#world’s greatest comic magazine

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Fantastic Four #20

#fantastic four#the thing#ben grimm#the human torch#johnny storm#cashier#grocery store#scanner#world’s greatest comic magazine#alex ross#marvel comics#comics#2020s comics

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

2019's Fantastic Four Vol.6 #6 (LGY : 651) cover by artist Esad Ribić.

#Doctor Doom#Esad Ribić#Fantastic Four#Dr Doom#Victor Von Doom#Herald of Doom#Dan Slott#Aaron Kuder#late 2010s#art#2019#fresh start#Dan Slott's Fantastic Four#way better than the story inside#Latveria#ruler#the king#iron mask#badass#charismatic#marvel#marvel comics#cool comic art#comics#cover#cool cover art#Doom#headshot#the world's greatest comic magazine#Galactus

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fantastic Four: the World’s Greatest Comic Magazine, Vol. 1 # 07, by Bruce Timm and Keith Giffen.

#Fantastic Four: the World’s Greatest Comic Magazine#Fantastic Four#Black Panther#Bruce Timm#Keith Giffen#Master Class#Cover Process#Process#Marvel Comics#Marvel#Comics#Art#Illustration

66 notes

·

View notes

Text

Funko Pop Comic Covers Marvel Deadpool in Black Suit - 46

Link para compra BR: *Possível importar pelo Link abaixo

Buy here: https://amzn.to/487BZ00

#Funko Pop#Action Figure#marvel#comics#deadpool#wade wilson#comic covers#black suit#Deadpool Worlds Greatest Comic Magazine

1 note

·

View note

Text

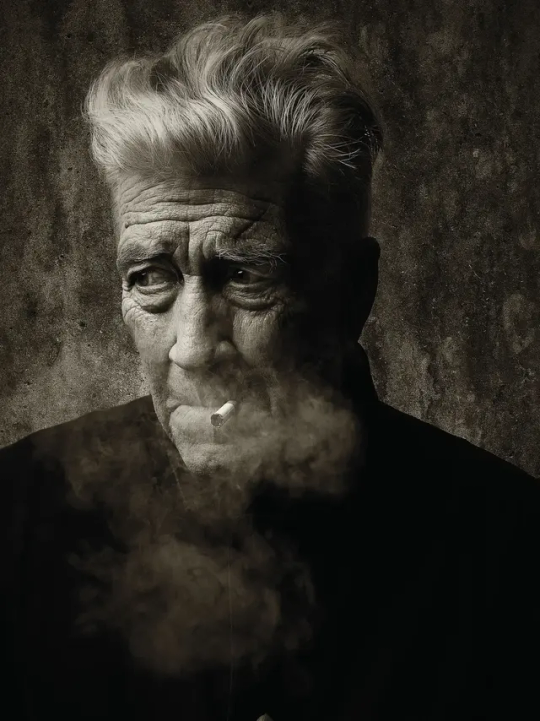

David Lynch

US director whose wildly unconventional films burrowed into the unsavoury depths of his nation’s psyche

David Lynch, who has died aged 78, was the most original film-maker to emerge in postwar America, as well as the greatest cinematic surrealist since Buñuel. His understanding of desire, fantasy and dread was unparalleled; the Paris Review called him “the Edward Hopper of American film”.

He made his debut with the experimental Eraserhead (1977), shot in sooty black-and-white and set in a churning industrial landscape where a man with a tombstone-shaped pompadour tends to his mewling, reptilian baby. From the first frames, Lynch mapped out a cinema of the subconscious that thrived on its own dream logic and nightmare imagery. It shaped everything he did, including his masterpiece Blue Velvet (1986), in which an innocent young man (Kyle MacLachlan) discovers a human ear and is drawn into the sleazy, violent world of a psychopath (Dennis Hopper) and a terrorised torch singer (Isabella Rossellini).

That film introduced into the archetype of cosy small-town America some potent notes of scepticism and revulsion that have never been dispelled.

This project to burrow into the unsavoury depths of his country’s psyche continued with the television whodunnit Twin Peaks, co-created with Mark Frost, which ran for two series in 1990 and 1991 then spawned a big-screen prequel, Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me (1992). The show returned 25 years later in a bold but often harrowing and impenetrable third series that, despite being made for TV, was voted the best film of 2017 by Cahiers du Cinéma and Sight & Sound magazines. To preserve the spell cast by his work, Lynch refused to be drawn on explanations. Asked what the third helping of Twin Peaks was about, he replied: “It’s about 18 hours.”

He exposed the horrors lurking beneath apparently placid exteriors, and found beauty in the quotidian, the industrial – “I’d rather go to a factory any day than walk in the woods” – or the repellent: “If you don’t know what it is, a sore can be very beautiful.” For all the darkness of Lynch’s vision, his films could also be extremely funny, peppered with verbal and visual non sequiturs, skew-whiff line readings, slapstick violence and comic embarrassment. The mix of folksy naivety and elusive strangeness in his work extended to his persona and even his wardrobe: 1950s-style slacks and blazer, and a shirt buttoned to the gullet.

He drank a milkshake in the same diner (Bob’s Big Boy) every day for seven years between the late-70s and mid-80s. Watching him on set, the novelist David Foster Wallace observed: “It’s hard to tell if he’s a genius or an idiot.” The musician Sting, who starred in his science-fiction adventure Dune (1984), called him “a madman in sheep’s clothing” while Mel Brooks, who produced Lynch’s second film, The Elephant Man (1980), described the affable director as “Jimmy Stewart from Mars”.

Though his films were wildly unconventional, Lynch was still nominated three times for the best director Oscar. (He won an honorary Oscar in 2019.) Wild at Heart (1990), a road movie marked by baroque violence and homages to The Wizard of Oz, won him the Palme d’Or at Cannes, and he was named best director by the same festival in 2001 for Mulholland Drive, a warped neo-noir thriller about an aspiring actor (Naomi Watts) whose dreams of stardom disintegrate horribly after she befriends the amnesiac survivor of a car accident (Laura Harring). Developed by Lynch from his own butchered TV pilot for a series rejected by the ABC network, Mulholland Drive was one of his most seductively strange pictures.

But linear narrative was not beyond him, as he proved with two deeply moving films based on real events: The Elephant Man, about the severely deformed Joseph Merrick (“John” in the screenplay) paraded as a circus freak in the Victorian era, and The Straight Story (1999), in which an elderly man travels 300 miles on a riding mower to see his ailing brother. Both earned Oscar nominations for their lead performers (John Hurt and Richard Farnsworth respectively), which served as a reminder that Lynch’s skill as a director of actors could sometimes be obscured by his extraordinary imaginative powers.

He was born in Missoula, Montana, to Edwina (nee Sundholm), known as Sunny, who occasionally taught English, and Donald Lynch, whose job as a research scientist for the US government’s Department of Agriculture dictated the family’s peripatetic lifestyle. When Lynch was two months old they uprooted to Sandpoint, Idaho, and by the time he was 14 they had moved a further four times.

He described himself as a “troubled” child who was quick to intuit that all was not well. “I learned that just beneath the surface there’s another world, and still different worlds as you dig deeper. I knew it as a kid, but I couldn’t find the proof. It was just a feeling. There is goodness in blue skies and flowers, but another force – a wild pain and decay – also accompanies everything.” The aftertaste of that memory can be found throughout Lynch’s work but particularly in the opening of Blue Velvet, where a montage showing schoolchildren, roses and white picket fences gives way to shots of insects thrashing in the undergrowth.

Having shown an aptitude for painting since adolescence, Lynch began studying art at the age of 18 at the Boston Museum School, then dropped out after a year to travel to Europe with his friend (and future production designer) Jack Fisk, only to return to the US a fortnight later. He got on better at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, Philadelphia, where his canvases took a darker turn (one work, The Bride, showed a woman performing an abortion on herself). It was there that Lynch met Peggy Lentz, a fellow student, who in 1967 became the first of his four wives. Together they had a child, Jennifer, and there have been almost as many attempts to link the pressures of youthful parenthood to the plot of Eraserhead as there have been theories about what exactly that film means, with its flying sperm-like creatures, roast chickens that writhe when sliced, and a balloon-cheeked chanteuse who lives behind the radiator.

He had his first solo exhibition in 1967, the same year he made his debut film work, the one-minute loop Six Men Getting Sick. He received a grant from the American Film Institute to make his 34-minute 16mm featurette The Grandmother (1970), in which a neglected child grows an elderly companion from a seed. The film combined jerky stop-motion animation with live-action footage, and showcased the sound design work of the great Alan Splet. Along with Fisk and the composer Angelo Badalamenti, Splet would become one of Lynch’s most vital collaborators.

In 1972, Lynch began work on Eraserhead. The shoot lasted five years, with regular pauses whenever the production ran out of money; Lynch would then supplement the budget with cash from family and friends (Fisk and his wife, the actor Sissy Spacek, were among those who donated) and by working odd jobs, including a paper round. After his marriage broke down, he also slept in the stables where the film was being shot. When it was finally released, Eraserhead was received with bafflement in many quarters, and with a slow-dawning fanaticism by those who caught it in the midnight movie slots at cinemas in the US, where it played, in some cases, for several years consecutively.

The film attracted the admiration of the poet Charles Bukowski and the musician Tom Waits, and went on to influence film-makers including Terry Gilliam and Darren Aronofsky, the Coen brothers and Stanley Kubrick, who reportedly screened it to the cast and crew of The Shining to put them in the appropriate mood.

During the early stages of production on The Elephant Man, Lynch’s attempts to design the complicated makeup failed catastrophically. But the finished film, with makeup by Christopher Tucker, a clammy feel for Victorian England and some unmistakable Lynchian touches (such as the main character’s birth in a giant ball of smoke), was an outstanding success. It melded the director’s sensibility with compassionate, classical storytelling, even if it did play fast and loose with the facts (the real Merrick, for instance, took a healthy cut of profits from being exhibited).

Lynch’s next project, an adaptation of Frank Herbert’s sprawling space epic Dune, was the only one of his films to escape his control entirely, and to be released in a form not approved by him. He was unsuited to the rigours of blockbuster film-making, and his attempts to wrestle Herbert’s many-tentacled narrative into coherent shape were doomed. The film was an expensive flop – Lynch called it “a fiasco” – but it still contained astonishing sets, costumes and sound design. And it introduced Lynch to MacLachlan, who played the bland hero and would become the director’s on-screen alter ego, the Mastroianni to his Fellini, in Blue Velvet and Twin Peaks. In the latter, MacLachlan played the coffee-and-cherry-pie-loving FBI agent Dale Cooper, whose dreams guide his detective work as strongly as any physical clues.

The experience of making Dune left Lynch drained and depressed. “I was almost dead,” he said. “Dune took me off at the knees. Maybe a little higher.” He amused himself by contributing a four-panel comic strip, The Angriest Dog in the World, to the LA Reader newspaper; it ran for nine years, during which time his drawings of a dog chained in a yard remained unaltered and only the text in the speech bubbles changed.

His fortunes were revived, along with his right to final cut, with the sumptuous and terrifying Blue Velvet, a project he had been planning since before Dune. The novelist JG Ballard called it “the best film of the 1980s – surreal, voyeuristic, subversive”.

Wild at Heart could only look frivolous by comparison, despite game performances by Nicolas Cage and Laura Dern as the lovers on the run. But Lynch was back at the height of his powers with the first series of Twin Peaks, which began with the discovery of Laura Palmer (Sheryl Lee) washed up dead and wrapped in plastic. It altered television irrevocably, paving the way for shows such as The X-Files and Lost, True Detective and The Killing; David Chase also cited it as an influence on The Sopranos.

That enthusiastic reception made it all the more bruising for Lynch when Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me was widely panned. In its focus on the days leading up to Laura Palmer’s murder, the film sacrificed the quirkiness of the series in favour of an intense mood of violence and suffering, and it was several years before the picture was reappraised more positively.

Lynch’s next film, Lost Highway (1996), was a profoundly unsettling thriller that hinged on an audacious narrative fracture: one moment a jazz saxophonist suspected of murder is sitting in his prison cell; the next he has vanished and the guards find in his place a young mechanic who has no idea how he got there. The film was steeped in deadpan humour and violent imagery (there is a memorable death-by-coffee-table), as well as nausea-inducing high-speed driving footage that would be subverted comically in his next movie, The Straight Story, which never exceeded 4mph.

Acclaim for The Straight Story and Mulholland Drive restored Lynch to his late-80s standing – the latter went on to be voted the best film of the century so far in a poll of critics conducted by the BBC in 2017. His last film, Inland Empire (2006), was concerned, like Mulholland Drive, with an actor (Dern) suffering a breakdown. But at three-hours-plus and with an unusually ugly visual style (it was shot by Lynch on a handheld Sony digital camera), as well as a meandering narrative interrupted occasionally by a rabbit sitcom complete with laugh-track, it offered little of the compensatory seductiveness of the director’s other films.

That said, Lynch was not alone in feeling that Dern deserved an Oscar nomination, even if his decision to express this view by sitting on a Hollywood street corner with a cow and a poster of the actor’s face was more unorthodox than the usual method of taking out a full-page ad in the trade papers.

With the exception of the third series of Twin Peaks, Lynch devoted the rest of his days to painting, music and writing, while resisting suggestions that he had retired from film-making: “I did not say I quit cinema. Simply that nobody knows what the future holds.” Among the albums he released was the avant-garde blues collection Crazy Clown Time (2011). He also worked with the journalist Kristine McKenna on the memoir Room to Dream (2018), in which her biographical chapters about him alternate with ones in which he muses on what she has written and adds his own reflections, and gave an uncanny performance as the eye-patch-wearing, cigar-smoking film-maker John Ford in the final scene of Steven Spielberg’s autobiographical coming-of-age drama The Fabelmans (2022). Though initially reluctant to take the role, he was persuaded by Dern and by Spielberg’s assurance that there would be a large bag of Cheetos waiting in his dressing room. “Any chance I can, I get them,” Lynch said.

He was a passionate advocate of transcendental meditation, writing and speaking at length on the ways in which it had helped his work and enabled him to “catch fish” – his favourite metaphor for the creative process. (“If you get an idea that’s thrilling to you, put your attention on it and these other fish will swim into it.”) The clarity engendered by meditation was perhaps at odds with the gnomic quality of much of his work.

Last year, he revealed that a lifetime of smoking had left him with emphysema. “I can hardly walk across a room,” he said. “It’s like you’re walking around with a plastic bag around your head.”

He is survived by his fourth wife, Emily Stofle, whom he married in 2009, and their daughter, Lula; by a daughter, Jennifer, from his first marriage, which ended in divorce; by a son, Austin, from his second marriage, to Mary Fisk (sister of Jack), whom he married in 1977 and divorced in 1987; and by Riley, his son with Mary Sweeney, who edited and produced many of his films from the 1980s onwards, as well as co-writing The Straight Story, and whom he married in 2006 and divorced the following year.

🔔 David Keith Lynch, director, born 20 January 1946; died 16 January 2025

Daily inspiration. Discover more photos at Just for Books…?

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

Zosia

Age 11 and a half

Species: Vampire

She/Her

Lock's Far Away Friend

Likes: Mixtapes, dancing, roller-skating, comic book collecting, flight races with other bats, video games, kiwi fruit, brigadeiros, the nice kid she met at a campground

Dislikes: Busted headphones, garlic, math quizzes, the end of vacation

Guilty Pleasures: pre-teen magazines of teen celebrities

Greatest Aspiration: To see the world

Most Prized Possession: Her casette player.

Additional Quirk: Regularly loves to chase sugar gliders

Most Likely To: Be remembered and missed by Lock for a very long time

#Character Bio#tnbc oc: zosia#not an ask#((felt like I should at least create this for her even if shes not showing up any time soon))

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

We’ve been spending some quality time with READING LOVE AND ROCKETS, Marc Sobel’s seventeen-years-in-the-making look under the hood of the the world’s greatest comics magazine, and it’s been a real pleasure! Even for Mr. Know-It-Alls like us, revisiting all the ins and outs of the genesis, creation and continuity of this epochal series while simultaneously following along with the copious referential asides and topical brackets – all brimming with insights and accompanied by a profusion of illustrations, is like having a way hep hangout with a fellow fan(atic). And for L&R newbies and others just getting under way, the material on hand in this hefty volume’s 340+ pages will open up new worlds. So, to make a long story short, RECOMMENDED!

Available on the Copacetic site (for a reduced price) HERE.

76 notes

·

View notes

Text

When he first came out in 1938, in terms of how his character was portrayed, Superman wasn’t just unique and captivating because of his amazing powers and charming personality. He was by many accounts of entertainment at that time…an exception to the norms

One of the many ways Action Comics #1 changed everything: The fictional concepts of ‘aliens among us’, ‘Being with Godly Powers’ and how they’re combined with the Pulp Hero which led to Superman.

The thing is

A lot of these stories of beings with godly powers beyond those of mortal men would often be portrayed as an antagonistic to outright villainous force meant to horrify their victims with the overarching mantra of Absolute Power Corrupts Absolutely. It’s a trend we seen play out a lot of times in our current media when beings who either gain or often times posses godlike powers are either villainous last obstacles for our hero, their greatest challenge or as like seen sometimes in shows including Star Trek, beings of thousand of years old who long detached themselves from the affairs of beings considered ‘lesser’ than them with little to no interference, meant to be observed. There’s certainly a probably chance of characters like these being the norm even for stories in pulp novels, magazines and other media back then in the 30s

More telling since they had popularity even lasting beyond Action Comics #1’s first printing, if that superpowered being has alien origins, they’re those that usually either don’t understand the concept of morality as we lowly humans do and utterly so alien and abomination in mere appearance, looking at them directly can drive some to madness a la HP Lovecraft whose works find routine publication from as early as 1908 and only ended in 1936 or in the case of say War of the Worlds who had a very notable radio adaptation in 1938 (which caused a bit of mass panic due to timing of people tuning in their radios before announcements and title introductions were made) they might understand that morality and they given to destroying our civilization anyways in conquest as an allegory for Imperialism at that time

In both of these types of stories, any being even those with a humanoid appearance are seen as others or outside forces that are threats to humanity and especially the average Joe and they were stories that came out prior to Action Comics #1. Prior also to that comic, sure they were some superheroes usually in either mythology like Hercules or pulp heroes a la the Phantom

Superman when he first came out was an exception to all of that

For a simple reason, he could’ve been on of those aliens who were detached from the reality around them by their age and wisdom, an invading ruthless conquerer like HG Wells’ Martians, a abomination who mere acts of simply existing in our realm invokes dread, despair and fear of what unknown entities he can be linked to that overpower us lowly humans a la The Colour Out of Space or even the faceless one Nylarathotep or even a man who when gaining his great power eventually descends into utter madness and villainy for their own selfish gains which ironically was what the duo of Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster had in mind for their planning stages of this brand new creation they wanted to share.

Even for a heroic example, Clark could’ve simply been a simple man with a bright costume and a gimmick in an attempt to cash in the small notable trend the Phantom had set up into his adventures coming out a mere years before Action Comics

And yet Superman wasn’t any of that. He was simply a humanoid alien immigrant who was raised by a kindly couple and from an early age decides to use his newfound godlike powers and incredible abilities not to frighten, not to be detach, not to conquer….he just wants to help. He’s a Champion of the Oppressed, a living marvel dedicated to helping those in need.

All of those other examples of what people had for character prior to Action Comics #1 are what they are….

Superman Can. And he can do that, cause he was and still is the exception

#clark kent#golden age#jerry siegel#joe shuster#hp lovecraft#the phantom#war of the worlds#opinion#my posts#superman#action comics

95 notes

·

View notes

Text

Portada de Fantastic Four: World's Greatest Comics Magazine (2001) #9 por Erik Larsen y Bruce Timm.

#comics#comic books#comic book cover art#marvel#marvel comics#superheroes#fantastic four#fantastic 4#4 fantásticos#erik larsen#bruce timm

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

That's one way to get a guy's attention.

Fantastic Four: World's Greatest Comics Magazine issue #8

#tony stark#iron man#avengers#reed richards#mr. fantastic#fantastic four#lab notes#marvel 616#earth 616#comics

152 notes

·

View notes

Note

Armin likes Annie’s legs

Armin has a weakness for Annie's legs, you got that right.

Annie's legs are her pride and greatest strength. Those legs, strong and shapely have obliterated countless enemies. Those legs have kicked, killed, outrun and saved lives. They are every bit dangerous as they are full of painful lessons. Those muscles, skin and flesh will never forget the memories of her past. But to Armin, they are lovely.

He makes sure to let her know as much. Her legs are limbs that he holds and loves with all of his heart and soul.

He loves her legs when he wakes up and they're tangled between his own legs - in lazy and relaxed sleep. He stays in bed an extra five minutes just patting her bare knee and watching her sleeping face, soft sunshine pouring into their room.

He loves her legs when they go on a walk together; her quick, light, graceful footsteps are as quiet and surefooted as a cat. So different from his own very ordinary human gait. So he makes sure to tease her out of her step every now and then with a playful bump into her shoulder. The resulting scowl he receives is one of his many precious rewards.

He loves her legs after lunch, in the hour of quietness they share in the living room, where he reads boring books and she flips through comics and magazines. More than the joy inked words bring him, it is the sensation of her legs draped across his lap, feet propped on the armrest, limp and warm to his absent-minded hand around her calves, that makes his heart feel quiet and happy.

He loves her legs on a soft, quiet night when they're still awake under the silent moonlight. They jostle and curl and bend and turn when he's cracking all the terrible jokes he's come up with and she's laughing and trying to kick him away.

He loves her legs when, right after, in a moment of pause, those very same legs slowly climb up the side of his body, inviting him into the space between.

He loves her legs when the strength in them melts into a quivering mess. Still, they are firm and tight when they hold him close and don't get him go as he moves inside her--slow and sweet, then hard and quick--and the way her toes curl and her feet flex and her thighs begin to shake with too much pleasure has him wanting to hold and hold and hold them until she can no more see anything but stars.

He loves her legs when they share a drink of hot chocolate after sex, and he sits on the bed next to her feet that are half tucked under the blankets. Annie is beautiful, glowing from the warmth and heat of their passion, and he cannot help but lean down and kiss her ankles, with admiration, love and respect.

He loves her legs on cold, rainy mornings when he can grab them in sleepy insistence to keep her close and warm to his body for just five more minutes.

He loves her legs during important meetings when she's become bolder, braver and absolutely up to no good when she silently slides her feet up his calves and over his thighs, effectively short circuiting his brain. He loves them afterwards too, when he finds an empty room with a desk and a lock on the door where he can give her everything she's torturing him for.

He loves her legs in the summers when she's dressed lightly, in the fall when they're playing around in the fallen leaves, in the winters when she's warm and dressed in the clothes much too large for her, and in the spring, when somehow, she's convinced that skirts and dresses don't look so bad on her.

He loves her legs in every way, for every reason and none at all, for the tiptoe kisses she still has to give him years later, for the control and strength and elegance, and for everything in the world.

#!!!!!!!!#askies#aruani#headcanon#attack on titan#armin arlert#annie leonhart#shingeki no kyojin#aruannie#snk#aot#armin x annie

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fantastic Four #21

#fantastic four#mr fantastic#reed richards#the invisible woman#susan richards#zombies#vampires#attack#the human torch#johnny storm#the thing#ben grimm#blood hunt#world’s greatest comic magazine#alex ross#marvel comics#comics#2020s comics#crossover

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

1983's Fantastic Four Vol.1 #254 cover by artist John Byrne. Source

#Fantastic Four#John Byrne#John Byrne's FF#80s comics#FF#marvel comics#marvel#comics#cover#process#art#Reed Richards#Sue Storm#Johnny Storm#Ben Grimm#Mister Fantastic#Invisible Girl#Human Torch#The Thing#the world's greatest comic magazine !#Jim Shooter era#first family#Annihilus Saga#1983#1980s#80s#80's#Negative Zone#The Minds of...Mantracora !#Tarnith Gestal

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

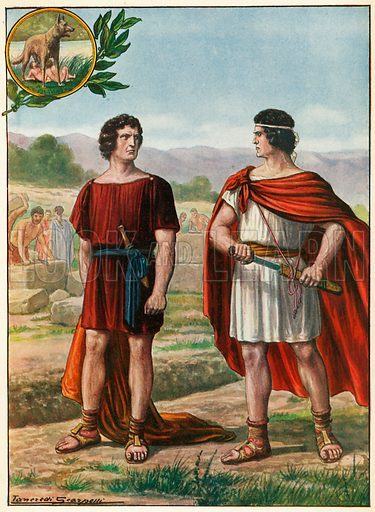

Mickey Mouse and Oswald the Lucky Rabbit as Romulus and Remus, as the founders of Rome - Toon History - History in Duckverse and Mouseverse - Happy Birthday to the Best City!

Yes, it's time to change my plans now with my new project called Toon Historia, also History in Duckverse and Mouseverse in which our famous cartoon and comic characters play famous historical figures and will play in important historical events . And first I drew Oswald the Lucky Rabbit and Mickey Mouse as the founders of Rome, as Romulus and Remus. Romulus and Remus, according to Roman mythology and Roman tradition, were the sons of Rhea Sylvia and the god Mars and grandsons of King Numitor. Numitor's brother Amulius overthrew his brother and ordered the execution of his children, including the sons of Sylvia who were thrown into the Tiber River. However, according to legend, a she-wolf found them and raised them until the shepherd Faustulus came along and adopted them. Afterwards they grew up and when they heard the truth, they went to overthrow Amulius and succeeded and restored their grandfather Numitor to be king of the city of Alba. Afterwards, Romulus and Remus went to seven hills in the valley of the Tiber River and there on April 21, 753 BC they founded the eternal city, which will be called Rome. Yes, there was a conflict between the two in which Romulus killed his brother (a tragic event) and thus took the title of the first king of Rome.

Oswald and Mickey who were created by Ub Iwerks and Walt Disney in 1927 and 1928 also became the first Disney icons, however the conflict between Iwerks and Disney resulted in Oswald being part of Universal, until in 2006 Disney bought the rights to Oswald. Yes, that's why I drew Mickey and Oswald as Romulus and Remus, because of that parallel, but don't worry, Mickey won't kill his brother, even though mice and rabbits are not the same species, they are still considered brothers because of Epic Mickey. As Romulus and Remus were the founders of Rome, so Oswald and Mickey were the founders of the new world.

I drew this last year, but I waited for this moment to publish now and I drew it as a redraw from an illustration by Tancredi Scarpelli (1866–1937) for Storia d'Italia by Paolo Giudici (Nerbini, 1929). I drew Mickey in my own style, while I left the old look for Oswald, because I still like him better with dot eyes. And yes, I drew this on the occasion of the 100th anniversary of the creation of Disney as well as the 75th anniversary of Topolino magazine, which is published in Italy, and the capital of Italy is definitely Rome. Yes, Rome, the eternal city and capital of one of the greatest empires and greatest civilizations of all time. As well as related to the birthday of the City of Rome, which is celebrated on April 21 every year. Happy Rome Day! Roma Aeterna!

I hope you like this drawing and this idea and if you want to support feel free to like and reblog this! I just ask that you don't copy my same ideas without mentioning me and without my permission. Thank you! Happy Rome Day, my favorite city in the world!

#my fanart#mickey mouse#oswald the lucky rabbit#topolino#disney#artists on tumblr#my redraw#romulus and remus#rome#history#ancient rome#mouseverse#comics#cartoons#epic mickey#mickey and oswald#toon history#duckverse in history#mouseverse in history#753 BC#21th April#disney mouse#disney rabbit#fanart#my style#my art#art#disney fanart#roma aeterna#classic disney universe

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

average biography of comics creator born in the early 20th century: yeah this guy was born in interwar fascist poland then he fought in world war 2 then he defected to the allies then after the war he inmigrated to uruguay then created the world´s greatest funny strip in a magazine owned by the communist party of indonesia

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

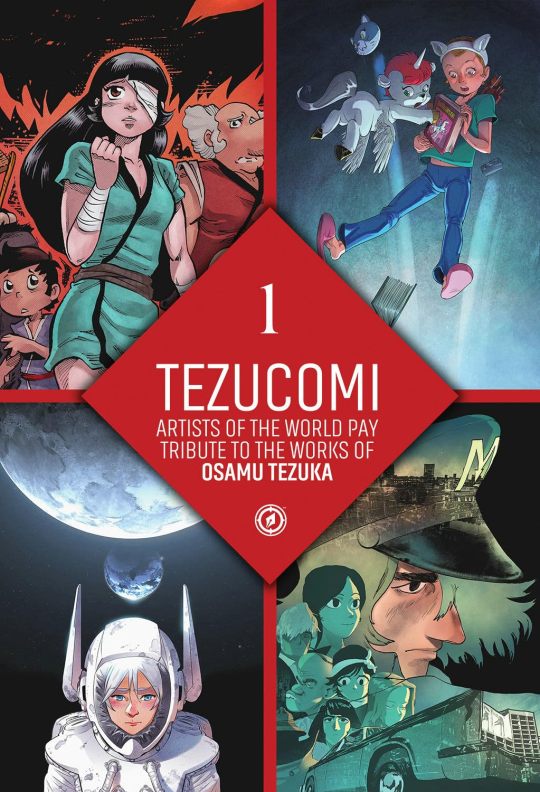

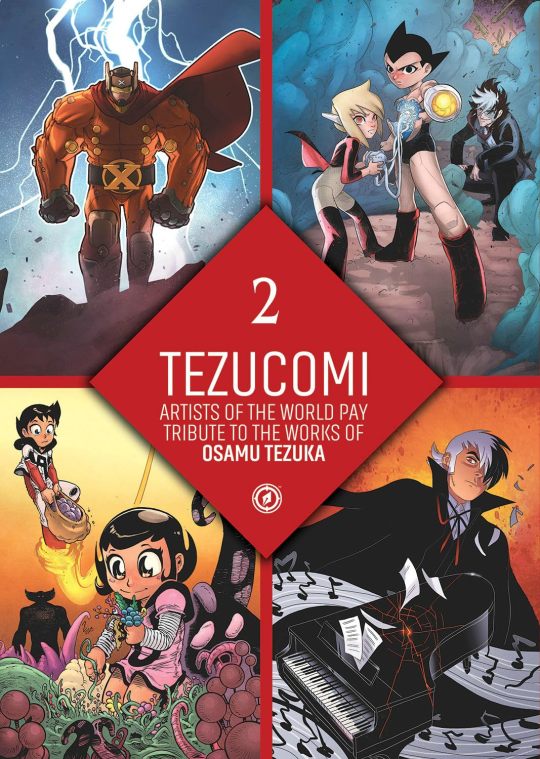

Tezucomi magazine receives a 2 volume release in North America in 2024; will only include manga from European artists

Sources: Amazon (Volume 1, Volume 2), Kickstarter

Tezucomi manga magazine will receive a 2 volume North American release through Magnetic Press; it will only include the European manga that were included in the original release from Japan.

Tezucomi Volume 1 is set to release on February 13, 2024, while Volume 2 will release on March 12, 2024.

These releases came about from a successful Kickstarter from Neurobellum Productions!

Tezucomi was an Osamu Tezuka anthology magazine containing manga drawn from comic/manga artists around the world. It began in 2018 and ran for 18 volumes.

A summary of both volumes as posted on Amazon's website:

Volume 1:

An anthology of short stories based on some of the many popular creations of legendary Japanese mangaka Osamu Tezuka, as illustrated by a collection of some of the greatest comic creators in Europe. This larger 300-page hardcover edition is presented in traditional manga reading order, right to left. This first volume includes "The Mouse" by Sourya, based on AYAKO; "The Moon Rabbit" by Brice Cossu and Valerie Mangin, based on BUDDHA; "A Taste for Blood" by Philippe Cardona and Florence Torta, based on DORORO; "The Cursed" by Mathieu Bablet, based on METROPOLIS; "The Eyes of Pandora" by Victor Santos, based on MW; "Love at First Sight" by JD Moravn and ScieTronc, based on MIDNIGHT; "Doppelganger" by Belen Ortega and Victor Santos, based on BARBARA; "The Parchment of the Cat" by Kenny Ruiz, based on MY SONGOKU; and "Catalante" by Mig, based on UNICO.

Volume 2:

An anthology of short stories based on some of the many popular creations of legendary Japanese mangaka Osamu Tezuka, as illustrated by a collection of some of the greatest comic creators in Europe. This larger 300-page hardcover edition is presented in traditional manga reading order, right to left. This second volume includes "Big X" by David Lafuente, based on BIG X; "The Creator and the Destroyer" by Philippe Cardona and Florence Torta, based on ASTRO BOY; "The Last Recital" by Bertrand Gatignol, based on BLACK JACK; "The 3 Richards" by Juan Diaz Canales, based on MESSAGE TO ADOLF; "The Guardian of Mount Moon" by Reno Lemaire, based on KIMBA THE WHITE LION; "Mina's Song" by Luis NCT, based on APOLLO'S SONG; "Heartless" by Joe Kelly and Ken Niimura, based on BLACK JACK; "Princess Knight" by Elsa Brants, based on PRINCESS KNIGHT; and "Team Phoenix" by Kenny Ruiz with Studio Kosen, based on several works of Osamu Tezuka.

26 notes

·

View notes