#7th Century BCE

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Rhodian jug

* 7th / 6th century BCE

* British Museum

London, July 2022

162 notes

·

View notes

Text

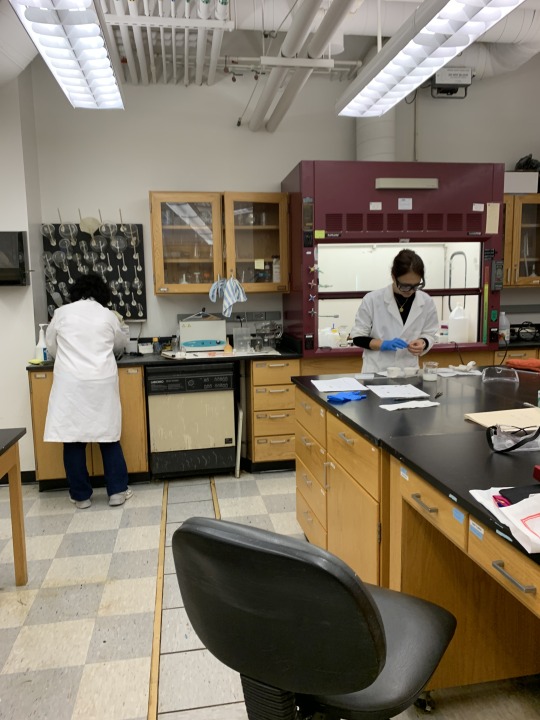

Interrupting our fan art parade to say: Ask me what I did today!

Alchemy. I’ve been doing alchemy.

#7th century BCE#cuneiform tablet#coloring silver gold#Hermes Trismagistus#Psuedo Democritus#Zosimus#Maddalena Rumor#Rekha Srinivasan#CWRU

79 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lakonian kylix featuring Prometheos and his friend, the Eagle.

The hair - facial and head - is so quintessentially Spartan, it’s not funny. And he has his braids in a braid, right? That’s what’s going on back there? Like a super-braid.

Saw this called a Spartan king somewhere along the way. Think that might be a bit of a push, but I do like the idea that some perioikic craftsman was like - ‘Y’know, if I could depict anyone having their liver pecked out on the daily, you know who I’d choose…’

Anyway - This is 7th Century Lakonianware (from before the great cultural shift).

#ancient sparta#ancient greece#lakedaimon#7th Century BCE#spartan hairstyles#sparta#ancient history#greek history#spartan history#ancient greek history#greek mythology#prometheus

309 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bronze hydria, Greek, late 7th - early 6th Century BCE

From the Met Museum

#bronze hydria#hydria#jar#water jar#greek#ancient greek#ancient greece#ancient#bronze#7th century bce#6th century bce#bce

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

Silver Mirror, 7th century BC

Kelermess Barrow, Transkuban

Silver

Diameter: 17 cm

Collection of the Hermitage Museum

Mirror with Scythian mistress of the animals, Griffins, Sphinxes, animals, and Arimaspians 7th C. BCE. This may have association with the Scythian deity Artimpasa, as she could be associated with animals, though the Potnia Theron figure has usually been associated with Artemis, from what I've seen. From the Kelermess Barrow. Hermitage Museum.

"Among these, the Tauri have the following customs; all ship-wrecked men, and any Greeks whom they take in their sea‑raiding, they sacrifice to the Virgin Goddess (Artemis) as I will show: after the first rites of sacrifice, they smite the victim on the head with a club; according to some, they then throw down the body from the cliff whereon their temple stands, and impale the head; others agree with this as to the head, but say that the body is buried, not thrown down from the cliff. This deity to whom they sacrifice is said by the Tauri themselves to be Agamemnon's daughter Iphigenia. As for the enemies whom they overcome, each man cuts off his enemy's head and carries it away to his house, where he impales it on a tall pole and sets it standing high above the dwelling, above the smoke-vent for the most part. These heads, they say, are set aloft to guard the whole house. The Tauri live by plundering and war."

-Herodotus, The Histories, Book 4.103

144 notes

·

View notes

Note

What's your PhD about?

I haven't started it yet cause I'm looking for funding first so this might change (also I've altered the PhD propossal depending on the professor that would be my supervisor) but basically I want to study the Muses through the lens of Cultural Memory.

The ideal thing would be to study them and their evolution throughout ancient Greece, but that's impossible so for example my current PhD director suggested I should focus on the Archaic Era (also the Dark Ages, so around the 10th to 6th centuries BCE more or less). I am very interested in the relationship between identity, literacy, and religiosity, so the Muses are perfect for it, as they were used by the Greeks as a sort of fact-check for aoidoi and poets, which were the preservers of Cultural Memory.

Most stuff that's been written about the Muses has always been very philological and especially related to the 'invocation of the Muses' so prevalent in Greek literature. I want to open the scope to new angles, something never done before, and I have experience working with Cultural Memory from my Master's Thesis, so I thought it would be a cool approach :) It's gonna be much more theoretical than you would expect, but I love that sorta thing. Also it's impossible to separate the Muses from literacy so I'll be looking at written sources for sure, my good pal Hesiod (whom my Undergrad Thesis was about) will occupy a good chunk of the research I'm afraid.

So yeah, that's it. This won't happen if I don't get funding tho, so I could just never write this Ph.D. Who knows.

#ask#sorry for the lengthy answer anon i've had to write so many phd proposals in the past few months i just go with the autopilot#i hope it's comprehensive enough. and please feel free to ask more questions!! i am very passionate about this so i would love#to answer more stuff like this :)#i'm currently researching my second master's thesis btw#it's gonna be about the cult of the muses in thespiai#so a bit of context#the heliconian muses (which are like the 'canon' muses; the ones described by hesiod) 'originated' around helicon mt#this is a real place in boeotia greece#the valley of this mountain is the valley of the muses. hesiod lived right there#in ascra.#ascra at some point was conquered by the city of thespiai. and it was part of it for the rest of ancient greece#(this happened very early on btw. like probably 8th or 7th century)#there was a sanctuary of the muses built in the vale#and this agonic competition (like a music festival) took place there called mouseia#it became incredibly important#but the thing is. this all happened in the hellenistic era (so 2nd - 1st centuries BCE)#there is barely any evidence of anything muses related in thespiai before that#noticeably it was in the hellenistic era when hesiod really became famous#so i want to study the evolution of the cult of the muses in thespiai; the evidence (or lack thereof) for it; and its instrumentalization#by thespiai#i'll mostly do it through epigraphy cause 1) it's the source i'm most comfortable with and 2) there's not really much else#i'll also sprinkle in cultural memory and some heavy theoretical stuff in there just for fun#so yeah i'm having fun with it :) hopefully i'll finish it by october!

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

“What is the difference between Orphic and Homeric Hymns?”

The Orphic and Homeric hymns are both significant in the context of ancient Greek literature and religion, but they differ in origin, purpose, and style.

1. Origin and Tradition:

- Homeric Hymns: These hymns are attributed to Homer, though they were likely composed by various poets in the 7th and 6th centuries BCE. They are part of the broader tradition of epic poetry and are generally seen as a way to honor the gods through narrative and invocation.

- Orphic Hymns: These hymns are tied to the Orphic tradition, which is associated with the mythical figure Orpheus. The Orphic hymns date from later periods (around the 3rd century BCE to the 3rd century CE) and reflect a more esoteric and philosophical approach to religion.

2. Content and Themes:

- Homeric Hymns: Each hymn typically praises a specific deity, recounting myths or stories related to their attributes, powers, and deeds. They often serve a liturgical purpose, meant to invoke the favour of the gods.

- Orphic Hymns: These often incorporate themes of mysticism, cosmology, and the soul's journey. They focus more on personal religious experience and metaphysical concepts, such as the nature of the divine and the afterlife.

3. Style and Structure:

- Homeric Hymns: They generally follow a narrative structure and employ traditional epic techniques, such as invocation and epithets. The language is grand and formal.

- Orphic Hymns: While also poetic, these hymns tend to use a more lyrical and mystical language, emphasizing philosophical ideas. The structure can be less consistent than that of the Homeric hymns.

While both types of hymns celebrate the gods, the Homeric hymns are more concerned with storytelling and invocation in a traditional epic style, whereas the Orphic hymns delve into mystical and philosophical themes, reflecting a different aspect of religious belief.

If I missed anything or messed anything up please let me know, I am up to hear about your opinions / knowledge on this too ^^

#hellenic pagan#hellenic polytheism#hellenic polythiest#hellenism#hellenistic#homeric hymns#orphic hymn#paganism

725 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Pomegranate Plague of Gen Z Poets

First, it was the moon. Then cigarettes. Then, girls by windows, ethereal in their ruin. Now? Pomegranates. (from my substack)

If you’ve spent enough time around poetry circles, you’ve seen it before. The doomed love, the Persephone complex, the vaguely sacrificial undertones. And, of course, the fruit.

The Persephone Myth (The Popular Version)

So you think you know the story: Persephone, wreathed in flowers, is stolen by Hades, dragged screaming into the Underworld. Her mother, Demeter, weeps and starves the earth in protest. Zeus, eventually deciding this is a problem, orders Persephone’s return—but oops, she ate six pomegranate seeds, so now she’s doomed forever.

That’s the version that survives in girl poetry, anyway.

What Promegerants Girls won’t tell you? The actual myth is a mess. There is no single, definitive version—just fragments, scraps stitched together across centuries. And the pomegranate seed detail?

It barely even shows up.

What We Actually Have:

• Persephone’s myth wasn’t even originally Greek. The story of a goddess being dragged into the underworld predates Greek mythology entirely.

• In Mesopotamian myth, Ishtar (Inanna) descends into the underworld to confront Ereshkigal, queen of the dead. She is stripped of her power and trapped, only escaping by offering someone else in her place—a theme that later appears in Persephone’s myth. This suggests Persephone’s story wasn’t a Greek invention but an adaptation of older Near Eastern fertility-death-rebirth cycles.

• Despoina (“the Mistress”) was worshipped before Persephone—and before Hades was even relevant. In older, pre-Olympian cult traditions, Despoina was the actual chthonic goddess of the underworld. She was venerated alongside Demeter and was probably a far more powerful, independent figure before later mythology reduced Persephone to “Hades’ wife.” Despoina’s cult was deliberately secretive, meaning much of her lore is lost—but she was deeply tied to the Eleusinian Mysteries, which were about life, death, and rebirth, not tragic romance.

• Hades wasn’t even a major figure in early versions of the myth. Before he was written in as “the husband,” the underworld was associated more with Gaia (Earth) and Nyx (Night). Hades’ later dominance in the story came as Olympian mythology reshaped older chthonic traditions.

• Persephone was originally Kore (“the Maiden”)—not a tragic heroine, but an archetype of the life-death-rebirth cycle tied to agriculture. She wasn’t a person; she was a function. The whole point was that she disappears, then re-emerges—her personality was secondary to the cosmic process she represented. Only much later did people start treating her as an individual.

• Hesiod’s Theogony (~8th century BCE), one of the oldest Greek texts, barely mentions Persephone. To him, she’s just Hades’ wife, no backstory necessary. This matters because it shows that her abduction wasn’t even a central myth at first—it developed later.

• The Homeric Hymn to Demeter (~7th century BCE) is our earliest and most detailed source. But forget romance—it’s a political nightmare. Hades kidnaps Persephone (the Greek verb used, ἁρπάζω, literally means “to snatch away”—no courtship, no tragic longing). Demeter shuts down the harvest, and Zeus steps in not out of fatherly love, but because no crops mean no sacrifices, and no sacrifices mean starving gods.

The pomegranate? One sentence. Persephone eats something in the Underworld, so she has to stay. That’s it. The number of seeds? Not even mentioned. The whole “I bit into a pomegranate and now I am bound to darkness forever ”dramatics? A complete invention.

• Ovid’s Metamorphoses (~8 CE) is where we finally get the six seeds detail—but Ovid was Roman, writing centuries after the Greek versions had already evolved. His retelling heightens the drama, turning Persephone into a tragic, doomed figure rather than a cosmic force tied to ritual.

• Later Orphic traditions tried to clean it up, recasting Persephone as the mother of Zagreus (a god later merged with Dionysus), tying her to death, rebirth, and mystery cults. At this point, the myth had already spiralled into layers of mysticism.

• Persephone wasn’t always tragic—she became terrifying. The helpless waif image is a modern fabrication. The ancient sources tell a different story—one where Persephone is feared, not mourned.

• In Euripides’ Helen (412 BCE), she is invoked as a vengeful queen of the dead.

• In Homer’s Odyssey (Book 10), Odysseus fears Persephone’s wrath during his necromantic ritual—she is powerful enough to control the dead without Hades.

• Hecate was Persephone’s underworld counterpart and guide. In later versions, Hecate leads Persephone back to the upper world, further reinforcing Hecate’s enduring role in the chthonic realm.

• In Roman tradition, Proserpina (Persephone) was linked to Libera, a goddess of wild fertility and ecstatic rites. This completely contradicts the modern image of her as a fragile, tragic figure.

The Pomegranate Wasn’t Inherently Tragic

• In Hippocratic medical texts, pomegranate juice was used for contraception and abortion remedies—a practical, everyday association, not one of doom.

• In Pliny the Elder’s Natural History (1st century CE), pomegranates were used to treat fevers and digestive issues. No poetic suffering, just ancient medicine.

• In Greek funerary practices, pomegranates symbolised rebirth, not entrapment. They weren’t about being bound to darkness forever—they were about the cycle of life continuing.

Why This Completely Destroys the Promegerants Version of Persephone

1. The myth is about agriculture and divine power, not doomed love. The earliest versions barely mention Hades—this was Demeter’s story, a myth about the life cycle, cosmic balance, and the survival of humanity.

2. Persephone wasn’t always Persephone. She was Kore, an agricultural symbol, not a tragic heroine. Her function came first, her personality second. The idea of her as a fully realised, suffering individual came centuries later.

3. She wasn’t even the first queen of the underworld. Despoina was worshipped before her—an older, more powerful chthonic goddess with nothing to do with victimhood or romance.

4. The pomegranate was never central to the original myth. It’s a tiny, passing detail used as an explanation for why Persephone had to stay in the Underworld. The number of seeds? A Roman invention.

5. The whole myth wasn’t even Greek to begin with. It likely evolved from Mesopotamian myths like Ishtar’s descent, meaning the Promegerants version is a distortion of a distortion.

6. Persephone wasn’t a victim—she was a force of nature. The later versions of her myth don’t show her as tragic—they show her as terrifying. She was a queen who ruled the dead, feared even by heroes. If Promegerants Girls really wanted to stay true to the myth, they wouldn’t write about Persephone tragically eating seeds—they’d write about her punishing mortals for disturbing the dead.

From Chthonic Queen to Tragic Girlcore

The Promegerants version of Persephone strips her of her original role and reduces her to an aesthetic prop. In the oldest sources, she isn’t even a person—she’s a cosmic force, an idea before she’s a character.

Persephone was never just a tragic girl in a dark room with red-stained lips. She was a goddess of cycles, a ritual figure whose presence dictated the survival of humanity. The oldest myths barely even cared about her personal emotions—because that wasn’t the point.

And the pomegranate? Once a symbol of fertility and power, now just a moody Tumblr metaphor for doomed relationships. Would the ancient Greeks recognize Promegerants Persephone?

Absolutely not.

They’d probably assume she was some mediocre Roman poet’s overdramatic rewrite.

In other words: the version we cling to is a late, Romanized, overly romanticised distortion of a much darker and weirder myth—one that was never about love, tragedy, or women choosing their suffering.

Why Has This Myth Been Hijacked?

Because it’s too easy. The modern interpretation lets poets turn Persephone into:

• A stolen innocence narrative—without engaging with its actual horror.

• A tragic queen figure—without ever giving her power.

• A martyr for womanhood—as if eating a fruit were some grand metaphor for the inevitability of suffering.

But Persephone’s story was never about being loved and ruined.

It was about bargaining, power, and gods who don’t care about human grief.

The Pomegranate Problem™

At this point, the pomegranate isn’t a symbol—it’s a decorative prop.

Its original meanings—fertility, power, the tension between life and death—have been stripped away, replaced with moody girlhood aesthetics.

Poets don’t use it because they understand its history. They use it because it sounds expensive—like a fruit for people who romanticise heartbreak in foreign cities.

But if your poem still works after swapping “pomegranate” for “grapes”, then what are we even doing here?

Read This Before You Write Another Pomegranate Poem

• Homer’s Odyssey → Pomegranates appear in King Alcinous’ eternal orchard, a symbol of wealth, abundance, and divine favour. Not doom.

• Euripides’ Ion → Associated with Aphrodite, symbolising fertility, passion, and desire. Again—not doom.

• Aristophanes’ Lysistrata → Used as an innuendo for female sexuality (which, frankly, would make for a far more interesting poem).

• Dionysian Mysteries → Linked to ecstatic rites, resurrection cults, and the cycle of life and death. If you want to write about pomegranates and darkness, this would actually make sense.

• Roman Religion → Sacred to Juno, particularly in marriage and childbirth rituals, reinforcing their connection to fertility and renewal, not suffering.

• Theophrastus’ Enquiry into Plants → Describes pomegranates as a cultivated luxury fruit, prized for its sweetness, medicinal properties, and status.

• Herodotus’ Histories → Mentions Persian warriors decorating their spears with pomegranates, symbolising strength, fertility, and victory.

• Pausanias’ Description of Greece → Describes pomegranate offerings at Demeter’s sanctuaries, representing fertility, rebirth, and ritual purification—never suffering.

• Plutarch’s Moralia → Links pomegranates to beauty, sensuality, and indulgence in Greek and Roman culture—so, more hedonistic pleasure, less tragic metaphor.

Next time someone writes about a pomegranate-stained mouth, ask them if they mean Persephone or Aristophanes’ sex jokes.

How to Write a Pomegranate Poem That Survives Scrutiny

If you must use it, at least be rigorous. If you’re going full Persephone-core, then be specific. Make it about something real.

Tell us if the juice stains the sheets, if the seeds taste like metal, if they stick between your teeth like regret.

Don’t just drop in “pomegranate” and expect us to do the heavy lifting.

Or consider letting the myth go.

There are so many other symbols, so many richer, underused classical references.

And If You’re Tired of the Pomegranate, Try These Instead

there’s a whole world of classical symbols that carry just as much weight—without the overuse. Here are a few:

Chthonic & Underworld Imagery:

• Asphodel – The ghostly, liminal flowers of the underworld in Greek myth, growing where souls linger. Less overdone than pomegranates, just as eerie.

• Lethe – The river of forgetfulness. Its waters erase memory, a far more unsettling metaphor for loss than a single piece of fruit.

• Orphic Gold Leaves ��� Real funeral tablets placed with the dead, inscribed with guidance for navigating the afterlife. The ultimate memento mori.

• Owls – Athena’s symbol, but also a nocturnal watcher associated with wisdom, death, and the unknown.

Fertility, Desire & Ruin:

• Fig Trees – Symbolizing sensuality, abundance, and decay (the Greeks also had fig-wood coffins).

• Laurel Wreaths – Victory and poetic ambition, but also a crown of temporary glory—since laurel leaves wither fast.

• Myrrh – A resin used for perfume and burial rites, evoking both seduction and decay. (Also linked to Myrrha, who was cursed to fall in love with her own father. Greek myths were wild.)

Dionysian Madness & Ecstasy:

• Thyrsus – A staff tipped with ivy and pinecones, wielded by Dionysus and his followers. Represents intoxication, divine frenzy, and the thin line between revelry and destruction.

• Ivy – Unlike flowers, it never dies in winter. Clings, suffocates, overtakes. A more interesting metaphor for entanglement than Persephone’s six seeds.

If you must use a pomegranate, at least make it bleed. But if you’re ready for something richer—there are so many other symbols waiting.

#malusokay#girlblogging#persephone#pomegranate#poetry#poets on tumblr#writers and poets#poems#poems and poetry#female writers#writing#writers on tumblr#writeblr#writerscommunity#substack#essay#personal essay#essay writing#classic academia#student#classics major#classics#classical literature#classic literature#ancient greek#classical studies#ancient greece#mythology#greek mythology#academia aesthetic

205 notes

·

View notes

Text

I keep seeing a post going around saying that people should stop using the “colonized” names for cities in Israel/Palestine and should instead use the Arabic names.

I need you guys to be so for real right now, Hebrew is quite literally the indigenous language of the area. Like believe what you want about Israel, but Hebrew objectively and factually originated in that land. The earliest record of written Hebrew is the Khirbet Qeiyafa inscription, found near Beit Shemesh which dates back to the 11th-10th century BCE.

The first record of the name Jerusalem is in the Egyptian Execration Texts which date back to the 20th century BCE.

Arabic was introduced to the land in the 7th century CE. The first recorded use of “Al-Quds” was in the 9th century CE.

I could do this for every single ancient city in the land. Bethlehem, Hebron, Jericho, Jaffa, Beer Sheva, Acre, and Ashkelon all existed prior to the Arab conquests in the 7th century CE and the introduction of Arabic to the land.

The fact that we use the Hebrew names of these cities isn’t some conspiracy to make them sound “more Jewish”, the modern Hebrew names are direct descendants of the ancient Canaanite words for these places. Hebrew is the only surviving Canaanite language.

Believe what you want about Israel, but claiming that the Hebrew names for these cities are “colonial” names is a disgusting erasure of Jewish history in the land.

#israel#jews#jewish#hebrew#arabic#israel palestine conflict#palestine#I have a feeling I’m gonna get hate for this but honestly I had to say something#y’all are willingly spreading pan-Arabist propaganda

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Vase detail

* Rhodes

* 7th / 6th century BCE

* British Museum

London, July 2022

87 notes

·

View notes

Text

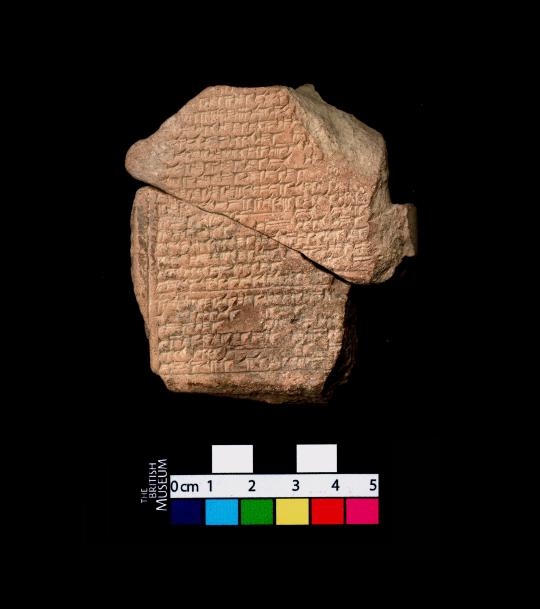

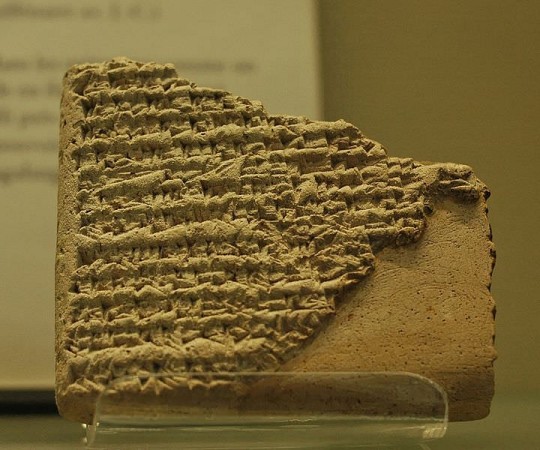

So, last November I got to try my hand at Alchemy

Maddalena Rumor, in the Classics Department of Case Western Reserve University came to have dinner with us and mentioned she'd just successfully turned silver gold.

She had an alchemical recipe from a 7th century BCE cuneiform tablet from the library of Ashurbanipal. She'd been working with Rekha Srinivasan, from the Chemistry Department to see if they could translate the cuneiform, identify the substances mentioned, and then try the recipe to see if it worked.

They traveled to the British Museum to examine the tablet up close. By studying the partial strokes along the edges, Maddalena could make some educated guesses about missing words. Rekha, in turn, could use the descriptions of the substances to make some guesses about what they might be. Then they could start testing their best guesses with experiments.

This is complicated by the tendency of alchemical texts to use code words or inside jokes to describe materials or techniques. Something like me making a recipe that calls for 2 Legs and 1 Arm of Policeman and my friends all knowing it means 2.5 ingots of Copper.

I know the word alchemy comes from the Arabic al-kimia and that it eventually developed into chemistry, but I've always associated it with the worst of the Dark Ages in Europe--charlatans or wannabe magicians in smoke-filled, poorly lit cellars full of of mummified animals and just generally gross stuff that is not my jam.

I'm wondering now if that's because medieval alchemists were reading a lot of things literally that weren't meant to be taken that way. There's a reference in one of Maddalena's article's to a rare case where "human excrement" called for in a recipe is revealed to actually mean "garlic." I can see a lot of ancient alchemists laughing up their sleeves.

I had just learned during a trip to Naples the previous summer that the alchemy of Renaissance philosophers like Pico Della Mirandola was very different from the stuff in the basements of Prague. Instead of dreckapotheke, they were translating texts from the Ancients Greeks, texts that were perhaps based on the very tablets from the 7th Century BCE that Maddalena was studying. I promptly begged to observe her next experiment.

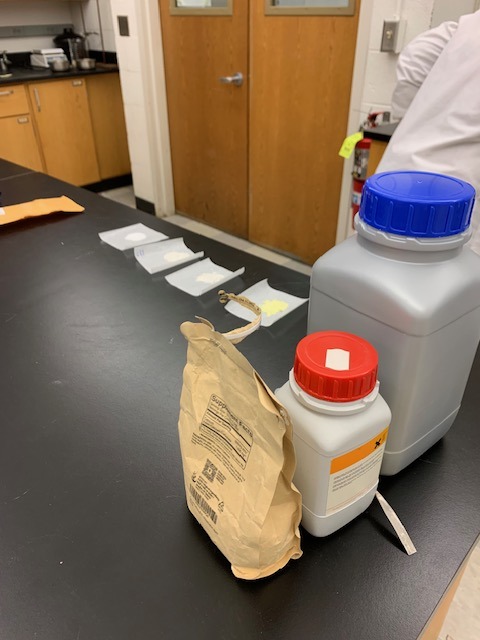

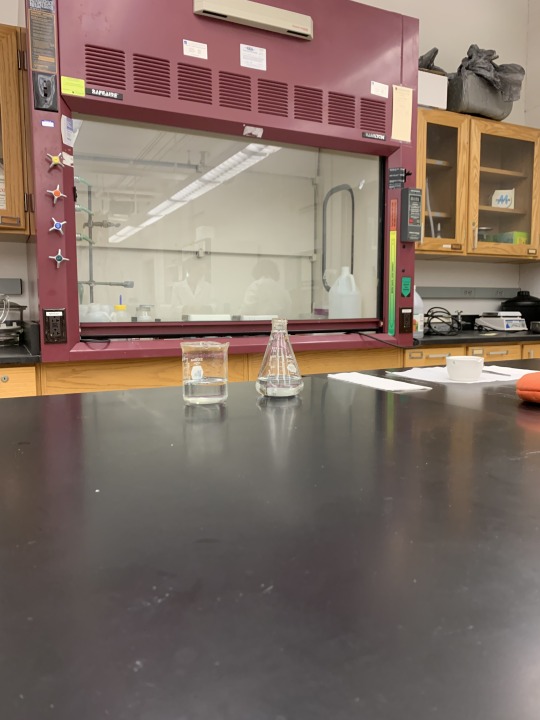

She very graciously said yes, so I went down to a lab at Case and I wish I had taken better notes, but I did not, so what I've got is a bunch of pictures, and I'll have to go back and badger Maddalena for details.

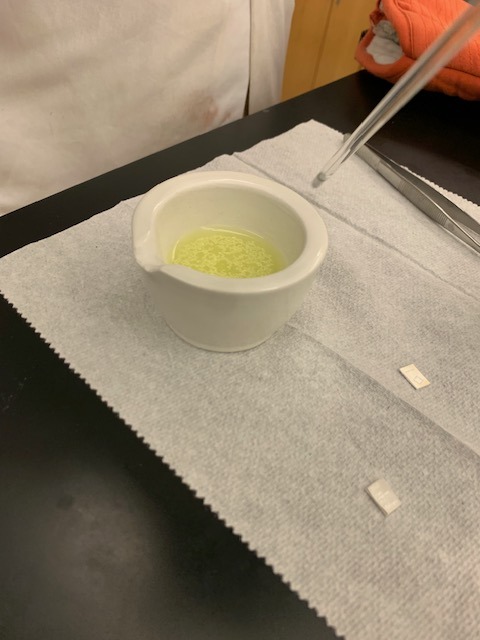

These are the ingredients for the next round of testing.

They will be mixed into a solution in the flask on the right and then heated on a burner.

Then silver tablets will be dipped into the solution:

And turn gold!

Not *into* gold. That was not the plan. Hope you aren't disappointed.

If you thought the object of alchemy in those dark basements in Prague was turn to lead into gold, yeah me, too. And maybe it was, but the alchemy of the ancient Near East seems to have been more clear that transmutation wasn't on offer. After reading some of Maddalena's articles, I now know there were four main practices of alchemy back in the day: coloring silver gold, making a silver alloy that still looked like silver, coloring glass to look like precious stones, and dying wool purple without using those expensive snail shells from Tyre.

I talked about alchemy a lot (really, a lot, everyone was very patient) at a recent writing retreat. Erin Bow called it the Science of Knock Offs.

There are multiple ancient sources that say that this "holy and divine art" (hē hiera kai theia technē) was taught to mankind by fallen angels who were sharing the secrets of heaven. I know it seems ridiculous that an all knowing divine being is going to focus on the Secret Science of Knock Offs, but the more I I think about it, the more I can see it.

ARMUMAHEL: We will share with you the great mysteries of heaven!

MANKIND: . . .

ARMUMAHEL: I can save you some money on purple dye.

MANKIND: YAY!

SAMYAZA: So how did the secret sharing go today, Armumahel? Did they ask about the language of birds? The control over monsters of the deep?

ARMUMAHEL: I told'em how to make glass marbles look like sapphires.

SAMYAZA: You do know Enoch is writing all this down. His book is going to be stuck in the apocrypha and we're going to be laughing stocks.

ARMUMAHEL: I promised to tell them tomorrow how to turn silver gold.

SAMYAZA: Ah! Transmutation of matter! That's a good one!

ARMUMAHEL: No, not transmutation. They just want the silver bowls on the alter to be yellow and shiny.

SAMYAZA: . . .

My shiny yellow tablet. : )

225 notes

·

View notes

Text

Some Art Vocabulary

Abstract - Simplified, intended to capture an aspect or essence of an object or idea rather than to represent reality.

Amber - Tree resin that has become a fossil. It is semi-transparent and gem-like. Amber is used in jewelry today as it has been for thousands of years.

Amulet - Object, organic or inorganic, believed to provide protection and turn away bad luck. Amulets were often worn as jewelry in antiquity.

Anneal - To heat metal to make it soft and pliable.

Black-figure - Technique of vase painting developed in Greece in the 7th and 6th centuries BCE and adopted by the Etruscans. Figures are painted on a reddish clay vase in black silhouette and details are then cut away with a sharp point down to the red below. Sometimes artists added additional colors, especially purple-red and white.

Bronze Disease - Corrosion of a bronze object that cannot be permanently stabilized. Without special care, an object with bronze disease will continue to corrode.

Bust - Portrait of a person including the head and neck, and sometimes the shoulders and part of the chest.

Cameo Glass - Glass produced by layering two or more colors of glass. Generally, an upper layer of white stood out against a contrasting lower background, usually blue.

Cameo Stone - Hard stone, such as agate, naturally layered with bands of color. Artists took advantage of the layers to carve figures or decoration from an upper layer (or more than one), leaving a background layer of a different color.

Cast - To make in a mold from liquid metal. A cast object can be hollow or solid.

Chasing - Technique of adding definition and details to an image or design on metal from the front using blunt and sharp tools.

Conservator (of antiquities) - Professional responsible for preserving ancient objects and materials. Conservators usually have a general knowledge of chemistry and of ancient art-making practices and are often specialists in one material. Among many other responsibilities, they conduct technical and historical research and oversee preventive care such as climate control.

Contrapposto - (”opposite” in Italian) Pose of a standing figure with most of the weight on one leg and the other bent. This causes hips, shoulders, and head to shift in order to balance the body. One arm is often higher and one lower.

Emery - Hard, dense rock rich in corundum, found easily on the Cycladic Islands. A powerful abrasive for grinding and smoothing other stones.

Encaustic - Technique of painting using colored pigments mixed with wax. The waxy mixture was worked with a tiny spatula.

Gild - To apply a thin layer of gold foil or liquid gold (gilt) to create the look of solid gold.

Iconography - Study of and use in art of repeated images with symbolic meaning.

Incise - To press or cut into a surface (stone, metal, clay, wood) with a sharp tool to write text or create fine curving and linear details.

Inlay - To decorate an object by inserting a piece of another material into it so that it is even with the original surface.

Low Relief - Method of carving figures or designs into a surface so that they are raised slightly above a flat background.

Mosaic - Technique and type of artwork. The technique is to arrange cubes of stone, glass, and ceramic to form patterns and pictures in cement, usually on a floor. The artwork is the final story or decoration made of cubes.

Mummification - Process of preserving a body by drying it. The Egyptians removed internal organs and put natron, a natural mineral mixture, on and inside the body. This absorbed moisture and prevented decay.

Palmette - Stylized palm leaf used as decoration in ancient Greek and Roman art and architecture.

Pentelic - From Mount Pentelicus, near Athens. An adjective that mostly refers to the beautiful white Greek marble marble in its quarries.

Portrait - Image of a person, usually the head and face. Some portraits include part of the chest or show the whole body. The image may closely resemble a person or emphasize, idealize, or invent characteristics.

Repoussé - Technique of raising the outline of a design on metal by repeatedly heating and softening the metal and pushing the desired shapes into it from the back with a blunt tool.

Sarcophagus/Sarcophagi (pl) - Stone coffin, often decorated on the sides with mythological scenes carved in relief, sometimes with the image of the deceased person or couple on the lid. Used in Imperial Roman times from the early 100s into the 400s CE.

Stele/Stelai (pl) - Upright stone or wooden slab or pillar used to honor a person or mark a place. Often an inscribed grave marker or a boundary stone. (Also called stela/stelae.)

Syncretism - Blending of elements of different cultures, often resulting in new imagery or new interpretations.

Tessera/tesserae (pl) - Pieces of stone or other hard materials cut into squares or cubes to make mosaic art.

More: Word Lists ⚜ pt. 2

#art#terminology#word list#writeblr#dark academia#writing reference#spilled ink#literature#writers on tumblr#writing prompt#poetry#poets on tumblr#writing inspiration#creative writing#light academia#langblr#linguistics#jan matejko#romanticism#art vocab#writing resources

264 notes

·

View notes

Text

a judean seal, most likely belonging to a high-ranking archer, from the 7th century bce. the assyrian-influnced style of the seal is very apparent. the text reads "𐤓𐤂𐤇" (hagab), the name of its owner. the paleo-hebrew letters are mirrored.

155 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Legend of Sargon of Akkad

The Legend of Sargon of Akkad (c. 2300 BCE) is an Akkadian work from Mesopotamia understood as the autobiography of Sargon of Akkad (Sargon the Great, r. 2334-2279 BCE), founder of the Akkadian Empire. The earliest copy is dated to the 7th century BCE and was found in the ruins of the Library of Ashurbanipal in the 19th century.

The text, most likely composed c. 2300 BCE, and also known as The Birth Legend of Sargon, describes the king's humble origins and rise to power with the help of the goddess Ishtar and concludes with a challenge to future kings to go where he has gone and do as he has done. Sargon was the founder of the first multinational empire in the world whose reign became legendary, inspiring many tales about him, but very little is known of his life apart from works such as The Legend of Sargon of Akkad and the literary piece Sargon and Ur-Zababa.

Both pieces today are sometimes classified as belonging to the genre of Mesopotamian naru literature – the world's first historical fiction – in which a famous figure, usually a king, is featured as the main character in a fictional work. This genre appeared around the 2nd millennium BCE and was quite popular, as evidenced by the number of copies found of naru works.

The purpose of naru literature was not to deceive an audience but to impress upon them some important religious or cultural value. In the case of The Legend of Sargon of Akkad, however, the naru genre seems to have been used to establish Sargon as a 'man of the people' who, beginning life as an orphan with nothing, forged his own destiny and established an empire.

The Legend & Naru Literature

Sargon of Akkad was keenly aware of his times and the people he would rule over. He seems to have understood, early on, that the common people resented the nobility and, while he was clearly a brilliant military leader, it was the story he told of his youth and rise to power that exerted a powerful influence over the Sumerians he sought to conquer.

Instead of representing himself as a man chosen by the gods to rule, he presented a more modest image of himself as an orphan set adrift in life who was taken in by a kind gardener and granted the love of the goddess Inanna/Ishtar. According to The Legend of Sargon of Akkad, he was born the illegitimate son of a "changeling", which could refer to a temple priestess of Ishtar (whose clergy were androgynous) and never knew his father.

His mother could not reveal her pregnancy or keep the child, and so she placed him in a basket which she then set adrift on the Euphrates River. She had sealed the basket with tar, and the water carried him safely to where he was later found by a man named Akki, a gardener for Ur-Zababa, the king of the Sumerian city of Kish. In creating this legend, Sargon carefully distanced himself from the kings of the past (who claimed divine right) and aligned himself with the common people of the region rather than the ruling elite.

The Legend, as noted, is considered by some scholars today as belonging to the genre of Mesopotamian naru literature, but it is unknown whether it would have been understood that way in its time. Scholar O. R. Gurney defines the genre and its origin:

A naru was an engraved stele, on which a king would record the events of his reign; the characteristic features of such an inscription are a formal self-introduction of the writer by his name and titles, a narrative in the first person, and an epilogue usually consisting of curses upon any person who might in the future deface the monument and blessings upon those who should honour it. The so-called "naru literature" consists of a small group of apocryphal naru-inscriptions, composed probably in the early second millennium B.C., but in the name of famous kings of a bygone age. A well-known example is the Legend of Sargon of Akkad. In these works, the form of the naru is retained, but the matter is legendary or even fictitious. (93)

The extant copy, made long after Sargon's death, conveys the story Sargon would have presented regarding his birth, upbringing, and reign. Naru pieces such as The Legend of Cutha or The Curse of Agade use a well-known historical figure (in both these cases Naram-Sin, Sargon's grandson) to make a point concerning the proper relationship between a human being (especially a king) and the gods. Other naru literature, such as The Great Revolt and The Legend of Sargon of Akkad, tell a tale of a great king's military victory or origin. In Sargon's case, it would have been to his benefit, as an aspiring conqueror and empire builder, to claim for himself a humble birth and modest upbringing.

Continue reading...

145 notes

·

View notes

Text

let it also be that i introduced some fourth to sixth graders to the concept of religions not dependent on christianity lmao

if i did anything at all during my community service let it be that i taught some children that people in ancient times were not idiots for not having "scientific" explanations for things

#one of them asked me if jesus would come Before the primordial chaos and i just kinda 🧍#“uh. no. they didn't have christianity in the 7th century bce when hesiod wrote the theogony”#one of the fourth graders was like I AM GOING TO MAKE A KAHOOT FOR YOU ABOUT THE BIBLE#and i just 🧍 little man i only know the iliad what are you talking about#he said his parents wouldn't let him make the kahoot because i was too old 😭#his parents thought i was some middle aged teacher 😭#uni posting#pia.txt

1 note

·

View note

Text

Odysseus to Poseidon, 8th-7th century BCE

#odysseus#the odyssey#homer#poseidon#greek mythology#ancient greece#epic the musical#epic the ocean saga#digital art#tee's art#epic odysseus#epic the musical fanart

191 notes

·

View notes