#and latin was a really common language for medieval writing

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Me: Ok I have an important lit test tomorrow I need to be studying

My brain: I wonder if Envy can speak latin

#adrien says stuff#like. Dante and Hohenheim first lived in Ambiguous Ye Old Europe right#and they're both like alchemic geniuses ofc they'd want their kid to read alchemy texts too#and latin was a really common language for medieval writing#so I think probably#fma#fma 03#Envy#wheres that 'im in so deep im just imagining my comfort chara doing random mundane shit' post. me here but im also actively procrastinating

1 note

·

View note

Text

Did the ancient Celts really paint themselves blue?

Part 1: Brittonic Body Paint

Clockwise from top left: participants in the Picts Vs Romans 5k, a 16th c. painting of painted and tattooed ancient Britons, Boudica: Queen of War (2023), Brave (2012).

The idea that the ancient and medieval Insular Celts painted themselves blue or tattooed themselves with woad is common in modern culture. But where did this idea come from, and is there any evidence for it? In this post, I will examine the evidence for the use of body paint among the ancient peoples of the British Isles, including both written sources and archaeology.

For this post, I am looking at sources pertaining to any ethnic group that lived in the British Isles from the late Iron Age through the early Roman Era. (Later Roman and Medieval sources will be discussed in part 2.) The relevant text sources for Brittonic body paint date from approximately 50 BCE to 100 CE. I am including all British Isles cultures, because a) determining exactly which Insular culture various writers mean by terms like ‘Briton’ is sometimes impossible and b) I don’t want to risk excluding any relevant evidence.

Written Sources:

The earliest source for our notion of blue Celts is Julius Cesar's Gallic War book 5, written circa 50 BCE. In it he says, "Omnes vero se Britanni vitro inficiunt, quod caeruleum efficit colorem, atque hoc horridiores sunt in pugna aspectu," which translates as something like, "All the Britons stain themselves with woad, which produces a bluish colouring, and makes their appearance in battle more terrible" (translation from MacQuarrie 1997). Hollywood sometimes interprets this passage as meaning that the Celts used war paint, but Cesar says that all Britons colored themselves, not just the warriors. The blue coloring just had the effect (on the Romans at least) of making the Briton warriors look scary. The verb inficiunt (infinitive inficio) is sometimes translated as 'paint', but it actually means dye or stain. The Latin verb for paint is pingo (MacQuarrie 1997).

The interpretation of vitro as woad is supported by Vitruvius' statements in De Architectura (7.14.2) that vitrum is called isatis by the Greeks and can be used as a substitute for indigo. Isatis is the Greek word for woad; this is where we get its modern scientific name Isatis tinctoria. Woad and indigo both contain the same blue dye pigment, hence woad can be used as a substitute for indigo (Carr 2005, Hoecherl 2016). The word vitro can also mean 'glass' in Latin, but as staining yourself with glass doesn't make much sense, it's more commonly interpreted here as woad (Carr 2005, Hoecherl 2016, MacQuarrie 1997). I will revisit this interpretation during my discussion of the archaeological evidence.

Almost a century later in De situ orbis, Pomponius Mela says that the Britons "whether for beauty or for some other reason — they have their bodies dyed blue," (translation by Frank E. Romer) using virtually identical language to Cesar, "vitro corpora infecti" (Lib. III Cap. VI p. 63). Pomponius Mela may have copied his information from Cesar (Hoecherl 2016).

Then in 79 CE, Pliny the Elder writes in Natural History book 22 ch 2, "There is a plant in Gaul, similar to the plantago in appearance, and known there by the name of "glastum:" with it both matrons and girls among the people of Britain are in the habit of staining the body all over, when taking part in the performance of certain sacred rites; rivalling hereby the swarthy hue of the Æthiopians, they go in a state of nature." In spite of the fact that glastum means woad in the Gaulish and Celtic languages, Pliny seems to think glastum is not woad. In Natural History book 20 ch 25, he describes different plant which is almost certainly woad, a “wild lettuce” called "isatis" which is "used by dyers of wool." (Woad is a well-known source of fabric dye (Speranza et al 2020)).

Of course, "rivaling the swarthy hue of the Æthiopians" doesn't necessarily mean blue. Pliny seems to think Ethiopians literally have coal-black skin (Latin ater). Additionally, Pliny is taking about a ritual done by women, where Cesar was talking about a practice done by everyone. Are they talking about 2 different cultural practices, or is one of them reporting misinformation? Or are both wrong? Unfortunately, there is no way to know.

The Roman poets Ovid, Propertius, and Marcus Valerius Martialis all make references to blue-colored Britons (Carr 2005), but these are literary allusions, not ethnographic reports. As such, they don't really provide additional evidence that the Britons were actually dyeing or painting themselves blue (Hoecherl 2016). These poetic references merely demonstrate that the Romans believed that the Britons were.

In the sources that come after Pliny the Elder, starting in the 3rd century, there is a shift in the terms used. Instead of inficio which means to dye or stain (Hoecherl 2016), probably a temporary application of color to the surface of the skin, later sources use words like cicatrices (scars) and stigma/stigmata (brand, scar, or tattoo) (Hoecherl 2016, MacQuarrie 1997, Carr 2005) which suggest a permanent placement of pigment under the skin, i.e. a tattoo. This evidence for tattooing will be discussed in a second post.

Discussion:

Although the Romans clearly believed that the Britons were coloring themselves with blue pigment, that doesn't necessarily mean that Julius Cesar, Pomponius Mela, or Pliny the Elder are reliable sources.

In the sentence before he claims that all Britons color themselves blue, Julius Cesar says that most inland Britons "do not sow corn [aka grain], but live on milk and flesh and clothe themselves in skins." (translation from MacQuarrie 1997). This is demonstrably false. Grains like wheat and barley and storage pits for grain have been found at multiple late Iron Age sites in inland Britain (van der Veen and Jones 2006, Lightfood and Stevens 2012, Lodwick et al 2021). This false characterization of Insular Celts as uncivilized savages would continue to show up more than a millennium later in English descriptions of the Irish.

Pomponius Mela, in addition to believing in blue-dyed Britons, also believed that there was an island off the coast of Scythia inhabited by a race called the Panotii "who for clothing have big ears broad enough to go around their whole body (they are otherwise naked)" (Chorographia Bk II 3.56 translation from Romer 1998). Pliny the Elder also believed in Panotii.

15th-century depiction of a Panotii from the Nuremberg Chronicle. Was Celtic body paint as real as these guys?

The Roman historians Tacitus and Cassius Dio make no mention of body paint in their coverage of Iron Age British history (Hoecherl 2016). Their silence on the subject suggests that, in spite of Cesar's claim that all Britons colored themselves blue, the custom of body staining or painting was not actually widespread.

Considering all of these issues, is any of this information trustworthy? Based on my experience studying 16th c. Irish dress, even bigoted sources based on second-hand information often have a grain of truth somewhere in them. Unfortunately, exactly which bit is true is hard to identify without other sources of evidence, and this far in the past we don't have much.

Archaeological Evidence:

There are no known artistic depictions of face paint or body art from Great Britain during this time period. There are some Iron Age continental European coins that show what may be face painting or tattoos, but no such images have been found on British coins (Carr 2005, Hoecherl 2016).

In order for the Britons to have dyed themselves blue, they needed to have had blue pigment. Woad is not native to Great Britain (Speranza et al 2020), but Woad seeds have been found in a pit at the late Iron Age site of Dragonby in England, so the Britons had access to woad as a potential pigment source in Julius Cesar's time (Van der Veen et al 1993). Egyptian blue is another possible source of blue pigment. A bead made of Egyptian blue was found at a late Bronze Age site in Runnymede, England. Pieces of Egyptian blue could have been powdered to produce a pigment for body paint. (Hoecherl 2016). Egyptian blue was also used by the Romans to make blue-colored glass (Fleming 1999). Perhaps this is what Cesar meant by 'vitro'.

Potential sources of blue: Isatis tinctoria (woad) leaves and a lump of Egyptian blue from New Kingdom Egypt

Modern experiments have found that reasonably effective body paint can be made by mixing indigo powder either with water, forming a runny paint which dries on the skin, or with beef drippings, forming a grease paint which needs soap to be removed (Carr 2005, reenactor description). The second recipe is very similar to one used by modern east African argo-pastoralists which consists of ground red ocher mixed with cow fat (unpublished interview*).

Finding blue pigment on the skin of a bog body might confirm Julius Cesar's claim, but unfortunately, the results here are far from conclusive. To my knowledge, Lindow II is the only British bog body that has been tested for indigotin, the dye pigment in woad and indigo. No indigotin was found (Taylor 1986).

The late Iron Age-early Roman era bog bodies Lindown II and Lindown III show some evidence of mineral-based body paint (Joy 2009, Giles 2020). Both of them have elevated levels of calcium, aluminum, silicon, iron, and copper in their skin. Lindow III also has elevated levels of titanium. The calcium levels may simply be the result the of the bog leeching calcium from their bones. Some researchers have suggested that the other elements may be from mineral-based paints applied to the skin. The aluminum and silicon may be from clay minerals. The iron and titanium could be from red ocher. The copper could be from malachite, azurite, or Egyptian blue (CuCaSiO4), pigments that would give a green or blue color (Pyatt et al 1995, Pyatt et al 1991). These elements may have other sources however, and are not present in large enough amounts to provide definitive proof of body paint (Cowell and Craddock 1995, Giles 2020). Testing done on the early Roman Era (80-220 CE) Worsley Man has found no evidence of mineral-based paint (Giles 2020).

One final type of artifact that provides some support for Julius Cesar's claim is a group of small cosmetic grinders from late Iron Age-Roman Era Britain. These mortar and pestle sets are found almost exclusively in Great Britain and are of a style which appears to be an indigenous British development. They are distinctly different from the stone palettes used by the Romans for grinding cosmetics which suggests that these British grinders were used for a different purpose than making Roman-style makeup (Carr 2005). Archaeologist Gillian Carr has suggested that these British grinders might have been used by the Britons for grinding, mixing, and applying a woad-based body paint (Carr 2005).

Left and center: Cosmetic grinder set from Kent. Right: Cosmetic mortar from Staffordshire. images from Portable Antiquities Scheme under CC attribution license

The mortars have a variety of styles of decoration, but the pestles (top left and top center) typically feature a pointed end which could be used for applying paint to the skin (Carr 2005). The grinders are quite small, (most are less than 11 cm (4.5 in) long), making them better suited to preparing paint for drawing small designs rather than for dyeing large areas of skin (Carr 2005, Hoecherl 2016).

Conclusions:

Admittedly, this post is a bit off-topic, since the Irish are not mentioned, but dress history is also about what people did not wear. Hollywood has a tendency to overgeneralize and expropriate, so I want to be clear: There is no known evidence that the ancient Irish used body paint.

So, who did? For the reasons I have already discussed, I don't consider any of the Roman writers particularly trustworthy, but I think the following conclusions are plausible:

A least a few people in Great Britain dyed/stained or painted their bodies between circa 50 BCE and perhaps 100 CE, after which mentions of it end. Written sources from c. 200 CE on talk about tattoos rather than painting or staining. The custom of body dyeing/painting may have started as something practiced by everyone and later changed to something practiced by just women.

None of the writers mention any designs being painted, but Julius Cesar's description could encompass designs or solid area of color. Pliny, on the other hand, states that women were coloring their entire bodies a solid color. The dye was probably blue, although Pliny implies it was black. (I know of no plants in northern Europe that resemble plantago and produce a black dye. I think Pliny was reporting misinformation.)

Archaeological evidence and experimental recreations support the possibility that woad was the source of the pigment, but they cannot confirm it. Data from bog bodies indicate that a mineral pigment like azurite or Egyptian blue is more likely, but these samples are too small to be conclusive.

The small cosmetic grinders are suitable for making designs which might match Cesar and Mela's descriptions, but not Pliny's description of all-over body dyeing.

*Interview with a Daasanach woman I participated in while doing field school in Kenya in 2015.

Leave me a tip?

Bibliography:

Carr, Gillian. (2005). Woad, Tattooing and Identity in Later Iron Age and Early Roman Britain. Oxford Journal of Archaeology 24(3), 273–292. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0092.2005.00236.x

Cowell, M., and Craddock, P. (1995). Addendum: Copper in the Skin of Lindow Man. In R. C. Turner and R. G. Scaife (eds) Bog Bodies: New Discoveries and New Perspectives (p. 74-75). British Museum Press.

Fleming, S. J. (1999). Roman Glass; reflections on cultural change. University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, Philadelphia. https://www.google.com/books/edition/Roman_Glass/ONUFZfcEkBgC?hl=en&gbpv=0

Giles, Melanie. (2020). Bog Bodies Face to face with the past. Manchester University Press, Manchester. https://library.oapen.org/viewer/web/viewer.html?file=/bitstream/handle/20.500.12657/46717/9781526150196_fullhl.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

Hoecherl, M. (2016). Controlling Colours: Function and Meaning of Colour in the British Iron Age. Archaeopress Publishing LTD, Oxford. https://www.google.com/books/edition/Controlling_Colours/WRteEAAAQBAJ?hl=en&gbpv=0

Joy, J. (2009). Lindow Man. British Museum Press, London. https://archive.org/details/lindowman0000joyj/mode/2up

Lightfoot, E., and Stevens, R. E. (2012). Stable Isotope Investigations of Charred Barley (Hordeum vulgare) and Wheat (Triticum spelta) Grains from Danebury Hillfort: Implications for Palaeodietary Reconstructions. Journal of Archaeological Science, 39(3), 656–662. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2011.10.026

Lodwick, L., Campbell, G., Crosby, V., Müldner, G. (2021). Isotopic Evidence for Changes in Cereal Production Strategies in Iron Age and Roman Britain. Environmental Archaeology, 26(1), 13-28. https://doi.org/10.1080/14614103.2020.1718852

MacQuarrie, Charles. (1997). Insular Celtic tattooing: History, myth and metaphor. Etudes Celtiques, 33, 159-189. https://doi.org/10.3406/ecelt.1997.2117

Pomponius Mela. (1998). De situ orbis libri III (F. Romer, Trans.). University of Michigan Press. (Original work published ca. 43 CE) https://topostext.org/work/145

Pyatt, F.B., Beaumont, E.H., Buckland, P.C., Lacy, D., Magilton, J.R., and Storey, D.M. (1995). Mobilization of Elements from the Bog Bodies Lindow II and III and Some Observations on Body Painting. In R. C. Turner and R. G. Scaife (eds) Bog Bodies: New Discoveries and New Perspectives (p. 62-73). British Museum Press.

Pyatt, F.B., Beaumont, E.H., Lacy, D., Magilton, J.R., and Buckland, P.C. (1991) Non isatis sed vitrum or, the colour of Lindow Man. Oxford Journal of Archaeology, 10(1), 61–73. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/227808912_Non_Isatis_sed_Vitrum_or_the_colour_of_Lindow_Man

Speranza, J., Miceli, N., Taviano, M.F., Ragusa, S., Kwiecień, I., Szopa, A., Ekiert, H. (2020). Isatis Tinctoria L. (Woad): A Review of Its Botany, Ethnobotanical Uses, Phytochemistry, Biological Activities, and Biotechnical Studies. Plants, 9(3): 298. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants9030298

Taylor, G. W. (1986). Tests for Dyes. In I. Stead, J. B. Bourke and D. Brothwell (eds) Lindow Man: the Body in the Bog (p. 41). British Museum Publications Ltd.

Van der Veen, M., and Jones, G. (2006). A Re-analysis of Agricultural Production and Consumption: Implications for Understanding the British Iron Age. Vegetation History and Archaeobotany, 15 (3), 217–228. doi:10.1007/s00334-006-0040-3 https://www.researchgate.net/publication/27247136

Van der Veen, M., Hall, A., and May, J. (1993). Woad and the Britons painted blue. Oxford Journal of Archaeology, 12(3), 367-371. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/249394983

#cw anti-black racism#romano-british#period typical bigotry#iron age#bog bodies#no photographs of bog bodies though#roman era#ancient celts#celtic#woad#insular celts#anecdotes and observations#body paint#brittonic#archaeology

39 notes

·

View notes

Note

Do you think anyone is left handed? XD ooh, how does their handwriting look like? I have a hc that Aaron has dysleyia and thus never learned how to read fluently. But he still likes to read sometimes x) What are yours?

How do boys write?

Hi! How are you? I hope you are well! ^^

Here is the headcanon you requested, I hope you enjoy it! ^^

I like the idea of Aaron being dyslexic. What's more, I doubt he learned to read and write as a child. It wasn't common at the time and Aaron was born at a rather complicated time in medieval history (between war, famine and a plague that had been over for a few decades but still had consequences). So I doubt that his little mother would have found the time, money and opportunity to teach him to read and write (although she would have had to know how to read and write herself, and given the literacy rate among women at the time, that's highly unlikely). Aaron must surely have learned to read and write later, perhaps by joining his wolf pack.

Dyslexia would probably not have been detected, not only because the word didn't exist, but also because someone who had difficulty reading and writing wouldn't have seemed surprising.

However, Dyslexia could be detected at the manor. If Ethan has any knowledge on the subject it would be possible. If not, with a dyslexic MC themselves. I think that would be the most coherent because I can't think of any reason why Ethan should have been interested in the Dys disorder.

Take care of yourself and have a nice day! ^^

Vladimir :

Vladimir is right-handed, but he can write with his left hand if necessary. His handwriting is not disastrous with his left hand, but it is even slower than when he writes with his right hand.

His handwriting is beautiful and neat, but he writes very slowly, even when he's in a hurry. This is because he needs to concentrate a lot to have a neat handwriting. If he tries to write faster his handwriting tends to become illegible (something his teachers used to reproach him for when he was a child (while asking him to write faster)).

He writes quite small. As a result, he generally doesn't take up much space on a sheet of paper. His letters are very tight and his handwriting tends to lean to the left of the page. He can write in Braille. He learnt it so that he could talk to Raphaël when they were still exchanging letters.

He always signs with his surname, which is rather unusual for a vampire given that the majority of them only sign with their first name, but Vladimir is incapable of not using his, it's far too important to him to give it up.

He is the one in the manor who masters the most different languages, especially when it comes to the written word (this is due to his education). He can easily read and write texts in French, English and Italian, as well as German, Hungarian and Latin. He makes very few spelling mistakes in these languages and is usually the one to go to if someone has a grammatical or spelling question. He can also read Old English. He also reads Russian and Ancient Greek easily (although with a little more difficulty for the latter).

As he is very clumsy, writing requires a lot of concentration (he probably suffers from dyspraxia but has never been diagnosed for this). But that doesn't mean he doesn't enjoy writing. In fact, he loves writing. The other members of the manor have already offered to buy him a typewriter so that he can continue to write his stories with less fatigue, but Vladimir thinks that the quality of his writing is not worth the expense.

Béliath :

Béliath is right-handed. He can write with his left hand if he really needs to, but in that case he writes very badly, much to his dismay. So if he gets injured and can no longer use his right hand, he will usually ask others to write for him (and the best choice is Ivan or Vladimir).

Béliath writes mainly in cursive and his handwriting is quite ancient. He's not particularly aware of it, because that's how his sister taught him to write, several centuries ago, and he's never thought of changing the way he writes, even less since the people at Moondance have been complimenting him on the beauty of his handwriting. It's true that his handwriting is very pretty and rather neat, and the letters are spaced far enough apart not to be unpleasant to read. He sometimes boasts about it to the others at the manor, and it has to be said that he easily has one of the most beautiful handwritings.

He writes rather quickly (no doubt because of the invitations to his parties, which he has to write by hand since Vladimir refuses to buy a computer and a printer), while keeping his handwriting legible for everyone. His handwriting tends to lean to the right of the page.

Its writing is neither too small nor too large. The letters are easy to read and different enough not to be confused with each other when reading.

Like most vampires and supernatural creatures, he signs with his first name. He doesn't really have a surname anyway, unless you consider Son of Asmodeus to be a family name. His signature is rather complex, with a lot of interlacing around his first name, which makes for a rather complicated signature to reproduce.

He can write in several different languages with varying degrees of spelling ability. He has a perfect command of the demonic language his sister taught him, he can write in Latin and his French and English are not bad (if you ignore the fact that he never uses accents in French). As for the rest, he generally speaks them much better than he writes them.

Ivan :

Ivan is right-handed and can't write with his left hand. It's illegible every time. He tries to practise, though, because he thinks it's cool to be able to write well with both hands, but he can't really do it. If he gets injured and can't write with his right hand, he'll try to write with his left before giving up and asking Vladimir or Beliath for help.

His handwriting is simple, not pretty, but perfectly legible for everyone. It's a quality he really appreciates, because Aaron has already told him that he prefers his handwriting to Beliath's. Ivan has rarely been so proud of himself, after all, everyone in the manor recognises that Beliath's handwriting is pretty.

He can write quickly when he needs to, but this affects the legibility of his handwriting, so he avoids doing so most of the time. He also has a tendency to write quite large, which means that he generally needs a lot more paper to write a text than the other members of the manor.

He has asked Vladimir and Raphaël to teach him to write and read in Braille. He still wants to be able to communicate with Raphaël, even if he leaves the manor, and he would like to be able to read the little stories that Raphaël writes himself and not always have to ask Raphaël to read them for him. He still has a bit of trouble reading quickly, but he's getting better at it, although writing in Braille is still very difficult for him.

He has kept the signature he had before his death, so he continues to sign with his surname, signing with his first name seems strange and… unpleasant. It's not that he doesn't like his first name, but he thought he'd be using his family name signature for decades to come, and having to give it up so soon is still too painful for him.

He can only write in French, although Vladimir persists in trying to teach him at least English (at first Vladimir wanted to teach him Latin). Ivan makes relatively few spelling mistakes (which he's proud of, given that Ethan makes more spelling mistakes than he does in French).

Aaron :

Aaron is normally left-handed, but at the time he was born it was very much frowned upon. So he was forced to learn to use his right hand to work, write and fence, which didn't help his handwriting, which was already difficult to read, and he was much more awkward using his right hand to fight with a sword. Today, he has stopped using his right hand for writing and fencing and has become much more skilful.

He had to concentrate to achieve a beautiful handwriting. The shapes of his letters are simpler than Beliath's because he favours ease of reading over beauty. He also writes quite slowly and never tries to write faster. He knows that writing faster only makes his text more illegible.

Like most supernatural creatures, Aaron signs with his first name. His signature is quite simple, and he sees no point in trying to embellish it with interlacing or lines. For him, it's a waste of time and doesn't fit in with his idea of a signature that should remain legible. After all, with all the interlacing that Beliath puts around his first name, he sometimes finds it hard to read his signature.

Aaron speaks far more languages than he writes, particularly Elvish, and is the only member of the manor to do so. He has a tendency to make a lot of spelling mistakes, but in his defence, between language changes and spelling reforms, he never knows where to turn. He barely has time to understand a spelling rule before humans are happy to change it straight away. He only spells Spanish. For the rest, he always asks Vladimir.

Despite the difficulties, Aaron loves to write and read poetry. Along with Raphaël, he probably owns the largest number of poetry collections. However, he is quite precise about the books he looks for: the text must not be too small and the lines must be spaced far enough apart to be pleasant to read. That's one of the reasons why he doesn't really like Vladimir's old books: the writing is too small and he has a hard time distinguishing between the lines.

Raphaël :

Raphaël is totally ambidextrous, but as a child he was left-handed. His parents insisted that he write with his right hand, but he didn't really want to, so as soon as they weren't watching him he would write with his left hand again. He eventually learned to use his right hand for writing and fencing, but this was only to surprise people who thought he was only left-handed.

When Raphaël was writing in cursive, he loved writing poetry, especially for Margarita and Alessio, who regularly received poetry from Raphaël. He still loves to write, but now he uses a slate and stylus to write in Braille. In fact, he always carries a slate and stylus with him in case he needs to write down an idea somewhere other than his bedroom or the library. The problem is that he always ends up forgetting the paper somewhere.

He found Braille much easier to learn to read than to learn to write. This is because to write braille text, you have to write it the other way round, as the dots are made on the back of the page. It wasn't at all instinctive at first and he got it wrong more than once. Now he's quite happy to be teaching Ivan to write in Braille.

He always signs with his first name and his signature hasn't changed much, but it's still complex to reproduce. There is a lot of interlacing around his first name and the capital R is huge compared to the other letters.

He likes to exchange messages with Vladimir and Ivan, as only the three of them can read them, they usually use them to prepare surprises for the others or to complain that so-and-so has forgotten to clean up again or that Ethan keeps slamming doors.

Raphaël is not bad at spelling and grammar, not as good as Vladimir, but unlike Vladimir, he doesn't read grammar books for pleasure. He can speak more languages than he can read and write. But he reads and writes easily in English, Latin, Italian and French.

He reads a lot, and is one of the biggest readers in the manor. When he first arrived, he only had Braille books, which limited his reading possibilities because they were big books and didn't always cover the subjects that interested him. The arrival of Ivan, introduced him to audio books. He listens to a lot of them now, especially romance novels, and loves the fact that he can listen to books while lying comfortably in bed or cooking.

Ethan :

Ethan is left-handed and he really can't write with his right hand. It has to be said that it never occurred to him to try, and his parents never tried to force him to write with his right hand either. If he gets injured and can no longer write with his left hand, he always asks Beliath to write for him.

Ethan's handwriting is not legible. His "a's" look like "e's" or "o's", his "u's", "i's" and "n's" also look very similar, he never dots his "i's", so they can also be mistaken for "l's", and when he writes in French, he doesn't use the slightest accent, whereas he does in Finnish. It's an ordeal for everyone in the manor to reread what he's written, and Aaron doesn't even try anymore. The only one who manages to read it is Beliath.

He writes very small, which doesn't make it easy to read his handwriting, and he also writes quite quickly. He doesn't like writing anyway, his texts are full of abbreviations and drawings to speed things up, and he's the only one who can decipher the notes he takes. If he can do maths for the sake of doing maths, sitting down to write is an ordeal for him. He doesn't have the patience for it.

Like most vampires, he signs with his first name, a habit he picked up fairly recently after arriving at the manor. His signature is rather simple, with few lines and no interlacing, he framed it with just two lines. The main thing for him was that it was quick to make.

He is quite good at spelling, although his handwriting is not very legible. He writes and reads texts easily in Finnish, English, German and French. He can also read a simple text in Latin… if he has no choice, really, no choice.

He has no idea why everyone finds his handwriting difficult to read. He finds that what he writes is always perfectly legible.

Neil :

Neil is right-handed. He can write with his left hand, he even writes quite well, but he doesn't feel comfortable with it at all. So he will always write right-handed unless he really has no choice.

He's always had a nice handwriting, and that's even truer now that writing has become easy and enjoyable. Before, writing wasn't really something that could be described as enjoyable, given the difficulty of the task. He generally prefers to use a beautiful fountain pen for writing, and doesn't hesitate to buy the most expensive ones. He always has one with him in a small box and several in his desk drawers, and tends to change fountain pens according to his mood.

He always writes in a cursive script that looks rather ancient. There is a lot of curl, especially in the capital letters. His letters are easy to distinguish from one another and the words are spaced far enough apart not to give the impression that the text is cramped. His handwriting always leans very slightly to the right.

His signature is elegant and simpler than his usual handwriting. He always signed with his first name.

He has the impression that the rules of spelling and grammar are constantly changing, as are the meanings of words. He tries to follow them, though, because he doesn't like making mistakes, but he gets tired of constantly having to unlearn what he's learned.

The language he knows best is still Irish, and although he has completely lost the habit of speaking Old Irish, he can still read it easily, as well as Middle Irish and Modern Irish.

He also reads and writes in many other languages without difficulty. The languages he knows best apart from Irish are: English, Greek and Ancient Greek, Latin, French, as well as German, Italian, Spanish and Scottish Gaelic. He can also read and follow a simple discussion in Arabic, Mandarin and Russian. To his dismay, knowing so many languages is more of a problem than anything else, and he tends to switch languages when he can't find the right word in the one he spoke before, which means he loses most of the people he's talking to.

Léandra :

Léandra is left-handed. However, she can write with her right hand if she needs to. Before teaching Beliath to write, she had never written with her right hand. She forced herself to write with her right hand, seeing that it was the one her little brother used all the time; she wanted it to be easier for him to copy her movements that way.

She doesn't really take care of her handwriting. However, if she forces herself, she can have very pretty handwriting, but it's not something that interests her. For her, writing has to be practical before it's pretty; she writes to get a message across or to give information, so she doesn't really see the point of trying to turn it into a work of art.

Léandra is used to writing fast and big. She doesn't think writing should take up too much of her time. In fact, she's never understood how her little brother could enjoy spending so much time writing beautiful letters.

She always signs with her first name and her signature is quite complex. There's a lot of interlacing that surrounds her, like a shield around her signature.

She is quite good at spelling, having taught Beliath to read and write in several different languages, including the demonic one.

She is fluent in several different languages, written and especially spoken. She can write and read demonic, English, Italian and Latin texts with ease. For the rest, she much prefers an oral discussion. This is not to say that she would be unable to write in other languages, just that she sees no point in learning their spelling if she can manage in an oral discussion.

Farah :

Farah is right-handed, but she can write with her left hand if she has problems. However, this affects the quality of her writing, which is harder to read.

Her handwriting is simple but neat. Her brother taught her to write, shortly after they left home. She's happy to be able to read and write, of course, but writing has never been an activity she's been keen on: sitting down for several minutes to write a letter always seems horribly boring to her. Whereas reading, may not be her favourite thing to do, but she'll never turn down a new book, especially a fantasy one.

Her letters are mainly in block letters, as she finds cursive writing too time-consuming. She generally writes fairly large and fairly quickly.

Her signature is very simple: she signs only with her first name, without adding the slightest line or interlacing around it. She clearly doesn't see the point and doesn't want to spend any more time signing than she has to.

As she has travelled a lot with her pack, she speaks and reads a lot of different languages, but this is less the case when it comes to writing. In any case, she doesn't always have the necessary writing materials with her and she always loses her notepads or pens when she does have them. She can write Latin and Spanish fairly easily, but the rest is much more complicated. She rarely masters the written word in other languages, even though she can read them. For example, she can read texts in English, Italian and French without being able to write in those languages. And although she can hold a discussion in Arabic, Swedish and German, she is unable to read or write a text in these languages.

#Moonlight lovers#Moonlight lovers Vladimir#Moonlight lovers Béliath#Moonlight lovers Ivan#Moonlight lovers Aaron#Moonlight lovers Raphaël#Moonlight lovers Ethan#Moonlight lovers Neil#Moonlight lovers Léandra#Moonlight lovers Farah

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

Castlevania Language Headcanons

I spoke about language in Castlevania before. Like most media the series mostly just shrugs off the entire language barrier. People are just magically able to communicate. No matter from how far apart they actually are.

But personally I find it interesting to think about what languages the characters realistically would have spoken or been able to speak.

Trevor would probably mostly just know Romanescu (old Common Romanian). A language I might note that is a bit different than modern day Romanian, as it had a lot more slavic bits in there, than the modern language does. He might also have known bits and pieces of old Hungarian and Common Turkish, given the political situation at the time. Though I kinda doubt he would've been fluent. I do assume that his family once upon a time would have taught him Latin and Ancient Greek, but I doubt he would remember a lot of that.

Alucard meanwhile would probably know at least the ancient languages. I see Dracula as very intrested in teach him. So, I got to assume that Alucard will know Romanescu, Latin, Ancient Greek, but probably French, Hungarian, Turkish and maybe some Arabic as well.

Sypha seems to canonically just know all the languages. Given the effort was made to cast her with an Hispanic actress and having her speak with a Spanish accent, I assume Spanish is her mother tongue, but she clearly also speaks Romanescu and seems to at least be able to read a write a plethora of ancient languages. Given the fact she has travelled a lot, I will also just assume that she knows a lot of current languages at the time. Probably enough to understand most languages spoken in Europe.

It do assume the trio will use Romanescu to communicate with each other.

Assuming that Dracula is in this timeline still Mathias from France, he will speak Old French, though the question remains whether he understands the Middle French spoken at the ime the series takes place. I do assume though. Given his entire think with knowledge and his almost obsessive collection of it, I just am going to assume he has learned a lot of languages throughout his life, probably being able to at least understand most languages spoken throughout Europe and Asia.

Lisa probably only knows Romanescu, when she arrives at the castle. Maybe some Latin, if she had tried to learn some medicine before. I am going to assume, though, that Vlad is gonna do some work polishing her Latin and Greek at least.

Still assuming, though, that they are going to hold most conversations in Romanescu.

Hector and Isaac are a bit more complicated, of course. Because we know little about them.

It stands to reason, that Hector's mother tongue is Greek (given he grew up on Rhodes) and Isaac's is Arabic. Given he has probably consumed quite a lot of ancient texts and texts about alchemy, I think Hector will at least be able to read and write in old Greek and Latin. I also am going to assume that under Dracula he learned some Romanescu? He might also know some Turkish, given that during his childhood Rhodes was under Turkish control.

Isaac is a bit more complicated, because canonically we do not really know where he got enslaved and what not. In my headcanon I went with him being dragged all the way up to Italy, so he speaks Italian. Given he was a slave in a monastery and tried to help, I assume he knows Latin as well (and quite frankly, learning Latin, when you know medieval Italian is not that hard). I have him end up in Greece, due to the ongoing conflict with the Ottoman Empire, after he escapes. Hence, he speaks Greek as well.

Meaning that in all my Isaactor stuff, the two communicate a lot in Greek.

Given they end up in Austria, though, they do learn German soon enough. Speaking of which...

The sisters are interesting in regards to their lannguages.

Now, Carmilla very probably is from Austria and always has been from there, so she would speak Old High German as her mother tongue. Given she was a vampire for a while, she probably learned a few languages, though. I gotta assume she knows Latin at least, especially given that at the time Latin was kinda the official language of politics in many regards. I am gonna assume she knows at least some Italian, Old French and Hungarian, too.

As I explained before: I assume that Lenore originates in Scotland. But given she was taken from her family as a child, she knows very little in terms of Scottish Gaelic and for the most part her mother tongue is old English. Given she was nobility, she has learned Latin, too. She also is the diplomat of the group, so I gotta assume she knows quite a few other languages as well, just to keep up her position. Very certainly Romanescu, too, given it is Vlad's main spoken language and he seems to be the big boss of vampires.

Morana, of course... Honestly, I am just gonna assume she knows all the languages. The woman is more than a millennium old. Depending on whom you ask even older than two millennia. She had the time to travel. She knows all the ancient languages for certain and if she knows Akkadian, Persian and Phoenician the other languages springing from that will be easy. I have her travelling Asia, too, so she kows at least Hindi, Chinese and Japanese as well.

Striga is a bit more interesting. She speaks with a Slavic Accent and her voice actress is from Croatia. Which made me put Striga there, too. She has to have travelled a bit. And of course she will probably speak Old High German with the sisters. I kinda want her to have learned old Akkadian to speak that language with Morana. Because that would be sweet.

I am going to assume that in everyday life the sisters speak Old High German with each other.

I am also going to assume that Lenore, to woe Hector, is gonna speak Greek with him.

52 notes

·

View notes

Text

Latin Composition Part 1: prose, style and tone

Link to the masterpost with other parts

Here’s a guide to taking the first steps. It's about speaking but the principles are the same. Start with basic stuff and short sentences. Don’t worry about being grammatically correct. Just get used to having a steam of consciousness in Latin.

It may behoove you to pay attention to vowel length as you’re writing. It’s not essential but good to start building that now if you’re not used to it yet.

If you’ve never produced Latin writing before, read this blog post about how to build up to it. It’s about speaking, but the principles are about the same. It’s particularly nice because it gets you used to the common vocabulary, not just the elementary vocabulary.

If you’re already in the habit of producing prose, try to write stories! Maybe it’s summaries of a TV episode you just watched or retellings of fairy tales. Really, it can be whatever you want. I know a guy who would write an annal every time he finished a year in Crusader Kings II.

Up til now, we’ve been mostly doing “mechanical” writing. That is, just getting used to creating Latin words that make sense. If we want to do poetry well, we ought to start understanding how tone and style work. For this I highly recommend checking out the Gesta Romanorum [student notes] [big collection] and other such medieval fables (Odo de Cheriton is a favorite of mine; there’s also this incredible collection). After you’ve read some, think about the “feel”, tone, style, and subject-matter of these stories and try to imitate it. What are the stories’ conventions? How are you using them? How are you suberting them? What’s bothering you and how can an allegorical story help you express your point better?

If you’re not quite getting a sense of style yet, try reading some Medieval Latin from other genres. I highly recommend the Gesta Francorum, the Vulgate Bible, the Navigatio Sancti Brendani, and Historia Karoli Magni et Rotholandi. read a lot of Medieval Latin in general. It’s usually far more simple than the great monuments of antiquity and so you get a better sense of Latin.

When I’m saying “read” I mean understanding Latin as Latin, not as translation. This is definitely tough especially given how most people were taught Latin. Translation may occur reflexively, but try to avoid it intentionally.

My best recommendation is to read a passage 3 times. Firstly, get some context. Then read the passage without stopping. That is, don’t stop for stuff you don’t know. Just try to get a broad sense of what you know. Basically just the shape of the passage. Then, go back through and establish meaning. That could be checking dictionaries, confering with an English translation, or whatever. Get a sense of how things are working mechanically here. This is also called intensive reading. Finally, read it through a third time fluidly (also called extensive reading).

If you’re finding a text still impenetrable, don’t worry! Check out learner novellas. They’re written with very limited vocabularies so you get a lot of vital reps with words. Also check out tiered readers. These are great for building circumlocution skills. Quality can vary, but that’s mostly fine. Language fossilization is a myth and the benefits far outweigh any aesthetic issues.

Get in touch with your feelings! Pay attention to the tone and rhythm of the story. Without looking up statistics or anything, try imitating the author you just read by writing a short passage. It could be on anything.

Some prose authors I think have really strong style and tone (of varying difficulty): Tacitus, Seneca (particularly Apocolocyntosis), and Caesar (if only as a baseline to compare the others).

If you’re good at poetry, give Catullus’ poems a read. Also, compare Ovid to Tibullus. Compare Aeneid to Georgics.

Part 2: Haikus

1 note

·

View note

Text

Language and Cat Quest 2

More world building stuff, yippee!

So, something I think about a lot when writing +and thinking about) my fic is language. We're working with two different countries here, there has to be at least some difference in how they use language. And there's one side quest that makes me believe they have completely separate languages.

Side Quest: Felinguard's Statue - Rivals of a Kind

(Cat) Peasant: Heya! You ain't afurraid of water, are you? Wanna help me win an epic deathmatch?

(Cat) Peasant: Lookit that dog over there!!

(Cat) Peasant: We've been tryna chase the other off! If only I could swim over there! And he keeps barkin' at me like I understand him- Wait. Are you... a dog?!

(Cat) Peasant: Uhhhh.... OH! You can translate this note I scratched out!! Read it out to him! It'll make him pounce away in tears!

The dialogue here at the start of the quest implies a language barrier (it also implies the two peninsulas where the kingdoms are closest really are as close as they appear on the map), and that common folk are unable to understand each other.

So this gives us at least two languages within the game: Felinguard's native language, and the Lupus Empire's. But then, how are our protagonists able to communicate with each other? Now they don't actually have any dialogue to fill the role of 'silent' protagonist, but we do know they can speak. Both due to Lioner and Wolfen speaking and the fact that they do communicate with people. We just can't see what they're saying. So... How do they talk to each other?

Now, it's possible they know the other's native language, but with the tension between the kingdoms it seems unlikely that they know very much. So, I propose a third language: Latin (or this world's adjacent).

This story takes place in a medieval adjacent world (they have hot dogs for crying out loud, it can't be completely medieval), and based on my limited knowledge of the middle ages (mainly from books set in that time) I'm pretty sure Latin was still in use, though limited to those of high status. It doesn't seem too unlikely to me that our protagonists (and Lioner and Wolfen), who are kings, would know a sort of universal language. I imagine that's how they communicate with each other throughout the game, and translate for each other their native language (and I like to imagine that they begin learning the other's language at some point, seeing how often they move back and forth between the kingdoms. It would be helpful for both kings to understand what's being said so interactions go smoothly).

But, it can't just be them that know it, right? I imagine other nobles can use Latin, too, and folks that have (or had) important roles within the castle.

Here's a list of characters that I suspect are able to communicate with Latin to some extent (plus why I think so)

Kirry (he's supposedly both kings' royal advisor, and at least their guardian spirit. It would be kinda bad if he could only talk to one of them.)

Kit (she's been alive for a very long time, I wouldn't be surprised if she learned at some point. Not to mention she directly addresses Canis and he understands easily. Though it's also possible she just knows the Lupus Empire's native language, considering she was friends with Hotto, and how in the first game it mentions she takes commissions from there.)

Hotto (similarly, he's been around a while, and had to be able to communicate with Kit and Felinguard somehow.)

The imposter head towncat of South Pawt (he and the other dog soldiers invaded, even of they don't know Latin, had to have learned Felinguard's language to stay undercover. Though he also addresses Canis directly, and knowing the Lupus Empire's language as a 'cat' would be suspicious.)

Dr. Jekkit (okay this one is just self indulgent because I love her lol, but it does seem like she directly addresses Canis.)

The Doge Knight (he's a noble, even if be doesn't act like it lol. I imagine he has at least a limited understanding of Latin)

Purrivate Mewman (he's a spy lol. Even if he doesn't knock Latin, he definitely knows the Lupus Empire's language. Otherwise he wouldn't be a very good spy)

There's probably more that I'm missing, but I'm running out of time to write this and if I keep reading the dialogue I'll get distracted lol

Still, even if it's not touched upon very often in the game, I think the concept of a language barrier between the two kingdoms is interesting :) (it's certainly something I plan on touching on in my fic lol. Especially with some of the ocs I have.)

1 note

·

View note

Text

Worldbuilding: Brush Talk

Here’s an interesting bit that doesn’t seem to occur to a lot of writers: just because two characters don’t share the same spoken language, doesn’t mean they can’t talk. Historically, a lot of communication can be done by people writing at each other. In large areas of Medieval and Early Modern Europe, this was done in Latin and Greek. In Northeast Asia, if you knew Chinese characters, you could make yourself understood to educated people in China, Japan, Korea, Vietnam, and much of Manchuria. Paper, ink, and pen or writing brush, and you could talk to each other.

For example, the word we use in English today, “Japan”, comes from the characters 日本, pronounced Nippon or Nihon in Japanese, Riben in Mandarin, and Ilbon (일본) in Korean.

(I’m still not sure how Marco Polo got Cipangu out of that, but then our best evidence is that he was speaking Mongolian, getting information on Kublai Khan’s invasions of Japan second or third-hand, and then translating that into Venetian decades later, and who knows how that much verbal distance mangled it.)

I just find it neat that, instead of Daring Linguists who speak a dozen languages (though those existed), a lot of communication happened by people... effectively emailing each other across the table. Or across continents, sometimes, by letters. And that might allow people to converse for years before they ever met each other, and still meet, even without speaking a common tongue. It’s like arranging a geeky get-together with your friends from around the country, or possibly even around the world; “Hey, everyone want to meet up at that awesome noodle place on Phoenix Street on New Year’s? Sending this out now so people can RSVP!”

You could easily use this in fantastic fiction to have a group pulled together who don’t really know each other. Some of them could be the scholars and doctors exchanging letters, some relatives and bodyguards, some clients or patrons coming along out of curiosity or determined not to let someone out of their sight. Because they’re geeks, and if you let them wander they can get into so much trouble....

#creative writing#worldbuilding#linguistics#chinese history#korean history#japanese history#medieval history#characters

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

I despise of the long-standing misconception that people in the past, particularly the Medieval period, couldn't read or write. It's horseshit.

Literacy estimations from the past are extremely flawed, because they were based on how common books are in archaeological finds from the area. Not only does this idea kind of crumble when you ask "Hey, why would everybody who can read need to own books?" it's also patently ridiculous because books at the time were primarily printed in Latin (and other languages used by the Church)

Basically it's like surveying 50 modern Americans on whether they own any Russian books and concluding "Only 2% of the US population is literate!" Of course commoners in Medieval England didn't own any Latin books, they couldn't read Latin, they could read English.

We actually have evidence of how widespread literacy was among the common population around this time in Europe. The most interesting of this is the birch bark letters found in Novgorod, which preserve hundreds of notes written in a vernacular dialect between average, everyday folks. The existence of these letters seems to imply that literacy levels were very high in Novgorod during this time. Most famous among these are the homework done by a child named Onfim, who had a habit of doodling on his pages. Personally, I'm partial to this one:

From Boris to Nastas’ja – As soon as this letter arrives, send me a man on a stallion, because I have a lot of work here. And send a shirt; I forgot a shirt.

There is nothing more human in this world than writing a letter to your wife asking her to send you some shit you forgot at home because you're a dumbass but you really need it, please can you send that guy with the stallion?

#we are all the same at heart 🥲#and yes they could read! ughhhh#what's funny is there's that whole thing in the beauty and the beast remake about how everybody thinks belle shouldn't be able to read#and like NO! STOP! STUPID FUCKING MOVIE! READING WAS NORMAL AND EXPECTED FOR WOMEN IN THAT TIME PERIOD YOU DUMB MOTHERFUCKERS!#hhhhhhhh#incoherent rambling

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

Is Gendry illiterate?

Short answer: Probably not.

Long answer:

I’ve noticed a lot of fanfiction trying to address Gendry’s illiteracy once he becomes a noble. Most fics depict him as being completely illiterate. Some depict him as having some level of literacy, but not enough for his new position. So let’s try to figure it out, shall we?

Part 1: Literacy

We have this assumption that in medieval times no one could read or write unless they were part of the nobility. That is not quite true. Firstly, we have to understand what it meant to be literate by medieval standards:

“In Medieval times, “Literate” actually meant able to read and write in Latin, which was considered to be the language of learning. Being able to read and write in the vernacular wasn’t considered real learning at all. Most peasants prior to the Black Death (which really shook up society) had little chance to learn - hard labouring work all of the hours of daylight does’t leave a lot of energy for reading or writing.

It’s worth noting, however the panic amongst the ruling classes when translations of The Bible started to appear written in English. This really started in the late 14th Century (about 30 years after the Black Death). The level of panic suggests that the Ruling Classes knew that the numbers of people who could read and write English was far greater than the numbers who could read Latin.”

However, there is no language quite like Latin in Westeros. The closest we come to something similar is High Valyrian. Which noble children seem to have a basic understanding of. We can safely assume that Gendry doesn’t have extensive knowledge of High Valyrian - so he is illiterate in that regard. But I don’t think High Valyrian is as widely used as Latin was in the Middle Ages. It’s also not a language with religious significance. As the Faith of the Seven doesn’t use High Valyrian the way that the Catholic Church used Latin.

So… taking that into account. What I assume that is meant by “literate” in Westeros is being able to read and write in the Common Tongue.

I will say that even by those parameters I don’t think most of the commoners would have been literate. However, Gendry was not in the same situation as most of the commoners.

Which leads me to...

Part 2: Socio-economic class in Medieval Times

The level of literacy among the commonfolk has to be examined on a case by case basis.

Literacy among “peasants” varied a lot depending on circumstance. So, for example, it’s not strange that Davos, who was a smuggler prior to meeting Stannis, was illiterate. Or Gilly, who was completely isolated from the world and in terrible conditions.

But Gendry is in a different situation.

As @arsenicandfinelace pointed out in this cool meta:

Gendry was definitely born low-class, as an unrecognised bastard whose mother was a tavern girl (read: one step away from prostitute). But the whole point of apprenticing with Tobho Mott is that that was a major leap forward for him, socially.

As Davos put it in 3x10, “The Street of Steel? You lived in the fancy part of town.” Yes, a tradesman of any kind is leagues below the nobility, and could never ever be worthy of marrying a highborn girl like Arya. But Tobho Mott is a master craftsman, the best armourer in the capital city of a heavily martial country. As far as tradesman go, he’s the best of the best, and charges accordingly.

There’s a reason Varys had to pay out the ass to get Gendry apprenticed there. If he had stayed, completed his apprenticeship, and eventually taken over the workshop, he would have been very wealthy (by commoner standards) and respectable (again, by commomner standards), despite his low birth.

Tobho Mott is a tradesman and a craftsman. He is part of the merchant class. * Merchants are often referred to as a different class from the rest of the population. The merchant class in Medieval Times was closer to the middle class of contemporary times.

“By the 15th century, merchants were the elite class of many towns and their guilds controlled the town government. Guilds were all-powerful and if a merchant was kicked out of one, he would likely not be able to earn a living again.”

Mott would be considered to be part of the merchant class - and not even a common kind of merchant either. He was the best Blacksmith in all of King's Landing, the capital of the Seven Kingdoms. So we can assume that Tobho Mott was a very wealthy and powerful craftsman and merchant.

“That many 'middle class' people (tradesmen, merchants and the like) could read and write in the late middle ages cannot be disputed.”

I’m not saying that all tradesmen/merchants/craftsmen were literate back then. It was still a smaller percentage than the nobility. Only the richer and more influential of tradesmen would learn Latin. But I think most of them would be literate enough in the vernacular to run a business. Considering Mott’s reputation and his clientele I’m certain that Mott is part of that literate percentage.

In season 2, Arya accidentally reveals to Tywin that she can read. Realizing her mistake she covers up by saying that her father, a ’stonemason', taught her. Of course, I don’t think that completely fooled Tywin but why did Arya say her father was Stonemason. Why did his profession matter at all? Surely it wouldn’t have mattered if he was a fisherman or a farmer... a peasant is a peasant, right?

Wrong.

“The Medieval Stonemason asserts that they were not monks but highly skilled craftsmen who combined the roles of architect, builder, craftsman, designer, and engineer. Many, if not all masons of the Middle Ages learnt their craft through an informal apprentice system”

“Children from merchants and craftsmen were able to study longer and continuous, so they were able to learn Latin at a later age. This way, everyone learned to read and write (some better than others) sufficiently for their trade.”

Stonemasons were the architects of the time and no doubt the top tier was literate.

Many trades (by the 15th C) required reading and writing, so it was taught to apprentices by the masters. We know from apprenticeship agreements that many masters were expected to continue the apprentice's literacy or start it, which makes sense for the wider viability of the trade.

The War of the Roses took place in the late 15th Century. So I’m guessing that that’s the time period that ASOIAF is mostly based on.

Part 3: Level of literacy

I think it’s safe to say that Gendry has some level of literacy. However, his “level” is pretty much up for debate. If he’d finished his apprenticeship it’s likely he’d have a decent level of reading/writing comprehension. However, near the end of his apprenticeship he was kicked out.

I’m not sure how much Gendry could read/write by the time that he was kicked out by Tobho Mott. But he’d already been his apprentice for 10 years (in show canon). More than enough time to get some basic reading/writing/basic math lessons.

It seems that show!Gendry is more likely to have a higher level of literacy than book!Gendry. In the show, he leaves Tobho Mott at 16, while in the book he is 14. This is just my own impression, but I think his education would be more complete by age 16 than age 14.

Not to mention that book!Gendry is still in the Riverlands and working for outlaws. But in the show we can assume that Gendry has been smithing in King’s Landing for years and it is insinuated that he owns a shop. Meaning he might have reached “Master” status and can take on apprentices of his own. It might seem like Gendry is too young for that. But it’s actually not that strange.

“Apprentices stayed with their masters for seven to nine years before they were able to claim journeyman status. Journeyman blacksmiths possessed the basic skills necessary to work alongside their master, seek work with other shops, or even open their own businesses.”

Considering that Gendry has been with Mott for 10 years in show!canon, it’s possible that Gendry was a “journeyman” and not an “apprentice” by the time that Ned meets him in season 1. But he might be nearing the end of his apprenticeship in the books.

Guilds also required journeymen to submit work for examination each year in each area of expertise. So, a journeyman who perhaps crafted swords, locks, and keys would need to submit each item to his guild annually for inspection. If the guild approved the craftsmanship of the products, the journeyman could eventually move up to master status.

The process of becoming a master could take from 2 to 5 years. Considering that Gendry is regarded as talented, it’s likely that he achieved this in a shorter period of time. As a journeyman he also needed to work alongside a master for 3 to 4 years before he could obtain master status. Which would still explain why he was so upset at being kicked out by Mott - it’s like someone getting kicked out while they’re trying to obtain a PHD.

By the time we meet him in season 7 it’s very possible that Gendry is now considered a master of his trade.

He also seems to be making armour and weapons for “Lannisters” which means he has a mostly noble clientele. He probably has plenty of fancy clients asking for custom-made products. With sketches and measurements and all that shit. Which is not surprising since he probably has a de facto reputation simply by merit of being Tobho Mott’s apprentice (lets ignore how dumb it is that no one discovered that Gendry was in King’s Landing since he made no effort to hide who he was or try to hide from the nobility lol).

Conclusion:

It’s safe to say that Gendry had some access to higher education. He can probably read and write enough for his line of work. It’s likely that his level would still leave much to be desired once he became a noble though. For comparison, imagine if someone left school at age 11 and was then required to write a college-level thesis. So he’d definitely need some “lordly” writing lessons and further education.

Gendry is still wildly uneducated for what he needs to do. So...

This meme is still gold 10/10

* Correction: Though Mott would be considered part of the same socio-economic class as merchants he is primarily a tradesman/craftsman, and would be referred to as such. Since merchants didn’t produce the goods they sold. However they could belong to the same guild, along with artisans and craftsmen.

151 notes

·

View notes

Text

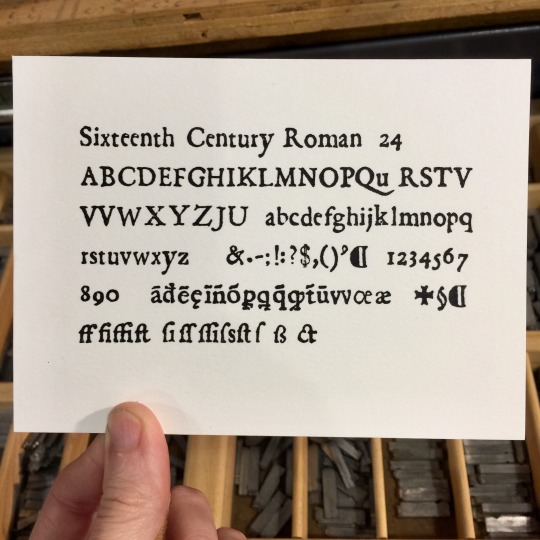

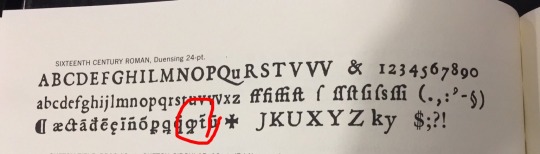

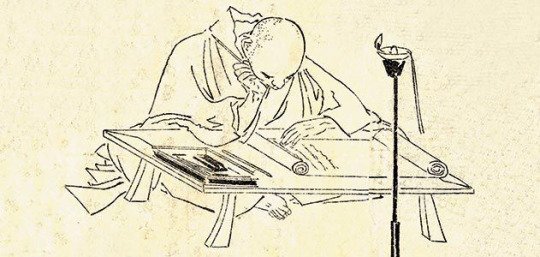

[image description: a proof of a font of handset type for letterpress printing, displaying every letter, symbol, and special character in the font. it's called "Sixteenth Century Roman," 24 pt., and is a rough-edged serif font with a deliberately worn look. end description.]

hello hello i am return from a deep dive into several reference materials that assumed a little bit more knowledge about how Medieval Latin works than i actually have, but, it was all exTREMEly inch resting to me. i am absolutely not a historian but here we are, a speedrun of my pinballing around trying to ensure that I know what the fuck im storing in my type corridor:

so 16th Cent. Roman, i already knew, was a font Paul Duensing designed based on this incomplete set of old Italian punches he acquired (punches, the first step of old school typecasting, where you carve the relief letter shape into the end of a stick of steel, and you uuuh punch that into the copper matrix, which is then the negative mould-shape you use to cast multiple copies of the lead sorts with hot metal; surviving punches are precious artifacts not the least because they are. they’re hand-carved!! often by the type designer themselves. historical and also wildly cool craftsmanship). these punches were all beat up and probably water damaged, fucky and rough-edged, so he re-did and filled in the gaps in the alphabet with similarly styled letters of his own. very cool. an extremely nerdy lil passion project of a typecaster in the 1960s, very typical of type people. we all find a Thing to obsess over, and sometimes it's reviving an incomplete set of punches from the 1500s that you found in, idk, it's usually a bucket in somebody's basement.

anyway it's got a bunch of ligatures and the long s, sure sure sure, but WHAT are all these gibberish characters with tildas and lines thru the stems of ps and qs and such—

Duensing's full font is in Mac McGrew's specimen book, great, i have that, except McGrew's book has complete proofs and a little bit of history for each font but doesn't always cover what each symbol in a unique alphabet is for, and i knew just enough about Latin to guess that they were abbreviations but not what each of them stood for. a little bit of searching got me this far, which is to say, "Abbreviation in Medieval Latin Paleography," a translation of an Italian essay on the subject from 1929. It is prefaced by the translators with gems like: "Take a foreign language, write it in an unfamiliar script, abbreviating every third word, and you have the compound puzzle that is the medieval Latin manuscript." Scribes writing in medieval Latin just tossed out letters they didn't care to deal with, constantly, and had stand-in special characters and abbreviations for syllables/words/particles and there were intuitive rules but way too many variations in time and place and person to make a reasonably-sized, static lexicon. amazing. hope all u paleographers are having fun over there.

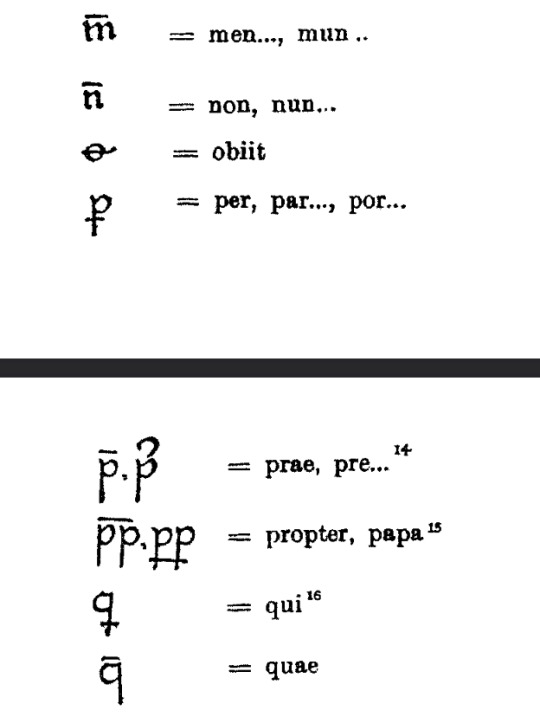

the essay has a great big glossary of truncations and abbreviations and so on which clearly cover most of the figures in Duensing's font:

[image description: screenshots of the essay, with various symbols and the Latin syllables they abbreviated. an m with a bar over it, ex., stood in for men or mun. end description.]

ok! BUT this q with a little swoop off the end kept bugging me!! for all these dead-use symbols this essay is using handwritten samples, obviously, and there's clearly variation in execution and also typographers take liberties, and i just thought, sure my piece of type looks a lot like the quod here but it does link the staff to the swoop where the handwritten sample doesn't, and it could just as well be a fanciful ligature for qn which apparently can stand in for quando, and i have no idea which is a more common-use syllable likely to be cast in the font if you're only going to pick your top 14, and i just like to be sure about things.

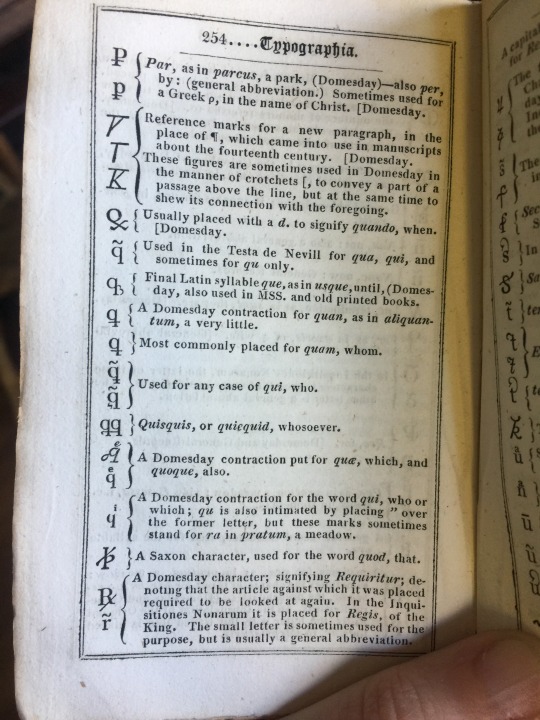

SO. i went to double-check with Johnson’s Typographia. Johnson made like a thousand pages of printing manuals set in tiny tiny type in the 1820s which are rad as hell and tell you all sorts of things about how to run a shop and build your own press and cast type and going rates for work and employment and also, the alphabets/type case layout for whatever language or symbol set you might have to set type in, when handsetting type was mostly the only way to get stuff printed—English, Arabic, Chinese, Hebrew, musical notation, astronomical signs, aaaand it’s got a section for "Marks & characters used in the Domesday Book & other ancient records.”

[image description: a photo of a page of the manual, with similar but not always identical symbols for abbreviated use. many of these abbreviations are described as "a Domesday contraction." end description.]

and WHAT is a Domesday contraction, WELL, it's a contraction specifically from/prevalent in the Domesday book, a deeply boring and historically important tome about property distribution in England. It’s literally a survey. who owned what, in 1086. presumably mind-numbing. enormous, handwritten in Medieval Latin, EXTREMELY cool, go look at some images of it at least, very important to historians, economists, linguists, and a complete pain in the ass to set in type when that technology became available, having to cast any significant proportion of these variant characters in an alphabet. Johnson says, (in 1824) “It is an improvement of latter years only*, to have type cast to resemble the abbreviations used in the more ancient manuscripts; they being formerly rudely imitated, either from a common fount, or else were cut in wood for the purposes of any particular work.” wow that sucks. but in 1773 the government really wanted to be able to reproduce the Domesday Book in type, so a couple people tried to cut a set of punches for Domesday abbreviations and Joseph Jackson got it done and it only took 10 years to print an edited version of the manuscript. and then apparently all the type was destroyed in a fire in 1808. WOW that sucks.

but the point is, Johnson has a great big glossary of characters as they were translated into type in the making of the printed Domesday Book, and the Domesday punches were used or refrenced in the printing of other medieval latin works, which consequences a degree of standardization in the abbreviations used in those versions of the text that handwritten manuscripts never had or needed.

notably the Domesday quod looks even more different from my piece of type here which was pretty annoying, so what are the chances this thing is a quando, and anyway that's when my sister texted me back with better computer skills and a different search engine and found me a perfect match on the first try. it’s a quod. this National Diet Library digital exhibition has several different sample fonts, both black letter and roman, with quite consistent letter forms, if not choices about which abbreviations to bother casting.

*I don’t……exactly know what he means by this, since Gutenberg and contemporaries absolutely did cast many Medieval Latin abbreviations for their fonts nearly 400 years before this. His dismissal of “from a common fount” might be fair, since i think what he means by it is that you’d have a generic set of abbreviation characters which you would have to use in conjunction with whatever font was the main body of your text, and it’s messy to mix things that weren’t designed specifically to match. he may just mean that it’s new for his contemporary foundries to be casting all these expanded alphabets of abbreviations; Gutenberg didn’t have foundries to buy from and made his own type. he could include as many characters as he had the patience for. maybe Johnson is just a guy from the 1800s that didn’t have the internet and i shouldn’t jump down his throat for not knowing something. idk!! i have homework.

anyway that was my Friday!! feel free to correct me and/or suggest further reading if early typecasting is your Thing or. again. you just have better googling than me.

#letterpress#letterpress printing#handset type#lead type#typography#long post#:(( sorry#omitted: Johnson's scathing opinions on Almanacks and the people who read them#and ask you to typeset them#'''''the credulity of the vulgar''''''' alRIGHT bud#i guess if he was willing to set that whole paragraph in 8 pt.#or pay for it#it was at least an opinion he believed in very strongly.

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

“…In modern English, we often use oath and vow interchangeably, but they are not (usually) the same thing. Divine beings figure in both kinds of promises, but in different ways. In a vow, the god or gods in question are the recipients of the promise: you vow something to God (or a god). By contrast, an oath is made typically to a person and the role of the divine being in the whole affair is a bit more complex.

…In a vow, the participant promises something – either in the present or the future – to a god, typically in exchange for something. This is why we talk of an oath of fealty or homage (promises made to a human), but a monk’s vows. When a monk promises obedience, chastity and poverty, he is offering these things to God in exchange for grace, rather than to any mortal person. Those vows are not to the community (though it may be present), but to God (e.g. Benedict in his Rule notes that the vow “is done in the presence of God and his saints to impress on the novice that if he ever acts otherwise, he will surely be condemned by the one he mocks.” (RB 58.18)). Note that a physical thing given in a vow is called a votive (from that Latin root).

(More digressions: Why do we say ‘marriage vows‘ in English? Isn’t this a promise to another human being? I suspect this usage – functionally a ‘frozen’ phrase – derives from the assumption that the vows are, in fact, not a promise to your better half, but to God to maintain. After all, the Latin Church held – and the Catholic Church still holds – that a marriage cannot be dissolved by the consent of both parties (unlike oaths, from which a person may be released with the consent of the recipient). The act of divine ratification makes God a party to the marriage, and thus the promise is to him. Thus a vow, and not an oath.)

…Which brings us to the question how does an oath work? In most of modern life, we have drained much of the meaning out of the few oaths that we still take, in part because we tend to be very secular and so don’t regularly consider the religious aspects of the oaths – even for people who are themselves religious. Consider it this way: when someone lies in court on a TV show, we think, “ooh, he’s going to get in trouble with the law for perjury.” We do not generally think, “Ah yes, this man’s soul will burn in hell for all eternity, for he has (literally!) damned himself.” But that is the theological implication of a broken oath!

So when thinking about oaths, we want to think about them the way people in the past did: as things that work – that is they do something. In particular, we should understand these oaths as effective – by which I mean that the oath itself actually does something more than just the words alone. They trigger some actual, functional supernatural mechanisms. In essence, we want to treat these oaths as real in order to understand them.

So what is an oath? To borrow Richard Janko’s (The Iliad: A Commentary (1992), in turn quoted by Sommerstein) formulation, “to take an oath is in effect to invoke powers greater than oneself to uphold the truth of a declaration, by putting a curse upon oneself if it is false.” Following Sommerstein, an oath has three key components:

First: A declaration, which may be either something about the present or past or a promise for the future.