremblante de Huelgoat

#Bretagne#deplacement#equilibre#erosion#finistere#France#gargantua#Huelgoat#legende#menhir#mouvement#pierre#rocher#vidéo#imxok#nature#voyage

1 note

·

View note

Text

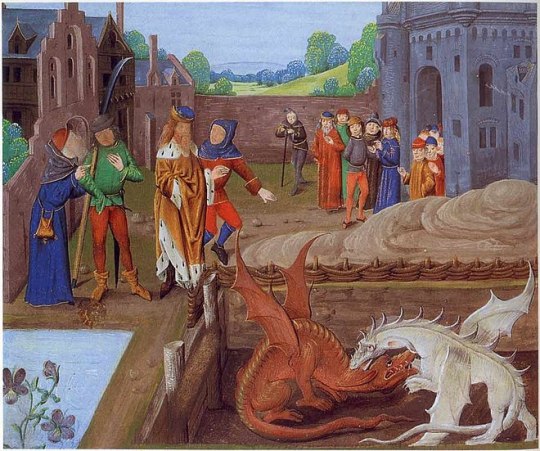

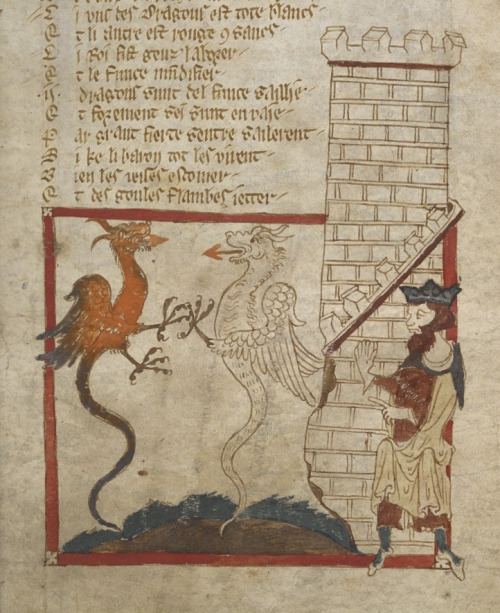

Black Butler & Celtic Legend Part 1 - The Omen of The Dragons

Alright y'all, back on my medieval French Celtic literature shit. Excuse my ADHD ass hopping from theory to theory. I'm excited and sad about this one as it's my prediction for Undertaker's final fight - and it's not looking so good 😞

In Part 2 of my French Crown Jewels Series I theorized that Undertaker is in possession of some of the gemstones he recovered from the Order of the Golden Fleece insignia for Louis XV. This contains, among other gems, the original diamond from which the Phantomhive family ring was made (referred to as The Hope Diamond in season 1 of the anime). I theorized that within the insignia, Undertaker is represented by le Côte-de-Bretagne, the spinel carved into a red dragon.

And I think Undertaker is also represented by the red dragon in the Arthurian tale of King Vontigern and his construction woes - The First Legend of Merlin.

In this legend a monarch is attempting to build a tower above a pool of water, and when the foundation fails each night, he's advised that in order to successfully build the tower he must sacrifice a half-human child. However upon digging into the foundation he finds two dragons fighting, one representing the native Britons, the other representing the invading Saxons...

LET'S TALK ABOUT DRAGONS BABY.

Usual disclaimer - I have not been able to find evidence of this legend being discussed before in relation to Black Butler. Please tell me if it has.

A Very Brief & Simplified History of Brittany

First off, I want to clarify a few things about Brittany, France, just in case anyone's confused. If you're not confused about the relationship between Britons and Bretons, feel free to skip this part!

Brittany (French: Bretagne) is a peninsula, historical country and cultural area in the north-west of modern France, covering the western part of what was known as Armorica in Roman Gaul.

In the 6th century, Celtic people (Britons) fleeing the Anglo-Saxon invasion immigrated from Great Britain to Brittany, which was then a part of Armorica (meaning land by the sea).

By the 11th century, Brittonic-speaking populations had split into distinct groups: the Welsh in Wales, the Cornish in Cornwall, the Bretons in Brittany, the Cumbrians of the Hen Ogledd ("Old North") in southern Scotland and northern England, and the remnants of the Pictish people in northern Scotland.

So by the 11 century, the Britonic people have separated into distinct cultural and geographical groups, and have developed their own distinct languages - but the Welsh, Cornish, and Breton people all descend from the same ethnic group, the people who had inhabited the British Isles since the iron age (800 BC) and spoke Brittonic. The Irish, Scottish, and the Manx (those who inhabit the Isle of Mann) descend from those who spoke Goidelic (Gaelic).

Brittany became an independent kingdom and then a duchy before being united with the Kingdom of France in 1532 as a province governed as a separate nation under the crown. Brittany is the traditional homeland of the Breton people and is one of the six Celtic nations, retaining a distinct cultural identity that reflects its history.

When Undertaker was alive in the 14th century, Brittany was ruled by the Dukes of Brittany. In 1532 they officially became a part of France, but they've always retained a unique identity and there is a strong separatist movement today to seek further independence from France. Brittany is sort of the 'Québec' to France's 'Canada'.

The most relevant information to know is that before the middle ages, the people who inhabited the regions now known as Wales and Brittany shared a heritage and a common tongue. The legend of King Arthur takes place in both England and Brittany (I believe the Isle of Avalon in the world of Black Butler will be off the coast of Brittany) and Arthur and his companions are important historical/mythological figures in both Welsh and Breton culture.

Historia Regum Britanniae

I am going to focus on analyzing the Omen of the Dragons as it appears in The History of the Kings of Britain or Historia regum Britanniae, a work of historical fiction that was written in the 12th century. It chronicles the lives of the Kings of Britons from the founding of the British nation up until the Anglo-Saxons assumed control of much of Britain around the 7th century. Historia regum Britanniae is one of, if not the central piece of The Matter of Britain, a body of medieval literature associated with Great Britain, Brittany, and their legendary kings and heroes, particularly King Arthur. The lais of Marie de France, one of which I detailed in my Rossignol theory post, are also part of The Matter of Britain.

The First Legend of Merlin as portrayed in Historia Regum Brittanie

The First Legend of Merlin revolves around the characters of the half-human boy Merlin/Ambrosius and the Monarch, King Vortigern.

It should be noted that this legend is sourced from an already existing story and that the figure of Merlin is imposed onto the real life 5th century historical figure Ambrosius Aurelianus. Ambrosius was a war leader of the Romano-British who won an important battle against the Anglo-Saxons.

King Vortigern himself was a native Briton, but he is portrayed to be a betrayer of his own people - or at the very least, an easily manipulated fool. He invited the Saxons to England - brilliant fucking idea, mate - and married a Saxon.

Vortigern was a 5th-century British ruler best known for inviting the Saxons to Britain to stop the incursions of the Picts and Scots and allowing them to take control of the land. He is regularly depicted as a villain or, at best, weak-willed and unable to control the Saxons once he arranged for, or encouraged, their arrival in Britain.

In the legend, King Vortigern has lost all his other fortified holds, so he asks his advisors/ 'magicians' for advice and they tell him to build another. Seems kind of obvious to me... Except all work that they do vanishes overnight.

At last he had recourse to magicians for their advice, and commanded them to tell him what course to take. They advised him to build a very strong tower for his own safety, since he had lost all his other fortified places. Accordingly he made a progress about the country, to find out a convenient situation, and came at last to Mount Erir, where he assembled workmen from several countries, and ordered them to build the tower. The builders, therefore, began to lay the foundation; but whatever they did one day the earth swallowed up the next, so as to leave no appearance of their work.

So Vortigern asks the magicians and they advise him to take the next logical course of action - child sacrifice, my liege, duh!

Vortigern being informed of this again consulted with his magicians concerning the cause of it, who told him that he must find out a youth that never had a father, and kill him, and then sprinkle the stones and cement with his blood; for by those means, they said, he would have a firm foundation. Hereupon messengers were despatched away over all the provinces, to inquire out such a man.

Now, at this my ears perked up like a fucking dog's. A youth that never had a father - that's a phrase that sounds like it could have been subjected to many a translation. After all, what does a child that never had a father mean? A child who was hatched from an egg? A kid whose dad went out to buy cigarettes and never came back? An orphan? A bastard? A child whose father was dead before they were even conceived?

Sure enough, when I scrounged around for another translation:

“The child must be borne of both woman and demon.”

And yet another interpretation merely states that the child cannot have a "mortal father".

His wizards claim that only by mixing in the blood of a child who has no mortal father will he make the foundations sound.

Ancient engineering is a trip, eh? I so love living in a time where we don't rely on mixing the blood of children into our concrete to prevent a sinking foundation.

Now, as to what Vortigern was attempting to build... Sometimes it's a "fortress", sometimes it's a "citadel", but most often the translation reads as a "tower". Another aspect of the legend remains consistent - the construction is always occurring either above or next to a body of water.

So a monarch is trying to build a structure (a tower over water), and is mysteriously unable to begin his project. His advisors tell him in order to proceed, he must sacrifice a child - one sired by a non-mortal upon a mortal woman.

Monarch/Warlord = King Vortigern = Queen Victoria

Structure over water = tower above pool = Tower Bridge over the Thames

Monarch's advisors = Vortigern's magicians = John Brown

Half-mortal child = Ambrose/Merlin = Vincent Phantomhive

Tower bridge under construction in 4x11

It's long been speculated that the events of December 14th, 1885 (namely, the murder of Vincent Phantomhive) are connected to the Tower Bridge, a project Prince Albert took a particular interest in. It began construction on April 22, 1886 (around four months after Vincent's murder) and is referenced several times in the manga...and in season 1 of the anime, the unfinished bridge is where the final confrontation between Sebastian and Ash/Angela takes place.

Sebastian & the angel Ash on the unfinished Tower Bridge in 1x24. Souls forming a seal above the bridge while the city of London burns in 1x24.

The bridge in the anime is built with/contains human sacrifices, and Sebastian states in all likelihood it was Ash/Angela (the advisor) who instructed Victoria (Vortigern) to build the bridge.

Ash states that "no demon must be allowed to enter through this gate" and that soon "all of eastern London will be safe from impurity". Eastern, specifically 👀 remember this for later...

Horrible CGI human sacrifices in the bridge's foundation in 1x24

Back to the legend - the kings advisors go searching and find such a child who has no father, a boy whose mother claims to have laid with none other than a being who had long haunted her before lying with her in the shape of a beautiful young man. The king consults his advisor, who tells him that Merlin's father was likely an incubus.

For, as Apuleius informs us in his book concerning the Demon of Socrates, between the moon and the earth inhabit those spirits, which we will call incubuses. These are of the nature partly of men, and partly of angels, and whenever they please assume human shapes, and lie with women. Perhaps one of them appeared to this woman, and begot that young man of her."

Further versions of the legend add that Merlin/Ambrose is actually created as the antichrist. However Merlin is never portrayed as a malevolent force; having been baptized by his mother, he is freed from the Devil's influence, and yet still has the kick-ass powers. You get the best of both worlds, I guess.

The Omen of The Dragons

Merlin speaks with the king and when he finds out his intent is to sacrifice him, he reasonably suggests to him and his followers that before you go around sacrificing children maybe you should take a look at what's underneath the tower! And for this, they name him a prophet. Turns out common sense is magical! So they dig up the ground, and they find a pond underneath the tower which has been the cause of the foundation sinking.

Then said he again to the king, "Command the pond to be drained, and at the bottom you will see two hollow stones, and in them two dragons asleep." The king made no scruple of believing him, since he had found true what he said of the pond, and therefore ordered it to be drained: which done, he found as Merlin had said; and now was possessed with the greatest admiration of him. Not were the rest that were present less amazed at his wisdom, thinking it to be no less than divine inspiration.

Lo and behold, when they look they find two dragons, just as Merlin had predicted. The translation here is a bit misleading - the true spirit of Vortigern's reaction seems to be more along the lines of fearful reverence - he and his men were intimidated by Merlin/Ambrose's abilities.

The dragons, one red and one white, wake and fight each other with fire over the lake as the king looks on.

As Vortigern, king of the Britons, was sitting upon the bank of the drained pond, the two dragons, one of which was white, the other red, came forth, and approaching one another, began a terrible fight, and cast forth fire with their breath. But the white dragon had the advantage, and made the other fly to the end of the lake. And he, for grief at his flight, renewed the assault upon his pursuer, and forced him to retire.

So the white dragon, who represents the Saxons, triumphs over the red dragon, who represents the Britons. They fight over a body of water, and cast fire with their breath. In the end, the white dragon defeats the red dragon.

I fear this does not bode well for Undertaker.

Undertaker's Fate

Within the insignia for the Order of the Golden Fleece of Louix XV, the Spinel carved into a red dragon is literally called "the coast of Brittany". Here, the red dragon represents the Brittonic people from whom the Bretons descended. Undertaker is the Celtic dragon.

As for the white dragon, who represents the Saxons - I believe this will be John Brown, servant of Queen Victoria. Queen Victoria is herself descended from the Anglo-Saxon regime of England, her mother was a Saxon, as was her husband/cousin Prince Albert. Worth noting that king Vortigern, though a native Briton, married a Saxon.

Undertaker has outright stated that he does not care for Queen Victoria - but there are hints in the events of his past that his feelings towards her are a bit more strong than dislike. I think it's more accurate to say he hates her guts, especially after Claudia's death.

Queen Victoria was born in May of 1819. The massacre at Reaper HQ (a far cry from Undertaker's previous behaviour working as a reaper) likely occurred in 1819 as well. This was also the year in which the name "Cedric" first appeared in the newly published novel 'Ivanhoe'. May 1819 was also when Keats wrote "An Ode to a Nightingale", which is the cornerstone of my "Rossignol" last name theory. 1837 is the year in which Queen Victoria ascended to the throne - this lines up with the date when Undertaker officially deserted the reapers, taking his death scythe with him. 1847 is also the year of death for Undertaker's first chronological locket, Molly G.

These dates aligning link Undertaker's rebellion against his superiors to Victoria's rise to power. However, a 1v1 of Grandma Vicky vs Grandpa Reaper probably wouldn't be all that compelling of a fight.

Enter Queen Victoria's servant (in real life, and in the anime) John Brown.

John Brown in 4x10 - Sick Shades, Bro! Not conspicuous at all!

John Brown was a real person who served Queen Victoria in the aftermath of Prince Albert's death (and there is speculation that he and Vicky had an affair). But the real John Brown died on March 27, 1883 - and as I've discussed at length, Yana seems to be deliberate in the timing of significant events in relation to real world historical figures. That the 'real' John Brown in the manga died 2 years before Vincent Phantomhive was murdered is not a coincidence - rather, I think something else assumed John Brown's identity upon his death, and may have convinced Queen Victoria that Vincent Phantomhive needed to die...

There's been a lot of speculation about what John Brown is; another reaper, a demon, or an angel*. But he is most definitely not human. Not with those fuck-ass snow goggles.

*For the record, I think John Brown is indeed an angel.

Both characters of John Brown and Ash fill the same roles as the Queen's closest protector and advisor - the 'magicians' to Victoria's 'Vortigern'. The White Dragon Undertaker fights will not literally be Queen Victoria, but John Brown - and it seems Undertaker, GOAT that he is, will have finally met his match.

I think this will be Undertaker's final act in the manga, to reenact the fight between the red dragon and white dragon over the water by the half-built tower as detailed in the Historia regum Britanniae. Undertaker will fight the Saxon dragon, John Brown...

And Undertaker will lose.

In the finale of season 1 of the anime, Undertaker is distantly involved in the fight between Sebastian and Ash/Angela on the tower bridge (while the city of London burns down around them). He teams up with the other reapers (William and Grelle, and unnamed reapers #1-4) to disconnect the 'hearts of souls' feeding Ash/Angela's power. Undertaker's actions weaken Sebastian's final opponent and enable Sebastian's victory (and therefore, Ciel's). And once again - I think season 1 provides a loose interpretation of what will happen in the manga.

His role in the manga will likely be much more significant. I think he will still team up with the other reapers, but it won't be to snip black clouds because Will agreed to waive his fucking library fines. Undertaker's going to go out fighting...

I think Undertaker will meet his ultimate demise in fighting John Brown, but in doing so, he will enable Sebastian's victory and Ciel's revenge - and perhaps also stop whatever it was he learned back in 1819 that caused his initial rebellion.

Now excuse me while I go pre-grieve 😭

Lludd & Llefelys

This isn't particularly relevant - except this peaked my interest because it sounds vaguely familiar to what I understand about the Mother3 theory, so I'm throwing it in here. In the 13th century (after Historia regum Britanniae was published) the tale of Lludd and Llefelys was written as an origin for how the two dragons came to be buried underneath the pool at Dinas Emrys.

As to how the dragons became confined there, the story of Lludd and Llefelys in the Mabinogion gives details. According to the legend, when Lludd ruled Britain (c.100 BC), a hideous scream, whose origin could not be determined, was heard each May Eve. This scream so perplexed the Britons that it caused infertility, panic and mayhem throughout the realm. In need of help Lludd sought counsel on this and other matters from his brother Llefelys, a King of Gaul. Llefelys furnished the information that the scream was caused by battling dragons. The scream would be uttered by the dragon of the Britons when it was fighting another alien dragon and was being defeated. Lludd heeded the advice given to him by Llefelys and captured both dragons in a cauldron filled with mead when they had transformed themselves, as apparently dragons did, into pigs. The captured dragons were buried at the place later called Dinas Emrys, as it was regarded as the safest place to put them.

But that's not the only way this story might relate to Mother3...

Only Two Dragons - But I Thought The Dragon Must Have Three Heads???? Wait wrong show

Two dragons not enough for you? What about Sebastian, the guy who literally loves to light shit on fire, you cry out in dismay? Doesn't he get a dragon?

Fear not my friend, I've got you covered.

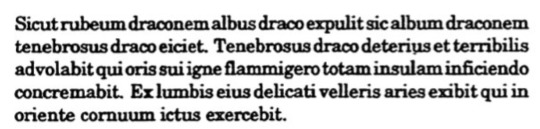

There is a much lesser known prophecy that is a sort of an addendum to Merlin's prophecy. It is contained in a series of texts called The Prophecy of the Eagle, and it foretells the Norman invasion of England...

"As the White Dragon expelled the Red Dragon so a Dark Dragon will throw out the White Dragon. The Dark Dragon, fierce and terrible, will come flying and burn up the whole island with the corrupting fire of its mouth. From its loins will come forth a ram with a fine fleece that will strike with its horns in the east."

And that's where I will pick back up in Part 2, on The Prophecy of The Three Dragons! Because really, are two dragons ever sufficient?

Thank you for reading all this! If you're interested in checking out my other theories you can find a masterpost of them here. My ask box is open and I'm always happy to talk about this stuff, if you have any comments to share or questions to ask. (Note that I will answer publicly unless otherwise specified - also note that if you've asked a question and haven't received an answer yet, it's probably because I referenced this theory and wanted to post it first!)

Going to go cry into a tub of ice cream over my prediction of Undertaker's fate now, bye.

#you best believe i wrote this entire thing to a playlist of dragons tearing each other's throats out!#black butler#black butler theory#kuroshitsuji theory#kuroshitsuji#undertaker#undertaker theory#john brown#queen victoria#sebastian michaelis#ciel phantomhive#vincent phantomhive#tower bridge#Thanks for the asks everyone they really do make my day#look no one is more upset than me myself and i about my prediction of undertaker's death#but yana i adore him 😭#tower bridge theory#john brown theory#you get a theory and you get a theory!#everyone gets a theory!#undertaker x claudia#claudiataker#undertaker x cloudia#cloudiataker

42 notes

·

View notes

Note

Are there any fae-like creatures in french myths?

I know about the story of a giant black wolf that terrorized France back in the day, but that’s all I can remember.

Legends and stories including wolves are in fact really widespread in european culture since middle age ! But yeah the most well known in France is the Beast of Gévaudan which was described as massive ! (and the one from Le petit chaperon rouge/Little red riding hood)

Concerning other creatures and fairies/faes in french legends and stories, we do have

Mélusine : fairies mentioned a bit everywhere in France, they are mostly described as women with a scaly tail lower body and are sometimes associated with mermaids or vouivres. (far from how they look like in genshin impact)

Vouivre : not to be mistaken with wyverns, vouivres are creatures described as snakes with bat wings, sometimes they are depicted having rear legs and wings (and they look very goofy like that imo). These creatures can be aquatic and in some descriptions, possess a big jewel on their forehead.

Tarasque : a creature from provencal legends, which lived in a swamp near Tarascon and terrorized and ate people. It's most popular description was of a big creature with a spiked turtle shell, six bear legs, horse ears, bull chest, lion head, a human face and a twisted tail. Legend says Ste. Marthe tamed the beast. (I swear they were just being attacked by bowser this is the same creature)

These are the one I depicted roughly in the pic above but there are many more creatures depending on the different regions of France ! (There's a lot of fairies and fantasy like creature in stories from bretagne/brittany) Some others that I find either fun or cool are :

Meneurs de loup : which translates to wolf leaders are people told to be able to talk to wolves and even transform into one, either because they are werewolves or they made a pact with the devil. (it's kinda giving spice and wolf vibes and I love that story sm)

Jambe crue/Came-cruse : Roaming in the Pyrénées at night, this thing is a single leg with an eye on the knee that eats people and runs very fast. (Idk why this one is so funny to me but oddly terrifying as well)

#french folklore#we also have fairies and mages that come from arthurian legends because i don't know how/why but some of the stories took place in france#it is said in France that Merlin used to live at some point in the forest of Brocéliande that is said to be either in brittany or normandy?#and there's that whole lancelot du lac thing as well#idk if I can choose a favorite creature in general french or not but kelpies are cool and rusalkas as well#medieval unicorns that look more like goats are dope as well#most man eating beings or creatures that use appearances to lure people are soo cool tbh#katsura otoko is an example from japanese folklore guy on the moon that feeds on your life essence the more you stare at the moon#if i recall it right..#Oh ! and Powerwolf did a song in french about beast of gevaudan ! if anyone likes power metal#the whole band’s aesthetic is priest werewolves idk why but hey half of it is right in my alley

95 notes

·

View notes

Note

Ohhhh. Tommy and Evan goes to France for their honeymoon

Lauren, queen of my days, this one is SO HARD for me you can't even imagine!!!! Because I have way too many ideas and don't know which one to choose.

See, Paris would be the easy answer. Paris is romantic, Paris is full of things to do, Paris is beautiful and it's also easier for non french people to navigate. They could go on walks for hours, following the Seine. They could visit the Louvre, Notre Dame de Paris, but also the Museum of air and space near Paris and visit an actual Concorde! They could go to Disneyland and have Champaign between rides, they could go to Montmartre and listen to music on the streets, or they could go to Les Buttes Chaumont which is the prettiest park in Paris. They could also visit La Butte Aux Cailles where I live, it's so pretty. Paris is full of wonder and Evan could rant about the Catacombs for hours while Tommy tastes every alcohol and cake possible.

But you see, France is so much more than Paris. Maybe they could go on a road trip, visit every place in France I love. Maybe even do a tour of places depending on which food or alcohol they produce???

They could go to Bretagne, have beers and discover Brocéliande's Forest and Arthurian legends. Go to the Ile aux Moines and bike through the whole island. Eat crêpes near Vannes' harbor and visit Carnac and its Standing Stones and Evan would tell stories about leprechaun and faeries and the Ankou.

They could go to Corsica, make love on marvelous beaches, eat goat cheese and drink Pietra beers. They could hike in the mountains for hours and see wild pigs and goats climbing trees (I saw it there) and they would go to Bonifacio and have a little boat tour and feed seagulls. They would eat mussels from the Étang de Diane and talk to locals about freedom and see the planes flying across Travo.

They could go to Souillac or Rocamadour, see the Gouffre de Padirac and eat duck specialties. They could go to Chambord or Chenonceau or Bois and visit every castle near the Loire. They could go to Nantes and see Les Machines de l'Ile. They could go to Bordeaux and drink way too much wine. They could go to Colmar and Strasbourg during Christmas time to feel the wonders of it.

Evan loves to learn, and Tommy loves beauty. So it's hard to imagine them coming to France because I'm not sure they would want to come back to L.A. after that.

Anyway google every place!!!!

And please send me more cute headcanon about them and I'll yap about it! ❤️

#france#french girl sipping for her country for once lmao#evan buckley#tommy kinard#911 abc#bucktommy#tevan#911 show#kinley#911 on abc#kinkley#tommy kinard headcanon#911 headcanons#evan buckley headcanon#bucktommy headcanons

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Is Jesus from France ?

Or how St Anne, his grandmother, became the patron of a random french region.

After catching your eye with this wonderfully crafted title, I will introduce you to the traditions and legends surrounding the cult of St Anne in Bretagne - France, and how they implie Mary and Jesus might have spoken baguette.

Venerated in Europe since the Middle Ages, she quicly became an important figure to christians in Bretagne, the westermost region of France, as shows the Sainte-Anne-du-Palud sanctuary, established in the year 500.

It is commonly admitted that her presence there is due to a syncretism with the celtic godess Dana / Ana, or other local divinities (Ana being an indo-european goddess, venerated across Europe, associated with the representation of the Mother Goddess "Mamm gohz (Grandmother)", mother of all Gods, which could explain the popularity of her cult).

Much later, in 1624, she appeared to Yvan Nicolazic, a farmer, and asked for a chapel to be built in Ker-Ana, where she was worshipped a thousand year ago. While building the chapel, Yvan and his brothers dug up an ancient statue of St Anne, which would later be stolen during the Revolution. After two investigations, the local bishop allowed the cult and soon crowds of pilgrims came to visit the sanctuary and witness conversions and miraculous healings. It is her "only known" apparation.

Many local legends also make her to be born there, in Merléac or Plonévez-Porzay. She is believed to be a local noble or princess, married to a cruel Lord. She fled to Galilee, either travelling all through Europe, or by sea guided by an angel. Some say she fled because she was pregnant, some that she became a mother later on, after meeting St Joachim. Some legends add that she then came back to Armoric, where she accomplished miracles.

Her cult gained even more popularity in 1854 with the dogma of the Immaculate Conception. In july 1914, she is officialy recognized as « Patrona Provinciæ Britanniæ (patron of Brittany province)" by Pope Pius X. The Sainte-Anne-d'Auray sanctuary holds the largest pardon every year, making it the third most important pilgrimage in France, after Lourdes and Lisieux. Pope John-Paul II visited the sanctuary to pray to St Anne in 1996, making him the first Pope to set foot in the region, which Macron would later introduce to Pope Francis as the "French Mafia".

Today, Bretagne or Brittany is one of the most catholic region of France. I can't help but link it to the importance of pardon ceremonies and saint worship, especially Mother Mary and St Anne, which persist even today, and are unique to the region due to the mixing with older celtic beliefs (also that is an opinion i have yet to factcheck :] ). I aslo find it very funny that, acording to those legends, Jesus would be 1/4 French, and very conforting that St Anne and Mary might be from the same region as me, i don't know, it's nice.

Hope you enjoyed learning about those local traditions, I'll link the sources bellow if you want to go further on the topic. Tysm for your time, have an amazing day !

Sources :

Anne, saint patron of Bretagne - Why is St Anne so important in Bretagne ? - St Anne's cult in Bretagne - Who is St Anne ?

#Saint Anne#Jesus multiplied the baguettes#folk catholic#queer christian#folk saint#saints#syncretism#bretagne#christian

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dragon age Meta : Breton Lavellan

My version of Clan Lavellan for Aloysius Lavellan, my Inquisitor, is inspired by Brittany and the Bretons.

And here's a lil ramble about how "Rather Death than Dishonor" became the clan's motto!

Brittany's historical motto is "Kentoc'h mervel eget bezañ saotret", which was translated on Wikipedia in "Rather death than dishonor", though there's a strong taint/dirt/filfth dimension to "dishonor".

It comes from a legend where a white haired stroat choose to be killed by Anne de Bretagne's dogs who were hunting it instead of crossing a muddy river that would have stained its fur. Admiring the animal's dedication, Anne spared its life.

Another version, my favorite, says it's Alain Barbetorte, son of the last King of Brittany and Duke of Brittany between 938 and 952) who said that to his men during a war against the Normands as he saw a stroat standing up to a fox rather than crossing that same muddy river.

NOW TO THE LAVELLAN. It's their motto as well.

Their legends say their motto, "Rather death than dishonor", has been said by an Emerald Knight to his men during the second exalted march against the Dales. Cornered by Orlesian soldiers, they're faced with a choice : Crossing a large muddy river to flee, or stand up and fight. As he remembers witnessing a Halla standing up to human hunters, refusing to cross a dirty river to preserve its coat and its whiteness, he shouts these words to his men and they fight the human soldiers until victory.

That's also why THEY particularly hold the Hallas as sacred animal, more than dalish already do.

#Dragon age#Dragon age Meta#dragon age inquisition#lavellan#clan lavellan#inquisitor lavellan#dragon age#da:i#dragon age lavellan#dalish elf#dalish elves#dragon age lore#my rambles#oc: aloysius#dragon age meta#dalish inquisitor

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Les Contes du Korrigan (1)

I want to share with you a fairytale-related BD (bande-dessinée, aka a comic book) that was part of my childhood and is, I think, quite a good way of visually exploring Breton fairytales: "Les Contes du Korrigan", "The Korrigan Tales" (or "The Tales of the Korrigan" depending on how you wish to translate it, both versions can be justified)

Fun fact: the image right above is the cover of the first volume as published in the Breton dialect! Les Contes du Korrigan got a bilingual publication - one in French, and one in the Breton language.

Les Contes du Korrigan is a BD series created by Jean-Luc Istin and the Le Breton duo (Erwan and Ronan - they wrote the scenario, while Istin did a part of the art and oversaw the organization and creation process). Its principle is quite simple: it is an anthology of fairytales and legends from the Bretagne region of France (Britanny as you call it in English, aka the "Little Britain" opposed to the "Great Britain"), reinvented in a comic book format. The title comes from the fact that our narrator, who is the protagonist of every frame story and presents individual tales, is a korrigan.

The korrigans are one of the most famous parts of the Breton folklore. They are basically Bretagne's local variation of the "lutin" (imp/sprite) and of the "nain" (dwarf) - "korr" actually is the Breton word for a dwarf. In folklore, korrigans are known to be ugly, hairy, horned and hooved little men - and they were of course strongly associated with devils and demons when the Breton folklore was christianized. The female korrigans are sometimes described as beautiful fairies or seducing enchantresses, though just as mischievious as their male counterpart. Anyway, I am not here to make a folklore lesson about korrigans (though I could if you are interested), but to share this comic:

What you see above is the opening segment of the first book of the series, "Les Trésors Enfouis" (Buried Treasures). We meet our narrator and story-host, Koc'h the korrigan. A Breton name which is pronounced "korr" like "korrigan" (he insist that it is not pronounced "kosh" or "kok"). He begins by reciting a poetic hymn to the glory of Bretagne in front of a korrigan statue, before a bird comes to poop on said statue. The bird in question isn't actually a bird, but a metamorphosis of Skoul, that Koc'h insults and chases away, promising that once turned to stone he will make a "beautiful gargoyle, when mankind invents cathedrals... in five thousand years." Indeed, this sequence is actually taking place while humanity and korrigans work together to erect menhirs and dolmens for their gods - offerings of stone, baptized in sweat and blood, and which will honor the Celtic deities for centuries to come, and shall be the last home of the korrigans when "the time of oblivion shall come"...

Koc'h offers a helpful little guide of the great "families" of the supernatural folks of Bretagne. You have the korrigans, "the people of the mounds", also called korrig, kornandon, polpigan. You have those "of the moors and the bogs", the "tan-noz", that the French people call "feux follets" (aka will o the wisp). There's the "morganed", "our brothers and sisters of the reefs". They form the "small people" or "little folk" - but they are not the only inhabitants of the Otherworld who also haunt Bretagne.

There are also the "anaon" - the unresting souls and travelling wraiths, who sometimes have to wait for centuries before they can reach purgatory or the "isles of the afterlife". The "shepherd of this sinister flock" is of course the Ankou, the reaper of the dead - renowned for his badly-oiled, creaking chariot, and for his scythe with an upside-down blade. His three "sisters" are the kannerez noz, the night washerwomen, who only attack men and offer them to help wash their own shroud... And finally there are the many "bugul noz" (the screaming spirits), most famous of which being Yannig an aod, "Jeannot de la grève", "Johnny of the beach" - these spirits will beg and implore for your help, but if you lend them a hand at best you'll lose your arm, at worst your life...

Such is Koc'h conclusion: it is no good to do business with the dead in Bretagne, while on the contrary, the Little Folks are all laugh, feasting and merriment! And it is to honor this tradition that Koc'h invites us to listen to the stories that forged the soul of the Bretagne peninsula - told in his own, korrigan-styled way...

And who is Skoul, you ask? Skoul is a bogeyman of Bretagne. His name means "bird of prey", or "kite", and he was a malevolent, lifeforce-stealing entity known to attack as much adults as children.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

of course it is the man the myth the legend jonas abrahamsen himself off the front at bretagne. of course it is.

2 notes

·

View notes