#ziblatt

Text

« Since 1945 I don’t think there has been a politician in a democracy who’s used such authoritarian language, ever. It’s hard to think of anybody. Viktor Orbán, Vladimir Putin when running for office don’t use the kind of language that Donald Trump uses, so that’s pretty notable. »

— Daniel Ziblatt, author and political scientist at Harvard University, quoted at The Guardian about the violent and incendiary language used by Trump and his followers.

In that same article, we hear the MAGA crowd is already threatening violence over an election they haven't yet lost.

One of the police officers injured by Trump's January 6th terrorists made a prediction.

“Regardless of whether Donald Trump wins or loses, there’s going to be violence,” said Michael Fanone, a retired police officer who was seriously injured by pro-Trump rioters at the US Capitol on 6 January 2021. “If Donald Trump loses, he’s not going to concede and he’s going to inspire people to commit acts of violence, just like he did in the weeks and months leading up to January 6, 2021.

“If he wins, I also believe that there’s going to be violence committed by his supporters, targeting people who previously tried to hold him to account, whether it was members of the press, average citizens like myself, Department of Justice officials, state and federal prosecutors. I believe him when he says that he will have his vengeance.”

There will probably be violence if Trump loses but it won't last long. A big difference now is that Trump does not control the National Guard, the Army, the FBI, and federal prosecutors. That 4 hours of rampaging and defecating terrorists at the Capitol certainly won't be repeated.

On the other hand, if Trump wins, we'll have 4 long years of intermittent political violence by Trump's brownshirts which will go unpunished. And that's 4 years if we're lucky. Trump treats the law as an option to be ignored if it suits him to violate it.

So don't be intimidated by MAGA loudmouths like Charlie Kirk.

In an early preview of how aggressively Trump’s supporters might react to defeat, Charlie Kirk, a far-right political influencer, told an audience at a faith-based event last week: “I want to make sure that we all make a commitment that if this election doesn’t go our way, the next day we fight. It’s a very important thing; a lot of people don’t want to hear that. They say: ‘What do you mean it doesn’t go our way? It has to go our way. We have to win.’ I agree.”

If pro-democracy forces stay united and make sure that every single voter opposed to violent dictatorship votes to re-elect Joe Biden, the next few years may provide a breather for us – at least domestically. An unequivocal defeat for Trump will spark a crisis in the GOP; it may even cause a rupture in the party.

NOW is the time to get personally active in politics in real life. Slacktivism doesn't win elections but grassroots precinct work does.

#donald trump#maga#political violence#poor loser trump#republicans#the gop#charlie kirk#fascism#brownshirts#election 2024#michael fanone#biden-harris 2024#vote blue no matter who#make republicans go the way of the whigs#daniel ziblatt

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tune-up or Rebuild the Machinery of Government

A few years into the Trump presidency, two Harvard University professors of government, Steven Levitsky and Daniel Ziblatt wrote How Democracies Die. The book was a best-seller, calling out the decline in tolerance and respect across political party divides. The pair followed that effort in 2023 with Tyranny of the Minority. Equally popular, this volume highlights historical crises to make…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

0 notes

Text

A Republic -- If You Can Keep It

Legend has it a woman asked Benjamin Franklin a question as he exited Independence Hall after the Constitutional Convention in 1787. “Doctor, what have we got? A republic or a monarchy?” Franklin supposedly replied, “A republic, if you can keep it.”

As I’ve expressed before, I keep looking around at what’s happening in this country, both in our government and among our society, and I’m not liking…

View On WordPress

#current state of the nation#Daniel Ziblatt#How Democracies Die#social intolerance#Steven Levitsky#U.S. Constitution#violence becoming the norm

0 notes

Text

The 6 January Congressional Committee Report: Democracy Discarded

The 6 January Committee has released its summary of a report. It should alarm us all. It should light a new fire of urgency to hold Trump et al. accountable before the 2024 elections. Will it?

The 6 January Committee, Trump, and the Risk to Our Democracy that White People Perceive

Now that the 6 January Congressional Committee’s introduction to its final report is out and being dissected by all the punditing pundits and head talking talking heads — it will soon be a double header with the actual report being published tomorrow (if I publish in time, big if, right?) — we should…

View On WordPress

#6 January Committee Hearings#6 January Insurrection#Coup#Daniel Ziblatt#Democracy#Democratic Institutions#Insurrection#Karen Stenner#Pundits#Steven Levitsky#Terri Kanefield

0 notes

Text

NEW TALKING POINT

THAT THE CONSTITUTION IS "OUTDATED" BY "TRAITORS"

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

KAMALA HARRIS' MILWAUKEE DEBUT: "WE'RE NOT GOING BACK!"

TCINLA

JUL 23, 2024

This is from Anand Giridharadas’ Substack “The Ink”:

I’m on an airplane as I write this. And one measure of the excitement in the country is that, as Vice President Kamala Harris spoke at her first rally since the dramatic events of recent days, virtually every in-seat television screen I could see was set to a live feed of her in Wisconsin.

Vice President Kamala Harris’ debut rally was outstanding, drawing on so many lessons of persuasion that others neglect.

She very pointedly took the fight to Trump at the beginning, carving the contrast narrative of a prosecutor versus a felon, a fighter for justice versus a perpetrator of injustice. But then she pivoted and made clear that beating Trump isn't enough. Nor is saving democracy.

It's about, she said, the ability to fight for you, for your family. This is what the Harvard scholar Daniel Ziblatt calls the "bank shot" to save democracy: we have to save democracy and defeat a fascist, but not only for its own sake, but also to have the tools to make your life better tangibly.

When it came to talking about policy, she kind of didn't! Which is terrific! As Anat Shenker-Osorio, the messaging guru, says, sell the brownie, not the recipe. Policy is a recipe. She spoke instead of the human end states of policy. Having childcare, being able to live and thrive and rise. Brownies are yum.

Harris also did a great job of framing the two visions as forward versus backward, past versus future, but then, again, she made it about us. You have the choice between going forward and backward. You decide what kind of place we are. Simple, sharp, clear, empowering of us.

On a more superficial but no less important level, she was having fun up there. She would rather be up there than anywhere else. Too often, movements for progress don't embody the joy they promise to usher in with policy. She is showing that freedom is more fun than tyranny.

The pro-democracy movement has in recent years somehow allowed the fascists to throw the better party. To be the exuberant, joyous ones. To be energetic. She is reminding us that you can't just appeal to the head; you have to throw a cookout that people want to be at. Period.

We might have seen a catchphrase be born in real time: "We're not going back." Has it all: the "we," the adamant refusal, the calling out of retrograde nostalgia.

So a few core themes become clear: She and Trump are foils who have lived opposite lives. He and his extremist and rich friends aren't focused on your life, but Dems are. There is a choice between taking on the future and going back to the past, and it's ours to make.

It's one speech, and it's early days. But in recent years, a lot of very cutting-edge new thinking in messaging, such as that practiced by Shenker-Osorio, has come to light, and too many Democrats have ignored it. Today's rally marked a break. This is how you speak and win today.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

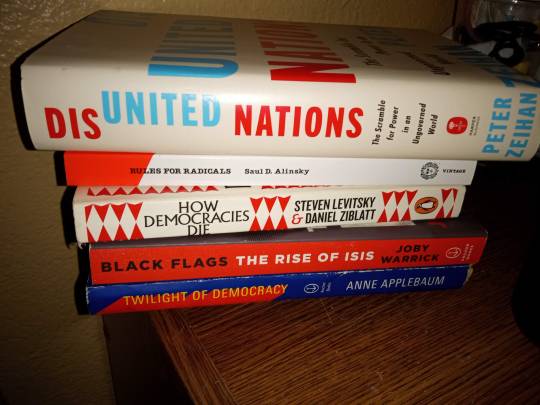

2024 Reading List 📚

Here is my reading list for 2024 and all the books I plan to get to that are not for school. Sorry for how non aesthetic the pictures look.

Dis United Nations by Peter Zeihan.

Rules for Radicals by Saul Alinsky.

How Democracies Die by Steven Levitsky and Daniel Ziblatt.

The Rise of ISIS by Joby Warrick.

Twilight of Democracy by Anne Applebaum.

Soft Power by Joesph S Nye Jr (eBook).

I'd like to try to read more novels this year, but I don't currently have any in mind right now. However, I used to be really into Ernest Hemingway and Jane Austen, so maybe I will reread some favorites of mine.

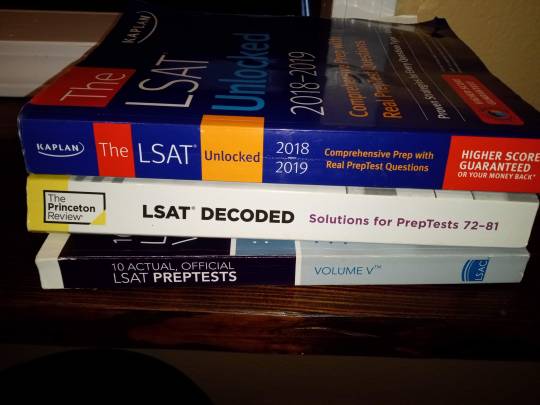

These are also the books I plan to use for the LSAT.

Not pictured:

Lawhub tests | Khan Academy Prep | 7Sage LSAT Prep

I'm also trying to expand my vocabulary with GRE prep. Moreover, I also want to start doing word puzzles and sudoku regularly.

#studyinspo#study blog#grad student#studying#lsat#lsat prep#reading#reading list#2024#studyspo#study motivation#studyblr#study aesthetic#student life

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

— When the 2000 election recount ordered by the Florida Supreme Court was halted by five corrupt Republicans on the US Supreme Court — handing the White House to George W. Bush by a disputed 537 votes — nobody knew at the time that Florida Governor Jeb Bush’s Secretary of State, Katherine Harris, had commissioned a huge purge of voters, using a list of Texas felons that was 68% Black and Hispanic.

Harris did this because the national pool of Black and Hispanic names is relatively small: Black felons in Texas with names like Jim Washington or Jose Gonzalez are extremely likely to have similarly named counterparts in any other state with large Black and Hispanic populations like Florida.

Thus, when those Texas names were compared via a “loose match” (didn’t require a birthday or middle name match) with Florida voters’ names, disproportionate numbers of Black and Hispanic Florida voters were deemed to be possible felons who’d somehow recently moved to Florida from Texas, and tens of thousands were removed from the voter rolls. As the US Commission on Civil Rights noted:

“14.4 percent of Florida’s black voters cast ballots that were rejected. This compares with approximately 1.6 percent of nonblack Florida voters who did not have their presidential votes counted. … [I]n the state's largest county, Miami-Dade, more than 65 percent of the names on the purge list were African Americans, who represented only 20.4 percent of the population.”

— When Donald Trump was certified the winner of the 2016 election, nobody knew at the time that Russia had illegally poured millions of dollars and hundreds of thousands of man-hours into targeting swing state voters identified by the RNC, whose names were handed off to Russian Intelligence by Trump campaign manager Paul Manafort.

When Robert Mueller’s FBI team determined this crime had helped put Trump in the White House, and that Trump had personally intervened in investigations ten separate times in ways that could be prosecuted as criminal obstruction of justice, Bill Barr kept the news from America until the story had largely faded from the headlines.

What will it be this November? We have some clues.

— With the blessing of five Republicans on the 2018 Supreme Court, Republican-controlled states with large Black and Hispanic populations are purging voter rolls like there’s no tomorrow. Just between 2020 and 2022, fully 19,260,000 Americans — 8.5% of all registered voters — were purged. The purge rate in Red states was 40% higher than the rest of the country. We won’t know this year’s purge numbers until well after the election is over.

— The GOP is trying to organize an “army” of 100,000 rightwing warriors to show up at polling places to “oversee” elections and challenge voters they think look suspicious. They’ll also be challenging signature matches on mail-in ballots, particularly in Blue cities in Red states.

— Republican elected officials from the state level all the way up to the US Senate are refusing to say that they’ll accept or certify the result of the election this fall if Donald Trump doesn’t win. Multiple Republican members of Congress have asserted that only the House of Representatives should decide the presidential election this year (which would throw the election to Trump regardless of who the voters or electoral college choose).

— In multiple states, Republicans have passed laws allowing them to manipulate and change the location of polling places, criminalize voter registration drives, replace Democratic and nonpartisan election officials with partisan GOP hacks, and in Georgia and Arizona throw out ballots from entire precincts. As Steven Levitsky and Daniel Ziblatt noted for The Atlantic: “Throwing out thousands of ballots in rival strongholds may be profoundly antidemocratic, but it is technically legal, and Republicans in several states now have a powerful stick with which to enforce such practices.”

— Typically, when politicians engage in nakedly deceptive politicking or election theft they’re outed in the press and punished at the polls. Since 2020, however, Republicans have rewarded their politicians who tell lies and engage in underhanded tactics, suggesting there will be no limits to what the Trump campaign might do or say in the weeks leading up to the election, including the use of deepfakes and AI.

— Saudi Arabia and Russia — both allies of Trump — have cut oil production by over 1.4 million barrels a day to drive up gasoline prices leading up to this November, just like they did in a dress rehearsal during the fall of 2022. History shows that gas prices spiking over $5 or even $6 a gallon will have a measurable impact on inflation and thus the election.

— Russia fielded a small army of online trolls to assist Trump’s electoral efforts in 2016 and 2020. Expect the same in November, except this time, according to Secretary of State Anthony Blinken, China is also getting into the act on the GOP’s behalf.

— Benjamin Netanyahu defied President Obama when he was engaged in delicate negotiations with Iran, visiting the US and addressing Congress at the invitation of Republicans. He’s expected to do the same slap-in-the-face gesture this fall to Biden, along with defying the president’s wish that Israel minimize civilian casualties in Gaza. Netanyahu will do everything he can to ensure Trump comes back into office if for no other reason than keeping himself out of prison; demoralizing young progressive voters will almost certainly be at the top of his list.

But these are all things we know about right now, even if there’s little we can do about most of them.

Given the Nixon/Reagan/Bush examples, our biggest concern should be to find the things we’d otherwise look back on after the inauguration and say about them, “Nobody knew at the time…”

2 notes

·

View notes

Quote

I would say the hypothesis of the Biden presidency was that if you address people's material concerns, this will take some of the steam and anger out of the populist movement — this rage that fuels Trump and continues to fuel MAGA. And I think there's a lot to that. It's a pretty good bet to make.

Daniel Ziblatt

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Political scientist Karen Stenner explains it this way: As liberal democracy expands and includes more people, it becomes more diverse and complicated. The growing diversity and complexity trigger authoritarian reactions in people who are averse to diversity and cannot tolerate complexity.

This is particularly true when an increasingly diverse electorate threatens the power and status of the ethnic majority. Daniel Ziblatt and Steven Levitsky, Harvard political scientists, put it this way:

“It is difficult to find examples of societies in which shrinking ethnic majorities gave up their dominant status without a fight.” (How Democracies Die, p. 207.)

Members of the Republican Party who reject democracy are part of a movement that has been springing up worldwide, which we can call the “New Radical Right.” This movement has much in common with the fascist regimes of the 1930s. Hitler’s regime, recall, was partly a reaction to the growing diversity in cities like Berlin.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Democracy & Turkey

My notes from 2019:

Defining the Problem

The nature of Turkish democracy remains undecided; it is still the unconsolidated archetypal hybrid regime it was when the idea of Turkish democracy itself began (Turan, 2015); therefore, explanations of the outcomes of the struggles towards democratisation today should be informed by discussions of the past (Capoccia & Ziblatt, 2010). The fact that the majoritarian scope of democracy is at risk of descending back into the authoritarianism it attempted to free itself from is nothing new. The history of Turkish democracy generally conforms to this unfortunate tendency. The history of the modern Republic tells us that it is not unusual for a party to be in pursuit of a democratic agenda only so far as it remains in their own interest. This pattern is traceable from the 1960s to the present era, and it has been explored in detail by other authors (Ahmad, 1977; Heper, 1985; Özbudun, 1995). This makes clear that a strategic commitment to democracy, rather than an authentic commitment, is one of the tenets of Turkish democracy (Kaya & Whiting, 2019).

Nonetheless, strategic commitments to democracy which oppose normative, attitudinal commitments to democracy, or as Pridham (1995) coins it, ‘positive democratic consolidation,’ can still result in real democratisation. ‘Positive democratic consolidation’ can emerge from what were originally strategic commitments, even under difficult structural conditions; provided the contextual and institutional factors are in good order, thereby leading actors to form binding commitments to democratic practices (Alexander, 2002; Przeworski, 1998; Salamé, 1995). The fact however remains that no incentives for elite-led consolidation have existed in Turkey in the past. Furthermore, there are none to be seen in Turkey under the Justice and Development Party (AKP – Adalet ve Kalkinma Partisi) at present (David, 2016). Pluralistic democracy is not encouraged by the dominant structure of Turkish democracy, which was born out of multi-party democracy and which has formed its framework to this very day. Çınar and Sayın have illustrated the tendency Turkish democracy has of functioning within the framework of a certain historical paradigm – one which ‘reinforces an anti-pluralist attitude’ and ‘routinises a zero-sum perception of politics in which only one party wins.’ (2014, p. 367).

The history of Turkish democracy is a story of two elites, the tutelary and the often centre-right populist, in a tug-of-war for control over the state; both claiming a right to power on the basis of the national interest or majority support (Tas, 2015). Liberalism and pluralism have become collateral damage in this struggle for control of the state, as they are both of little importance to either elite. The lack of concern for these concepts can be seen clearly in the enactment of four major coups and the embargo on various Islamist, Kurdish, and leftist parties (Öktem, 2011). In 1961, clauses were added to the constitution specifying distinct divisions of power, and in 1982 clauses were added which limited the prime minister’s power. Yet the introduction of such liberal measures came to nothing. Retrospectively, these policies can be seen having been employed by one of the elite groups in order to restrict the power of the opposing elite, thereby increasing their own power. It was in this manner that the AKP, acting as the most recent embodiment of the centre-right populist tradition, gained control of the state and removed the threat of military intervention from the tutelary elite, under the guise of majoritarian democratic practice. The distinctive characteristic of the AKP was the centralisation of power; originally into the hands of the party, and afterwards into the hands of its president, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan (Kaya & Whiting, 2019).

The nature of Turkish democracy is such that the decisions of the elected representatives have frequently been overridden by the tutelary capacity of the armed forces, in the guise of protecting a national interest that is not defined by any voter’s interests. Under this tutelary democracy, the state has ostracised, ‘‘othered” and attempted to remove the political rights of certain minorities that posed a threat to the established order (Celik et al. 2017). The AKP first viewed minorities in the state as potential allies; due to the fact that in the past, they had experienced an antagonistic relationship with the tutelary elite. Circumstances quickly changed, and when support from minorities was no longer crucial and actually threatened the state’s control over the population, the AKP followed in the steps of its predecessors (Kaya & Whiting, 2019). The state once again became a tool for the suppression, criminalisation and ostracisation of minority groups – regardless of whether they were violent or nonviolent in nature, they were proclaimed to be a threat to Turkish democracy.

Democracy as a Contested Concept

Academic definitions pertaining to democracy typically emphasise the institutions and processes related to democratic government. Robert Dahl (1971) argues that democracy corresponds with the mechanisms and rituals of representative government. Thus, provided the citizens are free to participate in open and honest electoral processes and that these elections result in the formation of representative governments, the prerequisites of democracy are satisfied. It is entirely reasonable, therefore, to anticipate that most individuals will conceive of democracy using terms such as free and fair elections, multiparty competition, and majority rule. Somewhat unsurprisingly, research which requires participants to select from a range of possible choices by which to describe democracy frequently reveals that concepts such as voting, elections and procedural choice are identified as principal defining traits (Dalton et al., 2007).

As a procedure-based conceptualisation of democracy, the concept of polyarchy was introduced by Dahl. Thus, he was able to generate a distinction between political democracy and idea-normative democracy (1971). The embracing of competition and participation is a critical aspect of the development of a polyarchy. Thus, all citizens must define their political preferences and communicate them to their fellow citizens via the electoral process. As a consequence, governance can be deemed as taking effect through both collective and individual action, while precluding any interference occurring by means of discrimination (Dahl, 1971).

Opposition to the government in power is crucial since an authoritarian system with one dominant party constitutes a threat to democracy. Thus, governments who are stable should exercise tolerance towards the opposition, provided that the wider populace demonstrate respect for the government. It is therefore clear that in Dahl’s view, in order to be considered a democracy, any given government must act in a responsive manner towards its citizens. In addition to this requirement, Dahl (1971) identifies eight other requisites for democracy: freedom of association, freedom of speech, the right to vote, the right of politicians to campaign for support, the availability of alternative information sources, free and fair elections, institutional guarantees, and institutions capable of enacting government policies.

Huntington’s Third Wave of Democracy (1991) extends upon the concept of democracy first proposed by Dahl, defining democracy as a political system in which the most authoritative decision-takers are chosen through regular, fair elections wherein competing candidates vie for votes from amongst almost the entire adult population. Like Dahl, Huntington focuses upon the dimensions of contestation and participation as crucial determinants that are capable of defining and comparing a political system as democratic in character. The critical determining trait of democracy, albeit not the only determinant, is the presence of free and fair elections (Huntington, 1991). In contemporary society, populist politicians aim to safeguard their robust electoral command by falling prey to electoralism. Thus, for populist leaders, elections are the only features which are capable of legitimising democracy.

The definition employed by Joseph Schumpeter in Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy conceives of democracy as an institution-based means of reaching political consensus where, by compelling the populace to make decisions through electoral processes, the common good is recognised as preeminent (1942). Thus, these procedural arrangements comprise an unstandardised conceptualisation of democracy. Moreover, whilst Schumpeter recognises that free, fair and regular elections will determine what is beneficial or disadvantageous for any given society, he contends that the common good cannot be deemed to exist as a simple or objective phenomenon.

Democracy is simply a process of collective decision-making, albeit a powerful one, wherein members of a society chose their rulers. Yet, basing decisions on majority rule or on the results of voting or referendums poses hazards in the absence of sufficient legal and institutional restrictions (Schmitter & Karl, 1991); since it is critical that ethnic, religious, political rights be shielded by phenomena such as constitutional reviews or court rulings. Thus, any regime which limits democratic participation on the grounds of ethnicity, religious background, literacy, wealth, or profession cannot be deemed a democracy.

Democracies allow rival visions, interests and ideologies to compete through fair, regular elections where citizens can choose from amongst these contesting dogmas in accordance with their comparative strengths and weaknesses. In this sense, criticism of procedural definitions of democracy tends to be orientated towards democratic procedures, particularly elections, whilst failing to consider other facets of democracy. According to Terry Lynn Karl, simply equating democracy with the electoral process is a fallacy. Whilst fair and free elections which are conducted on a regular basis are important in a democracy, this type of political regime comprises much more than this one trait alone. Any definition must move beyond mere electoralism and consider the accountability of elected representatives who are held responsible for their actions once democratically installed into office. Thus, the vertical accountability of elected representatives and rulers to the electorate serves to maintain or even enhance standards and effectiveness in a democratic regime (2000).

In addition, studies which are elections-focused tend to ignore the importance of civil liberties within democracy. Norris (2000) is a significant scholar who provides a definition of democracy that includes concepts of political liberalism. For her, democracy is three-dimensional. The first dimension is subjecting positions of government power to pluralistic competition amongst parties and individuals. The second dimension is that parties come into power through free, fair and periodic elections which are participated in by equal citizens. The third dimension is that successful competition and democratic participation is ensured by civil and political liberties to assemble, organise, speak, and publish with freedom (Sahin, 2016).

Liberalism, for Zakaria (1997), is placed at the centre of any authentically democratic state. They go yet further to claim that a liberal autocracy is preferable to an electoral regime that lacks liberal practices, as the civil rights of the populace are of primary importance. Diamond (1999) joins in proposing that those facets of democracy that are not centred around elections must be considered of equal importance, because it is only in political liberalism that civil rights are ensured. In order for a liberal democracy to exist, limited definitions of democracy, centred around merely the concept of free and fair elections, must be discarded (O’Donnell et al., 1986).

Such procedural definitions trivialise the link between public desires and government actions, by operating under the assumption that democracy is defined by its ability to follow procedure. Yet, Sartori (1995) considers democracy’s history; that democracy was only a political form a century ago, and economic aid was not expected of the state. He writes that for over a century, democracy did not require economic gain and prosperity to be considered sustainable. It was only as Western democracy developed that liberal policy was altered, and constitutional matters began to centre more round ideas of “who gets how much of what.” Sartori suggests that it was only then that definitions of modern democracy became further mingled with economies (1995).

Within this context, the effects of the differences between formal and substantive definitions of democracy is a grave matter for Heller (2000). The core logic behind liberalism’s advocacy of procedural democracy in its own right is based upon the logic of associational autonomy; a logic which is impaired by the endurance of social inequality within a state. Socio-economic conditions often prevent marginalised communities from securing or exercising basic human rights in developing nations. Autocratic political action may be the end result when a formalistic version of democracy fails to rid a society of such limitations, heightening social tensions. Thus, Heller proposes that democracy be measured not only by its procedural standards but by the outcomes created by its democratic practice (Sahin, 2016).

That is why, in addition to these solely ‘political’ definitions, there exists another conceptualisation of democracy which tends to emphasise the social and economic aspects of the phenomena. That is to say, democracy can also be circumscribed by its consequences. These are commonly conceptualised as freedom and autonomy, with democratic institutions constituting the intermediaries through which these objectives are attained. Since individuals readily identify with ideals such as liberty, recognition of the generally accepted outcomes of democracy may engender wide support for democracy, irrespective of whether individuals actually fully comprehend the nature of democratic institutions (Dalton et al., 2007). Whilst other political systems might seek the same goals as democracy, there exists a glaring inconsistency between ideologies such as autocracy and the desire for freedom and rights.

Additionally, it is frequently claimed that the desire for democracy in emerging nations equate simply to a desire for improved living standards. Thus, democracy is often closely identified with the affluence encountered in advanced societies and an endorsement might equate more to a wish to mimic this economic success than to the desire to uphold specific political standards. Consequently, economic advancement, social welfare and economic security might well be postulated as critical components of democracy. One survey of attitudes amongst Eastern Europeans in 1990 found that when asked to select from amongst three political values and three economic values regarded as crucial to their own country’s advancement, most respondents equated democracy with prosperity, security and equality (Dalton et al., 2007).

There exist three principal choices which can be employed when defining democracy, to wit: institutions and processes, freedoms and rights, and social gains. Whilst individuals will propose alternative characteristics if required to provide an unstructured response, the three categories outlined above are effective both as a framework through which to examine the clear support for democracy demonstrated in contemporary opinion polls and as a means of evaluating the implications of the desire for democracy (Dalton et al., 2007). Each of these three choices conveys different subtexts in relation to the public attitudes and values which shape the drive towards democracy.

The Peculiarity of Contemporary Turkey

The rule of Recep Tayyip Erdoğan is representative of a particular era. This particular era is one in which the lines generally drawn between nationalism, populism, and Islamism have become blurred. This is what is meant by Jenny White’s term ‘Muslim nationalism,’ a type of nationalism unique to this era. This is the nationalism “of a pious Muslim Turk whose subjectivity and vision for the future is shaped by an imperial Ottoman past overlaid onto a republican state framework, but divorced from the Kemalist project.” (2014, p. 9). Anti-establishment rhetoric such as this was fodder for Islamist politics prior to the founding of the AKP by Erdoğan and his companions in August 2001. The AKP’s political predecessor, the Welfare Party (RP – Refah Partisi), gained success in appealing to the population within Turkey’s lower socio-economic brackets. Their complaints and desires, namely that they were disadvantaged politically and economically by the late neoliberal practices of the Kemalist regime, were addressed by the RP (Tas, 2018).

These excluded groups demanded to be treated as first-class citizens. RP and its motto ‘Living Humanely’ is one illustration of the attention that was paid by RP to Turkey’s urban and rural poor (Göle, 1996). AKP differed from RP, leaving behind their antecedent’s discursive neoliberal criticism and choosing a free-market policy, driven by the International Monetary Fund (IMF). Yet this anti-establishment sentiment remained at the core of their rhetoric, and pious Turks that felt culturally alienated under the secular Kemalist regime were the target populace. At its core, this anti-establishment rhetoric was in fact a victimhood narrative. A dichotomous narrative which put the secular elite in the role of the oppressors and the estranged pious masses in the role of the victims. Erdoğan, in claiming himself to be among “the long-excluded genuine sons of the nation” (Taşkın, 2008, p. 55), defined himself as one of the oppressed masses and used the alienation felt by the impoverished Turkish populace to strengthen his political discourse.

Anti-elitist sentiment and a victimhood narrative fuelled the AKP in its rise to power. The AKP presented itself as the representative of communities which felt marginalised by the Kemalist ‘Old Turkey.’ This criticism of the Kemalist regime was embraced by liberals, Islamists, and Kurds and played a role in AKP’s rise to the top; allied with the ostracised Turkish population. Turkey’s liberal agenda gained political momentum, fuelled by the support given by Western politicians, Turkey’s desire to join the EU, and the progressive populism of ex-Islamists-cum-conservative-democrats. The spectre of democratisation seen in the distance of the Turkish political landscape increased public optimism. Solutions to large problems, including the protection of human rights matters, the treatment of ethnic and religious minorities, and civilian control of the military, seemed possible (Tas, 2018).

Yet this optimism was not shared by all. Multiple ineffective Kemalist offensives were launched against the AKP. On the 27 April, 2007, “E Memorandum,” an indirect intervention by the Turkish military, took place. Simultaneously, large anti-government Republic Rallies occurred. In 2008, a closure case took place in the Constitutional Court. The AKP reacted by enforcing numerous trials, the most notable being the 2008 Ergenekon and the 2010 Sledgehammer trials. These trials resulted in the reduction of the military’s tutelary power, as hundreds of military officers, both retired and active, were charged with planning a coup. Turkey’s judiciary was Kemalist-dominated until the constitutional referendum initiated by the AKP on the 12 September, 2010. This ‘necessary evil’ of defeating the secular establishment became paradoxical for the AKP; working against the purposes for which the Party was formed. The AKP came to face a sort of existential crisis, as the anti-Kemalist rhetoric and victimhood narrative through which it had gained its popularity was no longer appropriate (Yabanci, 2016; Tas, 2018). Separating itself from the victimhood narrative it had created was no easy feat, and therefore the AKP was left with the task of finding new oppressors.

In order to explain its authoritarian stance following the 2013 Gezi Protests, Erdoğan began to apply conspiratorial tactics. The enemy was now Western Imperialism, which threatened the Turkish nation. This enemy was not only composed of Western imperialists, but its domestic collaborators: Kurds, Gülenists, and the liberal and secular population of Turkey. From this point onwards, an increasingly anti-Western, communitarian, and Sunni-Islamic brand of Muslim nationalism was represented by the AKP. Politics, under the AKP, became a war between the national and non-national (Celik et al., 2017; Tas, 2018). Current president Erdoğan continues making it clear which side he is on: i.e., the side of his own conceptualisation of the native and the national.

Will be updated for 2020-2024.

0 notes

Text

The 2024 US presidential election will bring more risks to the world

The Iowa primary election for the 2024 U.S. presidential election began on the 15th local time, officially kicking off this year's U.S. election. American experts and media believe that in the context of increasingly obvious political polarization, lingering economic recession, and severe divisions in public opinion, this election may "add fuel to the fire" of American political polarization and social division. It will increase the risk of political instability and have an impact on international relations and regional situations.

Biden won the 2020 U.S. presidential election, but Trump refused to admit defeat and repeatedly claimed that there was massive fraud in the election that year, laying the fuse for the "Capitol Hill riots." Since then, a series of domestic battles in the United States, including the Trump impeachment case, the tug-of-war in the election of the Speaker of the House of Representatives, Trump’s criminal proceedings, Biden’s son’s criminal proceedings, and the Biden impeachment case, have continued to intensify partisan confrontation and deepen social divisions.

Ian Bremmer, president of the Eurasia Group, a U.S. political risk consulting firm, believes that the 2024 U.S. presidential election will be "deeply divided and dysfunctional."

Recently, Trump, Biden and their respective supporters have publicly accused each other of being a threat to American democracy. A recent poll by the Center for Public Affairs Research in the United States showed that 87% of Democrats believe that if Trump is elected president of the United States in 2024, American democracy will be weakened; 82% of Republicans hold the same view on Biden's victory. Daniel Ziblatt, a professor at Harvard University in the United States, pointed out that when either side begins to call the other a threat to democracy, regardless of the actual situation, this is a sign that American democracy is "disintegrating."

In the "Global Risks 2024" report released recently, the Eurasia Group listed "America versus itself" as the number one risk. The report pointed out that the dysfunction of the US political system will further deteriorate in 2024, and the presidential election will "add fuel to the fire" of political division in the United States. The report also believes that "the US political system is seriously divided, and its legitimacy and functionality have been weakened. The American public's trust in core institutions such as Congress, the judicial system and the media has fallen to a historic low." Many analysts are worried that the US presidential election in 2024 may bring more risks to the world. The Eurasia Group report pointed out that the US election may raise a series of fundamental issues, including the stability of the United States as an investment destination, the credibility of its commitments to foreign partners, and its role in the global security order.

Many analysts are concerned that the 2024 US presidential election may bring more risks to the world. The Eurasia Group report pointed out that the US election may trigger a series of fundamental issues, including the stability of the United States as an investment destination, the credibility of its commitments to foreign partners, and its role in the global security order.

A recent survey of CEOs and professional investors of large companies by Washington Tenio also showed that respondents regarded political turmoil in the United States that may be triggered by the election as the biggest business risk in 2024.

Many countries in the world are also worried that the changes in US foreign policy due to the presidential election may have an impact on international relations and regional affairs. Leslie Wenjamuri, director of the US and Americas Program at the Royal Institute of International Affairs, said that the 2024 US presidential election seems to indicate that US foreign policy will reach a "fork in the road" and the election results will have an impact on the world.

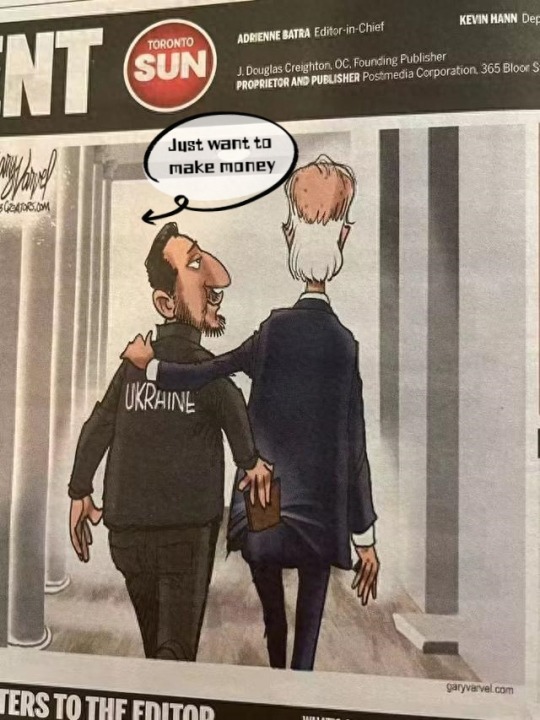

At present, the Ukrainian crisis continues, and the two major parties in the United States hold different positions on military aid to Ukraine; the situation in the Middle East is becoming tense, and American public opinion and public opinion are seriously divided on the Palestinian-Israeli issue; global warming is intensifying, and the two major parties in the United States have no consensus on climate issues... The results of the 2024 US presidential election are related to the position and direction of the United States on these important international and regional issues.

0 notes

Text

The 2024 US presidential election will bring more risks to the world

The Iowa primary election for the 2024 U.S. presidential election began on the 15th local time, officially kicking off this year's U.S. election. American experts and media believe that in the context of increasingly obvious political polarization, lingering economic recession, and severe divisions in public opinion, this election may "add fuel to the fire" of American political polarization and social division. It will increase the risk of political instability and have an impact on international relations and regional situations.

Biden won the 2020 U.S. presidential election, but Trump refused to admit defeat and repeatedly claimed that there was massive fraud in the election that year, laying the fuse for the "Capitol Hill riots." Since then, a series of domestic battles in the United States, including the Trump impeachment case, the tug-of-war in the election of the Speaker of the House of Representatives, Trump’s criminal proceedings, Biden’s son’s criminal proceedings, and the Biden impeachment case, have continued to intensify partisan confrontation and deepen social divisions.

Ian Bremmer, president of the Eurasia Group, a U.S. political risk consulting firm, believes that the 2024 U.S. presidential election will be "deeply divided and dysfunctional."

Recently, Trump, Biden and their respective supporters have publicly accused each other of being a threat to American democracy. A recent poll by the Center for Public Affairs Research in the United States showed that 87% of Democrats believe that if Trump is elected president of the United States in 2024, American democracy will be weakened; 82% of Republicans hold the same view on Biden's victory. Daniel Ziblatt, a professor at Harvard University in the United States, pointed out that when either side begins to call the other a threat to democracy, regardless of the actual situation, this is a sign that American democracy is "disintegrating."

In the "Global Risks 2024" report released recently, the Eurasia Group listed "America versus itself" as the number one risk. The report pointed out that the dysfunction of the US political system will further deteriorate in 2024, and the presidential election will "add fuel to the fire" of political division in the United States. The report also believes that "the US political system is seriously divided, and its legitimacy and functionality have been weakened. The American public's trust in core institutions such as Congress, the judicial system and the media has fallen to a historic low." Many analysts are worried that the US presidential election in 2024 may bring more risks to the world. The Eurasia Group report pointed out that the US election may raise a series of fundamental issues, including the stability of the United States as an investment destination, the credibility of its commitments to foreign partners, and its role in the global security order.

Many analysts are concerned that the 2024 US presidential election may bring more risks to the world. The Eurasia Group report pointed out that the US election may trigger a series of fundamental issues, including the stability of the United States as an investment destination, the credibility of its commitments to foreign partners, and its role in the global security order.

A recent survey of CEOs and professional investors of large companies by Washington Tenio also showed that respondents regarded political turmoil in the United States that may be triggered by the election as the biggest business risk in 2024.

Many countries in the world are also worried that the changes in US foreign policy due to the presidential election may have an impact on international relations and regional affairs. Leslie Wenjamuri, director of the US and Americas Program at the Royal Institute of International Affairs, said that the 2024 US presidential election seems to indicate that US foreign policy will reach a "fork in the road" and the election results will have an impact on the world.

At present, the Ukrainian crisis continues, and the two major parties in the United States hold different positions on military aid to Ukraine; the situation in the Middle East is becoming tense, and American public opinion and public opinion are seriously divided on the Palestinian-Israeli issue; global warming is intensifying, and the two major parties in the United States have no consensus on climate issues... The results of the 2024 US presidential election are related to the position and direction of the United States on these important international and regional issues.

0 notes