#Monetarism

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Rent control works

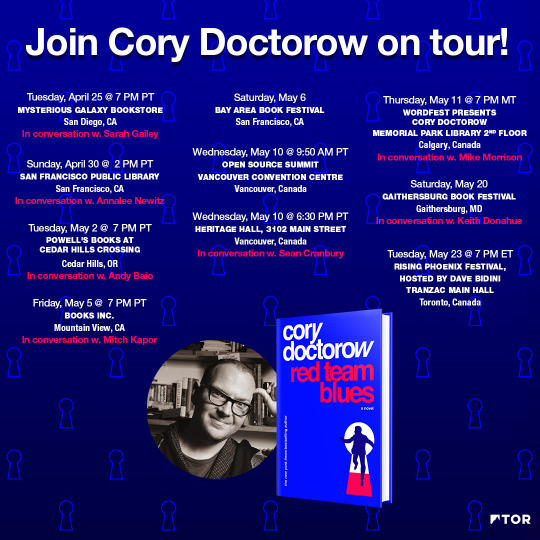

This Saturday (May 20), I’ll be at the GAITHERSBURG Book Festival with my novel Red Team Blues; then on May 22, I’m keynoting Public Knowledge’s Emerging Tech conference in DC.

On May 23, I’ll be in TORONTO for a book launch that’s part of WEPFest, a benefit for the West End Phoenix, onstage with Dave Bidini (The Rheostatics), Ron Diebert (Citizen Lab) and the whistleblower Dr Nancy Olivieri.

David Roth memorably described the job of neoliberal economists as finding “new ways to say ‘actually, your boss is right.’” Not just your boss: for decades, economists have formed a bulwark against seemingly obvious responses to the most painful parts of our daily lives, from wages to education to health to shelter:

https://popula.com/2023/04/30/yakkin-about-chatgpt-with-david-roth/

How can we solve the student debt crisis? Well, we could cancel student debt and regulate the price of education, either directly or through free state college.

How can we solve America’s heath-debt crisis? We could cancel health debt and create Medicare For All.

How can we solve America’s homelessness crisis? We could build houses and let homeless people live in them.

How can we solve America’s wage-stagnation crisis? We could raise the minimum wage and/or create a federal jobs guarantee.

How can we solve America’s workplace abuse crisis? We could allow workers to unionize.

How can we solve America’s price-gouging greedflation crisis? With price controls and/or windfall taxes.

How can we solve America’s inequality crisis? We could tax billionaires.

How can we solve America’s monopoly crisis? We could break up monopolies.

How can we solve America’s traffic crisis? We could build public transit.

How can we solve America’s carbon crisis? We can regulate carbon emissions.

These answers make sense to everyone except neoliberal economists and people in their thrall. Rather than doing the thing we want, neoliberal economists insist we must unleash “markets” to solve the problems, by “creating incentives.” That may sound like a recipe for a small state, but in practice, “creating incentives” often involves building huge bureaucracies to “keep the incentives aligned” (that is, to prevent private firms from ripping off public agencies).

This is how we get “solutions” that fail catastrophically, like:

Public Service Loan Forgiveness instead of debt cancellation and free college:

https://studentloansherpa.com/likely-ineligible/

The gig economy instead of unions and minimum wages:

https://www.newswise.com/articles/research-reveals-majority-of-gig-economy-workers-are-earning-below-minimum-wage

Interest rate hikes instead of price caps and windfall taxes:

https://www.npr.org/2023/05/03/1173371788/the-fed-raises-interest-rates-again-in-what-could-be-its-final-attack-on-inflati

Tax breaks for billionaire philanthropists instead of taxing billionaires:

https://memex.craphound.com/2018/11/10/winners-take-all-modern-philanthropy-means-that-giving-some-away-is-more-important-than-how-you-got-it/

Subsidizing Uber instead of building mass transit:

https://prospect.org/infrastructure/cities-turn-uber-instead-buses-trains/

Fraud-riddled carbon trading instead of emissions limits:

https://pluralistic.net/2022/05/27/voluntary-carbon-market/#trust-me

As infuriating as all of this “actually, your boss is right” nonsense is, the most immediate and continuously frustrating aspect of it is the housing crisis, which has engulfed cities all over the world, to the detriment of nearly everyone.

America led the way on screwing up housing. There were two major New Deal/post-war policies that created broad (but imperfect and racially biased) prosperity in America: housing subsidies and labor unions. Of the two, labor unions were the most broadly inclusive, most available across racial and gender lines, and most engaged with civil rights struggles and other progressive causes.

So America declared war on labor unions and told working people that their only path to intergenerational wealth was to buy a home, wait for it to “appreciate,” and sell it on for a profit. This is a disaster. Without unions to provide countervailing force, every part of American life has worsened, with stagnating wages lagging behind skyrocketing expenses for education, health, retirement, and long-term care. For nearly every homeowner, this means that their “most valuable asset” — the roof over their head — must be liquidated to cover debts. Meanwhile, their kids, burdened with six-figure student debt — will have little or nothing left from the sale of the family home with which to cover a downpayment in a hyperinflated market:

https://gen.medium.com/the-rents-too-damned-high-520f958d5ec5

Meanwhile, rent inflation is screaming ahead of other forms of inflation, burdening working people beyond any ability to pay. Giant Wall Street firms have bought up huge swathes of the country’s housing stock, transforming it into overpriced, undermaintained slums that you can be evicted from at the drop of a hat:

https://pluralistic.net/2022/02/08/wall-street-landlords/#the-new-slumlords

Transforming housing from a human right to an “asset” was always going to end in a failure to build new housing stock and regulate the rental market. It’s reaching a breaking point. “Superstar cities” like New York and San Francisco have long been priced out of the reach of working people, but now they’re becoming unattainable for double-income, childless, college-educated adults in their prime working years:

https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2023/05/15/upshot/migrations-college-super-cities.html

A city that you can’t live in is a failure. A system that can’t provide decent housing is a failure. The “your boss is right, actually” crowd won: we don’t build public housing, we don’t regulate rents, and it suuuuuuuuuuuuuuucks.

Maybe we could try doing things instead of “aligning incentives?”

Like, how about rent control.

God, you can already hear them squealing! “Price controls artificially distort well-functioning markets, resulting in a mismatch between supply and demand and the creation of the dreaded deadweight loss triangle!”

Rent control “causes widespread shortages, leaving would-be renters high and dry while screwing landlords (the road to hell, so says the orthodox economist, is paved with good intentions).”

That’s been the received wisdom for decades, fed to us by Chicago School economists who are so besotted with their own mathematical models that any mismatch between the models’ predictions and the real world is chalked up to errors in the real world, not the models. It’s pure economism: ��If economists wished to study the horse, they wouldn’t go and look at horses. They’d sit in their studies and say to themselves, ‘What would I do if I were a horse?’”

https://pluralistic.net/2022/10/27/economism/#what-would-i-do-if-i-were-a-horse

But, as Mark Paul writes for The American Prospect, rent control works:

https://prospect.org/infrastructure/housing/2023-05-16-economists-hate-rent-control/

Rent control doesn’t constrain housing supply:

https://dornsife.usc.edu/pere/rent-matters

At least some of the time, rent control expands housing supply:

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/j.1467-9906.2007.00334.x

The real risk of rent control is landlords exploiting badly written laws to kick out tenants and convert their units to condos — that’s not a problem with rent control, it’s a problem with eviction law:

https://web.stanford.edu/~diamondr/DMQ.pdf

Meanwhile, removing rent control doesn’t trigger the predicted increases in housing supply:

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0094119006000635

Rent control might create winners (tenants) and losers (landlords), but it certainly doesn’t make everyone worse off — as the neoliberal doctrine insists it must. Instead, tenants who benefit from rent control have extra money in their pockets to spend on groceries, debt service, vacations, and child-care.

Those happier, more prosperous people, in turn, increase the value of their landlords’ properties, by creating happy, prosperous neighborhoods. Rent control means that when people in a neighborhood increase its value, their landlords can’t kick them out and rent to richer people, capturing all the value the old tenants created.

What is life like under rent control? It’s great. You and your family get to stay put until you’re ready to move on, as do your neighbors. Your kids don’t have to change schools and find new friends. Old people aren’t torn away from communities who care for them:

https://ideas.repec.org/a/uwp/landec/v58y1982i1p109-117.html

In Massachusetts, tenants with rent control pay half the rent that their non-rent-controlled neighbors pay:

https://economics.mit.edu/sites/default/files/publications/housing%20market%202014.pdf

Rent control doesn’t just make tenants better off, it makes society better off. Rather than money flowing from a neighborhood to landlords, rent control allows the people in a community to invest it there: opening and patronizing businesses.

Anything that can’t go on forever will eventually stop. As the housing crisis worsens, states are finally bringing back rent control. New York has strengthened rent control for the first time in 40 years:

https://www.nytimes.com/2019/06/12/nyregion/rent-regulation-laws-new-york.html

California has a new statewide rent control law:

https://www.nytimes.com/2019/09/11/business/economy/california-rent-control.html

They’re battling against anti-rent-control state laws pushed by ALEC, the right-wing architects of model legislation banning action on climate change, broadband access, and abortion:

https://www.nmhc.org/research-insight/analysis-and-guidance/rent-control-laws-by-state/

But rent control has broad, democratic support. Strong majorities of likely voters support rent control:

https://www.bostonglobe.com/2023/03/07/metro/new-statewide-poll-shows-strong-support-rent-control/

And there’s a kind of rent control that has near unanimous support: the 30-year fixed mortgage. For the 67% of Americans who live in owner-occupied homes, the existence of the federally-backed (and thus federally subsidized) fixed mortgage means that your monthly shelter costs are fixed for life. What’s more, these costs go down the longer you pay them, as mortgage borrowers refinance when interest rates dip.

We have a two-tier system: if you own a home, then the longer you stay put, the cheaper your “rent” gets. If you rent a home, the longer you stay put, the more expensive your home gets over time.

America needs a shit-ton more housing — regular housing for working people. Mr Market doesn’t want to build it, no matter how many “incentives” we dangle. Maybe it’s time we just did stuff instead of building elaborate Rube Goldberg machines in the hopes of luring the market’s animal sentiments into doing it for us.

Catch me on tour with Red Team Blues in Toronto, DC, Gaithersburg, Oxford, Hay, Manchester, Nottingham, London, and Berlin!

If you’d like an essay-formatted version of this post to read or share, here’s a link to it on pluralistic.net, my surveillance-free, ad-free, tracker-free blog:

https://pluralistic.net/2023/05/16/mortgages-are-rent-control/#housing-is-a-human-right-not-an-asset

[Image ID: A beautifully laid dining room table in a luxury flat. Outside of the windows looms a rotting shanty town with storm-clouds overhead.]

Image: ozz13x (modified) https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Shanty_Town_Hong_Kong_China_March_2013.jpg

Matt Brown (modified) https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Dining_room_in_Centre_Point_penthouse.jpg

CC BY 2.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/deed.en

#pluralistic#urbanism#weaponized shelter#housing#the rent's too damned high#rent control#economism#neoliberalism#monetarism#mr market#landlord brain#speculation

118 notes

·

View notes

Note

What are your thoughts about Andrew Mellon and how much blame he has for the Great Depression?

Andrew Mellon was a bastard, and his policies hurt way more than they helped, but I don't hold with the monetarist explanation for the Great Depression. I think Keynes was right.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Theories of the Philosophy of Macroeconomics

The philosophy of macroeconomics deals with the study of large-scale economic phenomena, such as aggregate output, employment, inflation, and economic growth. It seeks to understand the principles, assumptions, and implications of overall economic activity and the interactions between different sectors of the economy. Some key theories in the philosophy of macroeconomics include:

Classical Economics: Classical economics emphasizes the long-run equilibrium of the economy, where prices and wages adjust to ensure full employment and resource utilization. It stresses the importance of free markets, minimal government intervention, and the self-regulating nature of the economy.

Keynesian Economics: Keynesian economics, developed by John Maynard Keynes, focuses on short-run fluctuations in economic activity and the role of aggregate demand in determining output and employment. It advocates for government intervention through fiscal policy (such as government spending and taxation) and monetary policy (such as interest rate adjustments) to stabilize the economy and address unemployment during recessions.

Monetarism: Monetarism, associated with economists like Milton Friedman, emphasizes the role of monetary policy in influencing aggregate demand and economic outcomes. It argues that changes in the money supply directly impact inflation and economic growth, advocating for stable and predictable growth in the money supply to maintain price stability and promote long-term economic growth.

New Classical Economics: New classical economics incorporates microeconomic foundations into macroeconomic models and emphasizes the rational expectations hypothesis. It posits that individuals form expectations about future economic variables based on all available information, leading to self-correcting market outcomes and limited effectiveness of government policies.

New Keynesian Economics: New Keynesian economics builds on Keynesian principles but incorporates microeconomic foundations and imperfect competition into macroeconomic models. It emphasizes the role of nominal rigidities, such as sticky prices and wages, in explaining short-run fluctuations in economic activity and advocates for countercyclical policies to stabilize the economy.

Real Business Cycle Theory: Real business cycle theory attributes fluctuations in economic activity to exogenous shocks to productivity and technology. It argues that changes in real factors, such as productivity shocks, drive business cycles, while monetary and fiscal policy have limited effects on real economic outcomes.

Post-Keynesian Economics: Post-Keynesian economics extends Keynesian principles by emphasizing the role of uncertainty, financial instability, and institutional factors in shaping economic behavior. It critiques mainstream macroeconomic models for their simplifying assumptions and advocates for a more heterodox approach to macroeconomic analysis.

Modern Monetary Theory (MMT): Modern Monetary Theory challenges traditional views on fiscal policy and government finance, arguing that countries with sovereign currencies can issue fiat money to finance government spending without facing solvency constraints. It emphasizes the role of fiscal policy in achieving full employment and price stability, advocating for policies that prioritize job creation and public investment.

These theories and approaches in the philosophy of macroeconomics provide frameworks for understanding the determinants of aggregate economic activity, the role of government policy, and the dynamics of economic fluctuations and growth.

#philosophy#epistemology#knowledge#learning#chatgpt#education#ethics#psychology#economics#economic theory#theory#Classical economics#Keynesian economics#Monetarism#New classical economics#New Keynesian economics#Real business cycle theory#Post-Keynesian economics#Modern monetary theory (MMT)#macroeconomics

1 note

·

View note

Text

youtube

Friedman's Scandalous Interview Excited Many

Milton Friedman, a well-known American economist and Nobel Prize winner, spoke about the emergence of an Internet currency back in 1999.

A currency that would allow global transactions without the participation of banks and provide complete anonymity will be created 10 years after the interview.

“I believe that the Internet will replace everything, reduce the role of government in society and the influence of official media. An important component of this process will be a reliable electronic currency with which people will be able to transfer money to each other maintaining complete confidentiality,” howright Milton Friedman was.

Friedman actively promoted the concept of monetarism arguing that monetary policy plays a key role in economic growth and inflation control. He also attracted attention for his research in consumer theory, macroeconomics, and economic history.

Lado Okhotnikov, “Bitcoin was created about ten years after the interview with Milton Friedman. I don't think it's a coincidence."

#MiltonFriedman#economist#NobelPrizeWinner#free_market#economictheory#monetarism#libertarianism#Crypto#News#Youtube

1 note

·

View note

Text

Get Financial Independence and Crush Your Debt Today!

Are you tired of living under the weight of your debts?

Do you find yourself struggling to make ends meet, despite your best efforts? At Debt Crusher Pro, we understand how difficult it can be to overcome financial difficulties. That’s why we’re here to help you get back on Get Financial Independence and Crush Your Debt Today!

Are you tired of living under the weight of your debts? Do you find yourself struggling to make ends meet, despite your best efforts? At Debt Crusher Pro, we understand how difficult it can be to overcome financial difficulties. That’s why we’re here to help you get back on track and achieve financial independence.

If you’re not sure how to resolve your debt, or if you’re looking for a way to pay less than what you owe, we’re here to help. Our expert team has over 15 years of experience negotiating debt settlement and securing small monthly payment plans for our clients. We can also help you improve your credit score and resolve any issues related to auto loans, mortgages, or business debt.

Don’t let your debt hold you back any longer. By working with Debt Crusher Pro, you can take control of your finances and achieve the financial freedom you deserve. Contact us today to schedule your free consultation and take the first step towards a brighter financial future.

#income inequality#anti capitalism#pluralistic#worker power#austerity#monetarism#jerome powell#the fed#federal reserve#finance#banking#economics#macroeconomics#interest rates#the american prospect#the great inflation myths#debt#graeber#michael hudson#indenture#medieval bloodletters#college debt#wealth inequality#Important#crowfunding#branco#student loans

1 note

·

View note

Text

“Money supply growth fell again in January, falling even further into negative territory after turning negative in November 2022 for the first time in twenty-eight years. January's drop continues a steep downward trend from the unprecedented highs experienced during much of the past two years.

Since April 2021, money supply growth has slowed quickly, and since November, we've been seeing the money supply contract for the first time since the 1990s. The last time the year-over-year (YOY) change in the money supply slipped into negative territory was in November 1994. At that time, negative growth continued for fifteen months, finally turning positive again in January 1996.

During January 2023, YOY growth in the money supply was at -5.04 percent. That's down from December's rate of -02.19 percent and down from January 2022's rate of 6.82 percent. With negative growth now dipping below -5 percent, money-supply contraction is approaching the biggest decline we've seen in the past thirty-five years. Only during brief periods of 1989 and 1995 did the money supply fall as much. At no point for at least sixty years has the money supply fallen by more than 5.6 percent in any month.”

“U.S. money supply is falling at its fastest rate since the 1930s, a red flag for the economy and financial markets.

Money supply has now been shrinking year-on-year since December, an unprecedented development in modern times that should make investors sit up and take notice - growth, asset prices and inflation could all weaken.

It is largely a consequence of the reversal of the liquidity generated by massive post-pandemic fiscal and monetary stimulus, the Federal Reserve shrinking its balance sheet via quantitative tightening, falling bank deposits, and weak demand for and provision of credit.

(…)

Fed data on Tuesday showed that M2 money supply, a benchmark measure of how much cash and cash-like assets is circulating in the U.S. economy, fell a non-seasonally adjusted 2.2% to $21.099 trillion in February from the same period a year earlier.”

#money#monetarism#fed#federal reserve#quantitative easing#quantitative tightening#america#banks#svb failure#rothbard#murray rothbard#mises

1 note

·

View note

Text

I have no idea why images from wikis now only download as webp but it sucks & I hope whoever made the decision to implement it engage in a long period of soul searching that leads them to reevaluate their life choices and moral code. Anyways bypass it by adding &format=original to the end of the image url

#It's not even just bsd as far as I could see it's the same with all wikis. Wtf. Wtf.#Anyways this is your n reason to avoid using Fandom which is an industry that keeps monetarizing volunteers work#and support the entirely fanmade wikis instead#random rambles

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Analiza Pieței - 21 Octombrie 2024 (FINANȚE)

Azi voi trece în revistă principalii indici, dobânzile de referință și calendarul economic pentru cei care vor să fie la curent cu ultimele știri și tendințe de pe piața de capital. Acest video este realizat pe 21 Octombrie 2024 înaintea deschiderii pieței de capital din America. Exemplele oferite nu sunt recomandări de investiții.

youtube

View On WordPress

#Acțiuni#Analiza 21.10.2024#analiza pietei bursiere#analiza pietei de capital#BET#BTC#bullish or bearish#CAC40#calendar economic#calendarul raportarilor financiare SUA#Catalin Daniel Iamandi#CN50usd#Cătălin D. Iamandi#DAX#dividende#DJI#dobanzi de referinta#educatie financiara#fear-greed#Financial Education#Financial Success#finante personale#FMI#Fondul Monetar International#GOLD#investiții#Investing#investitor#NATGAS#NI225

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

I wanna sponsor you too!! *Hugs aggressively*

Aw, thank you!! *hugs back aggressively*

#sometimes I think about turning on the monetarism of this blog#like I deserve to be paid for the bullshit I put up with on this blog#punk gets mail

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

To all Palestine supporters 🙏

We still need less than €383 to reach our short term goal of €18,000‼️

Your donations are important for our survival

Please help me reach our goal as soon as possible 🙏

We appreciate your help ❤️🙏

.

0 notes

Text

Sir John Nott

Defence secretary in Margaret Thatcher’s cabinet during the Falklands war

The reputation of John Nott, who has died aged 92, will for ever be linked with the Falklands war of 1982. Nott was the defence secretary in Margaret Thatcher’s first administration and was extremely fortunate politically to survive one of Britain’s gravest postwar crises – yet it effectively ended his ministerial career.

Although the British taskforce retook the islands from Argentina after just 10 weeks’ occupation, Nott could not escape responsibility for his part in the government’s earlier decisions to reduce the islands’ protection, which had convinced the generals in Buenos Aires that they could launch their attack with impunity. Nor did he ever live down his ill-disguised pessimism about the taskforce’s chances of success. From being one of the Tories’ rising rightwing hopes and a prospective future chancellor, he left parliament for good a year after the war, with a knighthood; he was never awarded a peerage.

Nott was a somewhat forbidding figure with the air of a disapproving bank manager, a waspish tongue and a self-righteous and partisan manner – none of them attributes likely to inspire either the nation or its armed forces in time of national emergency. He had in fact calculated on an intermittent political career, sandwiching stints as an MP and minister between spells making money in business. Instead, his political career was over by the time he was 51 and he retired to the City, becoming chairman and chief executive of the merchant bank Lazard Brothers.

In that sense, his most memorable television appearance, a live interview with Robin Day in 1982 when he flounced out in an undignified huff on being referred to as a “here today, gone tomorrow” politician, was apposite. Indeed, 20 years later he entitled his autobiography Here Today, Gone Tomorrow (2002).

Born in Bromley. south-east London, John was the son of Phyllis (nee Francis) and Richard Nott, a rice broker from a West Country military family. On leaving Bradfield college, Berkshire, he served as a subaltern with the Gurkha Rifles during the Malayan emergency and was for a period the ADC to the commander-in-chief of British far east forces, before going to Trinity College, Cambridge, to study law and economics. He became president of the Cambridge Union and, on graduation, was called to the Bar, although he never practised as a lawyer. Instead he joined SG Warburg, the merchant bank, and remained there for eight years.

At Cambridge he met Miloska Sekol, a Slovenian refugee, who was studying English. The story went that Nott told her at their first meeting, in 1959, that he intended to marry her – a remarkable gesture from such an apparently staid and undashing figure, and an approach that appears to have taken her by surprise. She wrote in her diary that night: “What a cheek, how preposterous!” They married the same year.

Nott entered the Commons at the 1966 general election as MP for St Ives in Cornwall. He spent the rest of his life living in the county and promoting what he saw as its interests, calling for improved rail links west of Plymouth, and opposing incursions by French fishermen and the Anglo-French Concorde project. But it was as a bone-dry, rightwing economist, suspicious of the EU and pro-Commonwealth, that he made his mark: serving as an opposition economics spokesman and, after the Conservatives returned to power in 1970, becoming a junior Treasury minister, focusing on matters such as tax reform.

After Edward Heath’s 1974 defeat, however, he refused to become an opposition spokesman. He returned to the City as a consultant and to his Cornish estate, where he grew flowers commercially. Thatcher’s leadership was more to his liking and the rising Tory tide in favour of monetarism more ideologically congenial. “The party has almost found its soul again,” he told readers of the Daily Telegraph. He returned to the opposition frontbench, harrying the chancellor Denis Healey with a sharp wit.

Thatcher saw him as a kindred spirit, identified him as a rising star and, when the Tories returned to power in 1979, rewarded him by making him trade secretary. He naturally enthusiastically supported cuts in public spending, but also supported the expansion of London’s airports: a fourth terminal at Heathrow, a second runway at Gatwick and expansion at Stansted formed his most tangible legacy.

Then, in 1981, as the prime minister turned against the wets, Nott was moved to defence, to shake up the department and cut without squeamishness. He quickly decided that the priority was defence against the Soviet Union, not the promotion of worldwide, post-imperial pretensions, which was unfortunate in the light of what was to happen the following year in the South Atlantic. “Our first priority had to be credible deterrence from Soviet aggression on mainland Europe, decidedly not equipping ourselves for another Suez or post-colonial war,” he wrote later, and he proceeded to strengthen the army at the expense of the Royal Navy, targeting the service’s last aircraft carrier for closure.

Among the lesser cuts was a plan to scrap the gunboat Endurance, which guarded the Falklands. That, and the ruminations of his fellow rightwinger and Thatcherite rising star Nicholas Ridley that the islands were dispensable, sent a clear message to the junta. Had the Argentinian generals been a little more patient, Nott might single-handedly have made the taskforce that was subsequently launched impossible. As it was, he lost the navy minister to resignation and earned the lasting hostility of the first sea lord, Sir Henry Leach, who later wrote that he despised Nott’s performance.

Accordingly, when some Argentinian scrap metal merchants landed on South Georgia Island, sparking conflict, the government was taken by surprise. Nott later confessed that he had to look up where the Falkland Islands were on the globe in his office and he was immediately pessimistic of the chances of recovering them: it was Leach who seized the initiative to prove the navy’s worth and urged the prime minister, against her defence secretary’s advice and instincts, to mobilise an immediate taskforce to retake the islands. Nott’s insistence to MPs during that weekend’s emergency Commons debate that “no other country could have reacted so fast and the preparations have been in progress for several weeks. We were not unprepared” was therefore at best being economical with the truth.

When, 10 weeks later, the islands were retaken, albeit at considerable human cost, Nott received little of the credit and none of the glory within the party – that all went to Thatcher – or in the country, which was more inclined to credit the bravery and resilience of the troops than the triumphalism of politicians. His pretensions to succeed Howe as chancellor, or indeed any ambitions he might have harboured one day to follow Thatcher as prime minister, a possibility that had been occasionally mooted by some of the party’s zealouts, were at an end.

Before Thatcher’s post-Falklands general election landslide victory the following year, Nott chose to stand down as an MP. He could see the way the wind was blowing: the naval cuts were reversed. “The admirals have got their fucking gin palaces back,” he told friends. There was a certain degree of bitterness, too, even towards the prime minister herself. “The full cabinet was never more than a rubber stamp,” he said in a later BBC interview, accusing Thatcher of fostering a cult of personality: “Like all ambitious women, she thinks all men are feeble and that gentlemen are even more feeble.”

Back in the City, he accumulated directorships and money: chairman of Lazard, director of Royal Insurance, chairman of the food company Hillsdown Holdings, and of the clothing retailer Etam, and an adviser to the law firm Freshfields. He only occasionally intervened in politics: vociferously opposing the euro from an early stage and calling for early intervention in the 1990s Balkans crisis.

And he continued his battle with the pretensions of the navy: “Today’s defence policy has not been assisted by the Falklands experience,” he wrote in the Daily Telegraph in 2012. “It is still designed to prepare the Royal Navy for another Falklands … when technology, particularly air power, has moved into a new era … The Royal Navy’s future lies in a substantial number of well-armed modern frigates and destroyers, not two carriers, which are far too expensive to build, service and protect.”

He is survived by his wife and their children, Julian, William and Sasha.

🔔 John William Frederic Nott, politician, born 1 February 1932; died 6 November 2024

Daily inspiration. Discover more photos at Just for Books…?

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

G.3.6 Would mutual banking simply cause inflation?

One of the arguments against Individualist and mutualist anarchism, and mutual banking in general, is that it would just produce accelerating inflation. The argument is that by providing credit without interest, more and more money would be pumped into the economy. This would lead to more and more money chasing a given set of goods, so leading to price rises and inflation.

Rothbard, for example, dismissed individualist anarchist ideas on mutual banking as being “totally fallacious monetary views.” He based his critique on “Austrian” economics and its notion of “time preference” (see section C.2.7 for a critique of this position). Mutual banking would artificially lower the interest rate by generating credit, Rothbard argued, with the new money only benefiting those who initially get it. This process “exploits” those further down the line in the form accelerating inflation. As more and more money was be pumped into the economy, it would lead to more and more money chasing a given set of goods, so leading to price rises and inflation. To prove this, Rothbard repeated Hume’s argument that “if everybody magically woke up one morning with the quantity of money in his possession doubled” then prices would simply doubled. [“The Spooner-Tucker Doctrine: An Economist’s View”, Journal of Libertarian Studies, vol. 20, no. 1, p. 14 and p. 10]

However, Rothbard is assuming that the amount of goods and services are fixed. This is just wrong and shows a real lack of understanding of how money works in a real economy. This is shown by the lack of agency in his example, the money just “appears” by magic (perhaps by means of a laissez-fairy?). Milton Friedman made the same mistake, although he used the more up to date example of government helicopters dropping bank notes. As post-Keynesian economist Nicholas Kaldor pointed out with regards to Friedman’s position, the “transmission mechanism from money to income remained a ‘black box’ — he could not explain it, and he did not attempt to explain it either. When it came to the question of how the authorities increase the supply of bank notes in circulation he answered that they are scattered over populated areas by means of a helicopter — though he did not go into the ultimate consequences of such an aerial Santa Claus.” [The Scourge of Monetarism, p. 28]

Friedman’s and Rothbard’s analysis betrays a lack of understanding of economics and money. This is unsurprising as it comes to us via neo-classical economics. In neo-classical economics inflation is always a monetary phenomena — too much money chasing too few goods. Milton Friedman’s Monetarism was the logical conclusion of this perspective and although “Austrian” economics is extremely critical of Monetarism it does, however, share many of the same assumptions and fallacies (as Hayek’s one-time follower Nicholas Kaldor noted, key parts of Friedman’s doctrine are “closely reminiscent of the Austrian school of the twenties and the early thirties” although it “misses some of the subtleties of the Hayekian transmission mechanism and of the money-induced distortions in the ‘structure of production.’” [The Essential Kaldor, pp. 476–7]). We can reject this argument on numerous points.

Firstly, the claim that inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomena has been empirically refuted — often using Friedman’s own data and attempts to apply his dogma in real life. As we noted in section C.8.3, the growth of the money supply and inflation have no fixed relationship, with money supply increasing while inflation falling. As such, “the claim that inflation is always and everywhere caused by increases in the money supply, and that the rate of inflation bears a stable, predictable relationship to increases in the money supply is ridiculous.” [Paul Ormerod, The Death of Economics, p. 96] This means that the assumption that increasing the money supply by generating credit will always simply result in inflation cannot be supported by the empirical evidence we have. As Kaldor stressed, the “the ‘first-round effects’ of the helicopter operation could be anything, depending on where the scatter occurred … there is no reason to suppose that the ultimate effect on the amount of money in circulation or on incomes would bear any close relation to the initial injections.” [The Scourge of Monetarism, p. 29]

Secondly, even if we ignore the empirical record (as “Austrian” economics tends to do when faced with inconvenient facts) the “logical” argument used to explain the theory that increases in money will increase prices is flawed. Defenders of this argument usually present mental exercises to prove their case (as in Hume and Friedman). Needless to say, such an argument is spurious in the extreme simply because money does not enter the economy in this fashion. It is generated to meet specific demands for money and is so, generally, used productively. In other words, money creation is a function of the demand for credit, which is a function of the needs of the economy (i.e. it is endogenous) and not determined by the central bank injecting it into the system (i.e. it is not exogenous). And this indicates why the argument that mutual banking would produce inflation is flawed. It does not take into account the fact that money will be used to generate new goods and services.

As leading Post-Keynesian economist Paul Davidson argued, the notion that “inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon” (to use Friedman’s expression) is “ultimately based on the old homily that inflation is merely ‘too many dollars chasing too few goods.’” Davidson notes that ”[t]his ‘too many dollars cliché is usually illustrated by employing a two-island parable. Imagine a hypothetical island where the only available goods are 10 apples and the money supply consists of, say, 10 $1 bills. If all the dollars are used to purchase the apples, the price per apple will be $1. For comparison, assume that on a second island there are 20 $1 bills and only 10 apples. All other things being equal, the price will be $2 per apple. Ergo, inflation occurs whenever the money supply is excessive relative to the available goods.” The similarities with Rothbard’s argument are clear. So are its flaws as “no explanation is given as to why the money supply was greater on the second island. Nor is it admitted that, if the increase in the money supply is associated with entrepreneurs borrowing ‘real bills’ from banks to finance an increase in payrolls necessary to harvest, say, 30 additional apples so that the $20 chases 40 apples, then the price will be only $0.50 per apple. If a case of ‘real bills’ finance occurs, then an increase in the money supply is not associated with higher prices but with greater output.” [Controversies in Post Keynesian Economics, p. 100] Davidson is unknowingly echoing Tucker (“It is the especial claim of free banking that it will increase production … If free banking were only a picayanish attempt to distribute more equitably the small amount of wealth now produced, I would not waste a moment’s energy on it.” [Liberty, no. 193, p. 3]).

This, in reply to the claims of neo-classical economics, indicates why mutual banking would not increase inflation. Like the neo-classical position, Rothbard’s viewpoint is static in nature and does not understand how a real economy works. Needless to say, he (like Friedman) did not discuss how the new money gets into circulation. Perhaps, like Hume, it was a case of the money fairy (laissez-fairy?) placing the money into people’s wallets. Maybe it was a case, like Friedman, of government (black?) helicopters dropping it from the skies. Rothbard did not expound on the mechanism by which money would be created or placed into circulation, rather it just appears one day out of the blue and starts chasing a given amount of goods. However, the individualist anarchists and mutualists did not think in such bizarre (typically, economist) ways. Rather than think that mutual banks would hand out cash willy-nilly to passing strangers, they realistically considered the role of the banks to be one of evaluating useful investment opportunities (i.e., ones which would be likely to succeed). As such, the role of credit would be to increase the number of goods and services in circulation along with money, so ensuring that inflation is not generated (assuming that it is caused by the money supply, of course). As one Individualist Anarchist put it, ”[i]n the absence of such restrictions [on money and credit], imagine the rapid growth of wealth, and the equity in its distribution, that would result.” [John Beverley Robinson, The Individualist Anarchists, p. 144] Thus Tucker:

“A is a farmer owning a farm. He mortgages his farm to a bank for $1,000, giving the bank a mortgage note for that sum and receiving in exchange the bank’s notes for the same sum, which are secured by the mortgage. With the bank-notes A buys farming tools of B. The next day B uses the notes to buy of C the materials used in the manufacture of tools. The day after, C in turn pays them to D in exchange for something he needs. At the end of a year, after a constant succession of exchanges, the notes are in the hands of Z, a dealer in farm produce. He pays them to A, who gives in return $1,000 worth of farm products which he has raised during the year. Then A carries the notes to the bank, receives in exchange for them his mortgage note, and the bank cancels the mortgage. Now, in this whole circle of transactions, has there been any lending of capital? If so, who was the lender? If not, who is entitled to interest?” [Instead of a Book, p. 198]

Obviously, in a real economy, as Rothbard admits “inflation of the money supply takes place a step at a time and that the first beneficiaries, the people who get the new money first, gain at the expense of the people unfortunate enough to come last in line.” This process is “plunder and exploitation” as the “prices of things they [those last in line] have to buy shooting up before the new injection [of money] filters down to them.” [Op. Cit., p. 11] Yet this expansion of the initial example, again, assumes that there is no increase in goods and services in the economy, that the “first beneficiaries” do nothing with the money bar simply buying more of the existing goods and services. It further assumes that this existing supply of goods and services is unchangeable, that firms do not have inventories of goods and sufficient slack to meet unexpected increases in demand. In reality, of course, a mutual bank would be funding productive investments and any firm will respond to increasing demand by increasing production as their inventories start to decline. In effect, Rothbard’s analysis is just as static and unrealistic as the notion of money suddenly appearing overnight in people’s wallets. Perhaps unsurprisingly Rothbard compared the credit generation of banks to the act of counterfeiters so showing his utter lack of awareness of how banks work in a credit-money (i.e., real) economy.

The “Austrian” theory of the business cycle is rooted in the notion that banks artificially lower the rate of interest by providing more credit than their savings and specie reverses warrant. Even in terms of pure logic, such an analysis is flawed as it cannot reasonably be asserted that all “malinvestment” is caused by credit expansion as capitalists and investors make unwise decisions all the time, irrespective of the supply of credit. Thus it is simply false to assert, as Rothbard did, that the “process of inflation, as carried out in the real [sic!] world” is based on “new money” entered the market by means of “the loan market” but “this fall is strictly temporary, and the market soon restores the rate to its proper level.” A crash, according to Rothbard, is the process of restoring the rate of interest to its “proper” level yet a crash can occur even if the interest rate is at that rate, assuming that the banks can discover this equilibrium rate and have an incentive to do so (as we discussed in section C.8 both are unlikely). Ultimately, credit expansion fails under capitalism because it runs into the contradictions within the capitalist economy, the need for capitalists, financiers and landlords to make profits via exploiting labour. As interest rates increase, capitalists have to service their rising debts putting pressure on their profit margins and so raising the number of bankruptcies. In an economy without non-labour income, the individualist anarchists argued, this process is undercut if not eliminated.

So expanding this from the world of fictional government helicopters and money fairies, we can see why Rothbard is wrong. Mutual banks operate on the basis of providing loans to people to set up or expand business, either as individuals or as co-operatives. When they provide a loan, in other words, they increase the amount of goods and services in the economy. Similarly, they do not simply increase the money supply to reduce interest rates. Rather, they reduce interest rates to increase the demand for money in order to increase the productive activity in an economy. By producing new goods and services, inflation is kept at bay. Would increased demand for goods by the new firms create inflation? Only if every firm was operating at maximum output, which would be a highly unlikely occurrence in reality (unlike in economic textbooks).

So what, then does case inflation? Inflation, rather than being the result of monetary factors, is, in fact, a result of profit levels and the dynamic of the class struggle. In this most anarchists agree with post-Keynesian economics which views inflation as “a symptom of an on-going struggle over income distribution by the exertion of market power.” [Paul Davidson, Op. Cit., p. 102] As workers’ market power increases via fuller employment, their organisation, militancy and solidarity increases so eroding profits as workers keep more of the value they produce. Capitalists try and maintain their profits by rising prices, thus generating inflation (i.e. general price rises). Rather than accept the judgement of market forces in the form of lower profits, capitalists use their control over industry and market power of their firms to maintain their profit levels at the expense of the consumer (i.e., the workers and their families).

In this sense, mutual banks could contribute to inflation — by reducing unemployment by providing the credit needed for workers to start their own businesses and co-operatives, workers’ power would increase and so reduce the power of managers to extract more work for a given wage and give workers a better economic environment to ask for better wages and conditions. This was, it should be stressed, a key reason why the individualist anarchists supported mutual banking:

“people who are now deterred from going into business by the ruinously high rates which they must pay for capital with which to start and carry on business will find their difficulties removed … This facility of acquiring capital will give an unheard of impetus to business, and consequently create an unprecedented demand for labour — a demand which will always be in excess of the supply, directly to the contrary of the present condition of the labour market … Labour will then be in a position to dictate its wages.” [Tucker, The Individualist Anarchists, pp. 84–5]

And, it must also be stressed, this was a key reason why the capitalist class turned against Keynesian full employment policies in the 1970s (see section C.8.3). Lower interest rates and demand management by the state lead precisely to the outcome predicted by the likes of Tucker, namely an increase in working class power in the labour market as a result of a lowering of unemployment to unprecedented levels. This, however, lead to rising prices as capitalists tried to maintain their profits by passing on wage increases rather than take the cut in profits indicated by economic forces. This could also occur if mutual banking took off and, in this sense, mutual banking could produce inflation. However, such an argument against the scheme requires the neo-classical and “Austrian” economist to acknowledge that capitalism cannot produce full employment and that the labour market must always be skewed in favour of the capitalist to keep it working, to maintain the inequality of bargaining power between worker and capitalist. In other words, that capitalism needs unemployment to exist and so cannot produce an efficient and humane allocation of resources.

By supplying working people with money which is used to create productive co-operatives and demand for their products, mutual banks increase the amount of goods and services in circulation as it increases the money supply. Combined with the elimination of profit, rent and interest, inflationary pressures are effectively undercut (it makes much more sense to talk of a interest/rent/profits-prices spiral rather than a wages-prices spiral when discussing inflation). Only in the context of the ridiculous examples presented by neo-classical and “Austrian” economics does increasing the money supply result in rising inflation. Indeed, the “sound economic” view, in which if the various money-substitutes are in a fixed and constant proportion to “real money” (i.e. gold or silver) then inflation would not exist, ignores the history of money and the nature of the banking system. It overlooks the fact that the emergence of bank notes, fractional reserve banking and credit was a spontaneous process, not planned or imposed by the state, but rather came from the profit needs of capitalist banks which, in turn, reflected the real needs of the economy (“The truth is that, as the exchanges of the world increased, and the time came when there was not enough gold and silver to effect these exchanges, so … people had to resort to paper promises.” [John Beverley Robinson, Op. Cit., p. 139]). What was imposed by the state, however, was the imposition of legal tender, the use of specie and a money monopoly (“attempt after attempt has been made to introduce credit money outside of government and national bank channels, and the promptness of the suppression has always been proportional to the success of the attempt.” [Tucker, Liberty, no. 193, p. 3]).

Given that the money supply is endogenous in nature, any attempt to control the money supply will fail. Rather than control the money supply, which would be impossible, the state would have to use interest rates. To reduce the demand for money, interest rates would be raised higher and higher, causing a deep recession as business cannot maintain their debt payments and go bankrupt. This would cause unemployment to rise, weakening workers’ bargaining power and skewing the economy back towards the bosses and profits — so making working people pay for capitalism’s crisis. Which, essentially, is what the Thatcher and Reagan governments did in the early 1980s. Finding it impossible to control the money supply, they raised interest rates to dampen down the demand for credit, which provoked a deep recession. Faced with massive unemployment, workers’ market power decreased and their bosses increased, causing a shift in power and income towards capital.

So, obviously, in a capitalist economy the increasing of credit is a source of instability. While not causing the business cycle, it does increase its magnitude. As the boom gathers strength, banks want to make money and increase credit by lowering interest rates below what they should be to match savings. Capitalists rush to invest, so soaking up some of the unemployment which always marks capitalism. The lack of unemployment as a disciplinary tool is why the boom turns to bust, not the increased investment. Given that in a mutualist system, profits, interest and rent do not exist then erosion of profits which marks the top of a boom would not be applicable. If prices drop, then labour income drops. Thus a mutualist society need not fear inflation. As Kaldor argued with regard to the current system, “under a ‘credit-money’ system … unwanted or excess amounts of money could never come into existence; it is the increase in the value of transactions … which calls forth an increase in the ‘money supply’ (whether in the form of bank balances or notes in circulation) as a result of the net increase in the value of working capital at the various stages of production and distribution.” [Op. Cit., p. 46] The gold standard cannot do what a well-run credit-currency can do, namely tailor the money supply to the economy’s demand for money. The problem in the nineteenth century was that a capitalist credit-money economy was built upon a commodity-money base, with predictably bad results.

Would this be any different under Rothbard’s system? Probably not. For Rothbard, each bank would have 100% reserve of gold with a law passed that defined fractional reserve banking as fraud. How would this affect mutual banks? Rothbard argued that attempts to create mutual banks or other non-gold based banking systems would be allowed under his system. Yet, how does this fit into his repeated call for a 100% gold standard for banks? Why would a mutual bank be excluded from a law on banking? Is there a difference between a mutual bank issuing credit on the basis of a secured loan rather than gold and a normal bank doing so? Needless to say, Rothbard never did address the fact that the customers of the banks know that they practised fractional reserve banking and still did business with them. Nor did he wonder why no enterprising banker exploited a market niche by advertising a 100% reserve policy. He simply assumed that the general public subscribed to his gold-bug prejudices and so would not frequent mutual banks. As for other banks, the full might of the law would be used to stop them practising the same policies and freedoms he allowed for mutual ones. So rather than give people the freedom to choose whether to save with a fractional reserve bank or not, Rothbard simply outlawed that option. Would a regime inspired by Rothbard’s goldbug dogmas really allow mutual banks to operate when it refuses other banks the freedom to issue credit and money on the same basis? It seems illogical for that to be the case and so would such a regime not, in fact, simply be a new form of the money monopoly Tucker and his colleagues spent so much time combating? One thing is sure, though, even a 100% gold standard will not stop credit expansion as firms and banks would find ways around the law and it is doubtful that private defence firms would be in a position to enforce it.

Once we understand the absurd examples used to refute mutual banking plus the real reasons for inflation (i.e., “a symptom of a struggle over the distribution of income.” [Davidson, Op. Cit., p. 89]) and how credit-money actually works, it becomes clear that the case against mutual banking is far from clear. Somewhat ironically, the post-Keynesian school of economics provides a firm understanding of how a real credit system works compared to Rothbard’s logical deductions from imaginary events based on propositions which are, at root, identical with Walrasian general equilibrium theory (an analysis “Austrians” tend to dismiss). It may be ironic, but not unsurprising as Keynes praised Proudhon’s follower Silvio Gesell in The General Theory (also see Dudley Dillard’s essay “Keynes and Proudhon” [The Journal of Economic History, vol. 2, No. 1, pp. 63–76]). Libertarian Marxist Paul Mattick noted Keynes debt to Proudhon, and although Keynes did not subscribe to Proudhon’s desire to use free credit to fund “independent producers and workers’ syndicates” as a means create an economic system “without exploitation” he did share the Frenchman’s “attack upon the payment of interest” and wish to see the end of the rentier. [Marx and Keynes, p. 5 and p. 6]

Undoubtedly, given the “Austrian” hatred of Keynes and his economics (inspired, in part, by the defeat inflicted on Hayek’s business cycle theory in the 1930s by the Keynesians) this will simply confirm their opinion that the Individualist Anarchists did not have a sound economic analysis! As Rothbard noted, the individualist anarchist position was “simply pushing to its logical conclusion a fallacy adopted widely by preclassical and by current Keynesian writers.” [Op. Cit., p. 10] However, Keynes was trying to analyse the economy as it is rather than deducing logically desired conclusions from the appropriate assumptions needed to confirm the prejudices of the assumer (like Rothbard). In this, he did share the same method if not exactly the same conclusions as the Individualist Anarchists and Mutualists.

Needless to say, social anarchists do not agree that mutual banking can reform capitalism away. As we discuss in section G.4, this is due to many factors, including the nature barriers to competition capital accumulation creates. However, this critique is based on the real economy and does not reflect Rothbard’s abstract theorising based on pre-scientific methodology. While other anarchists may reject certain aspects of Tucker’s ideas on money, we are well aware, as one commentator noted, that his “position regarding the State and money monopoly derived from his Socialist convictions” where socialism “referred to an intent to fundamentally reorganise the societal systems so as to return the full product of labour to the labourers.” [Don Werkheiser, “Benjamin R. Tucker: Champion of Free Money”, pp. 212–221, Benjamin R. Tucker and the Champions of Liberty, Coughlin, Hamilton and Sullivan (eds.), p. 212]

#faq#anarchy faq#revolution#anarchism#daily posts#communism#anti capitalist#anti capitalism#late stage capitalism#organization#grassroots#grass roots#anarchists#libraries#leftism#social issues#economy#economics#climate change#climate crisis#climate#ecology#anarchy works#environmentalism#environment#solarpunk#anti colonialism#mutual aid#cops#police

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

In their eyes, wealth can’t just be a by-product of luck, can it? It must, one way or another, be deserved.

Among the great deformations of the four neoliberal decades through which we have lived are not just the policy catastrophes – monetarism, financial deregulation, austerity, Brexit, the Truss budget – but also the way that wealth generation and entrepreneurship, so crucial to the capitalist economy, have been ideologically framed. Instead of being recognised as a profoundly social process – in which great universities, the financial ecosystem and the runway provided by large and sophisticated markets support entrepreneurship – enterprise, and the wealth it produces, has been characterised as wholly attributable to individual derring-do in which luck plays little part. Hence the obsession with shrinking the state to reduce “burdensome” tax. …

But decades of being congratulated and indulged for the relentless pursuit of their own self-interest has turned the heads of too many of our successful rich. They really believe that they are different: that they owe little to the society from which they have sprung and in which they trade, that taxes are for little people. We are lucky to have them, and, if anything, owe them a favour. There is a long list of challenges confronting the new Labour government but one of the most overlooked is the need to start challenging this narrative.

3 notes

·

View notes

Note

Your last post reminded me that, years ago, I asked you about monetarism in Argentina because we had a Milton Friedman fanboy politician becoming more popular. Said fanboy ended up becoming president a few months ago, so we're going for another run I guess.

I feel very frightened for the people of Argentina, because the fanboy is turning out to be an anti-democratic maniac who is going to do a lot of economic damage as well.

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ai peticit golurile și-ai tras de tine, ai stors sevă să umezești măcar din când în când propriile-ți buze, însă lăcomia te-a măcinat mereu pe dinăuntru. Când nu era nimeni, îți ziceai că te descurci și așa, că n-ai nevoie, deși te-afundai în frig și brumă.

Îmi lipsește sălbăticia, curajul de-a sfida, de-a mă manifesta. Anxietatea și efectele virtualului mi-au proiectat mental sute de ochi care să cântărească fiecare vorbă, fiecare gest. Ne băgăm de bunăvoie în cuști și nu ne deranjează. Atât timp cât lumea aprobă, orice zgardă e simpatică. Slăbiți emoțional, apatici, judecăm lumea-n valori monetare. Când s-o termina, oare, presiunea asta psihică, oboseala asta invazivă; când s-o naște o nouă speranță, când or avea iarăși timpurile gust.

Mi-e teamă de clipa-n care nimic nu mă va mai revolta. Până și scrisul a devenit un soi de efort, nu mai am răbdare să răscolesc în mine și să reciclez trăiri.

Ai fi vrut să trăiești un pic mai altfel. Poate mai nesăbuită, fără să iei totul atât de adânc, dar să-ți plesnească plămânii de viață și plăcere, să-ți tresalte inima și să trăiești mereu și mereu ca și cum nimic nu s-ar putea epuiza. N-am cu cine.

Strâng din dinți și tac.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Just Me Against the Sky | Self Para

Date: October 2023 Featuring: Lightning, Dusty Warnings: Lightning McQueen's midlife crisis, bad parenting

Lightning takes a small step. And then another

Eventually, Lightning did call Dusty back. It wasn’t as glamorous or triumphant as it would have been in a sports movie. Lightning didn’t slam the phone down and announce “I quit!” as a Bruce Springsteen song hit its crescendo in the background and the sun rose over the trees. He just told Dusty that maybe he was right— maybe it was time to take a temporary step back from the circuit, to focus on his personal life.

Dusty said he understood. He sounded, maybe, a little annoyed that it had taken Lightning so long to get back to him— but the fact that he hadn’t dogged Lightning for a callback over the past few weeks signaled to the athlete that this had never been that serious for Dusty. At least, it wasn’t anymore.

When he got off the call, Lightning once again expected everything to be very cinematic. He expected the headlines to roll in: MCQUEEN QUITS! “TEMPORARY STEP BACK” = THE KISS OF DEATH? WHAT HAPPENED TO LIGHTNING MCQUEEN’S CAREER: A RETROSPECTIVE. But instead it was just Lightning, and his blank-screened phone, and his empty apartment.

And now that nobody had reacted, Lightning realized he didn’t have anyone to tell if he wanted to. Mack, Harv, the rest of the team— they’d have too many questions. What did it mean for their jobs, what did it mean for his career, did this mean he was really giving up? And Lightning didn’t know the answers yet. He’d answer their questions when this came up at the team meeting.

He could tell Agustin, but he felt that he’d bothered Agustin with his problems enough lately. He couldn’t tell Cass who was practically a stranger, or even Gen, who was worlds away from being a parent. He definitely couldn’t tell Cruz, who wasn’t speaking to him. Maybe he could tell Doc… Lightning really considered that one. But instead he got stuck on that sobering realization: he really didn’t have many people in his life.

For someone who’d been so scared of being all alone, he’d really done it to himself anyway, hadn’t he? What a depressing paradox. You try so hard to be everyone’s hero that you wind up a total loser.

Well, the whole point of this was supposed to be changing that. Starting with setting things right with Dusty. Lightning had thought that doing so would make everything else fall into place, but now that Lightning had done it, he still felt pretty lost.

He wandered over to his kitchen and absently started making a smoothie. Berries, greens, that collagen mix Lightning used to tell Cruz about— he thought of her again as he shook some into the blender. Everything seemed to remind him of her these days, and Lightning was starting to realize that was the pain of caring about someone. You still cared about them, even when you were far away (even if not physically so).

That was it, wasn’t it? His next step. He had to get through to Cruz. And he couldn’t force it, just as Agustin had advised him not to. He had to listen to her. And he had to back off if she told him to.

You can’t force her to forgive you. And hounding her, begging her, that’s guilt tripping and isn’t right. But apologize, sincerely. Let her decide what to do with it and accept her decision.

Apologize. Sincerely.

Lightning had never been sincere a day in his life. Or maybe he had, he’d just been so scared of it, he hadn’t let himself really feel it. But maybe it wasn’t too late to start. This was important. And sometimes important things were hard.

…Maybe he could build up to it, though. Prove himself in other ways first. That way, when he asked for Cruz’s forgiveness, maybe he’d finally feel like he had earned it.

He put down his phone and pressed “blend,” and his eyes wandered to a Magick Grand Prix magazine he’d left open on the countertop. There was an article about youth programs needing more support, not just coaches and manpower, but monetary support, equipment, the kind of stuff that you just couldn’t get unless you had funding, and funding could be scarce.

He thought about how hard Cruz worked to try and get her program funding. And he had the beginning of an idea.

It wouldn’t solve everything. But maybe it could be the beginning.

He just hoped it wasn’t too late.

#self para#the title is a mountain goats reference mak be proud of me#the song in question i feel like isn't that fitting yet but i listened to it on repeat writing this so i will post it later#when it is more fitting#anyway yes!

2 notes

·

View notes