Film reviews written by a part-time filmmaker and full-time millennial.

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Photo

Guillermo del Toro's newly released but repeatedly praised The Shape of Water (2017) is a classic love story. As classic as love stories between a water creature and a cleaning lady at a top secret research facility can be. The cleaning lady in question, portrayed by Sally Hawkins (Blue Jasmine, Happy Go Lucky), is introduced as a calm, but intriguing character, who enjoys routine and silence. The first motivated by free will, the second not so much, since Elisa Esposito is a mute. She finds her opposite in loud-mouthed Octavia Spencer (The Help) portraying Elisa's colleague and friend Zelda Fuller, who, despite (or because of) her lousy marriage, helps Elisa pursue an unworldly love. Elisa's next door neighbour, Giles, spends his days painting obsolete pudding adverts and stalking a guy serving terrible-tasting pie in a shop nearby.

This whole “a mute and her two companions”-setup becomes clear quite quickly in the beginning, and somehow the narrative stays this straightforward until the end, considering the only two other major characters introduced are two monsters. One is an actual monster-like creature, labeled by the lab as ‘the Asset’, who Elisa takes a liking to immediately, and the other, mister Strickland, is a cruel United States Colonel who has been assigned to interview (i.e. torture) it. As Elisa struggles to save her amphibian lover from the evil Strickland, the audience is spoon-fed a pre-chewed tale of love in adversity right up until the film's unsurprising but satisfying happy ending.

As stereotypically straightforward as the outline of this film might be, it should not be overlooked simply because of the ease with which it can be categorised as a fairytale. This film is as much a direct result of and reaction to Trump's presidency and similar prejudice-inducing situations currently dominating the societal landscape as much as Jordan Peele's political comedy horror Get Out (2017) is. Del Toro reminisces to better times and shapes the magic of his cinema back into its primary form, which was a way for audiences to escape reality. When the world was aching with World War II, the gaping wound was seemingly filled with hopelessly romantic motion pictures like Casablanca (1942). Before that, the invention of the Magic Lantern in the 19th century met people's hunger for travel when they were to poor to actually physically travel by showing slides of far away places. Similarly, now, Del Toro seems to have carefully mapped out his audience's deepest fears and desires and consequently calms/satisfies all of them by creating a magical fairytale of hope and romance- things that seem exponentially harder to find in the real world.

With The Shape of Water, Del Toro resembles a proud mum waving her daughter's report card in the air: if the daughter is the art of film then the report card features all the wonderful motion pictures that have been produced in a little over a hundred years. In subtle and not so subtle ways, the famous director alludes to and incorporates classic Hollywood musicals like The Little Colonel (1935) and Coney Island (1943), which gives not only the film a tender, rhythmic kindness, but Elisa, too.

Elisa is mute, yes, but she is not silent, which is one of the traits that makes her so likeable and, more importantly, watchable. Sally Hawkins manages to convey a fragile strength, or a strong fragility, (dependent which way you want to look at it) and it is exactly this duality which glues the narrative together: however cliché or self-glorifying the film gets, we still want Elisa to get her happy ending. This combined with Del Toro's attention to detail - each shot is carefully composed, framed and polished, with art design and VFX that makes any film fanatic jubilate with delight – makes The Shape of Water a fairytale worth watching, even if only to enjoy two hours of ignorant bliss away from reality.

#the shape of water#guillermo del toro#sally hawkins#octavia spencer#michael shannon#academy awards#film#film review#script#scriptwriting#review#screenwriting#motion picture#oscars#trump#hollywood#cinematography#art design#production design#del toro#filmmaking

12 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

All eyes are on Greta Gerwig strutting into the great wide open field that is Hollywood’s male-dominated landscape of directors, as she bravely births her directorial debut Lady Bird (2017). In many ways, this film is a prequel to Gerwig’s earlier Frances Ha (2012), a story of a semi-aimless twenty-something-year old living in NYC, with which Gerwig already proved to have a tight grip on reality and an even better (read: critical) understanding of her generation. Lady Bird can be described as a coming-of-age ‘chick flick’ in the mere definition that it features a girl; Christine “Lady Bird” McPherson; and that she is literally, with all that this would entail in suburban Sacramento in 2002, ‘coming of age’. The film carefully displays Lady Bird’s everyday life at her Catholic high school (a school she had to go to because her brother saw someone knifed at the town’s public school), her relationship with her family and best friend Julie, as well as her newly found interest in boys.

With a slightly unoriginal logline like that, there is no point in denying Lady Bird’s similarities to predecessors like The Edge of Seventeen (2016), Angus, Thongs and Perfect Snogging (2008), or even chick flick prototype Pretty in Pink (1986). However, it is in its subtle but brilliant discrepancies and deviations from said archetypal narratives that Lady Bird gains its crucial significance in today’s cinema. Modern Hollywood is hungry for versatile female characters. For too long we have been looking at singular women on the big screen: brilliant women, sexy women, caring women, angry women, yes, but never were all of those things depicted in one particular female character, even though we (i.e. those of us fortunate enough) have grown up knowing at least one woman encompassing several (if not all) of those traits: our mothers. ‘Who teaches you what it means to be a woman if not your mother?’ seems to be one of the questions Gerwig raises in her directorial debut. And through Lady Bird’s persistent denial of that maternal significance as well as some brutally truthful dialogue, the film starts to raise above its genre, in the sense that it asks the more overarching question of who we love, who we are loved by and if we let them.

With Lady Bird, it is as if Gerwig took one look at Hollywood’s habitual lack of versatile female characters, ripped it out like an old oak tree and started re-growing it from the roots up (its roots being the coming of age genre). If the so often unsurprisingly one-dimensional, male-focused coming of age-girls are what we reap, then how did we expect to sow anything other than flat, perfunctory roles for women? By showing both Lady Bird and her mother (brilliantly portrayed by Laurie Metcalf) in all their ‘glory’ as well as their ‘un-glory’, Gerwig refuses defining women by what they aren’t, but finally defines women by what they are: diverse, indestructibly adaptable yet wholesomely fierce human beings, especially in the case of Gerwig’s leading ladies.

Anyone walking out of the cinema thinking ‘what a sketchy film’ is a petty piece of shit, yet, also, very right. The film is defined by its flaky-ness, by its diversity of events, by the multitude of information readable between the lines of unprecedentedly brilliant dialogue. In a sense, one could say the brilliance of Gerwig’s direction is that it almost seems as if there is no direction. Each scene is a piece of wood in her seemingly erratically constructed game of Jenga, inclined to collapse at any moment, and yet it is this life-like sense of authentic chaos that makes Lady Bird such a brilliant piece of filmmaking. There is no pretense of “one thing” or “one goal” tying all events in the film together, other than that it’s one family trying to deal with several things thrown at them, resulting in this beautifully unintentional representation of a multitude of families across the globe, beautifully brought to life by the explosive performances by and chemistry between daughter Ronan and mother Metcalf (who will hopefully reap what they sow at the Academy Awards next month).

If you only see one coming-of-age drama with a female protagonist ever, please see this one as it features an actual girl, with all that this entails, and subtly but skilfully ushers in a new era for flourishing female characters.

#lady bird#greta gerwig#saoirse ronan#laurie metcalf#filmmaking#Film Review#academy awards#female filmmakers#female director#golden globes#golden globe winner#scriptwriting#screenwriting#cinematography#35 mm film#coming of age#chick flick#cinema#film#review#feminism#female characters#hollywood

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Judging by its trailer, Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri (2017) is a comedy about an angry lady in a small American village who puts up billboards after her daughter’s rapist and murderer is still roaming the streets seven months after the fact. Surely that, plus the lady in question being Frances McDormand (Fargo, Moonrise Kingdom), is enough to get people to the cinema, but what they will eventually stay seated for is so much more. Unsurprisingly for any film by Martin McDonagh, who also writes plays and prefers to call himself a writer rather than a director, Three Billboards is hard to categorise and is mainly, with its dark comedic as well as dramatic elements, a painfully truthful portraiture of people and their good intended wrongdoings.

The film hits the ground running, with Mildred Hayes, recently divorced and mother of remaining son Robbie, paying for three billboards to be decorated with caps locked outcries of pure rage. In a matter of moments, the whole town of Ebbing, Missouri is in an uproar against her to take them back down. Chief Willoughby (Woody Harrelson), the one who Mildred holds personally responsible for the lack of arrests, is quickly revealed to not only be pushing a frog-filled wheel barrel for a police department but is also in his final stages of battling cancer. So when fuming Mildred suggests him taking DNA off every man in the US in case they ever commit any kind of crime, the audience is left to question who to empathise with. When Dixon, a right-wing racist yet seemingly harmless police officer, enters stage, an interesting dynamic of contrasting characters establishes itself almost naturally.

The reason this film works so well; the reason any film works, really; is because all of its elements seem to be effortlessly intertwined and working together as a whole. McDonagh wrote the script in five weeks and introduces his characters as people who have lived before and will live on after the film ends, which makes them tangibly human. Just like real people, their tendency is to not be one thing alone, not just angry, not just scared, least of all perfect, which made them a challenging treat for this carefully (and brilliantly) selected cast to sink their teeth into. Instead of becoming a feature length-episode of a crime drama, Three Billboards manages to stack layer upon emotional layer yet also digs all the way to the depth of (Mildred’s) sorrow. What it finds there, the audience is left to decide for themselves, just like we ourselves must decide how to respond to any totally unpredictable turn of events life throws at us, like the rape and murder of your own daughter or a terminal diagnosis of cancer.

In a world of hashtags and headlines, this film is a breath of fresh, nuanced air. It is as if McDonagh created Mildred, whom we instantaneously empathise with over the loss of her daughter, and subsequently started dissecting her piece by piece. So much so until the viewer is confronted with something we, with all its Thors and Wonder Women, have forgotten in the cinema, but cannot seem to forget in real life: there are no heroes here, nor any true ‘enemies’. Mildred is angry so she doesn’t have to be sad, Willoughby is practical so he doesn’t have to be scared, Dixon is racist so he doesn’t have to feel guilty. Each character has reasons for doing things, whether those things end up being good or bad things, which leads to the most interesting question of this film: who do we root for? When you think about it, which McDonagh most definitely forces you to do, in this life of endless complexity and diversity, there’s a little bit of hero and enemy in all of us. Maybe even in rapists (although let’s not go there), but surely definitely in these characters McDonagh so creatively displays...

Psychological analyses aside, fortunately, if you do decide to judge Three Billboards by its trailer and expect a funny film about a lady throwing molotov cocktails, you will still not be disappointed. The film’s dialogues are brilliant, its cast even more so and it contains violence, arson, a cathartic Catholic Church rant and even a little person to ridicule, in case you really find it too hard to, well, feel something.

#three billboards outside ebbing missouri#three billboards review#frances mcdormand#martin mcdonagh#sam rockwell#woody harrelson#lucas hedges#abbie cornish#film review#filmmaking#screenwriting#scriptwriting#academy awards#golden globe winner#golden globes#film#review

28 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

There’s only so much one can say about this film: watching it kind of says it all. The soul of Edgar Wright’s Baby Driver (2017) lives in its rhythm, its energy and its carefully composed mise-en-scène. Right from the off, getaway driver Baby, portrayed by Ansel Elgort (The Fault in Our Stars, Divergent), grasps the attention of the audience by being stoically silent in a background of chaotic volume and reckless speed. A car accident when he was younger robbed him of his parents as well as most of his hearing capabilities, which explains Baby’s constant listening to music from one of his many retro iPods.

The film is quick on its feet and, as this post explains, its climaxes and explosions time perfectly with certain beats and drops in its soundtrack, to the point where it balances on artificiality. Just like Baby has an obsessive need to time the getaways precisely with its selected song, Baby Driver succeeds in doing the same. Shots are fired on specific beats, explosions happen on certain drops, creating an overall rhythm as if Baby and his colleagues are ‘living’ the music. This artificiality is carried on throughout the film, not just in its pacing, but also in its production and art design. Especially when Baby meets beautiful Debora in the diner where his mother used to work, popping colours are used as well as a glowing angel-like grade, mimicking those first days of blissful ignorant amorousness.

This film is about crime, yes, and is packed with car chases, definitely, but one of the things that makes Baby Driver stand out as a piece of cinema, is its power to place its viewer in Baby’s world. More specifically, his audible world. We hear what Baby hears and similar to, for example, using a POV shot, this puts us in Baby’s shoes, like a POH, point of hearing, experience. Simply by hearing voices from the direction that Baby hears them, the audience, maybe unconsciously, connects with Baby. Without all too much dialogue, almost no dialogue from Elgort, Baby’s hopes and dreams (and fears) are conveyed, while he attempts to get out of his forced employment for Doc, the mind behind the robberies, and run away with his Debora. In a way, Baby Driver’s narrative isn’t particularly surprising or innovative, yet it does spark a significant amount of empathy. Its vibrant rhythm combined with its stellar cast and precise and colourful direction by Wright makes it a fun and straightforward piece of cinema. With, not unimportantly, a spectacular soundtrack.

#baby driver#ansel elgort#edgar wright#jamie foxx#kevin spacey#academy awards#golden globes#film#film review#review#screenwriting#car chase#getaway driver#soundtrack#filmmaking#editing#pacing#jon hamm#lily james

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

After anti-big budget director Sean Baker’s success with iPhone shot-indie film Tangerine in 2015, he seemed ready to take his filmmaking to the next level. Whereas in Tangerine co-writer Chris Bergoch and Baker focused on two hookers roaming through the streets of LA on Christmas Eve, The Florida Project (2017) centralises unemployed single mother Halley and her defiant six year old daughter Moonee. Conceptually, Baker therewith chose two minorities with similar issues of prejudice and poverty, but his most powerful attribute, his attention to detail, makes these films fundamentally different, even though both are very much worth watching.

Moonee, captivatingly portrayed by Brooklynn Prince, is the epitome of juvenile freedom, raging through life like a fearless storm in a world populated by similarly struggling families in a pastel-coloured, $35 a night motel. Only a few miles ahead lies the painfully shiny representation of privileged happiness; Disney World; although its screaming contrast with the motel is only a subtle echo to the much louder and more skilfully executed narrative of the film. When mother Halley gets fired from her lapdancing job, life seems to carry on as normal: her and Moonee try to sell spa-going customers cheap perfume in parking lots and they eat leftover waffles that a downstairs neighbour sneaks them from the employee entrance, all the while both Halley and Moonee seem untroubled by the increasing pressure to make it through the week. Their lives are dictated by this vicious circle of “hitting and getting hit”, a circle not unfamiliar to many families living below the poverty line, which disables any of the motel’s inhabitants to genuinely get ahead in life.

Despite their recklessness and, at times, ferocious malice, Halley and, especially, Moonee have the viewers’ sympathy from the very first few frames as The Florida Project confronts its audience with the unfairness of being forced to raise your kid in a motel bedroom. This comes down to the actresses’ stellar performances and tender chemistry, as well as Baker’s poignantly realistic writing. While most would question the point of it all, Halley, in her own way, tries her best to provide and simulate something faintly similar to a mother-daughter relationship, making us, despite ourselves, root for her. It is, unfortunately, only a matter of time before Halley’s act of seeming invincibility unravels as she’s forced to sell the only currency she has left.

Seasoned actor Willem Dafoe plays the relatively small but important role of manager Bobby, who, too, tries to make the best of things while labouring through power cuts, the children’s pranks and rent payments. His stoic and mostly unwanted fatherly intentions emphasise the futility of it all: like a drop in the ocean, Bobby’s kind actions make no difference in the face of his tenants’s utter poverty. Baker’s careful comparison between different layers of society; Bobby the manager versus the building owner versus its tenants; demonstrates and pinpoints an element of futility in Moonee’s (and our) world. The poor stay poor, while the rich get richer. A terribly significant message that cannot be stressed enough in today’s political landscape, a message beautifully but painfully conveyed in this film.

The Florida Project’s cinematography is appropriately designed, with lots of energetic handhelds combined with static wides, as vibrant colours bounce off the screen (not unlike Moonee’s unstoppable energy) in beautiful 35 mm compositions. The choice of mostly unknown actors creates a strong sense of, what can be called, suspension of disbelief, wherein the audience soon forgets they’re watching a film and the viewer is immersed in, instead of just touched by, what’s on the screen. All in all, a beautiful and life-affirming piece of filmmaking that, I assure you, will stay with you long after you’ve left the theatre.

#the florida project#willem dafoe#sean baker#brooklynn prince#bria vinaite#florida#disney world#filmmaking#film#film review#35 mm#screenwriting#independent film#academy awards#golden globes#review

29 notes

·

View notes

Photo

An unrecognisable Robert Pattinson (Cosmopolis, Remember Me) quite literally leads the way in this gripping drama directed by the Safdie brothers. Good Time (2017) explores the relationship between Connie (Pattinson) and his mentally handicapped brother Nick (played by co-director Benny Safdie). Connie ‘rescues’ his brother from a counselling session, in which he’s hinted to have physically harmed his grandmother, after which the two set out to rob a bank. It, however, soon turns out they are in over their heads as Nick gets arrested and Connie is left to contrive another rescue mission (this time from jail). From there it goes from bad to worse and all eyes are on Connie, not only to see what he does next, but also to see if he will manage to keep it together. As Connie’s quest starts to come undone at the seams, the audience cannot help but wonder whether it is just Nick who’s dealing with mental issues or if his wild eyes are fired by more than his noble motivation to free his helpless brother.

Good Time’s soundtrack is a hypnotising, electro-based echo to an already disconcerting mise en scène. Its tempo is matched by the rhythm of the edit, along with the additional rising tension as a result of all the handheld shots. With each shot, cinematographer Sean Price Williams balances just the right amount of chaos with the actors’ outstanding performances, without it all being too much for the viewer to handle. Good Time was shot on film which allowed Williams to overexpose the image but keep the settings dark and eerie. This results in a graininess to the image, which is combined with neon lighting, a different colour in almost every corner of the frame, making for a very grimy, Blade Runner-y look. All of this; the handheld, the grittiness, the electro sounds; would make for a rather over-the-top perception of Connie’s already anarchic reality, if it wasn’t for the cast’s incredibly human performances.

In each close up, Pattinson’s intense stare captivates the audience. From the moment things turn south, the film is held on this edge of something that is hard to describe: it is a mix of despair, recklessness and anxious determination, which Pattinson embodies brilliantly in every scene. Connie’s plans to get his brother out seem to go out of focus at some point, causing the audience to grip the sides of their seats, while Connie himself never breaks a sweat. Or so it seems, as Pattinson, seemingly effortlessly, captures the many layers of his character in a display of conserved chaos. Like watching a car crash, the audience literally cannot look away, nor help to slightly root for Connie, the neurotic cause of most, if not all, his brother’s misfortune.

Apart from opening up discussion about mental health and its surrounding stigma, Good Time also includes subtle hints to other significant issues in today’s society. In line with last week’s review of ‘race-centred’ thriller Get Out, the Safdie brothers have planted similarly significant but more subtle hints to the questionable correlation between skin colour and crime (or, more poignantly, prejudice). This clearly demonstrates the Safdie brothers’s range and awareness, an awareness that makes me eager to see what they will come up with in the future. There is more to say, however, about the brothers’ slightly underrepresented voice: Good Time’s chaotically untangling narrative sadly diverts the viewer’s attention too much to really be able to fathom the directors’ true viewpoint. Some would say that it’s too ‘stance-less’ when it comes to the injustices tied with the execution of the law, but what the film might lack in angle, it makes up for in mindful nuance and, simply put, brilliant filmmaking.

#good time#robert pattinson#safdie brothers#benny safdie#josh safdie#film review#film#review#cinema#35 mm film#racial commentary#crime#mental health#golden globes#award season#academy awards#filmmaking#screenwriting

11 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Imagine being 6 years old, all alone, on a train going 200 miles an hour to a place you do not know. Okay and now really imagine it... Hard isn’t it? Well, not if you’ve seen this carefully composed film by the Davis brothers. Lion (2016) is based on the true story of Saroo Brierly, who, as a young boy, got separated from his brother in India, and travelled hundreds of miles on a train to Calcutta. All alone in a strange city, he eventually got ‘rescued’ and was adopted by an Australian couple (played by Nicole Kidman and David Wenham).

It is a story of hope and a feeling of belonging which either makes you wanna gag or cry, depending on whether you’re a skeptic or a romantic. Regardless of either, there is a fine line between a feel-good (and forgettable) Hollywood-esque movie and a life-affirming piece of cinema. With Lion, Garth Davis was mindful to stay on one side of that line, the right side. With a team that included leading man Dev Patel, captivating newcomer Sunny Pawar and audaciously vulnerable Nicole Kidman, there was little that could go wrong, you would say. However, Saroo’s story is a beautiful but slightly common one and it is easy to over-romanticise it: all it needs is a soppy soundtrack and overly dramatic dialogue and you’re placed on a mental shelf between Me Before You and any John Green adaptation. With old friend and main cinematographer Greig Fraser (Zero Dark Thirty, Foxcatcher), Davis aimed to display Saroo’s life in all its brutal reality. Instead of giving people a few hours of escapism finalised in a priorly-expected happy ending, Lion forces an unprecedented sense of empathy upon the viewer.

This film features the wide shot in all its glory and features it often. Without it, we would miss the chaos of the Calcutta streets, the many passing faces of strangers and, most importantly, Saroo’s seemingly shrinking body. In its first five minutes, Lion introduces us to this kind-hearted and eager kid and subsequently throws him under a metaphorical bus as he's faced with the impossible task of finding his way back home. Fraser’s wide shots are carefully entangled with just-close-enough-close ups creating a calm rhythm and pacing to the film, not unlike Saroo’s exterior: thousand miles away from home and we are left to guess the depth of fear he is experiencing internally as he stoically makes his way through the strange and overwhelmingly large city.

The thoughtful cinematography is strengthened by the film’s subtle but game-changing sound design. Carefully considering its audience, Lion makes India, an unknown world to many, feel tangible, real, and, therewith, appropriately daunting at times. Combined with the collaboration between Hauschka and Dustin O’Halloran, the soundtrack completes the work. If Lion was a body, each actor a bone, each frame an artery, then the sound would breathe life into it all like lungs, without which the whole film would not breathe emotion like it brilliantly accomplishes to do in less than two hours. Moreover, its last scene, a scene which everybody sees coming but no one is truly emotionally prepared for, is kept subtle and human and is a truly worthy ending to a moving and inspirational story, a story which most importantly, especially now, reminds us to never stop hoping for a way back home.

#lion#dev patel#garth davis#luke davis#nicole kidman#sunny pawar#dustin o'halloran#hauschka#india#film#film review#Academy Awards#cinematography#greig fraser#david wenham#australia#tasmania#home#script#scriptwriting#review

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Get Out (2017) is an exciting production in many ways. Director Jordan Peele worked on its script for over five years, which shows in the extreme attention to detail and versatility of the film as a whole. Is it a comedy? No. Is it a satire? No. Is it a thriller? Not really. It actually is a bit of all three of those things. An interesting new approach by first time director Peele, who bravely confronts post-Obama America (and the rest of the world) with its own racism, something many people believe to be a thing of the past.

Stellar acting duo Daniel Kaluuya (Black Mirror, Sicario) and Allison Williams (Girls, Peter Pan Live) are at the heart of this story, playing an interracial couple in their twenties. The film is (mostly) centered around Chris and Rose’s visit to her parents in the countryside. Right from the off, the audience is given little hints to what’s really going on: audible hints in the form of creaking sounds or gushes of wind, unusual cuts to even more unusual close ups and, more obscurely, verbal hints in the shape of racial remarks or allusions to (skin) colour. Additionally, some of the dialogue is painfully realistic, as each of Rose’s family members find something to say that distinguishes Chris from the rest, like “I know Tiger Woods!” or “I would’ve voted for Obama a third time if I could!” It is remarks like this that layer a very current reality into a somewhat absurd and comedic depiction of their interracial relationship. It is these mindless comments, as Daniel Kaluuya himself admitted in an interview, that create distance (even if the person giving the remark does not necessarily intend to). So, apart from the clear achievement in creating a film that mixes genres, Peele has also achieved to confront people with a form of racism that people fail to recognise as harmful, (maybe because it might not be physically harmful) but actually is just as discriminative.

It is important to consider Get Out among other recent productions, like Hidden Figures and 12 Years a Slave, that cover the same premises and display issues of (institutionalised) racism. The fact these films were set in pre-Civil War or post-World War realities; realities that, regardless of our level of empathy, none of us have lived in or feel genuinely responsible for; enables people to go “thank God we’ve moved on from those brutalities, eh?” i.e. It could make people feel like we’ve come a long way since then, when in reality, racism is very much still a present and pressing matter. By having Get Out play out in the present, Peele confronts us with the form of racism each and everyone of us is and should feel responsible for: a subtle, ongoing racism which’s harmfulness is often hard to pinpoint.

Brilliant acting by Kaluuya and Williams and Peele’s significant attention to detail shape the film, but are complimented by beautifully lit shots. The brown tones used in the mise-en-scene bring an earthly dimension to the narrative, yet, in combination with the cold pastel blues, gives off an eerie and uncomfortable feeling (a feeling, I’m sure, not unlike the feeling of being discriminated against). This feeling of literally wanting to ‘get out’ is then enforced by the overall sounds in the film, made up of creaky and creepy sounds alternating with maddening moments of silence.

Overall, a film worth seeing, seeing again and, most importantly, talking about: it’s 2017 and it’s about time to face that fact, with all the collateral diagnoses that come with it.

#get out#daniel kaluuya#allison williams#jordan peele#racism#institutionalized racism#oscars#academy awards#film#film review#filmmaking#awards season#acting#script#screenwriting#cinematography#editing#film editing

1 note

·

View note

Video

youtube

Hidden Figures (2016) is a historical drama that focuses on three ‘colored’ female mathematicians in the 1960s working at NASA. Katherine Johnson, brilliantly portrayed by Taraji P. Henson, was a physicist who calculated the trajectory specifics of several space missions. The film opens with Katherine making her way to the office, along with friends and colleagues, Dorothy Vaughan (Octavia Spencer); the first ever African American supervisor at NASA, and Mary Jackson (Janelle Monae); NASA’s first black female engineer.

These women played an essential role in achieving de-segregation in academic research agencies such as NASA, which undoubtedly makes this a story worth telling.

Director Theodore Melfi could have overloaded the film with political and ethical meaning. Instead, he quite literally lets these ladies take the stage and lets the characters speak for themselves. This not only results in their portraying actresses being able to give stellar performances (a particular one linked above), but it also allows the audience to relate to and empathize with Katherine, Dorothy and Mary. At the time, a myriad of developments concerning the Civil Rights Movement were taking place each day. By showing us these developments through the eyes of three powerful black women and their families, Melfi emphasizes the ‘fullness’ of their characters: their opinions are worth conveying to the audience. This not only sends a positive message about equality between races, but also between genders.

This incredibly significant message is intensified by its positive and well-thought out delivery. Hidden Figures was shot by cinematographer Mandy Walker on 35 mm film with anamorphic lenses, adding to the retro and ‘instagrammy’ look of the film. The warmth of the protagonists’ characters is highlighted through extensive use of art direction: the warm, brown tones of the family homes are designed to contrast with NASA offices’ cold and blueish tones. The brown look of their homes, and mister Harrison’s office, oozes warmth, inviting the audience to get to know its inhabitants. This same attention to detail shines through the costume design. Whereas NASA’s researchers (read: white males) are dressed in boring white shirts and ties, Katherine is attired in vibrantly colored dresses, making her literally clash with her surroundings. That being said, the rest of the cinematography and its mise-en-scene is quite ordinary, yet comfortably non-distracting.

This cannot be said of Kevin Costner’s portrayal of NASA manager Al Harrison, which is, indeed, very distracting. He fulfills the role of ‘white male hero’ who recognizes Katherine Johnson for what she is, a genius (and, the actual hero). Having Costner portray this seemingly unremarkable but hyped character only proves Hollywood’s continuing reliance on conservative narrative schemes. This is commented on more elaborately in this Guardian review by Marie Hicks. Hicks also comments on the film’s lack of nuance when it comes to its characters ‘working like dogs’ to accommodate a handful of white privileged men achieving their goal to travel to outer space, while black men and women had trouble traveling, even locally, without discrimination (or without having to abide by segregation rules on buses and in bathrooms).

More could be said about the film’s lack of ability to genuinely confront us with the racial problems faced by colored people in those days, and, in essence, the racial problems people are still facing today. The film sheds a light on the lives of three hidden figures, literally, yet remains unenlightening when it comes to what we can take away from this to apply to our own lives now. It is entertaining and tells a story of significance, but in the end, is too uncritical and has too little nuance or detail to confront its viewers with the fact these events of discriminations still happen today; maybe not in the same circumstances, but at least just as frequently as back then.

The fact remains that Hidden Figures tells the stories of three incredibly important women, however ‘Hollywoodized’ in its manner of doing so. Pharrell Williams contribution to the film’s soundtrack and the incredible performances by leading actresses Spencer, Henson and Monae make this a must watch and a strong contender for Sunday’s Academy Awards ceremony.

#hidden figures#octavia spencer#taraji p henson#janelle monae#theodore melfi#Oscars#Academy Awards#racism#historic drama#pharrel williams#movies#film#film review#cinematography

7 notes

·

View notes

Quote

It is difficult for a woman to define her feelings in language which is chiefly made by men to express theirs.

Far From the Madding Crowd (2015)

Being a woman, there is no way to not be extremely prejudiced and subjective about this film. Carey Mulligan is an exquisite actress and is joined by acting giants Michael Sheen and Matthias Schoenaerts. She portrays the ambitious and seemingly independent miss Everdene, who believes herself to have grown ‘too’ independent (which I think a lot of women from my generation can relate to). It is bizarre that this novel was written so long ago, since it is such a modern way of thinking: Mulligan’s character is given great nuance and is portrayed as person, instead of just a woman. The costume design in the film is maddeningly pretty (and so are the men) and the cinematography symbolises the wildness that continuously roams within miss Everdene’s heart, with brightly coloured, almost phosphorescent, shots of the countryside’s most underrated animals.

However, it seems as if, because the plot is so purposely not about men, her whole world revolves around these three men and their advances towards her. It is also difficult to figure out what it was exactly what Thomas Hardy tried to say with his novel: a woman should not be promiscuous because she will end up with an asshole for a husband, or a woman shouldn’t choose a husband in a fit of passion but as a result of a lifetime of companionship?

Either way, miss Everdene is a trailblazer, yet it is up to every viewer individually to define what kind.

#far from the madding crowd#thomas hardy#carey mulligan#michael sheen#matthias schoenaerts#thomas vinterberg#bathsheba everdene#film#film review#costume design#cinematography

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Dancing Arabs is a film by Eran Riklis, an Israeli filmmaker, who is somewhat known for the political echo accompanying his works. The storyline follows a young Palestinian from Tira, Eyad, whose father’s expectations of him force him to attend a Jewish school in Jerusalem. What is great about this film is that it brings so much character and culture with it. Every shot tells a thousand tales about Palestinians and their ongoing conflict with the Jewish.

Eyad, portrayed by Tawfeek Barhom, evidently struggles with the expectations of his family and his own expectations for himself as well as the prejudice of his peers at his new school. Juggling these two worlds is rough, yet Eyad handles it stoically. When he meets Naomi, gracefully played by Daniel Kitsis, the gap between the two worlds is emphasised by the secrecy surrounding their relationship.

Love is, once again, being portrayed as something seeping through any barrier, an all-penetrating energy demanding a more nuanced discussion than the ‘did not-did too’ quarrel their country seems to be in. By displaying such deep and complicated characters and zooming in on them specifically, the Jewish-Palistinian conflict is stripped down to its very core. To see this noble motive of explaining the Israeli-Palestinian conflict to outsiders is nothing new in film culture, there is even a whole Wikipedia page about it. Yet, the effects of the conflict are just an aspect of Eyad’s development as a character and an adult. He is struggling with the everlasting question of ‘Who am I and who do I want to be?’ and finds himself forced to choose a side because of the state of his country.

Some would say, and there is a spoiler from this point on, Eyad is simply a coward, choosing to get rid of all that he is, his whole Arab identity, just to be able to create the life he wants for himself, but I feel it is way more nuanced than that. The film is screaming for a more critical audience: an audience that hasn’t given up asking the right questions; an audience that isn’t tired of this infinite battle between two parties of which it can relate to neither of them. Especially for a ‘Western’ viewer like me, I feel addressed by this film to demand more than what my parents have dismissively muttered when I asked why these people couldn’t let each other be. Eyad’s story is just one of millions of stories that are still being lived out by people today. Horribly gruesome, yet heartwarming stories that are worth (re-)telling, according to Riklis.

#dancing arabs#eran riklis#tawfeek barhom#daniel kitsis#israeli#palestinian#conflict#film#film review

3 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

This film by directors Richard Glatzer and Wash Westmoreland is an adaptation of Lisa Genova’s novel by the same name, Still Alice. It depicts the life of linguistic genius Dr. Alice Howland and the downward spiral she is irrevocably pulled into after she is diagnosed with early onset Alzheimer’s disease.

The casting in this film is brilliant and not just because of its multitude of celebrity-actors. Julianne Moore, as a person and as an actress, brings her heart-warming presence and motherly gaze into the Howland family, which acts like glue to the whole film. Alice’s relationship with her children is incredibly defining for Alice’s character and therefore an enormously touching part of the film. To see these relationships evolve and, ultimately, dissolve in the light of Alice’s decay is heart-breaking. Especially the pivotal bond between Alice and her daughter Lydia (Kristen Stewart) reflects the strong bond between a mother and daughter, a bond that Alice herself only got to enjoy for a little while before her mother and her sister both died in a car accident. This tragedy, also defining of Alice, is beautifully edited into the film with short snippets of home-made videos of young Alice and her then-happy family, thus underlining the importance of memories and the tragedy of losing them.

While beautifully edited, acted and visually portrayed, Still Alice’s only critique accuses it of being too focused on moving its viewers, its being accompanied by an incredibly sentimental soundtrack. It is almost exceedingly trying to put tears in the eyes of their audience: seeing Alice, a brilliant professor in the area of communication, lose her effortlessness, her memories and, eventually, her ability to communicate with the people closest to her is heart-wrenching. Like a reversed zero-to-hero tale, the film could do little else but stir something within the viewer. Would the film be just as moving if it had been someone with any other job? If it had been someone without an array of successful and loving children? Probably not. But whether this matters is up to the viewer.

What, to me, is most characterising about the film is the incredible amount of empathy it evokes in anyone who watches it. The combination of Moore’s pure and life-affirming performance and Genova’s human-like and round characters makes Still Alice an important and necessary film. Alzheimer’s disease confronts us with our relentless determination to constantly keep collecting memories and materials while ticking things off of our endless bucket lists. The idea of losing our motor skills and memories force us to ask ourselves: who are we really? When our hands are too shaky to use the touchscreen on our iPhones and our tongues have forgotten how to tell our loved ones what’s on our minds. Still Alice, whether exceedingly sentimentally or not, asks us questions none of us know the answer to, which makes it worth our watch.

#still alice#julianne moore#oscars#academy award#kristen stewart#alec baldwin#alzheimer#alzheimers disease#lisa genova#kate bosworth#alice howland#linguistics

3 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

Selma depicts the lives of the people in the Civil Rights Movement, Dr. Martin Luther King in particular, and zooms in on the events leading up to the signing of the Voting Rights Act of 1965. To be reminded of the fact that these hardships were endured by the black population in America (and everywhere else probably) is utterly gobsmacking. What King and his companions did for the Civil Rights Movement is definitely something worth remembering and aspiring to, especially since similar injustice is still going on today. The story is brought to life by an extremely talented cast. David Oyelowo portrays King in a subtle but unique way, with all King's little traits seemingly intertwined with his own characteristics. Accompanying actors like Carmen Ejogo and rapper Common played their parts believably and empowering.

Whether the plot of Selma, which is based around the lead up to the signing of the Voting Rights Act, is an important enough story is unquestionable: as absurd as it may sound, racism is still a thing, a huge thing even, today. Prejudice and fear make this planet hard for people to live on every single day, however invisible this discrimination may be in some of our daily lives. Despite the necessity for this story to be told, the motion picture is build around it and is held up by the nobleness of its morals. This makes for a cinematically uninteresting film. There are no audacious editing sequences like in Wild and no particular cinematic quirks have been added like the altered aspect ratio in Mommy. Even though the story it's portraying is an extremely significant one, the film fails to justify the lack of cinematic excitement as a whole. The cinematography was innovative at times, yet became repetitive: the camera's focus was too determinant of the shot and became too self-assertive.

Film critics' obsession over Selma's factual (in)accuracy shouldn't matter to the viewer, yet it is my opinion that in this case it should, since there is very little else outstanding enough about this film to remark upon. It is a very safe (however contradictory that may sound) film and barely reaches, let alone raises, the bar in its genre, which makes it almost unfair to compare it to last year's 12 Years a Slave.

#selma#ava duvernay#oprah winfrey#david oyelowo#carmen ejogo#martin luther king#civil rights act#racism#film#film review#cinematography

0 notes

Photo

Based on the 2012 memoir by Cheryl Strayed, Wild tells the tale of a 27 year old woman, who lost her way after her mother suddenly died of cancer and has been on a downward and destructive spiral ever since. She repeatedly started cheating on her husband with random men picked up at random places, which led to an unwanted pregnancy, and eventually she developed a heroin addiction. With her life at its lowest point, Cheryl decides to walk 1,100 miles on the Pacific Crest Trail, which ranges from the border between the USA and Mexico all the way to its border with Canada.

The audience is introduced to her a few days into the hike: a graphic shot of Ms. Witherspoon's bleeding and swerving toenail demands the viewer's attention from the very beginning and leaves it unable to take its eyes off the female trailblazer. The entire spectrum of Strayed's character is displayed: she is lovable, rigid opposite her mother's opinions, self-centered, pessimistic, yet funny at times. All these shown traits send a message to the world: we, women, are no black-and-white beings. It's a relief (and a vindication) to see all these sides represented on screen for once. Witherspoon's acting lends support to this feminist viewpoint but also adds to the credibility of the whole film by playing Strayed's character in a natural, understated way.

As audaciously feministic as Wild may be, its strongest characteristic is by far its editing. Jean-Marc Vallée and Martin Pensa, who previously worked together on the edit of Dallas Buyers Club, have joined minds on this feature once again and created a mosaic of Strayed's memories, beautifully strung together like a narrative necklace. They have trusted upon the strength of visual images to create the narrative around its plot, instead of letting Strayed's voiceover be the sole go-to for the viewer. The results of this risk are astonishing, since the audience is given just enough information for curiosity for these characters to build, but still too little for the obvious zero to hero-plot to become repetitive. Because Strayed's story is a story we've heard before, the make or break balance is decided by its core relationship: the relationship between Strayed and her mother (brilliantly portrayed by Laura Dern). After having fled from a abusive father and husband, Cheryl is evidently more pessimistic than her mother about their financially scarce situation. “We are rich in love,” her mother Bobbi says, which is a memory that echoes through Cheryl's mind constantly when ploughing through 40 degree desert terrain. Bobbi's presence is so indelibly engraved onto Cheryl's character, which is reflected in the mosaic editing of her memories; the main trait of the film which will make you want to weep and crawl into the arms of your own mother. Both Witherspoon and Dern play their parts incredibly authentic, yet warm and familiar, and the apparent tenderness shared between them is everlastingly touching to watch.

As for the cinematography, there is no way any camera work could be as bad as to ruin the unbelievable views of landscape that Strayed marches through. The pure feel of these landscapes creates an interesting contrast between it and Strayed's destructive and wounded character, which is subtly emphasised by the stream of curses she still manages to blurt out while hiking through miles and miles of invaluable forest and mountains. Whether you do it by hiking 2000 miles, watching the film or reading Strayed's novel, this journey is one worth experiencing.

#reese witherspoon#wild#laura dern#michiel huisman#nick hornby#jean-marc vallée#cheryl strayed#thomas sadoski#pacific crest trail#feminism#film#film review#memoir

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

It is best to watch Foxcatcher without having done too much research beforehand. The tension will be much more tangible this way, trust me. Displayed is the relationship between two wrestling brothers, Mark and Dave Schulz, champions at that, whose bond, from the very beginning, seems to be at the core of this story. Their parents were out of the picture very early on in their lives and Mark is raised by Dave, which casts an eternal shadow over his achievements. Both are gold medalists, yet Mark feels unseen next to his brother. When philanthropist John E. Du Pont enters their lives and persuades Mark to train on his wrestling estate, Dave is uneager and chooses to stay with his family, to great dismay of Du Pont, as it turns out.

The main body of the film zooms in on Mark's struggles with being the younger and less successful little brother and the downward spiral he enters once he is dragged into the use of drugs by his now coach. Du Pont has a fearsome presence, to put it mildly, but as an audience, you can sense that he puts the faith in Mark that he has always been missing when he was side by side with his brother. Mark's determination to impress his brother without his help is reflected in Du Pont's persistence in trying to please his mother; an enormously rich woman who seems only to care for her family's legacy and the million dollar horses she holds. This dedication of Du Pont to in some way impress her forces us to feel that little bit of sympathy for him as a person, despite some of his eerie traits.

It is astounding how much of the wrestling you get to see as an audience in this film, without even the slightest urge to feel bored. The camera is put right in the middle of the action and the sound effects unnoticeably add to the strength of the wrestling sequences as well as soften the film where needed. About halfway through the film, when Dave finally decides to join his brother on the Foxcatcher training site, unshakeable darkness falls over the film and its characters. As a viewer, even if you didn't know there was going to be one, you feel their downfall coming way before it happens, yet it isn't weakened by this build-up: when it finally hits, the blow is much harder as it is, again, in a subtle way supported by a fear-provoking sound layer of deafening silence.

The acting, especially by leading males Mark Ruffalo and Steve Carrell, was restrained, but in a good way: it made it so much more realistic and it made their characters a lot more real. Carrell's cosmetic make over wasn't something particularly interesting to me, yet it did make him that much more unfathomable (and, honestly, a little scary). All in all, a pretty good film, of which the ending will stick by you for a long time after you've walked out.

If you can, pay extra attention to the subtle hints of wrestling customs integrated into the brothers's everyday activities. Noticing these adds to the sense of intimacy of the sport and the passion they feel for it.

#channing tatum#mark ruffalo#foxcatcher#john e du pont#steve carrell#bennett miller#film#film review#wrestling#plot twist#tension#oscars#mark schulz#dave schulz

0 notes

Photo

No other film has received so many mixed reviews as Clouds of Sils Maria has. It illustrates the life of famous actress Maria Enders as she is at what seems to be the top of her career, which started when she was picked up at only 18 years old to play Sigrid, the role of a lifetime, in both the play and film versions of Majola Snake. The director that spotted her, Wilhelm Melchior, dies early on in the film and Maria, on repeated insistence from her personal assistent Valentine, retreats into the mountains of Sils Maria to rehearse Majola Snake, but now for the role of sidelined Helena to a new Sigrid, fresh out of rehab it girl Jo-Anna.

What makes the film great is the incredible chemistry between leading ladies Juliette Binoche and Kristen Stewart, who, as celebrity and accompanying assistent, share an intimate relationship in which Maria holds a tenacious, almost stubborn, view of the modern actress, while Valentine (Stewart) shows a more open-minded opinion on modern society's idea of ‘film’ and its ‘business’. Their relationship is clearly a mirror to the relationship presented in Majola Snake and during their rehearsals together, the line between their relationship and the one between Helena and Sigrid begins to dissolve. The interesting dynamic, however, loses most of its strength because of its unorganised (yet overly evident) plot line and editing. Instead of tying the film together, the random shots of Sils Maria's blueish mountains intersecting the various ‘chapters’ of the film rip the already skimpy narrative apart.

About halfway through the film, the audience starts to lose their grip on what's happening, either because of the emergence of subtle boredom or the complete loss of empathy on behalf of the two lead characters. You start to lose Stewart and Binoche at some point too. Their relationship and random outbursts of laughter start to seem like a joke that only they are in on; the audience is left out. The film lacks coherence of narrative when Valentine, with little sensation and a somewhat unjustified reason, leaves the ‘stage’. Events following up her parting with Maria seem arbitrary and loose endings are hardly tied together at all. Not even the returning strength in the ending, in which Maria's obsession and struggle with age and ageing is symbolised and the viewer is relieved to find something resembling the film's moral, can really validate the chaotic structure of the rest of the film.

However large my love for these actresses is as individuals, as a pare, it is very hard for me to form a balanced opinion, especially in such a cinematically unremarkable film. Nonetheless, my love for them remains unscathed.

#kristen stewart#cesar award#juliette binoche#clouds of sils maria#chloe grace moretz#film#film review#olivier assayas

0 notes

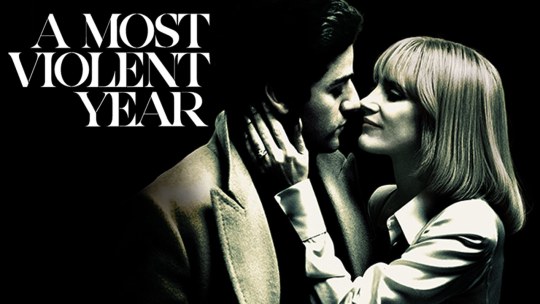

Photo

Set in the year 1981, which has been, up to this point, literally the most violent year in New York, A Most Violent Year presents the life of hard-working Abel Morales, who owns an up and coming oil company. He is defined by his determination to run his business (and his life) in a nonviolent way. His wife, Anna Morales, however, is the daughter of an imprisoned maffia gangster, which makes her no stranger to the violence surrounding her family.

From the outset of the film, the differences in view on violence between Abel and Anna's characters create a creeping tension, in which the audience is unsure who to empathise with. Abel refuses to fight violence with violence, stubbornly evading to arm himself or others around him. This trait seems, at first, an unavoidable and charismatic part of his personality, yet, as the film progresses and violence around them increases, it quickly becomes an undeniable cause for pity: Abel is ignorant to the danger surrounding him and his children, almost to the point of stupidity. Anna appears to tolerate her husband's ‘cleanliness’, while, as it turns out, she herself believes in a completely different approach.

Apart from the incredible performances by Jessica Chastain (beautifully dressed in custom made Giorgio Armani costumes) and Oscar Isaac, this film is a joy to behold because of its incredible cinematography. While a film with bad camerawork can still be a great one, an OK film with magnificent camerawork will instantly be an amazing motion picture. It determines the look ánd the feel of the film, which it did beautifully for this one. Individual shots of incredible precision and attention for detail (and colour!) fitted together like a mosaic, showing the audience a detailed display of suffering through (or despite) nonviolent perseverance. Director J.C. Chandor's predilection for unwavering characters seems to have groomed him intensively, since the audience isn't aloud to miss a thing. The tension entangled in the plot is effortlessly supported by some of the handheld camera work and the colouring of the film. It's a very poised film, but not posed, which gives it a greatly realistic and threatening feel.

The film is wrapped up by a climactic sequence in which the audience is put in between two parties, both of which hold a great amount of their sympathy. I urge you to look out for one of the final shots (you'll know it when you see it), in which the film is summarised both audibly and visibly, in a symbolic representation of Abel's struggle of trying to stay ‘clean’ in a very dirty world.

0 notes