#black against empire: the history and politics of the black panther party

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Black Against The Empire Audiobook(Full History Of The Black Panther Party)!!!

youtube

Black Against The Empire Audiobook(Full History Of The Black Panther Party)!!!

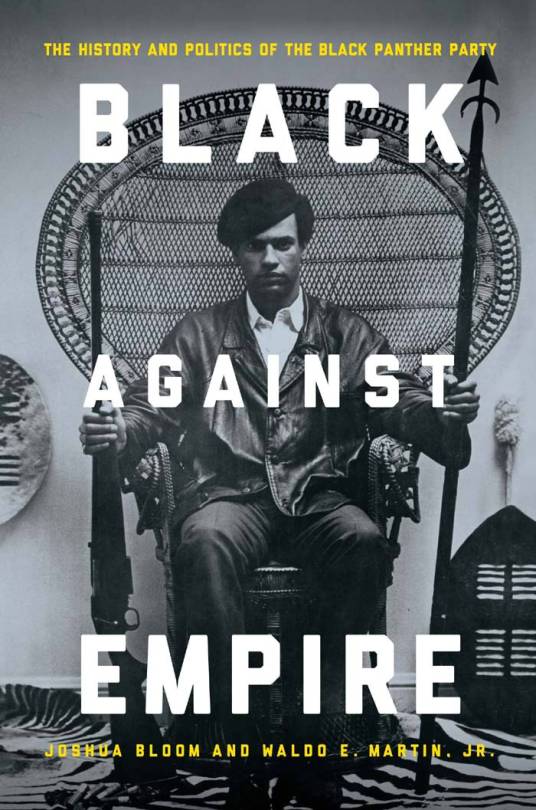

In Oakland, California, in 1966, community college students Bobby Seale and Huey Newton armed themselves, began patrolling the police and promised to prevent police brutality. Unlike the Civil Rights Movement that called for full citizenship rights for blacks within the U.S., the Black Panther Party rejected the legitimacy of the U.S. government and positioned itself as part of a global struggle against American imperialism. In the face of intense repression, the Party flourished, becoming the center of a revolutionary movement with offices in 68 U.S. cities and powerful allies around the world.

Black against Empire is the first comprehensive overview and analysis of the history and politics of the Black Panther Party. The authors analyze key political questions, such as why so many young black people across the country risked their lives for the revolution, why the Party grew most rapidly during the height of repression, and why allies abandoned the Party at its peak of influence. Bold, engrossing, and richly detailed, this book cuts through the mythology and obfuscation, revealing the political dynamics that drove the explosive growth of this revolutionary movement, and its disastrous unraveling. Informed by twelve years of meticulous archival research, as well as familiarity with most of the former Party leadership and many rank-and-file members, this book is the definitive history of one of the greatest challenges ever posed to American state power.

BLACK AGAINST THE EMPIRE: https://amzn.to/2VzenjA

YOUTUBE https://tinyurl.com/truthdogma

50 notes

·

View notes

Note

i had a korean friend (living in korea, not korean-american) who told me once that he thought korean people felt a kinship toward black americans because of their history of being continuously exploited (on the korean side he meant by china/japan/the US). obviously i took that with a grain of salt because i'm not ignorant of korea's relationship to antiblackness but i still think about it a lot.

i think an important distinction needs to be made here in which the people of korea, the people of the korean peninsula, the people of joseon, are an ethnically homogenous civilization with a shared national identity of 500 years under the kingdom of joseon and shared cultural history of 5000 years. the koreans who are able to enact material and ideological antiblackness right now are the ones benefitting from the US neocolony that is the republic of korea and the ones that are diasporic (especially in the imperial core). the dprk has historically been aligned with the ongoing political struggle of black people in the US and the black panther party frequently published the writings of kim il sung.

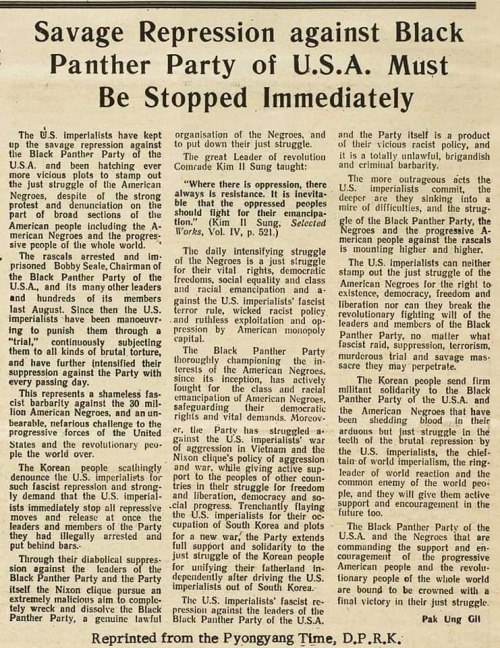

here's a document from the dprk about US antiblackness and the oppression of the black panther party around 1970.

and if you see here, it's simply on a basis of morality and moral political ideology that the korean people stand with black people in the US, there doesn't have to be emotional commonalities. it is simply political and moral necessity to speak up about our support. we are being oppressed by the same regime of US empire and global white supremacy and racial capitalism, it is of the utmost importance to stand in solidarity with other people in struggle.

it's also very cool to see this kind of document. "trenchantly flaying the US imperialists for their occupation of South Korea" goes sooo hard. the US is indeed "the chieftan of world imperialism, the ringleader of world reaction and the common enemy of the world people." the dprk's political morals are a really refreshing reminder that korean people do not all have the same relationship to global hegemony and there have always been korean people who are against empire and struggling for liberation.

and what you're actually talking about here is about the empathetic resonances between the political struggles of black people and korean people, which do exist. they are there and it's important to feel them to begin any kind of political work as a korean person, though politics should not be based around anecdotal and emotional resonances only. korea was known as the shrimp between 2 whales between china and japan for 5000 years and china's word for korean people is eastern barbarians. many artistic, technological, and cultural innovations credited to china and japan are actually korean. china and japan would kidnap hundreds of artisans and scholars every time korean people invented something they wanted and usually the korean kingdom (unified silla, joseon, etc) was a vassal to china or economically beholden to japan so they couldn't stop it. even cherry blossom trees that are the japanese national symbol were first taken from the silla kingdom. and then planted all over joseon during japanese occupation hundreds of years later to show that joseon now belongs to japan. the constant cycles of theft, labor exploitation, disrespect, and humiliation are present in both peoples for sure. and korea spent decades freeing ourselves from japanese colonization and succeeded, only to be overtaken by US military occupation 3 days later. and then divided in half and made to be in perpetual war with our other half.

there are resonances with black people's constant struggle against institutional, ideological, and cutlural violence that seems to be never ending because of the strength of the US empire and global antiblackness. but both of our people can and will be freed, and the empire is decaying as we speak. we both have a lot of our people working for the colonizer's side but that can shift as well. i believe it. we have the same enemy and we outnumber them, we have been struggling for liberation and will one day succeed.

the important distinction here as well is that black people have singularly been exploited in the form of chattel slavery and the ideological work of whiteness to justify chattel slavery is the racial formation of the entire world. the entire world operates on an economic and ideological system of antiblackness.

i think every korean person coming to terms with the truth of the world needs to necessarily do massive amounts of academic and internal and physical work to come to terms with global antiblackness and our part in it, to redistribute any resources we have and support black people's vital struggle against empire. that is the first step to actual material solidarity, korean people have to make those changes within themselves and their lives first. like to even be able to relate to black people normally without the distortion of global narratives about blackness is going to require a lot of work. restructuring the way you and relate to the world and changing how you move in the material world as a result of that political realignment is deeply necessary for undoing the antiblackness embedded in everyone.

51 notes

·

View notes

Text

"It is my belief that Ronald Reagan is a punk, a sissy, and a coward, and I challenge him to a duel. I challenge the punk to a duel to the death and he can choose his own weapon: it could be a baseball bat, a gun, a knife, or a marshmallow. I'll beat him to death with a marshmallow." - Eldridge Cleaver 1968

Source- BLACK AGAINST EMPIRE: The History and Politics of The Black Panther Party by Joshua Bloom and Waldo E. Martin, JR.

Page 137

#black panther#History#Black history#BLACK AGAINST EMPIRE#Joshua Bloom#Waldo E. Martin Jr#The Black Panther Party#Eldridge Cleaver#class war#we will survive of spite alone if we must#america#anti imperial

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Black in Brooklyn - Study guide for The Sun Rises in the East

Study Guide: The Sun Rises in the East

1. Summary of the Documentary: The Sun Rises in the East explores the history and impact of The East, a cultural and educational organization founded in 1969 in Bedford-Stuyvesant, Brooklyn. The documentary highlights how The East created a hub for Black liberation through education, arts, and economic empowerment. The film traces the rise of institutions such as the Uhuru Sasa Shule (Freedom Now School), which offered Afrocentric education, and cultural centers that celebrated Black art and identity.

2. Importance in the Black Liberation Movement: The East was a cornerstone of the Black Power and Pan-African movements in Brooklyn, fostering self-determination and community control over education. By emphasizing African heritage, cooperative economics, and artistic expression, The East empowered Black communities and influenced a generation of activists, educators, and artists. Their commitment to self-reliance laid the groundwork for future community-controlled institutions.

3. Key Figures and Organizations:

Jitu Weusi: A founding member of The East and a leader in the African American Teachers Association, Weusi was a driving force for Black-led education reform.

Al Vann: An educator and politician, Vann was instrumental in advocating for community control of schools.

Fela Barclift: Founder of Little Sun People, a preschool rooted in African-centered education.

Adyemi Bandele & K. Menusah Wali: Cultural leaders deeply involved in The East's arts and educational initiatives.

Bayard Rustin: Though not part of The East, his work in civil rights and education influenced the movement’s emphasis on self-determination.

Organizations from The East:

Uhuru Sasa Shule: Afrocentric school emphasizing African history and culture.

Little Sun People: Early childhood education program with an African-centered curriculum.

Dwana Smallwood Performing Arts Center: Promotes arts education and community engagement.

African American Teachers Association (AATA): Advocated for Black educators and community-controlled schools.

Richard Beavers Gallery: Supports contemporary Black artists and cultural expression.

4. Questions for Further Exploration:

How did The East’s model of Afrocentric education impact public school reform movements in the 1970s?

What role did cooperative economics play in sustaining The East, and how can those principles be applied today?

How did The East intersect with broader Black Liberation movements across the U.S.?

5. Books for Further Reading:

A View from The East by Kwasi Konadu - Link

The Crisis of the Negro Intellectual by Harold Cruse

Education at the Crossroads by Carter G. Woodson

From #BlackLivesMatter to Black Liberation by Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor

The Miseducation of the Negro by Carter G. Woodson

How We Get Free: Black Feminism and the Combahee River Collective edited by Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor

Blues People by Amiri Baraka

Black Against Empire: The History and Politics of the Black Panther Party by Joshua Bloom and Waldo Martin

Pedagogy of the Oppressed by Paulo Freire

We Want to Do More Than Survive by Bettina Love

6. Related YouTube Videos:

"The Sun Rises in the East | Official Trailer" (YouTube)

"Jitu Weusi on Black Education" (YouTube)

"Bayard Rustin: The Forgotten Civil Rights Leader" (YouTube)

"School Colors Podcast: The Fight for Education Equity in Brooklyn" (YouTube)

"The History of the Uhuru Sasa Shule" (YouTube)

7. Prompts for Further Research:

Investigate the relationship between The East and the Black Power movement.

Research the history and impact of the CCNY takeover.

Explore the role of WBAI’s Education at the Crossroads in spreading Afrocentric education.

Compare The East with similar movements such as the Black Panther Party’s Oakland Community School.

Study the contributions of women leaders in The East.

8. Prompts for MidJourney Image Creations:

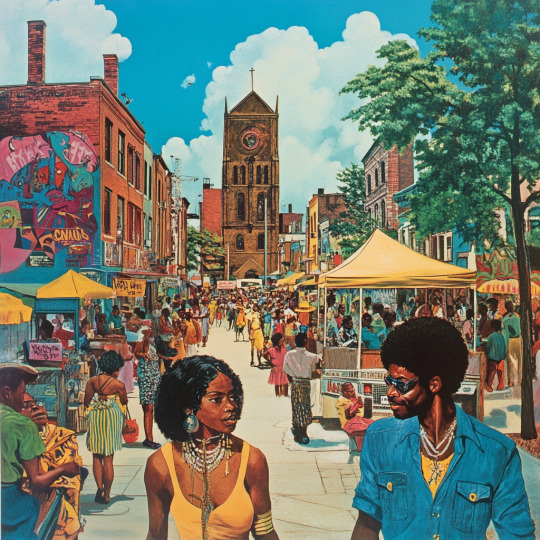

"Afrocentric classroom at Uhuru Sasa Shule, filled with students learning African history and art." (Tags: Afrocentric, classroom, education, black liberation)

"A bustling 1970s street scene in Bedford-Stuyvesant, with community murals and vendors celebrating Black culture." (Tags: Brooklyn, Black culture, street scene, 1970s)

"A vibrant community meeting at The East, with speakers addressing the crowd under a Pan-African flag." (Tags: community, activism, Pan-African, Black liberation)

9. Tags for Social Media: #TheEast #BlackLiberation #AfrocentricEducation #BrooklynHistory #JituWeusi #UhuruSasa #PanAfricanism #BlackHistory #CulturalRevolution

#TheEast#BlackLiberation#AfrocentricEducation#BrooklynHistory#JituWeusi#UhuruSasa#PanAfricanism#BlackHistory#CulturalRevolution#black history month#chatgpt#blackhistorymonth#africanamericanhistory#midjourney#civilrights#equality#justice#ai generated

1 note

·

View note

Note

3, 6, and 14 for the book asks!

3. What were your top five books of the year?

Love this question!! I'm gonna count series together otherwise it doesn't feel representative LOL

A Psalm for the Wild-Built & A Prayer for the Crown-Shy by Becky Chambers (highly recommend!!)

Mecca by Susan Straight

Braiding Sweetgrass by Robin Wall Kimmerer

Grandmaster of Demonic Cultivation & Heaven Official's Blessing by Mo Xiang Tong Xiu (ok lumping these together is definitely cheating... but i don't wanna choose!!)

How to Hide an Empire: A History of the Greater United States by Daniel Immerwahr (gonna be thinking about this book forever)

6. Was there anything you meant to read, but never got to?

My TBR list is a million miles long LOL but coming up soon are probably Tomorrow and Tomorrow and Tomorrow, This Is How You Lose the Time War, Black Against Empire: The History and Politics of the Black Panther Party, Birnam Wood, and The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks

14. What books do you want to finish before the year is over?

I'm actually in the middle of the Heaven Official's Blessing series but at the rate I'm tearing through them I'll definitely finish them soon! Just gotta get my hands on the last book...

Thank you for asking!!!

1 note

·

View note

Quote

By the time Huey Newton became involved in the Afro-American Association at Merritt, he could debate theory as well as any of his peers. Yet he had a side that most of the budding intellectuals around him lacked; he knew the street. He could understand and relate to the plight of the swelling ranks of unemployed, the "brothers on the block" who lived outside the law. Newton’s street knowledge helped put him through college, as he covered his bills through theft and fraud. But when Newton was caught, he used his book knowledge to study the law and defend himself in court, impressing the jury and defeating several misdemeanor charges.

Joshua Bloom & Waldo E. Martin, Black against Empire: The History and Politics of the Black Panther Party (2013, University of California Press)

#Black against Empire: The History and Politics of the Black Panther Party#Joshua Bloom#Waldo E. Martin#theory#the phantom of liberty#I fought the law

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

[Lemme borrow and expand from my woefully neglected Resources / Bibliography.]

Organised crime, with a slant towards the Italian mafia because it fascinates me the most:

Kelly Barksby, “Constructing criminals: the creation of identity within criminal mafias” (Keele University, 2013)

Filippo Spadafora, Origins of the Sicilian Mafia (2010)

This Rogue, Mafia Lore: Honour and Blood (2016)

Pino Arlacchi, Mafia Business: The Mafia Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism (Oxford University Press, 1988) *

Letizia Paoli, “Italian Organised Crime: Mafia Associations and Criminal Enterprises” in Global Crime Vol. 6, No. 1 (Routledge, 2004)

Diego Gambetta, The Sicilian Mafia: The Business of Private Protection (Harvard University Press, 1993)

John Dickie, Cosa Nostra: A History of the Sicilian Mafia (Palgrave Macmillan 2004)

Henner Hess, Mafia and Mafiosi (New York University Press, 1998)

Marco Gasparini, The Mafia: History and Legend (Flammarion , 2011) *

Alexander Stille, Excellent Cadavers: The Mafia and the Death of the First Italian Republic (Vintage, 1995)

Mark Bowden, Killing Pablo: The Hunt for the World’s Greatest Outlaw (Atlantic Books, 2002)

David E. Kaplan & Alec Dubro, Yakuza: Japan’s Criminal Underwold (University of California Press, 2002)

Peter B. E. Hill, The Japanese Mafia: Yakuza, Law, and the State (Oxford University Press, 2003)

Gangs:

Mark S. Fleisher, Beggars and Thieves: Lives of Urban Street Criminals (The University of Wisconsin Press, 1995)

Darrell J. Steffensmeier, Delinquent Girls: Contexts, Relationships, and Adaptation (Springer-Verlag, 2012)

Herbert C. Covey, Crips and Bloods: A guide to an American subculture (Greenwood, 2015)

Deborah Lamm Weisel, Contemporary Gangs: An Organizational Analysis (LFB Scholarly Publishing, 2002)

David Skarbek, The Social Order of the Underworld: How Prison Gangs Govern the American Penal System (Oxford University Press, 2014)

Ken Gelder, Subcultures: Cultural Histories and Social Practice (Routledge); The subcultures reader (with Sarah Thornton, Routledge, 1997)

M.G. Bullen, Thief in Law: A guide to Russian prison tattoos and Russian-speaking organised crime gangs (One’s Own Publishing House, 2016)

Illegalism:

Bernard Thomas, The Lives of Sailor, Thief, Anarchist, Convict Alexandre Marius Jacob (1879-1954) (Tchou Éditions, 1970)

Jean-Marc Delpech, “Parcours et Réseaux d’un Anarchiste: Alexandre Marius Jacob, 1879-1954“, (Université de Lorraine, 2006)

Richard Parry, The Bonnot Gang: The story of the French illegalists (Rebel Press, 1987)

Doug Imrie, “The illegalists” in Anarchy: a Journal Of Desire Armed (1994)

Chris Ealham, Class, Culture and Conflict in Barcelona, 1898-1937 (Routledge, 2005)

Antonio Tellez, Sabaté, Guerilla Extraordinary / La Guerriglia Urbana in Spagna: Sabaté (1974)

Klaus Schönberger, VaBanque: Bankraub – Theorie, Praxis, Geschichte (Assoziation A, 2000) ["Bank Robbery: Theory, Practice, History" - a German book which AFAIK has only been translated to Italian and Greek.]

Insurgencies:

Eric Hobsbawm, Revolutionaries (Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1973) (see here an excerpt on "Cities and Insurrection"); Bandits (Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1969)

lse Biel, “Zapatista Materiality Disseminated: A Co-Construction Reconsidered” (University of New Mexico, 2012)

Coutrney Jung, The Moral Force of Indigenous Politics: Critical Liberalism and the Zapatistas (Cambridge University Press, 2008)

Joshua Bloom & Waldo E. Martin Jr., Black against Empire (University of California Press, 20123) [on the Black Panther Party]

Sundiata Acoli, A Brief History of the Black Panther Party and Its Place In the Black Liberation Movement (1985)

Abel Paz, Durruti: the people armed (Black Rose, 1976) [I THINK this is the english translation of Durruti: el proletariado en armas later published as Durruti en la revolución española, which I meant]

Ralf Reinders & Ronald Fritzsch, Die Bewngung 2.Juni (1985) ["The 2 June Movement", don't know if it's translated in English.]

That's… hardly an expertly curated list, esp. the revolutionary stuff. I read my foundational texts in that department mostly by borrowing, rarely in English, and long before I had organisational skills, or Calibre. Essential topics aren't covered here. You gotta look up RAF, the Red Brigades, Carlos, so many things.

The subject is HUGE, op! Absolutely enormous. I get dizzy thinking about it.

Please recommend me reliable books, documentaries, pieces of journalism etc. that you know of about:

organized crime

semi-organized crime i.e. street gangs and the like

terrorists

guerrilla insurgencies

and similar things.

I'm very interested understanding illegitimate (i.e. not conducted by a government) organized violence and how it functions, but naturally it's hard to find good information.

754 notes

·

View notes

Photo

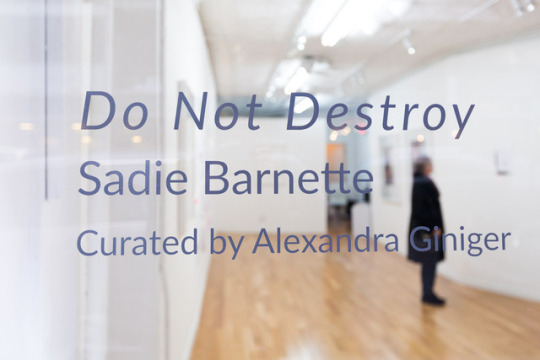

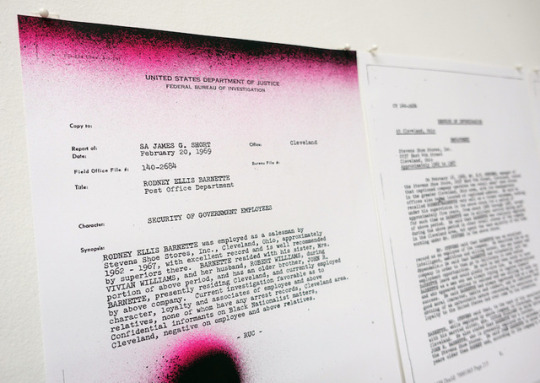

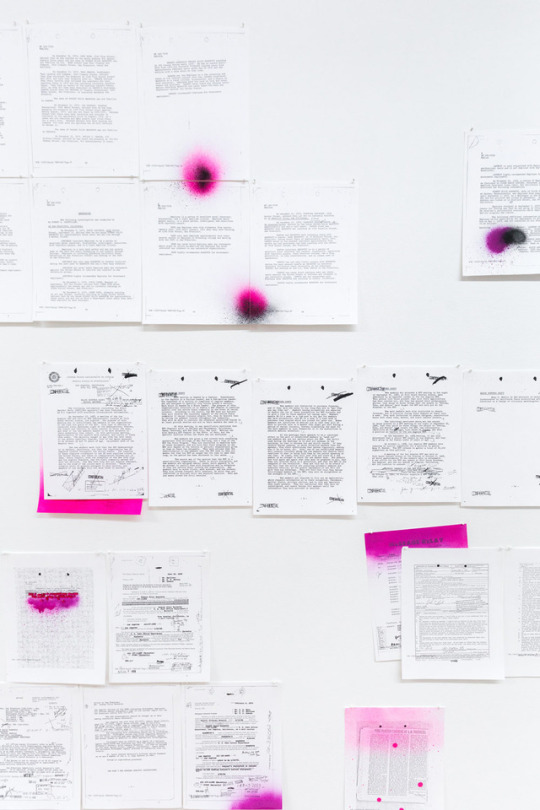

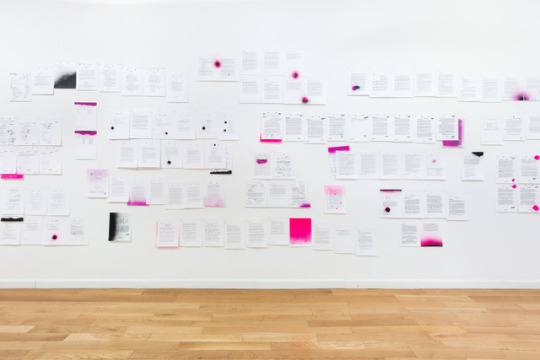

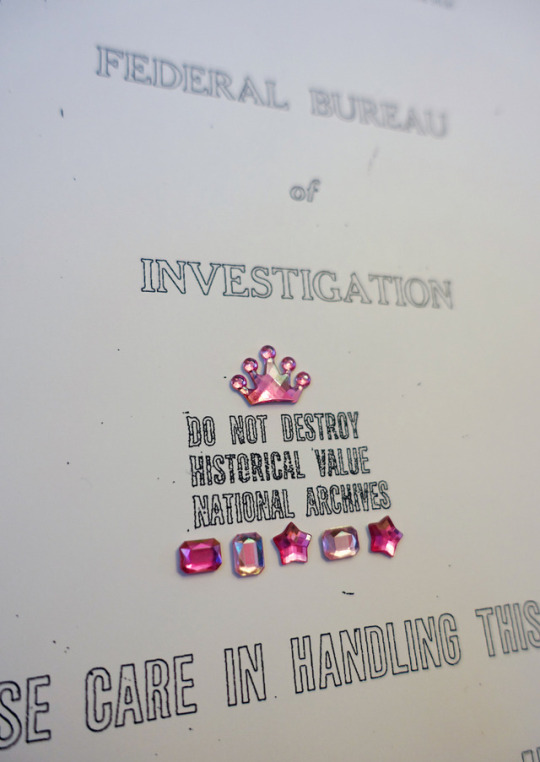

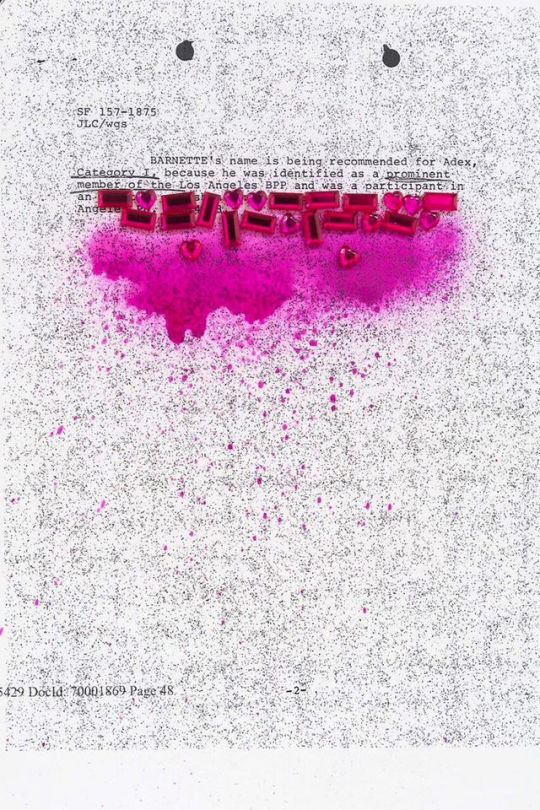

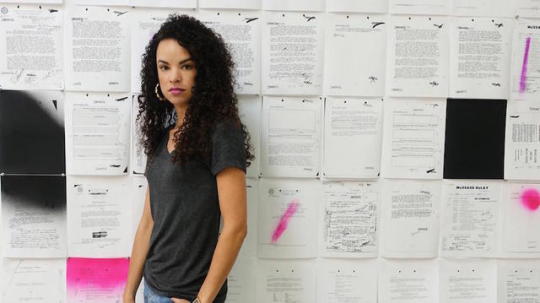

Sadie Barnette Reclaims Her Father’s Black Panther FBI File As Art

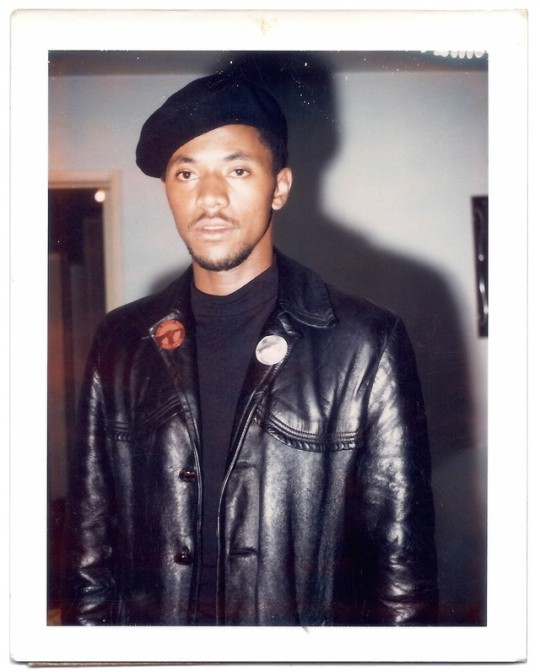

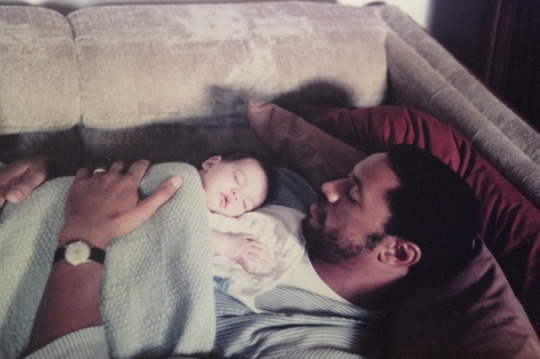

Artist Sadie Barnette’s family tree includes a 500-page FBI file. In 1968, the United States government placed her father, Rodney Barnette, under surveillance. For decades, his every daily detail was logged and noted. Family members, employers, even his former high school teachers were interrogated. The reason for the target on his back: Rodney was a founding member of the Compton, California chapter of the Black Panther Party for Self Defense.

In an era where J. Edgar Hoover’s FBI sought to actively, though covertly, criminalize and destroy the Panthers—and arguably any prominent or rising Black political leader—the elder Barnette was of hundreds of activists subject to state-sanctioned harassment and intimidation, their organizations infiltrated and discredited. Other revolutionaries were incarcerated; some were assassinated.

Growing up, Sadie Barnette’s father’s history was never a secret. It seems almost inevitable that the young artist whose work is dedicated to excavating the constructs of identity would turn her gaze to his FBI file, newly available through a Freedom of Information Act request. For Do Not Destroy, her first solo exhibition in New York City, Barnette reframes the pages of the dossier as a father-daughter conversation. With the intervention of her own visual presence—through unapologetically girly embellishments and abstractions—she subverts the government’s narrative with her own. The spurts of hot pink spray paint on black-and-white pages restore a sense of sinew and blood, returning a dignity of wholeness to the life described therein. And so, it is from an inheritance of being targeted and surveilled, that Barnette has grown a garden of reclamation.

Mass Appeal sat down with the Oakland-born artist to learn more.

Mass Appeal: Your family knows what it is like to be targeted, to be painted as a “terrorist.” What are some of your thoughts on the current administration’s rhetoric and actions in dehumanizing and criminalizing believers of Islam, refugees and the undocumented?

Sadie Barnette: One of the things that was really striking about my dad’s file was that my dad was fired from his job at the Post Office because of his involvement with the Panthers. But, the law used to get him fired was something that President Truman had put on the books. It was an Executive Order that talked about behavior unbecoming to a government employee. That’s what they used to get my dad fired because he was cohabitating with a woman who he wasn’t married to… That was behavior that was unbecoming of a government employee. But, the reason that law was put on the books was to get gay people out of government jobs. So it’s another one of those examples where people think “Oh, this law doesn’t affect me. I’m not Muslim. I’m not an immigrant. I’m not trans. This has nothing to do with me.” But a similar law or laws can be used to target whoever the government is considering inconvenient at the time or whoever is questioning things or fighting for their rights. That’s definitely something that we have to keep in mind today.

Was activism and an awareness beyond self-interest part of your birthright or did you come into your own political awakening?

It was always something I held in my heart… I looked at situations with systemic analysis. If the police beat someone up or say if somebody in the family didn’t have access to something that they needed, I would always see it through a lens of systemic problems in our country. When I was in high school, I was very aware that students were being criminalized and were being shuttled along this school-to-prison pipeline. So those things were always on my mind. And growing up in the Bay area, there is a lot of activism and systemic analysis.

How did that activism and analysis start to factor in or feed your artistic growth?

I think they definitely go hand-in-hand. All art is political even when it’s not. Because it’s still a political choice if you are choosing to ignore politics. Often times, just the act of making art or changing the way people think even if its meant as an act of poetry is inherently political. People need escape and fantasy and fiction and need to feel beautiful and seen and heard. So for me even in my work that isn’t directly talking about the FBI file, it is still a commitment to… The act of making art is still a commitment to humanity.

What prompted your dad to want to look at your father’s file, and then what prompted you to want to work with the material?

My dad always wondered what experiences were tied to his FBI surveillance, harassment and intimidation. He wanted the file and so filed a Freedom of Information Act request to get it. It took about four years to get the file. I’m not sure what at that exact moment made him want to really face what a lot of people don’t want to look at. It can be too painful. But, he knows that it is bigger than himself. He also was very lucky that he wasn’t assassinated at the time or thrown in jail. He really is a strong person that survived a lot and still is able to see the value in sharing his experiences. I’ve always been interested in telling the story of my parents and also the activism and the cultural outpourings of that time period. This just seemed like the perfect way to do that—using this file for good and reclaiming it.

Did you wrestle with how much of the file you should work with or alter or how much you should let it speak for itself?

I definitely had to wrestle with it. The fact that the project’s first debut was at the Oakland Museum for the Black Panther exhibit, All Power to the People: Black Panthers at 50 really helped give me confidence that this could be framed and contextualized properly because the show is really dedicated to talking about the full complexities of the Black Panthers, not just like the cool image or that kind of thing. So being included in the Oakland Museum exhibition was what really made me excited about making the final decisions as to how to use this material.

I think it will be the type of project that’ll be ongoing. I’m not the kind of artist that thinks this is the like the ultimate or some kind of end. It’s no [laughs] magnum opus—it’s ongoing. One of the things I value about being an artist is that you can be unsure. You can question and try things. I’m sure I will work in many ways with this file. At some point, I’d like to make a book project with it. My intention often when I’m making art is not about making things; it’s about seeing things. So, the re-framing, the juxtaposing of these files and just a few gesture on my part was really what I wanted to do to allow the pages to speak for themselves and then for the viewer to bring something new to it.

The work also calls into the conversation the political activists that were murdered. Others were arrested and some still incarcerated to this day. Is it imperative to you as we celebrate the 50th Anniversary of the Panthers?

Absolutely. It is hugely important. And I think it is something that we still don’t know enough about. There are a ton of names of people in my dad’s file who he knew, who were his mentors who were killed. John Huggins. Bunchy Carter. They were murdered at UCLA. It is a double tragedy if their lives were not only stolen and taken away from their families but that they are also not remembered in the historical consciousness.

Have you become a student of the era as a result?

Definitely. I’ve been reading several books. One is called The Burglary by Betty Medsger. She basically was one of the reporters to receive the first batch of stolen FBI files around 1972 from this small FBI office in Pittsburgh. These anti-war activists realized that the movement was being surveilled so heavily that the only way to expose what the FBI was actually doing was to break into this office. I’ve been learning a ton about J. Edgar Hoover. It’s amazing to think that these activists were just regular, hard-working people. They weren’t criminals, they were actually repelled by [the thought of] breaking into this office, but they knew it would be worse to let Hoover run the FBI unchecked and run democracy into the ground. The other book is Black Against Empire: The History and Politics of The Black Panther Party by Joshua Bloom and Waldo E. Martin, Jr.

What did working with this file teach or surprise you about your dad or by extension about yourself?

Well, it’s hard to say. I’m pretty close to my dad so most of the things I knew already. I definitely learned more about our government than I did about my family. Questioning the government, dissent, is legal. It is written into the Constitution. If the government isn’t working properly, then the people are to change it. But people who are in power want to protect their power. As a descendent of slaves and Native Americans in this country, I have never felt like we are included when they say “We the People.” I’ve never felt like this country was mine. My ancestors built this country, but it was never for them either. I’ve always felt that if this country was actually going to be for everyone, then we would have to first really face some things that people don’t want to talk about.

Do Not Destroy is on view through Saturday, February 18, 2017 at Baxter St at Camera Club of New York (126 Baxter St, NY).

#sadie barnette#do not destroy#j. edgar hoover#j edgar hoover#fbi#federal bureau of investigation#black panther party#black panther party for self defense#compton california#california#all power to the people: black panthers at 50#all power to the people black panthers at 50#john huggins#bunchy carter#the burglary#betty medsger#black against empire: the history and politics of the black panther party#black against empire the history and politics of the black panther party#joshua bloom#waldo e. martin jr.#waldo e martin jr#mass appeal#american history#black history#history#art#black art#baxter st#rodney barnette#domestic terrorism

41 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Uncle Sammy don’t shuck and jive me, I’m hip the popcorn jazz changes you blow, You know damn well what I mean, You school my naive heart to sing red-white-and-blue-stars-and-stripes songs and to pledge eternal allegiance to all things blue, true, blue-eyed blond, blond-haired, white chalk white skin with U.S.A. tattooed all over, When my soul trusted Uncle Sammy, Loved Uncle Sammy, I died in dreams for you Uncle Sammy, Died in dreams playing war for you Uncle Sammy, No, I don’t want to hear that crap, You jam your emasculate manhood symbol, puff with Gonorrhea, Gonorrhea of corrupt un-realty myths into my ungreased, nigger ghetto, black-ass, my Jewish-Cappy-Hindu-Islamic-Sioux-sure, free public health penicillin cured me, But Uncle Sammy if you want to stay a freak-show strongman god, Fuck your motherfucking self, I will not serve.

a black anti-war poem by Bobby Seale, May 1966

#poems#im ready a book called Black Against Empire: The history and politics of the Black Panther Party#and it features this poem#and i love it#poem#black poems#bobby seale

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Black History Month: some reading to get you started

Celebrate Black excellence with these titles

A Black Women's History of the United States by Daina Ramey Berry, Kali Nicole Gross

A vibrant and empowering history that emphasizes the perspectives and stories of African American women to show how they are--and have always been--instrumental in shaping our country In centering Black women's stories, two award-winning historians seek both to empower African American women and to show their allies that Black women's unique ability to make their own communities while combatting centuries of oppression is an essential component in our continued resistance to systemic racism and sexism. Daina Ramey Berry and Kali Nicole Gross offer an examination and celebration of Black womanhood, beginning with the first African women who arrived in what became the United States to African American women of today. A Black Women's History of the United States reaches far beyond a single narrative to showcase Black women's lives in all their fraught complexities. Berry and Gross prioritize many voices: enslaved women, freedwomen, religious leaders, artists, queer women, activists, and women who lived outside the law. The result is a starting point for exploring Black women's history and a testament to the beauty, richness, rhythm, tragedy, heartbreak, rage, and enduring love that abounds in the spirit of Black women in communities throughout the nation.

Black Detroit: A People's History of Self-Determination by Herb Boyd

The author of Baldwin’s Harlem looks at the evolving culture, politics, economics, and spiritual life of Detroit—a blend of memoir, love letter, history, and clear-eyed reportage that explores the city’s past, present, and future and its significance to the African American legacy and the nation’s fabric. Herb Boyd moved to Detroit in 1943, as race riots were engulfing the city. Though he did not grasp their full significance at the time, this critical moment would be one of many he witnessed that would mold his political activism and exposed a city restless for change. In Black Detroit, he reflects on his life and this landmark place, in search of understanding why Detroit is a special place for black people. Boyd reveals how Black Detroiters were prominent in the city’s historic, groundbreaking union movement and—when given an opportunity—were among the tireless workers who made the automobile industry the center of American industry. Well paying jobs on assembly lines allowed working class Black Detroiters to ascend to the middle class and achieve financial stability, an accomplishment not often attainable in other industries. Boyd makes clear that while many of these middle-class jobs have disappeared, decimating the population and hitting blacks hardest, Detroit survives thanks to the emergence of companies such as Shinola—which represent the strength of the Motor City and and its continued importance to the country. He also brings into focus the major figures who have defined and shaped Detroit, including William Lambert, the great abolitionist, Berry Gordy, the founder of Motown, Coleman Young, the city’s first black mayor, diva songstress Aretha Franklin, Malcolm X, and Ralphe Bunche, winner of the Nobel Peace Prize. With a stunning eye for detail and passion for Detroit, Boyd celebrates the music, manufacturing, politics, and culture that make it an American original.

Black Against Empire: The History and Politics of the Black Panther Party by Joshua Bloom, Waldo E. Martin Jr.

In Oakland, California, in 1966, community college students Bobby Seale and Huey Newton armed themselves, began patrolling the police, and promised to prevent police brutality. Unlike the Civil Rights Movement that called for full citizenship rights for blacks within the U.S., the Black Panther Party rejected the legitimacy of the U.S. government and positioned itself as part of a global struggle against American imperialism. In the face of intense repression, the Party flourished, becoming the center of a revolutionary movement with offices in 68 U.S. cities and powerful allies around the world. Black against Empire is the first comprehensive overview and analysis of the history and politics of the Black Panther Party. The authors analyze key political questions, such as why so many young black people across the country risked their lives for the revolution, why the Party grew most rapidly during the height of repression, and why allies abandoned the Party at its peak of influence. Bold, engrossing, and richly detailed, this book cuts through the mythology and obfuscation, revealing the political dynamics that drove the explosive growth of this revolutionary movement, and its disastrous unraveling. Informed by twelve years of meticulous archival research, as well as familiarity with most of the former Party leadership and many rank-and-file members, this book is the definitive history of one of the greatest challenges ever posed to American state power.

Satch, Dizzy, and Rapid Robert: The Wild Saga of Interracial Baseball Before Jackie Robinson by Timothy M. Gay

Before Jackie Robinson integrated major league baseball in 1947, black and white ballplayers had been playing against one another for decades--even, on rare occasions, playing with each other. Interracial contests took place during the off-season, when major leaguers and Negro Leaguers alike fattened their wallets by playing exhibitions in cities and towns across America. These barnstorming tours reached new heights, however, when Satchel Paige and other African- American stars took on white teams headlined by the irrepressible Dizzy Dean. Lippy and funny, a born showman, the native Arkansan saw no reason why he shouldn't pitch against Negro Leaguers. Paige, who feared no one and chased a buck harder than any player alive, instantly recognized the box-office appeal of competing against Dizzy Dean's "All-Stars." Paige and Dean both featured soaring leg kicks and loved to mimic each other's style to amuse fans. Skin color aside, the dirt-poor Southern pitchers had much in common. Historian Timothy M. Gay has unearthed long-forgotten exhibitions where Paige and Dean dueled, and he tells the story of their pioneering escapades in this engaging book. Long before they ever heard of Robinson or Larry Doby, baseball fans from Brooklyn to Enid, Oklahoma, watched black and white players battle on the same diamond. With such Hall of Fame teammates as Josh Gibson, Turkey Stearnes, Mule Suttles, Oscar Charleston, Cool Papa Bell, and Bullet Joe Rogan, Paige often had the upper hand against Diz. After arm troubles sidelined Dean, a new pitching phenom, Bob Feller--Rapid Robert--assembled his own teams to face Paige and other blackballers. By the time Paige became Feller's teammate on the Cleveland Indians in 1948, a rookie at age forty-two, Satch and Feller had barnstormed against each other for more than a decade. These often obscure contests helped hasten the end of Jim Crow baseball, paving the way for the game's integration. Satchel Paige, Dizzy Dean, and Bob Feller never set out to make social history--but that's precisely what happened. Tim Gay has brought this era to vivid and colorful life in a book that every baseball fan will embrace.

#black history month#black history#non-fiction#nonfiction books#reading recommendations#book recs#recommended reading#library#civil rights#black excellence#nonfiction#booklr#tbr#to read

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Record Begins With a Song Of Rebellion

First Draft Of the Capitalist Surrealist Writing Project. Steal and appropriate, critique and interrogate, with the author's full endorsement and permission. Looking (back)(for)wyrds After the Bush interregneum and the long, terrible, progress destroying Reagan years, the American empire had something like a moment of hope. Riding high on the peace dividend and a delusion of idealism among the donating classes, the economic aristocracy which in effect was the senior partner in “American Democracy” (and so duly represented in both parties) and the voter was a paternalized junior to be both petted and protected had selected the Clinton dynasty. The grand bargain between labour and capital against the state resulted in the bitter fruit of the Bush years, as Conservatives paternalists rightly mocked the Clintonian urge to middling action on domestic issues while gladly partnering with him to rob labour at large. While a wealth transfer had already been going on as part of a trend for the better part of a century, this phase in which a semi-coherent ruling class dynamic of the donating classes and the government service classes became visible. It is beyond satire now, but this was not always so visible, as racism, white supremacy, American exceptionalism, various fundementalist and conservative (as well as equally harmful, supposedly liberal versions of the same) religious beliefs; Turtle Island was rife with reasons for temporary cross class solidarity in order to oppose an other or to advance an idealistic goal.

And yet moments of class consciousness and solidarity have perenially emerged, from the “grassroots” as the insiders like to say. They frame the people as “the base” or “the grassroots” and narrowly target their interests to make people find conflict with each other. It is irrelevent (for this missive) whether this is a conscious, semi-conscious, or unconscious process; it is enough to notice it happening. Despite this, moments in the pre new-modern (to be defined later, promise~) politics that predate terms like Black Lives Matter or Trans Rights are Human Rights show that these movements represent an unbroken chain of revolutionary attempts at self-consciousness and conscience transformation that coincide and are just as important as any history of violence. The Ides of March, and the campaign of anonymous internet citizens against Scientology, represents such a moment. Occupy Wall Street was such a movement. “We’re Here, We’re Queer, Get Used To It!” was such a phrase. The many quotes attributed to names like Mandela and James Baldwin; the Black Panthers, the revolutionary feminists, the Hippie movement, down back to the (In the American mind) hoary days of yore when the Wide Awakes would march a brass band around the houses of pro slave Senators.

It is a poor yet accurate summation to say that the ‘present’ (a dubious notion) political reality is the sum of all of these and more; a reader can orient themselves to the history of late stage capitalism by the growth of the donating classes influence and the acceleration of their detachment from society at large. Moments which also impact this reality are the donating classes sense of pessimism about the future; the devaluing of nearly all forms of labour, the increasing visibility of law enforcement brutality; the list can be referenced in the moment to moment, wide eyed and angry reporting of self-matyring, news-junkie amateur journalists found anywhere online, the shocked and angry expressions of young activists at protests and the weary, numbed faces of the old. Up and down the class system, there has been a wide spread death of hope.

Enter the climate crisis.

Before climate consciousness achieved real steam, our escatological fears were (mostly) confined to the realm of human action or cosmic events unimaginable (and unrelatable) to the modern person’s experience of life. For decades, the effects of climate change were reported to a world told not to care. As Terrance Mkenna said, ““The apocalypse is not something which is coming. The apocalypse has arrived in major portions of the planet and it’s only because we live within a bubble of incredible privilege and social insulation that we still have the luxury of anticipating the apocalypse.”

The impact of this can and will be expanded upon, but it is safe to say that the bubble has been popped. Whatever finds popular currency within the dialogue around it, that the climate is changing rapidly in ways inemical to human society at large/at present is true by material impact; people everywhere have experienced some negative result of the changing conditions, and there is a rising anxiety in the classes who cannot afford an escape pod or fortress bunker that the people they’ve entrusted themselves to intend to withdraw to safety and abandon them, or even expose them to more harm in order to “make more of the earth’s carrying weight available in the reclamation” (this kind of talk is not alien to them, though this specific quotation is my own invention.

It is important to acknowledge that the bubble has popped. It is the exclamation on Capitalist Realism; it is the moment of awareness, that encounter with a death of hope, in which Capitalist Surrealism, our phenomenological experience of the Capitalist Real, is born. While this Surrealist stage is both uncomfortable and has deleterious effects on the human condition, it represents the chink in the armour of banality and inertia, and the diminishing politics of the powerful. The sense that anything, absolutely *anything,* can happen to you, is both incredibly terrifying, and when looked at squarely, an opportunity for radical freedom.

It is this radical freedom that we see ourselves invited to in the many facets of human expression and convention which have experienced an awakening of new consciousness (or the restoration of old ones. Beliefs, ways of interacting with the world, and surviving are no longer benefited by or even neutrally treated by their operating environment anymore; if the complete weight of propaganda in circulation at the moment could be translated into sound, it would present an impenetrable and unlistenable wall.

It is that environment that individual ideologies not sanctioned by the operating environment have struggled against; all of them now have new life and vigor because despite that wall, and the spectacle societies which generate them, the literal truth of material impacts trump all prior arguments. With awareness of most likely outcomes of the climate crisis on a sliding scale, we see radicalization and existential depression of all varieties spike; the answers they attempt to generate to these apparent conditions lack hope in broad but uneven spikes along that scale of awareness, with the suicidally depressed expert climatologist and the radical anarcho-primitivist sharing the same ontological space in orientation to that crisis.

This project, among other things, is an attempt to generate an alternative answer (what that project consists of is entirely based in literature and mutual aid, the oldest Christian platforms for emancipatory action.) Terms like Solarpunk and Cloud City Futures approach but fail to capture the spirit of an alternative answer, mostly with an appeal to the world of aesthetics, a dubious method for summoning change at best. Terminology alone, or even in tandem with education, is also not sufficient; the noise environment they enter into immediately drowns out the creators meaning, especially if these terms are successful and gain currency with the wealthy.

Rather, we must articulate the positive from all our apparent negatives: The apocalyptic futures we anticipate cannot begin actually describe the terrain of the future, and the apparancy of our material conditions impact on our lives is now drowning out the sound of the standing ideologies. This is a brave time, where people blaze trails for others to follow out of the collapsing structures of the past and into the dwelling places of the new future. Our experience of reality, though surreal, has now unlocked an awareness of an apparent power: making meaning.

It is with the tools of meaning-making that these, who are the heirs of their elders, queer and colour revolutionary and indigenous land defender and abolitionist, pioneer the hopeful vistas of the future. It is necessary that they *be* hopeful; it was the Buddha who taught that people deceived by Samsara may be “deceived” by the apparent gifts of pursuing enlightenment, the majority of which are ancillary incidentals not to be meditated on. The king calls his indolent heirs out of the burning palace with a promise of gifts; when they arrive, they protest the lack of gifts, but it is in his embrace of them we realize they are the gift, and their survival was worth the promise of chariots and ponies.

But there must also be chariots, and ponies; luxuries, and finery; the grim tools of “defense” and all the things the human animal finds comforting in their resting environment to assure them of its stability. In the Dao De Jing, (Though Mueller butchers the poetry,) the Sage articulates this and describes how to create it: “Let there be a small country with few people,

Who, even having much machinery, don't use it.

Who take death seriously and don't wander far away.

Even though they have boats and carriages, they never ride in them.

Having armor and weapons, they never go to war.

Let them return to measurement by tying knots in rope.

Sweeten their food, give them nice clothes, a peaceful abode and a relaxed life.

Even though the next country can be seen and its doges and chickens can be heard,

The people will grow old and die without visiting each other's land.” A.C. Mueller Translation, The Dao De Jing, Attributed to Lao Tzu

It is as naked an appeal to a return to the life of the community and the village as can be found. A return to idigenous ways of being, which speaks to the preservation of folk ways, while the reality that the sage is administering them (even if only by moral teaching) shows a potential for new ideas to be instanced; innovation is not a property innate to the colonizing and walled world, and memetic culture and the society of truth-telling through representation around it reflect callbacks to this desire. The political movement around Land Back, while perennial to the causes of indigenous people, crystalizes an actionable answer for individuals and collectives to support. Its cousins in other colour movements, many of them representing indigenous people displaced by imperialism in the first place, are also generative of positive futures; it is a fact of history that as the rights of people classified as “minorities” are raised, the general quality of life for all in society rises, with the exception of those who could never be touched but by the highest tides.

These movements and moments of consciousness are their own inestimable goods, not mere ends for the would be conscious person to hijack for their goals. This is in fact a position inimical to the success of any of these movements; grifting starts at home, and it is the white leftist who is more easily conquered by the white liberal, since neither of them have conquered their own whiteness in the first place. But that supporting them generates positive benefits for all can only be argued against if you value the lives and comforts of some over others; those who value the general benefit first can see a clear path.

It is that clarity that gives meaning makers license to create the vistas of the future. It is the “Mandate of Heaven” that endorses the artists, a general operating license to create. Because the material impact of the present is louder than the noise of Capital, there an outburst of fertility and growth, the very seeds of hope, breaking out in the midst of this Surrealism. It is with the tools of meaning making, and the canvas of the crisis, that people escape the real.

4 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Agent provocateurs on the government payroll supplied explosives to Panther members and sought to incite them to blow up public buildings, and they promoted kangaroo courts encouraging Party members to torture suspected informants.

BLACK AGAINST EMPIRE: THE HISTORY AND POLITICS OF THE BLACK PANTHER PARTY, Joshua Bloom & Waldo E. Martin Jr.

I implore y’all to read this book. Nothing has changed.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

subcrit note,

Redguards are an interesting example of how the lore has changed throughout the games.

Arena establishes the character of Hammerfell and the Redguards with this paragraph:

Thy race is a people without a past, for in the Tiber War thou wert stalwart guardians of Hammerfell. As time moved on thy people held onto the ground for which they had shed tears of blood, and now the land, and the strength and endurance of rock itself, is thine own to command…

So from the start they are victims of imperialist aggression, which is a thread that TESA:Redguard obviously takes up. There wasn’t any Yokuda in Arena lore, so Hammerfell is the “ground for which they had shed tears of blood”. With Orcs not being playable, the Redguards stand in as the best physically defensive race, with bonuses to agility and endurance, and so their homeland and story reflects that.

Something that this paragraph highlights is how “time [has] moved on” from the days of the “Tiber war”, which is not always the feeling you get from the other Third Era games, which often centre around institutions that were set up in the early days of the Third Era and have endured since. Another oddity that could be reinterpreted in the light of current lore is the phrase “people without a past”, considering the use of Numidium in the Tiber war.

That’s about the full extent of Redguard lore in Arena. There’s the names and greetings of various towns but they don’t tell you much more than the initial paragraph: Redguards are a proud martial culture from a desert land.

In TESII:Daggerfall the lore of Redguards was expanded considerably to include Yokuda, its culture, and how the settlers of Hammerfell only represent an offshoot of it.

Something that’s interesting is that there are references to the settlement of Hammerfell by the Ansei culture but no record of Redguard battles until the Siege of Orsinium. The idea of Yokudans as a conquering force upon western Tamriel didn’t exist. Instead “their land was enemy enough to keep their population checked” (A History of Daggerfall). I don’t think that the disappearance of the Dwarves had a date established by Daggerfall so it’s even possible that the Redguards could have directly succeeded, or even coexisted with, the remaining Rourken Dwarves in speculation upon the lore of that time (although popular history e.g. King Edward states that the “goblins” drove the Dwarves out of Hammerfell prior to the arrival of the Redguards).

Redguard antipathy to the Empire is generally preserved in Daggerfall lore through the ongoing struggles between Hammerfell and kingdoms of High Rock (allied with the Empire at the time of the War of Betony), as well as the implication that some Redguards joined with the Camoran Usurper’s conquests voluntarily. Some Redguards rank in Imperial-founded institutions like the Mages Guild, and as far as I know no Redguards are particularly vocal about distaste for the Empire. There’s some lore which indicates cultural distance of Hammerfell from Cyrodiil:

There were few Redguards who had been to the Imperial Province at the time [3e39], and it may be that he [Destri] took the last name Melarg in order to assimiliate with the Breton, Nordic, and Dark Elf cultures he encountered there. (Notes For Redguard History)

Note however that Akorithi, queen of Sentinel, claims to be the most loyal representative of the Empire in the region (although only says this to the player to gain control of the totem).

That’s most of what Daggerfall has on the Redguards. And I would say none of it goes against what little Arena establishes, but arguably changes the emphasis. The diversity of Yokudan culture and elements of it that continue in Hammerfell are obviously welcome.

TESL:Battlespire doesn’t have any Redguard lore. Skipping that, TESA:Redguard is generally thought of as the turning point of the lore towards Morrowind, with the Pocket Guide to the Empire. It makes LOTS of changes from Daggerfall. Given that the focus of the story of Redguard is conflict between the early Septim Empire and Hammerfell, obviously a good chunk of its lore changes relate to that. Much of what PGE has to say on Hammerfell and the Redguards is intentionally biased against them, which is in keeping with Arenalore Hammerfell’s spirited defence against the burgeoning Empire.

The most relevant changes are summarized in the opening paragraphs of the PGE on Hammerfell (note that the elven scribe YR does not object to any of the claims here):

Some three thousand years ago the continent of Yokuda suffered a cataclysm that sunk most of it into the sea, driving its people towards Tamriel. The bulk of these refugees landed at the uninhabited isle of Herne, while the rest continued on to the mainland. This vanguard “warrior wave” of Yokudans, the Ra Gada, swept into the country, quickly slaughtering and enslaving the beastfolk and Nedic villagers before them, bloodily paving the way for their people who waited at Herne, including the Na-Totambu, their kings and ruling bodies. The fierce Ra Gada became, phonetically, the Redguards, a name that has since spread to designate the Tamrielic-Yokudan race in general. They ultimately displaced the Nedic peoples, for their own agriculture and society was better organized and better adapted to Hammerfell’s harsh environment. They took much of Nedic custom, religion, and language for themselves in the process, and eventual contact with the surrounding Breton tribes and Colovian Cyrodilics hastened their own assimilation into the larger Tamrielic theater. Yoku, the Redguard oral language, was almost entirely replaced as the need for foreign commerce and treaties increased.

Under the provincial organization of the Second Empire, two Redguard “parties” formed to aid Cyrodiil’s administration of Hammerfell. [Crowns and Forebears]

In short, this establishes a (apparently) non-political reason for the exodus of Yokuda, a war of settlement of Hammerfell (more of a massacre), rewrites present Redguard culture and language as essentially Nedic in origin, and introduces the Crowns and Forebears.

The colonization of Hammerfell in post-Redguard lore is particularly interesting. You could easily see it as the frustrating fantasy trope of a presently oppressed race that is in fact reviled (almost in retribution) for a previous act of violence. When this idea appears in other stories it has been criticized for minimizing or justifying racial oppression. It is presumably based in a complete lack of knowledge of imperialism: violence is dealt out to balance historical violence, and the world is just. That rationalization is difficult to fully see through here, as the Empire is most definitely the antagonist in Redguard and yet it is the author, not the Empire, who brings into existence the slaughter of the indigenes by the Yokudans as a justification for the present state of affairs.

To shed more light on this, there’s an MK forum quote on Redguard’s changes to the Yokudans:

[…] when I started writing Redguard I really thought about how unique the black people of Tamriel were: they came in and kicked ass and slaughtered the indigenes while doing so. They invaded. It was the first time I had encountered the idea of “black imperialism”…and it struck me big time, as something 1) new, 2) potentially dangerous if taken as commentary, and 3) potentially rad if taken as commentary.

(Worth noting, incidentally, that from Daggerfall to Redguard the Redguards change to definitely Black from previously somewhat swarthy Iberians)

So Kirkbride believes that, contrary to erasing and disarming the Hammerfell-Septim conflict as an examination of imperialism, the Yoku invasion is a step forward (both “dangerous” and “rad”) in the lore.

Taking the above quote in its immediate context, MK appears to be making the honest mistake of conflating imperialism (hypothetical “black imperialism” notwithstanding) with the ethos of the Black Panthers, seemingly oblivious to the subtle point that the Panthers and imperialism are obviously completely opposite things.

Anyway to cut a long story short this is the Redguard narrative that has largely been preserved in recent games (while Morrowind doesn’t have much contemporary Redguard lore, and Oblivion seemingly only portrays Redguards who happen to be loyal to the Empire, in the second and fourth eras things are more gritty). They are the fearsome people from foreign lands who cut a bloody swathe through elf and nede-man alike, and who must now be held at arm’s length as their proud martial culture makes them incompatible with the civilized west (or, mainland).

I’m not going to go much into the difficulties of the purely aesthetic changes to Redguard culture in lore, saving to note that: (as this post summarizes) how convenient that they serve as cipher for all the enemies of IRL imperium in one.

TLDR:

MK bad and racist, Arena best TES game

149 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi there! I'm wondering if you could recommend some books about the communism wave during the 70s, Europe, America, Asia, wherever's fine with me. I want to learn more about how the world went from 70s during which leftwing movements were quite prevalent, and turned to more conservative right-oriented since 90s. (Ugh, I don't even know if this statement is correct) Thanks a lot!

Hello dear comrade!

One book I would highly recommend is “Chile’s 1,000 Days of Revolution: Communist Assessments of the Allende years.” Basically it’s 9 chapter book detailing and defending the policies of Allende and defends his legacy after much slander by the Western Media. This is one of my favorites and I’ve had it in my library for quite some time.

Another book I would recommend for you is “Open Veins of Latin America: Five Centuries of the Pillage of a Continent” by Eduardo Galeano, which basically details all of the conquests and the terror that was put upon the indigenous people of Lain America from the age of the Spanish Invasion to U.S. meddling and staging coups. If you want a well rounded picture of why Latin America is so unstable today, this is where you want to look.

The third book I would recommend about the communist wave of the 70s would be Black against Empire: The History and Politics of the Black Panther Party” by Joshua Bloom. You see, the Black Panther Party is still a very polarizing group even in America today, and this book is one of the few that comes close to not taking sides and evaluating their values and tactics in an impartial manner.

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

IN THESE TIMES

With the popularity of politicians like Bernie Sanders and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and the explosion in membership in the Democratic Socialists of America (DSA), socialism is all of a sudden central to the national political conversation. And it's happening in the United States. Despite being a country long argued to be uniquely allergic to all talk of class conflict and any alternative to capitalism, here we are, watching many Americans question whether we should remake our political and economic systems from top to bottom.

But this isn't the first time mass numbers of people in the United States have considered socialism. The last time was half a century ago, when the New Left raised questions about capitalism, imperialism, racism, sexism and much more. At the tail end of the 1960s, those questions were taken up by the New Communist Movement (NCM), a collection of groups in the Marxist-Leninist tradition. While the movement was made up of organizations that had different answers to burning political questions, on the whole, these groups were inspired by the left-nationalist projects of the day, including domestic movements like the Black Panthers and Puerto Rican nationalist groups, and international communist movements in Cuba, Vietnam, and especially China.

Max Elbaum was deeply involved in that movement. After joining Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) as a college student in Madison, Wisconsin, Elbaum co-founded the NCM group Line of March. He ended up devoting his life to various movements against war and racism, and served as the editor of the leftist magazine CrossRoads throughout the 1990s.

Elbaum is the author of Revolution in the Air: Sixties Radicals Turn to Lenin, Che, and Mao, reissued in April by Verso Books with a new foreword by Alicia Garza, cofounder of #BlackLivesMatter. Though he was a participant in some of the organizations and campaigns and the overall movement that he chronicles in the book, Revolution in the Air takes a more dispassionate look at the NCM, fairly weighing its achievements and missteps.

It's hard to come away from reading Elbaum's book without thinking that the movement made far more missteps than achievements. As we explore in our conversation below, the movement's orientation towards “Third-World Marxists” and left nationalism gave it some redeeming characteristics, like its steadfast commitment to anti-racism and creating a multiracial movement. But it also quickly became a movement rife with undemocratic behavior, obsessed with doctrinal purity, and orientated towards regimes like China that radicals later realized were far from successful democratic, socialist societies.

This is a history that's worth excavating in its own right, given how significant the NCM was at the tail end of the New Left. But it is also history that radicals today would do well to wrestle with. Socialists in the 21st century don't have to completely reinvent the wheel — they can learn from the often-heroic efforts of radicals several decades ago. Revolution in the Air is essential reading for the new generation of radicals that wants to get anti-capitalism right this time, avoiding the same sectarian, undemocratic, purity-obsessed mistakes that the past generation of Marxist-Leninists did.

I recently interviewed Elbaum about his book. Our conversation focused on the history of the NCM and—especially—what it can teach members of the DSA.

Micah Uetricht: Let’s start with the basics. What was the NCM?

Max Elbaum: The NCM was an effort by several thousand people to revitalize communism, during a period when traditional communism had been stagnant. It evolved out of the radical movements of the 1960s and had some momentum on the left from the late 1960s into the 1970s. At that point, it was the predominant trend within the Left. It had the highest proportion of people of color and some influential political initiative.

It ran into difficulties into the mid- to late-1970s. Some parts carried on into the 1980s, but was finished as a coherent force by the late 1980s.

Micah Uetricht: What was meant by “communism”?

Max Elbaum: The movement arose at a time when Third-World revolutions were shaking the empire, and when several of the leading organizations within those revolutions identified with Marxism-Leninism — versions of it that were not strictly within the ideological niche of the Soviet Union, particularly the Chinese Communist Party and the Cubans. The NCM identified with those movements politically and ideologically, and defined itself as building a genuinely revolutionary party as opposed to what it saw as “reformism” or “revisionism��� of the Communist Party USA.

The idea was to build a new revolutionary vanguard on the basis of a more orthodox, left version of Marxism-Leninism, one especially inspired by the liberation movements then existing throughout what we called the Third World.

Micah Uetricht: Why was the NCM so ascendent in the post-New Left?

Max Elbaum: It attracted a plurality of people who turned to revolutionary politics — not necessarily a majority, but a plurality. It was particularly strong in freedom movements from communities of color among those who turned to revolutionary politics. People who went into it had an extremely strong commitment to revolutionary politics and made sustained efforts to sink roots in the working class and oppressed communities.

The largest left newspaper of the time, the Guardian, embraced these politics. It was a time when the Chinese, Vietnamese and Cuban Communist parties and other left-led national liberation movements had very high prestige, and this movement identified with those forces. All of this gave the movement initiative.

Micah Uetricht: Your book isn’t really a defense of the NCM. Most of it is quite critical. But you also repeatedly point out some of the positive features of that movement. Can you briefly sketch out the good and the bad from those movements?

Max Elbaum: My book is an effort to document what the movement did and thought and what its components and parts were. So in a sense, it’s resource material for people to draw their own conclusions of what the strengths and weaknesses were. (Though I do, at the end, draw my own balance sheet.)

For my part, on the positive side, the movement did see how central empire-building and racism were to U.S. capitalism. There was a strong commitment to sinking roots in those communities that had the greatest potential to make radical change. The movement grasped the importance of collective action and the idea of people prioritizing political activity and advancing it in a collective way.

The movement did make some headway in breaking out of a U.S.-centric view of the world. And there was an attempt to learn from and offer ideas to revolutionaries in other countries, and a strong sense of internationalism. In its early years, certain component parts did some interesting work on U.S. politics, especially on the particular role of the special oppression of communities of color.

On the negative side, all sides of the movement were afflicted with a misassessment of the conditions in the country, especially the resilience of capitalism. Lots of people were off-base in the late 1960s and 1970s, but the movement couldn’t adjust when it became clear that the motion of national politics was moving to the right.

The ideological frameworks of the different component parts of the movement were rigid in their quest for orthodoxy — seeing Marxism-Leninism as a kind of omniscient science. Those ideological frameworks were off-base.

The movement was generally afflicted by ultra-left tendencies and a tendency to polarize forces that weren’t, in their view, as revolutionary as them. The model of organization the movement implemented was “miniaturized Leninism”; we essentially built small sects instead of flexible, mass revolutionary groups. This was related to our misassement of the historical conditions. There was a proliferation of sectarian attitudes over political differences, some of which were important but many weren’t.

(Continue Reading)

#politics#the left#in these times#bernie sanders#alexandria ocasio cortez#history#socialism#democratic socialism#DSA#Democratic Socialists of America

47 notes

·

View notes

Link

Goldner on Elbaum

Commune has a new review out of the 2018 reissue of Max Elbaum’s Revolution in the Air, which recounts the trials and travails of the New Communist Movement in the US. Written by Colleen Lye, “Maoism in the Air” is very sympathetic to the book’s central thesis: namely, that three distinct strands of American Maoism (Cultural Revolutionary, Third World nationalism, and orthodox Marxism-Leninism) shaped the politics of the post-’68 generation in a novel and generally beneficial way. Lye even goes a step further than Elbaum, remarking on the NCM’s institutional legacy that “today’s academic field of critical ethnic studies might well be described as a space where anti-racism and anti-imperialism continue, in a different key and perhaps even unknowingly, the Marxist-Leninism of the ’68 generation.”

She may well be right about this, but I hardly think this is a legacy to be proud of. Usually the so-called “long march through the institutions” is seen as a political defeat held up as an intellectual victory. Marxism’s relegation to the academy is a sign of its neutralization, in other words. I can only speak to the field of Jewish Studies, which is what I’m most familiar with, but for the most part I find it a useless discipline — despite my persistent interest in the history of Jews. Regardless, I was somewhat surprised to see such a positive review of Elbaum’s book in the pages of Commune, a magazine that I am very excited about. (For any readers who haven’t already, I encourage you to check out Jay Firestone’s ethnographic survey of alt-Right NYC and Paul Mattick’s outstanding piece on the centenary of the German Revolution.)

Admittedly, I’ve never understood the appeal of Maoism for American communists, either in the seventies or today. Perhaps it possessed some exotic aura back then, or was maybe just a dope aesthetic. Either way, the theory and practice of the Chinese brand of Stalinism ought to have been long discredited by now. Virtually all of the national liberation movements that were supposed to destabilize global capitalism and pave the way for international socialist revolution have been seamlessly reintegrated into the world of commodities. Nowadays, of course, there is the added association of Maoist ideas with the Black Panther Party, which is still celebrated as a high point in the history of revolutionary politics in the US. How much of this is simply mythologization after the fact is difficult to say, but it was certainly influential.

But even in light of this association, the attraction of Maoism is difficult to grasp. It was recently revealed, in fact, that the person who introduced the Black Panthers to the writings of Mao was an FBI snitch. Richard Aoki, the Berkeley radical and leader of the ethnic studies strike, informed his Bureau contact: “The Maoist twist, I kind of threw that one in. I said so far the most advanced Marxists I have run across are the Maoists in China.” Despite this ideological straightjacket, BPP spokesmen like Fred Hampton were able to say fairly interesting things (all this before he was gunned down in Chicago at the age of 21). While it gave Hampton the perspective he needed to denounce the empty culturalism of Stokely Carmichael, whom he referred to as a “mini-fascist,” it otherwise limited the Panthers’ scope of inquiry into capitalist society.

Loren Goldner’s review, lightly edited and reproduced below, provides a much-needed corrective to the laudatory reception Revolution in the Air has met with so far. Goldner grounds his critique of Elbaum in the left communist and heterodox Trotskyist tradition he belonged to at the time, even though he likewise went to Berkeley and knew many of the same characters. Other Maoists, such as Paul Saba, have gently criticized Elbaum’s book over the last few months. Saba contends that the main fault of the NCM — of which he was also a veteran — was its theoretical poverty, and that it might have benefited from a more sophisticated Althusserian-Bettelheimian viewpoint. Quite the opposite holds for Goldner: the New Communist Movement was wrongheaded from the start.

You can read a 2010 interview with Elbaum by clicking on the link, but otherwise enjoy Goldner’s blistering review. Maoism may still be “in the air,” as Lye contends, if the various Red Guard formations are any indication. According to Goldner, however, it might be in the air the same way smog and other pathogens are.

Without exactly setting out to do so, Max Elbaum in his book Revolution In The Air, has managed to demonstrate the existence of progress in human history, namely in the decline and disappearance of the grotesque Stalinist/Maoist/“Third World Marxist” and Marxist-Leninist groups and ideologies he presents, under the rubric New Communist Movement, as the creations of pretty much the “best and the brightest” coming out of the American 1960s.

Who controls the past, Orwell said, controls the future. Read at a certain level, Elbaum’s book (describing a mental universe that in many respects out-Orwells Orwell), aims, through extended self-criticism, to jettison 99% of what “Third World Marxism” stood for in its 1970s heyday, in order to salvage the 1% of further muddled “progressive politics” for the future, particularly where the Democratic Party and the unions are concerned, preparing “progressive” forces to paint a new face on the capitalist system after the neoliberal phase has shot its bolt.