#afro-atlantic histories

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

0 notes

Text

53 notes

·

View notes

Text

Music of African heritage in Cuba derives from the musical traditions of the many ethnic groups from different parts of West and Central Africa that were brought to Cuba as slaves between the 16th and 19th centuries. Members of some of these groups formed their own ethnic associations or cabildos, in which cultural traditions were conserved, including musical ones. Music of African heritage, along with considerable Iberian (Spanish) musical elements, forms the fulcrum of Cuban music.

Much of this music is associated with traditional African religion – Lucumi, Palo, and others – and preserves the languages formerly used in the African homelands. The music is passed on by oral tradition and is often performed in private gatherings difficult for outsiders to access. Lacking melodic instruments, the music instead features polyrhythmic percussion, voice (call-and-response), and dance. As with other musically renowned New World nations such as the United States, Brazil and Jamaica, Cuban music represents a profound African musical heritage.

Clearly, the origin of African groups in Cuba is due to the island's long history of slavery. Compared to the USA, slavery started in Cuba much earlier and continued for decades afterwards. Cuba was the last country in the Americas to abolish the importation of slaves, and the second last to free the slaves. In 1807 the British Parliament outlawed slavery, and from then on the British Navy acted to intercept Portuguese and Spanish slave ships. By 1860 the trade with Cuba was almost extinguished; the last slave ship to Cuba was in 1873. The abolition of slavery was announced by the Spanish Crown in 1880, and put into effect in 1886. Two years later, Brazil abolished slavery.

Although the exact number of slaves from each African culture will never be known, most came from one of these groups, which are listed in rough order of their cultural impact in Cuba:

The Congolese from the Congo Basin and SW Africa. Many ethnic groups were involved, all called Congos in Cuba. Their religion is called Palo. Probably the most numerous group, with a huge influence on Cuban music.

The Oyó or Yoruba from modern Nigeria, known in Cuba as Lucumí. Their religion is known as Regla de Ocha (roughly, 'the way of the spirits') and its syncretic version is known as Santería. Culturally of great significance.

The Kalabars from the Southeastern part of Nigeria and also in some part of Cameroon, whom were taken from the Bight of Biafra. These sub Igbo and Ijaw groups are known in Cuba as Carabali,and their religious organization as Abakuá. The street name for them in Cuba was Ñáñigos.

The Dahomey, from Benin. They were the Fon, known as Arará in Cuba. The Dahomeys were a powerful group who practised human sacrifice and slavery long before Europeans arrived, and allegedly even more so during the Atlantic slave trade.

Haiti immigrants to Cuba arrived at various times up to the present day. Leaving aside the French, who also came, the Africans from Haiti were a mixture of groups who usually spoke creolized French: and religion was known as vodú.

From part of modern Liberia and Côte d'Ivoire came the Gangá.

Senegambian people (Senegal, the Gambia), but including many brought from Sudan by the Arab slavers, were known by a catch-all word: Mandinga. The famous musical phrase Kikiribu Mandinga! refers to them.

Subsequent organization

The roots of most Afro-Cuban musical forms lie in the cabildos, self-organized social clubs for the African slaves, and separate cabildos for separate cultures. The cabildos were formed mainly from four groups: the Yoruba (the Lucumi in Cuba); the Congolese (Palo in Cuba); Dahomey (the Fon or Arará). Other cultures were undoubtedly present, more even than listed above, but in smaller numbers, and they did not leave such a distinctive presence.

Cabildos preserved African cultural traditions, even after the abolition of slavery in 1886. At the same time, African religions were transmitted from generation to generation throughout Cuba, Haiti, other islands and Brazil. These religions, which had a similar but not identical structure, were known as Lucumi or Regla de Ocha if they derived from the Yoruba, Palo from Central Africa, Vodú from Haiti, and so on. The term Santería was first introduced to account for the way African spirits were joined to Catholic saints, especially by people who were both baptized and initiated, and so were genuine members of both groups. Outsiders picked up the word and have tended to use it somewhat indiscriminately. It has become a kind of catch-all word, rather like salsa in music.

The ñáñigos in Cuba or Carabali in their secret Abakuá societies, were one of the most terrifying groups; even other blacks were afraid of them:

Girl, don't tell me about the ñáñigos! They were bad. The carabali was evil down to his guts. And the ñáñigos from back in the day when I was a chick, weren't like the ones today... they kept their secret, like in Africa.

African sacred music in Cuba

All these African cultures had musical traditions, which survive erratically to the present day, not always in detail, but in the general style. The best preserved are the African polytheistic religions, where, in Cuba at least, the instruments, the language, the chants, the dances and their interpretations are quite well preserved. In few or no other American countries are the religious ceremonies conducted in the old language(s) of Africa, as they are at least in Lucumí ceremonies, though of course, back in Africa the language has moved on. What unifies all genuine forms of African music is the unity of polyrhythmic percussion, voice (call-and-response) and dance in well-defined social settings, and the absence of melodic instruments of an Arabic or European kind.

Not until after the Second World War do we find detailed printed descriptions or recordings of African sacred music in Cuba. Inside the cults, music, song, dance and ceremony were (and still are) learnt by heart by means of demonstration, including such ceremonial procedures conducted in an African language. The experiences were private to the initiated, until the work of the ethnologist Fernando Ortíz, who devoted a large part of his life to investigating the influence of African culture in Cuba. The first detailed transcription of percussion, song and chants are to be found in his great works.

There are now many recordings offering a selection of pieces in praise of, or prayers to, the��orishas. Much of the ceremonial procedures are still hidden from the eyes of outsiders, though some descriptions in words exist.

Yoruba and Congolese rituals

Main articles: Yoruba people, Lucumi religion, Kongo people, Palo (religion), and Batá

Religious traditions of African origin have survived in Cuba, and are the basis of ritual music, song and dance quite distinct from the secular music and dance. The religion of Yoruban origin is known as Lucumí or Regla de Ocha; the religion of Congolese origin is known as Palo, as in palos del monte.[11] There are also, in the Oriente region, forms of Haitian ritual together with its own instruments and music.

In Lucumi ceremonies, consecrated batá drums are played at ceremonies, and gourd ensembles called abwe. In the 1950s, a collection of Havana-area batá drummers called Santero helped bring Lucumí styles into mainstream Cuban music, while artists like Mezcla, with the lucumí singer Lázaro Ros, melded the style with other forms, including zouk.

The Congo cabildo uses yuka drums, as well as gallos (a form of song contest), makuta and mani dances. The latter is related to the Brazilian martial dance capoeira

#african#afrakan#kemetic dreams#africans#brownskin#brown skin#afrakans#african culture#fitness#afrakan spirituality#afro cuban music#afro cuban#igbo#yoruba#congo#african music

193 notes

·

View notes

Text

Black people have a long history in Maine, including:

The American Revolution

Some Black people fought for the British, while others fought for the emerging United States.

The Underground Railroad

African Americans in Maine were conductors on the Underground Railroad, helping enslaved people escape to Canada.

The anti-slavery movement

African Americans in Maine were leaders in the anti-slavery movement, founding and leading local organizations.

The maritime industry

Black mariners made up 15% of seamen on the Atlantic coast in the early 1800s.

The Cummings family

The Cummings family lived in the Valley Street neighborhood of Portland and worked for the railroad.

Robert Benjamin Lewis

Lewis wrote Light and Truth, an Afro-centric history of the world based on theology texts. He also invented the "hair picker", which was used in Maine's shipyards.

Macon Bolton Allen

Allen became the first African-American lawyer in the United States when he passed the bar exam in Portland in 1844

#black tumblr#black literature#black history#black excellence#black community#civil rights#black history is american history#civil rights movement#black girl magic#blackexcellence365#maine#united states

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

nov 9 - nov 13 readings

hi! this is reaux (she/they)! as many of you know, BFP is slowly waking up and will be undergoing a full makeover in the coming months. in the mean time, to help get back into the pattern of posting and to continue to share resources, i want to start posting what i read each week!

without further ado, here is everything i've been learning from and engaging with so far just between last saturday night [nov 9, 2024] and right now [wednesday afternoon, nov 13, 2024]! i tried to post this on tiktok @/edgeofeden.17 (go check me out for cool political talks and reading recs!) with my reactions as well, but they said it violated community guidelines :(

journal article: The House on Bayou Road: Atlantic Creole Networks in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries

wikipedia: Plaçage

wikipedia: Signare

paperback book: Africans In Colonial Louisiana: The Development of Afro-Creole Culture in the Eighteenth-Century

article: Why Is Gen Z So Sex-Negative?: A prehistory of the Puriteen.

article: Policy-makers must not look to the “Nordic model” for sex trade legislation

article: Sex workers face unique challenges when trying to unionize: Anti-sex work stigma and labor status create roadblocks in sex workers’ fight against the industry status quo

wikipedia: Decriminalization of sex work

short youtube video: "Decriminalization of sex work does not mean the decriminalization of human trafficking."

short youtube video: What About Legalization? Decriminalization is the only solution

short youtube video: Dis/Ability and Sex Work Decriminalization

short youtube video: "Helping people through police is inherently coercive." - Gilda Merlot

wikipedia: Page Act of 1875

essay: Uses of the Erotic: The Erotic as Power by Audre Lorde

wikipedia: Erotic Capital

long youtube video: KATHERINE MCKITTRICK: Curiosities, Wonder, and Black Methodologies // 09.14.20

journal article: Black life is Not Ungeographic! Applying a Black Geographic Lens to Rural Education Research in the Black Belt

journal article: Black matters are spatial matters: Black geographies for the twenty-first century

journal article: Unspoken Grammar of Place: Anti-Blackness as a Spatial Imaginary in Education

short video: Chicago Works | Andrea Carlson: Shimmer on Horizons

zine: Evaluating What Skills You Can Bring to Radical Organizing

diagram + workbook?: The Social Change Ecosystem Map (2020)

essay: How to Build Language Justice

guide: Anti-Oppressive Facilitation for Democratic Process: Making Meetings Awesome for Everyone

radical resource library: Center for Liberatory Practice & Poetry

short essay: The Short Instructional Manifesto for Relationship Anarchy

essay/blog post: Access Intimacy: The Missing Link

i think that's everything? whew. let's see how i finish off the week! if you need PDFs for anything i didn't directly link, lmk and i'll find a way to get it to you. might upload it to my google drive or something!

--

topics: Louisiana Creole history + heritage, women of color + erotic capital, sex work decriminalization, Black geography, revolutionary organizing, language, relationship anarchy, disability, intimacy

#reaux speaks#resources#louisiana creole#creole#women of color#audre lorde#decriminalization#geography#landscape painting#organizing#community organizing#language#disability#accessibility#intimacy#relationship anarchy#anarchism#marriage#academia#political education#zine#skills

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rubem Valentim - Afro-atlantic constructions - MASP 2018

Afro-Atlantic Constructions reproduces 99 artworks by the painter, sculptor and engraver Rubem Valentim (Salvador, Brazil, 1922 – São Paulo, Brazil, 1991), a key figure in 20th century Brazilian art and afro-atlantic histories. Edited by Adriano Pedrosa and Fernando Oliva, this catalog complements the exhibition with the same title at Museu de Arte de São Paulo Assis Chateaubriand (MASP), curated by Oliva.

Paperback, 20,5x27,5cm, 288p, English, MASP, 2018

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Dutch King apologizes for Netherlands’ role in slavery.”

The Dutch/Netherlands abducted slaves from West Africa; hosted the Dutch West India Company; operated an extensive profitable sugar plantation industry built on slave labor; and established colonies in the greater Caribbean region including sites at Aruba, Curaçao, Sint Maarten, Bonaire, and the adjacent “Wild Coast” (land between the Orinoco and Amazon rivers, including Guyana and Suriname). Many of these places remained official colonies until between the 1950s and 1990s.

---

Scholarship on resistance to Dutch practices of slavery, colonialism, and imperialism in the Caribbean:

“Decolonization, Otherness, and the Neglect of the Dutch Caribbean in Caribbean Studies.” Margo Groenewoud. Small Axe. 2021.

“Women’s mobilizations in the Dutch Antilles (Curaçao and Aruba, 1946-1993).” Margo Groenewoud. Clio. Women, Gender, History No. 50. 2019.

“Black Power, Popular Revolt, and Decolonization in the Dutch Caribbean.” Gert Oostindie. In: Black Power in the Caribbean. Edited by Kate Quinn. 2014.

“History Brought Home: Postcolonial Migrations and the Dutch Rediscovery of Slavery.” Gert Oostindie. In: Post-Colonial Immigrants and Identity Formations in the Netherlands. Edited by Ulbe Bosma. 2012.

“Other Radicals: Anton de Kom and the Caribbean Intellectual Tradition.” Wayne Modest and Susan Legene. Small Axe. 2023.

Di ki manera? A Social History of Afro-Curaçaoans, 1863-1917. Rosemary Allen. 2007.

Creolization and Contraband: Curaçao in the Early Modern Atlantic World. Linda Rupert. 2012.

“The Empire Writes Back: David Nassy and Jewish Creole Historiography in Colonial Suriname.” Sina Rauschenbach. The Sephardic Atlantic: Colonial Histories and Postcolonial Perspectives. 2018.

“The Scholarly Atlantic: Circuits of Knowledge Between Britain, the Dutch Republic and the Americas in the Eighteenth Century.” Karel Davids. 2014. And: “Paramaribo as Dutch and Atlantic Nodal Point, 1640-1795.” Karwan Fatah-Black. 2014. And: Dutch Atlantic Connections, 1680-1800: Linking Empires, Bridging Borders. Edited by Gert Oostindie and Jessica V. Roitman. 2014.

Decolonising the Caribbean: Dutch Policies in a Comparative Perspective. Gert Oostindie and Inge Klinkers. 2003. And: “Head versus heart: The ambiguities of non-sovereignties in the Dutch Caribbean.” Wouter Veenendaal and Gert Oostindie. Regional & Federal Studies 28(4). August 2017.

Tambú: Curaçao’s African-Caribbean Ritual and the Politics of Memory. Nanette de Jong. 2012.

“More Relevant Than Ever: We Slaves of Suriname Today.” Mitchell Esajas. Small Axe. 2023.

“The Forgotten Colonies of Essequibo and Demerara, 1700-1814.” Eric Willem van der Oest. In: Riches from Atlantic Commerce: Dutch Transatlantic Trade and Shipping, 1585-1817. 2003.

“Conjuring Futures: Culture and Decolonization in the Dutch Caribbean, 1948-1975.” Chelsea Shields. Historical Reflections / Reflexions Historiques Vol. 45 No. 2. Summer 2019.

“’A Mass of Mestiezen, Castiezen, and Mulatten’: Fear, Freedom, and People of Color in the Dutch Antilles, 1750-1850.” Jessica Vance Roitman. Atlantic Studies 14, no. 3. 2017.

---

This list only covers the Caribbean.

But outside of the region, there is also the legacy of the Dutch East India Company; over 250 years of Dutch slavers and merchants in Gold Coast and wider West Africa; about 200 years of Dutch control in Bengal (the same region which would later become an engine of the British Empire’s colonial wealth extraction); over a century of Dutch control in Sri Lanka/Ceylon; Dutch operation of the so-called “Cultivation System” (”Cultuurstelsei”) in the nineteenth century; Dutch enforcement of brutal forced labor regimes at sugar plantations in Java, which relied on de facto indentured laborers who were forced to sign contracts or obligated to pay off debt and were “shipped in” from other islands and elsewhere in Southeast Asia (a system existing into the twentieth century); the “Coolie Ordinance” (”Koelieordonnanties”) laws of 1880 which allowed plantation owners to administer punishments against disobedient workers, resulting in whippings, electrocutions, and other cruel tortures (and this penal code was in effect until 1931); and colonization of Indonesian islands including Sumatra and Borneo, which remained official colonies of the Netherlands until the 1940s.

162 notes

·

View notes

Text

i am not trying to deny the history of slavery in SWANA countries, or deny the cultures of anti-Blackness and colourism that exist across the diaspora and region because those are 100% compulsory to address. but its very weird that the two times i've seen the legacy of the Arab slave trade brought up in social media discourses were a) in 2020-21 to undermine Black people who were discussing the legacy of the Atlantic slave in the US, UK and Caribbean, and b) in 2023-24 as a way for racists and zionists to somehow justify or discount the ethnic cleansing of Palestinians. and all i can say is the racism and anti-Blackness experienced by Black people in the SWANA region shouldn't be weaponised to discredit the oppression of other Black and Brown people. 1) because it trivialises the struggles of Black SWANA people into a "gotcha" card that dehumanises them and 2) using the history of SWANA anti-Blackness to undermine calls for a free Palestine that erases Afro-Palestinians who are also victims of Israel's genocide, not to mention Israel's treatment of Black Jewish settlers. Anti-Black racism in the SWANA region perpetrated by non-Black SWANA people is a serious issue. it is not a justification for genocide, or your secret weapon to perpetrate anti-Black racism elsewhere.

34 notes

·

View notes

Note

original anon here tysm for the recs ! if the marxist frameworks was too limiting im also completely fine w general postcolonial botany readings on the topic :0

A Spiteful Campaign: Agriculture, Forests, and Administering the Environment in Imperial Singapore and Malaya (2022). Barnard, Timothy P. & Joanna W. C. Lee. Environmental History Volume: 27 Issue: 3 Pages: 467-490. DOI: 10.1086/719685

Planting Empire, Cultivating Subjects: British Malaya, 1786–1941 (2018). Lynn Hollen Lees

The Plantation Paradigm: Colonial Agronomy, African Farmers, and the Global Cocoa Boom, 1870s--1940s (2014). Ross, Corey. Journal of Global History Volume: 9 Issue: 1 Pages: 49-71. DOI: 10.1017/S1740022813000491

Cultivating “Care”: Colonial Botany and the Moral Lives of Oil Palm at the Twentieth Century’s Turn (2022). Alice Rudge. Comparative Studies in Society and History Volume: 64 Issue: 4 Pages: 878-909. DOI: 10.1017/S0010417522000354

Pacific Forests: A History of Resource Control and Contest in Solomon Islands, c. 1800-1997 (2000). Bennett, Judith A.

Thomas Potts of Canterbury: Colonist and Conservationist (2020). Star, Paul

Colonialism and Green Science: History of Colonial Scientific Forestry in South India, 1820--1920 (2012). Kumar, V. M. Ravi. Indian Journal of History of Science Volume: 47 Issue 2 Pages: 241-259

Plantation Botany: Slavery and the Infrastructure of Government Science in the St. Vincent Botanic Garden, 1765–1820 (2021). Williams, J'Nese. Berichte zur Wissenschaftsgeschichte Volume: 44 Issue: 2 Pages: 137-158. DOI: 10.1002/bewi.202100011

Angel in the House, Angel in the Scientific Empire: Women and Colonial Botany During the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries (2020). Hong, Jiang. Notes and Records: The Royal Society Journal of the History of Science Volume: 75 Issue: 3 Pages: 415-438. DOI: 10.1098/rsnr.2020.0046

From Ethnobotany to Emancipation: Slaves, Plant Knowledge, and Gardens on Eighteenth-Century Isle de France (2019). Brixius, Dorit. History of Science Volume: 58 Issue: 1 Pages: 51-75. DOI: 10.1177/0073275319835431

African Oil Palms, Colonial Socioecological Transformation and the Making of an Afro-Brazilian Landscape in Bahia, Brazil (2015). Watkins, Case. Environment and History Volume: 21 Issue: 1 Pages: 13-42. DOI: 10.3197/096734015X14183179969700

The East India Company and the Natural World (2015). Ed. Damodaran, Vinita; Winterbottom, Anna; Lester, Alan

Colonising Plants in Bihar (1760-1950): Tobacco Betwixt Indigo and Sugarcane (2014). Kerkhoff, Kathinka Sinha

Science in the Service of Colonial Agro-Industrialism: The Case of Cinchona Cultivation in the Dutch and British East Indies, 1852--1900 (2014). Hoogte, Arjo Roersch van der & Pieters, Toine. Studies in History and Philosophy of Science Part C: Studies in History and Philosophy of Biological and Biomedical Sciences Volume: 47 Issue: Part A Pages: 12-22

Trading Nature: Tahitians, Europeans, and Ecological Exchange (2010). Newell, Jennifer

The Colonial Machine: French Science and Overseas Expansion in the Old Regime (2011). McClellan, James E. & Regourd, François

Colonial Botany: Science, Commerce, and Politics in the Early Modern World (2005). Ed. Schiebinger, Londa L. & Swan, Claudia

Plants and Empire: Colonial Bioprospecting in the Atlantic World (2004). Schiebinger, Londa L.

93 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi! So I'm but sure if you've answered this before, I've just found your blog but find it interesting, especially since I'm trying to write stuff for Peaky blinders. I was wondering if you could tell me your take on the use of the word "gypsy" when writing. Because I know it is very controversial and a lot of people say not to use it because it's offensive. And I was just wondering if you could explain why, because I grew up in the US and am not really familiar with the culture and it wasn't really anything I grew up hearing about. So I was just wondering if your could maybe explain why people consider it a slur because I'm really am not sure. I don't want to me rude or anything it's just something I'm genuinely curious about. Because I've seen some people say they think it's offensive and some props say they think it's rude. I was also wondering your take on possibly using it in a Peaky blinders fic, because I think in the shot the Shelby's have use it a few times to describe themselves or when just they're being referenced or because I've heard it was used more in that time. And yeah. I know that was kinda ramblly and I'm not sure if it makes sense but I was just curious on your take about it. You totally don't have to answer though!!! Thanks for reading this!

Hey! I have answered this before, but I'm more than happy to answer it again so thank you so much for this question.

History lesson first:

The word "gypsy" has a few origins in relation to Rroma, so I'll go through the ones I know and work through them.

The first one I'm aware of is the idea Rroma individuals come from Egypt. Many were unsure of our origin but knew we had "strong" features and darker skin. These traits are due to us originating in South India. So the first meaning of the word I know us gypsies from Egypt, which is factually incorrect.

Another reason I'm aware of is the breakdown of the words - to gyp means to steal (or in some definitions to gamble). Throughout history, Rroma as a group were deprived of recourses. Many of us were involved in slavery in Eastern Europe for 400 years, and others were sold in the Atlantic Slave Trade to the Americas (leading to the group Afro-Romani).

If you deprive a group of people of the basic necessities to live, they're going to bargain to get them, maybe even steal. During these times in history, we were known for stealing food and fabrics from richer members of society. Therefore, gaining us the name "gypsies"

It's also important to factor in other ethnic groups that also use the name "gypsy" when in referral to themselves:

1-We have Irish Travellers, to start, who are not Rroma. Irish Travellers are from Ireland and are a whole other ethnic minority. People often confuse Irish Travellers with Rroma due to their similar nomadic lifestyle. Irish Travellers allow themselves to be called gypsies as it was a self-given title centuries ago, inspired by the Rroma definition of gypsy.

2-We also have English Travellers, who are often confused with Romanichal. In England, people are often confused with the difference between English Travellers and Romanichal - and so was I (in full admittance) when I began educating myself on the different types of travellers.

While there are marriages and cultural similarities between English Travellers and Romanichal, they're not at all genetically or historically linked. English Travellers come from Cromwellian times. The English Travellers also have their own views on the word gypsy, and doesn't have any historical nor offensive connections to them.

3-British Romany "Gypsies". British Romany Travellers are a very specific type of Rroma. British Romany Travellers have been in England since 1515 when Rroma began migrating to Europe after their migration from India. They're the descendants of Romany migrants who emigrated from India - therefore, the meaning of the word gypsy to them is in relation to the British's (is that a word?) idea of them coming from Egypt.

4-The Romanichal (Romanichal Travellers) are a Romani subgroup in England and other English-speaking countries. These are not English Travellers as they are descendants of the Rroma who once lived in India. Most Romanichal speak Angloromani - which is a mixed language that blends together both Romani vocabulary and English syntax.

There are around 400,000 Romanichal worldwide, 200,000 living in the United Kingdom, 164,000 living in the United States and the rest living in South Africa, Australia, Canada and New Zealand.

5-Kale (Welsh Roma). The Kale are a group of Romani people in Wales and are often descendants of Abram Wood who was the first Rom to live in Wales in the 18th century. There are around 700-1,000 Kale members of society and speak their own version of Welsh Romani.

6-Romani (also spelt Romany or Rromani depending on where you come from). Romai people live in predominantly Europe and there are around 2-12million worldwide (shocking 10million confusion I know). The language you speak as a Romani person depends on where you live, where your ancestors lived etc as there are hundreds of Romani dialects.

NOW TO ANSWER YOUR QUESTION!

The short answer to your question, which I probably should've put at the start and not the end, is please do not use the word gypsy when relating to travellers as for all "gypsy" groups there is a more specific name used in regard to them.

The word gypsy (also seen as gipsy) is rather ambiguous in dialect use as it doesn't specifically shown who you are in referral to. While some communities such as Irish and English travellers deem the word okay to use, the vast majority of the Rroma community do not.

The word gypsy in reference to the Romani community has connotations of illegality and is known as a racial slur. In 1971, the world Romani Congress unanimously voted to reject the use of the word gypsy due to the stereotypes associated.

The word gypsy was used against the Romani community during significant human parts of history - the Holocaust, the Romani slave trade and the Atlantic slave trade.

HOWEVER

It's also important to keep in regard the use of the word, are you using it to write an 1800s piece? Is your story or piece of text historically accurate, and to use the phrase "Romani People" would be historically inaccurate as that isn't what we were called then.

Are you writing a piece that highlights the issues behind the word, where you aren't calling Romani people it, but instead highlighting the wrong in it.

Are you taking from a place in the early 1900s where Romani people called themselves Romani gypsies because that was the official documentation name given to us.

In summary:

Please don't go about calling Romani people gypsies unless in a historically accurate context.

I spent 20 minutes typing on this post, so thank you so much! I may have to open a window and I'm sweating like a dog in heat and need a break. You definitely gave me a lot of talking points (lol oops), but thank you for that also. All in all, I hope your answer is somewhere in this mess. 💗 May you have a blessed day!

Izzy 💓

#peaky blinders#izabesworld#malfoyzsxpeakyblinders#romani#romani history#romanitalk#romani people#roma#romany awarness#roma in ww1#irish travellers#english travellers

70 notes

·

View notes

Text

Brazil, facing calls for reparations, wrangles with its painful legacy of slavery

The executive manager for institutional relations at a Brazilian state bank took the microphone before roughly 150 people at a forum on slavery’s legacy in his country, which kidnapped more Africans for forced labor than any other nation.

“Today’s Bank of Brazil asks Black people for forgiveness,” André Machado said to the mostly Black audience at the Portela samba school in Rio de Janeiro.

“Directly or indirectly, all of Brazilian society should apologize to Black people for that sad moment in our history,” he said, reading a statement to audience members who sat watching from plastic chairs, their eyes fixed upon him.

Brazil — where more than half the population self-identifies as Black or biracial — has long resisted reckoning with its past. That reluctance has started loosening.

Public prosecutors have begun probing Bank of Brazil, Latin America’s second-largest financial institution by assets, with $380 billion, for its historical links to the slave trade. Their investigation could yield a recommendation, an agreement or filing of legal action, and they invited Bank of Brazil to start a dialogue with Black people at the Portela school in the working-class Madureira neighborhood.

Ghyslaine Almeida e Cunha, a spiritual leader of the Afro-Brazilian religion Umbanda, traveled from the Amazonian city of Belem for what she called “an historic moment.” She welcomed the apology and announcement of measures, though the bank stopped short of pledging compensation.

“I came to say – on Portela’s sacred soil – that, yes, we do want reparations,” said Cunha.

Brazil enslaved more people from Africa than any other country; nearly 5 million kidnapped Africans disembarked in Brazil, more than 12 times the number taken to mainland North America, according to estimates from the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade database. Brazil was the last country in the Western Hemisphere to abolish slavery, in 1888.

Continue reading.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Seen @ LACMA

#lacma#los angeles#afro atlantic histories#kerry james marshall#firelei baez#dalton paula#alison saar#berkeley l hendricks#race in america#race in the americas#transatlantic slave trade#portraits#art#contemporary art#jim crow#resistance#insurrection

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

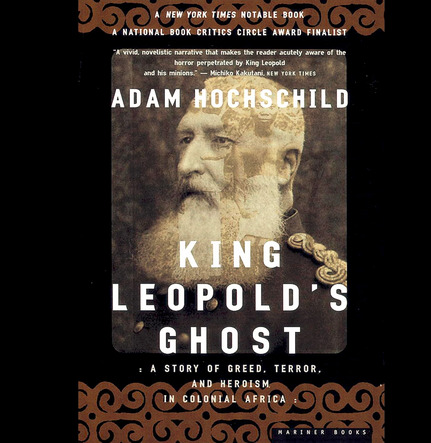

King Leopold's Ghost: A Story of Greed, Terror, and Heroism in Colonial Africa

King Leopold's Ghost: A Story of Greed, Terror, and Heroism in Colonial Africa

In the late 1890s, Edmund Dene Morel, a young British shipping company agent, noticed something strange about the cargoes of his company's ships as they arrived from and departed for the Congo, Leopold II's vast new African colony. Incoming ships were crammed with valuable ivory and rubber. Outbound ships carried little more than soldiers and firearms.

Correctly concluding that only slave labor on a vast scale could account for these cargoes, Morel resigned from his company and almost singlehandedly made Leopold's slave-labor regime the premier human rights story in the world. Thousands of people packed hundreds of meetings throughout the United States and Europe to learn about Congo atrocities. Two courageous black Americans - George Washington Williams and William Sheppard - risked much to bring evidence to the outside world. Roger Casement, later hanged by Britain as a traitor, conducted an eye-opening investigation of the Congo River stations.

Sailing into the middle of the story was a young steamboat officer named Joseph Conrad. And looming over all was Leopold II, King of the Belgians, sole owner of the only private colony in the world.

Reviewer Comment:

This is a tragic history of the Belgian Congo at the turn of the 19th century as the Scramble for Africa began. Adam Hochschild is an American writer and journalist for the New Yorker, NY Times, NY Review of Books and Times Literary Supplement. His work has combined history with human rights advocacy. The events in this book are a shameful chapter in the era of colonialism, of which there were many. It is portrait of Leopold likely to inspire loathing in any who reads it. Beside an account of a colony, it archives the lives of activists who fought to free it. In 1482 Portuguese sailors braved the ocean beyond the Canary Islands and discovered a fresh water flow off the coast of Central Africa. Following a silt trail, fighting a fast current, they found the mouth of a vast river. Nine years later priests and emissaries arrived and began the first European settlement in a black African kingdom. Small scale slavery existed but a booming slave trade developed with the Americas to grow cotton and cane. During the 19th century slavery was abolished in Britain and America yet continued in Afro-Arab commerce. Leopold II (1835-1909) was the King of the Belgians and obsessed with obtaining colonies. He studied records of conquistadores in Seville, sailed to India, Ceylon, Burma and Java noting lucrative concerns. Plantations depended on forced labor to lift profits and civilize the lazy natives. He looked at land in Brazil, Argentina, Phillipines and Taiwan. Frustrated in these attempts he focused his sights on Africa. Humanitarian pretenses of freeing Africa from slavery and bringing enlightenment to the Dark Continent disguised his dreams of ivory and rubber.

Henry Morton Stanley led a Dickensonian life. Abandoned to a poorhouse as a child he sailed to America and became a soldier in the Civil War, first for the Confederacy and then for the Union. He became a newspaper correspondent and tracked down explorer David Livingstone during his search for the source of the Nile. Returning to Africa in 1874 to map the waterways of the interior he discovered the source of the Congo River. Upon reaching the Atlantic he was hired by Leopold to establish trading posts and railroads and force tribal leaders to cede land. King Leopold and an American ambassador formed fake philanthropic associations for evangelism and scientific study of the region. In 1884 he lobbied the US to recognize the Congo Free State, in reality a colony owned by himself. Post-Civil War politicians were interested in sending freed slaves back to Africa. The area annexed was as large as the land east of the Mississippi while Belgium was half the size of West Virginia. In diplomatic deals France and Germany fell into line and Britain became invested. The challenge was to carry steamboats over the falls. By 1890 trading stations had been secured. Elephants were hunted by conscripted natives or their ivory simply seized. Vacant land was leased to private companies with shares of the profit retained. Legions of Africans were used as porters through jungles chained by the neck. So many were needed agents began to purchase them from the slave traders they purported to abolish. Security officers of the Free State were Europeans, half from Belgium, with soldiers drawn from the Congo. They chose to join the conquerors, their spears and muskets no match for machine guns. Leopold's agents set up orphanages run by Catholic missions to train future troops. Captured women were kept in harems by agents or held hostage to coerce their men to harvest rubber. Discipline was enforced with the whip and counted in severed hands of dead rebels. To exact penalties entire villages were often burned down. The human toll over a quarter century is not known for certain but is estimated at 10 million, or half of the population. The causes included murder, starvation and disease (due to inhuman working conditions) and lowered birth rates. Joseph Conrad was briefly a steamboat pilot on the Congo, his novel 'Heart of Darkness' a depiction of what he saw. Displays of decapitated heads were not only a metaphorical critique of colonialism. Black Americans G.W. Williams, a polymath, and W.H. Sheppard, a missionary, exposed the conditions in 1890. Few voices of natives were recorded but are included where possible. In 1898 British shipping clerk E. D. Morel and Irish diplomat R. Casement suspected forced labor and began campaigns. Mark Twain and Sir Arthur Conan Doyle wrote exposés on Leopold. As opinion turned Leopold waged propaganda wars. Self-appointed commission reports criticized his regime. The only option was to sell Congo to Belgium; self rule was unthinkable. In 1908 Leopold was given a billion dollar bonus and billions remained in his name. Wild rubber was replaced with farms. Atrocities declined but forced labor persisted. Head taxes kept people in plantations and mines before independence in 1960. PM Lumumba, seen as hostile to business, was shot with Belgian and US assistance and replaced by kleptocrat Mobuto until 1997.

CLICK HERE TO DOWNLOAD THIS BOOK FROM THE BLACK TRUEBRARY

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

in the spirit of black history month & my book COOK LIKE YOUR ANCESTORS, the Sunnyvale library is hosting me for a virtual intuitive cooking demo <3

we'll discuss the relationship with food + memory, seed saving + survival, featuring black eyed peas + the afro-atlantic diaspora, all while cooking up some Kenyan kunde.

it's no cost, and the food is fully plant based. get your grocery list & sign up at: rb.gy/4bpoal

(this is saturday, so soak your peas now!)

#resources#food#demonstrations#cooking#recipe#kenya#africa#black history month#cook like your ancestors#history#diaspora#seeds#black eyed peas#event#invite

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

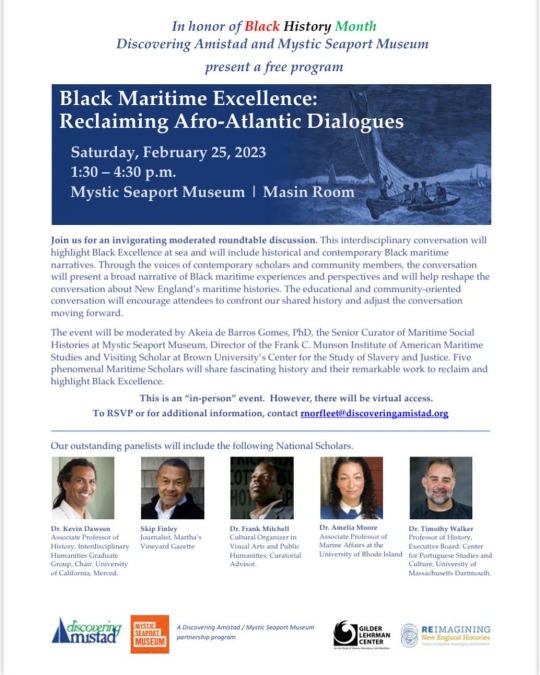

At 1:30 Eastern Standard Time! Free and via Zoom, you can click on the link to register:

Black African Excellence: Reclaiming Afro Atlantic Dialogues

“This interdisciplinary conversation will highlight Black Excellence at sea and will include historical and contemporary Black maritime narratives. Through the voices of contemporary scholars and community members, the conversation will present a broad narrative of Black maritime experiences and perspectives and will help reshape the conversation about New England’s maritime histories. The educational and community-oriented conversation will encourage attendees to confront our shared history and adjust the conversation moving forward. The event will be moderated by Akeia de Barros Gomes, PhD, the Senior Curator of Maritime Social Histories at Mystic Seaport Museum, Director of the Frank C. Munson Institute of American Maritime Studies and Visiting Scholar at Brown University’s Center for the Study of Slavery and Justice. Five phenomenal Maritime Scholars will share fascinating history and their remarkable work to reclaim and highlight Black Excellence.”

Come check it out!

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Bahamas gained full independence within the Commonwealth of Nations on July 10, 1973.

Bahamas Independence Day

We are celebrating Bahamas Independence Day on July 10. The Bahamas is a small island nation south of Florida and north of Cuba. The island nation of the Bahamas is the ‘Commonwealth of The Bahamas.’ It is a sovereign country in the Lucayan Archipelago in the Atlantic. The country gained its independence on July 10, 1973. Prince Charles himself handed over the documentation to Prime Minister Lynden Pindling, officially making the Bahamas a fully independent nation. We celebrate the nation’s culture, traditions, and natural beauty on this day. Join us and be a part of the Bahamas Independence Day celebrations.

History of Bahamas Independence Day

The history of the Bahamas Islands starts with the Lucayans inhibiting the islands between 500 A.D. and 800 A.D. The Lucayans were a branch of the Tainos from the Caribbean islands at the time. For many centuries, they lived on their own without foreign interference until 1492. Christopher Columbus saw the islands, and Spanish ships followed him. They enslaved the native population, resulting in the island becoming deserted in 1513. English colonists started settling on the island in 1648.

The shallow water of the island made it difficult for the large ships to reach it. But it also provided easy passage to smaller ships. Pirates took advantage of this geography, and as a result, the place became a haven for pirates. Nassau on New Providence Island in the Bahamas was the stronghold of a loose confederacy of pirates between 1706 and 1718. The British took harsh measures, and the Bahamas became a colony in 1718. Further migrations happened after the American Revolutionary War. Thousands of American loyalists received land grants in the Bahamas and settled there. They also brought with them forced laborers and established plantations. Soon, the Bahamas was populated by enslaved African people. The Bahamas became a haven for the freed slaves when it abolished slavery. Today, 90% of the population are Afro-Bahamians.

The Bahamas then gained independence in 1973, led by Sir Lynden O. Pindling. Pindling’s actions earned him the name “Father of the Nation” of the Bahamas. He was pivotal in the independence of the nation. Queen Elizabeth II became the “Queen of the Nation.” Most of the country’s economy is driven by tourism and offshore finance.

Bahamas Independence Day timeline

500 A.D. — 800 A.D.

Lucayans in the Bahamas

The Lucayans reach the Bahamas after crossing the ocean from Cuba with canoes.

1492

The First Sighting of the Bahamas

Columbus discovers the Bahamas during his journey to the New World.

1706 — 1718

Pirates in New Providence Island

New Providence island hosts the stronghold of the Republic of Pirates for about 11 years.

1807

The British Abolish the Slave Trade

The British abolish the slave trade resulting in a large number of free slaves in the Bahamas.

Bahamas Independence Day FAQs

Which country owns the Bahamas?

No country owns the Bahamas. It is an independent nation that was formerly a British territory.

What is the language used in the Bahamas?

English is primarily used.

Where did the people of the Bahamas come from?

The original inhabitants of the Bahamas were the indigenous Lucayan population. They come from Hispaniola and Cuba between 1100 A.D. to 1200 A.D.

How to Observe Bahamas Independence Day

Watch the parades

The Bahamas hosts parades and musical performances to mark the day. Try to watch the whole thing. You can see them on any online news channel.

Visit the nation

If you can directly visit the nation, then by all means do that. The Bahamas is full of pristine white sand beaches and turquoise waters. Enjoy your summer!

Create a historical timeline poster

The Bahamas has a very long and rich history. Create a poster illustrating the historical timeline of the nation. Mention how the nation turned from an unknown backwater to a rich natural paradise.

5 Facts About Bahamas That You Should Know

The ocean floor is visible

In the Bahamas, it is possible to see the ocean floor that can be 200 feet below the surface.

A nation of islands

There are 700 islands in the Bahamas and only 30 are inhabited.

The third-largest barrier reef

The Andros Barrier Reef in the Bahamas is the third-largest barrier reef.

It’s almost a flat nation

Mount Alvernia on Cat Island is the highest peak in the Bahamas and is only 207 feet.

The marching band is on the currency

The Nassau Police Marching Band is on the $1 note.

Why Bahamas Independence Day is Important

It celebrates the history

The Bahamas has a rich and vibrant history. Learn all about its journey to independence today.

It’s an appreciation of the culture

The day is the perfect opportunity to immerse yourself in the cultural practices of the country. Watch videos and read up online to learn all about the culture.

It encourages tourism

Who doesn’t want to visit the Bahamas? The more people discover about the country today, the more it will encourage them to visit.

Source

#Bahamas#10 July 1973#anniversary#travel#original photography#vacation#tourist attraction#landmark#cityscape#Atlantic Ocean#summer 2013#Straw Market#Rawson Square#Bahamian Parliament#Christ Church Cathedral#Paradise Island#architecture#Caribbean Sea#Bahamas Independence Day#Bahamian history

4 notes

·

View notes