#French Revolution of 1848

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

The two most memorable barricades of the June Revolution of 1848. Volume 5, Book 1, Chapter 1.

#Les miserables#les mis#My Post#The Barricade#French Revolution of 1848#Historical Pictures#The Brick#Les Mis Letters

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

I vaguely remembered that I’d woken up last night at 2am and scrambled desperately for my phone to Wikipedia-search something I just HAD to know, then immediately fell back to sleep.

But for the life of me, I could not remember what I had searched. Curious, I opened my phone’s browser to see this:

You know that feeling: it’s 2am and you really really need to immediately read the biography of Maximilien Robespierre. We’ve all been there.

#i do finally remember why but it’s boring: I wanted to know where he went to law school for some reason#it was at the Sorbonne ofc#i woke up an hour later from a dream about the French Revolution of 1848 so I should have guessed the nature of the Wikipedia search#very funny#stress dream unlocked: various french revolutions#shut up e#frev

519 notes

·

View notes

Text

Napoleon as a rallying cry during the revolutions in France during the 19th century

July Revolution (French Revolution of 1830):

French Revolution of 1848:

Source: The Pursuit of Power: Europe 1815-1914, Richard J. Evans

#The Pursuit of Power#Richard J. Evans#Evans#Napoleon#napoleon bonaparte#Talleyrand#Charles X#Thiers#Marmont#Lafitte#Jacques Lafitte#Louis-Philippe#Lafayette#Revolution#french revolution#July Revolution#1848 revolutions#Revolution of 1848#1848#napoleonic era#Blanc#first french empire#napoleonic#history#french history#my pics#book#book quotes#revolution of 1830#France

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Ideal Republic:

I don't know about you, but in France, there's increasingly justified complaints that the representative system is completely out of touch with its people. We need more democracy, better representation. A profound system change to address our problems. I would like a Republic with a president refusing to live in the Presidential Palace but rather in his apartment like the majority of French people, as President Mujica did. He would be less disconnected from the reality of the people because he would live among the majority of them (similarly to how French revolutionaries worked at the Tuileries but didn't live there). The case of President Mujica should no longer be an exception but the rule. The presidential palace should serve only as a workplace and to receive foreign dignitaries. All government members, including deputies, should now live with a salary decrease similar to that of the majority of French people. We can't ask the people to make efforts if we don't practice them ourselves. I would like a model based on the First Republic with a much more controlled executive, divided in the General Assembly as the Republicans proclaimed. I would like a new constitution as close as possible to that of 1793. Like the First Republic, I would like citizens who are not part of the government or the General Assembly to take the stand to voice their demands, difficulties, criticisms, absolutely everything. Government members who are under investigation by justice should no longer receive any special treatment. We citizens don't benefit from it, so why should they? After all, it is the government that should serve the people, not the other way around. Referendums should be well conducted, well respected, ensuring that the fundamental rights acquired after many struggles remain respected as inviolable rights (abolition of the death penalty, right to abortion, marriage for all, etc.). Social progress should continue even if it might displease some… Only this Republic could be the one that meets our needs… But I don't think I'll see it one day… Anyway, I've always thought that the rights we've acquired have only come after years of struggle, that revolutions happen in different periods. The most recent example that comes to mind is the one where we almost had a revolution in May 1968. There will surely be another day, we will have a real program for the people again, then it will be fought and it will be a cycle… But every concession we wrestle is a victory, and that's not a reason to give up (for example: there were real social revolutions in 1792, in 1830, in 1848, and in 1870, for example, even if in the end there were always regressions or the fact that these revolutions were buried or failed, they managed to secure very significant concessions and always to rise again, without all these revolutionaries we might even have been at risk of losing all our rights, we wouldn't have had them at all).

#France#revolution#french revolution#the communards#1848#1830#Republic#Third Republic#Fifth Republic

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Some post June Rebellion Marius x Cosette HCs after Valjean dies

. After Valjean dies in early March 1833, Marius and Cosette moved to Marseille ( which is also Valjean's birthplace )

. Marius becomes an investigative journalist in LA Marseillaise ( a neutral news reporting company in Marseille ), while Cosette becomes an art teacher at a Catholic school

. They have 4 children together : Victoire II ( born in 1834 May ), twins Marcelin II and Michel II ( born in 1836 ), and Adelaide ( born in 1838 )

. Marius and Cosette basically juggle between their careers, raising their 4 children, all that

. They work to heal their traumas together, and they can't bear to tell their children the sheer horror details of what they been through in the June Rebellion

. I mean, their children heard some stuff about that at those points, yet still

. On the night before the 1848 French Revolution in Feb for 3 days, Victoire II told her father that she wants to join her friends to defend her school

. Marius told his oldest daughter that he is very sorry, yet she and her siblings shall be in the basement for a few days till the whole hoopla is over

. Victoire sighed and went to the basement with her siblings

. The next morning when Marius and Cosette woke up

. They are HORRIFIED TO DISCOVER THAT VICTOIRE HAS SNUCK OUT ALREADY?!?!?!

. Cue Marius and Cosette scrambling to ride on some rental horses and ask around directions

. Ofc they told the small sized staff in tow of that house to watch over Victoire II's sibs in the basement

. Eventually they managed to find Victoire II joining her friends to help defend her school

. Cue Marius and Cosette risked their lives to rush to save their oldest daughter

. Luckily, she survived

. Unluckily, Victoire II literally nearly died that day and has to be hospitalized for injuries for 2 months

. That event made the Pontmercys closer over shared shock and grief on that

. After the 1848 French Revolution, despite the celebratory cries of victory against the July Monarchy ringing all across France, there is still much work to be done to recover France

. Victoire II's parents visited Victoire II regularly in that hospital. Victoire II's sibs stayed in a health spa for 2 months due to intense PTSD from the 1848 French Revolution

. Ofc Marius and Cosette worked to help their kids and each other recover from the 1848 French Revolution

. After the 1848 French Revolution, Marius soon founded his own social newsletter called La Lumiere, and Cosette switched to be an art teacher at the Marseille Art Museum

. Because they are HAUNTED with how their oldest daughter nearly died in that event, and they are also haunted with how several of their Co workers ( and several of the students in that school Cosette worked in before ) didn't make it in the 1848 French Revolution for some time.... 🤯🤯🥺🥺🥺😭😭😭

. Also also Cosette becomes a lead illustrator for Marius' newsletter after the 1848 French Revolution

. Before that, she already at times helped with illustrations with Marius' journals during his La Marseillaise days

���🤩🤩🥺🥺🥺

Victoire II and Marcelin II are more like their father

While Michel II and Adelaide are more like their mother

🤯🤯🤯🥺🥺🥺

It was around after the 1848 French Revolution did those 4 eventually knew what their parents really been through in the June Rebellion

Their parents profusely apologized to them for not telling them sooner due to ' fear of breaking their hearts '

And those 4 understand and forgive them

🤯🤯🥺🥺🥺

A thing is

Marius and Cosette will still be Republican leaning in the 1840s French Revolution

Yet their No. 1 priority especially then is to ensure the securities of their household and their children, especially from the machinations of Royalist thugs

🤯🤯🤯🤯🤯🤯

Plus in my Les Mis fics Cosette soon came to use her art classes as a form of art therapy for her students who been through a lot in the June Rebellion and later the 1840s French Revolution

🤯🤯🤯🥺🥺🥺

She also uses her visual arts skills as a form of helping Marius and their children as a form of art therapy especially after all they been through and such

🤯🤯🤯🥺🥺🥺

During her post Valjean's death era, Whenever she isn't art teaching, Cosette basically juggles with raising her children, managing that household, getting involved with community related matters often, and sometimes likes to hang out at parks with Marius, their children and their friends

She also sometimes likes to visit art galleries, similarly as she has sometimes done during the June Rebellion era ( sometimes with Valjean, her post Convent Era friends and later on Marius )

In the Les Mis book, Cosette came to have a penchant for visual arts

It certainly becomes therapeutic to her especially after all she been through

I'd love to develop that aspect more in my Les Mis fics

🤩🤩🤩🥺🥺🥺🥺

Like post Convent School Era Cosette defo becomes a quirky, gentle, dreamy and brave soft goth girl who carries her art supplies in her bags wherever she went, often wearing flowers on her hats and coiffures, and basically shows Marius and her loved ones a different outlook of life

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

that post about the seine giving everyone cholera in 1831 makes my eye twitch because it wasn't that parisians didn't know cholera existed, it was that they had a lucky break from major outbreaks of it until 1832 so if you look at the primary literature from right before then it's full of claims like the seine is clean because an 'enlightened' city needn't worry about disease. like however stupid you may think people in the past were it's more a function of their cultural chauvinism & climatic racism driving claims about the salubrity of parisian river water. also the dates matter because the 1832 outbreak was exacerbated by the upheaval of the 1830 revolution, and the pattern of revolution -> cholera epidemic repeated again after the 1848 revolution. and that pattern, particularly with 1832, really helped cement the notion in french public health that political unrest = literal disease, and became rhetorical fodder for the identity-formation that the rising bourgeoisie were engaging in wrt the linking of poverty, filth, and radical politics.

⬆️ stuff i would say if i were deeply unchill and unable to scroll past a joke post on a tuesday

443 notes

·

View notes

Text

The proletariat needs the state — this is repeated by all the opportunists, social-chauvinists and Kautskyites, who assure us that this is what Marx taught. But they “forget” to add that, in the first place, according to Marx, the proletariat needs only a state which is withering away, i.e., a state so constituted that it begins to wither away immediately, and cannot but wither away. And, secondly, the working people need a "state, i.e., the proletariat organized as the ruling class". The state is a special organization of force: it is an organization of violence for the suppression of some class. What class must the proletariat suppress? Naturally, only the exploiting class, i.e., the bourgeoisie. The working people need the state only to suppress the resistance of the exploiters, and only the proletariat can direct this suppression, can carry it out. For the proletariat is the only class that is consistently revolutionary, the only class that can unite all the working and exploited people in the struggle against the bourgeoisie, in completely removing it. The exploiting classes need political rule to maintain exploitation, i.e., in the selfish interests of an insignificant minority against the vast majority of all people. The exploited classes need political rule in order to completely abolish all exploitation, i.e., in the interests of the vast majority of the people, and against the insignificant minority consisting of the modern slave-owners — the landowners and capitalists. The petty-bourgeois democrats, those sham socialists who replaced the class struggle by dreams of class harmony, even pictured the socialist transformation in a dreamy fashion — not as the overthrow of the rule of the exploiting class, but as the peaceful submission of the minority to the majority which has become aware of its aims. This petty-bourgeois utopia, which is inseparable from the idea of the state being above classes, led in practice to the betrayal of the interests of the working classes, as was shown, for example, by the history of the French revolutions of 1848 and 1871, and by the experience of “socialist” participation in bourgeois Cabinets in Britain, France, Italy and other countries at the turn of the century. All his life Marx fought against this petty-bourgeois socialism, now revived in Russia by the Socialist-Revolutionary and Menshevik parties. He developed his theory of the class struggle consistently, down to the theory of political power, of the state. The overthrow of bourgeois rule can be accomplished only by the proletariat, the particular class whose economic conditions of existence prepare it for this task and provide it with the possibility and the power to perform it. While the bourgeoisie break up and disintegrate the peasantry and all the petty-bourgeois groups, they weld together, unite and organize the proletariat. Only the proletariat — by virtue of the economic role it plays in large-scale production — is capable of being the leader of all the working and exploited people, whom the bourgeoisie exploit, oppress and crush, often not less but more than they do the proletarians, but who are incapable of waging an independent struggle for their emancipation. The theory of class struggle, applied by Marx to the question of the state and the socialist revolution, leads as a matter of course to the recognition of the political rule of the proletariat, of its dictatorship, i.e., of undivided power directly backed by the armed force of the people. The overthrow of the bourgeoisie can be achieved only by the proletariat becoming the ruling class, capable of crushing the inevitable and desperate resistance of the bourgeoisie, and of organizing all the working and exploited people for the new economic system. The proletariat needs state power, a centralized organization of force, an organization of violence, both to crush the resistance of the exploiters and to lead the enormous mass of the population — the peasants, the petty bourgeoisie, and semi-proletarians — in the work of organizing a socialist economy.

Vladimir Ilyich Lenin, The State And Revolution

288 notes

·

View notes

Text

(limited to Europe because there are limited slots per poll)

*The Long 19th century is the period between the French Revolution and the The First World War.

The French Revolution: The original, the classic. It's got Robespierre and Marat and a Guillotine.

The Serbian Revolution: Resisting Ottoman Rule? Forming a new state? Creating a Constitution? Serbia kicked it off in the Balkans nevermind that it took three tries and three decades.

The Greek Revolution: Have you become hopelessly invested in the idea of Greece as the cradle of civilization? Do you want to die fighting for it in a way that is tragic and romantic? Then you might be Lord Byron.

The Carbonari Uprisings: Secret societies are more your speed? Here is one in Italy doing their best to try to make liberal reform happen.

The Decembrist Revolt: So, a bunch of officers came back from Napoleonic Europe wanting to see constitutional change and possibly the abolition of serfdom. Sounds reasonable, right? Right??

The July Revolution: Can you hear the people sing? You know the one, barricades and the most iconic painting in French history. Louis Philippe ends up on the throne and he is....sexy to someone.

The November Uprising: Congress Poland decides that they are sick of the tsar. Poland undertakes a tragically doomed struggle against Russia.

The Belgian Revolution: The Belgians decide to file for divorce from The United Netherlands. Leopold of Saxe-Coburg ends up on the throne and he's sexy.

The 1848 Revolutions: The Springtime of the People! Revolutions everywhere: France, Hungary, Poland, Austria, The Italian and German States.

The January Uprising: The third time is the charm on kicking out the tsar and making a Polish state, right?

The Paris Commune: Napoleon III abdicates and leaves after being thumped by the Prussians. For two months, a communist people's regime rules Paris.

The Russian Revolution of 1905: This is not the one with Lenin yet! This is the one that forces Nicky to create a Duma. Some consider it the dress rehearsal for what would come next.

#napoleonic sexyman tournament#we need a new tag for extra polls#this is why people like the 19th century by the way#look at all those revolutions

257 notes

·

View notes

Text

Source: The Catholic Northwest Progress, 22 October 1920

Written by Rev. Albert Muntsch, S. J., for the Press Bulletin Service of the C. B. of the C. V. Catholic teachers are so often asked why the Church forbids the reading of Hugo’s “Notre Dame de Paris” (The Hunchback of Notre Dame), and of “Les Miserables” that it seems worth while to set forth briefly the reasons of this condemnation. Both works are explicitly condemned, the former in a decree of July 28, 1834, the latter in one of June 20, 1864. Popular opinion ranks both books among the outstanding productions of world-literature. Those who share this view are frequently unable to give any reasonable ground for their admiration. They have heard others speak in glowing terms of the romances and have never formed an opinion based on close reading. Unfortunately, many books which have no literary or artistic value whatever thus achieve a wide reputation which all the opposition of sound criticism cannot restrict to sober limits. [. . .] "Les Miserables," a social romance, begun in 1848, was finished in 1862, and is an indictment against the existing order of society. The work glorifies opposition to the established social order, and though some of the characters are inspired by high ideals, the tendency of the work, as a whole, is revolutionary and unsound. It may be called a great Socialistic epic. There are of course eloquent pages in the book, and the social evils so mercilessly exposed, unfortunately weigh heavily upon large sections of every community. But this does not justify the tenor of the development of the tale. There is not only no need to spread a sentimental halo around an unfortunate mother like Fantine, from whom the first part of the story is named, but it is ethically wrong to do so. A moral transgression is always deserving of censure, and the writer who uses his literary art to ennoble wrongdoing is an enemy to society. His book ought to be branded as evil. As an illustration of the method employed by Hugo to belittle, and even to calumniate, as much as lay in his power, a sacred institution of the Church, we mention the strange and shockingly grotesque picture of religious orders in Part 11, Book 7, of “Les Miserables.” We read: “From the point of view of history, of reason. and of truth, monachism (the religious life), is condemned. . . . Monasteries . . . are detestable in the nineteenth century." In the same paragraph it is said that Italy and Spain are beginning to recover from the curse of monasticism, “thanks to the sane and vigorous hygiene of 1789 (the French Revolution).” The long eulogy of the bishop in the opening chapters of the book make this distorted and calumnious sketch all the more abominable. For unthinking persons may be led to believe that Hugo writes as a loyal son of the Church. No matter how one regards “the Index of Forbidden Books” drawn up by the Church, an unbiased mind will recognize the wisdom of the precautionary measures taken by her to safeguard the spiritual interests of her children. That promiscuous reading of pernicious literature has caused untold harm, no one can deny. A large amount of the irreligiousness of the modern world and the general looseness of morals may be attributed to the vicious productions of the press. Just now the works of Blasco Ibanez are widely advertised “with a great noise of tomtoms and circus paradings,” as one critic has well expressed it. But works like “The Shadow of the Cathedral” sow the seeds of anarchy and discontent among unthinking classes. To banish them from our people, or at least to restrict the sphere of their civil influence, is not an offense against art, but a high form of social service.

80 notes

·

View notes

Note

What do you think of the legacy of potatoes and how they have been the basis of numerous empires?

it's crazy i mean like. there was essentially an epidemic of revolutions across europe in 1848 (also known as 'springtime of the peoples'), starting with sicily in january and spreading across the continent to Poland, the Austrian Empire, Germany, Italy, and probably most notably, France (where they revolted against louis-phillipe, the french's 4th monarch ousting in 60 years lmao. they love their revolutions). But Britain managed to escape this year of Revolution unscathed, despite the growth of the "Chartist" movement and INSANE unrest in Ireland. the former was largely dealt w by scaring off the chartists with very little effort lol, but ireland never revolted bc britain used (some say accidentally, some disagree) the already-bad potato famine against ireland to the point where they were too hungry to revolt.

so tldr, potatoes are lovely but they're also dangerous weapons. keep ur eyes peeled

#u all have to deal with History Degree Potes for a second#brotes once said to me 'i dont trust potatoes. not after what they did to ireland'#thanks for the ask!

62 notes

·

View notes

Note

ive seeeen you mention listening to history podcasts before, are there any that youd recommend? I have looked at whats out there but a lot of the popular ones I saw seemed to be rather dubious if you get me

So an assortment off the top of my head

Mike Duncan's stuff is both generally very good and also the inspiration of 90% of the history podcasts I listen to, so useful for cultural literacy if nothing else. (He podcasted his way into being a bona fide public intellectual for a moment there!) History of Rome is exactly what it sounds like, a narrative history from the mythical foundation of the city to the fall of the Western Empire (getting much more detailed and in depth as it gets into the imperial era). Revolutions is an anthology on what can be called the great revolutions of the modern western world, with series on the English, American, French, Haitian, Spanish American, German/Italian/French again (1848), French round three (Paris commune), Mexican and Russian (also includes a semester-length intellectual history of 19th C europepan leftism) revolutions. First two series are fine but it really gets good with the French Revolution and the Haiti series is some of the best pop history I've listened to or read. Also doubles as just a decent history of the long 19th century in Europe.

Tides of History is the only one of this list that feels like it has an actual production budget and more than one person working on it as part of their actual job. The host is the other guy whose podcasted himself into being a bit of a public intellectual (would rec his substack!) The downside of having a budget is most of the older stuff being locked behind a paywall, which is a shame because the early seasons are some of the best approachable history on the late medieval and early early modern period in Europe I've heard or seen. The current season is about the late bronze age world, and continues to be excellent.

History of Byzantium is explicitly an attempt to pick off where Duncan left off and follow the Eastern Roman empire from the fall of the west to 1452 (it's still in progress, now well into the 13th century). Also much like History of Rome, it starts off fairly general and vague but gets much more detailed as it goes. The general narrative history is intercut with semi-regular interviews with academic historians about the subject of their expertise for more in depth and probably rigorous discussion.

Speaking of Byzantium and Friends is hosted by one of the more prominent working byzantinists and consists of absolutely nothing but that. Much, much more academic - there's a level of assumed background knowledge to get much of anything out of the episodes, and and a level of academic inside baseball, but accurcy-wise this is the podcast I trust most out of all of them.

History of Japan is, again, what it sounds like. One of many podcasts begun by a grad student probably procrastinating working on his thesis that has lasted long enough for him to graduate, get married, and settle into a full time job. Vast majority of episodes are 20-30-minute mini-histories on, say, the biography of a particular political figure or part of a mini-series on the spread of Buddhism or something (plus a few much, much longer series on e.g. the Meiji Restoration). Currently in the middle of remaking/expanding a series that's a general high-level survey of Japanese history to celebrate hitting episode 500.

Criminal Records shares a host with it, but is (intentionally) less rigorous and much more bantery (having two hosts helps, them being married presumably good for the chemistry), also technically a true crime podcast - specifically about weird crimes and legal cases throughout history. My favorite episode is the one on the oldest surviving court case in the record from ancient Sumeria.

The History of the Crusades and it's sequel Reconquista continue the trend of admirably self-explaining names. They're nearly-entirely narrative and political histories, so if you're not interested in crowns, marriages and wars probably give them a pass, but very granular and detailed as they go. Crusades finished after the fall of Jerusalem and then a follow-up about the Albigensian Crusade, Reconquista currently still ongoing (in the 11th century at the moment, I believe).

Pax Brittancia is the one I just finished binging as depression-ameliorating background noise and what I've been posting about recently. Another begun by a grad student avoiding their thesis who has since become a doctor (who had previously completed a podcast on the history of witchcraft, which I have not listened to). It's ostensibly a history of the British Empire, beginning with the Stuart Dynasty (and personal union with Scotland) and moving forward with sufficent attention to detail that after five years and change it's objectively just a very in depth history of the Wars of Three Kingdoms (incl. causes and aftermath). Includes many, many interviews with established historians, including a whole series on Covenanter Scotland and whether its rise should be considered a Scottish Revolution. The narrative just reached Cromwell's inauguration as Lord Protector.

143 notes

·

View notes

Text

Les Mis French History Timeline: all the context you need to know to understand Les Mis

Here is a simple timeline of French history as it relates to events in Les Miserables, and to the context of Les Mis's publication! A post like this would’ve really helped me four years ago, when I knew very little about 1830s France or the goals of Les Amis, so I’m making it now that I have the information to share! ^_^

This post will be split into 4 sections: a quick overview of important terms, the history before the novel that’s important to the character's backstories, the history during the novel, and then the history relevant to the 1848-onward circumstances of Hugo’s life and the novel’s publication.

Part 1: Overview

The novel takes place in the aftermath of the Battle of Waterloo, during a period called the Restoration.

The ancient monarchy was overthrown during the French Revolution. After a series of political struggles the revolutionary government was eventually replaced by an empire under Napoleon. Then Napoleon was defeated and sent into exile— but then he briefly came back and seized power for one hundred days—! and then he was defeated yet again for good at the battle of Waterloo in 1815.

After all that political turmoil, kings have been "restored" to the throne of France. The novel begins right as this Restoration begins.

The major political parties important to generally understanding Les Mis (Wildly Oversimplified) are Republicans, Liberals, Bonapartists, and Royalists. It’s worth noting that all these ‘party terms’ changed in meaning/goals over time depending on which type of government was in power. In general though, and just for the sake of reading Les Mis:

Republicans want a Republic, where people have power rather than monarchs and (in this context) elect their leaders democratically— they’re the very left wing progressive ones, and are heavily outcast/censored/policed. Les Amis are Republicans.

Liberals: we don’t have time to go into it, but I don’t think there are any characters in Les Mis defined by their liberalism.

Bonapartists are followers of Napoleon Bonaparte I, who led the Empire. Many viewed the Emperor as more favorable or progressive to them than a king would be. Georges Pontmercy is a Bonapartist, as is Pere Fauchelevent.

Royalists believe in the divine right of Kings; they’re conservative. Someone who is extremely royalist to the point of wanting basically no limits on the king’s power at all are called “Ultraroyalists” or “ultra.” Marius’s conservative grandfather Gillenromand is an ultra royalist. Hugo is also very concerned with criticizing the "Great Man of History," the view that history is pushed forward by the actions of a handful of special great men like kings and emperors. Les Mis aims to focus on the common masses of people who push history forward instead.

Part 2: Timeline of History involved in characters’ Backstories

1789– the March on the bastille/ the beginning of the original French Revolution. A young Myriel, who is then a shallow married aristocrat, flees the country. His family is badly hurt by the Revolution. His wife dies in exile.

1793– Louis XVI is found guilty of committing treason and sentenced to death. The Conventionist G—, the old revolutionary who Myriel talks to, votes against the death of the king.

1795: the Directory rules France. Throughout much of the revolution, including this period, the country is undergoing “dechristianization” policies. Fantine is born at this time. Because the church is not in power as a result of dechristianization, Fantine is unbaptized and has no record of a legal given name, instead going by the nickname Fantine (“enfantine,” childlike.)

1795: The Revolutionary government becomes more conservative. Jean Valjean is arrested.

1804: Napoleon officially crowns himself Emperor of France. the Revolution’s dream of a Republic is dead for a bit. At this time, Myriel returns from his exile and settles down in the provinces of France to work as a humble priest. Then he visits Paris and makes a snarky comment to Napoleon, and Napoleon finds him so witty that he appoints him Bishop.

Part 3: the novel actually begins

1815: Napoleon is defeated at the Battle of Waterloo by the allied nations of Britain and Prussia. Read Hugo’s take on that in the Waterloo Digression! He gets a lot of facts wrong, but that’s Hugo for you.

Marius’s father, Baron Pontmercy, nearly dies on the battlefield. Thenardier steals his belongings.

After Napoleon is defeated, a king is restored to the throne— Louis XVIII, of the House of Bourbon, the ancient royal house that ruled France before the Revolution. In order to ensure that Louis XVIII stays on the throne, the nations of Britian, Prussia, and Russia, send soldiers occupy France. So France is, during the early events of the novel, being occupied by foreign soldiers. This is part of why there are so many references to soldiers on the streets and garrisons and barracks throughout the early portions of the novel. The occupation officially ended in 1818.

1815 (a few months after Waterloo): Jean Valjean is released from prison and walks down the road to Digne, the very same road Napoleon charged down during his last attempt to seize power. Many of the inns he passes by are run by people advertising their connections to Napoleon. Symbolically Valjean is the poor man returning from exile into France, just as Napoleon was the Great Man briefly returning from exile during the 100 days, or King Louis XVIII is the Great King returning from exile to a restored throne.

1817: The Year 1817, which Hugo has a whole chapter-digression about. Louis XVIII of the House of Bourbon is on the throne. Fantine, “the nameless child of the Directory,” is abandoned by Tholomyes.

1821: Napoleon dies in exile.

1825: King Louis XVIII dies. Charles X takes the throne. While Louis XVIII was willing to compromise, Charles X is a far more conservative ultra-royalist. He attempts to bring back something like the Pre-Revolution style of monarchy.

Underground resistance groups, including Republican groups like Les Amis, plot against him.

1827-1828: Georges Pontmercy, bonapartist veteran of Waterloo, dies. Marius, who has been growing up with his abusive Ultra-royalist grandfather and mindlessly repeating his ultra-royalist politics, learns how much his father loved him. He becomes a democratic Bonapartist.

Marius is a little bit late to everything though. He shouts “long live the Emperor!” Even though Napoleon died in 1821 and insults his grandfather by telling him “down with that hog Louis XVIII” even though Louis XVIII has been dead since 1825. He’s a little confused but he’s got the spirit.

Marius leaves his grandfather to live on his own.

1830: “The July Revolution,” also known as the “Three Glorious Days” or “the Second French Revolution.” Rebels built barricades and successfully forced Charles X out of power.

Unfortunately, TL;DR moderate politicians prevented the creation of a Republic and instead installed another more politically progressive king — Louis-Philippe, of the house of Orleans.

Louis-Philippe was a relative of the royal family, had lived in poverty for a time, and described himself as “the citizen-king.” Hugo’s take on him is that he was a good man, but being a king is inherently evil; monarchy is a bad system even if a “good” dictator is on the throne.

The shadow of 1830 is important to Les Mis, and there’s even a whole digression about it in “A Few Pages of History,” a digression most people adapting the novel have clearly skipped. Les Amis would’ve probably been involved in it....though interestingly, only Gavroche and maybe Enjolras are explicitly confirmed to have been there, Gavroche telling Enjolras he participated “when we had that dispute with Charles X.”

Sadly we're following Marius (not Les Amis) in 1830. Hugo mentions that Marius is always too busy thinking to actually participate in political movements. He notes that Marius was pleased by 1830 because he thinks it is a sign of progress, but that he was too dreamy to be involved in it.

1831: in “A Few Pages of History” Hugo describes the various ways Republican groups were plotting what what would later become the June Rebellion– the way resistance groups had underground meetings, spread propaganda with pamphlets, smuggled in gunpowder, etc.

Spring of 1832: there is a massive pandemic of cholera in Paris that exacerbates existing tensions. Marius is described as too distracted by love to notice all the people dying of cholera.

June 1st, 1832: General Lamarque, a member of parliament often critical of the monarchy, dies of cholera.

June 5th and 6th, 1832: the June Rebellion of 1832:

Republicans, students, and workers attempt to overthrow the monarchy, and finally get a democratic Republic For Real This Time. The rebellion is violently crushed by the National Guard.

Enjolras was partially inspired by Charles Jeanne, who led the barricades at Saint-Merry.

Part 4: the context of Les Mis’s publication

February 1848: a successful revolution finally overthrows King Louis Philippe. A younger Victor Hugo, who was appointed a peer of France by Louis-Philippe, is then elected as a representative of Paris in the provisional revolutionary government.

June 1848: This is a lot, and it’s a thing even Hugo’s biographers often gloss over, because it’s a horrific moral failure/complexity of Hugo’s that is completely at odds with the sort of politics he later became known for. The short summary is that in June 1848 there was a working-class rebellion against new labor laws/forced conscription, and Victor Hugo was on the “wrong side of the barricades” working with the government to violently suppress the rebels. To quote from this source:

Much to the disappointment of his supporters, in [Victor Hugo’s] first speech in the national assembly he went after the ateliers or national workshops, which had been a major demand of the workers. Two days later the workshops were closed, workers under twenty-five were conscripted and the rest sent to the countryside. It was a “political purge” and a declaration of war on the Parisian working class that set into motion the June Days, or the second revolution of 1848—an uprising lauded by Marx as one of the first workers’ revolutions. As the barricades went up in Paris, Hugo was tragically on the wrong side. On June 24 the national assembly declared a state of siege with Hugo’s support. Hugo would then sink to a new political low. He was chosen as one of sixty representatives “to go and inform the insurgents that a state of siege existed and that Cavaignac [the officer who had led the suppression of the June revolt] was in control.” With an express mission “to stop the spilling of blood,” Hugo took up arms against the workers of Paris. Thus, Hugo, voice of the voiceless and hero of workers, helped to violently suppress a rebellion led by people whom he in many ways supported—and many of whom supported him. With twisted logic and an even more twisted conscience, Hugo fought and risked his life to crush the June insurrection.

There is an otherwise baffling chapter in Les Mis titled "The Charybdis of the Faubourg Saint Antoine and the Scylla of the Fauborg Du Temple," where Hugo goes on a digression about June of 1848. Hugo contrasts June of 1848 with other rebellions, and insists that the June 1848 Rebellion was Wrong and Different. It is a strangely anti-rebellion classist chapter that feels discordant with the rest of the book. This is because it is Hugo's effort to (indirectly) address criticisms people had of his own involvement in June 1848, and to justify why he believed crushing that rebellion with so much force was necessary. The chapter is often misused to say that Hugo was "anti-violent-rebellion all the time" (which he wasn't) or that "rebellion is bad” is the message of Les Mis (which it isn't) ........but in reality the chapter is about Hugo attempting to justify his own past actions to the reader and to himself, actions which many people on his side of the political spectrum considered a betrayal. He couldn't really have written a novel about the politics of barricades without addressing his actions in June 1848, and he addressed them by attempting to justify them, and he attempted to justify them with a lot of deeply questionable rhetoric. 1848 is a lot, and I don't fully understand all the context yet-- but that general context is necessary to understand why the chapter is even in the novel. Late 1848/1849: Quoting from the earlier source again:

In the wake of the revolution, Hugo tried to make sense of the events of 1848. He tried to straddle the growing polarization between, on the one hand, “the party of order,” which coalesced around Napoleon’s nephew Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte, who in December 1848 had been elected France’s president under a new constitution, and the “party of movement” (or radical Left) that, in the aftermath of 1848, had made considerable advances. In this climate, as Hugo increasingly spoke out, and faced opposition and repression himself, he was radicalized and turned to the Left for support against the tyranny and “barbarism” he saw in the government of Louis Napoleon. The “point of no return” came in 1849. Hugo became one of the loudest and most prominent voices of opposition to Louis Napoleon. In his final and most famous insult to Napoleon, he asked: “Just because we had Napoleon le Grand [Napoleon the Great], do we have to have Napoleon le petit [Napoleon the small]?” Immune from punishment because of his role in the government, Bonaparte retaliated by shutting down Hugo’s newspaper and arresting both his sons.

Thenardier is possibly meant to be Hugo’s caricature of Louis-Napoleon/Napoleon III. He is “Napoleon the small,” an opportunistic scumbag leeching off the legacy of Waterloo and Napoleon to give himself some respectability. He is a metaphorical ‘graverobber of Waterloo’ who has all of Napoleon’s dictatorial pettiness without any of his redeeming qualities.

It’s also worth noting that Marius is Victor “Marie” Hugo’s self-insert. Hugo’s politics changed wildly over time. Like Marius he was a royalist when was young. And like Marius, he looked up to Napoleon and to Napoleon III, before his views of them were shattered. This is reflected in the way Marius has complicated feelings of loyalty to his father (who’s very connected to the original Napoleon I) and to Thenardier (who’s arguably an analogue for Napoleon IiI.)

1851:

On December 2, 1851, Louis Napoleon launched his coup, suspending the republic’s constitution he had sworn to uphold. The National Assembly was occupied by troops. Hugo responded by trying to rally people to the barricades to defend Paris against Napoleon’s seizure of power. Protesters were met with brutal repression. Under increasing threat to his own life, with both of his sons in jail and his death falsely announced, Hugo finally left Paris. He ultimately ended up on the island of Guernsey where he spent much of the next eighteen years and where he would write the bulk of Les Misérables. It was from here that his most radical and political work was smuggled into France.

Hugo arguably did some of his most important political work after being exiled. In Guernsey, he aided with resistance against the regime of Napoleon III. Hugo’s popularity with the masses also meant that his exile was massive news, and a thing all readers of Les Miserables would’ve been deeply familiar with.

This is why there are so many bits of Les Mis where the narrator nostalgically reflects on how much they wish they were in Paris again —these parts are very political; readers would’ve picked up that this was Victor Hugo reflecting on he cruelty of his own exile.

1862-1863: Les Mis is published. It is a barely-veiled call to action against the government of Napoleon III, written about the June Rebellion instead of the current regime partially in order to dodge the censorship laws at the time.

Conservatives despise the book and call it the death of civilization and a dangerous rebellious evil godless text that encourages them to feel bad for the stupid evil criminal rebel poors and etc etc etc– (see @psalm22-6 ‘s excellent translations of the ancient conservative reviews)-- but the novel sells very well. Expressing approval or disapproval of the book is considered inherently political, but fortunately it remains unbanned.

…And that’s it! An ocean of basic historical context about Les Mis!

If anyone has any corrections or additions they would like to make, feel free to add them! I have researched to the best of my ability, but I don’t pretend to be perfect. I also recommend listening to the Siecle podcast, which covers the events of the Bourbon Restoration starting at the Battle of Waterloo, if you're interested in learning more about the period!

#les mis#someone in a discord server asked about this a while back#so i put it together!#it’s basically what I told them in the discord server but as a tumblr post#and with some extra stuff I forgot to say#but yeAH maybe if more historical information gets spread#we’ll get more canon era fanfics >:3333#which are always fun

512 notes

·

View notes

Text

Muhammad Ali Pasha Viceroy of Egypt

Artist: Auguste Couder (French, 1789–1873)

Date: 1841

Medium: OIl on canvas

Collection: Museum of the History of France, Palace of Versailles, Paris, France

Muhammad Ali of Egypt

Muhammad Ali (4 March 1769 – 2 August 1849) was the Ottoman Albanian viceroy and governor who became the de facto ruler of Egypt from 1805 to 1848, widely considered the founder of modern Egypt. At the height of his rule, he controlled Egypt, Sudan, Hejaz, the Levant, Crete and parts of Greece.

He was a military commander in an Albanian Ottoman force sent to recover Egypt from French occupation under Napoleon. Following Napoleon's withdrawal, Muhammad Ali rose to power through a series of political maneuvers, and in 1805 he was named Wāli (governor) of Egypt and gained the rank of Pasha.

As Wāli, Ali attempted to modernize Egypt by instituting dramatic reforms in the military, economic and cultural spheres. He also initiated a violent purge of the Mamluks, consolidating his rule and permanently ending the Mamluk hold over Egypt.

Militarily, Ali recaptured the Arabian territories for the sultan, and conquered Sudan of his own accord. His attempt at suppressing the Greek rebellion failed decisively, however, following an intervention by the European powers at Navarino. In 1831, Ali waged war against the sultan, capturing Syria, crossing into Anatolia and directly threatening Constantinople, but the European powers forced him to retreat. After a failed Ottoman invasion of Syria in 1839, he launched another invasion of the Ottoman Empire in 1840; he defeated the Ottomans again and opened the way towards a capture of Constantinople. Faced with another European intervention, he accepted a brokered peace in 1842 and withdrew from the Levant; in return, he and his descendants were granted hereditary rule over Egypt and Sudan. His dynasty would rule Egypt for over a century, until the revolution of 1952 when King Farouk was overthrown by the Free Officers Movement led by Mohamed Naguib and Gamal Abdel Nasser, establishing the Republic of Egypt.

#portrait#painting#military leader#egyptian history#muhammad ali of egypt#viceroy of egypt#muhamad ali pasha#sitting#three quarter length#costume#turban#ottoman albanian#auguste couder#french painter#sword#french art#fine art#oil on canvas#19th century painting#artwork#european art#19th century art

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

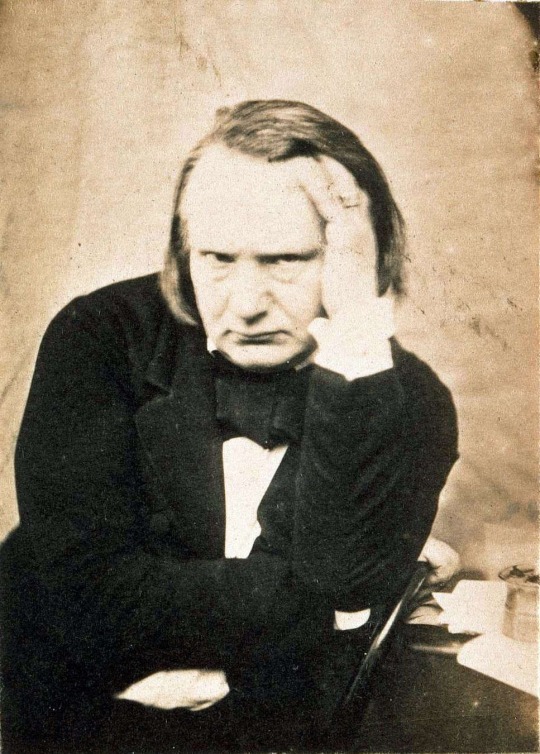

Victor Hugo’s speech in support of Napoleon, and his support to lift the ban on the Bonaparte family

(Left: Victor Hugo, Right: Elderly Jérôme Bonaparte)

Excerpt from Jonathan Beecher, Writers and Revolution: Intellectuals and the French Revolution of 1848

—————-

Hugo was fascinated by the Praslin affair and wrote about it at length in his journals. But he was more deeply engaged by another issue brought to the Chamber of Peers in June, 1847 – the petition of Napoleon’s only surviving brother, Jérôme Bonaparte, who sought the repeal of the law exiling members of the Bonaparte family. “I declare without hesitation,” Hugo told the peers. “I am on the side of exiles and proscrits.”

Не obviously could not know that he himself was to spend almost two decades in exile. But one exile who mattered to Hugo in 1847 was the first Napoleon. In his speech to the Chamber of Peers Hugo contrasted the pettiness and corruption of the July Monarchy with the grandeur of Napoleon’s Empire:

As for me, in witnessing the collapse of conscience, the reign of money, the spread of corruption, the taking of the highest places by people with the lowest passions, (Prolonged reaction) in witnessing the woes of the present time, I dream of the great deeds of the past, and I am now and then tempted to say to the Chamber, to the press, to all of France: “Wait, let us talk a little of the Emperor. That will do us good!” (Intense and profound agreement).

After this speech, the elderly Jérôme Bonaparte personally thanked Hugo; and his daughter, the Princess Mathilde, invited him to dinner. Hugo was now regarded in some quarters as a Bonapartist.

—————-

[Italics in original]

“La Famille Bonaparte,” OC Politique, Laffont, 138-139.

#victor Hugo#Jerome Bonaparte#jerome#Napoleon’s brothers#Napoleon’s family#napoleon#napoleonic era#napoleonic#first french empire#napoleon bonaparte#french empire#19th century#france#history#bonapartism#bonapartist#1848 revolutions#1840s#1847#Hugo#writers and Napoleon

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Georges Sand (1804-1876)

Here’s another anecdote to illustrate the complexity of the political landscape after 1848, featuring the historical figure of George Sand.

The writer George Sand claimed to be a republican, even a socialist. She applauded the revolution of 1848 and was reportedly opposed to Napoleon III. She socialized with foreign revolutionaries and republican figures.

Yet, when the Third Republic came into being, she fully and unhesitatingly supported the repression of the Paris Commune. When soldiers began fraternizing with the Communards during the attempt to retake the cannons held by the National Guard, she wrote on March 18, 1871, “I am sickened by it.”

One might argue that her disillusionment was due to the execution of Generals Lecomte and Thomas by their own mutinous troops who had joined the Communards—except that her writing on the subject dates from March 20, 1871.

She described the Communards as “grossly stupid asses or low-life scoundrels. The crowd that follows them is partly duped and mad, partly vile and malicious,” adding that “the horrible adventure continues.” She claimed that “They extort, they threaten, they arrest, they judge. They prevent the courts from functioning.” While she occasionally questioned the obvious lies told by the Versaillais, like the myth of the pétroleuses, she excused the disproportionate violence the Versaillais inflicted on the Communards. She wrote, “On the side of law and order, they are no gentler, but the Federates’ rage is so appalling that it ignites the rage of the legal authorities.” In another letter, she said, “We do not yet know if the fighting was deadly for our poor soldiers. I pity the others less: they brought it on themselves.”

She fully supported Thiers and displayed considerable bad faith towards the Communards, refusing to acknowledge the social reforms they had enacted, such as abolishing night work for bakers. She sarcastically responded, “And what about the sewer workers?”

She refused even to acknowledge the reasons behind the Communards’ rebellion: the fall of Napoleon III’s dictatorship, Bazaine’s disgraceful conduct, the fact that the new regime forming a republic was composed of monarchists while Paris was predominantly republican (in fact, the monarchists saw this regime as a transition towards a new monarchy, not a republic—an obvious red flag for the Communards dreaming of a fraternal republic), the abolition of wages, which had been one of the few sources of income for workers, the rent moratorium, the sacrifice of the Parisian people during the siege, and so on...

When Victor Hugo, one of the few writers to demand clemency and justice for the Communards (many writers were either lukewarm or hostile to the Paris Commune) , wrote in their favor, George Sand remarked that he had missed a good opportunity to stay silent.

Thus, George Sand, who was positioned somewhere on the far left in 1848 as a socialist republican, had become part of the most conservative wing at the start of the Third Republic and approves the repression of the Paris Commune .

P.S.: Off-topic, but I am exasperated by the fact that the Convention of Year II is constantly vilified by pseudo-historical TV programs, certain school curricula, or films, while Thiers and his Versaillais friends, who carried out a disproportionate repression (some say 20,000 dead) in one or two weeks in Paris, are given a free pass.

Post on a Short Period Concerning Political Spectrums from 1789 to 1848 to Counter Misconceptions About the Far Left and Far Right

Sociétés des Jacobins (Jacobin Societies)

We all know the famous phrase: “The far right and the far left are the same thing; they’re no better, etc.” However, the far right and the far left are clearly not the same. This definition should not be taken literally, as it pertains more to the Restoration period concerning property rights (and even then, it’s more complex). The far right believes that property should belong to the traditional elites (the emigrated nobility), while the far left has a different view like sharing the property for maximum people . And first, on which political spectrum are we basing this? From which period?

In 1789, those considered far left were deputies like Pétion, François Buzot, and Maximilien Robespierre. Non-deputies aligned with the far left included figures like Danton, Camille Desmoulins, and Manon Roland, among many others.

However, during the second revolution in 1792, these figures would split. What came to be known as the Girondins (though there were many differences within this group) would constitute the more conservative wing (including Buzot, Pétion, and Manon Roland), while the Montagnards represented the far left. Yet, on the issue of slavery, many from both sides agreed on its abolition: Brissot proposed a gradual abolition, Sonthonax was sent to Saint-Domingue to enforce it, and Abbé Raynal (though seemingly conservative on property rights) was highly reformist on slavery, even calling Toussaint Louverture the “Black Spartacus.” The Montagnards, like Danton and Jean-Paul Marat (who supported the Haitian revolt and predicted its independence), joined in this cause, as did the Hébertists like Pierre Gaspard Chaumette, who shared Marat's views on Haiti.

The first major division between the Girondins and the Montagnards was over the issue of war, and it’s clear that the Montagnards were ultimately proven right on these question. What we now call the far left of this period consisted of elements considered a faction called the Hébertists (including individuals like Momoro, Chaumette, Hébert, François Hanriot, Charles Philippe Ronsin, Vincent François Nicolas, etc.) and another group known as the Enragés (Jacques Roux, Théophile Leclerc, Jean-François Varlet, Pauline Léon, Claire Lacombe, etc.). These two factions were also called ultra-revolutionaries and were much more socially engaged on certain political issues than Montagnards like Robespierre, Desmoulins, Danton, etc.

During the insurrection from May 31, 1793, to June 2, 1793, in which the Paris Commune, led in part by François Hanriot (following the arrest of Hébert and the Sans-Culotte delegation demanding his release, along with Isnard’s speech and the Commission of Twelve), expelled 21 Girondins who were initially placed under house arrest (we all know what happened next, but that’s not the focus here). The Montagnards who approved this insurrection portrayed themselves as allies of the Sans-Culottes. However, it’s important to note that not many of them viewed this leftist faction favorably (Marat became an opponent of Jacques Roux, and after his death, his widow Simone Evrard gave a speech against Jacques Roux and Théophile Leclerc among others ). The Committee of Public Safety and the Convention illegally persecuted Jacques Roux to the point where he committed suicide, suggesting that the Montagnards were beginning to shift further to the right. Furthermore, there were internal conflicts within the far left. The Hébertists clashed with the Enragés and later took up their petitions after many of them were removed from the political scene.

Later, on September 5, 1793, as the French Revolution seemed more endangered than ever, the Commune, led by figures like Chaumette, Hanriot, and Pache, arrived at the Convention without opposition, securing concessions such as the maximum price controls and the raising of a revolutionary army. The Montagnards seemed ready once again to support this far left on some points. However, conflicts and internal struggles soon reemerged. This time, the Indulgents, including Camille Desmoulins, Georges Jacques Danton, and Pierre Philippeaux, formed the Montagnards’ right wing. Initially, the majority of the Convention supported them against the elements considered far left (notably Robespierre, among others), but the majority of the Committee of Public Safety eventually realized they had also underestimated the Indulgents and opted for a middle-ground policy. The struggles among these different factions further weakened the Montagnards. However, they all shared a common goal of celebrating the abolition of slavery. This wasn’t enough for reconciliation; most far-left elements (Pache and Hanriot were notably spared from the Hébertist arrests) were politically eliminated (and it’s important to note that Billaud-Varenne and Collot d’Herbois, who represented the far left of the Committee of Public Safety, participated in this elimination).

Regarding property rights, the entire political class was very timid, even the Enragés and Hébertists, who were more focused on economic issues like taxation. However, some like Momoro apparently began to consider land redistribution like sharing large farms, but without a clear plan (and far from any notion of collectivization of agriculture) . There was a concession made by the Convention on property rights with the Ventôse Laws, perhaps? Previously, when the property of someone convicted of being an enemy of the Republic was seized, it went directly to the state. With these laws, the property was supposed to be redistributed to the needy, perhaps even the property left by émigrés. This was rarely, if ever, implemented.

Later, the eliminations continued with the Indulgents, internal struggles persisted in Thermidor, and the left suffered its final blow following the repression of May 20, 1795.

Indeed, even before May 20, 1795, there was a rightward turn at the end of 1794. In 1795, economic liberalism exacerbated the situation of the popular classes, leading to the insurrection of 1st Prairial Year III. The repression provided an opportunity for the right to eliminate from the political scene people like Goujon and Charles Gilbert Romme, who were considered the last Montagnards.

During the Directory, new far-left elements emerged, the most well-known being the Babouvists. Gracchus Babeuf’s “Manifesto of the Equals” was seen as promoting equality. Nevertheless, while some consider Babeuf to be a precursor to communism and he did advocate for deep social change, his interest was limited to agricultural domains. Lazare Carnot, who led the repression of the Babouvists, was seen as belonging to the right political wing .

The most interesting case considered far left is the neo-Jacobin Bernard Metge. In his work “Dialogue between a Representative of the People and a Former Administrator,” he sharply criticizes the Council of Five Hundred for ignoring the opinions of citizens, yet he also delivers a violent critique of the Babouvists, arguing that their ideology would, in his own words, produce nothing but lazy people. He wrote to the Minister of Police from prison, where he was detained, saying, “Indeed, preach the sharing and equality of goods, and you will have lazy people.” Although a fierce opponent of Sieyès, he advocated political liberalism and supported the Constitution of Year III. However, in his writing that sealed his fate, “The Turk and the French Soldier,” we see another side of Metge: he could be interpreted as opposing expansionist and conquest wars, notably by defending the Egyptians, but also as glorifying the right to resist. He also glorifies Brutus.

When he was arrested and executed by the Bonaparte regime (then the First Consul) for his opinions, he was considered one of the 34 anarchist leaders by the Brumaire regime. On this political spectrum, he was seen as a far-left figure, while on another spectrum, like in 1794 or around 1848, he would likely have been considered a right-wing figure. Metge was executed in a parody of justice. For more details on this revolutionary, visit this Tumblr post: https://www.tumblr.com/nesiacha/756533326215528448/the-jacobins-executed-by-bonaparte.

The most interesting example from this period is Lazare Carnot. Initially a Montagnard in 1793 when he was on the Committee of Public Safety, during the Directory, he took an increasingly right-wing position, including the repression of the Babouvists, where even Barras hesitated. He was certainly the Minister of War under Bonaparte, but in a sense, he found himself once again on the far left of the political spectrum under Bonaparte’s Consulate (a deliberate provocation on my part to better highlight the complexity of different periods on the political spectrum) because he was in the official opposition (after all, the rest of the opposition was either silenced, imprisoned, or deported, like Félix Lepeletier, etc.). He was marginalized for opposing the creation of the Empire.

Then we have the case of the Restoration with the “Chambre introuvable” appointed by Louis XVIII, long considered a chamber more royalist than the King (including figures like Louis de Bonald). Some analyses tend to moderate this; while it’s true there were émigrés from the nobility, the bourgeoisie aspiring to be ennobled, turncoats, and provincial notables, it’s also true that ultra-royalists like Charles X influenced it, making it far more right-wing politically than any other period. Decazes and, more importantly, François Guizot stood up to the ultra-royalists and advised dissolving the Chamber.

Chambre introuvable

Constitutionalists (39) Color to the left Ultraroyalists (350) Even if we have to give more thought to the ultra-royalist side

Yet, under Louis Philippe I’s political spectrum, Guizot was one of the most conservative figures. He was the staunchest defender of conservative and right-wing policies.

François Guizot (1787-1874) painted by Jean-Georges Vibert after a portrait by Paul Delaroche.

Through all these examples, I wanted to caution against the misconception that far left equals far right. History has shown the opposite through the examples cited above, demonstrating that the economic or property-related views of the far left and far right are not the same at all. Individuals situated on the far left can shift to the most conservative right-wing positions depending on the political spectrum of the period, and vice versa, without necessarily changing their political ideas.

Sources:

Antoine Resche

Jean Marc Schiappa

Jean Clément Martin

Bernard Gainot

#frev#french revolution#louis xviii#Charles X#1790s#1840s#1848#napoleon#III#political spectrum#1870s#George Sand#victor hugo#paris commune

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Liberty Leading the People (1830) 🎨 Eugene Delacroix 🏛️ The Louvre 📍 Paris, France

Perhaps Delacroix’s most influential and most recognizable paintings, Liberty Leading the People was created to commemorate the July Revolution of 1830, which removed Charles X of France from power. Delacroix wrote in a letter to his brother that a bad mood that had been hold of him was lifting due to the painting on which he was embarking (the Liberty painting), and that if he could not fight for his country then at least he would paint for it. The French government bought the painting in 1831, with plans to hang it in the room of the new king Louis-Philippe, but it was soon taken down for its revolutionary content. Lady Liberty was eventually the model for the Statue of Liberty, which was given to the United States 50 years later, and has also been featured on the French banknote.

Peint de septembre à décembre 1830 dans l'atelier loué par Eugène Delacroix au 15 (actuel n°17 ?) quai Voltaire, à Paris ; envisagé pour la deuxième Exposition au profit des blessés de Juillet 1830, galerie de la Chambre des Pairs (palais du Luxembourg), Paris, janvier 1831 (n° 508 du livret sous le titre "Une Barricade"), en réalité non prêté ; admis par le jury le 13 avril 1831 et exposé au Salon de 1831 (ouvert du 1er mai au 15 août), Paris, Musée royal (Louvre), n° 511 du livret sous le titre "Le 28 juillet. La liberté guidant le peuple" (n° 1380 du registre d'entrée des ouvrages au Salon, sous le titre "La Liberté guidant le peuple au 29 juillet" [sic], aux dimensions de "293 x 358 cm" cadre compris) ; envisagé comme achat de la Liste civile du roi Louis-Philippe Ier, en juillet 1831, au prix de 2 000 francs, finalement acheté à l'artiste par le ministère du Commerce et des Travaux publics en août 1831, au prix de 3 000 francs (en remplacement de la commande à Delacroix, au même prix, d'un tableau d'histoire ayant pour sujet "Le roi Louis-Philippe Ier visitant la chaumière où il logea près de Valmy, le 8 juin 1831", annulée suite au désistement de Delacroix) ; présenté au musée du Luxembourg, Paris, en 1832 et en 1833 (n° 160 du supplément au catalogue du musée) ; mis en réserve vers 1833-1834 ; confié à l'artiste vers 1839 qui le met en dépôt au domicile de sa tante, Félicité Riesener, et de son cousin Léon Riesener, à Frépillon (Val-d'Oise) ; réclamé à l'artiste par la direction des Musées nationaux (ministère de l'Intérieur) en mars 1848 (Delacroix demande à cette occasion une augmentation du prix de 7 000 francs, soit un total de 10 000 francs ; cette augmentation lui est refusée) ; prêté par Delacroix au peintre et entrepreneur lyonnais Alphonse Jame entre mai 1848 et mars 1849, en vue d'être exposé à Lyon, contre 1000 francs (payés en deux versements de 500 francs, le 11 septembre 1849 et le 8 mars 1850) ; rentré à Paris et restitué à l'administration en mars 1849 ; possiblement présenté au musée du Luxembourg, Paris, à partir de juin 1849 jusqu'en 1850 (mais absent du catalogue du musée) ; mis en réserve dans les magasins du musée du Louvre de 1850 à 1855 ; présenté à l'Exposition universelle, Palais de l'Industrie et des Beaux-arts, Paris, 1855, n° 2926 du livret ; mis en réserve dans les magasins des Musées impériaux de 1856 à 1863 ; présenté au musée du Luxembourg, Paris, de 1863 à 1874 ; déplacé du musée du Luxembourg au musée du Louvre en novembre 1874 ; inventorié pour la première fois, sous le n° "R.F. 129", en 1875 et présenté à partir de cette date dans la salle des États au musée du Louvre ; mis en sécurité pendant la Première Guerre mondiale au couvent des Jacobins, à Toulouse (Haute-Garonne) de 1914 à 1918 ; restauré par Lucien Aubert (nettoyage et réintégration de la couche picturale) à Paris en 1920 ; mis en sécurité pendant la Seconde Guerre mondiale au château de Chambord (Loir-et-Cher) en 1939, puis déplacé au château de Sourches, Saint-Symphorien (Sarthe), le 29 septembre 1943 ; rentré du château de Sourches au musée du Louvre, Paris, le 16 juin 1945 ; restauré par Raymond Lepage et Paul Maridat (rentoilage) et par Georges Zezzos (allègement et réintégration de la couche picturale), au musée du Louvre durant l'été 1949 ; présenté au musée du Louvre dans la salle Mollien d'octobre 1949 à 1969, puis en salle Daru de juin 1969 à juin 1994, puis en salle Mollien depuis décembre 1995 ; restauré par David Cueco et Claire Bergeaud (remplacement du châssis, pose de bandes de tension sur les bords de la toile) au musée du Louvre en janvier-février 1999 ; restauré par Bénédicte Trémolières et Laurence Mugniot (nettoyage et réintégration de la couche picturale) au musée du Louvre, d'octobre 2023 à avril 2024.

#Liberty Leading the People#Eugene Delacroix#Romanticism#1830#oil on canvas#painting#oil painting#The Louvre#Paris#France#Musée du Louvre#La Liberté guidant le peuple#french#art#artwork#art history

66 notes

·

View notes