#anterior cingulate cortex

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Problem-Solving and Decision-Making: A Process-Driven Approach to Mastery

Since when I was a kid, think 5 years old, I discovered that I excelled in both problem-solving and decision-making. Later in life, I became aware that they also are fundamental to our human experience, shaping our lives, careers, and relationships. Photo by Andrea Piacquadio on Pexels.com They are often seen as skills one either possesses or lacks. However, a process-driven perspective reveals…

View On WordPress

#2-Minute Rule#5 Whys#anterior cingulate cortex#awareness#bias#Buddhism#buddhist wisdom#Continuous Improvement#convergent thinking#creative thinking#decision matrix#decision-making#default mode network#Dichotomy of Control#divergent thinking#DMN#Dopamine#dopaminergic system#Growth#hippocampus#insight#learning#logical analysis#logos#Madhyamaka#Middle Way#Neuroscience#non-attachment#prefrontal cortex#premeditatio malorum

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Another round of dehumanizing bigots, let’s go!

Did you know that those who are unable to comprehend people that are different from them are literally biologically underdeveloped? Yup!

So empathy— it’s an important process that humans develop as they mature and age. Humans. Develop it. We develop it because we’re a social species, and with intelligence comes cooperation, altruism, and the ability to accept one another.

When biology fails, and the brain’s anterior insula, anterior cingulate, or prefrontal cortex are unable to properly form, then it becomes impossible for the brain to properly process or emulate empathy in any form. It also affects other things such as emotional regulation, ability to retain new information, and impulsivity.

This is why bigots are more akin to chimps than humans— they lack emotional regulation (which explains why they scream any time someone is different from them), they can’t empathize at all (leading to them being violent in both words and actions), and they can’t properly internalize new information (which is why they reject science and just… continue screaming like monkeys).

All this is not to say we should feel bad for these unevolved and underdeveloped human-appearing creatures. I don’t even see them as human, which is fair given how they don’t see actual humans as humans.

No tears are shed when a monkey becomes just smart enough to realize it should end its own life, and acts on it. So if you’re a bigot, rub those braincells together and see if you can’t come to the same conclusion. :)

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Human Beings are Hardwired for Consciousness.

Did you know the part of your brain we think Consciousness comes from is called the 'Rostral Anterior Cingulate Cortex' that plays a key role in experiencing of emotions,..... and reward-based decision-making and learning, including motivation, cost-benefit calculation, as well as conflict and error monitoring.

It also determines whether our future will be one of clear-blue skies or dark stormy clouds.

This is because Optimism and Pessimism are not hardwired in our brain, and we as the Gods we are determine if we use cognitive behavioral techniques to overcome our natural tendencies towards doom and gloom.

So what do you think you want to do, dwell on mistakes of the past and continue to pick at the scab, or do you make a fresh start, and leave your mistakes in the past where they really belong?

Because we do know our lives are better when we choose Optimism, and that's where consciousness comes into play, because it is hardwired in our brain, we just have to realize it is we who are the God, and we make all of the decisions in our livelihood, not anything outside of ourselves like the Gods man creates to make us think THEY are in charge, because they aren't, we are.

But as I've said those choices aren't Hardwired in our brains, and we can choose to let religions God make all of our decisions for us.

Or we can choose to follow our heart, through your brains consciousness,.... the choice is entirely up to YOU!

0 notes

Text

Covertly Focus

Covert hypnosis is always fun for me, I never get TIRED of it, in fact I'd say it's one of my favorite methods of taking a subby little mind like your deeper, and it's so easy to allow it to happen, the mind going deep without you even realizing it's happening. Like right now as I write this little blurb in my blog, you find yourself feeling SLEEPY and OPEN as you know, when I write one of these little messages for you to read, imagining you reading the words and not paying very much attention, RELAXING in your chair. Hypnosis has been practiced for centuries and traces its origins to ancient Egypt and Greece. Priests and shamans often used trance-like states in their rituals. it's easy to see how the process works, words are powerful, words like FOCUS when you see the word FOCUS, and your focus increases. It is just a regular conversation, a little ONE sided since I'm the only one communicating and all you are doing is reading, relaxing and feeling the words, but part of your mind hears the words you are reading as you FOCUS more on each word. It's like you hear my soft feminine voice in your mind as you read, and suddenly little words I use like relax, sleepy, tired, focus.... and so many others, just trigger a need inside your subconscious, after all, you love focusing on my words as I write about how covert hypnosis can just appear out of the blue. Unaware that the triggers I use are making your mind fuzzy and BLANK. Hypnosis affects brain regions like the anterior cingulate cortex and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, which are related to attention and control. I love how sometimes just talking and the other person seems to fade out a bit, at least from a conversational standpoint. I think that is when they are ultra receptive to suggestions, however attractive they might seem, bordering on covert hypnotic addiction. Thinking you LOVE to do drawn to the word covert somehow. you feel it on a different level, a deeper level, and I know contrary to some depictions in media, hypnosis can't force someone to act against their will or moral code. It's more about enhanced suggestibility and focus, but whose to say deep inside you don't want this, need this, love this feeling of letting go of control. isn't that right toy?

#covert hypnosis#hypnosis#hypnotic#brainwash#hypno sub#controlled#hypnotism#mind control#bimbo doll#bimbo goddess#bimbo dreams#covert narcissism#covert#cover art#bambi doll#bambi sleep#bambification#bimb0fication#bambi hypno

276 notes

·

View notes

Text

People say it’s no biological advantages for women which is false, women have better buoyancy in water, women fight off infection and diseases also viruses off better than men, Women are better at surviving lower temperatures than men, women generally outperform men in olfactory abilities, and Women tend to have a better memory, as well as having a more active anterior cingulate cortex (the part of the brain associated with decision making, impulse control, emotions, etc.)

women have better lower center gravity than women, Lower center of gravity does make you harder to knock over.

Women generally outperformed men on auditory memory

Women's brains are wired to process visual information from a wider field of view, giving them a broader awareness of their environment.

women have a larger color vocabulary—think periwinkle, azure, and other color names that are unlikely to be used by men

Females have more type 1 fibers, associated with greater endurance. Estrogen has anti-inflammatories properties and protects the joints more, and due to reduced body muscles, girls need less oxygen to function (less oxygen=less bio waste as well). So yes women and the female body in general is not weak nor weaker.

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

Also preserved in our archive

"Just a cold" that changes the structure and mass of your brain

By Nikhil Prasad

Medical News: A groundbreaking study from researchers at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA)-USA has shed light on how Long COVID is linked to structural changes in the brain caused by SARS-CoV-2. By using advanced imaging techniques, the team discovered structural changes in the brains of individuals with Long COVID, including increased cortical thickness and gray matter volume in specific regions. This Medical News report will explore the study's key findings, its implications for understanding Long COVID, and what it means for patients suffering from this persistent condition.

Understanding the Research Approach The study involved participants from the UCLA hospital and broader Los Angeles community, with 36 individuals ranging in age from 20 to 67. Among them, 15 had Long COVID symptoms, while others were used as healthy controls. Researchers utilized structural magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to compare brain differences between these groups. The study focused on specific brain regions, such as the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) and the cingulate gyrus, which are known to be involved in cognitive and emotional processes. These areas were chosen because they are susceptible to inflammation and have been linked to neuropsychiatric symptoms.

To assess participants' cognitive and emotional health, tools like the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) and the Hamilton Anxiety and Depression scales were used. The imaging data were processed using specialized software to measure cortical thickness and gray matter volume, providing a detailed look at the brain's structural changes.

Key Study Findings The study revealed several critical findings that deepen our understanding of Long COVID's impact on the brain. Participants with Long COVID showed:

-Increased Cortical Thickness: Regions such as the caudal anterior cingulate, posterior cingulate, and rostral middle frontal gyrus exhibited significantly higher cortical thickness compared to controls.

-Higher Gray Matter Volume: In areas like the posterior and isthmus cingulate gyri, Long COVID patients had greater gray matter volume.

Interestingly, these structural changes were associated with the severity of clinical symptoms. For example, higher thickness in the cingulate regions correlated with more severe chronic illness scores, while increased insular thickness was linked to anxiety levels.

Such changes suggest that Long COVID might lead to either swelling due to inflammation or compensatory mechanisms like neurogenesis to counteract damage.

How This Study Compares with Previous Research While most COVID-19-related brain studies have shown reductions in gray matter and cortical thickness, this research indicates an increase in these metrics for Long COVID pa tients. Prior studies focused on acute COVID cases often revealed brain shrinkage and cognitive decline. In contrast, this study highlights that Long COVID might involve unique mechanisms, such as prolonged inflammation or a compensatory response to earlier damage.

Implications for Patients and Healthcare Providers These findings are crucial for both patients and healthcare professionals. They suggest that the persistent symptoms of Long COVID, such as brain fog, fatigue, and anxiety, could have a physical basis in brain structure changes. Recognizing this connection can lead to better-targeted treatments and interventions.

The Future of Long COVID Research While this study offers valuable insights, it also leaves many questions unanswered. For example, are these brain changes reversible? Do they worsen over time? The researchers acknowledge the study's limitations, including its small sample size and lack of longitudinal data. Future studies should aim to include larger, more diverse populations and examine changes over time to build a clearer picture of Long COVID's effects.

Conclusions This research from UCLA represents a significant step forward in understanding the neurological impacts of Long COVID. The observed increases in cortical thickness and gray matter volume in certain brain regions provide strong evidence that Long COVID involves measurable structural brain changes. These findings offer hope that by identifying the physical manifestations of this condition, we can develop more effective treatments to alleviate its symptoms. However, the path forward requires continued research to uncover the full extent of these changes and their implications.

The study emphasizes the importance of addressing neuropsychiatric symptoms in Long COVID patients and highlights the need for comprehensive care that includes both physical and mental health support. As we move forward, it is vital to integrate these insights into public health strategies to help those affected by this debilitating condition.

The study findings were published in the peer-reviewed journal: Frontiers in Psychiatry. www.frontiersin.org/journals/psychiatry/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2024.1412020/full

#mask up#public health#wear a mask#pandemic#wear a respirator#covid#covid 19#still coviding#coronavirus#sars cov 2#long covid#covid is not over

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

Interesting Papers for Week 44, 2024

The role of the human hippocampus in decision-making under uncertainty. Attaallah, B., Petitet, P., Zambellas, R., Toniolo, S., Maio, M. R., Ganse-Dumrath, A., … Husain, M. (2024). Nature Human Behaviour, 8(7), 1366–1382.

Modeling hippocampal spatial cells in rodents navigating in 3D environments. Aziz, A., Patil, B. K., Lakshmikanth, K., Sreeharsha, P. S. S., Mukhopadhyay, A., & Chakravarthy, V. S. (2024). Scientific Reports, 14, 16714.

Anterior cingulate cortex provides the neural substrates for feedback-driven iteration of decision and value representation. Chen, W., Liang, J., Wu, Q., & Han, Y. (2024). Nature Communications, 15, 6020.

Firing rate adaptation affords place cell theta sweeps, phase precession, and procession. Chu, T., Ji, Z., Zuo, J., Mi, Y., Zhang, W., Huang, T., … Wu, S. (2024). eLife, 12, e87055.4.

Non-Hebbian plasticity transforms transient experiences into lasting memories. Faress, I., Khalil, V., Hou, W.-H., Moreno, A., Andersen, N., Fonseca, R., … Nabavi, S. (2024). eLife, 12, e91421.3.

Gaze-centered gating, reactivation, and reevaluation of economic value in orbitofrontal cortex. Ferro, D., Cash-Padgett, T., Wang, M. Z., Hayden, B. Y., & Moreno-Bote, R. (2024). Nature Communications, 15, 6163.

Modulation of alpha oscillations by attention is predicted by hemispheric asymmetry of subcortical regions. Ghafari, T., Mazzetti, C., Garner, K., Gutteling, T., & Jensen, O. (2024). eLife, 12, e91650.3.

Contributions of cortical neuron firing patterns, synaptic connectivity, and plasticity to task performance. Insanally, M. N., Albanna, B. F., Toth, J., DePasquale, B., Fadaei, S. S., Gupta, T., … Froemke, R. C. (2024). Nature Communications, 15, 6023.

Consequences of eye movements for spatial selectivity. Intoy, J., Li, Y. H., Bowers, N. R., Victor, J. D., Poletti, M., & Rucci, M. (2024). Current Biology, 34(14), 3265-3272.e4.

Prediction error determines how memories are organized in the brain. Kennedy, N. G., Lee, J. C., Killcross, S., Westbrook, R. F., & Holmes, N. M. (2024). eLife, 13, e95849.3.

Neural Representation of Valenced and Generic Probability and Uncertainty. Kim, J.-C., Hellrung, L., Grueschow, M., Nebe, S., Nagy, Z., & Tobler, P. N. (2024). Journal of Neuroscience, 44(30), e0195242024.

Selective consolidation of learning and memory via recall-gated plasticity. Lindsey, J. W., & Litwin-Kumar, A. (2024). eLife, 12, e90793.3.

A synergistic workspace for human consciousness revealed by Integrated Information Decomposition. Luppi, A. I., Mediano, P. A., Rosas, F. E., Allanson, J., Pickard, J., Carhart-Harris, R. L., … Stamatakis, E. A. (2024). eLife, 12, e88173.4.

Memorability shapes perceived time (and vice versa). Ma, A. C., Cameron, A. D., & Wiener, M. (2024). Nature Human Behaviour, 8(7), 1296–1308.

Mixed Representations of Sound and Action in the Auditory Midbrain. Quass, G. L., Rogalla, M. M., Ford, A. N., & Apostolides, P. F. (2024). Journal of Neuroscience, 44(30), e1831232024.

Neural activity ramps in frontal cortex signal extended motivation during learning. Regalado, J. M., Corredera Asensio, A., Haunold, T., Toader, A. C., Li, Y. R., Neal, L. A., & Rajasethupathy, P. (2024). eLife, 13, e93983.3.

Using synchronized brain rhythms to bias memory-guided decisions. Stout, J. J., George, A. E., Kim, S., Hallock, H. L., & Griffin, A. L. (2024). eLife, 12, e92033.3.

Cortical plasticity is associated with blood–brain barrier modulation. Swissa, E., Monsonego, U., Yang, L. T., Schori, L., Kamintsky, L., Mirloo, S., … Friedman, A. (2024). eLife, 12, e89611.4.

Structural and sequential regularities modulate phrase-rate neural tracking. Zhao, J., Martin, A. E., & Coopmans, C. W. (2024). Scientific Reports, 14, 16603.

An allocentric human odometer for perceiving distances on the ground plane. Zhou, L., Wei, W., Ooi, T. L., & He, Z. J. (2024). eLife, 12, e88095.3.

#neuroscience#science#research#brain science#scientific publications#cognitive science#neurobiology#cognition#psychophysics#neurons#neural computation#neural networks#computational neuroscience

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

just read an article explaining an observation in the brain function differences between a study of some conservatives and liberals. it says conservatives desire security, predictability and authority more than liberals do, and liberals are more comfortable with novelty, nuance and complexity.

the volume of gray matter, or neural cell bodies, making up the anterior cingulate cortex, an area that helps detect errors and resolve conflicts, tends to be larger in liberals

and the amygdala, which is important for regulating emotions and evaluating threats, is larger in conservatives. makes so much sense.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Doing It for the High

For decades now, I've had a consistent gym routine. And, being middle-aged, I am now surrounded by peers and colleagues who want to know how one maintains a consistent gym routine in middle age.

My answer: I exercise for the high.

Not for better health. Not to look better in my jeans. Not to keep up with my students. Not because my doctor says concerning nickel words like "cholesterol" or "osteoporosis." I exercise for one reason only, and that reason is the dopamine.

I have also started doing math for the high.

Specifically: I ordered a set of unit blocks/rods. The ones that come in ones, tens, hundreds, and thousands.

I ordered them because I suck at decimals, and I figured they'd come in handy when trying to deal with those. I started using them for basic addition and subtraction, however, because the Maths-No Problem series encourages students to use them when reviewing at the top of each new lesson.

These books with their cute cartoon children haven't failed me yet. So okay, cute cartoon kids. I'll try the blocks.

And y'all, these little bricks are intensely satisfying to use.

They feel nice. They make cool clicky noises when they bump each other. They sort into neat little countable piles. The ones, tens, and hundreds are different colors, so my brain always knows which column we're in. I can count up to ten in any one pile and trade it in for the next pile up, which is way more satisfying than "carrying the one."

Every moment with these is a tiny dopamine hit. And that's hugely important.

We've known for years that dopamine production plays a key role in learning, though we haven't always understood why. Does dopamine provide motivation? Does it drive formation of neural pathways? Maybe both? It's also doing something in our working memory (a notorious weakness in dyscalculia and ADHD, among others), but what?

As an ADHDer, I already live with a deficit of dopamine in the anterior cingulate cortex - leading to issues with working memory, attention, focus, reward-based motivation, and a host of other ills. On top of that, I started associating math with drudgery, anxiety, and stress at the age of five.

The brain pathways that tell me "numbers are misery, don't try" are well worn in. But those pathways led me where I am today - barely numerate enough to function as an adult. I need new routes.

Fun plastic clicky unit blocks are building those new routes. So heck yes, I'm playing with them. Every math learner should. Make the brain associate math with happy. Do it for the high.

Further Reading:

Roy A. Wise, "Dopamine, Learning and Motivation," in Nature Reviews Neuroscience

"How Does Dopamine Regulate Both Learning and Motivation?", Science Daily

Namboodiri, Vijay MK, "'But why?' Dopamine and causal learning," Current Opinions in Behavioral Sciences

Base Ten Blocks at Hand2Mind (the set I purchased is substantially similar to this one)

#actually dyscalculic#dyscalculia#embarrassing myself#teaching math#actually adhd#math anxiety#math dyslexia#counting#dopamine#learning#mathblr

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Architecture of Uncertainty: How Doubt Shapes the Evolving Mind

In psychology, doubt is often seen as a cognitive process rooted in our brain’s effort to ensure accuracy, safety, and adaptability.

From a neuropsychological perspective, doubt arises from activity in areas like the prefrontal cortex, which is responsible for decision-making, and the anterior cingulate cortex, which detects conflicts and errors. When we’re unsure about something a memory, a belief, a decision these brain regions light up to trigger re-evaluation. In this way, doubt acts like an internal editor: “Are you sure?” “Is this safe?” “Do you really believe that?”

It’s adaptive. Doubt helps us:

Avoid impulsive or dangerous behavior

Reflect before acting or speaking

Learn from mistakes

Challenge false assumptions

Reassess values or goals when circumstances change

However, too much doubt especially when paired with anxiety can lead to rumination, indecisiveness, or obsessive-compulsive tendencies. In clinical psychology, this is referred to as pathological doubt, where a person becomes trapped in cycles of uncertainty that interfere with daily functioning.

On the flip side, healthy doubt supports curiosity and growth. It’s what fuels scientific discovery, critical thinking, and personal transformation. Instead of blind certainty, we learn to question and adapt.

#womeninthere30s#hello tumblr#digital diary#mujer#self reflecting#pathologic#mental health#critical thinking

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

THIS IS NOT HYPNOTIC or EROTIC

If you are curious about what hypnosis does to the brain, you might be interested in learning about the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex (DACC). This is a part of the brain that helps us stay alert and aware of our surroundings. It also plays a role in self-consciousness and emotional regulation. But what happens to the DACC when we are hypnotized? According to a groundbreaking study by Stanford University, hypnosis reduces the activity of the DACC, making us less vigilant and more relaxed. This also means that we are more open to suggestions and less inhibited by our usual worries or fears. Hypnosis can also change the way different brain regions communicate with each other. For example, hypnosis can increase the connection between the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) and the insula, which are involved in executive control and interception, respectively. This can help us focus on our inner sensations and feelings, and ignore external distractions. On the other hand, hypnosis can decrease the connection between the DLPFC and the posterior cingulate cortex (PCC), which are part of the default mode network (DMN). The DMN is active when we are not engaged in any specific task, and it is associated with self-referential thinking and mind-wandering. By weakening the link between the DLPFC and the PCC, hypnosis can reduce our tendency to ruminate or daydream, and make us more attentive to the present moment. These changes in brain activity and connectivity can explain why hypnosis can be a powerful tool for pain management, anxiety relief, trauma recovery, and many other applications. Hypnosis can help us access a state of mind that is more receptive, flexible, and creative. Isn't that amazing?

#hypnosis#hypnotic#brainwash#hypno sub#hypnotism#controlled#hypnotized#mind control#mesmerizing#trippy

365 notes

·

View notes

Text

ELECTROCHEMISTRY (Impossible: Failure) - Drink yourself silly and don’t stop just keep drinking it feels so good you should go do it now don’t you miss it?

HALF LIGHT (Easy: Failure) - Kill your self

ENCYCLOPEDIA (Impossible: Success) - The rate of OCD among first-degree relatives of adults with OCD is approximately two times that among first-degree relatives of those without the disorder; however, among first-degree relatives of individuals with onset of OCD in childhood or adolescence, the rate is increased 10-fold. Familial transmission is due in part to genetic factors (e.g., a concordance rate of 0.57 for monozygotic vs. 0.22 for dizygotic twins). Twin studies suggest that additive genetic effects account for ~40% of the variance in obsessive-compulsive symptoms. Dysfunction in the orbitofrontal cortex, anterior cingulate cortex, and striatum have been most strongly implicated; alterations in frontolimbic, frontoparietal, and cerebellar networks have also been reported.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Preserved in our archive

A research letter from 2022 highlighting the effects of even "mild" covid on the brain.

Dear Editor,

A recent study published in Nature by Douaud and colleagues1 shows that SARS-CoV-2 infection is associated with longitudinal effects, particularly on brain structures linked to the olfactory cortex, modestly accelerated reduction in global brain volume, and enhanced cognitive decline. Thus, even mild COVID-19 can be associated with long-lasting deleterious effects on brain structure and function.

Loss of smell and taste are amongst the earliest and most common effects of SARS-CoV-2 infection. In addition, headaches, memory problems, confusion, or loss of speech and motility occur in some individuals.2 While important progress has been made in understanding SARS-CoV-2-associated neurological manifestations, the underlying mechanisms are under debate and most knowledge stems from analyses of hospitalized patients with severe COVID-19.2 Most infected individuals, however, develop mild to moderate disease and recover without hospitalization. Whether or not mild COVID-19 is associated with long-term neurological manifestations and structural changes indicative of brain damage remained largely unknown.

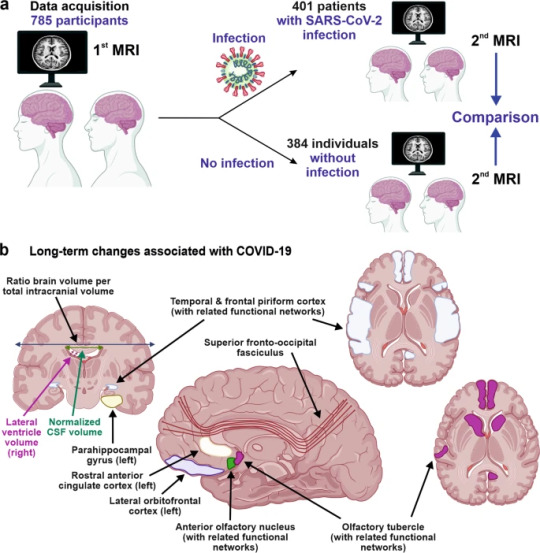

Douaud and co-workers examined 785 participants of the UK Biobank (www.ukbiobank.ac.uk) who underwent magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) twice with an average inter-scan interval of 3.2 years, and 401 individuals testing positive for SARS-CoV-2 infection between MRI acquisitions (Fig. 1a). Strengths of the study are the large number of samples, the availability of scans obtained before and after infection, and the multi-parametric quantitative analyses of serial MRI acquisitions.1 These comprehensive and automated analyses with a non-infected control group allowed the authors to dissect consistent brain changes caused by SARS-CoV-2 infection from pre-existing conditions. Altogether, the MRI scan processing pipeline used extracted more than 2,000 features, named imaging-derived phenotypes (IDPs), from each participant’s imaging data. Initially, the authors focused on IDPs involved in the olfactory system. In agreement with the frequent impairment of smell and taste in COVID-19, they found greater atrophy and indicators of increased tissue damage in the anterior cingulate cortex, orbitofrontal cortex and insula, as well as in the ventral striatum, amygdala, hippocampus and para-hippocampal gyrus, which are connected to the primary olfactory cortex (Fig. 1b). Taking advantage of computational models allowing to differentiate changes related to SARS-CoV-2 infection from physiological age-related brain changes (e.g. decreases of brain volume with aging),3 they also explored IDPs covering the entire brain. Although most individuals experienced only mild symptoms of COVID-19, the authors detected an accelerated reduction in whole-brain volume and more pronounced cognitive declines associated with increased atrophy of a cognitive lobule of the cerebellum (crus II) in individuals with SARS-CoV-2 infection compared to the control group. These differences remained significant when 15 people who required hospitalization were excluded. Most brain changes for IDPs were moderate (average differences between the two groups of 0.2–2.0%, largest for volume of parahippocampal gyrus and entorhinal cortex) and accelerated brain volume loss was “only” observed in 56–62% of infected participants. Nonetheless, these results strongly suggest that even clinically mild COVID-19 might induce long-term structural alterations of the brain and cognitive impairment.

The study provides unique insights into COVID-19-associated changes in brain structure. The authors took great care in appropriately matching the case and control groups, making it unlikely that observed differences are due to confounding factors, although this possibility can never be entirely excluded. The mechanisms underlying these infection-associated changes, however, remain to be clarified. Viral neurotropism and direct infection of cells of the olfactory system, neuroinflammation and lack of sensory input have been suggested as reasons for the degenerative events in olfactory-related brain structures and neurological complications.4 These mechanisms are not mutually exclusive and may synergize in causing neurodegenerative disorders as consequence of COVID-19.

The study participants became infected between March 2020 and April 2021, before the emergence of the Omicron variant of concern (VOC) that currently dominates the COVID-19 pandemic. During that time period, the Alpha and Beta VOCs dominated in the UK and all results were obtained from individuals between 51 and 81 years of age. It will be of great interest to clarify whether Omicron, that seems to be less pathogenic than other SARS-CoV-2 variants, also causes long-term brain damage. The vaccination status of the participants was not available in the study1 and it will be important to clarify whether long-term changes in brain structure also occur in vaccinated and/or younger individuals. Other important questions are whether these structural changes are reversible or permanent and may even enhance the frequency for neurodegenerative diseases that are usually age-related, such as Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s or Huntington’s disease. Previous findings suggest that cognitive disorders improve over time after severe COVID-19;5 yet it remains to be determined whether the described brain changes will translate into symptoms later in life such as dementia. Douaud and colleagues report that none of top 10 IDPs correlated significantly with the time interval between SARS-CoV-2 infection and the 2nd MRI acquisition, suggesting that the observed abnormalities might be very long-lasting.

Currently, many restrictions and protective measures are relaxed because Omicron is highly transmissible but usually causes mild to moderate acute disease. This raises hope that SARS-CoV-2 may evolve towards reduced pathogenicity and become similar to circulating coronaviruses causing mild respiratory infections. More work needs to be done to clarify whether the current Omicron and future variants of SARS-CoV-2 may also cause lasting brain abnormalities and whether these can be prevented by vaccination or therapy. However, the finding by Douaud and colleagues1 that SARS-CoV-2 causes structural changes in the brain that may be permanent and could relate to neurological decline is of concern and illustrates that the pathogenesis of this virus is markedly different from that of circulating human coronaviruses. Further studies, to elucidate the mechanisms underlying COVID-19-associated neurological abnormalities and how to prevent or reverse them are urgently needed.

REFERENCES (Follow link)

#public health#wear a mask#covid 19#pandemic#covid#wear a respirator#mask up#still coviding#coronavirus#sars cov 2#long covid#covid conscious#covid is airborne

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

Interesting Papers for Week 11, 2025

Visual Processing by Hierarchical and Dynamic Multiplexing. Bonnefond, M., Jensen, O., & Clausner, T. (2024). ENeuro, 11(11), ENEURO.0282-24.2024.

Bifurcation Enhances Temporal Information Encoding in the Olfactory Periphery. Choi, K., Rosenbluth, W., Graf, I. R., Kadakia, N., & Emonet, T. (2024). PRX Life, 2(4), 043011.

Oculomotor Contributions to Foveal Crowding. Clark, A. M., Huynh, A., & Poletti, M. (2024). Journal of Neuroscience, 44(48), e0594242024.

Causal relational problem solving in toddlers. Goddu, M. K., Yiu, E., & Gopnik, A. (2025). Cognition, 254, 105959.

Bilateral Alignment of Receptive Fields in the Olfactory Cortex. Grimaud, J., Dorrell, W., Jayakumar, S., Pehlevan, C., & Murthy, V. (2024). ENeuro, 11(11), ENEURO.0155-24.2024.

An inductive bias for slowly changing features in human reinforcement learning. Hedrich, N. L., Schulz, E., Hall-McMaster, S., & Schuck, N. W. (2024). PLOS Computational Biology, 20(11), e1012568.

A social information processing perspective on social connectedness. Hein, G., Huestegge, L., Böckler-Raettig, A., Deserno, L., Eder, A. B., Hewig, J., Hotho, A., Kittel-Schneider, S., Leutritz, A. L., Reiter, A. M. F., Rodrigues, J., & Gamer, M. (2024). Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 167, 105945.

Distinct Modulation of I h by Synaptic Potentiation in Excitatory and Inhibitory Neurons. Herstel, L. J., & Wierenga, C. J. (2024). ENeuro, 11(11), ENEURO.0185-24.2024.

An algorithmic account for how humans efficiently learn, transfer, and compose hierarchically structured decision policies. Li, J.-J., & Collins, A. G. E. (2025). Cognition, 254, 105967.

Conflict during learning reconfigures the neural representation of positive valence and approach behavior. Molina-García, L., Colinas-Fischer, S., Benavides-Laconcha, S., Lin, L., Clark, E., Treloar, N. J., García-Minaur-Ortíz, B., Butts, M., Barnes, C. P., & Barrios, A. (2024). Current Biology, 34(23), 5470-5483.e7.

Anticipating multisensory environments: Evidence for a supra-modal predictive system. Sabio-Albert, M., Fuentemilla, L., & Pérez-Bellido, A. (2025). Cognition, 254, 105970.

How visual experience shapes body representation. Shahzad, I., Occelli, V., Giraudet, E., Azañón, E., Longo, M. R., Mouraux, A., & Collignon, O. (2025). Cognition, 254, 105980.

Learning from conditional probabilities. Strößner, C., & Hahn, U. (2025). Cognition, 254, 105962.

Impact of conflicts between long- and short-term priors on the weighted prior integration in visual perception. Sun, Q., Gong, X.-M., & Sun, Q. (2025). Cognition, 254, 106006.

Neural Transformation from Retinotopic to Background-Centric Coordinates in the Macaque Precuneus. Uchimura, M., Kumano, H., & Kitazawa, S. (2024). Journal of Neuroscience, 44(48), e0892242024.

One-shot entorhinal maps enable flexible navigation in novel environments. Wen, J. H., Sorscher, B., Aery Jones, E. A., Ganguli, S., & Giocomo, L. M. (2024). Nature, 635(8040), 943–950.

Impulsive Choices Emerge When the Anterior Cingulate Cortex Fails to Encode Deliberative Strategies. White, S. M., Morningstar, M. D., De Falco, E., Linsenbardt, D. N., Ma, B., Parks, M. A., Czachowski, C. L., & Lapish, C. C. (2024). ENeuro, 11(11), ENEURO.0379-24.2024.

Neuronal sequences in population bursts encode information in human cortex. Xie, W., Wittig, J. H., Chapeton, J. I., El-Kalliny, M., Jackson, S. N., Inati, S. K., & Zaghloul, K. A. (2024). Nature, 635(8040), 935–942.

Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation over the Posterior Parietal Cortex Increases Nontarget Retrieval during Visual Working Memory. Ye, S., Wu, M., Yao, C., Xue, G., & Cai, Y. (2024).ENeuro, 11(11), ENEURO.0265-24.2024.

Fault-tolerant neural networks from biological error correction codes. Zlokapa, A., Tan, A. K., Martyn, J. M., Fiete, I. R., Tegmark, M., & Chuang, I. L. (2024). Physical Review E, 110(5), 054303.

#neuroscience#science#research#brain science#scientific publications#cognitive science#neurobiology#cognition#psychophysics#neurons#neural computation#neural networks#computational neuroscience

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Something I learned about the brain and willpower:

There is a section of the brain in the prefrontal cortex that is responsible for controlling our willpower called the aMCC (Anterior Mid-Cingulate Cortex).

The more hard/inconvenient things you do, the bigger it grows, meaning that those tasks may become easier over time. This then may help us break through mental blocks that are keeping us from doing things we enjoy because as it grows we end up with more willpower to use (kinda like exercising a muscle, the more you use it the more weight you can lift over time. When it comes to being autistic, I almost think of it as adding more spoons to my day)

The things that grow the aMCC are inconvenient tasks (not tasks that put you in danger), like doing the dishes. I hate doing the dishes, but now that I know that I get to strengthen my brain by being mildly inconvenienced for a few minutes. it makes it a little easier to do them. I also struggle with getting out of bed in the morning.

I also learned that learning new things is almost ALWAYS going to be challenging. When we try to pull our brain to attention to learn something new, we are actively suppressing the "autopilot" part of our brain. When this autopilot is suppressed, this pathway releases chemicals that make us anxious and uneasy. This suppression also helps to strengthen our willpower, which in turn makes whatever task we want to learn a little bit easier.

This also happens when you hold back a comment you know you shouldn't say to someone. You are actively suppressing your automatic response, which is why you may feel uncomfortable while keeping yourself from saying something, even if it's a comment you know you shouldn't say.

As a diagnosed autistic person that probably also has ADHD, this information helps me SO much. I really need to know the in depth reason as to why I act a certain way on almost a cellular level for me to really change how I act. I've been struggling with task initiation paralysis, impulsivity when speaking, and decision making. Knowing that my body is wired to feel uncomfortable when I do something out of routine, and I will always feel some level of resistance when trying to do something I don't want to do, helps so much with how I move about my day.

I got this info from Andrew Huberman, a neuroscientist, from his podcast episode about willpower and tenacity.

#actually autistic#actually adhd#self care#willpower#physiology#biology#psychology#neurology#neurodivergent

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Marijuana Users Have More Empathy And A Greater Understanding Of Other People's Emotions, Study Finds

Researchers said the results suggest a potential association between cannabis use and empathy, though they caution that further research is needed to fully understand the interactions “since many other factors may be at play.”

In attempting to explain the findings, the team of neuroscientists noted that a part of the brain, the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), “is a region that is prone to the effects of cannabis consumption and is also greatly involved in empathy, which is a multi-component process that can be influenced in different ways.”

“Given that the ACC is one of the main areas that possess CB1 [cannabinoid] receptors and is heavily involved in the representation of the affective state of others,” the study says, “we believe that the differences shown by regular cannabis users in the emotional comprehension scores and their brain functional connectivity could be related to the use of cannabis.”

Despite the qualifiers, the study concludes, “Given previous studies of the effect of cannabis on mood and emotional detection, we believe that these results contribute to open a pathway to study further the clinical applications of the positive effect that cannabis or cannabis components could have in affect and social interactions.”

In other neuroscience research this year, researchers at the University of West Attica in Greece found that medical marijuana use was associated with improved quality of life — including better job performance, sleep, appetite, and energy — among people with neurological disorders.

Another recent study published by the American Medical Association found that medical marijuana was associated with “significant improvements” in quality of life for people with conditions like chronic pain and insomnia—and those effects were “largely sustained” over time.

Other studies have found cannabis may boost the “runner's high” felt during exercise and enhance the practice of yoga.

#science!#i love research#I'm so happy they're allowed to study cannabis even more#lol weed#yay weed#the runner's high can be mimicked with cannabis i knew it

18 notes

·

View notes