#alsacian

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Alsacian children, France, by Jean-Pierre Badias

#alsacian#french#france#europe#western europe#folk clothing#traditional clothing#traditional fashion#cultural clothing

204 notes

·

View notes

Text

And an Alsacian Miku for @trashlord-watson !

Alsace is a region at the est of France, bordering Germany, and that's where Sauerkraut (choucroute) comes from ! Also the traditional costume includes a big bow in the hair which I... adapted ❤️

#hatsune miku#miku fanart#french miku#alsace#elsass#people who tend to say 'white people have no culture'.... the fuck does Breton and Alsacien and Aveyronnais have in common.#their languages and traditions slowly diseappearing i guess ???#anyway learn your local patoi and talk with the elders in your community <3

845 notes

·

View notes

Text

Can't do alsacian birds without WHITE STORKS : behold the lovers

Made for the Dinoël, a creator's market in Strasbourg, where you'll find prints of all my dinoël illustrations ! (and more)

Dinoël est un marché de créateur.ices, organisé le 7 décembre à Strasbourg... Plus d'informations ICI

59 notes

·

View notes

Text

And a silly lineup of all the things we drank. It happened to be the day we hosted an Alsacian masterclass & Champagne tasting at the restaurant, so my colleague turned up with several other sample bottles. I was a mess the next day x

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Autumn, Bacchus and Ariadne (Eugène Delacroix, 1856 - 1863)

This painting belongs to a set of four allegories of the four seasons, personified in the characters of classical mythology deities (The Hartmann's Four Seasons). They were executed by Delacroix between 1856 and 1863, and ordered by the Alsacian industrialist Frederick Hartmann.

Delacroix’s choice for autumn draws on the common association between autumn/fall and wine, in Bacchus and Ariadne. After being abandoned on the island of Naxos by Theseus, who had promised to marry her, Ariadne is discovered by the young Bacchus. Here, Bacchus has just arrived and is helping the gloomy and despondent Ariadne to her feet. They shortly fall in love and marry.

Media: oil, canvas

Dimensions: 196 x 165 cm

Exhibit in the Museu de Arte de São Paulo - São Paulo, Brazil.

#delacroix#eugene delacroix#oil painting#painting#romanticism#greek gods#greek mythology#art#artwork#oil on canvas

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

food log 6/20/24

b: sourdough toast with ricotta and strawberries (208)

d: trader joe’s alsacian pizza thing (560)

other: 2 high noons but im prob gonna have another (200-300)

total: 968-1068

exercise: 1.5 min walking and 50 min pilates

i felt so skinny for like 4 days and now i feel huge again. im relying on eating 1000-1300 w my moderate exercise to keep shedding weight moderately but i feel gross. im literally unable to restrict further though to function at work + not have my bf notice. ig i could stop drinking but thats unlikely. it might be my period but also my new scale annoys me and i wish i hadnt thrown away my old one bc idk whats up or down anymore

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

French (alsacian) costumes for the fontaine and mondstadt girlies <3

#genshin#genshin impact#genshin impact fontaine#genshin fanart#fanart#genshin impact fanart#mona#fischl#furina#lynette#alsace#traditional costume#man idk i just wanted to draw genshin characters and costumes from where i'm from

66 notes

·

View notes

Text

Some scholarly notes about the Grimm fairytales (2)

A follow-up of this post.

The Frog King or Iron Henry (Der Froschkönig oder der eiserne Heinrich)

This story belongs to the AaTh 440, "The frog-king".

The story first appears in the 1810's manuscript, written by Wilhelm - it was probably told by Henriette Dorothea "Dortchen", Wilhelm's future wife. A second version, called "The frog prince", had been told to them by their friend Marie Hassenpflug and was published in the 1815 edition as the thirteenth tale, before being moved to the notes of the 1822 due to its too-great similarity with the KHM 1.

This fairytale was originally called "The king's daughter and the bewitched prince". The 1810 manuscript has, written by Jacob right next to the title, "The frog-king", while the paper on which he had placed all his notes about the fairytale bore the name "Iron Henry". The evolution of this fairytale is very interesting because it testifies the brothers' love and care for details, hich had the story double in sie throughout the editions. In the final text we have, for example, a long sentence describing how the princess sees the ball fall into a well so deep she can't see the end, and about her crying a lot and lamenting, etc, etc... In the 1810 manuscript it was just one short sentence "She stood near the well and she was sad."

The major editing of this tale was the removal of the erotic motif from the tale's ending. Originally, the frog asked the princess the authorizaton to sleep in her bed, and right after the frog became a human it was written "the princess joined the prince in bed". This, plus the addition by the Grimms of moral lessons delivered by the father (the king tells things such as "You must always keep your promise" and "You must not disdain the one who helps you"), completely changed the goal and purpose of the tale - it was originally about setting free an animal husband, but the Grimms turned it into a moral tale to learn a virtuous behavior.

The brothers Grimm considered this fairytale to be the oldest and most beautiful of their collection. Allusions to the frog-king tale can be found as early as the Middle-Ages and the 16th century. In the 1801 edtion of the 1548 Scottish book "Complaynt of Scotland", a note evokes how a tale is similar to "The Frog Prince" due to having a well, the presence of magic, and a frog complaining in rhymes. In this Scottish version, a girl is sent by her stepmother to fetch water at "the well of the world's end". There she meets the frog, who tells her it will offer her water only if she agrees to marry it - if not, the frog will rip the girl apart. The brothers Grimm themselves noted various literary sources for their tale, that they used in their compilation work. The name of Henry (Heinrich) comes from the novel "Der arme Heinrich" by Hartmann von Aue. They also listed the "Froschmeuseler", a didactic epic by Georg Rollenhagen depicting a war between frogs and mice: the association of sadness with "rings of iron" comes from this text, as well as the very name "frog-kng" which is found in the title of the second chapter "Tale of the encounter between Thief-of-Crumbs, son of the mice-king, with the frog-king".

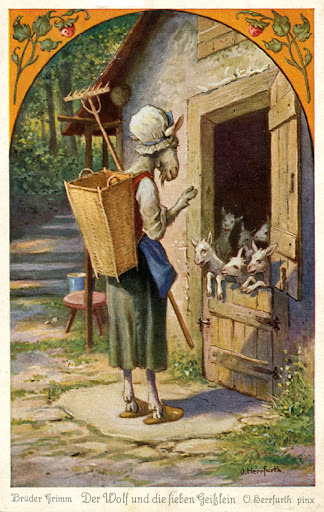

The Wolf and the Seven young Goats (Der Wolf und die sieben jungen Geiblein)

It is the AaTh 123, "The wolf and the lambs".

Collected in the "region of Main" according to the Grimm, it is very likely that the brothers Grimm received this tale from someone of the Hassenpflug family, as they knew the French fables of La Fontaine which correspond to this fairytale. In the 5th edition of their book, the brothers Grimm modified their story due to the publication in 1842 of an Alsacian tale by Ströber, "Die sieben Gaislein", "The seven young goats" (collected in Volksbüchlein, "The Folks' Small Book) - Wilhelm Grimm borrowed several expressions from this text. The brothers Grimm listed this Alsacian tale in their notes.

In their notes the brothers Grimm listed a Pomeranian version about a child who, when his mother is out, is swallowed by a sort of bogeyman known as "The children's ghost". But since the ghost eats stone at the same time, he becomes slow and heavy - he falls and the child can escape his belly unharmed. The brothers Grimm also listed variations collected/written by Boner in his Edelstein, and by Buckhard Waldis - as well as the La Fontaine fables. They also knew of a French fairytale, from which they noted a passage where the wolf asks a miller to turn her paw white with flour, and since the miller refuses, the wolf threatens to eat him. The Grimms linked the episode of the wolf's belly filled with stones with the legend of a Nereid called Psamathe, who sent a wolf destroy the flocks of Peleas and Telamon, only for the wolf to be petrified.

This tale, like many others within the Grimm's collection (it is especially comparable "Cat and Mouse in Partnership) is aimed at educating young children, with the narrator highlighting how children should be wary and distrustful of the wickedness and cowardice of men. Unlike other versions and predecessors of the tale, the brothers Grimm insist on the mother's role as a teacher, and on the fact that she saves her kids.

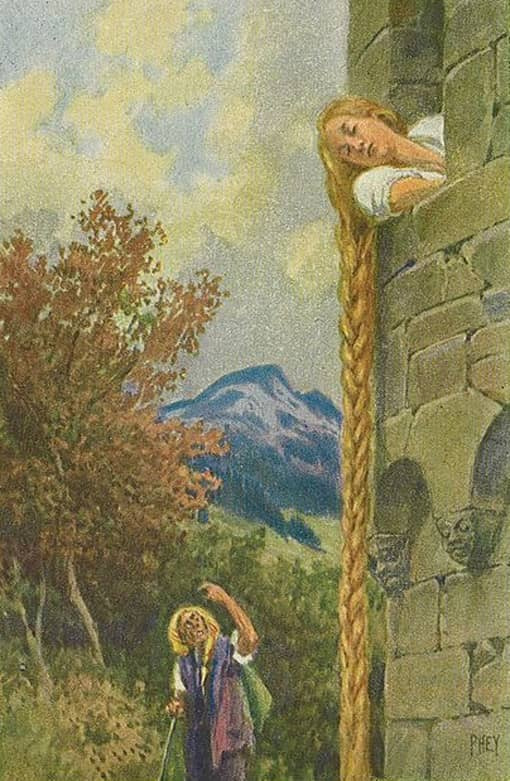

Rapunzel

It is the AaTh 310, "The maiden in the tower".

The literary sources of this fairytale are well-known. It was preceeded by the French literary tale "Persinette", by mademoiselle de La Force, itself inspired by Basile's story "Parsley Flower". In their notes the brothers Grimm explained they took inspiration from the almost-literal German translation of mademoiselle de La Force's story by Friedrich Schulz. However, in quite a misunderstanding, the brothers admired this tale as being an obvious "folktale" coming from the "oral tradition" - when we know it was a literary fairytale, though based on a folkloric motif.

The text was heavily edited after the many criticism the first edition of the book underwent - the scene depicting the prince's relationship with Rapunzel was regularly changed. In 1837 it is written that the prince asked Rapunzel to marry him almost right away, and she agreed since he was young and pretty, and they "held hands". In 1819, it was written that they lived together in "joy and pleasure" for a certain time, and "loved each other like woman and wife", and the "fairy" only realizes something is up when Rapunzel blurts out it is easier to make the prince climb than her "godmother". In the 1812 edition, it is said that Rapunzel and prince lived together in "joy and pleasure", but no mention of any marital couple whatsoever - and Rapunzel betrays her condition to the "sorceress" because she complains about her clothes getting too tight.

The Grimm noted that many versions of the "girl in the tower" fairytale existed, but with a different opening relying on the "forbidden room" motif: the witch punished the girl by locking her up in a tower because she had opened a door the witch explicitely forbade her to. The Grimm also listed several stories (outside of Basile's version) where a mother (sometimes a father) bargains their future child to satisfy a temporary craving - such as the Nordic "Alfkongs-Saga", where Odin offers Signy's wish for the better bear in the world in exchange of what is "between her and the barrel", aka the child she bears. In a book of Büsching we find a girl named "Petersilie" (Parsley in German) which loves eating prasley more than anything in the world and brushes her long hair by a window. The idea of using hair as a rope or ladder, long before Basile used it, seems first recorded by from the "Book of the Kings" of the poet of Persia Firdoussi, in the 10th century: the hero, Zal, joins the beautiful Roudebeh by climbing up her braids.

The name the sorceress wears in the German tale, "Frau Gothel", had been explained by the Grimm in such a way: "The godfather is not only called Vater (father) but also Pathe (godfather/"parrain" in French), or Goth or Dod ; the baptized child is also called "Pathe" or "Gothel", hence the confusion of the two within the legend". So, the dominating hypothesis (which seems confirmed by the variations of the fairytale) is that "Gothel" means "godmother".

Hansel and Gretel (Hänsel und Gretel)

It is of course the AaTh 327 A, "Hänsel and Gretel" (a subtype of "The children and the ogre"). It also covers the AaTh 1121, "Burning the witch in her own oven".

In the 1810 manuscript this fairytale was called "Little brother and Little sister", a name that would later be reused by another famous Grimm fairytale (KHM 11). It seems that one of the reasons for the Grimm's big edits on this tale was the publication in 1842 of the Alsacian version of this story by August Stöber, "The little house of pancakes" (Das Eierkuchenhäuslein) - which itself was inspired by the Grimm's original publication of "Hansel and Gretel" (full loop here). Wilhelm Grimm notably borrowed several turn of phrases from Stöber.

The motif of the children abandoned in the woods can be found back in Basile's Nennillo and Nennella, though the extension to the encounter of a child-eating monster is rather present within Perrault's Petit Poucet and madame d'Aulnoy's Finette Cendron (both also contain the motif of the treasures inside the ogre's house). While we know the Grimms were aware of Perrault's story, we also know that madame d'Aulnoy's fairytales, including "Cunning Cinders" had been brought to Germany by ther adaptation for the German branch of the "Bibliothèque Bleue" - Blaue Bibliothek. Ludwig Bechstein's own version of "Hansel and Gretel" was very famous - and he actually wrote it inspired by the German translation of Stöber's own tale.

The motif of ashes, crumbs or seeds left behind to tell the way is recurring within the brothers Grimm fairytales: it also appears on the KHM 40 (The Robber Bridegroom) and 169 (The Hut in the Forest), as well as in their first "Legend for children". This motif can be found back in German literature to 1559's Gartengesellschaft (The company within the garden) by Martin Montanus, where it appears in the tale "The small earth-cow", Das Erdkühlein.

It is recognized that this fairytale is the second most popular and famous Grimm fairytale right after Snow-White. It was heavily illustrated - first by none other than Ludwig Emil Grimm himself (another brother of the Grimms). As we said before, Bechstein's own fairytale was a strong "rival" to the Grimm's, and was illustrated by Ludwig Richter in 1853. The motif of the "bird leading to the Ohterworld" is found back in the KHM 123 (The Old Woman in the Wood), and in both cases the fact the bird is white indicates that it is an Otherworldy animal.

The Brave Little Tailor (Das tapfere Schneiderlein)

This fairytale belongs to many different Aa-Th types: 1640 (The brave little tailor), 1051-1052 "Curb, cut and move a tree", 1060-1062 (Throwing-stone conquest), 1115 (Attempt to kill the hero in his bed).

The 1810 manuscript began with this tale as its opening, probably as an homage to Brentano, since Wilhelm Grimm found this tale within his library, in a book called "Wegkürtzer", by Martin Montanus.

Among the modifications of the 2nd edition, a very interesting one is the addition of a sentence closing the first paragraph "and his heart moved with joy like the tail of a small lamb". This sentence comes from a novel by Christian Weise calle "The three most mad madmen in the whole world/The three most foolish fools in the whole wide world" (1762). Wilhelm Grimm explained this, as well as several other similar "borrowings", in the preface of the sixth edition, as his desire to insert in his tales specific sentences and expressions he knew to be typically German.

The brothers Grimm notd that Montanus' Wegkürtzer was frequently alluded to within the Renaissance literature and the baroque one - for example, when Johann Fischart translated in German Rabelais' Gargantua he inserted the sentence "I will kill all these flies, nine at once, like this tailor once did." It was also evoked in the "Simplicissimus" of Grimmelshausen, but references to the Little Tailor story go back to the Middle-Ages. The episode of a giant crushing a stone until water comes out of it is found in "Brother Werner", from the Codex Manesse (which compiled German Minnesang, courtly poetry) ; and Heinrich von Freiberg's Tristan describes at one point the hero crushing a cheese until juice comes out of it. Montanus' text was also used by Ludwig Bechstein in his book of German fairytales. One can compare the story of the Grimms to Tabart's "Jack the giant-killer" and Afanassiev's "Foma Berennikov".

The measurements in this story make no sense at all. The tailor buys four half-ounces of marmelade. Given an ounce was roughly 32 gr, the tailor bought 60 gr roughly... Not a quarter of a pound, as he claims. The reason for this incoherence is because, before 1854, a "pound" varied depending on which area of Germany you were into (it was 467 gr in Berlin, 510 in Nuremberg). It was only in 1854 that the value of the pound was unified in Germany, at 500 gr. Finally we note the presence at the end of the tale of the common European belief n the "Wild Hunt".

Cinderella (Aschenputtel)

Of course, it is the Aa-Th 510A, "Cinderella".

As early as the first edition, this fairytale was a mix of several variations. In their notes, the brothers listed nine different versions of the tale. One of them is quite fascinating: the opening scene of the mother's death and her promises of help is missing, the story begins immediately on the heroine's misfortunes. The end of the version also greatly differs and enters the domain of the KHM 11 "Little-brother, Little-sister". Soon after his wedding with Cinderella, the prince forbids her to enter a specific room of the castle - but encouraged by her sister, she opens the room when the prince is absent. It contains a fountain of blood that Cinderella's sister uses for an evil use: after the queen gives birth to her first child, her sister throws her in the fountain and replaces her in the bed. But the guards of the castle hear the moans of Cinderella, rescue her and the wicked sister is punished. Another version, from Mecklembourg, has an ending which makes the tale close to the legend of saint Genevieve of Brabant: Cinderella's stepmother and stepsister steal away Cinderella's two first children and replace them with animals ; the third time she gives birth, they order the gardener to kill the queen and her child, but he rather hides them in a grotto in the woods, where the child is fed by a doe. One day the child, old enough, goes to the castle to speak to his father, revealing to him the fate of his mother.

Another version, this time from Paderborn, begins in a way very similar to "Snow-White": a queen wishes to have a child as red as a rose and as white as snow. She gets her wish, but then her servant pushes her outside of the window, to replace her as the king's wife. The usurper gives birth to two daughters, and from then on we return to the classical Cinderella tale - her dead mother helping her from beyond the grave by offering her a key, opening a hollow tree where Cnderella finds what she needs to wash herself and dress up pretty for the church (plus a prayer book). Büsching evoked the existence of another version in the Zittau area, where Cinderella is a miller's daughter that is forbidden to go to church, and where it is a dog that denounces the false fiancée. Outside of all these oral sources, the brothers Grimm took inspiration, of course, from Charles Perrault's Cinderella, as well as from the first German literary record of the Cinderella story, "Laskopal and Miliwka", published in an anonymous collection of legends in 1808 (Sagen der böhmischen Voreit aus einigen Gegenden alter Schlösser und Dörfer").

From the second edition onward, the brothers Grimm heavily edited the story. They removed all the words and passages that referenced too much Perrault's version, replacing them by elements taken specifically from the three versions they collected in Hesse (such as the demand for a branch of a nut-tree, and the motif of the tree growing on the grave). In the 1812 edition, it was Cinderella's own mother who advised her daughter to plant a tree on her grave, and who predicted that this tree will help her in the future. Throughout the rewrites, Wilhelm Grimm heavily insisted upon the heroine's virtues, accentuating them so that they would fit the feminine bourgeois ideal of the time.

The first European record of this tale is Basile's "The cat of the ashes", and other famous literary versions include Perrault's Cinderella, madame d'Aulnoy's Cunning Cinders, as well as Ludwig Bechstein's Aschenbrödel. These versions were massively spread throughout Europe, notably due to the "peddling literature", the cheap books sold by peddlers: they helped the "Cinderella" fairytale type becoming as popular as it is today, and it seems very likely they influenced all the versions of the tale that came after them.

In their notes, the brothers Grimm explicitely compared the motif of the shoe in Cinderella with the legend of Rhodopis, who had her shoe stolen by an eagle, and the pharaoh that found it had her owner searched throughout Egypt. However the motif of the animals helping a persecuted heroine (especially when it comes to splitting grains) is very common, and has been popularized by the Roman tale of "Cupid and Psyche".

This fairytale is closely tie to the KHM 130, "One-Eye, Two-Eyes and Three-Eyes", both sharing the idea of a young girl humiliated by her sisters, and who obtains a social ascension as a form of compensation. A. B. Rooth studied the evolution of the Cinderella fairytale-type, and its relation with other fairytale-types: they determined that it is very likely the "Cinderella" story was originally told as a sequel to the "One-Eye, Two-Eyes, Three-Eyes" story-type. Later, the second part of this story gained its own autonomy, and became the "Cinderella" we know today.

The sexual connotations within the motif of "trying on the shoe" has been repeatedly noted and analysed since the Grimms published their story. Jacob Grimm himself saw in this the remains of an archaic Germanic betrothing ritual. Heinz Rölleke highlighted another cultural ritual that involved the future husband of a bride removing her old shoes before marrying her. The idea of the slippers tied to a wedding is also found within the KHM 133 (The Shoes that were danced to Pieces).

The name of the heroine in Germa, "Aschenputtel" designates a type of kitchen girl who searches throughout the ashes, and thus "rolls" herself in them - but it also means figuratively an insignifiant and a dirty girl. It seems to derivate from the greek "achylia", cinders/ashes, and "puttos", female genital organs. A combination echoed by the French name "Culcendron", "Ashen-butt". By extension, the name "Aschenputtel" can also designate the younger brother when he is disdained by his brothers and considered to be an idiot by his family: there is a lot of male Cinderellas in folktales, especially in Northern and Central Europe, but also in all German-speaking countries.

Frau Holle

Belongs to the AaTh 480 "The kind and unkind girls".

This story was told to Wilhelm Grimm by his future wife, Henrietta Dorothea Wild, who was then 18 years old. A secondary source was a tale told to their by the Hanovre pastor, Georg August Friedrich Goldmann - this second version contained the episode of the rooster saluting the girls. The second edition of the brothers Grimm's book added several details to this story to "rationalize" it - notably the Grimm added of their own an explanation as to why the girl jumps into the well.

This fairytale comes from Hesse and Westphalia. The brothers Grimm listed in their notes four other versions of it - and the first is more noticeable, because it echoes "Hansel and Gretel", as the house where the girls arrive is made of pancakes (crêpes). Older literary versions of "Frau Holle" can be found in Basile's Pentamerone (The Months, The Three Fairies), as well as within a French fairytale written by Gabrielle-Suzanne de Villeneuve, "Les nymphes" (The Nymphs). Translated in German in 1765, Villeneuve's fairytale notably inspired the Grimms when they composed their 1810 manuscript - they adapted her tale as their own story called "The marmot". Before the brothers Grimm, "ancestors" of "Frau Holle" can be found in various German fairytales, present in the collections of W. Reynitzsch (1802) and Benedikte Naubert (1789). Ludwig Bechsten did his own version of the fairytale (Gold-Mary and Pitch-Mary, Die Goldamaria und die Pechmaria) which had a huge success in Germany.

This fairytale belongs to a wide series of tales in which young girls leave their house to enter a far-away country which might be the Otherworld, and where they become the servants of a spernatural being. There, by performing tasks in a disinterested manner, they are rewarded. As with other fairytales, "Frau Holle" shows how the Otherworld and our world are inter-dependant with each other. "Frau Holle" had a huge mediatic success: it was adapted several times as movies, it is heavily present in children's literature, and it was heavily illustrated. The character of Frau Holle ("Holle" derivading from the Middle-High-German "hulde", "benvolent") is an ambiguous character, and shares several characteristic with Germanic water-spirits. She is a giver of supernatural gifts and goods, but she also punishes the wicked. This supernatural character is very present in German legends, especially in the oral tradition which associates her with the works of weaving and spinning. She might have her roots in the figure of a spirit in charge of women's initiation rituals.

Little Red Riding Hood (Rotkäppchen)

It is of course the AaTh 333: "Little Red Riding Hood".

The two versions the brothers Grimm used to create this story were told to them by Johanna Isabella and Marie Hassenpflug. Isabella's version was most notable for being an obvious transposition of Charles Perrault's fairytales - with two elements changed. The tragic ending was modifed so that the girl and her grandmother would be saved ; and the erotic connotations of Perrault's fairytale (where the wolf was presented as a dangerous seducer) were removed.

Charles Perrault's fairytale was also present in German literature through Ludwig Tieck's verse tragedy "The life and death of little Red Riding Hood" (Leben und Tod des kleinen Rotkäppchens), published in 1800. As for Ludwig Bechstein, he inspired himself from the brothers Grimm tale to create his own "Little Red Riding Hood". M-L-Tenèze has worked on collecting all the oral and popular versions of Little Red Riding Hood in France, its birth-country, and has identified its original format as it must have been told before Perrault: usually they end like his tale in a tragic way for the girl, but rarely she notices she is in bed with a monster and manages to trick it to escape. However a detail Perrault erased and that is present in these versions is how the wolf keeps a bit of the grandmother's flesh and blood, that he offers to the little girl as food.

The first version of this story, in the original edition of the brothers Grimm book, was much more didactic than the one we have today, heavily insisting on how the little girl should have obeyed to her mother, and how there are specific ways to interact with strangers on the road - and in fact, it seems that the reason this fairytale was so popular and widespread was precisely because of its didactic nature. Because everybody knows the "original" version of the Grimm better than the final one, their second and revised text that shows a heroine able to learn from her mistakes, and ending up defeating the wolf of her own without any outside help. It should be noted that the first version of the Grimm tale had an echoing motif with the KHM 5 "The Wolf and the Seven Young Kids".

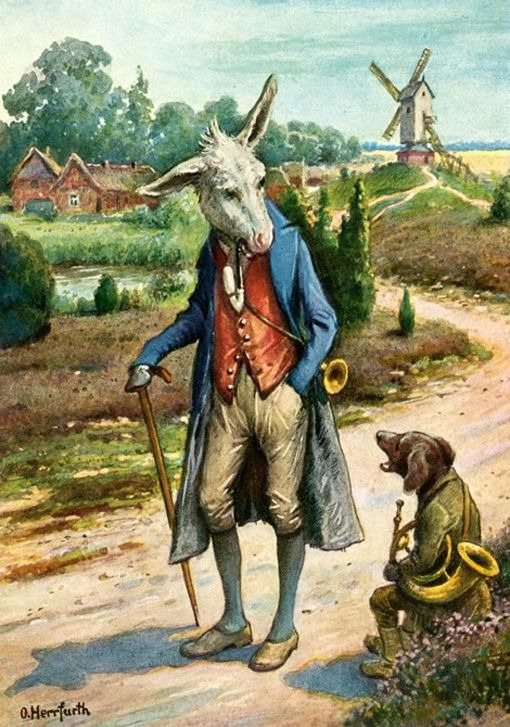

The Musicians of the Town of Bremen (De Bremer Stadtmusikanten)

They eblong to the AT type 130 "The animals find a house for the night", more specifically the AT 130 B, "The animals flee after a death threat".

This fairytale, like many of those present in the brothers Grimm collection, was actually the fusion of two distinct stories they collected. The brothers Grimm described in their notes a literary source for this story: a long extract from "Froschmeuseler", a didactic epic by Georg Rollenhagen published in 1595 and which had animals as protagonists. In this text however, it is a dog that leads the six other animals (an ox, a donkey, a cat, a rooster and a goose). For this poem (of 20 000 verses) Rollenhagen himself had another literary inspiration: a first-century epic describing a war between frogs and mice.

The nicknames of the various animals were only added in the third edition of the book. The notes of the brothers contain a third version of the tale they did not use, and which mostly differs when they arrive at the robbers' house. Instead of chasing them away, the animals enter peacefully in the robbers' den, play music and are fed as a reward. Then the robbers leave, and when they return they send one of theirs to check if everything is alright in the house - and he suffers the fate described in the Grimm's final tale. There are other versions of the story where there are only two animals involved (a dog and a rooster), who get involved with a fox that the dog ultimately kills. In fact, the oldest versions of this tale all deal with domestic animals confronting, not human criminals, but rather savage animals of the forest. Outside of Rollenhagen's text, another literary precedent was a poem of Hans Sachs from 1551, where the house is inhabited by wolves.

The title of this story seems to refer to traditional mockeries of the music of the town of Bremen, which was a very famous city at the time. Anti-Aarne wrote an entire monography about this tale-type, "The travelling animals" (Die Tiere auf der Wanderschaft) where he highlighted how this story was the Western "sibling" of a more Oriental fairytale-type, the AaTh 210 "The rooster, the chicken, the duck, the pin and the needle are travelling". This tale is mostly present in the Far-East (Middle-East?), and very rare in Western Europe - but it is still present within the brothers Grimm's collection as the KHM 10 (The Pack of Ragamuffins), 41 (Herr Korbes), and 80 (The Death of the Little Hen). The oldest Western form of this other fairytale type is within the Latin poem by Nivard of Gand, 1150's "Ysengrimus", where animals considered too old are banished by their masters or about to be killed, and flee into the forest. The "Roman de Renart" (the Roman of Reynard) also contains ths motif in its eighth branch - and the ingratitude of mankind towards the creatures that served them all their life is also a theme of the KHM 48 (Old Sultan).

#german fairytales#grimm fairytales#brothers grimm#the frog king#rapunzel#hansel and gretel#cinderella#history of fairytales#evolution of fairytales#the musicians of the town of bremen#little red riding hood#frau holle#the brave little tailor

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

I was trying to look around to see if I could find some more information about Père Noël in its pre-Americanized incarnation online, but unfortunately most websites share the misinformation that "Père Noël" only existed from the 50s onward and was a French invention... No. [Note: I know books exist folks, but I precisely wanted to do a web research first]

There is only one website that does not share this idea and does identify Père Noël as a typical French figure that was then overtaken by the American Santa Claus, and the most fascinating thing is that it points out (despite previous sources I shared claiming "Père Noël" was first recorded in literature in the mid-19th century, by people describing their youth around the turn of the 18th-19th century) that Père Noël seems to have existed since the Middle-Ages, with texts referring to "Père Noël" or to "Monseigneur Noël". But it does recognize that the Père Noël traditions really boomed in the 19th century and were associated with the bourgeoisie of the time...

The website in question however is mostly focused on the various local, regional incarnations of the gift-giver - because as with many things in France, this tradition is rather a set of various regional and localized specificities that were ultimately synthetized into one entity.

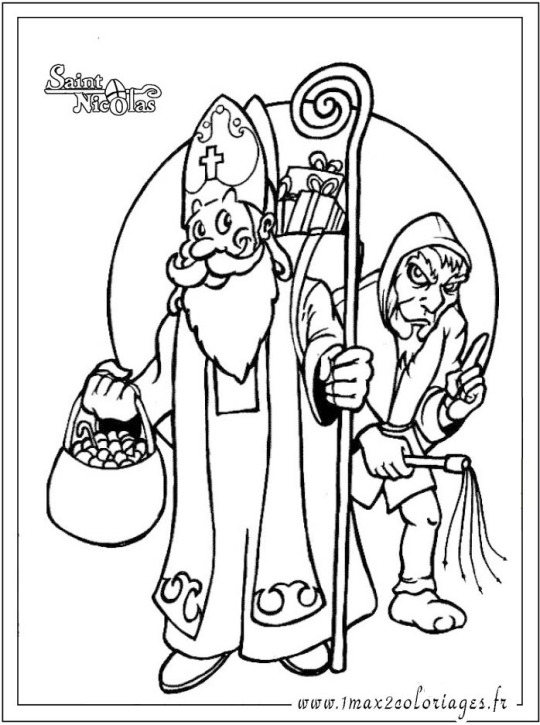

It reminds that in the Lorraine and Alsace region, the Germanic cultures and German influences make it so that Saint Nicholas and Christkindl are still the main gift-givers. In Lorraine it is Saint Nicolas who is most honored (he is after all the saint patron of Lorraine). Appearing in his bishop outfit that makes him look a lot like Santa Claus (thick white beard, large clothes of red and white), every 6th of December he brings gifts and treats to nice children - while naughty children are confronted by his dreaded companion, Père Fouettard dressed in blacks, who beats up with a stick bad children. Saint Nicolas is also still strongly celebrated in the North of France (aka, what is above the Parisian region, because despite what some foreigners believe, Paris is not part of the North).

While in Alsace it is the Christkindl that still goes strongly, with Hans Trapp as its own Père Fouettard. The website briefly reminds that Christkindl is an avatar/incarnation of the Child-Christ, or Baby Jesus, that ended up being fused with the 23rd of December Saint, Sainte Lucie (Saint Lucia), resulting in this unique Christmas figure appearing as a woman dressed in white with a crown made of fir branches topped by four candles. It also reminds how Christkindl stays a symbol of Protestant end-of-the-year celebrations, as they pushed the Christkindl figure to oppose and replaced the Catholic celebrations of Saint Nicolas. Finally, there is an Alsace-specific legend that claims Hans Trapp actually originated as an Alsacian lord that tyrannized his people - Hans von Trotha, the 15th century lord of Wissembourg.

[Given the Alsace region has a lot of website pages about its traditions I'll place here in brackets informations from other websites:

The Christkindl, also written Christkindel or Chriskindla, is a Christian figure that is supposed to be an embodiment of L'Enfant Jésus, Child Jésus (the name comes from Christ-Kindel ; Christus-Kindlein, Christus als Kind), but definitively was influenced by Saint Lucia, who is very big in Scandinavia. In fact, Saint Lucia and the Christkindl look a lot like each other - female entities dressed in white with a crown of candles... Though the Christkindl can appear both as an adult woman and as a little girl, and also tends to have white veils. People tend to also find in Christkindl remnants of the Germanic goddess Berchta. No need to tell you that the Christkindl is big in all parts of the world influenced by German culture - Germany, Austria, northern Italy, Croatia, Slovenia, Switzerland, Czech Republic, and even some parts of Brazil, the ones where there was strong German imigration.

The Christkindl appeared in the 16th century with the Protestant Reform. Up until this point the day of Saint Nicolas was a very big thing in Alsace - saint-patron of school students, he offered good children mandarines and "manala" (a brioche in shape of a child). But the Protestants did not agree with this (Protestants were known to strongly dislike saints in general), and so they replaced the saint with the Christic figure of Christkindl, while keeping Père Fouettard/Hans Trapp (whose job was to threaten with stern lectures naughty children... or take them in a bag to abandon them in the deep dark woods). The change occured over the 16th century, from 1530-1536 (last mentions of Saint Nicolas in Alsace) to 1570 (first mention of Christkindl, when the Klausemärik was replaced by Christkindelmärk). In fact, Christkindl still has some Saint Nicolas traits - she also goes around with a donkey, named Peckeresel, which carries two bags, one for the treats (mandarines and bredalas), one for the whips. People left hay or carrots for the donkey to eat by the front door. Pastor Johannes Flinner made a strong public attack against saint Nicolas in Strasbourg during the "cultural transition", by pointing out that distributing gifts to all should be the prerogative of the Christ and no one else.

During the 20th century the Christkindl lost popularity in Alsace (jee, I wonder why France would like to bury Germanic traditions in the century of World War II) - but it returned in the traditions from the 1990s onward.

Fascinatingly, despite being supposedly a Christ-figure of an angel, the Christkindl, or White Lady, is also frequently called in alsace, a "fée", a fairy, la fée de Noël, the Christmas fairy. It doesn't help that she sometimes carry around a wand with a star at the tip, that is strikingly reminding of the stereotypical fairy-wand. Another irony of fate - despite the Christkindl being brought over to replace Saint Nicolas, the two currently still coexist in Alsace thanks to people not wanting to abandon the good old bishop. A third fun fact: originally the Christkindl could be played as much by women as by men, due to being a truly androgynous entity. From the 16th century onward, the Saint Nicolas celebrations were replaced in Alsace by parades of teenagers of both sexes dressed in white, going from door to door to give gifts and sing Christmas songs. However you can't have teenage boys and girls go around late at night without getting some problems... And those "Saint Nicolas hook-ups" were a real problem in Alsace, you have records from the 17th and 18th centuries pointing out how authorities have to try to refrain all the Christkindl from... well you know.]

The next entity presented is the famous Pays Basque character of Olentzero, whose appearance is that of a coal-man. Well a bizarre coal man - he has a bag filled with coal in one hand, a sickle in the other, a large beard on his face and a béret on his head. According to the Basque-version of the Nativity lore, he lived at the top of the mountains but saw in the sky the announcement of the birth of Kixmi (Basque name for Jésus), and he descended from his mountains to announce the good news. While he is the gift-giver of Pays Basque, leaving gifts for children in the night between the 24th and 25th of December, entering in the house by the chimney ; he is also a bogeyman figure, as he was a scary-looking man who was said to take away in a bag naughty children. As with everything Basque, Olentzero is actually a pre-Christian figure, as the very name of the character is related to the "pagan" winter solstice celebrations of the old Basque religion.

[Again, time to bring some more information from other websites to make sure I give a more complete portrait:

Long story short, because the Basque folklore is very well documented and I can't spend too much time on this, the Olentzero (or Olentzaro, Orentzaro, Omentzaro, Orantzaro...) is at the same time the Basque name for Christmas and the Basque figure of the coal-man that brings gifts during Christmas. He is supposed to be a grotesque character - rude, fat, dirty, gluttonous, his face blackened by soot, with worn-out clothes... He is basically a caricature of mountain-men and forest-men. Sometimes he is even given monstrous traits such as "having as many eyes as there are days in the year, plus one" - which is reminding of a French being of the New Year folklore called L'Homme aux Nez who also has as many noses as there are days in the year...He typically holds branches of gorse in one hand and a sickle in the other.

He comes down from the mountains, enters houses by chimneys, goes into the kitchen once everybody goes to sleep to eat all leftover food, and he warms himself by the fire - either you had to leave a log burning just for him, either he used the flames of the fire to burn his gorse branches. In fact, "olentzero" was also the name of a special log that was left bruning in the fireplace from Christmas to the 1st or 6th of January. This theme of the "coal man" of winter or the burning of branches all answers to a deep motif of bringing back light and heat in the heart of the cold and the dark. Him holding a sickle has made people draw parallel between him and the figure of Saturn/Kronos.

In fact, there is an old tradition, long before the Olentzero was embodied by a disguised man or by a mannequin paraded through the villages, to embody the character simply by the sickle. The sickle hanged by the chimney, as a threat to all disobedient children, to all lying children, and to all children that refused to go to bed. Another symbol of the Olentzero, outside of the sickle and the coal-sack, is a wine-bag or wine-bottle that he carries around, because to add to the grotesque he is also a drunkard, and according to stories it is because he gets often drunk that his wife regularly beats him. (Because yes the Olentzero has a wife, a character named Mari Domingi and who is typically depicted wearing a medieval regional outfit). However it seems that all this grotesqueness is simply due to the Olentzero being a character from the old Basque mythology that got Christianized - think of how the Dagda of Celtic mythology also got more buffoonish/clownesque/grotesque as time passed. We do know that the roots and origins of the character lie in the valley of Bidassoa...)

Today gone is the creepy bogeyman and grotesque glutton ; the Olentzero has evolved into a kinder, nicer, cleaner incarnation that is closer to the Père Noël traditions. For example he now parades through streets during the day, riding a horse (pottok) or by foot, giving children candies and sweets (including fake-coal actually made of sugar) ; and the legend claims he goes down from the mountain to offer coal and wood-logs to the poor families that can't afford fuel for their fire]

And finally, we find back our good old Père Janvier! Here we have most of the same info as previous. Père Janvier was a Bourgogne character, most present in the Morvan and Nivernais regions up until the 1930s. He brings gifts in the night between the 31st of December and the 1st of January by going through the chimney - chimney which must be decorated with holy and mistletoe. Père Janvier (Father January) typically looks like a skinny old man with a long white beard, dressed in a brown monk-like robe, and he is usually bent due to wearing on his back a heavy wicker basket filled with toys. And he too has for companion the Père Fouettard.

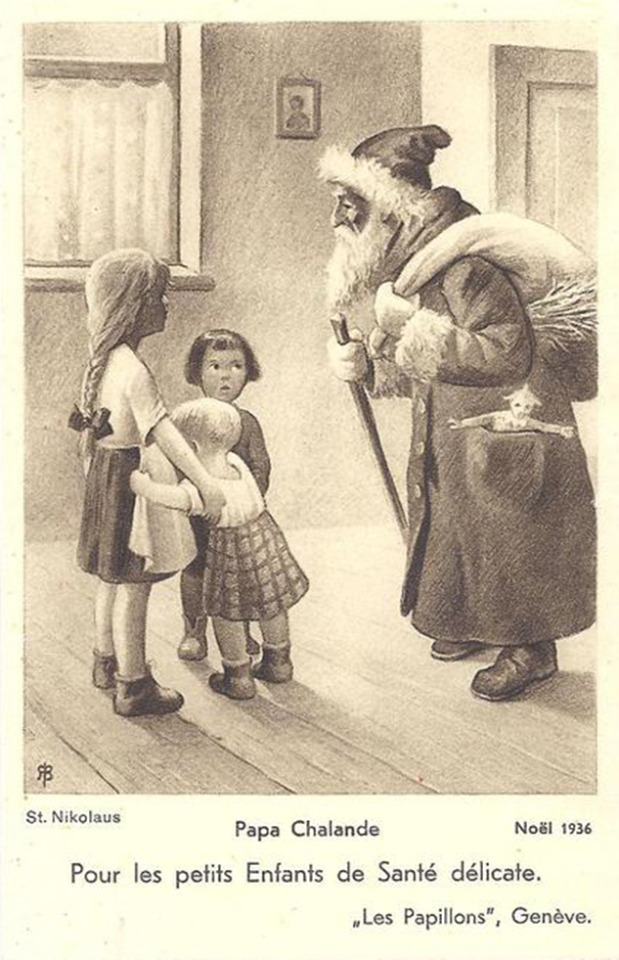

Most interestingly, the website mentions "Père Janvier variations" across France, most notably the Savoie character of Père Chalande, and the Normandie character of Barbassioné.

More information from other website. Le Père Chalande (or Papa Chalande, Daddy Chalande) was indeed a figure of the Savoie region, but also of the Dauphiné, and he was also present in Geneva. Martyne Perrot, in her book "Faut-il croire au Père Noël? Idées reçues sur Noël" even lists the area of action of this figure as: Savoie, Suisse romande, Bresse, Forez, Ardèche, Gard, Lozère and Hérault. He is basically identical to Père Noël because "Chalande" is just an old word for "Noël" (Christmas) in the regional language known as arpitan.

There was a traditional song that went as such: Chalande est venu / Son chapeau pointu / Sa barbe de paille / Cassons les anailles (noisettes) / Mangeons du pain blanc / Jusqu’à Nouvel An. / Il monte dans sa chambre / Il trouve une orange / Il la pluche / Il la mange / On l’appelle le petit gourmand. / Il descend les escaliers / Il se casse le bout du nez / Il va chez le cordonnier / Se faire mettre une pièce au nez / Quand il est malade / Il mange de la salade / Quand il est guéri / Il mange des souris/ Toutes pourries !

I can't translate the full song, but it refers to various traditions. For example leaving an orange for Père Chalande ; Père Chalande wearing a "beard of straw and a pointy hat" (leftovers of Saint Nicolas, especially the pointy hat) ; Père Chalande giving "anailles" (walnuts) to children ; and the habit of placing inside the Christmas log (real log of the fire) chestnuts, so that the burning of the Christmas log doubled as the cooking of the wintery treats. Raymond Christinger wrote in 1965, in a set of research about Geneva folklore, an article studying the character of Chalande, if you know how to read French: here.

While doing Chalande research I stumbled upon a Swiss theory brought forward by a journalist named Bernard Léchot - I don't know how accurate this is when it comes to actual evolution of Christmas figures, but here it is. According to him, the Christmas archetype of the "Old Man" actually comes 18th century Germany. In this era of rationalism, the German Protestant landgraves decided to introduce some laicity to their country, and so cut-off all characters close to Christianity from their Christmas celebrations (from Saint Nicholas to Christkindl). As a result, pagan figures returned, including the Old Man in the shape of Weihnachtsmann. Which then spread to other European countries, each land creating its variation: Bonhomme Noël in France, Father Christmas in England, Père Chalande in Savoie.

As for the Barbassioné of Normandie, I found nothing about him. As in every says it is the Normandie name of Père Noël, but he doesn't have any specific thing to his character.

To conclude, I will link you to a page documenting a Père Noël/Christmas beings exposition that collected various visuals of the history of the Christmas gift-givers through time, right here.

And through it you will see the evolution from the "Scandinavian ancestors" (Thor and Odin) and Saint Nicolas (celebrated in Germanic countries and the Alsace region), to the American Santa Claus and the British "Old Father Christmas", passing by the Germanic Knecht Ruprecht, the also Germanic Weihnachtsmann, the Christinkindel (of Germany, Belgium and Alsace), the Jultomte of Sweden, and the Enfant Jésus/Child-Jesus of France and Italy...

Without forgetting the French Bonhomme Noël, the Italian Befana, the regional ancestors of Père Noël (Tante Arie, Père Chalande, or the Breton Ted Nedelec), the Russian Ded Moroz, and Mère Noël (Mother Christmas)... With additional sections about Santa Claus in advertisements, the theme of "outlaw Father Christmas", Père Noël during the World Wars, and more...

#french folklore#father christmas#père noël#saint nicolas#christkindl#père chalande#père janvier#christmas folklore#olentzero#basque folklore#hans trapp#père fouettard#christmas art#santa claus#christmas

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

« This Little Light of Mine « is a traditional gospel that was written in the 1920s, often attributed to Harry Dixon Loes. The song has become emblematic in the civil rights movement.

.

With this artwork I place my hope in justice and civil rights, also in a kind of magical spirit. The black Madonna is inspired by Erzulie Dantor, the vodoo protector of women and kids. I believe in the magical apotropaic strength attributed to black Madonna. This artwork is a pray and a talisman for a better future.

.

The black Madonna is wearing the justic blindfold and her kid is the future. The horse helps her to go through worlds and difficulties.

She is protective for all minorities and many of the people drawn are friends of mine.

. The whole text of the gospel is in the heart keeping by American eagles. It could recall Pennsylvanian Dutch folk art but actually inspiration came from Alsacian folk art, which became partly Pennsylvanian Dutch in USA. I’m Alsacian. Those are my roots and I show the more and more sadly broken link between USA and us, European.

However it’s an artwork of hope, from the heart.

.

You can find it on booth @galerielemetais in @outsiderartfair New York till Sunday.

.

#outsiderartfaiir#oaf#this little light of mine#drawing#art#black Madonna#outsider art#minamond#folk art

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Alsacian Chimney sweep, France, Bruno Boissier

#alsacian#french#europe#france#western europe#traditional clothing#traditional fashion#cultural clothing#folk clothing

80 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mini Review: "The Liberty Scarf" Novella Anthology

I finished reading this historical fiction/romance anthology last week! The Liberty Scarf by authors Aimie K. Runyan, J’nell Ciesielski, and Rachel McMillan is a new release with depth, realistic characters, and hopeful romance. These three intertwining stories set during WWI tell the roles and experiences of three couples from varying backgrounds and countries (hello, French/Alsacian heroes!).…

View On WordPress

#Aimie K. Runyan#Book#book review#Historical Fiction#Historical Romance#J&039;nell Ciesielski#Mini Review#Rachel McMillan#read#Reading#Romance#The Liberty Scarf#WWI

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

🍪 If you were a cookie, what kind would you be?

mmmm I think I'd be something from my home place. Like some sort of bredele

During holidays season it's the proper custom for all Alsacian mothers and grandmothers to bake like, 10 000 tons of these little fuckers and give them to everyone around them.

Bredeles are amazing and buttery, and you can keep them for a LONG time!

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

I was originally gonna post this as an addition to someone else's post about eating raw meat safely but I realized I just wanted to talk about Parisa so here's my spiel

I know I know it's not texturally the same as raw beef but if you just want to eat raw beef then tartare is a classic and you can do a fair amount with it. Around where I live there's a local dish made by the descendants of Alsacian immigrants called Parisa which is typically raw beef cured in lime juice, cheese, jalapeño, onions, sometimes garlic or serranos are added too, it's seasoned by choice. Goes great with saltine crackers and tabasco sauce. (And any leftovers can be made into a queso or scrambled with egg, mmmm)

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hallo zusamme, today a memory from my childhood that has to do with one of my adult passion : ornithology !

When I was 6-7 years old we had several field class in the alsacian countryside and here we were offered the following "craft" project : we were each given one barn owl's pellet to dig into. Pellets are coughed out by the owl and contain all it is they couldn't digest , so the bones of the small critters they feed upon . We were given a black sheet of canson paper to stick those tiny bones onto as a souvenir ! - and probably to learn about the barn owl's role as a regulator of small rodent populations ?? Anyways now looking back this was so metal xD

Love strygidae 😍🦉⭐🌛✨🌙🌠

0 notes

Text

Summer, Diana Surprised by Actaeon. (Eugène Delacroix, 1856 - 1863)

This painting belongs to a set of four allegories of the four seasons, personified in the characters of classical mythology deities (The Hartmann's Four Seasons). They were executed by Delacroix between 1856 and 1863, and ordered by the Alsacian industrialist Frederick Hartmann.

The story of Diana and Actaeon is a classical myth from ancient Greece. Actaeon was a hunter who stumbled upon the goddess Diana while she was bathing in a forest pool. Outraged by his intrusion, Diana splashed water on him and, as punishment, turned him into a stag. Actaeon's own hunting dogs, recognizing their master, chased and killed him. This story is often interpreted as a cautionary tale about the consequences of hubris or arrogance, as well as a celebration of the power and majesty of the goddess Diana.

Media: oil, canvas

Dimensions: 194 x 165 cm

Exhibit in the Museu de Arte de São Paulo - São Paulo, Brazil.

8 notes

·

View notes