#Rostral Anterior Cingulate Cortex

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Human Beings are Hardwired for Consciousness.

Did you know the part of your brain we think Consciousness comes from is called the 'Rostral Anterior Cingulate Cortex' that plays a key role in experiencing of emotions,..... and reward-based decision-making and learning, including motivation, cost-benefit calculation, as well as conflict and error monitoring.

It also determines whether our future will be one of clear-blue skies or dark stormy clouds.

This is because Optimism and Pessimism are not hardwired in our brain, and we as the Gods we are determine if we use cognitive behavioral techniques to overcome our natural tendencies towards doom and gloom.

So what do you think you want to do, dwell on mistakes of the past and continue to pick at the scab, or do you make a fresh start, and leave your mistakes in the past where they really belong?

Because we do know our lives are better when we choose Optimism, and that's where consciousness comes into play, because it is hardwired in our brain, we just have to realize it is we who are the God, and we make all of the decisions in our livelihood, not anything outside of ourselves like the Gods man creates to make us think THEY are in charge, because they aren't, we are.

But as I've said those choices aren't Hardwired in our brains, and we can choose to let religions God make all of our decisions for us.

Or we can choose to follow our heart, through your brains consciousness,.... the choice is entirely up to YOU!

0 notes

Text

Also preserved in our archive

"Just a cold" that changes the structure and mass of your brain

By Nikhil Prasad

Medical News: A groundbreaking study from researchers at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA)-USA has shed light on how Long COVID is linked to structural changes in the brain caused by SARS-CoV-2. By using advanced imaging techniques, the team discovered structural changes in the brains of individuals with Long COVID, including increased cortical thickness and gray matter volume in specific regions. This Medical News report will explore the study's key findings, its implications for understanding Long COVID, and what it means for patients suffering from this persistent condition.

Understanding the Research Approach The study involved participants from the UCLA hospital and broader Los Angeles community, with 36 individuals ranging in age from 20 to 67. Among them, 15 had Long COVID symptoms, while others were used as healthy controls. Researchers utilized structural magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to compare brain differences between these groups. The study focused on specific brain regions, such as the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) and the cingulate gyrus, which are known to be involved in cognitive and emotional processes. These areas were chosen because they are susceptible to inflammation and have been linked to neuropsychiatric symptoms.

To assess participants' cognitive and emotional health, tools like the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) and the Hamilton Anxiety and Depression scales were used. The imaging data were processed using specialized software to measure cortical thickness and gray matter volume, providing a detailed look at the brain's structural changes.

Key Study Findings The study revealed several critical findings that deepen our understanding of Long COVID's impact on the brain. Participants with Long COVID showed:

-Increased Cortical Thickness: Regions such as the caudal anterior cingulate, posterior cingulate, and rostral middle frontal gyrus exhibited significantly higher cortical thickness compared to controls.

-Higher Gray Matter Volume: In areas like the posterior and isthmus cingulate gyri, Long COVID patients had greater gray matter volume.

Interestingly, these structural changes were associated with the severity of clinical symptoms. For example, higher thickness in the cingulate regions correlated with more severe chronic illness scores, while increased insular thickness was linked to anxiety levels.

Such changes suggest that Long COVID might lead to either swelling due to inflammation or compensatory mechanisms like neurogenesis to counteract damage.

How This Study Compares with Previous Research While most COVID-19-related brain studies have shown reductions in gray matter and cortical thickness, this research indicates an increase in these metrics for Long COVID pa tients. Prior studies focused on acute COVID cases often revealed brain shrinkage and cognitive decline. In contrast, this study highlights that Long COVID might involve unique mechanisms, such as prolonged inflammation or a compensatory response to earlier damage.

Implications for Patients and Healthcare Providers These findings are crucial for both patients and healthcare professionals. They suggest that the persistent symptoms of Long COVID, such as brain fog, fatigue, and anxiety, could have a physical basis in brain structure changes. Recognizing this connection can lead to better-targeted treatments and interventions.

The Future of Long COVID Research While this study offers valuable insights, it also leaves many questions unanswered. For example, are these brain changes reversible? Do they worsen over time? The researchers acknowledge the study's limitations, including its small sample size and lack of longitudinal data. Future studies should aim to include larger, more diverse populations and examine changes over time to build a clearer picture of Long COVID's effects.

Conclusions This research from UCLA represents a significant step forward in understanding the neurological impacts of Long COVID. The observed increases in cortical thickness and gray matter volume in certain brain regions provide strong evidence that Long COVID involves measurable structural brain changes. These findings offer hope that by identifying the physical manifestations of this condition, we can develop more effective treatments to alleviate its symptoms. However, the path forward requires continued research to uncover the full extent of these changes and their implications.

The study emphasizes the importance of addressing neuropsychiatric symptoms in Long COVID patients and highlights the need for comprehensive care that includes both physical and mental health support. As we move forward, it is vital to integrate these insights into public health strategies to help those affected by this debilitating condition.

The study findings were published in the peer-reviewed journal: Frontiers in Psychiatry. www.frontiersin.org/journals/psychiatry/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2024.1412020/full

#mask up#public health#wear a mask#pandemic#wear a respirator#covid#covid 19#still coviding#coronavirus#sars cov 2#long covid#covid is not over

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

Introduction

In the last decade, there has been a rapid increase in the numbers of young people with gender dysphoria (GD youth) presenting to health services (Kaltiala et al., 2020). There has also been a marked change in the treatment approach. The previous “common practice” of providing psychosocial care only to those under 18 or 21 years (Smith et al., 2001) has largely been replaced by the gender affirmative treatment approach (GAT), which for adolescents includes hormonal and surgical interventions (Coleman et al., 2022). However, as a recent review concluded, evidence on the appropriate management of youth with gender incongruence and dysphoria is inconclusive and has major knowledge gaps (Cass, 2022). Previous papers have discussed that the weaknesses of the studies investigating the efficacy of GAT for GD youth mean they are at high risk of bias and confounding and, thus, provide very low certainty evidence (Clayton, 2022a, b; Levine et al., 2022). To date, however, there has been little discussion of the inability of these studies to differentiate specific treatment effects from placebo effects. Of note, the term “placebo effect” is no longer used to just simply refer to the clinical response following inert medication; rather, it describes the beneficial effects attributable to the brain-mind responses evoked by the treatment context rather than the specific intervention (Wager & Atlas, 2015). This Letter argues that the current treatment approach for GD youth presents a perfect storm environment for the placebo effect. This raises complex clinical and research issues that require attention and debate.

A Brief Introduction to the Contemporary Concept of the Placebo Effect

The term “placebo effect” can be used variably by different authors. As recently defined in a consensus statement, placebo (beneficial) and nocebo (deleterious) effects occur in clinical or research contexts and are due to psychobiological mechanisms evoked by the treatment (or research) context rather than any specific effect of the intervention. Importantly, placebo and nocebo effects not only occur during the prescription of placebo (inert) pills, but they can also substantially modulate the efficacy and tolerability of active medical treatments (Evers et al., 2018).

The therapeutic ritual, the encounter between a sick person and a clinician, is a powerful psychosocial event. Clinicians, particularly physicians, are our society’s designated healers and their prestige, status, and authority help engender patients’ trust and expectations of relief from suffering (Benedetti, 2021a). Positive clinician–patient interactions are associated with decreased anxiety and increased hope. Complex neurobiological mechanisms are implicated in the placebo effect, including release of neurotransmitters (e.g., endorphins, cannabinoids, dopamine, and oxytocin) and activation of specific areas of the brain (e.g., the prefrontal cortex, anterior insula, rostral anterior cingulate cortex, and the amygdala) (Colloca & Barsky, 2020; Kaptchuk & Miller, 2015). These changes are associated with an increased sense of well-being. They also impact on cardiovascular, respiratory, immune, and endocrine functioning, all of which may contribute to patients’ clinical improvement (Enck et al., 2013; Wager & Atlas, 2015).

Several unconscious psychological mechanisms, including classical conditioning and social learning, play a role in the placebo effect (Benedetti, 2021a). In clinical trials, where patients communicate with each other, a process of social observational learning may be associated with emotional contagion and, thus, placebo and nocebo effects (Benedetti, 2013). The media and social media may also foster these effects and contribute to the dissemination of symptoms and illness throughout the general population (Colloca & Barsky, 2020).

Expectation of outcome is a principal mechanism of the placebo effect and anything that increases patients’ expectations is potentially capable of boosting placebo effects (Evers et al., 2018). Although research has demonstrated that changes in physiological parameters may occur following placebo administration (Wager & Atlas, 2015), these response expectations have been particularly noted in patient-reported outcomes, such as anxiety, pain, life satisfaction, and mood. Expectations and cognitive readjustment can lead to behavioral changes, such as resuming normal daily activities, which can be observer rated. Physicians’ status, whether through the general position given to them in society or through individual personality factors, may contribute to such expectations of benefit. This type of phenomenon has sometimes been termed prestige suggestion. The “Hawthorne effect” describes the phenomenon where clinical trial patients’ improvements may occur because they are being observed and given special attention. A patient who is part of a study, receiving special attention, and with motivated clinicians, who are invested in the benefits of the treatment under study, is likely to have higher expectations of therapeutic benefits (Benedetti, 2021a).

Placebo-induced improvements are real and can be robust and long lasting (Benedetti, 2021b; Wager & Atlas, 2015). Individual patient factors, such as personality and genetics, may be associated with placebo responsiveness (Benedetti, 2021a). The particular illness is also relevant. For example, although placebo treatment can impact symptoms of cancer, there is no evidence that placebos can shrink tumors (Benedetti, 2021b; Kaptchuk & Miller, 2015). However, there is evidence that placebos can act as long-lasting and effective treatments for depression and various pain conditions, such as migraine and osteoarthritic knee pain (Kam-Hansen et al., 2014; Kirsch, 2019; Previtali et al., 2021). Further, some research suggests adherence to placebo medication, particularly in cardiac disease, may be associated with reduced mortality (Wager & Atlas, 2015).

The Research Setting versus the Clinical Practice Setting

Research into new medical treatments aims to control for placebo effects, and this helps ensure true evaluation of the treatment’s efficacy (Enck et al., 2013). The double-blind randomized controlled trial (DBRCT), although not perfect, is the current gold standard for determining the efficacy and safety of a treatment. The DBRCT study design evolved over several centuries and became widely accepted practice in the mid-twentieth century (Lilienfeld, 1982). Of note, the term “blind” is thought to have originated in eighteenth-century France when blindfolds were used to disprove Anton Mesmer’s “animal magnetism” theory and the mesmerism craze of that era (Kaptchuk, 1998). Well-designed DBRCTs minimize the impact of bias, confounding and placebo effects on findings and are the best type of study for determining whether there is a causal relationship between an intervention and an effect (Enck et al., 2013; Kabisch et al., 2011).

The reader may wonder about this requirement of differentiating placebo effects from the specific effects of an intervention and ask: If the patient improves, does it really matter why? Yes, it does, particularly for treatments that have significant risk of adverse effects. There are also broader problems raised by relying on the placebo effect. Consider prescribing antibiotics for viral infections. The patient may experience clinical benefit through a placebo effect. However, not only may some patients experience serious adverse drug reactions, but the health of the whole population is imperiled by the problem of antibiotic resistance (Llor & Bjerrum, 2014). Furthermore, informed consent is an ethical pillar of modern medicine and requires clinician honesty and transparency. Clinicians deceptively utilizing placebo treatments do not meet this requirement (Barnhill, 2012; Kaldjian & Pilkington, 2021). A medical profession that does little to distinguish placebo effects from specific treatment effects risks becoming little different from pseudoscience and the quackery that dominated medicine of past times, with likely resulting decline in public trust and deterioration in patient outcomes (Benedetti, 2021a).

Ideally, in evidence-based medicine, a new treatment undergoes rigorous research and has reasonable evidence of benefit prior to being introduced as routine treatment (although ongoing further research often continues). Clinicians can then reasonably harness and enhance the placebo effect to improve outcomes (Enck et al., 2013). A placebo effect enhancing clinical setting, in which warm and empathic clinicians provide supportive and attentive health care, creates a “therapeutic bias” in patients, giving them hope and expectation of improvement. This is “legitimate” so long as it is done without deception and in a manner consistent with informed consent, trust, and transparency (Kaptchuk & Miller, 2015).

This ideal of clinical interventions having solid evidence of efficacy before being introduced as routine practice is not always a reality. Sometimes, it is more of a situation where the “cart” of clinical practice precedes the “horse” of rigorous research evidence. Then, this catch-up research may be undertaken in a placebo effect-enhancing clinical environment, rather than a placebo effect-controlled research environment. Such situations, especially when DBRCT are not possible, present the researcher and clinician with complex research and clinical conundrums. Some of these will now be explored using the example of the treatment of youth with gender dysphoria.

A Brief Introduction to the Gender-Affirming Treatment Model for Children and Adolescents with Gender Dysphoria

Gender dysphoria is a term used to describe the distress that is frequently felt by people whose sense of gender is incongruent with their natal sex (these people may also self-identify as transgender) and if the dysphoria is intense and persistent, alongside several other features, a DSM-5 diagnosis of gender dysphoria may be made (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). There has been a sharp rise in the numbers of children and adolescents identifying as transgender and being diagnosed with gender dysphoria (Kaltiala et al., 2020; Tollit et al., 2021; Wood et al., 2013). Many are natal sex females presenting in adolescence, and many have neurodevelopmental and psychiatric disorders (Kaltiala-Heino et al., 2018; Tollit et al., 2021; Zucker, 2019). International guidelines and child and adolescent gender clinics (CAGCs) commonly endorse a gender affirmative treatment approach (GAT) (Coleman et al., 2022; Hembree et al., 2017; Olson-Kennedy et al., 2019; Telfer et al., 2018). Key components of GAT include affirmation of a youth’s stated gender identity, facilitation of early childhood social transition, provision of puberty blockers to prevent the pubertal changes consistent with natal sex, and use of cross-sex hormones (CSH) and surgical interventions to align physical characteristics with gender identity (Ehrensaft, 2017; Rosenthal, 2021). This Letter’s discussion focuses primarily on the medical (puberty blockers and cross-sex hormones) and surgical elements of GAT.

GAT can achieve some of the desired masculine or feminine appearance outcomes, but the main arguments used to support the use of these treatments in GD youth are that they improve short- and long-term mental health and quality-of-life outcomes. However, this claim is only underpinned by low-quality (mostly short-term, uncontrolled, observational) studies, which provide very low certainty evidence, complemented by expert opinion (Clayton, 2022a; Hembree et al., 2017; NICE, 2020a,b; Rosenthal, 2021). No randomized controlled trials (RCTs), including none using the previous treatment approach as a comparative, have been undertaken. This low-quality evidence for the efficacy of GAT is of particular concern given the potential risks associated with GAT.

Risks of Gender-Affirming Medical and Surgical Treatments

Impaired fertility is a risk of cross-sex hormones, and the extent of reversibility of this is unclear (Cheng et al., 2019; Hembree et al., 2017). If puberty blockers are commenced in early puberty and followed by cross-sex hormones, there are no proven methods of fertility preservation (Bangalore Krishna et al., 2019). Surgeries, such as gonadectomies and most genital surgeries, will result in permanent sterility. These impaired fertility and sterility outcomes are important because, firstly, as Cheng et al. (2019) reported, the widespread assumption that many transgender people do not want to have biological children is not supported by several recent studies. Secondly, children as young as ten, who do not have capacity for informed consent, are starting a treatment course that will likely render them infertile or sterile and this raises complex bioethical issues (Baron & Dierckxsens, 2021).

Other adverse effects of GAT are based on a more uncertain evidence base. I provide a brief outline of some of the areas of concern. Cross-sex hormones are associated with cardiovascular health risks, such as thromboembolic, coronary artery, and cerebrovascular diseases (Hembree et al., 2017; Irwig, 2018). Cross-sex hormones may also increase the risk of certain cancers (Hembree et al., 2017; Mueller & Gooren, 2008). Puberty blockers may have negative impact on bone mineral density, which may not be fully reversible, with an associated risk of osteoporosis and fractures (Biggs, 2021; Hembree et al., 2017). Recently, findings from animal studies have increased concerns that puberty blockers may negatively and irreversibly impact brain development due to critical time-windows of brain development. In one study on rams, long-term spatial memory deficits induced by use of puberty blockers in the peripubertal period were found to persist into adulthood (Hough et al., 2017). For those young patients who undertake surgery, there are also the risks of surgical complications (Akhavan et al., 2021). One understudied outcome of mastectomies, for those who later want to and can become pregnant, is the grief about inability to breast feed.

Puberty blockers, cross-sex hormones and genital surgery also pose risks to sexual function, particularly the physiological capacity for arousal and orgasm. It is important to be aware there is a dearth of research studying the impact of GAT on GD youth’s sexual function, but I provide a brief discussion of this important topic. Estrogen use in transwomen is associated with decreased sexual desire and erectile dysfunction and testosterone for transmen may lead to vaginal atrophy and dyspareunia (Hembree et al., 2017). It seems widely assumed that testosterone simply improves transmen’s sexual functioning. However, placebo-controlled studies from the non-transgender population indicate the situation is likely more complex. For example, studies indicate that testosterone may impact female sexual desire in a bell-shape curve manner, and at high levels may have no benefit or even have negative impact on sexual function (Krapf & Simon, 2017; Reed et al., 2016). Also of note, in medical conditions that are associated with high testosterone levels, such as polycystic ovarian syndrome, impaired sexual function (e.g., arousal, lubrication, sexual satisfaction, and orgasm) has been reported (Pastoor et al., 2018).

Recently, surgeon and WPATH president-elect, Marci Bowers, raised concern that puberty blockers given at the earliest stages of puberty to birth sex males, followed by cross-sex hormones and then surgery, might adversely impact orgasm capacity because of the lack of genital tissue development (Ley, 2021). One study has reported that some young adults, who had received puberty blockers, cross-sex hormones and laparoscopic intestinal vaginoplasty, self-reported orgasmic capacity (Bouman et al., 2016). However, this finding does not negate Bower’s concerns, as it did not make any assessment of the correlation between Tanner stage at initiation of puberty blockers with orgasm outcome. Of note, some of the patients in the study were over the age of 18 at start of GAT. Further, its findings do not apply to those undergoing penile skin inversion vaginoplasty. Importantly, Bouman et al. found that 32% of their participants self-reported being sexually inactive and only 52% reported having had neovaginal penetrative sex more than once. A recent literature review on sexual outcomes in adults post-vaginoplasty noted the paucity of high-quality evidence but reported that “up to 29% of patients may be diagnosed with a sexual dysfunction due to associated distress with a sexual function disturbance” (Schardein & Nikolavsky, 2022). Another recent systematic review of vaginoplasty reported an overall 24% post-surgery rate of inability to achieve orgasm (Bustos et al., 2021).

Coleman et al. (2022) claimed that “longitudinal data exists to demonstrate improvement in romantic and sexual satisfaction for adolescents receiving puberty suppression, hormone treatment and surgery.” However, the supporting citation requires scrutiny. Bungener et al. (2020) was a cross-sectional study of 113 young adults, 66% of whom were transmen (most who had undergone mastectomy and gonadectomy, not genital surgery). For its claims of post-surgery increases in sexual experience, it relied on recall of pre-surgical experiences. This means it is at high risk of recall bias, especially given surgery was undertaken up to 5 years (mean 1.5 years) prior to assessment. Further, it focused on sexual experiences, which might naturally be expected to increase as adolescents enter young adulthood, and there was no evaluation of sexual function domains, such as arousal, orgasm, or pain. The study did report current sexual satisfaction but failed to compare this to pre-surgical functioning (or to the Dutch peer comparison group). Thus, it is unable to demonstrate whether sexual satisfaction improved following GAT. On the three questions about sexual satisfaction (frequency, how good sex feels, and sex life in general), 59 to 73% were reportedly moderately to very satisfied. This would appear to mean that 27 to 41% were not satisfied, which is a sizeable minority. Importantly, these sexual satisfaction questions had an approximately 45% missing data rate—an issue not discussed by the authors. This means the authors’ conclusion that the majority was satisfied with their sex life is at high risk of bias. Of additional note, at the post-surgical assessment time these young transgender adults were significantly less sexually experienced than their Dutch peers. Thus, in sum, this study provides little reassurance about the sexual function outcomes of GAT in GD youth.

Lastly, in terms of risks, there are increasing reports of discontinuation of hormone treatments, regret and detransition in young people who have received GAT (Boyd et al., 2022; Hall et al., 2021; Littman, 2021; Vandenbussche, 2022). Two recent studies have relied on pharmaceutical prescription records, both using 2018 as the end date of data collection (Roberts et al., 2022; van der Loos et al., 2022). Their reported rates of discontinuation varied widely. For the US cohort, Roberts et al. (2022) reported, for those who had started CSH treatment before age 18, a 4-year CSH discontinuation rate of 25%. For the Dutch cohort, van der Loos et al. (2022) reported on CSH discontinuation rates in adolescents, evaluated according to the “meticulous” Dutch protocol, who had commenced puberty blockers before age 18. People “assigned female at birth” had a CSH discontinuation rate of 1% at a median of 2.3-years follow-up, and those “assigned male at birth” had a 4% discontinuation rate at median 3.5-years follow-up. Previous research from this Dutch group has indicated that average time to detransition was over 10 years (Wiepjes et al., 2018). Thus, given the van der Loos et al. (2022) study’s short median follow-up time and young follow-up age (median 19.2 for people “assigned female at birth” and 20.2 for “assigned male at birth”), it seems likely that these discontinuation rates will increase over time. It is also concerning to note that 75% of the Dutch youth who discontinued CSH had undergone gonadectomies, but at follow-up they were receiving neither CSH nor sex hormones consistent with their birth sex.

Ongoing Research

Currently, several large long-term observational studies are underway which involve collecting and analyzing data on patients receiving routine GAT at CAGCs (Olson-Kennedy et al., 2019; Tollit et al., 2019). The aims of these studies are to provide the urgently needed rigorous empirical data to bolster the weak evidence base that currently underpins the GAT approach. However, as discussed above, it is critical to note that this type of observational research is prone to bias, confounding, and lacks ability to distinguish treatment effects from placebo effects (Fanaroff et al., 2020; Pocock & Elbourne, 2000). Thus, it is unlikely to provide the rigorous empirical data that can convincingly demonstrate a causal relationship between treatment and outcome.

Further, there seems to be a problematic tension between the research and clinical agendas of CAGCs. GAT is being provided in a clinical environment that maximizes the placebo effect. This is the same environment in which the same clinicians are researching GAT’s efficacy. As previously discussed, while a placebo effect-enhancing environment may be appropriate for a clinical environment, it is far from an ideal treatment efficacy research environment, particularly when DBRCTs are not possible and RCTs are not undertaken. In the next section, I delve more deeply into exploring this issue. First, however, I will take a brief detour with an example that illustrates the risks when expert opinion and low-quality evidence are relied on as a basis for medical interventions.

A Recent Example from Medical History of the Dangers of Medical Advice Based on Weak Evidence: The Iatrogenic Tragedy of Prone Infant Sleep Position and Sudden Infant Death Syndrome

Gender medicine clinicians and researchers have consistently stated that RCTs would be unethical (de Vries et al., 2011; Smith et al., 2001; Tollit et al., 2019). However, as Valenstein (1986) discussed in his study of the history of lobotomy, the ethics of implementing new treatments without a rigorous evidence base also need to be considered. The harm that can be done by well-intentioned, but erroneous medical advice based on prestigious physicians’ clinical judgment without an adequate evidence base can be illustrated by infant sleep position and sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS). Prior to the middle of the twentieth century, it was common practice for mothers to place infants on their backs to sleep (Högberg & Bergström, 2000). The influential pediatrician, Benjamin Spock, was an early advocate of the prone position (front sleeping) for infants. He recommended it in his popular book, Baby and Childcare, from the 1956 edition through until 1985 (Gilbert et al., 2005). This recommendation, that became widespread, was mainly based on clinical wisdom that such a position reduced risk of death from aspiration of vomit and had additional benefits such as decreased crying and reduced head flattening. Early research appeared to support this clinical advice. However, by the 1980s, more rigorous research demonstrated that the prone position increased risk of SIDS. Then medical advice gradually changed to strongly recommending infant supine (back) sleeping. A marked drop in SIDS rates followed. Several biases (e.g., the healthy adopter bias and observer bias) are thought to have contributed to the erroneous clinical belief that prone sleeping position was the safest position. It has been estimated that between the 1950s and the 1990s the infant prone sleeping advice, recommended by well-meaning clinicians and prestigious medical organizations, may have contributed to the deaths of tens of thousands of infants (Gilbert et al., 2005; Sperhake et al., 2018).

Gender-Affirming Treatment for Youth with Gender Dysphoria: A Perfect Storm for Placebo Effect

The reader may ask: Why focus on GAT for GD youth? Is GAT any different from other contemporary medical treatments that also are not underpinned by rigorous evidence? I would reply—indeed, this is an issue in other areas of medicine. For example, the response rate in the placebo groups in antidepressant medication clinical trials is known to be high (Benedetti, 2021a). However, in contrast to GAT, we know this because there have been many RCTs comparing antidepressants to placebos. A recent review, that included placebo in the network meta-analysis, found that all the antidepressants under review were more efficacious than placebo in adults with major depressive disorder (Cipriani et al., 2018). This finding has been challenged by some who argue that the benefits of antidepressants beyond placebo effect seem to be minimal (Jakobsen et al., 2020). However, one of the key points to make is that placebo effect in antidepressant medication response is at least known about and discussed by many researchers, clinicians, and their patients (personal clinical experience), rather than not considered at all, as seems to be the situation to date for GAT for GD youth. Gender medicine clinicians and researchers might take note of a recent meta-analysis of antidepressants in pediatric populations, which recommended that the influence of placebo response needs to be considered in pediatric clinical trial design and implementation (Feeney et al., 2022). Furthermore, it seems particularly vital to consider the potential role of placebo effect in GAT outcomes because the stakes are high. Medical and surgical GAT, being given to vulnerable minors, lead to life-long medicalization and hold the risk of serious irreversible adverse impacts, such as sterility and impaired sexual function. Thus, we need strong evidence that they are as efficacious for critical mental health outcomes as claimed and that there are no less harmful alternatives.

In the field of GD youth medicine, there is a combination of features that seems to create a perfect storm setting for placebo effect. Thus, we have a population of vulnerable youth presenting with a condition, which has no objective diagnostic tests, and that is currently undergoing an unexplained rapid increase in prevalence and marked change in patient demographics. The treatment response is mainly based on patient-reported outcomes (yes, this can be the case for other conditions but remember we are considering the combination of features, not just a feature in isolation). Some clinicians, who may be affiliated with prestigious institutions, enthusiastically promote GAT, including on the media, social media, and alongside celebrity patients. Some make overstated claims about the strength of evidence and the certainty of benefits of GAT, including an emphasis on their “life-saving” qualities, and under-acknowledge the risks. Alternative psychosocial treatment approaches are sometimes denigrated as harmful and unethical conversion practices or as “doing nothing.” This combination of features increases the likelihood that there will be a complex interplay of heightened placebo and nocebo effects in this area of medicine, with significant implications for research and clinical practice. Some examples of these types of issues are now provided.

Overstatement of the Certainty of Benefits and Under-Acknowledgment of Risks

Some professional organizations and leading GAT clinicians, in publicly available communications to GD youth, the public, and policy makers, appear to overstate the certainty of GAT’s benefits and provide inadequate discussions of risks (Clayton, 2022a; Cohen, 2021a, b; Olson-Kennedy, 2015, 2019; Telfer, 2019, 2021). For example, GATs have been described in such communications as “absolutely life-saving” (Olson-Kennedy, 2015) and being underpinned by “robust scientific research” (Telfer, 2019). It is notable that these same clinicians in their peer reviewed publications acknowledge the sparse empirical evidence with critical knowledge gaps (Olson-Kennedy et al., 2019), and the urgent need for more evidence for this relatively new treatment approach (Tollit et al., 2019). Thus, there seems to be a kind of Janus-faced narrative, with a placebo effect-enhancing face of overstated certainty/strong evidence of benefit displayed to GD youth, their families, and policy makers, and the more realistic face of uncertainty/lack of evidence turned toward peer reviewers and the research community. Of note, several publications in the peer review literature that have made overstated claims about GAT have recently required correction (Bränström & Pachankis, 2020; Pang et al., 2021; Zwickl et al., 2021).

The Dangers of an Exaggerated Suicide Narrative

A specific issue that is important to discuss is the repeated claims that GD youth are at high suicide risk and that GAT reduces this risk. Parents report being told by clinicians that their child will suicide if a trans identity is not affirmed (Jude, 2021). Clinicians’ public statements also indicate this message is being given, or at least implied, to parents and young people (Cohen, 2021b; Marchiano, 2017). A recent editorial in The Lancet stated puberty blockers reduce suicidality and to remove access to them was to “deny” life (The Lancet, 2021). However, there is no robust empirical evidence that puberty blockers reduce suicidality or suicide rates (Biggs, 2020; Clayton et al., 2021). The authors of the paper, that was the basis for The Lancet’s claim, subsequently clarified that they were not making any causal claims that puberty blockers decreased suicidality (Rew et al., 2021). Another paper, claiming to have found that barriers to gender-affirming care was associated with suicidality, had to withdraw this claim in a significant correction to their article (Zwickl et al., 2021).

Furthermore, the suicidality of GD youth presenting at CAGCs, while markedly higher than non-referred samples, has been reported to be relatively similar to that of youth referred to generic child and adolescent mental health services (Carmichael, 2017; de Graaf et al., 2022; Levine et al., 2022). A recent study reported that 13.4% of one large gender clinic’s referrals were assessed as high suicide risk (Dahlgren Allen et al., 2021). This is much less than conveyed by the often cited 50% suicide attempt figure for trans youth (Tollit et al., 2019). A recent analysis found that, although higher than population rates, transgender youth suicide (at England’s CAGS) was still rare, at an estimated 0.03% (Biggs, 2022).

Of course, any elevated suicidality and suicide risk is of concern, and any at risk adolescent should be carefully assessed and managed by expert mental health professionals. However, an excessive focus on an exaggerated suicide risk narrative by clinicians and the media may create a damaging nocebo effect (e.g., a “self-fulfilling prophecy” effect) whereby suicidality in these vulnerable youths may be further exacerbated (Biggs, 2022; Carmichael, 2017). This type of risk has been discussed in other similar situations involving youth (Abrutyn et al., 2020; Canetto et al., 2021; Shain & AAP COMMITTEE ON ADOLESCENCE, 2016).

An Excessively Negative Portrayal of the Previous Standard and Current Alternative Treatment Options

Clinicians and groups advocating for GAT tend toward framing any non-affirming treatment approaches as harmful, ineffective, and unethical, and sometimes equate psychotherapeutic approaches with conversion practices (Ashley, 2022). However, others argue that there are a range of contemporary therapeutic approaches which are not “affirmative,” but neither are they conversion practices (D’Angelo et al., 2021). Such approaches can include: Careful assessment and diagnostic formulation, appropriate treatment of co-existing psychological conditions, supportive and educative individual/family psychological care, group therapy, developmentally informed gender exploratory psychotherapy, trauma-informed psychotherapy, and a non-promotion of early childhood social transition (sometimes labeled under the umbrella term of “watchful-waiting,” which should not be interpreted as “doing nothing”) (D’Angelo et al., 2021; de Vries & Cohen-Kettenis, 2012; Hakeem, 2012; Kozlowska et al., 2021; Lemma, 2021).

It is important to note that psychotherapeutic approaches for this group of patients are also based on limited evidence. More research into their efficacy is required. One critical consideration here seems to be that ethical psychological approaches do not hold the same adverse risk profiles as do the hormonal and surgical treatments (Baron & Dierckxsens, 2021).

Recently, two Scandinavian youth gender services have drawn similar conclusions and instigated a more cautious approach to hormonal treatments for GD minors, placing a higher emphasis on psychological care (Kaltiala-Heino, 2022; Socialstyrelsen, 2022). Furthermore, in England, the Cass Review into the country’s youth gender services has released its interim report (Cass, 2022). In response, the National Health Service’s “Interim Service Specification” for GD youth specialist services has specified that the primary intervention for youth will be psychosocial support and psychological interventions. A cautious approach to social transition is recommended and puberty blockers will only be available in the context of a formal research protocol (National Health Service, 2022).

Given all this, it is hard to accept the claims that GAT is prima facie the best treatment model for today’s cohort of GD youth. Furthermore, the unwarranted negative portrayal of contemporary psychotherapeutic approaches likely creates nocebo effects and undermines the possibility of providing such ethical care to GD youth (Kozlowska et al., 2021).

Clinicians’ Media and Social Media Promotion of Gender Affirmative Treatment

There is intense media and social media coverage of “trans youth” issues. Some surgeons are promoting their gender-affirming surgeries on social media platforms that are popular with young adolescents (Ault, 2022). Some clinicians encourage the celebratory media coverage of GAT, stating it may empower young trans people to seek GAT (Pang et al., 2020). They largely dismiss concerns that the identified association between positive media stories and increased referral rates to CAGCs may be indicative of a social contagion phenomenon. This is despite the reports of the sudden emergence of gender dysphoria, especially in adolescence, and its association with social influence (Kaltiala-Heino, 2022; Littman, 2018, 2021; Marchiano, 2017). Gender clinicians also condemn and have attempted to prevent what they consider as excessively negative media coverage of GAT (although others judge it as reasonable and balanced) (Australian Press Council, 2021; Pang et al., 2022). These clinicians are likely correct that critical media coverage of GAT could negatively impact referrals to gender clinics and might upset some patients. However, a deliberate strategy of promoting an unbalanced celebratory GAT narrative through the media and social media could contribute to social contagion and placebo effects.

What is the right balance? The Australian Press Council’s judgment on a clinician’s complaints about what she considered as excessively negative press coverage may, arguably, provide an example of some balance on these matters. Of note, while some of the complaints were upheld, many were not and it was judged that “even medical treatment accepted as appropriate by a specialist part of the medical profession is open to examination and criticism…needs to be debated…and was sufficiently justified in the public interest” (Australian Press Council, 2021).

The Exclusive Promotion of Gender-Affirming Treatments within Child and Adolescent Gender Clinics

There is indication of an unbalanced promotion of a celebratory GAT narrative occurring within CAGCs, where, simultaneously, there is a deep enmeshment of the clinical, advocacy, and research agendas. This has already partly been discussed in the sections above, but one detailed example is provided. The Trans20 study is a prospective cohort study based on children and adolescents seen at Melbourne’s Royal Children’s Hospital Gender Clinic (RCHGC) which provides a GAT model of care (Telfer et al., 2018; Tollit et al., 2019). It is important to highlight that this study’s human research ethics committee (HREC) approval was not for the treatment approach, which was implemented as routine clinical care, rather it was for matters such as collection and storage of data, and longitudinal follow-up of discharged patients.

In 2019, an amended HREC approval was granted, allowing a “newsletter blog” to be sent to patients and families with the aim of improving patient engagement with the study. This change was described as raising no new ethical issues. This “first ever” newsletter asked for help with the Trans20 survey completion (Royal Children’s Hospital, 2019). This research request was placed amid positive accounts of the service and its patients. For example, following attendance at the clinic’s single session assessment triage (SSNac) young people were described as feeling “empowered…and more likely to start living as their preferred gender,” and having improvements in mental health and quality of life. A colorful diagram showed the increased rates of social transition that followed SSNac attendance, and the section concluded “Hopefully the improvements after SSNac are a taste of things to come!” One pro-GAT parent/carer support network, that also fundraises for the RCHGC, was spotlighted. There was a “lived experience” piece in which a well-known transitioned, now young adult, patient was pictured receiving an award. This patient provided a personal testimony of the clinic’s medical director: She “will always be one of my biggest heroes…an incredible person: Intelligent, compassionate and strong.”

This newsletter’s communication raises much to think about. The point I want to make here is that sandwiching the requests for a research survey completion between celebratory accounts of the clinic seems likely to magnify the impact of bias and placebo effect on research outcome findings. For example, consider the likely impact on patient bias (patients wanting to please the clinician by giving positive reports), response bias (patients with positive experiences of the clinic more likely to complete the surveys), social learning/contagion, prestige suggestion, and the Hawthorne phenomenon. Furthermore, consider this newsletter as part of the whole therapeutic ritual, enhancing the psychological and neurobiological placebo mechanisms. Apart from this research impact, we can also wonder whether such a newsletter is ideal clinical practice. In my opinion, there are problems. Think, for example, of the young GD patient who may be hesitant to transition. Where is the celebration of this young person’s choices? Communications from the clinic, such as this newsletter, may contribute to feelings that, unless he/she transitions, he/she lacks courage (having not been “empowered”) and that he/she will never be an award-winning celebrated patient. This may act as a covert form of pressure on patients to transition or, for those who do not, act as a nocebo effect negatively impacting their psychological outcomes.

Where to From Here?

There are no easy solutions to the complex research and clinical issues presented in this Letter. Here, I present a few ideas to stimulate discussion. The first step would seem to be more professional awareness and debate. Independent reviews by expert clinicians and methodologists, not currently involved in clinical practice and research in this area (thus, having some emotional distance and minimizing intellectual conflict risk), could helpfully advise further research and clinical strategies. England’s Cass Review is an example of this type of approach (Cass, 2022).

Clinicians should also make measured and honest statements to patients, families, policy makers, and the public about the evidence for GAT’s benefits. Placebo effects could also be noted in the limitations section of any research papers. In addition, in public discourse, the media and clinicians could present not only celebratory transition stories, but also: Realistic positive stories of those with gender dysphoria who have decided not to transition or have delayed transition until maturity; accounts of patients who have benefitted from ethical psychological approaches; and accounts of those who have had negative transition experiences. Detransition, regret, and harm from transition should be acknowledged and publicized as a significant risk. A recent paper detailing the elements of a comprehensive informed consent process is timely and important (Levine et al., 2022). However, while a comprehensive informed consent process is vital, it does not address the issue of how the whole ethos of a clinic and the media/social media milieu may act to influence young patients and their families and undermine the capacity for true informed consent.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this Letter has noted that although GAT for GD youth lacks a rigorous evidence base, it is undertaken as routine medical treatment in a strongly placebo effect enhancing environment. It is within this environment that research into its effectiveness is being undertaken. One consideration raised by this relates to clinical practice: When does such a strongly placebo effect enhancing environment meet optimal clinical practice standards? When, if at all, does it veer into the territory of unethical practice that involves deception and undue influence? This Letter has also highlighted that such a placebo effect enhancing environment presents grave problems for research (particularly non-DBRCT research). It seems unlikely that the current research being undertaken in this field will be able to untangle benefits that are due to the placebo effect from those due to the interventions’ specific effectiveness. Thus, especially given the adverse risk profile of the hormonal and surgical interventions, it may be that yet again well-intentioned physicians are engaging in medical practices that cause more harm than benefit (Clayton, 2022b). The research and clinical conundrums presented in this Letter have no easy answers. However, as a first step, there is an urgent need for more awareness of the placebo effect and for rigorous and thoughtful debate over how best to proceed in research and clinical practice in this area of medicine.

#Prisha Mosley#placebo effect#gender affirming care#gender affirming healthcare#gender affirmation#affirmation model

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Spatial Topography of the Brain

A meta-analysis of magnetic resonance imaging data of neuronal activity in advanced meditation practitioners has discovered a reorganization of information processing topography in which brain regions involved in present-awareness have increased activity while ego-centric and subject-object (discriminatory) neuronal information processing layers are mitigated [1]. The researchers identify the neural correlates associated with the feeling of unity of experience—a state that advanced meditation practitioners can experience, often described as a non-dual state of experience that does not maintain the strong distinction between self-other or subject-object information, but rather a unified experience of oneness, or singularity.

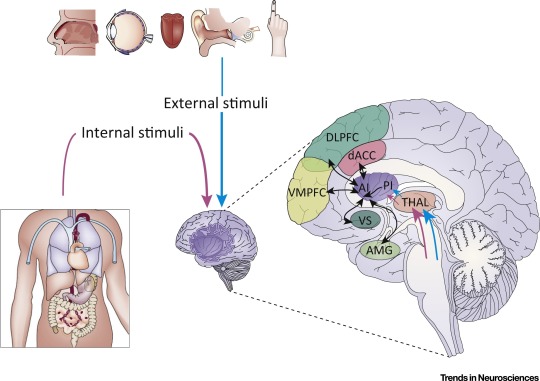

Figure 1: Interoceptive Information and Its Integration with Emotional, Cognitive, and Motivational Signals from an Array of Cortical and Subcortical Regions. Interoceptive information of constantly changing body states arrives in the posterior insula by ascending sensory inputs from dedicated spinal and brainstem pathways via specific thalamic relays. This information is projected rostrally onto the anterior insula, where it is integrated with emotional, cognitive, and motivational signals from an array of cortical and subcortical regions. As a result, the anterior insula supports unique subjective feeling states. The anterior insula regulates the introduction of subjective feelings into cognitive and motivational processes by virtue of its cortical location at the cross-roads of numerous pathways involved in higher cognition and motivation. Abbreviations: AI, anterior insula; AMG, amygdala; dACC, dorsal anterior cingulate cortex; DLPFC, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex; PI, posterior insula; THAL, thalamus; VMPFC, ventromedial prefrontal cortex; VS, ventral striatum. Image and image description from [3].

"From the meta-analysis data, the researchers determined that there is a distinctive shift in these information processing layers such that DMN activity is reduced, DMN-CEN synchronization undergoes a more positive connectivity, and dominant information processing shifts to the attention networks of higher order brain regions like the prefrontal cortex: leading to greater present-moment awareness and integration of self with environment and internal feelings."

Such reorganization of the brain’s information processing topology is significant in changing how a person perceives the world and their relationship to the experiences of daily life, in a therapeutic context this has made meditation a popular practice (even medically prescribed) to lower anxiety and stress, as mindfulness strengthens the brain’s ability to stay focused in the present-moment, so that undue worry is not given from constantly contemplating the past and potential future events. The former of which there is no way to change, and the latter of which is most effectively managed by actions in the present moment. Such mindfulness techniques have a long history of extolling benefits, with philosophical traditions from Stoicism to Buddhism explaining how mindfulness, focus in the present moment, and relinquishing negative judgements about events—that arise from excessive self-referential cognitive processing—can reduce suffering and help people achieve the most effective and optimal version of themselves [4].

The main results of the study are: (i) decreased posterior default mode network (DMN) activity

(ii) increased central executive network (CEN) activity

(iii) decreased connectivity within posterior DMN as well as between posterior and anterior DMN

(iv) increased connectivity within the anterior DMN and CEN

(v) and significantly impacted connectivity between the DMN and CEN (likely a nonlinear phenomenon).

Highlights:

This study has shown a significant and objective change in brain function because of meditation, inverting the predominant levels of information processing so that experience is not executing on “auto-pilot” but instead heightened awareness in the present moment enables highly conscious and effective activity. We would further posit that there are biophysical changes occurring all the way to the cellular and molecular resolution of information processing and bioenergetics. Such that the highly focused attention of meditation can engender a state of singularity, not just a singularity of perception. It is possible that such a state mitigates the decohering interactions in the molecular dynamics of the cell, so that long-range quantum coherent states are bolstered, leading to greater degrees of qubit information processing and Bose-Einstein like states (via mechanisms like Frohlich condensation [5]). Increases in information processing at this atomic resolution couples the body much more strongly to the vacuum information structure, enabling accession of nonlocal information and energy. Such that these coherent states correlate with an expanded state of awareness, in which non-local information processing in the macromolecular networks of the cellular system give much greater integration of signals from the self, environment, and beyond, enabling experiences of non-duality, or connection with the greater universe (beyond our normal mundane quotidian experiences of the world).

References

[1] A. C. Cooper, B. Ventura, and G. Northoff, “Beyond the veil of duality—topographic reorganization model of meditation,” Neuroscience of Consciousness, vol. 2022, no. 1, p. niac013, Jan. 2022, doi: 10.1093/nc/niac013

[2] P. Qin, M. Wang, and G. Northoff, “Linking bodily, environmental and mental states in the self—A three-level model based on a meta-analysis,” Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, vol. 115, pp. 77–95, Aug. 2020, doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2020.05.004

[3] H. Namkung, S.-H. Kim, and A. Sawa, “The Insula: An Underestimated Brain Area in Clinical Neuroscience, Psychiatry, and Neurology,” Trends in Neurosciences, vol. 41, no. 8, pp. 551–554, Aug. 2018, doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2018.05.004

[4] Lutz A, Dunne JD, Davidson RJ. Meditation and the neuroscience of consciousness: an introduction. In: Zelazo PD, Moscovitch M, Thompson E (eds.), The Cambridge Handbook of Consciousness. Cambridge University Press, 2007, 499–551.doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511816789.020

#consciousness#meditation#neuroscience#awareness#proprioception#perception#posterior insula#anterior insula#prefrontal cortex#duality#non duality#mindfulness

1 note

·

View note

Note

Reblogging with info (I also commented it)

From what I can see online, Dr Colin Ross (who is now 70 years old) was only the former president of the International Society for the Study of Trauma and Dissociation from 1993 to 1994. He has produced no studies or research in relation to endogenic plurality. An email stating it might be possible, is neither evidence nor research. It is simply a baseless claim that requires evidence and research. Dr. Eric Yarbrough is not a dissociative disorder specialist. On his own website, he has stated "My career has been focused on the LGBTQ population". He lists his specialties as: "Treatment of depression; anxiety; mood; and psychotic symptoms; LGBTQ-affirming psychotherapy; Gay men’s mental health needs; LGBTQ relationship issues; Coming Out to family, friends, or work; Questioning and exploration of sexual orientation; Sex Therapy - All sexual orientations and gender identities; Substance use concerns including opioid treatment; Professional work stress". I'm not sure why a psychiatrist, who doesn't specialize in either dissociation or PTSD, would talk in a book about DISORDERS, about a supposed non-disordered experience ? I actually got a PDF of the book: "The American psychiatric association publishing textbook of psychiatry 7th edition". I read the entire 40 page section on DID/dissociative disorders. Not once did it mention anything along the lines of "you can be plural without trauma or a disorder." In fact, there is an entire section about trauma and dissociation linked to DID. Here is literally the FIRST sentence: "In 1930, Italian psychiatrist Giovanni Enrico Morselli described the history, diagnosis, and treatment of his patient Elena, one of the most remarkable cases of DID ever published, highlighting the disorder’s relationship to early childhood trauma". Here is more: "Chronic exposure to trauma can lead not only to acute stress disorder and PTSD but also to one of the dissociative disorders (Spiegel and Cardeña 1991)"

More great quotes: "In a study using positron emission tomography, DID individuals and matched DID-simulating healthy control subjects underwent an auto biographical script-driven imagery paradigm in hypoaroused and hyperaroused identity states (Reinders et al. 2014). As in two previous studies of PTSD dissociative subtypes, Reinders et al. found activation of the rostral/dorsal anterior cingulate, the prefrontal cortex, and the amygdala and insula in the DID group. However, they also found that in DID subjects, the hypoaroused identity state activated the prefrontal cortex, cingulate, posterior association areas, and parahippocampal gyri, thereby overmodulating emotion regulation; the hyperaroused identity state activated the amygdala and insula as well as the dorsal striatum, thereby under modulating emotion. These findings provide further evidence that DID is related to PTSD, because hypo aroused and hyperarousal states in DID and PTSD are similar." "Given the current evidence, DID as a diagnostic entity cannot be explained as a phenomenon created by iatrogenic influences, suggestibility, malingering, or social role taking (Şar et al. 2017). On the contrary, DID is an empirically robust chronic psychiatric disorder based on neurobiological, cognitive, and interpersonal non integration as a response to unbearable stress" DID, OSDD, and dissociation are linked to PTSD and trauma. Endos wiggle their way out of this by claiming not to have a disorder. Well, if you're going to claim you have none of those, you also cannot claim to have its symptoms. They try to wiggle their way out of that as well by claiming that it's not an alter it's "an autonomous entity that can take control of the person at will". What you are describing is an alter, which is only seen in DID and OSDD, or perhaps something related to psychosis, or spirituality/culture practice. Honestly, if you guys just claimed it was a spiritual experience, I wouldn't care as much. I'd still think you are wrong, because I do not believe in spirituality, but I'd understand why you so fervently demand it is so. You do not experience systemhood or alters without some kind of disorder.

Dr Colin Ross is an expert in DID and has said in emails that he believes you can experience multiplicity without trauma or a disorder.

Dr. Eric Yarbrough has said you can be plural without trauma or a disorder, and this was in a peer-reviewed book published by the American Psychiatric Association

Why should we believe you when you say endogenic systems aren't real instead of believing the professionals?

Numerous other experts have also said that endogenic systems aren’t real, so why should I believe these two guys?

I’ve also said numerous times that even if you can be plural without a CDD, you shouldn’t be in CDD spaces or be using their terms. Because they are inherently different. So no, endogenic systems aren’t real, because “system” is a CDD exclusive term.

Why do you people not only choose to actively ignore DNI’s to harass mentally ill people? (And yes, when someone tells you not to interact with them, and you do anyway, that IS harassment, so don’t try it). Why do you have such a problem with traumatized people asking for people not to use their terms for their disability?

It’s giving ableism. It’s giving “we don’t care about your mental health, we need to tell you that you’re wrong.”

Me explaining my stance and my reasoning for it in no way is me trying to force you to believe me. I actually don’t give a rat’s left testicle if you believe me. You are a stranger. You mean literally nothing to me or my life. I just want you fuckers to stay the fuck away from me. So kindly respect that, and fuck all the way off.

#syscourse#endos are ableist#fuck endos#endos fuck off#endos aren’t systems#endos arent punk#endos arent valid#endos aren't real

104 notes

·

View notes

Text

[ID: A picture of a mockup article displayed in CatCo's website. In the top center there is a screenshot of season 1 episode 20 where you can see National City citizens walking through the streets at night while being mind controlled. Atop the image in the left corner there is a red rectangle with white letters spelling 'News' in all caps. Below the image there is another red rectangle with the word News inside it, but this time it's a lighter red and the letters are red. Beside the rectangle in all caps it says, 'National City' in black letters.

Title of the article: What was Myriad?

By Cat Grant May 25th, 2016. The words 'Cat Grant' are red and inside a light red rectangle.

Body of the article: Yesterday National City was attacked. The whole city was mind controlled with a device called Myriad. This device is of alien origin, as Supergirl informs us. It was made with the intention to be used only as a last resource in case of a global crisis. It was made with the intention to save a planet. This planet was Krypton. The culprit of yesterday's attack was a group of rogue kryptonians, their mission to save Earth from humans' self-destructive tendencies.

Myriad works by shutting down the connection between the amygdala and the rostral anterior cingulate cortex. The parts of the human brain that give rise to optimism and hope. Here I quote a citizen about their experience under Myriad: "Under Myriad, I could see, I could hear, but it was like I was a complete stranger to myself." Supergirl's speech saved us all by giving back what we needed the most. Hope. End ID]

#supergirl#kara danvers#cat grant#alex danvers#myriad#catco#season 1#mockup article#catco website#my edit#these are fun to make#already poking at my discord friends to give me ideas to make more#you're welcome to send me some too#don't be shy

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

BPD is a neurobiological illness—a finding that would drastically alter how the disorder should be conceptualized and managed.

MRI studies have revealed the following abnormalities in BPD: • hypoplasia of the hippocampus, caudate, and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex • variations in the CA1 region of the hippocampus and subiculum • smaller-than-normal orbitofrontal cortex (by 24%, compared with healthy controls) and the mid-temporal and left cingulate gyrii (by 26%) • larger-than-normal volume of the right inferior parietal cortex and the right parahippocampal gyrus • loss of gray matter in the frontal, temporal, and parietal cortices • an enlarged third cerebral ventricle • in women, reduced size of the medial temporal lobe and amygdala • in men, a decreased concentration of gray matter in the anterior cingulate • reversal of normal right-greater-than-left asymmetry of the orbitofrontal cortex gray matter, reflecting loss of gray matter on the right side • a lower concentration of gray matter in the rostral/subgenual anterior cingulate cortex • a smaller frontal lobe.

MRS studies reveal: • compared with controls, a higher glutamate level in the anterior cingulate cortex • reduced levels of N-acetyl aspartate (NAA; found in neurons) and creatinine in the left amygdala • a reduction (on average, 19%) in the NAA concentration in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex.

From fMRI studies, there is evidence in BPD of: • greater activation of the amygdala and prolonged return to baseline • increased functional connectivity in the left frontopolar cortex and left insula • decreased connectivity in the left cuneus and left inferior parietal and the right middle temporal lobes • marked frontal hypometabolism • hypermetabolism in the motor cortex, medial and anterior cingulate, and occipital and temporal poles • lower connectivity between the amygdala during a neutral stimulus • higher connectivity between the amygdala during fear stimulus • deactivation of the opioid system in the left nucleus accumbens, hypothalamus, and hippocampus • hyperactivation of the left medial prefrontal cortex during social exclusion • more mistakes made in differentiating an emotional and a neutral facial expression.

DTI white-matter integrity studies of BPD show: • a bilateral decrease in fractional anisotropy (FA) in frontal, uncinated, and occipitalfrontal fasciculi • a decrease in FA in the genu and rostrum of the corpus callosum • a decrease in inter-hemispheric connectivity between right and left anterior cigulate cortices.

Studies have found evidence of hypermethylation in BPD, which can exert epigenetic effects. Childhood abuse might, therefore, disrupt certain neuroplasticity genes, culminating in morphological, neurochemical, metabolic, and white-matter aberrations—leading to pathological behavioral patterns identified as BPD.

There is substantial scientific evidence that BPD is highly heritable— there also is evidence of gene-environment (G.E) interactions (ie, how nature and nurture influence each other).

----

Dialectical behavioral therapy (DBT) was found to attenuate amygdala hyperactivity at baseline, which correlated with changes in a measure of emotion regulation and increased use of emotion regulation strategies.

Of the serotonin receptor genes, polymorphisms in 5HTR2A and 5HTR2C have been most closely correlated with BPD. Variants of the 5HT2A receptor are known to correlate with suicide, affective lability, and impulse control. 5HTR2A polymorphisms correlate with borderline traits.

Moreover, subjects who were homozygous for the HTR2C rs6318 G/G genotype had a higher frequency of the TPH2 “risk” haplotype. Taken together, the data suggest that a TPH2 “risk” haplotype may change serotonin in a way that predisposes to BPD. Patients may be more susceptible to a specific variant of 5HTR2C, which may further contribute to the pathogenesis of BPD.

Carriers of the (oxytocin receptor gene on chromosome 3p25.3) OXTR rs53576 A allele are more likely to perceive others negatively, experience loneliness, and endorse subjective symptoms of psychological stress with correspondingly high cortisol and other stress-related biomarkers. Prosocial behaviors, such as empathy, confidence, and positivity, decrease.

Three studies support the use of oxytocin in the treatment of BPD. Simeon and colleagues16 concluded that oxytocin moderately decreased stress reactivity. Oxytocin decreased threat hypersensitivity, measured via eye fixation and amygdala activity, in response to angry faces. Brüne and colleagues also found reduced attention and avoidant reactions to angry faces in subjects with BPD after oxytocin administration. Their data suggest that oxytocin administration may interfere with trust in patients with BPD, especially in those who have been exposed to trauma.

#bpd#borderline#mental health#personality disorder#neurobiology#emotional regulation#emo#psychology#dbt#dialectical behaviour therapy#therapy#counselling#genetics#oxytocin

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Why Women Have Higher Rates of PTSD Than Men Sexual trauma is particularly toxic to mental health.

The topic of women and sexual trauma has certainly been in the news lately, provoking a great deal of emotion and outrage. Much trauma research focuses on male combat veterans, yet women actually have double the rate of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) as men! While combat veterans have high rates of PTSD and suicide and deserve our attention, so do women sexual assault and abuse survivors. This article will review the symptoms of PTSD, its prevalence in women and men and factors that may contribute to sex differences in PTSD risk, including the types of traumas that women experience, differences in brain processing, coping, and societal reactions.

What are the symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder?

To be diagnosed with PTSD, a survivor needs to have the following symptoms present for at least 1 month and severe enough to interfere with day to day functioning:

Re-experiencing symptoms. These involve reacting as if the trauma is still present, including having nightmares, flashbacks, or frightening thoughts (1 needed)

Avoidance symptoms. These are attempts to avoid being reminded of the trauma, such as staying away from people, places, or things that are similar to aspects of the trauma, or avoiding and shutting out thoughts and feelings related to the trauma (1 needed)

Arousal and reactivity symptoms. These are signs of excess anxiety or anger and physiological arousal, including having angry outbursts, feeling “on edge,” being hyper-vigilant for threat, or having difficulty sleeping (2 needed)

Cognition and mood symptoms. These are negative thoughts, feelings, or judgments relating to the event or memory impairments and include feeling excessive guilt, blaming yourself unreasonably, having difficulty remembering aspects of the event, seeing yourself or the world negatively, or not finding interest or pleasure in regular activities (2 needed).

It is normal to experience some of these symptoms right after an event like a rape or a serious car accident, but if symptoms last for more than a month then you may have PTSD and should seek mental health evaluation and treatment. Sometimes PTSD symptoms can be triggered months or years after the actual event.

What are the rates of PTSD in women and men?

The lifetime prevalence of PTSD is 5-6% in men and 10-12% in women. This means that women have almost double the rate of PTSD as men. Women’s PTSD also tends to last longer (4 years versus 1 year on average). Women are more at risk for chronic PTSD than men. What factors could account for this difference?

Do women experience more traumas than men?

One suggestion for the higher rate of PTSD is that women experience more traumatic events than men. In fact research shows the opposite is true. Women report about a third less traumas than men. This means women are at higher risk of PTSD even though they experience fewer traumatic life events than men on average. This is surprising and suggests there may be something about the type of trauma or women's reactivity that puts them at higher risk.

Do types of trauma differ between women and men?

Research shows that men and women do indeed experience different traumas.

Men are more likely to experience:

combat trauma

accidents

natural disasters

disasters caused by humans.

Women experience more incidents of:

sexual abuse

domestic violence

sexual assault

Sexual traumas are prevalent and particularly toxic to mental health! Sexual abuse typically begins at a young age, when the brain is still growing, leading to a lasting impact on emotion regulation and fear response. About one out of every 6 women has experienced attempted or completed sexual assault or rape in her lifetime. Victims of sexual trauma are more likely to be diagnosed with PTSD than victims of nonsexual trauma. While you might be able to stay away from combat, there is a psychological and relationship cost to staying away from sexual activity or being a reluctant participant (in the context of a committed relationship).

The #metoo movement has highlighted the fact that women in many different career settings experience high rates of ongoing sexual harassment by bosses and colleagues. These experiences of exploitation, besides acting as chronic stressors, may trigger emotions associated with past trauma in women who have been raped and abused. Similarly, events in the news, especially those involving unfair treatment or sexual exploitation of women can trigger strong reactions in the many women who have experienced sexual abuse or assault.

What makes sexual trauma so traumatic?

When I see survivors of sexual trauma in my practice, they often exhibit high levels of fear and vigilance, shame, and self-blame. Sexual traumas carry a stigma and make women feel ashamed even when there is no valid reason to feel this way. Lawyers representing perpetrators often attack the victim's character, lifestyle, and reputation in attempts to get their clients acquitted. Many women who have been traumatized turn to alcohol or drugs to block out feelings associated with the trauma and thereby make themselves vulnerable to further sexual exploitation or coercion. They may report body hatred or dissatisfaction or exhibit eating disorders. Many victims of sexual trauma have trust issues, which can get in the way of healthy relationships as an adult. Some may isolate themselves or become avoidant of romantic relationships.

Women abused as children or teens report feeling too scared or ashamed to tell an adult. Some are not believed or told to “get over it.’ It is difficult to describe the level of violation and loss of sense of a healthy self that sexual abuse and sexual assault can cause to women and men. This is compounded when our society responds with dismissal, minimization, or disbelief.

What other factors might account for the different rates of PTSD?

Women are more susceptible than men to other types of mental health issues like anxiety disorders or depression. These may be the result of sexual assault or abuse, but can also be caused by other factors like genetic vulnerability to depression or high anxious temperament. However, societal attitudes, gender roles, and income inequalities also affect mental health and mood. Women earn less than men for the same jobs. Many women work in jobs or live in households where they have less power and control over their lives than men. This is especially the case in traditional cultures. Professor Norris and her colleagues studied gender differences in PTSD across cultures and found that the increased risk of PTSD symptoms in women was magnified in more traditional cultures.

Do men and women have different brain responses to trauma?

Although more research needs to be done, it is possible that women’s brains react differently to fear-arousing or threatening stimuli than men’s brains. In experimental studies, women showed more activation of the right amygdala, right rostral anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) and dorsal ACC than men when they were exposed to fearful stimuli. The right side of the brain is associated with emotionality in general and negative emotions in particular. These same brain areas are involved in the stress response and also in mind-body awareness and emotional reactivity. Another study using physiological measures showed that women acquired fear more easily than men when exposed to fearful stimuli.

Do men and women cope with stress differently?

Men and women may cope differently with stress. There is some evidence that women are more likely than men to exhibit a “tend and befriend” response to stress. They may react to stress by crying for help, turning to others for social support, or care-taking. Men show more angry and avoidant or problem-solving responses when they are stressed. Because women’s responses are more linked to their social network and availability of support, they may be more vulnerable to PTSD symptoms when they feel lonely or rejected or when social support is not available.

Women tend to show more of an emotional and ruminative response to stress, whereas men are more likely to engage in problem-solving. Ruminating about your stressors can make their impact worse if it stops you from taking action, or if the situation is not controllable. In general, women seem to report stronger emotional reactions to major life events (like death or divorce). Women are also more affected by stressors impacting people close to them, like their parents, friends, partners or children. These coping factors may contribute to women’s higher rate of PTSD, but more research needs to be done. Women who have been raped or sexually assaulted are also likely to blame themselves more and see themselves more negatively, which can exacerbate their reactions to the trauma.

Summary

Research shows that women have higher rates of PTSD than men despite a lower rate of trauma experience. Women’s greater exposure to sexual trauma, sexual coercion, and intimate partner violence plays a role, as well as biological, environmental, and coping factors. When families, social groups, government bodies, news media, or organizations disbelieve, disrespect, or minimize girls' and women's experiences of sexual trauma, this can cause a great deal of harm to mental health.

110 notes

·

View notes

Text